Shia Islamist parties have dominated Iraq’s post-2003 electoral politics and have taken a controlling share of the country’s political system. Among these factions, the Sadrist Movement—led by the cleric Muqtada al-Sadr—appears particularly adept at mobilizing an electoral base and sustaining it over multiple election cycles. Most recently, the Sadrists emerged as the largest single party from Iraq’s October 2021 elections. The Sadrists in Basra collected more seats in 2021 than all the movement’s Shia Islamist rivals combined.1 This contrasts with trends in the wider region, where— despite the so-called “Islamist electoral edge”—Islamists have frequently failed to sustain electoral popularity or translate initial electoral success into enduring political hegemony.2

At the same time, the power of political Islamism—typically defined as a form of political activism asserting and promoting “beliefs, prescriptions, laws, or policies that are held to be Islamic in character”—appears to be diminishing.3 For instance, in his forthcoming report in this series, Fanar Haddad argues that “Shia politics” has lost much of its analytical salience for interpreting politics in Iraq, Shia or otherwise.4 In fact, Islam, and even Islamist ideology, have been decentered in the politics of Iraq’s nominally Shia Islamist groups. These parties are increasingly autonomous from religious–clerical leadership, they are transactional in their political alliances with Islamist and non-Islamist groups alike, and their electoral platforms make scant reference to Islamist ideology. Despite their long political dominance, Iraq’s Shia Islamists have not sought to create an Islamic state or impose sharia. Where Islamism manifests politically, it tends to do so as a thin veneer, raising the question: what is Islamist about Iraq’s Shia Islamists?5

Here, too, the Sadrists often represent an exception to broader trends. The movement retains strong linkages between religious–clerical and political spheres. Indeed, the formal political apparatus of the Sadrist Movement is largely subordinate to its clerical leadership. Similarly, while other Islamists have moved away from conventional forms of Islamist political ideology in search of alternative sources of legitimation and electoral appeal, the Sadrists have doubled down on religious appeals and their own brand of Islamist ideology—Sadr’s ideology of charisma.

How is this Sadrist exception explained? That the Sadrists benefit electorally from a large social base is well known. Yet how the loyalty of this base is maintained, and how it is deployed politically, are not so well understood. In part, this reflects analysts’ focus on Sadrist militancy at the expense of the Sadrist base, the movement’s “ordinary” followers, and everyday aspects of the movement. As a result, the conventional depiction of the movement tends to highlight its fragmentary nature and lack of internal coherence and discipline.6 However, shifting attention to the Sadrists as an electoral phenomenon inverts this picture. The puzzle then becomes explaining the remarkable endurance and cohesion of the Sadrist electoral base despite multiple splinters in the movement’s religious and paramilitary strata.7

The literature explaining the Islamist electoral edge and its fragility has tended to emphasize Islamists’ reputation as “political outsiders,” and their reputation for effective governance, along with Islamists’ provision of nonstate services, the mobilizing power of religious institutions and networks, and the hegemony of Islamist ideology and identity at a societal level.8 However, these factors do not fully explain Sadrist electoral power. More important have been the Sadrists’ capture of strategic networks within both state and civil society, combined with Sadr’s particular mode of charismatic authority.9 These give the Sadrists access to a unique combination of resources. They way that these resources are deployed within a sophisticated electoral strategy ultimately explains the Sadrist exception as an electoral force, both vis-à-vis non-Islamist parties and other Shia Islamist groups.

This report addresses these arguments through a case study of the Sadrists’ electoral politics in Basra during the October 2021 elections. The aim is to explain why the Sadrist Movement has proven more capable than both non-Islamists and the group’s Shia Islamist rivals at sustaining electoral success over the long term.10 The report also identifies potential vulnerabilities in the Sadrists’ electoral machine. The report ultimately addresses whether the sources of Sadrist electoral power relate to religious and Islamist features of the movement—and therefore whether or not “Islamism,” or “Shia Islamism” remain useful or necessary analytical concepts for understanding Shia politics in Iraq.

This report draws on the author’s analysis of textual and audiovisual materials, such as Sadrist election propaganda, and voting data from the Iraqi Higher Electoral Commission (IHEC). The research is also based on interview data collected by the author during fieldwork in Iraq in the summer of 2016 and spring of 2020. This includes dozens of interviews and more informal discussions with senior and mid-ranking Sadrists in the movement’s political, religious, and cultural-intellectual strata, as well as non-Sadrist political figures, activists, and informed observers with first-hand knowledge gained from working either alongside the Sadrists or against them. These data have been supplemented by more recent communications, conducted remotely by the author, with a smaller number of Basra-based observers and Iraqi researchers. In most cases, these sources have been anonymized—either at the request of the interviewees, or on the author’s initiative—to protect sources from potential reputational damage or the risk of physical harm. These risks relate to sensitivities around criticism of Sadr and the Sadrist Movement, as well as the illicit or sensitive nature of some of the practices being discussed in the report.

The Sadrists in Basra

The Sadrist role in Basra changed markedly after 2008, when Operation Charge of the Knights (the Iraqi army’s campaign in Basra against the Sadrist militia, the Mahdi Army, known in Arabic as Jaysh al-Mahdi) effectively brought a chaotic period of militia gangsterism to an end.11 Since 2008, a more ordered stability prevailed in the governorate, and the Sadrists adapted accordingly. Sadrist violence previously transacted more directly into financial and other forms of power (for example, via rampant kidnapping for ransom). But post-2008, this violence was redirected through a developing landscape of government contracting, trade, and private-sector commercial activity. For instance, the Sadrists (along with other militia and political groups such as Badr, Asa’ib Ahl al-Haq and the Dawa Party) now provide commercial security services in Basra in the form of private security companies.12 Sadrist violence was thus “moderated” via its sublimation into the systemic violence of the Iraqi state and its political economy.

State capture has allowed the Sadrists to act as the state—for example, issuing legal titles, documents, and licenses.

One example is the “ikhraj” (or “fixer”) companies who manipulate the customs process at Umm Qasr Port, one of the most important economic rackets in Iraq. The ikhraj companies can generate $2–5,000 profit per container, and $10–20,000 on a single transaction, amounting to total revenues per day for this racket in the tens of millions of dollars. The Sadrists operate their own fixer companies alongside other political and paramilitary groups.13 Where the Sadrists have an economic edge, however, is through their cooperation, with the Beit Shaya’a sub-tribe in al-Faw, to monopolize subcontracting for the Grand Faw Port mega project. The project, which will be completed in phases between 2023 and 2045, hopes to establish the biggest port facility in the Middle East and will cost billions of dollars. In 2019, the Sadrists pushed Asa’ib Ahl al-Haq out of the unofficial economic committee controlling the distribution of these financial flows, becoming the sole patrons of the Beit Shaya’a and turning the Grand Faw Port project into the Sadrists’ single biggest revenue stream.14

These forms of economic extraction far exceed the value of financial resources that the Sadrists derive from religious sources (primarily religious taxes and charitable donations). Precise figures are extremely difficult to obtain; however, a very rough estimate based on available evidence can be made. Adnan Shahmani, a cleric in Sadr’s Najaf office in 2009, stated that the movement collected around $65,000 a month in charitable donations—which, even though it has likely fluctuated over time, seems to clearly represent a small portion of overall revenue streams.15 Thus, in the Sadrist case, the electoral benefits derived from patronage, services provision, and electoral spending power are linked less to bottom-up resource mobilization through religious institutions and practices, and more to the Sadrists’ direct integration with the Iraqi state and civil society.

Strategic Networks

In Basra, the Sadrists have also established strategic networks at ports and border crossing points, as well as several services directorates and government bodies. These networks are most influential in the electricity directorates, the Basra Health Department, the Basra Ports Authority, and Basra Municipalities Directorate. The Basra governorate office is also within the Sadrist network, primarily through Deputy Governor Mohammed Taher al-Tamimi, who is a member of the Sadrist Movement.16

This form of state capture has extended the Sadrist electoral base in Basra to parts of the professional middle classes, albeit via a highly transactional and fluid logic of affiliation. Consequently, the conventional view of the Sadrists as a purely proletarian phenomenon needs to be updated.

In some circumstances, this state capture also allows the Sadrists to act as the state, for example, when issuing legal titles and documents, licenses, and accreditations. The Municipalities Directorate in Basra, largely under Sadrist control since 2010, is one such case. The Sadrists have used the directorate to issue legal titles, and to sell land and property deeds to the movement’s supporters at reduced rates and in ways that circumvent planning laws. As a result, certain areas of Basra (Anadalus, the banks of the Khura River, and the so-called Casino Lubnan district) are notorious for quasi-legal slum settlements and business premises that are subject to continual ownership disputes and attempted demolitions and removals.17

State capture works in tandem with the Sadrists’ networks in civil society and nonstate social spheres (such as familial and tribal networks). One example is recent protests by the Beit Shaya’a in al-Faw, demanding employment opportunities from the Korean firm Daewoo—which operates the Grand Faw Port project—for local young men. This dispute was mediated by Farhan al-Fartousi, the Sadrist director of the Iraqi Ports Authority in Basra, who brokered a “de-escalation” of the protests. The incident led to Daewoo’s rapid creation of several hundred jobs for Beit Shaya’a tribesmen—funded through the Iraqi state via financial transfers from the Ministry of Finance to the Daewoo project. To put this in perspective, at the time of the al-Faw protests, hundreds of graduate students had been protesting at Basra Oil Company offices in the city of Basra for around a year to demand employment opportunities, with much more limited results.18

The religious dimension of the Sadrist Movement in Basra is officially governed by a committee comprised of Sheikh Aayad al-Mayahi, the head of the Basra branch of the Office of the Martyr al-Sadr (OMS); the senior Sadrist clerics in the province, Sayyid Sattar al-Battat and Sayyid Haadi al-Dunaynawi, who lead Friday prayers at the most important Sadrist prayer site in Basra (the prayer yard in Khamsa Meel district); and Sheikh Hazem al-Araji, Muqtada al-Sadr’s personal representative in the province. Sheikh Hassan al-Husseini and Sheikh Mustafa al-Husseini are the Sadrists’ representative and assistant representative for religious affairs in Basra, with the former being particularly well connected in the community. This committee oversees management of the Sadrists’ religious and cultural activities, staffing of mosques and hussainiyas (congregation halls), oversight of the khutba al-juma’a (Friday sermon), collection of religious taxes, and distribution of social services. Araji acts as a floating broker, assisting in mediating all manner of religious, political, commercial, paramilitary, and tribal relationships and disputes by leveraging his status as Sadr’s personal representative.19

This religious structure is critical to the reproduction and political deployment of the Sadrist base. It is primarily at Sadrist hussainiyas and prayer yards that ordinary Sadrists gather and participate in communal worship as an intergenerational and familial community. In addition to the Friday sermon, a Sadrist imam will typically hold smaller and more intimate gatherings after prayers where worshippers can ask direct questions on matters that require religious judgment. This is not primarily a political experience, as questions will typically focus on everyday matters of family life, sexual health, and business practices. Nevertheless, the practice serves to reproduce forms of authority within the movement. Meanwhile, the Friday sermon itself can be a highly political event. The content of the sermon is overseen and controlled by the Najaf OMS. Consequently, if the Sadrist leadership wants a uniform electoral message disseminated within the movement, it can easily do so via the Friday sermon.

These elements all play a role in the formation and reproduction of the Sadrist social base in Basra. This base is not primarily generated or bound together through transactional patronage or utility-based social interactions. Rather, it is fundamentally composed of extended familial networks in which Sadrist identity (which entails varying degrees of religiosity) is intergenerationally reproduced. For instance, one of the most populous Sadrist districts in the city of Basra is known as Hayy al-Hussein (after Hussein Ibn Ali, the third Shia Imam and a symbol of sacrifice and martyrdom), although its earlier name was Hayyaniya. The name change took place around 2006 and reflected the steady transformation of the district’s demography due to inward migration from the rural parts of the governorate of Maysan. The change reflected a gradual Sadr-ization of the district, which was effected through familial and tribal networks, producing a community with a high degree of social bonding. Being Sadrist, therefore, is not a primarily “political” identity, as many analysts argue, but rather an identity with much deeper layers of socialization.20

Sadrist affiliation also intersects with tribal affiliation where the historic loyalty of tribal leaders to a particular religious reference (marja’) transmits through wider tribal networks. However, such affiliations are also fluid and subject to reconfiguration based on more near-term and transactional logics (as in the case of the Beit Shaya’a outlined above). There is rarely an exact overlap between Sadrist and tribal networks. For instance, the Beit Shaya’a in southern Basra follow Sadr, while other parts of the tribe are closer to Dawa or Badr. That said, the tribes in Basra with the most Sadrist representation are Al Furijat, Bani Sukain, Bait Rumi, Al Mariyan, parts of Al Gamarasha (containing a high representation of marsh Arabs with networks involved in arms smuggling and narcotics), and parts of the Bani Malik, Al Bazoon, and Al Shawi tribes.21

The Sadrist base is largely urban and rural poor, which continues to give the movement a pronounced socioeconomic class orientation.

The Sadrist base is largely urban and rural poor, which continues to give the movement a pronounced socioeconomic class orientation. In the city of Basra, the Sadrist base is clustered in certain poorer districts, which confers important electoral advantages. The areas of Hayy al-Hussein, Jumhuriya, Tamimiya, and Khamsa Meel have been Sadrist strongholds since before Operation Charge of the Knights. Sadrist affiliation in Hayy al-Hussein and Tamimiya is estimated to be at least 85 percent, while Jumhuriya is closer to 70 percent. Khamsa Meel is somewhat lower, as recent rural-to-urban migration has diversified the district.22 Nevertheless, the main Sadrist prayer yard in the city of Basra is located in Khamsa Meel, with the second most significant prayer yard being in Kut al-Hajaj (close to the districts of Hayy al-Hussein and Jumhuriya). All these districts, with the exception of Tamimiya, fell within the city of Basra’s District One electoral district, making this district highly competitive for the Sadrists.

Learn More About Century International

Sadrist Election Strategy and Tactics

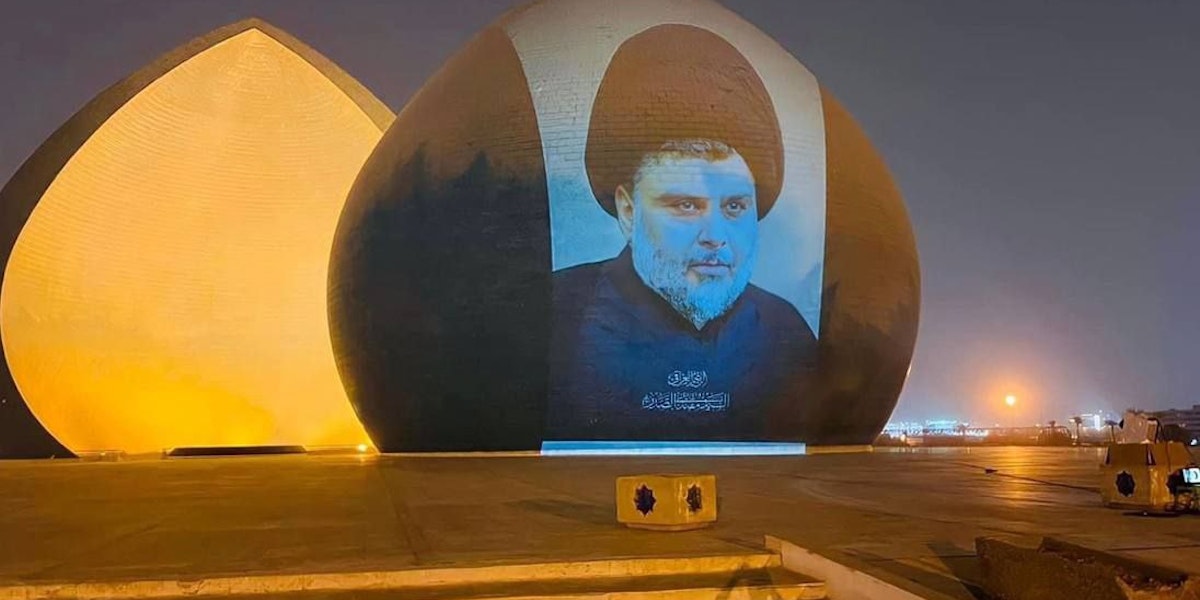

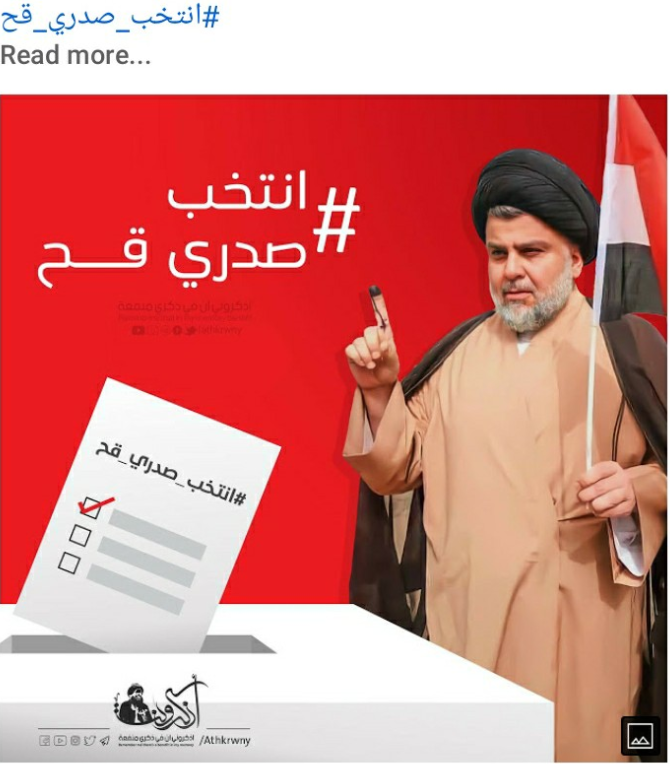

Understanding how these networks and resources are mobilized for elections requires considering the strategic dimension of Sadrist electoral politics. At the national level, Sadrist electoral strategy in 2021 took shape as a form of Sadrist exceptionalism. The movement eschewed its previous attempts to build broad-based pre-election alliances, and relied entirely on mobilizing its own core base. Election posters exhorted supporters to elect a “pure Sadrist.”

Campaign rhetoric contained the usual platitudes about corruption and reform, but these were placed within a religious frame: Sadr’s unique and sacred mission to guide Iraq back to power, prosperity, and sovereignty. This was overlain with explicitly religious appeals to “return Iraq to the correct religious path” and to restore “obedience to the hawza” (referring to the seminary that establishes Shia doctrine).23

This messaging sought to energize the Sadrist base around a religious obligation. In this sense, the Sadrists did not present the politics of reform and anti-corruption as a matter of practical policy prescriptions, but rather as a form of ethical action without a strong sense of political instrumentality. Reform was elevated into a religious endeavor. Secondarily, Sadrist electoral discourse sought to prevent bleeding at the edges of the base in the form of votes lost to the protest parties—those parties established in the wake of the Tishreen movement that began in October 2019—or to abstentions, by trying to associate the protest movement with religious deviance and moral corruption.24

The Sadrists feared the pull of the Tishreen movement on Shia youths.25 In fact, internal polling by the Sadrists ahead of the election raised concerns among the leadership, prompting Sadr to consider alternative strategies, such as an election boycott.26 Recent survey data commissioned by Chatham House has indicated the surprising depth of sympathy for the Tishreen movement among ordinary Sadrists, despite a recent history of antagonism between the two camps.27

However, the Sadrist election strategy was assisted by three contextual factors. First, a new electoral law that was finalized in 2020 shifted Iraq to a form of “first-past-the-post” voting system. The law subdivided each governorate into several electoral districts returning three to five members of parliament based on the number of votes each candidate obtained, rather than a proportional system with centrally managed party lists and transferable votes.28 The new system advantaged groups able to mobilize a core base and with the internal discipline to strategically distribute votes among their candidates. This new system played directly into Sadrist exceptionalism.

Second, the failure of the rival Fatah Alliance to adapt to the new system caused internal fragmentation and an incoherent election strategy that undermined the multiparty coalition’s votes-to-seats ratio.29

And third, the Tishreen movement’s partial boycott of the election amplified the Sadrist electoral edge in the context of low overall turnout. This was particularly true in Basra, where Tishreen groups offered no political platform to contest the elections.

The Sadrists took full advantage of this opportunity by adapting swiftly to the new electoral system. This effort was spearheaded by Walid al-Karimawi, a professional political consultant and one of the few non-hawza figures in Sadr’s “inner circle.” Karimawi has headed the Sadrists’ electoral file for multiple election cycles, is highly experienced, and Sadr trusts him. He wields considerable central control over the movement’s electoral strategy and operation.30 He also plays a key role as a broker and negotiator in the Sadrists’ postelection government formation negotiations.31

Karimawi implemented a four-tiered electoral strategy based on a careful assessment of the Sadrists’ strength in each electoral district. The strategy determined how many Sadrist candidates were deployed in each constituency, with a maximum of three (usually two men and one woman) in districts with the highest density of Sadrist voters. Crucially, the Sadrists were also able to control how their vote base was distributed among the movement’s candidates within each electoral district. This was achieved by dividing up each district into sectors, each assigned to vote for a specific candidate.32 This was visible in Basra, where electoral posters for Sadrist candidates promoted different candidates in different neighborhoods without any overlap or direct competition.33

No other political party could match this degree of control. The ultimate effect was remarkable efficiency in translating votes into seats, with each Sadrist seat in Basra costing fewer votes, on average, when compared to the seat-cost ratio for the movement’s rivals. In fact, the total number of votes cast for Sadrist candidates in Basra fell by around 20,000 between the 2018 and 2022 elections, while the total number of parliamentary seats won increased from five to nine. (There is further discussion of the Sadrist electoral performance in Basra below.)

The Sadrists also masterfully utilized Iraq’s parliamentary gender quota system, which requires that a quarter of seats go to women. Of the ninety-seven women elected to parliament in 2021, twenty-four were Sadrists. The Sadrists secured more seats via the gender quota than Fatah’s total number of seats. The Sadrists’ advantage within the quota system relates to the distinct way in which the Sadrist vote base is mobilized (explored more below). Women running for parliament in Iraq typically garner fewer votes than men, and tend to lack comparable bases of local popular support. This affects women Sadrist candidates less than those of other parties or independents, because they rely on the strategic distribution of votes by the Sadrist electoral machine, rather than their own, autonomous support base.

Moreover, the threshold of votes required to win a seat through the gender quota is significantly lower, making this a highly efficient investment of votes per number of seats gained. In fact, in districts where the Sadrists had a very low representation, they were still able to gain a seat by focusing all their votes on a single woman candidate. This worked even in a small number of “Sunni” districts in Baghdad.

The success of the Sadrist strategy depended on accurate information about the geographic distribution and demographics of the movement’s core support and discipline and control over its mobilization. The Sadrists had a further advantage because the movement’s base was mainly structured around familial networks, which meant that the base tended to be clustered in specific districts that were easily recognizable as Sadrist strongholds.

However, the Sadrists also benefited from two innovations. The first was Bunyan al-Marsous, or “Solid Foundations,” a project launched by the movement several months ahead of the elections. Ostensibly, Bunyan al-Marsous was pitched as an internal reorganization of the movement’s activities and how it interacts with its followers. The project promised to provide Sadrists who registered with their local OMS access to a range of services including a form of health insurance, assistance finding employment, and microloans for economically insecure families or small businesses. However, the registration process also gave the movement detailed data on the distribution and demographics of its support base, including residential addresses and contact phone numbers, allowing the Sadrists to coordinate election instructions at a micro level.

The Sadrist election app was the first of its kind in Iraqi politics.

The second innovation was the launch of the Sadrist election mobile app. This was the first of its kind in Iraqi politics and provided Sadr’s followers with useful information about candidates and which polling stations to vote at. The app included GPS functionality to help navigation to polling stations and thereby ensure higher turnout. (As the new election system divided governorates into multiple subdistricts, it had become important to know which polling station to visit to correctly register a vote.)34

The final element of the Sadrist electoral strategy was the tactical use of independents to split or squeeze out their rivals. In several Basra districts, Fatah candidates lost out to independents who were rumored to have secured tacit agreement from the Sadrists to run in areas of high Sadrist representation.35

Selecting Sadrist Electoral Candidates

The Sadrists have a distinct approach to selecting their electoral candidates. Prospective members of parliament do not apply for the role, nor are they assessed and selected via democratic or competitive party-political mechanisms. Rather, one of Sadr’s representatives within the provincial OMS directly approaches potential candidates to scope their interest in standing. If the individual shows willingness, they are then sent to the Najaf OMS for further vetting and to receive Sadr’s approval and direction. The process is centrally managed by Karimawi and the Political Committee of the Najaf OMS.

Social profiling of Sadrist candidates in Basra indicates that experience and skill as political activists are not qualities that the movement prioritizes in choosing candidates for parliament. Rather, the main criteria are prospective candidates’ track record of Sadrist activism, loyalty to the movement, and willingness to follow orders. Also crucial are prospective candidates’ familial ties and other forms of social connectivity to the movement (such as tribal connectivity).

The Sadrists tend not to recruit significant local personalities with their own popular bases of support. Consequently, Sadrist electoral candidates are often relative unknowns with less public profile and political experience than candidates fielded by other groups. Candidates’ possession of certain types of cultural and social capital is also desirable. For instance, the Sadrists often recruit university professors and other professionals, seeking to benefit from the social prestige of these professions. Strong local tribal links can also make a candidate more attractive.36

There are exceptions to this general pattern. For instance, in more competitive districts Sadrists may want to tap into the additional mobilizing power of certain actors with more personal popular appeal. In such cases, it is more likely to find prominent Sadrist figures from Saraya al-Salam, or those with a significant national profile, selected as candidates.37

Religious Authority

Sadr’s religious-charismatic authority has several important effects in an electoral context. To begin with, it has reduced the movement’s dependence on Islamist political ideology as a mobilizing and legitimating resource. This has insulated the Sadrists electorally from the declining popular appeal of Islamist ideology in Iraqi politics, allowing the movement to short-circuit the causal dependence between effective governance and legitimation that has damaged the Sadrists’ more purely political Islamist rivals.

The political strategy of the Sadrists is mainly geared toward tactical positioning in the contest to dominate elite politics, and not toward advancing an ideological or programmatic version of Islamist politics. This positioning is facilitated by the primacy the movement places on religious authority over political ideology, which in turn explains the Sadrists’ ability to assume multiple and often contradictory political stances, and to engage in a wide variety of electoral strategies, without suffering a critical loss of credibility with the movement’s base.38 In other words, the primacy of religious authority results in greater flexibility in political contexts, allowing the Sadrists to swiftly adapt to shifting opportunities and threats. Being religiously centered has also helped prevent internal schisms over ideological disputes when compared to rivals such as the Dawa Party, or to Lebanon’s Hezbollah.39

As noted above, the Sadrist Movement chooses its candidates for parliament for their proven loyalty to Sadr and historical ties to the movement, and not because they possess their own strong bases of local support. They also tend to be lay activists without a religious background in the hawza. This approach maintains a clear divide between the religious and political figures in the movement, and ensures the subordination of the latter to the former.

As such, Sadrist politicians are largely expendable, and Sadr has sometimes replaced entire swathes of his movement’s members of parliament from one election to another with no detrimental impact on the Sadrists’ electoral performance.40 This system instills discipline on the Sadrist political apparatus, helping to ensure that key political decisions taken by Sadr and the leadership translate smoothly into the desired political action.

Finally, if religious institutions and networks play a bonding function, amplifying solidarity and mediating organizational capacity at the local level, then it is Sadr’s charismatic religious authority that transcends the local and lends greater mobilizing power and coherence to the Sadrist base as a national electoral phenomenon.

Sadrist Electoral Vulnerabilities

The sources of electoral power outlined above explain the Sadrists’ dominant electoral performance in Basra in October 2021. The movement won the most seats (9), and the most votes (87,399). In fact, the movement won more votes than those of the entire Coordination Framework combined (which includes the Fatah Alliance, State of Law, Nasr, Hikma, Fadhila, and others). However, drilling down further into the electoral data at the provincial level reveals potential vulnerabilities for the Sadrists, particularly when thinking about the movement’s longer-term electoral prospects.

The Sadrists saw an overall decline in the vote tally of its electoral platform in 2021. However, this has been somewhat overstated since then, although the Sadrists obtained only 885,310 votes in 2021, down from 1,493,542 in 2018; the 2018 figure includes the votes for non-Sadrist candidates (the Iraq Communist Party and other leftist and liberal parties) who participated in the Sadrists’ Sa’iroun Coalition. While few of these candidates won seats themselves, they nevertheless contributed votes to the total of the Sadrist coalition in 2018.

A closer look at Basra helps clarify what has happened to the Sadrist base in recent years. Here, the Sadrist vote tally between 2018 and 2021 fell from 121,103 to 87,399. However, of the 50 candidates Sa’iroun ran in Basra in 2018, 12 were from secular parties, who contributed 10,147 votes to Sa’iroun’s total. Consequently, the decline in the Sadrist-only vote tally was just 23,557.41 This number is still significant, particularly given the high rates of population growth. However, it should also be considered against a general decline in voter turnout, with around 2 million fewer votes cast in 2021 compared to 2018.

Nevertheless, it was the 2018 election, and not the 2021 vote, that represents the anomaly in terms of Sadrist electoral success. This can be attributed to two main factors. First, in 2018 the Sadrists were able to lead a multiparty coalition rather than relying entirely on their own core base. And second, in 2018 the Sadrists launched their electoral campaign on the back of several years of sustained engagement in pro-reform protest activity. This was a marked contrast to the stance of the movement heading into the 2021 vote, when it was geared toward propping up the administration of the prime minister, Mustafa al-Kadhimi, after Sadrist forces assisted in violently suppressing the Tishreen movement.

The example of Basra suggests that, while the Sadrist base has not dramatically shrunk, it may have peaked in 2018 and is now undergoing a period of stagnation.

Overall, the example of Basra suggests that, while the Sadrist base has not dramatically shrunk, it may have peaked in 2018 and is now undergoing a period of stagnation or slow decline. The 2018 experience indicates that, to reverse this trend, the Sadrists would need to reenergize a younger generation of voters through a more authentic antiestablishment protest politics, and also reconnect with non-Sadrist factions to form a coalition that would add votes from other parties, or independents, to the core Sadrist base.42

The Basra data indicates other potential challenges for the Sadrists. Only one Sadrist candidate was among the top five in the governorate in terms of total votes, and only three were in the top ten. If Tasmeem (the alliance of Basra governor Assad al-Idani) had joined up with the Coordination Framework, their combined votes would have easily outstripped the Sadrist total. In fact, Idani’s vote total alone would have pushed the Coordination Framework above the Sadrists. Tasmeem’s leader, Amer al-Fayaz, was a Fatah member of parliament in 2018 and he scored the fourth-highest overall vote total in Basra in 2021.43

In other words, the Sadrist electoral dominance in Basra was partly a reflection of the fragmentation of its Islamist rivals and their inability to distribute their votes more strategically. However, these are likely non-repeatable factors from which the Sadrists will not benefit again, with the Coordination Framework either changing the election law prior to a future vote, adapting to remedy the mistakes it made in 2021, or both. (See Figure 1 and Figure 2.)

Figure 1

The most popular candidates in Basra were big local personalities—such as Governor Idani, Fayaz and Asa’ib Ahl al-Haq/Fatah politician Uday Awad—with proven track records of effective campaigning on local issues. The success of Awad, who scored far more votes than any individual Sadrist candidate, points to the potential local strength of Fatah. Awad’s popularity in Basra is not primarily explained by the Fatah brand or the ideological appeal of Islamism, Asa’ib Ahl al-Haq, or “resistance” politics. Rather, Awad has built his own popular base by campaigning on more mundane issues such as lobbying in Baghdad on behalf of Basrawis embroiled in various employment disputes.44 If Fatah adapts to the new election law, a consolidation of its ranks around dominant local personalities like Awad is likely to pay dividends at the next election.

Figure 2

Another example that shows the local strength of Fatah is Durgham al-Maliki, another Basra candidate who performed well in the 2021 election. Maliki is well connected to Nouri al-Maliki and State of Law, is a sheikh of the Bani Malik tribe, and the second-most senior figure in the tribe after the tribe’s leader, Sheikh Abdul-Salam al-Maliki. Already a member of parliament, Durgham al-Maliki gained further popularity in Basra for his support for Tishreen protesters after October 2019 (illustrating how the complexities of local politics in Iraq do not always conform to the broad brushstrokes of national-level political narratives).

In contrast to popular local candidates like Idani, Awad, and Durgham al-Maliki, Sadrist candidates rely heavily on the popularity of a single national figure—Sadr himself. This reliance places the Sadrists on the opposite side of an emerging trend in Iraq’s electoral politics toward more locally empowered candidates, whose constituents believe are capable of fixing local issues and delivering practical benefits for their communities. Being less capable of competing in this type of politics may hamper the Sadrists’ prospects in future elections. However, this will also be determined by how far, and in what direction, the political class opts to change the electoral reform law.

Explaining the Sadrist Exception

The Sadrists represent a fascinating case study of Islamist electoral politics in part because the movement’s sustained success over almost two decades breaks with broader trends in the Arab world. In this broader trend, a focus on Sunni Islamism and its failure to turn initial electoral victories after the Arab uprisings into enduring political hegemony has tended to dominate the narrative. Meanwhile, Iraq’s Shia Islamist parties have followed a different, and often overlooked, trajectory by securing their position at the heart of a political system. This Islamist political dominance has been sustained despite the waning popular appeal of Islamist political ideology and Iraqi Islamists’ poor governance record across virtually all typical metrics.

The Sadrists are perhaps the most important part of this apparently paradoxical story of Islamist electoral success in Iraq, providing the state and its electoral politics with connectivity to a popular social base of support that has elsewhere diminished. Yet the Sadrists are also an exception within this picture of Shia Islamist political dominance in Iraq. As an electoral base, the Sadrists have remained remarkably cohesive and disciplined, while the rest of the Shia Islamist bloc has fragmented into a proliferating number of parties and militias. The Sadrists have also remained a religious-political movement in which clerical authority is tightly connected to political activity, at a time when the electorate in general has become more critical of the role of religion in politics.45 The Sadrists also appear uniquely insulated from the reputational damage of poor governance.

Consequently, the factors normally thought to explain the Islamist electoral edge—reputational status, provision of nonstate services, the mobilizing power of religious institutions and networks, and the hegemony of Islamist ideology and identity at a societal level—do not capture the full story of the Sadrists’ electoral power. Nor do they explain variation between the Sadrists and other Shia Islamist factions in Iraq, or between those factions and the broader Islamist scene.

The Sadrists’ electoral success reflects a sophisticated use of election strategy and tactics, allowing the movement to outmaneuver its rivals. This strategic sophistication is linked to the long-term continuity in senior personnel involved in the Sadrists’ development and implementation of election strategy, allowing these actors to accumulate considerable experience, social capital, and practical know-how in their specific field of expertise. This contrasts with a common misconception about Sadr’s operational style in which he is said to have weakened the movement by continually cycling senior positions and demoting his most capable associates.

As this report has shown, state capture and Sadrist penetration of civil society underpin the tactical and strategic aspects of Sadrist electoral politics. State-capture—facilitated by Sadrist connectivity to civil society (as in the case of the Beit Shaya’a)—generates much more financial revenue, and extends the scope of patronage networks much further, compared to more bottom-up processes and resources that draw from religious institutions and practices. At the same time, state capture has allowed Iraq’s Islamist groups, including the Sadrists, to set the rules of political competition in advance, gaining a crucial electoral edge against those excluded from the strategic networks in elite institutions such as the judiciary.46

What sets the Sadrists apart from their Islamist rivals, however, is not only their greater connectivity to civil society, but also Sadr’s distinct form of charismatic ideology. This report has detailed the multiple electoral benefits of this religious factor, ranging from how it has insulated the Sadrists from the reputational damage of poor governance and the waning popular appeal of Islamist political ideology, to how it results in great discipline and cohesion within both the Sadrist political apparatus and the movement’s social base.

Sadr is continually at risk, through his political participation, of having his charisma diluted and becoming a routine politician.

This religious authority also speaks to conceptual discussion about the salience of “Islamism” and “Shia Islamism” as analytical terms for interpreting Iraq’s Shia politics. While the “Islamist-ness” of the Shia political scene in Iraq is increasingly difficult to discern, a powerful religious-political linkage remains in the Sadrist case. Nevertheless, the distinct nature of Sadrist Islamism means that this exception does not disprove the thesis that Islamism as a political ideology or identity is losing traction in Iraq. Rather, the Sadrist exception highlights the variety in forms of Shia Islamism and the diversity of ways in which religion and politics can intersect. These complexities are not captured by simple binaries such as quietism versus activism, Najaf versus Qom, or by the subsuming of Shia political Islam into the meta-category of Khomeinism (also known as Wilayat al-Faqih).

Implications for Policy and Elections

From a policy perspective, the Sadrists’ circumvention of the relationship between effective governance and legitimation is particularly striking. The literature has often taken the quality of governance and normative legitimation of political systems to be bound together and to be fundamental to both sustained electoral power and political stability. The Sadrists, however, illustrate how the governance-legitimation link can be broken by showing there are ways Islamists can build electoral bases and secure political power without necessarily delivering quality governance over the long term. Western analysts have perhaps not fully grasped this fact, due to the tendency of Western secularist discourses—both academic and policy—to apply rationalist and utilitarian frames to political life. This type of discourse has often reduced religion to a tool of political ends, and failed to explore how religion and politics can mutually constitute each other, and how politics can also serve religious purposes or modes of action (for example, an ethical form of action based on duties and sacrifice rather than instrumental or transactional logics).47

Finally, the religious nature of the Sadrist Movement also points to future electoral challenges. The Sadrists prioritize loyalty, discipline, and the maintenance of clerical control when it comes to the movement’s political wing. This means it is rare to find Sadrist politicians with their own large bases of popular support. The electoral performance of candidates for parliament is often precariously tied to the popularity of Sadr himself. Moreover, Sadr is continually at risk, through his political participation, of having his charisma diluted and becoming a routine politician. Consequently, Sadr must always seek to strike a balance between staking out positions in the state and political field, and the need to revivify his authority through forms of activism with more utopian and messianic qualities (for example, certain forms of militancy or protests).

The circularity of this practice can be expected to produce diminishing returns over time, and could be an explanation for the gradual erosion of the Sadrist base among Iraqi youths. The need to combat this erosion could push Sadr and his movement into more radical political positions in the future, as the group shifts from a focus on the tactical management of elite politics to a greater focus on the management of its own base of support.

Notes

- “Shia Islamist rivals” refers to those political parties in the Shia Coordination Framework, but not other parties, such as Tasmeem, or independents, who could be construed a Shia Islamist actors.

- Marc Lynch and Jillian Schwedler, “Introduction to the Special Issue on ‘Islamist Politics After the Arab Uprisings,” Middle East Law and Governance 12 (2020): 3-13. François Burgat, “Were the Islamists Wrong-Footed by the Arab Spring?,” memo for the POMEPS “Rethinking Islamist Politics” conference, January, 24, 2014.

- The quoted definition comes from International Crisis Group, “Understanding Islamism,” Middle East/North Africa Report No. 37, March 2, 2005, crisisgroup.org/middle-east-north-africa/understanding-islamism.

- See Fanar Haddad’s report in this series, on Shia politics, forthcoming this fall.

- For instance, in 2016 the Iraqi parliament passed a law banning the manufacture and sale of alcohol “to preserve Iraq’s identity as a Muslim country,” according to one Shia Islamist member of parliament. However, the law has never been enforced, in part because the Islamists themselves are the main financial beneficiaries of Iraq’s liquor trade.

- Benedict Robin-D’Cruz and Renad Mansour, “Making Sense of the Sadrists: Fragmentation and Unstable Politics,” The Foreign Policy Research Institute, 2020, https://www.fpri.org/article/2020/03/making-sense-sadrists-fragmentation-unstable-politics/; Nicholas Krohley, The Death of the Mehdi Army: The Rise, Fall, and Revival of Iraq’s Most Powerful Militia (London: C. Hurst, 2015); Paul Staniland, Networks of Rebellion: Explaining Insurgent Cohesion and Collapse (London: Cornell University Press, 2014); Marisa Cochrane, “The Fragmentation of the Sadrist Movement,” Institute for the Study of War, 2009, https://www.understandingwar.org/report/fragmentation-sadrist-movement.

- For example, the splits involving Ayatollah Muhammad al-Yacoubi, Qais al-Khazali, Akram al-Kaabi, Shibl al-Zaidi, and Sheikh Muhammad Tabatabai, Isma’il Hafiz al-Lami (also known as Abu Dura), among many others.

- Melani Cammett and Pauline Jones Luong, “Is There an Islamist Political Advantage?,” Annual Review of Political Science 17 (2014): 187–206; Toygar Sinan Baykan, “Electoral Islamism in the Mediterranean: Explaining the Success (and Failure) of Islamist Parties,” Mediterranean Politics 25, no. 5 (2020): 690–96; Steven Brooke, Winning Hearts and Votes: Social Services and the Islamist Political Advantage (New York: Cornell University Press, 2019); Melani Cammett, Compassionate Communalism: Welfare and Sectarianism in Lebanon (New York: Cornell University Press, 2014).

- Robin-D’Cruz and Mansour, “Making Sense of the Sadrists;’; Benedict Robin-D’Cruz, “The Prophetic Power of Muqtada al-Sadr: Theorizing the Role of Religion in Shii Islamist Politics,’ unpublished manuscript; see also chapter three in Benedict Robin-D’Cruz, “The Leftist-Sadrist Alliance; Social Movements and Strategic Politics in Iraq” (PhD diss., University of Edinburgh, 2019).

- “Electoral success” is taken to mean not merely tallying votes, but how electoral politics translates into political power. As will be shown, the Sadrists excel at maximizing the power of each vote, even while their gross vote tally declined from 2018 to 2021.

- See chapter two in Frank Ledwidge, Losing Small Wars: British Military Failure in Iraq and Afghanistan (London: Yale University Press, 2011).

- Basra-based source, interview with the author, multiple communications between 2020 and 2022.

- Ibid.

- Basra-based source, interview with the author, August 2022.

- Marisa Cochrane, The Fragmentation of the Sadrist Movement (Washington, DC: Institute for the Study of War, 2009), 12.

- Basra-based source, interview with the author via multiple communications between 2020 and 2022; anonymous sources, interviews with the author, last updated August 2022.

- Basra-based source, interviews with the author via multiple communications, last updated via electronic communication in June 2021.

- Basra-based source, interviews with the author via multiple communications between 2020 and 2022; supplemented by the author’s own monitoring of this protest activity.

- Basra-based sources, interview with the author via multiple communications between 2020 and 2022; analysis of Sadrists’ Basra social media sites and communications from Muqtada al-Sadr announcing appointments to key positions within the movement.

- For example, see recent commentary by Abbas Kadhim (@DrAbbasKadhim) via Twitter thread, posted on August 29, 2022, https://twitter.com/DrAbbasKadhim/status/1564319677374861312?s=20&t=k_nufZIxi7xG-amQIaPrng.

- Basra-based source, interview with the author, April 2021.

- Basra-based source, interview and regular communication with the author, last updated in August 2022.

- These examples were taken from messaging from the prominent Sadrist Twitter account Salih Mohammad al-Iraqi (@salih_m_iraqi, https://twitter.com/salih_m_iraqi), a proxy account for Sadr himself.

- A common tactic, deployed particularly by Sadr’s proxy Twitter account Salih Mohammad al-Iraqi (ibid.), was to associate the Tishreeni activists with alcohol and drug abuse. Sadr also condemned the mixing of men and women at protests, calling for gender segregation of Sadrist protesters.

- Benedict Robin-D’Cruz, “The Social Logics of Protest Violence in Iraq: Explaining Divergent Dynamics in the Southeast,” London School of Economics, September 2021, http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/111784/2/SocialLogicsofProtestViolence.pdf.

- Benedict Robin-D’Cruz and Renad Mansour, “Why Muqtada al-Sadr Failed to Reform Iraq,” Foreign Policy, March 10, 2022, https://foreignpolicy.com/2022/03/10/why-muqtada-al-sadr-failed-to-reform-iraq/.

- Renad Mansour and Benedict Robin-D’Cruz, “Understanding Iraq’s Muqtada al-Sadr: Inside Baghdad’s Sadr City,” Chatham House, August 8, 2022, https://www.chathamhouse.org/2022/08/understanding-iraqs-muqtada-al-sadr-inside-baghdads-sadr-city.

- “Iraq’s October 2021 Election,” Congressional Research Service, October 18, 2021, https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/IN/IN11769#:~:text=Under%20a%20new%20voting%20law,seats%20reserved%20for%20minority%20groups; Renad Mansour and Victoria Stewart-Jolley, “Explaining Iraq’s Election Results,” Chatham House, October 22, 2021, https://www.chathamhouse.org/2021/10/explaining-iraqs-election-results.

- Fatah lost former members of parliament who opted to stand as independents or in new, more localized blocs such as Tasmeem in Basra. It also ran too many candidates from its component parties in each district, spreading its vote base too thinly while its most dominant personalities sucked up more votes than needed, and were unable to distribute their excess votes to other candidates in their coalition (as would have happened under the old closed and open-list systems).

- Two non-Sadrist Iraqi sources with in-depth knowledge of Karimawi’s background and role as an election strategist, remote interviews with the author, September 2022.

- Iraqi researcher with first-hand knowledge of Karimawi’s role, interview with the author, September 2022.

- Mohanad Adnan, an Iraq-based political analyst who conducted close analysis of the election strategies of various political parties during the October 2021 election, remote interview with the author, September 15, 2022. Adnan also indicated that the fourth tier of the Sadrist strategy was areas where no candidates were run, mainly due to the low chances of winning a seat but also to build political capital for the post-election alliance formation strategy by not competing against potential coalition partners.

- Personal communications between the author and several Basra-based sources during the election campaign in 2021, anonymized.

- Hamdi Malik has noted that this was particularly important in 2021 given that the new electoral system had radically changed where and how voters were to cast ballots, leading to potential confusion and apathy.

- One example would be independent member of parliament Mustafa Jabbar Sanad, who came third in District One with 8,339 votes. Sanad has connections to the Sadrists through the Al Marayan tribe, and family connections to former prime minister Adil Abdul-Mahdi. Since gaining his seat in parliament, however, Sanad has drawn closer to the Coordination Framework and openly clashed with the Sadrists, illustrating how fluid tactical political allegiances can be.

- Many of these features can be seen in the Sadrist candidates who ran in Basra in 2021. Examples include Ayad al-Muhamadawi al-Muslikh and Wafaa al-Mayahi, who are both academics at the University of Basra with personal or familial connections to Saraya al-Salam and long histories of Sadrist activism.

- Adnan, interview.

- The best example of this was the Sadrists adaptation to the rising popularity of “madani” (“civil”) politics between 2015 and 2018, only to reverse course for a religion-focused electoral strategy in 2021.

- On the Dawa Party, see Harith Hassan, “From Radical to Rentier Islamism: The Case of Iraq’s Dawa Party,” The Carnegie Middle East Center, April 16, 2019, https://carnegie-mec.org/2019/04/16/from-radical-to-rentier-islamism-case-of-iraq-s-dawa-party-pub-78887. On Hezbollah, see Jason Wimberly, “Wilayat al-Faqih in Hizballah’s Web of Concepts: A Perspective on Ideology,” Middle Eastern Studies 51, no. 5 (2015): 687–710

- Many of these features can be seen in the Sadrist candidates who ran in Basra in 2021. Examples include Ayad al-Muhamadawi al-Muslikh and Wafaa al-Mayahi.

- Based on analysis of figures provided by Kirk Sowell and published in his Inside Iraqi Politics 65, 2018.

- As explored in my forthcoming paper with Renad Mansour, the Sadrist base remains split in its views on Tishreen, with considerable support for the protest movement among younger members of the movement despite sustained rhetorical attacks on Tishreen by the Sadrist leadership. See Benedict Robin-D’Cruz and Renad Mansour, “The Sadrists and Iraq’s Tilt Towards Chaos,” Chatham House, forthcoming.

- Idani could be construed as a natural ally of the Coordination Framework, having been close to both Hikma and Nasr, and was considered a potential prime minister candidate for the Binaa Bloc (Fatah and State of Law) after Adil Abdul-Mahdi resigned as prime minister. However, Idani is politically fluid and has made considerable efforts to build his Sadrist relationships since the October 2021 election left the Sadrists and Tasmeem as the two dominant political forces in Basra.

- Awad has been involved in several campaigns of this sort, but his most prominent and successful has been working alongside Sheikh Ammar al-Zaidi on behalf of the so-called “30,000”, a large group of Basrawis promised jobs under Governor Idani’s jobs lottery scheme, who have subsequently been campaigning to have their contracts upgraded to permanent public sector employment.

- See survey data for Iraq from Arab Barometer, Wave V 2018, questions on political Islam, https://www.arabbarometer.org/survey-data/data-analysis-tool/.

- The Sadrists’ comparative lack of judicial power compared to Nouri al-Maliki has also been a crucial factor explaining how Maliki has been able to unravel the Sadrists’ attempt to translate their 2021 electoral success into government formation.

- This notion of Sadrist activity as sacrificial practice draws on the author’s conversations with Elizabeth Tsurkov, who is currently researching the Sadrist trend. Personal communication, September 2022.