The most effective way to change the world these days seems to be to plant a message directly in the brain of its most powerful inhabitant: Donald J. Trump, president of the United States of America.

Although the U.S. executive branch always had a fairly free hand in foreign policy, ideas would normally need to snake their way through a whole series of interagency deliberations before landing on the Oval Office desk for a final verdict. But as media leaks and disgruntled former members of the Trump administration have made abundantly clear, decision-making in the current White House is both more temperamental and more personalized, revolving around a president known for forming strong opinions based on ideas picked up from television, friends, and other outside sources.

Advocates inside and outside the U.S. government increasingly seem to operate under the assumption that the best way to influence American policy is to sidestep the bureaucracy and speak directly to an audience of one: Donald Trump. And, last September, that’s exactly what two pro-opposition Syrian-Americans managed to do after paying a Republican lobbyist to get seats at an Indiana fundraising dinner.1

President Trump later told the story:

I was at a meeting with a lot of supporters, and a woman stood up and she said, “There’s a province in Syria with 3 million people. Right now, the Iranians, the Russians, and the Syrians are surrounding their province. And they’re going to kill my sister.”2

By his own admission, Trump hadn’t heard of Idlib, an insurgent-held province backed by Turkish troops. But after dinner, the president picked up a copy of “the failing New York Times” and found an article that also mentioned Idlib. Having thus confirmed that it was an actual place in actual trouble, Trump stormed onto Twitter:

President Bashar al-Assad of Syria must not recklessly attack Idlib Province. The Russians and Iranians would be making a grave humanitarian mistake to take part in this potential human tragedy. Hundreds of thousands of people could be killed. Don’t let that happen!

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) September 3, 2018

Over the next few days, U.S. officials started signaling that chemical strikes or “reckless” killing in Idlib could draw a U.S. response.3 On September 17, Turkey and Russia brokered a ceasefire deal that ended the crisis.4 Trump had little to do with it, but was quick to claim credit.5

The fact that Trump pays so little attention to Syria—where he commands 2,000 troops and the U.S.-backed Syrian Democratic Forces rule one-third of the country—has been a major factor in the evolution of U.S. policy, flinging it first in this direction and then in the other, and allowing others to shape policy in the president’s stead.

Indeed, the story of America’s evolving Syria strategy is a story of strategic drift and runaway bureaucracies. Under two very different presidents, Obama and Trump, Syria policy has followed a life of its own, often appearing almost immune to executive direction.

In the first five years of the war, the U.S. foreign policy establishment—famously dismissed as “the blob” by Obama adviser Ben Rhodes—kept coming up with proposals to expand American intervention in Syria no matter what President Obama requested.6 Under President Trump, who seems even more averse to open-ended Middle Eastern deployments than Obama but who also lacks the latter’s obsessive attention to detail, the U.S. policy apparatus has rattled on in its own direction without oversight. Trump’s personal interventions can still easily overpower any institutional bias, but they’re few and far between. The president’s most recent directive to get out of Syria has already mutated into a plan for staying forever, an ambition that will either be reversed or demand the resources to match.

America’s expanding military footprint in Syria raises troubling questions about how national security policy is made in Washington. How is it that America is once again committing to indefinite engagement in a Middle Eastern civil war under yet another president who came into office vowing the opposite—to scale back U.S. involvement in the Middle East?

What Makes Trump Tick

In contrast to Washington’s intervention-happy foreign policy establishment, which spent the better part of the Syrian war castigating former president Barack Obama as a feckless fool for not blasting Assad out of power, Trump has consistently taken a dim view of U.S. involvement in the Middle East, including Syria.7 Even as Obama came under daily fire for not supporting the Syrian rebels enough, Trump—then just a quirky celebrity, as far as the American public was concerned—slammed them as “radical jihadi Islamists who are murdering Christians” and “want to fly planes into our buildings.”8

Many of the Syrian rebels are radical jihadi Islamists who are murdering Christians. Why would we ever fight with them?

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) September 6, 2013

Once in office, Trump quickly abolished a CIA program put in place by Obama, which had trained and armed thousands of anti-Assad fighters.9 Since then, he has struck Assad’s forces twice in retaliation for alleged chemical attacks, but, as several officials, ex-officials, and analysts in Washington told me in a recent round of interviews, he pays little if any attention to the broader question of where the Syrian war is headed.10 The exception, interviewees said, is for Syria-related issues that resonate with his base or even outside it. At the top of that list comes beating the so-called Islamic State, followed by being friendly to Israel and unfriendly to Iran—things that may prompt action in Syria, but are ultimately not about Syria.

As officials and pundits jostle over U.S. Syria policy, where in the absence of presidential oversight they enjoy a new level of direct influence, they have had to rephrase their arguments in Trump-compatible terms to stand a chance of being heard.

The Islamic State problem has long since been co-opted by both sides of the debate, leaving one faction of officials to insist that Assad needs to go because he’s a magnet for jihadism while another says jihadism thrives in the anarchy that came from trying to topple Assad.11

The Iran–Israel factor has a more straightforward impact on U.S. policy, having spawned a whole series of buzzword-laden arguments for muscular tactics against Assad. Pride of place is held by the “land bridge,” which, or so the argument goes, Iran must urgently be prevented from extending across Iraq and Syria to Lebanon, Israel, and the Mediterranean.12 On closer inspection, the only practical application of this plan is to have the U.S. military cut road access between Syria and Iraq, two territorially contiguous nations, for all perpetuity. It is, in other words, a thinly veiled pitch for just occupying part of Syria indefinitely, possibly to protect Israel or to nudge Assad out through a UN peace process, but mostly just to spite Tehran.13

The Tillerson Debacle

Those were the influences buffeting the State Department as it tried to craft a Syria strategy in 2017. There wasn’t much to work with. Obama’s old policy, such as it was, had suffered a catastrophic meltdown when confronted first with reality and then with Russia; and Trump had failed to string together even three coherent sentences on Syria during his presidential campaign.

For the first few months of the new administration, policy drifted in no particular strategic direction. By late summer 2017, then-secretary of state Rex Tillerson had finally come up with a plan that promised to take the president’s varied interests into account while in fact recommitting to the anti-Assad line and rejecting a U.S. pullout. Trump signed off on it that autumn, momentarily swayed or simply distracted.

The public rollout came in a January 2018 speech at Stanford University, in which Tillerson vowed to stay engaged in Syria and oust Assad by means of non-military pressure.14 The secretary explained that the United States would keep its troops embedded among the Kurds of northeastern Syria to prevent a jihadi resurgence, and would also ramp up economic pressure until Damascus accepted a “post-Assad future” that would neither attract jihadis nor permit “malicious Iranian influence.”15

The president’s most recent directive to get out of Syria has already mutated into a plan for staying forever, an ambition that will either be reversed or demand the resources to match.

Why the prospect of more economic misery would be the drop to overfill Assad’s proverbial bucket, when killing up to 100,000 Syrian soldiers, slashing four-fifths of GDP, and cornering his government on (at one point) 17 percent of Syrian soil didn’t move him an inch, was left for diplomats to figure out.16

But it wasn’t the mismatched means and ends that felled the Tillerson plan. It was simmering conflict between the secretary and his boss (whom he had, famously and allegedly, called a “moron”17), in addition to Trump’s instinctive dislike for mucking around in the Middle East. Almost immediately after Tillerson’s Stanford speech, Trump began to question why the United States still had troops in Syria, apparently feeling he’d been conned into accepting something he didn’t like and that he didn’t think U.S. taxpayers should be paying for.

Tillerson was sacked in March 2018. Around the same time, the president reportedly read a Washington Post story about Tillerson’s promise of limited economic aid to Kurdish-ruled areas outside Assad’s control, which sent him into a fit of rage.18 Out of nowhere, he froze the U.S. stabilization budget for Syria, saying the Gulf oil kingdoms could pay for it if they wanted it so much, and demanded that U.S. troops should come home “as soon as possible.”19

The sudden intervention unnerved both those American officials who were intent on staying in Syria in order to weaken Assad and/or Iran and those who were in theory eager to leave Syria, but who also worried about the consequences of a disorderly pullout. As Trump’s temper cooled, senior officials managed to push troop withdrawals back to autumn 2018 and buy themselves time to figure something out. But the United States was once again left without a Syria strategy.

Anti-Iran Policy Takes Precedence

Over the summer of 2018, U.S. officialdom started to assemble the president’s latest preferences into a new plan to replace the one ejected alongside Tillerson. But like some indestructible squishy toy, Syria policy immediately began to reassume the open-ended and interventionist form that Trump had just denounced.

One reason was that the president’s hard-ball tactics had worked—sort of. Arab and European leaders winced at the prospect of a quick withdrawal, and when U.S. diplomats came panhandling, allied nations agreed to fund the stabilization of former jihadi-held areas in order to let American taxpayers off the hook without derailing the Syria mission. The president was pleased.20

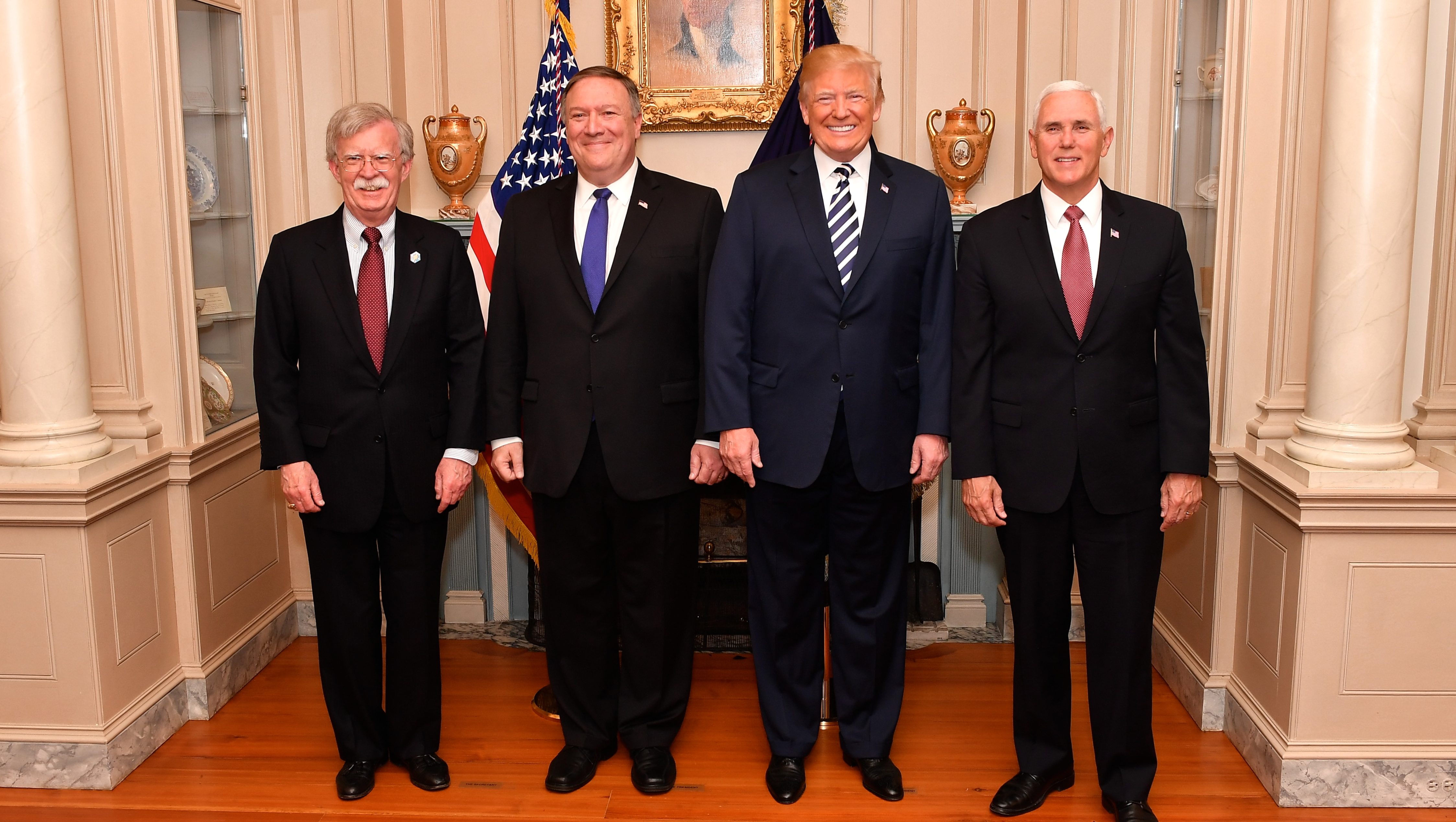

Another reason was the surging influence of citizens concerned by the Iranian land bridge. As he moved to exit the “decaying and rotten” Iranian nuclear deal in spring 2018, Trump started to stuff his government with Middle East hawks who saw Syria primarily through an anti-Iran lens.21 That April, Trump replaced his national security adviser H. R. McMaster with John Bolton, an advocate of bombing Iran and overthrowing its regime, while another top-tier Iran hawk, CIA chief Michael Pompeo, was sworn in to succeed Tillerson.22

In office, Bolton and Pompeo have renounced regime change in Tehran, instead settling for a policy of “maximum pressure” that is supposed to pave the way for direct talks with Iran’s leaders and a new, better nuclear deal.23 The concept seems patterned on Trump’s North Korea fliplomacy, and so may have originated in the Oval Office.

However, Bolton’s real views are well known—he doesn’t want a better deal, he wants regime change—and Pompeo’s list of preconditions has been so expansive—Iranian withdrawal from Syria being just the appetizer—that they amount to asking the ayatollahs to come out with their hands over their heads.24 Rather than engaging with American demands, the Iranians have therefore spent summer and autumn showing how they can inflict asymmetric damage, threaten U.S. interests and allies, and disrupt oil markets.25 As for evacuating Syria, forget about it: “We stay there as long as Syria wants [it] so,” said a commander of the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps, the paramilitary force that controls Iran’s Syria deployment.26

In August, Pompeo gifted the Syria portfolio to James Jeffrey, a former ambassador to Iraq and Turkey, in a newly created role as the secretary’s representative for Syria engagement. Jeffrey would be backed by another experienced Middle East hand, Syria Envoy Joel Rayburn, who reportedly remains a firm believer not only in the necessity of Assad’s removal but also in its possibility.

By early September, Trump had re-approved plans for an indefinite stay in Syria, with even more fanciful goals than those previously formulated by Tillerson.27 “We’re not going to leave as long as Iranian troops are outside Iranian borders, and that includes Iranian proxies and militias,” Bolton explained.28 Going by current U.S. rhetoric, America seems to have committed to staying in Syria until the end of days, or at least for the duration of the Trump presidency, whichever arrives first.

But hardline Bolton statements aside, the actual extent of the strategy is still very unclear. America’s list of goals and priorities has never been laid out in full, and senior officials constantly seem to be hedging against changes in the president’s thinking.

For example, Jeffrey has repeatedly made headlines by insisting the United States will stay in Syria for the long haul. But in the fine print of his briefings, one also finds him saying the United States could remain in Syria “diplomatically” and without “boots on the ground.”29 The military, he says, is there to beat the Islamic State and what happens after that is up to the president to decide. Jeffrey has even brought up the Russia–Georgia war of 2008 as an example of how the United States could stay involved through diplomacy and aid from over the horizon.30

And what about Assad?

“We’re not about regime change,” Jeffrey recently explained, but then added that he wants “fundamental change in the Syrian regime” and that a political transition should create “a Syrian regime that is not as toxic as the current one,” which sounds an awful lot like regime change.31

It doesn’t matter: the terminological hair-splitting may serve some therapeutic purpose at Foggy Bottom, but any proposal for genuine change in Damascus is a non-starter for the rulers of Syria, Russia, and Iran. They hold the ground, so they call the shots. But regardless of how it is motivated, the policy does have real-world consequences for Syria and for the nature of America’s involvement there.

The Senior Skeptics

The decision to wield northeastern Syria as a club against the ruling cliques in Damascus and Tehran has many supporters in the U.S. government, as evidenced by the fact that it is now official policy. But there are critics, too—especially in those parts of government that are directly concerned with events on the ground.

Strong voices at the Pentagon continue to push back against expanding policy goals in the absence of expanded resources, noting the threat this poses to U.S. troops but also the implicit threat to America’s Syrian allies.32 U.S. troops have fought and bled alongside the Kurdish-led Syrian Democratic Forces for over four years, and CENTCOM has emerged as a bastion of support for taking their interests into account. While that can translate into a skepticism toward a quick pullout that would leave Syrian Kurds at the mercy of Damascus, Ankara, or both, it also means there is intramural resistance to the idea of forcing America’s local allies into an underfunded, open-ended standoff with Tehran that could ruin their chances of nonlethal accommodation with Damascus.

That attitude also seems to reign in the office of Brett McGurk, who as special presidential envoy for the anti-Islamic State mission runs a large chunk of America’s Syria policy outside Jeffrey’s purview. Having served all three presidents—Bush, Obama, and Trump—and now overseeing anti-jihadi operations in both Syria and Iraq, McGurk wields an extraordinarily strong hand. But McGurk’s warm ties to the PKK-linked Syrian Kurdish groups that crushed the Islamic State in Syria are a red flag in Turkish eyes, and his lack of enthusiasm for the broader Syrian opposition has put him at odds with transition-minded colleagues.33 Both sides of the debate readily admit that the incongruity of McGurk’s relentless jihadi-hammering with the American campaign to unseat Assad, which to an extent relied on turning a blind eye to jihadism, has contributed to U.S. policy incoherence since 2014.

As long as Iran has this gourmet’s menu of soft U.S. targets to pick from and the United States remains unwilling to simply suck up the casualties, stepping out on the slippery slope of tit-for-tat retaliation without wanting to go to war seems like a losing proposition.

Unsurprisingly, McGurk does not appear to be a fan of the current strategic trajectory in Syria. Multiple sources told me he has trashed the idea of trying to overthrow Assad and expelling Iran with the limited means at hand, and that, like many in the military, he is now primarily dedicated to making sure the Islamic State cannot respawn and that America’s Syrian Democratic Forces allies will land on their feet whatever else may happen. But talk in Washington is also that McGurk may be about leave his job soon, perhaps by January 2019.34

The same goes for another alleged senior skeptic of America’s expanding policy agenda in Syria, David Satterfield. A career diplomat with nearly four decades of Middle East experience under his belt, Satterfield has been the acting assistant secretary for near eastern affairs since 2017. He is now reportedly about to be reassigned to Jeffrey’s old job as U.S. ambassador to Ankara, or possibly Cairo. Pompeo has already called on David Schenker, a Bush-era Pentagon official now of the Washington Institute for Near East Policy, to fill the assistant secretary position.

So far, however, that hasn’t worked out. Schenker’s confirmation has been blocked for months by Democratic senator Tim Kaine, who is leveraging the issue to protest Trump’s refusal to consult Congress before striking Syria in 2017 and 2018.35

American Vulnerabilities

For the U.S. military, force protection is a top concern in case of widening conflict with Iran and its regional allies and proxies. Pentagon officials and serving commanders have reportedly signaled unease at what they see as a growing mismatch between goals, risks, and resources, noting, for example, that the United States hasn’t had an aircraft carrier in the Persian Gulf since March.36

The roughly 2,000 or 2,500 American soldiers, diplomats, and contractors in Syria have so far faced few direct threats, and would easily win a conventional battle. But U.S. officials and analysts worry that Tehran and Damascus may have other tricks up their sleeves. The troops in Syria are so few that they must rely on local allies for key elements of their security, making it hard to guard against a determined enemy in an area crawling with agents and infiltrators—and the situation is even worse in neighboring Iraq. There, much of the security apparatus is run by Iran-friendly Islamists, pro-Tehran militants have seeded eastern Baghdad with ground-embedded rocket tubes pointed at the U.S. Embassy, and Pompeo has already been forced to abandon the U.S. Consulate in Basra under Iranian pressure.37

As long as Iran has this gourmet’s menu of soft U.S. targets to pick from and the United States remains unwilling to simply suck up the casualties, stepping out on the slippery slope of tit-for-tat retaliation without wanting to go to war seems like a losing proposition.

Serving U.S. officials will of course parrot their prepared talking points whatever their own views, but officials from the last administration—who tend to dislike Trump anyway—have few qualms about attacking the new policies on the record.

“You can make a case for keeping [troops in Syria as leverage against Iran] as long as you’re realistic about what you get for that presence,” Philip Gordon, who oversaw White House Middle East policy between 2013 and 2015, told me in an interview at his Council on Foreign Relations office in Washington, voicing strong skepticism against the current policy. “Look, fair enough,” Gordon said, throwing up his hands, “if you believe defeating the Russians and Iranians and getting rid of Assad are overwhelming U.S. national interests, okay, fine—but just pay the price. Understand the cost of that, then do it.”38

Others have been blunter.

“It’s complete folly to think you’re going to threaten the Syrians or the Russians or the Iranians into anything,” former U.S. secretary of defense Chuck Hagel recently told Defense One. “The Iranians live there. The U.S. doesn’t live in the Middle East. Unless you’re going to somehow eliminate the geopolitical realities of that—well, good luck Mr. Bolton.”39

But Also, What’s on TV?

For all of President Trump’s swamp-draining, blob-popping rhetoric and the many promises to bring troops home, he can’t seem to make that policy stick.

Every time the president takes his hands off the wheel, the foreign policy apparatus starts to edge back toward its preferred course of action, which is action. Syria is the most blatant example of this path-dependent pro-intervention bias, in which the American foreign policy bureaucracy strains forward to control, reorganize, or fix the Middle East whenever given more leash to move. But it is a broader, systemic problem that appears to affect much of U.S. foreign policy. It has troubled a succession of presidents, and Trump’s special mix of absent-mindedness and heavy-handedness has just laid bare the depth of the problem.

Whereas Obama came to be seen even by his supporters as a maddening micromanager, who would rather let a decision die of old age than entrust it prematurely to a bureaucracy whose instincts he mistrusted, Trump simply drops a piano on the thing he does not like—like that CIA program, or a Syrian nerve gas attack. For all of the expert views to the contrary, it kind of works, and even when it doesn’t, Trump never suffers much political damage.

As the most powerful man in the world, and not afraid to act like it, Donald Trump has repeatedly shown that he can flip superpower strategy upside down and throw policymakers out of office at the stroke of a pen. Syria’s future shape and functioning will to a significant degree be determined by him.40 But for all of his power, it remains unclear to what extent Trump endorses or understands the Syria strategy formulated for him by appointees operating with little oversight and plenty of personal initiative.

Jeffrey said in early September he’s “confident” that the president is on board with the new plan, but in the absence of confirmation from Trump himself, few are willing to take his word for it.41 Quite the contrary, much of the U.S. foreign policy community seems wearily resigned to the fact that their president could, at any moment, spin around and butcher the current Syria strategy after hearing something he didn’t like in the news or at a lobbyists’ dinner.42

Until then, however, Donald Trump’s dominant trait—a resounding lack of interest in any issue not relevant to his own person, power, or popularity—may in fact be the perfect cornerstone for America’s new Syria policy. Like Schrödinger’s famous cat, which remains hypothetically both dead and alive inside its box until the lid is lifted, Donald Trump can happily remain an anti-Iran interventionist and an America First isolationist as long as he, himself, doesn’t see the contradiction.

But then, one day, he will wake up in his White House bed, reach for the remote and flip on Fox & Friends—and start to frown, and go red in the face with anger, and reach for his smartphone.

This work was supported by a research grant from the Harry Frank Guggenheim Foundation and by the Carnegie Corporation of New York.

Notes

- Dion Nissenbaum, “From Anguished Appeal to Presidential Tweet: The Doctor Who Changed U.S. Policy,” Wall Street Journal, October 18, 2018, https://www.wsj.com/articles/from-anguished-appeal-to-presidential-tweet-how-a-doctor-changed-u-s-policy-153986400D0.

- Transcript of Trump’s remarks at the Lotte New York Palace, White House website, September 27, 2018, https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefings-statements/press-conference-president-trump-2.

- Lara Seligman, “U.S. Ramps Up Threats of Military Action Against Syria’s Assad,” Foreign Policy, September 10, 2018, https://foreignpolicy.com/2018/09/10/us-ramps-up-threats-of-military-action-against-syria-assad-airstrike-trump-bolton.

- Aron Lund, “After Russia-Turkey deal, the fate of Syria’s Idlib hangs in the balance,” IRIN News, October 2, 2018, https://www.irinnews.org/analysis/2018/10/02/after-russia-turkey-deal-fate-syria-s-idlib-hangs-balance.

- Transcript of Trump’s remarks at the Lotte New York Palace, White House website, September 27, 2018, https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefings-statements/press-conference-president-trump-2.

- David Samuels, “The Aspiring Novelist Who Became Obama’s Foreign-Policy Guru,” New Yorker, May 5, 2016, https://www.nytimes.com/2016/05/08/magazine/the-aspiring-novelist-who-became-obamas-foreign-policy-guru.html.

- Aron Lund, “A Secondary Thought,” Carnegie Middle East Center, October 10, 2016, https://carnegie-mec.org/diwan/64849?lang=en.

- Donald Trump on Twitter, September 6, 2013, https://twitter.com/realdonaldtrump/status/376053255245008896; and August 28, 2013, https://twitter.com/realdonaldtrump/status/372795204710830080.

- Aron Lund, “How Assad’s Enemies Gave Up on the Syrian Opposition,” The Century Foundation, October 17, 2017, https://tcf.org/content/report/assads-enemies-gave-syrian-opposition.

- Aron Lund, “No Justice for Khan Sheikhoun,” The Century Foundation, November 6, 2017, https://tcf.org/content/report/no-justice-khan-sheikhoun; author’s interviews in Washington, D.C., October and November 2018.

- Robert Malley and Jon Finer, “The Long Shadow of 9/11: How Counterterrorism Warps U.S. Foreign Policy,” Foreign Affairs, July/August 2018, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/2018-06-14/long-shadow-911; author’s interviews, Washington, October and November 2018.

- For example, “US Should Develop Syria Policy that Includes Syrian End State Devoid of Iran’s Influence,” Foundation for the Defense of Democracies, July 11, 2018, https://www.fdd.org/analysis/2018/07/11/fdd-study-us-should-develop-syria-policy-that-includes-syrian-end-state-devoid-of-irans-influence.

- Aron Lund, “Mission impossible for next UN Syria envoy?,” IRIN News, October 29, 2018, https://www.irinnews.org/analysis/2018/10/29/mission-impossible-next-un-syria-envoy.

- Transcript of speech by Rex W. Tillerson, “Remarks on the Way Forward for the United States Regarding Syria,” U.S. Department of State, January 17, 2018, https://www.state.gov/secretary/20172018tillerson/remarks/2018/01/277493.htm.

- Aron Lund, “As Syria looks to rebuild, US and allies hope money can win where guns lost,” IRIN News, May 22, 2018, https://www.irinnews.org/analysis/2018/05/22/syria-looks-rebuild-us-and-allies-hope-money-can-win-where-guns-lost; Transcript of speech by Rex W. Tillerson, “Remarks on the Way Forward for the United States Regarding Syria,” U.S. Department of State, January 17, 2018, https://www.state.gov/secretary/20172018tillerson/remarks/2018/01/277493.htm.

- David Ignatius, “What the demise of the CIA’s anti-Assad program means,” Washington Post, July 20, 2017, https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/what-the-demise-of-the-cias-anti-assad-program-means/2017/07/20/f6467240-6d87-11e7-b9e2-2056e768a7e5_story.html; “Syria’s GDP at Only a Fifth of Pre-Uprising Level,” The Syria Report, May 15, 2018, http://www.syria-report.com/news/econ-omy/syria%252525E2%25252580%25252599s-gdp-only-fifth-pre-uprising-level; Columb Strack, “Syrian government no longer controls 83% of the country,” Jane’s, August 24, 2015, https://www.janes.com/article/53771/syrian-government-no-longer-controls-83-of-the-country.

- Julian Borger, “Rex Tillerson says he won’t quit but doesn’t deny calling Trump a ‘moron,’” The Guardian, October 4, 2017, https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2017/oct/04/rex-tillerson-trump-moron.

- Elise Labott, “Trump puts hold on more than $200 million in Syria recovery funds,” CNN, March 31, 2018, https://edition.cnn.com/2018/03/31/politics/trump-syria-funds/index.html; Aron Lund, “The Islamic State Is Collapsing, but Raqqa Is in Ruins,” The Century Foundation, October 18, 2017, https://tcf.org/content/commentary/islamic-state-collapsing-raqqa-ruins.

- Elise Labott, “Trump puts hold on more than $200 million in Syria recovery funds,” CNN, March 31, 2018, https://edition.cnn.com/2018/03/31/politics/trump-syria-funds/index.html; Alison Chung and Alix Culbertson, “Trump still wants US troops to leave Syria ‘as quickly as possible’ – White House,” Sky News, April 16, 2018, https://news.sky.com/story/assad-accuses-us-uk-and-france-of-waging-campaign-of-lies-to-launch-syria-air-strikes-11333212.

- Teleconference briefing by David Satterfield and Brett McGurk, U.S. State Department, August 17, 2018, https://www.state.gov/r/pa/prs/ps/2018/08/285202.htm; Matthew Lee, “US ends Syria stabilization funding, cites more allied cash,” Associated Press, August 17, 2018, https://www.apnews.com/31eaa3ca51ed480f90ef6363156b710e.

- “Remarks by President Trump on the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action,” White House, May 8, 2018, https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefings-statements/remarks-president-trump-joint-comprehensive-plan-action; Aron Lund, “The Middle East after the Iran Deal,” The Century Foundation, May 9, 2018, https://tcf.org/content/commentary/middle-east-iran-deal.

- John R. Bolton, “To Stop Iran’s Bomb, Bomb Iran,” New York Times, March 26, 2015, https://www.nytimes.com/2015/03/26/opinion/to-stop-irans-bomb-bomb-iran.html; “Bolton: ‘Our Goal Should Be Regime Change in Iran,’” Fox News, January 1, 2018, insider.foxnews.com/2018/01/01/john-bolton-trump-us-goal-should-be-regime-change-iran.

- “Bolton: ‘Our Goal Should Be Regime Change in Iran,’” Fox News, January 1, 2018, insider.foxnews.com/2018/01/01/john-bolton-trump-us-goal-should-be-regime-change-iran; Michael R. Pompeo, “Confronting Iran The Trump Administration’s Strategy,” Foreign Affairs, November/December 2018, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/middle-east/2018-10-15/michael-pompeo-secretary-of-state-on-confronting-iran

- Mike Pompeo, “After the Deal: A New Iran Strategy,” transcript of a speech at the Heritage Foundation in Washington, U.S. State Department website, May 21, 2018, https://www.state.gov/secretary/remarks/2018/05/282301.htm.

- “Report: Iran moves missiles to Iraq that can hit Tel Aviv,” YNet, August 31, 2018, https://www.ynetnews.com/articles/0,7340,L-5338568,00.html; Missy Ryan, “Citing Iran, military officials are alarmed by shrinking U.S. footprint in the Middle East,” Washington Post, November 3, 2018, https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/national-security/military-officials-alarmed-about-shrinking-military-footprint-in-middle-east-as-administration-pressures-iran/2018/11/03/44e599f4-b152-4fdc-938e-744fa5e3d6fe_story.html; Krishnadev Calamur, “Trump’s Latest Warning to Iran Didn’t Come Out of Nowhere,” The Atlantic, September 12, 2018, https://www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2018/09/trump-warns-iran-shia-militia-iraq/569989; Seth J. Frantzman, “Iran Fires Ballistic Missiles at Syria as Revenge for Ahvaz Attack,” Jerusalem Post, October 1, 2018, https://www.jpost.com/Middle-East/Iran-News/Iranian-ballistic-missiles-fired-at-Syria-as-revenge-for-Ahvaz-attack-568384; Nic Robertson, “All eyes on Strait of Hormuz as US-Iran tensions build,” CNN, August 4, 2018, https://edition.cnn.com/2018/08/04/middleeast/iran-strait-of-hormuz-intl/index.html; David Sheppard, Ahmed Al Omran, and Anjli Raval, “Saudis suspend Red Sea oil shipments after tanker attacks,” Financial Times, July 25, 2018, https://www.ft.com/content/f0858962-9005-11e8-b639-7680cedcc421.

- “‘IRGC Can Manage US Forces in M.E. in Short Time Span’,” al-Manar, November 4, 2018, english.almanar.com.lb/614220.

- Karen DeYoung, “Trump agrees to an indefinite military effort and new diplomatic push in Syria, U.S. officials say,” Washington Post, September 6, 2018, https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/national-security/in-a-shift-trump-approves-an-indefinite-military-and-diplomatic-effort-in-syria-us-officials-say/2018/09/06/0351ab54-b20f-11e8-9a6a-565d92a3585d_story.html.

- Joe Gould and Tara Copp, “Bolton: US troops staying in Syria until Iran leaves,” Defense News, September 24, 2018, https://www.defensenews.com/global/the-americas/2018/09/24/bolton-us-troops-staying-in-syria-until-iran-leaves.

- Transcript of briefing by James F. Jeffrey, Lotte New York Palace Hotel, New York, September 27, 2018, U.S. State Department website, https://www.state.gov/r/pa/prs/ps/2018/09/286289.htm.

- Transcript of briefing by James F. Jeffrey, Washington, November 14, 2018, U.S. State Department website https://www.state.gov/r/pa/prs/ps/2018/11/287368.htm.

- Transcript of briefing by James F. Jeffrey, Washington, November 14, 2018, U.S. State Department website https://www.state.gov/r/pa/prs/ps/2018/11/287368.htm.

- Mark Perry, “Mattis’s Last Stand Is Iran.” Foreign Policy, June 28, 2018, https://foreignpolicy.com/2018/06/28/mattiss-last-stand-is-iran.

- The main constituent group of the Syrian Democratic Forces is the People’s Protection Units, or YPG, a Kurdish group that serves as the PKK’s armed wing in Syria. The PKK, or Kurdistan Worker’s Party, is a leftist and Kurdish-nationalist group that has been fighting the Turkish government since the 1980s. McGurk has frequently pushed a less opposition-friendly line than other State Department heavyweights, once slamming Idlib, which the U.S. government seeks to protect against Syrian government attacks, as “the largest al-Qaeda safe haven since 9/11.” Remarks by Brett McGurk at a Middle East Institute event in Washington on July 27, 2017, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UgzqabDYK7I#t=59m03s.

- Author’s interviews, including in Washington in October and November 2018.

- Robbie Gramer and Lara Seligman, “The War Over War Powers Heats Up in Congress,” Foreign Policy, September 10, 2018, https://foreignpolicy.com/2018/09/10/the-war-over-war-powers-heats-up-in-congress-state-department-middle-east-nominee-david-schenker-blocked-senator-tim-kaine-white-house-legal-authority-syria-strike-middle-east-diplomacy.

- Missy Ryan, “Citing Iran, military officials are alarmed by shrinking U.S. footprint in the Middle East,” Washington Post, November 3, 2018, https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/national-security/military-officials-alarmed-about-shrinking-military-footprint-in-middle-east-as-administration-pressures-iran/2018/11/03/44e599f4-b152-4fdc-938e-744fa5e3d6fe_story.html.

- Fanar Haddad, “Understanding Iraq’s Hashd al-Sha’bi State and Power in Post-2014 Iraq,” The Century Foundation, March 5, 2018, https://tcf.org/content/report/understanding-iraqs-hashd-al-shabi; Renad Mansour, “After Mosul, Will Iraq’s Paramilitaries Set the State’s Agenda?,” The Century Foundation, January 27, 2017, https://tcf.org/content/report/mosul-will-iraqs-paramilitaries-set-states-agenda; Krishnadev Calamur, “Trump’s Latest Warning to Iran Didn’t Come Out of Nowhere,” The Atlantic, September 12, 2018, https://www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2018/09/trump-warns-iran-shia-militia-iraq/569989; “U.S. To Close Consulate In Iraq, Citing ‘Threats’ From Iran And Allied Militias,” Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, September 29, 2018, https://www.rferl.org/a/us-closes-consulate-in-basra-iraq-citing-threats-from-iran-quds-force-allied-shiite-militia/29515934.html.

- Author’s interview with Philip Gordon, Washington, October 2018.

- Katie Bo Williams, “‘It’s Complete Folly’: Hagel Says Trump Administration Can’t Threaten Iran Out of Syria,” Defense One, October 4, 2018, https://www.defenseone.com/politics/2018/10/its-complete-folly-hagel-says-trump-administration-cant-threaten-iran-out-syria/151808.

- Aron Lund, “The Shape of Syria to Come,” August 13, 2018, https://www.worldpoliticsreview.com/articles/25498/the-shape-of-syria-to-come.

- Raghida Dergham, “There is a new coherent strategy under US envoy to Syria,” The National, September 8, 2018, https://www.thenational.ae/opinion/comment/there-is-a-new-coherent-strategy-under-us-envoy-to-syria-1.768208.

- Author’s interviews with U.S. and non-U.S. officials and analysts, including in Washington in October and November 2018.