Most American cities suffer from a lack of affordable housing. Most American cities also have an intricate set of zoning regulations that restrict the types of housing that can be built in many parts of their municipality, which contributes to the problem of housing availability and affordability. These zoning regulations operate behind the scenes, unbeknownst to most residents, and typically serve to prevent denser housing, such as multi-family units or accessory dwelling units, from being built in single-family neighborhoods. Such restrictions also prop up educational inequity, restricting access to certain schools and contributing to segregation. And although historically it has been rare for cities or states to pass comprehensive, inclusive zoning laws that permit more housing stock and promote economic and educational opportunity, in 2021, the city of Charlotte, North Carolina became one of the few cities in the nation to adopt a wide scale inclusive housing reform plan.

Given that politics are often an obstacle to progress on housing reform, as they have been in New York, the case of Charlotte, North Carolina, is particularly instructive for coalitions tackling restrictive zoning elsewhere. Charlotte is a left-leaning metropolitan area in a conservative state. While Democrats control the Charlotte City Council and county board of commissioners in the region, Republicans dominate both houses of the state legislature and have overridden Democratic Governor Roy Cooper’s veto nineteen times this year alone.1 This is of particular note because while the state of North Carolina typically delegates land use policy to municipalities, the state holds ultimate authority, and it has not been shy about intervening in local zoning matters historically.2 And yet, despite this political landscape, the Charlotte City Council was able to pass a large-scale zoning reform plan in 2021 and follow-on legislation in 2022 without interference from the state.

This report is the continuation of a series examining successful housing reforms across the United States for the purpose of informing potential avenues for increasing the affordable housing stock and improving educational opportunity in New York and other similar states. This report focuses on Charlotte, North Carolina. Previous reports have examined reforms in Minneapolis, California, and Oregon, all of which preceded, and in some ways shaped, the efforts in Charlotte.

This report proceeds in several parts. First, it looks briefly at the political culture of Charlotte, and then explores the housing plan and follow-on legislative package that the Charlotte City Council passed. The report then dives into the details of the hard work done to ensure the reform’s passage in the council vote and then extrapolates lessons for New York State as well as implications for the future of housing reform.

A City That Believes in the American Dream

Despite the lack of unanimity on how to address the need for affordable housing in the context of a complicated political landscape, the Charlotte City Council was able to cobble together a coalition to pass significant housing reform in 2021 and 2022 aimed at creating more housing stock and setting the metro area on a path for sustainable growth over the next two decades. In Charlotte, the political conversations that ultimately gave way to reform were not solely focused on questions of housing affordability and availability, but also centered on matters of segregation, gentrification, and opportunity, with various political coalitions taking shape over the course of the debates. More than anything else, crucial to understanding the tenor of the debates in Charlotte is recognizing the value that Charlotteans place on living in a city that is meritocratic and where opportunity abounds—the ideas of American Dream and economic mobility featured perhaps more than any other topic in discussions about housing reform.

More than anything else, crucial to understanding the tenor of the debates in Charlotte is recognizing the value that Charlotteans place on living in a city that is meritocratic and where opportunity abounds.

Given that the American Dream and educational opportunity are deeply intertwined, conversations about education and schools were never far from the minds of Charlotteans, who also happened to be undertaking a comprehensive school boundary assessment at the same time as they were considering the new comprehensive land use plan. The school boundary analysis and some of the recommendations that ensued also inflamed the passions of local parents and evoked many of the same themes that the housing debates did. Despite the controversy on both the schools and the housing fronts, the comprehensive plan to overhaul zoning and the future of land use in Charlotte ultimately became law.

On June 21, 2021, the Charlotte City Council passed The Charlotte Future 2040 Comprehensive Plan (the 2040 Plan),3 which set in motion a series of reforms passed in 2022—the Unified Development Ordinance (UDO)4—that, among other things, allowed for multi-family housing, by right, across the city of Charlotte. The 6–5 council vote on the 2040 Plan mirrored how split public opinion was in the Queen City (as Charlotte is known), especially on the issue of zoning. Residents in support and in opposition came out in droves to voice their opinions on the reforms at hand. The victory for advocates came after years of pressure and work, even if the progress was not always linear.

For advocates, promoting inclusionary zoning by allowing for multifamily housing in areas where it was previously restricted represented creating new opportunity, often for low-income families and renters, and demonstrated a real effort to undo a legacy of discriminatory practices that locked people of color out of certain affluent parts of Charlotte for generations. For detractors, “eliminating single-family zoning” represented an affront to the character of historic neighborhoods and was carte blanche approval for developers to make even more money than they already did.

In the end, the story of how the reforms ultimately succeeded is instructive for the State of New York and other communities exploring how to improve affordable housing and educational opportunity, particularly in politically and racially diverse environments. Much like Mecklenburg County (of which Charlotte is the county seat), the State of New York is solidly blue and overwhelmingly votes Democratic; yet, in both places, there are crucial constituencies of moderate Democrats and a vocal Republican minority whose arguments frequently appeal across party lines. Both places have urban segments with pockets of high-traffic commercial areas and dense residential dwellings, as well as an abundance of suburban single-family neighborhoods. Both Charlotte and New York have seen dramatic increases in new residents recently, with New York’s increase due largely to a rapid influx of recent immigrants. Thus, the case of Charlotte is instructive for New York and other politically mixed-but-left-leaning geographies with a mix of urban and suburban residents, and increase in new residents.

A Bold Land Use Reform Package for Charlotte

The policy framework that precipitated massive changes to zoning that would be enshrined in the city’s Unified Development Ordinance is known as The Charlotte Future 2040 Comprehensive Plan. Understanding what both the 2040 Plan and the UDO set forth is critical to grasping the broader context of how these reforms were ultimately passed and what their impact will be in the future.

One key component of the state legislation was the requirement that local governments establish, if they had not done so already, comprehensive plans for their zoning regulations, or risk losing the authority to regulate zoning.

In 2019, the North Carolina legislature passed Chapter 160D, legislation that modernized and streamlined zoning processes from locality to locality in order to bring some order and consistency across the state.5 One key component of the legislation was the requirement that local governments establish, if they had not done so already, comprehensive plans for their zoning regulations, or risk losing the authority to regulate zoning. And while Charlotte’s effort to create a comprehensive plan preceded the legislation (engagement began in 2018), the new law provided a further spark—and a deadline of July 1, 2022— for the creation of the 2040 Plan.6 The effort was spearheaded by members of Charlotte’s City Manager team, specifically its director, Taiwo Jaiyeoba, who played an instrumental role in crafting and communicating about the plan.

Before the 2040 Plan, Charlotte had not had a comprehensive plan for land use since 1975. Many provisions of the 1975 plan were obsolete or not capable of guiding future development in the Queen City. The goal of the 2040 Plan was to create “a blueprint for a city’s next phase, a statement on a community’s character, and a guiding light for determining a community’s goals and aspirations for the future.”7 The document establishes both a policy framework for land use and signals commitments related to infrastructure and investment over the next twenty years.

To arrive at the final product, the city conducted extensive community outreach, spanning three years and reaching thousands of residents. According to the city, the planning team “had over 500,000+ interactions with over 6,500 voices through more than 40 methods of engagement [and an] additional 477 key stakeholders, including community leaders, local business and non-profit representatives, advocacy groups, major employers, local institutions, and neighborhood groups from across Charlotte.”8 Following this engagement, the 2040 Plan was passed in June of 2021.

The 2040 Plan is a lengthy and aspirational document that establishes several goals for the city’s development over the next twenty years, including goals for transit development, housing access, safety, fiscal responsibility, economic opportunity, and proximity to essential services. Far and away, the focal point of discussions during its consideration was the second goal titled “Neighborhood Diversity and Inclusion,” which states “Charlotte will strive for all neighborhoods to have a diversity of housing options by increasing the presence of middle density housing (duplexes, triplexes, fourplexes, townhomes, accessory dwelling units, and other small lot housing types) and ensuring land use regulations allow for flexibility in creation of housing within neighborhoods.”9

For each goal, such as the goal about neighborhood diversity, the 2040 Plan includes a set of objectives, big policy ideas as well as suggested regulatory, investment, and project ideas. These are intended to serve as a policy framework and recommendations for actual policy, which would later come in the form of the city’s UDO, a detailed policy and regulatory regime describing exactly what could be built where. Among the policies and ideas recommended by the 2040 Plan regarding housing and zoning, the plan recommends allowing single-family, duplex, and triplex housing where previously only single-family housing was allowed; allowing fourplexes adjacent to arterial passageways; and requiring larger developments to include a mix of housing types, among others.10

One year after the 2040 Plan was passed, the city council passed the UDO in August of 2022, which codifies with much more specificity the reforms outlined and suggested by the 2040 Plan. The UDO rezones what was previously R-3, R-4, R-5, R-6, R-7, and R-8 districts, which were all single-family housing zoning with various sub-specifications around minimum lot sizes, widths, and setbacks, to N1-A, N1-B, N1-C, and N1-D, which now allow single-family homes, duplexes, and triplexes by right.11 Other technical changes were also made, such as eliminating certain zones that no longer made sense, and consolidating other zones with new, updated regulations.12 Finally, the various “place types” (for example. Neighborhood, Commercial, Campus, Parks and Preserves, and so on) outlined in the 2040 Plan were codified and given regulations in the UDO. “Each Place Type includes a description of the desired development and key characteristics for that place” and “identifies primary and secondary land uses appropriate for an area,” according to a UDO public document.13

Before the UDO took effect, 84 percent of Charlotte’s residential land was zoned for detached single-family homes.

In short, before the UDO took effect, 84 percent of Charlotte’s residential land was zoned for detached single-family homes. After UDO went into effect, the vast majority of that residential land was made available for duplexes and triplexes without any special authorization needed from a land use authority.14 The implications for Charlotte were that significantly more housing stock could be made available, if homeowners and developers took advantage of the legal ability to build multifamily housing, either by adding to existing single-family structures, or building new. It also meant that if new housing stock became available in previously exclusive areas, there would be new avenues for parents to get their children into a high-performing school other than buying an expensive single-family home.

Yet that was not the only way access to certain schools was changing in Charlotte. At the same time that the 2040 Plan and the UDO were passed, Charlotte–Mecklenburg Schools were completing a boundary analysis that would lead to a rezoning that passed the school board within days of the UDO being passed. Ultimately, the plan changed feeder patterns and school zones in South Charlotte to accommodate overcrowding in that part of the city and align to the construction of two new high schools, affecting twenty-seven different schools and hundreds of families.

The new housing policies and school policies took effect around the same time. Although the UDO was passed in August of 2022, its policies and regulations first took effect recently, on June 1, 2023. The school rezoning passed in early June 2023 and took effect at the beginning of the 2023–24 school year.

Getting to Six: How Charlotte’s Ambitious Housing Reform Passed in City Council

For legislation to pass the Charlotte City Council, a minimum of six “yes” votes are required to reach a majority of the eleven-member body. Seven members are elected from the seven council districts and four members are elected as at-large members who represent the whole city. In 2021, the council was extremely diverse, with five African-American members, four white members, and two Asian-American members. Two of the eleven members were Republicans, representing specific council districts of Charlotte.

The vast majority of residents understood the need to do something about Charlotte’s booming population, but the city remained divided on exactly what to do.

Although the reform was championed by Charlotte’s Democratic mayor, Vi Lyles, it was not always clear that there would be majority support on the council for such a dramatic overhaul of the city’s zoning ordinances. The vast majority of residents understood the need to do something about Charlotte’s booming population, but the city remained divided on exactly what to do. Some argued that liberalizing zoning laws would empower developers, degrade Charlotte’s character, and promote gentrification and displacement, while others believed it would begin a new era of affordable options in the Queen City. Ultimately, reform succeeded because the champions of the 2040 Plan were able to win over some Charlotteans who were initially skeptical of the effort, by including certain provisions and structures in the proposal to assuage concerns about displacement and gentrification.

Historical Context and Key Personalities

Although regulation of land use in North Carolina dates all the way back to the colonial era, modern regulations came into force in earnest in the early twentieth century as a way to enforce the segregation of African Americans. As Richard Rothstein notes in The Color of Law, “To prevent lower-income African Americans from living in neighborhoods where middle-class whites resided, local and federal officials began … to promote zoning ordinances to reserve middle-class neighborhoods for single-family homes that lower-income families of all races could not afford.”15

This is exactly what happened in Charlotte, as neighborhoods petitioned the Charlotte City Council for specific zoning regulations that would exclude undesirable populations. The problem was further exacerbated by redlining, a practice the Homeowners Loan Corporation engaged in that excluded residents of specific parts of the city—almost always those populated by nonwhites—from receiving credit to purchase homes or improve their neighborhoods. Finally, the city systematically under-resourced and underinvested in poor neighborhoods, creating a dual reality for Black and white citizens in Charlotte. A study analyzing the effects of zoning on the historical development of residential land in Mecklenburg County found that “low density zoning has aggravated social stratification,” creating patterns of low density residential subdivisions in certain areas, and high concentrations of poverty in others.16

For Mayor Lyles, the historical shadow cast by the legacy of discrimination in housing was always present in the city’s efforts to expand opportunity to all residents.

For Mayor Lyles, the historical shadow cast by the legacy of discrimination in housing was always present in the city’s efforts to expand opportunity to all residents. In a particularly heated Charlotte City Council meeting, councilmember Ed Driggs pushed back against the notion that opposition to CF 2040 was segregationist and asked, “what percentage of the population of Charlotte today was a party to any kind of redlining?” The mayor retorted, “I’ve been here since 1969. A bulldozer did come down, with a white guy in a suit, tearing down a neighborhood. So it’s kind of hard for me to forget about those things.”17

Lyles’ political ascendancy coincided with some significant events in Charlotte, specifically, the murder of Keith Lamont Scott by a Charlotte–Mecklenburg police officer, statewide legislation targeting the LGBTQ community, and the release of a report by then-Harvard economist Raj Chetty ranking Charlotte dead last among fifty large cities for economic mobility.18 Consequently, Lyles sought a mandate for significant reform that would level the playing field for low-income and Black Charlotteans, and her big bet was on housing. Not only was housing a centerpiece of Vi Lyles’ campaign, as mayor, she tripled the amount the city raised in bonds for affordable housing in 2018, and sought even more radical change in the form of a comprehensive plan.19

The person tasked with developing and overseeing the progress of Charlotte’s comprehensive housing plan was Taiwo Jaiyeoba, the city’s planning director at the time. Jaiyeoba, who was named “Charlottean of the Year” in 2020, ended up becoming controversial in some quarters, as the 2040 Plan garnered more attention the closer it got to a city council vote, and Jaiyeoba was seen as the face of the plan.20

Jaiyeoba traces his roots to his childhood in Nigeria, where homes and streets in his town were deliberately planned to encourage interaction and community. After stints in various public transit and planning agencies across the United States, Jaiyeoba was hired as Charlotte’s planning director in 2018. As the city planner, he was responsible for engaging the community, drafting the plan, and shepherding it through the political process. Like Lyles, he was also motivated by a sense of righting historical injustice, “If we don’t have a vision that challenges some of our past in order to deal with today’s issues, then what are we doing?” he said in an interview.21

“If we don’t have a vision that challenges some of our past in order to deal with today’s issues, then what are we doing?”

As the 2040 Plan garnered more attention, so did Jaiyeoba, and at times, he had to confront some ugly behavior directed his way, such as when he overheard a resident asking why someone who is “not even from here” was trying to change denizens’ “way of life,” according to an interview he gave in 2021.22 This would foreshadow some of the racist dog whistles that accompanied the debate about the 2040 Plan. He also had to contend with some politicians’ portrayal of him as an activist bureaucrat, making decisions that he was not elected to do—a common critique from Republicans seeking to reign in the powers of government.

Housing Stock and the Queen City’s Reputation: The Impetus for Reform

There were several factors that spurred the development of a long-term housing and development plan for the Charlotte region. First and foremost, city leaders were clear-eyed about the fact that Charlotte’s population was booming and that the city simply was not creating housing stock fast enough. Second, the Charlotte metropolitan area has historically prided itself on its reputation as a diverse and inclusive community where opportunity abounds, despite the scourges of racial discrimination and segregation in its past. Most obviously, this pride manifested itself in the efforts to integrate the schools across Charlotte–Mecklenburg, despite setbacks in recent years. But additionally, many Charlotteans saw their city as a place where access to the American Dream should be available to everyone, and the notion that it was slipping away from folks in Charlotte was enough to convince people that action needed to be taken.

Many Charlotteans saw their city as a place where access to the American Dream should be available to everyone, and the notion that it was slipping away from folks in Charlotte was enough to convince people that action needed to be taken.

Charlotte, the fifteenth-most populous U.S. city, with a population of nearly 900,000, has been one of the fastest-growing cities in recent years, mirroring the national trend of growth in other Southern and Western cities.23 Data from the Brookings Institution’s Jacob Frey show the Charlotte metro area in the top ten for population growth among the fifty-six largest metro areas in the United States in each of the past three years, with significant population growth in the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic (+31,389) in comparison to metro areas such as Chicago, San Francisco, and Los Angeles, which lost between 90,000 and 174,000 residents each between 2020 and 2021.24

Charlotte’s historic growth rate is not expected to slow anytime soon. Charlotte city government predicts that the city’s population will increase by 385,000 over the next two decades.25 Meanwhile, Charlotte’s housing stock has not kept pace with its population growth. A report from the Cato Institute in 2022 showed that between 2010 and 2020, Charlotte–Mecklenburg’s increase in housing units lagged behind its population increase.26 The concern about housing is also reflected in polling, as a Carolina Forward poll from 2021 showed that 75 percent of urban North Carolinians agree that there exists a crisis of housing affordability.27

The major impetus for reform was the simple calculus that, without a clear plan for the future of land use in Charlotte, the growing city would not be able to meet the demand for housing for new residents. City councilmember Julie Eiselt said, “no matter what we do or don’t do, we will … need more housing of all types in all parts of town for all people and to accommodate the current residents as well as the 400,000 people that are expected to move here in the next 20-years.”28 The need for housing for new residents in Charlotte is felt almost as acutely as the need for housing to address the migrant crisis that has engulfed New York City in the past year.29

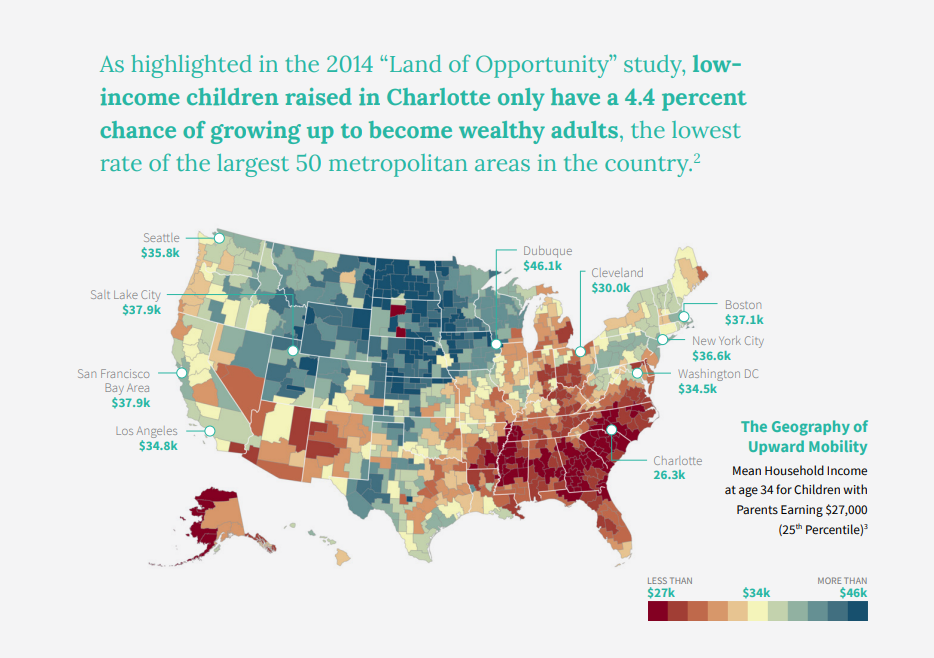

In addition to the very tangible issue of affordable housing stock, upholding a perceived reputation was extremely important to key decision makers in Charlotte. One blow to their reputation in prior years was the results of then-Harvard economist Raj Chetty’s research from 2014, which ranked the Charlotte region fiftieth out of fifty large metropolitan areas in terms of upward economic mobility.30 Specifically, the study showed that children born into poverty in the Charlotte area had less of a chance to make it out of poverty than children born into poverty in all other regions studied. “The research revealed that only 4.4 percent of the low-income children that grow up in the Queen City and the surrounding region will go on to become high-income adults—the lowest rate of the 50 largest metropolitan areas in the country,” summarized an excerpt from a follow-up study that stakeholders in Charlotte commissioned Chetty and team to conduct.31 Given the segregation in housing that exists in Charlotte, the finding on the lack of upward mobility for low-income residents had major implications for the city’s housing stock and its relationship to opportunity. The study led to a lot of hand wringing in the Charlotte area, as well as a desire to actually do something.

“When I first read about the ‘Land of Opportunity’ study and Charlotte’s 50th out of 50 ranking, I knew it had the power to change the conversation in our community. Not only was it damning research about mobility outcomes for children born in our community, but it struck at the very core of Charlotte’s persona—a place where meritocracy rules and everyone has a fair shot at the American Dream,” said Brian Collier, an executive at the Foundation for the Carolinas.32 The Chetty research went right to the heart of Charlotte’s identity and was a powerful impetus to do something about the problem. The research was repeatedly mentioned in city council deliberations about the 2040 Plan plan, by proponents and opponents alike. For example, councilmember Renee Johnson, who ultimately voted against the plan, still demonstrated that the data point was very much on her mind, “We all know that Charlotte was ranked 50 out of 50 in upward mobility and this plan was to reduce the inequities in the city.”33

Figure 1: Limited Upward Mobility in Charlotte

Of the three major policy areas of focus suggested by the Chetty follow-up study in 2020, one read: “using housing policy to deconcentrate poverty and reduce segregation.”34 Specifically, the study encouraged the city to ensure targeted construction of affordable housing in high opportunity areas and reform land use and regulation via a comprehensive city planning process.

The term segregation was not a word solely used in the Chetty report—it actually featured in some of the debates about the proposed housing reform. In part, because of Charlotte’s long history of segregation, proponents felt this plan would go a long way in overcoming residential segregation in the Queen City and open paths for more diverse and integrated communities. In some cases, plan proponents went further, accusing opponents of upholding segregation. City councilmember Braxton Winston posted, “Single family zoning is a tool of segregation. If you are fighting to maintain single family zoning you are advocating for segregation. Stop being racist, Charlotte,” on X (formerly Twitter) amidst the ongoing debates about the 2040 Plan.35

Opponents of the plan greatly resented the segregationist accusations. City council member Driggs, who is white, said, “I would also like to note that people who live in single-family neighborhoods today are simply choosing a lifestyle, perhaps wanting to own a house where they can raise their kids or enjoy some privacy. They come from all walks of life, all races, all ages, and they are good people. In this day and age, they do not deserve to be tagged with this segregationist label.”36 Other opponents, such as Republican councilmember Tariq Bokhari, made comments that some interpreted as racial dog whistles, for example, when he said “Charlotte is going to become all the bad parts of living in Atlanta,” referring to a city with the fourth-highest percentage of African Americans among cities with at least 400,000 residents.37 Nonetheless, the explicit association with segregation was clearly one that all parties wanted to distance themselves from, in large part because it contradicted the ethos of what Charlotte aspires to be. Finally, it was not only non-Black or non-Democratic councilmembers who were opposed to the plan. Council member Victoria Watlington, who is Black and a Democrat, said, “It’s also extremely disrespectful to suggest that Black neighborhoods and Black homeowners like myself that live in these neighborhoods in question are racist against our own desires.”38

The explicit association with segregation was clearly one that all parties wanted to distance themselves from, in large part because it contradicted the ethos of what Charlotte aspires to be.

The city’s storied past regarding school desegregation is critical to understanding the desire that many Charlotteans have for their city to embody inclusiveness and belonging. As a result of landmark litigation in Swann v. Charlotte–Mecklenburg Board of Education, the school district pursued a sweeping busing agenda that served to desegregate schools for decades.39 An oft-recalled moment in Charlotte history is the campaign stop that Ronald Reagan made in Charlotte in the 1980s, when he recited a line from his stump speech criticizing school desegregation efforts and was met with a deafening silence from local residents, as opposed to the applause he was likely anticipating. His critique did not resonate. It struck such a nerve that the Charlotte Observer editorial board published a piece on the following day with the title, “You Were Wrong, Mr. President,” and went on to state, “Charlotte–Mecklenburg’s proudest achievement of the past 20 years is not the city’s impressive skyline or its strong, growing economy. Its proudest achievement is its fully integrated schools.”40

Unfortunately, the progress the school district made in the three decades following Swann has been followed by backsliding, as the era of busing has given way to an increase in segregation. This fact illuminates another truth about Charlotte’s self-image: the desire to be seen as a city that extends opportunity to all has not always translated into concrete policy changes to make that a reality. And although there are many pockets of support for integration still evident in the community, the district remains heavily segregated. In 2016, the Board of Education for Charlotte–Mecklenburg Schools unanimously passed a policy designed to use socioeconomic status to combat segregation in its schools.41 In a recent rezoning effort, one parent in an affluent part of Charlotte remarked, “We want balance. We have been very careful to look only at the data provided by CMS [the school district] to make sure we are using accurate figures and bring actual solutions to the board. We deal in facts, and the facts show balanced and diverse schools succeed.”42 But despite this deep history of desiring integration, not all parents are willing to push for racial balance.

Historically, the commitment to address segregation in public schooling did not extend to significant action on housing in Charlotte. Charlotte’s long history of redlining and segregation was frequently referenced in the community engagement for the 2040 Plan and appeared in the final document as an entire section, titled “Divisions and Inequity: How We Got Here.” Advocates for reform clearly felt that the 2040 Plan could address the city’s legacy of redlining and segregation in housing and speak to the vision that ordinary Charlotteans have for their city, as a place that is a beacon of opportunity, regardless of race or class.

Unusual Bedfellows Opposing Reform

The passage of the 2040 Plan was not guaranteed, and the path often felt perilous. As Richard Kahlenberg has noted elsewhere in this series, Democratic majorities are not guarantees of political success when it comes to housing reform. In fact, the voting patterns of the places in New York that were most vocally opposed to Governor Kathy Hochul’s proposed housing reforms, such as Westchester County,43 closely resemble that of Charlotte Mecklenburg. For example, in the 2020 presidential election, Biden bested Trump in Westchester County 61 percent to 38 percent. Similarly, in Mecklenburg County, Biden won 67 percent to 32 percent.44 Additionally, some of the same dynamics were at play in Charlotte: many wealthy Democrats were skeptical of reforms that might impact their housing values, and the conservative minority attempted to make arguments that would appeal to voters across party lines, particularly to residents of Charlotte’s outer ring and suburbs, whom they felt would be more protective of the status quo. And while it was the city of Charlotte itself that had to pass the 2040 Plan, the county controlled important functions that would impact its ultimate success, such as approving capital improvement plans for schools and public spaces, approving the school district’s budget, and making various investments in combating housing insecurity.

Opponents of the reform focused on three key concerns: first, that the plan would somehow erase single-family homes from the city and thus jeopardize the American Dream of homeownership that Charlotte prided itself on providing to citizens of all stripes; second, that the residents of Charlotte would somehow have rights taken away from them; third, that the plan would lead to gentrification and displacement. The first two critiques—degrading the American Dream and losing rights—were arguments mostly furthered by conservative-leaning Charlotteans and residents in wealthy neighborhoods; whereas, concerns about gentrification and displacement, which were paid lip service by all opponents, were most passionately and substantively argued by residents of Charlotte’s primarily Black and low-income “crescent.” And so, opposition to the 2040 Plan reform plan comprised this pairing of otherwise disparate communities.

The argument that the reforms would actually undercut the American Dream fell flat with the greater public.

The argument that the reforms would actually undercut the American Dream fell flat with the greater public because of an inherent contradiction in the two primary points that conservative-leaning Charlotteans argued about the 2040 Plan simultaneously. For one point, opponents argued that the reform would result in changes to the “character” of many Charlotte neighborhoods, leading to lower housing prices and thus threatening a principle tenet of the American Dream that with enough thrift and hard work, anyone can own a single-family home that appreciates in value over time. Lorena Castillo-Ritz, the chair of the Mecklenburg County Republicans, argued that a vote for allowing for duplexes, triplexes, and in some cases quadruplexes in areas previously zoned for single-family housing was a vote against the American Dream.45 “I came to buy the American dream. I lived it. My parents lived it. I want my kids to live it,” she said at a rally before the city council meeting.

Simultaneously, many conservatives joined with some Democrats who questioned whether or not the city had enough data to even conclude that the housing reforms would actually lead to more affordable housing. In the consequential city council meeting where the vote on the 2040 Plan actually took place, Republican city councilmember Ed Driggs stated, “We’ve been pursuing ideas and goals and values, but when it comes down to it we don’t know how many cities have already adopted this plan, what evidence there is that the plan made any difference when it comes to their housing costs.”46 His Republican colleague Tariq Bokhari went further, stating, “I truly believe in my heart that this is one of the most dangerous threats to the future affordability of housing in Charlotte.”47 In furthering both arguments, that the proposal would reduce property values and that there was not enough data to know if it would lead to greater affordability, conservatives were trying to have their cake and eat it too, dooming a coherent message on why residents should oppose the plan.

One move by opponents of the reform that was somewhat more effective was how they attempted to frame the terms of the debate, specifically as it pertained to single-family zoning. Instead of conceding the fact that the reforms would permit new types of housing on land traditionally reserved for single-family homes, they instead framed it as a “banning” or “elimination” of single-family neighborhoods. Such framing is exemplified by councilmen Driggs, who said “the provision that eliminates single-family neighborhoods is the main source of contention among members of the Council and more importantly among the citizens of Charlotte.”48 He went further with the notion that the council was taking something away from citizens wholesale, saying, “the plan completely disenfranchises those who oppose this provision by failing to contemplate a less radical solution than reducing single-family zoning from 70% of our land area to zero. Why? Why does it have to do that? Why can’t we move in that direction and not convert 70% of the City all at once?” In reality, no homeowner of a single-family dwelling would have their home type “banned,” nor would they be forced to change anything about their home, yet the opponents’ language whipped up fear among some residents that something would be taken away from them if this plan was passed.

Many Republicans also advanced the idea that enabling duplexes, triplexes, and in some cases quadruplexes in parts of the city “by right,” or without any type of special approval, would rob residents of their ability to hold developers accountable for creating structures in their neighborhoods that they opposed. “As it stands now most of our rezoning is conditional, which means that there is a mandatory community meeting at which citizens can learn about a proposed development and express any concerns they may have,” explained council member Driggs.49 The councilman goes further, framing it as a denial of rights: “Before taking this recourse away from the people of Charlotte we should ensure that this Council and future Councils continue to involve themselves in controversial development proposals rather than have outcomes decided entirely by rules created and interpreted by the City staff.”50

A community that typified the opposition to the reform is a wealthy community called Myers Park, just south of Uptown Charlotte. In Myers Park, 88 percent of residents are white and less than 3 percent are Black.51 The median family income in Myers Park in 2021 was $181,076, almost two and a half times the national median family income.52 Detached single-family homes composed 85 percent of units in Myers Park in 2021 and the average value of these homes was $1.76 million.53 When it came time for the city to consider the 2040 Plan, many leaders in Myers Park spoke out against the changes, fearing it would spoil the character of the neighborhood. The summer 2021 edition of the Myers Park Improvement Association’s newsletter featured a guest column from Myers Park resident and former North Carolina Governor Pat McCrory, who wrote this to his fellow residents about the 2040 Plan: “Now sadly, our city government, through the 2040 plan, is destroying the best laid plans for our neighborhood and our city. Eliminating single family zoning and increasing density outside of transit corridors throughout Charlotte is governmental overreach and social engineering at its worst. It is bad for our environment and it recklessly divides our citizens with false and misleading narratives.”54 Many of McCrory’s Myers Park neighbors heeded the call to resist the 2040 Plan and submitted public comments opposing the plan.55

The notion that Charlotteans were having rights taken away from them was not an argument that was furthered solely in the housing debates—residents who were disgruntled by the school rezoning efforts in South Charlotte also deployed similar language. “We chose our neighborhood because we wanted [our daughters] to go to the three specific schools,” said a parent in the Myers Park community.56 The argument rested on the idea that buying into certain neighborhoods gave families rights that should not be taken away from them. In the case of the housing reform, they feared they would lose the right to live in a neighborhood of exclusively single-family homes. In terms of schools, they feared they would lose the right for their children to attend the school that they “bought into,” and thus that their children would miss out on a certain kind of education experience—a specific slice of the American Dream.

Many community members were concerned about the potential impact that the reforms would have on a different issue: gentrification and the ability for existing Charlotte residents to remain in their neighborhoods.

Many community members were concerned about the potential impact that the reforms would have on a different issue: gentrification and the ability for existing Charlotte residents to remain in their neighborhoods. “Under this plan, it is not a matter of whether gentrification will accelerate but a matter of how much more it accelerates,” said Councilmember Matt Newton, a Democrat, on the day of the vote.57 He further assailed the plan, stating:

[This plan] proclaims to exact equity, inclusion, and opportunity within our City, but will in reality exact the opposite on many of our most vulnerable residents, especially in communities of color…when you allow developers to build two, three, and even four times as many units wherever they want without them ever having to meet with the community…[or] a mechanism to mandate affordability or homeownership in those units, it is the greedy developers and investors who win and not the community.58

The concerns about gentrification and displacement were acutely felt by residents of Charlotte’s low-income and mostly Black neighborhoods. A coalition of some thirty grassroots groups in Charlotte’s lower income “crescent” called the “Community Benefits Coalition” pushed back on the 2040 Plan arguing specifically that there needed to be some assurances about displacement and community input into the framework in order for them to be on board.59 Ismaail Qaiyim, founder of Charlotte’s Housing Justice Coalition explained the concerns about gentrification and displacement, stating,

When you look at the things causing displacement in the city, really it has to do with uncontained and unrestrained market forces and investment blowing into areas that haven’t seen investment in a very long time…. So even if you increase the housing stock, the problem is that the entities that are building the housing stock are building toward the highest market value because it’s driven toward maximizing profit.60

Many residents who were concerned about gentrification and displacement signaled that they were open to mechanisms to increase housing stock and thereby improve affordability, but they wanted city leaders to pay more attention to ways of protecting the residents of areas that might be targeted by developers, particularly with the new opportunities to build more lucrative types of housing in a new zoning environment.

The Charlotte Future 2040 Comprehensive Plan Passes, Followed by Adoption of the UDO

In order to pave the way for success, supporters of the housing reform found ways of dispelling some of the arguments put forth by staunch opponents, while offering concessions to residents who wanted more protections against displacement. This strategy helped them win over some of the “persuadables,” while neutralizing the hardcore opposition. Additionally, supporters were able to get key constituencies to buy into the greater vision of the 2040 Plan, specifically real estate and developer constituencies.

In response to questions about whether the plan would actually lead to more affordability, proponents of the plan leaned on common sense. “Increasing housing supply is a tried and true method of increasing affordability,” said Sam Spencer, the chair of the planning committee in Charlotte.61 These kinds of messages resonated with many Charlotteans, particularly the 31 percent of whom are rent-burdened.62 The literature on the economics of housing supply supports this common sense argument. As Michael Tanner summarizes in his report on housing affordability in North Carolina, “the academic literature overwhelmingly concludes that restrictive zoning decreases the supply of housing, raises the cost of construction, and increases housing prices,” and that “the same holds true in reverse; a decrease in zoning restrictions would increase supply and reduce price.”63 Moreover, even if the new housing built is expensive relative to the existing housing stock, as opponents of reform argued, an increase in multifamily housing still increases the overall supply of housing, providing more relief and less competition for the existing housing stock.

The academic literature overwhelmingly concludes that restrictive zoning decreases the supply of housing, raises the cost of construction, and increases housing prices…the same holds true in reverse; a decrease in zoning restrictions would increase supply and reduce price.

To assuage the concerns about gentrification and displacement, the plan was amended to include several key provisions. First, the 2040 Plan recommends the formation of an “anti-displacement commission” to specifically “recommend tools and strategies for protecting residents of moderate to high vulnerability of displacement.”64 Additionally, the plan calls for an investment of 50 percent or more of the infrastructure spending to be spent in historically underserved communities.65 And while community activists did not get everything they wanted in the plan, there was enough assurance that there would be built in protections to win the support of key council members. (Notably, Charlotte released the “Anti-Displacement Strategy Report” in August of 2023, fulfilling a key promise that won over many advocates concerned about displacement.)66

A major win for the coalition advancing the proposed reforms in the 2040 Plan was the softening of opposition from the developer and business community, which had initially been staunchly opposed to moving the plan forward. In March of 2021, the Real Estate and Building Industry Coalition in Charlotte (REBIC), initially opposed moving the plan forward, citing the availability of more time for making a decision, the need for deeper analysis, and bemoaning the lack of developers at the table in crafting the policy.67 The specific sticking point for most developers was their concern that any future UDO would be laden with new impact fees and additional costly burdens as they attempted to comply with new regulations. They even launched a campaign called “Let’s Get It Right Charlotte,” that encouraged residents to urge a “no” vote on the 2040 Plan.68 The morning of the planned vote, however, chairman of REBIC, Alan Banks, appeared on the local Charlotte Talks radio programming signaling REBIC’s support of moving the plan forward, as some of the sticking points, such as the use of impact fees, had been removed from the plan, and a promise that an economic analysis would be forthcoming in the future. “Council has done a good job in working through some of the details of the plan, for example, the elimination of a height restriction in Uptown Charlotte. . . . There’s been great improvements in this plan, that’s why at this point, we’re in favor of moving ahead,” said Bank that morning.69

In the end, the hard work paid off. With Mayor Vi Lyles presiding, the council adopted the 2040 Plan with a vote of 6–5, and the path was paved for one of the most significant zoning reforms in the country.

Table 1

| CHARLOTTE CITY COUNCIL VOTE ON THE 2040 PLAN | |

| City Council Members Voting FOR Charlotte 2040’s Adoption | City Council Members Voting AGAINST Charlotte 2040’s Adoption |

| Dimple Ajmera (Democrat, Asian-American, at-large)

Larken Egleston (Democrat, White, 1) Malcolm Graham (Democrat, African-American, 2) Greg Phipps (Democrat, African-American, at-large) Braxton Winston (Democrat, African-American, at-large) Julie Eiselt (Democrat, White, at-large) – Mayor Pro Tem |

Tariq Bokhari (Republican, Asian-American, 6)

Ed Driggs (Republican, White, 7) Renee Johnson (Democrat, African-American, 4) Matt Newton (Democrat, White, 5) Victoria Watlington (Democrat, African-American, 3) |

Notably, the adoption did not happen along racial lines, with African American, white, and Asian American council members voting on both sides of the issue. Within one year of the passage of the 2040 Plan, the council passed the UDO, the set of rules and regulations that codified the zoning changes and set the rules of the road for the coming years, by a 6–4 vote.70

Implications for the Future

Charlotte’s reforms are very fresh. The policies and regulations that carry out the 2040 Plan, known as the UDO, took effect on June 1 of this year. Consequently, there is little reliable data to inform how the changes have affected Charlotte so far. For instance, data on new housing permits, which the census bureau collects monthly and is available through August of this year, does not show significant differences in pre-June permits for multi-family housing issued in comparison to June, July, and August, but the time horizon is too short to be able to make sweeping judgments about the reform’s impact.71 It is also important to note that a future city council could pare back or reverse the UDO that last year’s city council codified. Notably, while Mayor Vi Lyles was re-elected in November, several pro-UDO members of the council were not re-elected or resigned.72 Nonetheless, any multifamily housing developed while the policy is on the books would still increase housing stock in the Queen City.

Despite the recency of the reforms, there are some lessons to be learned from the process of getting the zoning changes successfully legislated. First and foremost, the work in Charlotte spoke to the character of the city, as a place that prided itself on being a city of opportunity, a community that prided itself on its diversity, and one that desperately wanted to overcome its historical legacy of segregation. Tying housing reforms to the essential narrative of a place—whether its about affordability, inclusion, opportunity, or some other dearly held identity—helps frame the conversation as one that is about more than mundane policy concerns, but rather one that affirms the pride that residents feel in being associated with their city.

Secondly, supporters led with common sense and easy-to-understand messages about what they were trying to achieve. More inclusive zoning leads to more housing. More housing results in greater affordability. These concepts make sense, are easy to digest, and resonate with the harsh reality of how expensive urban life is all across America. Finally, leaders in Charlotte took great pains to win over constituencies that were initially skeptical of the reforms. For example, leaders acknowledged the fears that many in the community had about gentrification and displacement. In response, they infused meaningful protections in their reform agenda, and ensured the community that equity would be centered in the process. A subsequent report demonstrated a thoughtful approach to anti-displacement, focusing on supporting residents through stability, strengthening communities, and empowering businesses, among other strategies.73 Leaders also won over the developer community, by cutting back some regulations and requirements that developers thought would be too costly, but that did not impact the broad strokes of the reform they intended to pass.

One note of interest—it was the state of North Carolina mandated that localities pass comprehensive plans that clarified their zoning regulations and set forth a comprehensive vision for future land use, which spurred places such as Charlotte to codify their vision for the future. The state did not set parameters for how that zoning had to look, and yet, it created a public conversation about zoning and affordable housing, without mandating specific changes. In states where comprehensive reform at the state level has failed, such as in New York, states might consider an approach that at least requires some clarification, standardization, and future planning, which in and of itself might spur reform.

For policymakers hoping to translate the legislative victory in Charlotte to other cities, there are also some considerations to be made about the ways in which Charlotte, a sprawling Southern metro area with a booming population, is different from many urban areas in the northeast. In fact, some opponents of the 2040 Plan used those differences to argue against the zoning reform. Councilmember Newton stated, “our land area is more than twice the size of Detroit and Portland and more than five times the size of Minneapolis … [places where] it is much easier to construct, deliver and maintain essential services and amenities. However, in a sprawling land area like Charlotte’s, it is more difficult if not impossible to do this the same.”74 Conversely, the fact that places like New York are much more dense and therefore easier to have essential services accessible via public transportation, make implementing more inclusive zoning more feasible.

At the end of the day, the Queen City is only one of a handful of major U.S. cities to have undertaken such sweeping changes to its zoning laws. While there are certainly lessons to be taken about the strategy behind getting the reforms passed, the actual impact of the reforms will not be known for some time, and is sure to be watched closely by cities across the country. But perhaps most importantly, this Southern city managed to pass a set of reforms designed to address historical discrimination, combat segregation, and create more affordable housing options, when most cities in the North have not taken concrete steps in that direction.

Rudrani Ghosh contributed research and editorial assistance in the writing of this report.

Notes

- Alex Baltzegar, “NC legislature adds to growing list of overridden Cooper vetoes: Elections, energy, and regulatory reform,” Carolina Journal, October 5, 2023, https://www.carolinajournal.com/nc-legislature-adds-to-growing-list-of-overridden-cooper-vetoes-elections-energy-and-regulatory-reform/.

- Elijah Gullett, “Exclusionary Zoning in NC,” Carolina Angles, November 26, 2021, https://carolinaangles.com/2021/11/26/exclusionary-zoning-nc/.

- See details on the website for the plan, https://cltfuture2040.com/.

- See details on the website for the ordinance, https://charlotteudo.org/.

- Preston Lennon, “North Carolina zoning law tidy-up has cities and counties working from same playbook,” Port City Daily, April 9, 2021, https://portcitydaily.com/local-news/2021/04/09/north-carolina-zoning-law-tidy-up-has-cities-and-counties-working-from-same-playbook/.

- Subsection 2.9 of that law states “any local government that has adopted zoning regulations but that has not adopted a comprehensive plan (later amended to land use or comprehensive plan) shall adopt such plan no later than July 1, 2022, in order to retain the authority to adopt and apply zoning regulations.” Adam Lovelady, James (Jim) Joyce, Ben Hitchings, and David W. Owens, “Chapter 160D: A New Land Use Law for North Carolina,” School of Government, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, https://www.sog.unc.edu/resources/microsites/planning-and-development-regulation/ch-160d-2019.

- “Introduction,” Charlotte Future 2040 Comprehensive Plan, City of Charlotte, https://www.cltfuture2040plan.com/plan-policy/introduction.

- “Community Values, Vision, and Goals,” Charlotte Future 2040 Comprehensive Plan, City of Charlotte, https://www.cltfuture2040plan.com/content/12-community-values-vision-and-goals-1.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- “Section 9.205 Development Standards: Single-Family, Multifamily, and Institutional Uses,” Charlotte Code of Ordinances, accessed via Municode Library, https://library.municode.com/nc/charlotte/codes/code_of_ordinances/264937?nodeId=PTIICOOR_APXAZO_CH9GEDI_PT2SIFA_S9.205DESTSIMIDI.

- “Zoning Translation,” Charlotte Unified Development Ordinance, https://charlotteudo.org/zoning-translation/.

- “What are the Elements of Place Types?” Charlotte UDO informational one-pager, https://charlotteudo.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/elementsofplacetypes_12-5-2016.pdf.

- Emily Badger and Quoctrung Bui, “Cities Across America Question Single-Family Zoning,” New York Times, June 18, 2019, https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2019/06/18/upshot/cities-across-america-question-single-family-zoning.html.

- Richard Rothstein, The Color of Law: A Forgotten History of How Our Government Segregated America (New York: Liveright Publishing Corporation, 2017).

- Barbara John, “Zoning and Density: Examining Patterns of development in Charlotte, NC,” dissertation, University of North Carolina at Charlotte, 2008, https://www.proquest.com/openview/70f7eabc3fb55ace1ed1a7c646342d05/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=18750.

- Ely Portillo, “Inside the Fight for Charlotte’s Future,” Charlotte Magazine, July 6, 2021, https://www.charlottemagazine.com/inside-the-fight-for-charlottes-future/.

- Avian Tan, “North Carolina’s Controversial Anti-LGBT Bill Explained,” ABC News, March 24, 2016, https://abcnews.go.com/US/north-carolinas-controversial-anti-lgbt-bill-explained/story?id=37898153; Holly Yan, Roland Zenteno, Brian Todd, “Keith Scott killing: No charges against officer,” CNN, November 30, 2016, https://www.cnn.com/2016/11/30/us/keith-lamont-scott-case-brentley-vinson/index.html; Raj Chetty, Nathaniel Hendren, Patrick Kline, Emmanuel Saez, “Where is the Land of Opportunity? The Geography of Intergenerational Mobility in the United States,” Quarterly Journal of Economics 129, no. 4 (June 2014): 1553–623, https://opportunityinsights.org/paper/land-of-opportunity/.

- Gwendolyn Glenn, “Charlotte Voters Overwhelmingly Approve More than $223 Million in Bonds,” WFAE, November 7, 2018, https://www.wfae.org/politics/2018-11-07/charlotte-voters-overwhelmingly-approve-more-than-223-million-in-bonds.

- Danielle Chemtob, “Taiwo Jaiyeoba is chasing something bigger than the 2040 plan,” Axios Charlotte, August 9, 2021, https://charlotte.axios.com/268187/taiwo-jaiyeoba-is-chasing-something-bigger-than-the-2040-plan/.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- “Large southern cities lead nation in population growth,” Table 2, U.S. Census Bureau, May 18, 2023, https://www.census.gov/newsroom/press-releases/2023/subcounty-metro-micro-estimates.html.

- William H. Frey, “New Census data shows a huge spike in movement out of big metro areas during the pandemic,” Brookings Institution, April 14, 2022, https://www.brookings.edu/articles/new-census-data-shows-a-huge-spike-in-movement-out-of-big-metro-areas-during-the-pandemic/.

- “Introduction,” Charlotte Future 2040 Comprehensive Plan, City of Charlotte, https://www.cltfuture2040plan.com/plan-policy/introduction.

- During the 2010–20 period, population increased by 21.6 percent, while housing unit increase lagged behind at 20.2 percent. Michael D. Tanner, “Keeping North Carolina’s Housing Affordable,” Policy Analysis no. 938, Cato Institute, December 7, 2022, https://www.cato.org/policy-analysis/keeping-north-carolinas-housing-affordable#introduction.

- Ibid.

- “The City of Charlotte Zoning Meeting Minutes,” American Legal Publishing, Minutes Book 153, June 21, 2021, 308, https://codelibrary.amlegal.com/codes/CharlotteNC/latest/m/2021/6/21

- Will Freeman, “Why New York Is Experiencing a Migrant Crisis,” Council on Foreign Relations, October 5, 2023.https://www.cfr.org/article/why-new-york-experiencing-migrant-crisis

- Raj Chetty, Nathaniel Hendren, Patrick Kline, Emmanuel Saez, “Where is the Land of Opportunity? The Geography of Intergenerational Mobility in the United States,” Quarterly Journal of Economics 129, no. 4 (June 2014): 1553–623, https://opportunityinsights.org/paper/land-of-opportunity/.

- “Charlotte Opportunity Initiative,” Opportunity Insights, November, 2020, https://opportunityinsights.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/OI-CharlotteReport.pdf.

- Ibid.

- “The City of Charlotte Zoning Meeting,” American Legal Publishing, Minute Book 153, June 21, 2021, 302, https://codelibrary.amlegal.com/codes/CharlotteNC/latest/m/2021/6/21.

- Ibid.

- Braxton Winston, “Single family zoning is a tool of segregation. If you are fighting to maintain single family zoning you are advocating for segregation. Stop being racist, Charlotte.” Twitter, March 2, 2021, https://twitter.com/braxtonwinston/status/1366787481161654278.

- “The City of Charlotte Zoning Meeting Minutes,” City Council of Charlotte, Minutes Book 153, June 21, 2021, 302, https://codelibrary.amlegal.com/codes/CharlotteNC/latest/m/2021/6/21.

- Ibid.

- Steve Harrison, “After Braxton Winston Says Single-Family Zoning Is a ‘Racist Ideology,’ One Colleague Calls Him Reckless,” WFAE, March 4, 2021, https://www.wfae.org/local-news/2021-03-04/after-braxton-winston-says-single-family-zoning-is-a-racist-idealogy-one-colleague-calls-him-reckless.

- Swann v. Charlotte–Mecklenburg Board of Education, 402 US 1 (1971), https://www.oyez.org/cases/1970/281.

- Keith Poston, “When School Desegregation Mattered in Charlotte,” Public School Forum, October 25, 2018, https://www.ncforum.org/2018/when-school-desegregation-mattered-in-charlotte/.

- Ann Doss Helms, “CMS opens the diversity door—and in come hope, fear and national attention,” Charlotte Observer, November 11, 2016, https://www.charlotteobserver.com/news/local/education/article114231553.html.

- Anna Maria Della Costa, “‘We want balance.’ Tensions persist over latest south Charlotte school boundaries draft,” Charlotte Observer, April 24, 2023, https://www.charlotteobserver.com/news/local/education/article274498261.html.

- Richard D. Kahlenberg, “How Zoning Drives Educational Inequality: The Case of Westchester County,” The Century Foundation, July 17, 2023, https://tcf.org/content/report/how-zoning-drives-educational-inequality-the-case-of-westchester-county/.

- “North Carolina Presidential Results,” Politico, January 6, 2021, https://www.politico.com/2020-election/results/north-carolina/.

- Lorena Castillo-Ritz is listed as the chair of the Mecklenburg County Republicans for the 2023–25 cycle. “County Leadership: MeckGOP Executive Board, 2023–2025,” Mecklenburg County Republican Party, https://mecklenburg.nc.gop/county_leadership.

- “The City of Charlotte Zoning Meeting Minutes,” City Council of the City of Charlotte, Minutes Book 153, June 21, 2021, 302, https://codelibrary.amlegal.com/codes/CharlotteNC/latest/m/2021/6/21.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- “Myers Park neighborhood in Charlotte, North Carolina (NC), 28207, 2809, 2811 detailed profile,” City-Datacom, https://www.city-data.com/neighborhood/Myers-Park-Charlotte-NC.html.

- “Income in the United States: 2022,” U.S. Census Bureau, https://www.census.gov/library/publications/2023/demo/p60-279.html#:~:text=Highlights,and%20Table%20A%2D1.

- Interestingly, in 1976, members of the Myers Park Improvement Association successfully lobbied the city to zone large swaths of the neighborhood for single-family homes only. Thomas W. Hanchett, “Myers Park: Charlotte’s Finest Planned Suburb.” Charlotte–Mecklenburg Historic Landmarks Commission, 2010, http://landmarkscommission.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/Myers-Park.pdf.

- Pat. McCrory, “My Walkable Neighborhood, Myers Park,” The Oak Leaf (Summer 2021), published by the Myers Park Homeowners Association, https://www.mpha.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/Oakleaf_Summer_2021_FNL.pdf.

- “Equitable developments, place types and the UDO,” Charlotte Future 2040 Comprehensive Plan, City of Charlotte, June 1, 2021, https://www.cltfuture2040plan.com/docs/comments/Equitable_Development_Place_Types_UDO_060121.pdf.

- Anna Maria Della Costa, “Back to (which) school?: CMS boundaries are being reshaped as the county grows,” Charlotte Observer, July 29, 2022, https://www.charlotteobserver.com/news/local/education/article263671663.html.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- David Boraks, “Groups Want More Neighborhood Input On Charlotte’s 2040 Plan,” WFAE, March 12, 2021, https://www.wfae.org/local-news/2021-03-12/groups-want-more-neighborhood-input-on-charlottes-2040-plan.

- Ryan Pitkin, “Coalition Calls on City to Implement Solutions to Displacement in Charlotte,” Queen City Nerve, July 8, 2022, https://qcnerve.com/displacement-in-charlotte/.

- “The City of Charlotte Zoning Meeting Minutes,” City Council of Charlotte, Minutes Book 153, June 21, 2021, 302, https://codelibrary.amlegal.com/codes/CharlotteNC/latest/m/2021/6/21.

- Michael D. Tanner, “Keeping North Carolina’s Housing Affordable: A Free Market Solution,” Policy Analysis no. 938, Cato Institute, December 7, 2022, https://www.cato.org/policy-analysis/keeping-north-carolinas-housing-affordable#introduction

- Ibid.

- “Goal 2: Neighborhood Diversity and Inclusion,” Charlotte Future 2040 Comprehensive Plan, City of Charlotte, June 1, 2021, https://www.cltfuture2040plan.com/content/goal-2-neighborhood-diversity-and-inclusion

- Ibid.

- “Anti-Displacement Strategy Report,” City of Charlotte, August 2023, https://www.charlottenc.gov/files/sharedassets/city/v/1/city-government/initiatives-and-involvement/documents/anti-displacement/anti-displacement-strategy-final_07-11-2023.pdf.

- “Proposed 2040 Comprehensive Land Use Plan,” Real Estate and Building Industry Coalition (REBIC), March 3, 2021, https://drive.google.com/file/d/1luIQ3IePgO27Z-SLBufOxtyIkgfPyz5n/view.

- David Boraks, “Real Estate Industry Campaign Targets Charlotte 2040,” WFAE, https://www.wfae.org/local-news/2021-05-11/real-estate-industry-campaign-targets-charlottes-2040-plan.

- Chris Miller, “Politics Monday: Decision Time For Charlotte 2040,” WFAE, https://www.wfae.org/local-news/2021-05-11/real-estate-industry-campaign-targets-charlottes-2040-plan.

- Nathaniel Puente and Julia Kauffman, “Charlotte City Council passes Unified Development Ordinance with 6-4 vote,” WCNC, August 21, 2022, https://www.wcnc.com/article/news/local/charlotte-city-council-set-to-vote-on-udo-proposal-on-monday-zoning-laws-housing-single-family-duplex-north-carolina/275-a8860b1a-cff5-45a7-8cff-7db612559557.

- “BPS—Permits by Metropolitan Area,” U.S. Census Bureau, 2023, https://www.census.gov/construction/bps/msamonthly.html.

- Austin Walker, “Charlotte City Council sworn in Monday,” WCNC, December 4, 2023, https://www.wcnc.com/article/news/local/new-charlotte-city-council-sworn-in-monday/275-b76a3da8-cd78-4bb1-9e01-6a03916cc463.

- “Anti-Displacement Strategy Report,” City of Charlotte, August 2023, https://www.charlottenc.gov/files/sharedassets/city/v/1/city-government/initiatives-and-involvement/documents/anti-displacement/anti-displacement-strategy-final_07-11-2023.pdf.

- “The City of Charlotte Zoning Meeting Minutes,” City Council of Charlotte, Minutes Book 153, June 21, 2021, 307, https://codelibrary.amlegal.com/codes/CharlotteNC/latest/m/2021/6/21.