With an upended economy, skyrocketing unemployment, and a particularly hard-hit higher education system,1 the post-pandemic recovery years will be ripe for predatory colleges to wrangle in as many unsuspecting students as possible. Known for aggressive recruiting especially during periods of economic distress,2 for-profit colleges have already started ramping up3 efforts to target students looking to “upskill” for a new job or industry and those frustrated with the online transition of their traditional institutions. Unfortunately, the federal consumer protections that were adopted after the Great Recession, adopted as a result of lessons learned during that downturn, have been weakened or eliminated by the Trump administration.

Since February, The Century Foundation has been examining advertising by colleges to identify how the next big college rip-offs might be stopped before they bring widespread harm to students and taxpayers. While it cannot be said for certain how predatory college marketing will evolve in the coming months or years of economic struggle, there is no doubt that some college operators hope to capitalize on the increased consumer vulnerability of a tough economy. TCF’s research has focused primarily on the 100 colleges with the largest online enrollments before the COVID-19 pandemic began (according to data from the U.S. Department of Education), though some of our tracking tools—described below—allow us to monitor a broader set of schools. In this report, we present our findings, and recommend suitable countermeasures that will protect students during these difficult times.

Our analysis has been holistic in nature, given that a published advertisement alone is rarely predatory. But combined with how the ad is targeted, how recruiters follow up with prospects, and a low investment by the school in actually educating its students, an ad can be the tip of the spear. Therefore calling suspicious marketing into question is a worthwhile endeavor: doing so may slow down scams, and perhaps prevent some incipient ones from developing altogether.

As we shall see, some of the marketing schemes we analyzed were remarkably concerning. One such marketing strategy found online even led TCF’s Yan Cao and Anthony Walsh to file a complaint with the Federal Trade Commission. The complaint involves a “best” colleges website, and similar sites that appear, at first, to offer objective ratings of colleges. However, the sites push recommendations to users that appear to be based on the site receiving a referral fee from the college. More commonly, several colleges made specific claims about their programs without providing adequate explanation of the claim. For example, one claimed that its units “transfer easily” to another school while another said its students are twice as likely to graduate.

TCF is following up on these and other suspicious claims by contacting the colleges and, as appropriate, accreditors and regulators. We invite anyone who comes across any concerning college ad or marketing strategies to email a screenshot or photo to [email protected].

Unless otherwise noted, the data and analyses presented below are all original research.

Pandemic-Themed Ads: Most Colleges Don’t Have Them, but Some Do

Through databases of display advertisements,4 Google pay-per-click advertisements,5 and Facebook advertisements, we examined colleges whose marketing shifted to a focus on the pandemic, which we classify as new advertisements using terminology characterized by the pandemic or promoting programs for jobs deemed essential during the pandemic. With this classification in mind, we analyzed the Google and Facebook advertisements of the top 100 schools by online enrollment for February through May 2020. We also used this classification to find overt use of the pandemic in display advertisements found across the Internet. While most schools are not using the pandemic overtly as a marketing angle, some are doing so indirectly, by referencing COVID-19, social distancing, and staying at home, or by alluding to “uncertain times.”

Eighty-five of the top 100 online schools (by enrollment) make use of Google search pay-per-click advertising. Of these eighty-five colleges, a small minority of them have used the pandemic as a marketing angle—eight, to be exact. Some of these campaigns began advertising under new, pandemic-themed search terms, while others altered the advertisements themselves to be pandemic-focused. Perhaps the most overt shift was schools starting to run ads under keywords associated with the health-care field even when the programs advertised had no connection with health care. In all of the cases, they did so for the first time. For instance, Oregon State University began running ads under search terms that include the word “respiratory” for the first time in its Google advertising history. As a control, it merits mention that many of the schools in our top 100 have run ads under terms like respiratory therapy in the past, and unsurprisingly have maintained those and similar ads throughout the pandemic; but these eight schools were not among them.

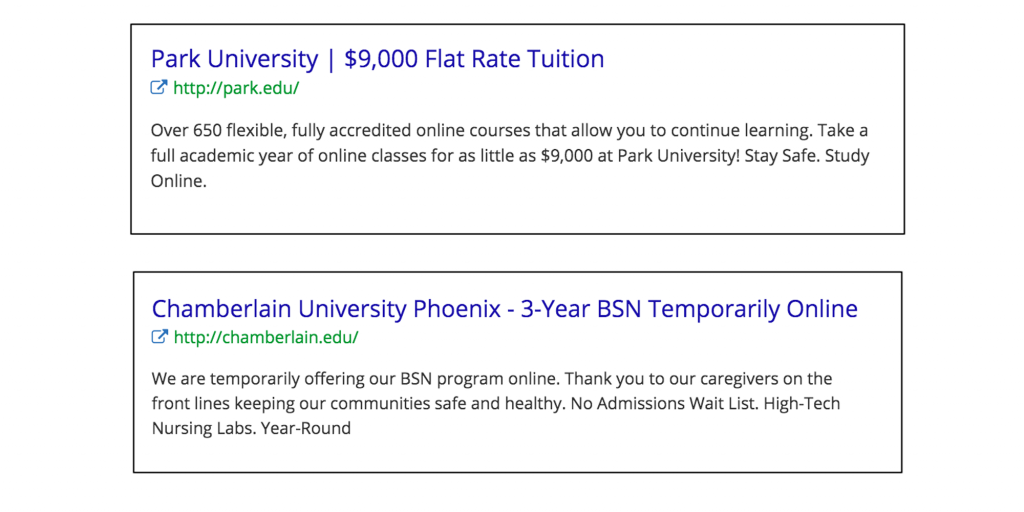

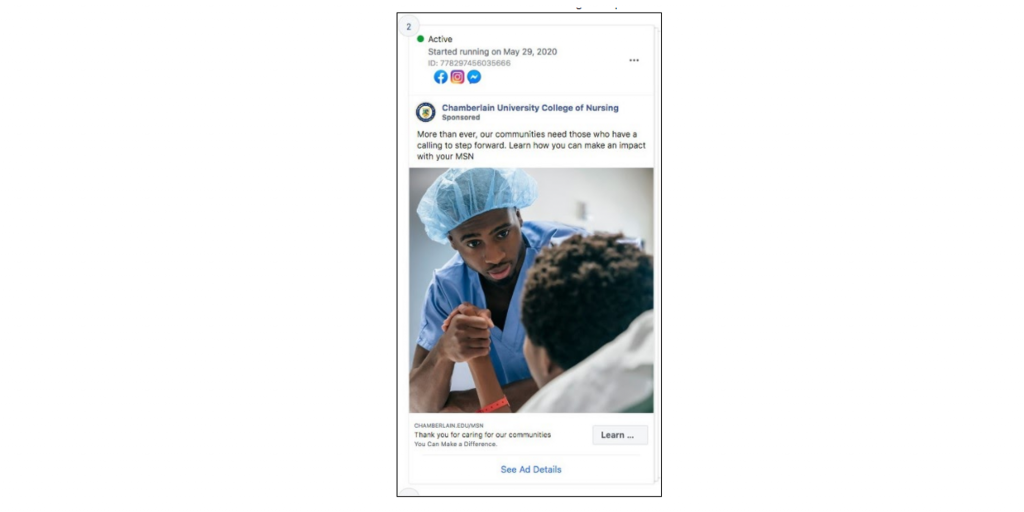

Less overtly, colleges have altered the body of their ad content to include themes associated with the pandemic. As seen from other colleges on other advertising platforms, Park University’s Google ad content began including the phrase, “Stay safe. Study online.” Indiana Wesleyan University’s Google ad content began including variations of: “Now, more than ever, our communities need public health officials,” and, “Be a leader in the essential sector of public health,” in a draw to pull in prospective health industry students using the theme of being “essential” that has dominated public discourse. Nova Southeastern’s ads also used the pandemic’s uncertainty in hopes of attracting students: “In These Uncertain Times, Healthcare Professionals are in Demand.” Similarly, Chamberlain University’s ads began including the phrases, “Until it’s safe to go on campus,” and, “Thank you to our caregivers on the front lines keeping our communities safe and healthy,” as well as, “Step forward to serve your community.”

We found similar shifts to pandemic-themed advertising in our analysis of Facebook and display advertisements. As with Google advertising, a minority of schools used pandemic-themed and hyper-current language like “essential” and “stay home” in their Facebook and webpage display advertising.

Pandemic-themed display advertisements primarily sought to pull in would-be students through messaging around uncertainty. Schools from all sectors are getting mileage out of referencing “uncertain times” months into the health and economic crisis. In April, private university Nova Southeastern ran, “Even in uncertain times, you can still advance your career.” In May, public university CUNY School of Labor & Urban Studies went with, “Even in uncertain times, an education is forever.” And in June, for-profit college Ultimate Medical Academy ran, “Face uncertainty with a plan. When stay at home means start your future with an online healthcare program.”

Other advertising with messaging on uncertainty in the future included: “Education is job security” (Utah State University), “Life may seem uncertain, but your future is not on hold” (Portland Community College), and, “In a world of uncertainty, your next move doesn’t have to be” (Eastern Gateway Community College).

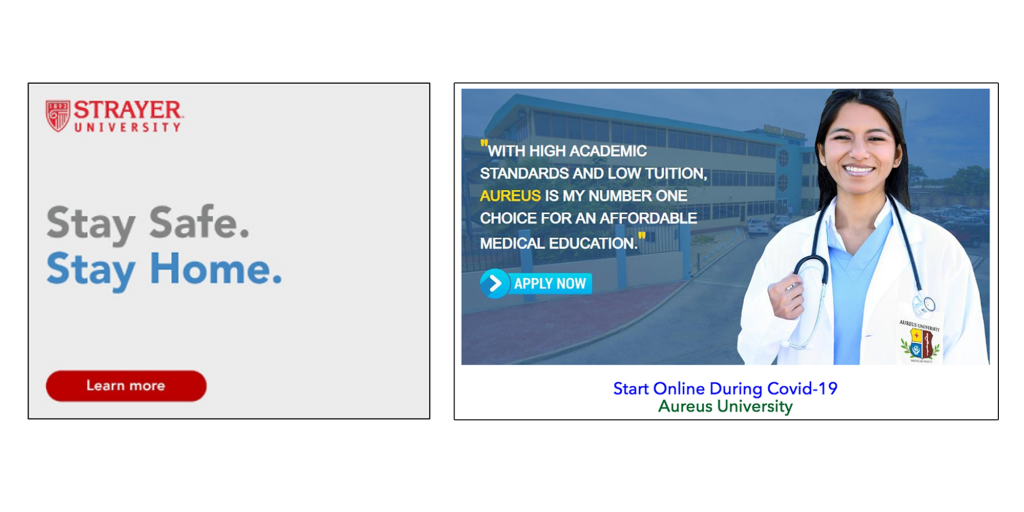

At the start of May, for-profit college American College of Education began running several Facebook ads with the messaging, “Stuck at home? Why not get ahead?”, while another for-profit college, Colorado Technical University, started using a “stay home” slogan to push its online courses. American Public University (also for-profit despite its name) started running ads targeting displaced students asking, “Did the coronavirus pandemic disrupt your undergraduate college studies? Get back on track with 50% tuition, up to 2 undergrad courses at APU.” In April, Strayer University also started running webpage display ads promoting their online courses with the messaging, “Stay safe. Stay home.” Aureus University School of Medicine, located in Aruba (and one of a number of offshore medical schools), started running ads that explicitly encouraged students to “Start Online During Covid-19.”

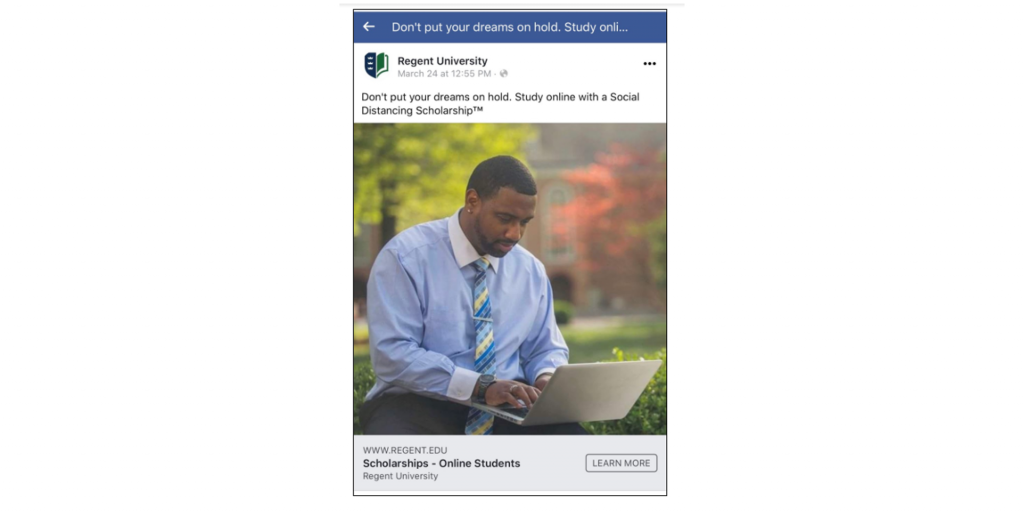

Some colleges have started promoting scholarships and discounts directly affiliated with the pandemic. Regent University ran display and Facebook ads promoting a “Social Distancing Scholarship,” that was only available for a limited time in April. In April, Purdue University Global began running Facebook ads for free three-week trials of its IT and health care program courses, as well as advertising a free contact-tracing course.6

Some colleges have also started more heavily advertising programs related to jobs deemed essential. Among all the ads we analyzed that ran between mid-April and mid-July for degree programs, nearly half (44 percent; 885 out of 2,000) were for health care programs.7 From April to May, eight of the ten largest college advertisers in our study started running for the first time, or more frequently, ads for health care programs. Columbia University, the third-largest higher education display advertiser in May, spent $75,300 on one ad alone about switching careers to health care. Since April, Northeastern University has been promoting8 becoming “a leader in public health—on your schedule.”

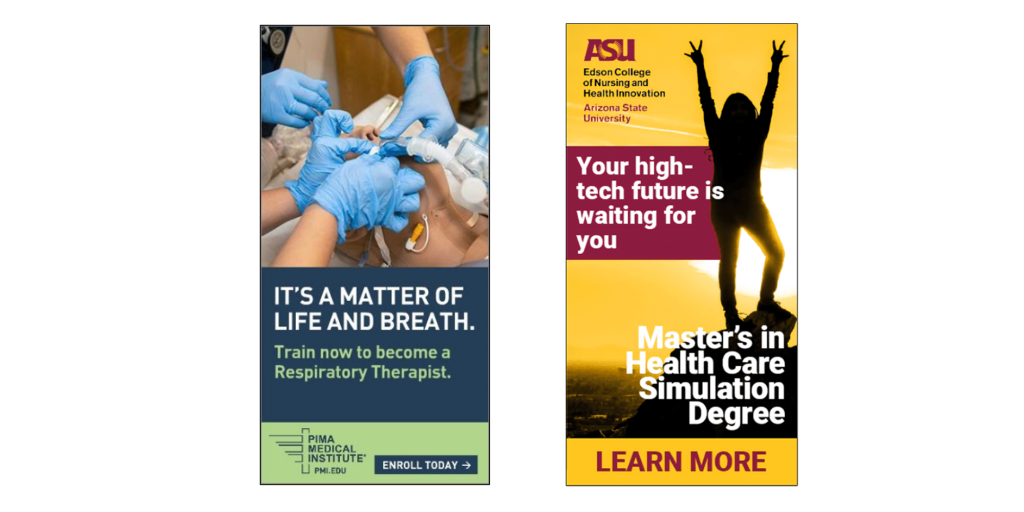

Since April, for-profit Pima Medical Institute, along with six other institutions, have started running display advertisements for the first time in their advertising history for respiratory therapist programs. University of Cincinnati’s display ads for the month of May were almost exclusively for programs corresponding with pandemic-related fields: IT, nurse, respiratory therapy, medical billing and coding, family nurse practitioner, and health administration. University of Cincinnati was also the largest college display advertiser between April and May, spending an estimated $620,400.

Arizona State University, the seventh largest display advertiser in May, started running multiple ads in April for its master’s in health simulation, asserting, “Your high tech future is waiting for you.”

In May, George Washington University rose in our data set to one of the ten largest display-ad college advertisers for the first time, and its most expensive ad, spanning February through May, was a mobile ad for its master’s and doctoral nursing programs. This ad, costing an estimated $41,800 since it started running at the end of February, ran most frequently in March and April.

For-profit nursing school Chamberlain University changed its set of Facebook ads from mostly images of smiling students and graduates in March entirely to images of health care professionals in April and May, promoting its programs with compelling messages like, “More than ever, our communities need those who have a calling to step forward.”

How We Are Monitoring College Marketing

Like most businesses, colleges market through a variety of mediums. In addition to the old, traditional forms of advertising like TV and radio commercials, and ads on billboards, transit, and print media, colleges place advertisements across various online platforms. Some colleges pay search engines, such as Google, to have advertisements appear alongside search results. Colleges can also pay to place ads directly on web pages: these are known as display or banner ads, and are pictures or videos that appear in various places on a webpage. Social media platforms like Twitter, Snapchat, and Facebook are also widely used for digital advertising.

A less overt but frequently used form of advertising is to pay websites to promote colleges with their own content, or to contract with companies that collect consumer information and then disseminate that information for marketing purposes. In the case of the former, these affiliate sites and lead generators often pose as neutral college information sites offering to provide consumers with recommendations based on stated interests, but in reality only feature institutions that have paid to be featured. In both cases, the relationships are, by their nature, harder to track or verify, and so we are not at this time pursuing any systematic monitoring of them. However, we currently have the capability to monitor Google advertising, display advertising, and some aspects of Facebook advertising. We describe our monitoring processes below.

Search Engine Marketing

The Century Foundation is monitoring search engine marketing through Spyfu,9 a paid service that tracks advertising on Google’s search engine results pages. We used Spyfu’s data on keyword and pay-per-click advertising to identify college ads placed under Google search terms and the estimated cost of these ads. Keyword advertising data come from Spyfu-generated screenshots of the first two search engine results pages of every google search in its database. Data on ad spend and keyword usage come from Spyfu analysis of Google keyword data. These data are updated by Spyfu on a monthly basis. Table 1 shows the type of information available from Spyfu.

Table 1

| Highest Estimated College Spenders on Google Ads in March 2020 | ||

| Institution | Estimated per-pay click costs for March | Of note |

| University of Phoneix | $1,970,00 | The company’s highest-worth search term was “business degree online,” costing/averaging $68.79 each time someone clicked on the ad that appeared in that Google search. Next was “criminal justice online colleges,” $54.17. |

| Western Governors University | $1,970,00 | This school’s ad spending emphasized nursing degrees. For various permutations of searches for “online teaching degrees” the school appeared #1 in the non-ad search results. |

| Arizona State University | $1,760,00 | ASU got more clicks from “university online” searches than any other single search term |

| Walden University | $1,730,00 | The company paid $47.22 per click to get the #1 ad position for the search term “online social work degree.” |

| Liberty University | $1,710,00 | This college got the top ad position for “online bible college” for $10.43 per click and “christian university” for $4.73 per click. |

| DeVry University | $1,660,00 | For the past 15 months straight, the owners of DeVry University have been paying to get the #1 ad position for “medical coder jobs” |

| American Public University System | $1,490,00 | The company’s purchased search terms are heavily oriented toward military and veteran students. |

| Grand Canyon University | $1,450,00 | The for-profit contractor that runs GCU paid an estimated $148 per click for an ad in searches for “rn to bsn online programs” |

| Strayer University | $1,260,00 | The company had the #1 ad on searches for “free online school,” and “online school free,” terms it started paying for last September. |

| Maryville of Saint Louis | $1,250,00 | The top ad seen by people who searched “cyber security” was for Maryville’s online degrees in that subject. |

| Source: TCF compilation of Google data analyzed by Spyfu.com for the 100 largest online colleges (by enrollment). | ||

Display Advertising

TCF is using a subscription with Adbeat10 to monitor college advertising across the Internet’s websites. Using Adbeat’s data on display advertising, collected hourly and daily through server-generated web scans, we are able to see estimated ad spending, marketing campaigns, and websites where ads are placed, as well as ads themselves, over a given period of time. Ad spend is estimated through an Adbeat algorithm using a broad sample of advertisers and ads over the past seven years.

TCF analyzes of display advertising make use of Adbeat’s advertiser categories, groupings of top advertisers, advertisers with the largest changes in ad spending, and top advertisements. Using these groupings for Adbeat’s “college” category, we are able to identify what colleges are spending on display advertising, aggregated over a period of time or broken out by specific advertisement. Adbeat’s grouping of top advertisements presents ads by most to least expensive and can be filtered by user-chosen terms, which allows us to look for colleges advertising with particular themes. Adbeat does not reveal its advertiser categories criteria nor its algorithm for identifying ad spending. Table 2 shows the kind of information available from Adbeat.

Table 2

| Colleges with the largest display advertisement spending from March through May | ||

| Institution | Estimated display ad from March through May | Of note |

| Strayer University | $9,500,000 | Strayer’s estimated weekly ad spend went up from $620,600 to $2.6 million between July 5 and July 12. |

| Purdue University and Purdue University Global11 | $8,800,000 | An ad for a PUG nursing program is one of the top college advertisements from March through June, costing over $147,000. |

| Western Governors University | $1,600,000 | WGU’s largest ad placement site is Youtube, costing $1.3 million from March-June and featuring ads most frequently on hip hop, pop, and Latin music videos. |

| Columbia University | $1,400,000 | Columbia’s top ad since January promotes making a career change to medicine. This ad cost $75,300 and ran more in April than in other months. |

| University of Cincinnati | $1,400,000 | The bulk of UC’s new ads in the last 90 days are for STEM programs, despite that UC offers programs in at least ten other areas of study. |

| Arizona State University | $1,100,000 | ASU’s most expensive ad campaign from March through June has been for its online health degree programs. |

| New York University | $904,300 | During June alone, Adbeat estimates that NYU has spent nearly $500,000 more on advertising compared with June of last year. |

| Grand Canyon University | $891,000 | GCU’s top five ads from March through June feature only women. |

| Chamberlain University | $801,900 | Chamberlain’s top ad placement site is Youtube, costing $918,700 and placing ads almost entirely on children’s videos. |

| Source: TCF compilation of Adbeat data. | ||

Social Media Marketing

Social media sites restrict access to data on advertiser spending, so this form of advertising is the most difficult to monitor. However, Facebook allows the public to see all current ads being run on Facebook and Instagram through its Facebook Ad Library.12 With this tool, we are able to see how long advertisements have been running and when new ads appear, but we cannot see ad cost, where ads are running or target audience, nor ads that are no longer in use. TCF is monitoring college Facebook ads of the 100 colleges with the largest online enrollments of 2018, including branches with a Facebook presence distinct from the main institution, yielding 121 schools total; of this sample, 89 had at least one Facebook advertisement between March and June 2020.

How Policymakers Can Protect Students from Predatory Marketing—and Make Information about It More Accessible

It should be underscored that an advertisement is only the tip of the iceberg. The most effective monitoring efforts account for the entirety of the student recruitment process, from the moment students are presented information to the moment they enroll.

Luckily, policymakers have options for thoroughly monitoring every stage of college recruitment. Here we present recommendations on the most effective options they have and how they should use them.

1. Limit how much colleges and universities can spend on advertising if they are using federal funds.

Simply put, colleges should spend more on educating current students than on advertising for new ones. Colleges that spend exorbitant amounts on recruiting and advertising are likely spending very little on instruction and supporting current students.13 Multiple bills introduced in Congress in recent years, including the 2020 College Affordability Act, would prevent colleges from using federal funds on marketing.14

2. Require schools to report expenditures on marketing and advertising.

Colleges already report expenditure information to the U.S. Department of Education every year, but the details on pre-enrollment expenses are buried under reporting categories that are too broad to be useful. At the moment, expenditures on marketing and recruiting are reported within a category that includes important current-student support elements; these pre- and post-enrollment expenses should be reported separately. Revision of the annual data collection known as the Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System (IPEDS) has wide support from legislators to large online colleges.15 Proponents of IPEDS revision suggest that data collection tools be updated to match the current reality of higher education, which includes large online colleges that may operate under a unique business model. Students and the public would also benefit from revised expenditure categories because of the tool’s utility for transparency.16

3. Require transparency from social media platforms.

Ad delivery platforms, such as Facebook, play a large role17 in determining how ads are distributed and shown to consumers, yet provide little information behind these processes. Facebook and other social media marketing platforms should be required to make archived information on advertisers available to the public, including how much advertisers spend.

4. Implement a federal mystery shopping program.

Much of the harm done by predatory recruiting happens in the school’s interactions with the prospective student.18 Incessant outreach, rushed enrollment processes, and promises for a more financially secure future are all part of the predatory college playbook. Mystery shopping—sometimes called secret shopping—is a tool that is commonly used by market researchers and corporations to either test their own customer service processes or those of their competitors. Some colleges that have outsourced their recruiting operations have implemented secret shopping missions to keep tabs on third-party communications to prospective students.19 This is a smart move by all colleges, but better federal oversight would include a sustained federal mystery shopping program.

A 2010 GAO investigation relied on secret shopping to test for-profit college recruitment processes to eye-opening results. All of the colleges where mystery shoppers posed as prospective students presented the prospects with “deceptive or otherwise questionable” information about the school or financial aid.20 Congress should prioritize the creation and maintenance of a mystery shopping program to keep tabs on college recruiting.

Finally, websites, television networks, and other outlets should place more scrutiny of what they allow to be advertised. Civil rights organizations recently called on advertisers to abandon their Facebook ad campaigns in an effort to call attention to the platform’s facilitation of hate and disinformation.21 Advocates and activists concerned with predatory colleges and student debt should lead a similar campaign to pressure outlets to scrutinize their advertisers. One media site announced last year that it would no longer take ad dollars22 from companies that don’t align with its values, among them for-profit colleges.

Our Next Steps In Monitoring College Marketing—We Need You!

While we have found tools to do some of this monitoring, there are gaps that will need to be filled with crowdsourced information, feedback, and assistance from grassroots allies and informants. Take screenshots, click on ads and see what happens, take notes of any calls from recruiters and let us know what you discover by emailing [email protected].

Notes

- Coronavirus Coverage, series, Inside Higher Ed, https://www.insidehighered.com/coronavirus.

- See TCF’s series of reports, The Cycle of Scandal at For-Profit Colleges, for an historical overview: https://tcf.org/topics/education/the-cycle-of-scandal-at-for-profit-colleges/.

- Collin Binkley, “While other colleges struggle, for-profits hope for revival,” Associated Press, April 19, 2020, https://apnews.com/ef35d2a42e611b6a379927628d214071.

- Display advertisements are designed images that advertisers pay websites to run on their webpages. See “methods for monitoring college advertising” below for more definitions and details on how we are tracking college advertising.

- Colleges pay to appear under particular search terms in hopes of driving prospective students to their websites. Such advertisements appear alongside unpaid Google search results.

- COVID-19 Contact Tracing Course, https://www.purdueglobal.edu/covid-19-contact-tracing-course/.

- TCF calculations of Adbeat data on top advertisements, filtered for ads featuring the terms “degree,” “healthcare,” “RN,” “BSN,” “MSN,” “CCNE,” and “nursing.”

- Advertisement seen on Moat’s display ad database, https://moat.com/creative/9de006311eecf4a9c6bace963323a59b?region=US.

- Spyfu, https://www.spyfu.com/

- Adbeat, https://www.adbeat.com/.

- Most of the ads categorized by Adbeat as Purdue University are for its Purdue Global subsidiary, operated in conjunction with for-profit Kaplan Higher Education.

- Facebook Ad Library, https://www.facebook.com/ads/library/.

- Stephanie Riegg Cellini and Latika Chaudhary, “Commercials for college? Advertising in higher education,” Brookings Institute, May 19, 2020, https://www.brookings.edu/research/commercials-for-college-advertising-in-higher-education/

- In the Senate, S.3752 was introduced by Senator Sherrod Brown and in the House of Representatives, Representative Grijalva introduced H.R. 7303. Both bills would restrict the use of federal funds on marketing activities. The 2020 College Affordability Act would restrict colleges that fail to spend a minimum amount on instruction from spending federal funds on marketing.

- In 2019, large online colleges University of Maryland Global, Western Governer’s University, Southern New Hampshire University, and Capella University sent a letter to the Education Department urging revision of data collection to reflect instructional costs for distance education modes. On December 26, 2019, Representative Mark Takano (D-CA) sent a letter to the director of the Integrated Postsecondary Data System proposing these changes. The 2020 College Affordability Act would require the Secretary of Education to define expenditures on marketing, recruiting, advertising, lobbying, and student support for annual IPEDS data collection.

- Stephanie Hall, “How Much Education Are Students Getting for Their Tuition Dollar?”, The Century Foundation, February 28, 2019, https://tcf.org/content/report/much-education-students-getting-tuition-dollar/.

- Muhammad Ali et al., “Discrimination through optimization: How Facebook’s ad delivery can lead to skewed outcomes,” (September 2019): https://arxiv.org/pdf/1904.02095.pdf.

- Tressie McMillan Cottom. Lower Ed: The Troubling Rise of For-Profit Colleges in the New Economy (New York: The New Press, 2017).

- Lindsay McKenzie, “Checking on Vendors,” Inside Higher Ed, February 8, 2018, https://www.insidehighered.com/news/2018/02/08/universities-use-secret-shoppers-make-sure-outsourced-services-meet-standards.

- U.S. Government Accountability Office, “FOR-PROFIT COLLEGES: Undercover Testing Finds Colleges Encouraged Fraud and Engaged in Deceptive and Questionable Marketing Practices,” August 4, 2010, https://www.gao.gov/products/GAO-10-948T.

- Rebecca Heilweil, “Civil rights organizations want advertisers to dump Facebook,” Vox, June 17, 2020. https://www.vox.com/recode/2020/6/17/21294451/facebook-ads-misinformation-racism-naacp-civil-rights.

- David Bloom, “The Young Turks Says It Will Turn Down Advertisers That Don’t Fit Its Values,” Forbes, June 20, 2019, https://www.forbes.com/sites/dbloom/2019/06/20/the-young-turks-says-it-will-turn-down-advertisers-that-dont-fit-its-values/#71f88c6f2b65.