Since the advent of online education, some colleges and universities have looked to third-party companies for help developing, marketing, and providing their online degree and certificate programs. But in recent years, those companies have expanded to run more and more of their clients’ online programs. An industry has developed around online program management. This industry now encompasses companies (OPMs) that provide single services—like instructional design assistance or video production—as well as full-service providers. These full-service OPMs have taken on a more expansive role, essentially creating white-label courses that are rebranded as if they were designed by universities.

The relationships between institutions and OPMs sometimes make life easier, or start-up costs lower, for institutions looking to branch into the online student market. However, they come with serious risks, for students and for the colleges themselves. As both New America and The Century Foundation have previously explored, there are tipping points for colleges—points where the OPM is operating a large share of the school’s online programs, or enrolling a substantial portion of the school’s student population; where the OPM is demanding a share of the revenue from online programs that is unsustainable, or locking the school into long-term and onerous contracts; and points where the OPM has captured too much of the academic activity that should be the purview of the institution.

Given these companies’ intimate involvement in aspects of institutional and departmental affairs, it is critical for accrediting agencies to provide close, effective oversight of the partnerships between their member institutions and OPMs. Such oversight is doubly important because accrediting agencies are the only regulatory entity obligated to review and sign off on these arrangements. For this report, New America and The Century Foundation collaborated to analyze the current practices of accreditors regarding OPMs.

Our analysis concludes with recommendations for both accreditors and policymakers. For their part, accreditors need to review relationships more closely between educational institutions and OPMs. For instance, accreditors should examine OPMs’ past performance, consider their marketing materials and growth targets, and scrutinize the proposed governance structure for new programs involving OPMs. Policymakers can complement these changes with stronger prohibitions on incentive schemes that encourage OPMs to recruit as many students as possible; by insisting on greater transparency of OPM contracts; and by mandating reviews of accrediting agencies. Only by implementing significant changes can both institutions and students be protected.

Accreditors’ Reviews of OPM Contracts

A close review of accrediting agencies’ policies and standards provides important insights into how agencies consider, review, and approve contracts between their member institutions and OPMs. We explored several aspects of this review process: the types of arrangements that accreditors consider for approval, the specific standards or principles accreditors rely on in reviewing OPM arrangements, the type of information agencies ask for, and how agencies confirm that the programs meet their standards. Industry and policy analysts alike employ a range of terms and acronyms to describe the companies that universities work with to provide online programs. We use the term “OPM” to broadly refer to any company with involvement in the development, marketing, delivery, or management of online programs.

For the purposes of this report, we focused on the accrediting agencies that are responsible for oversight of most public and private nonprofit colleges in the United States (in other words, regional agencies), rather than the accreditors that often oversee more for-profit institutions.1 When we refer to accreditors throughout this brief, we mean those agencies that we reviewed.2 While for-profit colleges receive much of the notoriety around their online programming, much of the OPM market actually operates within the public and nonprofit sectors, frequently in graduate education (although OPMs are increasingly enrolling students within the undergraduate education space, as well). Public colleges also tend to be subject to greater transparency, including open-records laws, which facilitated The Century Foundation’s ability to request and receive actual contracts from those institutions for review.3 This brand of contracting—in which public and private nonprofit colleges outsource key functions to for-profit companies—also warrants greater scrutiny, as it represents the transfer of public (or publicly controlled) resources and power to private entities less subject to transparency or accountability.

Moreover, there are numerous high-profile examples of for-profit colleges that have outsourced their programs to related entities (like for-profit Grand Canyon University, which outsources much of its online programming to Grand Canyon Education, a for-profit, publicly traded company headed by the president of the university). But these relationships between two for-profit entities tend to raise a broader set of questions about the legality and appropriateness of their models. This model, while not discussed in great detail in this report, can be further explored in The Century Foundation’s October 2020 report “How For-Profits Masquerade as Nonprofit Colleges.”4

In our review of accrediting agency policies, we found that most agencies review OPM contracts in the same ways that they review any other contractual arrangement between a college and another entity. That process, in most cases, involves relatively little scrutiny on the financial arrangement behind the contract, the governance model under which it operates, or the past successes and failures of the OPM contractor itself. In some cases, this light regulation appears to have led to OPM arrangements and programs that do not live up to accreditors’ standards, or that have imperiled an institution’s ability to operate stably and independently.

Which Types of OPM Arrangements Are Evaluated?

The accreditors we examined all evaluate arrangements with third-party entities, but whether and when an accreditor evaluates an OPM arrangement depends on the accrediting agency. At a minimum, agencies at least review OPM contracts that fit the federal definition of a “substantive change” for an institution, which accreditors are legally obligated to review if an institution is offering federal financial aid to students in the program. A relationship that outsources at least 25 percent of a program to an unaccredited entity is considered such a “substantive” change.5 Outsourcing arrangements of more than 50 percent of a program are ineligible for federal financial aid.

Because it is often difficult to even define an OPM, some online program management companies may slip through the cracks of review.

All regional accrediting agencies include standards that cover OPMs under broader umbrella substantive change policies for unaccredited entities or other contractors to which institutions may outsource their programs. However, in most cases, accreditors’ substantive evaluations of contracts do not distinguish between OPMs and other unaccredited entities (like coding bootcamps, for instance). In other cases, agencies distinguish between contractors that perform certain services and those that constitute a written arrangement to offer an educational program. Because it is often difficult to even define an OPM given the differences in services and terms found across the landscape of institution–contractor partnerships, some online program management companies may slip through the cracks of review. For instance, one accrediting agency’s policy on related entities, where the accredited university engages an unaccredited but corporately related organization, specifically states that “the scope of this policy does not include contractual relationships in which the accredited entity contracts for services, such as shared services in recruitment, academic advising, information technology support, or online program management.”6

Only one agency, the Northwest Commission on Colleges and Universities (NWCCU), includes a trigger in its policies for closer review of OPMs. This trigger was established after the NWCCU-accredited Concordia University closed abruptly, apparently in part due to a financially unsustainable relationship with an OPM.7 NWCCU recently took steps to require an additional evaluation of any third-party relationship if it is with an OPM, and is engaging in a process to review existing approved OPM arrangements.

How Do Schools Apply for Assessment of OPM Arrangements?

Although agencies all maintain standards for reviewing contracting arrangements in which some programs are outsourced, the rigor of those reviews is unclear. Agencies rarely rely on a metrics-based system for evaluating these standards, and instead generally rely on qualitative information provided by institutions. Further, the accreditors we studied hold the institution to be primarily responsible for the quality of education, regardless of whether that education is being provided by the institution itself, and do not individually review programs. Thus, agencies rarely ask for information on a contractor’s past performance.

Generally, accreditors do not state what information they ask for in their standards or policies (only one accreditor we analyzed did so). Instead, they give institutions a verbal or written list of information to submit once the college has signaled its intent to enter a written arrangement with an OPM. We also found that agencies often request different information from an institution depending on its arrangement or proposed arrangement. Some of the most common pieces of information accreditors ask for to evaluate an OPM arrangement include the level of control each party holds, the nature of the services the OPM will provide, the length of the contract, and the cost of the services. However, only two accreditors we reviewed require institutions to submit the actual OPM contract they are considering; and few asked for information on the partner’s history with institutions. Only one accreditor we reviewed asked for evidence of conditions under which the contract could be terminated and venues for addressing perceived breaches of contract. If other accreditors asked for this kind of information, it was either not publicly stated in their standards or unclear from our interviews with them.

Additionally, while some accreditors’ standards and policies appear more rigorous than others, this rigor doesn’t always appear to lead to different or better results. Some contracts between schools of different accreditors looked very similar, and received approval from multiple agencies. On paper, the New England Commission on Higher Education (NECHE) has one of the most detailed “checklists” to which member institutions may refer, outlining the elements that should be included in contracts.8 However, this list appears to be merely suggestive and not necessarily a set of criteria for assessing the soundness of the partnership. For example, NECHE’s list of recommended contractual elements specifies that contracts should “explicitly define how the faculties of accredited entities will periodically review the courses and programs,” an important aspect of ensuring proper academic governance. But because NECHE does not appear to require this element, its institutions are not necessarily held to that standard. For instance, documents obtained by The Century Foundation show that the University of Rhode Island entered a contract with the OPM Academic Partnerships in 2014, an agreement that was presumably reviewed by NECHE. But the contract does not include the detail related to faculty review that NECHE recommends. In fact, the University of Rhode Island’s contract with Academic Partnerships looks nearly identical to other contracts the company has signed with institutions accredited by other agencies.9

A tailored approach to information requests for OPM arrangements, like the individualized requirements that agencies often employ now, is aligned with accreditors’ belief that the institutions are responsible for establishing an appropriate contract and conducting sufficient due diligence. But a lack of standardized information requests even within a given accrediting agency means that there is no baseline for what accreditors are looking for and could lead to inconsistent enforcement and oversight of OPM partnerships. This lack also prevents the accumulation of historical data on the quality of OPM arrangements. If schools are not all required to submit a common baseline of information, accreditors cannot monitor patterns and support their institutions interested in working with OPMs.

How Do Accreditors Evaluate Governance Models?

Strong governance has long been seen as a critical factor for ensuring academic quality driven by qualified faculty, and accreditors include an assessment of governance in their accreditation of institutions. Throughout our review, accreditors all emphasized the importance of governance and control in their reviews of OPM contracts, as well.

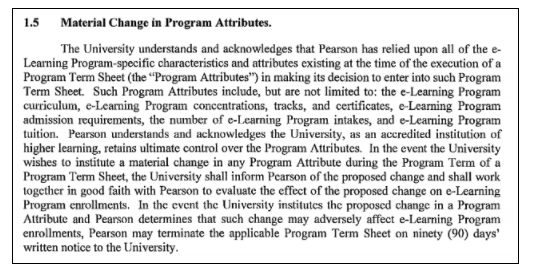

However, it is not clear that those governance standards are always strictly defined or enforced. The Higher Learning Commission (HLC) standards, for instance, specify that contracts with 50 percent or more of responsibility contracted out will not be approved.10 However, in a contract approved by HLC-accredited University of North Dakota, the OPM firm Pearson is responsible for nine of the thirteen services underlying the contracted program, including course design and development and faculty training. From our research, it appears that agencies often defer to colleges in defining how much of a program is being outsourced, or have rules of thumb for calculating the share of a program provided by an external company that leave plenty of room for gray areas or avoided oversight. For instance, the agencies may primarily consider whether the instructors themselves are employed by the college or the company, rather than accounting for all academic functions in totality.

NWCCU was the accreditor of Concordia University, whose large revenue-share agreement with OPM HotChalk contributed to its eventual collapse in February 2020. Concordia’s seeming health—with a steady stream of new students—hid serious financial woes that were partly the result of hundreds of millions of dollars paid to HotChalk.11 In retrospect, the details of the Concordia–HotChalk arrangement are obvious red flags that the institution and its accreditor should have acted upon. The school was locked in an expensive twenty-year contract, the success of which relied on hitting increasingly unrealistic enrollment targets, and the line between the school and the company was eventually unclear to officials in both camps. Concordia’s accreditor, NWCCU, indicated that since the school’s closure, it plans to apply heightened scrutiny of institutions working with OPMs. Among the accreditors we spoke with, NWCCU appeared to require the most information from institutions applying for approval of substantive changes, including information on expenditures, governance, and the financial sustainability of a program.

It seems clear, however, that the scrutiny applied to OPM contracts has not historically been as rigorous. Pearson holds contracts with HLC-accredited University of North Dakota, as well as NWCCU-accredited University of Nevada, Reno; the two contracts look very similar, both giving Pearson large amounts of control over academic responsibility, as well as a steep share of revenue. In University of Nevada, Reno’s 2015 contract, Pearson is responsible for eleven of the thirteen services of the institution’s master of social work program, including faculty training and course development. One provision undermines the academic independence of the institution by stating that the institution must have mutual agreement from Pearson before any concentrations can be added to the program.

Other agencies have seen a similar lack of clarity, and sometimes a disconnect, between their governance standards and how OPM contracts are held to those standards. The Western Association of Schools and Colleges Senior College and University Commission (WSCUC) requires institutions to comply with its Agreements with Unaccredited Entities Policy and Guide, which could include arrangements in which an institution contracts with an OPM for services.12 Within the guide, WSCUC indicates what can and cannot be outsourced and includes guiding principles regarding the role of faculty and staff in creating programs, program elements, and admissions and recruiting. According to WSCUC policy, the agency requires a substantive change review if the OPM will deliver 25–50 percent of the academic program as measured by credit hours or if the OPM will be responsible for assigning student grades and credit. In cases where a substantive change review is required, an institution submits a written explanation of how the arrangement with the OPM complies with WSCUC accreditation standards. NECHE similarly indicates that it looks for clear and ongoing strong oversight, and that written arrangement proposals must specifically note, among other things, who is providing instruction. NECHE may not have a hard and fast preference as to whether the institution provides instruction, but in its document outlining good practices in contractual arrangements, the accreditor does suggest institution-based faculty should “periodically review courses and programs.” NECHE accreditation standards require that institutions “demonstrate clear and ongoing authority and administrative oversight” of the academic programs.13

Accreditors say that they are looking at the distribution of academic responsibility in OPM arrangements, which is good. But it is unclear how the agencies determine whether that distribution is appropriate.

But while it is important that accreditors say they are looking at the distribution of academic responsibility in OPM arrangements, it is unclear how the agencies determine whether that distribution is appropriate. The OPM Trilogy Education Services has contracts—with the WSCUC-accredited University of California, Los Angeles Extension school, and NECHE-accredited University of Connecticut—that give Trilogy the responsibility of hiring instructors. Yet such hiring is a standard responsibility of the college, which helps preserve the institutions’ standard for faculty and rigor of curriculum. This may be why WSCUC’s Agreements with Unaccredited Entities Guide explicitly lists the hiring of instructors as being out of bounds when it comes to outsourcing.

A Better Way to Evaluate OPM Arrangements

Not all university partnerships with OPMs involve comprehensive deals where the third-party company manages most of the functions needed to deliver an online degree. Thus, we agree that accreditors are right to differentially judge written arrangements. However, agencies should consider how risky contractual elements are to institutions and students, and use the overall total risk to apply the right level of scrutiny. Rather than simply taking an institution’s word on how risky a partnership may be, accreditors should examine contracts for inclusion of the elements listed below (color-coded on a spectrum to indicate risk) and use the overall risk level when determining which standards and policies apply.

The image below lists elements that can be found in OPM contracts. The elements are categorized to help the reader consider services an OPM might provide; the number of programs and amount of enrollment the OPM might be involved in; the payment terms, the contract length and how difficult it is for an institution to transition out of the contract; and academic and program governance.

Within each of these categories, the level of risk the institution is exposed to varies depending on each element and thus, on how much involvement the OPM has beyond basic, single-service provision for a flat fee. Under each category, risk runs from low to high, where we argue the presence of one element might present a low amount of risk to the institution, while the inclusion of more than one element increases the total amount of risk. However, a single risky element could also skew the overall risk inherent in the contract to be very high.

For example, for services provided by the OPM, if the third party is providing 100 percent of the services needed to run an online degree program, such a contract would warrant closer scrutiny from the accreditor, even if every other element of the contract might fall on the low end of the risk scale. Likewise, there are traits that should be deal breakers for accreditation. For example, OPM recruitment that accounts for more than 25 percent of an institution’s total enrollment should be a red flag for accreditors. And poor governance practices, such as an OPM having operational control of program resources, should also be prohibited. There are some partnerships where the third party is acting as the institution while escaping any of the regulatory scrutiny the OPM would receive if it functioned as a stand-alone college—for example, if an OPM brings in 100 percent or nearly 100 percent of a school’s enrollment, or if the OPM has a voice in making programmatic decisions. These elements indicate that the OPM and institution are not truly acting as independent entities—a separation that accreditation requires. (We discuss the issue of independence in detail in the following section.) It could be argued that universities simply should not enter contracts with these elements. However, in cases where they are allowed—and indeed, such arrangements do exist today—the accreditor is obligated to go through the proposal in great detail.

| Gauging OPM Risk | |

| Services | |

| Technology provision (i.e., platform access) | |

| Academic or instructional provision (i.e., instructional design) | |

| Marketing and recruiting | |

| Bundle of a few services | |

| Comprehensive bundle of services | |

| 100% of services | |

| Programs Managed | |

| 1-5 programs across multiple departments | |

| 5 or more programs across multiple departments | |

| 5 or more programs within one department | |

| Entire online catalog | |

| Projected Percent of total Institution Enrollment Affected | |

| <10% enrolled via OPM-managed program(s) | |

| 10-25% enrolled via OPM-managed program(s) | |

| >25% enrolled via OPM-managed program(s) | |

| ~100% enrolled via OPM-managed program(s) | |

| Payment Terms | |

| Flat fee-for-service | |

| Revenue share | |

| Fluctuating revenue share | |

| Length of Contract | |

| 1 cohort | |

| 10 years | |

| Indefinite | |

| Captivity | |

| Institution can terminate without penalty | |

| Term hinges on OPM performance | |

| Term hinges on OPM’s business structure | |

| Three months’ notice required | |

| Financial penalties for termination | |

| Six months’ notice required | |

| OPM retains right of first offer | |

| Auto-renewal | |

| Post-contract restrictions on institution and/or programs | |

| Governance | |

| Clearly defined institutional control of admissions standards | |

| Clearly defined institutional control of marketing materials and processes | |

| Institution-based faculty retain ownership of developed courses | |

| Institution-based faculty review and steer program, course, and curriculum | |

| Program development and management fits within existing institutional governance structures | |

| Program governance and decision-making power is unclear | |

| Implied or automatic institutional approval of marketing materials and processes | |

| OPM has operational control or influence over a substantial share of program resources, limiting decision-making ability of formal governance bodies | |

| Contract establishes a steering committee with anticipated participation of the OPM | |

| OPM has voting or decision-making power on program governance questions | |

Incentive Compensation Rules

It is also important for accreditors and institutions alike to consider the ways in which OPM partnerships may conflict or interact with federal laws around incentive compensation. The Department of Education’s primary involvement with OPM companies has been through these incentive compensation rules that prohibit colleges and their contractors from paying recruiters per head for enrolling new students. The department published new guidance affecting OPMs in 2011, following several years of regulatory ping-pong. (The administration of George W. Bush had established “safe harbors” to protect schools from enforcement of the long-standing legal requirements, and the administration of Barack Obama rescinded those provisions and strengthened the rules).

The Department of Education’s 2011 guidance on incentive compensation and other program integrity rules gave institutions some exceptions to the statutory ban on incentive compensation.14 One exception allowed incentive compensation for companies that provided recruiting and marketing practices in addition to an array of other services—a so-called “bundled services provider.” Under the guidance, such providers could charge a percentage of tuition revenue—even though doing so flew in the face of the incentive compensation ban by giving those providers an incentive to maximize enrollment.

While that guidance helped to set the stage for the massive growth of the OPM sector and gave way to many unintended consequences, it was clear on points regarding institutional control over educational functions and enrollment decisions.15 The 2011 guidance placed a premium on the distance of third-party firms from universities’ program design and decision-making (emphasis added):

The independence of the third party (both as a corporate matter and as a decision maker) from the institution that provides the actual teaching and educational services is a significant safeguard against the abuses the Department has seen heretofore. When the institution determines the number of enrollments and hires an unaffiliated third party to provide bundled services that include recruitment, payment based on the amount of tuition generated does not incentivize the recruiting as it does when the recruiter is determining the enrollment numbers and there is essentially no limitation on enrollment.16

Importantly, then, the guidance was only intended to allow universities to contract with companies that would provide recruitment as long as the university maintained control over the governance of the program. For such relationships to be allowable, the educational institution had to remain responsible for setting enrollment targets and making admissions decisions.

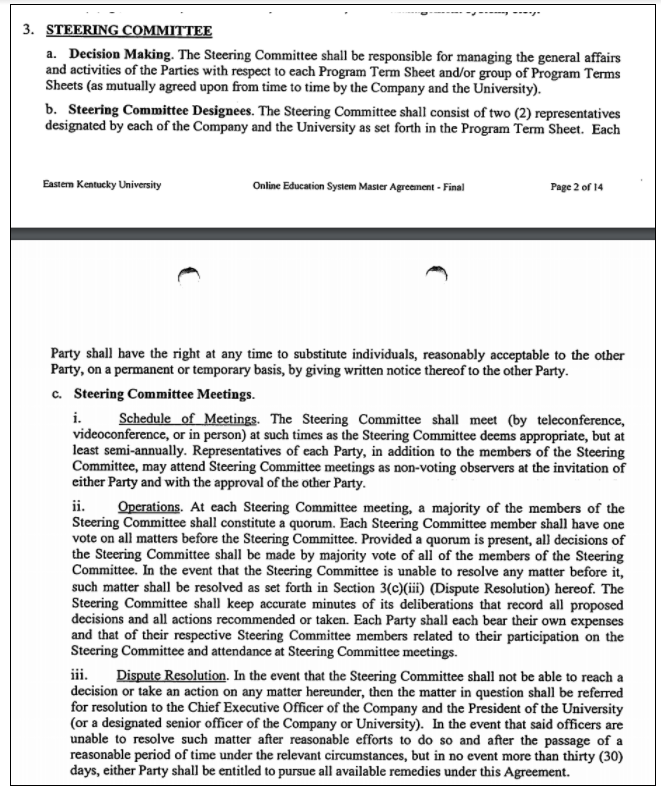

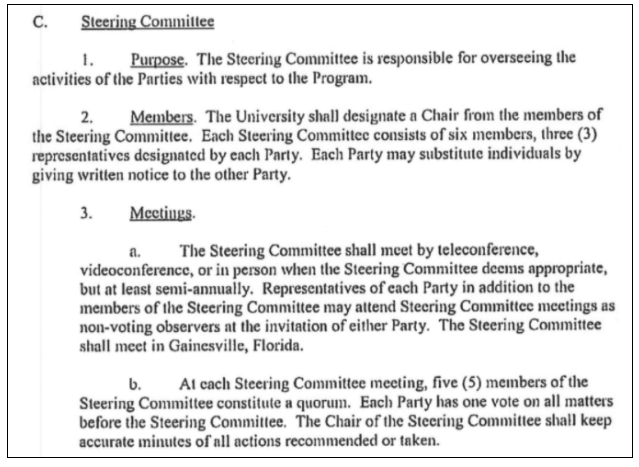

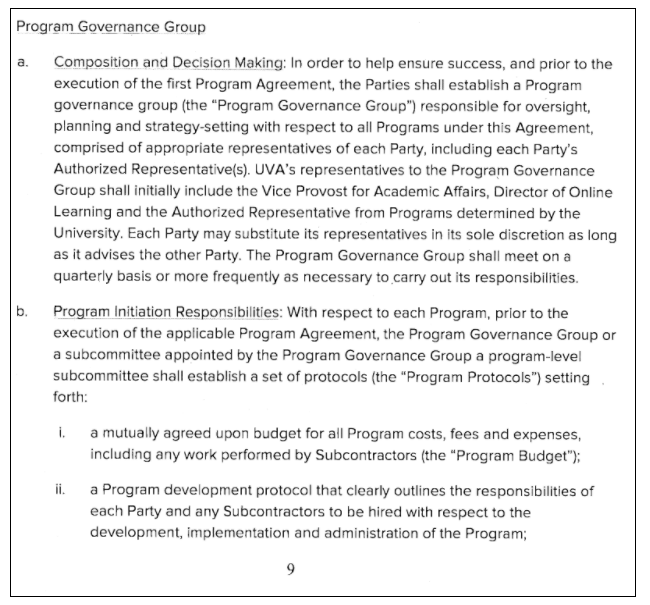

Unfortunately, accreditors and the Department of Education have not ensured that those rules are being followed. We have seen contracts between institutions and OPMs that run quite obviously counter to the spirit of the law and the 2011 guidance. For instance, some contracts establish steering committees through which OPM corporate representatives are given jurisdiction over department, program, course, or content offerings. This is the case at Eastern Kentucky University, where the OPM is governed through a joint steering committee with OPM Pearson; and at the University of Florida, where the OPM is governed through a joint steering committee with OPM All Campus.17 The University of Virginia has a contract with OPM Noodle that establishes a governance group with an explicit charge of jointly making budgetary decisions.18 And the University of North Dakota cannot make curriculum changes to its OPM arrangement without Pearson review.19 Such a degree of deferment to the company, at the expense of the institution, runs against the guidance’s requirement that the OPM be an independent actor without authority over the construction and content of the program.

Unfortunately, accreditors and the Department of Education have not ensured that rules around incentive compensation are being followed.

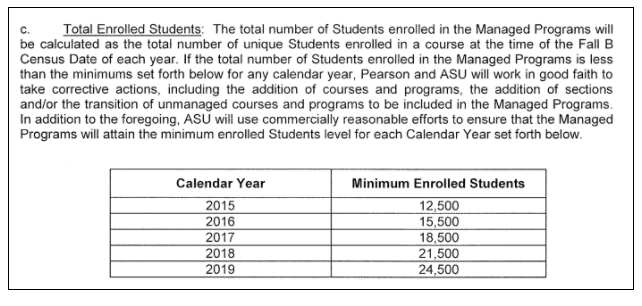

Contracts that include enrollment requirements come with implications that the OPM had a say in determining those targets. Some contracts go even further, to require mutually agreed-upon enrollment goals and academic adjustments to course offerings that ensure the OPM and the institution meet their enrollment goals. For example, Arizona State University’s contract may require the school to add courses or sections, or add new programs to Pearson’s contract, in order to meet mutually set enrollment targets.20 At least one accreditor shared with us that it requires institutions to justify enrollment targets for newly launched programs, and even requires evidence of financial viability if those targets aren’t achieved. All accreditors should follow suit and ensure their institutions’ OPM arrangements meet the requirement for independence in the bundled services guidance by evaluating whether those targets have been determined solely by the institution.

Accreditors are a crucial missing link in oversight with respect to OPMs—the sole party currently obligated to review and approve most individual substantive changes, with expertise in education quality, governance, and fiscal sustainability. Accrediting agencies are well positioned to evaluate the details of these contracts and ensure institutions are not party to deals that run up against or counter to laws and regulations. In fact, as gatekeepers to federal funding, accreditors are obligated to take up this task.

Accreditors’ Laissez-Faire Approach

All the accreditors we spoke to take a largely hands-off approach to partnerships with OPMs. For instance, one accreditor we spoke with stated that rather than serve as a “prescriptive” regulator when it comes to telling colleges how to conduct the due diligence they are expected to perform, it guides institutions through a process that ultimately results in due diligence. Another accreditor also noted that the obligation to protect the institution is solely the college’s, noting that the institutions are “responsible for anything done in their name.” As things stand, the onus is on the college to ensure an OPM meets its accreditor’s standards, while the accreditor may never evaluate the agreements between colleges and OPMs to ensure they uphold these standards.

While accreditors certainly do not have to hold a college’s hand through an arrangement with an OPM, this laissez-faire approach is problematic. First, it leaves institutions largely on their own to research whether an OPM is a quality partner, analyze the contract, and ensure the partnership meets accreditor standards. And as we learned, many accreditors are vague about what information they need to determine an arrangement meets standards, or about how they evaluate the information that is submitted (often the contract, as well as narrative responses to particular questions). Colleges also risk going through extensive negotiations with an OPM, only to find that their partnership will not be approved at the end of it all. Accreditors could support institutions through this process by sharing guidance, data, and lessons learned from other institutions instead of leaving colleges on their own.

The hands-off approach leaves institutions facing a fast-growing industry with minimal support and little oversight. Institutions likely approach an OPM contract with little to no knowledge of the industry and may be susceptible to common traps, like bundled services or profit-sharing agreements. This makes it challenging for institutions to determine whether they will be entering a healthy partnership. Accreditors, on the other hand, have a bird’s-eye view of the industry’s work with higher education. Accreditors could be proactive by collecting data and gathering knowledge about OPMs to both inform accrediting standards and procedures and share them with colleges looking to work with an OPM. One accreditor we interviewed claimed that “we can’t protect [colleges] from bad deals.” But with greater involvement and information, accrediting agencies can and should help institutions identify programs that carry significant financial risk for the institution.

Accreditors have used prior knowledge and experience to protect institutions from poor arrangements with OPMs. NWCCU recently changed its policies regarding third-party agreements after the closure of Concordia, for example, and will be exerting greater oversight moving forward. NWCCU told us that the crisis that led to the closure of Concordia is “a warning sign for other accreditors” to be more proactive when reviewing third-party contracts. Taking a more hands-on approach could help institutions make better decisions and protect their students, and prevent the type of crisis the agency experienced under its watch.

Accreditors are the only entities with direct responsibility for quality assurance at colleges. They are best suited to set high standards for OPM contractual agreements, and to approve or deny them.

Finally, accreditors’ laissez-faire approach to OPMs presents a particular challenge because the federal government and other consumer protection agencies have limited oversight over OPMs. The Department of Education is legally prohibited from weighing in on college quality, pinning the responsibility even more heavily on the accreditor.21 Accreditors are effectively the only entities with direct responsibility for quality assurance at institutions of higher education; they are best suited to individually review OPM arrangements, to set high standards for those contractual agreements, and to approve or deny them.22 As stewards and defenders of institutional quality, accreditors’ “not-my-job” mentality sits in stark contrast to what they stand for and puts colleges, students, and taxpayers at risk.

Recommendations

Increasingly, accreditors are developing an awareness of OPM companies’ role as the shadowy underbelly of the higher education sector. Some are investigating the issue for future consideration, or considering updates to their standards and policies that would result in heightened scrutiny for institutions’ contracts with OPMs. But to date, there has been woefully little investigation into the types of contracts colleges have entered, and virtually no accountability for inappropriate agreements, even when they have gone wrong.

If accreditors are to serve as the defender of institutional quality they purport to be, a first-order requirement is that they ensure the institution is what it says it is, and that its programs live up to the accreditor’s expectations for quality. Having explored the current landscape, we offer a path forward for accrediting agencies that are willing to take up the mantle. These recommendations can—and should—be the basis for heightened review of OPM contracts, greater ongoing monitoring, and new standards and policies that agencies articulate to their approved institutions. While some agencies already engage in some of these practices, we believe all are critical for an effective oversight regime.

More Information, Closer Reviews at the Outset

Most agencies consider the creation of a program spun up by an OPM to be a substantive change, yet still require little more than the submission of an application with open-ended, free-response questions. Institutions craft their responses, and are evaluated largely on their ability to “sell” the arrangement as a viable option to the accrediting agency. Most accrediting agencies we spoke with did not specifically require the submission of data about past programs the OPM has offered or their student success. For instance, one agency’s application for contractual arrangements requests “evidence of the effectiveness” of similar arrangements in which any of the partners have contracted before—but it does not specify what that evidence must include, or what supporting data points must be provided to back up the institution’s response.23 And while agencies may review the contract, it is clear from the nature of many accreditor-approved OPM arrangements that they are not sufficiently assessing whether the contract is reasonable and appropriate. Stricter standards about what is and is not permissible, as well as guidance on areas of major risk to the institution, would better protect the students who ultimately enroll in these programs.

- Collect data relevant to the institution, the provider, and the proposed program and evaluate the past performance. When considering a proposal for a new OPM arrangement, accrediting agencies should require specific, data-driven responses that include: student outcomes of the provider and of the institution (at a minimum, retention rate and completion rate, but preferably also including job placement rates or other employment outcomes); enrollment growth projections for the new arrangement, compared with overall enrollment trends at the institution and in any other online programs offered by the school; and expected tuition of the program relative to the tuition of other online programs in the field of study.Agencies should not assume institutions have fully vetted their partners prior to submitting the application. These data, along with an assessment of the financial, academic, and compliance track record of the OPM, should be used to evaluate the past performance of the OPM as part of the substantive change review. Accreditors should particularly consider past performance given the key players within the OPMs, many of whom come from the for-profit college sector, and their performance in the Title IV space—particularly for programs that will rely on Title IV financial aid access.24 OPMs that are implicated in past compliance issues, have a history of poor student outcomes, or that have led poor-quality or unsustainable programs at other institutions should not be approved to operate programs that may cause further damage.

- Consider marketing materials. Some agencies have explicit language in their substantive change policies about marketing and recruiting practices. A key worry with OPMs controlling these aspects of a partnership with institutions is the potential that they use high-pressure tactics that have been perfected by for-profit colleges.25 This is clearly worrisome from a consumer-student protection standpoint, but institutions and their accreditors should also be self-interested in intervening in this realm because doing so is essential for protecting the school’s brand. Institutions should oversee practices on two fronts: the development of marketing materials—including ad content—and the development, training, and oversight of the recruitment staff. In partnerships where the OPM has been tasked with managing marketing, the contract should make clear who develops content and what the process will be for the institution to approve of content. It is essential that accreditors prohibit language that gives the OPM the power to assume content is approved if they have failed to make contact with institutional representatives or simply because a certain number of days have passed.At least one agency requires its institutions to monitor the behavior of OPM employees who act as field agents in the student recruitment process, and it forbids those employees from using titles like “advisor” or “counselor.” Such policies go far to prevent deceptive or pressurized recruiting by OPMs. Adopting these rules could help to strongly differentiate OPM-run online programs from typical for-profit college programs—so long as they are enforced. Despite the policy being on the books at at least one agency, prominent full-service OPMs still give student recruiters titles like “advisor” and “admissions counselor.” Accreditors should require institutions to approve of materials used for training recruiters and employees at call centers, as well as scripts to those field agents will use. We suggest that all agencies adopt and enforce policies requiring institutions to keep a tight and constant watch over the marketing and recruiting aspects managed by the OPM, and prioritize scrutiny of planning for this supervision.

- Realistically evaluate growth targets. Contracts with OPMs based on revenue sharing are reliant on the company receiving sufficient funds by bringing enough dollars in the door. Yet as more and more institutions offer online programming, it becomes harder and harder for institutions and OPM contractors to make the math work. Enrollment targets may also be manipulated to unreasonable levels in the OPM’s efforts to sell the institution on the arrangement.Accrediting agencies must conduct an independent assessment of the growth targets to evaluate whether they are reasonable and achievable, and whether they will require substantial changes in the institution’s admissions policy to achieve. In doing so, the agency should take into consideration recent efforts by the institution (or by other institutions the accreditor has approved) to operate online programs at the same level; the number of other institutions offering similar programs; how reasonable the targets seem on their face; and the financial implications for the institutions if the targets are not met.

- Pressure-test the governance structure proposed for the program. Most accreditors we spoke with agreed that they are concerned with institutions giving up their independence or financial and academic control. Yet many of the contracts we have seen—even those at institutions accredited by the agencies with which we spoke—include disturbing provisions that would hand the unaccredited provider substantial control over the curricular, academic, and financial decisions for the program.Agencies need to do more to evaluate the independence of the institution under these arrangements. They should not approve formal structures, like steering committees, that give the OPM voting authority or decision-making power over program or course offerings, admissions requirements, enrollment targets, or major curricular decisions—particularly at the expense of faculty at the institution. Moreover, accrediting agencies should require institutions to place deeper thought on the question of independence by requiring them to evaluate how a number of scenarios would play out—most of which are probably not addressed in the contract being submitted for approval. For instance, the agency could ask the institution how it would update a computer science curriculum if a new programming language falls into favor; or how it would address the problem if the institution falls far short of enrollment goals for the program and the OPM wishes to reevaluate the financial terms of the contract.

Continuous Monitoring of Approved OPM Contracts

Importantly, the review of OPM contractual agreements should not stop with their initial approval. While it’s true that institutional accreditors do not typically consider the individual programs of the institution, follow-on monitoring of approved substantive changes should be considered a critical part of the review process and an integral component of the agency’s ability to demonstrate its effectiveness in quality assurance. Moreover, given the risk involved with outsourcing an educational program to an unaccredited provider, continued oversight of OPMs is an essential part of agencies’ strategies to decrease the risk for college students, and ensure quality and opportunity in postsecondary educational offerings.

- Require annual data on the program. Accreditors can’t anticipate problems they cannot see. Regular tracking of programs—ideally, conducted annually— will provide an easy way for accreditors to identify looming problems and react quickly. By collecting key data points, they will be far more able to respond to the risk of collapse or to endemic quality problems, institute protections for students, and initiate a turnaround.

In particular, accrediting agencies should require annual submission of data on the enrollment of each program provided through an OPM (including the difference between actual and projected enrollment and target enrollment, as well as the percentage change in enrollment relative to the previous year); the withdrawal rate, retention rate, and completion rate for the program; and tuition changes in the program. Programs that meet certain risk factors should be flagged for follow-up by the accrediting agency. Such risk factors might include newly operating programs without much track record of performance; programs with substantial growth; programs substantially short of enrollment targets laid out in the contract or the institution’s application for substantive change; programs with high drop-out rates or low retention rates; and programs with quickly increasing tuition.

Policymakers Must Also Step Up

It is not up to accreditors alone to make the changes that are needed to ensure better-functioning relationships with OPMs. There are several steps that policymakers can take to assist—and enforce—reforms.

- Close the loophole for “bundled services” providers. Guidance from the Department of Education, issued in 2011, allows institutions to skirt long-standing rules against incentive compensation practices and agreements, provided they also offer services other than the marketing and recruitment activities that would otherwise fall under the incentive compensation ban. The guidance gave rise to an influx of OPM companies that sell themselves as bundled-services providers, but which entangle colleges in risky contracts that depend on the college making enough money from their online programs to pay a hefty chunk of it to the contractor and still maintain quality. These programs have proven risky in the past, and their revenue-share structure has exacerbated the problem by providing all the wrong incentives for heavy recruitment at any cost and excessive tuition pricing. Moreover, the guidance runs directly counter to the incentive compensation ban lawmakers clearly intended. The administration of Joe Biden should rescind the guidance, and restore the restrictions on incentive compensation practices, to better protect students.

- Increase transparency of OPM contracts. The OPM industry operates largely in the shadows, with little information publicly available about the nature of the contracts, the successes and failures of the program, and the outcomes of the students who graduate from them. Because many of the programs operate in the graduate education space, they are even less subject to public scrutiny than undergraduate programs fully offered by accredited institutions. Regulators (including accreditors) usually don’t sit up and take notice until a stunning story hits the papers—like the permanent collapse of 115-year-old Concordia University, in part because of an unsustainable arrangement with its OPM; or the total loss of federal financial aid eligibility at Morthland College, after its OPM provider pressured the college to greatly lower its admissions standard.26

Greater transparency is urgently needed. The Department of Education should begin to collect information on the existence, and nature, of OPM contracts to inform future oversight efforts. That information should include identifying where programs are in operation; collecting the contracts that are in effect; tracking enrollment and tuition prices in such programs; and assessing the retention, completion, and employment outcomes of their graduates. The department should also track the dates and conditions of accreditors’ approval of these arrangements, and build a review of that decision-making into its regular recognition and monitoring processes for accrediting agencies. - Mandate stronger reviews of OPMs by accrediting agencies. While we hope to see accreditors shift their policies as needed to more thoroughly address all these critical factors, it is likely that Congressional action or regulatory action will be needed to ensure agencies require at least a baseline level of review of these factors. In particular, lawmakers should mandate that the development of online programs in coordination with an unaccredited entity like an OPM firm constitutes the type of substantive change that requires reevaluation by accreditors. Such a mandate would ensure accreditors rigorously review such arrangements. Congress should also ensure that reviews address issues related to finances, governance, and student outcomes, including requiring the substantial consideration of data on actual and projected enrollment; retention, completion, and withdrawal; and tuition pricing trends within each program.

Our review of accrediting agency standards, policies, and practices reveals that, too often, agencies are deferring to institutions’ judgment in establishing OPM partnerships. But our work also reveals that institutions themselves are often rushing head-first into these arrangements, with too little consideration for the appropriate balance of governance, the OPM firm’s history or track record in the space, and the financial and academic viability of the program. And by rubber-stamping these partnerships despite problematic contractual provisions, accrediting agencies are allowing poor-quality programs to persist.

Appendix

FIGURE 1: Eastern Kentucky University’s OPM is governed through a joint steering committee with OPM Pearson.

FIGURE 2: University of Florida’s OPM is governed through a joint steering committee with OPM All Campus.

FIGURE 3: University of Virginia’s contract with OPM Noodle establishes a governance group with an explicit charge of jointly making budgetary decisions.

FIGURE 4: University of North Dakota cannot make curriculum changes to its OPM arrangement without Pearson review.

FIGURE 5: Arizona State University’s contract may require the school to add courses or sections, or add new programs to Pearson’s contract, in order to meet mutually set enrollment targets.

Acknowledgments

New America would like to thank the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation and Arnold Ventures for their generous support of our work. The views expressed in this report are those of its authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the foundations, their officers, or employees.

Notes

- Until 2020, most of the accreditors overseeing public and nonprofit institutions were organized by regions of the United States, and were thus known as “regional accreditors,” while for-profit institutions largely sought accreditation from so-called national accreditors that specialized in a type of institution rather than a geographic region. A 2020 change in regulation eliminated these geographic delineations in federal rules, and some regional agencies are moving to accredit institutions across the country. Even before 2020, though, these were approximate terms; there are, of course, some for-profits that held regional accreditation, and some publics or nonprofits that were nationally accredited. All institutions must be institutionally accredited, whether by a “regional” or “national” accreditor, in order to be eligible for federal financial aid under the Higher Education Act.

- These include HLC, MSCHE, NECHE, NWCCU, SACSCOC, and WSCUC.

- “TCF Analysis of 70+ University-OPM Contracts Reveals Increasing Risks to Students, Public Education,” The Century Foundation, September 12, 2019, https://tcf.org/content/about-tcf/tcf-analysis-70-university-opm-contracts-reveals-increasing-risks-students-public-education/.

- Robert Shireman, “How For-Profits Masquerade as Nonprofit Colleges,” The Century Foundation, October 7, 2020. https://tcf.org/content/report/how-for-profits-masquerade-as-nonprofit-colleges/.

- 34 CFR 602.22(a)(1)(ii)(J) Substantive changes and other reporting requirements.

- “NWCCU Policies: Related Entities,” NWCCU, June 2019, https://www.nwccu.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/Related-Entities-Policy.pdf.

- Concordia University closed in early 2020. See Jeff Manning and Molly Young, “Concordia University’s Online Vision Hid Grim Reality,” The Oregonian, February 28, 2020, https://www.oregonlive.com/education/2020/02/concordia-universitys-online-vision-hid-grim-reality.html.

- “Policy on Contractual Arrangements Involving Courses and Programs,” NECHE, https://www.neche.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/Pp12_Policy_on_Contractual_Arrangements_Involving_Courses_and_Programs.pdf.

- The University of Rhode Island –Academic Partnerships contract and other full contracts between public institutions and OPMs are available for download in the appendix of the following report: Stephanie Hall and Taela Dudley, “Dear Colleges: Take Control of Your Online Programs,” The Century Foundation, September 12, 2019. https://tcf.org/content/report/dear-colleges-take-control-online-courses/.

- “Policy Title: Criteria for Accreditation,” HLC, https://www.hlcommission.org/Policies/criteria-and-core-components.html.

- Manning and Young, “Concordia University’s Vision Hid Grim Reality.”

- “Agreements with Unaccredited Entities Policy and Guide,” WSCUC, https://www.wscuc.org/content/agreements-unaccredited-entities-policy

- “Standards for Accreditation,” NECHE, https://www.neche.org/resources/standards-for-accreditation

- “Implementation of Program Integrity Regulations,” DCL GEN-11-05, U.S. Department of Education, March 17, 2011, https://fsapartners.ed.gov/knowledge-center/library/dear-colleague-letters/2011-03-17/gen-11-05-subject-implementation-program-integrity-regulations.

- Robert Shireman, “The Sketchy Legal Ground for Online Revenue-Sharing,” Inside Higher Ed, October 30, 2019, https://www.insidehighered.com/digital-learning/views/2019/10/30/shaky-legal-ground-revenue-sharing-agreements-student-recruitment.

- U.S. Department of Education, “Implementation of Program Integrity Regulations.”

- See Figures 1 and 2 in the Appendix.

- See Figure 3 in the Appendix.

- See Figure 4 in the Appendix

- See Figure 5 in the Appendix.

- 20 USC 1232a Prohibition against Federal control of education.

- Clare McCann and Amy Laitinen, “The Bermuda Triad: Where Accountability Goes to Die,” New America, November 19, 2019, https://www.newamerica.org/education-policy/reports/bermuda-triad/.

- See HLC publication on substantive change applications, “Programs Offered Through Contractual Arrangements,” https://www.hlcommission.org/Publications/publications-list.html.

- Kevin Carey, “The Creeping Capitalist Takeover of Higher Education,” Highline, April 1, 2019, https://www.huffpost.com/highline/article/capitalist-takeover-college/.

- Stephanie Hall, “The Students Funneled into For-Profit Colleges,” The Century Foundation, May 11, 2021, https://tcf.org/content/report/students-funneled-profit-colleges/.

- Alejandra Acosta, Clare McCann, and Iris Palmer, “Considering an Online Program Management (OPM) Contract: A Guide for Colleges,” New America, September 15, 2020, https://www.newamerica.org/education-policy/reports/considering-online-program-management-opm-contract/.