Since the disclosures of Edward Snowden in 2013, the U.S. government has assured its citizens that the National Security Agency (NSA) cannot spy on their electronic communications without the approval of a special surveillance judge. Domestic communications, the government says, are protected by statute and the Fourth Amendment.1 In practice, however, this is no longer strictly true. These protections are real, but they no longer cover as much ground as they did in the past.

When Congress wrote the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act (FISA) in 1978,2 it was trying to set a short leash on the NSA at home and a long one overseas.3 The NSA could not tap into communications inside the United States without following strict rules, but it had a free hand to intercept data elsewhere. Even now this sounds like common sense. The NSA is not supposed to spy at home, but spying abroad is central to its job. One policy problem we face today, however, is that the realities of the modern Internet have blurred the distinction between spying at home and spying abroad.

The modern Internet tends to be agnostic to geopolitical borders. There are multiple alternate routes from any Internet-connected machine to any other. Internet traffic travels along the cheapest or least-congested route, not the shortest route.4 Internet data is backed up in data-centers located around the globe, so that data can be recovered even in the face of local disasters (power outages, earthquakes, and so on).5 For these reasons, it is commonplace for purely domestic communications to cross international boundaries. An email sent from San Jose to New York may be routed through Internet devices located in Frankfurt,6 or be backed up on computers located in Ireland.7

International detours and routing changes happen automatically, without human intervention. Even so, they offer an opportunity to the NSA. With some exceptions, the surveillance of raw Internet traffic from foreign points of interception can be conducted entirely under the authority of the president. Congressional and judicial limitations come into play only when that raw Internet traffic is used to “intentionally target a U.S. person,” a legal notion that is narrowly interpreted to exclude the bulk collection, storage, and even certain types of computerized data analysis.8 This is a crucial issue, because American data is routed across foreign communications cables. Several leading thinkers,9 including Jennifer Granick in her recent report for The Century Foundation, have drawn attention to the creeping risk of domestic surveillance that is conducted from afar.

This report describes a novel and more disturbing set of risks. As a technical matter, the NSA does not have to wait for domestic communications to naturally turn up abroad. In fact, the agency has technical methods that can be used to deliberately reroute Internet communications. The NSA uses the term “traffic shaping” to describe any technical means the deliberately reroutes Internet traffic to a location that is better suited, operationally, to surveillance. Since it is hard to intercept Yemen’s international communications from inside Yemen itself, the agency might try to “shape” the traffic so that it passes through communications cables located on friendlier territory.10 Think of it as diverting part of a river to a location from which it is easier (or more legal) to catch fish.

The NSA has clandestine means of diverting portions of the river of Internet traffic that travels on global communications cables.

Could the NSA use traffic shaping to redirect domestic Internet traffic—emails and chat messages sent between Americans, say—to foreign soil, where its surveillance can be conducted beyond the purview of Congress11 and the courts? It is impossible to categorically answer this question, due to the classified nature of many national-security surveillance programs, regulations and even of the legal decisions made by the surveillance courts. Nevertheless, this report explores a legal, technical, and operational landscape that suggests that traffic shaping could be exploited to sidestep legal restrictions imposed by Congress and the surveillance courts.

How Did We Get Here?

The Fourth Amendment of the U.S. Constitution has led to some strong protections for domestic communications. If, for example, the Federal Bureau of Investigations (FBI) wants to monitor electronic communications between two Americans as part of a criminal investigation, it is required by law to obtain a warrant.12 If the intelligence community wants to intercept Americans’ communications inside the United States, for national security reasons, then it must follow rules established by the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act (FISA).13

Meanwhile, when the intelligence community wants to intercept traffic abroad, its surveillance is mostly regulated by Executive Order 12333 (EO 12333),14 issued by Ronald Reagan in 1981.15 Surveillance programs conducted under FISA are subject to oversight by the FISA Court and regular review by the intelligence committees in Congress. Meanwhile, surveillance programs under EO 12333 are largely unchecked by either the legislative16 or judicial branch. Instead, EO 12333 programs are conducted entirely under the authority of the president. Moreover, the implementing guidelines for programs under EO 12333 offer fewer protections for Americans’ privacy than those under FISA.17

In other words, one set of rules apply for surveillance of communications intercepted at home, and another set altogether for communications intercepted abroad.

This distinction made sense when FISA and EO 12333 were first established in the 1970s and 1980s. Back then, spying on a foreign target typically meant intercepting communications overseas, and spying on American targets meant intercepting communications on U.S. soil. Today, however, Internet technologies have largely obviated these distinctions. The modern Internet has allowed Americans to communicate in a manner that is largely agnostic to geopolitical boundaries.

Where Do We Go From Here?

The modern Internet has changed the way that Americans communicate. These changes call for a fundamental realignment of U.S. surveillance law. Specifically, the legal boundaries that distinguish interception of Internet traffic on U.S. territory from interception abroad must be broken down. Americans’ Internet traffic should enjoy the same legal protections, regardless of whether it is intercepted on U.S. territory, or intercepted abroad.

We have seen these legal boundaries break down when it suits the purpose of intelligence community. A decade ago, FISA surveillance required warrants18 from the FISA Court. In 2008, however, FISA was amended to allow warrantless surveillance on U.S. territory, as long as the operation acquires “foreign intelligence” and does not “intentionally target a U.S. person.”19 In 2007, J. Michael McConnell, the director of national intelligence, advocated for this by stating that:

FISA originally placed a premium on the location of the collection. Legislators in 1978 could not have been expected to predict an integrated global communications grid that makes geography an increasingly irrelevant factor. Today a single communication can transit the world even if the two people communicating are only a few miles apart.20

Exactly the same argument applies in reverse. The fact that “geography is an increasingly irrelevant factor” similarly justifies protections for American’s communications when their traffic is intercepted abroad. Indeed, there is evidence that indicates that if authorities have the option to collect the same Internet traffic in the United States (under FISA) or abroad (under EO 12333), they may opt to collect the traffic abroad under the more permissive EO 12333 rules.21 In that scenario, the NSA can take advantage of looser restrictions when it happens to find U.S. communications overseas.

Moreover, the NSA does not need to wait until U.S. communications happen to turn up overseas. Instead, the NSA could use “traffic-shaping” techniques to deliberately send traffic from within the U.S to points of interception on foreign territory, where it could be swept up as part of operations that would be illegal if conducted on U.S. territory. Given the classified nature of the agency’s work, and even of its interpretations of the law, it is impossible to categorically determine if the NSA is currently using traffic shaping for this purpose. Nevertheless, this report presents an interpretation of the law suggesting that operations that “shape” American traffic from U.S. territory to abroad might be regulated entirely by EO 12333.

This presents a serious policy issue. Fortunately, there is an upcoming opportunity to address this issue, when portions of the 2008 FISA Amendments Act come up for renewal in December 2017. While the law appears to be silent on traffic shaping, the renewal debate will offer an opportunity for Congress to take up this question. Congress could expand FISA to cover the surveillance of any and all traffic collected abroad.

To do this, Congress could revise the definition of “electronic surveillance” in the text of the FISA statute, which determines the types of surveillance that are regulated by FISA. FISA’s definition of “electronic surveillance” has hardly been updated since 1978. The definition ought to be modernized so that it is neutral on the geographic location where traffic is intercepted, and also neutral on the specifics of the technologies used to intercept that traffic. By modernizing this definition, Congress could disentangle the legal protections for Americans from the vagaries of the rapidly-evolving technologies that Americans use for their communications.

This report starts with a look at FISA, which largely regulates surveillance on U.S. territory. It then describes EO 12333, which largely regulates surveillance abroad. EO 12333 surveillance is subject to fewer legal restraints than surveillance under FISA. The report then discusses why Internet traffic from U.S. persons might naturally flow abroad, where it can be swept up as part of bulk surveillance programs under EO 12333. The report then looks at documents that suggest that, when authorities have the choice of collecting the same Internet traffic under FISA (on U.S. soil) or under EO 12333 (abroad), they may choose the more permissive EO 12333 regime. Thus, when American traffic naturally flows abroad, EO 12333 can be used to circumvent the legal restrictions in FISA. The report then considers what is known about NSA’s traffic shaping capabilities, and how they might lawfully be used to reroute traffic from inside U.S. borders to foreign soil. The report then concludes with several policy recommendations that can protect American traffic when it is collected on foreign soil.

The Legal Authorities Governing Internet Surveillance

A layperson reading the text of the Fourth Amendment might naturally conclude that the government needs a warrant whenever it conducts surveillance.22 However, over two centuries of legal precedent and legislation have passed since the Bill of Rights was first adopted, defining whether and how the Fourth Amendment applies in various situations. One important legal principle, established by the U.S. Supreme Court, holds that that the Fourth Amendment does not apply to foreign individuals located outside U.S. territory.23

This principle—that foreign individuals located outside the United States are not protected by the Fourth Amendment—is reflected in the complex web of legal authorities that regulate Internet surveillance.

This principle—that foreign individuals located outside the United States are not protected by the Fourth Amendment—is reflected in the complex web of legal authorities that regulate Internet surveillance. This report focuses on two of these legal authorities—FISA and EO 12333—each of which comes with its own underlying set of legal interpretations, precedents, and policies, some of which are classified.24 This section first discusses each legal authority, and then describes why modern Internet technologies have caused a blurring of the purviews of these two distinct legal authorities.

The Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act (FISA)

The Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act (FISA) was signed into law in 1978 during the Carter administration, primarily as a reaction to the intelligence abuses that came to light during the 1970s.25 FISA was intended to “relieve all Americans of that dread of unchecked surveillance power and that fear of unauthorized official eavesdropping”26 by providing judicial and legislative oversight for government surveillance. FISA established the non-public FISA Court, which issues warrants27 for surveillance on U.S. territory when “a significant purpose of the surveillance is to obtain foreign intelligence information.”28 FISA Court decisions are typically classified.29

When FISA was first passed in 1978, legislators supposed that surveillance operations conducted on domestic territory were mostly likely to affect Americans. Because the Fourth Amendment applies to Americans located on domestic territory,30 the original FISA statute generally required warrants31 from the FISA Court for operations conducted on domestic territory.

In 2008, this policy shifted when Congress passed the FISA Amendment Act (FAA). The FAA introduced Section 702, which allows warrantless surveillance on U.S. soil, as long as the operation acquires “foreign intelligence” and does not “intentionally target a U.S. person.” Importantly, the legal notion of “intentional targeting” does not rule out large-scale warrantless surveillance of Americans.32 Passage of the FAA was motivated, in part, by the fact that Internet traffic tends to ignore geopolitical borders. Specifically, the intelligence community argued33 that foreigners’ traffic that crosses the U.S. borders could be surveilled without a warrant, because the Fourth Amendment does not apply to foreigners.

When the FAA was brought to a vote, it was met with opposition from number of legislators. As a concession to these legislators, the FAA was amended to include a “reaffirmation that FISA is the ‘exclusive’ means of conducting intelligence wiretaps—a provision that . . . would . . . prevent eva[sion] of court scrutiny.”34 However, a deeper look at this exclusivity clause indicates that it is less protective than may initially appear. Specifically, “exclusivity” only applies to “electronic surveillance,” a legal term that is narrowly defined in the text of the FISA statute.35 Among other things, FISA’s definition of “electronic surveillance” does not cover tapping communication cables located abroad for the purpose of obtaining “foreign intelligence” that does not “intentionally target a U.S. person.”36

Executive Order 12333

When the NSA conducts the majority of its SIGINT activities (that is, “signals intelligence,” or intelligence-gathering by interception of electronic signals), it does so pursuant to the authority provided by Executive Order (EO) 12333, first issued in 1981 by the Reagan administration.37

EO 12333 falls solely under the executive branch, and is generally more permissive than FISA.38 One key distinction is that programs under FISA are subject to review by the FISA Court. FISA violations must be reported to the court, and violators can face criminal liabilities. Programs conducted under EO 12333, however, are not reviewed by any court, and violators are subject only to internal sanctions, not criminal charges.39

This is a crucial point. The laws governing surveillance date back to 1970s and 1980s—long before the Internet was popularly used for personal communications—and are therefore inherently ambiguous about modern surveillance techniques and their lawfulness. Under FISA, any such ambiguities can be resolved on a case-by-case basis in front of the FISA Court. Under EO 12333, however, these ambiguities are dealt with internally, by lawyers and policymakers whose job it is to maximize the effectiveness of surveillance operations. By avoiding judicial review and the potential for criminal penalties, EO 12333 creates a much more favorable environment for surveillance.

Surveillance under EO 12333 is not without limits and boundaries. It is subject to self-imposed rules created by the executive branch and the intelligence community. It must be conducted abroad and must not “intentionally target a U.S. person.”40 So, to properly understand EO 12333 surveillance, we need to understand how the intelligence community interprets the legal notion of “intentional targeting.”

Intentional Targeting under EO 12333

As it turns out, the intelligence community’s interpretation of “intentional targeting” is pretty permissive. It does not, for example, rule out bulk collection, storage,41 and even certain types of algorithmic analyses42 of Internet traffic that it collects abroad—even if this traffic is American in origin, containing stockpiles of data about U.S. persons.

Instead, “targeting” is interpreted as occurring only when an analyst searches this data by applying a “selector” that implicates a specific individual, group, or topic.43

The narrow interpretation of “targeting” has significant implications on privacy for U.S. persons. For instance, the NSA has built a “search engine”44 that allows analysts to hunt through raw data collected in bulk through various means. If a human analyst uses that search engine to search for communications linked to a specific email address, Facebook username, or other personal identifier—a “selector”45—then that counts as “intentional targeting.” However, if an analyst obtains information using search terms that do not implicate a single individual—for example, words or phrases such as “Yemen” or “nuclear proliferation”—the communications swept up as part of this search, such as an email between two Americans discussing current events in Yemen, are not considered to be “intentionally targeted.”46 Instead, these communications are merely “incidentally collected.”47

U.S. surveillance techniques are classified, which prevents outside observers from making categorical statements about how far the intelligence community stretches this notion of “incidental collection.” However, John Napier Tye, a former U.S. State Department official who had access to classified information about EO 12333, described one possible interpretation of “intentional targeting”:

Hypothetically, under 12333 the NSA could target a single foreigner abroad. And hypothetically if, while targeting that single person, they happened to collect every single Gmail and every single Facebook message on the company servers not just from the one person who is the target, but from everyone—then the NSA could keep and use the data from those three billion other people. That’s called “incidental collection.” I will not confirm or deny that that is happening, but there is nothing in 12333 to prevent that from happening.48

While it is remains unclear exactly how far the intelligence community stretches the notion of “incidental collection,” even the interpretation of what constitutes “collection” itself seems to create a favorable environment for large-scale surveillance. That is, when intelligence agencies obtain and store data from a tapped communications cable, this data is not even considered to be “collected” until it is processed and analyzed.49

The remainder of this report considers surveillance that is not “intentionally targeted,” yet nevertheless still significantly implicates the privacy of Americans.

How Can Surveillance under EO 12333 Impact Americans?

In 1981, when EO 12333 was first issued, one could have concluded American communications are unlikely to be “incidentally collected” as part of bulk surveillance operations conducted on foreign soil. Today, this is no longer the case.50 The Internet is agnostic to national borders: communications between two persons in the same country sometimes cross into other countries, as networks seek the most-efficient, least-congested, or lowest-cost route from sender to recipient.

How Americans’ Internet Traffic Typically—and Commonly—Flows Abroad

The collection of communications between Americans on U.S. territory is governed by FISA.51 However, if those same communications can be “incidentally collected” abroad, then collection is governed by EO 12333.52 But how do communications between two Americans typically travel abroad?

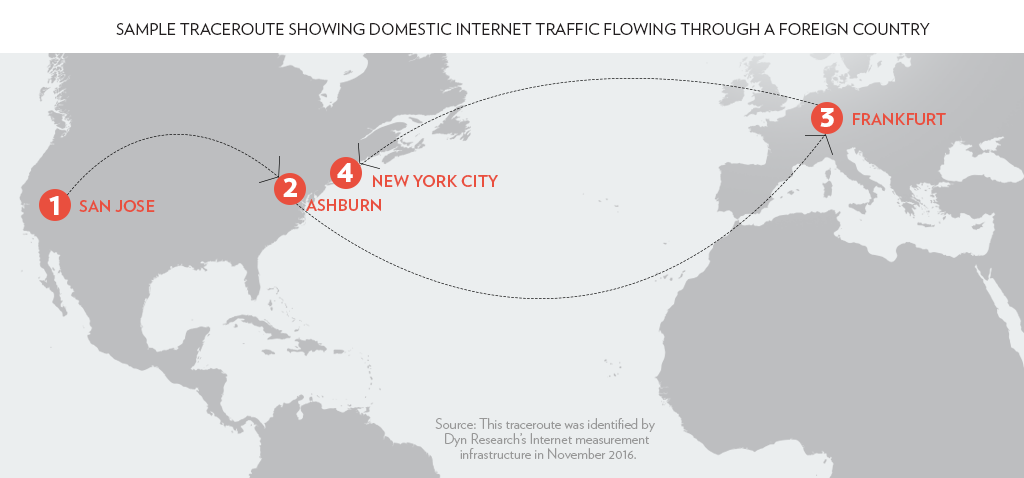

It can sometimes be faster or cheaper for Internet service providers to send traffic through a foreign country. The United States has a well-connected communications infrastructure, so it is rare to find a case where traffic sent between two domestic computers naturally travels through a foreign country. Nevertheless, these cases do occur. One such case (identified by Dyn Research’s Internet measurement infrastructure) is presented in Figure 1.

The “traceroute” presented in Figure 1 shows how Internet traffic sent between two domestic computers travels through foreign territory. The traffic originates at a computer in San Jose and is routed through Frankfurt before arriving at its final destination in New York. The left column shows the Internet Protocol (IP) address of each Internet device on the route, the middle column names the Internet Service Provider (ISP) that owns this device, and the right column shows the location of the device.

FIGURE 1.

Replicating U.S.-based data in foreign data centers is a common industry practice, in order to ensure that data can be recovered even in the face of local disasters (power outages, earthquakes, and so on).53 Google, for instance, maintains data centers in the United States, Taiwan, Singapore, Chile, Ireland, the Netherlands, Finland, and Belgium, and its privacy policy states: “Google processes personal information on our servers in many countries around the world. We may process your personal information on a server located outside the country where you live.”54 If two Americans use their Google accounts to communicate, their emails and chat logs may be backed up on Google’s data centers abroad, and thus can be “incidentally collected” as part of EO 12333 surveillance.

FIGURE 2.

In fact, this is not a hypothetical scenario. In October 2013, the Washington Post reported that the NSA tapped communication cables between Google and Yahoo! data centers located abroad, sweeping up over 180 million user communications records.55 According to the Washington Post, “NSA documents about the effort refer directly to ‘full take,’ ‘bulk access’ and ‘high volume’ operations.” Crucially, this collection was performed abroad. Meanwhile, a FISA Court ruling from 2011 suggests this operation would have been illegal had it been performed on U.S. territory.56

The Vulnerability of Americans under EO 12333

How many American communication records are swept up as part of bulk surveillance programs conducted abroad under EO 12333? It is hard to know. In August 2014, officials told the New York Times that “the NSA had never studied the matter and most likely could not come up with a representative sampling.”57 However, there is clear evidence suggesting that the NSA does analyze U.S. person data that is “incidentally collected” under EO 12333.

U.S. surveillance law applies weaker legal protections to communications metadata (information about who contacts who, when and for long) than to communications contents (information contained in the messages themselves). This issue is crucial to the policy issues considered by this report, because analysis of metadata collected under EO 12333 is far less restrained than analysis of metadata collected under FISA.

Why is there a distinction between content and metadata? The notion that communications metadata deserves weaker privacy protections dates back to 1979, when our computers were much less powerful.58 Today, however, computer scientists have shown that subjecting large volumes of metadata to powerful algorithmic analysis can be very invasive of individual privacy.59 In fact, General Michael Hayden, former director of the NSA, has famously said that “We kill people based on metadata.”60 Nevertheless, communications metadata continues to enjoy weaker legal protections than communications content.

“Former NSA Boss: ‘We kill people based on metadata.’” Source: YouTube.

How does this play out under EO 12333? If the contents of an American’s communication are “incidentally collected” under EO 12333, then human analysts are generally required to redact (or “mask” or “minimize”) that information out of intelligence reports.61

Meanwhile, the NSA’s procedures for dealing with metadata collected under EO 12333 are far less stringent. For instance, the NSA’s procedures under EO 12333 allow for “contact chaining” of metadata, using information about who communicates with whom to map out the relationships between individuals. Prior to 2010, the NSA was required to stop “contact chaining” once the chain encountered metadata belonging to an American. In 2010, the Obama administration unilaterally reversed this policy, allowing the NSA to use U.S. person information in contact chains that are derived from metadata “incidentally collected” under EO 12333.62 Just before leaving office, the Obama administration further expanded this authority beyond just the NSA to the entire intelligence community (including the CIA, FBI, DHS, DEA, among other agencies), permitting “communications metadata analysis, including contact chaining, of raw [EO 12333] data . . . for valid, documented foreign intelligence or counterintelligence purposes . . . without regard to the location or nationality of the communicants.”63

This is expansion of authority to use “contact chaining” under EO 12333 is significant, because the USA FREEDOM ACT of 2015 forbids contact chaining for more than two “hops” away from a target, when using metadata from telephone-call records that were collected on U.S. soil. (That is, the chain may only include the “intentional target,” all of the target’s contacts, and all of the contacts’ contacts.) Meanwhile, under EO 12333, the intelligence community may create contact chains of unlimited length. Moreover, while contact chaining under the USA FREEDOM Act may be done only for counterterrorism purposes, under EO 12333, a “foreign intelligence” purpose suffices. The latter creates more latitude for surveillance, because the EO 12333 definition of “foreign intelligence” is broad, covering information “relating to the capabilities, intentions and activities of foreign . . . organizations or persons.”64

In other words, the reforms embodied in the USA FREEDOM ACT, which extend greater privacy protections to Americans, can be sidestepped when the metadata of U.S. persons is collected on abroad, rather than on U.S. territory.65

Is EO 12333 Being Used as an End Run around FISA?

There is further evidence that EO 12333 authority has been used to sidestep the protections for U.S. persons under FISA. Journalist Marcy Wheeler points to a 2011 NSA training module that instructs analysts to run their intended searches on both FISA data and EO 12333 data. If identical results are found, analysts are told that they may want to share them using the more permissive rules for disseminating information under EO 12333, rather than the more restrictive FISA rules.66 The module also includes the following training question:

TRUE or FALSE: If a query result indicates that the source of information is both Executive Order 12333 collection and [FISA] collection, then the analyst must handle the E.O. 12333 result according to the [FISA] rules.

a) True

b) False

The module indicates that the correct answer is “False.”

There is a particularly telling detail that may corroborate suspicions that authorities are turning to EO 12333, rather than FISA, to conduct surveillance. In 2011, the NSA shut down a program that was collecting American email metadata, in bulk, on U.S. territory. This program was overseen by the FISA Court. The New York Times and Marcy Wheeler point to documents indicating that the program was shut down, in part, because “other [legal] authorities can satisfy certain foreign intelligence requirements” that the bulk email records program “had been designed to meet.” One of these legal authorities is the rules for collecting metadata on foreign territory under EO 12333.67

Finally, in April 2017, the NSA “stopped some its activities” under FISA that collect U.S. persons’ communications on U.S. territory,68 where “Americans’ emails and texts [are] exchanged with people overseas that simply mention identifying terms—like email addresses—for foreigners whom the agency is spying on, but are neither to nor from those targets.”69 According to the NSA, a motivation for halting this program was a “several earlier, inadvertent . . . incidents related to queries involving U.S. person information”70 that failed to comply with the rules laid out by the FISA Court. However, the New York Times reported that “there was no indication that the N.S.A. intended to cease this type of collection abroad, where legal limits set by the Constitution and [FISA] largely do not apply.”71

These examples suggest that authorities can sidestep the judicial oversight required by FISA, simply by intercepting traffic on foreign territory. But this raises an interesting question: What would happen to Americans’ privacy rights if an increasing portion of the flow of American communications were somehow diverted onto foreign territory?

Traffic Shaping to Force U.S. Persons’ Communications Abroad

As stated earlier, American Internet traffic can sometimes be routed abroad, naturally, in the name of efficiency, or when Americans view content that is hosted or stored on computers located in other nations. But American Internet traffic can also be deliberately diverted onto foreign territory by exploiting modern Internet technologies. The NSA uses the term “traffic shaping” to describe any technical method that is used to redirect the routes taken by Internet traffic.72

It is conceivable that traffic shaping could be used as a method to redirect American Internet traffic from within the United States to a tapped communication cable located on foreign soil. This traffic could then be “incidentally collected” from the foreign cable under EO 12333, and thus could be stored, analyzed, and disseminated under the more permissive EO 12333 rules.

Does the NSA does have the technical capability to perform traffic shaping? There is sufficient evidence to suggest that they do. That said, there is no evidence that the NSA is using traffic shaping to deliberately divert U.S. traffic to foreign soil. Indeed, there also has been no public discussion of whether the NSA believes that it is even legal to use traffic shaping to redirect American Internet traffic abroad. In fact, it is unclear even how traffic shaping could be authorized under the NSA’s current legal authorities. Nevertheless, the possibility exists, and so it would be valuable to review the several techniques that can be used for traffic shaping, and explore a possible interpretation of the law that suggests that their use could be regulated entirely by EO 12333.

The legal argument rests on several issues that have not been decided by the courts (at least not publicly). Nevertheless, the key takeaway point is that FISA is outdated. Because FISA is over three decades old, it is ambiguous about modern surveillance technologies like traffic shaping. There is therefore a possibility that the intelligence community could conclude that traffic shaping is not regulated by FISA. If that were case, then the ambiguities concerning what is legal or not would be settled entirely within the executive branch and the intelligence community, and any traffic shaping program would avoid the scrutiny of the FISA Court.

Traffic Shaping by “Port Mirroring” at Hacked Routers

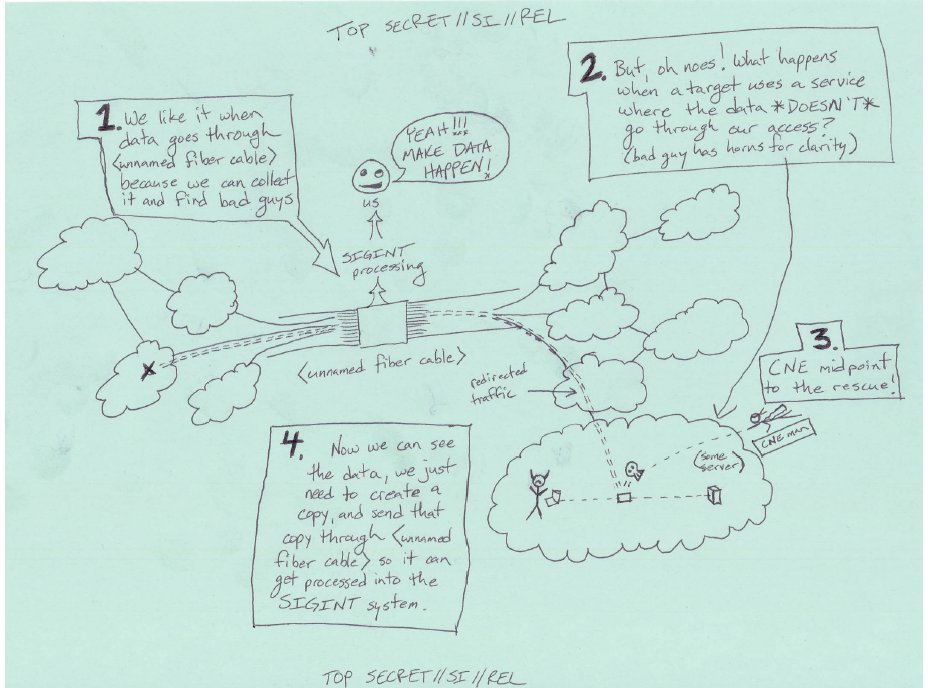

It has been reported that the NSA already employs a technique to “shape” traffic so that it travels through a tapped communication cable. The traffic-shaping technique involves hacking into an Internet infrastructure device, for example, a router. A router is a device that forwards Internet traffic to its destination.73 In Figure 3, which was hand-drawn by a hacker employed by the NSA and later leaked, the hacked device74 is called a “CNE midpoint.”75

The NSA likely does not read, analyze, collect, or store traffic at a hacked router—routers are very limited devices that typically can only pass traffic along. Instead, the router is simply instructed the router to copy the traffic and pass it along to a tapped communication cable where the actual eavesdropping occurs.76 The original traffic still travels on its usual path to the destination. However, the traffic is additionally copied and passed on to an additional destination determined by the NSA. Network engineers call this process “port mirroring.”77

Figure 3

It is important to remember that the router being hacked is not a personal communications device. A router is just a waypoint on the Internet infrastructure that forwards traffic aggregated from multiple sources. Because traffic from many individuals is aggregated at a single router, one could easily argue that hacking into a router does not “intentionally target a U.S. person.”78

Furthermore, traffic shaping via port mirroring is untargeted by its very nature. Because a router is a device with very limited capability, it is usually impossible to instruct the router to “port mirror” only a specific email or chat log toward a collection point.79 Instead, port mirroring is more likely to redirect traffic to or from an entire website, company, or ISP. In fact, the same NSA employee that created Figure 3 also describes using traffic shaping to redirect the communications of the entire country of Yemen toward an NSA collection point.80

Can Routers Lawfully Be Hacked to Shape Traffic on U.S. Soil?

While it is technically possible to redirect U.S. Internet traffic to foreign territory by hacking into routers, is it legal? What laws would govern this? In general, the legal framework surrounding hacking by intelligence agencies is murky, mostly because of classification, but also because FISA and EO 12333 were written three decades ago, before hacking became an essential part of surveillance operations.

Does FISA regulate hacking into a U.S. router and instructing it to perform traffic shaping by “port mirroring” traffic? If such an operation were regulated by FISA, then it would be subjected to the scrutiny of the FISA Court. As mentioned earlier, FISA is intended to be the “exclusive means” by which agencies were authorized to perform “electronic surveillance.” “Electronic surveillance” is a legal term that is defined the FISA statute; in fact, despite several amendments, FISA’s definition of “electronic surveillance” remains largely unchanged from its original 1978 version. The FISA definition of “electronic surveillance” has two clauses that could be potentially cover hacking into a U.S. router and instructing it to perform traffic shaping via port-mirroring.

One clause in the FISA statute defines “electronic surveillance” to be

the installation or use of an electronic, mechanical, or other surveillance device in the United States for monitoring to acquire information, other than from a wire or radio communication, under circumstances in which a person has a reasonable expectation of privacy and a warrant would be required for law enforcement purposes.81

In other words, this clause covers the installation of a device in the United States for surveillance. Hacking a U.S. router could certainly be considered the installation of a device. However, a router is a “wireline” device, and this clause does not cover devices that acquire information from a “wire.”82 As such, this clause is not relevant to the discussion.

Another clause in the FISA statute defines “electronic surveillance” as

the acquisition by an electronic, mechanical, or other surveillance device of the contents of any wire communication to or from a person in the United States, without the consent of any party thereto, if such acquisition occurs in the United States, but does not include the acquisition of those communications of computer trespassers that would be permissible under section 2511(2)(i) of title 18, United States Code.83

This clause covers the “acquisition” of communications inside the United States. However, one could argue that communications are not “acquired” when a U.S. router is hacked and instructed to perform port mirroring. The hacked router is merely instructed to copy traffic and pass it along, but not to read, store, or analyze it. Therefore, “acquisition” occurs at the tapped communication cable (abroad) rather than at the hacked router (inside the United States). As such, this clause is also not relevant.84

These definitions suggest that hacking into domestic routers and using them for traffic shaping does not constitute “electronic surveillance” under FISA. But there are two more issues to consider before deciding that these activities do not fall under FISA.

First, FISA’s exclusivity clause states that FISA’s “procedures . . . shall be exclusive means by which electronic surveillance . . . may be conducted.”85 Reiterating, “electronic surveillance” is a legal term that is narrowly defined by the FISA statute. Thus, one could argue that FISA forbids any traffic shaping program whose sole purpose is to circumvent the intentions of Congress when defining “electronic surveillance” in the FISA statute. That said, there is a simple way around this issue. If one could construct a different operational purpose for a traffic shaping program, then one would be on more solid ground. For instance, traffic shaping could be used “target” foreign communications,86 or to run more traffic past a collection point that has special technical capabilities, and so on.

If FISA does not cover hacking into a U.S. router and instructing it to perform traffic shaping, then one must consider whether it is covered by the Constitution. Does hacking into router on U.S. soil constitute a “search” or “seizure” under the Fourth Amendment? There are strong arguments that the answers to these questions would be yes,87 but the courts have yet to conclusively address them.88

However, even if this traffic-shaping technique constitutes a Fourth Amendment “search” or “seizure,” a warrant still may not be required. For instance, it may fall under a national security exception to the Fourth Amendment’s warrant requirement.89 One might also consider the third-party doctrine, which holds that when users disclose information (such as Internet traffic) to a third party (such as Internet service providers), they have “no reasonable expectation of privacy,”90 and thus no warrant is required to search it. However, it is not clear how the third-party doctrine might apply in this setting.91 So, while it may seem like a warrant should be required when hacking into a router and instructing it to perform port-mirroring, this warrant requirement may also be obviated by national-security or third-party-doctrine exceptions.

Settling these complex legal questions is beyond the scope of this report, however. The main point is that a warrant might not be required for this traffic shaping technique. What would the intelligence community’s lawyers do if they were asked to authorize a traffic-shaping program that redirects American traffic from U.S. territory to abroad? We don’t know. However, there is a risk that they could conclude it falls exclusively within the purview of EO 12333. In this case, the traffic-shaping program would never be vetted by the FISA Court, and instead would be regulated entirely by a classified process that is internal to the executive branch.

Traffic Shaping from Abroad

Even if the legal framework somehow forbids authorities from hacking into routers located on U.S. soil, other traffic shaping techniques can be performed entirely from abroad. One such technique takes advantage of a network protocol called the Border Gateway Protocol (BGP) to trick neighboring networks into redirecting their traffic.92

BGP is an Internet protocol that allows routers to decide how to send Internet traffic across the web of connections that makes up the modern Internet. Routers continuously send each other BGP messages, updating each other about routes they have available through the Internet. To perform traffic shaping with BGP, an entity manipulates the BGP messages sent by one router to its neighboring routers, tricking these routers into redirecting their Internet traffic via a new route.

There have been many documented cases of deliberate BGP manipulations.93

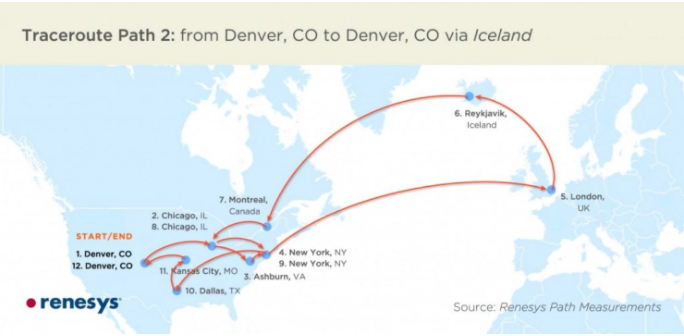

Figure 4 shows one incident that took place in July 2013, where an Icelandic router caused traffic sent between two U.S. endpoints to be redirected through Iceland.94 The Icelandic router sent a manipulated BGP message to a neighboring router in London, indicating that traffic destined for a group of American IP addresses should be routed to Iceland. The router in London was then convinced that traffic destined for these IP addresses should be routed to Iceland, rather than to the United States. The router in London then passed this manipulated BGP message to its neighbors, and so on, until the message eventually arrived at several routers in the United States.

Figure 4

The results of the BGP manipulation, shown in Figure 4, indicate just how convoluted Internet routing can become. Traffic originating in Denver (which was destined for one the American IP addresses that was the original subject of the BGP manipulation) is first sent through several American cities before going to London and then to Reykjavik. From there, the traffic travels to Montreal before it finally reaches one of the American IP addresses (in Denver) that is the original subject of the BGP manipulation.

It is still unclear who was behind this incident. There is no reason to believe that it involved the U.S intelligence community. Nevertheless, it is possible that routers in the Icelandic network were hacked by some unknown party, and then instructed to send manipulated BGP messages, thus causing the chain of events shown in Figure 4.

This traffic-shaping technique can be performed entirely from abroad. In this incident, the Icelandic router needed only to send a single BGP message to its neighbor in London to get the ball rolling.

One could also argue that the technique is untargeted, because the manipulated BGP messages specified that traffic destined for a group of American IP addresses should be routed through Iceland, without singling out anyone or anything in particular. An IP address identifies computing devices on the Internet, and a single IP address can be used by multiple devices or people.95 Moreover, BGP manipulations necessarily affect a group of IP addresses; it is generally not possible to perform a BGP manipulation that affects only a single IP address. Therefore, one could conclude can that BGP manipulation does not “intentionally target” a specific individual.96

As the Icelandic incident shows, BGP can be manipulated to shape traffic from inside the United States to a tapped communication cable located abroad. And since the BGP manipulation is just tricking routers into moving traffic around, and is not storing, reading, or analyzing said traffic, it is not “acquiring” it. Instead, “acquisition” happens at the tapped foreign communication cable. As such, the same legal argument used before—that this manipulation falls under EO 12333 rather than FISA—would also apply here. But now, there are even fewer constitutional questions, since the router performing the initial BGP manipulation belongs to a foreign company and is located on foreign soil.97

BGP is not the only Internet protocol that can be manipulated to perform traffic shaping. For instance, rather than manipulating BGP, one could instead manipulate a routing protocol called Open Shortest Path First (OSPF).98 Techniques for traffic shaping using OSPF have been described in a 2011 research paper by an NSA research scientist.99

Traffic Shaping by Consent

The intelligence community does not have to hack into routers or use other clandestine techniques to shape traffic—it could simply ask the corporations that own those routers to provide access, or shape the traffic themselves. A document leaked by Edward Snowden suggests that the NSA has done this through its FAIRVIEW program. (FAIRVIEW was revealed to be a code name for AT&T100). The document states:

FAIRVIEW—Corp partner since 1985 with access to int[ernational] cables, routers, and switches. The partner operates in the U.S., but has access to information that transits the nation and through its corporate relationships provide unique access to other telecoms and ISPs. Aggressively involved in shaping traffic to run signals of interest past our monitors.101

There is no evidence that the FAIRVIEW program is being used to shape traffic from inside the United States to foreign communications cables. But it is worth noting that, with the cooperation of corporations such as AT&T, traffic could easily be shaped to a collection point abroad without the need to hack into any routers, thus obviating many of the legal questions previously discussed.

Does All the Evidence Add Up to Traffic Shaping to Circumvent FISA?

This report has presented evidence that there is a possibility that the intelligence community can traffic shaping methods to reduce the privacy protections that U.S. persons have for their communications under FISA.

Modern networking protocols and technologies can be manipulated in order to shape Internet traffic from inside the United States toward tapped communications cables located abroad. It is possible that traffic shaping is regulated by EO 12333, and not by FISA,102 since the techniques shape traffic in bulk, in a way that does not “intentionally target” any specific individual or organization. Moreover, while FISA covers the “acquisition” of Internet traffic on U.S. territory, but the traffic shaping methods discussed merely move traffic around, but do not read, store, analyze, or otherwise “acquire” it. Instead, acquisition is performed on foreign soil, at the tapped communication cable. Finally, while the Fourth Amendment may require a warrant for hacking U.S. routers, the warrant requirement could be avoided by performing traffic shaping with the consent of corporations that own the routers (e.g. via the FAIRVIEW program), or by hacking foreign routers (and then using BGP manipulations).

As a final thought experiment, suppose that Congress decided not to reauthorize Section 702 of FISA, when it comes up for renewal at the end of this year. In this case, the NSA could no longer conduct warrantless surveillance on U.S. territory, and would instead have to revert to obtaining individualized FISA warrants103 for collection on targets on U.S. soil. The additional burden of oversight could create a new and powerful incentive for the NSA to employ traffic-shaping programs within U.S. borders. Internet traffic could be “shaped” from within U.S. territory (where warrantless surveillance would not be lawful) to foreign territory, where it could be collected without a warrant under EO 12333.

So, the question remains, can the NSA lawfully employ traffic-shaping techniques as a loophole that evades privacy protections for U.S. persons? The answer to this question is probably buried in classified documents. Nevertheless, a loophole exists, and eliminating it calls for a realignment of current U.S. surveillance laws and policies.

How to Provide Oversight When Conducting Surveillance of Americans

How can we eliminate the loophole that allows the surveillance of American Internet communications to evade authorization from the FISA Court, the legislative branch, and judicial branch of the U.S. government?

Technical Solutions Will Not Work

One might be tempted to eliminate these loopholes via technical solutions. For instance, traffic shaping could be made more difficult by designing routers that are “unhackable,” and Internet protocols could be made secure against traffic-shaping manipulations. Or the confidentiality of traffic could be protected just by encrypting everything.

While this approach sounds good in theory, in practice it is unlikely to work.

First, it is highly unlikely that we will ever have Internet infrastructure devices (e.g. routers) that cannot be hacked. Router software is complicated, and even the best attempt at an “unhackable” router is likely to contain bugs.104 Intelligence agencies have dedicated resources to finding and using these bugs to hack into routers.105 And even if we somehow manage to create bug-free router software, the intelligence community has been known to physically intercept routers as they ship in the mail, and tamper with their hardware.106

A key challenge is that the Internet is a global system, one that transcends organizational and national boundaries.

Second, it will take many years to develop and implement secure Internet protocols that prevent traffic shaping. A key challenge is that the Internet is a global system, one that transcends organizational and national boundaries. Deploying a secure Internet protocol requires cooperation from thousands of independent organizations in different nations. This is further complicated by the fact that many secure Internet protocols do not work well when they are used only by a small number of networks.107

Finally, while encryption can be used to hide the contents of Internet traffic, it does not hide metadata (that is, who is talking to whom, when they are talking, and for how long). Metadata is both incredibly revealing, and less protected by the law.108 Intelligence agencies have also dedicated resources toward compromising encryption.109 Moreover, EO 12333 allows the NSA to retain encrypted communications indefinitely.110 This is significant because the technology used to break encryption tends to improve over time—a message that was encrypted in the past could be decryptable in the future, as technology improves.111

This is not to say that technical solutions are unimportant. On the contrary, they are crucial, especially because they protect American’s traffic from snoopers, criminals, foreign intelligence services, and other entities that do not obey American laws. Nevertheless, technologies evolve at a rapid pace, so solving the problem using technology would be a continuous struggle.

It is much more sensible to realign the legal framework governing surveillance to encompass the technologies, capabilities, and practices of today and of the future.

A Legal Band-Aid Solution

A band-aid solution would be to ensure that it is illegal to deliberately reroute the traffic of any and all traffic belonging U.S. persons to foreign soil, where it can be “incidentally collected” under EO 12333. A good start would be to clarify the laws and policies surrounding traffic shaping and hacking under FISA and EO 12333. This could have been addressed, for example, in the investigation of EO 12333 by the Privacy and Civil Liberties Oversight Board, first announced in July 2014.112 However, the board’s report still has not been completed, and the board has lost four of its required five members.113

The 1978 FISA definition of “installing a device” could also be revised in a technology-neutral fashion, so that it would forbid any rerouting of U.S. persons’ communications, regardless of type of device. As this report has shown, many traffic shaping techniques cannot be executed in a “targeted” fashion, so the practice should be ruled out entirely, even if Americans are not “intentionally targeted.”

This band-aid solution could rule out the use of traffic shaping to evade FISA by deliberately redirecting American traffic to foreign territory. However, this is highly unsatisfying, because this band-aid solution does not offer any protections for American traffic that naturally flows abroad. Indeed, this is a crucial issue, since we already know of at least one program that has swept up communications (including those of Americans) that was naturally routed to data centers on foreign territory.114

Breaking Down Territorial Boundaries in the Law: Expand FISA

Therefore, the most natural solution would be to break down the legal barriers that separate spying abroad from spying on U.S. soil. The same legal framework should be applied to any and all Internet traffic, regardless of the geographical point of interception. This would disentangle Fourth Amendment protections for U.S. persons from the vagaries of Internet protocols and technologies. It would also offer robust legal protections as our communications technologies continue to evolve.

Indeed, as mentioned earlier, the intelligence community has already acknowledged the importance of this issue. J. Michael McConnell, the director of national intelligence, justified expanded surveillance authorities under FISA by arguing in 2007 that today’s “global communications grid makes geography an increasingly irrelevant factor.”115 His argument for boundary free-surveillance is simple: if agents are surveilling only foreigners, why does it matter that the data collection happens on U.S. territory? Indeed, this boundary-free approach is becoming the norm for surveilling a foreign target. In 2016, for example, the government expanded its hacking authorities to allow a single warrant to be used to hack into a device, even if the physical location of the device is unknown.116

But, likewise, this same logic should apply to expanding privacy protections for Americans, when their communications venture onto foreign soil. The argument remains simple: if agents end up collecting data on U.S. persons, why should those U.S. persons lose their judicially-protected right to privacy, just because the data was collected abroad? If geography is “an increasingly irrelevant factor,” it should not the basis for Americans to lose their constitutional rights.

One concrete improvement would be that surveillance that affects Americans could no longer evade the scrutiny of the FISA Court.

The most thorough, satisfying solution would simply be to expand FISA to cover the collection of all traffic, both at home and abroad. While FISA’s protections for U.S. persons are not perfect,117 expanding FISA would still improve the current state of affairs. One concrete improvement would be that surveillance that affects Americans could no longer evade the scrutiny of the FISA Court. Furthermore, violations of the law would come with criminal penalties, rather than just sanctions internal to the intelligence community.

To enact this solution, Congress could revise FISA’s definition of “electronic surveillance,” which determines the type of surveillance covered by FISA. The first goal of a revision would be to eliminate distinctions based on geographical location of collection. In other words, “electronic surveillance” should include data collected on both foreign and domestic territory. The second goal would be to formulate the definition in a technology-neutral fashion, so it cannot be outpaced by new technologies and new surveillance capabilities. (FISA’s current definition of “electronic surveillance” is far from technology-neutral; it distinguishes, for example, between “wired” communications and “radio” communications. Moreover, it seems to exclude traffic shaping technologies, which is not especially surprising, since Congress could hardly be expected in 1978 to anticipate today’s surveillance techniques.) A third goal would be to clarify and broaden the definition of “intentional targeting.” As we have seen, surveillance operations can still have significant impact on Americans even when they are not the “intentional targets” of the operation.118

The FISA Amendments Act is set to expire in December 2017. Congress should not miss this opportunity to consider revising FISA’s definition of “electronic surveillance” in order to eliminate loopholes that allow the executive branch to unilaterally conduct surveillance of American Internet traffic. Undertaking this revision is a crucial step toward ensuring that legislative and judiciary branches have a firm hand at protecting the privacy of American communications.

Acknowledgements

I thank Axel Arnbak for collaboration on the original research on which this article is based,119 and the Sloan Foundation for funding that work. Much of the new research appearing in this report would not have been possible without the assistance of Timothy Edgar. Doug Madory provided the data presented in Figure 1. Andrew Sellars provided valuable assistance with the legal analysis. This work also benefited from comments from Steven Bellovin, Saul Bermann, David Choffnes, Ethan Heilman, Brian Levine, Jonathan Mayer, George Porter, Jennifer Rexford and Marcy Wheeler and editing by Barton Gellman, Sam Adler-Bell, and Jason Renker. Any mistakes and omissions remain my responsibility.

Notes

- In his first public comment after the first Snowden stories appeared in the Guardian and Washington Post, President Obama said, “If the intelligence community then actually wants to listen to a phone call, they’ve got to go back to a federal judge, just like they would in a criminal investigation.” He said that the FISA Court ensures that NSA surveillance is “being carried out consistent with the Constitution and rule of law.” See: Barack Obama, “Statement by the President, Fairmont Hotel, San Jose, California,” June 7, 2013, at https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/the-press-office/2013/06/07/statement-president. A week later, on Charlie Rose, Obama said, “What I can say unequivocally is that if you are a U.S. person, the NSA cannot listen to your telephone calls, and the NSA cannot target your emails . . . unless they—and usually ‘they’ would be the FBI—go to a court and obtain a warrant and seek probable cause.” See: Buzzfeed Staff, “President Obama Defends NSA Spying,” Buzzfeed Politics, June 17, 2013, at http://bzfd.it/29YZSQ1.

- U.S. Code 50, §§ 1801 to 1813, https://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/50/chapter-36/subchapter-I.

- FISA was passed, in part, as a result of investigations of intelligence abuses during the 1970s by a committee chaired by Senator Frank Church of Idaho. In 1975, Church explained in a media interview, “The United States government has perfected a technological capability that enables us to monitor the messages that go through the air.” Church warned that this “capability at any time could be turned around on the American people, and no American would have any privacy left, such is the capability to monitor everything—telephone conversations, telegrams, it doesn’t matter. There would be no place to hide.” In the same interview, Church accepted that these NSA surveillance capabilities were “necessary and important to the United States as we look abroad at enemies or potential enemies.” See Timothy Edgar, “Go Big, Go Global: Subject NSA Overseas Programs to Judicial Review,” Hoover Institution, June 30, 2016, http://www.hoover.org/research/go-big-go-global-subject-nsa-s-overseas-programs-judicial-review.

- See, for instance, Sharon Goldberg, “Why Is It Taking So Long to Secure Internet Routing?” acmqueue 12, no. 8 (September 11, 2014): 56–63, http://queue.acm.org/detail.cfm?id=2668966.

- In engineering parlance, this is called “disaster recovery.” See for instance Bob Violino, “4 Tech Trends in IT Disaster Recovery: How DR Planning Is Affected by Social, Mobile, Virtualization and Cloud,” CSO online, July 19, 2012, http://www.csoonline.com/article/2131986/social-networking-security/4-tech-trends-in-it-disaster-recovery.html.

- For example, see Figure 1.

- For example, see Microsoft Corp. v. United States 829 F.3d 197 (2d Cir. 2016)(the “Microsoft Ireland Case”); “Microsoft Ireland Case: Can a US Warrant Compel a US Provider to Disclose Data Stored Abroad?” CDT, July 30, 2014, https://cdt.org/insight/microsoft-ireland-case-can-a-us-warrant-compel-a-us-provider-to-disclose-data-stored-abroad/.

- See more discussion under “How Can Surveillance under EO 12333 Impact Americans?”

- See, for example, Jennifer Daskal, “The Un-Territoriality of Data,” Yale Law Journal 125, no. 2 (November 2015): 326–98, http://www.yalelawjournal.org/article/the-un-territoriality-of-data; Timothy Edgar, “Go Big, Go Global: Subject NSA Overseas Programs to Judicial Review,” Hoover Institution, June 30, 2016, http://www.hoover.org/research/go-big-go-global-subject-nsa-s-overseas-programs-judicial-review; or Jennifer Granick, “Reining In Warrantless Wiretapping of Americans,” The Century Foundation, March 16, 2017, https://tcf.org/content/report/reining-warrantless-wiretapping-americans/.

- Traffic shaping the communications of the entire country of Yemen is described in “Network Shaping 101,” https://www.documentcloud.org/documents/2919677-Network-Shaping-101.html, slides created by an NSA hacker who was later interviewed in Peter Maass, “THE HUNTER: He Was a Hacker for the NSA and He Was Willing to Talk. I Was Willing to Listen,” The Intercept, June 28, 2016, https://theintercept.com/2016/06/28/he-was-a-hacker-for-the-nsa-and-he-was-willing-to-talk-i-was-willing-to-listen/. This NSA hacker is the same person who also drew Figure 3 of this report, which will be discussed in detail later.

- Programs under EO 12333 are not authorized by Congress, and thus not subject to statutory limitations. That said, Congress is engaged in appropriating the funds that pay for EO 12333 surveillance programs, and thus engages in oversight to ensure that these funds are properly spent. But it is unclear to what extent this oversight is concerned with Americans’ privacy rights. In August 2013, for instance, the chair of the Senate Select Committee on Intelligence, Diane Feinstein, stated: “I don’t think privacy protections are built into [EO 12333]. It’s an executive policy. The executive controls intelligence in the country.” She also said that “The other programs do not (have the same oversight as FISA). And that’s what we need to take a look at,” adding that her committee has not been able to “sufficiently” oversee the programs run under the executive order. “Twelve-triple-three programs are under the executive branch entirely.” Ali Watkins, “Most of NSA’s data collection authorized by order Ronald Reagan issued,” McClatchy, November 21, 2013, http://www.mcclatchydc.com/news/nation-world/national/national-security/article24759289.html. Feinstein has also stated, “By law, the Intelligence Committee receives roughly a dozen reports every year on FISA activities, which include information about compliance issues. Some of these reports provide independent analysis by the offices of the inspectors general in the intelligence community. The committee does not receive the same number of official reports on other NSA surveillance activities directed abroad that are conducted pursuant to legal authorities outside of FISA (specifically Executive Order 12333), but I intend to add to the committee’s focus on those activities.” From “Feinstein Statement on NSA Compliance,” August 16, 2013, https://www.feinstein.senate.gov/public/index.cfm/2013/8/feinstein-statement-on-nsa-compliance.

- 18 U.S. Code § 2516, “Authorization for interception of wire, oral, or electronic communications.”

- U.S. Code 50, §§ 1801 to 1813, https://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/50/chapter-36/subchapter-I. FISA covers “domestic” surveillance of the communications sent between Americans, when those communications are collected on U.S. soil. FISA also covers collection on U.S. soil when one “communicant” is a U.S. person and another “communicant” is a foreigner. (This might be called “transnational” surveillance, rather than “domestic” surveillance.) But, if that same transnational communication is collected abroad (without “intentionally targeting a U.S. person”), it is covered by EO 12333, not FISA. It’s not completely clear whether FISA applies if the foreign end of the transnational communication is a foreign computer rather than a foreign person, and this report does not answer this question. Moreover, FISA’s purview for stored communications and radio communications is different from its purview for wired communications. This report sidesteps all these issues. For analysis of the latter issue, see the Annex of Amos Toh, Faiza Patel, and Elizabeth Goitein, “Overseas Surveillance in an Interconnected World,” Brennan Center for Justice, March 16, 2016, https://www.brennancenter.org/sites/default/files/publications/Overseas_Surveillance_in_an_Interconnected_World.pdf which has a detailed breakdown of what falls under FISA and what falls under EO 12333.

- Executive Order 12333 (1981)—As amended by Executive Orders 13284 (2003), 13355 (2004), and 13470 (2008), https://www.intelligence.senate.gov/laws/executive-order-12333-1981-amended-executive-orders-13284-2003-13355-2004-and-13470-2008.

- The process of deciding what falls under FISA and what falls under EO 12333 is extremely complex, and often obscured by classification. We do not even attempt to describe it here. To get an idea of the complexity of this issue, see again the Annex in Toh, Patel, and Goitein, “Overseas Surveillance in an Interconnected World,” which has a detailed breakdown of what falls under FISA and what falls under EO 12333.

- See discussion in note 11.

- There are several reasons why the EO 12333 framework is more permissive than the FISA framework. FISA programs are authorized by all three branches of government, while EO 12333 programs are solely under the executive. Programs under FISA can be subject to review by the FISA court, while EO 12333 programs are not reviewed by any court. FISA can be challenged in court, because notice is required when evidence is obtained from FISA surveillance. Meanwhile, no statute requires notice of EO 12333 surveillance. See Toh, Patel, and Goitein, “Overseas Surveillance in an Interconnected World”; see also Zachary D. Clopton, “Territoriality, Technology, and National Security,” University of Chicago Law Review 83, no. 1 (2015): 45–63, http://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/uclrev/vol83/iss1/3. Moreover, FISA requires a warrant when “intentionally targeting a U.S. person.” By contrast, under EO 12333, “US Person information may be collected, retained, or disseminated if consistent with the element’s mission; consistent with an authorized category of collection; and permissible under the element’s AG-approved guidelines.” This quote is from a training module, where “element” refers to an element of the intelligence community, such as the CIA, the NSA, the FBI, and so on. See “Use and Protection of US Person Information in US Intelligence Community Activities,” Office of the Director of National Intelligence, https://www.aclu.org/foia-document/use-and-protection-us-person-information-us-intelligence-community-activities. The NSA’s procedures under EO 12333 also contain four full pages of exceptions that allow U.S. persons to be intentionally targeted without a warrant. One exception allows the U.S. attorney general to approve targeting of a U.S. person subject to the constraint that it collects “significant foreign intelligence”—broadly defined to include information “relating to the capabilities, intentions and activities” of “foreign persons.” See Toh, Patel, and Goitein, “Overseas Surveillance in an Interconnected World”; see also Axel Arnbak and Sharon Goldberg, “Loopholes for Circumventing the Constitution: Unrestrained Bulk Surveillance on Americans by Collecting Network Traffic Abroad,” Michigan Telecommunications and Technology Law Review 21, no. 2 (2015): 317–361, http://repository.law.umich.edu/mttlr/vol21/iss2/3. Finally, dissemination of information collected under EO 12333 is also less restrained; see again Toh, Patel, and Goitein, “Overseas Surveillance in an Interconnected World.”

- Actually, it is debatable whether a FISA Title I court order is “a warrant in the constitutional sense.” What matters for this report, however, is that these court orders are issued by an independent court staffed by federal district judges appointed by the chief justice of the United States, rather than by processes internal to the intelligence community and the executive branch. For more discussion on whether FISA Title I court orders is “a warrant in the constitutional sense,” see Sealed Case 3io F.3d http://law.justia.com/cases/federal/appellate-courts/F3/310/717/495663/ or “Constitutional Law. Fourth Amendment. Separation of Powers. Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court of Review Holds That Prosecutors May Spy on American Agents of Foreign Powers without a Warrant. In re Sealed Case, 310 F.3d 717 (Foreign Int. Surv. Ct. Rev. 2002),” Harvard Law Review 116, no. 7 (May, 2003): 2246–53, https://www.law.upenn.edu/live/files/2477-fisc–harvard-law-reviewpdf.

- Eric Lichtblau, “Senate Approves Bill to Broaden Wiretap Powers,” New York Times, July 10, 2008, www.nytimes.com/2008/07/10/washington/10fisa.html?_r=0. Actually, this was first passed as part of the Protect America Act in 2007 and then the FISA Amendment Act (FAA) added Section 702 in 2008. For a detailed analysis of Section 702, see Laura K. Donohue, “Section 702 and the Collection of International Telephone and Internet Content,” Harvard Journal of Law and Public Policy 38 (2015): 117–265, https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/34b3/149133e364b45e8745df0f30fa1113af7bff.pdf.

- This statement was made in 2007 before the Senate Committee on the Judiciary. For a full transcript of McConnell’s remarks, see Statement for the Record of J. Michael McConnell, Director of National Intelligence, before the Judiciary Committee United States Senate, September 25, 2007, http://fas.org/irp/congress/2007_hr/092507mcconnell.pdf.

- Evidence of this is provided later in this report. See, for instance, the discussion in note 67.

- “The right of the people to be secure in their persons, houses, papers, and effects, against unreasonable searches and seizures, shall not be violated, and no Warrants shall issue, but upon probable cause, supported by Oath or affirmation, and particularly describing the place to be searched, and the persons or things to be seized.” U.S. Constitution, Amendment IV.

- In the United States v. Verdugo-Urquidez, the Supreme Court held that Fourth Amendment protections do not apply to a nonresident alien in a foreign country. See United States v. Verdugo-Urquidez, 494 U.S. 259 (1990), http://caselaw.findlaw.com/us-supreme-court/494/259.html. For more discussion on the relationship between territoriality and the government’s authority to search/seize data and communications, see, for example, Jennifer Daskal, “The Un-Territoriality of Data,” Yale Law Journal 125, no. 2 (November 2015): 326–98, http://www.yalelawjournal.org/article/the-un-territoriality-of-data; Orin S. Kerr, “The Fourth Amendment and New Technologies: Constitutional Myths and the Case for Caution,” Michigan Law Review 102 (2004): 801–88, https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=421560, and Clopton, “Territoriality, Technology, and National Security,” University of Chicago Law Review 83, no. 1 (2015): 45–63, http://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/uclrev/vol83/iss1/3.

- Briefly, there also other legal authorities regulating Internet surveillance for national-security purposes. The USA FREEDOM ACT was passed by Congress in 2015, both as a reaction to revelations about NSA surveillance made by Edward Snowden, and in order to restore and modify provisions of FISA and the Patriot Act. The USA Freedom Act, H.R. 2048, June 2, 2015, https://www.congress.gov/bill/114th-congress/house-bill/2048/text. Generally speaking, it governs surveillance of Americans on U.S. soil. Also, Presidential Policy Directive 28 (PPD-28) is a directive issued by the Obama administration in January 2014, and establishes rules on how foreigners’ data should be handled. “Presidential Policy Directive—Signals Intelligence Activities,” The White House, January 14, 2014, https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/the-press-office/2014/01/17/presidential-policy-directive-signals-intelligence-activities. Also see Toh, Patel, and Goitein, “Overseas Surveillance in an Interconnected World,” for an analysis of the surveillance of foreigners under EO 12333.

- See, for instance, J. S. Brand. “Eavesdropping on our founding fathers: How a return to the republic’s core democratic values can help us resolve the surveillance crisis,” Harvard National Security Journal 6, no. 1 (2015), http://harvardnsj.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/Brand.pdf.

- Statement of Senator Edward Kennedy in “Warrantless Wiretapping: Hearings before the Subcommittee on Administrative Practice and Procedure of the Committee on the Judiciary,” United States Senate, 92d Cong., 2d sess., June 29, 1972, https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=uiug.30112106680801. See also ibid.

- See discussion in note 18.

- U.S. Code 50, § 1804(a)(6)(b).

- For more discussion on the FISA Court, see for example, Edgar, “Go Big, Go Global: Subject NSA Overseas Programs to Judicial Review”; Elizabeth Goitein and Faiza Patel, “What Went Wrong with the FISA Court,” Brennan Center for Justice, 2015, http://litigation.utahbar.org/assets/materials/2015FedSymposium/3c_What_Went_%20Wrong_With_The_FISA_Court.pdf; or Brand, “Eavesdropping on our founding fathers: How a return to the republic’s core democratic values can help us resolve the surveillance crisis.”

- See discussion in note 23.

- See discussion in note 18.

- The court is approving “categories” of targets, rather than individual targets. The Privacy and Civil Liberties Oversight Board has stated: “Under Section 702, the Attorney General and Director of National Intelligence make annual certifications authorizing this targeting to acquire foreign intelligence information, without specifying to the FISA court the particular non-U.S. persons who will be targeted. There is no requirement that the government demonstrate probable cause to believe that an individual targeted is an agent of a foreign power, as is generally required in the ‘traditional’ FISA process under Title I of the statute. Instead, the Section 702 certifications identify categories of information to be collected, which must meet the statutory definition of foreign intelligence information. The certifications that have been authorized include information concerning international terrorism and other topics, such as the acquisition of weapons of mass destruction.” “Report on the Surveillance Program Operated Pursuant to Section 702 of the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act,” Privacy and Civil Liberties Oversight Board, July 2, 2014, https://www.pclob.gov/library/702-Report.pdf. Also, an NSA fact sheet on Section 702 of FISA states: “Under this authority, the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court annually reviews ‘certifications’ jointly submitted by the U.S. Attorney General and Director of National Intelligence. These certifications define the categories of foreign actors that may be appropriately targeted, and by law, must include specific targeting and minimization procedures adopted by the Attorney General in consultation with the Director of National Intelligence and approved by the Court as consistent with the law and 4th Amendment to the Constitution.” “Section 702,” undated factsheet, National Security Administration,

http://www.documentcloud.org/documents/741586-nsa-fact-sheet-on-section-702-of-fisa-and.html. For more analysis on Section 702, see, for instance, Donohue, “Section 702 and the Collection of International Telephone and Internet Content,” 117. - See Statement for the Record of J. Michael McConnell, Director of National Intelligence, before the Judiciary Committee United States Senate, September 25, 2007, http://fas.org/irp/congress/2007_hr/092507mcconnell.pdf.

- Eric Lichtblau, “Senate Approves Bill to Broaden Wiretap Powers,” New York Times, July 10, 2008, http://www.nytimes.com/2008/07/10/washington/10fisa.html?_r=0.

- FISA’s definition of “electronic surveillance” is in U.S. Code 50, § 1801(f), https://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/50/1801.

- See again Toh, Patel, and Goitein, “Overseas Surveillance in an Interconnected World.”

- “NSA conducts the majority of its SIGINT activities solely pursuant to the authority provided by EO 12333,” From the NSA’s “Legal Fact Sheet: Executive Order 12333,” June 2013, https://www.aclu.org/foia-document/legal-fact-sheet-executive-order-12333. See also Ashley Gorski, “New NSA Documents Shine More Light into Black Box of Executive Order 12333,” ACLU National Security Project, October 30, 2014, https://www.aclu.org/blog/new-nsa-documents-shine-more-light-black-box-executive-order-12333.

- See discussion in note 17.

- Edgar, “Go Big, Go Global: Subject NSA Overseas Programs to Judicial Review.”

- More discussion can be found in Toh, Patel, and Goitein, “Overseas Surveillance in an Interconnected World.”

- More discussion can be found in ibid.

- This issue is discussed in detail later in this report, specifically in the discussion on algorithmic analysis of metadata under EO 12333.

- More discussion can be found in Toh, Patel, and Goitein, “Overseas Surveillance in an Interconnected World.”

- For example, the XKEYSCORE system that Edward Snowden called a “search engine”; see “Snowden-Interview: Transcript,” NDR.de, January 26, 2014, http://www.ndr.de/nachrichten/netzwelt/snowden277_page-3.html. For more on XKEYSCORE, see Morgan Marquis-Boire, Glenn Greenwald, and Micah Lee, “XKEYSCORE: NSA’s Google for the World’s Private Communications,” The Intercept, July 1 2015, https://theintercept.com/2015/07/01/nsas-google-worlds-private-communications/, or Glenn Greenwald, “XKeyscore: NSA tool collects ‘nearly everything a user does on the internet,’” The Guardian, July 31, 2013, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2013/jul/31/nsa-top-secret-program-online-data.

- For NSA “selectors” that implicate a specific individual, see the leaked NSA slide, “Selector Types,” The Intercept, March 12, 2014, https://theintercept.com/document/2014/03/12/selector-types/.

- These examples are from Toh, Patel, and Goitein, “Overseas Surveillance in an Interconnected World.”

- See the revealed NSA training slide published in “What’s a ‘violation’?” Washington Post, http://apps.washingtonpost.com/g/page/national/whats-a-violation/391/.