This report contains a foreword by John C. Brittain and an afterword by Kathleen Kennedy Townsend.

Foreword

by John C. Brittain

“You know, I’ve come to the conclusion that poverty is closer to the root of the problem than color. I think there has to be a new kind of coalition to keep the Democratic party going, and to keep the country together. . . . Negroes [now African Americans], blue-collar whites, and the kids. . . . We have to convince the Negroes and the poor whites that they have common interests.”

—Robert F. Kennedy1

As a civil rights lawyer for fifty years, I’ve watched time and time again as wealthy and powerful interests have used racial dog whistles to divide working-class people across racial lines. This white identity politics strategy goes back generations. The nineteenth-century South Carolina Senator John C. Calhoun explicitly told low-income white people to ally with wealthy whites in racial solidarity. “With us the two great divisions of society are not the rich and poor, but white and black,” he declared in an 1848 speech; “and all the former, the poor as well as the rich, belong to the upper class, and are respected and treated as equals.”

The divide and conquer strategy on behalf of the powerful has too often worked. From Ronald Reagan’s appeal to “Reagan Democrats” to Donald Trump’s appeal to the “forgotten American,” the right has used racial appeals and then delivered policies that mostly benefited the rich.

Every once and a while, however, progressive politicians are able to reach working-class support across racial lines. As Simon Greer and Richard D. Kahlenberg outline in a new report, Senator Robert F. Kennedy was able to unite voters in his 1968 presidential campaign around seven broadly held American values that appeal across lines of race. Despite substantial changes in America in the intervening years, there is much to learn from this campaign.

While the right wing has long sought to capture and weaponize ideas like “hard work” and “law and order” against people of color, for example, it never made sense to me why progressives should cede these values. People of color want safe and orderly neighborhoods, just like anyone else. And poor people work just as hard—sometimes harder—than their more privileged counterparts. As Jesse Jackson told the 1988 Democratic Convention: “They catch the early bus. They work every day. They raise other people’s children. . . . They drive dangerous cabs. They change the beds you slept in in these hotels last night. . . . They work in hospitals. . . . They wipe the bodies of those who are sick with fever and pain. They empty their bedpans. They clean out their commodes.”

As Greer and Kahlenberg suggest, progressives often embody these and other values at least as much as conservatives, and a hesitancy to invoke value-laden language has been a mistake. Progressives need to learn to be comfortable speaking about values like family that drive Americans—and underline many progressive policies, from a support for paid family leave to a higher minimum wage that allows parents to spend more time with their children. The report “How Progressives Can Recapture Seven Deeply Held American Values” lays out an important framework not just for political appeals, but for unifying our fractured nation.

John C. Brittain is Olie W. Rauh Professor of Law at the University of the District of Columbia David A. Clarke School of Law, and the former chief counsel and senior deputy director of the Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights Under Law.

Introduction

When conservative politicians and pundits invoke “faith, family, and country,” many progressives cringe. On one level, this attitude is understandable. For decades, some leading right-wingers have added a mean-spirited twist to these mainstream values, with sometimes-tragic results. They have invoked “faith” as a reason to restrict the rights of women or gay people, “family” in a way that disparages single mothers, and “patriotism” as a cudgel against those who question wrong-headed wars. So too, politicians have employed “law and order” to evoke fear of black people or to justify putting undocumented immigrants in cages, and valuing “hard work” as code for adopting an overly punitive approach to people down on their luck.

Because progressives appropriately reject the harsh right-wing interpretations of these values and have observed the often divisive and demeaning way they have been wielded in our public discourse, some stopped talking about these ideas altogether, sticking to a discussion of public policy solutions and an array of facts, rather than the powerful values that underlie them. Research suggests this was a mistake, because voters are swayed more by a politician’s articulation of values than policies.2 And our experience tells us this has left progressive movements at a significant disadvantage.

Fortunately, there are some progressive groups working to forge multiracial working-class coalitions who know that ceding this vital ground means progressives sound out of touch with what matters most to Americans and are unable to tap into the deeper motivations that actually drive voters.3 These groups—which are highlighted throughout the report—fully recognize that millions of black, Latino, Asian, and white people alike prize their families, draw strength and resilience from their faith, and find a commitment to country, including military service, a source of great pride. Americans of all backgrounds want neighborhoods that are safe, and believe in the dignity of all work. They share other basic values as well, such as criticizing the powerful rather than ridiculing those who are less fortunate, and avoiding the pursuit of financial and material goods beyond a certain level of financial security. But ownership of these values has not been the provenance of progressives for some years now, as movement after movement has found itself painted outside these lines.

Successful politicians have long understood the power of these values. In 1968, the progressive icon Robert F. Kennedy (RFK) ran a remarkable eighty-two-day campaign for president which was cut short by his tragic assassination. Throughout, he advocated a liberalism without elitism, and a populism without racism. As this report will outline, a close analysis of his campaign speeches and television ads shows that he (1) punched up, but never down; (2) represented the importance of family; (3) emphasized the patriotic duty of Americans; (4) signaled a respect for people’s religious faith; (5) continually underlined the dignity of work; (6) denounced excessive materialism; and (7) emphasized the importance of respecting the law.4

Along the way, RFK forged a powerful multiracial working-class coalition that brought together enthusiastic support from African-American and Latino voters alongside strong support from working-class whites, some of whom had even voted for segregationist Alabama Governor George Wallace in the past.5 As civil rights attorney John Brittain notes, conservative politicians have been trying for eons to divide working-class voters along racial lines, with some considerable success.6 So when a politician like RFK is able to thwart that effort, the campaign he ran deserves careful consideration.

Could RFK’s approach work for progressives more than a half century later? Given the dramatic changes the country has since undergone, would a campaign that emphasizes RFK’s seven themes have resonance today? Drawing upon our collective experience studying Kennedy’s campaign (Kahlenberg) and organizing and building coalitions of unlikely groups today (Greer), as well as conversations with people with diverse expertise and backgrounds,7 this report outlines a path forward for progressives (candidates and movements)—and, more broadly, a path forward for our country.

Part I begins with a brief recap of RFK’s 1968 campaign. Part II outlines some critical ways in which the world has changed since 1968. Part III—the heart of the report—examines in detail seven themes from RFK’s campaign and outlines evidence suggesting these could resonate strongly with Americans today. For each theme, we also highlight some promising ways in which 2020 presidential candidates and key grassroots organizations are beginning to pick up the lost thread of RFK’s approach.

Robert Kennedy’s Remarkable 1968 Campaign for President

On March 16, 1968, Robert F. Kennedy announced that he was challenging incumbent president Lyndon B. Johnson (LBJ) for the Democratic presidential nomination. Kennedy needed little introduction to the country.8 The younger brother of slain president John F. Kennedy (JFK), Robert Kennedy had managed JFK’s campaigns for Congress, the Senate, and the presidency, and had served as the Kennedy administration’s attorney general, where he fought for civil rights and advised his brother in the Cuban Missile Crisis. The year following JFK’s 1963 assassination, RFK was elected a U.S. senator from New York, where he became a champion of the nation’s underdogs, highlighting the need to address poverty and the plight of blacks, Hispanics, and Native Americans. As senator, he also became a leading opponent of LBJ’s Vietnam War.

But as he began his 1968 campaign, RFK faced a major political dilemma. The New Deal Coalition of working-class whites and blacks, which had supported progressive candidates for more than three decades, was in tatters, rent by racial strife and resentment. Should he try to bring these groups back together, or instead seek a new coalition of highly educated whites and minority voters?

The natural step as a pro-civil-rights, anti-war politician was to try to build a political coalition of African Americans, Latinos, college students, and upper-middle-class educated white progressives. But as fate would have it, a particular sequence of events put that coalition out of easy reach by the time RFK joined the campaign. By then, RFK faced in the contest not only Lyndon Johnson, but also a third candidate, U.S. senator from Minnesota and anti-war activist Eugene McCarthy.9

A year earlier, RFK had been approached by peace activists to oppose Johnson’s reelection, but had hesitated. Instead, McCarthy entered the race as an anti-war candidate, and performed surprisingly well in the New Hampshire Democratic presidential primary. Only then did RFK enter the race. By that time, white students and upper-middle class progressives were mostly committed to McCarthy, and many were infuriated when RFK belatedly jumped into the race. As a result, Kennedy had little choice but to try to appeal to both minority voters and less-educated whites who were part of the backlash against racial progress and the peace movement.

Appealing to working-class whites—some of whom had voted for segregationist Alabama governor George Wallace in the past—was not going to be easy. As attorney general, RFK had been a staunch proponent of civil rights. In 1961, after white thugs attacked Freedom Riders seeking to desegregate bus lines, RFK ordered marshals to Montgomery, Alabama. In 1962, he supported James Meredith’s efforts to enroll at the University of Mississippi as the first black student at that college. A year later, RFK urged his brother to submit strong civil rights legislation to Congress. As a U.S. senator, RFK traveled to South Africa, to Appalachia, and to Mississippi to fight for racial and economic justice and forged a profound connection with black voters.

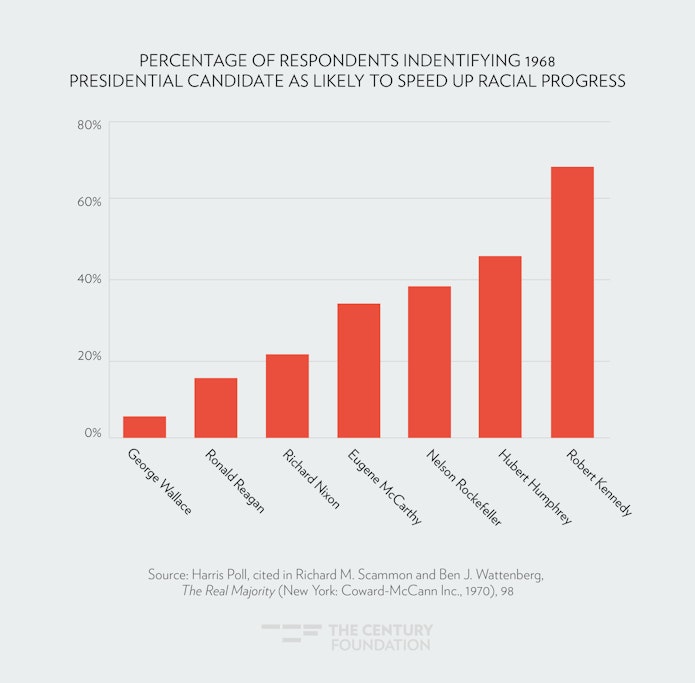

If RFK was at the opposite end of civil rights spectrum from Wallace, voters knew it. In a May 1968 Harris survey regarding seven presidential candidates (see Figure 1), Robert Kennedy was identified as the most likely to “speed up” racial progress (69 percent), while George Wallace was the least likely (5 percent).

Figure 1

Yet in an eighty-two-day campaign for president, through several Democratic primaries, RFK was able to do well not only among black and Latino voters, but also with working-class whites. Through a different kind of appeal (which is outlined in detail below), Kennedy managed to build a formidable coalition of working-class whites and African Americans.10 Without cutting back on his commitment to civil rights, RFK managed to communicate to working-class people across racial lines not only that he would fight for their interests, but also that he respected their values. The ability to simultaneously appeal to working-class whites and blacks—who have been tragically divided time and time again in American politics—explains why RFK’s 1968 campaign holds a special appeal to progressives more than fifty years later.

The United States Has Changed in Several Ways Since 1968

The America of 1968 and the America of today are two very different places, of course. The nation has changed substantially in terms of the economy, union density, political polarization, religious identification, and the dynamics of race and gender, for example—and all these changes must be honestly considered as we assess how to adapt the RFK approach to today’s America.

The Economy

The U.S. economy looks very different today than it did in 1968. For one thing, growth in recent years has been very uneven, geographically. As reported by McKinsey & Company, 2,500 of the 3,000 counties in the United States have a lower median family income today than they did twenty-five years ago, meaning that in most places across the country, families have seen their economic security erode. (See Figure 2.) So much of our economic growth since the 2009 recovery has been confined to very few places. In fact, just seventy-five counties account for half of the nation’s job growth since the recovery, and twenty counties account for half of net new business establishments (those counties represent 30 percent and 17 percent of the population, respectively). If you live in those places, the economy looks like it’s booming. But if you don’t, it’s as though you live in another America.

Figure 2

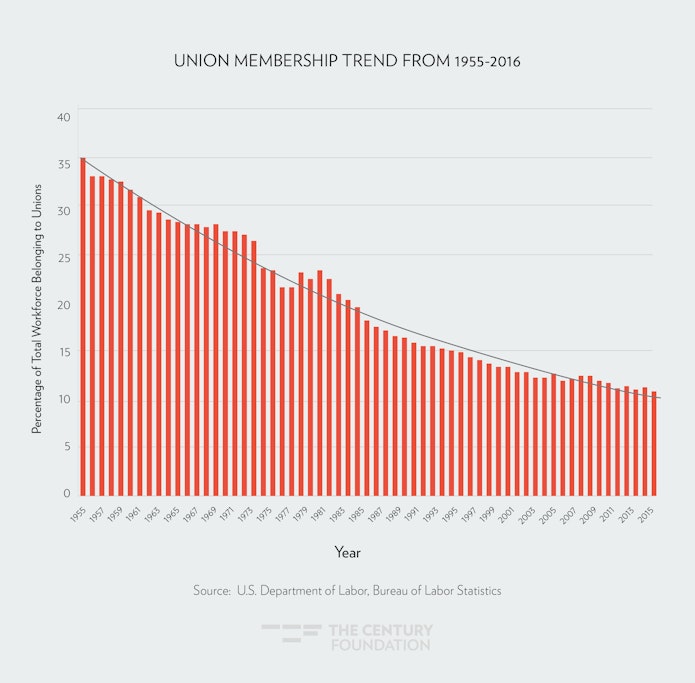

Union Membership

Today’s America also looks very different from RFK’s in terms of union jobs and union workers. The United States has moved from a union density of nearly 35 percent in the mid-1950s, to 27 percent in RFK’s America, to less than 10 percent today (see Figure 3). As a result, one of the strongest mediating institutions in the nation’s history, where people of different racial groups could come together and forge a common bond, doesn’t exist for nine out of every ten workers today.11

Figure 3

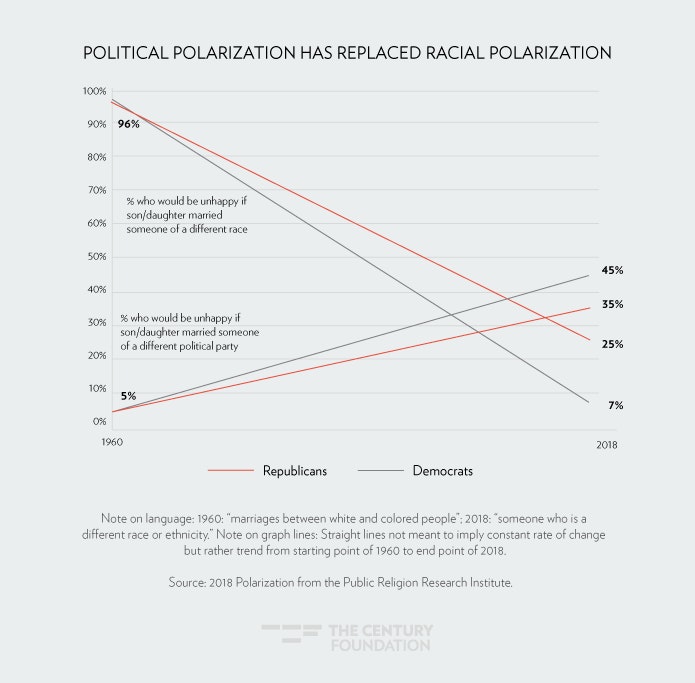

Political Polarization

As some forms of division have slowly declined since the 1960s, political polarization has increased dramatically. In 1960, for example, 96 percent of all Americans were concerned about interracial marriage, but today, among Republicans, only 25 percent say they would be concerned about someone in their family marrying someone of a different race, and only 7 percent of Democrats voice that concern. A lessening of racial division is progress. On the flip side, however, while only 5 percent of Americans were concerned about marriage across different political parties in 1960, today, 45 percent of Democrats would be unhappy if their child married someone from the other political party, and 35 percent Republicans voice that concern.12 (See Figure 4.) Where marrying across party lines hardly registered as an area of concern when RFK was alive, today it has become a major fault line.

Figure 4

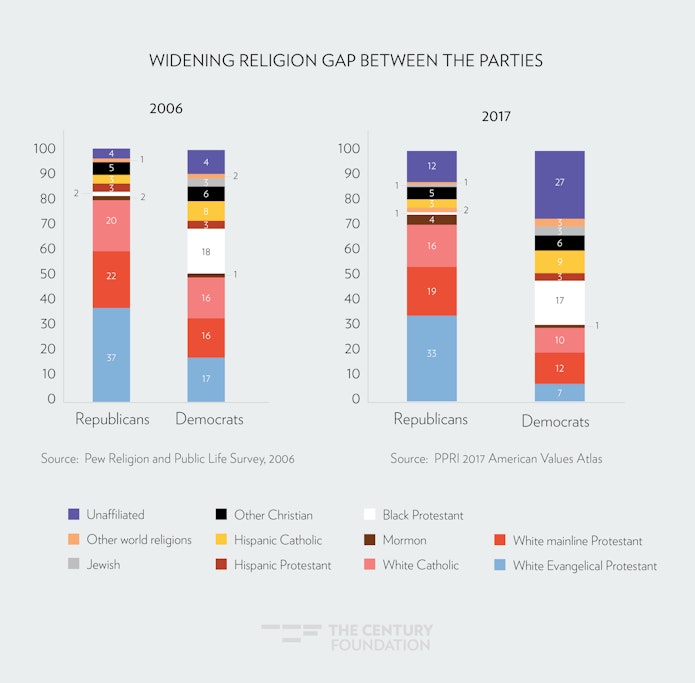

Religion

While the United States remains one of the most religious of the world’s wealthy nations, Americans are less religious today than they were in 1968, a trend that has greatly increased over the past decade. In 2016, for example, Public Religion Research Institute (PRRI) found that, among Democrats, 71 percent were religiously affiliated, down from 90 percent in 2006 (see Figure 5).13 Using religious and faithful language, therefore, will no longer resonate with all, as patterns of belief are much more diverse than they were half a century ago.

Figure 5

Race

Racial dynamics have changed considerably since 1968, a time when white people constituted the vast majority of the U.S. population and generally were seeing improvement in their economic standing. Today, the nation is far more racially diverse, with immigrants coming from all over the world who contribute to the nation’s vibrancy and dynamism. Growing diversity also has a salutary effect on politics: progressives can no longer ignore and take growing constituencies of color for granted, as we stand on the cusp of the nation becoming majority nonwhite (impossible to imagine in RFK’s time).

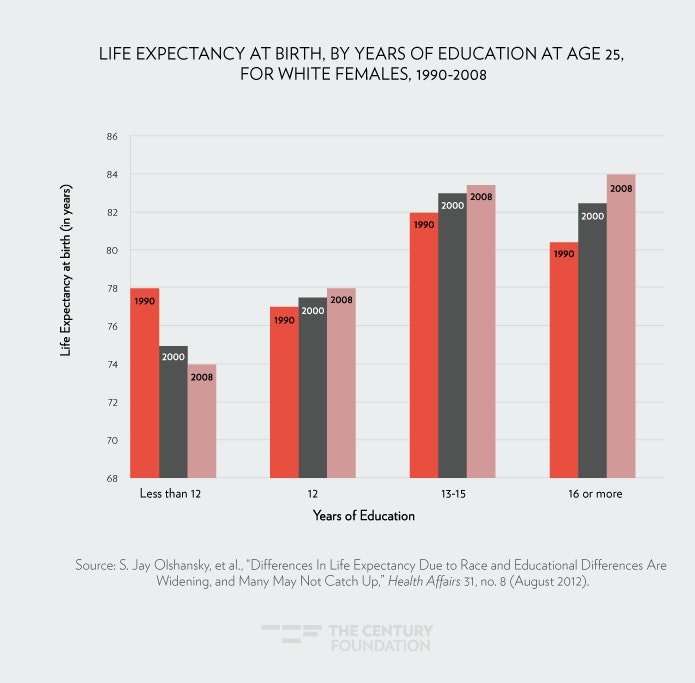

Meanwhile, compared to Kennedy’s day, white Americans with little education are experiencing a downward economic trajectory as well as a downward spiral on the most basic level—life expectancy. The life expectancy of white women with less than twelve years of education, for example, was shortened by almost six years between 1990 and 2008 (see Figure 6); white men with that education level lost three years of life expectancy over that time.14 These are the only demographics that lost life expectancy over that time period. At the same time, on average, white women still live longer than black women, and white men still live longer than black men—but the trend line shows that, if you’re white and not educated, your story is going in the wrong direction, when everyone else’s story is getting better.

Figure 6

This is relevant for political figures trying to build a diverse, class-based political coalition, for an important reason. While it’s still the case that white working-class men and women get to live longer than black working-class men and women, the overall trend line is not positive for them: they still benefit from being white, but they are literally losing ground every year. To a family with this demographic, the idea that they have privilege that they need to give up is hard to imagine. And within this tension lies some of the complexity of building multi-racial coalitions today.

Gender

Finally, gender dynamics have changed dramatically since 1968, as women have made gains in education, workforce participation, pay equity, and equality more broadly, while remaining inequities have helped fuel multiple waves of women’s movements demanding changes in our culture, norms, and behaviors. A few years after RFK’s campaign, men were almost twice as likely to participate in the civilian labor force as women (80 percent as opposed to 43 percent).15 By 2018, that 37-point gap had fallen to 12 points (69 percent for men and 57 percent for women).16 The share of women on payrolls today (which excludes farm workers and the self-employed) actually exceeds that of men.17 The male/female median pay gap has also narrowed, from women making 58.2 percent of male earnings in 1968, to 81.6 percent in 2018.18 Keep in mind that RFK’s campaign took place when Roe v. Wade was yet to be decided at the Supreme Court, experiences of “Me Too” were not talked about in mainstream America, Angela Davis hadn’t been arrested (let alone acquitted), and Betty Freidan had only published The Feminine Mystique five years earlier. While women have made progress on all these fronts, glaring inequalities that remain have helped drive a gender gap in voting behavior that did not exist in Kennedy’s era. In the presidential election directly following RFK’s campaign, the percent of men and women who voted for the Democratic presidential candidate was virtually the same, whereas in more recent years, the gap has often been in double digits.19

Seven Themes of Robert Kennedy’s Campaign and How They Apply Today

Despite enormous changes in American society over the past half century, there is nevertheless good reason to believe that the critical values and approaches Robert Kennedy advanced translate across time, movements, and candidates have relevance to progressives today. Below, we outline seven themes from RFK’s campaign, evidence to suggest the approach could resonate today, and cite promising examples from grassroots organizations and candidates in the 2020 presidential campaign.

Theme #1: Punch Up, but Never Punch Down

RFK, though born to great wealth, managed to convey a populist sensibility. Culturally, “Robert Kennedy had ‘cop’ written all over his public image,” Ted Sorensen wrote.20 And on policy, he championed the average worker. In order to avoid the wealthy escaping taxation through the exploitation of loopholes, for example, RFK proposed the rich pay a minimum of 20 percent in income taxes. He was not afraid to name names, either, his speechwriter Jeff Greenfield recalls. “He would constantly cite” oil tycoon H. L. Hunt, and “would use statistics of 200 people who made $200,000 a year or more and paid no taxes. . . . He kept coming back to those 200 people . . . and then he’d say: ‘One year Hunt paid $102. I guess he was feeling generous.’ If you think about it, there is no better populist issue than that issue.”21 While prominent conservative strategists have forever been trying to divide disadvantaged people by race, Kennedy told journalist Jack Newfield, “We have to convince Negroes and poor whites that they have common interests.” 22

Most progressives today make powerful populist economic arguments about the rich needing to pay their fair share. Compared to conservatives, progressive politicians are much more likely to denounce corporations for stealing employee wages and busting union organizing drives23 that would give workers the power to bargain for decent wages and benefits.24 Today’s progressives call out corporations that pollute the nation’s air and water, insurance companies that try to deny health care coverage, and drug companies that artificially inflate prices. In short, progressive politicians are more likely than conservatives to seek unity among workers—of all races—but it is easier said than done.

The conservative project, meanwhile, has too often been to cleave that coalition by trying to drive wedges into it. Conservative strategists and elected officials highlight the coastal nature of progressive constituencies and note that Democrats control the 10 wealthiest congressional districts in the country, and 41 of the wealthiest 50.25 Right-wing pundits are gleeful when progressive politicians do conservatives’ work for them by punching down and mistakenly driving a wedge even deeper between progressive elites and working-class Americans.

Among the most glaring and troubling examples of punching down was Hillary Clinton’s decision to repeatedly label millions of working-class Americans as “deplorables” in front of laughing crowds at fundraisers in the Hamptons, Martha’s Vineyard, and Beverly Hills.26 To be sure, some Trump supporters engaged in racist and boorish behavior that deserved to be denounced. But by categorizing 30 million Trump supporters as beneath contempt, Clinton gave substance to the conservative narrative that many progressive politicians are hopeless elites.27 As we outline below, there are much more effective ways to respond to racism that don’t condescend to our fellow Americans.

It should be noted that Clinton herself is not a stranger to this game; in 2008, she characterized Barack Obama as “elitist and out of touch” after he said that working-class voters in old industrial towns “get bitter, they cling to guns or religion or antipathy to people who aren’t like them.”28

The simple lesson is that working-class Americans do not want to be lectured about what their motivations are, and ascribing misogyny or racial animus to any group of potential voters is not a winning strategy for building a coalition. Robert Kennedy was quick to denounce racism where he saw it—but if he employed “deplorable” it was as an adjective (to describe statements or actions) not as a noun (to describe a group of people). RFK would drive around less advantaged neighborhoods with his children, his daughter Kathleen Kennedy Townsend recalls. “Those kids want the same thing as you,” he told his children. “Remember, you are more fortunate and lucky, but you are not better than them.”29 He respected people of all backgrounds. There was no condescension, so Kennedy could not be accused of having “forgotten” any group of voters.

Why It Might Resonate Today

Punching up rather than punching down still has strong appeal. About three-quarters of Americans support higher taxes on the wealthy, for example.30 This does not mean, of course, that Americans dislike the rich—most aspire to become financially comfortable themselves, and they think it is good when someone works hard to succeed and makes it.

Donald Trump, paradoxically, was able to pass himself off as a “blue collar billionaire”—someone who had great wealth, but wasn’t seen as looking down on others as morally inferior.31 Progressives unwittingly reinforced this image when they departed from appropriate criticisms of his policies to mock Trump for things such as his misspelled tweets. This punch not only landed against Trump, but also against, say, the highly skilled union welder who may also struggle with spelling and feels personally insulted by the criticism of Trump.

To be clear, it is important to challenge racism or sexism or other deplorable statements by political leaders. But it is possible to do so in a way that doesn’t condescend to working-class Americans of any race, and instead enlists them as allies. According to groundbreaking research by University of California at Berkeley professor Ian Haney Lopez, progressives needn’t (and shouldn’t) ignore the corrosive effects of racism in American society. Most Americans reject such racism, he finds, and it’s a winning narrative to suggest, “No matter where we come from or what our color, most of us work hard for our families.”32 Working-class people of all races are very open to the message that people of different backgrounds all want a better future, yet believe that some politicians try “to pit us against each other in order to gain power.”33 This approach does not deny the reality of racism, but redirects the anger where it belongs—at wealthy interests who seek to divide working-class people by race. The strategy, Lopez notes, doesn’t put working-class whites on the defensive for being racist; it shows how they, too, are hurt when conservative politicians use racial appeals to divide the working class.34

Reverend William Barber, who is leading a modern Poor People’s Campaign, emphasizes the need to overcome racial division within the working class. “Former enslaved people knew that if they could engage white working-class people they could transform the south,” but wealthy white people sowed division out of a “fear of multiracial democracy.”35 Barber identifies the die-hard Trump supporter—the ones who will never give up on him—not as working-class whites, but as “elites whose stock portfolios and personal taxes have benefited from the Trump tax cuts.”36

Another grassroots organization that emphasizes this approach is People’s Action, a multiracial group that seeks to bridge racial divides. George Goehl, director of People’s Action, used this example at one Washington, D.C. rally in June 2018:

Jeremiah Jaynes, a seventh-generation resident of Haywood County, N.C., traveled from the hills of Appalachia, where he grew up planting tobacco and raising chickens, to Washington. Across from the White House, he spoke on behalf of small towns at the “Families Belong Together” march, along with celebrities, activists and immigrants’ rights groups.

“When I was a kid, I didn’t see the big picture,” he said in a gentle southern accent. “I used to think immigrants were a burden on the economy. I used to think it was us against them.” Mr. Jaynes, a member of our affiliate organization Down Home North Carolina, was the first speaker to admit his thinking on immigration had evolved. “But I now know that’s just a big con,” he said. “Immigrants are poor people just like me, and pitting us against each other isn’t the solution. I know who is really hurting my community and it certainly isn’t desperate families and toddlers in cages.” In all these conversations, people recognize that the enemy is not one another but the big corporations—driving up health care costs, taking away jobs, polluting air and water.37

Similarly, Ian Haney Lopez’s research suggests that emphasizing the ways in which powerful interests seek to use race to divide working people is appealing not only to working-class whites, but to working-class people of color.38

By contrast, Lopez’s research shows that punching down is a losing proposition—broad-brushed moral condemnation of white working-class voters as racist backfires and only strengthens the appeal of conservatives.39 In one survey of 3,000 whites, five times as many thought “most people” are “too sensitive” about racial issues compared with those saying people were “not sensitive enough.”40 Whites who are more educated also feel this way. In one experiment, white college students, after being told to think about white privilege, actually grew more racially resentful.41 In a 2018 poll, 80 percent said, “political correctness is a problem in our country,” including large proportions of people of color. Fully 66 percent of those with a postgraduate degree are skeptical of political correctness, and a whopping 87 percent of those who never attended college are.42

“The advocates of tolerance have become the intolerant,” a union member in New Hampshire who worked on the highways plowing snow in the winter told one of us (Greer). Others chimed in: “Oh yeah, they come to New Hampshire wanting me to agree with their issues, but no one cares about what my life’s like as a hunter or where I go to church or the music I listen to. I don’t fit what the tolerant people want me to be like.”

This sense of disinterest or disdain—when coupled with the conservative narrative that progressives are part of an exclusive club—can calcify into a sense of living in entirely different worlds, with dramatically different experiences, interests, and values. When Madeleine Albright introduced Hillary Clinton at the 2016 Democratic Convention, she said that the two of them knew each other from back at Wellesley, and a cheer went up in the crowd.43 A corrections officer in rural Michigan reacted by saying, “when my union members see how of course they knew each other at ‘Wellesley,’ they are gonna jump right on it and say that no one from here ever went to Wellesley but, of course, those elitists are all so proud to know each other from Wellesley.”

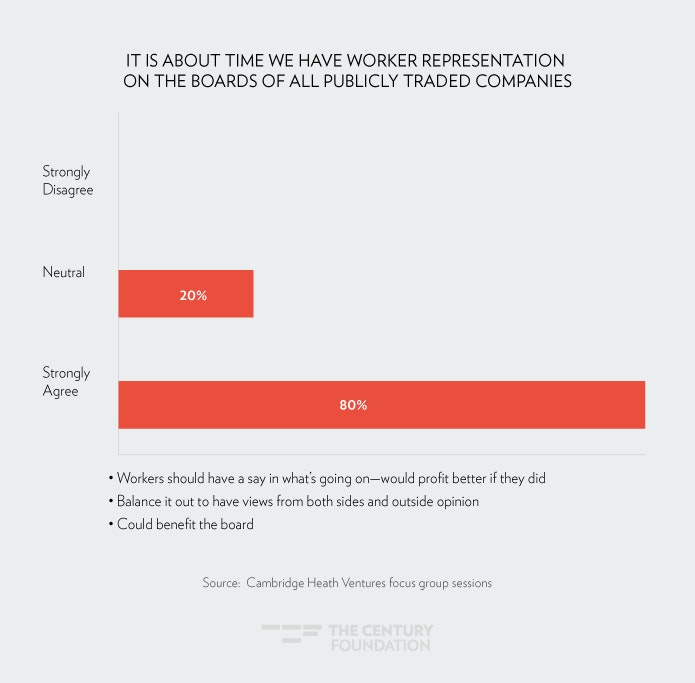

Punching up as a champion of the working class should be a no-brainer for progressive politicians, as their policies far more often speak to the interests of working people and their desire to be heard. For example, in listening sessions led by Greer’s firm, Cambridge Heath Ventures (CHV), eight out of ten participants support putting workers on the board of publicly traded companies, for example—an idea that Senator Elizabeth Warren has championed.44 (See figure 7.) But, as previously stated, voters aren’t swayed by policy alone, they are swayed by values—and so progressive politicians will need to maintain a consistent commitment and message on being a champion.

Figure 7

Exemplars from 2020

Virtually all progressive candidates in 2020 call for higher taxes on the wealthy, but if people know anything about Senator Bernie Sanders, it is that he punches up consistently at the “billionaire class.” Furthermore, Sanders has not been known to punch down at working-class people. And unlike some conservatives, he never punches down at immigrants, minorities, or the disabled. His ire is singularly focused upwards.

Theme #2: Represent the Importance of Family

Everyone in the country knew that RFK cherished his family. He was a deeply loyal family member who worked tirelessly for his older brother’s political campaigns and administration. The extended Kennedy family football games were the stuff of legend. “The Kennedy family” was a well-known phrase in a way that “the Reagan family” or “the Nixon family” were not. RFK was enormously devoted to his own children, and campaign ads reminded voters of his commitment to his large family.45

Today, progressives are correct to expand the definition of family to be far more inclusive than it has been for many older conservatives. (Younger conservatives, including white evangelicals, are more open to same-sex marriages.)46 It is important throughout this discussion to remind Americans that one reason to be for marriage equality, or paid family leave policies, is precisely that family can give enormous meaning and stability in people’s lives, and not just because it is a good talking point.

Why It Might Resonate Today

Family continues to be at the very center of people’s lives and progressives need to make clear that families are at the center of their thinking as well. In the focus groups that one of us (Greer) has conducted around the country, participants are given a stack of fifty cards (from the “Picture Your Legacy™” deck) with different images on them.47 Each participant sorts the cards and pulls out the three images that best reflect the kind of individual they want to be and the values that animate their lives. They also pick three cards that least reflect who they want to be and are least resonant with the values they aspire to live by. Over and over again, participants—not just conservatives, but Americans overall—choose the images of families as the most important.

Family is what we, as humans, care about above all else. The problem is that conservatives have purposely coopted phrases like “strong family” or “family values” to mean anti-single moms, anti-gay, anti-abortion. Too many people in the media and in progressive circles have bought into this narrative, or been scared off by it. Progressives support family as an underlying value, so it’s important for them to fully promote and protect families by taking back this language. One promising sign is the creation of a nonprofit, Family Values @ Work, that is supporting grassroots fights for state and local policies for family leave from work.48

The importance of this family-centered approach plays out among union workers. Again and again, union workers say they support their union not so much for ideological reasons (“fighting against corporate greed” or demanding “economic justice”), but rather because the union helps members better support their families and have more time with them. As one union member said, “I believe in my union because I go home safe from work, because I get to spend weekends with my family, I get to go on vacation with my kids and I can get health insurance for my wife.” Working people, like most of us, will sacrifice anything for their family, and so it’s fundamental that progressives figure out a way to communicate that they are pro-family people.

Progressives know that this emphasis on family is not just an issue of “messaging.” Strong families—in all their modern forms—do make life easier and provide a stable structure in society. They give meaning to individuals and provide a firmer grounding for children to pursue opportunities. As a policy matter, progressives understand this. Commitment to family is central to why progressives support paid family and medical leave policies, affordable high-quality child care, and a higher minimum wage. More progressives just need to learn to say it aloud, to openly reclaim family, and speak with conviction about the structural changes they seek to make in policy and the culture and values that they believe in.

This has consistently been the case at the National Domestic Workers Alliance. As their executive director, Ai-jen Poo, says:

Our work at the National Domestic Workers Alliance has always been about family. We know that the daily, all too often invisible, work of nannies, house cleaners, and other caregivers is the work that makes all other work possible. Every one of the millions of American families who count on someone who works in their home knows how crucial that worker is to the life of the family and the strain on the family that results from not having that person there to rely on. We want to ensure that caregivers and house cleaners are also able to provide for their families and have the dignity and security in their own lives, and the lives of their families, that they contribute to for so many other families through their hard work, compassion and dedication.49

Exemplars from 2020

Today, Vice President Joe Biden emphasizes the importance of family in his campaign. Voters are deeply familiar with the tragedies that he has suffered—the loss of his first wife and daughter in a car accident in 1972; the loss of his older son Beau to brain cancer in 2015. And in both cases, Biden says on the campaign trail, his family came first.

He reminds voters that as a newly elected senator, he commuted home to Delaware on Amtrak each evening. “By focusing on my sons, I found my redemption,” he said in a Yale University speech in 2015. When Biden explained why he bypassed the 2016 presidential campaign, he emphasized that he put his family first to grieve the loss of his son Beau. At campaign events, Biden will often ask people to raise their hands if they have lost a family member to cancer. Writing of Biden, Mark Leibovich notes, “Shared grief offers a universal and very bipartisan space to commune.”50 His is an implicit message that family is even more important than politics.

Senator Elizabeth Warren, likewise, talks about the importance of family with some regularity on the campaign trail, citing the importance of her Aunt Bee. Warren tells the story of when she was a young working mom, with two kids, and her babysitter quit. One day, she picked up her son from a daycare center she was trying out “and found that he had been left in a dirty diaper for who knows how long.” She says, “I was upset with the daycare but, more than anything, angry with myself for failing my baby.” Around that time, Warren’s 78-year-old Aunt Bee called from Oklahoma and asked how Warren was doing. Warren, in tears, told her: “I can’t do this. I can’t teach and take care of Amy and Alex. I’m doing a terrible job. I’m going to have to quit.” Warren continues: “Then Aunt Bee said eleven words that changed my life forever: ‘I can’t get there tomorrow, but I can come on Thursday.’ Two days later, she arrived at the airport with seven suitcases and a Pekingese named Buddy—and stayed for 16 years.”51 Warren acknowledges that not everyone has an Aunt Bee, and tells the story to explain why more families need support.

Theme #3: Emphasize the Patriotic Duty of Americans

RFK opposed the Vietnam War as wrongheaded and immoral, but people also knew that he believed strongly in the duty of Americans—including the wealthy—to defend national interests and American ideals. He served in the military himself, and his brother, of course, famously said, “Ask not what your country can do for you—ask what you can do for your country.” In the same vein, RFK told Notre Dame students that he opposed draft deferments for those in college: “You’re getting the unfair advantage while poor people are being drafted,” he said.52

Today, the issue remains salient. As Stanford University’s Francis Fukuyama notes, “Liberals around the world have lost ground to populists by ignoring the broad moral appeal of national identity.”53 Given the fundamental human need to feel belonging with a community, progressives would be served well by finding ways to own American identity. If they don’t, white nationalists have already shown that they will fill the vacuum.54

When progressives reclaim patriotic duty from the far right, they can generate powerful results. Consider the example of the Western States Center (WSC), which has fought white nationalism by exposing dangerous leaders and championing a genuine patriotism in support of the country. As WSC’s Spokane-based program manager and organizer Kate Bitz explains:

Through our organizing efforts, communities have been able to stand up against white nationalism and the antigovernment Patriot Movement, successfully encouraging conservative institutions to draw a line against bigotry and refusing to allow patriotism to be defined by extremists. In 2018, we used research to support a broad coalition of local Spokane, Washington organizations to expose that Cecily Wright, chairwoman of the Spokane County Republican Party, met with and praised a white nationalist organizer. The local Republican Party responded swiftly, forcing Wright’s resignation and holding a press conference to denounce white nationalist ideology. . . . GOP leaders and community members found conviction in the fact that patriotic duty isn’t defined by the agenda of the antigovernment Patriot Movement, but by doing what’s right according to our values and for our country.55

Why It Might Resonate Today

Today, it often feels as though patriotism has been coopted by the white nationalists. But a lot of working-class people see “nationalist” in a positive light: a “nationalist” is one who loves this country, and so they can’t understand why progressives are uneasy with the word, or why they mock those who say they are nationalists. Progressives need to find a way to thread the needle as President Obama did—acknowledging our country’s deeply troubling history on matters of race, gender, and sexual orientation, while also noting with great national pride the advancement of human rights at “Seneca Falls and Selma and Stonewall.”57

A progressive commitment to patriotism can emerge in unlikely places. Many former soldiers and military veterans work in county or city governments. They feel as though they served once in the military, and are now serving again in the public sector. For them, for example, a commitment to retirement security—championed by most progressives—is seen not as a social welfare program, but as society paying a debt that is owed. As a conservative said in one of the CHV listening sessions, “I served my country and the government I served is obligated to give me what they promised.” The commitment to retirement security is seen as part of a thoughtful plan for the future, and governments that renege on those commitments can be seen as unpatriotic. Furthermore, a national commitment to retirement security can also be seen more broadly as a matter of supporting a basic need, in a nation where more Americans fear exhausting their money in retirement than fear death itself.58

Rob English of the Metro Industrial Areas Foundation illustrates how patriotism can be a source of support for progressive initiatives. He says:

I grew up in a small town in Texas. Faith, Family and Flag were all very important to me. After serving in the United States Army Infantry, I became a professional organizer with the Industrial Areas Foundation (IAF). Since then, I have been part of the largest non-partisan voter drives in Maryland and Ohio. I always ask voters, “What did it mean for you to vote for the first time?” One voter, Sean Tate, explained voting as a returning citizen for the first time this way. He said, “Man, it meant everything to me. Not just the idea of voting but when I walked into the voting place, my old school, I saw my 8th grade teacher behind the check-in desk. My heart sank. I used to cause her hell. She looked surprised to see me. I looked away. Then I saw her finger scroll down the list. I was nervous. All of a sudden, she found my name and said, ‘Yes Sean C. Tate you are on the list. You can vote.’ When she said I was on the list, I felt like I counted. I was somebody.” Every time I hear stories like Sean’s, I am reminded that IAF’s work fundamentally is about the building and rebuilding of America’s democracy where everybody should count. For me, organizing is my vehicle to act on my love for country and work with others to truly make America live up to the aspirations embodied in our founding documents.59

Exemplars from 2020

A number of candidates do a nice job of fusing progressive values and patriotism. Former Massachusetts Governor Deval Patrick, who backs national service as a way of promoting social cohesion, has noted that at times like this of national division, two leadership styles have emerged: “One is to divide us for political gain. The other is to draw us together in addressing common challenges. . . . Both, by the way, are, historically speaking, American. Only one is patriotic. Only one.”60

So too, Massachusetts Senator Elizabeth Warren has emphasized patriotism, frequently citing her three brothers’ military service, and calling for a new “economic patriotism” that seeks to reduce the likelihood that large multinational corporations will move operations abroad, leaving behind devastated communities in their wake. She writes that many companies “show only one real loyalty: to the short-term interests of their shareholders, a third of whom are foreign investors. If they can close up an American factory and ship jobs overseas to save a nickel, that’s exactly what they will do—abandoning loyal American workers and hollowing out American cities along the way.”61

Likewise, on nearly every campaign stop, Mayor Pete Buttigieg highlights his role as a veteran of the U.S. Navy Reserves, recalling his tour in Afghanistan. He pointedly contrasts himself with the current president, who received a draft deferment during the Vietnam War. “We responded to the country’s call to service in very different ways,” Buttigieg says. As a volunteer in Barack Obama’s 2008 presidential campaign in Iowa, Buttigieg says he saw “that some communities were almost emptying out their youth in the military and some were barely serving at all. And I wanted to be on the right side of that gap.”62

Theme #4: Signal a Respect for People’s Religious Faith

Everyone knew RFK was a devout Roman Catholic. Jaqueline Kennedy is said to have quipped, “I think it’s so unfair of people to be against Jack because he’s a Catholic. He’s such a poor Catholic. Now if it were Bobby, I could understand it!”63 Like the leaders of the civil rights and abolitionist movements, RFK was comfortable with making moral arguments that draw upon spiritual language that has deep meaning to millions of Americans.

Today, Americans continue to take great nourishment from religious faith of all types. Secular progressives should be tapping into these deeply held ideas, not disrespecting them.

Why It Might Resonate Today

Although there has been a decline in religious observance in the United States, the vast majority of Americans—and about three-quarters of Democrats—continue to maintain a religious affiliation. Because some conservatives have used religious beliefs to restrict the rights of women to make reproductive choices and to discriminate against gays and lesbians, some progressives shy away from openly talking about their own faith or even showing respect for the religious beliefs of others.

But cutting off this avenue of communications can undercut the persuasiveness of progressive policies. Black and Latino voters, who are core progressive constituencies, attend religious services at substantially higher rates than whites.64

Consider the example of a labor leader who was going to speak at a conservative union local about economic justice and workers’ rights. One of us (Greer) suggested that the labor leader invoke faith directly in her speech. There was a lot of resistance to that leader talking about faith and morality. There were some on staff who said: “this is not a church and you shouldn’t talk about morality.” But the leader chose to go ahead, and declared: “I live by a moral code—a moral code that comes from the family I was born into, the faith I was raised in, and the union where I came of age.” That opening set the stage for a speech that received a rousing standing ovation. The experience underlined the point that faith, family, and country are what most people cherish and they want to see in their leaders someone who shares in their beliefs and aspirations. If you can’t talk about God, country, family (and sports), it is hard to find your way inside the world view of many Americans.

Exemplars from 2020

Among 2020 candidates, South Bend Indiana Mayor Pete Buttigieg has demonstrated a special fluency with matters of faith. Buttigieg, an Episcopalian, told Washington Post columnist Michael Gerson, “We’ve reached a period when it’s almost assumed that faith connects you to the religious right. I think it is important to puncture that.” Buttigieg unashamedly says, “[my] political beliefs are connected to my faith.” He notes, after all, “The words of Jesus are overwhelmingly about the poor, the marginalized.”65 His argument for gay rights is explicitly religious: “That’s the thing I wish the Mike Pence’s of the world would understand,” he said in one speech. “That if you have a problem with who I am, your problem is not with me. Your quarrel, sir, is with my creator.”66

Theme #5: Underline the Dignity of Work

RFK denounced welfare not because “welfare queens” were abusing the system, as Ronald Reagan would later claim, but because RFK believed welfare was “demeaning and destructive of the human being and of his family.”67 Kennedy instead pledged “jobs for all of our people” so that a job recipient could say, “I helped to build this country. I am a participant in its greatest public venture.”68 RFK realized that unemployment had civic as well as material costs. “Unemployment means having nothing to do—which means having nothing to do with the rest of us. To be without work, to be without use to one’s fellow citizens, is, to be in truth, the invisible man of whom Ralph Ellison wrote.” 69

In one campaign ad in which RFK addressed blue-collar Americans, the narrator declares these were the people who did “the real work” in America.70 In so doing, Kennedy may have been channeling Dr. Martin Luther King, who in 1968 told striking sanitation workers in Memphis, “All labor has dignity.” King explained: “for the person who picks up our garbage, in the final analysis, is as significant as the physician, for if he doesn’t do his job, diseases are rampant.”71

Today, progressives should expand the idea that all labor has dignity to include the dignity of unpaid care. The hard work of caring for children, for the elderly, and the disabled should be recognized fully as a form of vital work that is necessary to make a society successfully function. As such, it should be given the economic value, respect, and dignity it deserves.

Why It Might Resonate Today

After years of conservative rhetoric that demonizes welfare with strong racial undertones, arguing for something as basic as the dignity of work can sound racist to some. But hard work is a universal value that is deeply American, and cuts across racial lines. The adage in the African American community that individuals have to work “twice as hard” in the face of discrimination underlines the importance of that value within the community. As Theodore Johnson of the Brennan Center for Justice notes, 67 percent of African Americans identify as moderate or conservative, and a majority agree that “most people can get ahead with hard work.”72

In discussing the dignity of work, it is not enough to focus solely on programs that help the most disadvantaged. In the fight for a $15 minimum wage, for example, progressives correctly argued that workers who make above $15 would also benefit, because a rising floor places upward pressure on wages further up the income scale. But rather than discussing the collateral economic benefits of labor policies aimed at the lowest income rungs, progressives should center on the dignity of all work as a central value for working-class Americans, including how progressive policies are also directly targeted at helping working-class Americans get ahead as well.

The workforce development and jobs movement, Turn Around Tuesday in Baltimore, has successfully woven these ideas together. According to Melvin Wilson, the group’s co-director:

Turnaround Tuesday has placed over 750 returning citizens and unemployed residents in living wage jobs. Every Tuesday morning nearly 100 folks seeking work file into the basement of Zion Baptist Church. We know folks are not there to just get any job. They are in the room because they want to find work that is meaningful to them. Turnaround Tuesday’s success comes down to one word—relationships. Turnaround Tuesday meets with each person one on one to ask what people dream to do for work—what would mean something to them? From these initial conversations, relationships are built on potential workers’ self interests, what is important to them, not on plugging them into a program. By recognizing the dignity of the worker and work, Turnaround Tuesday is providing meaningful opportunities to hundreds, many of them gaining promotions, buying their own homes and sending their children to college.73

Progressives also need to find a better way to honor the expertise that workers can bring into important causes that uplift the disenfranchised. When discussing criminal justice, for example, progressives typically start by looking at the treatment of incarcerated people, the structural injustices in the conditions of confinement, and the racial disparities in the system overall. This makes sense, because entire communities have been devastated by systemic policies that are racially biased with terrible consequences for millions of families. Often left out of the conversation, however, are the corrections officers on the frontlines of this crisis—the labor force that will be tasked with implementing any reforms. Their views—and their needs—are also essential. 74

Take, for example, the reform priority of expanding educational opportunities for those who are incarcerated. Through the One Voice initiative,75 one of us (Greer) has worked closely with corrections officers from Michigan, including an officer named Carlton, who believes in such programming but thinks the execution is flawed. He worries about “idle hands,” and knows all too well that an active prison population is safer for everyone behind the walls. As a Christian, he says, “I believe in redemption.” He believes that training inmates for a fresh start can be essential to giving them a second chance.

Yet Carlton has also seen what happens when he and his fellow officers are asked to do too much with too little. He’s seen how chronic understaffing and mandatory overtime runs up against program demands. As he says, “In the housing unit where I work, there are 220 incarcerated people and two corrections officers, and so when they want me to run [an inmate education] program, they want me to leave my partner alone, 220 to 1, I won’t do it. We’re like the Marines, we don’t leave anybody behind.” He went on to say, “so I’m not against programming, I’m against these impossible choices.”

Carlton has the kind of first-hand knowledge progressives need to make prison reform solutions smarter and more resilient. Moreover, staff buy-in will be crucial to the success of any potential reform—and that can only be achieved if staff is heard, acknowledged, and respected. His priorities—mandatory overtime, understaffing, PTSD, and one of the highest suicide rates of any profession—should be reform priorities as well, but have been mostly overlooked so far. And, it should come as no surprise that when opportunistic political leaders talk about a “forgotten America,” men and women like Carlton find themselves drawn to their rhetoric, rather than to rhetoric about inventing the future of the industry that paints them as the enemy and seems to leave them behind.

Exemplars from 2020

Today, Senator Sherrod Brown is most well known for speaking of the dignity of work. He says, “When you love this country, you fight for the people who make it work.”76 Former president Barack Obama, too, worried about dependency that can come from overreliance on welfare programs. “As somebody who worked in low-income neighborhoods, I’ve seen where people weren’t encouraged to work, weren’t encouraged to upgrade their skills, were just getting a check, and over time, their motivation started to diminish.”77 Some 2020 candidates have picked up this line of thinking. Vice President Joe Biden, for example, says on the campaign trail, “My dad had an expression. He said, ‘Joey, a job is a lot more than a paycheck. It’s about your dignity. It’s about respect.”78

Former New York City Mayor Michael Bloomberg also talks a lot about the importance of work. The son of a bookkeeper and a secretary, Bloomberg became enormously wealthy, he says, in part, through sheer perspiration. “I’m not the smartest guy in the room, but nobody’s going to outwork me,” he says. During college, he worked every summer in a faculty parking lot and today, he says, he hires young employees not based on past accomplishments so much as work ethic. The applicant who says, “My father never existed, my mother is a convicted drug dealer. I worked three shifts at McDonald’s.” Bloomberg says, “That’s the kind of kid I want.”79 On the campaign trail, Bloomberg says Donald Trump “looks out for people who inherited their wealth, like him, and I’m self-made.”80

Theme #6: Denounce Materialism When Envisioning What Matters

Among RFK’s most famous speeches was one in which he put material interests in their proper context. At the University of Kansas in March 1968, he said:

[The] Gross National Product counts air pollution and cigarette advertising, and ambulances to clear our highways of carnage. It counts special locks for our doors and the jails for the people who break them. It counts the destruction of the redwood and the loss of our natural wonder in chaotic sprawl. It counts napalm and counts nuclear warheads and armored cars for the police to fight the riots in our cities. It counts Whitman’s rifle and Speck’s knife, and the television programs which glorify violence in order to sell toys to our children. Yet the gross national product does not allow for the health of our children, the quality of their education or the joy of their play. It does not include the beauty of our poetry or the strength of our marriages, the intelligence of our public debate or the integrity of our public officials. It measures neither our wit nor our courage, neither our wisdom nor our learning, neither our compassion nor our devotion to our country, it measures everything in short, except that which makes life worthwhile. And it can tell us everything about America except why we are proud that we are Americans.81

Today, progressives should continue to fight for policies that improve the living conditions of economically struggling people, but they must also offer voters a larger moral vision. As Harvard philosopher Michael Sandel has noted, appealing to working-class voters primarily based on material interests—rather than tapping into deeper feelings about democratic citizenship and community—can come off as too transactional.82

Why It Might Resonate Today

While it might have been easier for a politician like RFK to denounce materialism in 1968—a time of economic plenty and rising expectations—there is reason to believe that Americans still believe deeply that material comfort is only a piece of what makes life fulfilling. In the exercise described above where participants are given a deck of “Picture Your Legacy™” cards as part of exploring their values, the images of materialistic items such as mansions, yachts, and skyscrapers are the ones that people chose as least resonant. Whether they’re Muslims from Virginia or African Americans from Alabama or whites from central Pennsylvania, again and again, they are turned off by materialism.

Exemplars from 2020

Entrepreneur Andrew Yang has spoken powerfully about the ways in which Americans search for deeper meaning in their lives. “The problem is one of reconstituting the means of structure, purpose, and fulfillment in people’s lives,” he says. “There’s a real loss of meaning for many people in this country.”83

Theme #7: Emphasize the Importance of Respecting the Law

Unlike other candidates in 1968, RFK saw no contradiction between supporting civil rights as a way of affirming the dignity of all individuals regardless of skin color, and maintaining law and order. He was at once the candidate most associated with advancing civil rights for African Americans, and the one who reminded voters that he had been the nation’s “chief law enforcement officer.”

During the campaign, RFK told his media advisor Donald Wilson, “I want a law and order ad. Why don’t we have a law and order ad?” So the campaign developed several on this theme. One advertisement, signed by one hundred law enforcement officials, said Robert Kennedy was the best candidate able to deal with violence in the streets. Wilson recalls, “We had some of the most important law enforcement officers in the United States flying into Indianapolis” to make an ad.84 In another advertisement, Kennedy tells an audience in Columbus, Indiana: “I don’t think we have to accept the idea that summer after summer we’re going to have violence. I don’t think we have to accept the idea that summer after summer we’re going to have looting.”85 RFK did not want to cede the term “law and order” to conservatives. Richard Nixon was astonished that Kennedy was seen as “more a law and order man” than Nixon was.86

Today, it is usually conservatives who invoke “law and order” in a mean-spirited way to suggest they want to specifically crack down on two groups—African Americans in the inner city and undocumented immigrants from Latin America—as opposed to lawbreaking wherever it occurs. After decades of misuse as a weapon against people of color, it is understandable that progressives shy away from the concept of law and order when it has been translated today into policies such as “stop and frisk” that are disproportionately applied to young men of color. Progressives should continue to reject this racially charged meaning of law and order. But, like RFK, they need to recapture a common sense idea—we are a society that embraces laws and wants to maintain order, alongside justice—lest voters incorrectly conclude that progressives are perfectly fine with lawlessness and disorder.

What would a balanced embrace of order and compassion look like? It wouldn’t selectively apply “law and order” to low-income communities of color; it would call for law and order in the Oval Office of the White House, and the suites of Wall Street. “Tough on crime” would include universal background checks for gun purchases to reduce the homicide rate. It would mean tough punishment of employers who engage in wage theft. It would suggest that border security policies include strong penalties against lawbreaking U.S. employers who exploit immigrant labor. It would mean severe punishment of cop killers, as well as of cops who unlawfully kill people.

Why It Might Resonate Today

There is reason to believe that blending a respect for the law with civil rights could resonate with the many Americans seeking that balance. Rob English of the Industrial Areas Foundation observes:

Most communities are either over-policed or under-policed. When Metro IAF goes door to door in neighborhoods, we don’t hear residents saying, “F the police.” We meet ordinary fathers, mothers, grandfathers, grandmothers, aunts and uncles concerned for the safety of their families. They dream of the days they will not be held hostage in their homes due to the violence in the streets. In the same breath, they say they need cops to be accountable, what any American deserves. That is why Metro IAF has worked simultaneously with law enforcement to make communities more safe and hold them accountable to constitutional policing through the Department of Justice and other agencies.87

Likewise, just as RFK weaved together law and order and civil rights, an acknowledgement of the importance of the rule of law accompanied with compassion on the issue of immigration policy may connect better with voters.

Recently, in a church in New York City, one of us (Greer) organized a group of progressives and conservatives to talk with a woman named Deborah, who had emigrated from Guatemala. She told the story of crossing the border seeking asylum and being allowed to enter the country and being told she would receive a notice to appear at a hearing. She explained that she moved around a lot, and never received the notice. Then, ten years later, she was driving her son to the hospital, when she was pulled over. It turned out that she was driving without a license, which, when entered into the system, triggered a notification about her missed immigration hearing, and now she was facing immediate deportation.

As she was speaking, some members of the group expressed feelings of empathy and compassion—they worried about Deborah being deported and her kids being left alone or getting sent back to a country they don’t know. Other members spoke to the need for the law and order, and to follow the rules. This cross-ideological group had previously spent time building relationships, so they were able to talk about the issue, albeit with some degree of tension. One of the conservative members of the group, Matt, who was a strong Donald Trump supporter and a corrections officer, pointed out that Deborah had broken the rules, that she was told she would receive a letter to attend a hearing, and it didn’t really matter that she failed to receive it. If you don’t get a bill from a credit card company, you still have to pay it, he noted. Moreover, she drove without a license, which was strike two.

One of the progressives in the group stepped in and said that maybe there was a middle ground, where the empathy and compassion she felt toward Deborah could be married to the law and order that Matt believed in. She said, “What strikes me more today and I really want to share is that I see how Matt and the rest of you in law enforcement are hyper-vigilant. You watch every little detail and it keeps me safe. It allows me to lead with compassion and empathy while you are tucking those away so you can coldly watch for any threat to us. And so really I should just say thank you.”

When she finished we got up to leave and Matt walked over and offered to give Deborah some money. Afterwards, he remarked, “I thought one good meal would be better than none.” It was a fascinating interaction. Perhaps because Matt felt his law and order concern was honored by the discussion, he felt more comfortable showing the empathy and compassion that is a part of what all humans feel. By contrast, when someone like Matt doesn’t think the law and order side is appreciated, he may double down. Perhaps when we validate other people’s legitimate values, they are more likely to open up to the other things they feel.

Exemplars from 2020

Successful progressive politicians have been able to merge a call for justice with a call for order. For example, President Barack Obama told the 2015 convention of the International Association of Chiefs of Police, “I reject the narrative that seeks to divide police and communities that they serve. I reject a story line that says when it comes to public safety, there’s an ‘us’ and a ‘them.’”88

In the 2020 campaign, politicians from both major political parties have called for blending a respect for the law with a respect for immigrants. Former Massachusetts governor Bill Weld, who is challenging President Trump for the Republican nomination, has spoken about the need to respect the law but also to infuse his immigration policy with compassion. A former federal prosecutor, Weld says he wants immigrants to be deported if they commit a serious crime and thinks “sanctuary cities” should not receive federal support. But he marries those positions with opposition to Trump’s policy of separating children from adult immigrants at the border and says people who “have risked their lives in dangerous desert border crossings,” contribute to the nation, and obey the law should have a pathway to citizenship.89

Likewise, Democratic Minnesota Senator Amy Klobuchar merges respect for the rule of law and compassion on the issue of immigration. A former prosecutor, Klobuchar opposes proposals championed by some progressives, such as decriminalizing illegal entry into the United States and abolishing the Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE). At the same time, she frequently speaks about the contributions of immigrants, noting, “immigrants don’t diminish America; they are America.” She upends the usual conservative rhetoric around “amnesty” for undocumented immigrants, arguing: “I believe we need to have order. We need to have adequate border controls, the fence, and no amnesty for companies hiring illegal immigrants.”90 In this way, she supports respecting the law in a way that punches up at employers rather than down at those trying to improve lives for their families.

Conclusion

Journalist Fareed Zakaria has noted that if the cardinal sin of the right is racism, the primary sin of the left is elitism.91 Unless more progressives learn how to embrace openly and unapologetically the mainstream values that drive Americans, those on the left will increasingly be seen as distant and aloof.

While sometimes the promotion of these seven values is framed as appealing to the “center” rather than playing to the “left,” that is not our view. The contention here is that these values—which over recent history have come to be defined as “conservative”—actually are deeply held by Americans of all racial, religious, ethnic, and political backgrounds. So it isn’t playing to the “center” to contend for these; rather, it is seeking to manifest these values to find common ground with the millions of Americans who share them.

Fortunately, as noted throughout this report, several grassroots organizations today are championing the values that Robert Kennedy ran on, including Reverend William Barber’s Poor People’s Campaign; Ai-jen Poo’s National Domestic Workers Alliance; Eric Ward’s Western States Center; George Goehl’s People’s Action; Matt Morrison’s Working America; Family Values @ Work, and the Industrial Areas Foundations. (For more information about these groups, see Appendix 1.) These organizations take a humble approach to listening and respecting others that is the key to any good relationship.

Many of these and other successful groups understand the ingredients that are essential to successful engagement across lines of difference. In an approach called Courageous Conversations, Greer teaches:

- No one group has a monopoly on solutions, and so we should engage with others not as if they are a mortal enemy to be vanquished, but fellow Americans with whom we seek to solve problems.

- Listen and be curious. Success is not showcasing for your own political “team” how ideologically pure you are, nor is it barraging someone who sees things differently with as many facts, figures, and arguments as you can array against them. Success is really understanding the subtleties of what they think, why they think what they think, and how they came to hold that point of view. By seeking deeper motivating values for why people think what they think, there is more room to find understanding, and maybe even alignment.

- You aren’t diminished by taking seriously ideas you disagree with. Some argue that we “validate” the “opposition” by listening to them and giving them airtime. Instead, try bringing their perspectives, even the mean-spirited ones, out into the light. We are actually enhanced through our proximity to ideas we disagree with. When we take opposing ideas seriously, we may well see parts of the truth we hadn’t seen before; even if it is hard to swallow.

- You can respect, even love, people with whom you disagree. Too often in today’s culture of blocking, canceling, and calling out, we turn political opponents into demons to be vanquished. Disagreement can become blasphemy and the disagree-er irredeemable. But Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. said, “Darkness cannot drive out darkness; only light can do that. Hate cannot drive out hate; only love can do that.”

- This is not just messaging but an integral part of solutions. Not that we should embrace others’ ideas to “get them,” but because there is wisdom in those points of view.

- Many “conservative” ideas exist within people who might be called the “progressive base,” and so we should welcome them and all that they believe.

These progressive groups—and the progressive candidates who are tapping into Kennedy’s approach—point to a better future for the country, on three levels.

First, as a simple matter of electoral math, progressives need to be able to speak forthrightly about values. As Lee Drutman, a New America fellow, has demonstrated, bread and butter economic appeals coupled with avant-garde social values are unlikely to be a winning formula in American politics.93

Second, learning to talk about values is important for social cohesion in the United States. America is engaged in “the world’s most radical experiment in democracy,” Heather McGhee of Demos notes, because we are “a nation of ancestral strangers that has to find connection even as we grow more diverse every day.”94 Common values such as family and country can unite people who otherwise would only see different backgrounds and perspectives. Moreover, beneath the political crisis that sees our country tearing itself apart there is, in reality, a spiritual crisis in which we dismiss those we disagree with as the “other” and in some ways less than human. This happens across the political spectrum and it diminishes as all. By re-committing to our values and the inherent dignity in each of us (regardless of politics), we can re-establish the basis upon which democracy functions.

Third, learning to articulate values that bind Americans is critical to addressing the gaping class divisions that have only grown worse since RFK’s campaign of 1968. Because of Donald Trump’s strong appeal with white working-class voters, a New York Times analysis found, the GOP has become “the party of the left behind.” Trump “won 58 percent of the vote in counties with the poorest 10 percent of the population,” while Democrats prevailed in the richest counties.95 A progressive political coalition of wealthy whites and minorities may sometimes prevail, but the tragic racial divisions within America’s working class make it less likely that either party will fully address growing economic inequalities in society. As the journalist John Judis has noted, a divided working class makes impossible the historic commitment of progressives “to achieving equality by building a movement of the bottom and middle of society.”96

Robert F. Kennedy demonstrated that it was possible to appeal to disparate working-class voters at a time of enormous racial division. If approached with intelligence and skill, and a commitment to broadly held values, it may be possible to bring a surprising number of these Americans together once again.

Afterword

by Kathleen Kennedy Townsend

When my father, Robert F. Kennedy, ran for president in 1968, he appealed to a broad cross-section of Americans. He received enormous support from African American and Latino voters, who knew he was a strong champion of civil rights and the poor, and he also received strong support from working-class whites, who knew he cared about their futures, too. It’s been often said that he was the last liberal politician to truly communicate across this racial divide.

My father fought for certain policies to make the country stronger and fairer, but as Simon Greer and Richard Kahlenberg’s report points out, he connected with people on the level of human values as well.

Obviously, the fact that he came from a family of nine children, and had produced ten, with an eleventh on the way, demonstrated his devotion to family. Family seemed omnipresent when his brother, President John F. Kennedy, ran for office, and that image of a large, connected Kennedy family embedded in the hearts of many.

The same could be said of faith. The fact that his brother was the first Catholic president projected that we were a family of daily masses, rosaries, and nuns and we were happy to pray for him.

In short, he didn’t have to work very hard to convey faith and family. But what strikes me now is how he also made a point of emphasizing the dignity of work, patriotism, and respect for people of all backgrounds. His support for these values came through in his speeches, of course. But I also saw it close up in the lessons he conveyed to my brothers and sisters and me.

His belief in the dignity of work shone through in his own devotion to work, and in the way he treated people, from thanking the kitchen staff to his friendships with men of great accomplishments, such as Jim Whittaker, the first American to climb Mount Everest, to John Glenn, or Harry Belafonte.

It also came to life with the launch of the Bedford Stuyvesant Restoration Corporation—the first community development corporation established in the United States. He had been campaigning for U.S. Senate in New York, and was asked what he was going to do for the unemployed people of Brooklyn. Unlike most senators, who typically think in terms of passing legislation, he wanted to get something done that would actually create jobs as soon as he was elected. So, he worked with community groups and Tom Watson of IBM to create the Bedford Stuyvesant Corporation. In the course of this effort, he spoke about the problems that unemployment brings: “We know the importance of strong families to development: we know that financial security is important for family stability and there is strength in the father’s earning power. . . . Unemployment is having nothing to do, which means having nothing to do with the rest of us.”

My father saw that work gave man not only money, but standing in the community. A job meant that a person is not only earning, but he (or she) is contributing, participating, has a role to play, is important, has a purpose: “If men do not build, asks the poet, then how shall they live? . . . Work is the meaning of what this country is all about. We need it as individuals. We need to sense it in our fellow citizens. And we need it as a society and as a people.”