At a time when voters are keenly focused on the cost of living, housing affordability has become a hot political issue in many parts of the country, including New York State. Policymakers, grappling with what they can do to make housing more affordable, are actively seeking to reform longstanding local exclusionary zoning laws, policies that severely limit the types of housing that can be built in communities. These laws come in a variety of forms, such as banning the construction of multifamily housing, or requiring houses to have large yards. (See text box.) By limiting the number of homes that can be built, the existing laws artificially constrain the supply of housing, and thereby increase prices above what the market would otherwise determine.

But there is another important—and sometimes underappreciated—reason to reform exclusionary zoning laws. For most people, where you live determines which public schools your children are allowed to attend. Because the vast majority of students in America attend neighborhood public schools, housing policy is also school policy.1 Exclusionary housing policies that keep many families out of high-performing public school districts thwart opportunity for low-income and working-class students, many of them students of color. In this sense, exclusionary zoning is a lynchpin in the architectural design of educational inequality in America.

Exclusionary zoning is a lynchpin in the architectural design of educational inequality in America.

This report is the first in a series from The Century Foundation (TCF)—being produced in collaboration with New York University’s Furman Center—that will examine the effects of exclusionary zoning on educational opportunity in New York State. This first report takes a close look at two communities in the New York City borough of Queens—Bayside/Little Neck and Jamaica/Hollis—that are located just six miles apart, but whose zoning regimes and schools are starkly different. Subsequent reports will examine pairs of communities in Long Island, Westchester County, and the Buffalo area.

The first part of this report lays out the larger debate over zoning reform in New York State and situates how educational opportunity fits into the discussion. The second part dives into the zoning policies in Bayside/Little Neck and Jamaica/Hollis. The third part explains how restrictive zoning impedes access to high-performing schools in Queens. The fourth part addresses political obstacles to reform in Queens. The fifth part suggests a strategy for moving forward.

Housing Reform in New York State

Earlier this year, New York Governor Kathy Hochul proposed changes to local zoning laws that are being called the most ambitious proposals by a New York Governor since the 1960s.2 Hochul, who has made housing reform one of her top priorities, devoted much of her State of the State address to the issue.3 She proposed a New York Housing Compact to build 800,000 new homes over the next decade by requiring municipalities located downstate to provide permits in order to increase their housing supply by 3 percent every three years and municipalities upstate to do so by 1 percent every three years. This would represent a big increase for downstate jurisdictions, such as Long Island, where housing stock increased just 0.6 percent and the lower Hudson Valley, where housing stock grew 1.7 percent in the past three years.4 Under the proposal, if communities fail to reach those goals, the state will require the communities to provide applicants for housing permits with a fast track approval process. In addition, downstate areas would need to rezone for greater housing within a half mile of commuter railway and subway stations. A notable provision would give extra weight for affordable units in helping a community reach its target.5

Although Hochul’s proposal is the primary focus of the statewide housing debate, other state legislators are offering important proposals as well. State Senator Brad Hoylman-Sigal (Manhattan), for example, has proposed legislation to curb existing requirements that homes only be built on large lots of land, abolish parking requirements, and allow multifamily housing of up to four units to be built anywhere in the state.6 Likewise, Senator Rachel May (Syracuse) has proposed that in communities where less than 15 percent of housing stock is affordable, a special appeals process would be created that could override local zoning board decisions that deny affordable housing projects without adequate justification. The proposal draws upon policies currently in place in states such as New Jersey and Massachusetts.7

Meanwhile the New York City Council and Mayor Eric Adams are considering efforts to streamline zoning and allow more growth in the five boroughs.8 Mayor Adams has proposed a “Get Stuff Built” agenda, with the goal of creating 500,000 new homes over the next ten years. He wants New York to become a “City of Yes,” by reducing exclusionary practices, such as parking requirements. In particular, Adams would reform zoning laws to allow more “two-family houses, accessory dwelling units, small apartment buildings, and shared housing models.”9

New York City Council Speaker Adrienne Adams, who represents Jamaica, Queens, has proposed her own “Housing Agenda to Confront the City’s Crisis,” which includes a priority on fair housing, reforming laws that limit the size of buildings on lots, and removing “regulatory barriers to housing production in high-opportunity neighborhoods.”10

In May 2022, Hochul and Eric Adams teamed up to create a “New” New York Panel, co-chaired by Richard R. Buery, Jr. of the Robin Hood Foundation and Daniel Doctoroff, a deputy mayor in Mayor Michael Bloomberg’s administration. In December 2022, the panel proposed a “Making New York Work For Everyone Action Plan” that called for a number of reforms, including legalizing accessory dwelling units (sometimes referred to as in-law suites), removing limits on the size of residential buildings relative to their lot size, and facilitating the conversion of office spaces into housing.11

A number of important groups have assembled in support of housing reform. A powerful new coalition, New York Neighbors, includes such organizations as the Regional Planning Association, the New York State Association of Affordable Housing, the New York Housing Conference, the Citizens Budget Commission, and a Yes in My Back Yard (YIMBY) group, called Open New York.12 Open New York includes housing and climate groups and their membership is largely made up of college-educated professionals.13 They are seeking to build alliances with more left-leaning affordable housing and tenant groups, which have sometimes been at war with YIMBY’s on housing reform in other states over whether market-based or government-based housing reforms should be prioritized.14

Examples of Exclusionary Practices

Single-family exclusive zoning that bars the construction of anything other than a detached single family home. Under this policy, it is illegal to build duplexes, triplexes, attached townhomes, and small garden apartments as well as larger multifamily apartment units.

Minimum lot size requirements that may forbid, for example, the subdivision of a one-acre lot to accommodate more than one home.

Minimum home size requirements that ban the construction of homes below a certain size.

Minimum parking requirements that forbid the construction of units that do not provide a certain number of off-street parking spaces per housing unit.

Bans on accessory dwelling units (also known as “in-law suites”) such as basement apartments, garage apartments or small back-yard units.

Bans on multifamily housing that do not use certain types of expensive siding, such as brick facades.

Suburban Pushback

Zoning is often seen as strictly the prerogative of cities and towns, or, in the case of large cities such as New York, of local zoning boards within the cities. But in fact the constitutional authority to regulate land use rests with the state, which can, if it chooses, delegate that authority to localities. Hochul, and by extension, Adams, are therefore fully within their rights to curb the delegation of authority to more local levels of government when they believe that power is being abused to unnecessarily restrict growth or to block certain types of people from living in a community. But that does not mean that localities will be happy about a reassertion of state or city authority.

Change won’t come without a fight, particularly from affluent suburbs that are used to having virtually complete discretion to exclude. Speaking of Hochul’s legislation, Long Island’s Nassau County executive Bruce Blakeman told Politico: “You will see a suburban uprising, the likes of which you’ve never seen before, if the state tried to impose land-use regulation on communities that had had local control for over 100 years.”15

Change won’t come without a fight, particularly from affluent suburbs that are used to having virtually complete discretion to exclude.

Lee Zeldin, who narrowly lost the 2022 governor’s race to Hochul, blasted her housing plan as, “Hochul control, not local control.”16 One Long Island assemblyman complained, “Governor Hochul’s housing proposals would be a disaster for our community. Her goal is to turn Brookhaven into the Bronx.” His reaction? “Hard pass.”17 Westchester County, Rockland County, and Suffolk County officials are also voicing opposition, forming what Gothmamist called a “suburban blockade.”18

The Possibilities for Reform

Suburban opposition on zoning issues used to spell the end to the political story. But in recent years, the power of Not in My Back Yard (NIMBY) forces has weakened. As part of this series of reports on exclusionary zoning and educational opportunity, The Century Foundation will profile successful efforts to reform laws in states such as California and Oregon and cities such as Minneapolis and Charlotte. In some of these jurisdictions, especially California and Oregon, low-income, working-class and middle-class communities came together against exclusive affluent suburbs to bring about change. This split was not partisan so much as geographical and income-based. Oregon’s reform, which was enacted in 2019, would not have succeeded without bipartisan support.19 The same was true of California’s reform in 2021.20

More recent efforts to bring about reform are underway nationally and in other states as well. In December 2022, a notoriously fractious U.S. Congress took a modest step toward zoning reform when it created an $85 million YIMBY Incentive program that rewards jurisdictions competitive grants when they reduce exclusionary zoning.21 And in Washington State, as legislators seriously consider zoning reform efforts, a 2023 poll found 71 percent in favor of legislation to legalize duplexes and small apartment buildings in areas exclusively zoned for single-family homes.22

A February 2023 Slingshot Strategies Poll, conducted on behalf of Open New York and the New York Neighbors Coalition, found that 77 percent of New York voters agreed that the state faces a housing crisis, 72 percent agreed that “it makes sense to put more housing near places like train stations, business districts and existing neighborhoods.” When it came to the specifics, 64 percent supported Hochul’s New York Housing Compact (including a majority of Republicans and conservatives) and 58 percent supported “fast-track approvals in localities that don’t meet housing targets.” The poll found that 60 percent supporting ending local bans on apartments and multifamily homes, 66 percent supported legalizing “missing middle” homes, and 60 percent supported ending parking mandates.23 A February 2023 Data for Progress poll also found that 67 percent of likely New York State voters support “legislation which promotes transit-oriented development around commuter rail stops in New York State.”24

In New York State, housing affordability is the political driver of reform, especially at a time when inflation concerns are high.

In New York State, housing affordability is the political driver of reform, especially at a time when inflation concerns are high. In the Slingshot poll, 86 percent agreed that “the cost of buying or renting a home in New York has gotten too high, and we need to do something about it.”25 In her State of the State address, Governor Hochul noted that housing is “everyone’s largest expense.” Rents are considered reasonable when families pay 30 percent or less of their income on housing. But in New York City, half of renters are allocating more than 30 percent of their income on rent and one-third spend 50 percent or more.26 In Manhattan, median monthly rent is more than $4,000.27 And outside of New York City, Hochul has noted, “rents have risen 40 to 60 percent since 2015 while home prices have risen 50 to 80 percent.”28

More public housing, affordable housing subsidies, and tenant protections are needed to address the housing crisis. But non-market solutions are not the complete answer. New York state already has double the amount of public housing per capita compared with the nation as a whole.29 Legislators should also seek to rein in prices by removing regulatory roadblocks that prevent the market from meeting the demand for more housing.

Hochul, whose parents started married life in a trailer park, said zoning laws that restrict building are a big explanation for New York’s spiraling prices.

Hochul, whose parents started married life in a trailer park, said zoning laws that restrict building are a big explanation for New York’s spiraling prices.30 Exclusionary zoning artificially limits the supply of housing in places people want to live, and consumers are forced to try to outbid each other for a very limited number of available homes. According to a 2020 analysis by the Furman Center at New York University, “By some measures, New York has the most exclusionary zoning in the country.”31

In her State of the State address, Hochul noted that in the previous ten years, New York had created 1.2 million jobs, but only 400,000 new homes.32 The problem is especially stark in the suburbs around New York City. Between 2010 and 2018, these suburbs issued less than half of the number of building permits of Boston suburbs, and one-third of Washington, D.C. suburbs, even though the populations in Boston and D.C. suburbs are considerably smaller.33 In 2021, New York State municipalities issued just 1.99 building permits per 1,000 residents, compared with 4.4 units on average nationally.34

When supply is artificially constrained, and prices skyrocket, people leave. Black families have been leaving New York City in large numbers because of rising costs. Over the past two decades, New York City’s Black population has declined by 9 percent.35 And statewide, in the most recent year, New York lost more residents of all races than any other state—220,000.36 In the Slingshot poll, 67 percent said “I have friends or family that have moved out of New York because it’s just too expensive to find a home here anymore.”37

The Role of Schooling Opportunities in the Zoning Debates

While people care deeply about housing costs, they also care a great deal about the quality of the public education that their children receive. A sometimes underappreciated aspect of the zoning reform debate is the nefarious role that exclusionary zoning plays in preventing children from families of modest means from attending high-performing public schools.

Discussing housing reform as a way to improve education access can have an important resonance with the public.

Discussing housing reform as a way to improve education access can have an important resonance with the public. In Minneapolis, the first major city to legalize duplexes and triplexes in areas that had been zoned exclusively for single-family homes, much of the debate centered around housing costs and the degree to which exclusionary zoning, by pushing development to the periphery of metropolitan areas, can exacerbate climate change by lengthening commutes. But a piece of the discussion centered around the fact that single-family exclusionary zoning effectively denied working families access to some of the best Minneapolis public schools. In fact, fourteen of the fifteen highest-performing schools were located in neighborhoods with exclusive single-family zoning, which meant they were mostly off limits to those whose budget required them to live in multifamily housing.38 (See Figure 1.) Although public school choice programs can sometimes ameliorate this problem, seven in ten Americans students attend assigned neighborhood public schools.39

Figure 1

Polling suggests that voters see it as unfair when exclusive communities put up walls that deny the children of less-affluent families access to strong schools. A 2021 poll in New Hampshire, for example, found the most effective argument with voters was one that said:

New Hampshire’s planning and zoning regulations are unfair to working families struggling to make ends meet. By limiting the new housing that can be built, these restrictions drive up rents and house prices, making housing completely unaffordable for more and more Granite Staters. Everyone knows that some towns in New Hampshire are much more expensive to buy in than others, and they tend to be the places with better schools. So poor families in New Hampshire get stuck in poverty, because they cannot afford to live where they can get a better education for their kids.40

Likewise, a 2023 poll of Virginia voters found that nearly 84 percent agreed that low-income students “should have access to the same public schools as students in high-income households”41—suggesting a possible political opening for reforms that seek to enhance educational opportunities by lowering exclusionary zoning barriers.

Housing Policies in Bayside/Little Neck and Jamaica/Hollis, Queens

To examine the relationship between zoning and education, The Century Foundation partnered with Vicki Been, a former deputy mayor for housing and economic development in New York City, and a faculty director of the Furman Center at New York University. Along with her colleagues at Furman, Hayley Raetz, Jiaqi Dong, and Matthew Murphy, Been and TCF staff have identified four pairs of communities in New York State that are geographically similar but have different zoning regimes.

The first two comparisons highlighted in this report are within the New York City borough of Queens. Although exclusionary zoning is often seen as primarily a suburban phenomenon, parts of New York City have considerable exclusionary policies. About one-quarter of Queen’s residentially zoned land, for example, is restricted to single-family homes.42

Although exclusionary zoning is often seen as primarily a suburban phenomenon, parts of New York City have considerable exclusionary policies.

Queens is famous for being New York City’s most diverse borough—a veritable United Nations of people from all over the world.43 It is home to JFK Airport, the entry way for many immigrants to America, Jelani Cobb of the New Yorker notes, and many settle nearby. More languages are spoken in Queens—in excess of 150—than in any other county in the United States.44

The New York City Department of City Planning divides the city into fifty-nine community districts, which are governed by “community boards,” and Queens has fourteen of them.45 Been and her team assembled data on Community District 11 (Bayside/Little Neck, Queens), and Community District 12 (Jamaica/Hollis, Queens).

Bayside/Little Neck and Jamaica/Hollis are located very close to one another. They are just six miles apart, a twenty-minute drive. (See Figure 2.) They have very similar average commuting times to work.46 But Bayside/Little Neck and Jamaica/Hollis sit on opposite sides of the borough’s north/south demographic divide. In parts of Queens, this north-south divide is referred to as the “Mason–Dixon Line.”47

Figure 2

The demographics of these neighboring communities are starkly different. Jamaica/Hollis is 71 percent Black and Hispanic, while Bayside/Little Neck is 81 percent Asian and white. Bayside/Little Neck residents aged 25 and older are more than twice as likely to hold a bachelor’s degree or more (47 percent) as residents of Jamaica/Hollis (23 percent). In Bayside/Little Neck, median household income is 26 percent higher, and median home sale prices for single-family homes are 57 percent higher, than in Jamaica/Hollis. Meanwhile, poverty rates, unemployment rates, and the share of residents who are renters are all higher in Jamaica/Hollis than Bayside/Little Neck. (See Appendix 1, prepared by the Furman Center.)

The divide between the two sets of communities represents a twenty-first century update of the old Black/white paradigm.

The divide between the two sets of communities represents a twenty-first century update of the old Black/white paradigm: in Bayside/Little Neck, 34 percent of residents are white, compared with just 1.4 percent of residents in Jamaica/Hollis, and 55 percent of Jamaica/Hollis residents are Black, compared to just 1.8 percent of residents in Bayside/Little Neck. But Asian Americans also outnumber whites in Bayside/Little Neck, and the Hispanic share of the population is only slightly higher in Jamaica/Hollis than it is in Bayside/Little Neck. (See Table 1.)

Table 1

| BAYSIDE AND JAMAICA: DEMOGRAPHICS, 2021 | ||

| Bayside/Little Neck | Jamaica/Hollis | |

| Percentage with a bachelor’s degree or higher | 47% | 23% |

| Hispanic | 13% | 16% |

| Black | 2% | 55% |

| Asian | 37% | 16% |

| White | 34% | 1% |

| Source: NYU Furman Center. For more details, see Appendix 1. | ||

Many people think the demographic clustering seen in neighborhoods like these happens in a naturally occurring way. In a free market, the thinking goes, some communities simply are more affluent and the housing is more expensive, while others are less affluent and more affordable to live in. American Enterprise Institute fellow Howard Husock, for example, writing recently in City Journal, said economic segregation is a matter of personal preference. “Census data have long indicated that Americans tend to sort by income and educational status, preferring to live with people like them in those respects.”48 Others may think that racial groups tend to cluster because, put simply, birds of a feather flock together. In the case of communities of color, there are valid reasons for people wanting to cluster to protect themselves from discrimination and to find affirming spaces.49

However, evidence suggests that government housing policies drive economic and racial segregation at least as much as consumer preference and the marketplace for homes.50 It is possible to build housing that is affordable, even in wealthy communities that have expensive land values, by building multiple smaller units on a given plot of land. Doing so divides the cost of the land between several parties, and shared walls reduce construction costs per housing unit.

Evidence suggests that government housing policies drive economic and racial segregation at least as much as consumer preference and the marketplace for homes.

But zoning laws in many communities outlaw multifamily housing. These restrictive zoning laws drive economic segregation, as much as personal choice and the market do. An important 2010 study of fifty metropolitan areas found that “a change in permitted zoning from the most restrictive to the least would close 50 percent of the observed gap between the most unequal metropolitan area and the least, in terms of neighborhood inequality.”51

In Bayside/Little Neck, zoning laws are substantially more restrictive than in Jamaica/Hollis. Anything more than a single-family detached home is banned on a majority (57 percent) of Bayside/Little Neck’s residential lots, compared with just 12 percent of lots in Jamaica/Hollis.52 Larger multifamily dwellings are much harder to build in Bayside/Little Neck. Although the two communities are roughly comparable in size geographically, in 2021, just fifty-four units were authorized by new building permits in properties with more than ten units in Bayside/Little Neck, compared with twenty-one times as many units (1,158) in such buildings in Jamaica/Hollis.53 (See Table 2.)

Table 2

| BAYSIDE AND JAMAICA: HOUSING POLICIES, 2021 | ||

| Bayside/Little Neck | Jamaica/Hollis | |

| Percentage of lots where anything other than single-family detached housing is banned | 57% | 12% |

| Number of new unit permits issued (in buildings with 10+ units) | 54 | 1,158 |

| Source: NYU Furman Center (Vicki Been and colleagues). | ||

As Been notes in a short narrative (see Appendix 2), housing in Bayside “consists almost entirely of one- and two-family detached and semi-detached residential development” much of it dating back to the 1930s and 1940s. In 2005, Bayside tightened restrictions because the already low-density community, she says, believed it was not “sufficiently protected against new development that is inconsistent” with the “existing housing context.” Been notes, “Less than 1 percent of the land is zoned for multifamily” (which in New York City means three or more units).

Been’s narrative notes that in some ways, Jamaica, Queens has been moving in the opposite direction, loosening some restrictions to allow greater density. In 2006, a new AirTrain station opened, which connects nearby JFK Airport to the New York City subway line and the Long Island Railroad.54 In 2007, local officials up-zoned areas near the AirTrain station, to allow medium-density multifamily buildings. At the same time, other areas were zoned more restrictively.

As a result, the population density in Jamaica/Hollis in 2020 was about twice as high (26,730 people per square mile) compared to Bayside/Little Neck (13,090 people per square mile). (More details are found in Appendix 1.)

Corresponding Schooling Opportunities in Bayside and Jamaica, Queens

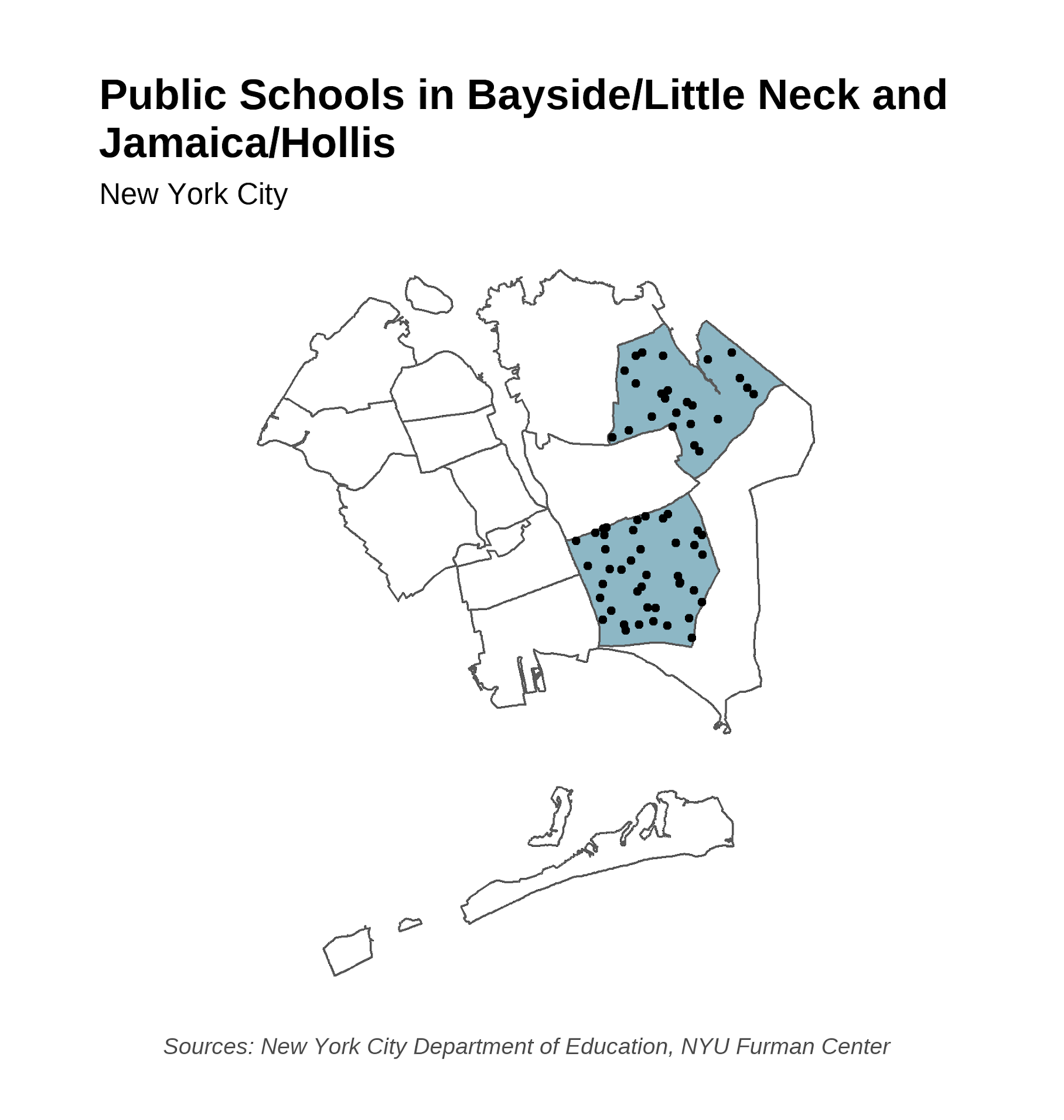

The differing housing policies in Bayside/Little Neck and Jamaica/Hollis have a direct impact on schools. As part of its analysis, the Furman Center examined the demographics and test score results of dozens of public schools (district and charter) located in the two sets of communities. Each school is noted with a dot. (See Figure 3. A full list of the district and charter schools in each community is included in Appendix 3.)

Figure 3

The economic makeup of the public school student populations in the two communities mirrors the economic makeup of the communities, particularly at the elementary- and middle-school levels. More than two-thirds of Jamaica/Hollis students at the elementary level are eligible for subsidized lunch, compared with fewer than half of elementary students in Bayside/Little Neck. (See Appendix 1 for additional data on the economic and racial makeup of the schools in these two communities.)

Academic performance in the two sets of jurisdictions is also starkly different. The most reliable testing data come from 2019, before the COVID-19 pandemic upended participation in standardized testing in New York City public schools. In that year, more than three-quarters of fourth graders in Bayside/Little Neck were proficient or performing at grade level in English, compared with less than half in Jamaica/Hollis. In math, the fourth grade results were even more dramatically different: 83 percent of Bayside/Little Neck students tested proficient in math compared with just 37 percent of students in Jamaica/Hollis, a staggering 46-point gap. In addition, Bayside/Little Neck students had a four-year high school graduation rate that was 18 points higher than in Jamaica/Hollis. (See Table 3.)

Table 3

| BAYSIDE AND JAMAICA: DEMOGRAPHICS AND STUDENT OUTCOMES | ||

| Bayside/Little Neck | Jamaica/Hollis | |

| Percentage of students qualifying for free and reduced-price lunch (elementary level, 2021–22) | 47% | 76% |

| Percentage of students performing at grade level in English (2019) | 77% | 44% |

| Percentage of students performing at grade level in Math (2019) | 83% | 37% |

| Percentage of students who graduated in four years (2019) | 89% | 71% |

| Source: NYU Furman Center (Vicki Been and colleagues). | ||

The Negative Effects of Concentrated Poverty

Some observers may dismiss differences in academic achievement and attainment in Bayside/Little Neck and Jamaica/Hollis as the product of differences in the socioeconomic status of the families that children come from rather than the schools to which they have access. It is very true that the socioeconomic status of families is a powerful predictor of test scores and graduation rates because students with adequate nutrition, housing, and health care have a greater chance of succeeding in school.55

A wide body of research, however, suggests the story is not so simple. Considerable research suggests that students from low-income families like those found in Jamaica/Hollis can do well if given the right school environment, but that concentrations of poverty in schools typically do not provide that supportive environment.56 Housing policies that exclude and concentrate low-income families in certain communities, therefore, contribute to the educational challenges of students in places like Jamaica/Hollis.

It is not inevitable that low-income students will perform at low academic levels. Nationally, low-income students in economically-mixed schools perform considerably better than low-income students in high-poverty schools. On the 2017 National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) given to fourth-graders in math, for example, low-income students attending schools that have the low-income population levels of Bayside/Little Neck (35–50 percent) scored 235 while low-income students in schools with a low-income population level of Jamaica/Hollis (76–99 percent) scored 223.57 This 12-point difference on the NAEP amounts to more than a year’s worth of learning.58

Controlling carefully for students’ family background, another study found that students in mixed-income schools showed 30 percent more growth in test scores over their four years in high school than peers with similar socioeconomic backgrounds in schools with concentrated poverty.59

Opponents of racial and economic integration—including those in Queens—often say that what’s important is not who sits next to whom in class, but making sure that all schools have the resources they need.60 On one level, it is certainly true that all schools should have adequate resources. But when schools are segregated by race and class, research finds, equal resources alone—a “separate but equal” strategy—is usually unsuccessful.

When schools are segregated by race and class, research finds, equal resources alone—a “separate but equal” strategy—is usually unsuccessful.

A rigorous 2010 study in Montgomery County, Maryland schools by Heather Schwartz of the RAND Corporation tested two strategies for improving academic achievement in that diverse community. In the first strategy, the school board invested $2,000 extra per pupil in higher-poverty schools designated as part of the county’s “red zone.” In the second strategy, housing officials employed an “inclusionary zoning” program that required developers to set aside some new units for low-income families and provided that some would become made available for public housing. These new units were spread throughout the county, including in more affluent communities that were designated as being in the “green zone.”

Schwartz examined whether disadvantaged students living in public housing performed better in red zone schools that invested extra funds or green zone schools that did not receive extra funding because they were located in more affluent areas. Importantly, because public housing is scarce, families on a waitlist almost always take whatever unit becomes available, so the study effectively involved random assignment of low-income families and their children.

Schwartz examined the performance of 850 elementary school students living in public housing (72 percent of whom were Black, 16 percent Hispanic, 6 percent Asian, and 6 percent white). She found that over time, economic integration was a far more effective strategy than compensatory spending. In the green zone, disadvantaged students performed much better and cut the math achievement gap with their middle-class peers in half between 2001 and 2007, and by one-third in reading.61 In other words, what the housing authority did for students had a bigger impact than what the school board did. (See Figure 4.)

Figure 4

Neighborhoods (and the public schools that students can attend) have longer-term effects as well on a child’s adult outcomes. In a widely discussed 2015 study, Raj Chetty of Harvard University and his colleagues looked at how children who relocated from higher-poverty to lower-poverty areas through the federal Moving to Opportunity program fared as adults. They found that compared with a control group that wanted to move but could not because of the program’s limited number of spaces, children who moved before age thirteen significantly improved their chances of attending colleges and earned a third more as adults.62 (See Figure 5.) The expected lifetime earnings benefit was estimated at $302,000.63

Figure 5

Why does it matter whether or not children grow up in, and attend schools in, neighborhoods with concentrations of poverty? A wide body of research suggests that the opportunities in mixed-income schools, such as those in Bayside/Little Neck, provide a variety of advantages over higher-poverty schools such as those found in Jamaica/Hollis—including more experienced teachers, a more challenging curriculum, and a set of peer networks that can facilitate economic advancement.

Research from the Education Trust finds that students in high-poverty schools are more likely to be taught by teachers who are ineffective, and by educators with less experience, or who lack certification.64 To make matters worse, the U.S. Government Accountability Office has found that high-poverty schools provide fewer academic offerings for college, such as Advanced Placement (AP) classes. Roughly 70 percent of low-poverty schools offered ten or more Advanced Placement (AP) classes, while only 30 percent of high-poverty schools did so.65

The data from Queens follow these national patterns. In Jamaica/Hollis, teachers are more likely to be inexperienced and new to the profession than in Bayside/Little Neck. As shown in Appendix 3, more than 10 percent of teachers in Jamaica/Hollis are in their first or second year of teaching, compared with 6 percent of teachers in Bayside/Little Neck. The number of AP offerings provided at the high school level are difficult to compare fairly across schools, because some high schools are larger than others. But it is noteworthy that of the eighteen schools with high school offerings in the two jurisdictions, the high school offering the most AP classes (twenty) is located in Bayside/Little Neck.66

Mixed-income schools also offer peer networks that can be very important in life. A 2022 study by Raj Chetty and colleagues of 21 billion friendships among 72.2 million users of Facebook found that having cross-class friendships was strongly related to moving up the economic ladder. In fact, the researchers concluded that in their extensive scholarship, having friends (and more casual acquaintances that constitute “friendships” on Facebook) from more advantaged backgrounds was “the single strongest predictor of upward mobility identified to date”—more powerful than several other factor studied, including the median household income of the family a child grows up in, the degree of racial segregation in a neighborhood, and the share of single-parent households there.67

The Benefits of Diversity

Importantly, while there are benefits to reducing the harms from concentrated poverty in communities such as Jamaica/Hollis, there are also benefits to creating greater diversity in communities such as Bayside/Little Neck, which are majority middle-class. Bayside/Little Neck students already attend schools that are racially diverse in many respects. But because the elementary and middle schools are just 3 percent Black, students there miss out on the educational benefits that can flow from having an even more racially diverse student body.

Researchers find growing evidence that “diversity makes us smarter.” As one set of scholars put it: “Students’ exposure to other students who are different from themselves and the novel ideas and challenges that such exposure brings leads to improved cognitive skills, including critical thinking and problem solving.”68 A classroom discussion of the role of anti-Black racism by police, for example, takes on a very different life when a meaningful number of Black students can talk about their experiences. More broadly, discussions of literature and history are enriched when students bring different frames of reference into the classroom.

Moreover, students can learn better how to navigate adulthood in an increasingly diverse society—a skill that employers value—if they attend diverse schools. Ninety-six percent of major employers say it is “important” that employees be “comfortable working with colleagues, customers, and/or clients from diverse cultural backgrounds.”69 Business leaders have advocated for school integration because, they told teachers, “people have to be able to work together. . . . The number one problem in the workplace is not not knowing your job or not knowing the skills for your job. . . . It is people with skills not being able to get along with coworkers.”70

The research is clear that, when Black students and white students have been integrated, test scores of Black students increased and the scores of white students did not decline.

The research is clear that, when Black students and white students have been integrated, test scores of Black students increased and the scores of white students did not decline.71 In Boston, for example, a cross-district choice program, under which Black students could attend suburban schools, showed positive effects for Black students and no test score decline among white students. The same experience was true in a Texas study.72

Substantial Political Obstacles to Reform in Queens

If research suggests that greater school integration is good for students, that does not make it easy politically. Queens, in particular, has a long history of pushback to integration, from the 1960s to the current day.

If research suggests that greater school integration is good for students, that does not make it easy politically.

In the 1960s, when New York City school officials planned modest steps to integrate schools, white mothers in Queens formed an organization, Parents and Taxpayers (PAT), that grew to 300,000 members citywide and ended up killing New York City’s school integration efforts districtwide. The mothers invoked the concept of “community control” to oppose efforts to provide transportation to students in economically and racially segregated communities to create the possibility of attending high-quality integrated school.73

In the 1970s, a proposal to bring low-income housing to a white middle-class neighborhood in Queens brought national headlines. Residents of politically liberal Forest Hills, Queens, a community that was 97 percent white and two-thirds Jewish, came out in strong opposition to a plan by Mayor John Lindsay to build a low-income housing apartment with 840 units.74 The fight helped accelerate the career of a young Queens attorney, Mario Cuomo, who brokered a compromise to cut the apartment’s size in half. While Mayor Lindsay ascribed opposition purely to racism, Cuomo wrote that “the big difference in Forest Hills was not race, it was class,” for few of the neighbors would object if wealthier Black families moved in.75

But race has also been a big part of the story in Queens. In 1986, Queens made national headlines when white teenagers in the town of Howard Beach attacked three Black men whose car had broken down in the neighborhood. After the men went to a pizza restaurant to call for assistance, a gang of white teens yelled racial epithets and chased one of the Black men, Michael Griffith, into traffic, where he was killed.76 The teens were in essence seeking to enforce segregation by attacking peaceful Black people for having the temerity to appear in the community.

Flash forward to 2019, when Community School District 28 (which includes Jamaica and more affluent parts of Queens, such as Forest Hills) was considering a plan to promote greater integration of the schools. (Bayside is not part of District 28; it is in nearby District 26.)

Efforts to promote diversity in District 28 were part of a larger effort to create less segregated schools by Mayor Bill de Blasio’s chancellor, Richard Carranza. In a July 2018 interview with The Atlantic, Carranza bemoaned the fact that New York schools were among the most segregated in the country. Reflecting on the 1954 Brown v. Board of Education decision, he declared, “We’ve been admiring this issue for 64 years! Let’s stop admiring and let’s start acting.”77 The de Blasio administration created a School Diversity Advisory Group (SDAG), chaired by Maya Wiley and others, to come up with recommendations.78 The group issued reports in February 2019 and August 2019.79 Separately, de Blasio rolled out a proposal in June 2018, to end a system in which admissions to elite public high schools in New York City, such as Stuyvesant and Bronx School of Science, is based solely on performance on the Specialized High School Admissions Test (SHSAT).80

In a July 2018 interview with The Atlantic, Carranza bemoaned the fact that New York schools were among the most segregated in the country.

Meanwhile, local community school districts in New York City were taking action. In Brooklyn, school officials in District 15 adopted a groundbreaking school integration plan in 2018 to break up concentrations of school poverty and provide all students with a chance to attend economically mixed schools.81

But in Queens, when District 28 received a planning grant to promote diversity from the New York City Department of Education, all hell broke loose. Northside parents created an organization, called Queens Parent United, whose mission was “protecting your neighborhood school.”82 They showed up in force at community meetings and expressed outrage at the Department of Education’s efforts to support a planning process for a locally created diversity proposal. Sadye Campoamor, an official with the Department of Education, recalls the fury from parents at one meeting. “It was just speaking to … a roomful of amygdalas,” referring to the part of the brain that feels fear and threat. Parents were “standing up and … spewing, screaming… It was like droplets city.”83

Parents complained about the possibility of long bus rides for their kids to attend subpar schools in Jamaica. Although many of the parents who opposed District 28’s efforts to diversity schools were white, many were also Chinese Americans.84 Some were already angry about de Blasio’s efforts to eliminate the SHSAT for specialized high schools. They saw the test as a path to social mobility for Asian American immigrants who lack connections. Coming on the heels of the SHSAT controversy, Stella Xu, a Chinese immigrant who lives in Forest Hills, told NPR’s School Colors podcast, “by the time the District 28 diversity plan came out, I feel that a lot of people in the Asian community felt that this was just another attack.”85

Unlike some other New York City community districts, District 28 has not adopted a diversity plan.86

The Need for a Two-Pronged Schooling and Housing Strategy

What is to be done to promote more equitable educational opportunities in places like Jamaica/Hollis, and to enhance the benefits of diversity in places like Bayside/Little Neck? Policymakers would be wise to pursue a two-part strategy—continuing to promote efforts to integrate schools through public school choice, and simultaneously pursuing policies that open up housing and schooling opportunities by reducing restrictive zoning.

Pursuing Public School Choice for Integration

Using public school choice and nonselective magnet schools can be a powerful way to reduce economic and racial segregation. In 2020, nationwide, 171 school districts and charter schools considered socioeconomic status in student assignment plans as a way to foster economic and racial diversity.87 Public school choice policies can be implemented quickly, while changes to zoning laws, even when quickly implemented, take longer to bear fruit because it takes time for builders to erect multifamily homes into which parents with children can eventually move.

Using public school choice and nonselective magnet schools can be a powerful way to reduce economic and racial segregation.

In the short term, in New York City, however, chancellor David Banks has decided not to emphasize a school choice strategy. Banks himself is a product of a Black Queens neighborhood and says he personally benefited educationally when his parents insisted that he take a bus to a high-quality integrated school outside of his neighborhood. But Banks now deemphasizes integration as a strategy because he says alongside the educational benefits, there were also costs imposed. He often was made to feel unwelcome in schools located outside his own neighborhood, and he said it was unfair that the burden of getting up early to catch a bus was often placed on Black students like himself.88

Banks’s position is on the one hand understandable, and at the same time regrettable. As Stefan Lallinger has argued, it is true that integration programs have often been poorly implemented—putting the burdens on relatively disadvantaged students to take the long bus rides, and failing to provide an inclusive and supportive environment once students arrived. But school integration strategies today can and should be made more equitable—and they are worth pursuing, because the long run benefits of giving students a chance to attend mixed-income schools are profound.89

That’s why many striving Black families in Southeast Queens, like Banks’s, took the risk to send their children to schools outside their neighborhood, because they fully recognize the negative effects of concentrated poverty. Opting out of high-poverty schools is a well-worn strategy employed by relatively advantaged Black families in Queens, observers note. Among the Black political class, says Venus Ketcham, a Black teachers’ aide who lives in South Jamaica, “A lot of their children went to private school. A lot of their children were bused to District 26,” which is where Bayside is located.90

Why rely solely on transporting students when it is also possible to remove barriers to families who wish to move?

New York City has a robust system of public school choice at the high school level, and the data from the Furman Center suggest that the Black student population in Bayside/Little Neck currently rises from 3 percent at the elementary and middle school level to 11 percent at the high school level, which represents important progress. (See Appendix 1.) But Banks’s objections about the way integration has often been pursued also raise an important criticism and point to the need for a second policy approach: getting at underlying issues of housing opportunity. Put simply, why rely solely on transporting students when it is also possible to remove barriers to families who wish to move?

Pursuing a Parallel Housing Strategy of Bringing Down Exclusionary Barriers

At the end of the day, it is housing policies that are a root cause of economic and racial school segregation.91 Public school choice policies—while positive and necessary—are mostly aimed at addressing an underlying housing problem. Residential segregation, not gerrymandered school boundary lines, is the fundamental driver of school segregation. Indeed, recent research found that if students were all assigned to the very closest school, racial school segregation would actually be 5 percent worse than it is today. Given that school boundary lines on average have a small ameliorative effect, one researcher concluded that in allocating responsibility for school segregation between housing and school attendance boundaries, the evidence suggests “residential segregation alone explains more than 100 percent of school segregation in the U.S.”92 In other words, in the communities studied, housing segregation was, on average, entirely to blame for school segregation.

Which brings us back to the importance of housing reforms that are being championed in New York State and New York City: efforts of the New York City mayor and council to reduce exclusionary zoning; and efforts of Governor Hochul to promote statewide reform.

As noted above, under Hochul’s proposal, every New York City-area community, including places like Bayside, would be required to permit new housing, to increase supply by 3 percent over three years in order to bring down prices. According to a recent analysis by the Furman Center, in the past, District 11 (including Bayside) would not have met the 3 percent growth target, but District 12 (including Jamaica) would have. In the 2014–16 and the 2017–19 period, District 11 grew by less than 3 percent each period, while District 12 grew more than 3 percent during each of these two periods.93 Hochul’s plan to provide extra credit for communities that make room for affordable housing (as opposed to merely increasing housing supply of any kind) is another reason that the proposal could lead to greater economic and racial integration of the public schools.

Housing reform that opens up communities to multifamily housing and creates the possibility of more economically and racially integrated neighborhood schools also obviates one of the key political obstacles to school integration: the necessity of transportation (“busing” in the language of opponents). A 2021 study found that longer commutes significantly weaken support for school integration. Americans support racially diverse schools in principle by two to one, but by two to one also oppose creating such schools when it requires that students be transported farther away than their current schools.94 Housing reforms that promote integration of neighborhood schools also address some of Chancellor Banks’s concerns that when outside students are bused in, they are more likely to be made to feel unwelcome, and that the burden of transportation should not fall on disadvantaged students.

Americans support racially diverse schools in principle by two to one, but by two to one also oppose creating such schools when it requires that students be transported farther away than their current schools.

There are other advantages to policies that allow disadvantaged students to not only attend an integrated school but also live in an integrated neighborhood. Heather Schwartz’s study in Montgomery County Maryland schools found two-thirds of the benefits of integration came from schooling, but an additional one-third of the benefit came from students living in a more advantaged neighborhood.

In short, school integration is a powerful strategy that school officials should pursue, but it would be a terrible mistake to ignore the ways in which housing policies can be reformed as well. We should begin to tear down the government-sponsored walls that keep children and their families in separate and unequal environments, and New York’s housing reform efforts represent an important place to start.

Appendixes

Notes

- Nationally, 73 percent of public school students attend an assigned school. “Fast Facts: Public school choice programs,” National Center for Education Statistics, https://nces.ed.gov/fastfacts/display.asp?id=6. In some places, such as New York City, the percentage of students attending assigned schools is lower. In 2016–17, 60 percent of New York City public school kindergarten students attended their zoned schools. See Nicole Mader, Clara Hemphill, and Qasim Abbas, Taina Guarda, Ana Carla Sant’anna Costa, and Melanie Quiroz, “The Paradox of Choice: How School Choice Divides New York City Elementary Schools,” The New School Center for New York City Affairs, 2018, http://www.centernyc.org/the-paradox-of-choice/.

- Mara Gay, “The Era of Shutting Others Out of New York’s Suburbs Is Ending,” New York Times, February 21, 2023, https://www.nytimes.com/2023/02/21/opinion/housing-new-york-city.html.

- Governor Kathy Hochul, “Remarks as Prepared: Governor Hochul Delivers 2023 State of the State,” January 10, 2023, https://www.governor.ny.gov/news/remarks-prepared-governor-hochul-delivers-2023-state-state.

- Janaki Chadha, “Hochul faces an ‘uprising’ over her plan to build new housing in NYC suburbs,” Politico, February 11, 2023, https://www.politico.com/news/2023/02/11/hochul-faces-uprising-housing-plan-00080949.

- Governor Kathy Hochul, “Governor Hochul Announces Statewide Strategy to Address New York’s Housing Crisis and Build 800,000 New Homes,” January 10, 2023, https://www.governor.ny.gov/news/governor-hochul-announces-statewide-strategy-address-new-yorks-housing-crisis-and-build-800000; and Governor Kathy Hochul, “Remarks as Prepared: Governor Hochul Delivers 2023 State of the State,” January 10, 2023, https://www.governor.ny.gov/news/remarks-prepared-governor-hochul-delivers-2023-state-state.

- Henry Grabar, “New York Has a YIMBY Governor,” Slate, January 11, 2023, https://slate.com/business/2023/01/kathy-hochul-housing-new-york-zoning.html.

- New York State Senate, Senate Bill S668, https://www.nysenate.gov/legislation/bills/2023/s668.

- See “Mayor Adams Unveils ‘Get Stuff Built,’ Bold Three-Pronged Strategy to Tackle Affordable Housing Crisis, Sets ‘Moonshot’ Goal of 500,000 New Homes,” New York City, December 8, 2022, https://www.nyc.gov/office-of-the-mayor/news/893-22/mayor-adams-get-stuff-built-bold-three-pronged-strategy-tackle-affordable-housing#/0.

- “City of Yes: Housing Opportunity,” New York City Department of City Planning, https://www.nyc.gov/site/planning/plans/city-of-yes/city-of-yes-housing-opportunity.page.

- Adrienne E. Adams, “A Housing Agenda to Confront the City’s Crisis,” New York City Council, http://council.nyc.gov/wp-content/uploads/2022/12/121422.OC28.Speaker-Adams-ReportLS8.5x11_v4.pdf; and “Adrienne E. Adams,” New York City Council, https://council.nyc.gov/district-28/.

- “Making New York Work for Everyone,” New New York Panel, December 2022, https://edc.nyc/sites/default/files/2022-12/New-NY-Action-Plan-Making_New_York_Work_for_Everyone.pdf; and Mihir Zaveri, “N.Y.C. Boards Usually Oppose New Housing. Not This One,” New York Times, December 15, 2022, https://www.nytimes.com/2022/12/15/nyregion/manhattan-community-board-housing.html.

- “Pro-homes Advocacy Groups Across New York State Form ‘New York Neighbors’ Coalition,” Regional Planning Association, January 29, 2023, https://rpa.org/latest/news-release/new-york-neighbors.

- YIMBY is a new movement that seeks to counter NIMBYs by pushing for more housing and less restrictive and exclusionary zoning laws. Janaki Chadha, “Hochul faces an ‘uprising’ over her plan to build new housing in NYC suburbs,” Politico, February 11, 2023, https://www.politico.com/news/2023/02/11/hochul-faces-uprising-housing-plan-00080949.

- Daniel Marans, “Why Rival Sides in the Housing Crisis Plaguing Major U.S. Cities Are Considering Peace,” HuffPost, February 6, 2023, https://www.huffpost.com/entry/yimby-leftist-peace-affordable-housing-fight_n_63ded746e4b0c2b49ae35781.

- Janaki Chadha, “Hochul faces an ‘uprising’ over her plan to build new housing in NYC suburbs,” Politico, February 11, 2023, https://www.politico.com/news/2023/02/11/hochul-faces-uprising-housing-plan-00080949.

- Janaki Chadha, “Hochul faces an ‘uprising’ over her plan to build new housing in NYC suburbs,” Politico, February 11, 2023, https://www.politico.com/news/2023/02/11/hochul-faces-uprising-housing-plan-00080949.

- Henry Grabar, “New York Has a YIMBY Governor,” Slate, January 11, 2023, https://slate.com/business/2023/01/kathy-hochul-housing-new-york-zoning.html.

- David Brand and Jon Campbell, “Gov. Hochul’s ambitious housing plan meets suburban blockade,” Gothamist, January 30, 2023, https://gothamist.com/news/gov-hochuls-ambitious-housing-plan-meets-suburban-blockade.

- Michael Andersen, “Eight Ingredients for State-Level Zoning Reform,” Sightline Institute, August 12, 2021, https://www.sightline.org/2021/08/13/eight-ingredients-for-a-state-level-zoning-reform/.

- Michael Andersen, “Five Lessons from California’s Big Zoning Reform,” Sightline Institute, August 26, 2021, https://www.sightline.org/2021/08/26/four-lessons-from-californias-big-zoning-reform/.

- “Final FY23 Spending Bill: Advocates and Key Congressional Champions Secure Increased Funding for HUD Programs,” National Low Income Housing Coalition, December 20, 2022, https://nlihc.org/resource/final-fy23-spending-bill-advocates-and-key-congressional-champions-secure-increased.

- Anna Fahey, “Poll: Washington Voters Out Ahead of Local Leaders on Zoning Reforms,” Sightline Institute, February 15, 2023, https://www.sightline.org/2023/02/15/poll-washington-voters-out-ahead-of-local-leaders-on-zoning-reforms/; and David Gutman, “Is this the year WA ends single- family zoning?” Seattle Times, February 24, 2023, https://www.seattletimes.com/seattle-news/politics/is-this-the-year-wa-ends-single-family-zoning/ (noting Housing Appropriations Committee 25-5 vote to pass HB1110, which would legalize duplexes and other missing middle housing throughout the state).

- See “NY Statewide Housing Survey,” Slingshot Strategies, February 23–25, 2023, https://drive.google.com/file/d/1IY-7cuRVdPaRoBH-YsodXAlC15zPTYaq/view; “New Poll Shows Overwhelming Support for New York Housing Compact and Increased Housing Supply Across New York,” Open New York, March 1, 2023, https://docs.google.com/document/d/146yw2-Pmc4B_86O6otASrFaMg5Hwe7jWJdvUvBnVvP4/edit; and Anna Gronewold, Sally Goldenberg, and Zachary Schermele, “New poll unpacks Hochul’s suburban housing push,” Politico, March 1, 2023, https://www.politico.com/newsletters/new-york-playbook/2023/03/01/new-poll-unpacks-hochuls-suburban-housing-push-00084937.

- Kevin Hanley, “Voters Support Transit-Oriented Development in New York State,” Data for Progress, March 6, 2023, https://www.dataforprogress.org/blog/2023/2/24/voters-support-transit-oriented-development-in-new-york-state-et27x.

- “New Poll Shows Overwhelming Support for New York Housing Compact and Increased Housing Supply Across New York,” Open New York, March 1, 2023, https://docs.google.com/document/d/146yw2-Pmc4B_86O6otASrFaMg5Hwe7jWJdvUvBnVvP4/edit.

- “Fast Facts about NYC Housing” New York City Mayor’s Office to Protect Tenants, https://www.nyc.gov/content/tenantprotection/pages/fast-facts-about-housing-in-nyc.

- Jimmy Vielkind, “Crime, Housing Top Hochul’s Priorities,” Wall Street Journal, https://www.wsj.com/articles/new-york-gov-kathy-hochul-says-her-focus-on-crime-and-housingwith-less-brashness-in-albany-11672849242.

- Hochul, “2023 State of the State.”

- Howard Husock, “How New York City’s affordable housing problem can be solved,” New York Post, December 24, 2022. https://nypost.com/2022/12/24/how-to-solve-new-york-citys-affordable-housing-problem/

- Hochul, “2023 State of the State.”

- Noah Kazis, “Ending Exclusionary Zoning in New York City’s Suburbs,” Furman Center, New York University, November 9, 2020, 4, https://furmancenter.org/files/Ending_Exclusionary_Zoning_in_New_York_Citys_Suburbs.pdf.

- Hochul, “2023 State of the State.”

- Gay, “The Era of Shutting Others Out of New York’s Suburbs Is Ending,” New York Times, February 21, 2023, https://www.nytimes.com/2023/02/21/opinion/housing-new-york-city.html (citing data from the Citizens Budget Commission).

- Husock, “How New York City’s affordable housing problem can be solved.”

- Troy Closson and Nicole Hong, “Why Black Families Are Leaving New York, and What It Means for the City,” New York Times, January 31, 2023. https://www.nytimes.com/2023/01/31/nyregion/black-residents-nyc.html

- Vielkind, “Crime, Housing Top Hochul’s Priorities.”

- “New Poll Shows Overwhelming Support for New York Housing Compact and Increased Housing Supply Across New York,” Open New York, March 1, 2023, https://docs.google.com/document/d/146yw2-Pmc4B_86O6otASrFaMg5Hwe7jWJdvUvBnVvP4/edit.

- Richard D. Kahlenberg, “How Minneapolis Ended Single-Family Zoning,” The Century Foundation, October 24, 2019, https://tcf.org/content/report/minneapolis-ended-single-family-zoning/.

- “School Choice in the United States: 2019,” National Center for Education Statistics, https://nces.ed.gov/programs/schoolchoice/ind_01.asp (69 percent of American students attended assigned public schools, 19 percent public schools of choice, 9 percent private schools, and 3 percent are home schooled).

- See Jason Sorens, ”The New Hampshire Statewide Housing Poll and Survey Experiments: Lessons for Advocates,” Center for Ethics in Business and Governance, Saint Anselm College, January 1, 2021, 11–12, https://www.anselm.edu/sites/default/files/CEBG/20843-CEBG-IssueBrief-P2.pdf.

- Lauren Wagner, “New Poll Finds Majority of Parents & Voters Favor Open School Enrollment, Elimination of Attendance Boundaries,” The 74, January 23, 2023, https://www.the74million.org/article/new-poll-finds-majority-of-parents-voters-favor-open-school-enrollment-elimination-of-attendance-boundaries/.

- Kazis, Ending Exclusionary Zoning in New York City’s Suburbs, 49.

- “School Colors Episode 1: ‘There is No Plan,’” National Public Radio, May 4, 2022, https://www.npr.org/transcripts/1096469394.

- “School Colors Episode 5: The Melting Pot,” National Public Radio, June 3, 2022, https://www.npr.org/transcripts/1102775262.

- See “Community District Profiles,” New York City Department of City Planning, https://communityprofiles.planning.nyc.gov/.

- See “Queens Community District 12,” New York City Department of City Planning https://communityprofiles.planning.nyc.gov/queens/12 (mean commute to work of 48.6 minutes); and “Queens Community District 11,” New York City Department of City Planning, https://communityprofiles.planning.nyc.gov/queens/11 (mean commute to work of 44.3 minutes).

- “School Colors Episode 4: The Mason-Dixon Line,” National Public Radio, May 27, 2022, https://www.npr.org/transcripts/1101618668 (referring to Hillsdale Avenue as the Mason-Dixon Line which divides North and South portions of Public School District 28). See also Christina Veiga, “The ‘School Colors’ podcast is back, exploring why a Queens diversity plan triggered backlash,” Chalkbeat, May 13, 2022, https://ny.chalkbeat.org/2022/5/13/23071666/school-colors-podcast-district-28-queens-mark-winston-griffith-max-freedman.

- Howard Husock, “Let Housing Markets Work,” City Journal, February 3, 2023, https://www.aei.org/op-eds/let-housing-markets-work/.

- Stefan Lallinger, “Is the Fight for School Integration Still Worthwhile for African Americans?” The Century Foundation, January 17, 2023, https://tcf.org/content/report/is-the-fight-for-school-integration-still-worthwhile-for-african-americans/.

- Jonathan Rothwell and Douglas Massey, “Density Zoning and Class Segregation in U.S. Metropolitan Areas,” Social Science Quarterly 91, no. 5 (December 2010): 1123–43, http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3632084/.

- Jonathan Rothwell and Douglas Massey, “Density Zoning and Class Segregation in U.S. Metropolitan Areas,” Social Science Quarterly 91, no. 5 (December 2010): 1123–43, http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3632084/.

- In New York City, R1 and R2 zoning is limited to single-family detached homes. See “Residential Districts: R2-R2A-R2X,” New York City Department of City Planning, https://www.nyc.gov/site/planning/zoning/districts-tools/r2.page.

- See “Queens Community District 12,” New York City Department of City Planning, https://communityprofiles.planning.nyc.gov/queens/12 (9.6 square miles); and “Queens Community District 11,” New York City Department of City Planning, https://communityprofiles.planning.nyc.gov/queens/11, (9.4 square miles).

- “AirTrain JFK,” John F. Kennedy International Airport, https://www.jfkairport.com/to-from-airport/air-train.

- See, e.g., Richard Rothstein, Class and Schools: Using Social, Economic and Educational Reform to Close the Black-White Achievement Gap (Washington, D.C.: Economic Policy Institute, 2004).

- See, e.g., Richard D. Kahlenberg, All Together Now: Creating Middle-Class Schools through Public School Choice (Washington D.C.: Brookings Press, 2001); and Richard D. Kahlenberg (ed.), The Future of School Integration: Socioeconomic Diversity as an Education Reform Strategy (New York: Century Foundation Press, 2012).

- See Richard D. Kahlenberg, Halley Potter, and Kimberly Quick, “A Bold Agenda for School Integration,” The Century Foundation, April 8, 2019, Figure 1, https://tcf.org/content/report/bold-agenda-school-integration/.

- C. Lubienski and S. T. Lubienski, “Charter, private, public schools and academic achievement: New evidence from NAEP mathematics data,” National Center for the Study of Privatization in Education, Teachers College, Columbia University, January 2006 (rule of thumb that 10 NAEP points equates to roughly a year in learning).

- G. Palardy, “Differential school effects among low, middle, and high social class composition schools,” School Effectiveness and School Improvement 19, no. 1 (2008): 37.

- “School Colors Episode 6: Below Liberty,” National Public Radio, June 17, 2022, https://www.npr.org/transcripts/1105664098.

- Heather Schwartz, “Housing Policy Is School Policy: Economically Integrative Housing Promotes Academic Success in Montgomery County, Maryland,” The Century Foundation, 2010, https://tcf.org/content/commentary/housing-policy-is-school-policy/.

- Raj Chetty, Nathaniel Hendren, and Lawrence F. Katz, “The Effects of Exposure to Better Neighborhoods on Children: New Evidence from the Moving to Opportunity Experiment,” National Bureau of Economic Research, Working Paper no. 21156, May 2015, 2–3, www.nber.org/papers /w21156.

- Raj Chetty, Nathaniel Hendren, and Lawrence Katz, “The Effects of Exposure to Better Neighborhoods on Children: New Evidence from the Moving to Opportunity Experiment,” American Economic Review 106, no. 4 (2016): 855–902, https://opportunityinsights.org/paper/newmto/.

- “Fact Sheet- Teacher Equity,” The Education Trust, https://edtrust.org/wp-content/uploads/Ed%20Trust%20Facts%20on%20Teacher%20Equity.pdf.

- “Public High Schools with More Students in Poverty and Smaller Schools Provide Fewer Academic Offerings to Prepare for College,“ U.S. Government Accountability Office, October 2018, 16, Figure 5, https://www.gao.gov/assets/gao-19-8.pdf.

- Thanks to Lara Adekeye, who used information from the U.S. Department of Education’s Civil Rights Data Collection (https://ocrdata.ed.gov/) to compile teacher experience levels and AP offerings at each of the schools located in Bayside/Little Neck and Jamaica/Hollis.

- Raj Chetty, Matthew O. Jackson, Theresa Kuchler, and Johannes Stoebel, Abigail Hiller, Sarah Oppenheimer, and Opportunity Insights Team, “Social Capital and Economic Mobility,” Opportunity Insights, August 2022, https://opportunityinsights.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/07 /socialcapital_nontech.pdf.

- Amy Stuart Wells, Lauren Fox, and Diana Cordova-Cobo, “How Racially Diverse Schools and Classrooms Can Benefit All Students,” The Century Foundation, February 9, 2016, https://tcf.org/content/report/how-racially-diverse-schools-and-classrooms-can-benefit-all-students/.

- Wells, Fox, and Cordova-Cobo, “How Racially Diverse Schools.”

- Kahlenberg, All Together Now, 235.

- Robert Crain and Rita Mahard, Desegregation and Black Achievement (Santa Monica, CA: Rand Corporation, 1977); and David Armor, Forced Justice: School Desegregation and the Law (New York: Oxford University Press, 1995).

- See Matt Barnum, “Did Busing for School Desegregation Succeed? Here’s What Research Says,” Chalkbeat, July 1, 2019, https://tinyurl.com/y4u4wvb7.

- See e.g. Jerald E. Podair, The Strike that Changed New York: Blacks, Whites and the Ocean-Hill Brownsville Crisis (New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 2002), 22-30; Michael E. Staub, “Death at an Early Age,” The Nation, February 17, 2003, 42; and Richard D. Kahlenberg, Tough Liberal: Albert Shanker and the Battles Over Schools, Unions, Race and Democracy (New York: Columbia University Press, 2007), 86.

- “School Colors Episode 3: The Battle of Forest Hills,” National Public Radio, May 20, 2022, https://www.npr.org/transcripts/1100253582.

- Mario Cuomo, Forest Hills Diary: The Crisis of Low-Income Housing (New York: Vintage, 1983), vii, 117–18. See also Richard D. Kahlenberg, The Remedy: Class, Race and Affirmative Action (New York: Basic Books, 1996), 204.

- “This Day in History: December 20, 1986: Man chased to his death in Howard Beach hate crime,” History, https://www.history.com/this-day-in-history/man-chased-to-his-death-in-howard-beach-hate-crime.

- Adam Harris, “Can Richard Carranza Integrate the Most Segregated School System in the Country?” The Atlantic, July 23, 2018, https://www.theatlantic.com/education/archive/2018/07/richard-carranza-segregation-new-york-city-schools/564299/.

- “School Diversity Advisory Group,” New York City Department of Education, https://www.schools.nyc.gov/about-us/vision-and-mission/diversity-in-our-schools/school-diversity-advisory-group. The author was a member of the Executive Committee of the SDAG.

- See Valerie Strauss, “New York City should set ambitious diversity goals for public schools: New report by panel commissioned by mayor,” Washington Post, February 12, 2019, https://www.washingtonpost.com/education/2019/02/12/new-york-city-should-set-ambitious-diversity-goals-public-schools-new-report-by-panel-commissioned-by-mayor/; and Valerie Strauss, “NYC school diversity panel recommends ending gifted programs in public schools. One member explains the surprising decision,” Washington Post, August 27, 2019, https://www.washingtonpost.com/education/2019/08/27/nyc-school-diversity-panel-recommends-ending-gifted-programs-public-schools-one-member-explains-surprising-decision/.

- “School Colors Episode 8: The Only Way Out,” National Public Radio, July 1, 2022, https://www.npr.org/transcripts/1109160606.

- Eliza Shapiro, “De Blasio Acts on School Integration, but Others Lead Charge,” New York Times, September 20, 2018, https://www.nytimes.com/2018/09/20/nyregion/de-blasio-school-integration-diversity-district-15.html.

- School Colors Episode 7: The Sleeping Giant,” National Public Radio, June 24, 2022, https://www.npr.org/transcripts/1107210138.

- “School Colors Episode 1: ‘There is No Plan,’” National Public Radio, May 4, 2022, https://www.npr.org/transcripts/1096469394.

- “School Colors Episode 8: The Only Way Out,” National Public Radio, July 1, 2022, https://www.npr.org/transcripts/1109160606.

- “School Colors Episode 8: The Only Way Out,” National Public Radio, July 1, 2022, https://www.npr.org/transcripts/1109160606.

- “School Colors Episode 9: Water Under the Bridge,” National Public Radio, July 15, 2022, https://www.npr.org/transcripts/1111624644. See also Christina Veiga, “A push to integrate Queens schools has ripped open a fight about race, resources, and school performance,” Chalkbeat, January 13, 2020, https://ny.chalkbeat.org/2020/1/13/21121720/a-push-to-integrate-queens-schools-has-ripped-open-a-fight-about-race-resources-and-school-performan.

- Halley Potter and Michelle Burris, “Here is What School Integration Looks Like Today,” The Century Foundation, December 2, 2020, https://tcf.org/content/report/school-integration-america-looks-like-today/.

- Laura Meckler, “NYC’s Black schools chief isn’t sure racial integration is the answer,” Washington Post, November 12, 2022, https://www.washingtonpost.com/education/2022/11/17/david-banks-nyc-chancellor-race-equity-merit/.

- Stefan Lallinger, “Is the Fight for School Integration Still Worthwhile for African Americans?” The Century Foundation, January 17, 2023, https://tcf.org/content/report/is-the-fight-for-school-integration-still-worthwhile-for-african-americans/.

- School Colors Episode 9: Water Under the Bridge,” National Public Radio, July 15, 2022, https://www.npr.org/transcripts/1111624644.

- Having said that, housing is not the only root cause of school segregation. In some cases, neighborhoods have become more economically and racially integrated, but white and wealthier parents sometimes choose not to send their children to the local public schools. In New York City, for example, a 2019 report found that “The traditional public elementary schools in racially/ethnically diverse neighborhoods did not necessarily exhibit that same diversity. This divergence was especially pronounced in diverse neighborhoods that included white residents.” See “The Diversity of New York City’s Neighborhoods and Schools,” NYU Furman Center, 2019, 2, https://furmancenter.org/files/sotc/2018_SOC_Focus_Web_Copy_Final.pdf.

- Tomas E. Monarrez, “School Attendance Boundaries and the Segregation of Public Schools in the U.S.,” American Economic Journal (forthcoming), https://www.aeaweb.org/articles?id=10.1257/app.20200498.

- “The Stoop—Policy Breakfast: The proposed New York Housing Compact,” New York University Furman Center, February 17, 2023, https://furmancenter.org/thestoop/entry/policy-breakfast-the-new-york-housing-compact.

- These data are for those without a child under eighteen. For those with children under eighteen, the generic support is 42–27 percent for racially diverse schools, but that turns to 25 percent support and 33 percent opposition if the racially diverse school is farther away. See Halley Potter, Stefan Lallinger, Michelle Burris, Richard D. Kahlenberg, Alex Edwards, and Topos Partnership, “School Integration Is Popular. We Can Make It More So,” The Century Foundation, June 3, 2021, Figure 5, https://tcf.org/content/commentary /school-integration-is-popular-we-can-make-it-more-so/.