How can states address the high price of housing and high levels of economic and racial residential segregation (and the accompanying harms to educational opportunity) when many homeowners with political power don’t want the system to change? Many states are wrestling with this challenge, and while New York’s recent failed attempt to bring about reform is discouraging , successful reforms in other states such as California (as well as in certain cities) suggest a possible path forward.

The attempt to reform housing in New York was bold. In January 2023, Governor Kathy Hochul sought to address the state’s housing affordability crisis by proposing the New York Housing Compact to build 800,000 new homes over the next decade. Under the compact, municipalities would have been given the goal of increasing their housing supply by 3 percent every three years (if they were located downstate) and by 1 percent every three years (if they were located upstate). If communities failed to reach their goals, the state would require municipalities to provide applicants for housing permits with a fast-track approval process. In addition, downstate areas would need to rezone for greater housing within a half mile of commuter railway and subway stations.1

Governor Hochul’s housing plan was slated to be “the most consequential” reform in decades, a “potential centerpiece for her first term,” the New York Times reported. But in a “spectacular failure,” a Democratically controlled legislature ended up killing the Democratic governor’s proposal.2

In pushing zoning reform, Hochul faced a tough dilemma. Much of the strongest opposition came from reliably liberal constituencies in suburban Westchester, where Democrats supported Joe Biden over Donald Trump by 68 percent to 31 percent, as well as from Long Island, which supported Biden over Trump more narrowly.3 Moving forward, Hochul and other housing reformers in New York clearly cannot rely on party loyalty or ideological affinity to ensure success.

The good news is that in recent years several states and cities have managed to overcome political opposition from entrenched forces to bring about important zoning reforms. What sort of political coalitions have been assembled in other states and localities to bring about change on housing and zoning? What organizing tactics proved effective? What are the common pitfalls to avoid? And can these lessons apply to the particular set of political dynamics found in New York?

This report examines the reform efforts in the state of California.4 It is the first in a series of four such reports, which will also include examinations of successful changes to exclusionary zoning laws in Oregon, Minneapolis, and Charlotte. In addition, The Century Foundation will be publishing two reports on messaging research for reform grounded specifically in conditions found in New York State. These six reports on reform are meant to complement four previously published Century Foundation reports that explain how exclusionary zoning laws are harmful to educational opportunities by examining local jurisdictions in Queens, Long Island, Westchester County, and the Buffalo region.5

The recent housing reform efforts in California is a particularly instructive case. The fight for change was not easy, and the legislature’s efforts to reform zoning largely came up short in 2018, 2019, and 2020.6 But in 2021, the state legislature passed a law that essentially legalized statewide the construction of up to four homes on lots that had been previously zoned as single-family lots. This legislation was part of a larger package of housing reforms.7

The significance of reforms such as this is not just for housing; it is also for education. Because roughly three-quarters of American school children attend public schools in their residential communities, housing policies that shape where people can live also implicate where children can attend schools.8 In that sense, housing policy is school policy.

This report proceeds in four parts. The first part examines the early efforts at reform in California, which included some important missteps and did not end up producing significant legislative success. The second part examines California’s successful 2021 reform. Because some of the stiffest opposition to change came from liberal Democrats representing wealthy areas, reform proponents did not rely on party loyalty or ideological affinity to pass the legislation and instead formed a cross-party multiracial coalition that fell along class lines. The third part examines some of the early effects of housing reform in California and elsewhere on housing production and housing prices. And the fourth part considers implications for zoning reform in New York.

California’s Initial Failures to Reform Zoning (2018–20)

Housing prices have been a problem in California for many years, and efforts to reform housing policies date back several legislative sessions. In 2016, for example, California first passed modest legislation to require communities to allow accessory dwelling units (ADUs), sometimes known as granny flats.9 But to meet the state’s housing challenge, legislators had bigger reforms in mind. In 2018, California state senator Scott Wiener, a San Francisco Democrat, drafted SB 827 to eliminate zoning restrictions for developers who wish to build apartments up to eighty-five feet tall (about eight stories) within a half mile of train stations and a quarter mile of high-frequency bus stops.10

The bill had a lot going for it. In California, the unaffordability of housing was legendary. Silicon Valley employers were having trouble attracting employees, given the price of homes. According to a 2016 McKinsey Institute report, California needed to build 2 million units to meet existing demand, and a total of 3.5 million units to meet expected growth in demand between 2016 and 2025. McKinsey further found if local governments rezoned areas within half a mile of transit stops, there would be room for California to potentially build an estimated 1.2 to three million new housing units by 2025.11

By focusing on development near transit, Wiener was seeking to merge the affordability and environmental concerns—so pressing for many Californians—in the service of curtailing exclusionary zoning. (Building near transit reduces the need for reliance on automobiles.) The bill received extravagant praise from some corners. For example, Boston Globe columnist Dante Ramos said SB 827 “may be the biggest environmental boon, the best job creator, and the greatest strike against inequality that anyone’s proposed in the United States in decades.”12

Wiener knew that rich suburbs such as Beverly Hills that employed restrictive zoning would oppose reform. But in early 2018, a number of community groups and urban city councils also came out in opposition. By focusing on communities close to transit—rather than wealthy communities that were exclusionary—the bill’s authors unwittingly united wealthy and low-income communities that did not want to see development.13

Some progressive social activists worried that new development alongside transit stops could accelerate the displacement that can come with gentrification.14 In February 2018, thirty-seven housing and tenant advocacy groups came out in opposition to SB 827, in part because its focus was market-based housing, not publicly subsidized homes.15

In March of 2018, Los Angeles mayor Eric Garcetti and the Los Angeles City Council came out in unanimous opposition to the legislation, arguing that many of the city’s neighborhoods of single-family homes would lose their character if the bill were enacted.16 (The bill would have affected almost 50 percent of single-family homes in Los Angeles.)17 The opposition would ultimately prove lethal. One local housing advocate noted, “The California Legislature is not going to pass a land use bill unanimously opposed by the Los Angeles City Council and the city’s mayor.”18

Pro-housing “Yes in My Back Yard” (YIMBY) advocates also made mistakes. YIMBYs in California were mostly highly educated white people. As reform efforts stalled, they grew frustrated and some acted obnoxiously. In early April 2018, at a YIMBY rally in San Francisco, supporters shouted down protesters of color, lecturing them to “read the bill.”19 The legislation ultimately died on a 7–4 committee vote on April 17, 2018.20 Boston University researchers Katherine Levine Einstein, David M. Glick, and Maxwell Palmer note that a “fissure between relatively advantaged YIMBYs and affordable housing advocates was a key factor in the demise of SB 827.”21

Legislators regrouped, and pushed for reform again in 2019 and 2020, but were largely unsuccessful.22

California’s Enactment of Zoning Reform (2021)

In September 2021, after several failed efforts, legislation with a different approach was passed and signed into law. Rather than focusing on building large numbers of apartment buildings near transportation, the new legislation focused on “missing middle” housing and a more modest number of homes near transit hubs.23

The centerpiece was SB 9, the California Housing Opportunity and More Efficiency (HOME) Act. The law legalized duplexes statewide and allowed people to subdivide lots, which could mean as many as four homes on what had previously been zoned a single-family lot.24 The law “has opened up entire communities that had been largely walled off,” said Ben Metcalf of the University of California at Berkeley’s Turner Center.25 A companion piece of legislation, SB 10, also passed, requiring localities to allow buildings with up to ten units near transit, a more modest version of the original Scott Wiener legislation.26 The legislation was signed by Governor Gavin Newsom over the objections of more than 260 city leaders.27

How did the legislation become law? Progressive supporters of reform recognized that they needed to create a different type of political coalition than typically is employed to pass liberal legislation. As in New York, pro-housing forces in California could not rely on ideological or party loyalty. Research found that within California cities, some of the most liberal areas had the worst forms of exclusionary zoning.28 Consider, for example, liberal Palo Alto, home to Stanford University. In November 2013, the city council voted to relax its zoning to increase density and allow a sixty-unit affordable housing complex for elderly people. An outcry ensued and voters passed “Measure D” by 56 percent to 44 percent, voting to reverse the decision and forbid the construction of anything other than single-family homes.29 A California YIMBY activist notes that progressives are rightfully proud of their openness to immigrants, so why, he asks, are some standing by exclusionary zoning that says “we welcome outsiders—but you’ve got to have a $2 million entrance fee to live here”?30

Senator Wiener noticed that in California, fights over exclusionary zoning were divided not by Democrat versus Republican but by rich versus poor. Some left-wing Democrats and right-leaning Republicans supported efforts to reform exclusionary zoning, he says, and some of each group have been opposed, he said.31 In debates, opponents of reform typically cite many concerns, related to increased traffic, school overcrowding, or crime.32 But Wiener also said opponents of reform in California had one thing in common—they represented wealthier constituents who “wanted to keep certain people out of their community.”33 Supporters of reform, he said, by contrast, wanted an end to exclusion and an end to policies that artificially drive up rents and housing costs for everyone.34

The 2021 legislation succeeded—after so many years of failure—in part because liberal supporters concerned about housing affordability and exclusion created an urban–rural coalition. “Groups that don’t normally work together” championed reform, Wiener notes, as crucial votes of support in the state assembly came not only from urban Democrats but also from seven Republicans, mostly representing rural areas, who provided the margin of victory. In the Assembly, forty-one votes were needed for passage. With just thirty-eight Democratic votes in support (and twenty-one Democrats opposed or not voting), the seven Republican votes in support proved crucial.35

Interest group politics were also part of the story. The California Association of Realtors, an important constituency group, supported reform.36 But there were also broader themes that emerged. In particular, the odd political bedfellows were able to tap into two populist threads that crossed party lines: one that focused on housing affordability; and another that focused on exclusion.

Property Values versus Affordability

For decades, most fights over zoning reform were won by Not in My Backyard (NIMBY) voices, who raised concerns that any changes in the neighborhood could threaten property values. Propping up property values is at the heart of why exclusionary zoning programs were created in the first place and why they endure to this day.37

The flip side of existing homeowners wanting very high returns on their investment, however, is that it makes housing unaffordable for everyone else. And in California, the voters who constituted “everyone else” became fed up as the lack of supply of housing drove prices ever higher. Housing prices had become intolerable in California, where the median home price exceeded $800,000, and some homes were selling for $1 million over the asking price. Meanwhile, homelessness—which research finds is directly related to housing affordability—rose 40 percent in recent years in the state.38 The problem had reached crisis proportions. Affordability had become such a problem in California that in 2022 Governor Gavin Newsom was willing to declare publicly, “NIMBYism is destroying the state.”39

The politics around affordability had changed because affordability, previously thought to be mainly the concern of subsidized housing advocates and tenant groups, now had much greater political salience because it affected a wider swath of Americans. In parts of California, for example, college-educated upper-middle-class millennials were complaining, says Brian Hanlon, president and CEO of California YIMBY: “I went to a good school and can’t afford rent? WTF?”40 Census figures showed that one-third of California’s renters paid more than half their monthly income for rent.41

Politically allied with these millennials were employers in the tech industry who were having trouble recruiting and retaining employees given astronomical housing prices.42 During the legislative debates over housing, more than a hundred CEOs of technology companies wrote in support of state legislation to reduce exclusionary zoning, arguing: “The lack of homebuilding in California imperils our ability to hire employees and grow our companies,” in part because “the housing shortage places a huge burden on workers, many of whom face punishingly long commutes and pay over half of their income on rent.”43 Affordability had become such a crisis in Milpitas, California, that the school district sent a note to parents asking them if they allow teachers to move in with them and rent a room.44

As a result of extremely high home prices and rents, people were no longer drawn to California, even though it had high paying jobs—a major reversal of historic trends. In the twentieth century, Americans had moved in droves to California, where good jobs were accompanied by a sufficient housing supply. During the Depression, for example, poor white families, like those depicted in The Grapes of Wrath, moved from Oklahoma to California seeking better opportunities. In the 1950s and 1960s, one economist notes, “housing prices throughout the United States were fairly similar among regions,” and California was not more expensive than that in comparable communities in the Midwest or Northeast.45 In 1960, the median price for a home was about the same in Illinois and Nevada as in California.46

Today, by contrast, workers make twice as much in San Jose, California as in Orlando, Florida, but housing costs are four times as high.47 As a result, workers are actually leaving California in large numbers. Sam Khater of Freddie Mac notes, “In the past, Americans used to move for opportunity. But in recent years, they’ve been moving for affordability.”48 Between 2010 and 2020, Silicon Valley, which is rich in jobs, grew by a modest 6.5 percent, while Harris County, Texas, which includes Houston and has less land but cheaper housing, grew 175 percent faster.49 During that decade, California, with its high-paying jobs, grew so little that after the 2020 Census, it lost a congressional seat for the first time in its more than 170-year history.50

“In the past, Americans used to move for opportunity. But in recent years, they’ve been moving for affordability.”

Scholar John Mangin has noted, “For the first time in American history, it makes sense to talk about whole regions of the country ‘gentrifying’—whole metropolitan areas whose high housing costs have rendered them inhospitable” to many low-income and middle-class families.51 This is particularly true on the West Coast, says economist Paul Krugman. Restrictive zoning has driven up housing prices to the point where “California as a whole is suffering from gentrification.” Even though California is bound by an ocean, Krugman says, “there is plenty of scope for building up”52—but restrictive housing laws made it impossible to do so.

Even some die-hard NIMBY constituencies appeared somewhat receptive to the idea that exclusionary zoning negatively affects even their own families. Wiener says that older, upper-middle-class white homeowners were sometimes open to the argument that residents should work to avoid a situation in which their children were not “going to be able to afford to live in the community where they grew up.”53 Wiener says framing the stakes in those personal family terms was often “extremely powerful with people.”54

In short, if NIMBY concerns about property values ruled politics for most of the twentieth and early twenty-first centuries, by 2021, affordability concerns grew so strong that in political terms, the interests of renters and would-be buyers trumped those of existing homeowners in exclusive communities.

A Coalition of the Excluded

If affordability was the key driver of reform, there was also a populist thread that united people of both political parties—and of all races—who felt excluded by wealthy jurisdictions that were putting up barriers to housing in their communities.

Exclusionary zoning helps perpetuate a separate ecosystem for the privileged. As the Atlantic’s George Packer points out, regular Americans are disadvantaged under the current rules, because the deck is stacked in myriad ways—including use of zoning laws—so that an elite class of salaried professionals “go to college with one another, intermarry, gravitate to desirable neighborhoods in large metropolitan areas, and do all they can to pass on their advantages to their children.”55

Republicans representing working-class white communities and Democrats representing communities of color came together in an alliance of the excluded. For example, activists noted, some Republican legislators in California’s exurban areas, who represent constituents sick of long commutes, were angered by wealthy white liberals on the coast who say they are concerned about the environment and inequality but were unwilling to make room in their own neighborhoods for apartments.56 And civil rights advocates stressed the ways in which exclusionary zoning has been used to discriminate against people of color. The University of California at Berkeley’s Othering and Belonging Institute, for example, emphasized that:

Zoning has historically been used to restrict admissibility and to create racially exclusive communities. Rooted in racist past and discriminatory intent, the effects of restrictive zoning in current times are still discriminatory even if the intent is not explicitly racist. Single-family zoned areas, that do not allow development of multi-family housing, has been shown to increase in racial segregation and income inequality through research and practice. Single-family zoning is a mechanism to keep people of color and low income away from neighborhoods that are heavily white and are resource rich.57

Subsequent Successes

Passage of SB 9 and SB 10 begat more successes. In August 2022, California legislators passed AB 2097 to reduce parking minimums near transit stops and AB 2011 to require by-right approval of affordable housing in commercially zoned lands. Unions and pro-housing advocates came together to get the legislation across the finish line.58

State legislator Buffy Wicks (D) of Oakland said the political climate around housing had changed dramatically over time. “When I ran in 2018, it was a vulnerability to be unapologetically pro-housing,” she said. “Now it is absolutely an asset. I get up on the floor of the Assembly and say, 10 times a week, ‘We have to build more housing in our communities, all of our communities need more housing, we need low-income, middle-income, market rate.’ You couldn’t do that in a comfortable way four years ago.”59

The political change that is taking place can be seen in cities like Berkeley, California. For aging residents of Berkeley, being against private sector development was, dating back to the 1970s, the progressive stance: it was seen as pro-environment and anti-corporate. But as Daniel Dwayne outlined in an article in New York Times Magazine, with housing prices skyrocketing, the equation has been flipped, and it is now YIMBY voices that own “the moral and political high ground.” Today, favoring apartment construction is “being on the side of the angels.”60

Although educational equity was not a central concern during the zoning reform debates in California, raising that question alongside affordability could provide another powerful argument on behalf of change. Because 73 percent of American students attend neighborhood public schools, reforms that open up communities to more types of housing can provide greater access to high-performing schools.61 This is an important dimension of housing reform that leaders for change in other communities should strongly consider.62

The Impact of Zoning Reform on Housing Production, Prices, and, Ultimately, Education

It will take time to see the full impact of the 2021 California reforms (which went into effect in 2022) because changes to housing stock tend to be gradual, as construction and converting single units to duplexes, triplexes, and fourplexes takes planning and time. Moreover, critics have noted that to allow builders to make a profit, it is important that legislation not only legalize multi-family homes but also allow them to be larger than the single-family homes they replace—an innovation Portland has adopted but California has yet to consider.63

However, evidence from an older reform that is easier to implement—by, for example, allowing the conversion of a garage into an accessory dwelling unit—is already showing signs of success. After the California legislature adopted changes to allow single-family homes to add ADUs in 2016, activists said it was “like opening a floodgate.” In 2018, Los Angeles permitted more than four thousand units, “an astonishing figure when one considers that municipal authorities tend to add just a few hundred affordable housing units per year,” one observer noted. The potential is enormous: converted garages or backyard cottages could add up to five hundred thousand housing units in Los Angeles.64 Statewide in 2020, ADUs constituted more than 10 percent of new housing. That figure is up from less than 1 percent eight years earlier.65 Between 2016 and 2021, the number of ADUs permitted increased by a whopping 1,421 percent.66 The numbers keep rising. In 2022, Los Angeles issued 7,160 ADU permits, compared with 1,287 permits for single-family homes.67 Statewide, the number of permits issued for ADUs shot up from 1,300 in 2016 to more than 22,000 in 2022.68

And in other communities that have allowed missing middle housing, reforms have had the desired effect over time. Researchers Edward Pinto and Tobias Peter of the American Enterprise Institute, for example, have studied Palisades Park, New Jersey, which, unlike most of its neighboring communities, has long allowed the construction of duplexes. Builders have converted older single-family homes into duplexes and the community’s population has grown 50 percent over the past forty years. (Populations in nearby communities, they say, “remained flat.”)69 They found similar growth in housing after Seattle loosened some zoning restrictions to allow townhomes where only single-family detached homes had existed.70 Similarly, a 2023 analysis by the Pew Research Center found that in four American jurisdictions that have relaxed zoning restrictions—Minneapolis, Minnesota; New Rochelle, New York; Portland, Oregon; and Tysons, Virginia—more housing has been produced and rent increases have slowed.71

Auckland, New Zealand’s reforms to allow missing middle housing has also had an important impact. A law passed in 2016 to allow duplexes, triplexes, and townhomes on single-family lots resulted in a tripling of new housing unit permits between 2015 and 2020, from 6,000 to 14,300. In addition, Australian economist Matthew Maltman found “a significant slowing of rental price growth since the policy was implemented.” He concluded that “both incomes and inflation have grown faster than the price of rental housing.”72

In Tokyo, Japan, likewise, relaxed zoning laws allow for the construction of homes where people want them. As a result, Tokyo has built more housing units in the past half century than New York City has in total. Families earning a minimum wage can afford to rent a typical two-bedroom apartment in six of Tokyo’s twenty-three wards. By comparison, according to Binyamin Appelbaum of the New York Times, “two people working minimum-wage jobs cannot afford the average rent for a two-bedroom apartment in any of the 23 counties in the New York metropolitan area.” Tokyo is able to create affordable housing even though little of the housing is publicly subsidized.73

Over the long term, these housing reforms will have important implications for educational opportunity. When restrictions on the type of housing that can be built are lifted, builders can create different types of housing, at different price points, that in turn can be made available to people of a greater variety of racial and economic backgrounds than a regime under which only single-family homes, often on large plots of land, are legal to build. In Seattle, for example, American Enterprise Institute researchers Edward Pinto and Tobias Peter have found that changing zoning laws to allow townhouses has “enabled homeownership for lower-income, younger, and more diverse households.”74 Pinto found the same to be true in Charlotte, North Carolina.75 Research also finds that socioeconomic segregation in Japan, with its comparatively relaxed zoning laws, is relatively low. Japan’s largest city, Tokyo, has lower levels of economic segregation than many U.S. and European cities.76 Lower economic residential segregation translates into lower levels of school segregation.77

Lessons for New York State

What are the lessons from California and elsewhere for reform efforts in New York State? Because every state has a somewhat different political culture, one must be careful in attempting to transfer political models. Having said that, California and New York are both “blue states” that have suffered from very high housing prices, and some realities of American politics can cross state lines.

Notably, the emergence of cross-racial, cross-party class-based political coalitions, while relatively rare in American politics writ large, have emerged in favor of less restrictive zoning not only in California but also in states as varied as Massachusetts, Texas, and Oregon.

In 1969, a diverse group of Massachusetts state legislators allied against wealthy suburbs to pass an anti–snob zoning law. The law provided that the state could override local zoning in communities where less than 10 percent of housing stock is affordable.78 Forty-one years later, an effort spearheaded by rich suburbs to repeal the anti–snob zoning provision, known as 40b, was turned back in a statewide referendum. Some 58 percent of voters supported retaining the populist law.79

Likewise, in Houston, Texas, a strong multiracial coalition of working-class voters has twice come together to defeat exclusionary zoning efforts. In 1962 and 1993, wealthy homeowners pushed for Houston to adopt zoning laws through voter referenda, but on both occasions, opponents argued that such laws would increase segregation and drive up housing prices. The zoning efforts were defeated with votes that “came principally from working class Houstonians of all races,” researcher Nolan Gray writes.80

And as will be explained in much greater detail in a subsequent Century Foundation report, Oregon passed the nation’s first bipartisan statewide ban on single-family exclusive zoning in 2019 with a populist urban and rural political coalition very similar to the one forged in California.81

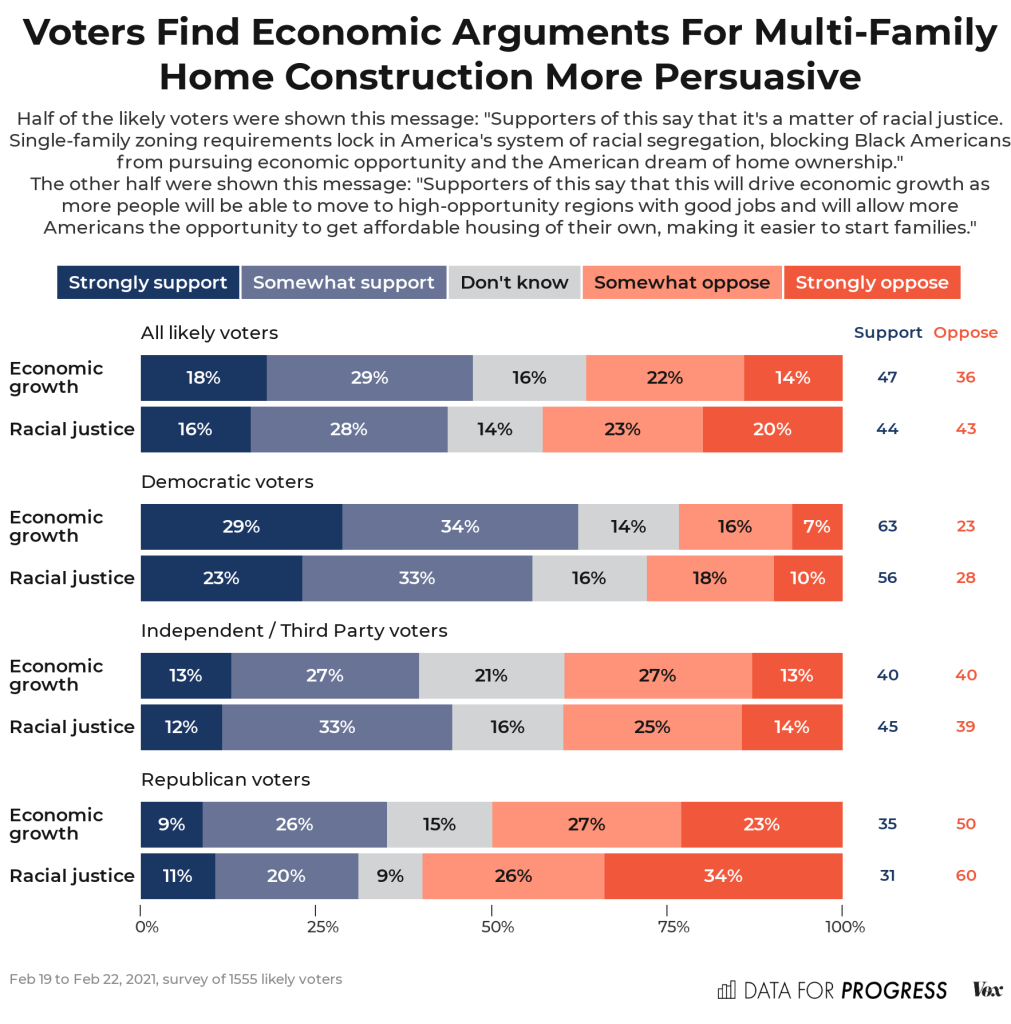

These efforts did not emphasize race alone. Indeed, public opinion polling finds that a strictly racial appeal can reduce voter support. A 2021 poll by Data for Progress and Vox found that the economic case for allowing more construction of multifamily housing has broader public support than the narrower racial argument. Americans favored multifamily zoning over single-family zoning by just one percentage point (44 percent to 43 percent) after hearing that “Supporters of this say that it’s a matter of racial justice. Single-family-exclusive zoning requirements lock in America’s system of racial segregation, blocking Black Americans from pursuing economic opportunity and the American dream of home ownership.” By contrast, support grew to eleven percentage points (47 percent to 36 percent) when respondents were presented with an economic argument: “Supporters of this say that this will drive economic growth as more people will be able to move to high opportunity regions with good jobs and will allow more Americans the opportunity to get affordable housing on their own, making it easier to start families.” Even Democrats, who liked both arguments, favored the economic growth rationale over the racial justice argument, by twelve points.82

Figure 1

None of this is to suggest that a political coalition for zoning reform cannot include legislators representing wealthy liberal districts. Precisely because they are liberal, it may be possible to open their eyes to the fact that exclusionary zoning has real victims—poor families who must choose between paying rent and buying medicine because housing costs are so high, and disadvantaged children whose lives are thwarted because zoning laws exclude them from strong public schools. Indeed, moral appeals have had some success in bringing about city-level reform in places such as Arlington, Virginia; Berkeley, California; and Montgomery County, Maryland.83 And many traditional conservatives have supported zoning reform in places such as Montana as a property rights issue.84

To facilitate a cross-racial populist coalition, along with upper-middle class white liberals of good will, New York legislators could galvanize voters around the idea of an Economic Fair Housing Act, that benefits working-class people of all races.

Members of Congress have discussed the idea of creating a federal Economic Fair Housing Act, under which communities that discriminate by income through their zoning laws would, if challenged, have to provide a powerful justification that such laws are “necessary.” If they failed to do so, federal judges could impose injunctive relief to eliminate the economic discrimination. A municipality that banned multifamily housing in much of its community, for example, could come under close judicial scrutiny under the law.85

New York State could take the lead in creating the nation’s first state-level Economic Fair Housing Act. In the realm of civil rights laws, state governments have often enacted their own anti-discriminatory laws in advance of federal action. For example, several states—including New York—have enacted protections against “source-of-income” discrimination (typically, to shield Section 8 Housing Choice Voucher recipients from discrimination by landlords who refused to take vouchers.)86 A New York State Economic Fair Housing Act could make clear that just as source-of-income discrimination is wrong, so is income discrimination by government zoning laws.

The politics of zoning reform are tough, as New York State has seen. That is all the more reason to try some of the creative strategies that reach beyond typical coalitions and have worked elsewhere to make housing less expensive and America less unequal.

Notes

- Governor Kathy Hochul, “Governor Hochul Announces Statewide Strategy to Address New York’s Housing Crisis and Build 800,000 New Homes,” January 10, 2023, https://www.governor.ny.gov/news/governor-hochul-announces-statewide-strategy-address-new-yorks-housing-crisis-and-build-800000; and Governor Kathy Hochul, “Remarks as Prepared: Governor Hochul Delivers 2023 State of the State,” January 10, 2023, https://www.governor.ny.gov/news/remarks-prepared-governor-hochul-delivers-2023-state-state.

- Luis Ferré-Sadurní and Mihir Zaveri, “New York Officials Failed to Address the Housing Crisis. Now What?” New York Times, April 27, 2023, https://www.nytimes.com/2023/04/27/nyregion/nyc-housing-crisis.html; Grace Ashford, “Gov. Hochul Gets a Budget Deal, but No Signature Win,” New York Times, April 28, 2023, https://www.nytimes.com/2023/04/28/nyregion/hochul-budget-ny.html; and Kahlenberg, Richard D. Kahlenberg, “How Zoning Drives Educational Inequality: The Case of Westchester County,” The Century Foundation, July 17, 2023, https://tcf.org/content/report/how-zoning-drives-educational-inequality-the-case-of-westchester-county/.

- See e.g. By Janaki Chadha, “Hochul faces an ‘uprising’ over her plan to build new housing in NYC suburbs,” Politico, February 11, 2023, https://www.politico.com/news/2023/02/11/hochul-faces-uprising-housing-plan-00080949; and Sam Mellins, “The State Assembly Is Foreclosing Hochul’s Housing Supply Plan,” New York Focus, April 18, 2023, https://nysfocus.com/2023/04/18/hochul-housing-compact-dead-assembly-budget. Suffolk County on Long Island is politically mixed—it split evenly, 49 percent to 49 percent, when voting in the race between Joe Biden and Donald Trump in 2020. But Nassau County went 54 percent to 45 percent for Biden. For Long Island and Westchester vote totals, see “New York Presidential Results,” Politico, January 6, 2021, https://www.politico.com/2020-election/results/new-york/.

- Portions of this case study draw from Richard D. Kahlenberg, Excluded: How Snob Zoning, NIMBYism and Class Bias Build the Walls We Don’t See (New York: Public Affairs Books, 2023).

- Richard D. Kahlenberg, “How Housing Policies Create Unequal Educational Opportunities: The Case of Queens, New York,” The Century Foundation, April 3, 2023, https://tcf.org/content/report/how-housing-policies-create-unequal-educational-opportunities-the-case-of-queens-new-york/; Richard D. Kahlenberg, “Housing and Educational Inequality: The Case of Long Island,” The Century Foundation, June 1, 2023, https://tcf.org/content/report/housing-and-educational-inequality-the-case-of-long-island/; Richard D. Kahlenberg, “How Zoning Drives Educational Inequality: The Case of Westchester County,” The Century Foundation, July 17, 2023, https://tcf.org/content/report/how-zoning-drives-educational-inequality-the-case-of-westchester-county/; and Richard D. Kahlenberg, “How Zoning Promotes Inequality in Education: The Case of the Buffalo Area,” The Century Foundation, September 21, 2023. https://tcf.org/content/report/how-zoning-promotes-inequality-in-education-the-case-of-the-buffalo-area/.

- Conor Dougherty, “After Years of Failure, California Lawmakers Pave the Way for More Housing,” New York Times, August 26, 2021, https://www.nytimes.com/2021/08/26/business/california-duplex-senate-bill-9.html.

- Dougherty, “After Years of Failure,”; and Ilya Somin, “California Enacts Two Important New Zoning Reform Laws,” Reason, September 17, 2021.

- National Center for Education Statistics, “Public School Choice Programs,” https://nces.ed.gov/fastfacts/display.asp?id=6.

- See Dan Bertolet and Nisma Gabobe, “LA ADU Story: How a State Law Sent Granny Flats Off the Charts,” Sightline Institute, April 5, 2019, https://www.sightline.org/2019/04/05/la-adu-story-how-a-state-law-sent-granny-flats-off-the-charts/.

- Conor Dougherty and Brad Plumer, “A Bold, Divisive Plan to Wean Californians from Cars,” New York Times, March 16, 2018, https://www.nytimes.com/2018/03/16/business/energy-environment/climate-density.html.

- See Jonathan Woetzel, Jan Mischke, Shannon Peloquin, and Daniel Weisfield, “Closing California’s Housing Gap,” McKinsey Global Institute, October 2016, https://www.mckinsey.com/featured-insights/urbanization/closing-californias-housing-gap. See also Liam Dillon, “Get Ready for a Lot More Housing Near the Expo Line and Other California Transit Stations If New Legislation Passes,” Los Angeles Times, January 4, 2018.

- Dante Ramos, “Go On, California—Blow Up Your Lousy Zoning Laws,” Boston Globe, January 14, 2018, https://www.bostonglobe.com/opinion/2018/01/14/california-blow-your-lousy-zoning-laws/AcT0vOJCdArOJp3cBH9zmJ/story.html.

- Katherine Levine Einstein, David M. Glick, and Maxwell Palmer, Neighborhood Defenders: Participatory Politics and America’s Housing Crisis (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2020), 158.

- Dougherty and Plumer, “A Bold, Divisive Plan to Wean Californians from Cars.”

- Einstein, Glick, and Palmer, Neighborhood Defenders, 154.

- City Council News Service, “LA City Council Opposes State Housing Bill,” Los Angeles Daily News, March 27, 2018, https://www.dailynews.com/2018/03/27/la-city-council-opposes-state-housing-bill/.

- Einstein, Glick, and Palmer, Neighborhood Defenders, 152.

- Einstein, Glick, and Palmer, Neighborhood Defenders, 156 (quoting Randy Shaw, editor of Beyond Chron and director of San Francisco’s Tenderloin Housing Clinic).

- Joe Fitzgerald Rodriguez, “SB 827 Rallies End with YIMBYs Shouting Down Protesters of Color,” San Francisco Examiner, April 5, 2018, https://www.sfexaminer.com/news/sb-827-rallies-end-with-yimbys-shouting-down-protesters-of-color/article_42f1bb0c-c4c5-5401-a395-5aff1b28137c.html. https://www.sfexaminer.com/news/sb-827-rallies-end-with-yimbys-shouting-down-protesters-of-color/article_42f1bb0c-c4c5-5401-a395-5aff1b28137c.html

- See “The YIMBY Guide to Bullying and Its Results: SB 827 Goes Down in Committee,” City Watch, April 19, 2018, https://www.citywatchla.com/los-angeles/15298-the-yimby-guide-to-bullying-and-its-results-sb-827-goes-down-in-committee.

- Einstein, Glick, and Palmer, Neighborhood Defenders, 44, citing Dillon, “A Major California Housing Bill Failed After Opposition from the Low-Income Families It Aimed to Help,” Los Angeles Times, May 2, 2018.

- Dougherty, “After Years of Failure.”

- See Conor Dougherty, “Where the Suburbs End: A Single-Family Home from the 1950s Is Now a Rental Complex and a Vision of California’s Future,” New York Times, October 8, 2021, https://www.nytimes.com/2021/10/08/business/economy/california-housing.html; Grace Hase, “New law signals change in how California legislators are attacking the housing crisis,” Washington Post, October 8, 2021, https://www.washingtonpost.com/national/new-law-signals-change-in-how-california-legislators-are-attacking-the-housing-crisis/2021/10/07/9a2d2056-2310-11ec-b3d6-8cdebe60d3e2_story.html; and Stephen Eide, “Homelessness Is Behind the Anger at Gavin Newsom,” Wall Street Journal, September 4, 2021 https://www.wsj.com/articles/homelessness-recall-election-gavin-newsom-california-larry-elder-crime-encampment-public-housing-zoning-regulations-11630703089. The bill was passed in August but signed by the governor in September.

- Conor Dougherty, “After Years of Failure”; and Ilya Somin, “California Enacts Two Important New Zoning Reform Laws,” Reason, September 17, 2021.

- Conor Dougherty, “Where the Suburbs End.”

- Somin, “California Enacts Two Important New Zoning Reform Laws”; and Judith Shulevitz, “Co-Housing Makes Parents Happier,” New York Times, October 24, 2021, 4.

- See Ben Fritz and Zusha Elinson, “California Limits Single-Family Home Zoning,” Wall Street Journal, September 16, 2021, https://www.wsj.com/articles/california-limits-single-family-home-zoning-11631840086.

- Mathew Kahn, “Do Liberal Cities Limit New Housing Development? Evidence from California,” Journal of Urban Economics, March 2011, https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0094119010000720.

- Johnny Harris and Binyamin Appelbaum, “Why Do States with Democratic Majorities Fail to Live Up to Their Values?” opinion, New York Times video, 14:20, November 9, 2021, https://www.nytimes.com/video/opinion/100000007886969/democrats-blue-states-legislation.html. See also “City of Palo Alto Rezoning of Maybell Avenue, Measure D (November 2013),” Ballotpedia, from the November 5, 2013, election ballot, https://ballotpedia.org/City_of_Palo_Alto_Rezoning_of_Maybell_Avenue,_Measure_D_(November_2013).

- Brian Hanlon, quoted in Farhad Manjoo, “America’s Cities Are Unlivable. Blame Wealthy Liberals,” New York Times, May 22, 2019, https://www.nytimes.com/2019/05/22/opinion/california-housing-nimby.html.

- Scott Wiener, “Paths for the New Administration to Reduce Exclusionary Zoning” (transcript of The Century Foundation/Bridges Collaborative Roundtable Discussion videoconference, December 11, 2020), 64 (hereinafter referred to as Roundtable Discussion transcript).

- See Kahlenberg, Excluded: How Snob Zoning , NIMBYism and Class Bias Build the Walls We Don’t See, 123–55.

- Scott Wiener, Roundtable Discussion transcript, 69; see also Scott Wiener, Roundtable Discussion transcript, 78.

- Richard D. Kahlenberg, “Updating the Fair Housing Act to Make Housing More Affordable,” The Century Foundation, April 9, 2018, https://tcf.org/content/report/updating-fair-housing-act-make-housing-affordable/.

- Scott Wiener, Roundtable Discussion transcript, 77–78; and Michael Andersen, “Five Lessons from California’s Big Zoning Reform: A Pattern Is Emerging Here,” Sightline Institute, August 26, 2021, https://www.sightline.org/2021/08/26/four-lessons-from-californias-big-zoning-reform/.

- Jenny Schuetz, Fixer-Upper: How to Repair America’s Broken Housing System (Washington, D.C.: Brookings Institution Press, 2022), 150.

- Kahlenberg, Excluded, 134.

- Dougherty, “After Years of Failure, California Lawmakers Pave the Way.”

- Conor Dougherty, “Twilight of the NIMBY,” New York Times, June 5, 2022, https://www.nytimes.com/2022/06/05/business/economy/california-housing-crisis-nimby.html.

- Brian Hanlon, interview with author, April 20, 2018.

- Dougherty and Plumer, “A Bold, Divisive Plan to Wean Californians from Cars.”

- Conor Dougherty, “Getting to Yes on Nimby Street,” New York Times, December 3, 2017.

- “Let’s End California’s Housing Shortage—Support SB 827,” technology industry leaders’ letter in support of SB 827, January 24, 2018, https://www.cayimby.org/technetwork/.

- Jonathan Edwards, “School District in Bay Area Asks Parents to Let Teachers Move In as Rent Soars,” Washington Post, September 2, 2022, https://www.washingtonpost.com/nation/2022/09/02/teacher-housing-california-bay-area/.

- William Fischel, Zoning Rules! The Economics of Land Use Regulation (Cambridge, MA: Lincoln Institute of Land Policy), 165.

- “Historical Census of Housing Tables—Home Values,” State of Wyoming, http://eadiv.state.wy.us/housing/Home_Value_ST.htm.

- M. Nolan Gray, Arbitrary Lines: How Zoning Broke the American City and How to Fix It (Washington, DC: Island Press, 2022), 74.

- Debra Kamin, “The Market Tectonics of California Real Estate,” New York Times, May 28, 2021, https://www.nytimes.com/2021/05/28/realestate/california-real-estate.html.

- Edward Glaeser and David Cutler, “The American Housing Market Is Stifling Mobility,” Wall Street Journal, September 4, 2021, https://www.wsj.com/articles/the-american-housing-market-is-stifling-mobility-11630590967.

- Kathleen Ronayne, “California Losing Congressional Seat for First Time,” Associated Press, April 26, 2021, https://apnews.com/article/census-2020-government-and-politics-california-dd4a4f3ce3070231b0aecdc1cac3e97b.

- John Mangin, “The New Exclusionary Zoning,” Stanford Law & Policy Review 25 (2014): 92–93.

- Paul Krugman, “The Gentrification of Blue America,” New York Times, August 27, 2021, https://www.nytimes.com/2021/08/27/opinion/California-housing-price-economy.html.

- Scott Wiener, Roundtable Discussion transcript, 68.

- Scott Wiener, Roundtable Discussion transcript, 82.

- George Packer, Last Best Hope: America in Crisis and Renewal (New York: Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 2021), 86; and Richard D. Kahlenberg, “You Don’t Have to Spare NIMBYs’ Feelings: Class bias is not, in fact, OK in housing,” Slate, July 28, 2023, https://slate.com/business/2023/07/class-bias-housing-nimby-yimby-atlantic-zoning.html.

- Brian Hanlon in David Roberts, “The future of housing policy is being decided in California,” Vox, April 4, 2018. https://www.vox.com/cities-and-urbanism/2018/2/23/17011154/sb827-california-housing-crisis

- “Equity Metrics: Zoning Reform,” University of California at Berkeley Othering and Belonging Institute, https://belonging.berkeley.edu/zoning-reform.

- James Brasuell, “California Makes Planning History, Resets the Housing Status Quo,” Planetizen, September 1, 2022, https://www.planetizen.com/news/2022/09/118560-california-makes-planning-history-resets-housing-status-quo; and Darrell Owens, “YIMBYs Triumph in California,” Discourse Lounge (newsletter), September 3, 2022, https://darrellowens.substack.com/p/yimby-triumph-in-california.

- Conor Dougherty and Soumya Karlamangla, “California Fights Its NIMBYs,” New York Times, September 1, 2022, https://www.nytimes.com/2022/09/01/business/economy/california-nimbys-housing.html.

- Daniel Duane, “A Tale of Paradise, Parking Lots and My Mother’s Berkeley Backyard,” New York Times Magazine, May 30, 2023, https://www.nytimes.com/2023/05/30/magazine/housing-berkeley-yimby-fight.html.

- “Public School Choice Programs,” National Center for Education Statistics, https://nces.ed.gov/fastfacts/display.asp?id=6.

- For the importance of zoning reform to educational opportunity, see, e.g. Kahlenberg, ““How Zoning Drives Educational Inequality: The Case of Westchester County,” The Century Foundation, July 17, 2023, https://tcf.org/content/report/how-zoning-drives-educational-inequality-the-case-of-westchester-county/.

- See e.g. Christian Britschgi, “Despite Multiple States Abolishing Single Family-Only Zoning, Very Few Duplexes and Triplexes Are Being Built,” Reason, March 14, 2023, https://reason.com/2023/03/14/despite-multiple-states-abolishing-single-family-only-zoning-very-few-duplexes-and-triplexes-are-being-built/ (noting that Portland’s reforms have been more successful those in other jurisdictions because it allows duplexes to be larger than single family homes, which helps offset the cost of demolition and construction); and David Garcia and Bill Fulton, “California has passed more than 100 housing laws since 2016. Are any of them working?” Los Angeles Times, May 5, 2023, https://www.latimes.com/opinion/story/2023-05-05/california-housing-shortage-crisis-laws-reforms-rents-homes-homeless (noting that housing permits remain too low at 100,000 a year, but that some of the provisions “have had a clear, positive effect”).

- Diana Lind, Brave New Home: Our Future in Smarter, Simpler, Happier Housing (New York: Bold Type Books, 2020), 75, 122–24.

- Dougherty, “Where the Suburbs End.”

- M. Nolan Gray, “The Housing Revolution Is Coming,” The Atlantic, October 5, 2022, https://www.theatlantic.com/ideas/archive/2022/10/california-accessory-dwelling-units-legalization-yimby/671648/.

- Erica Werner, “‘Granny flats’ play surprising role in easing California’s housing woes State and local policies have made accessory dwelling units easier to build in recent years, and homeowners are signing up in droves,” Washington Post, May 21, 2023, https://www.washingtonpost.com/business/2023/05/21/adu-granny-flat-california-housing-crisis/.

- Michelle Cottle, “The Magic of Granny Flats,” New York Times, September 6, 2023. https://www.nytimes.com/2023/09/06/opinion/seniors-housing-adus.html

- Edward Pinto and Tobias Peter, “California’s Free-Market Housing Fix,” Wall Street Journal, February 3, 2022, https://www.wsj.com/articles/california-free-market-housing-fix-sb9-lots-units-four-value-crisis-zoning-requirements-property-rights-11643922512. See also Edward Pinto, “Charlotte’s Unified Development Ordinance,” AEI Housing Center, June 2, 2023, slides 16-21. (re Palisades Park)

- Edward Pinto and Tobias Peter, “Light Touch Density and Filtering Down: City of Seattle Case Study,” American Enterprise Institute, July 3, 2023, https://www.aei.org/research-products/report/light-touch-density-and-filtering-down-city-of-seattle-case-study/.

- Alex Horowitz and Ryan Canavan, “More Flexible Zoning Helps Contain Rising Rents: New data from 4 jurisdictions that are allowing more housing shows sharply slowed rent growth,” Pew Charitable Trusts, April 17, 2023, https://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/articles/2023/04/17/more-flexible-zoning-helps-contain-rising-rents.

- Eliza Relman, “America, take note: New Zealand has figured out a simple way to bring down home prices,” Business Insider, August 7, 2023, https://www.businessinsider.com/america-lower-rents-home-prices-build-more-houses-new-zealand-2023-8.

- Binyamin Appelbaum, “The Big City Where Housing is Still Affordable,” New York Times, September 11, 2023, https://www.nytimes.com/2023/09/11/opinion/editorials/tokyo-housing.html.

- Edward J. Pinto and Tobias Peter, “Light Touch Density and Filtering Down: City of Seattle Case Study,” American Enterprise Institute, July 3, 2023, https://www.aei.org/research-products/report/light-touch-density-and-filtering-down-city-of-seattle-case-study/.

- Edward J. Pinto, “Charlotte’s Unified Development Ordinance: An Opportunity to Expand Housing Supply and Choice with Light-Touch Density and Walkable-Oriented Development,” American Enterprise Institute, June 2, 2023, slides 35–37.

- Urban Socio-Economic Segregation and Income Inequality: A Global Perspective, ed. Maarten van Ham, Tiit Tammaru, Rūta Ubarevičienė, and Heleen Janssen (New York: Springer, 2021), 13, fig. 1.3, and 14, https://link.springer .com/content/pdf/10.1007%2F978-3-030-64569-4.pdf; and Masaya Uesugi, “Changes in Occupational Structure and Residential Segregation in Tokyo,” in van Ham et al., Urban Socio-Economic Segregation and Income Inequality, 210.

- Anna K. Chmielewski and Sean F. Reardon, “Education,” in “State of the Union: Policy and Inequality Report 2016,” special issue, Pathways, 2016, 48, fig. 4, https://inequality.stanford.edu/sites/default/files/Pathways-SOTU-2016.pdf.

- Fischel, Zoning Rules! 150.

- Fischel, Zoning Rules! 150. See also Einstein, Glick, and Palmer, Neighborhood Defenders, 106–107.

- Gray, Arbitrary Lines, 145–46.

- Michael Andersen, “Eight Ingredients for a State-Level Zoning Reform: Lessons from Oregon’s Landmark Legalization of Fourplexes and Townhouses,” Sightline Institute, August 13, 2021, https://www.sightline.org /2021/08/13/eight-ingredients-for-a-state-level-zoning-reform/; and Kahlenberg, Excluded, 174–78.

- Jerusalem Demsas, “How to Convince a NIMBY to Build More Housing,” Vox, February 24, 2021, https://www.vox.com/22297328/affordable-housing-nimby-housing-prices-rising-poll-data-for-progress.

- See Richard D. Kahlenberg, “You Don’t Have to Spare NIMBYs’ Feelings: Class bias is not, in fact, OK in housing,” Slate, July 28, 2023, https://slate.com/business/2023/07/class-bias-housing-nimby-yimby-atlantic-zoning.html.

- See Kriston Capps, “How YIMBYs Won Montana,” Bloomberg CityLab, April 28, 2023, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2023-04-28/montana-s-yimby-revolt-aims-to-head-off-a-housing-crisis; and Kahlenberg, Excluded, 229-231.

- See Jerusalem Demsas, “Could a 54-year-old civil rights law be revived? Decades after Martin Luther King Jr.’s fight, American cities still segregate communities by race and class,” Vox, January 17, 2022 (quoting Rep. Emmanuel Cleaver on the need for an Economic Fair Housing Act); Richard D. Kahlenberg, “An Economic Fair Housing Act,” The Century Foundation, August 3, 2017, https://tcf.org/content/report/economic-fair-housing-act/; Kahlenberg, Excluded,191–205; and Equitable Housing Institute, “Economic Fair Housing Act of 2021: Partial Draft Bill and Comments,” November 30, 2020, https://www.equitablehousing.org/images/PDFs/PDFs–2018-/EHI_Economic_FHA_of_2021_draft-rev_11-30-20.pdf.

- See Poverty and Race Research Action Council, “Expanding Choice: Practical Strategies for Building a Successful Housing Mobility Program—Appendix B: State, Local and Federal Laws Barring Source-of-Income Discrimination,” July 2023, http://www.prrac.org/pdf/AppendixB.pdf.