The Sunni extremist group known as Islamic State (IS, also known by an earlier acronym, ISIS) is taking a terrible beating. In the past few days, it has lost territory in both Syria and Iraq. Syrian Kurds have attacked it east of Aleppo and north of Raqqa City, while it is battling Sunni Arab rivals north of Aleppo. The Syrian army of President Bashar al-Assad is pressing into the Raqqa Governorate and taking ground in the deserts east of Palmyra. In Iraq, other Kurdish groups have struck east of Mosul, while an alliance of Shia militias and the Iraqi army is moving into its stronghold in Fallujah. Further afield, the jihadis are being purged from the Libyan city of Sirte.

Islamic State’s self-styled caliph, Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, is nowhere to be seen or heard as his fighters face attacks on all fronts. According to the U.S.-led anti-Islamic State coalition, the jihadi group has now lost half of the area it controlled in Iraq at its peak in late 2014 and a fifth of its territory in Syria. Revenues from oil and other assets are reportedly down by a third and a U.S. government official recently claimed the coalition has “cut off entirely their revenue that’s coming from the outside.” The coalition also says that the total number of Islamic State fighters in Iraq and Syria has dropped from a peak of around 31,000 in December 2014 to between 19,000 and 25,000 today, and the influx of foreign jihadis has allegedly been reduced by three-quarters.

Islamic State has not scored a major victory on the battlefield in more than a year, and its ability to govern efficiently is withering. People with their ear to the ground in Islamic State’s Syrian stronghold of Raqqa speak of frail governance and worsening repression, since the group can no longer afford to buy civil peace. If popular discontent continues to grow, a weakening Islamic State could face internal dissent and tribal uprisings.

Still, the decline of Islamic State is certainly not irreversible and its enemies could be in for rough surprises ahead. In some areas, the forces confronting Islamic State are even more dysfunctional than the group itself, held together only by foreign influence and the fact that they face a common enemy. Now, with Islamic State’s influence finally receding, that brittle unity is being tested. Syria has long been torn asunder by civil war and regional rivalries, while Iraq suffers from a worsening political paralysis. Islamic State is weaker than at any point since it conquered Mosul two years ago, but thanks to the chronic disorder among its enemies, it may still be able to regroup and reclaim the initiative.

Downhill since Kobane

That Islamic State is in trouble should not come as news. The jihadi group has been on a downward slope for about a year and a half, ever since the protracted battle in the Syrian city of Kobane, which ended in spring 2015. Relentless jihadi attempts to dislodge Kobane’s Kurdish defenders were repelled with the help of American airstrikes, which according to U.S. officials left the jihadis with a death toll “in the four figures.” Once the Kurds had regained their footing and went on the offensive, Islamic State forces melted away—depleted, broken, and unable to stand up to the strikingly successful combination of Kurdish boots on the ground and U.S. airstrikes from above. Since then, the Kurds have steadily been eating into the northern flank of Islamic State, depriving it of key roads, oil wells, and border access.

But the group held its ground elsewhere, and even infiltrated into new regions. In May 2015, not long after losing Kobane, Islamic State briefly seemed to bounce back. It captured Ramadi, an important town on the Euphrates in Iraq, and Palmyra in the central Syrian deserts. These victories gave its fighters a much-needed morale boost, and Palmyra held important energy resources. The steady drumbeat of gruesome massacres and attacks outside the Middle East also helped maintain Islamic State’s image as a fearsome power to be reckoned with.

But on the ground in Iraq and Syria, the war did no go well. Not only has the group failed to make significant advances since summer 2015, it has also lost the big gains from that period. Ramadi fell to the Iraqi Army this February and Palmyra was retaken by Assad and his allies in March. Even before that, Islamic State was driven out of Tikrit and Baiji in Iraq, and it is now about to lose Fallujah.

“Losing territories in the countryside is not that important. This is a war after all,” says Wassim Nasr, a French reporter and expert on jihadi movements, who recently published a book on Islamic State. Once the jihadi group tried to join the ranks of nation-states, he explains in an interview, it faced new problems:

Losing the cities, however, is a problem for them. That is where the infrastructure is found. It is where you have the administration of services, and the control over the population. . . .

The international coalition is now treating them as the state they claim to be. It attacks their capacity to govern by striking bridges, roads, oil fields, and cities. Of course they can regroup in the desert and the countryside, but it would not be the same. Destroying their hold over the cities is a way of showing how weak they can get after more than two years of military pressure on multiple fronts. It means they cannot protect the population, pay salaries, or maintain public services. They risk losing the support from local tribes and others who joined them for opportunistic reasons.

So far, despite sporadic reports about internal executions and ideological dissent, there have been no signs of major unrest brewing in Islamic State–controlled territory. But the group is clearly weakened and seems increasingly vulnerable to internal challenges, should they appear.

In Their Own Words

Islamic State’s public statements are always bullish and aggressive, regularly promising the conquest of Rome, the end of the world, and other assorted treats. But read behind the lines and there is more than a hint of worry.

In fact, the group started making excuses for failure already a year ago. Last summer, Islamic State had just plucked Ramadi and Palmyra from their enemies, but this victory could not conceal the fact that hard times lay ahead.

On June 23, 2015, Islamic State spokesperson Abu Mohammed al-Adnani released a statement to mark the start of Ramadan, also heralding Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi’s first year as “caliph.” By Islamic State’s own bombastic standards, it was weirdly defensive. Instead of simply promising more and greater victories—though he did that, too—Adnani sought to stress that every setback is a gift from God and that ultimate victory is assured no matter how long it takes. Islamic State’s holy warriors “may lose a battle or battles; turns of misfortune might even overtake them and thus they lose cities and areas, but they are never defeated,” he intoned. They must continue to fight so that God will grant them “final victory if they fear Him and show patience.”

Though wrapped in thick folds of Islamic scripture and prophecy, Adnani’s speech was a transparent attempt at damage control—and since then, from Islamic State’s vantage point, things have only gotten worse.

On May 22 this year, Adnani again came forth with a statement, roughly timed to the second birthday of the caliphate (according to the Islamic calendar, which is based on the lunar year). In a voice recording full of the customary colorful denunciations—President Barack Obama was written off as a “failed, defeated mule”—Adnani called for attacks in the West, in the East, and everywhere else. But this time the rhetoric rang even more hollow. Instead of discussing the Syrian government offensive that had just snatched back Palmyra, the Islamic State’s painful loss of Ramadi to the Iraqi Army, or the looming offensive on Fallujah, he tried to ignore these mounting problems. And yet, a feeling of inevitable defeat echoed throughout the speech, as Adnani sought to put a brave face on a bad year by directly addressing his enemies:

Were we defeated when we lost the cities in Iraq [in the 2006–2010 period] and were in the desert without any city or land? And would we be defeated and you be victorious if you were to take Mosul or Sirte or Raqqah or even take all the cities and we were to return to our initial condition? Certainly not! True defeat is the loss of willpower and desire to fight.

Obviously, these are not the words of a winner. Rather, they sound like a pep talk for a losing team. In fact, Adnani is making a painful concession of weakness for a group that has always thrived on demonstrations of strength and which has sought to translate territorial control into religious legitimacy. By claiming the attributes of a caliphate in June 2014, the Islamic State sought to tap into the dream of religious restoration so widely—and in most cases legitimately—shared by Sunni Muslims everywhere. Even though only a thin sliver of extremists would agree that Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi’s warlord empire is a legitimate caliphate, that thin sliver was all he needed to attract thousands of fighters from abroad.

But this strategy has been a double-edged sword. Territory, once captured, can also be taken away. By accepting that Islamic State may eventually be forced back to “the desert without any city or land,” the group could be making a “huge strategic error,” in the view of senior French intelligence official cited by Le Figaro. Why? Well, “because it enshrines the idea that it has become impossible [for Islamic State] to install a caliphate on the ground.” And if the caliph doesn’t have a caliphate, then what sort of a caliph is he? How is he any different from the rest of the Middle East’s failed fundamentalist warlords, traversing little ruined towns and desert hideouts in battered Toyotas with machine-gun mounts and tattered black flags?

Finding Strength in the Weakness of Others

Then again, Adnani isn’t exactly wrong. As he says, Islamic State has been driven out of its cities once before only to rebound and grow even more powerful. Who’s to say he’s not being prescient, rather than engaging in bravado, when he predicts that his jihadist movement could sweep to power from exile in the desert once more?

In 2010, when Islamic State’s original leaders were killed, it held no territory and operated as an underground guerrilla movement. Only four years later, profiting from the partial state collapses in Iraq and Syria, the group was back in business. In January 2014, it conquered Fallujah and Raqqa, and in less than six months, it had marched into Mosul, Tikrit, Tal Afar, and many other areas of Syria and Iraq.

Adnani is in fact right when he tries to convince his supporters that Islamic State isn’t losing this war because it is too weak, too poorly organized, or lacking in determination. To the contrary, the group still controls large areas; it has never experienced a major split; and it fights ferociously. In a direct battle with equally matched forces, it would destroy most local opponents.

No, the real reason why Islamic State is losing is because it was reckless enough to pick a fight with the entire world. Whether it can muster 15,000 fighters or 50,000, there is simply no way the numbers will add up in its favor when pitted against this unholy alliance of Sunni and Shia Islamists, Baathists and anti-Baathists, al-Qaeda loyalists, Sunni Arab tribes, and Kurds in both Syria and Iraq, not to mention all the foreigners: Americans, Iranians, Russians, Arabs, Turks, Europeans, and so on.

As long as most of these governments and groups act in concert and keep hitting Islamic State, it will lose. But here’s the kicker: most of the time, they don’t.

As long as most of these governments and groups act in concert and keep hitting Islamic State, it will lose. But here’s the kicker: most of the time, they don’t. As soon as they drive the jihadi group back, the forces aligned against Islamic State tend to revert to their own deeply felt disputes. In the space created by the persistent rivalries of his enemies, Baghdadi’s men can hope to survive and gather strength for a comeback.

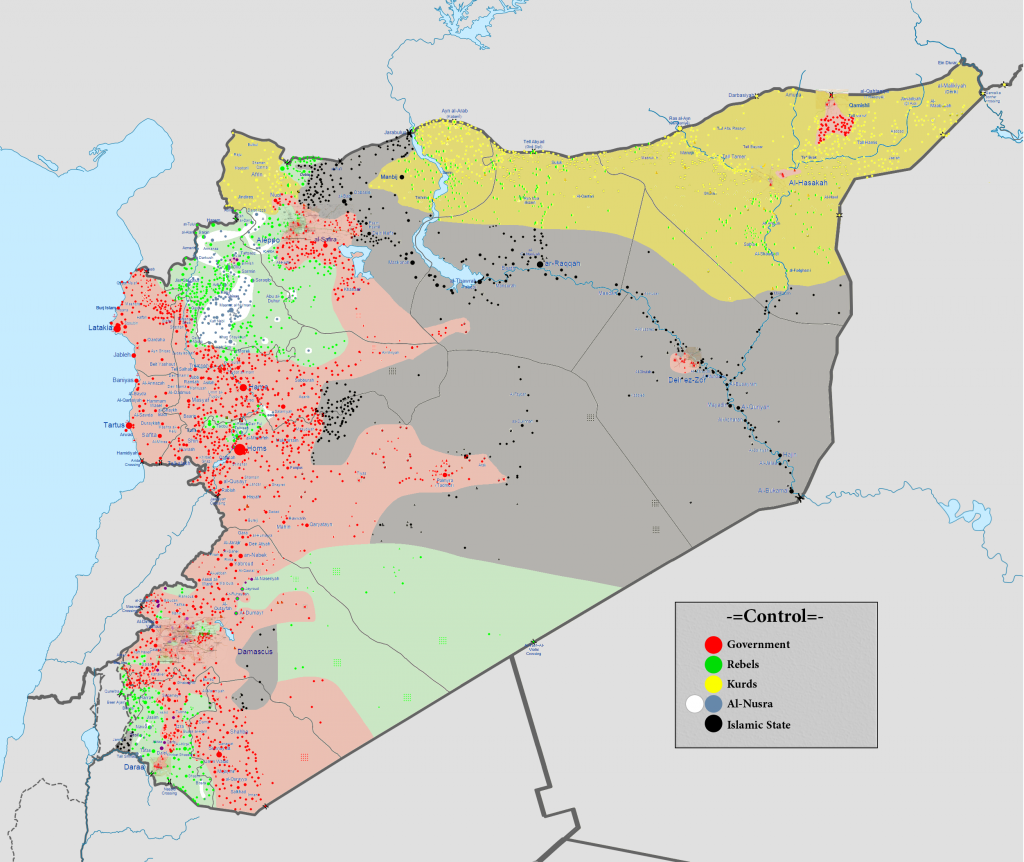

Living off of Syria’s Division

Syria, the scene of a five-year civil war, is now a divided country. Its most densely populated portion in the west is held by President Bashar al-Assad’s army, with the Syrian Democratic Forces—a Kurdish led group linked to the Kurdistan Workers’ Party, or PKK—ensconced along the northern border. Islamic State is in the east, while a great number of other Sunni Arab rebel groups control patches of territory in the north, south, and center. Some of the latter are linked to al-Qaeda, while others enjoy American, Saudi, Jordanian, Turkish or other foreign sponsorship.

It is important to realize that Islamic State is not a cause of Syria’s breakdown. Having found sanctuary there only after the civil war erupted in 2011, the current form of Islamic State is a byproduct of Syria’s collapse. It was in the lawless, sectarian, and violent environment created by the conflict between Assad and the Sunni rebels that Islamic State found fertile soil for its ideology and popular demand for its ruthless enforcement of order; only then did it begin to grow, cement control, and prey on lesser militias.

If united, Syrians would have no problem rooting out Islamic State from its territory, but united is exactly what the Syrian factions are not right now. Instead, they are significantly more focused on fighting each other than Islamic State. All of the main armed actors in Syria, except the Kurds, and all of their foreign patrons, except the United States, tend to view war on Islamic State as a sideshow to the real conflict, which revolves around the fate of Bashar al-Assad. They have concluded—and it is hard to fault their logic—that even though Islamic State is a serious threat, it is a threat that others will help them with in the future. That is why it makes more sense for each Syrian warlord to spend his own limited resources on enemies closer to home, and to gleefully step aside when Islamic State comes hunting for his rivals.

The most blatant example of how Islamic State has profited from Syria’s internal conflict is the area east and northeast of Aleppo, sometimes called the Manbij pocket. The Islamic State has controlled it since early 2014, profiting enormously from access to a 100 km stretch of the Turkish border—its sole remaining link to the outside world.

All sides seem to agree that Islamic State should be kicked out of this region, but all have been too busy fighting each other to attempt it; meanwhile, the group has expanded. Only now, in June 2016, is Manbij being attacked by the Syrian Democratic Forces from across the Euphrates. That has in turn freed up Sunni opposition groups north of Aleppo for a counterattack against Islamic State forces. Further south, Syrian government forces have taken the opportunity to press eastward from Ithriya toward the hydroelectrical dam and the military airfield at Tabqa, which would put it within striking range of Raqqa, as well as toward the desert roads connecting Palmyra, Raqqa, and Deir al-Zor.

On the fringes of all this, a Jordanian- and American-backed group of Sunni clansmen known as the New Syrian Army has been raiding isolated jihadi outposts in the deserts of southern and eastern Syria, interfering with Islamic State’s control over important smuggling routes for oil, refugees, and food.

When Islamic State is hit by all these actors at once, it loses terrain rapidly. But this Syrian synergy may soon expire, giving Islamic State another reprieve. For weeks, pro-Assad media has been dropping hints about a renewed push against by the Syrian army, Russia, and Iran to lay siege to Aleppo. There is already heavy bombing of the Castello Road, rebel-held Aleppo’s last lifeline. A permanent closing of the road would lead to a complete government encirclement of Aleppo, changing the map of northern Syria. For both Assad and the rebels, and for their respective backers, the struggle for Aleppo is immensely more important than whatever happens to Islamic State in the east.

The Syrian Democratic Forces’ expansion into the Manbij region is also being watched warily by Turkey, which is waging its own, brutal war against the PKK at home. Turkish officials say it would be “out of the question” to assist the U.S.-backed operation, even though American officials claim that 3,000 out of the 3,500 fighters taking part in the Manbij battle are local Arabs, not pro-PKK Kurds. The Turks seem unconvinced, since Kurdish leaders have said many times, and their official maps show, that they desperately want to punch through the areas north and northeast of Aleppo. That would connect the two main Kurdish regions, but it would also place the entirety of Turkey’s long Syrian border under the control of the PKK. It is a nightmare scenario for Ankara and it is uncertain how the Turks would respond.

It is unlikely that any sort of stable, capable, and locally legitimate government could be found for the Euphrates region where Islamic State operates.

In the longer term, even if Islamic State were to lose its hold on the cities of eastern Syria—indeed, even if other parties were to make peace—the country will remain highly vulnerable to jihadi infiltration. It is unlikely that any sort of stable, capable, and locally legitimate government could be found for the Euphrates region where Islamic State operates. These areas were poor, tribal, and conservative long before 2011. They have now been thoroughly brutalized and further impoverished, and are awash in military hardware and radical Salafism. Even the best-case scenarios for a post-Islamic State order in eastern Syria look pretty bad.

Iraq’s Militia Problem

The internal problems of Iraq get less attention than those in Syria, but that does not mean they are any less severe. In fact, it is in Iraq that the coalition against Islamic State could really run aground, if it does not manage to defuse a series of looming political crises.

The most obvious problem on the Iraqi front is the way sectarian dynamics have long driven Sunnis Arabs into the arms of Islamic State. Radical Shia militias make up a significant part of the Iraqi armed forces and indeed of the Baghdad government itself. Operating as part of the militia coalition known as al-Hashd al-Shaabi, or the Popular Mobilization Forces, many of these groups are backed to the hilt by Iran and overseen by Iranian advisers. The Iraqi government has no objection. To the contrary, Foreign Minister Ibrahim al-Jaafari recently dismissed criticism against the Hashd as being based on “illusions” and defended it as an exemplary force in the war against terrorism.

Troublingly, some of these groups have a long history of sectarian violence against Sunnis, and in the current offensive on Fallujah they have served as Islamic State’s best propaganda tool. Many Sunni Muslims in Fallujah seem to fear the Shia militias more than they oppose Islamic State, perhaps for good reason. The United Nations has warned of credible reports of abuse by the militias against civilians surrendering and fleeing from Fallujah, and while Hashd representatives deny these reports, the Iraqi government says it has arrested militia fighters on suspicion of participation in a massacre.

Strengthening the official military and political institutions in Iraq could help offset these problems, by diminishing the role of the most sectarian militias and giving Iraq’s religious and ethnic minorities something to cling to in an order dominated by Shia Arab groups. This goal is easier set than met, however. The United States has spent more than $1.6 billion in the past two years on trying to get the Iraqi Army into shape, but its efforts have met with little success. The army still struggles to regain its balance after its 2014 collapse and is plagued by accusations of corruption and human rights abuses. Entire divisions are under the sway of Iran-friendly Shia Islamists who funnel money, guns, ammunition, and even tanks to the militias. Salaries and conditions for soldiers are poor—worse than for many Hashd fighters—and the army cannot find enough capable recruits. Only a few heavily resourced and well-trained special forces units seem able to spearhead operations against Islamic State effectively, but after years of war they risk being exhausted.

…Serious reform to the Iraqi security sector would first require reforming the political system.

In fact, since 2014 it is the militias that have exerted influence on Baghdad, rather than the other way around. Their political wings have successfully lobbied against legislation that could have empowered state institutions or helped to heal the rift with Iraq’s Sunni minority. For this reason and many others, including its corruption and general malfunctions, serious reform to the Iraqi security sector would first require reforming the political system.

At the moment, such reform seems more elusive than ever. Since 2014, the price of oil has sunk, punching an ugly hole in Baghdad’s finances—which are 95 percent oil-dependent—and hardening tensions between politicians who compete for the same resources. Progress in the battle against Islamic State has also, somewhat ironically, meant that there is less pressure to stick together. “For Baghdad’s Shia parties and paramilitary groups, and for Erbil, the external Islamic State threat initially served as a unifying force,” says Renad Mansour, an Iraq specialist at the Carnegie Middle East Center in Beirut, in an e-mail. “In the past little while, however, protest movements—Kurds against their Kurdish leaders and Shia against their Shia leaders—have disrupted the sense of identity-based unity.”

In other words, just as the Islamic State threat recedes, Iraqi leaders risk dropping the ball again.

Intra-Shia Tensions in Baghdad

After the loss of Mosul in June 2014, many Iraqis blamed Iraqi Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki—a close Iranian ally from a Shia Islamist party—for needlessly alienating Iraqi Sunni Muslims and paving the way for Islamic State’s return. Encouraged by the United States, Iraqi actors joined forces to remove Maliki and replace him with a less toxic member of the same party, Haidar al-Abadi. Maliki resisted, but became so isolated that Iran seems to have withdrawn its support and endorsed Abadi’s candidacy. Maliki was finally forced out of office in August 2014.

Since then, Maliki has sought to undermine Abadi, by using his lingering influence over the state and by taking up the cause of the pro-Iranian militias. Abadi has in turn used his powers to weed out Maliki supporters, while struggling to find a majority in parliament to back his premiership. Their rivalry ties into American-Iranian tensions and has made an already hard-to-govern Iraq even more dysfunctional. The latest round played out early this month, when Abadi fired a group of Maliki appointees holding senior posts in the intelligence apparatus, the banking sector, and the media.

Brandeis University scholar Harith al-Qarawee concludes in an excellent new study of Abadi’s leadership that the problems of Iraq are systemic. The country is so fractured that it needs a clear center of gravity for reforms to happen, but the moment a strong leader emerges, former allies will gang up on him to protect their sectoral privileges. Broken and corrupt institutions have thus thwarted Abadi’s ambitions to impose order through the cabinet, while obstruction by Maliki, the militias, and to some extent Iran have stripped the prime minister of influence within the Shia camp, which inevitably remains the base of the Baghdad regime. It has made him something of a lame duck leader. As Qarawee puts it:

A Shia prime minister like Abadi needs to command a broad constituency that is loyal to and supportive of him in order to make the concessions and compromises that a new political compact would require. Abadi, although armed with good intentions and the desire to make a difference, lacks such a constituency and, as a result, has not been able to make those changes.

The Parliamentary Crisis

As Iraq’s war against Islamic State dragged on and the effects of the oil price crunch began to be felt, popular support for Abadi’s ineffectual government slowly evaporated. In an attempt to break the deadlock, the frustrated prime minister sought to change the cabinet without parliamentary approval, first in August 2015, and again, in a more radical bid to create a “technocratic” government, in February this year. Abadi’s gambit sparked immediate pushback from parliament, far beyond the Maliki camp. But it also invited new competition, when the Islamist preacher Moqtada al-Sadr suddenly burst onto the scene as a third-party contender, though ostensibly in support of Abadi’s reform bid. Sadr is perhaps not much fond of Abadi, but he loathes Maliki and he is more autonomous of Iran than most of the armed Shia Islamists, though certainly no friend of the United States. To show off his power on the streets of Baghdad and force concessions in parliament, Sadr began to organize enormous demonstrations and threatened to invade the parliament building in the capital’s Green Zone.

On April 30, two days after yet another deadlocked parliamentary vote, Sadr made good on his threats by ordering a riotous invasion of the parliamentary building, sending politicians fleeing and causing a reported $5 million of damage. Since then, the parliament has been out of session and Iraqi politics are in severe crisis. With no solution to expect from constitutional politics, attention is turning to the street and to the gun, with scuffles between Sadr’s followers and the pro-Iranian militias reported last week in southern Iraq. If these problems were to develop into more serious strife, it could further disrupt institutional governance and would force militia groups to pull forces from the frontline, giving the Islamic State a chance to expand again.

If these problems were to develop into more serious strife, it could further disrupt institutional governance and would force militia groups to pull forces from the frontline, giving the Islamic State a chance to expand again.

Still, Carnegie’s Renad Mansour cautions that an “intra-Shia war is unlikely for as long as the Islamic State remains a serious threat.” From that point of view, Islamic State’s current strategy may be self-defeating. Sensing a second chance at breaking Baghdad, the jihadi group has been feeding the chaos for all it’s worth by sending suicide squads and car bombs into Shia neighborhoods. While the violence has undoubtedly added to the anger and frustration among Iraqi Shia constituencies, Islamic State’s continued wanton slaughter of non-Sunnis may also paradoxically help the Shia parties and militias maintain their focus on the common enemy.

The Constitutional Vacuum in Iraqi Kurdistan

The problems in northern Iraq are no less severe. The autonomous Kurdistan Regional Government has seen its economy gutted by low oil prices, and made worse by persistent feuds with the central government over who has the right to sell oil. As salaries go unpaid and officials unbribed, discontent is rising. In addition, large numbers of Iraqis and Syrian Kurds have sought safety in Iraqi Kurdistan, causing an increase in social tension and straining the economy.

To make matters worse, in what must be the one of the world’s worst-timed constitutional crises, Kurdish politics have become paralyzed over the issue of Regional President Massoud Barzani’s mandate.

The Kurdistan Regional Government is governed by a patchwork of formal and informal agreements between the area’s main political parties, the Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP) and the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (PUK), which have carved up the area and its resources between themselves since their 1994–1997 civil war. Not unlike in Lebanon, political offices have been distributed through a combination of informal quotas, semi-free elections, patronage politics, and foreign influence. A number of opposition groups operate in Iraqi Kurdistan, such as the Gorran Party, a large PUK splinter faction based in Suleimaniya, and two smaller Islamist movements. Adding to the current uncertainty is the fact that the PUK is more or less leaderless since its founder and president Jalal Talabani suffered a debilitating stroke in 2012, and has trouble holding its leadership together. Gorran’s leader, Nawshirwan Mustafa, is also old and ailing.

The Kurdish parties often seek support from external forces to improve their own position. The PUK and KDP both work closely with the United States. The KDP also maintains strong relations with Turkey, while the PUK and Gorran are close to Iran. In recent years, the PUK has also developed a strong working relationship with the PKK and its various Syrian and Iraqi affiliates, which are also found in the Iran-friendly camp and seem to be a rising force in northern Iraq. This is unnerving for both Turkey and the KDP. Barzani has sought to sanction the PKK-friendly Syrian Kurds by repeatedly closing the Syrian-Iraqi border, but this earns him no friends in Kurdistan.

As head of the KDP, which is the strongest party and controls the regional capital Erbil, Massoud Barzani has been president of the Kurdistan Regional Government ever since the KDP and PUK decided to merge their enclaves in 2005. According to the constitution, his term expired in August 2015, but Barzani has simply refused to step down. The PUK, Gorran, and the rest of the opposition are understandably furious. While violence has mostly been avoided—some demonstrators have been shot and Gorran supporters have torched KDP offices in Suleimaniya—there is a growing political vacuum. Barzani’s security forces have unilaterally ejected Gorran officials from the institutions in KDP-controlled Erbil. The other parties protest, and only the KDP now recognizes Barzani as the legitimate KRG president. The regional parliament has gone into recess and an exasperated lawmaker from an Islamist opposition party says he believes legislators might not convene again until the next scheduled elections in autumn 2017. (Not an attractive option for anyone, including Barzani; the PUK is likely to gain in those elections.)

Barzani has tried to shore up his popularity by resuming old calls for a referendum on Kurdish independence. It is not quite clear how any ballot is supposed to happen without a working parliament, but independence is a popular demand in the KRG and Barzani’s maneuver hasn’t failed to wrong-foot the opposition. Outside of Kurdistan, it’s another story; the non-Kurdish majority is overwhelmingly opposed to Kurdish separatism. Tensions run high in the disputed border regions, where both Sunni and Shia Arabs resent the military dominance and territorial demands of the Kurds. The referendum drive has therefore set off alarm bells in Baghdad, Ankara, Tehran, Washington, and a number of other capitals, all of whose diplomats are discreetly trying to get the Kurds to shut up about independence, put their house in order, and focus on the war against Islamic State.

That’s easier said than done, given the near-total mismatch between the priorities of Kurds in the north, the Arab majority in the rest of the Iraq, and the international powers involved in the war. The Kurds have already conquered most of the territory they sought in northern Iraq, including the oil-rich Kirkuk region. As long as they can hold Islamic State at bay, then from the perspective of the KDP in Erbil and the PUK in Suleimaniya, now may in fact be the perfect time for a return to familiar rivalries.

Victory Even in Defeat?

On paper, Islamic State is up against an overwhelmingly strong coalition of forces. But clearly, it is not much of a coalition at all—or rather, it is several coalitions, often working at cross-purposes. Every faction seems to be waging its own separate war on Islamic State: across civil-war-Syria, but also in Baghdad, Erbil, and a number of Middle Eastern capitals, and mirrored in the Saudi-Iranian, Turkish-PKK, and American-Russian rivalries. External intervention continues to aggravate the internal problems of Syria and Iraq, while bloodshed and sectarian polarization ensure that there will be at least some popular demand for Islamic State ideology among Arab Sunnis for years or decades to come.

This scenery of chronic infighting and chaos is what allows Abu Mohammed al-Adnani to claim with his typical confidence that even if Islamic State loses everything, all would not be lost. There will remain a vast, under-governed space of shattered, brutalized, Sunni Arab regions, smarting from sectarian discrimination, violence, and poverty. The average fighter in the ranks of Islamic State today was a small child when the United States invaded Iraq in 2003 and he has no memory of a life without Sunni-Shia warfare, no reason to truly believe in sectarian coexistence. Soon, the same situation will apply in Syria.

Meanwhile, there is a growing risk that internal problems, whether political or socioeconomic, will disrupt Iraqi and Kurdish contributions to the struggle against Islamic State. In Syria, the viability of the Damascus government and the main Sunni rivals of Islamic State continue to hang in doubt, as each seeks to strangle the other.

Even if Islamic State does eventually lose Raqqa, Mosul, and the other areas under its control, there is little hope for the sort of reconciliation and rebuilding that could permanently drain the swamp of sectarian hatred and militia rule into which both Iraq and Syria are sinking. And though Islamic State may at this point have gone too far down the road of apocalyptic extremism to be able to handle defeat, some of its factions could survive to fight another day, rescued by the weakness and venality of the forces arrayed against them. Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi is not likely to have the last laugh, but he might have the one after that.

Cover Photo Credit: Chaoyue 超越 PAN 潘, Return to Homs. June 3, 2014.