Patricia McGee was living in the Mandalay Palms Apartments in a rough section of Dallas a few years ago when one day her ten-year-old son said, “Momma, look.” McGee peered out the window and saw a sex worker hanging out at the bus stop in front of the apartment “doing some things she shouldn’t be doing.”1 McGee was horrified. “Your kids, they pay attention to everything,” she says. They began “talking about stuff they ain’t got no business talking about,” she says.2

McGee, who had grown up poor, wanted something better for her kids. But she felt trapped. The safer neighborhoods with good schools were off limits. For decades, Dallas and its suburbs had enacted a series of policies—redlining, racially restrictive covenants, and de jure school segregation—designed to keep Black people like McGee and her children out of wealthier, white neighborhoods.

Now, even as explicit racial discrimination by landlords, racially restrictive covenants, and redlining had all been outlawed, new, less visible barriers prevented McGee and her children from enjoying better opportunities. Economic zoning laws that prohibit the construction of more affordable types of multifamily housing in entire regions and other exclusionary practices were keeping people like McGee physically separated from opportunity. And while a landlord could no longer lawfully discriminate against McGee because of her race, a landlord in Texas could legally deny a tenant an opportunity based on her source of income—the fact that McGee would pay her rent in part with a government-funded Section 8 Housing Choice Voucher.

McGee was deeply discouraged. She explains: “Living in Mandalay was one of the worst areas I have ever lived in. It was prostitution at the bus stop. It was drug-smoking in my breezeway where my door was. . . . Every time you turned around, there was some crime.”3 Then, while searching for ways she could get assistance putting together a rental security deposit, she came across a program sponsored by the Inclusive Communities Project (ICP), a nonprofit organization dedicated to fair housing and upward mobility.4

With ICP’s help, McGee was able to move to a house in Forney, Texas, a prosperous city twenty miles east of downtown Dallas, with strong schools and a safe environment. “I love it out here,” McGee said in an interview in 2020. “I don’t have to worry about people standing all outside my yard, smoking and [playing] loud music and all kinds of stuff. It’s real quiet out here.”5 The ICP program worked well for McGee, but is relatively small: 350 families benefit per year in a region of 7.6 million residents, many of whom are low-income wage-earners like McGee.6

This report outlines the state-sponsored barriers low-wage workers face when trying to move to homes in safer neighborhoods with good schools in the Dallas area—barriers that are common throughout the United States. It tells the struggle of people like Patricia McGee, who want a better life and strive to join and contribute to thriving neighborhoods, but are shut out by government policies. And the report discusses some promising federal and state approaches to tear down government-sponsored walls that do so much harm.

The Social Engineering of Segregation by Race and Class

Many think someone like Patricia McGee can’t afford to live in the suburbs because, under the free market system, some communities tend naturally to have bigger houses—people flee the city because they want more room, which means a big house and a big yard, and these things simply cost more money. But the truth is much more complicated. In Dallas—as in other parts of the country—a series of deliberate public policy choices were made throughout the city’s history in order to place barriers in the paths of low-income families and families of color who sought out better places to live, and these barriers have not disappeared but rather have evolved over time.

In the early and mid-twentieth century, Dallas-area officials enacted or followed a series of racially discriminatory policies and practices in housing and schooling: racial zoning laws, enforcement of racially restrictive covenants, redlining, state tolerance of white terrorism, and de jure segregation of schools. Following the enactment of the Fair Housing Act of 1968, many of these policies and practises were deemed illegal, so discrimination took on new forms: racially and economically discriminatory placement of public housing, proliferation of exclusionary zoning laws, and state legislation to ban local efforts to promote inclusionary zoning and protect against source of income discrimination.

Blatant Racial Discrimination Prior to the 1968 Fair Housing Act

In the early twentieth century, to prevent Black people from moving into white residential areas, Dallas adopted a law that explicitly zoned communities by race, notes Richard Rothstein in his book, The Color of Law.7 The racist intent of such laws in Dallas, Baltimore, and other communities was very clear, as Baltimore Mayor J. Barry Mahool stated in support of his city’s 1910 racial zoning ordinance: “Blacks should be quarantined in isolated slums in order to reduce the incidence of civil disturbance, to prevent the spread of communicable disease into nearby white neighborhoods, and to protect property values among the white majority.”8 When the U.S. Supreme Court struck down such laws as a violation of the Fourteenth Amendment in 1917, whites in Dallas and throughout the country adopted racially restrictive covenants, which prevented homebuyers from later selling a house to Black buyers, a practice that survived until 1948.9

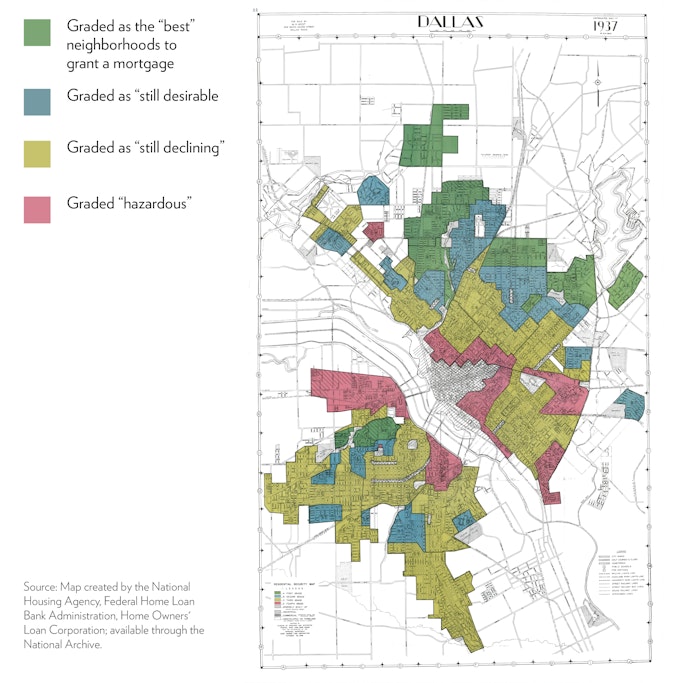

The federal government also famously “redlined” predominantly Black communities in Dallas and elsewhere, meaning that it refused to insure housing mortgages in these neighborhoods, yet continued to insure mortgages in predominantly white areas. (See Map 1 for the redlined neighborhoods in 1937.)

MAP 1. REDLINING IN DALLAS, TEXAS, 1937

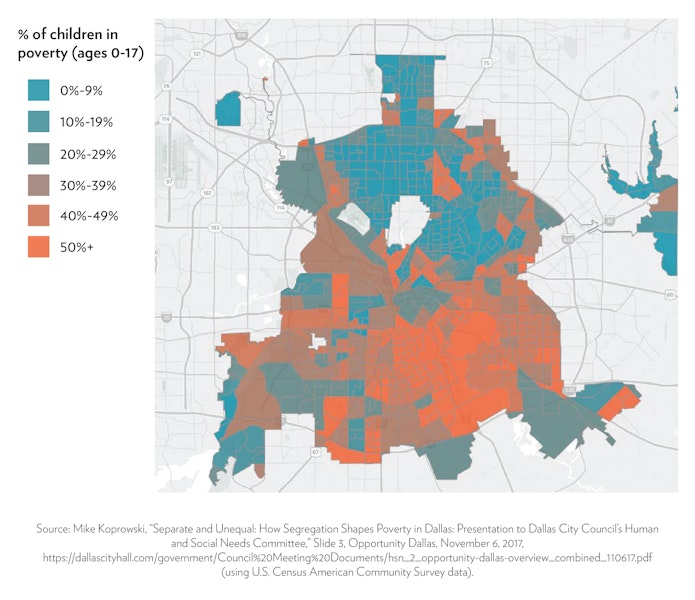

Although redlining was outlawed by the 1968 Fair Housing Act, its impact lingers to this day. A contemporary map of Dallas showing where poverty is currently concentrated overlaps considerably with the redlining maps of almost a century ago. (See Map 2.) As journalist Jim Schutze notes, “The two maps, the 1937 redline map and today’s map of extreme poverty in southern Dallas, [are] almost the same map.”10

MAP 2. POVERTY CONCENTRATION IN DALLAS, TEXAS

Government also conspired to keep Black people in segregated communities by looking the other way while white supremacists physically attacked Black families trying to move into white neighborhoods. In the 1940s and 1950s, whites committed “a wave of bombings of homes of middle-class Black families,” writes Schutze. Dynamite was the tool used by white people, who organized through their churches at the time.11

Housing segregation was also reinforced indirectly by the Dallas Independent School District (DISD)’s shameful practice of public school segregation by race. As in much of the South, schools in Dallas were segregated by law before the 1954 Supreme Court decision in Brown v. Board of Education; and for many years following the Supreme Court ruling, the Dallas school board balked at taking action to meaningfully desegregate.12 Likewise, predominantly white suburban towns around Dallas routinely told Black students who might be living there that they had to attend Dallas schools.13

In 1970, Black civil rights activist Sam Tasby sued the Dallas Independent School District for violating the requirements of Brown and in 1971, a federal district court judge found the district guilty of continuing to maintain a dual system of education. In the case Tasby v. Estes, Judge William M. Taylor Jr. noted that while the school district’s student population was 59 percent Anglo, 33 percent Black, and 8 percent Mexican-American, 70 of the district’s 180 schools had 90 percent or more Anglo students, and 49 had 90 percent or more minority students. Among Black students, the judge noted, 91 percent attended schools that were 90 percent or more minority, and only 3 percent attended majority-Anglo schools.14

Judge Taylor ordered desegregation with the goal that individual schools more closely mirror the district-wide racial representation.15 White resistance to the decision was fierce. In an August 1971 Dallas Morning News poll, Anglos opposed the desegregation plan 89 percent to 6 percent, while Black people favored it by 50 percent to 36 percent and the Hispanic population disfavored the plan 55 percent to 37 percent.16 When the plan was implemented, white families fled to the suburbs in large numbers. During the height of large-scale busing, in the early 1970s, DISD lost 40,000 (or 43 percent) of its Anglo students. Although the district had been losing Anglo students prior to busing, there was a five-fold increase in loss at the time of busing.17

Some integration was achieved for a time, however, and one study found that between 1980 and 1989, the achievement gap between Black and white students was reduced by more than half (from 35 percentage points to 16).18 But the school district was eventually released from desegregation, which reduced levels of integration, and in any event, white flight continued to take its toll.19 Today the district’s schools are just 5 percent white.20 The desegregation plan, wrote Dana Goldstein in the New York Times in 2017, ultimately “replaced one form of segregation with another.”21

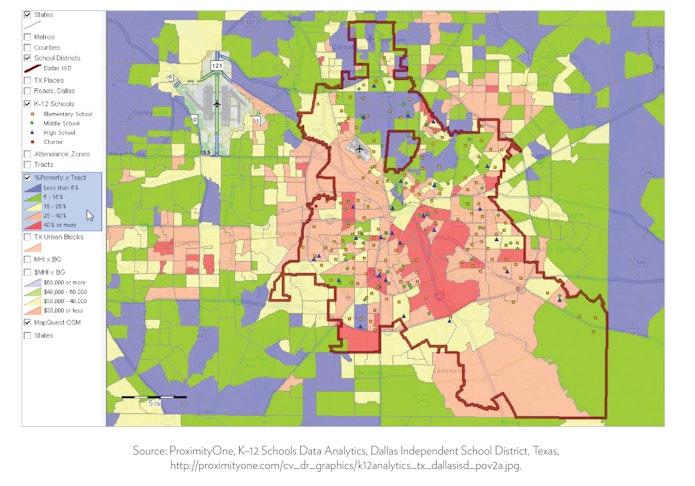

The story of Highland Park Independent School District vividly illustrates the way in which Dallas schools were segregated—and remain segregated to this day.22 Home to Southern Methodist University, the school district represents a separate enclave that sits in the middle of the Dallas public school system.23 As Mike Koprowski, a former DISD official notes, “it’s nearly all rich white people, a separate district, separate town council, separate police surrounded on all sides by the city of Dallas.” This “donut hole,” represents a “simple, stark tale,” he notes.24 (See Map 3.) The district was created in the early twentieth century, as the Highland Park town website itself notes, “as a refuge from an increasingly diverse city.”25 In the 1950s, when Texas schools were segregated by law, Highland Park sent the small number of Black students residing in the area to Dallas public schools.26 Highland Park did not have any Black homeowners until 2003.27

Highland Park Independent School District vividly illustrates the way in which Dallas schools were segregated—and remain segregated to this day. It has a student population that is 82 percent white, and a remarkable 0 percent of students are from low-income families.

Today, the district—which has five elementary schools, one middle school, and one high school (along with two alternative schools)—has a student population that is 82 percent white, 7 percent Asian or Pacific Islander, 5 percent Hispanic, 2 percent two or more races, and less than 1 percent Black, Native American, and Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander. A remarkable 0 percent of students are from low-income families.28 By contrast, in the surrounding Dallas district, 69 percent of students are Hispanic, 21 percent Black, 5 percent white, and 1 percent Asian or Pacific Islander—and 86 percent of students are from low-income families.29 “Highland Park,” says Koprowski, “is only five minutes away from the deepest concentrations of poverty.”30

MAP 3. DALLAS INDEPENDENT SCHOOL DISTRICT, WITH HIGHLAND PARK “DONUT HOLE”

Discrimination Based on Income after the Fair Housing Act, with a Racially Disparate Impact

The civil rights movement outlawed the worst forms of racial discrimination—racial zoning, racially restrictive covenants, de jure school segregation, redlining, and the most blatant forms of racial discrimination by landlords. But new forms of discrimination that focus on economic class have taken root, and these policies disproportionately hurt Black people. In Dallas, and other parts of the country, economic discrimination in the post–civil rights era has taken on three central forms: (1) government policies that concentrate low-income housing in high-poverty (mostly Black) communities; (2) exclusionary zoning laws that prohibit the construction of multifamily housing or require minimum lot sizes, effectively screening out low-and moderate-income families; and (3) state-sanctioned source-of-income discrimination by landlords against those with Section 8 Housing Choice Vouchers. Policies such as arcane zoning laws are less dramatic than the use of dynamite in earlier eras to keep Black people from moving into communities, but today’s zoning and related policies can be just as effective at perpetuating racial and economic segregation.

The Concentration of Publicly Supported Housing in High-Poverty Communities

In recent decades, the federal government has supported public housing not so much through the creation of large, publicly built housing projects as through two types of public–private partnerships: the Section 8 Housing Choice Voucher program, and the Low-Income Housing Tax Credit (LIHTC). In principle, both types of programs could facilitate desegregation because housing vouchers can theoretically be used in any community and LIHTC housing can be built in more-affluent, high-opportunity areas as well as in communities of concentrated poverty. But in Texas, as in many parts of the country, upper-middle-class communities have fought Section 8 and LIHTC-supported housing and sought to exclude low-income families. This income and race discrimination disproportionately hurts Black people, especially in Dallas, where 86 percent of the Dallas Housing Authority’s clients are African American.31

In Dallas, civil rights activists brought two landmark lawsuits—Walker v. HUD (1990), and Inclusive Communities Project v. Texas Department of Housing & Community Affairs (2010)—that exposed discriminatory behavior in the placement of subsidized housing.

In 1985, Black plaintiffs sued the Dallas Housing Authority (DHA), the City of Dallas, and HUD for furthering segregation by placing public housing in mostly Black areas in the Dallas region. At that time, a federal district court noted, “suburbs of the City of Dallas were refusing to participate in DHA Section 8 assistance program,” thereby preventing those with housing assistance from using that support anywhere in the Dallas suburbs.32 The parties reached a consent decree in 1987 to provide housing vouchers to residents living in segregated housing to move elsewhere, but plaintiffs had to go to court because of “repeated and pervasive” violations of the consent decree. As part of a 1990 consent decree,33 an organization, eventually called the Inclusive Communities Project (ICP), was founded to promote integration—including through the mobility assistance program in which Patricia McGee took part—that allows voucher holders to live in high-opportunity neighborhoods.34 The litigation continued for years as plaintiffs had to go back to court time and time again to defend and enforce their efforts to desegregate housing.35

The placement of public housing in mostly low-income Black areas had gone on for years as part of what Dallas journalist Jim Schutze called “the accommodation.

The placement of public housing in mostly low-income Black areas had gone on for years as part of what Dallas journalist Jim Schutze called “the accommodation.” The white power structure in Dallas essentially struck a bargain with a group of Black leaders that wealthy whites would try to suppress white violence against Black people if Black leaders didn’t push too hard for integration. As part of the bargain, Black leaders would be given financial control over Black segregated areas, mostly in South Dallas.36 In theory, this agreement could have led to greater investment in poor Black neighborhoods and to community revitalization, says Mike Koprowski, who has championed housing and school desegregation efforts in Dallas, but in practice, because Dallas is divided into fourteen council districts, funds are usually split equally fourteen ways, and the revitalization never fully occurred.37

The accommodation continued to hold sway after 1986, when Congress created the Low Income Housing Tax Credit (LIHTC). For years after, HUD and the Texas Department of Housing and Community Affairs concentrated tax-credit-supported low-income housing in high-poverty predominantly Black areas in Dallas rather than in whiter and more affluent areas in the suburbs. Between 1999 and 2008, LIHTC-supported Texas public housing was more likely to be approved in areas with few whites, and 92 percent of units within Dallas were located in Census tracts where fewer than 50 percent of residents were white.38

In 2008, ICP sued, charging the LIHTC policies in Texas had a negative “disparate impact” on Black people and furthered racial segregation in violation of the 1968 Fair Housing Act.39 The case went all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court, where, in 2015, the Court ruled that disparate impact cases are valid under the Fair Housing Act, a major victory for civil rights groups. At the same time, the Supreme Court remanded the case to the lower courts for final determination on the facts in Dallas.40 In 2016, the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of Texas ruled against ICP, holding that it did not properly specify a particular Texas policy that resulted in the approval of LIHTC housing more often in predominantly minority areas than white areas.41

Running parallel to the ICP case was a separate complaint filed in 2010 with HUD against the DHA alleging that it was using Community Development Block Grant (CDBG) funds, LIHTC funding, and other federal programs to concentrate public housing in Dallas’s Southern region, which is predominantly Black and poor, in a way that furthered segregation.42 In November 2013, after a four-year investigation, HUD sent a tough letter to Dallas city leaders that found that “there was a pattern of negative reactions to projects that would provide affordable housing in the Northern Sector of Dallas” and that DHA had “subjected persons to segregation” and “restricted access to housing choice.” HUD, which controls CDBG funding to Dallas, proposed the city take a number of affirmative steps to reduce segregation, including placing more public housing in whiter areas of Dallas and passing an ordinance to forbid source-of-income discrimination against voucher holders.43

Journalist Nikole Hannah-Jones noted at the time that “the Dallas findings could be big” if it represented a break from “HUD’s history,” which “has been dominated by its deference to cities and towns it funnels billions of dollars to,” including those found guilty “of violating civil rights.”44

But it was not to be. In July of 2014, Julian Castro replaced Shaun Donovan as Obama’s secretary of HUD. Castro knew Dallas Mayor Mike Rawlings from the days when Castro was mayor of San Antonio. The two had three conversations about the HUD findings after Castro took over HUD and Castro concluded that HUD had overstepped its bounds and retracted the threat to withhold funds unless Dallas complied with steps laid out in the November 2013 letter.45 Castro, says former Dallas school official Mohammed Choudhury, gave Dallas a “wrist slap.”46 Dallas Daily Observer columnist Schutze was more blunt: “In a sweetheart deal with Dallas’ mayor, Castro deep-sixed the investigation, threw his own investigators at HUD under the bus and let Dallas off with a kiss instead of a hammer.”47 In so doing, Schutze says, “he killed our best shot at overcoming racial segregation.”48

Demetria McCain, who was president of ICP when interviewed in 2020 before she subsequently became an official at the Department of Housing and Urban Development, said the pattern plays out again and again in Dallas. White elected officials, she says, are often “not motivated to open up housing to people of color who are low income.” Meanwhile, some officials of color also support placing low-income housing in communities of color to be able to say, “I got this complex built in my district.”49 Conservative advocates of “race-based NIMBYism,” McCain says, forge an unholy alliance with progressive and “well-meaning nonprofit developers” who believe they are doing the right thing by building government-subsidized housing in communities of color.50

Exclusionary Zoning

McCain says years of litigation over the placement of low-income housing has begun to bring about some modest change. Dallas suburbs such as Plano have dropped some of their explicit opposition to low-income housing and now allow it to be built with LIHTC, and will even provide a letter of support, she notes—but a bigger impediment still looms large: exclusionary zoning. “At the end of the day,” says McCain, “sometimes the [LIHTC] developers’ biggest challenge is that the deal is killed because of zoning.”51

Researchers find that one of the most powerful impediments to racial and economic integration of communities nationally is exclusionary zoning, such as policies that ban multifamily housing or require large minimum lot sizes for homes. A landmark 2010 study of fifty metropolitan areas by Jonathan Rothwell of the Brookings Institution and Douglas Massey of Princeton University found that “a change in permitted zoning from the most restrictive to the least would close 50 percent of the observed gap between the most unequal metropolitan area and the least, in terms of neighborhood inequality.”52

The ugly origins of exclusionary zoning policies are based in racial discrimination. As noted above, Dallas was among the cities that adopted explicit racial zoning in the early twentieth century to forbid Black people from living in white neighborhoods.53 After the U.S. Supreme Court declared such laws illegal in the 1917 case of Buchanan v. Warley, white officials quickly switched to economic zoning, which banned multifamily housing that might be affordable to Black people. “Such economic zoning was rare in the United States before World War I,” author Richard Rothstein notes “but the Buchanan decision provoked urgent interest in zoning as a way to circumvent the ruling,” a ploy that is used to this day.54

Texas’s largest metropolitan areas “have a long history of exclusionary zoning,” notes University of Texas at Austin law professor Heather Way.55 In the Dallas area, “exclusionary zoning is a big problem” Mike Koprowski says.56 Within Dallas itself, 65 percent of residential land is dedicated to single-family homes.57 In the suburbs, the problem can be worse. Says Miguel Solis, a former school board member who headed a local housing task force: “it’s like the wall of Troy around some of these communities of privilege.”58

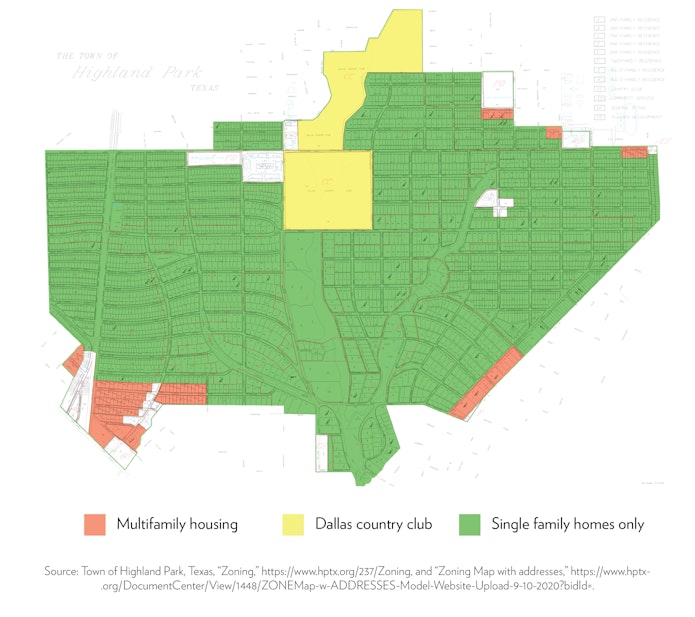

In Highland Park, for example, the affluent “donut hole” within Dallas, only a tiny sliver on the outskirts of the community is designated for multifamily housing.59 Such housing is banned anywhere else in Highland Park. In fact, more land is allocated for the Dallas Country Club than for multifamily housing. (See Map 4.)

MAP 4. HIGHLAND PARK ZONING MAP

Perhaps the quintessential example of exclusionary zoning in the Dallas area is the town of Sunnyvale, which has been the subject of extensive litigation over its zoning rules.60 Sunnyvale is an affluent community located twelve miles East of Dallas’s central business district—“just a hop skip and jump,” McCain noted.61 Nestled on the shores of Lake Ray Hubbard, it had a median household income of $132,488 in 2019, more than twice the median household income of Texas residents as a whole.62

In the 1990, as litigation over exclusionary zoning was beginning, Sunnyvale was 94 percent white and just 1 percent Black.63 Back then, the town had a complete ban on townhouses and apartment buildings and a minimum lot size for single-family housing of a whopping one acre.64 A pamphlet aimed at businesses that might want to locate in Sunnyvale, “made clear that the only type of housing allowed in Sunnyvale is low-density, single family housing. The apartments, presumably for the workers, are in other cities,” such as “Garland, Mesquite, and Northeast Dallas,” a federal court later noted.65 In 1985, Sunnydale refused to permit any Section 8 housing as requested by the Dallas Housing Authority, claiming such housing would pose challenges to providing sewer and water services.66

In 1988, Mary Dews, a counselor for the Dallas Tenants’ Association, filed suit against Sunnyvale for its exclusionary zoning laws, and was soon joined by a real estate development corporation that wanted to develop affordable multifamily housing in the town by 1995.67 In 2000, a federal district court found Sunnyvale’s exclusionary zoning laws violated the Fair Housing Act’s disparate treatment (intent) and disparate impact (effects) provisions.68 The Fair Housing makes it illegal to “refuse to sell or rent…or otherwise make unavailable or deny, a dwelling to any person because of race, color, religion, sex, familial status or national origin.” While local governments don’t typically rent or sell apartments, zoning laws can run afoul of the prohibition to “otherwise make unavailable or deny” dwellings on the basis of race.69

The federal district court found that the ban on multifamily housing, and the one-acre lot minimum, “produces racially discriminatory effects by increasing the cost of housing in the Town. By raising the cost of entry into Sunnyvale, the Town has imposed a barrier that cannot be overcome except by a token number of black households.”70

Sunnyvale argued that its exclusionary zoning was justified “for the purpose of protecting the public health with septic tanks” and to promote “environmental protection.”71 But the court rejected these arguments as pretexts for discrimination and noted, in any event, that less discriminatory alternatives exist for furthering those goals.72 The court enjoined Sunnyvale from implementing its zoning practices, and required the town to take steps to encourage the development of multifamily housing.73

In 2005, an agreement was reached between the parties to make some units available for low- and moderate-income families.74 But even after the court order, the city resisted, said McCain.75 The litigation dragged on and on for years, and it was not until 2014, some twenty-six years after the litigation began, that a set of affordable multifamily units, Riverstone Trails Townhomes, opened its doors. Even then, said McCain, Sunnyvale put the homes “on the outskirts of Sunnyvale, as far on the boundary as possible.”76

Low-income families didn’t know about the opportunity to live in Riverstone Trails, so ICP advertised it to Section 8 Housing Choice Voucher holders. It was unknown how many low-income families would apply. In the end, said McCain, “They responded at a level that was so great that the property manager had to rent a hotel room to take applicants.”77

Across the country, from California to Oregon, and from Minneapolis to Charlotte, states and municipalities are ending their bans on multifamily housing.78 But Schutze says the Dallas area is different. “What they did in Minneapolis about single family housing could never happen here” he says. “Not for a long time.”79

Indeed, in 2005, state legislators in Texas passed a law that forbids localities from adopting “inclusionary zoning” laws that mandate developers set aside a portion of new developments for low- and moderate-income households.80 Inclusionary zoning is used in many parts of the country to provide workforce housing and promote economic and racial integration. Texas is one of just a handful of states to forbid mandatory inclusionary zoning.81

In Texas, localities can still pass voluntary inclusionary zoning laws in which builders can choose to set aside units for low- and moderate-income households in exchange for the ability to build more units—a so-called “density bonus.”82 But McCain said there have been few takers.83 The reason, says columnist Schutze, is that developers are so powerful in the Dallas area that they can usually build what they want without any concessions. When Schutze wrote a column saying that voluntary inclusionary zoning seemed like a “win-win” because the community gets affordable housing and the developer gets a density bonus, a builder called him to set him straight. Under voluntary inclusionary zoning, “we would have to give up square footage to affordable [units] to get what we want” the developer said, when in fact, “what you don’t understand is we get every goddamn thing we want now, and we don’t give up anything.”84

Source-of-Income Discrimination

As some affluent white communities in Texas have opened the door to some multifamily housing, they have shifted to another tool as the “primary defense to enforce segregation,” says Schutze: outright discrimination against Section 8 Housing Choice Voucher holders.85 While it is illegal for a landlord to openly discriminate based on race, Texas communities do not protect Section 8 voucher holders like Patricia McGee against source-of-income discrimination.

In nineteen states, such as New York, California, Washington, Maryland, and Massachusetts, it is illegal for a landlord to discriminate based on a renter’s source of income.86 Austin, Texas passed such an ordinance, but in 2014, the Texas legislature preempted all local source-of-income discrimination laws, removing source-of-income discrimination protection in the state.87 Texas and Indiana are the only two states that have taken such a draconian step.88

In nineteen states, such as New York, California, Washington, Maryland, and Massachusetts, it is illegal for a landlord to discriminate based on a renter’s source of income.

As a result, source-of-income discrimination is rampant. According to a 2020 Inclusive Communities Project survey of landlords in Collin, Dallas, Denton, and Rockwall counties, 93 percent said that they would not accept voucher holders.89 The whitest areas were the most likely to refuse vouchers.90 If you have a voucher and are looking for an apartment in a high-opportunity neighborhood, Koprowski says, “you’d have to call so many landlords to find the magical one who actually accepts the voucher.”91

Lasting Damage of these Exclusionary Practices

Exclusionary practices that discriminate by income—and indirectly, by race—are taking a significant toll on Dallas residents. As outlined below, these practices feed economic and racial segregation, which inhibit upward mobility; artificially drive up housing prices, making homes less affordable for everyone; and spur urban sprawl, which does environmental damage to the region not to mention planet.

High Levels of Segregation and Low Levels of Social Mobility

Research consistently finds that exclusionary zoning increases economic and racial segregation.92 For example, 2014 research from Douglas S. Massey and Jacob Rugh finds that metro areas with less-restrictive zoning tend to have less racial segregation. The authors find, “the more restrictive the density zoning regime [the stricter the limits on residential density], the higher the level of racial segregation and the less the shift toward integration over time”93

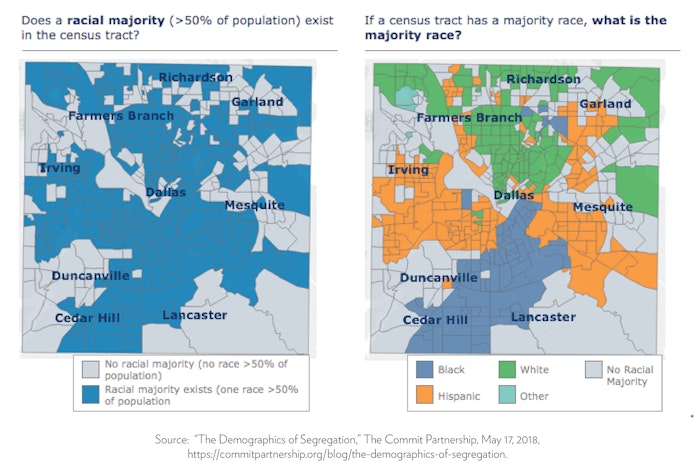

Levels of economic and racial segregation in Dallas are high. White people are largely congregated in the North, Black people in the South, and Hispanic Americans on the outskirts; and income tends to track race.94 (See Map 5.)

MAP 5. RACIAL SEGREGATION IN DALLAS COUNTY

A 2015 study by Richard Florida of the University of Toronto found that Dallas–Fort Worth was the seventh most economically segregated large metropolitan region in the entire country.95 Ninety percent of kids in poverty live in just half of Dallas’s census tracts.96

Dallas’s income segregation is mirrored in racial segregation. According to a Pew Research analysis in 2015: “Of the 306 majority lower-income census tracts in the Dallas–Fort Worth area, 83% are predominantly non-white. Meanwhile, 95% of the 108 majority upper-income tracts are predominantly non-Hispanic white.”97

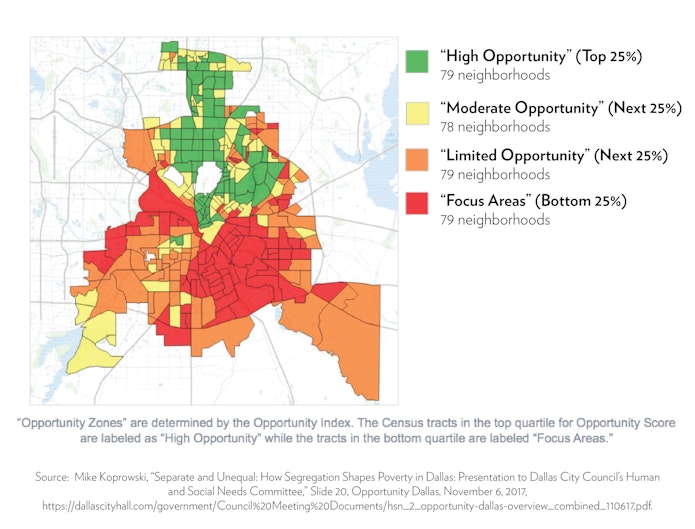

In 2017, Opportunity Dallas, a local nonprofit headed by Mike Koprowski, created an Opportunity Index for neighborhoods based on a variety of factors, including median household income, poverty rates, school performance, crime levels, and access to jobs.98 The group found that seventy-three of seventy-nine “high opportunity” neighborhoods were majority white, and not a single high-opportunity community was majority Black or majority Hispanic. On the other end of the spectrum, seven of ten majority-Black areas are “focus” areas, meaning they are in the bottom quartile of opportunity. (See Map 6.)

MAP 6. OPPORTUNITY ZONES IN THE CITY OF DALLAS

In the most recent analysis, a September 2020 Urban Institute study ranking major cities on three measures of inclusion, and the findings on Dallas were devastating. The study compared 274 cities on “economic inclusion” (measured by “income segregation, housing affordability, the share of working poor residents, and the high school dropout rate”); “racial inclusion” (measured by “racial segregation; racial gaps in homeownership, poverty, and educational attainment; and the share of the city’s population who are people of color”); and “overall inclusion (which is a combination of the economic and racial inclusion scores). Dallas, the Urban Institute found, was near the bottom of the barrel for all categories. The city “ranked 272nd out of 274 cities on overall inclusion, 270th on economic inclusion, and 246th on racial inclusion.”99

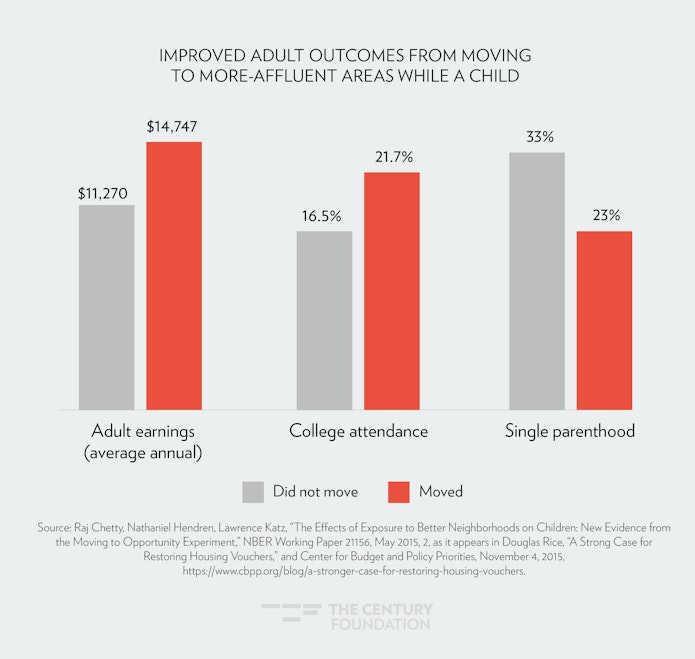

Economic and racial segregation, in turn, is connected to lower levels of social mobility; conversely, integration promotes better outcomes. In one well-known study, for example, Harvard University’s Raj Chetty and colleagues, found that when low-income children move before age 13 to more-affluent neighborhoods, their chances of going to college increase by 16 percent and their income as adults rises by 31 percent. (See Figure 1). Over a lifetime, that translates into $300,000 in additional income.100 In a separate study, Raj Chetty and colleagues found that Dallas, with its high levels of segregation, fell into the bottom half of fifty major metropolitan areas for social mobility.101

FIGURE 1

Finally, exclusionary zoning can also accelerate harmful displacement that comes with gentrification. As explained below, exclusionary zoning artificially boosts housing prices in wealthy neighborhoods, which in turn pushes middle-class households to look elsewhere, often in gentrifying communities. When it is poorly managed, gentrification can lead to widespread displacement of current residents, and can flip a community from high-poverty to high-wealth, replacing one kind of segregation with another. West Dallas is seeing this type of threat.102

Housing Affordability

Exclusionary zoning also makes housing less affordable for everyone. Economists from across the political spectrum agree that zoning laws that ban anything but single-family homes artificially drive up prices by limiting the supply of housing that can be built in a region.103 “Imagine,” Daniel Hertz notes in the Washington Post, “if there were a law that only 1,000 cars could be sold per year in all of New York. Those 1,000 cars would go to whoever could pay the most money for them, and chances are you and everyone you know would be out of luck.”104

Artificially making housing more expensive makes no sense, especially in a community like Dallas. Going back to passage of the United States National Housing Act of 1937, public policy has suggested that families should spend no more than 30 percent of their pre-tax income on housing. Yet in 2018, Dallas officials found that six out of every ten Dallas residents spent more than one-third of their income on housing.105 The result is that many families have to make a terrible choice between whether to pay the rent, or pay for food or medicine for their children.

Environmental Degradation

Exclusionary zoning in Dallas is hurting the environment. There is widespread agreement that laws banning the construction of multifamily housing promote damage to the planet.106 Single-family-exclusive zoning pushes new development further and further out, which lengthens commutes and increases the emissions of greenhouse gasses. Indeed, the United Nations Environmental Program has recommended removing limits to multifamily housing as an important strategy for reducing emissions.107

The problem of environmental degradation due to exclusive zoning especially pressing in the Dallas region, where population has been exploding. Between 2010 and 2020, Dallas was one of only three cities in the country to add at least 1.2 million residents. With a metropolitan population of 7.6 million, Dallas–Fort Worth is the nation’s fourth largest metropolitan area.108 Theodore Kim, Jessica Meyers, and Michael E. Young report in The Dallas Morning News that “planners foresee a say when development reaches out 100 miles from Dallas.” Already, “commute times are rising,” they note, and “air quality has declined.”109

Dallas’s Efforts to Combat Exclusion

Given the demonstrated harm from exclusionary policies, Dallas has taken some modest steps in recent years to desegregate schools and housing. It has adopted a small number of “transformation schools” to begin integrating Dallas public schools by income and race; it has adopted a modest housing plan, at the urging of the nonprofit Opportunity Dallas and others, to make the community more inclusive; and, most importantly, the Inclusive Communities Project is helping hundreds of families—like Patricia McGee’s—move to higher-opportunity neighborhoods.

Diverse-by-Design Transformation Schools

Although the Dallas Independent School District (DISD) has a student population that is overwhelmingly made up of low-income students and students of color, the district in recent years has been trying to take steps to voluntarily integrate a small number of schools in a way that will avoid the backlash that followed compulsory busing in the district in the 1970s. In 2014, the district hired Mike Koprowski, a young former Air Force Intelligence officer with a Harvard degree, to run the Office of Transformation and Innovation.110 Koprowski set out to create a series of new, innovative schools. Knowledgeable about the research on the substantial benefits of economic and racial diversity for all students, Koprowski believed these new schools should be diverse by design.

Koprowski brought on a dynamic young educator, Mohammed Choudhury, and together they proposed a series of “transformation schools” that would have attractive themes—such as a focus in science or the arts—that would appeal to a broad cross section of families from different economic and racial groups. In order to create a successful model, Koprowski and others surveyed community members to find out what types of schools would be popular.111 In a school district in which 90 percent of students are low income, transformation schools would aim to have a healthy socioeconomic mix of students—50 percent from middle-class families and 50 percent from low-income families—and could draw students from the suburbs or private schools as well as DISD.112 The two educators had a powerful ally in school board member Miguel Solis, who was a classmate of Koprowski from Harvard, and was elected to the school board in 2013, at the age of 27.113

The flagship initiative was Solar Prep, a school proposed by a group of female educators as a single-sex school with a STEAM (Science, Technology, Engineering, Arts and Math) theme. The idea proved popular with middle-class as well as low-income students, as did a number of the other early schools.114 In the first cohort of students, Koprowski says, “the largest number came from a school called Lakewood Elementary, which is one of the whitest and richest neighborhood schools in the entire district.”115 (Today Lakewood Elementary is 80 percent white and has just 7 percent of students who are low income.)116 Koprowski says, “we told them that the school was going to be 50 percent poor. We weren’t shy about it.” They came in droves, he says, which “speaks volumes about the appetite that’s there.”117 Another one of the schools, City Lab, was located downtown where a lot of middle-class parents work, and also proved popular among suburban families.118 The early experiments “turned out to be rock star schools,” Koprowski says, so the school board supported expansion.119 When a new superintendent, Michael Hinojosa, came on board, he embraced the idea enthusiastically.120 Today, Dallas has a total of sixteen transformation schools.121

While contributing in important ways to integration, the transformation school effort still remains relatively modest. Only an estimated 4 percent of Dallas public schools are diverse.

While contributing in important ways to integration, the transformation school effort still remains relatively modest. Only an estimated 4 percent of Dallas public schools are diverse.122 And there is no comparable effort, Choudhury says, to create a program for Dallas students to attend more affluent suburban schools along the lines of Boston’s METCO program.123 The success of diverse-by-design schools in Dallas has a great deal of room for growth.

Opportunity Dallas and the Children First North Texas Program

In 2017, Koprowski left DISD to tackle what he saw as the root cause of school segregation—the profound segregation of housing in Dallas. Koprowski founded a new non-profit, Opportunity Dallas, and recruited his past ally, Miguel Solis, to chair a thirty-two-member task force of real estate developers, affordable housing advocates, researchers, and voucher holders to make recommendations on how to reduce segregation. The group made policy recommendations to promote housing mobility and mixed-income neighborhoods, increase affordable housing, and create an early-warning detection (the “Neighborhood Change Index”) to make sure gentrification does not lead to widespread displacement and re-segregation.124 The recommendations, taken together, were meant to create what Solis calls “the first comprehensive housing policy in the history of the city.”125

In May 2018, the Dallas City Council passed, unanimously, a new housing policy that aims to create affordable housing throughout the city (not just concentrated in poor areas) and provides incentives for landlords to lease to Section 8 voucher holders. Solis lauded the plan for aggressively tackling segregation.126

Both Opportunity Dallas and the Dallas City Council focused on the city proper, and did not address the larger problem of segregation between city and suburb.127 To address that issue, other, parallel efforts have been afoot.

In 2020, the Dallas Housing Authority (DHA)’s president and CEO Troy Broussard and Dr. Myriam Igoufe, DHA’s vice president of policy development and research, worked with others to launch the Children First North Texas (CFNTX) program to relocate one thousand families with children living in high-poverty segregated neighborhoods to higher-opportunity environments in the seven-county area.128

The Children First program is part of the Walker v. HUD settlement, but it was modified and shaped based on DHA’s Assessment of Fair Housing, which is required under the Fair Housing Act’s Affirmatively Furthering Fair Housing rule.129 Igoufe was particularly alarmed that since 1990, the number of racially or ethnically concentrated areas of poverty (R/ECAPs) doubled from eighteen to thirty-six, and that many Section 8 Housing Choice Voucher holders were residing in these areas.130 Under Children First, families with children living in the most disadvantaged R/ECAPs are prioritized for moves.131

The Assessment of Fair Housing also found that Black/white segregation increased between 1990 and 2013. The dissimilarity index (in which 0 is perfect integration and 100 is complete apartheid) increased from 68 to 70.132 (By contrast, the Black/white dissimilarity index has been declining nationally.)133 Research has found that extremely low-income Black children living in racially segregated high-poverty areas often have a less than 1 percent chance of achieving upward mobility.134 The assessment further found reason to believe that zoning laws were “contributing to segregation.”135 As Igoufe notes, “land use policy dictates what gets built and where,” and in the Dallas area it has been used by privileged communities to exclude those less well off.136

As part of Children First, Igoufe surveyed families living in high-poverty neighborhoods to see if they wanted to move out. Of two hundred families, she found only three did not. “Overwhelmingly, they all want to move,” Igoufe says.137 In meetings, when families heard about the possibility of moving to higher-opportunity communities, she says, “a lot of folks actually cried because they were like, ‘this is something I never thought would come to me.’” One grandmother, Igoufe recalls, was tearful about the prospect of getting her grandson away from local gangs.138 Overall, of those polled, the number one desire was for safe neighborhoods, then good schools, and third was access to grocery stores, a major concern given the large number of food deserts in the Dallas area, Igoufe says.139

So far, the Children First program has moved only a “handful” of families, Igoufe says, because it had to be suspended with the advent of the COVID-19 pandemic. Igoufe says she is poised to move forward once the suspension is lifted.140

In nearby Fort Worth, housing integration is also on the radar. Fort Worth Housing Solutions has teamed up with the Fort Worth Independent School District and a national organization, Urban Strategies, Inc., to develop an integrated residential community. Seeded by a $35 million HUD Choice Neighborhood grant, the groups are planning a new-mixed income development called Stop Six.141 Of course creating a mixed-income neighborhood alone is only a first step toward improving outcomes for families. As Tyronda Minter of Urban Strategies notes: “What is important is that the neighborhood and school have norms that produce strong social connections, openness to truly learning, and belongingness for all.”142

Inclusive Communities Project (ICP) Mobility Assistance Program

By far the largest and longest-standing housing mobility program in the Dallas region is the Inclusive Communities Project’s Mobility Assistance Program, which has helped more than 4,500 families like Patricia McGee’s move from impoverished to high-opportunity neighborhoods since 2005.143

ICP was founded in 2004 by civil rights lawyer Elizabeth (“Betsy”) Julian. The organization is a successor to the Walker Project, which was created as part the remedy in the Walker v. HUD case.144 In 2016, fair housing attorney Demetria McCain took over the presidency of ICP for a five year period. (In September 2021, McCain joined the Biden administration as principal deputy assistant secretary for fair housing and equal opportunity at HUD.)145 ICP’s Mobility Assistance Program provides housing search assistance and counseling annually to 350 families who want to move to higher-opportunity neighborhoods. These neighborhoods include those that are in the attendance area of “an elementary school that is ranked as high performing.”146

Betsy Julian argues that we should see “housing mobility as a civil right.” There is powerful research to suggest that low-income Black families who move to higher-opportunity neighborhoods enjoy many benefits, she says; but even if the evidence were less clear, Julian notes, as a fundamental matter of principle, Black people should not be denied the choice. She writes: “the right to make that choice, and, conversely, the denial of the right to make that choice based upon race, involves fundamental civil rights that need no more basis than the Constitution.”147

Likewise, McCain said she sees the work of ICP as the latest stage in the fight for civil rights to break free of limits imposed by wealthy white interests. In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, she says, in the face of enslavement by advantaged white landowners, Black people courageously risked their lives to escape slavery. In the twentieth century, millions of resilient Black people living in the South uprooted their lives to free themselves from the tyranny of Jim Crow laws as part of the Great Migration. And today, as wealthy white people try to continue to exclude Black people from their neighborhoods, many Black people who are stuck in dangerous neighborhoods with struggling schools are taking the risk to move to wealthier areas—which may not always be welcoming to them—because they offer a better chance for their children.148

Ann Lott, the current executive director of ICP, puts the organization’s key mission this way: “ICP increases opportunities for low-income BIPOC by expanding their family’s access to housing in high-opportunity neighborhoods. Quality affordable housing is foundational, but the location of the housing is the cornerstone that promotes positive outcomes for low-income families by offering a clear path to opportunity through quality education, gainful employment, and healthy living environments.”149

Patricia McGee’s Experience with ICP’s Housing Mobility Program

Patricia McGee is a member of that third wave of resilient Black people seeking better opportunity. When McGee was raising her kids in the crime-ridden Mandalay Palms Apartments, her children were experiencing a version of the difficult childhood McGee herself had endured. McGee’s mother struggled with drug addiction and alcoholism, so at a young age, McGee shuffled back and forth between an aunt in Dallas (who favored her own kids over McGee) and a foster home in Longview, Texas, an oil town located two hours east of Dallas, near the Louisiana border.150

McGee dropped out of high school and over an extended period of time gave birth to her four children, two daughters (now in twelfth grade and tenth grade) and two sons (now in seventh grade and third grade.)151 (McGee asked that the names of her children not be used in this report.)

McGee has long wanted to get her GED, but she says it’s been a struggle. “My main priority was to make sure that I had a roof over my head and my kids’ heads.” In 2016, she took classes to get her GED, but then she suffered a series of setbacks, and for a time, she and her family became homeless.152 She and her kids were staying in a shelter, and at times, had to sleep in a car “because we had nowhere else to go.”153 Her credit score hit 600, which is in the bottom third of Americans.154

With support from a program called Under One Roof, McGee was able to move to the Mandalay Palms Apartments, which provides affordable units in the Oak Cliff section of Dallas.155 But McGee says people were “disrespectful.” She continues: “I actually stayed in Mandalay Palms Apartments for a year, dealt with all that drama, trafficking, prostitution, drugs, gunshots, all that.”156 In addition, the apartment itself was unhealthy, she says. Her unit had a water leak, which created mildew, McGee says, but “they wouldn’t do nothing about it.”157

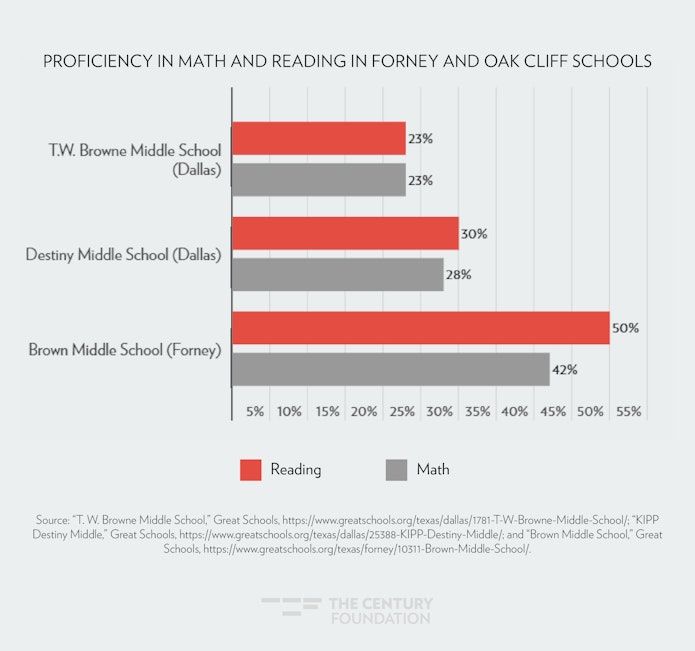

The local public schools were not as supportive of learning as they could be. “The school to me was a hot mess,” McGee says. T. W. Browne Middle School was particularly problematic. The school, where 97 percent of students are low-income, and 96 percent are Black or Hispanic, has low levels of achievement. Just 23 percent of students are proficient in math, 23 percent in reading, and 19 percent in science.158

There were also issues of safety. One of McGee’s daughters, she says, “was jumped by two girls walking home from school and just because she didn’t want to be their friend.”159 McGee complained to the school in order to resolve the issue but “they didn’t do nothing about it.”160

The elementary school, Ronald E. McNair, was also problematic, McGee says.161 In a school that is 94 percent Black or Hispanic and 98 percent low income, just 50 percent of students are proficient in math, 32 percent in reading, and 21 percent in science.162 The teachers were disrespectful, McGee says. One of McGee’s sons was grabbed by the collar by one of the teachers, she says.163 McGee complained to the principal in what she described as a forceful fashion. “I actually went off, I had to be ‘ghetto’ myself that particular day.” But the staff never updated her on what, if anything, was done.164

McGee also says she didn’t like the way her older son was held to low expectations and passed along, even though he struggled with his reading.165 It wasn’t until later, when he went to a more challenging school, that the problem was discovered. “That’s something that should have been taken care of” earlier, she says.166 In Oak Cliff, McGee says, “you got some teachers that feel like, ‘hey, I’m just here for a paycheck.’”167

The situation became so difficult that McGee moved three of her children to KIPP Destiny Middle School.168 “They was okay there,” McGee says. But student proficiency remained low. In a school that is 92 percent low income and where 96 percent of students are Black or Hispanic, only 30 percent of students are proficient in reading, 28 percent in math, and 32 percent in writing.169

Then McGee received a federal Section 8 Housing Choice Voucher and said “thank God.”170 She didn’t want to move too far outside Dallas because, she said, “I would have lost all my support system.”171 But the Inclusive Communities Project, which she first connected to in her search for rental deposit support, was also able to help her move to a better neighborhood.172

Through the ICP program, McGee and her family were briefly able to relocate to Rockwall, Texas,173 a relatively affluent community of more than 45,000 people. With a median household income of almost $92,000, Rockwall’s population is about 71 percent white, 18 percent Hispanic, 6 percent Black, and 3 percent Asian.174 “I thank God for [ICP] because if it wasn’t for them, I wouldn’t have been able to move to Rockwall,” McGee said.175 In Rockwall, some of the residents showed kindness toward McGee and her family. They made sure the family received a Christmas tree, for example, and that the kids got free eyeglass exams and shoes.176 But other families were less welcoming. McGee’s kids faced discrimination, and were called the n-word by some children.177 In the end, McGee couldn’t stay because the owner of the home McGee was renting sold the property, so she had to relocate.178

Fortunately, with ICP’s support, McGee was able to move again to Forney, Texas in May 2019.179 Forney, a city of 24,000, is just as affluent as Rockwall, but more racially diverse. With a median household income of about $93,000, Forney is 64 percent white, 19 percent Hispanic, 14 percent Black, and 2 percent Asian. In Forney, “it’s mostly a mixture of colors,” McGee said.180

Families in Forney helped out to make sure the kids were okay. “It’s been a great move for me and my kids because when we was in Dallas, you really didn’t get the support,” McGee said in a 2020 interview. “Since we’ve been out here, I have had people call and ask if it’s okay to donate this to you and your children.”181

McGee said the schools in Forney are much stronger than they were in Dallas. In 2020, the children attended four different schools.182 Her first-grade son was at Lewis Elementary, her fifth-grade son was at Smith Elementary, her eighth-grade daughter was at Brown Middle, and her tenth-grade daughter was at Forney North.183

Student achievement levels are much higher in Forney than in Oak Cliff schools, or the charter school McGee’s children attended in Dallas. At Brown Middle School, for example, 50 percent are proficient in reading and 42 percent in math.184 (See Figure 2.)

FIGURE 2

One big difference is the teacher’s level of engagement, McGee says. In Forney, she says, if teachers “see your kid struggling, they gonna call you…. They’re gonna stay on top of your kids and make sure you’re able to stay on top of them.” She continued, “they’re more on it than [the teachers in] Oak Cliff.”185

At Smith Elementary, for example, where McGee’s son was in fifth grade, he was having some problems, but she went in and met with the teachers. “We came up with a solution and since then I haven’t had no problems.”186 Likewise, after McGee became homeless a number of years ago, her oldest daughter lost a lot of credits; but in Forney, the school system put her in a credit recovery program that enabled her to be placed back in her original grade.187

Another difference was the level of parental involvement. “A lot of these people are involved, you’d be surprised,” McGee says.188 The parents chaperoned field trips, volunteered in class, and helped out in the lunchroom.189

McGee says she is very grateful to ICP for supporting her move. “If it wasn’t for them, I wouldn’t be where I am today. I would probably be still somewhere in Oak Cliff or Pleasant Grove areas that I really wouldn’t want to stay in because of the high violence.”190 She says, “I’m very thankful I was able to take my kids out.”191 McGee says she knows lots of people who were unable to access assistance like she did. “Everybody don’t want to stay in the hood,” she says. “Everyone wants an opportunity to have a nice home, a nice area where people come to visit and don’t have to worry about ducking and rolling…. It’s so peaceful out here. It’s quiet…. You don’t hear no gunshots. You don’t hear no loud music rolling through your neighborhood. You don’t hear fighting.”192

For a time, McGee took a job as an Amazon warehouse worker, where she earned $15 an hour.193 She often worked the graveyard shift, 7:00 p.m. to 5:00 a.m., but didn’t complain about the hours. “Well, I thank God that I got me a job,” she said.194

Her work, she says, has given her a sense of dignity. “In order to get what you want, you got to work,” she says.195 “All these programs that they put out here are supposed to be a stepping stone. You not supposed to stay on it forever.”196 She says she chastises her cousin who she says is “dependent on the system way too much.” In return, her cousin calls McGee “Ms. Bougie.”197 But McGee says she wants to set an example of self-reliance for her children. “Go to work. Show your kids,” she says.198 She tells her children, “Don’t get on these programs unless you really, really, really, really need it.”199

McGee has high expectations for her kids and tries to teach them that “regardless where you came from, if you do what you’re supposed to do, you can go wherever you want to go.”200 She says she tells her kids, “it’s up to you to get that education. It’s up to you to ask your teacher for the information. If you don’t understand or you want to get ahead in class, you ask for extra work.”201 She continues: “I stay on my kids,” she says. “I tell them every single morning before they go out the door to schools, ‘pay attention, make sure you’re focused, make sure you keep them grades up because you’re going to need it. Yeah, you going to be a boss, you’re going to run your own business…. You going to have people looking up to you.’ That’s what I’m trying to put in my kid’s head. You’re going to have people working for you.”202

McGee encourages her kids to watch inspiring movies, and in a comment that is painful to hear, she tells them, “You ain’t got to be nothing like me, and I hope you don’t want to be nothing like me. I want y’all to be better than me, and y’all daddies.”203 She tells her kids, “It’s easy to get sidetracked and then you’ll be sitting at home drawing food stamps cause you can’t work ‘cause you’re pregnant.”204 For herself, she said in January 2020, “my main thing now is to fix my credit, to get off the system and buy my own house.”205

After COVID-19 swept the country in the spring of 2020, McGee left her Amazon job and went to work for Maximus, a contractor that provides support for IRS call centers.206 In the fall of 2020, McGee’s life was upended again, when the home she was renting in Forney was sold.207 With support from ICP for her rental deposit, she relocated to Rockwall County, east of Texas.208 She says Rockwall is “pretty nice. It’s quiet.”209 There is “less of all the drama,” than she had in Oak Cliff.210

McGee’s children attend the local public schools, including Rowlett Elementary and Rockwall High School.211 Both are high-achieving schools. But at the high school, which is 67 percent white, 17 percent Hispanic, 7 percent Black, and 3 percent Asian,212 her daughters are sometimes the only Black students in their class, she says, and “someone may say something that they shouldn’t,” McGee says. “But I tell them to look over it and keep doing what they supposed to do.”213 McGee says her youngest is doing well and likes Rockwall schools better than the schools in Forney.214

Looking to the Future

Patricia McGee’s story illustrates what research tells us is true more generally: where you live can make a big difference in the life chances of families, particularly children. But the vast majority of families who participate in the Housing Choice Vouchers program in Dallas remain in high-poverty neighborhoods. While ICP helps 350 families per year move to higher opportunity neighborhoods, that number represents just 1 percent of the 26,257 families in Dallas who use Housing Choice Vouchers.215

Much more needs to be done to tear down the government-sponsored walls of exclusion that keep families with modest incomes from enjoying greater opportunity. One very important step is the Build Back Better framework, which invests $25 billion in new rental assistance programs, mostly for the Housing Choice Voucher program that McGee participates in.216 The Center for Budget and Policy Priorities estimates the boost in funding would reach an additional 300,000 households (and 700,000 people) nationwide, an important step given that only one in four households that qualify for a Housing Choice Voucher currently receives one.217

Importantly, the framework doesn’t stop there; it goes directly after exclusionary zoning by creating a new program called the Unlocking Possibilities program. Under the plan, the federal government would provide $1.75 billion for a competitive grants program for infrastructure in communities that agree to reduce exclusionary zoning practices.218 The proposed program, notes Brian Deese, director of the National Economic Council, is “first ever federal competitive grants program” aimed at reducing exclusionary zoning.219

The program is a big step forward and deserves support, but critics note it lacks some of the stronger provisions in early anti-exclusionary proposals advanced by Amy Klobuchar, Elizabeth Warren, and Cory Booker.220 Moreover, as Peggy Bailey, senior advisor to HUD Secretary Marcia Fudge, has noted, Unlocking Possibilities is aimed at neither the most progressive communities (which have already adopted inclusive policies) nor the most exclusive communities (which are unlikely to be moved by a voluntary program) and instead aims at “folks in the middle.”221

To address the most exclusionary communities, sticks are required to compliment carrots like the Unlocking Possibilities program. To move the needle on communities like Sunnyvale and Highland Park, I have argued that Congress should pass a new Economic Fair Housing Act, which would create a private right of action—comparable to the one found in the 1968 Fair Housing Act—to allow victims of economically discriminatory government zoning policies to sue in federal court, just as victims of racial discrimination currently can do.222

The 1968 Fair Housing Act was a monumental advance for human freedom, and the “disparate impact” tool associated with it can be an important lever to address exclusionary zoning that disproportionately hurts people of color, as was demonstrated in the Sunnyvale case. More funding should be provided to support such litigation through the Fair Housing Initiatives Program.223

But government-sponsored economic discrimination is wrong, whether or not it has a disparate impact on racial minorities. And a new Economic Fair Housing Act would remove some unnecessary requirements that currently reduce the chances that low-income plaintiffs of color will prevail. Under disparate impact cases, expert statistical studies are required to show the disproportionate impact on minority groups, which adds to the cost of litigation.224 Tom Loftus, president of the Equitable Housing Institute, notes, “Courts routinely have dismissed ‘disparate impact’ lawsuits where the plaintiffs failed to prove that minority group members were affected disproportionately by economic discrimination.”225 One of the most extensive studies of disparate impact litigation, conducted by Stacy Seicshnaydre of Tulane University, found that in the 2000s, plaintiffs prevailed on appeal in disparate impact cases just 8.3 percent of the time.226 By removing a hurdle in disparate impact litigation, the Economic Fair Housing Act could help address racial segregation in housing, which has been identified as the central piece of unfinished business of the civil rights movement.227

As we struggle to come out of a pandemic in which low-paid workers such as grocery clerks, health aides, and delivery workers have been recognized as everyday heroes, government discrimination against them must end. The principle of giving all people access to housing in neighborhoods of opportunity should apply in every town and state in the country—not just those that want to participate in the new Unlocking Possibilities program.

Patricia McGee and her children have lived on both sides—outside of the exclusionary walls, where she feared for her children’s safety and was deeply concerned about the education they were receiving; and on the other side, where her kids have been able to play freely and receive the education they deserve. Local governments should not be allowed to erect artificial barriers preventing families from enjoying the American Dream, in the Dallas metropolitan area, or anywhere else in the country.

Notes

- Patricia McGee, Interview with Kay Butler, Inclusive Communities Project, December 26, 2018, “Voices of Vision: Voucher Holders Seeking Opportunity Moves Speak,” StoryCorps Archive, https://archive.storycorps.org/interviews/voices-of-vision-voucher-holders-seeking-opportunity-moves-speak-8/.

- Patricia McGee, Interview with Michelle Burris and Richard Kahlenberg, January 22, 2020, 22. I want to thank Ms. McGee for sharing her story with The Century Foundation. I also want to thank my colleague, Michelle Burris, who was instrumental in setting up the interviews for this report and participating in each and every one of them. This report is part of a larger project on The Voices of the Excluded, of which Michelle has been an invaluable part.

- McGee Interview, 6–7.

- Patricia McGee, Interview with Michelle Burris and Richard Kahlenberg, July 9, 2020 (Interview II), 8; and Inclusive Communities Project, https://inclusivecommunities.net/.

- McGee Interview, 6.

- Philip Tegeler and Micah Herskind, “Coordination of Community Systems and Institutions to Promote Housing and School Integration,” Poverty Race & Research Action Council, November 2018, 19–20, https://prrac.org/pdf/housing_education_report_november2018.pdf; and John Egan, “This is just how much Dallas-Fort Worth’s population exploded in the last decade,” Dallas Culture Map, August 13, 2021, https://dallas.culturemap.com/news/city-life/08-13-21-dallas-census-population-ranking-of-largest-metro-areas/ (7.6 million residents).

- Richard Rothstein, The Color of Law: A Forgotten History of How Our Government Segregated America (New York: Liveright, 2017), 47.

- Elizabeth Brown and George Barganier, Race and Crime: Geographies of Injustice (Oakland: University of California Press, 2018), 168.

- Racial zoning was struck down by the U.S. Supreme Court in Buchanan v. Warley, 245 US 60 (1917). Public enforcement of private racially restrictive covenants was struck down in the case of Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U.S. 1 (1948).

- Jim Schutze, “The Accommodation Tanked 30 Years Ago. It’s Time to Try Again.” D Magazine, September 2021, https://www.dmagazine.com/publications/d-magazine/2021/september/the-accommodation-tanked-30-years-ago-its-time-to-try-again/.

- Jim Schutze, “The Accommodation Tanked 30 Years Ago. It’s Time to Try Again.” D Magazine, September 2021, https://www.dmagazine.com/publications/d-magazine/2021/september/the-accommodation-tanked-30-years-ago-its-time-to-try-again/. See also, Jim Schutze, The Accommodation: The Politics of Race in an American City (Secaucus, N.J.: Citadel Press, 1987), 5.

- “Background Information: DISD Desegregation Litigation,” Southern Methodist University, https://www.smu.edu/Law/Library/Collections/DISD-Desegregation-Litigation-Archives/Background-Info.

- Schutze, The Accommodation, 86.

- Tasby v. Estes, 342 F.Supp. 945, 947–50 (1971).

- See Gerald S. McCorkle, “Busing Comes to Dallas,” Southwestern Historical Quarterly 111, no. 3 (January 2008): 304–33, at 313, https://muse.jhu.edu/article/408312/pdf.

- McCorkle, “Busing Comes to Dallas,” 321.

- McCorkle, “Busing Comes to Dallas,” 305.

- Marvin E. Edwards, “Equity and Choice: Issues and Answers in the Dallas Schools, Address Before the National Committee for School Desegregation 17,” (March 1990), cited in John A. Powell, “Living and Learning: Linking Housing and Education,” Minnesota Law Review 80 (1996) at 789 n. 132, https://scholarship.law.umn.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=2666&context=mlr.

- See Richard D. Kahlenberg, All Together Now: Creating Middle-Class Schools through Public School Choice (Washington, D.C: Brookings Institution Press, 2001), 92.

- “Dallas Independent School District,” Great Schools, https://www.greatschools.org/texas/dallas/dallas-independent-school-district/.

- Dana Goldstein, “Dallas Schools, Long Segregated, Charge Forward on Diversity,” New York Times, June 19, 2017, https://www.nytimes.com/2017/06/19/us/dallas-schools-desegregation.html.

- “History & Traditions,” Highland Park Independent School District, https://www.hpisd.org/apps/pages/index.jsp?uREC_ID=924382&type=d&pREC_ID=1260104.

- Originally, the district was on the outside Dallas’s city limits, but over time, Dallas came to surround it. See Tasby v. Estes, 572 F.2d 1010, 1015 (5th Cir., 1978).

- Mike Koprowski, Interview with Michelle Burris and Richard Kahlenberg, June 9, 2020.

- “Early Development.” Town of Highland Park, Texas, https://www.hptx.org/624/Early-Development.

- 572 F.2d at 1015.

- Laura Moser, “This Voter Measure Wasn’t Just About School Funding. It Was About Segregation and Racism in a White, Wealthy Dallas Enclave,” Slate, November 4, 2015, https://slate.com/human-interest/2015/11/dallas-highland-park-votes-for-361-million-school-bond-here-s-how-ugly-racist-and-crazy-the-vote-was.html.

- “Highland Park Independent School District,” Great Schools, https://www.greatschools.org/texas/dallas/highland-park-independent-school-district/.

- “Dallas Independent School District,” Great Schools, https://www.greatschools.org/texas/dallas/dallas-independent-school-district/.

- Koprowski Interview, 18.

- Dallas Housing Authority Annual Report, 2018, 16, https://dhantx.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/DHA-Annual-Report_Final_For-Web.pdf.

- 734 F. Supp. 1231, 1233 (N.D. Tex. 1989).

- 734 F. Supp. at 1233.

- Philip Tegeler and Micah Herskind, “Coordination of Community Systems and Institutions to Promote Housing and School Integration,” Poverty Race & Research Action Council, November 2018, 19, https://prrac.org/pdf/housing_education_report_november2018.pdf.

- See “Fifty Years of ‘The People v. HUD,’” (timeline), Poverty Race & Research Action Council, https://www.prrac.org/pdf/HUD50th-CivilRightsTimeline.pdf (detailing the litigation and the subsequent Circuit Court opinions). See also “Walker v. U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development,” Civil Rights Litigation Clearinghouse (detailing litigation through 2013), https://www.clearinghouse.net/detail.php?id=1015.

- See Schutze, The Accommodation, 5–6, 72–74, 77–78, 158, 185, and 189.. See also Koprowski Interview, 3–4 (that Schutze found that “deals were cut” between “white power brokers in the North and the black power brokers in the South”).

- Koprowski Interview, 8–9. See also Teresa Wiltz, “This City Wants to Reverse Segregation by Reviving Cities,” Pew Charitable Trusts, October 3, 2018, https://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/blogs/stateline/2018/10/03/this-city-wants-to-reverse-segregation-by-reviving-neighborhoods.

- Texas Dept. of Housing & Community Affairs v. Inclusive Communities Project, 135 S.Ct. 2507 (2015).

- Texas Dept. of Housing & Community Affairs v. Inclusive Communities Project, 135 S.Ct. 2507, 2514 (2015).

- 135 S.Ct., at 2526.

- U.S. District Court, N.D. Tex, “Memorandum Opinion,” 2016, at 15–16, 32, https://www.clearinghouse.net/chDocs/public/PH-TX-0004-0020.pdf; “Inclusive Communities Project v. Texas Department of Housing and Community Affairs,” Civil Rights Litigation Clearinghouse, https://www.clearinghouse.net/detail.php?id=13857. ICP does point to an uptick in Texas’s employment of LIHTC-supported housing in high opportunity neighborhoods. Between 2011 and 2016, roughly 60 percent of units have been located in lower poverty, racially diverse higher-opportunity neighborhoods. See “Ten Years and Counting. Housing Mobility, Engagement and Advocacy: A Journey Towards Fair Housing in the Dallas Area,” Inclusive Communities Project, 7, https://lawsdocbox.com/Immigration/97239544-Ten-years-and-counting-housing-mobility-engagement-and-advocacy-a-journey-towards-fair-housing-in-the-dallas-area.html.

- “Letter of Findings of Non-Compliance,” U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, November 22, 2013, 2, http://nlihc.org/sites/default/files/HUD_Dallas_Fair_Housing_11-22-13.pdf.

- “Letter of Findings of Non-Compliance,” U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, November 22, 2013, 4, 21, 27–28, http://nlihc.org/sites/default/files/HUD_Dallas_Fair_Housing_11-22-13.pdf. See also Nikole Hannah-Jones, “HUD Finally Stirs on Housing Discrimination,” Pro Publica, December 6, 2013, https://www.propublica.org/article/hud-finally-stirs-on-housing-discrimination; and Jim Schutze, “Julian Castro for President? Then He Needs to Explain His Dallas Decision,” Dallas Observer, December 17, 2018, https://www.dallasobserver.com/news/on-way-to-white-house-maybe-julian-castro-will-explain-his-dallas-desegration-decision-11417163.

- Hannah-Jones, “HUD Finally Stirs.”

- Jim Schutze, “Julian Castro for President?”

- Mohammed Choudhury Interview with Michelle Burris and Richard Kahlenberg, May 28, 2020, 6. See also Koprowski Interview, 5.

- Jim Schutze, “Julian Castro for President? “ See also Schutze Interview, 5 (“Castro just deep sixed the whole investigation; killed it”).

- Jim Schutze, “Julian Castro for President?”

- Demetria McCain Interview with Michelle Burris and Richard Kahlenberg, June 12, 2020, 2.

- McCain Interview, 3.

- McCain Interview, 10.

- Jonathan Rothwell and Douglas Massey, “Density Zoning and Class Segregation in U.S. Metropolitan Areas,” Social Science Quarterly 91, no. 5 (December 2010): 1123–43, http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3632084/.

- Richard Rothstein, The Color of Law: A Forgotten History of How Our Government Segregated America (New York: Liveright, 2017), 47.

- Rothstein, The Color of Law, 50.

- Heather Way, “Texas Must Do More to Create Inclusive Affordable Housing,” UT News, April 9, 2015, https://news.utexas.edu/2015/04/09/texas-must-do-more-to-create-inclusive-affordable-housing/.

- Koprowski Interview, 7.

- Jon Anderson, “Losing Amazon HQ2 Gave Dallas Time to Figure Out Zoning Policy,” DallasDirt, July 23, 2019 (citing UrbanFootprint), https://candysdirt.com/2019/07/23/losing-amazon-hq2-gave-dallas-time-to-figure-out-zoning-policy/.

- Solis Interview, 2.

- See Town of Highland Park, Texas, “Zoning,” https://www.hptx.org/237/Zoning, and “Zoning Map with addresses,” https://www.hptx.org/DocumentCenter/View/1448/ZONEMap-w-ADDRESSES-Model-Website-Upload-9-10-2020?bidId (showing virtually the entire town is dedicated to zones A,B,C,D, and E for single family homes only tiny slivers on the periphery—F, G and H—are open for duplexes and other multifamily units).

- See Dews v. Town of Sunnydale Tex., 109 F.Supp. 2d 526 (N.D. Tex. 2000), https://law.justia.com/cases/federal/district-courts/FSupp2/109/526/2522883/.

- 109 F. Supp 2d at 529. See also Alice M. Burr, “The Problem of Sunnyvale, Texas and Exclusionary Zoning Practices,” Journal of Affordable Housing & Community Development Law 11, no. 2 (Winter 2002): 203–25, 203; and McCain Interview, 4–5.

- “QuickFacts: Sunnyvale town, Texas,” U.S. Census Bureau, https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/sunnyvaletowntexas/PST045219; and “QuickFacts: Texas,” U.S. Census Bureau, https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/TX (median household income in 2019 was $61,874).

- 109 F. Supp. 2d at 539. See also Burr, “The Problem of Sunnyvale,” 203 and 220 n.3. After years of lawsuits, Sunnyvale’s population is still 51 percent White, 23 percent Asian, 12 percent Hispanic, and 9 percent Black. U.S. Census Bureau, QuickFacts, Sunnyvale town, Texas. https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/sunnyvaletowntexas/PST045219

- 109 F. Supp. 2d at 529 and 540. See also Burr, “The Problem of Sunnyvale,” 203.

- 109 F. Supp. 2d, at 541–42.

- 109 F. Supp. 2d, at 547.

- 109 F. Supp. 2d at 534, 537.

- 109 F. Supp. 2d at 530. See also Burr, “The Problem of Sunnyvale,” 203.

- Burr, “The Problem of Sunnyvale,” 205. See also 109 F.Supp. 2d at 563 (“The Act has been interpreted to prohibit municipalities from using their zoning powers in a discriminatory manner, that is in a manner which excludes housing for a group of people on the basis of one of the enumerated classifications”).

- 109 F. Supp.2d at 566.

- 109 F. Supp.2d at 568.

- 109 F. Supp. 2d at 569.

- 109 F. Supp. 2d at 573.

- See “Other Housing Cases,” Daniel & Beshara, P.C. https://www.danielbesharalawfirm.com/other-cases; Daniel & Beshara is a Dallas-based civil rights law firm that works with ICP.

- McCain Interview, 4.

- McCain Interview, 5.

- McCain Interview, 7.