New York State, like many other states, has a housing affordability crisis, which also exacerbates large inequalities between local public education systems. Government zoning laws that constrain the supply of housing and exclude people of modest means from living in high-opportunity communities are a major cause of both problems. While most of the debates in New York over housing policy have centered around the first problem—the ways in which restrictive zoning drives up housing prices—this report focuses on an equally important and often overlooked challenge, the impact of zoning on the educational opportunities of children.

The report examines two communities in New York City’s suburban Westchester County—Scarsdale and Port Chester—and the ways in which restrictive zoning impedes educational opportunities. Earlier reports in this series have made similar comparisons of neighborhoods in Queens and Long Island.1 A subsequent report will examine communities in the Buffalo area.

This report proceeds in four parts. The first part examines how Scarsdale and Port Chester differ in their demographic makeups, home prices, and in the educational opportunities that their school systems provide. The second part examines how the two communities, though located within a short drive of one another, became so different. That section of the report takes a close look at the different zoning regimes in the two communities and the impact of other government policies, such as decisions about where to locate public housing. The third part discusses the role Westchester County generally, and Scarsdale in particular, have played in political debates about reforming zoning in New York State. The fourth part concludes with thoughts about the possibility of a better future.

Comparing Two Nearby Westchester Communities: Scarsdale and Port Chester

Westchester County is home to many of New York City’s suburbs, which are connected to Grand Central Station in Manhattan by three Metro-North Railroad lines (Harlem, Hudson, and New Haven).2 In popular television culture, Westchester is where the Petrie family, including Dick Van Dyke, a Manhattan executive, and his wife, Mary Tyler Moore, resided in a 1960s television series.3 Westchester is also the setting for E. L. Doctorow’s novel and Broadway musical, “Ragtime.”4

Home to close to 1 million residents in 2022, the population was 52.4 percent non-Hispanic white, 25.9 percent Hispanic, 16.7 percent Black, and 6.6 percent Asian. The median household income was $105,387.5

Some of Westchester’s communities are highly segregated. According to a 2023 report from the civil rights group, ERASE Racism, five of Westchester’s forty-six school districts had student populations in which 90–100 percent of students were students of color in 2021: Elmsford Union Free School District, Greenburgh Eleven Union Free School District, Mount Pleasant Cottage Union Free School District, Mount Vernon School District, and Peekskill City School District.6 At the other extreme, some Westchester County communities are segregated with high non-Hispanic white populations, such as the villages of Bronxville and Larchmont (both 81 percent non-Hispanic white), and the village of Pelham Manor and City of Rye (both 77 percent white).7

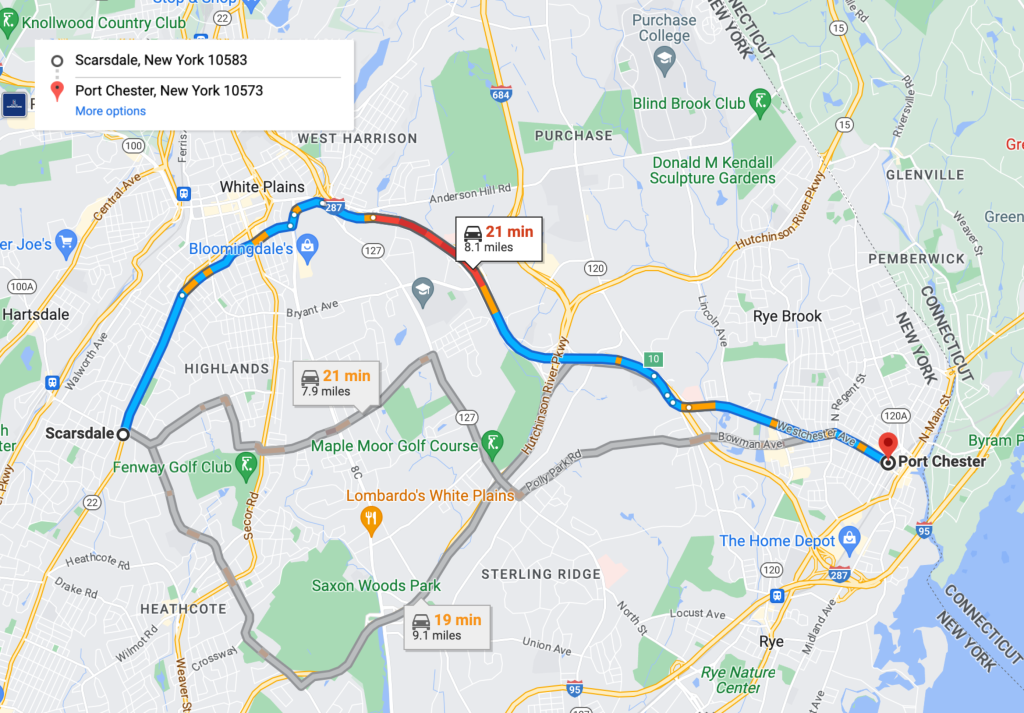

To examine the connection between zoning and educational opportunities, The Century Foundation worked with Vicki Been, a former deputy mayor for housing and economic development in New York City and now a faculty director of the Furman Center at New York University, and Been’s Furman colleagues Hayley Raetz, Jiaqi Dong, and Matthew Murphy, to identify two Westchester communities near one another that have different zoning regimes. Scarsdale and Port Chester are located just eight miles from one another, but in terms of zoning, racial and economic demographics, and the performance of the public schools, the two municipalities are enormously different.

Figure 1: Scarsdale and Port Chester are eight miles apart

Scarsdale, a community of 18,253 residents living in seven square miles, had a population that was 71.2 percent non-Hispanic white, 15.7 percent Asian, 6.5 percent Hispanic, and just 1.7 percent Black in 2021. A whopping 90.7 percent of the adult population had a bachelor’s degree or more. The median household income exceeded $250,000.8 It has been rated “the richest town on the East Coast.”9 Scarsdale has been home to celebrities such as Yoko Ono, Liza Minelli, and Judy Garland.10

Port Chester, a village of 2.4 square miles, is part of the town of Rye, but it is distinct from the City of Rye, which is mostly white and affluent. Port Chester was cut off from the City of Rye when interstate highways 287 and 95 were built.11 In 2021, Port Chester had 31,693 residents, of whom 64.2 percent were Hispanic, 27.7 percent non-Hispanic white, 5.2 percent Black, and 1.4 percent Asian. Just 31.3 percent of adults had a bachelor’s degree or more—a fifty-nine-point gap in college attainment compared with Scarsdale. The median household income in Port Chester was $88,903—a small fraction of the income in Scarsdale. (See Table 1 and Appendix 1.)

In the 1960s, Port Chester attracted Hispanic immigrants to local factories, but after those factories shut down, the village evolved into a community, says the New York Times, that services “the affluent suburbs as landscapers, day laborers, house cleaners and child-care providers.”12 The village is home to two commercial bakeries.13

Table 1

| SCARSDALE AND PORT CHESTER DEMOGRAPHICS, 2021 | ||

| Scarsdale | Port Chester | |

| Median household income | $250,000 + | $88,093 |

| Percentage of adults with a bachelor’s degree or higher | 90.7% | 31.1% |

| White (non-Hispanic) | 71.2% | 27.7% |

| Black | 1.7% | 5.2% |

| Hispanic | 6.5% | 64.2% |

| Asian | 15.7% | 1.4% |

| Source: NYU Furman Center. For more details, see Appendix 1. | ||

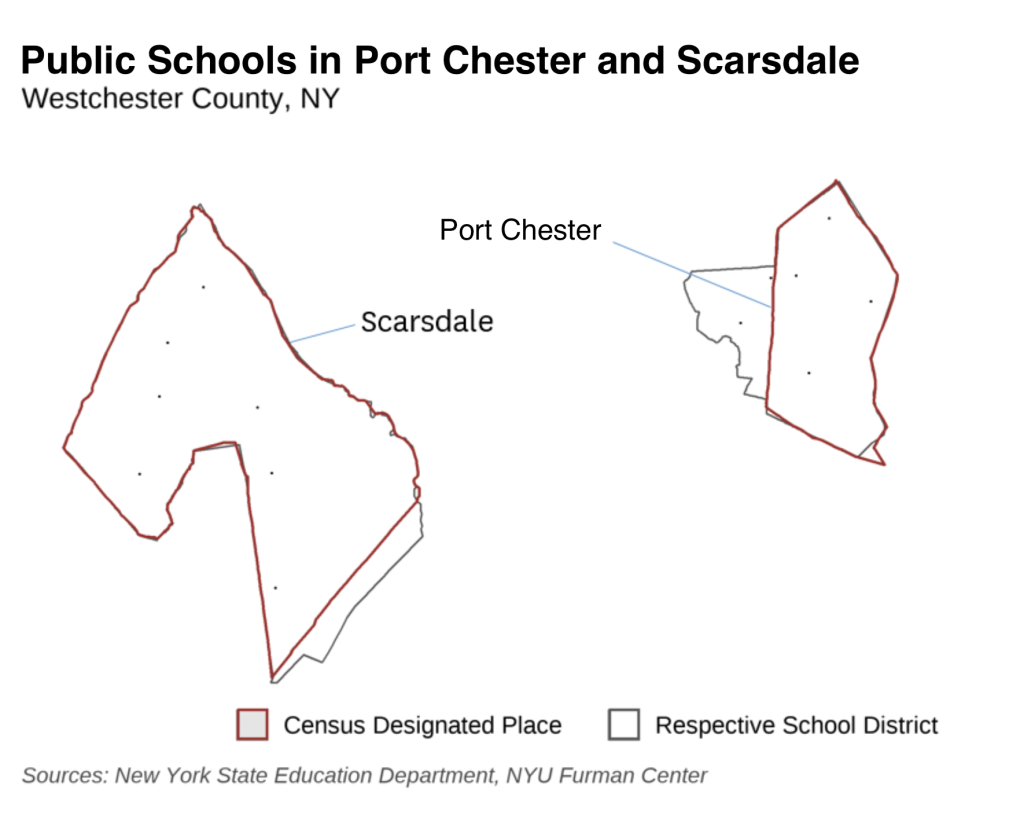

The local public school student populations in Scarsdale and Port Chester reflect the different demographics of the two communities. As shown in Figure 2, prepared by the Furman Center, the public school students in the Scarsdale Census Designated Place (CDP) attend the Scarsdale Public Schools. Public school students who reside in Port Chester are assigned to attend Port Chester–Rye School District, which is somewhat larger than Port Chester CDP. As the map shows, the middle school and high school are located outside of the Port Chester CDP boundary line.

Figure 2

In Scarsdale schools, a stunning 0 percent of students were reported as eligible for free or reduced price lunch in 2021 at the elementary school level (meaning none come from families at or below 185 percent of the poverty line). In Port Chester, three-quarters of public school students were eligible for subsidized lunch.

Researchers have consistently found that in order to provide genuine equal opportunity, schools with higher concentrations of poverty like those in Port Chester should spend more money per pupil. In fact, however, the per pupil expenditure in 2020 was $15,119 in Port Chester, almost $5,500 less per pupil than in Scarsdale, where the expenditure was $20,591. This differential does not count private giving through Parent Teacher Associations, which adds hundreds of millions of dollars to school budgets nationally.14 Affluent communities such as Scarsdale are much more likely to raise private funds than less affluent communities such as Port Chester. In May 2023, for example, the Fox Meadow Elementary PTA in Scarsdale offered gifts for capital improvements totalling close to $50,000.15 Extra public resources in Scarsdale were able to purchase the children of affluent families in Scarsdale extra educational benefits, such as lower student–teacher ratios. In 2021, for example, there were 7.4 students for every teacher in Scarsdale at the elementary school level, compared with 10.1 students for every teacher in Port Chester. (See Table 2 and Appendixes 1 and 3). Research from Tennessee and elsewhere has generally found that smaller class sizes are beneficial to student learning.16

Teacher experience can improve academic achievement for children, yet in Port Chester, 17.7 percent of teachers were in their first or second year of teaching in 2017, twenty-five times the rate for Scarsdale, where just 0.7 percent of teachers were in their first or second year. More recent data which examines the proportion of teachers with less than five years experience also shows that Scarsdale has fewer inexperienced teachers than Port Chester. It is difficult to directly compare access to Advanced Placement courses across the two jurisdictions because Scarsdale jettisoned AP courses in favor of its own college level Advanced Topics (AT) classes several years ago.17 But it is notable that Scarsdale provides access to 25 AT classes, while Port Chester students have access to 15 AP classes.

Table 2

| SCARSDALE AND PORT CHESTER: SCHOOL FACTORS AND OUTCOMES | ||

| Scarsdale | Port Chester | |

| Percent of students qualifying for free and reduced-price lunch, elementary level, 2021–22 | 0.0% | 74.6% |

| Per-pupil expenditure, 2020 | $20,591 | $15,119 |

| Student–teacher ratio, elementary level, 2021 | 7.4 | 10.1 |

| Share of teachers in their first or second year of teaching, 2017 | 0.7% | 17.7% |

| Percentage of students performing at grade level in English, 2019 | 87.1% | 32.0% |

| Percentage of students performing at grade level in Math, 2019 | 90.3% | 34.5% |

| Percentage of high school students who graduated in four years, 2019 | 98.9% | 84.1% |

| Source: NYU Furman Center. For more details, see Appendix 1. | ||

In 2019, 32 percent of Port Chester students were performing at grade level in English, compared with 87 percent of students in Scarsdale—a staggering 55-percentage-point gap. In math, 35 percent of Port Chester students performed at grade level, compared with 90 percent of Scarsdale students, also a 55-point gap. In 2021, 84 percent of Port Chester public high school students graduated in four years, compared with 99 percent of Scarsdale public high school students. In the 2021–22 school year, Port Chester–Rye Union Free School District (UFSD) was designated as a “target district” under New York State’s school accountability system, meaning it was one of the districts that “struggled to prepare some of their student subgroups on some or all indicators.”18 By contrast, Scarsdale UFSD was designated one of the districts in “good standing,” meaning they demonstrated “success in all performance goals.”19

How can we explain these gaps? Students in Port Chester face a double disadvantage in reaching their full academic potential. Because three-quarters of Port Chester students come from families making less than 185 percent of the poverty line, they are much more likely to be hungry, lack high-quality health care, have access to the Internet, or a quiet place to do homework.20 But family poverty is only a partial explanation, because low-income students given a chance to attend lower-poverty schools have been found to cut the achievement gap with their middle-class peers in half in math and by one third in reading.21 On top of family poverty, economic segregation—the concentration of student poverty—also has a well-documented detrimental effect on student achievement.22

With research showing that economic segregation can harm and limit low-income students’ academic achievement, it is important to understand the role that deliberate choices such as restrictive zoning and other factors play in driving that economic school segregation.

How Did Scarsdale and Port Chester Become Separate and Unequal?

How did Scarsdale and Port Chester—and other communities in Westchester County—end up so economically and racially segregated? And how did their schools end up so unequal?

Geography does not seem to be an obvious explanation. Port Chester is nestled between very affluent communities such as Rye, Rye Brook, and Greenwich, Connecticut, and a strip of Port Chester is desirable waterfront property, facing directly on the Long Island Sound.23 Scarsdale, by contrast, is landlocked.

To a certain extent, economic and racial segregation reflects individual family choices about where to live and the working of the marketplace (communities with higher performing schools, for example, command higher real estate prices). But segregation in Westchester is also the result of government policies, such as enforcement of racially restrictive covenants. These covenants forbade homeowners from reselling a property to Black, Hispanic, Asian, or Native American people.24 Such covenants were in widespread use in New York suburbs. One survey of 300 developments built between 1935 and 1947 in Westchester County (and other Manhattan suburbs such as Queens and Nassau County) found that “56 percent had racially restrictive covenants. Of the larger subdivisions (those with seventy-five or more units) 85 percent had them.25 ”Racially restrictive covenants were struck down by the U.S. Supreme Court in 1948.26

Today, among the most important government policies and practices driving segregation include (1) decisions about where to place public housing; and (2) flagrant income discrimination through exclusionary zoning (which disproportionately hurts people of color).

Decisions about Where to Place Public Housing

In the 1980s, Westchester became famous in national housing circles by taking extreme steps to avoid housing desegregation. The Westchester city of Yonkers, which had placed most public housing in the southwest section of town, nearly went bankrupt from penalties it faced in resisting integration.27

In February 2009, Westchester was back in the news as a federal judge ruled in a lawsuit brought by a civil rights group, the Anti-Discrimination Center, that Westchester had fraudulently taken federal money after falsely claiming that it had made efforts to desegregate. In August 2009, Westchester County officials agreed to build or purchase and make available 750 affordable homes or apartments, more than 80 percent of which would be built in mostly-white suburbs. The Obama administration helped broker the settlement and Ron Sims, the deputy secretary of housing and urban development, lauded the agreement, saying “This is consistent with the president’s desire to see a fully integrated society.”28

Even though the settlement was in one sense modest—less than 1,000 units in a county of 1 million residents—many Westchester community members were outraged. Westchester’s county executive, Andrew Spano, who signed the agreement, “ignited a political firestorm,” one observed noted, and he was defeated in the November 2009 election by Republican Rob Astorino, who railed against the settlement. Astorino went so far as to claim that in Westchester County “we have no exclusionary zoning.”29

Notably, the opposition to the settlement was sometimes more rooted in class than race. One Black resident of a high-income community in Westchester County, for example, opposed the Obama administration’s legal efforts to promote low-income housing, arguing, “I am appalled at this decision to reward those individuals who . . . chose the easy way out instead of dedicating oneself to hard work.”30

In a 2012 analysis for Pro Publica, journalist Nikole Hannah-Jones noted that the Obama administration had not done much to enforce the 2009 settlement. In fact, eighteeen of the affordable units that were part of the settlement to desegregate were placed in Port Chester, an already working-class and heavily minority community.31 Cherie Michaux, a single mother who is an assistant teacher, told Hannah-Jones that she would like to live in an affordable unit in the City of Rye, with its superb public schools, but was resigned to remaining in Port Chester, which she described as “that big old melting pot of those who can’t make it.”32

In the 2012 report, Hannah-Jones said that 73 percent of affordable housing built by Westchester County in the previous two decades were built in eleven disproportionately Black and Hispanic neighborhoods. Scarsdale, she noted, “did not add a single unit of affordable housing during those years.”33

In the 2020 presidential campaign, Donald Trump specifically cited the Westchester County settlement as an example of an effort to “destroy the suburbs.” But the settlement had still not been fully enforced. In July 2021, Craig Gurian, executive director of the Anti-Discrimination Center which brought the lawsuit, was deeply frustrated. He wrote: “over the course of nearly 12 years, from 2009 to the present, the central provisions of the order were not enforced, and the fundamental goal of the order was not achieved.” Some housing was built in exclusionary suburbs such as Larchmont, but even in that instance, it was placed right next to railroad tracks. Overall, only about 50 percent of new units were built in mostly white towns.34 In August 2021, Westchester was released from the housing settlement, and the county executive, George Latimer, said “I am thrilled that we are able to put it behind us.”35 Scarsdale, Gurian noted in 2021, was not required to build any affordable housing.36

Income Discrimination through Zoning

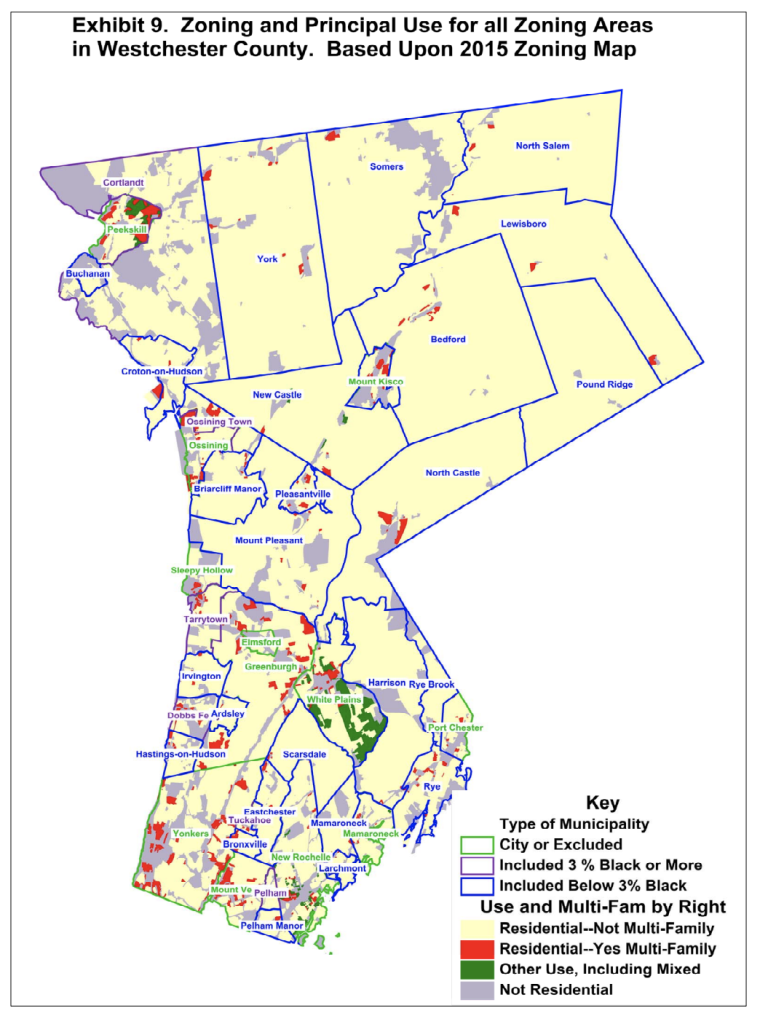

In addition to discriminatory government judgements about where to place public housing, zoning has been a prime driver of residential segregation. Government-sponsored zoning restrictions that forbid multifamily housing, or even single-family homes on modest-sized plots of land, are pervasive in American communities, including in Westchester County. According to Princeton sociologist Douglas Massey and his colleagues: “Density zoning is now the most important mechanism promoting class and racial segregation” in the United States.37

A 2012 analysis of the fifteen most exclusionary Westchester communities (where Black populations were less than 2 percent of total residents) found that “only 1.6 percent of available land is set aside for apartments or condos.”38 And a 2015 analysis by the Anti-Discrimination Center confirmed that bans on multifamily housing in Westchester County are widespread. (See Figure 3.)

FIGURE 3: Zoning and Principal Use for all Zoning in Westchester County (2015)

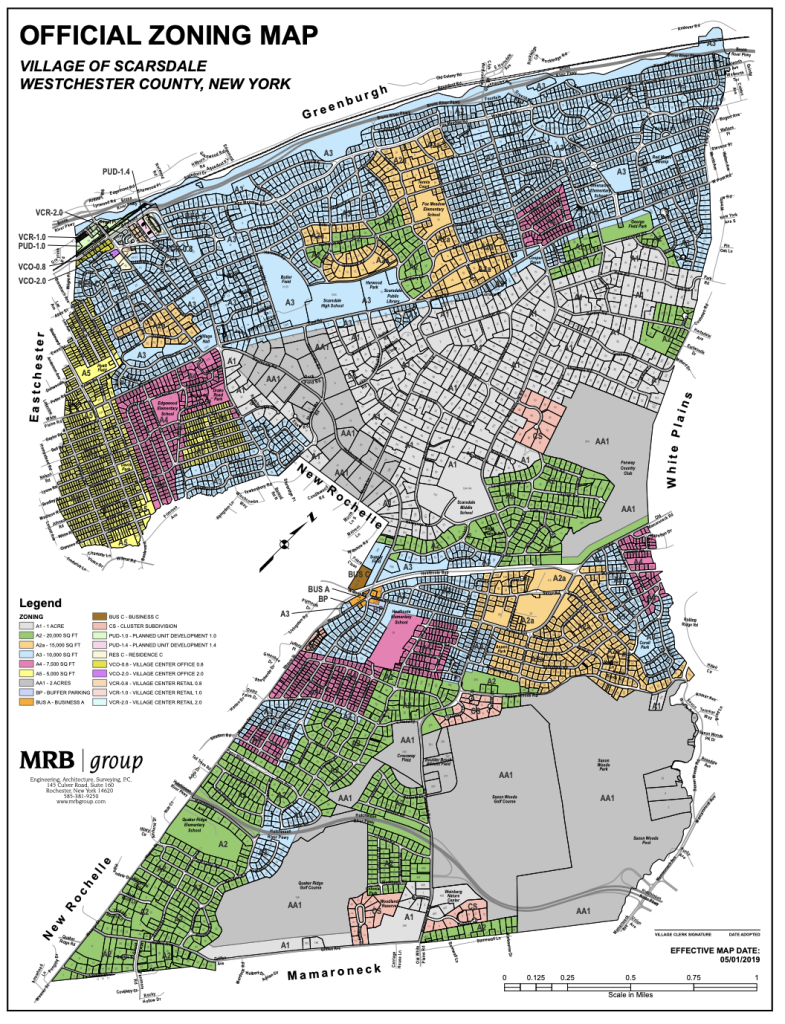

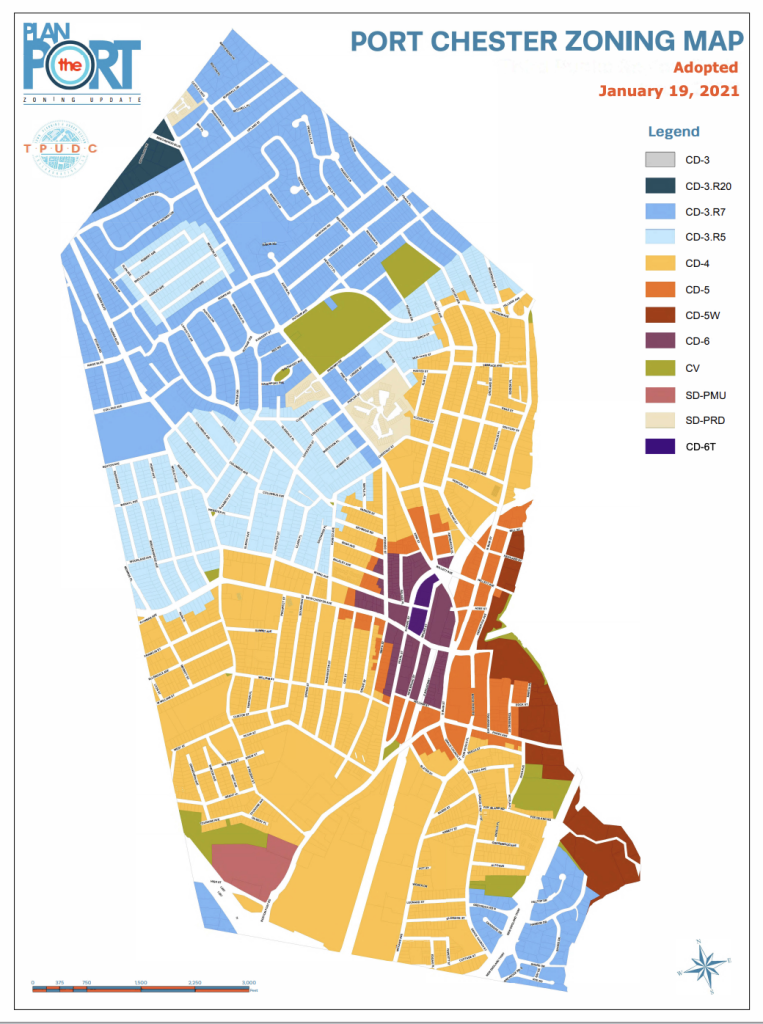

A comparison of the zoning codes in Scarsdale and Port Chester vividly illustrate the markedly different ways communities approach zoning.

In Scarsdale, as Vicki Been notes in Appendix 2, multifamily homes are relegated to “a few parcels” in the entire community. She writes: “The vast majority of the Village is zoned for single-family use on lots of at least 10,000 feet.” (See Figure 4.) In 2021, just 0.2 percent of Scarsdale’s lot area was made up of existing structures classified as two- or three-family homes or apartments.

Figure 4: Scarsdale Zoning Map

These zoning restrictions are longstanding. When Scarsdale was made accessible to New York City by train over a century ago, village officials began to clamp down on the possibility of apartments, the New York Times reports.39 Among Westchester communities, Scarsdale was an early adopter of exclusionary zoning policies, embracing a strict code to screen out less expensive housing in the 1920s.40

Later, in the 1960s, a plan to build low- and moderate-income apartments in Scarsdale was opposed to prevent the creation of an “isolated urban ghetto.”41 In the 2020s, the same dynamic has appeared to be at play. When developers proposed to redevelop a decrepit parking garage into apartment units, including some that would be affordable, community opposition has been strong and thus far stymied the project.

Sometimes, the arguments against the proposed apartments appeared farfetched. Some opponents argued, for example, that the public schools could not make room for more students.42 But in Scarsdale, demographers have projected declining enrollment in the public schools. A 2019 article noted, for example, that “enrollment for kindergarten in Scarsdale was down—way down,” so class sections had to be cut.43 It is notable that concerns about overcrowding are not typically raised when older neighbors move out of a community and new families with young children move into single-family homes. No one objects to say the schools cannot possibly accommodate new children.

Compare Scarsdale’s highly restrictive zoning to that found in Port Chester. As Been notes in Appendix 2, “Port Chester allows duplexes, townhouses, and multifamily buildings of between three and fifteen stories on approximately half its land.” (See Figure 5.) In 2021, nearly one-quarter (23.5 percent) of lot area was classified as two- or three-family lots or apartments.

Figure 5: Port Chester Zoning Map

Recent growth in Scarsdale and Port Chester reflect their very different zoning regimes. In Port Chester, 41 percent of units (24 of 58 units) authorized to be built between 2014 and 2021 were for multifamily housing. In Scarsdale, none (0 of 218 units) were for multifamily homes. Although real estate developers typically make more money building multifamily housing than single-family homes in wealthy areas, Scarsdale essentially forbids it.44

Table 3

| SCARSDALE AND PORT CHESTER HOUSING POLICIES AND OUTCOMES | ||

| Scarsdale | Port Chester | |

| Share of lot area, existing structures classified as two- or three-family residences or apartments, 2021 | 0.2% | 23.5% |

| Share of new units authorized that are single-family housing, 2014 to 2021 | 100% (218 of 218) | 59% (34 of 58) |

| Median single-family housing price, 2020 | $1,648,925 | $592,242 |

| Share of occupied housing, occupied by renters, 2021 | 9.5% | 56.6% |

| Population density per square mile, 2020 | 2,700 | 12,400 |

| Growth of population, 2010 to 2020 | 6.3% | 9.4% |

| Source: NYU Furman Center. For more details, see Appendix 1. | ||

Moreover, Scarsdale drives housing prices up even higher by requiring that single-family homes often be built on very large lots. The Wharton Density Restrictions Index gives Scarsdale the most restrictive rating (4 out of 4) because some of the minimum lot size requirements exceed two acres. Port Chester, by contrast, receives a 1 (least restrictive) rating because its largest minimum lot sizes are less than half an acre. Astonishingly, even some of the areas nearby the Scarsdale rail station now have a two-acre lot requirement.45

Scarsdale does approve permits slightly more quickly than Port Chester (eleven months on average, as compared with thirteen months), but that fact is of little help to families who cannot afford a single-family home. While the overall Wharton Land Use Index rates both communities as highly restrictive, in fact, as Been notes, a closer examination shows Scarsdale is in fact far more restrictive, especially in its updated code.46 (See Appendix 1 and 2.)

In 2020, the median single-family housing price in Scarsdale was a whopping $1.65 million, or almost triple the $592,000 median price of a home in Port Chester. In Scarsdale, renters are rare. Fewer than 10 percent of residents rented in Scarsdale in 2021, while more than half did so in Port Chester.

Overall, Scarsdale’s exclusionary policies mean Port Chester had more than four times as many people per square mile (12,400) as Scarsdale (2,700) in 2020. Scarsdale’s population also grew more slowly between 2010 and 2020 (6.3 percent) than Port Chester’s did (9.4 percent).

The Role of Westchester County and Scarsdale in Derailing Zoning Reform

As the widely disparate zoning of Scarsdale and Port Chester show,Westchester County—like so many counties across the country—leaves it to local municipalities to decide housing policies within their boundaries. Even when this devolution of authority results in significant residential segregation, there is strong resistance to changing it: when state legislators and officials tried to launch a statewide zoning reform effort that would have curtailed the ability of localities to severely limit housing growth through restrictive zoning, officials from Westchester County—particularly Scarsdale—were among those working hardest to kill it.

The battle came in the winter and spring of 2023, in response to Governor Kathy Hochul’s proposed New York Housing Compact to build 800,000 new homes over the next decade. Under the Compact, downstate municipalities would have been given the goal of increasing their housing supply by 3 percent every three years. (Upstate communities would have been asked to seek to increase housing supply by 1 percent every three years.) Under the proposal, if communities failed to reach those goals, the state would require municipalities to provide applicants for housing permits with a fast track approval process. In addition, downstate areas would need to rezone for greater housing within a half mile of commuter railway and subway stations.47

Hochul’s plan would have heavily impacted Westchester, as it would have Long Island, because those two regions build very little new housing—much less than is built just over the river from New York City in New Jersey, for example.48 Westchester would also have been heavily affected by Hochul’s proposal that downstate areas would need to rezone for greater housing within a half mile of commuter railway and subway stations. Localities would have to allow at least fifty housing units per acre near Metro-North stations, which are dotted throughout Westchester County.49

Opposition from Westchester County officials was strong. In February 2023, twenty-five Westchester mayors and supervisors signed a letter opposing Hochul’s reforms.50 The Westchester County executive, George Latimer, a Democrat, also voiced opposition.51

Scarsdale’s member of the New York Assembly, Amy Paulin, a Democrat, said Hochul’s “proposal would change the complexity of our county in a way that doesn’t make sense.”52 Westchester County’s Andrea Stewart-Cousins, the Democratic leader of the State Senate, meanwhile, rejected Hochul’s plan and called instead for financial incentives to encourage communities to voluntarily permit more housing.53

Notably, some Westchester leaders, especially those representing more diverse communities, including the mayors of Yonkers, New Rochelle, and Mount Vernon, did not sign a letter of opposition to Hochul’s plan. The mayor of White Plains, Tom Roach, affirmatively praised Hochul’s Housing Compact.54

But overall, the suburbs—including Westchester—were widely seen as the political force that killed Hochul’s housing reforms. One Assembly source told New York Focus, “There were a lot of members who though they’d get killed in re-election if they were overriding local control.” The source said: “All the suburban members were very thankful that the mandates are out.”55

Melanie Spivak, a Scarsdale Neighborhood Associations board member, celebrated the defeat of Hochul’s plan. “Local control of our zoning laws and building requirements are imperative to protecting our unique village,” she said.56

Governor Hochul’s housing plan was slated to be “the most consequential” reform in decades, a “potential centerpiece for her first term.” But she ended up suffering a “spectacular failure,” the New York Times noted. And “the most passionate resistance came from legislators representing Westchester and Long Island suburbs.”57

What’s particularly puzzling is that most (though not all) of the suburbs of Long Island and Westchester lean left politically. True enough, Suffolk County on Long Island is politically mixed—it split evenly, 49 percent to 49 percent, when voting in the race between Joe Biden and Donald Trump in 2020. But Nassau County went 54 percent to 45 percent for Biden, and Westchester County went an astonishing 68 percent to 31 percent for Biden.58 Scarsdale’s voting was even more liberal, supporting Biden with about three quarters of the vote.59 And yet liberal values, which would normally prize inclusivity and sympathy for those struggling with high housing prices, were not on display in the fights over zoning.

Creating a Better Future

When liberal communities back exclusionary policies, people chalk it up to an inevitable triumph of self-interest over values. But when it comes to the impact of housing policies on education, there are important ways in which it can be in the self-interest of parents in places like Scarsdale to reduce the exclusionary barriers they have erected.

It is true that when poor and working-class families and their children are kept out of a neighborhood through exclusionary zoning laws, the schools there will boast higher average test scores—the product of students who have had the most resources and opportunities in life. But that exclusion also comes with big educational costs as well. Exclusion robs wealthy Scarsdale students of the chance to learn from students who bring different life experiences to the classroom. Research from Amy Stuart Wells and colleagues finds that “students’ exposure to other students who are different from themselves and the novel ideas and challenges that such exposure brings leads to improved cognitive skills, including critical thinking and problem solving.”60 More diverse schools have also been found to enhance student engagement, civil participation, and a sense of belonging.61 Diversity can build greater empathy as well. Most parents want schools to help their students to learn academic skills, develop a deeper understanding of the world, and become better people. Researchers have identified an important group of privileged “happiness-oriented parents” who actively seek a diverse and welcoming setting, rather than an exclusive and academically cut-throat environment, for their children.62 The exclusionary laws in place frustrate those goals.

And if parents in places like Scarsdale want to instill liberal values in their children, what better way would there be to do so than to demonstrate these values by fighting against exclusionary zoning? In New York State, more than half of residents spend at least 30 percent of their income on housing.63 There simply is not enough housing being built in the state, and because of that, prices are going up for the housing that exists.64 Imagine if parents in Scarsdale, instead of saying they don’t want more housing because it will hurt the “character” of Scarsdale, recognized that by banning apartments, they were making housing more limited and expensive, and making the lives of poor and working class families a bit more miserable. Moreover, what if they recognized that, by denying these families the chance to live in Scarsdale, they were shutting the door on the children in these families, denying them better educational opportunities?65

In fighting against exclusionary zoning, it is important to remember that NIMBY forces do not always win. Although New York has failed to enact major housing reform to address affordability and inequality, failure is by no means inevitable. The State of California sought to enact reform in 2018, 2019, and 2020, and failed each time, but on the fourth try—in September 2021—it eliminated exclusive single-family zoning statewide.66

In forging a path forward, New Yorkers must recognize that exclusionary zoning that jacks up prices and thwarts opportunity is not a victimless crime—it perpetuates housing segregation, and thus educational segregation, punishing children in less-wealthy families by denying them the chance to attend schools where they can thrive. Reform will ease housing price increases and allow students in Westchester, and New York State as a whole, to benefit from broader access to schooling opportunities. Almost seven decades after the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in Brown v. Board of Education, it is time for New York State to move beyond separate and unequal.

Appendixes

- Download Appendix 1

- Download Appendix 2

- Download Appendix 3

Notes

- Richard D. Kahlenberg, “How Housing Policies Create Unequal Educational Opportunities: The Case of Queens, New York,” The Century Foundation, April 3, 2023, https://tcf.org/content/report/how-housing-policies-create-unequal-educational-opportunities-the-case-of-queens-new-york/; and Richard D. Kahlenberg, “Housing and Educational Inequality: The Case of Long Island,” The Century Foundation, June 1, 2023, https://tcf.org/content/report/housing-and-educational-inequality-the-case-of-long-island/.

- Metro-North Railroad website, https://new.mta.info/agency/metro-north-railroad.

- Zak Failla, “New Rochelle History Celebrated with New Dick Van Dyke Way,” New Rochelle Daily Voice, November 24, 2017, https://dailyvoice.com/new-york/newrochelle/lifestyle/new-rochelle-history-celebrated-with-new-dick-van-dyke-way/727566/.

- Lisa W. Foderaro, “Doctorow’s House, His ‘Ragtime’ Inspiration, Is for Sale,” New York Times, December 2, 1999, https://archive.nytimes.com/www.nytimes.com/books/00/03/05/specials/doctorow-house.html.

- “Quick Facts: Westchester County, New York,” U.S. Census Bureau, https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/westchestercountynewyork.

- “ERASE Racism Issues Research Report on Inequity in New York’s Public Schools: Analyzing a Decade of Data, the Report Busts Longstanding Myths About School Segregation,” ERASE Racism, April 24, 2023, https://www.eraseracismny.org/component/content/article/28/1057; and “Empire State Inequality: A Decade of School Funding Disparity and Its Effects,” ERASE Racism, 5-6, https://www.eraseracismny.org/storage/documents/Reports/PDF_version_Empire_State_Inequities.pdf.

- “Quick Facts” for the Village of Bronxville, U.S. Census Bureau, https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/bronxvillevillagenewyork,US/PST045222; the Village of Larchmont, https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/larchmontvillagenewyork,US/PST045222; the Village of Pelham Manor, https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/pelhammanorvillagenewyork,US/PST045222; and the City of Rye, https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/ryecitynewyork,US/PST045222.

- See Appendix 1; and “Quick Facts: Scarsdale Village, New York,” U.S. Census Bureau, https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/scarsdalevillagenewyork.

- See Appendix 2.

- Tom Gantert, “Scarsdale, home to the famous, and some highly paid educators,” The Center Square, New York, September 22, 2022, https://www.thecentersquare.com/new_york/article_a1726ea2-39bc-11ed-9ed4-a3292274ba6c.html.

- Nikole Hannah-Jones, “Soft on Segregation: How the Feds Failed to Integrate Westchester County,” Pro Publica, November 2, 2012, https://www.propublica.org/article/soft-on-segregation-how-the-feds-failed-to-integrate-westchester-county.

- Lisa Prevost, “Port Chester, N.Y.: A ‘Tiny Little Village’ With a Lot of Development,” New York Times, March 1, 2023, https://www.nytimes.com/2023/03/01/realestate/port-chester-ny-housing.html.

- See Appendix 2.

- See “Hidden Money: The Outsized Role of Parent Contributions in School Finance,” Center for American Progress, April 8, 2017, https://www.americanprogress.org/article/hidden-money/.

- See Todd Sliss, “School board debates accepting large capital improvement gifts from PTA’s,” Scarsdale Inquirer, May 27, 2023, https://www.scarsdalenews.com/top_stories/school-board-debates-accepting-large-capital-improvement-gifts-from-ptas/article_2ece9416-fc35-11ed-952a-7304d84acb14.html.

- See Matt Barnum, “Does class size really matter? A Chalkbeat look at the research,” Chalkbeat, June 10, 2022, https://www.chalkbeat.org/2022/6/10/23162544/class-size-research.

- Jay Mathews, “A high school ditched AP for its own advanced classes. Why aren’t they available to all of its students?” Washington Post, August 24, 2018, https://www.washingtonpost.com/local/education/a-high-school-ditched-ap-for-its-own-advanced-classes-why-arent-they-available-to-all-of-its-students/2018/08/24/7d656f02-a57b-11e8-97ce-cc9042272f07_story.html.

- “Port Chester-Rye UFSD Data, 2021–22,” New York State, https://data.nysed.gov/profile.php?instid=800000034957 .

- “Scarsdale UFSD Data 2021–22,” New York State, https://data.nysed.gov/profile.php?instid=800000034921.

- See, e.g., Richard Rothstein, Class and Schools: Using Social, Economic and Educational Reform to Close the Black-White Achievement Gap (New York: Teachers College Press, 2004).

- Heather Schwartz, “Housing Policy Is School Policy: Economically Integrative Housing Promotes Academic Success in Montgomery County, Maryland,” The Century Foundation, 2010, https://tcf.org/content/commentary/housing-policy-is-school-policy.

- See, e.g., The Future of School Integration: Socioeconomic Diversity as an Education Reform Strategy, ed. Richard D. Kahlenberg (New York: Century Foundation Press, 2012).

- Median household incomes in 2021 were $207,930 (City of Rye); $179,205 (Village of Rye Brook) and $180,447 (Greenwich, Connecticut). See U.S. Census Bureau, “Quick Facts: Rye City, New York,” https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/ryecitynewyork; U.S. Census Bureau, “Quick Facts: Rye Brook Village, New York,” https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/ryebrookvillagenewyork,ryecitynewyork/PST045222, and “Greenwich Residents,” Niche, https://www.niche.com/places-to-live/greenwich-fairfield-ct/residents/.

- See e.g. Cheryl W. Thompson, Cristina Kim, Natalie Moore, Roxana Popescu, and Corinne Ruff, “Racial covenants, a relic of the past, are still on the books across the country,” National Public Radio, November 17, 2021, https://www.npr.org/2021/11/17/1049052531/racial-covenants-housing-discrimination

- Richard Rothstein, The Color of Law: A Forgotten History of How Our Government Segregated America (New York: Liveright, 2017), 79–80.

- See Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U.S. 1 (1948). Communities change over time, of course, and some communities that once had racially restrictive covenants today may have very diverse populations. But these covenants set in motion segregated patterns that in some cases persist to this day.

- Sam Roberts, “Westchester Adds Housing to Desegregation Pact,” New York Times, August 10, 2009, https://www.nytimes.com/2009/08/11/nyregion/11settle.html.

- Sam Roberts, “Westchester Adds Housing to Desegregation Pact,” New York Times, August 10, 2009, https://www.nytimes.com/2009/08/11/nyregion/11settle.html.

- Nikole Hannah-Jones, “Soft on Segregation: How the Feds Failed to Integrate Westchester County,” Pro Publica, November 2, 2012, https://www.propublica.org/article/soft-on-segregation-how-the-feds-failed-to-integrate-westchester-county.

- Howard Husock, “Affirmatively Furthering Fair Housing: Are There Reasons for Skepticism?” in Furthering Fair Housing: Prospects for Racial Justice in America’s Neighborhoods, ed. Justin P. Steil, Nicholas F. Kelly, Lawrence J. Veale and Maia S. Woluchem (Philadelphia, Penn.: Temple University Press, 2021), 132–33 (noting response to August 2009 Obama administration settlement).

- Nikole Hannah-Jones, “Soft on Segregation: How the Feds Failed to Integrate Westchester County,” Pro Publica, November 2, 2012, https://www.propublica.org/article/soft-on-segregation-how-the-feds-failed-to-integrate-westchester-county.

- Nikole Hannah-Jones, “Soft on Segregation: How the Feds Failed to Integrate Westchester County,” Pro Publica, November 2, 2012, https://www.propublica.org/article/soft-on-segregation-how-the-feds-failed-to-integrate-westchester-county.

- Nikole Hannah-Jones, “Soft on Segregation: How the Feds Failed to Integrate Westchester County,” Pro Publica, November 2, 2012, https://www.propublica.org/article/soft-on-segregation-how-the-feds-failed-to-integrate-westchester-county.

- Craig Gurian, “It’s Past Time the Biden Administrations Ended Segregation in This Suburb,” Daily Beast, July 22, 2021, https://www.thedailybeast.com/its-past-time-the-biden-administration-ended-segregation-in-new-yorks-westchester-county.

- “County Executive George Latimer Announces Termination of Affordable Housing Settlement in Westchester,” Westchester County, August 4, 2021, https://www.westchestergov.com/home/all-press-releases/9026-county-executive-george-latimer-announces-termination-of-affordable-housing-settlement-in-westchester.

- Craig Gurian, “It’s Past Time the Biden Administrations Ended Segregation in This Suburb,” Daily Beast, July 22, 2021. https://www.thedailybeast.com/its-past-time-the-biden-administration-ended-segregation-in-new-yorks-westchester-county?ref=scroll

- Douglas S. Massey, Len Albright, Rebecca Casciano, Elizabeth Derickson, and David N. Kinsey, Climbing Mount Laurel: The Struggle for Affordable Housing and Social Mobility in an American Suburb (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 2013), 19.

- Nikole Hannah-Jones, “Soft on Segregation: How the Feds Failed to Integrate Westchester County,” Pro Publica, November 2, 2012, https://www.propublica.org/article/soft-on-segregation-how-the-feds-failed-to-integrate-westchester-county.

- Mihir Zaveri, Luis Ferré-Sadurní, and Michael D. Regan, “Can New York Fix Its Housing Crisis? It Depends on the Suburbs,” New York Times, March 29, 2023, https://www.nytimes.com/2023/03/29/nyregion/nyc-suburbs-homes-hochul.html.

- Nikole Hannah-Jones, “Soft on Segregation: How the Feds Failed to Integrate Westchester County,” Pro Publica, November 2, 2012, https://www.propublica.org/article/soft-on-segregation-how-the-feds-failed-to-integrate-westchester-county.

- Mihir Zaveri, Luis Ferré-Sadurní, and Michael D. Regan, “Can New York Fix Its Housing Crisis? It Depends on the Suburbs,” New York Times, March 29, 2023, https://www.nytimes.com/2023/03/29/nyregion/nyc-suburbs-homes-hochul.html.

- Mihir Zaveri, Luis Ferré-Sadurní, and Michael D. Regan, “Can New York Fix Its Housing Crisis? It Depends on the Suburbs,” New York Times, March 29, 2023, https://www.nytimes.com/2023/03/29/nyregion/nyc-suburbs-homes-hochul.html.

- “Demographer Provides 5-Year Enrollment Projection for the Scarsdale Schools,” Scarsdale 10583, January 15, 2019, https://scarsdale10583.com/section-table/103-school-news/7344-demographer-provides-5-year-enrollment-projection-for-the-scarsdale-schools.

- See Lisa Prevost, “Town After Town, Residents Are Fighting Affordable Housing in Connecticut,” New York Times, September 4, 2022, https://www.nytimes.com/2022/09/04/realestate/connecticut-affordable-housing-apartments .html (citing Peter Cabrera, the vice president of acquisitions and development for Eagle Ventures that in places where property values are expensive, “We can build both market-rate and affordable housing with no government funds or tax incentives required. The density allows the math to work.”).

- Mihir Zaveri, Luis Ferré-Sadurní, and Michael D. Regan, “Can New York Fix Its Housing Crisis? It Depends on the Suburbs,” New York Times, March 29, 2023, https://www.nytimes.com/2023/03/29/nyregion/nyc-suburbs-homes-hochul.html.

- The Wharton Land Use Index Composite metric defines both Scarsdale and Port Chester as highly restrictive. See Appendix 1. But as Been explains in Appendix 2, the Wharton Index “is based upon a zoning ordinance that Port Chester completely revised after the Wharton survey was completed.” In fact, she finds, Scarsdale bans multifamily housing in most areas, while Port Chester allows it in half its land. “The two jurisdictions impose very different levels of regulatory restrictiveness,” she writes.

- Governor Kathy Hochul, “Governor Hochul Announces Statewide Strategy to Address New York’s Housing Crisis and Build 800,000 New Homes,” January 10, 2023, https://www.governor.ny.gov/news/governor-hochul-announces-statewide-strategy-address-new-yorks-housing-crisis-and-build-800000; and Governor Kathy Hochul, “Remarks as Prepared: Governor Hochul Delivers 2023 State of the State,” January 10, 2023, https://www.governor.ny.gov/news/remarks-prepared-governor-hochul-delivers-2023-state-state.

- Luis Ferre-Sadurni and Mihir Zaveri, “A Plan to Force More Housing Development in New York Has Failed,” New York Times, April 21, 2023, https://www.nytimes.com/article/nyc-housing-hochul-long-island-westchester.html.

- See Mihir Zaveri, Luis Ferré-Sadurní, and Michael D. Regan, “Can New York Fix Its Housing Crisis? It Depends on the Suburbs,” New York Times, March 29, 2023, https://www.nytimes.com/2023/03/29/nyregion/nyc-suburbs-homes-hochul.html; and Metro-North Railroad, https://new.mta.info/agency/metro-north-railroad.

- Peter D. Kramer, “Westchester leaders, in letter, balk at Hochul housing plan. Here’s why.” Rockland/Westchester Journal News, March 3, 2023, https://www.lohud.com/story/news/local/westchester/2023/03/03/westchester-county-ny-leaders-in-letter-blast-hochul-housing-plan/69962118007/.

- Mihir Zaveri, Luis Ferré-Sadurní’ and Michael D. Regan, “Can New York Fix Its Housing Crisis? It Depends on the Suburbs,” New York Times, March 29, 2023, https://www.nytimes.com/2023/03/29/nyregion/nyc-suburbs-homes-hochul.html.

- Mihir Zaveri, Luis Ferré-Sadurní, and Michael D. Regan, “Can New York Fix Its Housing Crisis? It Depends on the Suburbs,” New York Times, March 29, 2023, https://www.nytimes.com/2023/03/29/nyregion/nyc-suburbs-homes-hochul.html.

- Luis Ferre-Sadurni and Mihir Zaveri, “A Plan to Force More Housing Development in New York Has Failed,” New York Times, April 21, 2023, https://www.nytimes.com/article/nyc-housing-hochul-long-island-westchester.html.

- Peter D. Kramer, “Westchester leaders, in letter, balk at Hochul housing plan. Here’s why,” Rockland/Westchester Journal News, March 3, 2023, https://www.lohud.com/story/news/local/westchester/2023/03/03/westchester-county-ny-leaders-in-letter-blast-hochul-housing-plan/69962118007/. These communities are more heavily Black and Latino than many other Westchester communities. See Nikole Hannah-Jones, “Soft on Segregation: How the Feds Failed to Integrate Westchester County,” Pro Publica, November 2, 2012, https://www.propublica.org/article/soft-on-segregation-how-the-feds-failed-to-integrate-westchester-county.

- Sam Mellins, “The State Assembly Is Foreclosing Hochul’s Housing Supply Plan,” New York Focus, April 18, 2023, https://nysfocus.com/2023/04/18/hochul-housing-compact-dead-assembly-budget.

- Joanne Wallenstein, “Hochul’s Housing Plan Shelved,” Scarsdale 10583, April 23, 2023, https://scarsdale10583.com/section-table/10205-hochul-s-housing-party-shelved.

- Luis Ferré-Sadurní and Mihir Zaveri, “New York Officials Failed to Address the Housing Crisis. Now What?” New York Times, April 27, 2023, https://www.nytimes.com/2023/04/27/nyregion/nyc-housing-crisis.html; and Grace Ashford, “Gov. Hochul Gets a Budget Deal, but No Signature Win,” New York Times, April 28, 2023, https://www.nytimes.com/2023/04/28/nyregion/hochul-budget-ny.html.

- “New York Presidential Results,” Politico, January 6, 2021, https://www.politico.com/2020-election/results/new-york/.

- David Leonhardt, “What’s the Matter with Scarsdale?” New York Times, November 4, 2021, https://www.nytimes.com/2021/11/04/briefing/democrats-election-working-class-voters.html.

- Amy Stuart Wells, Lauren Fox, and Diana Cordova-Cobo, “How Racially Diverse Schools and Classrooms Can Benefit All Students,” The Century Foundation, February 9, 2016, https://tcf.org/content/report/how-racially-diverse-schools-and-classrooms-can-benefit-all-students/.

- See “New Research: Benefits for white students in integrated schools,” Center for Education and Civil Rights at Penn State University, February 18, 2021, https://sdnotebook.com/2021/02/17/new-research-benefits-for-white-students-in-integrated-schools/ (citing research by Jack Schneider, Rachel White and Ashley Carey in the Journal Education and Urban Society).

- See “New Research: Happiness-oriented parenting and school integration,” Center for Education and Civil Rights, School Diversity Notebook, March 28, 2023, https://sdnotebook.com/2023/03/28/new-research-happiness-oriented-parenting-school-integration/ (citing Allison Roda, Molly Makris, Judith Kafka and Mira Debs, “Choice and Diversity: An Alternative Perspective on Privileged Parents Choosing Schools).

- Luis Ferre-Sadurni and Mihir Zaveri, “A Plan to Force More Housing Development in New York Has Failed,” New York Times, April 21, 2023, https://www.nytimes.com/article/nyc-housing-hochul-long-island-westchester.html.

- Mara Gay, “The Era of Shutting Others Out of New York’s Suburbs Is Ending,” New York Times, February 21, 2023, https://www.nytimes.com/2023/02/21/opinion/housing-new-york-city.html (citing data from the Citizens Budget Commission). Luis Ferre-Sadurni and Mihir Zaveri, “A Plan to Force More Housing Development in New York Has Failed,” New York Times, April 21, 2023, https://www.nytimes.com/article/nyc-housing-hochul-long-island-westchester.html.

- Heather Schwartz, “Housing Policy Is School Policy: Economically Integrative Housing Promotes Academic Success in Montgomery County, Maryland,” The Century Foundation, 2010, https://tcf.org/content/commentary/housing-policy-is-school-policy/ (finding that when low income children have a chance to live in lower-poverty neighborhoods and attend lower poverty schools, they have been able to cut the math achievement gap with middle class students in half, and the reading gap by one third).

- Richard D. Kahlenberg, Excluded: How Snob Zoning, NIMBYism, and Class Bias Build the Walls We Don’t See (New York: Public Affairs, 2023), 179.