“Not only is United States citizenship a ‘high privilege,’ it is a priceless treasure.”—Justice Hugo Black, Johnson v. Eisentrager, 19501

In August 2019, while tens of thousands of migrants per month pushed for entry at the country’s southern border, the president of the United States stood2 before cameras on the South Lawn of the White House and undermined one of the basic tenets of life inside the country’s borders. “We’re looking at birthright citizenship very seriously,” he told journalists. Specifically, he was calling into question the citizenship of children born to non-citizens residing in the United States. “You walk over the border, have a baby—congratulations, the baby is now a U.S. citizen,” he said, adding, “It’s frankly ridiculous.” It was not the first time: a year earlier, he had tweeted a plan to end “so-called Birthright Citizenship.”3 The policy implications of uncertain citizenship are vast, and were evident long before the president’s threats to birthright citizenship.

In fact, Trump’s words reflected a much larger agenda—namely, his administration’s commitment to dismantling not only the rights to but the rights of citizenship. Yet much as Trump’s words seemed to diverge from longstanding principle, the fact is that the tools and premises his administration would use to challenge citizenship had started long before he took office. Their course had been set in the laws and policies of the war on terror. And while much of the work of civil rights advocates succeeded, prior to the Trump administration, in pushing back some of the more aggressive attacks on citizenship and its guarantees, current events point toward a greater reduction of those rights. Of equal concern is just how the dilution of the definition of citizenship will be followed by the continuing reduction of the rights to which citizens are entitled, thus leaving everyone unprotected.

The course of events from 9/11 to the present raises the question of just how strong citizenship protections are, and what reductions in those protections may mean for individual citizens and for the country as a whole.

Erosion of citizenship is a slippery slope. Small erosions of constitutional and citizenship rights set the stage for major rollbacks of sacrosanct protections.

Erosion of citizenship is a slippery slope. Small erosions of constitutional and citizenship rights set the stage for major rollbacks of sacrosanct protections. Our response to the war on terror stripped away constitutional protections in the name of security. Less than two decades after 9/11, once-taboo behavior on the part of the state, and of the executive in particular, has become normal. Historically, America prosecuted rebellious or even treasonous subjects in American courts; today it is politically acceptable to simply strip unpalatable or controversial Americans of their citizenship. Practices including extreme surveillance, torture, extrajudicial detention, and targeted assassination have been made routine first for non-citizens and then for citizens. The courts have occasionally acted as a check on these erosions of citizenship, but judicial restraint has not sufficed to stop the steady decline in the value of citizenship. Unless American laws and American practice radically change, the nature of citizenship in the United States will be conclusively degraded.

The further consequence of the erosion of citizenship rights is the erosion of democracy itself. Unchecked executive powers to define the rights of citizens and the rights to citizenship tear away at the very fabric of the nation’s guarantees of fairness and justice, and thus at the identity of the country. There may be remedies, such as legislation forbidding executive orders—without transparent review ahead of time by a body outside the executive. The courts can offer review as well, but the timelines within which they can work are often too slow to be useful. In any case, however, before any remedy can take place, the incursions on citizenship need to be understood by more than a handful: it needs to become part of the national conversation.

The Rights of Citizenship

More than half a century ago, Earl Warren, chief justice of the United States, defined4 citizenship as “nothing less than the right to have rights.” Under U.S. law, the individuals who have a right to citizenship, and therefore to the rights to which the chief justice referred, include, in the words of the Fourteenth Amendment,5 “All persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof.” Whether born or naturalized in the United States, these persons can expect to have the full set of rights and protections—“privileges or immunities”—set out by American law. Specifically, the Fourteenth Amendment’s Equal Protection Clause forbids the deprivation of “life, liberty, or property, without due process of law” to citizens and “equal protection of the laws” to “any person within its jurisdiction,” citizens and non-citizens alike.

All three of these protections for U.S. citizens enumerated in the Equal Protection Clause—life, liberty and property—were severely harmed in the name of the war on terror. And alongside the diminished protections, access to citizenship itself was also under attack. The first signs of trouble came in the form of incursions into the rights of citizenship.

Liberty: The Cases of Lindh, Hamdi, and Padilla

One of the earliest constitutional protections to crumble in the weeks after 9/11 was the freedom from detention, guaranteed under the Fifth Amendment and protected by the right to challenge one’s detention in court, known as habeas corpus. At first, citizens were exempted from detention policies that focused on Muslim immigrants, legal as well as illegal, who were rounded up and detained without due process. A total of 762 people were detained and 1,200 questioned between6 September 11, 2001, and August 6, 2002, violating the protections owed to those on U.S. soil generally. Citizens themselves were not included in the round-ups. Nor were citizens included in those sent to the country’s new detention facility, Guantanamo Bay,7 where the protections of international, military and domestic law were uncertain.

Before much time had passed, however, the protective mantle of citizenship began to slip away. In late November, 2001, John Walker Lindh, a U.S. citizen who had grown up in Marin County, California, was found among the Taliban and captured after a violent encounter in Afghanistan. Lindh,8 twenty years old when he was captured, had traveled to Afghanistan prior to 9/11, seeking to help oppressed Muslims there. Upon capture, he was deprived of his right to a lawyer, despite the fact that authorities knew that his father, an attorney himself, had hired9 counsel to defend his son. Lindh was subject to “cruel and inhumane treatment,” specifically forbidden under U.S. law. While in U.S. custody,10 he was stripped naked and kept in an iron container, his forehead marked with the word “Shithead.” A bullet was left in his leg for days during his early interrogations. Labelled a “traitor” by leading politicians in both political parties, he found few defenders.

The message was clear; U.S. citizenship, the rights of which include access to a lawyer and freedom from inhumane treatment would not fully protect you if you were alleged to be involved with the terrorist enemy.

Lindh was returned11 to the United States in January 2002, where he forewent a trial and pleaded guilty to charges of supplying services to the Taliban and carrying a weapon during the commission of a felony; he was sentenced to twenty years in prison without ever formally raising the extenuating circumstances of “cruel and inhumane” treatment, which if part of a trial in court could have led to greater leniency, as it did in the case of other terrorism suspects held under cruel conditions. The message was clear; U.S. citizenship, the rights of which include access to a lawyer and freedom from inhumane treatment would not fully protect you if you were alleged to be involved with the terrorist enemy.

Paradoxically, the protections of citizenship were more harmful to Lindh than they would be to another detainee captured alongside him, the dual-citizen Yaser Hamdi.12 Hamdi had been born in Baton Rouge, Louisiana and raised in Saudi Arabia. Originally sent to Guantanamo in April 2002, he was quickly spirited off the island when the U.S. authorities realized that he was indeed a U.S. citizen, as he had claimed since his apprehension in Afghanistan. Rather than enter Hamdi into the criminal justice system, the government labelled him an enemy combatant and placed him in a military brig, without access to a lawyer, without charge, and without the chance for release. Lawyers contested Hamdi’s detention and filed a habeas corpus suit, claiming he was deprived of the rights due to a U.S. citizen.

Hamdi’s case13 reached the Supreme Court, where eight of nine judges decided in his favor on the grounds of rights that adhere to citizenship. The executive, the Court opined, could name a citizen an enemy combatant, but that citizen had the right to challenge their detention in court. The status of being a citizen was crucial to the decision to offer habeas protections. In the words14 of Justice Sandra Day O’Connor, “a state of war is not a blank check for the president when it comes to the rights of the nation’s citizens” (emphasis added).

Despite the insistence on a citizen’s right to due process, the Hamdi decision nevertheless set forth new rules. The government could now, according to the decision, name a citizen an enemy combatant and place him in detention. However, the government had to allow Hamdi, even as an enemy combatant designee, his right to counsel and his right to challenge his detention in court. In Hamdi’s case, rather than allow him the option of filing a habeas petition, the United States returned him to Saudi Arabia,15 where he promptly renounced his citizenship, as per his agreement with the U.S. government.

The June 2004 the Supreme Court ruling on Hamdi v. Rumsfeld, as Hamdi’s case is known, had a chilling effect on the protections due a citizenship—the creation of a new category: that of citizen enemy combatant, a citizen effectively placed outside the protection of the law when it came to detention, but without any firm rules regulating that status. The impact was immediate.

Jose Padilla, a U.S. citizen categorized as Hamdi had been as an enemy combatant, also awaited his fate at the hands of the Supreme Court. Like Lindh, Padilla fared less well than their dual-citizen counterpart, Hamdi, who had been set free. Brooklyn-born and Chicago-raised, Padilla16 was arrested in Chicago, having traveled to Afghanistan and spent time at an al Qaeda training camp. Padilla was initially accused of planning to set off a “dirty bomb,” an act for which he was never formally charged. Padilla was taken out of civilian custody and placed in a military brig. Labelled an “enemy combatant,” he, too, was thereby deprived of the rights of due process for over three years.

Padilla’s detention was challenged, and the Supreme Court addressed the challenge in Rumsfeld v. Padilla, in the same session that it heard the Hamdi case. But rather than order him to be tried or released, as was the case with Hamdi, the high court remanded Padilla’s case to the lower courts on the grounds that the suit needed to be aimed at a different authority—the head of the brig in which he was held, not the Secretary of Defense. Padilla was therefore held in custody in enemy combatant status for three years,17 without the right to a lawyer, to charge, or release, whereas U.S. law customarily requires charge or release within three days. It was a clear violation of rights. As his lawyer Jenny Martinez argued in 2005, “The President has never been granted the authority to imprison indefinitely and without charge an American citizen seized in a civilian setting in the United States. The Constitution allows him no such power.”18

In 2006, Padilla’s case again went before the Supreme Court.19 Rather than risk a decision similar to that of Hamdi, whereby the Court could order his charge or release, the government returned20 Padilla to the criminal justice system, where he was tried on terrorism and conspiracy charges and sentenced to seventeen years, a term later increased21 to twenty-one years. Citizenship offered little protection for Padilla. Soon other constitutional protections began to disappear as well.

How far, then, had the erosion of the rights of citizenship gone? And if the protections of citizenship were fragile when it came to difficult issues, then what would it mean for the larger body politic?

Undermining the Fourth Amendment

Depriving citizens of liberty without due process wasn’t the only area where citizenship protections faltered during the war on terror. In the name of national security, the right to privacy, often in combination with due process violations, was pushed aside as well.

Both secretly and overtly, the White House responded to the 9/11 attacks by creating a series of surveillance policies that exempted U.S. citizens along with non-citizens from the protections of the Fourth Amendments specifically and from the First Amendment effectively.

The White House responded to the 9/11 attacks by creating a series of surveillance policies that exempted U.S. citizens along with non-citizens from the protections of the Fourth Amendments specifically and from the First Amendment effectively.

Under the Fourth Amendment, government agents can’t search or seize a person or property without probable cause of criminal conduct or a warrant. For cases of terrorism and espionage, the standard is lower: the probable conduct needs to address agents of a foreign power, not criminal conduct. Under a statute known as the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act (FISA), a classified court, the FISA court, weighs the evidence in order to consider law enforcement’s requests for authority to surveil a suspect. The USA Patriot Act, passed in late October 2001, gnawed away at these protections offered by the classified judicial process. The act’s highly controversial Section 215, often referred to as the “library records provision,”22 gave the NSA the authority23 to require Internet and phone providers to produce, as The Atlantic summed it up,24 “all call detail records or ‘telephony metadata’ created for communications (i) between the US and abroad or (ii) within the US, including local telephone calls.”25 (Metadata includes identifying information such as originating and terminating number, duration, and the technical identifiers of the transmission.)

The restraint laid down by FISA, prior to the Patriot Act and its Section 215, was meant to reinforce Fourth Amendment protections. With 215, those protections for citizens disappeared. Citing Section 215’s authorization of access to business records “relevant to” an authorized terrorism investigation, the Department of Justice (DOJ) convinced the FISA Court that all phone call records (metadata) were relevant. Quarterly orders from the FISA court subsequently required the tech companies to hand over the data.

It wasn’t until the revelations of Edward Snowden in 2013 that the full extent of the government’s practices of overriding constitutional protections for citizens under the rubric of Section 215 became apparent: the government had used passages of the Patriot Act, a secret October 2001 memo26 from the White House, and a May 2004 legal memo27from Department of Justice to collect call record data in bulk28 from virtually all Americans, and without restraint. Once again, citizenship protections were compromised, and, in the case of surveillance, tossed away, in the name of the national security demands of the war on terror.

Towards the end of Obama’s term, persistent opposition to Section 215 by civil liberties advocates began to bear fruit. In May of 2015, a federal appeals court ruled in ACLU v. Clapper29 that the program as it had been conducted under Section 215 “exceeds the scope of what Congress has authorized and therefore violates Section 215.” It was therefore deemed to be illegal: the bulk telephone metadata collection program was not, in the court’s opinion, authorized by the Patriot Act. The court, however, did not rule on the constitutionality of the program and its implications for Fourth Amendment guarantees, a decision that a few years later would lead to attempts to revive the bulk surveillance power. One month later, the Patriot Act’s metadata surveillance authority was reformed30 under the Patriot Act’s successor, the Freedom Act. The new legislation prohibited bulk metadata collection by the government. Instead, phone companies would store the data and the government would need to obtain FISA court approval to obtain the data. The reform also created a panel of experts to advise on civil liberties concerns.

When it came to other surveillance powers launched by the war on terror, the reduction of constitutional protections was further apparent—and, as it turned out, even longer lasting, than the wide surveillance net of Section 215, even for U.S. citizens. A provision known as Section 702 of the FISA Amendments Act, passed by Congress in 2008, was designed to surveil the content of foreign communications. In practice, 702 enables broad31 NSA surveillance of databases containing the communications of U.S. citizens, either in their calls with individuals overseas, emails, other non-voice content, or inadvertently as part of a wider sweep of communications. As a report32 from the Brennan Center for Justice summarizes, “Although the target must be a foreigner overseas, Section 702 surveillance is believed to result in the ‘incidental’ collection of millions of Americans’ communications. Agencies make broad use of these communications, notwithstanding the fact that Section 702 requires them to ‘minimize’ the retention and sharing of Americans’ information.”

Efforts by the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) to litigate against this foundered in the courts and were ultimately dismissed on the grounds of the “states secrets privilege.”33 But in raising the challenge, the ACLU had raised a point worth considering in the context of citizenship rights overall. The ACLU lawyers included in their argument the notion that the expectation of surveillance, conducted in secret, led to a chilling effect on expression. Was there, in fact, a chilling effect on expression raised by the sense of being watched, and the insistence of the government on keeping secret who and on what grounds it was surveilling?34 Their argument spoke not just to violations of the First Amendment, but also to an undermining of the contract between the government and its citizens. This erosion of trust in the government to protect its citizens and the failure of the government to abide by transparent rules and laws were signs of a slippery slope whose outcome could only be the diminution of citizenship overall.

Constitutional Guarantees

Not surprisingly, the Fifth and Fourth Amendment incursions were matched by other constitutional compromises made in the name of national security after the attacks of September 11, including the right to travel. As with detention, the policy initially targeted non-citizens, and then expanded to citizens. Deviating further from the principle of individualized suspicion, the government relied upon the No Fly List, originally created in 1997, as a subset of the Terrorist Screening Database (TSDB), known as the Watchlist. Both lists include U.S. persons—citizens and legal residents—albeit in much smaller numbers than it includes non-citizens. (In 2016, the No Fly List was estimated35 to include 1,000 citizens among its 81,000 names. In 2017, the Watchlist36 included 4,600 U.S. persons among 1.2 million names total.)

The No Fly List banned those who were suspected of terrorist ties from travelling to or from the country and any of twenty-five countries in the Middle East and Africa. Once again, a policy primarily intended for non-citizens bled over to affect citizens as well. And, once again, the courts were used to challenge the extension of the policy to citizens. In 2006, the Ismail family, who had spent several years in the parents’ native country of Pakistan, attempted to return to their home in Lodi, California, only to be stopped repeatedly at transfer airports and denied access to the flights for which they had bought tickets.37 The TSA refused to provide information on their reasons for banning the family from re-entry. As it turned out, the Ismails had come onto the radar of the FBI as part of a terrorism investigation into the activities of father and son, Umer and Hamid Hayat,38 also residents of Lodi who had spent a long period of time in Pakistan and who had been charged with and convicted of material support for terrorism earlier that year. After a six month delay, in which the Ismails challenged the grounds of their denial for re-entry, the family was allowed to return to the United States.

Nor did efforts to block entry for certain citizens end with the Bush years. In 2011, in the case of Mohamed v. Holder, the court decided that the No Fly List “raises substantial constitutional issues” and therefore merited further review.39 Gulet Mohamed, a naturalized U.S. citizen who had traveled to Yemen, Somalia, and Kuwait in 2009 to study Arabic and meet up with family members, brought suit on the grounds that when he went to the airport in Kuwait40 for a renewal of his visa in 2010, he was detained, interrogated,41 and tortured by the Kuwaiti authorities, accused of knowing al-Awlaki, a U.S. imam who had joined al Qaeda and become a chief spokesman and recruiter. Mohamed claimed that his due process rights had been challenged by his detention and filed a civil action against the government, seeking “meaningful notice of the grounds for his inclusion on the government watch list, and an opportunity to rebut the government’s charges and to clear his name.” He also sought removal “from any watch list or database that prevents him from flying.” Mohamed was allowed to return to the United States in January 2011, within days of filing the complaint. The court eventually ruled in favor of the government in July of 2017, concluding that his rights had not been violated, and the case was dismissed.

In 2013, in Latif v. Holder, the ACLU further challenged the constitutionality of the No Fly List on due process grounds, namely the claim that individuals on the list had insufficient avenues for challenging their placement on the list. A district court ruled in June 2014 that the Constitution does apply when the government bans U.S. citizens from traveling by air. The 2014 ruling was a watershed: according to the court, existing avenues for redress after inclusion on the list did not offer a constitutionally adequate remedy for a U.S. citizen. The ruling declared that the current procedures for placement on the list were unconstitutional, ordered a new process to be created that would overcome these violations, and ordered the government to tell people why they are included on the list and to provide them with the ability to challenge their inclusion on the list. Previously, the U.S. government had tried to dismiss the case on the grounds of standing, because plaintiffs couldn’t prove they were on the list.

The slippery slope had reached a possible turning point. And, years later, in Elhady v. Kable,42 a judge would finally acknowledge the lack of due process available to those seeking to challenge their inclusion on the list. But even as the courts moved, however slowly, in addressing the incursion of rights via the No Fly List, the protections affected by the overall degradation of citizenship rights slipped to the most precious possession of all—one’s life.

Life: Targeted Killings

Taking away freedom and liberties was bad enough, but even worse was the decision that, given the perilous times posed by the war on terror, the executive could decide to take away a citizen’s life without due process. Starting under President Bush, a program of targeted killings emerged as a tool for the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq. Unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs), commonly known as drones, were used sporadically in the later years of the Bush presidency to kill designated enemies abroad. But it was in the administration of Barack Obama that the use of drones became a preferred tactic for combat in the war on terror. In Pakistan, Yemen, and Somalia, as well as Afghanistan and Iraq, lethal drones were used to target and kill individuals and groups determined to be terrorists. As an accompaniment to this program, lawyers in Obama’s Department of Justice drafted language authorizing the use of drones to kill American citizens.

Taking away freedom and liberties was bad enough, but even worse was the decision that, given the perilous times posed by the war on terror, the executive could decide to take away a citizen’s life without due process.

The memos were drafted for one citizen in particular—Anwar al-Awlaki. Al-Awlaki had been a successful imam in the United States throughout the 1990s and 2000s. In 2004, he chose to go to Yemen, where he became a leading figure in the al Qaeda network, inspiring others globally to join al Qaeda’s fight against the United States and the West. Labelled the “bin Laden of the Internet,” al-Awlaki’s influence was considered to be immense.

Leading national security officials argued that al-Awlaki posed a “continued and imminent” threat and had determined that his capture was infeasible. But his status as an American citizen at first gave some pause for thought. The question boiled down to this: Could the executive order the killing of a U.S. citizen without first granting him due process, i.e., the ability to challenge his designation as a terrorist?

Justice Department lawyers once again relied upon the Hamdi decision’s implications for citizenship. Citing Hamdi, the lawyers asserted the government’s right to consider al-Awlaki an enemy combatant.43 The killing authority took its cues, in other words, from the detention authority. “[J]ust as the AUMF [2001 Authorization for the Use of Military Force] authorizes the military detention of a U.S. citizen captured abroad who is part of an armed force within the scope of the AUMF,” wrote the memo’s author David Barron, “it also authorizes the use of ‘necessary and appropriate’ lethal force against a U.S. citizen who has joined such an armed force.” According to the memo, “we do not believe al-Awlaki’s citizenship provides a basis” for exempting him from killing. The memo reasoned that although unlawful killings of U.S. nationals abroad by U.S. nationals was proscribed, al-Awlaki’s killing would not be unlawful, given the threat he posed.

Learning from the Washington Post about the placement of al-Awlaki on a “kill list,” al-Awlaki’s father sued44 the government on his son’s behalf, hoping to prevent the targeting of his son, but to no avail. The courts concluded that al-Awlaki’s father did not have standing to bring the suit, deferring in essence to the government’s claim of national security as a basis for al-Awlaki’s inclusion on the kill list.45 Al-Awlaki was killed by drone on September 30,46 and U.S. citizen Samir Khan, the editor of the online jihadist magazine Inspire, was also killed. Two weeks later, al-Awlaki’s sixteen-year-old son, also a U.S. citizen, was killed by drone strike, as well (although authorities say it was not an intended killing). Subsequent suits brought on the grounds that al-Awlaki, his son, and Samir Khan were deprived due process were later dismissed.47 In 2017, al-Awlaki’s eight-year-old daughter,48 also a U.S. citizen, was killed in a United States–United Arab Emirates military raid on al Qaeda in southern Yemen, seemingly as part of an attack on a compound49 that was said to harbor members of al Qaeda. Al-Awlaki’s daughter apparently was not the intended target of the attack.

The al-Awlaki memo led to his killing.50 Put legally and philosophically, the authorization for killing an American citizen was a continuation of the erosion of citizenship rights for those alleged to be supporters of Islamist terrorism. As such, it suggests a causal link between certain behavior and the loss of effective citizenship. Al-Awlaki, the lawyers were essentially arguing, didn’t deserve the protections of citizenship. In effect, though they didn’t say it, he had traded in his citizenship be virtue of joining the enemy.

The removal of rights owed to citizens in the areas of life, liberty, privacy, and property had moved far away from the protections in place on the eve of 9/11. The slippery slope depriving citizens of their rights did find some impediments in the successful cases argued by civil liberties advocates; but their efforts were not enough to turn the tide back to the guarantees of life and liberty that were constitutionally due to U.S. citizens. In fact, as the rhetoric surrounding the government’s defense of the decision to kill al-Awlaki indicated, the slippery slope from extralegal detention to taking of life without due process was headed further away from legal protections—toward the removal of citizenship entirely.

The Right to Citizenship

Losing Citizenship

As profound as the erosion of constitutional protections were, there was something with even deeper implications afoot. Even as the rights and protections of citizenship were being degraded, a number of politicians called for the expatriation, whether natural-born or naturalized, of those who belonged to a terrorist organization or who engaged in or supported terrorism.

Under U.S. law, the only way to give up one’s citizenship is to do so voluntarily. In one of the decisive cases on the matter, Trop v. Dulles, the Justices concurred51 that loss of citizenship was “a form of punishment more primitive than torture.” In Chief Justice Earl Warren’s words, “the deprivation of citizenship is not a weapon that the Government may use to express its displeasure at a citizen’s conduct, however reprehensive that conduct may be.” For naturalized citizens, fraud on the application for citizenship can also be used as a means to start denaturalization proceedings. But other than findings of fraud, American-born citizens and naturalized citizens cannot lose their citizenship status unless and until they voluntarily choose to give it up. As law professor Steve Vladeck explains, “[E]ven a treason conviction won’t suffice absent proof that the defendant specifically intended not just to commit treason, but to surrender his citizenship.”

But things have changed. Throughout the 2000s and 2010s, a parade of legislation entered Congress which, while failing in its goals, all aimed to accelerate the erosion of citizenship. Despite standing law, in 2003, Senators Jeff Sessions (R-AL), Zell Miller (D-GA), Larry E. Craig (R-ID), and James M. Inhofe (R-OK) introduced52 the Domestic Security Enhancement Act, commonly referred to as Patriot Act II. The proposed bill added several draconian features53 to the Patriot Act. It aimed to strip Americans of their citizenship if they were found to be a member of a terrorist organization or if they were found to have provided material support to terrorists. In addition, the bill called for a virtual removal of due process guarantees in the name of terrorism: suspects were to be detained upon suspicion of terrorism rather than evidence. The bill included several passages specifically aimed at citizens, including allowing grand jury information on U.S. citizens to be shared with foreign governments. The bill, secret at first, was leaked to the public, and effectively failed as a result.

But the desire to equate terrorism with abandonment of citizenship persisted. During the Obama years, versions of the expatriation acts were repeatedly introduced in Congress. In 2010, Senators Joe Lieberman (D-CT) and Scott Brown (R-MA) proposed the Terrorist Expatriation Act (TEA), intended to amend the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1940 and add reasons for loss of citizenship. These included,54 as its Patriot II predecessor had, the loss of citizenship for providing material support to a foreign terrorist organization, engaging in hostilities against the United States, and “engaging in hostilities against any country or armed force that is directly engaged along the United States.” In 2011, Lieberman proposed yet another version55 of the bill, The Enemy Expatriation Act, which was introduced simultaneously with an identical56 bill in the House by Representative Charles Dent (R-PA). The act further made it the Secretary of State who would determine that a citizen provided material support to a terrorist organization. Both the Senate and House bills died in committee.

President Obama curtailed some of the worst excesses of the George W. Bush administration, for example ending White House support for torture. But Obama did not challenge the growing security measures designed to counter terrorism and the historical upswing of executive authority. As a result, by the latter years of the Obama presidency, after more than a decade of the war on terror, the protections of citizenship had effectively been watered down. Owing to the courts, and the work of civil liberties acts, the damage had been less comprehensive than originally intended by both overt and secret law and policy. Yet, when Trump rose to the presidency in 2016, the constitutional violations and compromises that had been made, even those that had been partially rolled back, set the stage for aggressive attempts to reduce the promises and protections of citizenship even further, and to do so for the future as well as the present.

Trump and Citizenship

When President Trump came into office, the seeds for compromising citizenship guarantees had been sown. From the get-go, the administration began to build upon earlier efforts to take citizenship away on the grounds of terrorism, and it wasn’t long before the reasons for removing citizenship spread to those other than terrorists as well.

Seeing an opportunity in the new administration, legislators revived the calls for the Expatriate Terrorist Act within weeks of the Trump inauguration—a bill that, again, did not pass. In February 2017, Senators Chuck Grassley (R-IA) and Mike Lee (R-UT) joined Senator Ted Cruz (R-TX) to re-introduce the bill57 to justify removal of citizenship from citizens who had become a member of or a terrorist organization. As the bill’s text explained, citizens who joined a Foreign Terrorist Organization (FTO) were effectively deemed to have voluntarily renounced their citizenship. Proposals for a Domestic Terrorism Statute aiming to establish laws against domestic terrorists along the lines of those used to prosecute international terrorists has been introduced by Senators Martha McSally (R-AZ) and Congressman Adam Schiff (D-CA). Under the policies derived from a new domesticc terrorism law, would citizens accused of domestic terrorism also lose their citizenship?58

Authorities used other avenues to effectively remove citizenship from those who joined a terrorist organization. The case of Doe v. Mattis revealed the new administration’s intentions when it came to those who fought abroad alongside ISIS.

In the fall of 2017, the U.S. military took into custody a person referred to as John Doe, a dual United States–Saudi Arabia citizen who had been born in the United States, grew up in Saudi Arabia, and gone to college in the United States. Doe had joined ISIS and then fought for the Syrian Democratic Forces. His name was later revealed to be Abdulrahman Ahmad Alsheikh. Word of his capture leaked out, and the ACLU filed a habeas suit, challenging the detention of the U.S. citizen on the grounds that under federal law, a U.S. citizen cannot be detained without criminal charges.59 The suit challenged the use of a sixteen-year-old statute, the AUMF, and asserted Alsheikh’s right to challenge his detention.

The government sought to forcibly transfer Alsheikh to a third country, but a court prohibited it, requiring seventy-two-hour notice prior to transfer. The government gave notice, under these conditions, of their plan to send him to Syria where, given the war, his life most certainly would have been in danger. Again, the ACLU protested.60 “We know of no instance—in the history of the United States—in which the government has taken an American citizen found in one foreign country and forcibly transferred her to the custody of another foreign country.”61 By mutual agreement Alsheikh was eventually transferred to Bahrain. His due process rights as a citizen, clarified in the Hamdi case, had protected him from transfer to Syria, as the government had originally proposed. However, the government took away his passport, although according to the New York Times, “it did not relinquish his citizenship as part of the release deal.”62 Without a passport, Alsheikh could not return to the United States.

As the removal of the passport indicated, Doe v. Mattis opened up much larger questions: Would U.S. citizen foreign fighters be allowed to return to the United States? Under Presidents Bush and Obama, citizens charged with fighting abroad in the war on terror were brought back to federal court for trial. Under Trump, the government sought to limit this pathway. The Doe v. Mattis case had made this clear. So, too, did the case of Hoda Muthana, who, unlike Alsheikh, was not a dual citizen.

Muthana was born in the United States to a Yemeni diplomat. She had grown up in Hoover,63 Alabama and in 2014 traveled abroad to join ISIS in Syria. Up until that point, her citizenship had never been in question—she held a U.S. passport—but that changed when she requested to be allowed to come back from Syria. Muthana agreed to “face the consequences of her action” in the United States. Nevertheless, the U.S. government protested, claiming that she was not actually a citizen, asserting that she had been born during the period in which her father still held a diplomatic visa despite the fact that his term as a UN diplomat had terminated prior to her birth. The Trump administration claims the Muthana case is not an example of citizenship-stripping, arguing that Muthana had never had citizenship in the first place. Muthana continues to linger with her son in a refugee camp in northern Syria while her lawyers continue to fight for her admission to the United States.

The United States government has preserved its respect for citizenship rights in some areas. Contrary to their treatment of Muthana, the United States has signaled at least some willingness to bring back the wives and children of foreign fighters. In June 2019, eight Americans who were found among ISIS detainees in Syria,64 two women and six minors, were resettled in the United States. Relatively few others who have returned have been prosecuted in court. Of the approximately 130 U.S. citizens who have gone abroad to join ISIS, only seven of the fighters have returned65 and faced prosecution.

While Muthana is fighting to return to the country, authorities are working to expel from the United States others associated with organizations designated as terrorist enemies; naturalized citizens convicted of terrorism in the years since 9/11 are now facing the prospect of denaturalization. Under President Trump, efforts to denaturalize citizens have escalated. During his tenure as attorney general (February 2017 to November 2018), Jeff Sessions made it a point to emphasize his commitment to denaturalizing those convicted on terrorism charges. “The Justice Department is committed,” Sessions said66 in April 2017, “to protecting our nation’s national security and will aggressively pursue denaturalization of known or suspected terrorists.” The push for denaturalization built upon an earlier program67 that had begun under President Obama and that examined cases of immigration fraud that could be linked to terrorism. That month, Sessions’s DOJ succeeded in getting a court to revoke the citizenship on civil grounds of Khaled Abu al-Dahab,68 a naturalized citizen who had confessed to recruiting for al Qaeda in California and who had been convicted on terrorism charges in Egypt.

In addition to denying re-entry to citizens who had been convicted of supporting terrorism abroad, the government looked to take away citizenship from naturalized citizens who had been convicted of terrorism at home, and were serving sentences in the United States. We can consider Iyman Faris as an example. Faris is an American citizen who was born in Pakistan and naturalized69 in December 1999. Faris, who had met with bin Laden in Afghanistan, had been convicted70 in 2003 of plotting to use gas torches to blow up the Brooklyn Bridge, a crime to which he pled guilty. Faris was sentenced to twenty years in prison and is scheduled for release in December 2020. The U.S. government has been trying for years to block his release onto U.S. shores. Towards this end, they have engaged in numerous attempts71 to denaturalize him and then deport him.

In March 2017, Jeff Sessions’s Justice Department filed suit to revoke Faris’s citizenship on the grounds that he procured U.S. citizenship unlawfully and that his involvement with al Qaeda violated his oath of allegiance to the United States. In May of 2019, Attorney General William Barr’s DOJ, three months into his tenure as attorney general, filed a new motion72 seeking to denaturalize Faris, claiming that Faris’s association with al Qaeda proved that Faris “was not attached to the principles of the Constitution or well disposed to the good order and happiness of the United States, which are required to naturalize.” The case is now in litigation.

The Trump era’s compromises to citizenship rights and protections have extended beyond the DOJ. In August 2019, in one of his last acts as director of national intelligence, Dan Coats sent a letter73 to Congress, announcing that the administration would be seeking to make the bulk metadata collection program permanent, despite the fact that technical problems continued to compromise74 the lawful operation of the program.

Meanwhile, the courts, as during earlier administrations, have made some significant headway in protecting the rights of citizens. On September 4, 2019, in the case of Elhady v. Kable, a court ruled75 that the Terrorist Screening Database (TSDB), also known as the Watchlist, was unconstitutional. The case was initiated when twenty-three U.S. citizens brought suit challenging their inclusion in the database, claiming they had been deprived of due process and could not challenge it. The “vagueness for the standard for inclusion, coupled with the lack of any meaningful restraint on what constitutes grounds for placement on the Watchlist . . . is precisely what offends the Due Process Clause,” wrote U.S. District Court Judge Anthony Trenga. This case,76 Judge Trenga opined, questions whether individuals on the TSDB have “a constitutionally adequate opportunity to challenge their presumed inclusion on the TSDB.” The judge declared their inability to challenge their inclusion on the list to be unconstitutional.

Victories like these, however, have not been enough to stop the erosion: the overall trend continues to be one of the loss of rights, and of their defense or reassertion.

Beyond Terrorism: The Implications of These Attacks on Citizenship

The Trump administration has relied upon the past two decades’ legislation and executive action, as they have evolved for the purposes of the war on terror, and has degraded citizenship and made those policies a blueprint for larger-scale forms of discrimination, removal of rights, and narrowing access to the status of citizen. At the southern border, the administration has pursued denaturalization hearings for thousands. Denaturalization, though limited by definition, can by established law occur either as the result of a criminal proceeding or a civil action.

Under Operation Janus, which started under President Obama and which has ramped up under Trump, officials have been ordered to review hundreds of thousands of immigration cases, looking for instances of fraud that could be used as grounds for the removal of citizenship status. For 2019, the administration sought over $200 million to investigate a reported 900 new leads on those potentially vulnerable to denaturalization, and announced plans to review another 700,000 immigrant files.77 Meanwhile, the government has also looked to tighten pathways to citizenship, thus further altering the definition of citizenship in the United States. As an example, immigrants who serve in the U.S. armed forces, once a pathway to citizenship, are not being granted78 citizenship with nearly the same frequency as has been customary in the past.

This activity indicates where the pattern of erosion described in this report is headed next. Throughout the nation’s history, citizenship has gone largely unquestioned in the United States. And when it has been undermined, the deviant policies have eventually—even if decades later—been overturned. Yet, since 9/11, citizenship, both in terms of its definition, and what rights it confers, has been under steady attack as one right after another has been compromised, often in secret, often first for aliens and immigrants, and then for citizens themselves.

The policy implications of this pattern are vast. Unless and until the government agrees to take its hands off of citizenship, the very fabric of the social contract is at risk. When it comes to “life, liberty and property,” the refusal of a government to protect its own sends a signal to all. Mission creep to other groups, and on added grounds, is no longer a question of if, but when. The exceptionalism that the United States has often embraced in terms of rights and liberties is cascading away.

Moreover, unsettling a populace’s sense of reliable protections comes with a price. If the government doesn’t abide by the law, will citizens begin to look elsewhere for protection, and eschew traditional institutions to resolve civic issues? Will they, at the very least, be increasingly alienated from a sense of trust in the government? Once the government can take away certain rights, how insecure are other rights? Where is the end to the slippery slope? Put simply, the erosion of these rights amounts to the erosion of democracy.

The largest consequence of all, however, is the deeper erosion of the balance of powers that undergirds American democracy. When it comes to both the rights to citizenship as well as the rights of citizenship, the checks and balances traditionally exercised by the courts and by Congress have faded into virtual irrelevance. The courts provide insufficient remedy: they not only take a very long time to render decisions that can curtail or stop government incursion on rights, but also, and all too often, defer to the executive, as happened with Hamdi and Padilla, with al-Awlaki and more. Congress has proven just as unhelpful. Although several measures, such as the Expatriation Act, have failed to pass, efforts in Congress to seek accountability by increasing oversight have made little headway.

But perhaps the most compelling takeaway is that the enhanced powers given to the executive branch, and in particular to the office of the president since 9/11, have been strengthened by each one of these cuts to the balance of powers doctrine established in the Constitution.

The remedy that stems this tide will be neither simple nor quick, which makes getting started on it even more urgent. It should begin with a recognition that executive power to make policy decisions about constitutional issues should be transparent at the outset, and checked in real time, not just by government lawyers who will do the president’s bidding, but also by constitutional scholars and civil liberties advocates who can make the case against the erosion of rights at the time policy is formulated. Bush claimed the power to define the power to define who was an enemy combatant, Obama who would be placed on the kill list, and Trump who would be forbidden entry into the country, or expelled from it. The ultimate remedy would involve a curb on the presidential power to make policy unilaterally in secret and without a full-spectrum review. For starters, executive orders aimed at curtailing citizenship rights, declared all too easily as answering to an emergency, might be restricted by legislative action.

In 1950, Supreme Court Justice Hugo Black warned his fellow Americans about the consequences that detention without due process could one day unleash. He was speaking about enemy aliens whose rights had been violated by detention without due process by U.S. authorities. “Not only is United States citizenship a ‘high privilege,’ it is a priceless treasure,” he wrote.

Black was dissenting from the majority opinion in Johnson v. Eistentrager,79 which held that U.S. courts did not have jurisdiction over enemy alien prisoners who had been tried and convicted by a U.S. military commission in China for violating the laws of war, and were in an military prison in Germany. Justice Black’s worry was that the decision, which denied habeas rights to those prisoners, was part of a slippery slope. Violations in the realm of detention, albeit for aliens, could one day lead to the removal of rights for citizens.

Seventy-years later, Justice Black’s insights have proven uncannily wise. Once the rights of the constitution are compromised for some, those rights stand over time to be reduced for all. In today’s context., from the detention of enemy combatants at Guantanamo, to the detention of enemy citizens on U.S. soil, to aggressive denaturalization programs, the idea of citizenship as a meaningful doorway to safety and security has continued to fade away, and with far too little notice.

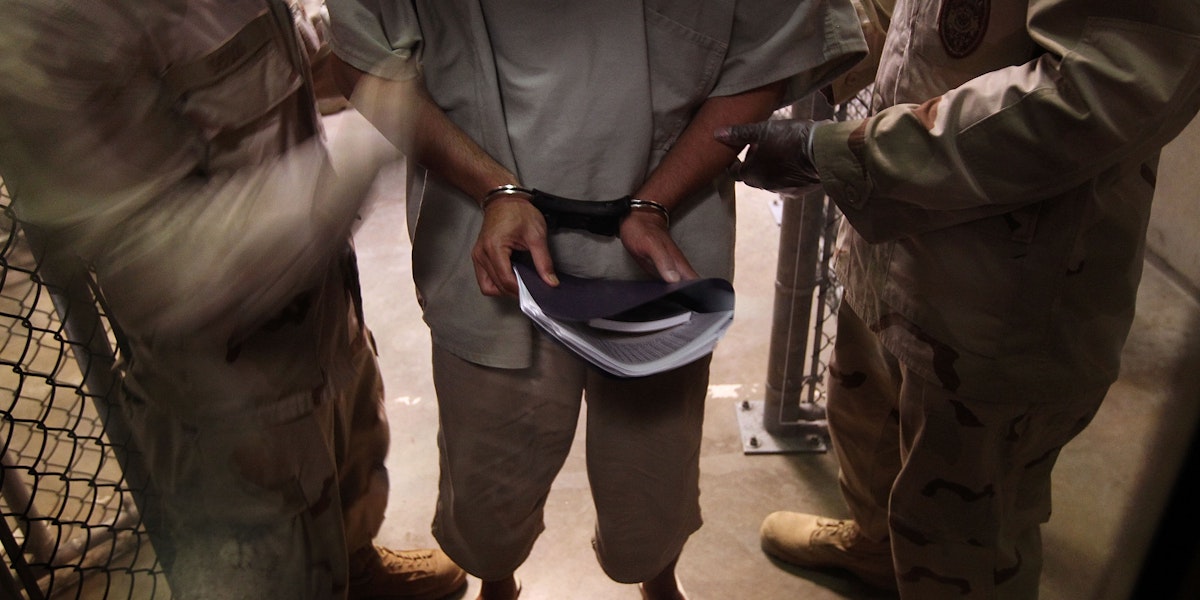

Cover Photo: U.S. Navy guards escort a detainee after a “life skills” class held for prisoners at Camp 6 in the Guantanamo Bay detention center in Guantanamo Bay, Cuba. Source: John Moore/Getty Images

Notes

- Johnson v. Eisentrager, 339 U.S. 763 (1950).

- “Remarks by President Trump before Marine One Departure,” The White House, August 21, 2019, https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefings-statements/remarks-president-trump-marine-one-departure-60/.

- Donald J. Trump, Twitter account @realdDonaldTrump, 9:25a.m., October 31, 2018, https://twitter.com/realDonaldTrump/status/1057624553478897665.

- Perez v. Brownell, 356 U.S. 44 (1958), https://www.law.cornell.edu/supremecourt/text/356/44.

- U.S. Constitution, amend. 14.

- U.S. Department of Justice, Office of the Inspector General, The September 11 Detainees: A Review of the Treatment of Aliens Held on Immigration Charges in Connection with the Investigation of the September 11 Attacks (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Justice, 2003), https://oig.justice.gov/special/0306/full.pdf.

- Karen Greenberg, The Least Worst Place: Guantanamo’s First 100 Days (New York: Oxford University Press, 2010), 50–63, 143–62.

- Carol Rosenberg, “John Walker Lindh, Known as the ‘American Taliban,’ Is Set to Leave Federal Prison This Week,” New York Times, May 21, 2019, https://www.nytimes.com/2019/05/21/us/politics/american-taliban-john-walker-lindh.html.

- Dan De Luce, Robbie Gramer, and Jana Winter, “Detainee #001 in the Global War on Terror, Will Go Free In Two Years. What Then?” Foreign Policy, June 23, 2017, https://foreignpolicy.com/2017/06/23/john-walker-lindh-detainee-001-in-the-global-war-on-terror-will-go-free-in-two-years-what-then/.

- Nick Ryan, “Sympathy for the devil: Fighting to release John Walker Lindh, the American Taliban,” The Telegraph, January 8, 2009, https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/worldnews/northamerica/usa/4175882/Sympathy-for-the-devil-Fighting-to-release-John-Walker-Lindh-the-American-Taliban.html.

- Karen J. Greenberg, Rogue Justice: The Making of the Security State (New York: Crown, 2016), 43–53.

- “The Guantanamo Docket: Yaser Esam Hamdi,” New York Times, https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/projects/guantanamo/detainees/9-yaser-esam-hamdi.

- Hamdi v. Rumsfeld, 542 U.S. 507 (2004), https://www.lawfareblog.com/hamdi-v-rumsfeld-542-us-507-2004.

- Ibid.

- “Hamdi to be freed this week, lawyer says,” NBC News, September 27, 2004, http://www.nbcnews.com/id/6116717/ns/us_news-security/t/hamdi-be-freed-week-lawyer-says/#.XYPPzpNKjOR.

- Abby Goodnough and Scott Shane,“Padilla Is Guilty on All Charges in Terror Trial,” New York Times, August 17, 2007, https://www.nytimes.com/2007/08/17/us/17padilla.html.

- Brief for Petitioner-Appellee, Jose Padilla v. C.T. Hanft, U.S.N. Commander, Consolidated Naval Brig, No 05-6396 (filed June 6, 2005), https://www.legal-tools.org/doc/bb0285/pdf/.

- Brief for Petitioner-Appellee, Jose Padilla v. C.T. Hanft, U.S.N. Commander, Consolidated Naval Brig, No 05-6396 (filed June 6, 2005), https://www.legal-tools.org/doc/bb0285/pdf/.

- Padilla v. Hanft, 547 U.S. 1062 (2006), https://www.supremecourt.gov/opinions/05pdf/05-533Kennedy.pdf.

- David Stout. “Justices, 6-3, Sidestep Ruling on Padilla Case,” New York Times, April 3, 2006, https://www.nytimes.com/2006/04/03/us/03cnd-scotus.html.

- “Convicted terrorist Padilla given new 21-year sentence,” BBC News, September 9, 2014, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-us-canada-29131833.

- April Glaser, “Long Before Snowden, Librarians Were Anti-Surveillance Heroes,” Slate, June 3, 2015, https://slate.com/technology/2015/06/usa-freedom-act-before-snowden-librarians-were-the-anti-surveillance-heroes.html.

- Uniting and Strengthening America by Providing Appropriate Tools Required to Intercept and Obstruct Terrorism (USA PATRIOT ACT) Act of 2001, 107th Cong., 1st sess. (October 26, 2001), https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/BILLS-107hr3162enr/pdf/BILLS-107hr3162enr.pdf.

- Abby Ohlheiser, “The NSA Is Collecting Phone Records in Bulk,” The Atlantic, June 5, 2013, https://www.theatlantic.com/national/archive/2013/06/nsa-collecting-phone-records-bulk/314541/.

- Uniting and Strengthening America by Providing Appropriate Tools Required to Intercept and Obstruct Terrorism (USA PATRIOT ACT) Act of 2001, 107th Cong., 1st sess. (October 26, 2001), https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/BILLS-107hr3162enr/pdf/BILLS-107hr3162enr.pdf.

- “(U) Annex to the Report on the President’s Surveillance Program,” Offices of Inspectors General, Department of Defense, Department of Justice, Central Intelligence Agency, National Security Agency, Office of the Director of National Intelligence, Report No. 2009-0013-AS, July 10, 2009, https://oig.justice.gov/reports/2015/PSP-09-18-15-vol-III.pdf.

- Memorandum from Jack L. Goldsmith, III, Assistant Attorney General, U.S. Department of Justice, to the Attorney General, May 6, 2004, 21–24, https://www.aclu.org/sites/default/files/assets/olc_stellar_wind_memo_-_may_2004.pdf.

- Spencer Ackerman, “Snowden disclosures helped reduce use of Patriot Act provision to acquire email records,” The Guardian, September 29, 2016, https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2016/sep/29/edward-snowden-disclosures-patriot-act-fisa-court.

- ACLU v. Clapper, 785 F.3d 787 (2d Cir. 2015), https://www.aclu.org/sites/default/files/field_document/clapper-ca2-opinion.pdf.

- Charlie Savage, “Trump Administration Asks Congress to Reauthorize N.S.A.’s Deactivated Call Records Program,” New York Times, August 15, 2019, https://www.nytimes.com/2019/08/15/us/politics/trump-nsa-call-records-program.html.

- “Warrantless Surveillance under Section 702 of FISA,” ACLU, https://www.aclu.org/issues/national-security/privacy-and-surveillance/warrantless-surveillance-under-section-702-fisa.

- “Foreign Intelligence Surveillance (FISA Section 702, Executive Order 12333, and Section 215 of the Patriot Act): A Resource Page,” Brennan Center for Justice, October 25, 2018, https://www.brennancenter.org/analysis/foreign-intelligence-surveillance-fisa-section-702-executive-order-12333-and-section-215.

- Patrick Toomey and Asma Peracha, “The NSA Is Using Secrecy to Avoid a Courtroom Reckoning on Its Global Surveillance Dragnet,”ACLU National Security Project, June 29, 2018, https://www.aclu.org/blog/national-security/privacy-and-surveillance/nsa-using-secrecy-avoid-courtroom-reckoning-its.

- “Plaintiffs’ Memorandum of Law in Opposition to Defendants’ Motion to Dismiss” at 12-13, 41-42, Wikimedia Foundation v. National Security Agency, No. 15-cv-0062-TSE (D. Md. Sept. 3, 2015), available at https://www.aclu.org/legal-document/wikimedia-v-nsa-plaintiffs-memorandum-law-opposition-defendants-motion-dismiss.

- Stephen Dinan, “FBI no-fly list revealed: 81,000 names, but fewer than 1,000 Americans,” Washington Times, June 20, 2016, https://www.washingtontimes.com/news/2016/jun/20/fbi-no-fly-list-revealed-81k-names-fewer-1k-us/.

- Elhady v. Kable, Civil Action No. 1:16-cv-375 (AJT/JFA), 2019 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 152526 (E.D. Va. September 4, 2019), https://int.nyt.com/data/documenthelper/1689-terror-watchlist-ruling/75cd50557652ad0bfa2a/optimized/full.pdf#page=1.

- Jeffrey Kahn, Mrs. Shipley’s Ghost: The Right to Travel and Terrorist Watchlist (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2013), 36-42.

- “U.S. Citizens are Allowed to Return Home,” ACLU of Northern California, October 2, 2006, https://www.aclunc.org/blog/us-citizens-exiled-are-allowed-return-home

- See Mohamed v. Holder, 1:11-CV-50 AJT/TRJ, 2011 WL 3820711 (E.D. Va. Aug. 26, 2011), https://www.clearinghouse.net/chDocs/public/NS-VA-0004-0002.pdf.

- Glenn Greenwald, “Under Suspicious Circumstances, FBI Places Brother of No-Fly Litigant on Most Wanted Terrorist List,” The Intercept, January 30, 2015, https://theintercept.com/2015/01/30/day-key-hearing-fbi-places-brother-fly-litigant-wanted-list/.

- Mark Mazzetti, “Detained American Says He Was Beaten in Kuwait,” New York Times, January 5, 2011, https://www.nytimes.com/2011/01/06/world/middleeast/06detain.html?_r=1&hp.

- Elhady v. Kable, Civil Action No. 1:16-cv-375 (AJT/JFA), 2019 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 152526 (E.D. Va. Sep. 4, 2019).

- Memorandum from the U.S. Department of Justice Office of Legal Counsel to the Office of the Assistant Attorney General, July 16, 2010, https://lawfare.s3-us-west-2.amazonaws.com/staging/s3fs-public/uploads/2014/06/6-23-14_Drone_Memo-Alone.pdf.

- Jameel Jaffer, The Drone Memos: Targeted Killing, Secrecy and the Law (New York: The New Press, 2016), 1–8.

- Charlie Savage, “Relatives of Victims of Drone Strikes Drop Appeal,” New York Times, June 3, 2014, https://www.nytimes.com/2014/06/04/us/relatives-of-victims-of-drone-strikes-drop-appeal.html.

- Scott Shane, “The Lessons of Anwar al-Awlaki,” New York Times, August 27, 2015, https://www.nytimes.com/2015/08/30/magazine/the-lessons-of-anwar-al-awlaki.html.

- Karen McVeigh, “Families of US citizens killed in drone strike file wrongful death lawsuit,” The Guardian, July 18, 2012, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2012/jul/18/us-citizens-drone-strike-deaths.

- Robert Windrem (et. al), “SEAL, American Girl Die in First Trump-Era U.S. Military Raid,” NBC News, January 30, 2017, https://www.nbcnews.com/news/world/seal-american-girl-die-first-trump-era-u-s-military-n714346.

- Glenn Greenwald, “Obama Killed a 16-Year-Old American in Yemen. Trump Just Killed His 8-Year-Old Sister,” The Intercept, January 30, 2017, https://theintercept.com/2017/01/30/obama-killed-a-16-year-old-american-in-yemen-trump-just-killed-his-8-year-old-sister/.

- cott Shane, “The Lessons of Anwar al-Awlaki,” New York Times, August 27, 2015, https://www.nytimes.com/2015/08/30/magazine/the-lessons-of-anwar-al-awlaki.html.

- Trop v. Dulles, 356 U.S. 86 (1958), http://global.oup.com/us/companion.websites/fdscontent/uscompanion/us/static/companion.websites/9780199751358/instructor/chapter_8/tropv.pdf.

- Homeland Security Enhancement Act of 2003, S. 1906, 108th Cong. (2003), https://www.congress.gov/bill/108th-congress/senate-bill/1906/cosponsors.

- “ACLU Fact Sheet on Patriot Act II,” ACLU, accessed September 19, 2019, https://www.aclu.org/other/aclu-fact-sheet-patriot-act-ii.

- Terrorist Expatriation Act, H.R.5237, 111th Cong. (2010), https://www.congress.gov/bill/111th-congress/house-bill/5237.

- Enemy Expatriation Act, S.1698, 112th Cong. (2012), https://www.congress.gov/bill/112th-congress/senate-bill/1698.

- Enemy Expatriation Act, H.R.3166, 112th Cong. (2011), https://www.congress.gov/bill/112th-congress/house-bill/3166.

- Expatriate Terrorist Act, S. 361, 115th Cong. (2017), https://www.congress.gov/bill/115th-congress/senate-bill/361/cosponsors.

- “Proposed Bills Would Help Control Domestic Terrorism, Lawfare, August 20, 2019, https://www.lawfareblog.com/proposed-bills-would-help-combat-domestic-terrorism.

- “Doe v. Mattis—Challenge to Detention of American by U.S. Military Abroad,” ACLU, https://www.aclu.org/cases/doe-v-mattis-challenge-detention-american-us-military-abroad.

- “Doe v. Mattis—Challenge to Detention of American by U.S. Military Abroad,” ACLU, https://www.aclu.org/cases/doe-v-mattis-challenge-detention-american-us-military-abroad.

- Jonathan Hafetz, “U.S. Citizen, Detained Without Charge by Trump Administration for a Year, Is Finally Free,” ACLU, October 29, 2018, https://www.aclu.org/blog/national-security/detention/us-citizen-detained-without-charge-trump-administration-year.

- Charlie Savage, Rukmini Callimachi, and Eric Schmidt, “American ISIS Suspect Is Freed After Being Held More Than a Year,” New York Times, October 29, 2018, https://www.nytimes.com/2018/10/29/us/politics/isis-john-doe-released-abdulrahman-alsheikh.html.

- Felicia Sonmez and Michael Brice-Saddler, “Trump says Alabama woman who joined ISIS will not be allowed back into U.S.,” Washington Post, February 20, 2019, https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/trump-says-alabama-woman-who-joined-isis-will-not-be-allowed-back-into-us/2019/02/20/64be9b48-3556-11e9-a400-e481bf264fdc_story.html.

- Robin Wright, “Despite Trump’s Guantanamo Threats, Americans Who Joined ISIS Are Quietly Returning Home,” The New Yorker, June 11, 2019, https://www.newyorker.com/news/news-desk/americas-isis-members-are-coming-home.

- “Beyond the Caliphate: Foreign Fighters and the Threat of Returnees,” The Soufan Center, October 2017, https://thesoufancenter.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/Beyond-the-Caliphate-Foreign-Fighters-and-the-Threat-of-Returnees-TSC-Report-October-2017-v3.pdf.

- “Justice Department Secures the Denaturalization of a Senior Jihadist Operative Who Was Convicted of Terrorism in Egypt,” Press Release, Department of Justice Office of Public Affairs, April 20, 2017, https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/justice-department-secures-denaturalization-senior-jihadist-operative-who-was-convicted.

- Cassandra Burke Robertson and Irina D. Manta, “(Un)Civil Denaturalization,” New York University Law Review, 2019, https://scholarlycommons.law.case.edu/faculty_publications/2026/.

- “Justice Department Secures the Denaturalization of a Senior Jihadist Operative Who Was Convicted of Terrorism in Egypt,” Press Release, Department of Justice Office of Public Affairs, April 20, 2017, https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/justice-department-secures-denaturalization-senior-jihadist-operative-who-was-convicted.

- “Denaturalization Lawsuit Filed Against Convicted Al Qaeda Conspirator Residing in Illinois,” Press Release, Department of Justice Office of Public Affairs, March 20, 2017, https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/denaturalization-lawsuit-filed-against-convicted-al-qaeda-conspirator-residing-illinois.

- Kavitha Surana, “Justice Department Moves to Revoke U.S Citizenship From Man Convicted in 2003 Terror Plot,” Foreign Policy, March 21, 2017, https://foreignpolicy.com/2017/03/21/justice-department-moves-to-revoke-u-s-citizenship-of-would-be-brooklyn-bridge-bomber-trump-attorney-general-jeff-sessions-iyman-faris-terrorism/.

- Kavitha Surana, “Justice Department Moves to Revoke U.S Citizenship From Man Convicted in 2003 Terror Plot,” Foreign Policy, March 21, 2017, https://foreignpolicy.com/2017/03/21/justice-department-moves-to-revoke-u-s-citizenship-of-would-be-brooklyn-bridge-bomber-trump-attorney-general-jeff-sessions-iyman-faris-terrorism/.</a

- Josh Gerstein, “Trump officials pushing to strip convicted terrorists of citizenship,” Politico, August 8, 2019, https://www.politico.com/story/2019/06/08/trump-convicted-terrorists-citizenship-1357278.

- Charlie Savage, “Trump Administration Asks Congress to Reauthorize N.S.A.’s Deactivated Call Records Program,” New York Times, August 15, 2019, https://www.nytimes.com/2019/08/15/us/politics/trump-nsa-call-records-program.html.

- Charlie Savage, “Trump Administration Asks Congress to Reauthorize N.S.A.’s Deactivated Call Records Program,” New York Times, August 15, 2019, https://www.nytimes.com/2019/08/15/us/politics/trump-nsa-call-records-program.html.

- Elhady v. Kable, Civil Action No. 1:16-cv-375 (AJT/JFA), 2019 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 152526 (E.D. Va. Sep. 4, 2019), https://int.nyt.com/data/documenthelper/1689-terror-watchlist-ruling/75cd50557652ad0bfa2a/optimized/full.pdf#page=1.

- Elhady v. Kable, Civil Action No. 1:16-cv-375 (AJT/JFA), 2019 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 152526 (E.D. Va. Sep. 4, 2019), https://int.nyt.com/data/documenthelper/1689-terror-watchlist-ruling/75cd50557652ad0bfa2a/optimized/full.pdf#page=1.

- Maryam Saleh, “Trump Administration Is Spending Enormous Resources to Strip Citizenship from a Florida Truck Driver,” The Intercept, April 4 2019, https://theintercept.com/2019/04/04/denaturalization-case-citizenship-parvez-khan/.

- Tara Copp, “Immigrant soldiers now denied US citizenship at higher rate than civilians,” McClatchy, May 15, 2019, https://www.mcclatchydc.com/latest-news/article230269884.html.

- Johnson v. Eisentrager, 339 U.S. 763 (1950), https://supreme.justia.com/cases/federal/us/339/763/.