Historically, Kurdish national identity, or Kurdayeti, has evolved as political transitions have ushered in new political elites. These new elites brought with them fresh ideas on how to define Kurdayeti and the social contract with Kurdish society. Over much of the past half-century, Iraqi Kurdish leaders framed new political projects in the context of their fights against a repressive central government in Baghdad. This momentum enabled the region to emerge as the center of gravity for Kurdish nationalism for most of the subsequent decades. Today, however, Iraqi Kurdistan is in a stalled transition, hostage to an obsolete order that fails to meet the expectations of a changing society. As a result, Iraqi Kurdistan’s role as the hub for the evolution of Kurdish nationalism is declining.

In the 1990s, Iraqi Kurdish leaders leveraged international support and the region’s natural resource wealth to establish a semiautonomous, albeit party-based, system of governance. The 2003 U.S. invasion of Iraq created an opportunity for Iraqi Kurdistan to consolidate its autonomy and to transition from a party-based political system to a parliamentary democracy. Expectations rose among Kurdish society—and the younger generation in particular, which had little memory of Saddam Hussein’s regime—for the introduction of a new social contract, one that would provide rights on the basis of citizenship rather than on party affiliation. In the aftermath of the war that began in 2003, Iraqi Kurdistan experienced some democratic and economic gains. But in recent years, Kurdish leaders have increasingly failed to adapt to changing societal expectations. Instead, these leaders, mostly members of the older generation and their relatives, have manipulated the past to justify their prolongation of the status quo. They have leveraged their historical roles (or those of their elder relatives) in fighting for Kurdish autonomy in order to compensate for their shortcomings in developing effective governance institutions.

As the gulf between Kurdish society and the leadership grew wider, some among the Kurdish leadership spearheaded an independence referendum, held in September 2017. The referendum represented a last-ditch attempt by some Iraqi Kurdish leaders, and in particular Masoud Barzani, then-president of the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG), to mobilize society through an ethnonationalist narrative that placed statehood at the center of Kurdayeti. It also came at a time when Kurdish leaders, fearful that their relevance toward the West would decline with the winding down of the war against the Islamic State, were seeking new political status. The referendum pushed the rivals of the Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP), including members of Goran and the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (the PUK), as well as the broader public opposed to the establishment parties, were pushed into an uncomfortable corner: backing the referendum meant supporting a Barzani-led bid for legitimacy and power, while opposing it carried the risk of being seen as anti-nationalist. The referendum not only failed to achieve independence, but also backfired by drawing international ire and provoking Baghdad to reinstate its authority in disputed territories and Iraqi Kurdistan’s airspace. This result convinced many Kurds that the leadership’s statehood-focused vision of Kurdayeti is obsolete, and cannot provide for the civil rights they have come to expect. Only a true political transition that makes way for new leaders proposing a new social contract can solve Iraqi Kurdistan’s impasse.

Only a true political transition that makes way for new leaders proposing a new social contract can solve Iraqi Kurdistan’s impasse.

The first part of this essay demonstrates that Kurdayeti has historically evolved as a function of political transitions. We outline key historical junctures across Kurdish-populated territories, and identify patterns among the transitions. We demonstrate how Iraqi Kurdistan emerged as the center of gravity for Kurdish nationalism in the mid- and late twentieth century, as a result of its leaders mobilizing society in a struggle for autonomy against Baghdad. The second part of the essay analyzes why Iraqi Kurdistan is at an impasse today, unable to complete the necessary political transition to a new order in line with contemporary realities. The final part outlines the consequences of the stalled transition, namely with respect to the eclipse of Iraqi Kurdistan as the hub for the evolution of Kurdayeti. While the leadership appears able to maintain its grip on power in the short term, its tactics alienate the population and provoke a widespread societal disengagement from politics. Only a minority of Iraqi Kurdish society continues to search for a way forward, despite the odds. As the gulf between Kurdish society and its leaders grows wider, the region will be more vulnerable to domestic turmoil and regional interference.

Kurdayeti in Political Transition

“Kudayeti,” which literally translates as “Kurdishness,” has been used for the past century to refer to Kurdish national identity.1 Kurdayeti has never been a static concept.2 Instead, it has repeatedly evolved at historical junctures, when new forces have supplanted established rulers. This is true of national identities of different groups and states all over the world, but is especially the case for a people—such as the Kurds—whose identity has evolved in absence of a recognized nation-state. New visions of Kurdayeti have emerged as the outcomes of political claims by new leaders, who mobilize society on the basis of a refreshed understanding of national identity and supplant established rulers. Each watershed in modern Kurdish history has produced a new order: new political elites, new forms of political organization, and new visions of Kurdayeti.

Each watershed in modern Kurdish history has produced a new order: new political elites, new forms of political organization, and new visions of Kurdayeti.

There are identifiable patterns to the transitions in Kurdish history. Since the nineteenth century, leadership turnovers have been tortuous, characterized by sudden leaps between prolonged stalemates. These patterns are a function of internal Kurdish dynamics, as well as of the external context. Regional or global conflicts and trends have at times provided platforms for new leaders to emerge and forge alliances with the middle class, youth, and other key segments of society. At other times, the external context has reinforced domestic stalemates. As the modern states that Kurds are a part of (Iran, Iraq, Turkey, and Syria) have changed their definitions of national identity, Kurdayeti has been repeatedly reshaped in response.3

Kurdayeti: A Brief Historical Perspective

The Ottoman Empire was the first platform for the emergence of contemporary Kurdish nationalism. In the 1870s, the Ottomans’ Tanzimat reforms empowered a new bureaucracy with few ties to the local population, undermining the authority of the hereditary prince. Disorder spread in the formerly princely territories of modern-day Iraqi Kurdistan and southeast Turkey. In the seats of the former Kurdish princes, “the strange, unfamiliar figure of the shaykhs arose to cast a new shadow of supreme authority over the disturbed land.”4 Sheikh Ubaydallah, a prominent religious and tribal leader from what is today southeast Turkey, was among the first to assert the Kurds as a “people apart.”5 He aimed to unite Kurdish sheiks across localities in the form of an independent state, leading a rebellion against the Ottomans in pursuit of this goal in 1879.6

The rise of nationalisms across the Ottoman Empire in the early twentieth century consolidated this sense of collective Kurdish identity.7 Then, in the wake of the collapse of the empire, a new class of Kurdish leaders, led by tribal and religious sheikhs, emerged in the struggle against the respective central governments and colonial powers—especially in the Kurdish-populated areas that became part of modern Iraq.8

By the 1930s, things were changing again, as some Kurdish leaders began mobilizing their nationalist agendas through political party structures. Among them was Mullah Mustafa Barzani, father of the current Kurdish leader, Masoud Barzani. From new bases in Iran, urban leaders who had been nurtured on a more progressive agenda than their religious predecessors prioritized governance and literacy over armed struggle, and mobilized support among the younger intelligentsia.9 The first independent Kurdish state was declared in Mahabad, Iran, in 1946, under the leadership of Qazi Muhammad, a well-educated judge from a distinguished family, and his Kurdish Democratic Party (KDP-I). Dependent on fickle Soviet support, the Republic of Mahabad collapsed less than a year after it was proclaimed. But the stage was set for a new era of Kurdayeti, with new nationalist leaders drawn from the intelligentsia.

Yet another transition was afoot, this time based in Iraq. After the failure in Mahabad, Mullah Mustafa founded, in Iraq, the Kurdish Democratic Party, later renamed the Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP).10 The KDP’s agenda was designed to appease both traditionalist and reformist elements, a balance that proved hard to strike. Kurdish political dynamics came to be defined by the tension between urban leftists—including Jalal Talabani—and Barzani’s conservatives and tribalists, who held greater control over the party’s fighting force. 11 In Sulaymaniyah, in eastern Iraqi Kurdistan, a faction of Maoist-inspired Kurdish nationalists emerged.12

In the middle of the twentieth century, the contemporary political landscape began to take shape. In 1975, the founding of the PUK, with Talabani at its helm, marked a break with the established order embodied in the KDP.13 Unlike the KDP, the PUK drew its leadership primarily from leftist groups, rather than from a single family, and began to develop affiliated organizations representing students, farmers, and other social groupings. The influence of leftist ideology on the Iraqi Kurdish movement continued across the border, leading students’ associations in Turkey to establish a new party, the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK), which recruited across the four corners of Kurdistan.

Iraqi Kurdistan as the Center of Gravity

In Iraq, Kurdish leaders were able to translate their military achievements into a sustainable political project and rally a generation of Iraqi Kurds behind it. A new order emerged in Iraqi Kurdistan, based on an autonomous region with semi-democratic institutions, and yet another vision of Kurdayeti.

Saddam Hussein’s aggression toward Iran in 1980 and invasion of Kuwait in 1991 offered the KDP and PUK, and their affiliated peshmerga (fighting forces), the chance to access regional and international support in their armed struggle. In the 1980s, alliances between Kurdish parties and central states seesawed: Iran supported Kurdish parties in launching attacks against Iraq, while the PUK sided with Saddam Hussein in the early part of the decade, as tensions grew between it and the KDP. Later, Saddam Hussein’s brutal reprisals against the Kurds displaced hundreds of thousands of Iraqi Kurds, driving them toward the Turkish border and into Iran. These attacks included, most infamously, the 1988 Al-Anfal campaign of the late 1980s, including the chemical attack in Halabja,14 and the regime’s crackdown on a Kurdish uprising in 1991. This displacement crisis drew unprecedented media attention to the plight of the Kurds and placed party leaders in the international spotlight. A new political class was born.

After the 1991 Kurdish uprising against Saddam Hussein’s forces (an event known in Kurdish as “Raparin”) and Iraq’s defeat in the Gulf War, Hussein’s forces withdrew from the Kurdish-populated north, and the United States enforced a no-fly zone over the area. Aided by this protection, Kurdish political parties were able to establish new self-governance institutions and transition from warriors to rulers. The parties strengthened and expanded their internal structures, including their politburos and local offices across Iraqi Kurdistan. They held elections, created the KRG, and began professionalizing their respective peshmerga military forces. Politburo leaders and guerrilla commanders assumed leadership positions in the new administration. Their participation in the fight against Saddam Hussein stood in as proof of their nationalist credentials and mobilized a generation of Iraqi Kurds to join their ranks. The peshmerga became a sacred symbol of the struggle against repression.

Although Iraqi Kurdistan’s leaders had been successful in the armed struggle, the experiment in self-rule tested them anew. In the mid-1990s, the KDP and PUK fought a civil war, splitting their historic achievement in half. Each side sought support against the other from external powers, with the PUK seeking support from Iran while the KDP resorted to striking a deal with Saddam Hussein to gain Iraqi help in driving the PUK out of Erbil. Although the United States brokered an uneasy truce to end the fighting in 1998, the region remained divided between two party-run administrations, with the KDP dominant in the western governorates of Erbil and Dohuk, and the PUK in the east, namely Sulaymaniyah governorate.15 Each party maintained and further developed control over its own affiliated security forces, intelligence agencies, patronage-based networks, and more—a legacy of party-based security and governance that continues to plague Iraqi Kurdistan’s institutions today.

The U.S. invasion of Iraq in 2003 offered the parties a chance to refresh their legitimacy and power. The 2005 Iraqi constitution recognized Iraqi Kurdistan as a federal region, and in the post-Saddam Hussein era, the Kurds became privileged partners of the United States, gaining unprecedented influence in Baghdad.16 In 2006, the KDP and PUK formally unified their administrations into a single KRG based in Erbil, appearing to turn a page away from the traumatic 1990s era of “brakuji”—a Kurdish term for internecine conflict that literally means killing of one’s brother.17

The stage was set for the emergence of Iraqi Kurdistan as a thriving parliamentary democracy. Elections were held, parliament emerged as a platform for debate, and civil society initiatives grew.18 A split within the PUK led to the creation in 2009 of a formidable opposition party, Goran. Goran challenged the KDP–PUK duopoly for the first time. Iraqi Kurdistan’s booming post-2003 economy, meanwhile, attracted Kurds from all parts of Kurdistan—as well as those in the diaspora—to move to the region that many saw as the best-developed example of Kurdish autonomy.19

But with so much blood spilled and so many lives invested in a system that hinged on party affiliation, the groundwork was also laid for the impasse that Iraqi Kurdistan is experiencing today. Thus, the history of Kurdayeti gives inspiration for its future evolution—but also explains why, given the current economic and political context, it is going through a period of immovability.

Manipulating the Past

Iraqi Kurdistan’s leaders continue to stake their political legitimacy on the basis of their past achievements in fighting for and building the foundations of the region’s autonomy. They rely on the past to compensate for their shortcomings in governance today. As Kurdayeti is increasingly reduced to an instrument of the leadership’s claim to power, it ceases to offer a shared sense of belonging for Kurdish society.

Iraqi Kurdistan’s leaders rely on the past to compensate for their shortcomings in governance today.

The leadership has redrafted history in its narrative of Kurdayeti. Many of those who were yesterday’s warriors promote a highly exclusivist narrative of Kurdayeti that paints them as the eternal protagonists of the nationalist struggle. In this narrative, those who did not participate in the founding of Kurdistan are not portrayed as characters with agency; rather, they are only passive beneficiaries of the current leadership’s achievements.

Major streets and universities in Kurdistan are named “Raparin,” after the 1991 uprising. Children grow up learning about the heroism of the peshmerga resistance against Saddam Hussein’s regime. But history books skip over how KDP–PUK fighting in the mid-1990s led to the deaths or displacements of thousands of Kurds and the reintroduction of Saddam Hussein’s forces into Kurdistan, only a few years after they had unilaterally withdrawn from the region in 1991. “We don’t place any emphasis in the curriculum on what happened in the 1990s (the civil war), because it was a negative experience,” said Pishtiwan Sadiq, the KRG’s minister of education, in June 2018. “There is a saying in Kurdish, that when you talk about those kinds of things, you re-boil the blood.”20 The leaders’ grip on institutions also allows them to de-historicize more recent memory in their favor. For instance, in 2018, the KRG Ministry of Education was exploring how to incorporate the September 2017 independence referendum into its human rights curriculum—presenting it as a win for human rights, despite its undeniable failure.

Many of Iraqi Kurdistan’s most established leaders leverage their pasts to justify their prolonged holds on power. For example, PUK politburo member Mala Bakhtiyar, in the face of growing public anger against the parties, said in January 2018 that even if the PUK were to lose the Kurdistan Region general elections in September of that year, the party would maintain its grip on power. “We will be the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan if we win one seat, and we will be the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan if we win 100 seats,” he said in comments to the media, adding that the PUK, like the KDP, has struggled for the Kurdish cause for decades, and as such has strong influence on the security forces and the peshmerga.21 The PUK announced it would hold its 2018 congress on March 5—the anniversary of Raparin—again emphasizing the achievements of the established leaders from the former generation.22

The manipulation of the past creates an intergenerational legitimacy gap, elevating those who played a role in the historical struggle for Kurdish autonomy, while delegitimizing the political preferences and ambitions of those who did not. This creates tensions at macro and micro levels. “We were strong people,” said Saadi, a sixty-year-old father in Erbil, illustrating how many elders view the contrast between the two age groups.

We grew up in brutal conditions. We were ready to fight at any time and it made us love Kurdistan more. Today’s young people belong to a generation of “zero” that has lost the sense of collective interest…. Young Kurds would rather go to Germany to peel potatoes. Here, none of them would accept to be a waiter in a restaurant. How would you explain that? Simply: they are spoiled kids!23

“We were ready to fight at any time,” said Saadi, sixty years old. “Young Kurds today would rather go to Germany to peel potatoes.”

Similarly, Azad, a Kurdish man in his fifties, viewed young people as being less ready to sacrifice. “During the 1990s, ‘being Kurdish’ was different—it meant struggle. The armed struggle gave meaning to our identity. Today, many of our boys say they are ready to die on the front, but these are just words.”24

On the other hand, those who were born after 1991 are increasingly alienated from a narrative of Kurdayeti that delegitimizes them. They often express a distorted sense of the past, which amplifies the challenges of their present. “During Saddam, people had ration cards and salaries. At that time there was no corruption,” complained Shakho, a shy fifteen-year-old working in the Sulaymaniyah bazaar.25 Hassan, a sixteen-year-old vendor in Erbil’s bazaar, echoed Shakho’s words: “During Saddam, there was no corruption, and things were better—even for Kurds. Back then, some Kurds became peshmerga for reasons of Kurdayeti, but they all died of hunger in the mountains. The others became peshmerga because they were criminals hiding from the government, and they are the ones who became masouls [leaders] and thieves.”26 For many youth, even the factual parts of the Kurdish nationalist narrative—namely, the former generation’s resistance against a repressive regime in Baghdad—are being tainted by their association with the establishment.

Faced with this legacy, the younger generation is made to feel indebted to precisely the generation by which they feel trapped. The instrumentalization of the past forces society, and the younger generation in particular, to operate within the old order’s logic and mechanisms. It suffocates the marketplace for new political ideas, shrinking opportunities for reformist leaders to emerge and provoke a political transition to a new order.

Kurdayeti in a Stalled Transition

Instead of becoming a major regional player with realistic ambitions of becoming a model of democracy surrounded by dysfunctional neighbors, Iraqi Kurdistan has become mired in stasis. This section analyses how the inextricable relationship between party leaders and Iraqi Kurdistan’s institutions, combined with regional crises, have fossilized the established order and prevented a political transition from taking place.

In 2011, the uprisings in the Middle East and North Africa inspired hundreds of mostly young Kurds to take to the streets demanding a reformist agenda. They protested against the corruption of the KDP and the PUK, the two parties’ domination of the political system, and social injustice. These protests represented a fleeting opportunity for reformists to ally with society to trigger a transition, but instead, the political parties leveraged their control over the region’s security forces to coordinate a crackdown that extinguished the protests. After 2014, Iraqi Kurdistan experienced democratic backsliding. Parliament did not convene for three years (2015–18); the post of the KRG president was extended beyond agreed term limits; and human rights violations rose in number, including killings of critical journalists.27 During this time, Goran’s opposition to the KDP and PUK proved self-defeating. It only encouraged the established parties to cooperate in their efforts to survive by repressing dissent and political opposition.

After the opportunity of 2011 was lost, conflicts and shocks engulfed the region and reinforced the established leaders over reformists. Three shocks in 2014 were particularly key to preventing society from re-mobilizing against the leadership. First, Baghdad cut the budget of the KRG, as a result of a dispute over the KRG’s independent oil exports.28 This offered the leadership an external agent of blame for the region’s economic woes. Second, the price of oil crashed globally. This left the parties unable to pay public sector salaries on time or in full.29 Different families, classes, and towns competed for a share of an ever-smaller pie. And third, the Islamic State rose on Iraqi Kurdistan’s doorstep. The rise of the Islamic State empowered the established leaders, who had a stronger grip on security forces. Reformists, for their part, failed to leverage rising public disaffection, leaving protests localized, disparate, and unable to challenge the establishment.

In the face of mounting public discontent, several Iraqi Kurdish leaders, and in particular Masoud Barzani (then the KRG president), doubled down in 2017 by organizing the independence referendum. The vote diluted the debate over Kurdayeti to the single issue of independence, presenting it as the linear conclusion of the traditionalists’ past armed struggle. A “yes” vote in the referendum necessarily implied agreement with the leadership that put it forth. But voting no meant betraying the lowest common denominator of Kurdayeti. Reformists were left cornered, forced either to subscribe to the traditionalists’ project or risk being seen as traitors.

According to KRG figures, the referendum passed, with high turnout and 90 percent voting in favor of independence.30 But this did not deliver sovereignty. Instead, it provoked a severe backlash from Baghdad and the Kurds’ international partners that undid many of the gains Iraqi Kurdistan had made since 1991. Most significantly, in the aftermath of the referendum, Iraq reasserted control over most disputed territories, including Kirkuk and its oil-rich surroundings. Kurdish leaders, despite this setback, found opportunity in the crisis. The referendum, and Iraq’s defeat of its ambitions, created a climate of fear that resigned many Kurds to accept the status quo, rather than risking instability by challenging it. This resignation became evident in the 2018 regional parliamentary elections, in which the KDP and PUK emerged triumphant, coming in first and second place respectively, despite the preceding four years of crisis.31 These results can be explained by low turnout—which benefited the traditional parties’ committed bases—and, very likely, by electoral fraud.32

Regional Context

The stalled transition in Iraqi Kurdistan is taking place in the context of a broader trend in the Middle East of the reassertion of establishment regimes in the aftermath of aborted attempts to transition to new orders. The Arab uprisings that began in 2010 prompted Iraqi Kurds, especially among the young generation, to take to the streets. The wave of conflicts that ensued after the Arab uprisings, however, helped reinforce the established Kurdish leadership, because of the stability it purported to offer.

The demands of the Iraqi Kurdish protesters of 2011 included a change in political leadership, the overthrow of the two-party system, an end to corruption and nepotism, and socioeconomic improvements.33 Although many protests have taken place since, none have had as strong a chance of challenging the leadership. Not only was the 2011 wave propelled by the regional wave of the Arab uprisings, but protestors proved able to scale up across localities to deliver a relatively concerted message of dissatisfaction with the status quo.

Visible street protests were mostly confined to Sulaymaniyah governorate—expressions of dissent among those living in KDP strongholds in Erbil and Dohuk governorates, where security controls are notoriously tighter, were less conspicuous. Nevertheless, protestors maintained some contact beyond their own localities, in recognition of the fact that they shared similar grievances. For example, Dler, a thirty-two-year-old Goran member from Ranya and a leader of the 2011 protest movement, explained that university student groups across Iraqi Kurdistan maintained close contact, a fact that threatened the leadership. “We, in Ranya University, had a lot of contact with Koya University,” he said, referring to a university located in a PUK stronghold in Erbil governorate. “The leaders were afraid of the universities. They sent home fifty thousand students from Salahaddin University” in Erbil.34

Yet, the 2011 protests fragmented and tapered off after just two months, after a coordinated crackdown by KDP and PUK security forces. Regional deterioration after the Arab uprisings helped inhibit a revival of the protest movement. Kurds in Iraq—especially youth—watched closely as peaceful protests in neighboring Syria and elsewhere in the Arab world descended into conflicts. They got the message loud and clear: challenging the establishment can lead to instability. Against the backdrop of bloody regional conflict, the protestors’ grievances appeared petty. By contrast, the leadership’s argument that it could preserve Iraqi Kurdistan’s stability appeared strong. Official party media depicted the Kurdish protests as synonymous with disorder, liable to disrupt Iraqi Kurdistan’s autonomy and stability. “We tried to achieve something like the Arab Spring in Kurdistan in 2011, but we didn’t succeed,” said Hanar, an educated Kurdish woman in her twenties in Erbil.

Generational divides also emerged over the protests. Seen from the perspectives of those who took to the street, the protests were a much-needed push toward a new type of leadership. Elders and the established elite, however, were more likely to see the protests as a threat to Iraqi Kurdistan’s hard-fought gains. The case of Akko, a twenty-four-year-old graduate student and the son of a PUK peshmerga martyr, illustrates these divides: his mother scolded him for going to the streets in 2011, saying his participation in protests was “disrespectful to what his father had fought for.”35

Regional turmoil also made Kurdistan stand out as a rare zone of stability, and offered Kurdish leaders a platform to emerge as new regional, and even international, players. Barzani stepped up political and military support for allied Kurdish factions in Syria, aiming to extend his influence across the border. In 2013, he also made a historic visit to Diyarbakir, the unofficial capital of the majority-Kurdish southeastern part of Turkey.36 These actions bolstered his nationalist and transnationalist credentials at home, just after the blow of the 2011 protests.

In August 2014, the Islamic State took over Mosul and nearby territories only a few kilometers away from Iraqi Kurdistan’s internal boundary with Iraq. This new threat reinforced the prioritization of security and stability in the public debate, and offered Kurdish leaders yet another chance to shine on a global stage. An advance by the Islamic State on Erbil appeared possible. Although most of the public continued to view Kurdish leaders as corrupt, the leaders shored up some of their legitimacy by stepping back into their historic roles as protectors of Kurdistan from external threats. This tactic proved effective, at least temporarily—though many Kurds remain cynical about it. Amir, an eighteen-year-old who dropped out of school in 2014 to sell counterfeit sneakers in the Sulaymaniyah bazaar, identified the fight against the Islamic State as the key inhibitor of unrest. “They are using Daesh [the Islamic State] to scare us,” he said. “There will be no revolution in Kurdistan as long as Daesh is on our borders.”37

With the rise of the Islamic State, Iraqi Kurdistan’s leaders also emerged as key partners for international military efforts against the extremist group. Western powers offered the Kurds military and political support, which benefited party figures over joint institutions. Iraqi Kurdistan’s leaders were received in Western capitals, bolstering their images as international players. As Akko, who participated in the 2011 protests, put it: “If all European foreign ministers who come to Kurdistan visit Barzani, how can we dare challenge him as our leader?”38

Regional conflicts and trends facilitated the parties’ divide-and-rule approach, which brought back simmering territorial, generational, and political divisions across Kurdish society. Ultimately, they resuscitated the old order in Kurdistan, after it had been tested by the 2011 protests.

Localized Identities, Disjointed Action

Over decades of infighting and divided, party-based governance, Iraqi Kurds have increasingly pinned their identities to their localities. Localized identities have atomized society, precluding the possibility of concerted mobilization. Anti-establishment sentiment is dispersed into pockets of dissatisfaction that the political parties can extinguish in a piecemeal fashion.

During and after the civil war of the mid-1990s, the parties carved up Iraqi Kurdistan into their respective strongholds, isolating Kurdish localities from one another. This legacy has drawn social, political, and even psychological boundaries within Kurdistan. Despite the evolution of a unified central administration in Erbil, party patronage networks have endured and shape society along pre-civil-war lines. Local party representatives—rather than representatives of unified Kurdish governance institutions—remain the intermediaries through which Kurdish society can access services, employment, educational opportunities, security, and other forms of governance. The parties have also deliberately stoked societal fragmentation in order to manipulate the population’s anti-establishment feelings into forms of pressure on rival local party leaders. In Darbandikhan, a mid-sized town in Sulaymaniyah governorate, for instance, Goran encouraged protests in 2015 in order to undermine the PUK-led local administration. In the region of Garmian, just an hour’s drive south, the PUK capitalized on local protests against the Goran-led local administration in Kalar.

Beyond party structures and manipulation, the persistence of strong kin-based (familial and tribal) identities in Kurdistan further fragments society. Moreover, the proliferation of universities in small- and medium-sized towns in recent years has reinforced the expectations of parents that their children will remain at home, narrowing opportunities for youth to interact with their counterparts from other parts of Iraqi Kurdistan.

Our interviews with Kurds in both rural and urban areas and across various party strongholds revealed strikingly similar grievances and demands—jobs, services, voice, opportunities delinked from the parties, and an end corruption. Yet our interviewees were generally unaware that their grievances were shared by their counterparts in other parts of Iraqi Kurdistan. Many interviewees expressed the belief that their counterparts were better off than them. For example, Arian, a twenty-one year-old in Darbandikhan, explained that in 2011, the protests in that town had little connection with those in neighboring areas such as Garmian, because each locality “had its own specific demands.” When asked to elaborate on the differences between the demands of Darbandikhan residents and others, he pinned it on politics. “We are Goran, they [in Kalar] are PUK, and in Erbil they are KDP.”39

Perceptions of inequality are particularly pronounced among Kurds in smaller towns who feel alienated from Kurdistan’s urban centers. Arian insisted that Kurds in Sulaymaniyah, just an hour’s drive away, enjoy “giani khosh” (the good life). Baran, a twenty-six-year-old woman in Darbandikhan, lamented the monotonous daily routine followed by people in Darbandikhan, saying people only “go to work and come home, that’s it.” She compared this with Sulaymaniyah, where she believed residents have more diverse activities to choose from.40

The result of these localized identities is that, even if Kurds across Iraqi Kurdistan share similar grievances, their actions tend to be limited to the boundaries of their town, village, or city. In scattered protests since 2011, protestors have struggled to scale up past local grievances that pit neighboring localities against one another. By reproducing the boundaries drawn by the political parties, those opposed to the establishment hamstring their own potential for effecting political change.

Indeed, many Kurds point to their own fragmentation as the main factor obstructing a “shoresh” (revolution) against the parties. “The shoresh would need to be everywhere, but people in Erbil and Dohuk are afraid,” said Kamran, a twenty-six-year-old bookseller in Sulaymaniyah. “There, if people go to protest you will not see them the next day.”41 (Security crackdowns on protests are notoriously severe in KDP-controlled areas.) Khosrat, a twenty-one year-old from a small village in Sulaymaniyah governorate, echoed this, saying that because people in Erbil would not protest for fear of KDP retaliation, he did not expect a Kurdistan-wide uprising. A localized protest movement, he said, would have no chance of success.42

Reformist forces in Iraqi Kurdistan have also failed to overcome ethnic boundaries in Iraq. In the past, links between Kurdish and Arab communists helped catalyze transitions toward a new order in Iraqi Kurdistan.43 Today, however, the post-2003 regional autonomy arrangement has left Iraqi Kurds more disconnected from other Iraqis than before. As a result, the agendas of a reformist party such as Goran, or of civil society organizations, are disconnected from other reformist forces operating elsewhere in Iraq. This saps Iraqi Kurdistan’s reformists, younger generation, and civil society of another potential impetus for the articulation of a new leadership and vision.

The post-2003 regional autonomy arrangement has left Iraqi Kurds more disconnected from other Iraqis than before.

The Rentier Economy

Another factor that contributes to obstructing political change is the endurance of Iraqi Kurdistan’s rentier economy, which is primarily dependent on natural resource wealth. Throughout economic highs and lows, the rentier economy has reinforced the dependency of Kurdish society on the ruling class, discouraging sustained mobilization by the former against the latter.

After the U.S. invasion of Iraq in 2003, Iraqi Kurdistan’s wealth in natural resources encouraged the region’s leaders to carve the population up into clientelist networks. Even as the region took on the shape of a democracy, the KRG’s economic strategy focused almost entirely on developing its oil and gas resources. Oil rents have allowed the parties to swell the public sector, employing up to 70 percent of the workforce.44 The parties have not made progress in reviving Kurdistan’s agricultural sector, once the region’s key industry. The agricultural sector had been debilitated by decades of conflict, forced displacement and urbanization, scorched-earth policies by the former regime, and humanitarian aid in the form of cheap, imported food.45

Today, imports, mostly from Iran and Turkey, account for around 80 percent of Iraqi Kurdistan’s fruit and vegetable consumption in the winter.46 With an undiversified economy and weak institutions, established leaders have easily gained decision-making power over how to allocate energy rents and the share of the overall Iraqi budget sent to the KRG by Baghdad. Party leaders thus shape decisions about public expenditure, including who gains access to public sector employment.

As a result, Kurdish society can only access the benefits of oil rents through reliance on clientelist networks linked to these leaders. Dependence on patronage paralyzes society, dissuading it from taking real initiative against the leadership, despite widespread discontent. It neutralizes the middle class, which is largely employed in the public sector and thus has the most to lose from being cut off from party connections. The fate of poorer and less educated classes, in turn, is tied to the buoyancy of the middle class. Once reliant on agriculture, the poor are now largely employed in the lowest ranks of the public sector or in the informal economy as “krekar” (day laborers).

Beyond class relations, patronage has also left young Kurds more reliant on their parents, who usually enjoy longer-standing ties to the political parties. Similarly, it reinforces patriarchal relations, leaving women more reliant on their male relatives, who tend to have more direct party ties.

There is thus a paradoxical relationship with the political elite. Many Kurds denounce the ruling class for their monopoly over resources, while simultaneously demanding from them greater disbursements. They view the establishment as immutable and incapable of reliably delivering services and salaries. But they also continue to view the establishment as the only means through which they can extract such benefits.

The economic recession of 2014 could have been an opportunity to mobilize the middle class and the young generation toward breaking their dependency on party networks. Although reliable monthly figures on GDP, employment, and industrial production are unavailable, a 2015 report by Mark DeWeaver at the American University of Iraq, Sulaimani argued that the recession was “great… by any definition of the term.”47 According to regional government statistics, the poverty rate is assumed to have jumped from 3 percent in 2013 to 12 percent in 2015.48 The KRG responded to the crisis by running up debts with various creditors, which led to a dangerous debt crisis. A 2018 report by the U.S. Institute for Peace warns that the KRG likely holds debt in excess of 100 percent of its GDP.49

The onset of the recession in 2014 left the KRG unable to pay its outsized public sector salary payroll in full or on time. This situation has persisted for years, causing public discontent that frequently leads to small-scale and localized protests.50 By early 2016, some government employees had seen their salaries drop by 40 percent, and faced frequent delays in payment. The recession left banks without cash to fund withdrawals of depositors, and as money owed to construction and oil companies piled up, the private sector was dragged down along with the public one.51

Rather than undermining the political parties, the recession has reinforced Kurdish society’s reliance on party networks, and the consequent power dynamics, described above, between classes, generations, and genders. The recession has not only hurt the public sector, but also shrunk the private and informal sectors, leaving people of all classes with even fewer alternatives to the party networks.52 The recession has fragmented society further, as competition grows for what spoils remain.

The sudden shortage of resources in a rentier economy has also transformed the protest landscape. Unlike in 2011, protests since 2014 have been low-intensity, highly localized, and focused on immediate needs. (Although, as in 2011, they remain mostly confined to PUK- and Goran-controlled areas in the east, as would-be protestors in KDP-controlled areas fear harsh crackdowns.) Party leaders have proven adept at dousing such protests with a mix of repression and piecemeal, quick-fix concessions on salaries and other services. This strategy has not eliminated protests or addressed the grievances that drive them, but has prevented them from developing into a cohesive movement that could challenge the establishment’s rule.

The problem is that now, with the economic crisis, every time teachers go to demonstrate, they go for a day. Then, as soon as they get their salary, they go home. They’re not staying out all day and night asking for their rights. Demonstrations die because after a few days people get their salaries, and go home.53

Renwar, a twenty-five-year-old journalist in Sulaymaniyah, expanded on this point.

In 2011, we demanded human rights and political reform, including within the oil sector. Now the protests are all about salaries. In the past three years, I cannot even remember any demonstration about electricity. The demonstrations have been totally reduced to the demand of salaries. Young people are too passive, and the KRG has no fear of them.54

Starting in late 2017 and early 2018, the declaration of victory over the Islamic State, the rise in oil prices, and Baghdad’s gradual repayment of the region’s budget share have eased the economic crisis and offered a sense of renewed economic and political stability. Although in theory this recovery should ease the dependency of youth and the middle class on party networks, it may in fact feed the impression that an economy based on payouts from oil rents can last forever, and that the past four years of recession were only an interlude. Youth and the middle class may emerge from this recent crisis more dependent than ever on patronage networks.

Institutional Blockage

A transition to a new order will only be possible if reformists and their supporters find avenues for political participation. Yet Iraqi Kurdistan’s institutions are blocked off to new forces.

Political parties are one such example. Kurdish parties were once the organizations through which figures rose through the ranks to emerge as new nationalist leaders. Today, however, they are cliques of aging founding figures invested in preserving the status quo. The appointment of new or younger members to party leadership positions has not challenged their power structures. In the May 2018 Iraqi elections and the October 2018 KRG elections, for instance, the KDP put forward new and young faces on its candidate lists. But these younger figures were either carbon copies of their elders, or otherwise unable to act autonomously from their more senior party backers. The profile of a young KDP cadre offers an example. As the son of a mid-ranking KDP member, he has been afforded special privileges in the party. He wholeheartedly supports the political agenda of Masoud Barzani and sees his involvement in the KDP as a way to pursue his personal ambitions, which include running for parliament and, later, becoming a senior government official.55 It is precisely his commitment to the old order—or, at least, his dependence on it—that allows him to participate in politics through the party structures.

The peshmerga, once the primary avenue for young Kurds to engage in the national struggle, has today become a tool for preserving the status quo. Many of today’s political leaders earned their nationalist stripes when they were peshmerga commanders. Indeed, for half a decade preceding the fall of Saddam Hussein in 2003, the peshmerga were the primary framework through which younger Kurds could engage in the nationalist struggle and emerge as new leaders. Today, however, the peshmerga has lost this historical role. Although the peshmerga began, after 1991, to transition from a party-based guerrilla force to a professionalized army, the institution remains hostage to party leaders. Party leaders have appointed loyalists to key peshmerga positions, and have placed themselves at the heads of disjointed chains of commands. The result has been the disempowerment of the units that report to the Ministry of Peshmerga Affairs, rather than to specific party leaders. The move toward further professionalization, and toward enabling younger officers who were trained by the United States after 2003 to take on leadership roles, has been thwarted.

The war against the Islamic State, which ushered into Iraqi Kurdistan significant international military support, at first appeared to present an opportunity to revive the peshmerga as a vehicle for national engagement. Instead, however, the war prompted an intergenerational rivalry within the peshmerga. Leaders further personalized the chains of command by partitioning the peshmerga into even smaller units, which responded to party figures. This weakened younger officers who were more inclined to disentangle the peshmerga from the parties. The case of an officer trained after 2003 in Qala Chawlan, north of Sulaymaniyah, illustrates this point. At the start of the war against the Islamic State, he had been promoted to the rank of brigadier general and posted to one of the most sensitive military flashpoints, the disputed area of Tuz Khurmatu in Salahaddin governorate. In 2015, however, he and others with similar profiles were suddenly replaced by an established PUK party figure. The younger officer was relegated to a bureaucratic role in the Ministry of Peshmerga Affairs in Erbil, far away from the frontline.56

After the 2014 economic crisis, the peshmerga also helped entrench the leadership by soaking up young, poor men whose livelihoods had been shuttered. Recruiting these men into the peshmerga brought them more directly into the fold of party structures, leaving them less free to protest or cause other forms of trouble for the leaders. Many such men were given the riskiest assignments in the war against the Islamic State. If wounded, they and their families ended up even more reliant on party networks in order to be able to access medical care.

The war against the Islamic State has thus restored power to the generation of peshmerga commanders who had fought in the past and who are linked to party structures. As in the politburos, the only younger peshmerga who have been elevated to the forefront of the fight against the Islamic State are those who are either committed to the old order, or have strong family links to it.

In a democratic Iraqi Kurdistan, parliament should serve as the primary mechanism for new leaders to enter politics. Instead, the parliament has failed to provide democratic oversight vis-a-vis party leaders. Nor has it become an avenue for new leaders to emerge and break with the past.

When new forces have broken into Iraqi Kurdistan’s institutions, established leaders have responded by paralyzing those institutions. In Iraqi Kurdistan’s 2009 legislative elections, for example, Goran outperformed the PUK in Sulaymaniyah, and later gained control over certain ministries, including the Ministry of Peshmerga Affairs. But this electoral victory did not translate into a mechanism to renew the political system. Rather, the outcome was years of institutional paralysis, with disputes over Barzani’s term-limits resulting in the shutdown of parliament for two years, from late 2015 to late 2017. A striking example of how leaders blocked the functioning of democratic institutions took place in 2015, when the KDP barred the speaker of the parliament, a Goran member, from physically entering Erbil, where parliament is located.57 This episode recalled the demarcation of Iraqi Kurdistan into two separate administrations during the 1990s.

Elections should serve to inject new blood into the political arena, but they have also become a tool of self-preservation for the established leadership. In the May 2018 Iraqi parliamentary elections, the KDP and PUK faced the challenge of rising discontent over corruption and poor governance. The KDP was under particular pressure, as the elections came off the heels of the backlash against the Barzani-led independence referendum. In order to maintain its constituency, the KDP fell back on tribal structures in its strongholds. For instance, in Dohuk, instead of putting forward politburo members as candidates, the KDP pragmatically decided to place at the top of the list a prominent tribal leader from the Muzuri tribe. This helped ensure that members of this tribe—the largest in Dohuk—would vote for the KDP despite rising discontent. It was ultimately a winning strategy, as the KDP won ten seats in the Dohuk governorate—an improvement compared to the eight it won in the previous parliamentary elections.

During these elections, the leadership also resorted to outright sabotage of the political process, even at the expense of breaking the trust of Kurdish voters. Despite its poor performance in terms of governance, and tangibly high levels of public anger against its leaders over recent years, the the PUK earned eighteen seats (losing only four compared to the 2014 elections). In Kirkuk it even won in non-Kurdish areas, where it had never obtained votes.58 The performance of both political parties can hardly be explained without widespread electoral fraud. As a credible recount of the vote is not probable, this fraud is likely to only increase Kurdish voters’ distrust in the political process and discourage them from participating at all in future elections.

Eclipse of Kurdayeti

The more the leadership appropriates Kurdayeti for its own self-preservation, the more Kurdish society is alienated from Kurdayeti. Youth in particular associate Kurdayeti with the political establishment. “Nishtimani Kurdistan has no meaning for me,” said Arian, the twenty-one-year-old in Darbandikhan, referring to the concept of a Kurdish homeland. “This country is not for ordinary people, but instead for the leaders and their sons.”59 Hassan, the sixteen-year-old vendor in Erbil, echoed this. “If you do one minute of Kurdayeti,” he said, “That minute of your life is wasted.”60 A young person in a mid-sized town in Duhok governorate declared that “Kurdayeti equals hizbayati [party activities].” His large group of friends eagerly jumped in to second that statement.61 When asked what Kurdish identity meant to him, Shakho, the fifteen-year-old working in the Sulaymaniyah bazaar, responded abruptly. “Nishtimani Kurdistan has no meaning for me,” he said. “I don’t think the Kurdish flag and the peshmerga are symbols of anything. I think everyone is thinking about their own pocket, and not about a cause.”62

Kurdayeti itself has become a point of contention. Many Kurds remain attached to the symbols of Kurdish nationalism, even as they are disappointed in what those symbols have become. For example, Hanar, the educated woman in her twenties in Erbil, described her attachment to an archival image of the peshmerga.

I am proud of the peshmerga, but even when I use the peshmerga hashtag on Twitter, I think to myself, which unit? The politicians are trying to remove the beautiful image of the peshmerga we have of 1991. After 1994, the peshmerga became very politicized, and after 2015 people understood this is not the pure peshmerga of 1991 anymore.63

Others are still more critical: Amir, the sneakers seller, said the peshmerga used to fight with “dilsoz” (faith, heart), but now they do not. “The peshmerga has become a system of thieves,” Amir said when asked why he did not join the peshmerga, as many in his father’s generation had done.64 Many other Kurds echoed Amir, emphasizing the bonds between the peshmerga and the corrupt political establishment. “Why should we go fight for this political class?” said Kamran, the bookseller, when asked why he did not join the peshmerga.65

The pervasiveness of the leaders’ patronage networks means that few can operate independently of them, much less confront them. Most Iraqi Kurds, despite deep dissatisfaction with the status quo, accept and work within its parameters. A significant number, and especially youth, opt to escape from what they perceive as an unchangeable reality by migrating abroad. Only a small minority tries to emerge as this era’s new reformists and overtly engage in political opposition.

A State of Contradiction

The large majority of Kurdish society depend on, and therefore must compromise with, the pervasive party-based status quo that they oppose. This offers a semblance of stability, but risks leading Iraqi Kurdistan toward greater crises.

The family of Baran, the twenty-six-year-old woman from Darbankdikhan, illustrates the paradox. The family has traditionally supported the PUK. She complained that her brother, a peshmerga who lost his leg on the frontlines fighting the Islamic State, had not received adequate medical care and compensation from the party that had recruited him. However, she said, her family would continue to vote for the PUK or KDP, rather than protesting in the streets over her brother’s case, which she said could not achieve anything.66 As another young man from the area put it, “I would not participate in a local uprising, because if I did, I would lose everything.”67

Khosrat, the twenty-one-year-old from a small village in Sulaymaniyah governorate, exemplified these contradictions. We found him amid a clique of young boys with elaborately gelled hair and skinny jeans loitering in front of the village shop. Smoking and toying with his mobile phone, he told us he works for the local anti-crime unit of Asayish (the police and intelligence unit) “in civilian clothing”—a euphemism for an informant. Khosrat thus relied on the political establishment, which Asayish serves, for his livelihood. However, he proudly told us he joined the 2011 anti-government protests in his area. Asked if he saw a contradiction between his work as an informant for Asayish and his participation in anti-government protests, he retorted that the protests were for “Kurdayeti.”68

Khosrat and many other Iraqi Kurds reflexively mimic the protective logic proposed by the leaders, even if they believe the complete opposite. Several Kurds we interviewed blamed the leadership for the lack of salaries, only to echo, a few sentences later, those same leaders’ argument that Baghdad is in fact to blame for not sending the KRG its share of the budget.

Many Kurds see the party leaders that dominate their areas as part of the problem, but also internalize the party’s factionalism, frequently shift blame to party rivals. For example, Arian, the twenty-one-year-old who had protested in the PUK stronghold of Darbandikhan, said he was protesting “against the government in Hewler [Erbil].”69 He identified Erbil as the agent of blame, despite the fact that his grievances—jobs, salaries, services—were local issues.

The state of contradiction clearly emerges with the independence project. The project continues to carry significant emotional weight, but it has been co-opted by the leadership. Months before the September 2017 independence referendum, all Kurds we interviewed across PUK- and Goran-held areas insisted they would not vote, with some referring to the initiative as a “Barzani referendum.”70 That is, they saw the referendum as an instrument of the political establishment that they reject. We also heard many young Kurds say they no longer wanted an independent Kurdistan. “If we had an independent Kurdistan, the leadership would be even worse, because it would be squeezed between Turkey and Iran,” said Kamran, the twenty-six-year-old bookseller in Sulaymaniyah bazaar.71

In the same bazaar, Amir, the sneakers seller, put it more bluntly. “I don’t want an independent Kurdistan,” he said. “If there were to be an independent Kurdistan, I would have to work even more, and there wouldn’t be anything [any money] coming from Baghdad.”72

Despite these misgivings, Iraqi Kurds appear to have overwhelmingly voted “yes” on the independence referendum.73 After the referendum, many of our interviewees acknowledged voting for it, even while insisting that Kurdish nationalism had been emptied of meaning for them. When pressed, they were unable to articulate how they reconciled these two views.

Further illustrating the confusion youths feel in trying to separate Kurdayeti from party politics, a large group of youths interviewed in a midsized town in Dohuk governorate, a KDP stronghold, all said they did not vote in the May 2018 elections, though they had earlier voted “yes” in the referendum. It would appear that even as youth reject overt party politics, they still find it difficult to resist the parties’ nationalist cries.

Escape

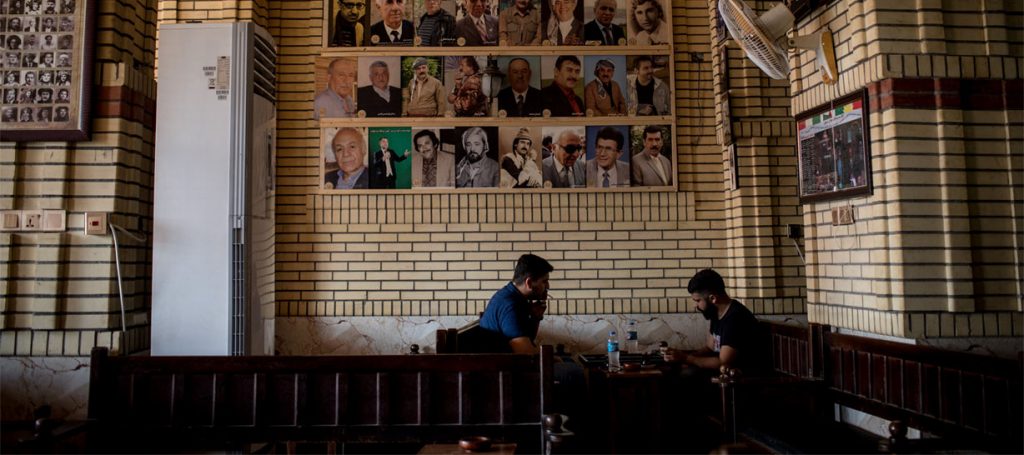

Faced with the reality of compromising with an order they oppose, many Iraqi Kurds, especially among the youth, feel powerless. Depending on their socioeconomic situation, disaffected young Kurds may pass time loitering in cafes or shopping malls, or, in rural areas, at local bazaars or tea houses. In all of these spaces, interviewees expressed general disinterest and purposelessness, and often described themselves to us as “betaqat” (lacking energy or initiative, depressed—the term also indicates boredom). “Young people have no more dilsoz [faith/happiness],” said Khosrat, the twenty-one-year-old in rural Sulaymaniyah governorate. “If they don’t have a card to recharge units of their phone, they get betaqat.”74

Escape through migration can seem like the only viable way to break with this grim reality. Arian, the young man in Darbandikhan, described his lack of alternatives. “The only choice we have in Darbandikhan is to either go to the peshmerga or work in the construction business as krekar,” he said, using the term for precariously employed day laborers. “There are some people working in the public sector (like teachers and doctors), but they risk not receiving their salaries. I want to migrate to Europe and get to Germany.”75

Leaving Kurdistan does not necessarily provide better economic opportunities. When young Iraqi Kurds do make it to Europe, they usually accept employment in jobs below their skill levels. Most people in Iraqi Kurdistan are well aware of these realities, since they receive reports from their friends and relatives who are among the tens of thousands of young Kurds who have gone to Europe.76 It seems that leaving is still an attractive option because it allows them to break with an unchangeable reality and the hierarchies that have been imposed by the establishment.

In Search of a New Way Forward

Despite the many obstacles to change in Kurdistan, including the decline since 2014 of street protests as an effective means for triggering political transformation, a small minority continues to engage politically. Their activities provide hints about how Kurdish society could navigate a way out of the current impasse. Some of those still engaged, particularly in Sulaymaniyah governorate, participate in formal political channels, such as joining an opposition party. An even smaller minority manages to find new avenues for participation outside the framework of party politics, namely independent civil society. Each of these avenues has its limitations.

“If you don’t participate in politics through the parties, then older people will take all the places. You’re either a wolf, or you get eaten by a wolf.”

Those who engage in political parties see “operating from within” as the only viable avenue for effecting change. Dler, the Goran member from Ranya, explained why he joined the party. “Parties are the strongest channel for political participation,” he said. “If you want a real role, you have to join a party—whether a traditional party, or a new one. If you don’t participate in politics through the parties, then older people will take all the places. You’re either a wolf, or you get eaten by a wolf.”77

However, those who join the parties must compromise with their internal hierarchies and mechanisms of self-preservation, which tend to reproduce old practices. This is particularly true of the older, establishment parties. “I have served in the PUK’s international relations bureau for three years,” said Zana, a young PUK party cadre. “I am stuck in my office with no prospect but to continue to serve the same party leaders. They haven’t taken on board many of the proposals I made to make the bureau better.” Zana was considering leaving the party and working for an international nongovernmental organization (NGO).78

A small group of frustrated Iraqi Kurds have engaged with Kurdish national identity and politics by aligning with a different kind of anti-establishment party: the PKK, a Turkish Kurdish guerrilla movement that maintains its bases in the Qandil mountains of Iraqi Kurdistan. Khosrat, the twenty-one-year-old in a village near Darbandikhan, expressed support for the PKK, saying the group fights for nationalism and “protects all parts of Kurdistan.” If it were not for the PKK, he said, “Turkey would be in Sulaymaniyah by now.”79 He said five of his friends have already joined the PKK in Qandil. He hopes that the PKK will gain more power in Iraqi Kurdistan than the KDP or the PUK. Such sentiments are relatively common among Iraqi Kurdistan’s youth, who see the PKK as an alternative to the mismanagement and corruption of the ruling parties. The PKK is unlikely to emerge as a major force in Iraqi Kurdistan, where the traditional parties, the KDP and PUK, maintain their grip on society. But it may increasingly offer a way for a minority of frustrated Iraqi Kurds—especially among youth—to engage with an alternative model of Kurdayeti.

As traditional party politics becomes a cynical and contradictory space, many are seeking avenues of engagement that are independent of the parties. This has given rise to a fragile but visible civil society in Kurdistan. “I see civil society as a better route for political participation than the parties, because all the parties require discipline according to the party line,” said Halsho, a thirty-two-year-old working for a local NGO in Erbil. “In civil society, you can be more open and flexible.”80

However, even much of civil society has been claimed by the political parties. Several major NGOs and charities are linked to the establishment parties (for example, the Barzani Charity Foundation). Beyond that, Goran’s transition from an anti-establishment movement—with a loose internal hierarchy and an agenda to challenge stiff party-dominated structures—to a formal and formidable opposition party has complicated the space for independent opposition voices. “Before the creation of Goran, civil society was more effective than now,” said one Kurd involved in civil society. “This is because, nowadays, the KDP and PUK see civil society as part of Goran, as Goran-affiliated, especially inside of Sulaymaniyah.”81 Goran has occupied the sphere of the opposition, similarly to how the KDP and PUK have dominated traditional politics.

The death of independent media in Kurdistan has accelerated the shrinking of platforms for political participation outside of party frameworks. Kurdish authorities have adopted intimidation tactics in an attempt to silence independent journalists. Reporters who have criticized the KRG have been detained, attacked and even killed, with party-linked figures suspected to have been involved.82 The economic crisis, meanwhile, left independent media outlets with few sources of funding delinked from the parties. Hawlati and Awena, two independent newspapers, both wound down amidst financial difficulties during the economic crisis.83 The owner of NRT, once considered a relatively independent television news station, formed his own party in 2017 and ran for parliament, turning this TV station, too, into a party-affiliated network.84 The result is that there is currently no major media outlet in Iraqi Kurdistan that is independent of the parties, leaving few professional channels for civil society engagement independent of the parties. In this shrinking space, social media has become a key platform for political engagement. However, the party-affiliated media outlets have begun moving in there too, investing more resources in their social media presences.85

There is currently no major media outlet in Iraqi Kurdistan that is independent of the political parties.

The consequence is that there are very few viable channels for independent Kurds to engage in politics today. Those who have survived as a part of independent civil society are in the minority, and are only able to effect change on the margins. They are committed to a very long-term vision of change, in which small-scale advocacy on ad hoc initiatives will eventually add up. Peshkawt, a thirty-four-year-old active in civil society in Erbil, described an example of such a small victory: civil society lobbied the KRG Ministry of Youth and Culture to take Mullah Mazhar Khorasani, a Kurdish cleric who said offensive things about women on his television talk show, off the air. They succeeded—but only fleetingly. Khorasani was allowed back on the air three days later.86 Peshkawt believes the parties use small victories to control civil society. “When civil society gets agitated, they give it a bit of space so that they calm down,” he said.87

Achieving change on a bigger scale—for example, challenging the results of the May 2018 elections on the basis of widespread fraud—is out of reach. “We had many NGOs monitoring the elections, and we are sure there was corruption and cheating, but we have no proof,” Peshkawt said. “We are doing advocacy and trying to struggle against this fraud through legal and institutional ways.”88

Regional Need for Renewal

The stalled transition has brought Kurdish nationalism to an impasse. Kurdayeti is suspended between an ethnic-based narrative that provides benefits on the basis of party affiliation, and a new narrative that is struggling to emerge—one that emphasizes civic belonging, citizenship, and democratic institutions.

Protests in 2011 failed to trigger a transition, and the subsequent crisis of 2014 has reinforced the old order. The climate of crisis and insecurity has made it easier for Kurdish leaders to remain in power despite growing societal discontent.89 The parties are turning further inward, increasingly appointing family members to key positions and obstructing pathways for new leaders to emerge.90

Iraqi Kurdistan’s situation echoes a larger trend in the Middle East, where the push for change, once aborted, has reinforced the established order, stiffening its structures and shrinking the space for opposition. Egypt, Syria, Turkey, and even Arab parts of Iraq have undergone similar experiences, with similar results, since the uprisings that started in 2010. In these countries, street mobilizations—largely led by younger generations—have voiced discontent, posed a threat to established leadership, and searched for new, citizenship-based pacts between society and leaders. Such pushes for change have triggered violent responses and a climate of instability that buoys the establishment. These Middle Eastern countries live, too, in a stalled transition in which leaders point to regional instability and resort to internal repression, convincing most among the population to opt for disengagement from politics and individual-level survival strategies—migration being one of them.

These patterns have unfolded in Iraqi Kurdistan, too. The peculiarity of the Kurdish case, however, rests in the consequences that this back-and-forth movement—toward and against transition—has for eroding the meaning of Kurdayeti. Kurdish national identity is now caught in the narrative of a magnified past, which has been used in ways that entrench society’s disaffection and disengagement. Many Iraqi Kurds, and youth in particular, no longer relate to Kurdayeti, which they see as belonging to and abused by the leadership.

The Iraqi Kurdish leadership can, for now, continue to preserve itself by disbursing resource rents and regressing democratic norms. But it cannot hope to mobilize society behind it through a strategy of co-optation, repression, and pointing to the boogeyman of an external threat. This leadership—and the younger crop of carbon-copy leaders it is now nurturing—may well survive. But as a sense of collective national interest disappears, leaders will increasingly brace to fight one another for control over the resources needed to ensure their survival through patronage. Although a taboo on brakuji (in-fighting) has long helped paper over political rivalries, it is not unthinkable that intensifying rivalries could lead to a relapse. Such violence could break out not just between parties, but also between tribes and families, segmenting the society along even narrower lines. Sporadic yet persistent outbreaks of intra-Kurdish violence will eventually destroy what remains of the established leaders’ nationalist credentials, and shift the center of gravity of Kurdish nationalism toward other Kurdish-populated areas. Until then, it seems that the old order, dying out, and the new order, nascent and up against many odds, are bound to coexist in Iraqi Kurdistan.

A smooth transition to a new order would allow Iraqi Kurdistan to maintain itself as the center of gravity for the development of Kurdish nationalism. But the events of 2011 proved that a bottom-up, opposition-driven transition would be costly and ineffective. Success would require top-level leaders, starting with the PUK and KDP, to willingly create avenues for new leaders to emerge. A new circle of reformist leaders would then need to lead a top-down reform process by re-empowering Kurdish institutions, especially parliament, releasing them from party control. Economic reform, and the dismantling of party-based patronage networks, would be necessary for these reformists to rally Kurdish society behind their agenda.

Finally, these reformists would need to revitalize Kurdayeti, putting forward a new vision that incorporates civic values that resonate with the needs and expectations of a changing society. This renewed vision must offer a new pact between Iraqi Kurdish society and leaders, one based on citizenship, rather than party loyalty. The narrative must be unleashed from historical legacies and the singular project of statehood, forcing the new political class that emerges to derive its legitimacy from its governance performance instead of its past achievements. Otherwise, Kurdayeti risks being abused to prop up a decaying order, rather than serving as an inclusive basis for belonging in Iraqi Kurdistan.

This report was originally published on February 4, 2019, and is part of Citizenship and Its Discontents: Pluralism, and Inclusion in the Middle East, a TCF project supported by the Henry Luce Foundation.

COVER PHOTO: The sun rises over a cemetery in the village of Barzan, the hometown of Kurdish leader Massoud Barzani, where the remains of hundreds of Kurdish villagers killed by Saddam Hussein’s forces during the Anfal campaign in the late 1980s are buried. Source:Moises Saman/MAGNUM

Notes

- According to a Kurdish academic, Bayar Mustafa, the term was used as early as the 1920s by the Kurdish nationalist organization, Khoybun. Interview with the author by telephone, December 12, 2018.

- This essay refers to a “national identity” as described by the trend of scholarly literature that defines it subjectively on the basis of a personal sense of belonging, rather than objectively on the basis of a common language, territory, history,and cultural traits. The former conceptualization better explains the Kurdish case because it defines a “nation” as an imagined community, which exists as long as individuals ascribe their belonging to it. This “nation” can therefore exist in the absence of a recognized nation-state. Kurds commonly refer to Iraqi Kurdistan as “Bashur,” which indicates the “southern part of Greater Kurdistan,” a subjective “nation” to which they ascribe their belonging. There are other Kurdish regions with their own names, in Syria, Iran, and Turkey, that lack administrative status as federal regions. Kurds refer to “Rojava” (western Kurdistan), “Rojhelat” (eastern Kurdistan), and “Bakur” (northern Kurdistan), respectively. See Ernest Renan, What Is a Nation?, and Other Political Writings (New York: Columbia University Press, 2018); Benedict R. Anderson, Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism (London: Verso, 2016, originally published in 1983); Rogers Brubaker, “In the Name of the Nation: Reflections on Nationalism and Patriotism,” Citizenship Studies 8, no. 2 (2004): 115-27.

- For more on this interplay, see Denise Natali, The Kurds and the State: Evolving National Identity in Iraq, Turkey and Iran (Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press, 2005).

- Wadie Jwaideh, The Kurdish National Movement: Its Origins and Development (Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press, 2014), 75.

- Robert Olson, The Emergence of Kurdish Nationalism and the Sheikh Said Rebellion, 1880–1925 (Austin, TX: University of Texas Press, 2010). See also Sharafnameh, the first written history of Kurdistan (compiled by Sharaf Khan in 1597), and Mem u Zin, a groundbreaking literary manifestation of the awareness of Kurdish national identity (published by Ahmad-e Khani in 1694–5). Amir Hassanpour, “The Kurdish Experience,” Middle East Report 24, no. 189 (1994): 2–7, 23.

- Wadie Jwaideh, The Kurdish National Movement: Its Origins and Development (Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press, 2014), 80.

- Kurdish political societies and cultural organizations began cropping up in Istanbul and elsewhere, spreading national ideas through secret publications. “Takkiyas”— gathering places for Sufi orders —offered a fertile environment for articulating this identity and forms of self-rule. Wadie Jwaideh, The Kurdish National Movement: Its Origins and Development (Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press, 2014), 102–14.

- The post-World War I order left the Kurds split between four new states’ borders, traced by France and Britain.

- Wadie Jwaideh, The Kurdish National Movement: Its Origins and Development (Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press, 2014), 241.

- David McDowall, A Modern History of the Kurds (London: Tauris, 2014), 296.

- Gareth R.V. Stansfield, Iraqi Kurdistan: Political Development and Emergent Democracy (London: Routledge, 2010), 66.

- The leftists critiqued both Barzani and the Ahmad–Talabani faction of the KDP, though they identified with and collaborated more with the latter. Gareth R.V. Stansfield, Iraqi Kurdistan: Political Development and Emergent Democracy (London: Routledge, 2010), 82.

- The PUK arose from an alliance between Komala, a clandestine Maoist-style party, which represented a younger generation, and the urban intelligentsia and middle class. Komala had been founded by Nawshirwan Mustafa, who would later become the head of the Goran party, founded in 2009. Gareth R.V. Stansfield, Iraqi Kurdistan: Political Development and Emergent Democracy (London: Routledge, 2010), 91.

- The Al Anfal campaign only drove international condemnation years later, in part because criticism of Saddam for Halabja was deliberately diluted by the US. See oost Hiltermann, A Poisonous Affair: America, Iraq, and the Gassing of Halabja (Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge University Press, 2007).

- For more on the civil war and subsequent division of Iraqi Kurdistan, see Gareth R.V. Stansfield, Iraqi Kurdistan: Political Development and Emergent Democracy (London: Routledge, 2010), 153–57.

- See Iraq’s Constitution of 2005, available at https://www.constituteproject.org/constitution/Iraq_2005.pdf?lang=en (accessed December 21, 2018).

- “Caught in the Whirlwind: Torture and Denial of Due Process by the Kurdistan Security Forces,” Human Rights Watch, July 2007, https://www.hrw.org/reports/2007/kurdistan0707/kurdistan0707web.pdf.

- See Kamal Chomani, “The Challenge Facing Gorran to Change,” Kurdish Policy Foundation, September, 5 2014. https://kurdishpolicy.org/2014/09/05/the-challenges-facing-gorran-to-change/. See also “Iraqi Kurdistan: Civil Society at the Crossroad,” Democracy Digest, June 29, 2017.

https://www.demdigest.org/iraqi-kurdistan-civil-society-crossroads/. - Cale Salih, “Middle East ‘Brain Drain’ Reverses,” Al-Monitor, December 2, 2012, https://www.al-monitor.com/pulse/originals/2012/al-monitor/reversebraindrain.html.

- Pishtiwan Sadiq, interview with the author, Erbil, June 11, 2018.

- “PUK to Keep Grip on Security Forces Even If Defeated in Elections, Official,” Rudaw, January 8, 2018, http://www.rudaw.net/english/kurdistan/08012018.

- “PUK Party to Hold General Congress on Great Uprising Anniversary,” PUK Media, February 15, 2018, https://www.pukmedia.com/EN/EN_Direje.aspx?Jimare=42771. However, the congress was delayed due to intraparty disagreements.

- Saadi, interview with the author, Erbil city, March 2016. We have opted to use first names (or in some cases, no names) only for many of our interviews, to protect the identities of sources who spoke critically of authorities. Interviews were conducted in Kurdish.

- Azad, interview with the authors, Erbil city, March 2016.

- Shakho, interview with the authors, Sulaymaniyah bazaar, March 7, 2017.