This piece has been updated with new information.

Last Wednesday, the New Syrian Army—America’s best, maybe only, hope to challenge the self-proclaimed Islamic State in its east Syrian stronghold—launched a daring attack on the heart of Islamic State territory.

By Thursday, it had gone wrong.

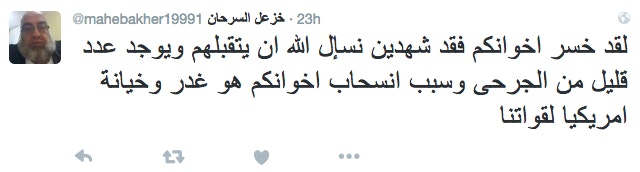

Islamic State had been waiting, and the New Syrian Army only barely avoided being annihilated by circling jihadists. On Twitter and in an interview with me, the group’s commander, Khaz’al al-Sarhan, railed against his American backers and speculated that his own group may have been infiltrated by Islamic State.

Translation: “Your brothers [only] lost two martyrs – we ask God to accept them – and there are a few wounded. The reason your brothers withdrew was America’s treachery and betrayal of our forces.”

For the United States, it was just the latest in a series of mostly unsuccessful attempts to field a Syrian Arab proxy force against Islamic State. Even after the conspicuous failure of other U.S.-trained units, the United States seems no closer to figuring out how to get Syria’s rebels to fight America’s war.

Near-Disaster in Albukamal

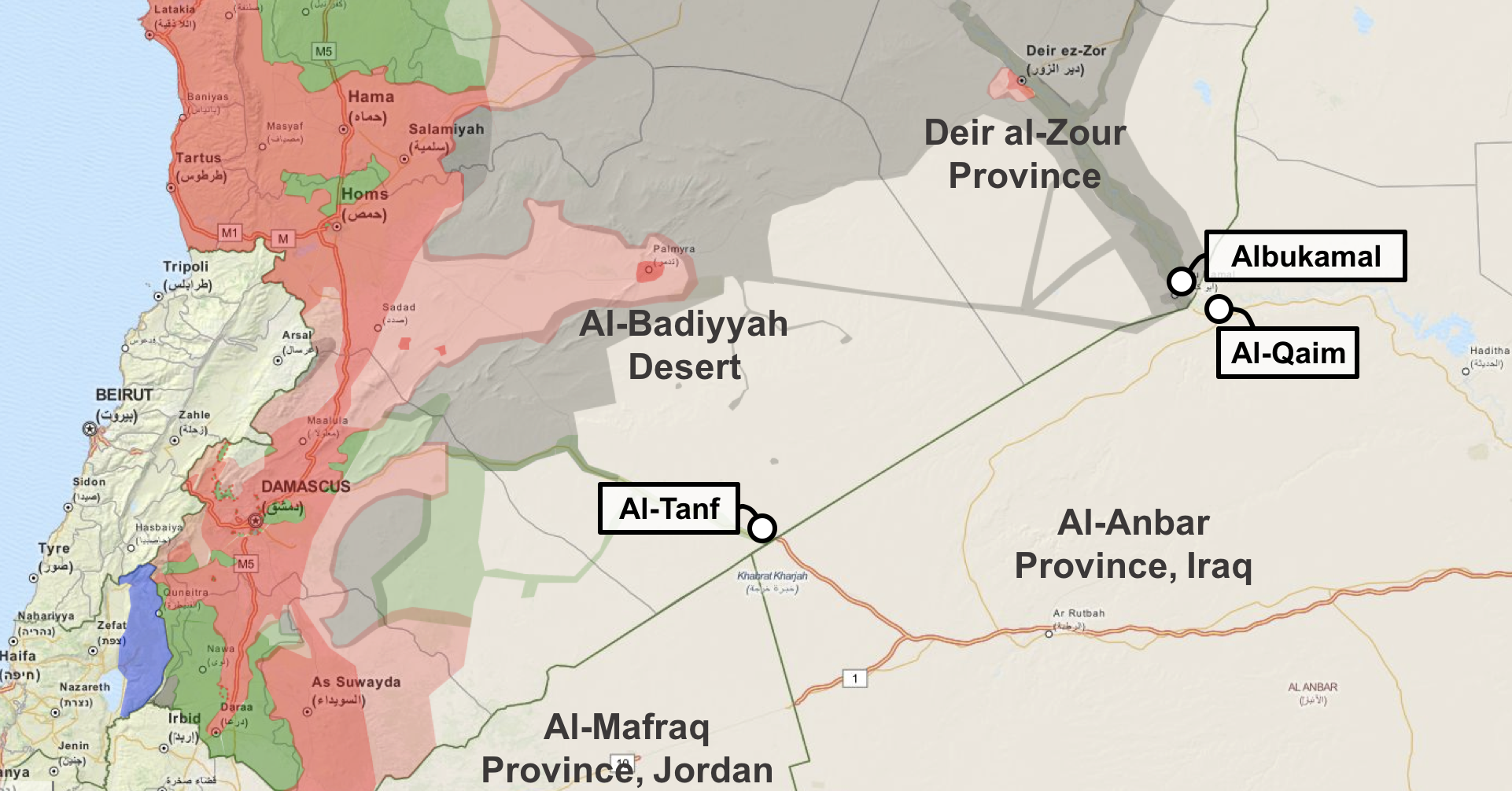

The June 29 offensive was supposed to showcase the New Syrian Army (Jeish Suriya al-Jadid, or the NSA), America’s latest partner in Syria. It is one of several Syrian factions fighting Islamic State (IS, also known by an earlier acronym, ISIS) that have been trained and equipped overtly by the Pentagon and backed by the international coalition America has assembled against Islamic State. The NSA was attacking Albukamal, a key strategic border town in Syria’s eastern Deir al-Zour province that serves as the desert link between Islamic State in Syria and Iraq.

The NSA advanced from its base in the central Syrian desert to Albukamal’s outskirts, where it seized an airfield and set up a base in a local school. But the offensive seems to have been dramatically undermanned. The NSA may have top-of-the-line U.S.-supplied hardware and U.S. air support, but according to sources within the group, it has only about 150 fighters. The day after it arrived in Albukamal with such fanfare, the NSA had been encircled by Islamic State forces.

“Thank God they didn’t use a car bomb on our encircled men,” Khaz’al al-Sarhan told me over social media. “We would have lost a lot.”

The NSA could have been wiped out. “Thank God they didn’t use a car bomb on our encircled men,” Khaz’al al-Sarhan told me over social media. “We would have lost a lot.”

It was only thanks to help from American bombers that the NSA was able to narrowly escape and retreat west to its base. The heavily publicized rebel offensive had completely collapsed a day after it begun. Somewhat miraculously, it had suffered only a handful of casualties—Sarhan told me two had died, although other accounts put the number higher. But the defeat was a blow to hopes that the NSA—or anyone, really—can free the residents of Albukamal and Deir al-Zour from Islamic State.

Arab Partners against Islamic State

The failure of the Albukamal offensive was yet another example of how the United States has struggled to navigate the politics of Syria’s civil war and transform Syria’s local conflict into the anti-jihadist proxy war Washington would prefer to fight.

America’s coalition has had some success fighting Islamic State in northeast Syria—but so far, its only reliable partners have been Kurdish-led forces deeply unpopular with the mostly Arab Syrian opposition. To effectively capture and hold Arab areas held by Islamic State, America needs Arab partners with local roots and credibility. But U.S. attempts to recruit and back these sorts of Syrian Arab forces have repeatedly stumbled, as the United States has failed to account for the factional and personal politics of Syria’s rebels, as well as the basic disconnect between the U.S. priority of combating Islamic State and most rebels’ aim of toppling the regime of Bashar al-Assad.

The NSA seemed to be the United States’ best chance at an ally that, at least for Washington, made sense. The NSA announced itself late last year, vowing to liberate Deir al-Zour from Islamic State. Sarhan and Lt. Col. Muhannad al-Talla’, former head of the rebel Military Council in Deir al-Zour, commanded the NSA. Rebels from Deir al-Zour manned the NSA, and Albukamal residents from Sarhan’s Allahu Akbar Brigades (Kataib Allahu Akbar) formed the group’s core.

Here was a group of fighters who had to fight Islamic State to free their homes and families. But the symbolism of the group seemed even bigger—in contrast with its essentially regional character, the NSA’s name and branding appeared to promise an ambitious and unifying national project.

The NSA was formed under the aegis of the Authenticity and Development Front (Jabhat al-Asalah wal-Tanmiyyah), a coalition of rebel factions that could lend some revolutionary legitimacy to what might otherwise seem like a creation of the Pentagon. Sarhan’s Allahu Akbar Brigades had previously been part of the Authenticity and Development Front. The Authenticity and Development Front had a long track record of fighting the Assad regime across the country, but it had been most deeply rooted in the east.

After initially training in Jordan, the NSA captured the southern desert outpost of al-Tanf from the Islamic State in March and established its base there. In the barren desert south, the NSA and its backers in the American-led coalition against Islamic State didn’t need to worry about the unwieldy mix of factions far away in Syria’s rebel north, including Syrian al-Qaeda affiliate Jabhat al-Nusrah. Months earlier, Jabhat al-Nusrah had attacked the first Pentagon-trained faction to re-enter the country in northern Aleppo, killing and abducting dozens of the U.S.-trained fighters. A second U.S.-backed unit in the north surrendered much of its equipment to Jabhat al-Nusrah within days of re-entering Syria.

What Really Happened in Albukamal?

The Albukamal offensive came after a bruising several months for the NSA, including a May Islamic State car bombing against the NSA’s base that killed eleven NSA members and wounded many more, according to a NSA media official who spoke to me over social media. In June, Russian planes bombed the al-Tanf base, killing two NSA members, apparently to make a political point to the United States.

Yet instead of laying low, the NSA went on the offensive. Attacking Albukamal would have been ambitious, even in greater numbers. Attacking with only 150 men seems to have been spectacularly ill-advised.

Ziad Awad, editor of the Deir al-Zour-focused news site Ain al-Madina, followed the battle from his home in the Turkish border town of Akçakale.

Awad, himself a native of Deir al-Zour, said it was clear to him “from the start” that Islamic State had made a tactical retreat. The NSA wasn’t making a lightning advance across the desert, Awad observed; it was just that Islamic State had deliberately fallen back to an easier-to-defend town. The NSA had advanced across exposed desert, Awad said, and “in these sort of open spaces, ISIS avoids direct confrontation, for fear of aerial bombing.”

NSA commander Khaz’al al-Sarhan said he and his men had been outfoxed.

“They knew all the details of when we’d come,” Sarhan told me over social media. “They baited us into an ambush, and we fell in the trap.”

After the NSA’s withdrawal, Islamic State-linked media outlet A’maq News Agency released footage of Islamic State members beheading several NSA fighters and parading through the streets of Albukamal with captured vehicles and weaponry.

Still, U.S. officials and rebels involved with the NSA defended the raid deep into Islamic State territory.

Speaking to me over Skype from Kuwait, Khaled al-Hammad, secretary-general of the Authenticity and Development Front, said he believed the Albukamal offensive had achieved tangible and symbolic gains.

“Getting out of this place safely, killing lots of ISIS members, destroying a number of their vehicles and bases—I think that’s a good accomplishment,” Hammad told me. “It gives hope for liberation and for shattering this idol [Islamic State], which has been given more than its due.”

“Getting out of this place safely, killing lots of ISIS members, destroying a number of their vehicles and bases—I think that’s a good accomplishment,” Hammad told me. “It gives hope for liberation and for shattering this idol [Islamic State], which has been given more than its due.”

The spokesman for America’s coalition against Islamic State, U.S. Army Col. Christopher Garver, acknowledged to me over e-mail that the NSA had not liberated Albukamal. Yet he said that “at the tactical level, the NSA troops fought with bravery and demonstrated their ability to cross large swaths of desert terrain quickly, move through ISIS territory undetected, conduct attacks to seize a foothold in a city, and break contact from a determined enemy.” He said the attack had disrupted Islamic State control around Albukamal and placed new pressure on the group.

Still, others have asked how this critical NSA offensive could have been so ill conceived.

Awad called the decision to launch the attack “remarkable.” According to Awad, “A lot of fighters today, or the revolutionaries from Deir al-Zour, are seriously asking, ‘How? Who made this battle plan?’”

What Went Wrong

According to Sarhan, the offensive involved a number of moving parts, almost none of which functioned as intended.

For one, the plan had hinged on a parallel offensive by Iraqi tribesmen on Albukamal’s Iraqi twin city, al-Qaim—an offensive that never came. The NSA’s numbers were too small to stand up to Islamic State alone, Sarhan said.

“Sleeper cells” inside Albukamal also didn’t materialize. They may have been intimidated by an Islamic State video released the day of the offensive in which the Islamic State executed five Albukamal residents. In the video, the five confessed to sending bombing coordinates to the NSA and disseminating NSA propaganda flyers.

And in a now-deleted series of tweets Friday, Sarhan blamed the Americans for their “treachery and betrayal.” He told me, “They left our men without [air] cover, not like they promised.” The Americans failed to bomb Islamic State units en route to reinforce Albukamal, Sarhan said. “They said it was because of weakness in their intelligence,” he continued. “They didn’t have specific coordinates, and the ISIS members moved fast.”

Col. Garver said coalition aircraft had conducted fifteen airstrikes against Islamic State tactical units and static targets in support of the NSA offensive between June 28 and 29. The Authenticity and Development Front’s Hammad denied that the Americans had failed the NSA.

Sarhan also said Islamic State’s commanders were experienced and effective—and they may have had inside knowledge.

“They’ve probably infiltrated us,” Sarhan said. When asked how, he said, “I don’t know. Maybe they sent some people from the region who joined our forces and we haven’t discovered it yet.”

“They’ve probably infiltrated us,” Sarhan said. When asked how, he said, “I don’t know. Maybe they sent some people from the region who joined our forces and we haven’t discovered it yet.”

As for the operation’s odd timing, Sarhan said it was launched “because of a Jordanian demand, because ISIS targeted their border and the al-Ruqban base,” referring to a recent Islamic State car bombing that killed a number of Jordanian border guards. Sarhan continued, “So they asked us to move, to get retribution. We agreed and got lots of equipment, most of which fell into these ISIS members’ hands.”

Sarhan also said that a Jordanian special forces officer, whom he declined to name, helped lead the Albukamal offensive.

A representative for the Jordanian government did not respond to requests for comment. Col. Garver denied that any coalition advisors participated in ground combat operations.

Hammad denied both that Jordan had urged the offensive and that a Jordanian officer had helped command the NSA’s forces. He also told me any pressure had been American, not Jordanian. “The preparation was rushed, thanks to the American side,” Hammad said. “There should have been more [fighters] and more preparation, but things were hurried.”

When asked if the United States had pushed the offensive, Col. Garver declined to comment.

Whatever the truth, Sarhan’s account raises troubling questions about America’s strategy against Islamic State, which relies on tight coordination with allies such as Jordan and Iraq, and committed support from Syrian and Iraqi local militias.

A Hard Ceiling on Recruitment

Hammad said the operation should have been put off until the NSA could muster at least 1,000 fighters.

But it isn’t clear the NSA recruitment could ever reach such high numbers. The NSA’s force strength is up from the several dozen fighters it fielded late last year, but more recruitment has been hampered by the same problems—factionalism, personality disputes, and mistrust of the United States—that have hobbled U.S. efforts against Islamic State elsewhere.

The NSA should, in theory, be more functional than the U.S.’s other “train-and-equip” forces. Enlistment in the Pentagon program disappointed expectations in part because trained forces were required to focus exclusively on fighting Islamic State instead of the Assad regime. The Assad regime has almost no foothold in Deir al-Zour, however. It is Islamic State that stands between these fighters and their homes.

And yet the NSA has failed to recruit more of the Deir al-Zour rebels whom Islamic State drove out of the province in summer 2014 and scattered across Syria and Turkey.

In part, this is because—shiny new branding to the contrary—the NSA is made of the same rebels who have been fighting for almost five years, and it has inherited their personal and factional baggage.

Many Deir al-Zour commanders refuse to serve under Talla’ and Sarhan, whom they accuse of being weak or crooked. Sarhan confirmed to me that he had standing disputes with some commanders. Talla’ is blamed by some for the failure of the Military Council to provide Deir al-Zour rebels with meaningful support. Some also associate him with the decision of rebels in his hometown of Muhassan not to resist Islamic State when it took Deir al-Zour.

Yet “Saleh,” an activist from Albukamal who spoke to me from Turkey and asked to use a pseudonym, said the issue was as much about egos as about objections to any one person.

“Deir al-Zour is a region of leaders—each one of them wants to be a leader,” Saleh told me over the phone. “Honestly! Even fighters in those brigades, they think they’re leaders. It’s a fight between warlords. Each of them wants to be the one.”

Tlass al-Salameh’s Eastern Lions Army (Jeish Usoud al-Sharqiyyeh) is one Deir al-Zour faction that has refused to join the NSA. The Eastern Lions, which periodically fight Islamic State alongside the NSA, are based in the mountains east of Damascus. They were also part of the Authenticity and Development Front until they split last December, and they separately receive backing from the U.S.-led Military Operations Center (MOC) in Amman, Jordan, a coordination cell that reportedly includes the CIA.

“Tlass al-Salameh is supported by the MOC. And the NSA is backed by the Pentagon,” said Ain al-Madina editor Awad. “That is, two military projects backed by one party [the United States], basically.” Awad called it “striking” that the United States couldn’t force two militias it backs to collaborate.

Deir al-Zour fighters are also reluctant to become too closely involved with America; they don’t trust U.S. efforts after five years of lukewarm, mercurial support for the Syrian opposition. “Lots of fighters don’t feel as if the American government is serious about these projects,” said Awad.

The Russian strike on the NSA’s base only raised further questions about the United States’ commitment. Talla’ and the NSA media official both told me the United States had earlier promised to protect the NSA from any attack, a promise that may have been impossible to keep.

And even among rebels from Deir al-Zour, few are comfortable focusing exclusively on Islamic State. “Most of the genuinely capable fighters, the ones really committed to fighting with ISIS, are, at base, revolutionaries. They took up arms against Bashar al-Assad,” said Awad.

“Deir al-Zour isn’t a state all on its own,” Awad told me. “Deir al-Zour is part of Syria.”

The Pentagon Sells the New Syrian Army

Some of these objections to the NSA—and thus obstacles to recruitment—stem from sloppy messaging and image management. The Authenticity and Development Front’s leadership would have avoided some amateur mistakes, group official Hammad said, but it had been sidelined by the United States and its coalition partners on nearly all decision-making related to the NSA. Instead, U.S. and other coalition officials dealt only with commanders Talla’ and Sarhan. A coalition media office had produced some of the NSA’s embarrassing media output.

“Some of the statements that came out, the flyers that were dropped—they made it out to be an American project,” Hammad told me. “It never took on a Syrian, Arab, patriotic character.”

Hammad has attempted personally to run interference. After a NSA introductory video in which Sarhan spoke in front of an upside-down revolutionary flag and made no reference to the Assad regime, for example, Hammad gave a battery of interviews in which he highlighted the role of the Authenticity and Development Front and the NSA’s revolutionary character and opposition to the regime.

The NSA now has two Twitter feeds apparently working at cross purposes: one in Arabic administered by the Authenticity and Development Front and another in Arabic and English administered by the U.S.-led coalition. On June 28, the Authenticity and Development Twitter feed directed followers to a set of official NSA social media feeds, including a channel on the messaging app Telegram. Days later, the coalition Twitter feed told a follower (in English), “We don’t have any Telegram channel, it’s for some supporters.”

https://twitter.com/NSyA_Official/status/748873754332262400

The coalition media effort has frequently seemed tone-deaf. On July 1, for example, it tweeted graphics of coalition jets on which the NSA’s logo had been superimposed on the jets’ bombs. Coalition bombing in Deir al-Zour continues to be controversial among residents because of the damage caused to civilian livelihoods and infrastructure, people from Deir al-Zour told me.

Speaking to me about an earlier instance in which the NSA associated itself with coalition bombing, Hammad asked me, “We don’t have planes, how do we take responsibility for coalition bombing?”

The spokesman for the coalition’s NSA media office did not respond to requests for comment.

“We won’t say we’ll work alone—we can’t,” said Hammad. But Hammad said this partnership had to be rebalanced, and that the coalition couldn’t assume control of every aspect of the project, including its media output.

“We need to say we’re a faction that belongs the Free Syrian Army and the Syrian Arab Republic, but we have friends who help us,” he told me. “That sort of discourse, not what the Pentagon says, which no one accepts.”

No One Waiting in the Wings

It seems unlikely that the NSA can successfully challenge Islamic State without an aggressive recruiting campaign, yet it also seems unlikely to be able to attract more men if it cannot reorient itself.

Ain al-Madina editor Awad told me that the NSA’s popularity among Deir al-Zour residents could improve, but the NSA needs to show real accomplishments on the ground.

On the first day of the offensive, he said, “There was a lot of optimism among the sons of Deir al-Zour, both inside Deir al-Zour and among Deir al-Zour residents in the diaspora. Despite all this opinion on the NSA, the way people see this army could have changed if it had realized a real accomplishment on the ground.

“If it made gains on the ground and seized territory,” he said, “we would see hundreds of fighters join it.”

Aside from the NSA, there seems to be no one else coming to Deir al-Zour’s rescue.

Reports have circulated that the Assad regime will mount an offensive on Deir al-Zour with Russian backing, but so far it has not materialized. Kurdish forces are unlikely to push further south into Arab Deir al-Zour.

The United States and its allies have been unwilling to commit their own troops to dislodging Islamic State—a move which would almost certainly be bloody and counterproductive, and is not currently on the table.

The United States and its allies have been unwilling to commit their own troops to dislodging Islamic State—a move which would almost certainly be bloody and counterproductive, and is not currently on the table.

Instead, U.S. efforts depend on Syrian fighters. But that means the success or failure of the U.S. effort to combat Islamic State, even with an ostensibly new force like the NSA, is wrapped up in five years of Syrian revolutionary politics. The United States has to recruit proxy fighters from the ranks of Syrian rebels who, not unreasonably, believe the United States does not share the Syrian opposition’s agenda. And it has to lean on individual rebel commanders who, after years of war, have their own history.

Those dynamics mean that, whatever the expenditures of the United States and its allies, towns like Albukamal will are likely to remain under the control of Islamic State in the near term. If a faction like the NSA cannot take the town, Albukamal activist Saleh told me, “there’s no one. To put it simply.”

“You have large amounts of fighters divided across many areas inside Syria, and no one will take the lead to decide to go into Albukamal,” he said. “And even if [these other factions] decided [to go in], no one would help them—I’m talking about the Americans.”

What’s left is an American strategy for proxy war nearly unrelated to the actual rebel scene inside Syria. The United States and its allies have invested in a series of Syrian rebel militias—the latest being the New Syrian Army—that were meant to free Syrians from Islamic State.

None of them actually seem up to it—but if they aren’t, it’s not clear if anyone is.

“For now,” said Saleh, “if it’s not the NSA, it’ll be no one else.”

Update: The PR Battle After the Battle (July 13, 2016)

Since the U.S.-backed New Syrian Army was defeated by the Islamic State outside Albukamal last month, the media narrative around the battle has become thoroughly muddied.

In interviews with the Daily Beast and the Washington Post, New Syrian Army (NSA) commanders Khaz’al al-Sarhan and Lt. Col. Muhannad al-Talla’ blamed factors ranging from insufficient U.S. air support to the refusal of other eastern factions to join the offensive to the Islamic State’s advance warning about the attack. Secretary of Defense Ash Carter subsequently confirmed the Washington Post’s reporting, saying the United States “missed an opportunity” by diverting aircraft from Albukamal to strike an Islamic State convoy outside Fallujah, Iraq.

The NSA has since issued an official response to the Washington Post story in which it said the Washington Post distorted its interviews with NSA members. In the statement, the NSA claimed it had not, in fact, been abandoned by Coalition bombers that moved to bomb an Islamic State convoy leaving Fallujah. According to the statement, the NSA had actually been consulted on and agreed to what it called the “difficult decision” to divert Coalition aircraft to bomb the convoy. The NSA said that its response to the Washington Post was prompted “because [it] saw that there are some who want to support the perspective of [Islamic State] and the enemies of the revolution. [It saw] that there are some who try to get a journalistic scoop, even by using lies and exploiting actual facts, at the expense of insulting the blood of our martyrs, insulting and ridiculing our sacrifices, and supporting the narrative of the terrorist organization [the Islamic State].”

Speaking to me over the messaging application WhatsApp, NSA spokesman Muzahem al-Salloum said the Daily Beast article also contained errors. He confirmed that an Arabic-speaker had interviewed Sarhan, but he said, “They spoke with [Sarhan] and lured him into saying things that were then taken out of context.” He declined to point to specific elements of the interview that were taken out of context.

This dispute over who to blame for the rout of the NSA at Albukamal comes after a very public debate over whether the United States hung its proxy out to dry. It also comes, according to several people I interviewed, amidst criticism of the NSA from the Syrian public and pressure on the NSA from its state backers.

With respect to this piece, Sarhan has repudiated the comments attributed to him, claiming that an impersonator assumed his identity on social media.

In the article, I quoted tweets from an account using Sarhan’s name and from a conversation I had with that account over Direct Message (DM). The account had been created on June 29, when it began tweeting praise for the New Syrian Army, appeals to the people of Albukamal, and threats to Islamic State. It also started engaging in a series of running arguments with Islamic State sympathizers.

The account’s tweets and messages over DM (available in full at this link) struck me as agitated and angry but otherwise believable. The account made a number of controversial claims, including that the United States failed to provide his troops with sufficient air cover as promised, that the Islamic State may have infiltrated the NSA, and that a Jordanian officer had helped command the NSA’s forces in Albukamal alongside Sarhan and Lt. Col. Muhannad al-Talla’. Yet the account’s detailed narrative of the battle and most of its arguments—including some of the more controversial points—were similar to those Sarhan made in his interview with the Daily Beast or were corroborated by other interviews I conducted for the article. At the time, I contacted an official in the Authenticity and Development Front, the rebel coalition that includes the NSA, who told me that Sarhan was operating the account.

Sarhan’s personal credibility was wrapped up in the Albukamal offensive, sources told me. In an Islamic State video released the day of the offensive, New Syrian Army collaborators whom Islamic State executed said they had been corresponding with Sarhan before they were captured.

Several days after I spoke to the account on Twitter and after I contacted the Jordanian government for comment regarding the account’s claims, Sarhan posted on his Facebook page (now taken down) that the account did not belong to him. At some point after I spoke with the Sarhan Twitter account, it seems to have tweeted pro-Islamic State messages before being suspended. (I mistakenly reported in my original article that the tweets had been deleted, not that the account had been suspended.) After the publication of my article, representatives for the NSA denied Sarhan was behind the Twitter account and said Sarhan had told them he had no Twitter account. Activist Omar Abu Layla, a friend of Sarhan’s who interviewed him for the Daily Beast article, said on Twitter and in a WhatsApp call with me that Sarhan has no Twitter account.

Reached for post-publication comment over WhatsApp, Sarhan told me, “I don’t know that account, and I have nothing to do with it.” “I don’t care what it says,” he messaged. “All of it is lies.” He said the NSA would issue a statement on the matter.

When I contacted the Authenticity and Development Front official who had originally verified that the account was Sarhan’s, he initially stood by his claim that it was Sarhan on the account. After further review, however, the Authenticity and Development Front official said he could no longer be sure that Sarhan had been tweeting on the account.

Others who are personally familiar with the NSA and Sarhan and who reviewed the tweets from the account and the messages over DM were split over whether the account sounded plausibly like Sarhan.

“That’s him talking. Standard,” said former NSA media activist “Abu Yousef,” now resident in Turkey. Abu Yousef, who asked to use a pseudonym because he no longer wants to be associated with the NSA, told me, “In terms of the style, it’s him.”

Omar Abu Layla, on other hand, said it was “impossible” that Sarhan would talk like this. “‘Praise our Army a lot,’ ha ha ha,” said Abu Layla, pointing to one of the account’s parting remarks. “The person behind this account is an idiot.”

At this point, it isn’t obvious who was tweeting on the account. It may have been Sarhan or another member of the NSA. It may also have been an Islamic State member working to embarrass and discredit Sarhan.

Absent further clarity, we’ve opted to include this note about the Twitter account, the steps taken to vet it, and the debate surrounding it.