Zoning—the rules about what can and cannot be built, and where—shapes everyone’s lives in powerful ways, but often operates invisibly to the average person. Residential zoning is particularly impactful, because it determines what types of housing exist in which neighborhoods, whether apartments or duplexes are allowed, where homes must have multiple parking spaces or large yards that drive up cost, and, ultimately, who can afford to live in any neighborhood where housing is built. It affects who gets easy access to stores, restaurants, libraries, parks, and medical facilities. And because over 70 percent of American school children attend their assigned public school, usually based on their address, housing policy is, in effect, education policy.1 What can be built in a community determines who gets to live there and who goes to school there. Indeed, the parents of one in five public school students report that they chose where to live because of access to schools.2

This report looks at how Oregon became the first state in the nation to legalize duplexes, triplexes, and fourplexes—commonly known as middle housing—statewide. The report is part of a series by The Century Foundation on the links in New York State between exclusionary zoning practices (which make neighborhoods unaffordable to lower income and working class people) and educational opportunity (which is embedded in the access to schools that is determined by a family‘s address). The first reports in the series examined the inequities created by exclusionary zoning in four different regions across New York State (in Queens, Long Island, Westchester, and Buffalo). This report is part of a collection highlighting positive examples of zoning reform from across the country (with other reports focused on California, Minneapolis, Minnesota, and Charlotte, North Carolina) to offer hope and lessons for reform in New York.

This report proceeds in three parts: first, a look at the reforms and the strategy that made them possible; second, early evidence of the legislation’s impact; and third, lessons for reformers in New York that can be drawn from Oregon’s success.

Oregon’s Pioneering Missing Middle Legislation

In 2019, Oregon passed statewide reform legalizing duplexes, triplexes, and fourplexes—so-called middle housing—and limiting zoning that allows single-family detached homes only. It was the first state in the nation to essentially ban single-family zoning statewide.

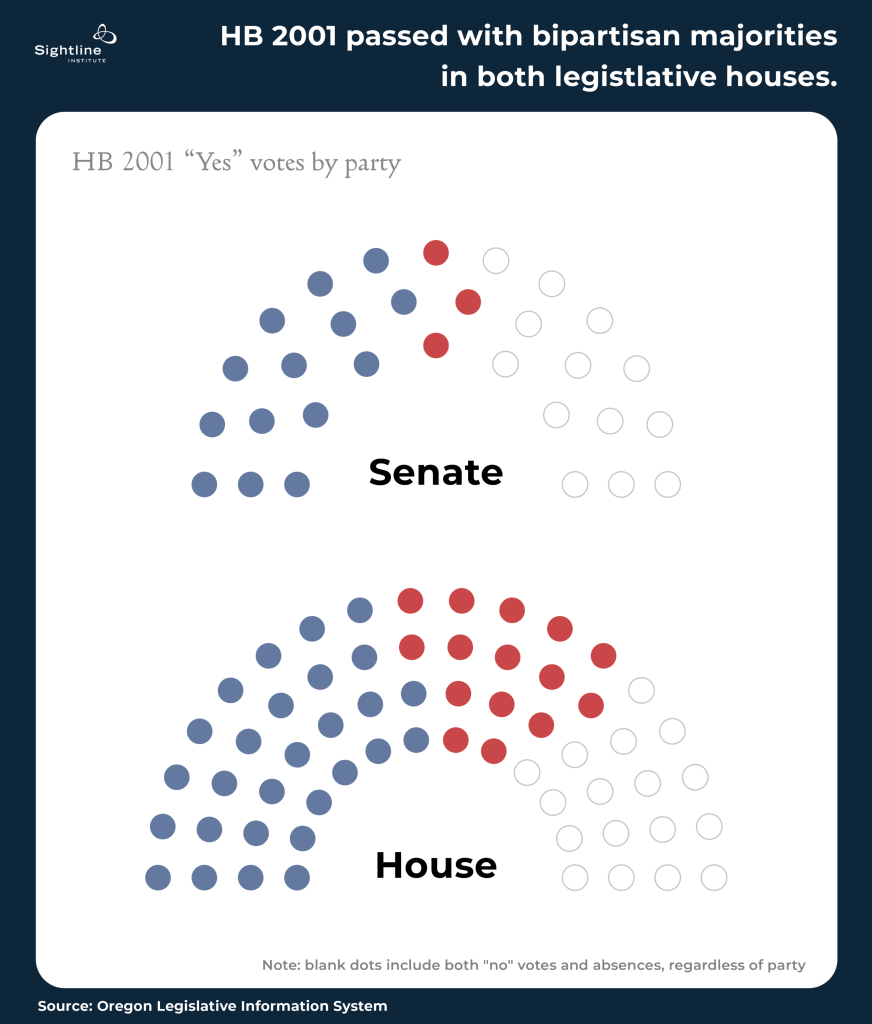

House Bill 2001 (HB 2001, also often referred to as the housing choices bill or the missing middle housing bill) passed the state legislature on June 30, 2019, with bipartisan majorities in both the state senate and house, and was signed into law that August. The law requires any city in Oregon with a population of 10,000 people or more to allow the construction of duplexes in areas that formerly allowed single-family detached houses only. In cities with populations of 25,000 or more, as well as in twenty-four municipalities in the Portland metro area, the reforms go farther: areas that were formerly zoned for single-family detached houses must now allow up to fourplexes.3 Altogether, the municipalities affected by HB 2001 comprise 68 percent of the state’s population.4

The law also struck down local provisions that cause “unreasonable cost and delay” in the construction of middle housing. The state rulemaking process translated these provisions into limitations on the number of parking spaces that new homes must include—requirements that can pose logistical challenges and drive up costs. This turned the legislation into another first: the “the largest state-level parking reform law in U.S. history,” according to Sightline Institute, a think tank focused on sustainability in the Northwest.5

The path to this legislation, which was groundbreaking on multiple fronts, was forged in response to a severe housing crisis, and it succeeded thanks to careful strategy.

A Statewide Housing Crisis

By the mid-2010s, Oregon faced a severe housing crisis. The population was increasing, but housing was not keeping pace. Prices were skyrocketing, there were not enough homes, and homelessness was on the rise. From 2010 to 2020, Oregon’s population grew by 400,000 people, the number of homes only increased by 150,000, and average housing prices doubled.6

As of 2016, fully one-third of Oregon’s households—half of all renters, and a quarter of homeowners—were “cost-burdened” by housing, meaning that they were spending more than 30 percent of their income on housing.7 In 2015, Oregon’s rental vacancy rate was the lowest in the nation at just 3.6 percent,8 and homelessness was surging. As of 2019, the city of Eugene had the highest homelessness rate per capital of any major U.S. city (432 per 100,000), with the rate having increased 12 percent in just five years.9

Portland, Oregon’s largest city, was facing particularly acute challenges. At the time, 77 percent of the land in Portland was zoned to allow single-family detached houses only.10 The number of unhoused people rose so high in Portland that the city declared a housing emergency in 2015 (which has since been renewed multiple times, currently running through 2025).11 Rents in central Portland neighborhoods increased 14 percent in that year alone, and officials calculated that Portland would need 24,000 additional affordable housing units to meet demand.12 It was not just low-income residents who struggled to find affordable housing. A 2017 analysis found that a first-year teacher in Portland would have to spend 49 percent of their salary to afford the median rent of a one-bedroom apartment and would have to save for 17.1 years to afford a down payment to buy a home.13 As one school librarian told a reporter, “I would really love to buy a home and I just don’t think it’s going to be possible.”14

Other regions across the state were struggling with housing as well. Central Oregon used to be a rural area dominated by the timber industry that was known for being affordable even to low-income people. However, new economic development in the region—including manufacturing, biotech, health care, brewing, and distilling—brought many new residents to the area, while housing lagged behind. By 2018, Central Oregon had a vacancy rate of just 0 to 1 percent in both sales and rentals; in the central Oregon city of Bend, prospective homebuyers needed to be making roughly $81,000 per year—well above the city’s median income of $59,400—to afford an average-priced home.15

This housing crisis was also a racial justice issue, disproportionately impacting people of color. Oregon’s population is predominantly White (73 percent), with the next largest groups being Latine (14 percent), Asian (5 percent), two or more races (4 percent), Black (2 percent), American Indian or Alaskan Native (2 percent), and Native Hawaiian and other Pacific Isander (0.5 percent).16 Oregonians of color are significantly more likely than White Oregonians to be renting their home, and have lower incomes on average, resulting in a greater likelihood of being cost-burdened. While just 35 percent of White households are renting, twice that share—70 percent—of Black households are renting, along with 58 percent of Latine households and similar shares of Native households, as well as 42 percent of Asian households.17 A 2019 report from the Portland Housing Bureau found that there was not a single neighborhood in Portland (where 6 percent of the population is Black) where the average Black resident could afford a two-bedroom rental.18

Oregon was facing a population increase, a housing shortage, and a crisis of affordability all at once. “If only national media would stop writing about how great Oregon is. If only Californians would quit moving here….” an editorial in The Oregonian joked. “Then there wouldn’t be a housing crisis, right?”19 Short of scaring people away from the state, the only real solutions required to encourage the construction of more affordable homes.

The Recipe for Successful Reform

This crisis lit a fire for reform. When Democratic representative Tina Kotek became speaker of the Oregon House of Representatives in 2013, she began making housing a priority. “Our crisis is so severe in this state, you have to do everything,” she told a reporter.20

One factor that Oregon had in its favor was a strong history of state involvement in zoning, going back to legislation in 1973, initiated by Republican leaders but later associated with Democrats, that created an “urban growth boundary” in an effort to control urban sprawl.21 As a result, there was already precedent for the state taking a role in the sorts of zoning decisions that are often fully delegated to localities.

But getting to reform still was not easy. Although Oregon has consistently had Democratic control of the state house, senate, and governorship since 2013,22 the state was fiercely politically divided. In early 2016, Oregon was the site of a six-week occupation of armed far-right militia members in federal buildings, capturing national attention,23 and in 2019, just days before the passage of the housing law, Republican senators staged “walkouts” to prevent passage of tax and climate legislation.24

No state had passed legislation like this before, so there was no playbook to follow. Kotek first introduced a bill to legalize middle housing—in this case duplexes—in 2017. The legislation, HB 2007, failed, but it did so “in ways that paved the way for HB 2001,” helping to organize supporters, identify opponents, and locate potential dealbreakers, according to analysis by Sightline Institute’s Michael Andersen.25 That same year, the state passed a law legalizing backyard cottages, basement apartments, “in-law flats,” and other accessory dwelling units (ADUs) across the state, giving hope that statewide legislation to address housing production was possible. In 2019, Kotek, who later went on to become governor of Oregon in 2023, tried again and succeeded with the introduction of HB 2001, which went beyond the previous duplex proposal to include legalization of triplexes and fourplexes. The legislation passed thanks in large part to intentional bipartisan coalition building and messaging focused on the benefits of adding middle housing.

Building a Broad, Bipartisan Coalition

From its introduction in January 2019, the bill faced opposition. The Oregon League of Cities opposed the bill because it preempted local zoning decisions. The spokesperson for the Oregon Republican Party suggested that the state should expand the urban growth boundary instead of stepping into local zoning matters.26 And Democratic Senator Kathleen Taylor, who represented a low-density area in Portland and who was largely responsible for killing HB 2007 in 2017, also opposed HB 2001, along with a number of suburban Democratic lawmakers.27

But a broad group of advocates and stakeholders stepped up in support of the missing middle housing bill. Pro-housing advocates in Portland had already been pushing for changes in city zoning for several years, and so they had established strong networks and alliances that they could quickly put to use in favor of the proposed state-level reforms. The group 1000 Friends of Oregon created the Portland for Everyone campaign to mobilize volunteers and get a wide range organizations to support the bill, including environmental groups, racial justice groups, tenant advocates, affordable housing developers such as Habitat for Humanity, AARP Oregon, as well as the Oregon Association of Realtors and Oregon Home Builders Association.28

Within the legislature, Kotek assembled an urban–rural coalition of Democrats and Republicans. Supporters included urban Democrats, members from both parties in the tourist areas of the state (the coast and the high desert), as well as some property rights supporters from rural areas.29 Republican Jack Zika, a realtor from Bend, in the high desert region, cosponsored the bill. “We all have an affordable housing crisis in our areas,” he explained “This is not a silver bullet, but will address some of the things that all our constituents need.”30 The bill ultimately passed with bipartisan majorities in both chambers, but opposition was bipartisan as well: it would not have passed without Republican support (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Oregon’s Housing Legislation was Bipartisan

Support from Portland Public Schools

One of the supporters of the legislation was Portland Public Schools. Although education and housing are intertwined issues (as this series of reports has demonstrated), the two advocacy communities are often siloed. In the instances when schools are invoked in conversations about housing, it is often by opponents of reform citing concerns about overcrowding in schools.31 Thus it is noteworthy that Portland Public Schools submitted testimony in support of HB 2001 during the debate leading up to its passage.

“In our district, so much of the focus was and continues to be racial equity and social justice. And this is a racial equity and social justice issue,” explained Courtney Westling, former director of government relations for Portland Public Schools, about the decision by the school district to weigh in. “It just seemed in line with our values to talk about this issue.”32

In her testimony on behalf of Portland Public Schools, Westling highlighted several ways that building missing middle housing could benefit the educational futures of Portland’s students. Building more housing would help address homelessness: “too many of our students—over 1,000 last year—are struggling without a stable housing situation.” Zoning changes would also increase opportunities for more affordable housing within walking distance of schools. “We need more housing options within walking distance to our schools. Today, the neighborhoods surrounding most of the schools in our district are zoned almost exclusively for single-family homes. This exclusive zoning impacts which neighborhood school a family can afford to attend.” And it had the potential to fight against segregation: “Exclusionary zoning leads to economic segregation of schools—and—as a result, racial segregation. Why is the student population of one PPS school 14 percent white while another three miles away is 79 percent white? One reason is exclusionary single-family zoning.”33 Westling, who is White, has seen the benefits of more diverse schools for her own family; her sons attend a Portland public school with a majority of students of color—or a “global-majority school,” as Westling calls it—and she thinks it has been a great experience for them: “If we push our students into schools where they’re only surrounded by people that look like them, we’re doing them a disservice. When we create learning environments that reflect the diversity of our communities, we set all of our students up for academic success and to better navigate the world beyond graduation.”34

Positive Messaging

One of the other ingredients that helped build and sustain support for HB 2001 was a winning messaging strategy that had been developed by advocates who worked on zoning reform in Portland in the years leading up to the introduction of statewide legislation. The terms “missing middle” and “middle housing,” originally coined in 2010, were themselves conscious messaging designed to focus on expanding choice and increasing the number of homes without dramatic changes to neighborhoods.35 Sightline Institute and Portland for Everyone drew lessons from research, focus groups, and experience canvassing to crystalize the most effective ways of talking about housing reform and shared these insights with other advocates in a messaging memo. The approach was based on positive framing that emphasized the benefits that adding middle housing could bring to a neighborhood rather than focusing on “ending single-family zoning.”36 In fact, they recommended avoiding the term “zoning” altogether when possible and talking in simple, concrete terms about duplexes, triplexes, and small apartment buildings rather than “multi-unit” construction.37 And they encouraged advocates to show visuals of what different middle housing types looked like to head off the opposition stirring up fears of high-rise buildings (see figure 2).

Figure 2: Examples of Middle Housing

Rather than “banning single family zoning,” the messaging strategy focused on “legalizing”—or actually “re-legalizing”—different home types and reversing the restrictive zoning laws that were put in place in the mid-1900s.38 Kotek effectively adopted this framing when talking about the law and her own experience. “This is how we used to do things before we became wedded to the idea of a single-family home as a standalone home with a big yard,” she said during a panel call with Biden administration officials sharing lessons from Oregon’s experience. “When I moved back to Portland after graduate school, I lived in a very established neighborhood in a fourplex apartment complex nestled in an old neighborhood with all kinds of different types of housing, and it provided a lot of opportunity for me. That’s what we want to get back to.”39

Paving the Way for Local Changes

Passing the legislation was just the first step in the process of Oregon’s missing middle housing reforms. The bill included $3.5 million in funding to the Department of Land Conservation and Development (DLCD) for technical assistance to local governments,40 and DLCD set minimum compliance standards and wrote model code to guide the local implementation of HB 2001.41 Oregon’s missing middle legislation set a deadline of June 20, 2022 for all localities to adopt new zoning codes in compliance with the law; otherwise, the state model code would apply.42 It would have been possible for all municipalities to end up with the minimum requirements laid forth in the law—which would on their own represent a significant shift—but that did not happen. By the end of 2022, all affected municipalities had complied,43 and, according to Sightline’s Michael Andersen, almost all of the localities voluntarily went at least a little bit above and beyond the state standards.44 For example, the city of Eugene passed zoning changes in May 202245 that allowed for smaller lot sizes and taller buildings than in the model code.46 Bend eliminated parking minimums as part of their zoning reforms.47 And Newport, a coastal city of roughly 10,000 people, allowed townhouses and cottage clusters instead of just duplexes.48

The most sweeping local legislation came out of Portland, where discussions about zoning changes had been underway since 2015, four years before the introduction of HB 2001. But while Portland had a head start on its zoning reforms, the state law still played an important role in helpfully setting a deadline and base requirements to meet. In August 2020, a year after the state legislation, Portland passed its Residential Infill Project. The law made duplexes, triplexes, and fourplexes legal on almost all formerly single-detached zoned areas. Furthermore, it allowed for buildings with five or six homes on any lot if at least half of the units were regulated affordable housing for low-income Portlanders.49 It also provided density bonuses, meaning that duplexes, triplexes, and fourplexes can be built bigger than a single-detached home on the same size lot. And it created more opportunities for duplexes and single-detached homes to add basement apartments, granny flats, or other accessory dwelling units.50

Oregon’s missing middle law “forced cities to have a conversation about their low-density zones that they had been easily avoiding and were incentivized to avoid forever,” Andersen explained. “Just the presence of the conversation was quite a big thing.”51

The Impact of Zoning Reform on Housing Production and Prices

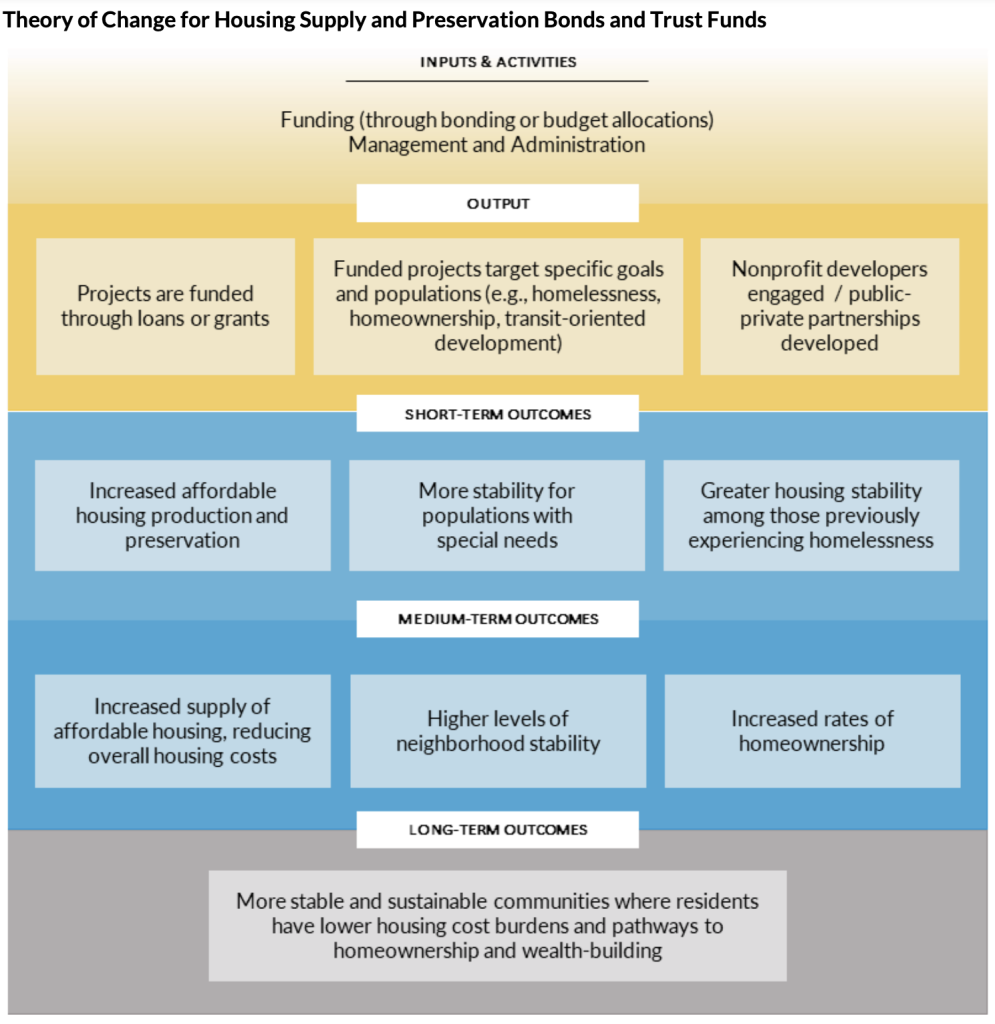

The impact of Oregon’s missing middle legislation, like most housing reforms, is slow. Building and selling or renting homes takes time. Only a small percentage of lots turns over each year, and many of those may not be good candidates for new construction or redevelopment. Builders and real estate agents also need to gain experience with the new zoning laws and the options that they open up in order to start taking advantage of them.52 Kotek has emphasized this long time horizon when talking about the law: “The re-legalization of middle housing that occurred in Oregon is very much a long-term solution to providing more supply in our state…. It’s going to take about 20 years to fully implement this, but we are going to see gradual change year after year and provide more housing options in our communities because of this.”53 A figure created by the Urban Institute lays out the multiple levels of action in the theory of change for Oregon’s state zoning reforms (see Figure 3).

Figure 3: Oregon’s Statewide Housing Law Requires Multiple Levels of Change to Achieve Impact

For now, the housing crisis in Oregon continues. It is still one of the states with the lowest supply of affordable rentals.54 It saw the second largest increase (22 percent) in the number of people experiencing homelessness between 2020 and 2022.55 And it ranks fourth in the nation (behind California, Colorado, and Utah) in underproducing housing.56

But early data following the 2019 missing middle legislation show promising trends in the right direction. In fall 2021, Bend became one of the first cities to comply with the new state law,57 and in January 2022, the city reported 650 housing units in construction, compared to just sixty-two homes completed in the previous six months.58

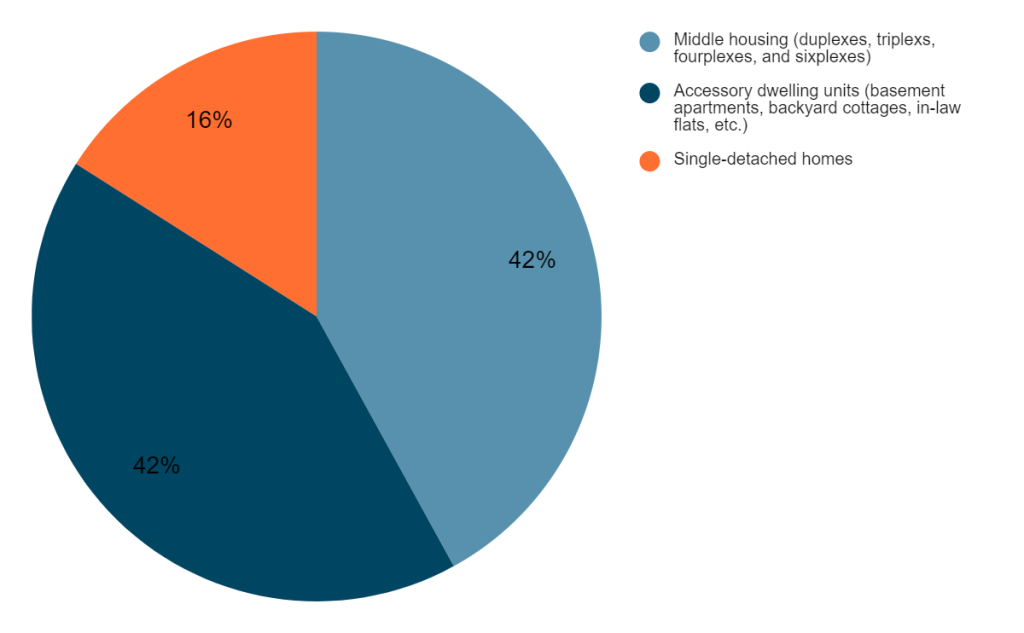

Portland’s Residential Infill Project, which passed in August 2020 and went into effect in August 2021,59 is the best example so far to show early results of the zoning changes. The city estimates that these zoning changes will help to create an additional 5,000 housing units over twenty years across neighborhoods that formerly allowed single-detached homes only.60 In summer 2023, the city of Portland published a report produced by outside analysts examining the first twelve months of data after the zoning changes.61 During that time, roughly 650 new homes were permitted in areas rezoned by the Residential Infill Project, and of those, just 16 percent were single-detached homes, while 42 percent were middle-housing options (duplexes, triplexes, fourplexes, or sixplexes), and another 42 percent were accessory dwelling units (basement apartments, in-law flats, backyard cottages, and so on).62 (See Figure 4.)

Figure 4: New Homes Built in Portland Neighborhoods with Reformed Zoning, by Type

Habitat for Humanity is one affordable housing developer in Portland that has taken advantage of the new growth opportunities. They are currently building fifteen affordable homes through a mix of duplexes and triplexes on a plot of land in Northeast Portland that formerly had a single-family detached home, as well as building a cluster of seventeen cottages on a plot of land in Southwest Portland—both projects that would not have been allowed before the reforms.63

The city’s report also found that about half of the single-family detached homes built and sold in the period just before the law went into effect are no longer allowed to be built because of the size caps (an aspect of the Residential Infill Project that went beyond the state requirements), and that these homes on average cost $117,000 more than the homes that are in compliance with current zoning. That means that the new zoning should help to slow down skyrocketing costs for the most expensive housing in the city.64

Lessons for New York State

There are plenty of differences between Oregon and New York that affect the trajectories of housing reform. For one, Oregon is a much less populous state, with a population roughly half the size of New York. It is also more racially homogeneous, with a population that is over 70 percent White, compared to New York, which is 54 percent White, 20 percent Latine, 18 percent Black, 10 percent Asian, 1 percent American Indian and Alaska Native, 0.1 percent Native Hawaiian and other Pacific Islander, and 3 percent two or more races. When it comes to the state role in housing, the history of zoning and state intervention in Oregon also looks very different from that in New York. Oregon is unusual among states for having a track record going back several decades of state involvement in zoning decisions. By contrast, New York has had little state involvement in zoning, leaving decisions almost fully up to localities. And the history of zoning—and the ways it has been used to exclude—is long in New York. The very first comprehensive zoning law in the country came out of New York City in 1916, motivated by business owners on Fifth Avenue who wanted to keep out Jewish tenements and factories.65 In the mid 1900s, Long Island became home to Levittown—known as America’s “first suburb”—which was constructed from 1947 to 1951 to house returning White World War II veterans, with a racially restrictive covenant preventing any “non-Caucasian” residents from buying or occupying the homes.66 New York was the birthplace for many of the earliest and most pervasive exclusionary zoning tactics based on race or ethnicity and later income as well.67

Despite these differences, there are still a number of lessons that Oregon’s successful statewide zoning reform can offer to housing advocates in New York. Three key learnings address bipartisan support, bringing progressives on board, and learning from failure.

Bipartisan Support Is Essential

Oregon’s missing middle legislation was bipartisan, from the shaping of the bill to the final vote. Supporters and opponents came from both parties, and although the legislation was led by Democrats, it would not have passed without Republican support.

An analysis earlier this year from the market-oriented think tank Mercatus finds that this may not be a fluke: successful state-level housing reforms usually pass with overwhelming bipartisan majorities, whereas strong minority party opposition can kill them, even in the presence of a lopsided majority. The authors of the Mercatus report examined successful and failed state legislative efforts, and found that members of the majority party in swing districts may only be comfortable voting for housing reforms when they are bipartisan, because that helps give them some political cover.68

Bipartisan legislation may seem challenging in New York, but that was also the case in Oregon. Sightline Institute’s Michael Andersen emphasized that bipartisanship is sometimes possible for zoning reform even when it is elusive for other issues. “You can do it with housing,” he urged. “There are enough cross incentives that it’s possible—if you can put aside your hatred.”69

Ensure a Unified Front on the Left

Alongside the bipartisan nature of the missing middle legislation from start to finish was another important aspect of the coalition: progressives were seemingly unified in their support. Although some opposition to the bill came from Democrats, mostly from suburban areas, it did not come from social activist groups.70 This distinguished the debate in Oregon from what happened in California’s first failed reform in 2018, when tenant advocacy groups opposed zoning reforms because they didn’t include provisions for publicly subsidized affordable housing.71 The plan for statewide housing reform in New York that was proposed by Governor Kathy Hochul in early 2023 likewise received criticism from the left because it did not do enough to ensure affordability for renters.72

The unified front on the left in Oregon mattered, according to political strategists who worked on the legislation, because if progressive groups had come out against the bill because it didn’t do enough for affordability, for example, it would also have given cover for Democrats with more Not-In-My-Backyard concerns to oppose the bill on ostensibly progressive grounds.73

Ensuring this unified front on the left was not easy, and it was the result of engagement on this issue over a long period of time, going back to the organizing that was taking place starting in 2015 to support the Portland Residential Infill Project. Andrés Oswill is a housing leader and advocate in Portland who was involved with work on the city’s zoning changes over the years through playing a number of different roles on the Portland Housing Bureau, in the office of a Portland City Commissioner, as a member of the Portland Planning and Sustainability Commision, and for a nonprofit focused on supporting progressive BIPOC policy leaders in the state. “The pro-development movement, importantly, has been very intentional to avoid the mistakes of other places, notably San Francisco, which is pitting pro-housing against pro-affordability and pro-renter groups,” Oswill explained. “There was so much intentionality in how we set up the conversation. Who do we invite to the table? Let’s bring folks along and into it and work through their legitimate concerns and incorporate that into our advocacy to build this coalition around the issue…. We were coming together as a united front.”74

Fail Forward

Before the successful passage of HB 2001 in 2019, Kotek unsuccessfully introduced legislation to legalize duplexes statewide in 2017. But this failure proved helpful. From this “trial run,” as Andersen calls it, came important lessons for building the coalition and revising the policy proposal.75 California also learned from unsuccessful attempts at statewide reform before succeeding in 2021.76

In comparing different statewide zoning reform attempts, analysts at Mercatus noted that “New York and Colorado did not match the modest success achieved in California, however, because governors Hochul and Polis had not prepared strong contingency plans in case their proposals failed.”77 As New York policy leaders and advocates approach future statewide reform efforts, they should build on the lessons of Hochul’s failed New York Housing Compact.

Like Oregon, New York is facing a housing crisis that should inspire action. The state has created 1.2 million jobs in the past decade but only 400,000 new homes. Since 2015, average rents outside New York City have risen 40 to 60 percent, and within New York City, they have risen 30 percent. Home values have also skyrocketed during that time: a 50 percent increase in New York City and 50 to 80 percent increase elsewhere in the state.78

Until recently, there were no roadmaps or examples of state-level housing reform to turn to, but Oregon’s pioneering missing middle legislation offers some lessons for New York and hope that statewide reform is possible.

Notes

- “Fast Facts: Public school choice programs,” National Center for Education Statistics, 2023, https://nces.ed.gov/fastfacts/display.asp?id=6.

- “Fast Facts: Public school choice programs,” National Center for Education Statistics, 2023, https://nces.ed.gov/fastfacts/display.asp?id=6.

- Michael Andersen, “Eight Ingredients for a State-Level Zoning Reform,” Sightline Institute, August 13, 2021, https://www.sightline.org/2021/08/13/eight-ingredients-for-a-state-level-zoning-reform/.

- Michael Andersen, “Eight Ingredients for a State-Level Zoning Reform,” Sightline Institute, August 13, 2021, https://www.sightline.org/2021/08/13/eight-ingredients-for-a-state-level-zoning-reform/.

- Michael Andersen, “Eight Ingredients for a State-Level Zoning Reform,” Sightline Institute, August 13, 2021, https://www.sightline.org/2021/08/13/eight-ingredients-for-a-state-level-zoning-reform/.

- “Eliminating Single-Family Zoning and Parking Minimums in Oregon,” Bipartisan Policy Center, September 26, 2023, https://bipartisanpolicy.org/blog/eliminating-single-family-zoning-and-parking-minimums-in-oregon/.

- “One in Three Oregon Families Struggle to Afford Housing,” Oregon Center for Public Policy, March 15, 2018, https://www.ocpp.org/2018/03/15/20180315-cost-burdened-housing/.

- Luke Hammill. “Can’t find an apartment? Oregon’s vacancy rate was nation’s lowest, data show,” The Oregonian, December 10, 2015, https://www.oregonlive.com/front-porch/2015/12/cant_find_an_apartment_oregons.html.

- Anna Sundholm, “Eugene has the nation’s highest homelessness rate,” The Torch, Lane Community College Student Newspaper, November 13, 2019, https://lcctorch.com/eugene-has-the-nations-highest-homelessness-rate/.

- Emily Badger and Quoctrung Bui, “Cities Start to Question an American Ideal: A House With a Yard on Every Lot,” The New York Times, June 18, 2019, https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2019/06/18/upshot/cities-across-america-question-single-family-zoning.html.

- Andrew Theen, “Portland approves housing emergency plan, what comes next is unclear,” The Oregonian, October 8, 2015, https://www.oregonlive.com/portland/2015/10/portland_approves_housing_emer.html. Rebecca Ellis, “Portland extends housing state of emergency for three years,” Oregon Public Broadcasting, March 30, 2022, https://www.opb.org/article/2022/03/30/portland-extends-housing-state-of-emergency-for-three-years/.

- Amelia Templeton and Ryan Haas, “A Look Back At Oregon’s Housing Crisis,” Oregon Public Broadcasting, November 30, 2015, https://www.opb.org/news/series/greetings-northwest/a-look-back-at-oregons-housing-crisis/.

- National Council on Teacher Quality, “Trendline Housing Data,” NCTQ Open Data, October 2017, https://www.nctq.org/dmsView/Trendline_housing_data; Neal Morton, “How long must Seattle teachers save for house down payment? New study says 15–19 years,” The Seattle Times, October 18, 2017, https://www.seattletimes.com/education-lab/how-long-must-seattle-teachers-save-for-house-down-payment-new-study-says-15-19-years/.

- Emily Harris and Emma Hurt, “High housing costs challenge Portland teachers,” Axios Portland, August 22, 2023, https://www.axios.com/local/portland/2023/08/22/high-housing-costs-challenge-teachers-portland.

- Amanda Waldroupe, “As Central Oregon’s population spikes, so does its housing crisis,” Street Roots, April 13, 2018, https://www.streetroots.org/news/2018/04/13/central-oregons-population-spikes-so-does-its-housing-crisis.

- U.S. Census Bureau. “Oregon QuickFacts,” Population Estimates, July 1, 2022, https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/OR/PST045222.

- “One in Three Oregon Families Struggle to Afford Housing,” Oregon Center for Public Policy, March 15, 2018, https://www.ocpp.org/2018/03/15/20180315-cost-burdened-housing/.

- Portland Housing Bureau, “The State of Housing in Portland,” City of Portland Annual Report, 2019, https://www.portland.gov/phb/documents/2019-state-housing-report/download; Latisha Jensen, “An Average Black Family Cannot Afford a Two-Bedroom Rental in Any of Portland’s Neighborhoods,” Willamette Week, July 8, 2020, https://www.wweek.com/news/2020/07/08/an-average-black-family-cannot-afford-a-two-bedroom-rental-in-any-of-portlands-neighborhoods/.

- The Oregonian Editorial Board, “Editorial: A potential game changer for housing,” The Oregonian, December 23, 2018, https://www.oregonlive.com/opinion/2018/12/editorial-a-potential-game-changer-for-housing.html.

- Anthony Sanfilippo, “Oregon Takes Steps to Improve Housing Availability,” National Association of Realtors, September 2019, https://homeownershipmatters.realtor/oregon/oregon-takes-steps-to-improve-housing-availability/; Liam Dillon, “How can states fight soaring housing prices? Oregon is capping rent increases and cutting single-family zoning,” The Philadelphia Inquirer, August 3, 2019, https://www.inquirer.com/real-estate/housing/affordable-housing-rising-rent-single-family-zoning-oregon-california-20190803.html.

- Michael Andersen, “Eight Ingredients for a State-Level Zoning Reform,” Sightline Institute, August 13, 2021, https://www.sightline.org/2021/08/13/eight-ingredients-for-a-state-level-zoning-reform/.

- “Party control of Oregon state government,” Ballotpedia, https://ballotpedia.org/Party_control_of_Oregon_state_government.

- Courtney Sherwood and Kirk Johnson, “Bundy Brothers Acquitted in Takeover of Oregon Wildlife Refuge,” The New York Times, October 27, 2016, https://www.nytimes.com/2016/10/28/us/bundy-brothers-acquitted-in-takeover-of-oregon-wildlife-refuge.html.

- “2019 Oregon Senate Republican walkouts,” Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/2019_Oregon_Senate_Republican_walkouts#:~:text=From%20June%2020%2C%202019%2C%20all,death%20of%20Republican%20Jackie%20Winters.

- Michael Andersen, “Eight Ingredients for a State-Level Zoning Reform,” Sightline Institute, August 13, 2021, https://www.sightline.org/2021/08/13/eight-ingredients-for-a-state-level-zoning-reform/

- Laura Bliss, “A New Oregon Law Would Make It the First State to Ban Single-Family Zoning,” Pacific Standard, July 3, 2019, https://psmag.com/economics/single-family-housing-is-ore-gone.

- Michael Andersen, “Eight Ingredients for a State-Level Zoning Reform,” Sightline Institute, August 13, 2021,https://www.sightline.org/2021/08/13/eight-ingredients-for-a-state-level-zoning-reform/

- “Portland for Everyone,” 1000 Friends of Oregon, https://friends.org/about-us/programs/P4E; Michael Andersen, “Eight Ingredients for a State-Level Zoning Reform,” Sightline Institute, August 13, 2021, https://www.sightline.org/2021/08/13/eight-ingredients-for-a-state-level-zoning-reform/; “HB 2001 Signed into Law,” 1000 Friends of Oregon, August 8, 2019, https://friends.org/news/2019/8/hb-2001-signed-law. Richard D. Kahlenberg, Excluded: How Snob Zoning, NIMBYism, and Class Bias Build the Walls We Don’t See (New York: PublicAffairs, 2023), 224.

- Michael Andersen, interview with author, August 10, 2023.

- Laura Bliss, “A New Oregon Law Would Make It the First State to Ban Single-Family Zoning,” Pacific Standard, July 3, 2019, https://psmag.com/economics/single-family-housing-is-ore-gone.

- See, e.g., this consulting firm that advertises its ability to help residents fight upzoning by citing school overcrowding: “Preventing Residential Growth from Causing School Overcrowding and Excessive Class Size,” Community and Environmental Defense Services, https://ceds.org/school-overcrowding/ (accessed November 18, 2023).

- Courtney Westling, interview with author, August 8, 2023.

- “Testimony supporting HB 2001,” Oregon State Legislature, Joint Committee on Ways and Means, Subcommittee on Transportation and Economic Development, June 11, 2019, https://olis.oregonlegislature.gov/liz/2019R1/Downloads/CommitteeMeetingDocument/203938.

- Courtney Westling, interview with author, August 8, 2023.

- “About,” Missing Middle Housing, last modified 2023, https://missingmiddlehousing.com/about.

- Anna Fahey and Michael Andersen, “Talking Triplexes: Missing middle message guide,” Sightline Institute, 2019, https://www.sightline.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/Sightline-Missing-Middle-Message-Memo.pdf.

- Michael Andersen, “Eight Ingredients for a State-Level Zoning Reform,” Sightline Institute, August 13, 2021, https://www.sightline.org/2021/08/13/eight-ingredients-for-a-state-level-zoning-reform/.

- Michael Andersen, “Maps: Portland’s 1924 Rezone Legacy Is ‘A Century of Exclusion,’” Sightline Institute, May 25, 2018, https://www.sightline.org/2018/05/25/a-century-of-exclusion-portlands-1924-rezone-is-still-coded-on-its-streets/.

- Julia Shumway, “White House: Oregon single-family zoning law could be model for nation,” Oregon Capital Chronicle, October 29, 2021, https://oregoncapitalchronicle.com/2021/10/29/white-house-oregon-single-family-zoning-law-could-be-model-for-nation/.

- “Key Elements of House Bill 2001,” Department of Land Conservation and Development, November 6, 2019, https://www.oregon.gov/lcd/UP/Documents/HB2001TechnicalOverview.pdf.

- “Housing Choice,” Housing Program, Department of Land Conservation and Development, https://www.oregon.gov/lcd/Housing/Pages/Choice.aspx (accessed November 17, 2023).

- Megan Banta, “Eugene officials unanimously pass middle housing rules after months of community feedback,” The Register–Guard, May 25, 2022, https://www.registerguard.com/story/news/2022/05/25/eugene-oregon-middle-housing-passed-tweaked-planning-commission-recommendation-hb-2001-duplex/65357451007/.

- Mark Treskon, Jorge González-Hermoso, Noah McDaniel, and Dennis Su, “Local and state policies to improve access to affordable housing,” The Urban Institute, August 22, 2023, 47, https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/2023-08/Local%20and%20State%20Policies%20to%20Improve%20Access%20to%20Affordable%20Housing_0.pdf.

- Michael Andersen, interview with author, August 10, 2023.

- Megan Banta, “Eugene officials unanimously pass middle housing rules after months of community feedback,” The Register–Guard, May 25, 2022, https://www.registerguard.com/story/news/2022/05/25/eugene-oregon-middle-housing-passed-tweaked-planning-commission-recommendation-hb-2001-duplex/65357451007/ City of Eugene, “Middle Housing Code Changes | HB 2001,” July 12, 2023, https://www.eugene-or.gov/4244/Middle-Housing.

- Megan Banta, “How are Eugene’s proposed middle housing code changes different from a state model code?” The Register–Guard, April 16, 2022, https://www.registerguard.com/story/news/2022/04/16/middle-housing-how-eugenes-proposed-code-changes-compare-to-oregon-diverse-multi-family-homes/65350158007/.

- Mark Treskon, Jorge González-Hermoso, Noah McDaniel, and Dennis Su, “Local and state policies to improve access to affordable housing,” The Urban Institute, August 22, 2023, 47, https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/2023-08/Local%20and%20State%20Policies%20to%20Improve%20Access%20to%20Affordable%20Housing_0.pdf.

- Mark Treskon, Jorge González-Hermoso, Noah McDaniel, and Dennis Su, “Local and state policies to improve access to affordable housing,” The Urban Institute, August 22, 2023, 50–51, https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/2023-08/Local%20and%20State%20Policies%20to%20Improve%20Access%20to%20Affordable%20Housing_0.pdf.

- Michael Andersen, “Portland just passed the best low-density zoning reform in US history,” Sightline Institute, August 11, 2020, https://www.sightline.org/2020/08/11/on-wednesday-portland-will-pass-the-best-low-density-zoning-reform-in-us-history/.

- Christian Britschgi, “Portland Legalized ‘Missing Middle’ Housing. Now It’s Trying to Make It Easy to Build,” Reason, June 13, 2022, https://reason.com/2022/06/13/portland-legalized-missing-middle-housing-now-its-trying-to-make-it-easy-to-build/.

- Michael Andersen, interview with author, August 10, 2023.

- Mark Treskon, Jorge González-Hermoso, Noah McDaniel, and Dennis Su, “Local and state policies to improve access to affordable housing,” The Urban Institute, August 22, 2023, 56–57, https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/2023-08/Local%20and%20State%20Policies%20to%20Improve%20Access%20to%20Affordable%20Housing_0.pdf.

- Julia Shumway, “White House: Oregon single-family zoning law could be model for nation,” Oregon Capital Chronicle, October 29, 2021, https://oregoncapitalchronicle.com/2021/10/29/white-house-oregon-single-family-zoning-law-could-be-model-for-nation/

- “The GAP: Projects & Campaigns,” National Low Income Housing Coalition, https://nlihc.org/gap#summary-table.

- April Ehrlich, “Oregon has an extreme housing shortage. Here’s what could be done,” Oregon Public Broadcasting, July 26, 2023, https://www.opb.org/article/2023/07/26/oregon-cost-of-living-housing-construction-building-land-use-high-rent/; Office of Policy Development and Research, “2022 AHAR: Part 1—PIT Estimates of Homelessness in the U.S.,” December 2022, https://www.huduser.gov/portal/datasets/ahar/2022-ahar-part-1-pit-estimates-of-homelessness-in-the-us.html.

- “Oregon Housing Needs Analysis Legislative Recommendations Report: Leading with Production,” Oregon Department of Land Conservation and Development, Oregon Housing and Community Services, Legislative Report, December 2022, https://www.oregon.gov/lcd/UP/Documents/20221231_OHNA_Legislative_Recommendations_Report.pdf.

- Simon Mather, “New Push to Create Missing ‘Middle Housing’ in Bend,” Cascade Business News, April 12, 2022, https://cascadebusnews.com/new-push-to-create-missing-middle-housing-in-bend/; Brenna Visser, “Bend City Council approves code changes aimed at increasing housing,” The Bulletin, September 17, 2021, https://www.bendbulletin.com/localstate/bend-city-council-approves-code-changes-aimed-at-increasing-housing/article_13ed214a-17f2-11ec-a878-ab97c9c2841d.html.

- Jack Hirsh, “Bend’s big shift from single-family homes to more multifamily housing tops city’s expectations,” News Channel 21 KTVZ, January 24, 2022, https://ktvz.com/news/bend/2022/01/24/bends-big-shift-from-single-family-homes-to-more-multifamily-housing-tops-citys-expectations/.

- “Residential Infill Project,” City of Portland, August 1, 2021, https://www.portland.gov/bps/planning/rip.

- “Housing in Brief: Portland Just Ended Single-Family Zoning,” Next City, August 14, 2020, https://nextcity.org/urbanist-news/housing-in-brief-portland-just-ended-single-family-zoning.

- “New study shows promising housing production results from the Residential Infill Project (RIP),” City of Portland, July 5, 2023, https://www.portland.gov/bps/planning/rip/news/2023/7/5/new-study-shows-promising-housing-production-results-residential.

- “New study shows promising housing production results from the Residential Infill Project (RIP),” City of Portland, July 5, 2023, https://www.portland.gov/bps/planning/rip/news/2023/7/5/new-study-shows-promising-housing-production-results-residential.

- Hannah Wallace, “The Portland Art of Feel-Good Densification,” Reasons to Be Cheerful, June 8, 2023, https://reasonstobecheerful.world/portland-housing-density-residential-infill-project/.

- “New study shows promising housing production results from the Residential Infill Project (RIP),” City of Portland, July 5, 2023, https://www.portland.gov/bps/planning/rip/news/2023/7/5/new-study-shows-promising-housing-production-results-residential.

- James Burling, “America’s Sordid History of Exclusionary Zoning,” The Counselors of Real Estate 44, no. 21 (November 20, 2020), https://cre.org/real-estate-issues/americas-sordid-history-of-exclusionary-zoning/#:~:text=The%20first%20comprehensive%20zoning%20law,factories%20out%20of%20their%20neighborhoods.

- Noah Sheidlower, “The Controversial History of Levittown, America’s First Suburb,” Untapped New York, July 31, 2020, https://untappedcities.com/2020/07/31/the-controversial-history-of-levittown-americas-first-suburb/.

- Rachelle Blidner, “Legacy of exclusion is tough to shed,” Newsday, November 17, 2019, https://projects.newsday.com/long-island/levittown-demographics-real-estate/.

- Eli Kahn and Salim Furth, “Breaking Ground: An Examination of Effective State Housing Reforms in 2023,” Mercatus Center, George Mason University, August 1, 2023, https://www.mercatus.org/research/policy-briefs/breaking-ground-examination-effective-state-housing-reforms-2023.

- Michael Andersen, interview with author, August 10, 2023.

- Michael Andersen, “Eight Ingredients for a State-Level Zoning Reform,” Sightline Institute, August 13, 2021, https://www.sightline.org/2021/08/13/eight-ingredients-for-a-state-level-zoning-reform/.

- Richard D. Kahlenberg, “Building a Multiraical, Cross-Party Populist Coalition for Zoning Reform: What New York Can Learn from California,” The Century Foundation, November 15, 2023, https://tcf.org/content/report/building-a-multiracial-cross-party-populist-coalition-for-zoning-reform-what-new-york-can-learn-from-california/.

- Mihir Zaveri and Luis Ferré-Sadurní, “Hochul Orders Stopgap Measures in Face of New York’s Housing Crisis,” The New York Times, July 18, 2023, https://www.nytimes.com/2023/07/18/nyregion/housing-crisis-421a-hochul.html.

- Michael Andersen, “Eight Ingredients for a State-Level Zoning Reform,” Sightline Institute, August 13, 2021, https://www.sightline.org/2021/08/13/eight-ingredients-for-a-state-level-zoning-reform/.

- Andrés Oswill, interview with author, September 11, 2023.

- Michael Andersen, “Eight Ingredients for a State-Level Zoning Reform,” Sightline Institute, August 13, 2021, https://www.sightline.org/2021/08/13/eight-ingredients-for-a-state-level-zoning-reform/.

- Richard D. Kahlenberg, “Building a Multiraical, Cross-Party Populist Coalition for Zoning Reform: What New York Can Learn from California,” The Century Foundation, November 15, 2023, https://tcf.org/content/report/building-a-multiracial-cross-party-populist-coalition-for-zoning-reform-what-new-york-can-learn-from-california/.

- Eli Kahn and Salim Furth, “Breaking Ground: An Examination of Effective State Housing Reforms in 2023,” Mercatus Center, George Mason University, August 1, 2023, https://www.mercatus.org/research/policy-briefs/breaking-ground-examination-effective-state-housing-reforms-2023.

- “The New York Housing Compact,” Governor Kathy Hochul, New York State, https://www.governor.ny.gov/programs/new-york-housing-compact (accessed November 17, 2023).