The arrival of a new administration and a new Congress in 2021 brings with it the promise of a better vision for higher education. For those watching the for-profit college industry, it also brings the hope that students can be better protected from predatory schools. Barack Obama made strides to reign in the excesses of the sector—a sector that contributed to the ballooning of student debt to more than $1 trillion by 2012. However, the administration of Donald Trump undid many of the gains made to protect students from predatory schools. Many analysts expect Joe Biden to right the wrongs of the past four years and pick up where Obama left off.

Predatory colleges cause sustained harm, no matter the regulatory context. If the United States is going to continue to allow colleges that operate for profit, then the federal government needs to truly protect prospective students by creating effective guardrails to shield them from schools with harmful practices. Further, the government needs to give those guardrails constant attention. Regulations must evolve as the market for higher education does: for-profit schools have shown a consistent ability to innovate new abusive practices.

It is not hard to find evidence of bad actors in for-profit higher education and details of the damage they cause. The Century Foundation and other advocates have spent considerable time and resources collecting and analyzing quantitative evidence of these predatory colleges’ bad practices. The numbers are startling: for every tuition dollar it collects, the average for-profit college spends just 29 cents on student instruction, compared with 84 cents at private colleges and $1.42 at public universities.1 Outstanding student loan debt in the United States has now skyrocketed to $1.7 trillion, and students and former students of for-profit colleges likely hold an outsized proportion of that debt— given what we know about how likely they are to hold debt but no degree, and how they fare in the job market even with a credential, compared to their public and nonprofit college counterparts.2 There is no doubt that for-profit college students struggle to repay their loans: the United States’ 697 for-profit colleges enroll just 8 percent of all students, but account for 30 percent of student loan defaults.3

Despite these grim statistics, students still choose to enroll in for-profit colleges. In a society riven by inequality, where a higher education has become more and more essential to career success, for-profit schools advertise an attractive opportunity to get valuable credentials on a flexible schedule. Thus, to fix the situation, it is essential for policymakers to understand not just the scale of the for-profit problem, but why it exists. To answer that question, more qualitative research is necessary.

This report presents some of the personal stories of students who have attended for-profit schools. A qualitative inquiry illuminates and provides context to the facts that quantitative data have already gleaned. Though qualitative research is not generalizable in the way that data on college spending or graduate debt levels are, it still provides crucial context—quantitative information paints only half the picture.

This in-depth, qualitative study of for-profit college student and employee experiences helps us understand the thinking and experiences of the people behind the data. What was it like to attend a school that spends so little on instruction? What was it like to take on those levels of student loan debt? Why did they choose for-profit education over other options? The answers to these questions inform a series of recommendations for policymakers: First, the system of accreditation needs to be fixed so that it is the indication of quality that consumers believe it to be. Second, colleges should be required to invest in their programming—not just in sales. And third, governments must invest in community college and regional public universities to offer better and more flexible options.

The Demand for For-Profit Schools

There is abundant quantitative evidence on the extent of the failure of the for-profit college sector to live up to its promise. Yet the industry continues to thrive, especially during economic downturns. The few qualitative studies on the for-profit college student experience are a promising starting point for understanding how and why predatory for-profit colleges thrive despite their inherent flaws. Past research has shown that students who choose these schools value convenience and a “frictionless” enrollment process over concerns about tuition pricing.4

Many so-called nontraditional students choose for-profit colleges—and many value their experiences there.5 Such students may have had significant life or job experience between completing high school and enrolling in college. They may be financially independent from their own parents, or they may be parents themselves.6 For-profit colleges have cultivated a reputation of innovating better and faster to serve such learners, even with regard to developmental education—though it is unclear whether that reputation stands up to empirical scrutiny.7

Students are drawn to the for-profit college industry by credentialism—the way a college degree signals to employers that a candidate is worthy, as opposed to signaling that the candidate is trained in a particular skill.

Students who enroll in for-profit colleges may be less concerned with building close relationships with faculty or having library access than they are with making a rational choice to increase their marketability. A primary driver of students to the for-profit college industry is credentialism—the way a college degree signals to employers that a candidate is worthy, as opposed to signaling that the candidate is trained in a particular skill. Students who have enrolled in for-profit colleges for these reasons would not have been swayed from their decision by better or more data. They see a credential as insurance against a downward slide, and the choice to gain the credential at a for-profit college may be the result of constraints on other choices.

The social and cultural climate on mainstream university campuses also affects students’ choices about where to enroll, and how they experience college when they do. Racism and class hostility especially contribute to the continued and extreme segregation in the country’s colleges and universities.8 For-profit colleges easily exploit the fact that students of color are effectively excluded from traditional college campuses.9

Still, it is important for researchers to remember that the students who have chosen for-profit colleges do not necessarily see themselves as victims—they have exercised their own agency and made calculated choices based on their own information, contexts, and perceptions.

Before the COVID-19 pandemic, the National Center for Education Statistics predicted that enrollment in higher education would grow for the foreseeable future. During the pandemic, however, enrollment has fallen across all of higher ed—with the exception of for-profit colleges and online public graduate programs.10 These exceptions could be a function of aggressive student recruitment strategies, the economic crisis, or a combination of factors. Whatever the cause, it appears that for-profit schools, despite their flaws, are today offering students an educational product with enduring appeal. Whether the schools deliver on their promises or not, understanding how students perceive their choices and experiences can help both the public and private sectors improve how they serve students, and help policymakers work more effectively at protecting students and prospective students.

I recruited thirty-six students and employees to participate in confidential, in-depth interviews about their experience in the sector. I wanted to find the answer to some crucial questions: What is the experience of students as they make the choice to enroll in a for-profit college? What is their experience while enrolled?11

Recruiting through the Pain Funnel

One of the most notorious aspects of for-profit higher education has been its aggressive recruitment strategies. In the past, critics have accused those strategies of drawing in students who could not complete programs and were left with huge debts. While many schools have disavowed some of the most infamous methods, recruiters still operate more like salespeople than advisers.

A for-profit college industry analyst noted in January 2021 that enrollments were down over the last decade because the sector had been forced to shift away from aggressive student recruitment strategies, thanks to a 2011 ban on paying commission to employees that recruit and enroll students. Prior to this ban, prospective students who encountered recruiters from the sector were likely to find themselves in intrusive, pressurized conversations meant to lead directly to signing up for classes and student loans.

The investigation showed that ITT Technical Institute wanted its recruiters to draw out the most painful details of prospects’ lives—and create the sense that there was no alternative but to enroll.

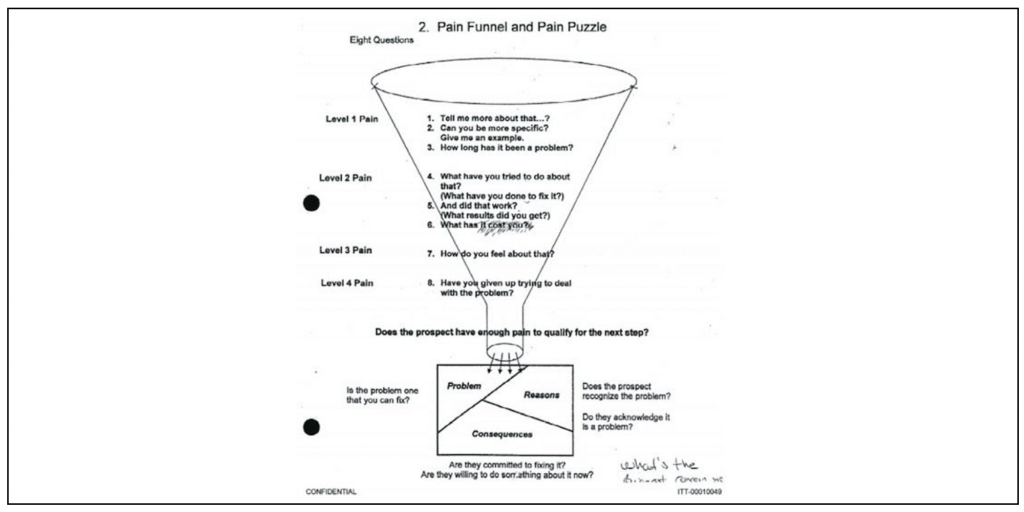

A 2010–12 investigation by the United States Senate Committee on Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions (HELP) revealed training manuals and documents pointing to exactly how for-profit college recruiters were meant to conduct those conversations.12 Perhaps the most impressive piece of evidence to come from the investigation was proof that ITT Technical Institute (which is now defunct) wanted its recruiters to press on prospects’ pain points, to draw out details of their lives that would leave the would-be student with the sense that there was no alternative but to enroll. The idea was illustrated in a diagram called the “pain funnel and pain puzzle,” which shows a recruiter how to work through a set of questions meant to draw out progressively more painful details.

Similarly, a pain-inducing sales technique used by Kaplan University (now known as Purdue University Global) was known to Kaplan employees as the “artichoke” method. It involved peeling back painful psychological “layers” to create a sense of urgency for the prospect to sign up, get a degree, and presumably become a better provider for his or her family. When presented with evidence of these techniques in the HELP inquiry, both ITT and Kaplan distanced themselves from the documents by insisting they were not officially sanctioned materials. In the case of Kaplan, the company claimed the document had only been used by one manager at one location, without authorization from the company.13

Ten years on, the legacy of the pain funnel persists. Once employees or managers have been trained to recruit or sell in a particular way and find success—success according to the metrics they believe their job performance will be judged on—there is a risk of continued use of those strategies. Measures to curb hard-sell and other abusive practices could include internal and external secret shopping programs, and constant surveillance and review of employee practices. At the heart of the issue is the fact that for-profit colleges have an incentive to generate profit. Constant, intrusive, and costly surveillance is likely the only way to allow them to generate profit without damaging students’ academic, career, and financial futures.

Today, companies may not use overt training materials like the pain funnel, but employees I interviewed felt there was an unspoken pressure built into their jobs. The incentives and goals remain the same, even if executives and managers have had to adjust the materials and language they use in response to the damning Senate investigation.

What is clear is that despite the findings of the 2011 investigation, the for-profit college recruitment process hasn’t evolved to mirror public and nonprofit college admissions counseling, though employee job titles might suggest otherwise. A July 2020 Facebook ad for the online for-profit Walden University (pictured below) invites prospective students to speak to an “enrollment specialist”:

And at Ashford (an online for-profit school that was acquired by the University of Arizona last year) a prospect might think they are speaking with an “Advisor.”

Despite these titles, the individuals employed to recruit students at for-profit colleges—and those employed to recruit students for some online programs offered by public colleges—are more likely to come from a sales background than from student affairs. Often, the only role they are capable of or permitted to perform is signing up new students. They are unable to offer other support that might be expected of an “adviser”—such as academic counselling, realistic discussions about financial aid, or career planning.

Franky, a Walden recruiter, explained to me that she is unable to counsel students and keep in touch with them through the admissions and enrollment processes. Recruiters, she said, needed to hand students off to other departments for good as quickly as possible. From her experience working for Walden, Franky has learned how to identify which prospective students are more likely to commit, and are thus worth her time and effort. When she is in conversations with prospects, for example, she has learned that if they ask about financial aid, they will enroll.

Franky was trained to find out a prospect’s motivations, background, and financial situation. She described her work environment as high-pressure, which she said made it impossible to be a true adviser or counselor. In mainstream universities, a student might have contact with an admissions representative even after enrolling, but that is not the case at Walden, nor at most for-profit colleges. Franky explained that she didn’t feel equipped to keep students from withdrawing in their first week of classes, because of the constant need to call new prospects—though she said she has been held responsible for students she has recruited that dropped out very quickly or decided to defer. Franky felt enormous relief when those weekly milestones passed and she could focus on her primary task, recruiting new students.14

Betsy, a recruiter for the for-profit American InterContinental University (AIU), also shared details of her job that were reminiscent of pre-2011 practices.

“A lot of times [students] need motivation. They’re scared. And for example, I had a student yesterday who has been thinking about school for a long time, but she’s been nervous, and she’s been scared [about] going back to school. She went to school about seven years ago, but did not have a good experience in college, so that kind of left a bad taste in her mouth. She realizes that she wants to do so much more with her life, and she needs education. We had a really good conversation, and she was really impressed with AIU…. It’s conversations that make a difference with admissions…. A lot of times, I’m talking with parents who may be working or not working. I kind of take that in, and I let them know how they can still go about their days and take care of the kids. And let’s say when the kids are napping, jump online at that time and get some schoolwork done… [I] have them really think about the big picture of how they want to get to a certain place and [how] they need to make changes now to get there.”15

The Spread of For-Profit Sales Techniques

For-profit colleges are not the only schools that use recruiters. Public universities also contract with third-party online program management (OPM) companies.16 My interviews showed that, while there was variation depending on the firm, these OPMs operate much like a for-profit college call center. Employees and former employees of three OPMs (2U, Pearson, and Everspring) shared their perceptions of a typical workday. A former Everspring employee left the company because she had expected her role to involve more student support and actual advising. Instead, she had to focus on calling a certain number of prospective students each shift—though she did say that Everspring’s call centers seemed to be lower pressure than other OPMs’, according to colleagues’ experiences at other companies.17 Similarly, a former Pearson OPM employee said her performance was measured based on the number of calls she was able to make, though she emphasized that the company also checked her call content.18 A recruiter at 2U had an experience that was reminiscent of the pain funnel. A manager instructed her to tell prospective students, “If you really want to go through this program, you’ll make a way—you might stretch yourself a little bit as far as finances go, but if it’s really important, you make a way.”19

But at least for some OPMs, recruiters have other targets besides the sheer volume of students they sign up. The 2U recruiter said that she was also responsible for recruiting prospects who were a good fit for the program—not merely eligible to enroll.20 For this reason, prospective students inquiring about OPM-run degree programs housed at public universities may have an additional safeguard that their for-profit college counterparts do not. OPM-managed programs have the benefit of using the brand and reputation of their respected public or nonprofit university partner, so it may take less pressure to recruit a student. Despite the ease with which they can recruit new students, OPM recruiters are theoretically incentivized to avoid advancing everyone who shows interest through the application process, because the OPM-managed degree programs pose reputational and financial risks to both the OPM and the host university. OPM-run degree programs housed at public and nonprofit universities need successful students, because those student outcomes impact accreditation and approvals—issues with financial implications for the schools, and therefore for the OPM.

The recruiter had specific instructions about what to tell prospects: “If you really want to go through this program, you’ll make a way—you might stretch yourself a little bit as far as finances go, but if it’s really important, you make a way.”

Student descriptions of the for-profit college recruitment process ran the gamut from “transactional” to “salesy” to deeply personal to overly intrusive. In all cases, enrolling was generally described as very easy. One interviewee understood and accepted the situation: “They want your money, so they make it as easy as possible.”

Multiple students described the barrage of phone calls that are common in the for-profit and OPM-run program recruitment strategy. A student at Ashford University estimated he received “more than ten” calls within a week of indicating interest in the school, and that the calls tapered off after the admissions process was complete. The volume of calls “was almost kind of irritating,” he said.

“It was just a lot of follow-up to say: ‘Oh did you do this? Oh, did you do that?’ And I was like, ‘Let me get to it, I’m gonna get to it. I just need to make sure I get off work first,’ and stuff along those lines. So it’s more like they were trying to pester you. Almost as if they were trying to do a sale—which I understand, you know, that that’s their job. I wasn’t really mad at them per se. I just found it unnecessary.”21

Many interactions with recruiters begin shortly after prospects interact with a so-called lead generator website. Another Ashford student described an onslaught of emails and calls she received after she supplied her information on a website that she thought would help her see if she qualified for grants.22 The site was likely a lead generator—more sales bait than student resource. Many of the most deceptive lead generator websites have been shut down in the past ten years, but advocates would be wise to continue to monitor for the appearance of new ones. The Federal Trade Commission was notified at least twice last year of lead generator sites posing as college ranking sites and sites that appear to match prospects with the best college for their interests.23

Darlene, a student at Colorado Technical University, a for-profit school, described the same phenomenon of phone call and email overload—and how struck she was with the radio silence once she hit a financial wall. Later, when she had drawn down all her available financial aid and had no personal means to pay for remaining credits and fees, the school refused to get in touch with her by phone. When I spoke with Darlene in August of 2020, the school wanted her to sign an agreement to pay nearly $300 a month or be locked out of the program.24 At the end of 2020, Darlene was $90,000 in debt and seven classes away from finishing, with no feasible plan for doing so.

At the end of 2020, Darlene was $90,000 in debt and seven classes away from finishing, with no feasible plan for doing so.

A student at Walden University described the recruitment process as creating a false sense of urgency. An enrollment specialist, she said, had told her that she needed to “sign up today because classes are filling up.” Once she enrolled and entered classes, she realized this was a lie. Classes had space and they were always being offered. In fact, she had the impression that “they would sign up anybody.”25

Sometimes, students have a positive experience of the recruitment process. But the experiences that follow can be a rude awakening. Leah, a student at Ashford, described the constant contact that took place over a week with one recruiter who organized her documents for her. At a community college she had attended earlier in her life, she said, she had to “go all over campus–you had to go to this office and then had to take this paper to this office.” Her experience enrolling at Ashford was the opposite. Had the enrollment process taken longer, she said, she might have changed her mind or hesitated.26 Preventing a prospect from cooling to the idea of enrolling is no doubt part of the strategy in college recruitment call centers.

College Choice Criteria

While prospective students might be unknowingly subjected to the pain funnel or its newest iterations, they still come to the process with certain criteria in mind for deciding among their options. In explaining their choices, students emphasized their perceptions of cost and quality.

A Calculated Expense

Most students said that, before enrolling, their perception of their selected school’s tuition rates was either that the price was to be expected, or that they assumed the price for not attending college would be higher in the long run. It seems that pervasive rhetoric around exorbitant college costs has normalized the idea of paying a lot and taking on a lot of debt.

Teresa, a student at the for-profit university DeVry, said her tuition was about what she expected—even though she had not compared tuition prices across multiple schools. And even if the price was high, she assumed that getting a BA instead of an associate degree (which she could have received at a low cost from a community college) would make the price worth it, because she would end up with a better-paying job.27

Steve, an MBA student at AIU, was paying $3,600 per course. His impression of all MBA programs was that they were expensive, but likely worth it. Even so, he was worried that taking on debt for the AIU degree would be a choice he might end up regretting.28

Kaiya, a Walden student studying for her MSW (master of social work), described the school as “extremely affordable if you know what you’re doing.” Kaiya was a long-term Walden student; she had already completed a BA and an MPH (master of public health) at the school. She returned for an MSW because she didn’t feel she was getting the financial and career returns she wanted from her other degrees. She figured that the MSW would run her around $20,000. She described herself as financially literate, and said that she knew to reject maximum loan amounts. She wanted the MSW for the credential, not because she thought she needed the skills—she was already doing MSW-worthy work, she said, and wanted her pay to reflect that.29

Kaiya said she felt she might have had an easier time if she had gone the “traditional route,” as she put it, and attended a mainstream college. She knew, for example, that her state’s top public institution, the University of Maryland, had an MPH/MSW dual degree option. She described the University of Maryland and Johns Hopkins (which also has an MPH/MSW program) as “notable” schools. Kaiya would have liked the opportunity to study at either of those well-known schools, but the “needs in her life at the time”—including “needing it to be less expensive”—demanded she go a nontraditional route. She felt secure in her choice and believed she could still enjoy career and financial success with her Walden degree.30

Of course, feelings can change about these costs—and often do. As the years go on and debts mount, many students end up ruing the high prices, especially if they don’t experience the career or salary payoff they expected.

Sofia went into $60,000 of debt for what she called a “useless” Ashford University degree. The entire time she was studying, she thought she was on a path to becoming a social worker. Once she graduated, she could tell that employers did not recognize the degree. Only then did she learn that the degree she earned didn’t include a clinical requirement, and was really just a liberal arts degree in social science. During the admissions process and her entire course of study, Sofia never received counseling about her degree’s true career prospects, though she tried her best to inform herself. Most social services agencies Sofia applied to offered salaries around $19,000 a year, for jobs she could get without the degree.

Later, more serious problems in Sofia’s life came to overshadow the debt: she developed multiple sclerosis and other health problems. She became too disabled to work, which led to her loans being discharged—an outcome that is far from assured even in cases of severe disability.31 Camila, a Colorado Technical University student in a similar situation, said it was “a blessing” that she had become disabled, because it gave her an easier route to wiping out $160,000 of debt she had taken on for a BA in health management.32

The Flexibility of Online Learning

For most students I talked to, having the option to study online was a primary factor in their decision-making process. They wanted the flexibility that online colleges promised, because no other aspect of their lives was flexible. Aaron, a student at the online for-profit Independence University, compared his experience studying online to experiences with hybrid learning (where some coursework was completed online and some in person). Before starting an IT degree, Aaron had taken classes in a hybrid format from Strayer University, another for-profit school. He struggled to get to campus on time, which made it one of the most stressful periods of his life. Time pressures from commuting and other responsibilities are a strong incentive for many students to choose online programs.

One Ashford University student, Leah, hoped to balance work and raising her children, so she saw enrolling online as the only viable option. She enrolled at Ashford while working as a home health aide. She had to be at her first client’s house at six o’clock in the morning, so she did her coursework at three-thirty or four o’clock in the morning. “I mean, it was some work, but I was able to get it done,” she said. “I could do my work when I needed to. I didn’t have to be anywhere for any specific time in that sense.” But although Leah eventually earned a BA and an MA in Psychology, she can now only find work as a substitute teacher. She does not feel that the degrees have led to the career shift she hoped for.33

The Lure of Accreditation

Every student I interviewed mentioned that college accreditation was a factor in their enrollment choices. The universality of this factor in their choices came as some surprise to me: some who had little generational or personal knowledge and experience with higher education knew the word “accreditation” and knew to look for colleges that were accredited. As one student put it: “I chose that school because they were accredited in all the right places.”34 Students believe accreditation is a signal that a school should be trusted. What students don’t know, however, is that the current accreditation regime in the United States does not guarantee quality or value.

Students believe accreditation is a signal that a school should be trusted. What they don’t know is that the current accreditation regime does not guarantee quality or value.

Dakota, a busy mom who was motivated to get her MPA (master of public administration) as much for the potential pay raise as for the desire to show her kids that she could do it, spent her entire professional career working in admissions and administration for a public university in California. Even with her experience in the sector, however, Dakota was taken in by the promise of accreditation, and felt secure when deciding between the three colleges she had narrowed her search down to, because they were all accredited: American Public University (APU), Ashford, and the University of Phoenix. In the end, Dakota chose APU because it was “the least expensive, accredited, 100 percent online program.” Because accreditation is pushed as a seal of approval, and because Dakota had her own insider’s perspective of college admissions, she chose not to even speak with the APU recruiters on the phone. Since both her employer and APU were similarly accredited, she assumed they had the “same” admissions processes, and that applications would be carefully vetted.

Dakota’s story shows how accreditation is an effective selling point, which explains why colleges sometimes mention their accreditors in advertisements. Recruiters also know accreditation is valuable. A recruiter working for an online program management company on behalf of a public university said that she points out to prospects that the online degrees are from the “same university with the same accreditation.”35

Colleges rely on the use of external signals of quality. This strategy works to the schools’ benefit as long as the public remains unaware of the problems with contemporary accreditation practices. In the end, Dakota’s primary complaint about her experience at APU was with the library services. Despite being in a graduate program where reading research was essential, she was never able to figure out how to access the library. She worked around this problem by using the resources at her workplace.36

A common theme I heard from students who had been out of school for a decade or more was that they struggled to correctly access online coursework and supplementary materials. This is a serious shortcoming. APU and other online for-profit schools sell themselves as meeting the needs of working adults: they should ensure they have ample assistance available to support students no matter how digitally proficient they are—or schools should require some minimum proficiency to avoid enrolling students they cannot support. Accreditors already examine the finances, operations, academic programs, and student outcomes of their member institutions. A more effective evaluation would involve closer scrutiny of the digital resources and student support services in use by online and primarily online institutions.

Legitimacy from Perceived Association

Quality and legitimacy can also be signaled by association. Students often said that they looked into schools that came to them through some trusted referral route. For example, according to one informant, the Texas Workforce Commission hosted a career fair that DeVry University attended.37 No doubt multiple prospective students ended up on DeVry’s call list as a result of the event. Likewise, employer lists of approved schools where people can use their tuition benefits are powerful, and misleading, signals of approval. Aaron, the IT student at Independence University, found the school’s name on the list of schools where his employer—Apple—would provide tuition reimbursement. In his view, that meant Apple recommended Independence University.38

Perceived alliances with the military also give prospective students a sense of trust. Rebecca, who describes herself as an “eighteen-year military brat,” found DeVry because of the Texas Workforce Commission event. She believed DeVry had a special relationship with the military because of her perception that many active and former service members attend the institution. This perception further supported her feeling that she had fully vetted the school. “I appreciated that DeVry works with the ex-military a lot,” she said. “I really have loved the fact that my professors seemed like they know how to deal with military people. I really appreciated that.”39

Students enrolled at APU also believed it to be a “military school” because it has a sister for-profit school called American Military University. (Both are owned by the firm American Public Education). Despite their names, neither of these institutions is associated with the public sector or the military. Yet multiple students said they perceived APU to be associated with the public sector, or at the very least not associated with the for-profit sector, thanks to its name. In fact, most students I spoke to for this report said that whether a school was for-profit or not was not a main factor in their choices—except for those students attending APU, who believed they had avoided the for-profit sector altogether.

Targeted Ads on the Unequal Internet

Colleges, like all advertisers, have wielded the power of the Internet to their advantage. Colleges embed ads into social media and search platforms. Increasingly personalized advertising algorithms have allowed colleges to zero in on likely prospects. Almost all the students I spoke with said they felt that they were proficient at researching their choices. They independently collected information and trusted their own process. The problem is that the Internet you see, and the ads you receive, are the result of hundreds of factors including personal characteristics like your age, race, and income level, as well as your search and browser histories.40 These characteristics also affect where and how likely or unlikely you are to check the information you find against other sources offline.

Dorothy, an APU student, was unsure about how she learned about the school, but said she thought she found them while “doing Internet research.” APU appealed to her, she said, because it seemed she could sign up for classes in a straightforward manner, similarly to shopping online. She filled out a lead generation form that led to the school calling her within a few minutes. She was enrolled and taking classes within two months. Interestingly, Dorothy was put off by the University of Phoenix’s and Grand Canyon University’s lead generation forms because the schools would not allow her to see information about the school or program before she filled out the forms. This seemed less trustworthy to her than filling out APU’s form.

Dorothy had reason to be cautious—twenty years earlier she had handed over her Pell Grants and taken out loans to attend what she came to regard as a scam business school. She grew leery of college in general—“scared to even try to get my feet wet again.” When she decided she was ready to try again, she only searched for online programs. Even though her local community college or regional public university might have had some online options, her Internet research (which she considered thorough) led her to APU, likely because the school takes up more ad space than her local colleges. She looked at Better Business Bureau and Facebook reviews of APU. As she put it, “I did my homework before I enrolled, and they seemed above board.”41

Dorothy’s local community college or regional public university might have had some cheaper online options. But she chose the for-profit APU—likely because the school takes up more Internet ad space than her local colleges.

Lead generator sites like the one that Dorothy used also employ misleading tactics to acquire prospective students’ details. Some disguise themselves as college ranking sites. A site may seem to offer a list of colleges tailored to a prospect’s personal profile and interests; instead, it shows a list of colleges that paid to appear on the list. Completing questionnaires on such sites, users can unwittingly hand their contact information over to college sales reps posing as recruiters. A student at APU, for example, had filled out what she believed was an aptitude test that would link her to colleges that earnestly matched her interests and current education level. Instead, she was filling in a lead generation form and ended up receiving calls from many schools.

The Sham of Serving Working Adults

For-profit colleges have perfected their ability to recruit working adults, and in particular nontraditional students. They also bill themselves as having perfected the way to serve these students. But some of the students I spoke to reported that the schools don’t live up to this promise. It could be that there simply isn’t a technological fix for the fact that some nontraditional students who want to attend college will also need to work full-time. While student experience is reliant on many factors, and some working adults enjoy studying in their off hours, it is clear that working adults who land in compressed, online programs should temper their expectations for a fulfilling or positive experience. Blue-collar workers, in particular, may find that the programs fail to meet their needs.

Ann, an unemployed nurse in the New York City area, found it difficult to keep up with the workload in her compressed Walden health informatics certificate program, even as a full-time student without a job. The program would be feasible for a working adult, Ann said, only if the student had no other responsibilities and never got sick. She felt Walden should have been more forthcoming about the workload and time commitment the program demands.42 Similarly, Ronald, a construction worker who enrolled at Ashford hoping a degree would help him make a career change, struggled to keep up because his day job was physically and mentally exhausting. Even though Ashford sold itself as being the solution for people in his exact situation, he eventually dropped out. “Life gets in the way,” he said.43

Mariah, who earned a certificate and three degrees over the past decade at AIU, said she felt like they were just expensive pieces of paper. Mariah lives in a part of the rural South that is chronically economically depressed, and she kept hoping that additional credentials would improve her situation. She found the compressed six-week course structure to be grueling, though she kept returning for more. “There is no way to learn everything in six weeks,” she said. The school’s promotion of itself as being perfect for working adults was a sham, she added. Beyond the problems with the compressed schedule, Mariah also lamented AIU’s ineffective job fairs. When she enrolled, she was promised that she would get the chance to speak with government agencies and nongovernmental organizations, but at every job fair event she attended, most employers were from lower-end service sectors, like fast food restaurants. Mariah is currently stuck in call center jobs with pay that tops out around $8 an hour. Her original $100,000 in student loans has ballooned to $180,000.

Mariah, who attended AIU, is currently stuck in call center jobs with pay that tops out around $8 an hour. Her original $100,000 in student loans has ballooned to $180,000.

At the end of the day, if a student is spread too thin between work and studying, neither a compressed schedule nor an on-demand learning platform will make up for the structural deficiencies inherent in the lives of the impoverished rural working class.

Alisha is a young widow with three children in rural Indiana, where the opioid epidemic hit very close to home. Many of her friends in town had dealt with that scourge, as well as the effects of trauma associated with serving in military combat zones. Alisha was so sought after for informal counselling that her friends jokingly called her the “Dr. Phil” of their town. She decided she wanted to go to college to learn how to properly counsel people in need. She opted to study full-time at APU while also taking care of her children full-time, because she believed from the APU’s advertisements that the school was set up to serve students like herself. It proved to be far too much: Alisha would fall asleep trying to do the coursework after her children went to bed; she “overwhelmed” herself. She withdrew, with just a few credits but $10,000 in debt. With an inheritance, she managed to pay the loans off, but knows that without that windfall, her debt would have likely ballooned to an unmanageable amount. Alisha has set up college savings accounts for her children, but would prefer that they look at trade school or certifications before using the money to “go away” to college. Other students I spoke to who had negative experiences as nontraditional students, or who were put off by the amount of debt they took on, said they planned to counsel their own children and grandchildren away from college altogether.

The aspects of online programs that are marketed to nontraditional working adults may not be living up to the hype. Compressed schedules in which a student completes a three-credit-hour course in six weeks as opposed to the traditional ten-week quarter or fifteen-week semester are great for students who want to get through an entire degree program quickly. However, for busy working adults, a compressed schedule can make it hard to keep up, especially if an emergency arises. It is difficult or impossible to take a break from the course, which might be necessary for students with their own families. Students who had studied under compressed schedules described scenarios where upcoming courses and electives were chosen on their behalf; it was easy, they said, to miss deadlines for notifying the administration of plans to take a break or desires to switch into a different course.

Working adults who have some college but no degree also may have special needs if they have not taken classes for years or decades, and may be less comfortable with the online learning environment

As one student put it, working adults who aim to complete a degree online feel more pressure to make it work, and policymakers and prospective students should remember that asynchronous, online study takes more discipline than on-campus learning. These realities underscore how important it is to find solutions for serving working adults.

Better Support for Working Students

Colleges that claim to specialize in supporting working students seem to be falling short of doing so. However, there are two specific areas students cited that institutions could immediately fix. One is to increase the opportunities for students to interact with instructors. A second is to create and sustain partnerships with employers in which education and health students can complete required in-field and clinical internships.

As noted above, students experienced a huge gap between the level of pre- and post-enrollment interaction and engagement.44 But nontraditional, working adult students crave instructor interaction. One student had such difficulty contacting his instructors that he eventually assumed they weren’t paid enough to do their jobs. Indeed, students can suss out the flawed business model of using a completely part-time teaching staff (which is the case at most for-profits).

Likewise, students who appreciate asynchronous options and flexibility still desire some opportunities for live interaction. Students at AIU and DeVry complained that professors didn’t offer live sessions. Rebecca, the Texas-based DeVry student, grew upset that her instructors were not required to host lecture sessions. “They wanted to teach through emails and discussion board forums, and I absolutely hated those—they were miserable classes,” she said. “It’s like, what are we paying DeVry for if I have to teach myself the subject?”45

Online students described working in isolation. Multiple students said that connections between students were as rare as connections with faculty. Danielle, a Colorado Technical University student, highlighted how the isolation made studying online doubly difficult:

“I don’t have a study buddy and I don’t have a classmate that I can ask questions of and, you know, get input from. We all had a CTU email, and you could send email through that to another student. But, you know, then you’re dependent on, are they going to answer it…. You couldn’t go to the library or something and sit down someplace like a student union. It’s nice to sit down and go, ‘Okay, look here’s three or four of us. Let’s throw out some ideas. Let’s ask some questions. Let’s get this straight in our head and help each other. If you have grasped this concept help me get it’.… That was missing. I really think that’s an important part of the college experience because it helps prepare you for the job market. Because once you get into an actual job and a career, you have to know how to do that.”46

A key benefit of going to college is supposed to be the formation of a professional and social network. Yet online students are not often given that opportunity, and there is seemingly little effort on the part of schools to recreate that benefit in the distance education format. Students who opt to study online do so out of necessity and a hope that they will get the same benefit as if they studied on campus. Schools have an obligation to make the degree as beneficial as possible, even if taken in the online format.

A key benefit of going to college is supposed to be the formation of a professional and social network. Yet online students are not often given that opportunity.

Students also complained about difficulties in securing clinical placements. Many health care and education programs require students to complete a clinical or field placement to get practical, supervised training. Students who opt to study in an on-campus program are likely to find it has long-standing relationships with local hospitals, schools, and other relevant worksites. These relationships are key not only for getting students placements in the field (which are often required to graduate), but also for helping the future graduate establish a relationship with an employer. However, online students are not always afforded the convenience of plugging in to such a network of relationships. In fact, some for-profit online colleges that offer degree programs that require a clinical experience do not even maintain a network of relationships or a structure to assist students in securing placements.

Ann, the New York-based nurse who was studying for a health informatics certificate at Walden, struggled to get a clinical placement, despite her own experience working in health care. She said she and classmates were left completely alone to find placements. She tried finding relevant people on LinkedIn and reached out to former coworkers and the hospital closest to her home. In all cases, she was either turned down or ignored. When she realized she was not going to find a placement on her own, she complained to the school. Walden helped her find a spot, but also made it clear that it was not the school’s responsibility.

“It got really hairy at the end because I wasn’t going to finish the certificate, because I couldn’t find anything. So when I did complain to them, then they helped me. I feel like they should be helping anyway, because even in my job, I’ve had people reach out to me from other programs to ask me if they can complete their clinical placements with me, and I wasn’t permitted to. So I know people aren’t finding placements. It’s like they built you this program and then they get you to the end and are like, ‘Okay, well, good luck finding something.’ That’s horrible.”47

Ann’s impression was that her problem was common, and that many students at Walden couldn’t finish their certificates or degrees because they were unable to secure their own placements. In Ann’s case, when she initially looked into attending Walden, her other most viable option was an in-person program at nearby NYU. She knew she would have had a better placement experience there, but she chose Walden because it was cheaper. She was willing to take the gamble on the quality of her clinical placement, not to mention her eventual job prospects.

Another Walden University student, Claire, was unable to finish a nursing degree because she couldn’t secure a clinical placement. She was already working in the nursing field, but needed to find another, similar placement and professional to work under for the experience to count. When Walden did not offer help in placing her, it seemed the degree would be impossible to finish, and she dropped out. Claire was shocked that no one at Walden reached out to ask her why she didn’t finish.48

Colleges can improve the way they serve adult students by ensuring their students are wanted and valued at clinical sites around the country. Offering degrees online is no excuse for failing to assist students with clinical and field placements. In fact, programs with clinical requirements should be assessed on their ability to get students placed in sites that offer high-quality training. If employers are willing to take an institution’s students, this could signal job market value for its training and programs.

Recommendations

The colleges attended by the students I spoke with exist and operate the way they do because of social inequalities. As long as social inequalities persist, so will predatory colleges. Such colleges benefit from the fact that it takes generations to remove information asymmetries regarding higher education. Prospective students who are the first or second generation in their families to attend college are at a significant disadvantage when they parse information to choose a college—especially given the unequal nature of high schools, the Internet, and the distribution of income in the United States. Tressie McMillan Cottom summarizes the situation well in her 2017 book Lower Ed, a study of for-profit colleges: “All roads of inequality—families, schools, income, wealth, class, gender, and race—run through the conundrum of popular, beleaguered, high-cost, for-profit colleges.”49

Tinkering at the edges to improve for-profit colleges and improve the process of choosing a college is important. But policymakers should also think big on behalf of students, and keep in mind that some students do not feel they have actual choices. Those students pay a premium for their constrained choices. As one student put it: “Weighing all the costs, which is worse, having high debt or not getting a job?”

Below, I present changes that those with power should consider.

1. Make Accreditation Do What the Public Thinks It Does

In the public’s mind, accreditation is a signal that a college is regularly vetted and approved by experts. That should be the case, as accreditation is used to signal to the federal government that a college will be a responsible recipient of federal dollars. Despite how accreditation is intended to work, numerous investigations have found that accreditors are hesitant to withdraw a college’s approval, even when presented with clear evidence of financial mismanagement or fraud.50 As gatekeepers to billions of dollars in direct funding and student aid, accreditors are obligated to step up their practices. When a busy working mom researches her college options, she should be able to trust that accreditation is a signal that she is making good choices.

When a busy working mom researches her college options, she should be able to trust that accreditation is a signal that she is making good choices.

Students told stories of a lack of faculty interaction, a lack of library or resource access, and a lack of academic satisfaction. These are precisely the details that accreditors should be examining. Rather than review mountains of documents and checklists during periodic reviews, accreditors need to develop and deploy a more engaged process that goes beyond taking institutions at their word. Accrediting agencies should review their own standards, policies, and practices and revise them accordingly. Finally, the U.S. Department of Education oversees and approves accreditors, so it also has a role in taking more decisive action against agencies that fail to act as effective gatekeepers.

2. Make Colleges Devote Resources to Education

It is not surprising that many of the students I spoke with reported a lack of interaction from the college after they enrolled. The colleges studied in this report devote tremendous resources to marketing, advertising, and recruiting, and leave little aside for instruction.51 Colleges that sell themselves on their ability to serve so-called nontraditional, working students will never truly do so as long as their budgets are misaligned with that task. It’s true that a frictionless enrollment process is essential for these students who lack, above all else, time. But it is equally essential that their time in courses with other students and engaging with faculty be similarly frictionless. Colleges should not be in the education business if they cannot spend enough to hire instructors who can devote time to students in and out of the classroom, nor spend enough on support services to make sure all students are accessing online resources properly. A federally required level of investment in enrolled-student success should be a no-brainer for all colleges that want access to funding and student aid.

3. Fund Community Colleges and Public Universities

The federal government can play a key role in expanding the quality options available for adults at any stage of life who want the opportunity to go to college. Many busy working adults want the option to study online and are less interested in building face-to-face social connections. However, for-profit online schools should not be seen as the only option for nontraditional students. Nontraditional students should have the choice to study on campuses. To give them that choice, the current regulatory system needs to prohibit other educational options that leave students worse off.52 The Department of Education can take action now on the schools that are on the shakiest legal footing, and those that repeatedly harm students’ prospects. A decisive action the department can make now and in the coming months is to thoroughly review the schools that are up for reapproval for participation in federal funding programs.53 And for steady and sustainable student protection, state and federal governments should enact the sort of requirements that the Trump administration spent the past four years revoking.

Governments also need to provide a huge shift in resources to fully fund the best educational options. A federal–state partnership would go far toward increasing access to debt-free college options. And a thoughtfully designed network of public benefits that takes into account student housing, transportation, nutrition, health care, and childcare would ensure student success through college.54

As policymakers consider their options, they should remember that students do have agency—they choose what they want in our free market system. But this is not an excuse to prop up schools that fail to hold up their end of the agreement. If students are misled by recruiters and advertising, schools must be held responsible. It may be that some schools have already proven they should be eliminated from the field of choices, so that when students exercise their agency they are afforded quality options that match their needs. Congress and the Biden administration should seize the current opportunity to solidify student protections.

Working students who want to pursue their interests and advance their career or earnings potential should not be exploited with worthless degrees. They will spend all their energy and resources on the pursuit. The least they should be able to expect of the system is that their time and money pay off.

Appendix

Between June 24, 2020 and October 23, 2020, I recruited and interviewed thirty-six individuals who attend, attended, work, and/or worked for for-profit colleges and online program management companies. I recruited eligible participants via LinkedIn and Facebook and offered a $30 cash incentive. We sought participants from the following colleges:

American InterContinental University

American Public University/American Military University

Ashford University

Bryant and Stratton College

Capella University

Chamberlain College of Nursing

Colorado Technical University

DeVry University

ECPI University

Florida Career College

Grand Canyon University

Independence University

South University

Strayer University

University of Phoenix

University of the Potomac

Walden University

The target colleges were identified based on a combination of factors, including estimated spending on advertising, prior history of law enforcement actions, and recent changes in ownership or business structure. Additionally, I sought employees of online program management companies to better understand how their role in assisting students with enrolling at public and nonprofit universities differs from or is similar to that of recruiters working for for-profit colleges.

The final list of participants is available in a spreadsheet here. Throughout the report and in the final list of participants, pseudonyms are used to protect the identity of interview participants.

In some cases, interview participants had worked for more than one company and/or attended more than one relevant college.

Interviews took place during business hours and lasted between sixty and ninety minutes. I relied on a semi-structured interview protocol that helped ask the same information of each participant but also allowed in-depth discussion on different topics, when relevant to the individual. The interview protocol was designed based on prior, similar research.55 Interviews were recorded, transcribed, and subsequently analyzed using a web application that facilitates the analysis of qualitative data. Selected participant quotes are shared to elaborate on findings gleaned from the full body of transcripts; all participant input contributed to the findings, though not all participants are quoted in the report.

The findings are not generalizable or meant to be applied beyond the sample of participants interviewed, nor do we claim they are representative of the common student experience at the sampled companies and colleges. As with all qualitative research and some survey research, any interpretation of findings should take into account selection bias, as participants we interviewed voluntarily responded to our study solicitation, and a number of factors could have influenced their willingness to participate, including their overall satisfaction with their college experience, the amount of time they had available to participate, and their access to the Internet, social media, our solicitation, and a phone or video connection. Additionally, as participants were asked to share details of their personal experiences and perceptions, the claims made are reliable insofar as rapport and trust were established during the interview process. However, details that participants shared about their enrollment or completion status, their debt levels, and other personal information were not verified.

Notes

- Stephanie Hall, “How Far Does Your Tuition Dollar Go?,” The Century Foundation, April 18, 2019. https://tcf.org/content/commentary/how-far-does-your-tuition-dollar-go/.

- The Federal Reserve, “Consumer Credit,” February 2021. https://www.federalreserve.gov/releases/g19/current/default.htm; Robert Shireman and Kevin Miller, “Student Debt is Surging at For-Profit Colleges,” The Century Foundation, May 28, 2020. https://tcf.org/content/commentary/student-debt-surging-profit-colleges/; Robert Shireman, “What Does the Gainful Employment Rule Mean for Career Schools Seeking Access to Federal Aid?” The Century Foundation, March 27, 2017. https://tcf.org/content/facts/gainful-employment-rule-mean-career-schools-seeking-access-federal-aid/

- The Institute for College Access and Success, “TICAS Analysis of Official Three-Year Cohort Default Rates,” September 30, 2020, https://ticas.org/accountability/cohort-default-rates/ticas-analysis-of-official-three-year-cohort-default-rates-fy17/.

- For an extensive description and discussion of student experiences in the for-profit college sector, credentialism, and how race, gender, and class affect college choice, see Tressie McMillan Cottom, Lower Ed: The Troubling Rise of For-Profit Colleges in the New Economy (New York: The New Press, 2017). For an in-depth comparison of the choice processes of for-profit college and community college students enrolled in comparable programs in the same geographic area, see Constance Iloh and William G. Tierney, “Understanding For-Profit College and Community College Choice through Rational Choice,” Teachers College Record, 116, no. 8 (2014): 1–34.

- National Center for Education Statistics, “Nontraditional Undergraduates / Definitions and Data,” https://nces.ed.gov/pubs/web/97578e.asp.

- Alexandria Walton Radford, Melissa Cominole, and Paul Skomsvold, “Demographics and Enrollment Characteristics of Nontraditional Undergraduates: 2011-12. Web Tables NCES 2015-025,” National Center for Education Statistics, September 2015, https://nces.ed.gov/pubsearch/pubsinfo.asp?pubid=2015025.

- Katherine Mangan, “The End of the Remedial Course,” The Chronicle of Higher Education, February 17, 2019, https://www.chronicle.com/interactives/Trend19-Remediation-Main.

- Andrew Howard Nichols and J. Oliver Schak, “Broken Mirrors: Black Student Representation at Public State Colleges and Universities,” The Education Trust, March 6, 2019, https://edtrust.org/resource/broken-mirrors-black-representation/.

- Ariela Weinberger, “The System is Rigged: Student Debt and the Racial Wealth Gap,” The Roosevelt Institute, September 9, 2019, https://rooseveltinstitute.org/2019/09/09/the-system-is-rigged-student-debt-and-the-racial-wealth-gap/.

- William J. Hussar and Tabitha M. Bailey, “Projections of Education Statistics to 2027,” National Center for Education Statistics, February 2019, https://nces.ed.gov/pubsearch/pubsinfo.asp?pubid=2019001.

- See Appendix of this report for a description of research methods and participant recruitment strategy.

- United States Senate Committee on Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions, “For Profit Higher Education: The Failure to Safeguard the Federal Investment and Ensure Student Success,” July 30, 2012, https://www.help.senate.gov/imo/media/for_profit_report/Contents.pdf.

- Ibid., p. 61, https://www.help.senate.gov/imo/media/for_profit_report/PartI.pdf.

- Franky, interview with the author by video conference, July 22, 2020.

- Betsy, interview with the author by video conference, July 2, 2020.

- Stephanie Hall, “Three Things Policymakers Can Do to Protect Online Students,” The Century Foundation, September 12, 2019. https://tcf.org/content/commentary/three-things-policymakers-can-protect-online-students/.

- Samantha, interview with the author by video conference, June 24, 2020.

- Betsy, interview.

- Dominique, interview with the author by video conference, June 26, 2020.

- Ibid.

- Ronald, interview with the author by video conference, August 11, 2020.

- Leah, interview with the author by video conference, August 17, 2020.

- Yan Cao, “We’re Calling Out Questionable Advertising. Here’s How,” The Century Foundation, August 18, 2020, https://tcf.org/content/commentary/calling-questionable-college-advertising-heres/; and Veterans Education Success, “Our FTC Petition: Lead Generators,” June 19, 2020, https://vetsedsuccess.org/ftc-petition-lead-generators/.

- Darlene, interview with the author by phone, August 11, 2020.

- Rachel, interview with the author by phone, August 12, 2020.

- Leah, interview.

- Teresa, interview with the author by video conference, August 14, 2020.

- Steve, interview with the author by phone, October 19, 2020.

- Kaiya, interview with the author by video conference, October 19, 2020.

- Ibid.

- Sofia, interview with the author by video conference, October 15, 2020. Out of the small sample of students I interviewed, three had become disabled and subsequently had their loans cancelled. However, student loans can be notoriously difficult to discharge. The Biden administration has already taken steps to streamline the process for people experiencing total and permanent disability. See U.S. Department of Education, “Education Department Announces Relief for Student Loan Borrowers with Total and Permanent Disabilities during the COVID-19 Emergency,” March 29, 2021, https://www.ed.gov/news/press-releases/education-department-announces-relief-student-loan-borrowers-total-and-permanent-disabilities-during-covid-19-emergency.

- Camila, interview with the author by video conference, October 20, 2020.

- Leah, interview.

- Alisha, interview with the author by phone, October 14, 2020.

- Samantha, interview.

- Dakota, interview with the author by phone, October 21, 2020.

- Rebecca, interview with the author by video conference, August 31, 2020. According to Rebecca, a DeVry representative collected prospective student contact information and in doing so made it clear that she was not there to present information that was necessarily useful to job seekers. Like many schools, DeVry has a school profile webpage hosted by the Texas Workforce Commission. See Texas Workforce Commission, “School Summary: DeVry University—Irving Campus,” https://texascareercheck.com/SchoolInfo/SchoolSummary/6100/.

- Aaron, interview with the author by phone, October 22, 2020.

- Rebecca, interview.

- Taela Dudley, “Colleges’ Use of Display Advertising to Recruit Students May Run Risks,” The Century Foundation, May 4, 2021, https://tcf.org/content/report/colleges-use-display-advertising-recruit-students-may-run-risks/.

- Dorothy, interview with the author by phone, October 19, 2020.

- Ann, interview with the author by video conference, September 8, 2020.

- Ronald, interview.

- Robert Shireman, “We Need to Retain Protections against Scam Online Schools,” The Century Foundation, January 18, 2018, https://tcf.org/content/commentary/need-retain-protections-scam-online-schools/.

- Rebecca, interview.

- Danielle, interview with the author by phone, August 12, 2020.

- Ann, interview.

- Claire, interview with the author by video conference, August 11, 2020.

- Cottom, Lower Ed.

- United States Government Accountability Office, “Higher Education: Expert Views of US Accreditation,” January 23, 2018, https://www.gao.gov/products/gao-18-5.

- Stephanie Hall, “How Much Education Are Students Getting for Their Tuition Dollar?,” The Century Foundation, February 28, 2019, https://tcf.org/content/report/much-education-students-getting-tuition-dollar/; Senate Committee on Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions, “For Profit Higher Education.”

- The Century Foundation, “Voters Overwhelmingly Support Guardrails on For-Profit Colleges,” January 28, 2021, https://tcf.org/content/about-tcf/voters-overwhelmingly-support-guardrails-profit-colleges-finds-tcf-data-progress-poll/.

- Yan Cao and Kevin Miller, “The Education Department Should Review These Risky Schools,” The Century Foundation, March 15, 2021, https://tcf.org/content/commentary/the-education-department-should-review-these-risky-schools/; and Stephanie Hall, Ramond Curtis, and Carrie Wofford, “What States Can Do To Protect Students from Predatory For-Profit Colleges,” The Century Foundation, May 26, 2020, https://tcf.org/content/report/states-can-protect-students-predatory-profit-colleges/.

- Peter Granville, “Pathways to Simplify and Expand SNAP Access for California College Students,” The Century Foundation, October 29, 2020, https://tcf.org/content/report/pathways-simplify-expand-snap-access-california-college-students/; and Jen Mishory, “College Affordability Act Makes Down Payment on Debt-Free College,” The Century Foundation, December 11, 2019, https://tcf.org/content/commentary/college-affordability-act-makes-payment-debt-free-college/.

- Iloh and Tierney, “Understanding For-Profit College and Community College Choice Through Rational Choice.”