Zoning laws that forbid the construction of multifamily housing in the places where people want to live make housing less affordable and increase economic and racial segregation in residential communities. This residential segregation, in turn, drives racial and economic school segregation in a country where 73 percent of students attend neighborhood public schools.1 Decades of research find that school segregation has very detrimental effects on children’s educational opportunity.2 For these reasons and more, therefore, researchers are almost unanimous in thinking that exclusionary and overly strict zoning and land use rules are bad for society.3 Yet, there is often a parallel belief among politicians that there is little that can be done to change those laws, given powerful Not in My Back Yard (NIMBY) voices.

The Century Foundation (TCF) has published a series of reports on the harms of exclusionary zoning in New York State, highlighting in particular the ways in which these policies can impede educational opportunity in places such as Queens, Long Island, Westchester County, and the Buffalo region.4 TCF is also publishing a series of reports about promising efforts of zoning reform in communities in different parts of the country that have overcome the odds and enacted reform, including California, Oregon, and Charlotte, North Carolina. And TCF will be publishing messaging research about ways to reach constituents in New York State on questions of land use reform.

This report focuses on a hopeful story about housing reform from the City of Minneapolis, Minnesota. Back in 2017, Minneapolis employed widespread exclusionary zoning. On 70 percent of the city’s residential land, it was illegal to build anything but a detached single-family home.5 But then, in 2018, observers were stunned when the Minneapolis City Council voted to do something long considered impossible in American politics: it became the first major city in America to end single-family exclusive zoning citywide.6

How did Minneapolis accomplish this feat? What sort of political coalitions were forged to bring about change? And could the lessons learned from Minneapolis help inform efforts to change zoning policies in New York State, New York City, and countless municipalities throughout the state?

The report proceeds in three parts. The first part analyzes how reform was passed. There were many ingredients to success, including strong arguments about housing affordability, racial justice, and the environment. But advocates in Minneapolis suggest the “secret sauce” was the engagement of the voices of those not often a part of land use discussions: those who are harmed and excluded by restrictive zoning.7 The second part examines the preliminary impact of the zoning reform efforts in Minneapolis on building and housing prices. The third part considers implications for zoning and land use reform in New York State, New York City, and other New York municipalities.

The Minneapolis Miracle

Minneapolis, a city of 425,000 residents, was in many ways an unlikely place to pass groundbreaking zoning reform. In 2017, it had a high level of exclusionary zoning. The city banned duplexes, triplexes, and larger apartment buildings from nearly three quarters of its residential land. This high level of exclusion is found in many American cities, though it is not inevitable. In Washington, D.C., for example, 36 percent of residential land is set aside exclusively for single-family homes.8

Moreover, reform advocates in Minneapolis had to contend with the reality that no major city had ever ended single-family exclusive zoning. Indeed, dating back to the 1960s, people who tried to make changes almost invariably failed.9 Such policies have been ubiquitous—“practically gospel in America” says the New York Times—and have long been viewed as impossible to reform.10 As one journalist noted, increasing the supply of housing by relaxing restrictions runs into a classic political problem: “a lot of the beneficiaries are really diffuse,” because those who would gain the most from building higher-density housing in a given neighborhood currently live far and wide. Meanwhile, “the people who view themselves as being harmed are really concentrated.”11

William Fischel, a Dartmouth economist, coined the idea of the “homevoter hypothesis,” which posits that, because homeowners have most of their wealth invested in their homes, they fiercely resist any development that would bring change. Increased supply, as cartels like OPEC know, threatens rising prices.12 And homeowners often fear that development might bring changes to the neighborhood that could negatively affect property values in their neighborhoods, the national research on the issue notwithstanding. Accordingly, when proposals surface to liberalize exclusionary single-family zoning, wealthy homeowners often show up in force, and older, male, white homeowners tend to dominate meetings, according to an important study by Boston University researchers.13 In Lawrence, Massachusetts, where the population is 75 percent Hispanic, for example, over a three-year period, only one resident with an Hispanic surname ever spoke at planning and zoning meetings.14 Those who show up, the researchers found, are unrepresentative in two ways: “Relative to their broader communities, they are socioeconomically advantaged and overwhelmingly opposed to the construction of new housing.”15 The researchers found that just 15 percent spoke at public meetings in Massachusetts in support of new housing compared with 58 percent of Massachusetts voters who took a pro-housing position on a 2010 referendum.16

Laying the Groundwork

Changes in zoning laws in Minneapolis began with a small step. In 2014, council member Lisa Bender backed a successful plan to allow residents in single-family-zoned communities to add small in-law flats or accessory dwelling units (ADUs).17 At the time, one council member raised the specter of ADUs becoming houses of prostitution.18 But when some 140 ADUs were added and fears were not borne out, Bender was ready for more reform.19

Building on that success, in February 2017, a couple of local activists, John Edwards and Ryan Johnson, started an art campaign and an associated Twitter account to raise awareness of the ways in which exclusionary zoning hurt people. Edwards and Johnson called their Twitter account “Neighbors for More Neighbors.”20 The name was a brilliant reminder to people of the shared humanity of those who wanted to be included—they were people, too, who simply wanted to be neighbors.

Momentum for reform built when Jacob Frey, a young candidate for mayor of Minneapolis and himself a renter, made affordable housing “one of the centerpieces of his campaign.”21 In November of 2017, Frey—just thirty-six years old—was elected mayor. Five new members were elected to the city council. The council as a whole now had twelve Democrats and one member of the Green Party.22

In January 2018, the council elevated then-thirty-nine-year-old Lisa Bender—leader of the earlier ADU fight—to be council president. The generational shift was important, said local housing activist Janne Flisrand. The split in Minneapolis over housing was not so much Republican versus Democrat, but older Democrats versus younger ones. The younger elected officials, she noted, “get how housing, racial justice, school success, school segregation, and climate and all these other issues fit together” in a way that some older Democrats did not.23 The stage was set for more.

An Audacious Proposal

In March of 2018, word leaked to the media that the city council was considering allowing duplexes, triplexes, and fourplexes in areas previously zoned exclusively for single-family homes.24 Critics were especially contemptuous of the provision to allow fourplexes, which opponents labeled “freyplexes” after the mayor.25 Council member Andrew Johnson in Ward 12 said the zoning reform proposal would be received “like a lead balloon” by his constituents.26

“Quite a few council members reacted negatively,” Flisrand recalls, but the flipside was that advocates were also energized.27 She teamed up with Edwards and Johnson to create a new grassroots umbrella organization, taking the name of the Neighbors for More Neighbors Twitter account, to support Frey and Bender to do something no major city had ever accomplished: legalize duplexes and triplexes throughout an entire city in one fell swoop.28 Usually reforms to relax zoning laws are fought community by community. But Minneapolis wanted to legalize “missing middle” homes throughout the city.

People were beginning to wake up to the idea, Flisrand says, that “there aren’t enough homes for all the people who want to live in a growing city and that that is harmful in a whole host of different ways.”29 Flisrand says the draft proposal “was clearly pushing us somewhere we hadn’t been yet.” For advocates of change, “it injected a lot of energy. It gave people something to show up for and fight for.”30 While in the past, council and zoning meetings had been dominated by folks saying, “I love my neighborhood and I don’t want it to change,” suddenly new voices were calling for housing that was more abundant and affordable. “That made it feel possible,” she says.31

Janne Flisrand and other Minneapolis activists knew there was a long history of failed attempts to reform zoning laws nationally, but they set out to win, and to do things differently from how activists had in other places. Critically, Neighbors for More Neighbors adopted a strategy that included racial equity as a key theme and formed alliances with community groups to ensure that people not normally heard from—those hurt by exclusionary zoning—were a part of the conversation rather than just wealthier white NIMBY homeowners.

Supporters of reform also knew that in order to be successful, they needed to push a suite of comprehensive changes to supplement the signature issue of eliminating single-family exclusive zoning. Accordingly, the proposal also created the possibility of more housing density near transit stops by allowing the construction of new three- to six-story buildings. It proposed eliminating off-street minimum parking requirements, which can make development too costly. It provided for inclusionary zoning—requiring that new apartment developments set aside 10 percent of units for moderate-income households. And it proposed increasing funding for affordable housing from $15 million to $40 million to combat homelessness and provide immediate relief to low-income renters.32

Rallying Around a Trio of Goals: Affordability, Racial Justice, and a Clean Environment

Neighbors for More Neighbors and their allies capitalized on the fact that Minneapolis, by law, was required every ten years to go through a major planning process. The community is forced to step back and think big about the region’s needs. In the larger framework, known as “Minneapolis 2040,” the city articulated several goals, but three in particular stood out: making the city’s housing more affordable by building more of it; making the city fairer by reducing racial and economic segregation of neighborhoods and schools; and combating climate change by reducing commutes and making housing more environmentally friendly.

First, proponents of the 2040 plan argued, single-family exclusive zoning was driving a major affordability problem in Minneapolis. Studies found that housing supply wasn’t keeping up with growth. The Metropolitan Council suggested that the city had built only 64,000 new homes since 2010 while adding 83,000 households.33 With too many residents chasing too few housing options, the city had an apartment vacancy rate as low as 2.2 percent.34 (Economists suggest a 5 percent vacancy rate is one that will produce a healthy environment in which rents don’t exceed inflation.)35 “When you have demand that is sky-high, and you don’t have the supply to keep up with it, prices rise. Rents rise,” noted Mayor Frey.36

More than half of Minneapolis’s residents were renters, and half of those renters were “cost burdened,” meaning they were spending more than one-third of their income on rent.37 Moreover, the problem was projected to persist in the future. The Family Housing Fund estimated that Minneapolis was only on pace to build about three-quarters of the needed housing in coming decades.38 Building more units, supporters said, would put supply and demand back in balance and reduce unhealthy upward pressure on housing prices.

Second, advocates of the 2040 plan argued that exclusionary single-family zoning should end because it fosters economic and racial segregation, which harms the community. “Large swaths of our city are exclusively zoned for single-family homes, so unless you have the ability to build a very large home on a very large lot, you can’t live in the neighborhood,” Mayor Frey told Slate.39 As a result, families of different races and incomes often lived in different parts of the city—a problem common in American metropolitan areas with exclusionary zoning.

In 2018, Minneapolis’s population was 60 percent white, 19 percent Black, 10 percent Hispanic, and 6 percent Asian, but this diverse population tended to live in very different parts of the community.40 Many North Side households struggled economically, and 70 percent of its residents were people of color, whereas the South Side was more affluent and white.41

In the campaign for change, Flisrand and others put racial and economic justice front and center. Of fourteen goals outlined by supporters of the 2040 plan, eliminating racial, ethnic, and economic disparities was goal number one.42 Proponents of 2040 pointed directly to the role of single-family zoning in fostering segregation.43 Reformers explicitly pointed out the connection between local zoning and redlining. “Today’s zoning is built on those old redlining maps,” said the city’s long-range planning director Heather Worthington.44 Minneapolis City Council president Lisa Bender argued that Minneapolis had “codified racial exclusion through zoning.”45 Proponents of change highlighted the historical record. “That history,” said Councilman Cam Gordon, “helped people realize that the way the city is set up right now is based on the government-endorsed and sanctioned racist system.”46 By owning up to its past, says Slate’s Henry Grabar, Minneapolis was “one of the rare U.S. metropolises to publicly confront the racist roots of single-family zoning.”47

Advocates of zoning reform like Kyrra Rankine argued: “Zoning is the new redlining.”48 And supporters of change drew a direct line between the troublesome history of single-family zoning and contemporary racial disparities in Minneapolis. The 2040 plan noted that the gap in homeownership rates between white people (59 percent) and African Americans (21 percent) was enormous.49 Indeed, it was the widest in any of the one hundred cities with sizable African American populations.50 It is important to acknowledge that the racial justice appeal will not work everywhere; in fact, some research suggests an emphasis on racial equity can reduce public appeal compared with broader economic arguments.51 But in Minneapolis, advocates say the appeal to racial equality was a plus.

Proponents of reform also connected zoning, race, and schools. The South Side of Minneapolis, which is primarily zoned for single-family homes, contained fourteen of the fifteen public schools that are rated as high performing.52 The southwest quadrant of Minneapolis, which is particularly white and affluent, “is like the suburb in the city,” says Rankine.53 In theory, public school choice could equalize opportunities for low-income students living in high-poverty neighborhoods. But in Minneapolis, choice tended to exacerbate, rather than alleviate, segregation.54 Although low-income Minneapolis students could theoretically request a transfer to a high-performing school outside their attendance area, affluent schools tended to be overcrowded already.55 Even when low-income families knew of the opportunities, those requests could be rejected on the basis of space constraints (which was a typical outcome). Moreover, families were required to provide their own transportation—a major hardship for those who are low-income.56 Proponents of reform stressed that access to high-performing schools matters, because powerful evidence suggests that low-income students perform much better, on average, when given the opportunity to attend such schools.57

The third argument advanced by Neighbors for More Neighbors and other proponents of 2040’s plan to eliminate single-family exclusive zoning and build more housing near transit stops was that it would be good for the environment. Dense housing usually means more walkability and access to public transportation. And density also reduces the carbon footprint of housing because housing units that are closer together have lower heating and cooling costs.58 This argument had special resonance with young people. Single-family zoning, one observer noted in writing about Minneapolis, is “a policy that has done as much as any to entrench . . . sprawl.”59

Responding to the Backlash

As expected, Neighbors for More Neighbors and other proponents of reform faced a strong backlash from wealthy white homeowners who didn’t want change. Critics called the elimination of single-family zoning a gift to developers, who would change the “character” of neighborhoods by overbuilding. Red signs emblazoned with the slogan “Don’t Bulldoze Our Neighborhoods” proliferated, particularly in wealthy Southwest Minneapolis.60 Town meetings became vitriolic.61 Critics charged that developers would just tear down starter homes and build high-end duplexes and triplexes that would do nothing to actually help those seeking affordable housing—an argument that overlooked the basic rule of economics that increased supply of any kind reduces prices overall in a community.62

The Audubon Chapter of Minneapolis, ignoring the evidence cited by other environmentalists about how single-family zoning contributes to climate change, brought a lawsuit to stop the policy from moving forward. The suit argued that more housing development, and more people, in Minneapolis, would mean more pollution (something that is true but that also evades the obvious point that a growing population will require new housing somewhere).63 According to the Minneapolis Tribune, “Defenders of single-family neighborhoods dominated the thousands of online comments submitted to the city.”64

In many jurisdictions, this array of opposition might have ended any possible reform. But in Minneapolis, Neighbors for More Neighbors and other groups fought back, point by point. Reformers vehemently denied the idea that they were in the pocket of developers. Some developers, of course, have a strong interest in loosening rules on development and increasing density, but Flisrand said the story is more complex and developers were actually split on the 2040 proposal. Whereas some developers would benefit, other developers would lose their competitive edge that derives from their political access and ability to navigate the existing complex web of regulations.65

Moreover, the specter of an army of new bulldozers taking over neighborhoods with single-family homes was ludicrous, supporters of the 2040 plan said, because people were of course free to keep their homes as is. In addition, neighbors were already tearing down starter homes to build McMansions. What was so wrong with a developer instead building three small units?66 In fact, supporters of the 2040 plan pointed out that a ringleader of the opposition, as it turned out, lived in a 4,500-square-foot house that had been erected after a smaller home was bulldozed.67

The “character” of neighborhoods might change with the addition of some duplexes and triplexes, supporters of the 2040 plan said, but wouldn’t it be a step forward if a community’s character came to include people from different walks of life? Likewise, it might be true that some builders would develop high-end units under the new rules, but even that would reduce overall housing costs in other units, supporters noted, by easing demand for existing homes.68 Furthermore, the inclusionary zoning requirements for new apartment buildings erected under the 2040 plan meant that even high-end developments would have some units that were affordable.

Finally, to blunt criticisms about “freyplexes,” supporters of the 2040 plan modestly scaled it back to allow duplexes and triplexes, but not fourplexes, in areas previously zoned for single-family homes.69 General requirements about height and yard space remained unchanged in those zones, making duplexes and triplexes less daunting for neighbors—a concession that some reform advocates would later come to regret.70

A New Coalition that Included Voices of the Excluded

Flisrand and other activists knew that good arguments for zoning reform had been around forever. To get the proposal across the finish line, they also needed to build a new coalition that included new voices not normally heard in fights over zoning. Many of the core activists in Neighbors for More Neighbors were, like their YIMBY (Yes in My Backyard) movement counterparts across the country, white, highly educated, and upper-middle class.71 Organizers recognized that, as such, they should only be part of a much larger, more socioeconomically and racially diverse coalition in favor of reform that included civil rights groups and labor (as well as environmentalists and seniors).72 Minneapolis wanted to learn from the lessons of some other states, where YIMBY’s and community groups clashed over zoning reform.73

It was natural to ally with civil rights groups in Minneapolis given that civil rights groups nationally had been in the fight against exclusionary zoning long before YIMBY even existed. The NAACP had been the key plaintiff in the 1975 Southern Burlington County NAACP v. Mount Laurel case in New Jersey, seeking to require exclusive communities to build their “fair share” of affordable housing.74 And the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund had been a leader in “disparate impact” litigation, under which exclusionary zoning can be struck down when it has the effect of discriminating by race, even if intent is not shown.75

Minneapolis housing reform advocates knew that in some states, concerns about gentrification and displacement had driven community groups into an unholy alliance with wealthy towns, so Minneapolis reformers wanted to address displacement concerns early on. That is why they insisted on writing inclusionary zoning requirements into the plan to compel developers to set aside some new units for low-income and working-class people. And the significant commitment to boost affordable housing funding made clear that YIMBY groups weren’t advocating a purely market-based approach to reform.

Supporters of the 2040 plan also put a major emphasis on gathering authentic input from community groups in the engagement process, an important step too often ignored. The issue-based organization African Career, Education, and Resource, for example, supported the 2040 plan with extensive community engagement, at church meetings and community meetings, based on the philosophy, says the group’s program director Denise Butler, that “community members are the stakeholders and they are the true experts of their environment.”76 Activists wanted to reach out to constituencies in Minneapolis who could tell the story of how they were personally hurt by exclusionary zoning.

Activists knew that wealthy white homeowners were going to make their voices heard.77 It was critical that lower-income communities, immigrant communities, and communities of color have a seat at the table too. And so, says Flisrand, “The city made a point of creating an engagement pathway” for marginalized communities.78 Indeed, if there was a secret ingredient in Minneapolis’s success, it was community engagement, Flisrand says.79 The city engaged in a multiyear effort to gain input.80 The city’s Long Range Planning Team within the Community Planning and Economic Development Department recognized explicitly that, “historically, people of color and indigenous communities (POCI), renters, and people from low-income backgrounds have been underrepresented in the civic process.”81 Going back to 2016, planners attended festivals and street fairs and went to churches to gather input. The city also encouraged residents to hold “Meetings in a Box,” whereby individuals were provided forms and surveys to seek input from community members at a time and place that were convenient.82 They didn’t speak in jargon-laden terms about “increasing housing density,” but instead asked big questions such as, “Are you satisfied with the housing options available to you right now?” and “What does your ideal Minneapolis look like in 2040?”83

Running parallel to this process, Neighbors for More Neighbors helped community members attend the council meetings, heavily covered by the media, and encouraged people to wear purple so that supporters could find one another and feel comfortable.84 The group also created purple lawn signs that said end the shortage; build homes now and neighbors for more neighbors that sent a positive signal that we “want a city that is growing and welcoming.” In the end, says Flisrand, “Instead of hearing the same old powerful perspectives, we got to hear diverse perspectives.”85

Neighbors for More Neighbors also worked closely with organized labor and tenant groups that were deeply affected by the ways in which single-family exclusive zoning drives up prices of housing for everyone in a community. Tenant groups, which in some cities have organized rent strikes and historically have been important instigators of housing reform, had good reason to support change.86 Policy 41 in the package of Minneapolis 2040 reforms called for taking several steps to protect tenant rights. Among the provisions was one to “provide funding to community-based organizations that proactively help tenants understand and enforce their rights, and assist financially with emergency housing relocation.”87

Labor unions—particularly those with low-income and minority membership—were also an important part of the push for the 2040 plan. The Service Employees International Union (SEIU) Healthcare Minnesota, which represents a large number of mostly low-income healthcare workers, provided critical political muscle for the coalition.88 Rick Varco, political director of SEIU Healthcare Minnesota, explained that, though his union mostly focuses on statewide issues, his members convinced him that local housing issues were of critical concern. Members told Varco they couldn’t afford to live in Minneapolis, near their jobs, and so many would have to take a “two and one half hour bus ride, with two transfers, to get to work.” For many of SEIU’s members, “housing is just an enormous cost for them,” so the union realized “it was important for us to do and say something about it,” he said.89 In October 2018, Varco testified in favor of the 2040 plan before the City Planning Commission, noting the change in zoning would reduce housing costs without costing the city a penny. The current system of exclusionary zoning, he said, “simply elevates a few winners while depriving the large mass of workers the housing they need.”90 In a resolution, SEIU also noted that 2040 would help the economy and “promote union construction jobs.”91

Most environmental groups (Audubon notwithstanding) also provided strong support for the 2040 plan. The Sierra Club and MN 350, a group fighting climate change, were both important in the 2040 plan effort.92 Environmentalists generally favor density and smart growth and have for years decried urban sprawl, which causes longer driving commutes, as a “threat to our environment.”93

Many young people also supported the 2040 plan as a way of making Minneapolis neighborhoods more affordable, diverse, and walkable.94 Millennials are less economically secure than their parents or grandparents were when they were the same ages, and they feel the housing affordability pinch acutely.95 In addition, two-thirds of young people report being lonely (compared with one-third of all Americans).96 So many are seeking housing that allows them to meet interesting people in walkable communities.97 Part of the motivation is practical: because millennials change jobs frequently, they are looking to reside “in heavily networked urban spaces rather than isolated, sprawling suburban locations,” research suggests.98 Finally, progressive millennials are often more racially and environmentally conscious than their elders.99 In many cities, young parents have fought for school integration and are natural allies in fighting for housing integration as a vehicle for integrating neighborhood schools.100

Paradoxically, some older Minneapolis residents also supported reform, often for very different reasons. Of course some older, wealthier residents resisted Minneapolis 2040, but others supported it, as did the American Association of Retired Persons (AARP), both locally and nationally. The group has pushed for more flexibility to build backyard cottages or to subdivide a home into multiple units as a way for elderly residents to “age in place” while bringing in extra income from tenants.101 Other elderly individuals have backed efforts to legalize accessory dwelling units as a way for grandparents to live close to children and grandchildren (spawning the so-called PIMBY movement, “parents in my backyard”).102 Multifamily options can also be attractive to retirees who want to move out of a big lonely house but who are not yet ready to move into assisted living.

Remarkably, the new coalition prevailed against once-invincible NIMBY forces. On December 7, 2018, the Minneapolis City Council adopted what the New York Times called the “simple and brilliant” idea of ending single-family exclusive zoning citywide.103 By a 12–1 vote, the city council legalized duplexes and triplexes on what had been single-family lots, which “effectively triples the housing capacity” in many neighborhoods.104 (The one holdout was a council member from the wealthy southwest section of Minneapolis.)105 The accomplishment was unprecedented. “No municipality has taken a more dramatic response to the housing gap than Minneapolis,” one observer noted.106

Notably, supporters of the 2040 plan say its bold, sweeping scope may have made it easier to pass than more incremental reform. Traditionally, reformers have sought to “upzone” neighborhoods piece by piece, in part based on the theory that upzoning an entire city would consolidate opposition from disparate neighborhoods. But Minneapolis’s director of long-range planning Heather Worthington says going big—citywide—turned out to be a political advantage. “If we were going to pick and choose, the fight I think would have been even bloodier.”107 When only some neighborhoods are chosen for change, locals can feel singled out.108

The Minneapolis Miracle raised an important question. Would its success be replicable in other communities? In 2018, there was reason for skepticism, in part because Minneapolis leans heavily left. Of the thirteen members of the city council, the only non-Democrat was a member of the Green Party. But in subsequent years, Minneapolis proved not to be a unicorn, but rather a gate-opener to reform in a number of parts of the country, from Berkeley, California, to Montgomery County, Maryland, Raleigh, North Carolina and Charlotte, North Carolina. Minneapolis also helped pave the way to broader state-level reforms in Connecticut, Arkansas, Maine, Utah, California, Oregon, Washington, and Montana.109

The Impact of Zoning Reform on Housing Production and Prices

How has Minneapolis’s zoning reform worked on the ground since its passage? The City Council provided preliminary approval of reform in December 2018, and under local rules, required a second round of approvals, which was provided in late October 2019.110 What has happened in the intervening four years?

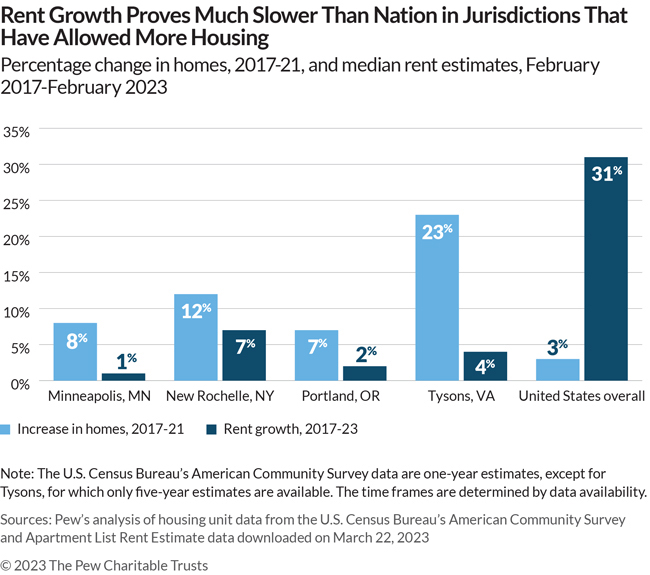

In 2023, the Pew Research Center examined four communities that relaxed zoning restrictions—Minneapolis; New Rochelle, New York; Portland, Oregon; and Tysons, Virginia—and compared the increases in homes and the rent growth in recent years, compared with the national average.

Between 2017 and 2021, Minneapolis saw an 8 percent increase in homes, compared with a 3 percent growth nationally. The relatively larger increase in housing supply in Minneapolis also was associated with a much slower growth in the price of rents. Minneapolis saw rents rise between 2017 and 2021 by just 1 percent, compared with a 31 percent increase in rents nationally.111 (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1

Of course, rents can be affected by a number of factors not associated with zoning. Minneapolis saw considerable civil disturbance after the murder of George Floyd, for example. But it is telling that across the four jurisdictions that had engaged in zoning reform, each saw larger increases in homes (between 7 percent and 23 percent) than the nation as a whole (3 percent), and in all four jurisdictions, rent increases were much lower (between 1 percent and 7 percent) than the national average of 31 percent.112 And the moderation of housing price increases was not the result of a lack of demand for housing. Between 2017 and 2021 the number of households increased in the four communities by between 7 percent and 22 percent, higher than the 6 percent national increase in the number of households.113

The low rental increase in Minneapolis had a very positive effect on moderating the overall increase in the cost of living because shelter costs account for more than one third of the consumer price index. In August 2023, Bloomberg CityLab reported that making housing more affordable was the key reason why Minneapolis had become “the first American city to tame inflation.” Bloomberg found that the Minneapolis region had authorized 14,600 multifamily units in 2022, which put it eleventh out of fifty-five peer metropolitan areas in permits per capita. Some skeptics thought all the new buildings would be expensive and increase rents, says Minneapolis’s mayor Jacob Frey, but in fact “the exact opposite has occurred.” Mark Zandi, chief economist at Moody’s Analytics, noted, “There is no more effective way to rein in inflation than to expand the supply of affordable housing and increase housing affordability.”114

What specific zoning reforms made the biggest difference in Minneapolis to allow for more growth and moderating rent increases? Urban Institute scholar Yonah Freemark found that the number of housing units permitted doubled from 2015 to 2020, mostly because of changes in zoning laws that allowed larger buildings with at least ten units. Elimination of off-street parking requirements and the earlier legalization of accessory dwelling units also contributed. Less important, Freemark concluded, was the legalization of duplexes and triplexes, which contributed a smaller number of units to the total.115

Experts noted that one major limitation—in retrospect, a mistake—in the legalization of duplexes and triplexes in Minneapolis was the decision to require that new multifamily units be no taller or wider than the single-family homes they replaced. This is a condition that many new single-family homes—especially McMansions—would rarely meet. That onerous limitation on duplexes and triplexes hurt the financial viability of multifamily housing in Minneapolis. As Vicki Been of New York University’s Furman Center told Business Insider, “The devil is in the details.”116

In November 2023, a judge brought at least a temporary halt to continued implementation of the 2040 plan. The judge found that planners had not conducted a proper environmental review, even though such reviews had not been required in the past for this type of reform. Some environmental groups, such as the Sierra Club, denounced the lawsuit that brought the halt to 2040’s implementation as NIMBYism in disguise. The judge’s ruling is on appeal.117

Lessons for New York State, New York City, and Other New York Municipalities

The broader lessons of the Minneapolis experience—zoning reform is possible at scale; policies can lead to more housing production; and that housing production can moderate housing prices—are all important ones for municipalities in New York State.

Moreover, the political strategies and tactics employed seem particularly relevant for New York City, given similarities in its broad political outlook to those found in Minneapolis. New York City and Minneapolis are consistently ranked among the most liberal cities in America.118 Of the thirteen members of the Minneapolis city council when zoning reform was adopted, the only non-Democratic member was from the Green Party.119 In the New York City Council, Democrats outnumber Republicans 45 to 6.120

In New York City, a recent Data for Progress poll found, voters take a very progressive view of housing. According to the survey, two-thirds of likely New York City voters said it is “very important” to address the housing crisis, and of these, a majority—60 percent—said they favor a not-for-profit public approach to addressing the housing crisis. The survey also found that many voters were skeptical of developers and market-based approaches to housing.121

Given this finding, Minneapolis’s emphasis on the liberal reasons to be for zoning reform—that it will reduce racial segregation, make housing more affordable, stem homelessness, and improve the environment—seems important to stress. Likewise, the Minneapolis approach of combining market-based zoning reform with new investments in public housing, would appear more persuasive than one focused on zoning reform alone.

And the emphasis of advocates in Minneapolis on the fact that the highest-performing public schools are often reserved for students living in areas that only those who can afford single-family homes can access—a major theme in The Century Foundation’s series of housing reports—seems worth emphasizing in New York City. Although New York City allows for public school choice, particularly at the high school level, many students end up attending school close to home, which means access is dependent at least in part on what type of housing is allowed. In Queens, for example, Bayside/Little Neck and Jamaica/Hollis are located just six miles apart, but Bayside/Little Neck’s higher-performing schools are much less accessible to families who cannot afford a single-family home there than those in Jamaica/Hollis where housing is more affordable.122

Arguments about the ways that zoning laws unfairly exclude children of modest means from attending strong public schools can be effective, according to polling in states as varied as New Hampshire and Virginia. A 2021 poll in New Hampshire found the most effective argument for zoning reform with voters was one that emphasized a combination of affordability and access to education:

New Hampshire’s planning and zoning regulations are unfair to working families struggling to make ends meet. By limiting the new housing that can be built, these restrictions drive up rents and house prices, making housing completely unaffordable for more and more Granite Staters. Everyone knows that some towns in New Hampshire are much more expensive to buy in than others, and they tend to be the places with better schools. So poor families in New Hampshire get stuck in poverty, because they cannot afford to live where they can get a better education for their kids.123

Likewise, a 2023 poll of Virginia voters found that nearly 84 percent agreed that low-income students “should have access to the same public schools as students in high-income households”124—suggesting a possible political opening for reforms that seek to enhance educational opportunities by lowering exclusionary zoning barriers.

In addition to following Minneapolis’s example on connecting housing and schooling, New York City could take steps, as Minneapolis did, to elevate the voices of excluded families who are not often part of housing debates. Powerful NIMBY voices let their views be known, so it is important that New York City officials work hard to visit street fairs and other venues where people whose lives will be deeply affected by housing policy are given a chance to participate in the democratic process.125

It is not only large cities such as New York and Minneapolis that can make changes. For suburban areas in New York, a close-to-home example of success cited by Pew researchers is New Rochelle, in Westchester County. According to Pew, in 2017 and 2018, New Rochelle permitted a modest thirty-seven new homes on average per year. But its decision to rezone the downtown area and to streamline permitting to allow apartment buildings near transit had an enormous impact on the number of permits issued. The average annual permits during 2019 to 2021 shot up to 989. Moreover, the new supply had the desired effect on rents. Between January 2017 and January 2020, rents rose 12 percent, but from January 2020 to February 2023, rents rose just 5 percent. New Rochelle’s overall increase in homes from 2017 to 2021 was 12 percent, quadruple the national average of 3 percent; and overall rent increases of 12 percent was just a fraction of the 31 percent increase in rent nationally.126

An August 2023 Wall Street Journal article on New Rochelle, pointed to the rise in multifamily housing permitted after zoning reforms and declared that the city “is emerging as a potential blueprint for overcoming the various political, financial, and community obstacles that made efforts to build multifamily housing in the suburbs and often insurmountable task.” The city’s master plan to allow quick permitting of units was coupled by smart strategies to bring along residents who might otherwise oppose change. For example, officials “offered virtual-reality goggles near the downtown to help residents visualize the new buildings and offer their feedback.” And they provided sweeteners to nearby residents, such as the chance to attend new free outdoor concerts paid for by the developer.127

Looking Ahead

New York City and other New York State municipalities have a chance to create a better future in which housing prices are more affordable, housing is less economically and racially segregated, and workers are not forced to endure lengthy and onerous commutes in order to get from home to work and back again. Importantly, the reduction in neighborhood segregation would translate into reduced school segregation. That development, in turn, would mean substantially better educational opportunities for children. Government zoning laws helped create a host of problems, and as a growing number of communities—from Minneapolis to New Rochelle—have shown, reforms are not only necessary but also possible.

Notes

- National Center for Education Statistics, “Public School Choice Programs,” https://nces.ed.gov/fastfacts/display.asp?id=6.

- See e.g. Richard D. Kahlenberg, Halley Potter, and Kimberly Quick, “A Bold Agenda for School Integration,” The Century Foundation, April 8, 2019, https://tcf.org/content/report/bold-agenda-school-integration/.

- See e.g. Jenny Schuetz, Fixer-Upper: How to Repair America’s Broken Housing System (Washington, D.C.: Brookings Institution Press, 2022).

- Richard D. Kahlenberg, “How Housing Policies Create Unequal Educational Opportunities: The Case of Queens, New York,” The Century Foundation, April 3, 2023, https://tcf.org/content/report/how-housing-policies-create-unequal-educational-opportunities-the-case-of-queens-new-york/; Richard D. Kahlenberg, “Housing and Educational Inequality: The Case of Long Island,” The Century Foundation, June 1, 2023, https://tcf.org/content/report/housing-and-educational-inequality-the-case-of-long-island/; Richard D. Kahlenberg, “How Zoning Drives Educational Inequality: The Case of Westchester County,” The Century Foundation, July 17, 2023, https://tcf.org/content/report/how-zoning-drives-educational-inequality-the-case-of-westchester-county/; and Richard D. Kahlenberg, “How Zoning Promotes Inequality in Education: The Case of the Buffalo Area,” The Century Foundation, September 21, 2023, https://tcf.org/content/report/how-zoning-promotes-inequality-in-education-the-case-of-the-buffalo-area/.

- Emily Badger and Quoctrung Bui, “Cities Start to Question an American Ideal: A House with a Yard on Every Lot,” New York Times, June 18, 2019, https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2019/06/18/upshot/cities-across-america-question-single-family-zoning.html.

- Portions of this case study draw from Richard D. Kahlenberg. Excluded: How Snob Zoning, NIMBYism and Class Bias Build the Walls We Don’t See (New York: Public Affairs Books, 2023).

- Janne Flisrand, “Minneapolis’ Secret 2040 Sauce Was Engagement,” Streets MN, December 10, 2018, https://streets.mn/2018/12/10/minneapolis-secret-2040-sauce-was-engagement/.

- Badger and Bui, “Cities Start to Question an American Ideal.”

- Kahlenberg, Excluded, 160–63.

- Badger and Bui, “Cities Start to Question an American Ideal.”

- See Jerusalem Demsas in Ezra Klein, “How Blue Cities Became So Outrageously Unaffordable: How the Party of Big Government Became the Party of Paralysis,” Ezra Klein Show (podcast), New York Times, July 23, 2021, https://www.nytimes.com/2021/07/23/opinion/ezra-klein-podcast-jerusalem-demsas.html?showTranscript=1.

- William A. Fischel, The Homevoter Hypothesis: How Home Values Influence Local Government Taxation, School Finance, and Land-Use Policies (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2005).

- Katherine Levine Einstein, David M. Glick, and Maxwell Palmer, Neighborhood Defenders: Participatory Politics and America’s Housing Crisis (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2020), 103–05. See also Sarah Holder and Kriston Capps, “The Push for Denser Zoning Is Here to Stay,” CityLab, Bloomberg, May 21, 2019, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2019-05-21/to-tackle-housing-inequality-try-upzoning.

- Einstein, Glick, and Palmer, Neighborhood Defenders, 103–05.

- Einstein, Glick, and Palmer, Neighborhood Defenders, 16.

- Einstein, Glick, and Palmer, Neighborhood Defenders, 107–08.

- Jessica Lee, “How Much Will Minneapolis’ 2040 Plan Actually Help with Housing Affordability in the City?” Minnpost, May 31, 2019, https://www.minnpost.com/metro/2019/05/how-much-will-minneapolis-2040-plan-actually-help-with-housing-affordability-in-the-city/; John Edwards, “The Whole Story on Minneapolis 2040,” Wedge-Times Picayune, December 13, 2018, https://wedgelive.com/the-whole-story-on-minneapolis-2040/.

- John Edwards, “The Whole Story on Minneapolis 2040”; and John Edwards, “Minneapolis City Council President Barb Johnson Predicts Doom over ADUs in 2014,” YouTube video, 1:35, Wedge Live, March 10, 2017, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=I-CrltFkiow.

- Jessica Lee, “How Much Will Minneapolis’ 2040 Plan Actually Help?” (140 ADUs); and Bender’s thoughts, paraphrased in Henry Grabar, “Minneapolis Confronts Its History of Housing Segregation,” Slate, December 7, 2018, https://slate.com/business/2018/12/minneapolis-single-family-zoning-housing-racism.html.

- Henry Grabar, “‘Talk to Your Friends About Zoning’: A PSA Campaign for the NIMBY in Your Life,” Slate, February 13, 2017, https://slate.com/business/2017/02/talk-to-your-friends-about-zoning-a-psa-campaign-for-your-nimby-neighbors.html; and “Neighbors for More Neighbors” Twitter account, @MoreNeighbors https://twitter.com/MoreNeighbors?ref_src=twsrc%5Egoogle%7Ctwcamp%5Eserp%7Ctwgr%5Eauthor.

- Peter Callaghan, “Inclusionary Zoning: Will Minneapolis See It This Year?” Minnpost, February 19, 2018, https://www.minnpost.com/metro/2019/08/minneapolis-inclusionary-zoning-policy-takes-shape-even-as-developers-cry-foul/; and Grabar, “Minneapolis Confronts Its History of Housing Segregation” (Frey may be the city’s “first tenant mayor”).

- Grabar, “Minneapolis Confronts Its History of Housing Segregation”; Janne Flisrand, telephone interview with author and Tabby Cortes, July 8, 2019 (hereafter interview I); Rick Varco, telephone interview with author and Tabby Cortes, July 9, 2019; and Edwards, “The Whole Story on Minneapolis 2040.”

- Janne Flisrand, interview I.

- Janne Flisrand, interview with author, February 3, 2022 (hereafter, interview II), 9.

- Patrick Sisson, “Can Minneapolis’s Radical Rezoning Be a National Model?” Curbed, November 27, 2018, https://www.curbed.com/2018/11/27/18113208/minneapolis-real-estate-rent-development-2040-zoning

- Edwards, “The Whole Story on Minneapolis 2040.”

- Flisrand interview II, 18.

- Edwards, “The Whole Story on Minneapolis 2040”; Flisrand interview II, 5.

- Flisrand interview II, 10.

- Flisrand interview II, 13.

- Flisrand interview II, 12, 14.

- Jessica Lee, “How Much Will Minneapolis’ 2040 Plan Actually Help?”; Kriston Capps, “2018 Was the Year of the YIMBY,” CityLab, Bloomberg, December 28, 2018, https://www.citylab.com/equity/2018/12/single-family-housing-zoning-nimby-yimby-minneapolis/577750/ (Minneapolis follows Buffalo, Hartford, and San Francisco); Henry Grabar, “Minneapolis Confronts Its History of Housing Segregation”; John Edwards, “The Whole Story on Minneapolis 2040.” Nelima Sitati Munene and Aaron Berc, “Minneapolis Inclusionary Housing Policy Framework Is Needed Throughout the Region,” Minnpost, December 13, 2018, https://www.minnpost.com/community-voices/2018/12/minneapolis-inclusionary-housing-policy-framework-is-needed-throughout-the-region/; Erick Trickey, “How Minneapolis Freed Itself from the Stranglehold of Single-Family Homes,” Politico, July 11, 2019, https://www.politico.com/magazine/story/2019/07/11/housing-crisis-single-family-homes-policy-227265; J. Brian Charles, “Will Up-Zoning Make Housing More Affordable?” Governing, July 2019, https://www.governing.com/topics/urban/gov-zoning-density.html; and Patrick Sisson, “Can Minneapolis’s Radical Rezoning Be a National Model?” Curbed, November 27, 2018, https://www.curbed.com/2018/11/27/18113208/minneapolis-real-estate-rent-development-2040-zoning.

- Sisson, “Can Minneapolis’s Radical Rezoning Be a National Model?”

- Sisson, “Can Minneapolis’s Radical Rezoning Be a National Model?”

- Trickey, “How Minneapolis Freed Itself from the Stranglehold of Single-Family Homes.”

- Christian Britschgi, “Progressive Minneapolis Just Passed One of the Most Deregulatory Housing Reforms in the Country,” Reason, December 10, 2018, https://reason.com/2018/12/10/progressive-minneapolis-just-passed-one.

- Sisson, “Can Minneapolis’s Radical Rezoning Be a National Model?”; and Lee, “How Much Will Minneapolis’ 2040 Plan Actually Help?”

- Lee, “How Much Will Minneapolis’ 2040 Plan Actually Help?”

- Grabar, “Minneapolis Confronts Its History of Housing Segregation.”

- “QuickFacts: Minneapolis City, Minnesota,” US Census Bureau, https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/minneapoliscityminnesota (income data are from 2013–2017).

- John Eligon, “Minneapolis’s Less Visible, and More Troubled, Side,” New York Times, January 10, 2016, https://www.nytimes.com/2016/01/11/us/minneapoliss-less-visible-and-more-troubled-side.html; and Burl Gilyard, “Why North Minneapolis Struggles to Attract Businesses—and Why That May Be Changing,” Minnpost, March 21, 2016, https://www.minnpost.com/twin-cities-business/2016/03/why-north-minneapolis-struggles-attract-businesses-and-why-may-be-chang/.

- “Welcome to Minneapolis 2040: The City’s Comprehensive Plan,” Minneapolis 2040, 8–13, https://minneapolis2040.com/media/1488/pdf_minneapolis2040.pdf.

- Trickey, “How Minneapolis Freed Itself from the Stranglehold of Single-Family Homes.”

- Sisson, “Can Minneapolis’s Radical Rezoning Be a National Model?”

- Lisa Bender, “How U.S. Cities Are Tackling the Affordable Housing Crisis,” 1A with Joshua Johnson, WAMU, August 28, 2019, https://the1a.org/shows/2019-08-28/1a-across-america-yimby-can-density-increase-affordable-housing.

- Grabar, “Minneapolis Confronts Its History of Housing Segregation.”

- Grabar, “Minneapolis Confronts Its History of Housing Segregation.”

- Quoted in Richard D. Kahlenberg, “Minneapolis Saw That NIMBYism Has Victims,” The Atlantic, October 24, 2019, https://www.theatlantic.com/ideas/archive/2019/10/how-minneapolis-defeated-nimbyism/600601/.

- “Welcome to Minneapolis 2040,” 11, https://minneapolis2040.com/media/1488/pdf_minneapolis2040.pdf.

- “Americans Need More Neighbors,” editorial, New York Times, June 15, 2019, 10, https://www.nytimes.com/2019/06/15/opinion/sunday/minneapolis-ends-single-family-zoning.html.

- See e.g. Jerusalem Demsas, “How to Convince a NIMBY to Build More Housing,” Vox, February 24, 2021, https://www.vox.com/22297328/affordable-housing-nimby-housing-prices-rising-poll-data-for-progress.

- See “Welcome to Minneapolis 2040,” 107, https://minneapolis2040.com/media/1488/pdf_minneapolis2040.pdf; Badger and Bui, “Cities Start to Question an American Ideal”; and “Best Schools in Minneapolis Public School District,” SchoolDigger.com, https://www.schooldigger.com/go/MN/district/21240/search.aspx.

- Kyrra Rankine, telephone interview with author and Michelle Burris, October 7, 2019. See also “Integration and School Choice in MPS,” Minneapolis Public Schools, September 2019, https://mpls.k12.mn.us/uploads/integration_and_choice_in_mps.pdf.

- “Integration and School Choice in MPS”; Kyrra Rankine, telephone interview with author and Michelle Burris, October 7, 2019.

- “Integration and School Choice in MPS.”

- See “Questions and Answers,” Minneapolis Public Schools, https://exploremps.org/FAQ.

- See, for example, Heather Schwartz, “Housing Policy Is School Policy,” The Century Foundation, 2010, https://tcf.org/content/commentary/housing-policy-is-school-policy/.

- Edward L. Glaeser, “Green Cities, Brown Suburbs: To Save the Planet, Build More Skyscrapers—Especially in California,” City Journal, Winter 2009, https://www.city-journal.org/html/green-cities-brown-suburbs-13143 .html.

- Grabar, “Minneapolis Confronts Its History of Housing Segregation.”

- “Minneapolis, Tackling Housing Crisis and Inequity, Votes to End Single-Family Zoning,” One World News, December 14, 2018, https://theoneworldnews.com/americas/minneapolis-tackling-housing-crisis-and-inequity-votes-to-end-single-family-zoning/; and Edwards, “The Whole Story on Minneapolis 2040.”

- Janne Flisrand, “Minneapolis’ Secret 2040 Sauce Was Engagement,” Streets.mn, December 10, 2018, https://streets.mn/2018/12/10/minneapolis-secret-2040-sauce-was-engagement/.

- Sisson, “Can Minneapolis’s Radical Rezoning Be a National Model?”

- Miguel Otarola, “Judge Hears Lawsuit over Minneapolis 2040 Plan,” Minneapolis Star Tribune, January 31, 2019, http://www.startribune.com/judge-to-rule-on-lawsuit-over-minneapolis-2040-plan/505156872/.

- Einstein, Glick, and Palmer, Neighborhood Defenders, 166, citing Miguel Otarola, “Minneapolis City Council Approves 2040 Comprehensive Plan on 12-1 Vote,” Minneapolis Star Tribune, December 7, 2018, https://www.startribune.com/minneapolis-city-council-approves-2040-comprehensive-plan-on-12-1-vote/502178121/.

- Flisrand, interview I. See also Brian Hanlon, interview with author, April 20, 2018.

- Grabar, “Minneapolis Confronts Its History of Housing Segregation”; and Edwards, “The Whole Story on Minneapolis 2040.”

- Edwards, “The Whole Story on Minneapolis 2040.”

- “Americans Need More Neighbors,” editorial, New York Times, June 15, 2019, citing Rosenthal, “Are Private Markets and Filtering a Viable Source,” 687–706.

- Sisson, “Can Minneapolis’s Radical Rezoning Be a National Model?”

- Grabar, “Minneapolis Confronts Its History of Housing Segregation”; and Britschgi, “Progressive Minneapolis Just Passed One of the Most Deregulatory Housing Reforms in the Country.”

- Philip Kiefer, “Here Comes the Neighborhood,” Grist, May 21, 2019, https://grist.org/article/seattle-zoning-density-minneapolis-2040/; and Flisrand interview I.

- Flisrand interview I.

- Trickey, “How Minneapolis Freed Itself from the Stranglehold of Single-Family Homes”; and Joe Fitzgerald Rodriguez, “SB 827 Rallies End with YIMBYs Shouting Down Protesters of Color,” San Francisco Examiner, April 5, 2018, https://www.sfexaminer.com/news/sb-827-rallies-end-with-yimbys-shouting-down-protesters-of-color/article_42f1bb0c-c4c5-5401-a395-5aff1b28137c.html.

- Southern Burlington County NAACP v. Mt. Laurel, 67 N.J. 151 (1975).

- “Disparate Impact,” NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, http://www.naacpldf.org/case-issue/disparate-impact.

- Denise Butler, telephone interview with author and Tabby Cortes, July 12, 2019.

- Einstein, Glick, and Palmer, Neighborhood Defenders, 103–105. See also Holder and Capps, “The Push for Denser Zoning Is Here to Stay.”

- Flisrand interview I. See also Casey Berkovitz, “Is a Better Community Meeting Possible?” The Century Foundation, August 20, 2019, https://tcf.org/content/commentary/better-community-meeting-possible/.

- Flisrand, “Minneapolis’ Secret 2040 Sauce Was Engagement.”

- Grabar, “Minneapolis Confronts Its History of Housing Segregation.”

- “Welcome to Minneapolis 2040,” 177, https://minneapolis2040.com/media/1488/pdf_minneapolis2040.pdf.

- Berkovitz, “Is a Better Community Meeting Possible?”

- Janne Flisrand, “Minneapolis’ Secret 2040 Sauce Was Engagement,” Streets MN, December 10, 2018, https://streets.mn/2018/12/10/minneapolis-secret-2040-sauce-was-engagement/; and Richard D. Kahlenberg, “How Minneapolis Ended Single-Family Zoning,” The Century Foundation, October 24, 2019, https://tcf.org/content/report/minneapolis-ended-single-family-zoning/.

- Flisrand interview I.

- Flisrand, “Minneapolis’ Secret 2040 Sauce Was Engagement.”

- Matthew Desmond, Evicted: Poverty and Profit in the American City (New York: Crown Publishers, 2016), 180.

- “Tenant Protections,” Policy 41, Minneapolis 2040 Plan, https://minneapolis2040.com/policies/tenant-protections/.

- Flisrand interview I.

- Rick Varco, interview with author and Tabby Cortes, July 9, 2019.

- Rick Varco, “#Mpls2040: Pro-Worker” (testimony before City Planning Commission), YouTube video, 1:48, WEDGE Live!, October 29, 2018, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZJHyHOkCG9U.

- “Minneapolis 2040 Comprehensive Plan Public Comments,” in SEIU MN State Council Resolution in Support of Increased Housing Density, adopted April 26, 2018, https://lims.minneapolismn.gov/Download/File/1784/Online%20Comments%20on%20Revised%20Draft%20Plan%20Pt%203%20Oct%2029-Nov%201%202018.pdf. See also “Americans Need More Neighbors,” editorial, New York Times, June 15, 2019.

- Edwards, “The Whole Story on Minneapolis 2040”; Flisrand interview I.

- See, for example, Oregon governor Tom McCall’s support for smart growth. Carl Abbott and Deborah Howe, “The Politics of Land-Use Law in Oregon: Senate Bill 100, Twenty Years After,” Oregon Historical Quarterly 94, no. 1 (1993), http://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1029&context=usp_fac.

- “Americans Need More Neighbors,” editorial, New York Times, June 15, 2019.

- Diana Lind, Brave New Home: Our Future in Smarter, Simpler, Happier Housing (New York: Bold Type Books, 2020), 88.

- Judith Shulevitz, “Co-Housing Makes Parents Happier,” New York Times, October 24, 2021, 4.

- Pawan Naidu, “What Do Millennials Want? More Trains and Buses, Fewer Automobiles,” The Observatory, April 17, 2018, https://observatory.journalism.wisc.edu/2018/03/21/what-do-millennials-want-more-trains-and-buses-fewer-automobiles/ (citing 2014 Nielson survey).

- John A. Powell and Stephen Menendian, “Opportunity Communities: Overcoming the Debate over Mobility Versus Place-Based Strategies,” in The Fight for Fair Housing: Causes, Consequences, and Future Implications of the 1968 Federal Fair Housing Act, ed. Gregory Squires (New York: Routledge, 2018), 213 (citing 2016 research).

- Lind, Brave New Home, 119–20, 134–39.

- See, for example, the New York City student group championing integration, known as IntegrateNYC4me, http://www.integratenyc4me.com/about-us/.

- Trickey, “How Minneapolis Freed Itself from the Stranglehold of Single-Family Homes”; Grabar, “Minneapolis Confronts Its History of Housing Segregation”; and Samantha Kanach, “Zoning is Key Ingredient for Community Change and Improvement,” American Association of Retired Persons, https://www.aarp.org/livable-communities/livable-in-action/info-2023/lctap-zoning.html.

- Lind, Brave New Home, 171.

- “Americans Need More Neighbors,” editorial, New York Times, June 15, 2019.

- “Minneapolis, Tackling Housing Crisis and Inequity”; and Jenny Schuetz, “Minneapolis 2040: The Most Wonderful Plan of the Year,” Brookings Institution, December 12, 2018, https://www.brookings.edu/blog/the-avenue/2018/12/12%20/minneapolis-2040-the-most-wonderful-plan-of-the-year/.

- Flisrand interview I.

- Lee, “How Much Will Minneapolis’ 2040 Plan Actually Help?”

- Badger and Bui, “Cities Start to Question an American Ideal.”

- Badger and Bui, “Cities Start to Question an American Ideal” (citing Salim Furth of the conservative Mercatus Center).

- See Kahlenberg, Excluded, 174.

- Richard D. Kahlenberg, “Minneapolis Saw that NIMBYism Has Victims,” Atlantic, October 24, 2019, https://www.theatlantic.com/ideas/archive/2019/10/how-minneapolis-defeated-nimbyism/600601/.

- Alex Horowitz and Ryan Canavan, “More Flexible Zoning Helps Contain Rising Rents: New data from 4 jurisdictions that are allowing more housing shows sharply slowed rent growth,” Pew Charitable Trusts, April 17, 2023, https://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/articles/2023/04/17/more-flexible-zoning-helps-contain-rising-rents.

- Horowitz and Canavan, “More Flexible Zoning,” Figure 1.

- Horowitz and Canavan, “More Flexible Zoning,”

- Mark Niquette and Augusta Saraiva, “First American City to Tame Inflation Owes Its Success to Affordable Housing,” Bloomberg CityLab, August 9, 2023, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/features/2023-08-09/minneapolis-controls-us-inflation-with-affordable-housing-renting.

- See, for example, Yonah Freemark and Lydia Lo, “Effective Zoning Reform Isn’t as Simple as It Seems,” CityLab, Bloomberg, May 24, 2022, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2022-05-24/the-limits-of-ending-single-family-zoning; and Jake Blumgart, “How Important Was the Single-Family Zoning Ban in Minneapolis?” Governing, May 26, 2022, https://www.governing.com/community/how-important-was-the-single-family-housing-ban-in-minneapolis.

- Eliza Relman, “America, take note: New Zealand has figured out a simple way to bring down home prices,” Business Insider, August 7, 2023, https://www.businessinsider.com/america-lower-rents-home-prices-build-more-houses-new-zealand-2023-8.

- See Susan Du, “Minneapolis, developers to lose millions without 2040 Plan as judge’s order takes effect,” Minneapolis Star Tribune, November 5, 2023, https://www.startribune.com/minneapolis-developers-to-lose-millions-without-2040-plan-as-judges-order-goes-into-effect/600317445/.

- Drew DeSilver, “Chart of the Week: the most liberal and conservative big cities,” Pew Research Center, August 8, 2014, https://www.pewresearch.org/short-reads/2014/08/08/chart-of-the-week-the-most-liberal-and-conservative-big-cities/; and Sultan Khalid, “25 Most Liberal Cities,” Insider Monkey, July 6, 2023, https://finance.yahoo.com/news/25-most-liberal-cities-u-045200413.html.

- “Minneapolis, Tackling Housing Crisis and Inequity.”

- New York City Council, “Council Members and Districts,” https://council.nyc.gov/districts/

- Isa Alomran and Rob Todaro, “NYC Voters Overwhelmingly Want the City to Create More Affordable Housing and Prefer a Not-For-Profit, Public Approach,” Data for Progress, September 5, 2023, https://www.dataforprogress.org/blog/2023/9/4/nyc-voters-overwhelmingly-want-the-city-to-create-more-affordable-housing-and-prefer-a-not-for-profit-public-approach.

- In Bayside/Little Neck, 57 percent of lots ban anything other than a single-family detached home, compared with 12 percent of lots in Jamaica/Hollis that have the same restriction. See Richard D. Kahlenberg, “How Housing Policies Create Unequal Educational Opportunities: The Case of Queens, New York,” The Century Foundation, April 3, 2023, https://tcf.org/content/report/how-housing-policies-create-unequal-educational-opportunities-the-case-of-queens-new-york/.

- See Jason Sorens, ”The New Hampshire Statewide Housing Poll and Survey Experiments: Lessons for Advocates,” Center for Ethics in Business and Governance, Saint Anselm College, January 1, 2021, 11–12, https://www.anselm.edu/sites/default/files/CEBG/20843-CEBG-IssueBrief-P2.pdf.

- Lauren Wagner, “New Poll Finds Majority of Parents and Voters Favor Open School Enrollment, Elimination of Attendance Boundaries,” The 74, January 23, 2023, https://www.the74million.org/article/new-poll-finds-majority-of-parents-voters-favor-open-school-enrollment-elimination-of-attendance-boundaries/.

- See e.g. Casey Berkowitz, “Is a Better Community Meeting Possible,” The Century Foundation, August 20, 2019, https://tcf.org/content/commentary/better-community-meeting-possible/ (outlining ways to make public meetings more democratic).

- Horowitz and Canavan, “More Flexible Zoning.”

- Maggie Eastland, “The Suburb that defied NIMBY,” Wall Street Journal, August 15, 2023, https://www.wsj.com/articles/the-suburb-that-defied-nimby-a9bf4af9.