The war in Syria may go on for many years more, but, clearly, Bashar al-Assad is winning it.1 Having secured his grip on key cities like Homs and Damascus, the Syrian president’s forces retook rebel-held parts of Aleppo in late 2016 and reached the eastern city of Deir al-Zor last month, while Russian-brokered truces locked down his gains in the west.2

Assad’s opponents often point out that these advances rely on foreign support. That’s true, but Russian and Iranian involvement in Syria is just one side of the coin: no less important is the slackening of international support for the Syrian opposition.

For a few years, no cause was as celebrated in Western and Arab capitals as Syria’s uprising. The United States and its closest European allies ratcheted up pressure on Assad’s regime over spring and summer 2011, imposing a raft of sanctions and calling on the dictator to step aside. Qatar, Turkey, and Saudi Arabia delivered thousands of tons of military equipment delivered to Syria from 2012 onward.3 Sources close to the Qatari regime claim that it donated as much as $3 billion between 2011 and 2013.4 In 2013, President Barack Obama initiated “one of the costliest covert action programs in the history of the C.I.A.,” with one official later estimating that American-backed rebels may have killed and wounded as many as 100,000 Syrian or allied soldiers.5

Yet that support failed to topple Assad, whose Russian and Iranian allies predictably counter-escalated by increasing their own support to his regime. As Syria devolved into a chaotic, sectarian civil war accompanied by surging regional instability and jihadi extremism, the resolve of anti-Assad nations faded away and international attention began to drift toward treating the second-order effects of the war.

Whereas more than 100 nations—over half the states in the world—joined an anti-Assad coalition known as the “Friends of Syria” in 2012, the armed opposition had to settle for military support from a much smaller group—mainly the United States, France, the United Kingdom, Saudi Arabia, Jordan, Qatar, and Turkey—in the years that followed. By 2017, these nations were also exhausted. They are now subtly shifting the goalposts to deemphasize demands for Assad’s resignation, downsizing support programs for the opposition, and pressuring their Syrian clients to focus on other enemies.

This report will chart the rise and fall of the Friends of Syria coalition, and the slow retreat of Western, Arab, and other nations from their multi-year campaign for regime change in Syria.

The Friends of Syria

In early 2012, foreign ministers and officials from some five dozen nations traveled to newly democratic Tunisia for what would be the largest-ever manifestation of international support for the Syrian opposition, then nearly a year into its uprising against President Bashar al-Assad’s authoritarian government.6 Inspired by the Libya Contact Group set up in March 2011 to overthrow Moammar al-Gaddafi, which was later renamed Friends of the New Libya, the officials in Tunisia decided to call themselves the “Friends of Syria.”7

The creation of the Friends of Syria “came immediately after Russia’s second veto in favor of Assad at the UN Security Council in February 2012, and was designed as a means for anti-Assad states to coordinate their efforts to support the opposition,” says Christopher Phillips, an associate fellow of Chatham House and the author of a well-received book on the diplomacy of the Syrian war.8

Phillips points to France as one likely driver of this attempt to emulate the Libyan model, but the United States handled much of the diplomatic heavy lifting, having floated the idea and begun to assemble a core group of countries soon after the veto.9 American efforts were “key to organizing the Friends of Syria,” said Frederic C. Hof, who, as Secretary of State Hillary Clinton’s senior adviser on Syrian affairs, was closely involved with the meetings. However, Hof also stressed that the United States’ influence in international diplomacy did not extend far on the battleground in Syria, or even among the anti-Assad exiles. Within the Syrian opposition, the rulers of Istanbul, Doha, and Riyadh held far more sway—and they coordinated as poorly with Washington as with each other.10

Indeed, from the inaugural meeting in Tunis, the Friends of Syria group would be “beset by the kind of problems that would doom international efforts to support the Syrian opposition,” Phillips tells me. “Regional states, led by Qatar but also Saudi Arabia, pushed for military intervention and arming the rebels, as seen in Libya, while Western states were wary of Islamist elements among the rebels and wanted a diplomatic solution.”11

At the Tunis meeting, Saudi Foreign Minister Saud al-Feisal called for arming the Syrian opposition, and Qatar urged Arab troops to get involved. These ideas were politely ignored or rejected by most countries, including otherwise hawkish Assad opponents in the West.12

A total of four Friends of Syria meetings were held in 2012:

- In Tunis on February 23, 2012,13

- In Istanbul on April 1, 2012,14

- In Paris on July 6, 2012,15 and

- In Marrakech on December 12, 2012.16

In practical terms, their main outcome was to streamline each country’s national policies around the demand for a political transition away from Assad’s rule, while voicing strong support for Syrian dissidents and calling for sanctions on the authorities in Damascus. For example, the Marrakech meeting, reportedly attended by the representatives of 114 nations, stated that Assad had “lost legitimacy and should stand aside to allow the launching of a sustainable political transition process in conformity with the Geneva communiqué,” referring to a document issued under UN supervision that summer. The meetings were also used to announce humanitarian aid and economic support for the Syrian opposition.17

The Friends of Syria conferences played a significant role in Syrian opposition politics, by conferring legitimacy on the Syrian National Council, a Turkey-based group that had sought support from the international community to overthrow Assad. In late 2012, the United States and its allies forced the largely ineffectual Syrian National Council to merge into a similar body known as the National Coalition, which was duly anointed by the Friends of Syria as “the legitimate representative of the Syrian people and the umbrella organisation under which Syrian opposition groups are gathering.”18

The thinking behind these moves was twofold. On the one hand, the Friends of Syria bloc was trying to strip Assad’s government of legitimacy. On the other hand, the nations involved wanted to nurture a cohesive and non-extremist opposition that could negotiate Assad’s resignation and step into the vacuum if, or when, he fell by other means.

Arming the Rebels

In parallel with the Friends of Syria meetings, the most hardline opposition backers were also funding and arming a growing guerrilla movement inside Syria.19 Weapons had begun trickling into Syria as early as 2011, through backdoor channels organized by Islamist networks, smugglers, merchants, and Bedouin clans, but also with increasingly overt support from Turkey, Qatar, and Saudi Arabia.20

In early 2012, Turkey and the Gulf States escalated their involvement in Syria. That summer, the Turkish government helped set up a joint cell in Adana to coordinate rival Qatari and Saudi efforts, but neither Turkish nor American pressure could keep the Gulf nations from seeking to subvert each other’s Syria policy.21 The campaign to arm the rebels devolved into a competitive and chaotic race to build client networks, with weapons worth billions of dollars sent into Syria over the coming year with little coordination or oversight.22

Syria was already devolving into sectarian warfare by late 2011, with regime control fraying across the Sunni countryside. The influx of massive foreign support over spring and summer 2012 led to an unprecedented proliferation of armed groups across Syria. Unable to cope with the rising tide of guerrilla attacks, the army was compelled to withdraw into safer areas, abandoning vast regions in northern Syria, and even some areas of Damascus and Aleppo, to rebel control.

It was around this time that the U.S. government began to get seriously involved in the insurgency. The CIA initially moved to monitor arms supplies provided by Turks, Qataris, and Saudis, seeking to steer resources away from anti-Western jihadis while also intercepting deliveries of high-powered weapons like anti-aircraft missiles. Increasingly, however, U.S. officials began to facilitate and complement allied support by adding American training and equipment—first nonlethal, then lethal.23

As the war dragged on, Obama came under fire from a growing choir of interventionist voices in the media and Congress, as well as from his Friends of Syria allies, for holding back on major arms deliveries and not intervening militarily against Assad. In spring 2013, he hesitantly agreed to let the CIA organize its own arms pipeline under a Saudi-backed program known as Timber Sycamore.24 It quickly grew into one of the most expensive covert programs in CIA history, spending about a billion dollars per year by 2015.25

Arms program Timber Sycamore quickly grew into one of the most expensive covert programs in CIA history, spending about a billion dollars per year by 2015.

By this time it was evident that Arab Spring had become “a proxy war for various regional powers,” noted Derek Chollet, who at the time was Obama’s assistant secretary of defense for international security affairs. “We had partners who were just throwing all sorts of resources at the conflict,” Chollet told me in a 2016 interview, lamenting what he viewed as irresponsible decisions by some U.S. allies. “Many of those resources ended up in the wrong hands. It was very much in the spirit of ’the enemy of my enemy,’ and to some of our partners it didn’t matter if their support ended up with [the al-Qaeda-linked] Jabhat al-Nusra or other groups. So we spent a lot of time on trying to persuade them to support the moderate opposition and galvanizing the international community to empower the moderate groups.”26

Though the United States did eventually manage to impose some order on regional gunrunning efforts and dealt considerable damage to Assad’s regime, Washington was not able to tame the insurgency itself. Increasingly chaotic, it now hosted an array of radical jihadi groups.

Some Western and Syrian critics of Assad have argued that the militarization and Islamization of the uprising was an inevitable reaction to brutal repression, and that democratic activists represented the “original revolution.” But a vastly stronger Islamist movement begged to disagree, and as Syria continued its descent into sectarian civil war, such counterfactuals simply did not matter—the opposition was what it was, not what its backers would have liked it to be.

No matter how intensely many Syrian and foreign activists, policymakers, and diplomats disliked Assad—whose regime had always been corrupt and undemocratic, and was now also responsible for a growing list of war crimes—an insurgency of this type could never have garnered broad international support.

Fickle Friends

Indeed, as Syria slid deeper into civil war, the Friends of Syria fast become fewer. More than sixty nations had taken part in the group’s first conference in Tunis in February 2012, and even greater numbers attended the follow-up meetings in Istanbul, Paris, and Marrakech. It was the high point of international support for the Syrian opposition.

In those days, the Syrian government was reeling from the shock of the initial uprising, losing more men, equipment, and territory on a daily basis. 2012 saw rebels capture eastern Aleppo and subject central Damascus to a steady barrage of mortars and rockets, while a July 18 bombing killed several members of the regime’s senior security elite, businessmen moved their money abroad and the economy faltered, and young men started fleeing in great numbers to avoid conscription. Assad reached ever deeper into his repressive arsenal to cope with spiraling losses—in 2012, he first deployed artillery, then helicopters, then the air force, and finally ballistic missiles. Late that year, reports came that the government had started bringing chemical weapons out of storage, and 2013 saw Syria’s first confirmed nerve gas attacks, though Damascus denied responsibility.27

Even on the loyalist side of the war, many seem to have thought in 2012 that Assad would eventually fall from power or lose control over so much of Syria that his regime could no longer function as a national government. In my meetings with pro-government figures in Damascus last year, every person I asked pointed to 2012–2013 as the worst moment of the war for them.28 From the outside, too, Assad’s undoing looked like it would be only a question of time to an audience of analysts, journalists, and policymakers impressed by the recent toppling of authoritarian rulers in Tunisia, Egypt, and Libya. Perhaps understandably, but nevertheless erroneously, “policy [was] driven by the belief that the regime would be the latest falling ‘domino’ in the Arab Spring.”29

By mid-2012, U.S. diplomats were making contingency plans for an uncontrolled collapse of the Syrian government, with internal arguments for intervention now fueled by the idea the United States needed to get involved to steer events and limit regional spillover once Assad’s regime crumbled.30 As 2012 turned into 2013, Western, Turkish, and Arab foreign ministries were still confidently assuring their governments that Assad was on his way out.

But he wasn’t. By late 2013, Assad had instead checked opposition advances, stemmed the flow of regime defections, and shored up his hold on power in Damascus. Though the regular Syrian Arab Army had decayed and lost much of its pre-2011 power, Assad and his allies had instead mobilized a sprawling network of militias, including sectarian Alawite and Shia groups but also multiconfessional units, Sunni tribal forces, and others.31 The air force conducted a pitiless bombing campaign against rebel-held territories, nerve gas killed hundreds in the Damascus suburbs, and a forceful intervention of Hezbollah fighters shut down insurgent supply routes through northern Lebanon.32

Meanwhile, the Friends of Syria-endorsed democratic exiles floundered in the face of an Islamist-inflected sectarian insurgency whose commanders spurned Western demands for compromise and negotiations.33 Though some rebels made a point of promising democracy and minority rights, the largest groups were nearly all Islamists of some variety. Many had to be constantly managed and pressured by their foreign funders to steer clear of extremist dalliances, and some were full-blown salafi-jihadis, as hostile to all other governments as to Assad’s.34

Though the Syrian president was now widely reviled as a war criminal and held responsible for tens of thousands of civilian deaths, the likely alternatives seemed to be either stateless, jihadi-infested chaos or some sort of Talibanesque theocracy.

Though the Syrian president was now widely reviled as a war criminal and held responsible for tens of thousands of civilian deaths, the likely alternatives seemed to be either stateless, jihadi-infested chaos or some sort of Talibanesque theocracy.35 International enthusiasm for the opposition plummeted.

Since the Marrakech conference in December 2012, no more large-scale Friends of Syria conferences have assembled. Instead, starting with a meeting in Rome in February 2013,36 international anti-Assad activism carried on in the form of a smaller group of likeminded nations, which eventually became known as the “core group of the Friends of Syria” or the “London 11.”37

The new, slimmed-down pro-opposition meetings were usually attended by the foreign ministers of the United States, the United Kingdom, France, Germany, Italy, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Turkey, the United Arab Emirates, Jordan, and, often, Egypt. Most of these nations were deeply invested in the war against Assad and had provided at least some material support for the armed insurgency, though there were exceptions: Egypt was a hardline opposition backer until July 2013, when a coup d’état tipped Cairo closer to the pro-Assad camp,38 and although Germany had always been a major humanitarian donor, Chancellor Angela Merkel was far from the most militant of Assad’s opponents.39

However, as the war went on, even these governments’ enthusiasm began to fade and other, incompatible interests rose to the fore.

Fading Faith in Regime Change

“There were several attempts to ‘fix’ the problems within the anti-Assad states, including streamlining the Friends of Syria into the ‘London 11’, but it still never resolved the fundamental differences in approach,” says Christopher Phillips. “In the end, it was acknowledged by most that the rebels couldn’t win without U.S. military air intervention, but Obama would not.”40

A symbolic tipping-point arrived in the form of the so-called red line crisis of September 2013, when Obama opted for a deal with Russia to peacefully remove Assad’s chemical weapons instead of striking his regime to avenge a lethal chemical attack. Obama stands by the deal as the least bad of many terrible options, citing the removal of some 1,300 tons of toxic chemicals from the Syrian battlefield, but his opponents were furious at what they saw as a sign of weakness that gave the regime a new lease on life.41

At this point it was overwhelmingly clear that the Syrian opposition could not, on its own, fill the void if Assad were to be overthrown militarily. Obama appears to have viewed any intervention that would likely end with the United States owning another Afghan-style failed state as a wholly unacceptable proposition, and an intervention aiming to simply kick Assad out and leave an anarchic Syria to fester as equally bad or worse. Yet the White House would not abandon the goal of Assad’s removal, instead settling on the idea that a negotiated transition could be achieved if the Syrian government came under enough rebel pressure.

A first attempt at organizing Syrian-Syrian talks about a handover of power, the so-called Geneva II negotiations that took place in January and February 2014, failed completely and gave no reason to think that a constructive compromise was possible. Nevertheless, many in the U.S. administration, as well as most of America’s allies in the Friends of Syria sphere, kept pushing for deeper intervention, arguing that Assad would come around if he just felt enough pressure. Obama appeared skeptical, but clearly did not want to be seen to reward the Syrian regime for its obstructionist tactics and abuse of international humanitarian law. And so U.S. Syria policy simply floundered on after the Geneva II failure—an ongoing low-level intervention unhappily searching for its own ulterior purpose, overseen by a president that did not seem to believe in what he was doing.

In summer 2014, the rise of the Islamic State refocused attention on the extremist menace growing in now-stateless parts of Syria.42 It led to the creation of a U.S.-led coalition striking the jihadis in Syria, but explicitly barred from targeting pro-Assad forces. The United States was now more reluctant than ever to see Damascus fall, fearing that a government collapse would provide the Islamic State with even more ungoverned space in which to operate.

Counterintuitively, for the Friends of Syria and a host of pro-opposition D.C. think tanks, this conclusion transformed into yet another argument for boosting the insurgency. The “last thing we want to do is to allow [jihadis] to march into Damascus,” said CIA Director John Brennan in March 2015. According to Brennan, Assad had to remain in power for now to allow for a negotiated solution, but that could only happen with sustained military pressure and an opposition amenable to compromise. “That’s why it’s important to bolster those forces within the Syrian opposition that are not extremists,” Brennan said.43

Official U.S. strategy was now to weaken Assad so much that he would agree to give up power, yet not so much that civilian or military institutions broke down or large cities were overrun by jihadis. But Syria was no computer game. The CIA and its on-the-ground implementers, an unwieldy cohort of rival regional intelligence bosses and rebel fixers, could not fine-tune insurgent activity to achieve predictable effects, nor could they rewrite the social and ideological landscape of rebel-held Syria by remote control.

It wasn’t that sending guns across the border was an ineffectual tactic. To the contrary, enough such support could almost certainly have destroyed the Syrian regime and killed Assad—had that been the purpose, had the costs been deemed acceptable. But using a chaotic, hundred-headed Sunni guerrilla force to tweak the Syrian president’s personal cost-benefit analysis of a political transition was like trying to perform heart surgery with a chainsaw, and blood soon spurted all over the map.

Using a chaotic, hundred-headed Sunni guerrilla force to tweak the Syrian president’s personal cost-benefit analysis of a political transition was like trying to perform heart surgery with a chainsaw, and blood soon spurted all over the map.

In early 2015, the Gulf States and Turkey sent a stream of no-questions-asked ammunition crates into northern Syria, alongside quality anti-tank rockets released by the United States. Duly empowered, the rebels quickly smashed through government lines. The Syrian regime seemed exhausted and unable to stop the insurgents from burrowing into its flanks, but, even then, Assad showed no inclination to negotiate, apparently viewing the war as an existential life-or-death battle.44

Over spring and summer 2015, the northwestern cities of Idlib and Jisr al-Shughour were taken by an Islamist force spearheaded by al-Qaeda fighters, while, in the east, Palmyra was captured by the Islamic State.

For some of the Friends of Syria, this was fine: Turkey and Qatar had always had a high tolerance for jihadism, and both they and the Saudis now wanted Assad gone at almost any cost.45 But in Western capitals and in some Arab states, other calculations applied. Behind the scenes, defense and intelligence analysts were sounding the alarm, warning that Syria was at risk of turning into a permanent jihadi safe haven on Europe’s doorstep.

Publicly, the White House continued to espouse a hard line against Assad and was swiftly taken to task in the media whenever an administration official wavered on the issue of his removal,46 but faith in the CIA’s ability to find that sweet spot of perfectly calibrated military pressure was clearly ebbing.

On September 30, 2015, Russian President Vladimir Putin unexpectedly stepped in to settle the U.S. administration’s internal debates by intervening militarily in Syria, alongside an Iranian-led expeditionary corps on the ground.47 The presence of Russian jets and air defenses seemed to preclude major U.S. intervention against Assad, whether under Obama or a future president.

Unlike the Americans, Russia and Iran did not anguish over the ideological inclination of their allies, had no plans to engineer a new opposition movement, and were not seeking to midwife a delicately balanced transitional government.

Unlike the Americans, Russia and Iran did not anguish over the ideological inclination of their allies, had no plans to engineer a new opposition movement, and were not seeking to midwife a delicately balanced transitional government. They wanted something much simpler: to crush the rebellion by empowering Assad’s already-existing regime, unencumbered by any constitutional or humanitarian niceties.

That was doable. The Russian-Iranian surge had soon tipped the scales back in Assad’s favor, and by spring 2016 the Syrian government was reclaiming lost lands. The United States and its allies tried to broker new truces and keep transition talks going in Geneva, but declined the invitation to counter-escalate on behalf of an opposition they no longer wanted to see in power. Instead, realizing that they could not realistically achieve their shared goal of ending Assad’s rule, members of the former Friends of Syria bloc began to drift apart to focus on more narrowly national interests.

In what follows, we will examine how this drift played out for each major actor or group of actors among the Friends of Syria: the United States, Europe, Turkey, Jordan, and the Gulf States.

The United States: “Very Little to Do with Syria”

Even before his election in November 2016, U.S. President Donald Trump had made clear that he didn’t trust the anti-Assad rebels and did not want to get involved in Syria. “If the Saudis are so concerned about Syria then they should go in themselves. Stop telling us to do their dirty work,” he wrote in October 2013, having already loudly protested the idea that Obama’s red line against chemical weapons should be enforced militarily. A year later, Trump mocked the idea that there were “moderate rebels” in Syria and professed incredulity that Obama would give them arms. “What the hell is he doing,” he tweeted. “Will turn on us.”48

If the Saudis are so concerned about Syria then they should go in themselves. Stop telling us to do their dirty work.

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) October 23, 2013

AGAIN, TO OUR VERY FOOLISH LEADER, DO NOT ATTACK SYRIA – IF YOU DO MANY VERY BAD THINGS WILL HAPPEN & FROM THAT FIGHT THE U.S. GETS NOTHING!

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) September 5, 2013

Do you believe that Obama is giving weapons to "moderate rebels" in Syria.Isn't sure who they are. What the hell is he doing.Will turn on us

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) September 20, 2014

Once in office, Trump bumbled about for a few months, but then began turning his tweets into policy. In late March 2017, Secretary of State Rex Tillerson declared that Assad’s future “will be decided by the Syrian people,” which was widely and correctly understood to mean that it would be decided by Assad himself, or Putin, or someone—but the United States would no longer spend blood or treasure to make the call.49

A week later, there was brief confusion as the United States sent a swarm of cruise missiles against a Syrian airfield in retaliation for an April 4 chemical attack.50 But Trump was soon back to form, determined to scale back U.S. involvement in Syria. “We don’t need that quicksand,” he told the Wall Street Journal.51

Soon after, the president shut down the CIA’s four-year old program to arm Syrian rebels, calling it “massive, dangerous, and wasteful.”52 Salary payments to CIA-vetted rebels in Syria are expected to end this winter. Although both the CIA and the Pentagon have continued to support groups that fight the Islamic State, these two lines of effort are kept separate, with anti-jihadi fighters banned from engaging Assad’s forces.53 It marked the end of U.S. attempts to overthrow Assad militarily.

“As far as Syria is concerned, we have very little to do with Syria, other than killing ISIS,” Trump explained at a September 8 press conference with the emir of Kuwait.54

Opinion on Trump’s Syria policy is predictably split. Some in the American political establishment fume over what they see as humiliation at the hands of Vladimir Putin, and as a blow to U.S. prestige and influence in the Middle East. Others view Russia’s attempt to lead the war to a Moscow-friendly conclusion as an opportunity to disentangle America from an intractable problem, allowing the United States to spend its political capital on more productive endeavors.

Trump’s dismantling of the Obama-era regime change policy has undoubtedly created new opportunities for diplomatic deal-making at the opposition’s expense, since American and Russian goals in Syria are no longer fundamentally irreconcilable. Though the United States has had several opportunities to act as a spoiler for Syrian regime interests, including by seizing territory in eastern Syria, it has so far turned down these opportunities and allowed things to take their course, while engaging diplomatically with Russia when and where it seems productive. These efforts have so far yielded a de-escalation deal for southern Syria, but it is low on detail and high on problems, and whether it can be implemented in a stable fashion remains to be seen.55 In particular, Iran’s role in Syria continues to irk American policymakers and may trigger new conflicts down the line.

The Europeans: Adjusting to America

Among European Union members, only France and the United Kingdom have really put their shoulder to the wheel of Syria’s revolution, though Germany and several other EU governments play a political or humanitarian role.

“The UK and France got involved for different reasons,” says Christopher Phillips. “What they shared was a sense of confidence after the ‘success’ of Libya in late 2011, and both Sarkozy and Cameron initially hoped to replicate that success in Syria, believing they could direct the United States again. However, both were to learn that Obama saw Syria very differently,” he says.56

The Russian intervention and the election of Donald Trump have since ended any lingering Anglo-French hopes for a U.S.-led intervention in Syria. Both countries have since fallen in line with the new American position.

Long Europe’s most hawkish opposition backer, France’s May 2017 election of Emmanuel Macron has brought swift changes in that country’s diplomatic posture. The new president began backpedaling on the issue of Assad’s resignation in June, saying, “nobody has shown me a legitimate successor,” and he later proposed a new international contact group to discuss Syria.57 But in practice, there are few new ideas on the table, and what is being presented as a grand, Parisian diplomatic push is really just France moonwalking away from its own unsustainable policies in the hope that it will look like forward motion.

What is being presented as a grand, Parisian diplomatic push is really just France moonwalking away from its own unsustainable policies in the hope that it will look like forward motion.

On one issue, Macron has hardened his approach to Assad’s regime, promising that Paris will tolerate no use of chemical weapons and may even launch unilateral French air strikes if that happens, with or without American support. Macron claims to have made progress on the chemical weapons issue in talks with Putin, without providing any details.58

The United Kingdom’s Theresa May has kept a lower profile. However, it was always clear that London wouldn’t fight the war alone. In a radio interview in late August, Foreign Secretary Boris Johnson avoided the question to the best of his ability, but was finally forced to say that the future of the Syrian president is ultimately up to the Syrian people, and that Assad, though he really ought to resign, is free to “stand in a democratic election.”59 While this means nothing in particular, all are invited to read between the lines.

“To save face they couldn’t roll back immediately, but it is quite clear that the ground has shifted and they need to adjust their policies accordingly,” says Christopher Phillips. “Some I have spoken to in the Foreign and Commonwealth Office still claim they are working towards a transition that doesn’t involve Assad but I’m fairly confident this is an official line and most can’t see it happening.”60

Starting in late 2016, the EU has tried to dangle reconstruction funding as a carrot in front of Assad, arguing that richer countries could buy him off with promises of welfare for his people.61 This is a self-evidently stillborn strategy, and one should probably credit European diplomats with understanding that. In practice, the EU’s cash-for-transition scheme is a fig leaf intended to allow Europeans to save face as they beat a retreat from coercive diplomacy into a much less demanding political posture, which consists in passively offering trades they know Assad won’t accept while acquiescing to Syria’s Baathist restoration.

Turkey: Owns an Opposition, Unsure What to Do with It

In 2016, Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan was finally forced to admit that he had been juggling a few too many balls. His interventionist attitude to Syria had given him nothing but grey hairs, and he was now plagued by multiple crises at home.62

In 2014, the United States intervened against the Islamic State. As part of their intervention, the Americans began supporting the People’s Protection Forces, or YPG—a Syrian offshoot of the Kurdistan Workers’ Party, or PKK, which wages war on the government in Turkey. From Ankara’s horizon, this was a strategic disaster. The rise of a U.S.-backed, pro-PKK self-government in northern Syria quickly overtook Assad as Turkey’s main issue of concern.63 Then, in 2015 and 2016, Russia’s intervention effectively ended Turkish hopes of regime change in Damascus.

Although Russia’s entry into the conflict brought considerable tension and ended up constraining Erdogan’s freedom of action, it also cleared up Turkey’s hopelessly tangled list of national priorities. Once Ankara recognized that overthrowing Assad was out of the picture, what remained was to focus on the Kurds, the jihadis, and the refugee crisis—in short, on the long-term management of Turkish influence among the competing forces on its southern border.

Having invested so much in the opposition, Erdogan could be certain to remain a key player in the conflict—just on a losing trajectory instead of a winning one. In spring 2016,he decided to seek a compromise with Russia, in the hope that Moscow would be open to pragmatic solutions for Turkey’s border woes.

As part of a larger overhaul of its crisis-ridden foreign policy, Turkey started to modify its Syria policies in mid-2016.64 Erdogan suddenly made good with Russia after a period of conflict, and then negotiated a deal with Moscow that saw Turkish troops intervene northeast of Aleppo in August 2016. The intervention left Ankara in charge of a chunk of territory that was largely worthless on its own, but which cut Syrian Kurdish lands in half.65 Russia pressed on, however, forcing Turkey to slowly surrender other areas of interest. After a long regime siege of eastern Aleppo, Erdogan ended up reluctantly facilitating the insurgent enclave’s December 2016 capitulation, which saw thousands of rebels and their families exit the city.66

The Aleppo deal came just after Trump’s election, seen as another nail in the coffin for the Syrian opposition. Erdogan then opted to deepen his engagement with the pro-Assad side by commencing a new peace process with Russia and Iran in the Kazakh capital of Astana.67

Turkey’s all-overriding priority in Syria is ”to prevent a Kurdish corridor and a Kurdish self-rule next to its borders,” says Cengiz Çandar, a Turkish Middle East expert and veteran journalist. “In order to achieve that objective and given the unchangeable American commitment, it moved closer to Russia-Iran. The deal reached on Aleppo with Russia at the expense of Turkey’s diminishing support for the Syrian opposition was a milestone. Astana constituted a major shift in the Turkish Syria policy, as well.”68

But Turkey’s strategic assets continued to crack and crumble.69 In January 2017, jihadis attacked Ankara’s rebel allies in Idlib and went on to seize northwestern Syria’s main border crossing in July 2017.70 Turkish intelligence has tried to rally other rebels against the jihadi takeover, so far with limited success.71

In September, the Astana trio declared Idlib to be a de-escalation zone that would be internally policed by Turkish troops.72 With jihadis in charge of much of the area this seemed a tall order, but Ankara rallied its rebel allies for a cross-border operation in early October 2017, attempting to compel the jihadis to accept a Turkish presence without full-blown conflict.73 Turkey appears to be trying to insulate itself against a continued refugee influx, and may also want to trade Idlib’s pacification for Russian measures to control the nearby Kurdish Efrin enclave.74 In a longer perspective, Ankara may well consider areas seized in northern Syria as assets to be swapped for action against the PKK.

Whatever the case, it is clear that Ankara’s priorities relate mainly to domestic interests, and although Turkey remains the most important supporter of Syria’s northern insurgency, the non-jihadi segments of the opposition are now being transformed into a proxy border guard rather than a force for regime change. Several CIA-vetted and Turkish-backed groups that have refused to abide by the de-escalation deal and opted to continue attacking Syrian army positions alongside jihadi fighters saw themselves stripped of support in the past few months.75

Though the Turkish government continues to complain over what it perceives as a U.S. betrayal, both in the struggle over Syria and in its war on the PKK, Recep Tayyip Erdogan now seems reduced to raking chestnuts out of the fire under Kremlin oversight.76 “The deal reached for establishing control for transforming Idlib as a de-escalation zone is the last link in the chain in which Turkey placed itself more under the Russian umbrella,” argues Candar.77

It is an awkward position for Erdogan, in which he is forced to balance the anti-Assad opposition that remains his main source of leverage in Syria against the pro-Assad demands of his Russian and Iranian partners in the Astana peace process.78 So far, Turkey has little to show for its new strategy, but with the United States losing interest and his rebel allies losing the war, Erdogan lacks attractive options. He seems to have concluded that Turkey’s best bet is to simply muddle through, and that giving in to a hard Russian bargain is ultimately going to be less damaging than to continue throwing good money after bad in northern Syria.

To be sure, he needs to stay involved. His country shares a porous 822-kilometer border with Syria and hosts more than three million refugees from the war: Turkey couldn’t insulate itself from Syrian politics even if it wanted to.

Jordan: Unsentimental Pragmatism and Border Woes

The Kingdom of Jordan entered the war against the Syrian government with some trepidation, concerned with its own security but also mindful of its regional alliances, having long depended on Western and Arab largesse to plug the holes in its budget and ensure internal stability.

However, U.S.-led attempts to channel support to vetted rebels through Amman and build a moderate, cohesive force in southern Syria met with limited success.79 The southern rebels failed to unite, could not keep jihadis out, and Assad didn’t fall.

Having received hundreds of thousands of refugees and witnessed increasing jihadi ferment inside the kingdom, Amman was already frustrated with the way the war was going by 2014. The one-two punch of Iraq’s near-collapse at the hands of the Islamic State that summer and the Russian intervention in Syria in 2015 persuaded the kingdom to change course, getting out in front of its American and Gulf Arab allies to refocus attention on border security.

In autumn 2015, Jordan began to limit support for rebels in the south, ordering its clients to train their fire on Islamic State targets and otherwise maintain current positions. By late 2016, Jordanian officials took a further step, signaling that they were open to resuming contacts with Assad and restart trade across the Nassib border crossing once stable security arrangements were in place along the border.80 In late summer and autumn 2017, Jordanian and Syrian officials exchanged pleasantries in the media,81 while American-Russian-Jordanian talks were held to defuse problems along the border, mostly at the rebels’ expense.82

Jordan has clearly given up on regime change in Syria, and many of its opposition clients seem resigned to this fact. Determined to secure and eventually normalize the situation on its northern border, the kingdom continues to work pragmatically with Russians and Americans to negotiate a new modus vivendi with Assad, showing no overt designs on southern Syria as long as stability is guaranteed.

When bad-cop Israel steps up its military posture and makes threatening noises on the Golan Heights, good-cop Jordan offers border access and trade income.

As part of this process, however, the kingdom has repeatedly tried to leverage its influence over the rebels to curtail Iran’s presence in southern Syria, telling Moscow and Damascus that this is key to broader reconciliation and perhaps also to resumed trade. While Amman has its own reasons to keep Iran away from the border, these demands appear to be informed by Israeli, Saudi, and American concerns: when bad-cop Israel steps up its military posture and makes threatening noises on the Golan Heights, good-cop Jordan offers border access and trade income. The question is, however, if Assad and Putin really can deliver a Hezbollah-free south?

The Gulf States: Fighting Each Other, Not Assad

The Arab Gulf states have since 2012 been the most generous supporters of the Syrian opposition, but the constant feuding of regional arch-rivals Qatar and Saudi Arabia also served to undermine insurgent cohesion.

Working closely with Turkey and the Muslim Brotherhood, Qatar was the insurgency’s primary funder until 2013, often channeling its support to hardline Islamists and disregarding U.S. pressure to seek out Western-friendly rebels. On at least two occasions, Qatar breached a stated U.S. red line by delivering shoulder-fired anti-aircraft missiles to rebel groups.83

In part to contain Qatar’s rising influence, Saudi Arabia stepped up its own efforts dramatically in late 2012 and early 2013, directing most of its support to less radical factions and becoming a favored partner of the CIA arms program.84 The United Arab Emirates also played a role in Syria, generally seen to be funding anti-Brotherhood, anti-Qatari factions and reinforcing Saudi efforts.85

The resignation of Qatar’s emir in June 2013, which was quickly followed by a Saudi- and Emirati-backed coup d’état against the Muslim Brotherhood government in Egypt, catalyzed a change in relations. The badly bruised regime in Doha tempered its challenge to Saudi primacy and relations stabilized somewhat, but crises continued to flare intermittently.

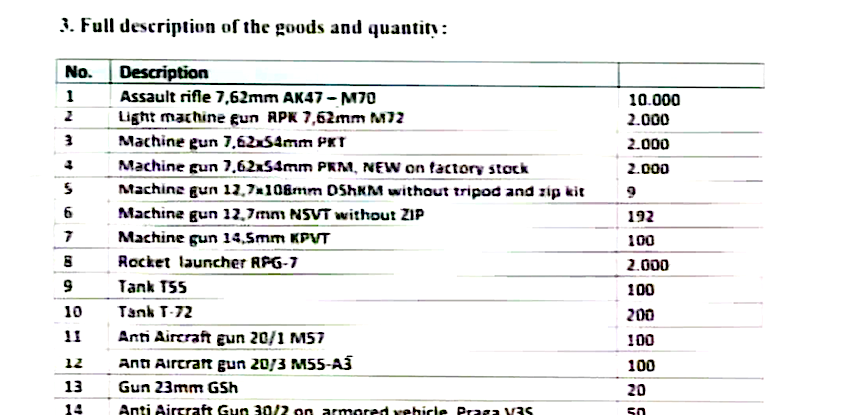

Much of the weaponry provided by the Gulf states to Syrian rebels was sourced from Eastern Europe. One team of journalists tracked a surge in purchases of surplus Soviet-era arms from countries like Croatia and the Czech Republic, amounting to some $1.4 billion between 2012 and 2016. Saudi Arabia accounted for two thirds of those purchases. In one case in 2013, a single end-user certificate issued by the Saudi Defense Ministry for a Serbian arms dealer requested more than 364 million pieces of ammunition, 300 tanks, 6,300 machine guns, and 10,000 Kalashnikov-style automatic rifles. Given that the Saudi army mostly uses Western-manufactured equipment, researchers assumed much of this material was likely intended for Syria, regardless of what the end-user certificate promised.86

Though paid for by the Arab oil monarchies, the arms shipments entered Syria through Turkey and Jordan, and to a lesser extent—until 2013—Lebanon. For reasons of evident geography, the Gulf states have always been forced to work through regional allies, and they also appear to have relied quite heavily on CIA coordination and facilitation.

The Turkish, Jordanian, and American withdrawal from the conflict since 2015-2016 therefore left “Qatar and, more important, Saudi Arabia with very little to work with,” concluded Emile Hokayem, a senior fellow with the International Institute for Strategic Studies, in late 2016.87

The constraints on Saudi Arabia may have been particularly important. Angered by U.S. rapprochement with Iran and unmoored by royal intrigues over succession, the Saudi regime has pursued an increasingly activist foreign policy in recent years, notably by launching a messy and inconclusive intervention in Yemen in 2015.88 Syria’s rebels had hoped to see similar hard-knuckle tactics against Assad, but any Saudi interest in escalation ended when Russia nudged the Turks and Jordanians to shift their policies. “Unable to shape the battlefield or steer diplomacy, a bruised and overextended Saudi Arabia has quietly pushed Syria down its list of priorities,” wrote Hokayem.89

Higher on that list of priorities, apparently, was Qatar. In June 2017, the old intra-Arab rivalry re-erupted in full force, for reasons not entirely clear to anyone.90 Saudis, Emiratis, Bahrainis, and Egyptians launched a financial and political boycott against Qatar, which turned to its key partner Turkey and—not exactly what the Saudis had hoped for—restored diplomatic relations with Iran.91

Months later, the Gulf remains locked in its bizarre stalemate, with recent American-led attempts to put the two blocs back on speaking terms having blown up over minuscule points of protocol.92

The Gulf princes will likely reconcile at some point, on some terms. But when they do, the future of Bashar al-Assad will hardly feature at the top of their agendas. “The Saudis don’t care about Syria anymore,” a senior Western diplomat told The Guardian. “It’s all Qatar for them. Syria is lost.”93

Or won, if you ask the other side.

Conclusion: Toward a Cold Peace with Assad

“We remain committed to the Geneva process and support a credible political process that can resolve the question of Syria’s future,” a U.S. State Department official told me earlier this year. “Ultimately, this process, in our view, will lead to a resolution of Assad.”94

That’s the official line: the United States wants Assad gone, but it is not going to pursue a military strategy to force him out: it will simply continue to call for continued peace talks in Geneva and claim that that’s really the same thing.95 It is not, of course. But in 2017, even those nations that long held out for a tougher line on Assad have fallen in behind Washington.

The Syrian opposition isn’t exactly being abandoned. Support continues to flow to many armed groups and the exiles have been kept on hand for whenever whatever deal may become feasible. As long as they adapt to their foreign sponsors’ agendas, Syrian opposition factions may even increase their relevance as the conflict proceeds—for example, Turkey will continue to have a need for local allies to contain its Kurdish enemies.

But there is no longer any serious international support for the opposition’s original raison d’être, the idea that still animates its members and leaders: namely to rid Syria of the Assad dynasty.

International diplomacy has moved on from that goal through incremental little acts of omission. The UN-backed Geneva Communiqué of 2012 demanded a mutually agreed-upon “transitional governing body” that would have allowed the opposition to veto Assad’s involvement.96 For years, this document was the foundation of all Syrian peace talks, but it has now quietly been phased out in favor of UN Security Council Resolution 2254, which was issued after the Russian intervention in 2015.97 Though UNSCR 2254 proposes an ambitious (or, absurd) plan for free elections, it is also much more muddled than the Geneva Communiqué and can more easily be molded to legitimize a transition that is, in fact, no transition at all.98

The most recent meeting of a Friends of Syria-style group of “likeminded nations” took place on the sidelines of the 72nd UN General Assembly in September 2017. It gathered seventeen foreign ministers, including representatives of all of the major anti-Assad stalwarts: Canada, Denmark, Egypt, European Union, France, Germany, Italy, Jordan, Netherlands, Norway, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Sweden, Turkey, United Arab Emirates, the United Kingdom, and the United States.

Together, they agreed that reconstruction funds for Syria will hinge on a “credible political process leading to a genuine political transition that can be supported by a majority of the Syrian people.” They also took the opportunity to insist on “full implementation of UNSCR 2254” and called for “strong and effective participation in meaningful negotiations by credible representatives of the Syrian opposition.” But the name “Assad” was not mentioned.99

In a press conference after the meeting, U.S. Acting Assistant Secretary of Near Eastern Affairs David Satterfield was asked what this actually means and whether the Syrian president could remain in office.

“It is a credible political process that is required that is the key,” Satterfield said. “The outcome to that process may be protracted, but it’s the process itself that’s the key to unlocking the door, not the actual outcome of the process.”100

You no longer need to read between the lines to get it. It’s right there, on the line. As far as the former Friends of Syria are concerned, the war to overthrow Bashar al-Assad is over.

Notes

- Ben Hubbard, “Syrian War Drags On, but Assad’s Future Looks as Secure as Ever,” New York Times, September 25, 2017, https://www.nytimes.com/2017/09/25/world/middleeast/syria-assad-war.html.

- Aron Lund, “Syria: East Ghouta Turns on Itself, Again,” The Century Foundation, May 1, 2017, https://tcf.org/content/commentary/syria-east-ghouta-turns/; Sam Heller, “Aleppo’s Bitter Lessons,” The Century Foundation, January 27, 2017, https://tcf.org/content/report/aleppos-bitter-lessons/; Aron Lund, “Pivotal point in eastern Syria as Assad breaks key Islamic State siege,” IRIN News, September 4, 2017, https://www.irinnews.org/analysis/2017/09/04/pivotal-point-eastern-syria-assad-breaks-key-islamic-state-siege; Aron Lund, “Can a deal in Astana wind down the six-year Syrian war?,” IRIN News, May 5, 2017, https://www.irinnews.org/analysis/2017/05/05/can-deal-astana-wind-down-six-year-syrian-war.

- One report noted more than 160 military flights shipping military equipment to Syria on behalf of Qatar, Saudi Arabia, and Jordan from January 2012 until March 2013. One expert said a “conservative estimate of the payload of these flights would be 3,500 tons of military equipment.” – C. J. Chivers and Eric Schmitt, “Arms Airlift to Syria Rebels Expands, With Aid From C.I.A.,” New York Times, March 24, 2013, www.nytimes.com/2013/03/25/world/middleeast/arms-airlift-to-syrian-rebels-expands-with-cia-aid.html.

- Roula Khalaf and Abigail Fielding Smith, “Qatar bankrolls Syrian revolt with cash and arms,” Financial Times, May 16, 2013, ig-legacy.ft.com/content/86e3f28e-be3a-11e2-bb35-00144feab7de#axzz4v9RYFIiY.

- Mark Mazzetti, Adam Goldman, and Michael S. Schmidt, “Behind the Sudden Death of a $1 Billion Secret C.I.A. War in Syria,” New York Times, August 2, 2017, https://www.nytimes.com/2017/08/02/world/middleeast/cia-syria-rebel-arm-train-trump.html; David Ignatius, “What the demise of the CIA’s anti-Assad program means,” Washington Post, July 20, 2017, https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/what-the-demise-of-the-cias-anti-assad-program-means/2017/07/20/f6467240-6d87-11e7-b9e2-2056e768a7e5_story.html.

- Steven Lee Myers, “Nations Press Halt in Attacks to Allow Aid to Syrian Cities,” New York Times, February 24, 2012, www.nytimes.com/2012/02/25/world/middleeast/friends-of-syria-gather-in-tunis-to-pressure-assad.html.

- “Statement from the conference Chair Foreign Secretary William Hague following the London Conference on Libya,” United Kingdom Foreign and Commonwealth Office, March 29, 2011, https://www.gov.uk/government/news/london-conference-on-libya-chairs-statement; “Conference in Support of the New Libya,” French Presidency, September 1, 2011, available on NATO website, www.nato.int/nato_static/assets/pdf/pdf_2011_09/20110926_110901-paris-conference-libya.pdf.

- “I think it was France’s idea,” Phillips says on the origins of the group’s creation, “to replicate the Friends of Libya diplomatic grouping in Syria, with many believing at the time that the Libya intervention had been successful and could be copied in Syria.” Christopher Phillips, interview with the author by email, September 2017. Phillips’s book, Battle for Syria: International Rivalry in the New Middle East, was published by Yale University Press in 2016.

- Rajeev Syal, “Clinton calls for ‘friends of democratic Syria’ to unite against Bashar al-Assad,” Guardian, February 5, 2012, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2012/feb/05/hillary-clinton-syria-assad-un.

- Frederic C. Hof, senior fellow in the Rafik Hariri Center for the Middle East in the Atlantic Council, interview with the author by email, July 2013.

- Christopher Phillips, interview with the author, 2017.

- Andrew Rettman, “‘Chaotic’ meeting exposes divisions on Syria,” EU Observer, February 24, 2012, https://euobserver.com/foreign/115376.

- “Chairman’s Conclusions of the International Conference of the Group of Friends of the Syrian People, 24 February,” U.S. Department of State, https://2009-2017.state.gov/r/pa/prs/ps/2012/02/184642.htm.

- “Chairman’s Conclusions Second Conference Of The Group Of Friends Of The Syrian People, 1 April 2012, Istanbul,” Turkish Foreign Ministry, www.mfa.gov.tr/chairman_s-conclusions-second-conference-of-the-group-of-friends-of-the-syrian-people_-1-april-2012_-istanbul.en.mfa.

- “Friends of Syrian People: Chairman’s conclusions,” United Kingdom Foreign and Commonwealth Office, https://www.gov.uk/government/news/friends-of-syrian-people-chairmans-conclusions.

- “The Fourth Ministerial Meeting of The Group of Friends of the Syrian People,” ReliefWeb, https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/Chairman’s conclusions.pdf.

- “The Fourth Ministerial Meeting of The Group of Friends of the Syrian People,” op. cit.; Phil Sands, “US recognises Syrian opposition coalition,” The National, December 13, 2012, https://www.thenational.ae/world/mena/us-recognises-syrian-opposition-coalition-1.405761; “Geneva Communiqué,” United Nations, June 30, 2012, www.un.org/News/dh/infocus/Syria/FinalCommuniqueActionGroupforSyria.pdf.

- On the role of the Friends of Syria meetings in promoting the Syrian National Council, see Aron Lund, Divided They Stand: An Overview of Syria’s Political Opposition Factions, FEPS, 2012, available on www.feps-europe.eu/en/publications/details/149. On U.S. pressure on the Syrian National Council to merge into the National Coalition, see Neil MacFarquhar and Michael R. Gordon, “As Fighting Rages, Clinton Seeks New Syrian Opposition,” New York Times, October 31, 2012, www.nytimes.com/2012/11/01/world/middleeast/syrian-air-raids-increase-as-battle-for-strategic-areas-intensifies-rebels-say.html. The Marrakech meeting in December 2012 transferred recognition by the Friends of Syria from the Syrian National Council to the National Coalition. See “The Fourth Ministerial Meeting of The Group of Friends of the Syrian People,” op. cit.

- Aron Lund, “Stumbling into civil war: The militarization of the Syrian opposition in 2011,” in AMEC Insights Volume 2, pp. 2-24, Afro-Middle East Center, 2015.

- Turkish-Qatari support seems to have arrived early on and was channeled through Islamist networks that included Muslim Brotherhood figures moving guns from civil-war Libya. Saudi Arabia mobilized Islamist allies, too, but was wary of the insurgency’s spiraling radicalism and distrusted the Muslim Brotherhood in particular. For example, non-Islamist Lebanese politicians were enlisted to move guns across the Lebanese and Turkish borders already in late 2011, in an operation that was “beyond any doubt planned under the supervision of the Saudi secret services.” See Bernard Rougier, The Sunni Tragedy in the Middle East: Northern Lebanon from al-Qaeda to ISIS, Princeton University Press, 2015, p. 178.

- Regan Doherty and Amena Bakr, “Exclusive: Secret Turkish nerve center leads aid to Syria rebels,” Reuters, July 27, 2012, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-syria-crisis-centre/exclusive-secret-turkish-nerve-center-leads-aid-to-syria-rebels-idUSBRE86Q0JM20120727.

- “Saudi Arabia and Qatar funding Syrian rebels,” Reuters, June 23, 2012, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-syria-crisis-saudi/saudi-arabia-and-qatar-funding-syrian-rebels-idUSBRE85M07820120623.s; Khalaf and Fielding Smith, 2013, op. cit.

- Eric Schmitt, “C.I.A. Said to Aid in Steering Arms to Syrian Opposition,” New York Times, June 21, 2012, www.nytimes.com/2012/06/21/world/middleeast/cia-said-to-aid-in-steering-arms-to-syrian-rebels.html; Eric Schmitt and Helene Cooper, “Stymied at U.N., U.S. Refines Plan to Remove Assad,” New York Times, July 21, 2012, www.nytimes.com/2012/07/22/world/middleeast/us-to-focus-on-forcibly-toppling-syrian-government.html; “Syrian Rebels Get Missiles,” Wall Street Journal, October 17, 2012, https://www.wsj.com/articles/SB10000872396390443684104578062842929673074; Michael R. Gordon, “U.S. Steps Up Aid to Syrian Opposition, Pledging $60 Million,” New York Times, February 28, 2013, www.nytimes.com/2013/03/01/world/middleeast/us-pledges-60-million-to-syrian-opposition.html; C. J. Chivers and Eric Schmitt, “Arms Airlift,” 2013, op. cit.; David S. Cloud and Raja Abdulrahim, “U.S. has secretly provided arms training to Syria rebels since 2012,” Los Angeles Times, June 21, 2013, articles.latimes.com/2013/jun/21/world/la-fg-cia-syria-20130622.; Karen DeYoung, “Congressional panels approve arms aid to Syrian opposition,” Washington Post, July 22, 2013, https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/national-security/congressional-panels-approve-arms-aid-to-syrian-opposition/2013/07/22/393035ce-f31a-11e2-8505-bf6f231e77b4_story.html.

- DeYoung, 2013, op. cit.; Mark Mazzetti and Matt Appuzzo, “U.S. Relies Heavily on Saudi Money to Support Syrian Rebels,” New York Times, https://www.nytimes.com/2016/01/24/world/middleeast/us-relies-heavily-on-saudi-money-to-support-syrian-rebels.html.

- Greg Miller and Karen DeYoung, “Secret CIA effort in Syria faces large funding cut,” Washington Post, June 12, 2015, https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/national-security/lawmakers-move-to-curb-1-billion-cia-program-to-train-syrian-rebels/2015/06/12/b0f45a9e-1114-11e5-adec-e82f8395c032_story.html; Mazzetti, Goldman, and Schmidt, 2017, op. cit.

- Author’s interview with Derek Chollet, 2016.

- “United Nations Mission to Investigate Allegations of the Use of Chemical Weapons in the Syrian Arab Republic,” final report, December 2013, United Nations, https://unoda-web.s3.amazonaws.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/report.pdf.

- For some impressions from that trip to Damascus, see Aron Lund, “Meeting Bashar al-Assad,” Hufvudstadsbladet, November 20, 2016, https://www.hbl.fi/artikel/for-our-international-readers-meeting-bashar-al-assad.

- Christopher Phillips, Battle for Syria: International Rivalry in the New Middle East, Yale University Press, 2016, p. 77.

- U.S. officials feared, in particular, that Syria’s highly potent chemical weapons arsenal could be used by the government in a last-ditch defense, or fall into insurgent hands. See Helene Cooper, “Washington Begins to Plan for Collapse of Syrian Government,” New York Times, July 18, 2012, www.nytimes.com/2012/07/19/world/middleeast/washington-begins-to-plan-for-collapse-of-syrian-government.html.

- Aron Lund, “Chasing Ghosts: The Shabiha Phenomenon,” in Michael Kerr and Craig Larkin (eds.), The Alawis of Syria, Hurst & Co., 2015.

- Human Rights Watch, “Syria: Aerial Attacks Strike Civilians,” April 10, 2013, https://www.hrw.org/news/2013/04/10/syria-aerial-attacks-strike-civilians; “United Nations Mission to Investigate Allegations of the Use of Chemical Weapons in the Syrian Arab Republic,” op. cit., though note, again, that the government never admitted responsibility; Anne Barnard, “Hezbollah Commits to an All-Out Fight to Save Assad,” New York Times, May 25, 2013, www.nytimes.com/2013/05/26/world/middleeast/syrian-army-and-hezbollah-step-up-raids-on-rebels.html.

- For a collection of my own writings on the fragmentation and radicalization of the Syrian opposition in 2012-2013, and on the refusal of major rebel factions to accept Friends of Syria-backed strategies for a negotiated solution, see Aron Lund, “Syrian Jihadism,” Swedish Institute for International Affairs, September 14, 2012, available on www.sultan-alamer.com/wp-content/uploads/77409.pdf; Aron Lund, “Syria’s Salafi Insurgents: The Rise of The Syrian Islamic Front,” UI Occasional Papers, Swedish Institute of International Affairs, March 2013, https://www.ui.se/globalassets/ui.se-eng/publications/ui-publications/syrias-salafi-insurgents-the-rise-of-the-syrian-islamic-front-min.pdf; Aron Lund, “The Non-State Militant Landscape in Syria,” CTC Sentinel, August 27, 2013, https://ctc.usma.edu/posts/the-non-state-militant-landscape-in-syria; Aron Lund, “Islamist Groups Declare Opposition to National Coalition and US Strategy [updated],” Syria Comment, September 24, 2013, www.joshualandis.com/blog/major-rebel-factions-drop-exiles-go-full-islamist/; Aron Lund, “Rebels Call Geneva Talks ‘Treason’,” Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, October 28, 2013, http://carnegie-mec.org/diwan/53451?lang=en/; Aron Lund, “The Politics of the Islamic Front, Part 3: Negotiations,” Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, January 16, 2014, carnegie-mec.org/diwan/54213?lang=en.

- Aron Lund, “Aleppo and the Battle for the Syrian Revolution’s Soul,” Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, December 4, 2012, carnegie-mec.org/publications/?fa=50234&solr_hilite=.

- For an example of one of the more materially credible (if not necessarily appealing) opposition state-building exercises in Syria, see Aron Lund, “The Syrian Rebel Who Tried to Build an Islamist Paradise,” Politico Magazine, March 31, 2017, www.politico.com/magazine/story/2017/03/the-syrian-rebel-who-built-an-islamic-paradise-214969.

- “Closed ministerial meeting on Syria,” Italian Foreign Ministry, February 28, 2013, www.esteri.it/mae/en/sala_stampa/archivionotizie/comunicati/20130228_riunione_siria.html.

- “‘London 11’ meeting on Syria,” United Kingdom Foreign and Commonwealth Office, October 22, 2013, https://www.gov.uk/government/news/london-11-meeting-on-syria.

- Hamza Hendawi, “Egypt seen to give nod toward jihadis on Syria,” AP/Yahoo News, June 16, 2013, https://www.yahoo.com/news/egypt-seen-nod-toward-jihadis-syria-202608813.html; Ben Lynfield, “Egypt shifts to open support for Assad regime in Syrian civil war,” Jerusalem Post, November 26, 2016, www.jpost.com/Middle-East/Egypt-shifts-to-open-support-for-Assad-regime-in-Syrian-civil-war-473693.

- At an April 4-5, 2017 fundraising conference in Brussels, Germany pledged to donate 1.3 billion euro for humanitarian aid to Syria, including areas held by both the opposition and the government. This was the largest single sum pledged by any nation and more than that promised by the United States, the United Kingdom, France, Italy, Sweden, and Spain combined. See the list of aid pledges from the Brussels conference at http://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/press/press-releases/2017/04/pdf/SyriaConf2017-Pledging-Statement_pdf. I would like to thank to Tobias Schneider, a German Middle East analyst, for valuable comments on Germany’s role.

- Christopher Phillips, interview with the author, 2017.

- Aron Lund, “Red Line Redux: How Putin Tore Up Obama’s 2013 Syria Deal,” The Century Foundation, February 3, 2017, https://tcf.org/content/report/red-line-redux-putin-tore-obamas-2013-syria-deal.

- Aron Lund, “Why Islamic State Is Losing, and Why It Still Hopes to Win,” The Century Foundation, June 17, 2016, https://tcf.org/content/report/islamic-state-losing-still-hopes-win.

- CIA Director John Brennan speaking at at the Council of Foreign Affairs, PBS, March 14, 2015, https://archive.org/details/KQED_20150314_070000_Charlie_Rose, See also Aron Lund, “What Does the U.S. Security Establishment Think About Syria?,” Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, March 20, 2015, carnegie-mec.org/diwan/59452?lang=en.

- Aron Lund, “Falling Back, Fighting On: Assad Lays Out His Strategy,” Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, July 27, 2015, carnegie-mec.org/diwan/60857?lang=en.

- Saudi Arabia had less of a tolerance for the Syrian Islamists, but was lashing out unpredictably in 2015 for reasons related to Iran as well as to Saudi royal politics. See Simrat Roopa, “Saudi Fears Spur Aggressive New Doctrine,” The Century Foundation, August 31, 2017, https://tcf.org/content/report/saudi-fears-spur-aggressive-new-doctrine.

- Hugh Naylor, “Kerry’s comments on Assad create uproar in the Middle East,” Washington Post, March 16, 2015, https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/middle_east/kerry-comments-on-assad-create-uproar-in-the-middle-east/2015/03/16/4a087930-cbe8-11e4-8730-4f473416e759_story.html.

- Aron Lund, “Not Just Russia: The Iranian Surge in Syria,” Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, May 23, 2016, carnegie-mec.org/diwan/63650.

- Tweets by Donald Trump: September 5, 2013, https://twitter.com/realDonaldTrump/status/375609403376144384; October 23, 2013, https://twitter.com/realDonaldTrump/status/393064582287069184; September 20, 2014, https://twitter.com/realDonaldTrump/status/513249345857413120. On the red line affair, see Lund, “Red Line Redux,” 2017, op. cit.

- “Press Availability With Turkish Foreign Minister Mevlut Cavusoglu,” U.S. Department of State, March 30, 2017, https://www.state.gov/secretary/remarks/2017/03/269318.htm.

- Thanassis Cambanis, “After Khan Sheikhoun, ’War Crimes’ Might Have No Meaning,” The Century Foundation, April 4, 2017, https://tcf.org/content/commentary/khan-sheikhoun-war-crimes-might-no-meaning/ Aron Lund, “Syria: Return of the red line,” IRIN News, April 26, 2017, https://www.irinnews.org/analysis/2017/04/26/syria-return-red-line.

- “WSJ Trump Interview Excerpts: China, North Korea, Ex-Im Bank, Obamacare, Bannon, More,” Wall Street Journal, April 12, 2017, https://blogs.wsj.com/washwire/2017/04/12/wsj-trump-interview-excerpts-china-north-korea-ex-im-bank-obamacare-bannon.

- Sam Heller, “America Had Already Lost Its Covert War in Syria—Now It’s Official,” The Century Foundation, July 21, 2017, https://tcf.org/content/commentary/america-already-lost-covert-war-syria-now-official; Tweet by Donald J. Trump, July 25, 2017, https://twitter.com/realDonaldTrump/status/889672374458646528.

- Sam Heller, “Desert Base Is Displaced Syrians’ Last Line of Defense,” The Century Foundation, September 8, 2017, https://tcf.org/content/report/desert-base-displaced-syrians-last-line-defense/.

- The press conference can be see on “President Donald Trump, Emir of Kuwait Hold WH Press Conference (Full) | NBC News,” NBC News YouTube Channel, September 7, 2017, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ByPNQWoxpHw.

- Gardiner Harris, “U.S., Russia and Jordan Reach Deal for Cease-Fire in Part of Syria,” New York Times, July 7, 2017, https://www.nytimes.com/2017/07/07/us/politics/syria-ceasefire-agreement.html; Aron Lund, “Opening Soon: The Story of a Syrian-Jordanian Border Crossing,” The Century Foundation, September 7, 2017, https://tcf.org/content/commentary/opening-soon-story-syrian-jordanian-border-crossing.

- Author’s interview with Christopher Phillips, 2017.

- “France’s Macron says sees no legitimate successor to Syria’s Assad,” Reuters, June 21, 2017, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-mideast-crisis-syria-france-idUSKBN19C2E7?il=0.

- “Discours d’Emmanuel Macron en ouverture de la Conférence des Ambassadeurs,” French Presidency, August 29, 2017, www.elysee.fr/videos/new-video-44; “Chemical weapons a red line in Syria, France’s Macron says,” Reuters, May 29, 2017, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-france-russia-syria-macron/chemical-weapons-a-red-line-in-syria-frances-macron-says-idUSKBN18P1OH.

- Boris Johnson interviewed by Mishal Hussein on BBC Radio 4, August 25, 2017.

- Author’s interview with Christopher Phillips, 2017.

- Richard Spencer, “EU offers cash to Assad regime for Syria peace deal,” The Times, December 3, 2016, https://www.thetimes.co.uk/article/eu-offers-cash-to-assad-regime-for-syria-peace-deal-w8shn8rjx.

- Aron Lund, “How Will the Failed Coup in Turkey Affect Syria?,” Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, July 28, 2016, carnegie-mec.org/diwan/64206.

- Aron Lund, “Turkey-Kurd feud distracts from Islamic State fight in Syria,” IRIN News, May 2, 2017, https://www.irinnews.org/analysis/2017/05/02/turkey-kurd-feud-distracts-islamic-state-fight-syria.

- Aron Lund, “The Algerian Connection: Will Turkey Change Its Syria Policy?,” Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, June 20, 2016, carnegie-mec.org/diwan/63847.

- Aron Lund, “After Murky Diplomacy, Turkey Intervenes in Syria,” Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, August 24, 2016, carnegie-mec.org/diwan/64398.

- Aron Lund, “The Slow, Violent Fall of Eastern Aleppo,” The Century Foundation, October 7, 2016, https://tcf.org/content/commentary/slow-violent-fall-eastern-aleppo; Sam Heller, “Aleppo’s Bitter Lessons,” The Century Foundation, January 27, 2017, https://tcf.org/content/report/aleppos-bitter-lessons.

- Aron Lund, “Staring Into Syria’s Diplomatic Fog,” The Century Foundation, January 6, 2017, https://tcf.org/content/commentary/staring-syrias-diplomatic-fog.

- Author’s interview with Cengiz Çandar, email, September 2017.

- Sam Heller, “Turkey’s ‘Turkey First’ Syria Policy,” The Century Foundation, April 12, 2017, https://tcf.org/content/report/turkeys-turkey-first-syria-policy/.

- Aron Lund, “Black flags over Idlib: The jihadi power grab in northwestern Syria,” IRIN news, August 9, 2017, https://www.irinnews.org/analysis/2017/08/09/black-flags-over-idlib-jihadi-power-grab-northwestern-syria.

- Aron Lund, “A Jihadist Takeover in Syria,” Foreign Affairs, September 15, 2017, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/syria/2017-09-15/jihadist-breakup-syria.

- “Final de-escalation zones agreed on in Astana,” Aljazeera English, September 15, 2017, www.aljazeera.com/news/2017/09/final-de-escalation-zones-agreed-astana-170915102811730.html.

- Aron Lund, “Turkey Intervenes in Syria: What You Need to Know,” IRIN News, October 9, 2017, https://www.irinnews.org/analysis/2017/10/09/turkey-intervenes-syria-what-you-need-know.

- “Turkey, Russia, Iran work on new de-escalation zone in Syria,” TASS, September 25, 2013, http://tass.com/world/967338.

- “’mom’ tuwaqqif daam baad fasail shamali souriya,” Enab Baladi, October 8, 2017, https://www.enabbaladi.net/archives/177026. The article mentions several Free Syrian Army-branded factions in the Idlib region: the Central Division (al-Firqa al-Wusta), the Free Idleb Army (Jaish Idlib al-Hurr), the Glory Army (Jaish al-Ezzah), and the Victory Army (Jaish al-Nasr)

- In January 2017, for example, Turkish Foreign Minister Mevlüt Çavuşoğlu warned of “a confidence crisis in the relationship” after “the U.S. chose a terrorist organization over its ally.” “Turkey ‘questions’ US use of İncirlik air base,” Hürriyet Daily News, January 4, 2017, www.hurriyetdailynews.com/turkey-questions-us-use-of-incirlik-air-base-.aspx?PageID=238&NID=108122&NewsCatID=338.

- Author’s interview with Cengiz Çandar, 2017.

- Aron Lund, “Can a deal in Astana wind down the six-year Syrian war?,” IRIN News, May 5, 2017, https://www.irinnews.org/analysis/2017/05/05/can-deal-astana-wind-down-six-year-syrian-war.

- Phil Sands and Suha Maayeh, “Syrian rebels get arms and advice through secret command centre in Amman,” The National, December 28, 2013, https://www.thenational.ae/world/syrian-rebels-get-arms-and-advice-through-secret-command-centre-in-amman-1.455590.

- Firas Kilani interviews Lt. Gen. Mahmoud Freihat, BBC Arabic YouTube channel, December 30, 2016, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=I8YSpBn86Ks; Lund, “Opening Soon,” 2017, op cit.

- Mohammed al-Momani interviewed on Sittoun Daqiqa, Jordanian Royal Television YouTube channel, August 25, 2017, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MIPA6ugARwk; “melaff al-maaber ala nar sakhina,” al-Watan, September 21, 2017, alwatan.sy/archives/120139.

- Harris, 2017, op. cit.; Heller, “Desert Base,” 2017, op. cit.

- Khalaf and Fielding Smith, 2013, op. cit.; Mark Mazzetti, C. J. Chivers, and Eric Schmitt, “Taking Outsize Role in Syria, Qatar Funnels Arms to Rebels,” New York Times, June 29, 2013, www.nytimes.com/2013/06/30/world/middleeast/sending-missiles-to-syrian-rebels-qatar-muscles-in.html.

- C. J. Chivers and Eric Schmitt, “Saudis Step Up Help for Rebels in Syria With Croatian Arms,” New York Times, February 25, 2013, www.nytimes.com/2013/02/26/world/middleeast/in-shift-saudis-are-said-to-arm-rebels-in-syria.html; Mazzetti and Appuzzo, 2016, op. cit.

- Author’s interviews with Syrian activists, 2014-2015.

- Lawrence Marzouk, ivan Angelovski, and Miranda Patrucic, “Making a Killing: The €1.2 Billion Arms Pipeline to Middle East,” OCCRP, July 27, 2016, https://www.occrp.org/en/makingakilling/making-a-killing.

- Emile Hokayem, “How Syria Defeated the Sunni Powers,” The New York Times, December 30, 2016, https://www.nytimes.com/2016/12/30/opinion/how-syria-defeated-the-sunni-powers.html.

- Simrat Roopa, 2017, op. cit.

- Hokayem, 2016, op. cit.

- Aron Lund, “As Arabs Bicker over Qatar, Assad Sees an Angle,” The Century Foundation, June 16, 2017, https://tcf.org/content/commentary/arabs-bicker-qatar-assad-sees-angle; Michael Wahid Hanna, “Don’t Let a Gulf Crisis Go to Waste,” The Century Foundation, July 25, 2017, https://tcf.org/content/commentary/dont-let-gulf-crisis-go-waste.

- Yaroslav Trofimov, “Turkey Sees Itself as Target in Saudi-Led Move Against Qatar,” Wall Street Journal, June 15, 2017, https://www.wsj.com/articles/turkey-sees-itself-as-target-in-saudi-led-move-against-qatar-1497519004; Sudarsan Raghavan and Erin Cunningham, “Qatar restores diplomatic ties with Iran despite demands by Arab neighbors,” Washington Post, August 24, 2017, https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/middle_east/qatar-restores-diplomatic-ties-with-iran-despite-demands-by-arab-neighbors/2017/08/24/9288e05c-6666-492f-8f32-bc68541c3867_story.html.

- “Qatar crisis: Saudi Arabia angered after emir’s phone call,” BBC, September 9, 2017, www.bbc.com/news/world-middle-east-41209610.

- Martin Chulov, “Victory for Assad looks increasingly likely as world loses interest in Syria,” The Guardian, August 31, 2017, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2017/aug/31/victory-for-assad-looks-increasingly-likely-as-world-loses-interest-in-syria.

- Author’s interview with U.S. State Department official, email, April 2017.

- On the Geneva talks, see Sam Heller, “Geneva Peace Talks Won’t Solve Syria—So Why Have Them?,” The Century Foundation, June 30, 2017, https://tcf.org/content/report/geneva-peace-talks-wont-solve-syria.

- “Geneva Communiqué,” United Nations, June 30, 2012, www.un.org/News/dh/infocus/Syria/FinalCommuniqueActionGroupforSyria.pdf.

- UN Security Council Resolution 2254, SC/12171, December 18, 2015, https://www.un.org/press/en/2015/sc12171.doc.htm.

- Aron Lund, “Everything you need to know about the latest Syria peace talks,” IRIN News, February 21, 2017, https://www.irinnews.org/analysis/2017/02/21/everything-you-need-know-about-latest-syria-peace-talks.

- “Joint Statement From the Ministerial Discussion on Syria,” Office of the Spokesperson, U.S. Department of State, September 21, 2017, https://www.state.gov/r/pa/prs/ps/2017/09/274356.htm.

- Transcript of David M. Satterfield’s briefing on Syria at the The Palace Hotel, New York, U.S. Department of State website, September 18 2017, https://www.state.gov/r/pa/prs/ps/2017/09/274238.htm.