Introduction

The debate over affirmative action policies in higher education—which has spanned nearly five decades—has shifted in recent years. Today, the discussion is not so much about whether having racially and ethnically diverse college campuses is desirable, but rather about how best to achieve that worthy objective.

Most universities prefer employing explicit racial preferences that allow them to recruit and admit the highest-scoring black and Hispanic students—who tend to be fairly well off economically, just like the white and Asian students found on campus. Under the current admissions system, which heavily weights the race of students but not their socioeconomic disadvantage, students from the richest quarter of the population outnumber students from the most disadvantaged quarter by fourteen to one at selective colleges and universities.1

The U.S. Supreme Court, however, is pushing universities to pursue alternative means to achieve diversity—such as giving a preference to economically disadvantaged students of all races, or admitting the top proportion of students from all high schools in a state. As this report will demonstrate, these alternative strategies can produce substantial racial and ethnic diversity and also make higher education more economically inclusive.

College leaders, however, almost universally oppose alternative methods for pursuing diversity because they involve more work and greater resources. It simply is easier and cheaper to enroll the most-privileged students of any race than to open the doors to high-achieving low-income and working-class students. The higher education establishment has joined with business leaders and civil rights groups to flood the Supreme Court in the latest challenge to racial preferences with almost 70 amicus briefs defending the status quo, as opposed to 14 calling for change.2

But in Fisher v. University of Texas II, which the Supreme Court takes up on December 9, a majority of justices are likely to accelerate the trend toward requiring universities that seek racial diversity to employ new strategies that do not automatically favor or disfavor students based on which racial box they check. What will these new forms of affirmative action look like? What will be their effect on racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic diversity? And what sort of new political alliances could they help forge?

This report proceeds in four parts. Part I explains why racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic inclusion are essential goals for selective colleges and universities. Part II outlines why current practices—which heavily consider race and mostly ignore socioeconomic disadvantage—are legally vulnerable. Part III examines in detail the empirical evidence on the pivotal question in the Fisher II case: Do race-neutral strategies for producing diversity work? Part IV looks to what’s next for affirmative action—outlining innovative new paths to diversity and the exciting new political environment that could flow from updated forms of affirmative action.

Why Racial, Ethnic, and Socioeconomic Diversity Matter at Selective Colleges

As the U.S. student population experiences dramatic demographic changes—and as our society’s income inequality continues to rise—promoting racial, ethnic, and economic inclusion at selective colleges has become more important than ever. To be economically competitive and socially just, America needs to draw upon the talents of students from all backgrounds.

As a moral matter, colleges need to be cognizant of racial and economic inequality in American society. Race continues to shape not only our collective politics, but also alters the level of access to many opportunities for people of color. Despite progress, we still live in a nation plagued with racial inequity, haunted by the vestiges of legal, race-based oppression. The pursuit of equity for people of color remains necessary if we are to achieve the fair America that politicians promise. Yet racial justice must work hand in hand with class-based justice. Much of Jim Crow’s legacy remains intact through race-neutral laws that disadvantage all poor and working-class people. Redlining and housing covenants that barred blacks and Latinos from entire neighborhoods have morphed into toxic—but racially neutral—exclusionary zoning policies; de jure school segregation gave way to de facto segregation by both race and socioeconomic status; open racial employment discrimination now rears its head in many anti-unionization laws and massive wage gaps between employers and workers.

As a legal matter, the Supreme Court has long recognized that diversity in all of its forms—including racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic—is valuable for two reasons: (1) to improve the education of students, and (2) to demonstrate that pathways to leadership are open to all in a democratic society.

The Court has observed in Grutter v. Bollinger (2003) that “the nation’s future depends upon leaders trained through wide exposure to the ideas and mores of students as diverse as this Nation of many peoples.”3 The Court has also noted that “‘classroom discussion is livelier, more spirited and simply more enlightened and interesting’ when the students have ‘the greatest possible variety of backgrounds.’”4

The Court also has recognized a second interest: “In order to cultivate a set of leaders with legitimacy in the eyes of the citizenry, it is necessary that the path to leadership be visibly open to talented and qualified individuals of every race and ethnicity.” Speaking more expansively, the Court continued, “All members of our heterogeneous society must have confidence in the openness and integrity of the educational institutions that provide this training.”5

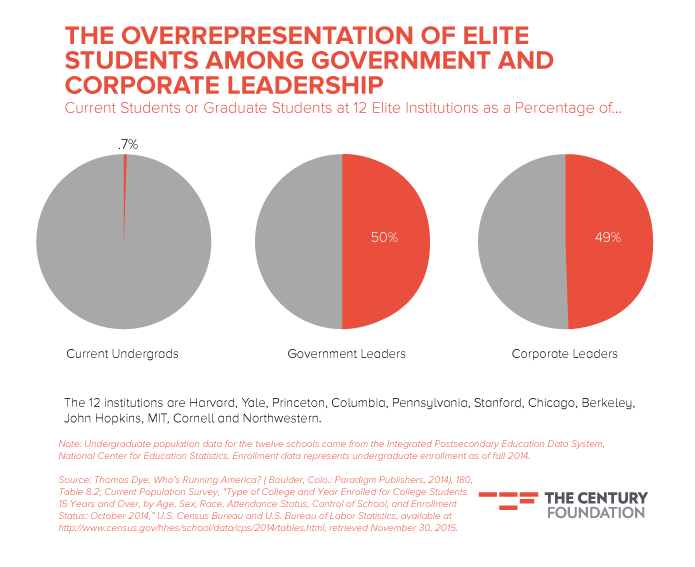

There is strong empirical support for the Supreme Court’s belief that selective colleges and universities produce a disproportionate number of American leaders. According to research by political scientist Thomas Dye, 50 percent of America’s top government leaders and 49 percent of top corporate leaders are graduates of just twelve wealthy colleges and universities (see Figure 1).6

Figure 1.

Likewise, there is good evidence that racial and ethnic diversity enhance learning. As Nancy Cantor, the president of Rutgers–Newark, and her colleague Peter Englot note, when students bring differing life experiences to discussions, they “strongly enrich the quality, creativity, and complexity of group thinking and problem-solving” that occurs. Research finds that groups including individuals with different perspectives outperform groups of individual high performers in problem solving “because the diverse groups increase the number of approaches to finding solutions to thorny problems.” More broadly, “learning how to work and learn and live across difference,” they argue, is “a prerequisite to a vibrant democracy.”7

Socioeconomic diversity also matters for the same set of reasons. If one is looking for a lively discussion from students with “the greatest possible variety of backgrounds,” then including a poor white student from a trailer park is at least as important as a wealthy graduate of a prep school who is African American. As one University of Pennsylvania law professor noted, his racially diverse class had “very few students who come from . . . the blue-collar working class. What that means is that no one has any idea what life is like on the other side of the tracks. That leads to a very sterile discussion when it comes to labor law.”8

Likewise, socioeconomic diversity is highly relevant to promoting the second interest the Court has identified: “All members of our heterogeneous society must have confidence in the openness” of institutions that train our nation’s leaders. A racially diverse class that effectively excludes students from families in the bottom half of the socioeconomic spectrum is unlikely to instill “legitimacy in the eyes of the citizenry.”

Current Practices for Achieving Diversity Are Legally Vulnerable

While the U.S. Supreme Court has properly endorsed the goals of racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic diversity in higher education, it has set major restrictions on how universities may pursue diversity—issues that are likely to come to a head in Fisher II.

First, the Court has long recognized that diversity should not be viewed simply as a matter of race and ethnicity. In Grutter, the Court pointed out that Justice Lewis F. Powell’s opinion in Regents of the University of California v. Bakke (1978) was “careful to emphasize that in his view race ‘is only one element in a range of factors a university properly may consider in attaining the goal of a heterogeneous student body.’”9

Second, the Court requires that universities try to find alternative ways to produce racial diversity, short of outright racial preferences, wherever possible. In Fisher v. University of Texas I (2013), the Court held that in pursuing the compelling goal of diversity, universities bear “the ultimate burden of demonstrating, before turning to racial classifications, that available workable race-neutral alternatives do not suffice.”10

While racial preferences are the most direct way to achieve racial diversity, workable alternatives are nevertheless preferred, the Court has said. In the Bakke decision, Justice Powell explained that there are costs to using race in decision-making—even for the compelling purpose of promote diversity—so it should only be used when “necessary.” For one thing, he noted, “preferential programs may only reinforce common stereotypes holding that certain groups are unable to achieve success without special protection.” For another, he observed that preferential treatment by race “well may serve to exacerbate racial and ethnic antagonisms rather than alleviate them.”11

Explicit racial preferences can be demeaning to the dignity of the recipient, as even supporters of affirmative action note. Anna Holmes, an accomplished writer who is African American, wrote in 2015, “When I was starting out in magazines, I was told by a colleague that my hiring was part of the company’s diversity push, and that my boss had received a significant bonus as a result of recruiting me. Whether or not it was true, it colored the next few years I spent there, making me wonder whether I was simply some sort of symbol to make the higher-ups feel better about themselves.”12

For all these reasons, the Supreme Court has long held that if there are workable alternatives that accomplish the compelling goal of racial diversity in higher education without making race an explicit factor, indirect strategies are required.

An Imbalance in Attention to Race and Class Raises Legal Concerns

Despite the clear instructions of the Court, current admissions policies at most selective colleges and universities appear still to violate the requirement that race only be used as a last resort. Likewise—rhetoric to the contrary—these institutions focus almost exclusively on what Georgetown law professor Sheryll Cashin calls a superficial “diversity by phenotype” to the exclusion of a richer and more nuanced emphasis on socioeconomic alongside racial diversity.13

Universities have long claimed that they “give significant favorable consideration” to economically disadvantaged students in pursuit of socioeconomic alongside racial and ethnic diversity.14 But careful empirical research—from four sets of supporters of racial affirmative action—suggest that universities do not in fact do so, at least so long as direct racial preferences are available to them.

- In a 2004 study of the nation’s most selective 146 institutions, Georgetown researchers Anthony Carnevale and Stephen Rose found that race-based affirmative action triples the representation of blacks and Hispanics students compared to admission based on grades and test scores, but that universities do nothing to boost socioeconomic representation per se.15 In fact, the representation of poor and working class students is slightly lower than if grades and test scores were the sole basis for admissions, the researchers found.16

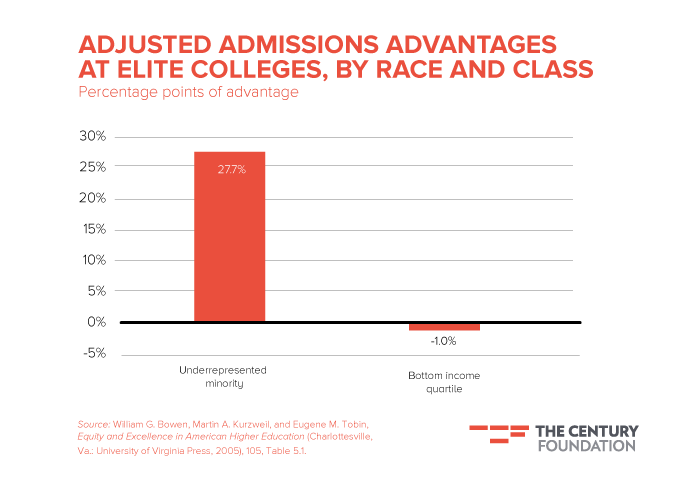

- In a 2005 study of highly selective institutions, the Mellon Foundation’s William Bowen and colleagues found that being an underrepresented minority increases one’s chance of admissions by 27.7 percentage points; that is, an applicant with a 40 percent chance of admissions has a 68 percent chance if she is black, Latino, or Native American. By contrast, being in the bottom income quartile (relative to the middle quartiles) has no positive effect.17 (See Figure 2.)

Figure 2.

- A 2009 analysis by Thomas Espenshade of Princeton and Alexandria Radford finds that, at highly selective private institutions, the boost provided to African American applicants is worth 310 SAT points (on a 1600 scale), compared with 130 points for poor students, 70 points for working-class applicants, and (distressingly) 50 points for upper-middle-class students, relative to middle-class pupils.18 Low-income white students, meanwhile, are penalized in their chances of admissions compared with more-affluent white students, holding all other factors constant.19

- A 2015 study by Sean Reardon of Stanford and colleagues using 2004 data concludes that “racial affirmative action plays (or played, in 2004) some role in admissions to highly selective colleges but SES-based affirmative action did not.”20

A similar pattern can be found among law schools. A 2011 study found that while law schools provide very large preferences to black and Latino students, there is no preference provided to students whose parents have lower levels of education. At the top twenty law schools, 89 percent of African Americans and 63 percent of Latinos (and even higher proportions of whites and Asians) come from the top socioeconomic half of the population. Just 2 percent of students at the top twenty law schools come from the bottom socioeconomic quarter of the population. As UCLA law professor Richard Sander points out, “low-SES representation at elite law schools is comparable to racial representation 50 years ago, before the civil rights revolution.”21

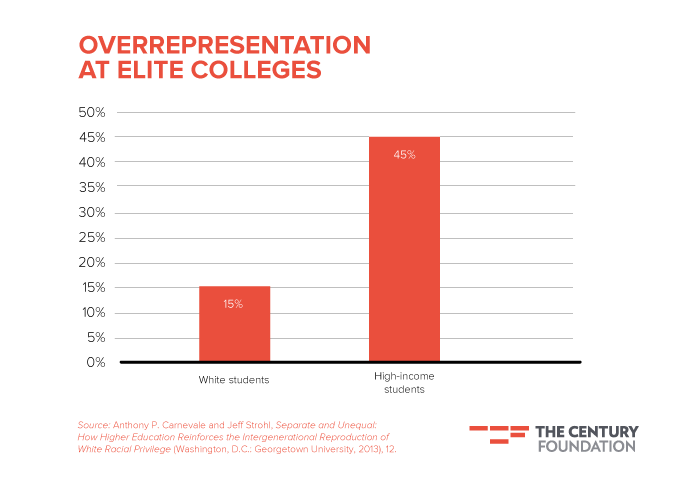

Overall, stratification by class is far greater than stratification by race on selective campuses. In a 2013 report, Anthony Carnevale and Jeff Strohl noted that white students are overrepresented at selective colleges by 15 percentage points, while African-American and Hispanic students are underrepresented by 9 percentage points. This racial gap is cause for serious concern—but the socioeconomic gap is three times larger. High-income students are overrepresented by an astounding 45 percentage points, and low-income students are underrepresented by 20 percentage points.22 (See Figure 3.)

Figure 3.

In sum, the heavy emphasis placed by higher education institutions on racial diversity, and the lack of attention for socioeconomic diversity, appears to contravene both the legal requirement that in pursuing racial diversity colleges should seek also other types of diversity, and the requirement that colleges pursue race-neutral strategies before resorting to race in admissions.

While higher education institutions have in the past decade announced a flurry of financial aid initiatives, a 2011 analysis by the Chronicle of Higher Education found that the percentage of students receiving Pell grants at the wealthiest fifty institutions remained flat between 2004–05 and 2008–09.25 In 2013, Catharine Hill reported that “only 10 percent of students attending selective colleges and universities came from the bottom 40 percent of the income distribution in 2001, and that little progress had been made by 2008, except at a few of the very wealthiest institutions.”26 A 2015 report by the University of Michigan’s Michael Bastedo observes that the proportion of low-income students at selective colleges has for decades remained virtually unchanged.27Research also finds that selective colleges have a lack of socioeconomic diversity across racial groups. According to William G. Bowen and Derek Bok’s The Shape of the River, 86 percent of African American students at selective colleges are middle- or upper-class—and the whites are even wealthier.23 Another study finds that the proportion of black students at elite colleges coming from the top quartile of the socioeconomic distribution increased from 29 percent in 1972 to 67 percent in 1992.24

Issues Coming to a Head in Fisher II

These vulnerabilities will be front and center in the Fisher II litigation. In the original Fisher I case, Abigail Fisher, a white student, challenged the constitutionality of the use of racial preferences in admissions at the University of Texas at Austin (UT). Fisher noted, correctly, that the UT plan to admit students in the top 10 percent of every high school produced greater racial diversity than UT’s use of racial preferences had in the past.

Many expected the Supreme Court to strike down Texas’s use of race in Fisher I, and, according to journalist Joan Biskupic’s 2014 biography, Breaking In: The Rise of Sonia Sotomayor and the Politics of Justice, a majority of the Supreme Court was prepared to do just that. But then, according to Biskupic, Justice Stephen Breyer intervened and told the swing vote, Justice Anthony Kennedy, that Justice Sotomayor was preparing a scathing dissent that would create serious racial division within the Court and the country as a whole. Kennedy backed off and issued a compromise 7–1 decision, which Sotomayor and Breyer joined, along with four conservative justices. Conservatives got a tough new standard—that universities bear “the ultimate burden of demonstrating, before turning to racial classifications, that available workable race-neutral alternatives do not suffice.”28 And liberals got an agreement to send the decision back to the Fifth Circuit for application of the new standard, which took the sting out of the decision and raised the possibility that the case would never come back.29

Then three things happened. First, in a separate 2014 affirmative action case involving the University of Michigan, the Supreme Court upheld Michigan’s voter-enacted ban on racial preferences. Justice Sotomayor wrote a blistering dissent, which, according to Biskupic, drew upon the draft dissent she has prepared in Fisher I. Second, on remand, the Fifth Circuit issued a decision in Fisher that supported racial preferences at UT, even under the new tougher standard Kennedy handed down. Third, universities appeared to greet the decision with a yawn.

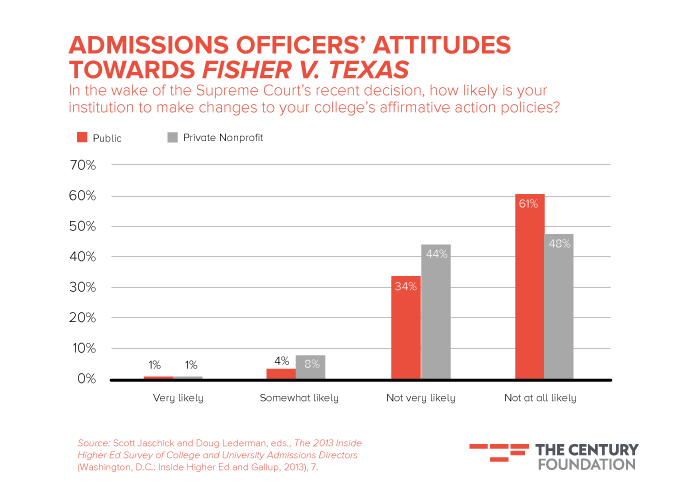

A 2013 Inside Higher Ed poll of admissions officers, for example, found that only 1 percent of public and private institutions were “very likely” to change policies after Fisher. Only 4 percent of public and 8 percent of private institutions were “somewhat likely” to change.30 (See Figure 4). Likewise, a 2015 report of the American Council on Education found that in a survey of college officials, “when asked directly whether the Fisher ruling affected their admissions or enrollment management practices, only 13 percent of institutions responded in the affirmative.”31

Figure 4.

It is not hard to understand why universities, when given the option of using racial preferences to recruit upper-middle-class minority students, do that instead of using race-neutral alternatives that involve recruiting economically disadvantaged students of all races. First, a lack of racial diversity is more visible to the naked eye than a lack of socioeconomic diversity and as such draws more attention. Second, it is may be easier for minority groups to politically organize around racial and ethnic identities than economically disadvantaged families to do so around economic status when seeking representation.

Most importantly, universities compete on prestige, and pursuing socioeconomic diversity as a race-neutral strategy takes resources away from spending that will increase an institution’s rankings in guides put out by organizations such as U.S. News & World Report. “Think about the incentives,” says Vassar President Catharine Hill. “Every dollar you use for financial aid could have been used otherwise to improve your ranking. Spending on every other thing ups your score.”32 Compared to the hard work of addressing deeply rooted inequalities, racial preferences provide what Yale law professor Stephen Carter has called “racial justice on the cheap.”33

Increasing the concern of affirmative action supporters was another development—the Supreme Court’s decision to take the Fisher II case on appeal from the Fifth Circuit. True, the past four times challenges to racial preferences have made it to the Supreme Court—the 1971 DeFunis case, the 1978 Bakke case, the 2003 Grutter case, and the 2013 Fisher I case—the preferences have survived. But this time may be different. As University of Colorado Law School professor Melissa Hart notes, the Supreme Court under Chief Justice John Roberts has long practiced what has been called “incrementalism”—an initial decision that moves the law slightly in a conservative direction, followed by a second more emphatic case. That has happened with voting rights, and campaign finance, and may well happen with affirmative action.34 Longtime Supreme Court watcher Linda Greenhouse of the New York Times has also speculated that Fisher I was an effort to move the law marginally, before the Court returned to the issue with a more emphatic statement.35

Evidence on Whether Race-Neutral Strategies Work

The pivotal question in Fisher II will be whether Texas found a viable race-neutral alternative, rendering its racial preference plan unconstitutional. For years, supporters of affirmative action argued that no workable alternatives existed for creating racial diversity. In the words of Justice Harry Blackmun’s opinion in the 1978 Bakke case: “I suspect that it would be impossible to arrange an affirmative action program in a racially neutral way and have it successful. To ask that this be so is to demand the impossible. In order to get beyond racism, we must first take account of race. There is no other way.”36

Since then, however, numerous universities have in fact found other ways. Several states—educating 29 percent of the national high school population—have banned racial affirmative action at their public universities and have devised creative new approaches to achieving diversity.37 These alternatives—which include providing affirmative action for economically disadvantaged students, increasing financial aid, admitting students in the top of all high school classes regardless of SAT or ACT scores, eliminating legacy preferences, boosting community colleges transfers, and increasing recruitment and K–12 pipeline partnerships—have produced substantial racial and ethnic diversity. (More details about these programs are provided in Part IV of this report, describing the future of affirmative action.)

Experiences in States Where Racial Preferences Have Been Banned

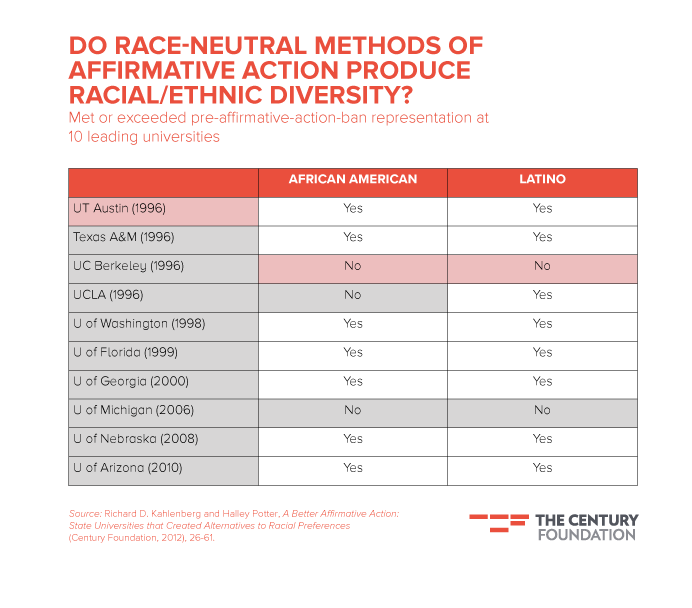

In 2012, my colleague Halley Potter and I examined ten leading universities where race had been banned and found that most succeeded.38

Colleges That Use Race-Neutral Methods to Meet or Exceed Racial Diversity Levels Achieved in the Past Using Racial Preferences

Of the ten schools examined, seven—UT Austin, Texas A&M, the University of Washington, the University of Florida, the University of Georgia, the University of Nebraska, and the University of Arizona—used race-neutral alternatives to match or exceed the levels of both African American and Hispanic representation those universities had achieved, before prohibitions went into effect, with race-conscious admissions.39 (See Figure 5).

Figure 5.

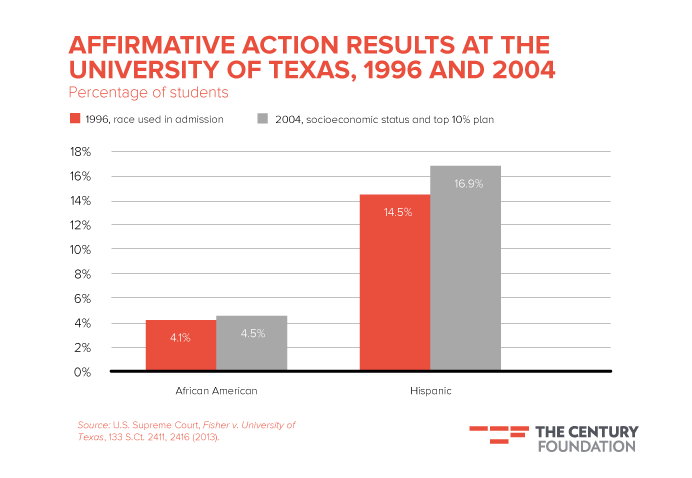

University of Texas. In 1996, the Fifth Circuit struck down racial preferences at UT–Austin in the case of Hopwood v. Texas. In response, the Texas legislature passed the Top 10 Percent Plan, providing automatic admission for the top 10 percent of student by grade point average in every high school. The plan, combined with socioeconomic affirmative action, produced as much—indeed slightly more—racial diversity in 2004 (4.5 percent African American and 16.9 percent Hispanic) than the use of race had in 1996 (4.1 percent African American and 14.5 percent Hispanic).40 (See Figure 6.) And UT could do even better on racial diversity if it improved outreach to minority students. Princeton University’s Marta Tienda reports that while half of Asian and more than one-third of white Top 10 Percent graduates enroll at one of the public flagships, “just one in four similarly qualified black and Hispanic students” do.41

Figure 6.

University of Washington. In 1998, opponents of affirmative action succeeded in passing an anti-preference initiative in Washington State. Richard McCormick, president of the University of Washington (UW) at the time, spoke out strongly against the referendum and bemoaned the fact that the proportion of black, Hispanic, and Native American students at the university dropped in the first year after implementation of the ban.

But, McCormick and others began to craft new approaches to create diversity. New efforts of recruitment at predominantly minority high schools—including a “student ambassador” program—were launched. Financial aid was expanded, and the university began considering such factors as “personal adversity” and “economic disadvantage.” By 2004, “the racial and ethnic diversity of the UW’s first-year class had returned to its pre-1999 levels,” when race was still considered in admissions, and economic diversity grew as well.42

University of Georgia. Likewise, in 2000, the University of Georgia, faced with an Eleventh Circuit ruling striking down the use of race in admissions, began shifting emphasis to a number of race-neutral strategies. Nancy McDuff of the University of Georgia notes that the university added to admissions considerations a number of socioeconomic factors (such as parental education and high school environment), began admitting the valedictorian and salutatorian from every high school class, and dropped legacy admissions. Although alumni opposed the latter move, the university “has not encountered noticeable fundraising challenges as a result of the change,” McDuff says. Minority enrollment initially dropped after the ban on using race in admission, but it has since moved upward and “the years since 2000 have shown the university moving in the right direction, toward increased racial, ethnic, socioeconomic, linguistic, and geographic diversity on campus.”43

Three Outliers: UC Berkeley, UCLA and the University of Michigan

In Potter’s analysis, three of the ten institutions—the University of California–Berkeley, the University of California–Los Angeles, and the University of Michigan at Ann Arbor—were not able to sustain prior levels of racial and ethnic diversity using race-neutral alternatives, a point that Justice Sonia Sotomayor noted in her dissent in Schutte v. Coalition to Defend Affirmative Action (2014). These results, however, do not suggest more broadly that race-neutral strategies are ineffective—for three reasons.

The three universities could devise stronger race-neutral strategies. To begin with, Michigan has taken only modest steps to increase socioeconomic (and thereby racial) diversity. Michigan still gives preferences in admission to the children of alumni, and still provides substantial “merit” aid to wealthy students, thereby diverting funds from need-based aid. In all, only 15 percent of Michigan students are eligible for federal Pell Grants, compared with more than 25 percent at public flagship universities nationally.44

At the University of California (UC), meanwhile, using better measures of socioeconomic disadvantage, such as wealth or net worth, would likely produce higher levels of African American and Latino representation than UC Berkeley and UCLA currently do with their focus on income.45 Moreover, on the all-important metric of bachelor’s degree attainment, Richard Sander’s research suggests that because African American students are currently better matched within the UC system, overall black graduation numbers have increased following the adoption of the ban on racial preferences. Despite an initial drop in black enrollment within the UC system, average African American bachelor’s degree attainment rose from 802 (from 1997 to 2003, the last cohorts generally admitted through racial preferences) to 926 in the post-ban years of 2004 to 2009.46

The challenge of unilaterally disarming in the competition for minority students. Moreover, the experience of UC Berkeley, UCLA, and Michigan should not be taken as representative of what will happen generally if racial preferences are curtailed or eliminated. The three are national universities that compete for talented black and Hispanic students with other prestigious institutions throughout the country—the vast majority of which continue to use racial preferences and often offer race-based scholarships. Berkeley, UCLA, and Michigan therefore are faced with a very difficult situation, having unilaterally “disarmed” in the battle to recruit talented minority students. This problem is exacerbated because some minority students are understandably interested in attending a school with a strong core of minority classmates and may not even apply, or accept offers of admission, to the relatively few universities now operating under a ban on racial preferences. All of which is to say that the positive racial dividend of economic affirmative action and other race-neutral programs is likely to be greater in the event that all schools are playing by the same set of rules regarding the use of race.

Important shifts in racial data collection. Shifts in how the U.S. Department of Education counts racial groups could explain some, or even all, of the drop in black enrollment at schools such as the University of Michigan cited by Justice Sotomayor. In 2010, the Department of Education changed its methodology for categorizing students by race and ethnicity, requiring colleges to report separately students who are members of two or more races. “So a drop in the number of black students reported at a university from 2009 to 2010,” a Chronicle of Higher Education article noted, “doesn’t necessarily mean that there were actually fewer black students.”47

Consider, for example, the case of the University of Virginia (UVA), which is not subject to a voter-imposed ban on racial preferences and continues to use race as a factor in admissions. In 2008, before students could use the multi-race category, UVA enrolled 1,199 African American students. By 2012, after the change in categories was put in place, the number of African Americans was 946, suggesting a dramatic 21.1 percent drop. But when the 2012 data includes the 206 students who identified as African American and some other ethnicity (for a grand total of 1,152 African Americans under the old methodology), the drop was 3.9 percent. In other words, about 80 percent of the apparent decline in black enrollment at UVA was due to reporting changes.48

Research Simulations of Race-Neutral Programs

What would happen at selective universities if a uniform rule of race neutrality were adopted? Early research, including a 1998 study looking narrowly at income-based affirmative action, suggested that racial diversity would decline, as the Fifth Circuit noted in its Fisher opinion.49 But more recent research shows that a variety of socioeconomic factors—including wealth and neighborhood poverty levels—can produce substantial racial and ethnic diversity.50 Below are three examples.

University of Colorado research. Scholar Matthew Gaertner reports that a sophisticated socioeconomic affirmative action plan at the University of Colorado at Boulder that gives considerable weight to economic disadvantage could achieve even more racial diversity than using race per se. Based on national research, Boulder devised an index of socioeconomic disadvantage that looked at a number of factors. Under the program, socioeconomically disadvantaged students received a preference in admissions that was larger than what black and Hispanic students had been provided in the past.

When simulations were run, socioeconomic diversity increased, as expected, but surprisingly, the acceptance rates of underrepresented minority applicants also increased, from 56 percent under race-based admissions to 64 percent under class-based admissions. The size of the preference seems to explain the result, Gaertner suggests. Gartner found that the class-based admits were about as likely to graduate in six years as underrepresented minorities at Colorado.51

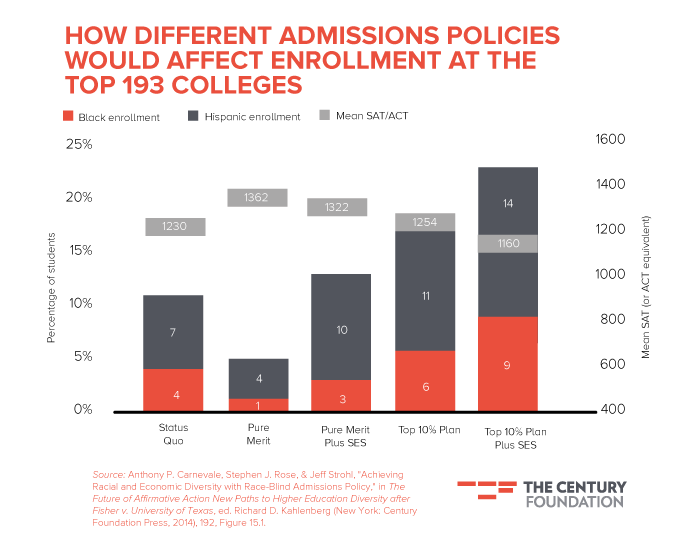

Georgetown University research. Taking a national perspective, in 2014, Anthony Carnevale, Stephen Rose, and Jeff Strohl of Georgetown University looked at how socioeconomic affirmative action programs, percentage plans, or a combination of the two, could work at the nation’s most selective 193 institutions.52 The authors find that combined black and Latino representation under our current system of race-based affirmative action, legacy preferences, athletic preferences, and the like is 11 percent at the most selective 193 institutions. That would drop to 5 percent if test scores were the sole basis of admissions. Under a program of class-based affirmative action using a mix of socioeconomic considerations (such as parental education, income, and savings—a proxy for wealth—and school poverty concentrations), the combined African American and Hispanic representation would rise to 13 percent. Under a simulation in which the top 10 percent of test takers in every high school was among the pool admitted, combined black and Hispanic representation would rise to 17 percent. Under each of these scenarios, socioeconomic diversity and mean SAT scores would also rise.53 (See Figure 7.)

Figure 7.

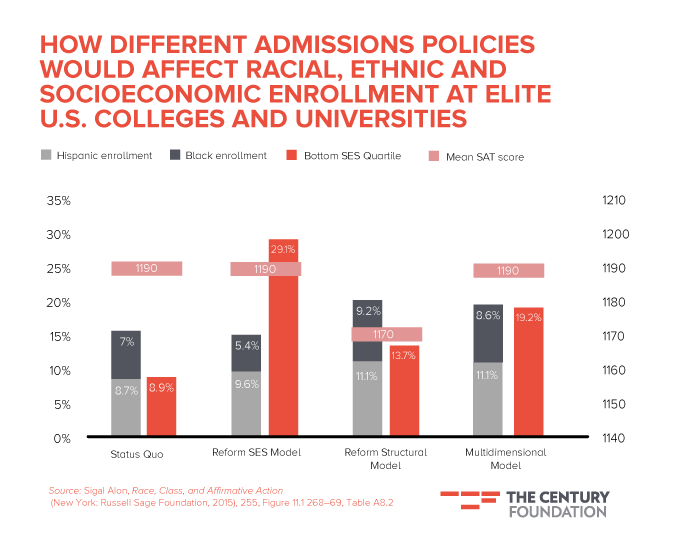

Russell Sage Foundation research. A 2015 study by Sigal Alon of Tel-Aviv University for the Russell Sage Foundation simulated the effects of shifting from race to class-based affirmative action. The study has been cited by supporters of affirmative action in an amicus brief in Fisher II for the proposition that racial and ethnic diversity would decline substantially under certain models of race-neutral affirmative action.54 But what the brief does not mention is that Alon found that if universities instituted broad reform—reexamining legacy and athletic preferences—a socioeconomic boost “could not only replicate the current level of racial and ethnic diversity at elite institutions but even increase it.”55 Under the “reform” model, Alon replaces the bottom academic quartile of students (which she presumes include many receiving legacy or athletic preferences) with those receiving a preference for having overcome socioeconomic obstacles. In this reform model, Alon looks at three variations: (1) a “socioeconomic status” model, which looks at family-based economic disadvantages; (2) a “structural” model, which looks at neighborhood-based economic disadvantages; and (3) a “multidimensional” model, which looks at both. Under such conditions, she finds, racial diversity would meet or exceed current admissions, while socioeconomic diversity would increase. Meanwhile, because mean SAT scores would remain steady, “all this could be done without jeopardizing academic selectivity.”56 (See Figure 8.)

How realistic is it to think that legacy preferences will be eliminated? In fact, several universities—from Texas A&M to the University of Georgia—have eliminated legacies as they become even harder to justify when race was dropped from admissions. And surely there is room to reduce athletic preferences, particularly for obscure sports, such as fencing, dominated by wealthy applicants. More to the point, as a legal matter, universities are unlikely to be able to sustain racial preferences with the argument that they are “necessary” as an offset to legacy and athletic preferences.

A third complaint suggests programs that are aimed at providing access to bright students with fewer family resources will be more expensive for colleges and universities. Some liberals—who would normally support efforts to expand need-based financial aid—curiously raise this issue in their zest to support racial preferences.

Figure 8.

Seeking Diversity by Socioeconomic Status in Addition to Race

Universities tend to measure the effectiveness of race-neutral alternatives exclusively in terms of the racial diversity produced, but if one is examining the overall educational benefits of diversity, a better metric is the effect on socioeconomic and racial diversity taken together. Not surprisingly, race-neutral alternatives that focus on socioeconomic disadvantage or geography produce much higher levels of socioeconomic diversity than do racial preferences, as Figure 8 demonstrates. (See further discussion under section IV.)

Objections Raised Against Race-Neutral Strategies Do Not Make Them “Unworkable”

Critics argue that programs that increase socioeconomic diversity—along with racial diversity—are problematic on three grounds: (1) they will admit unprepared students, (2) they will not admit enough privileged minority students, and (3) they are too expensive to be “workable” race-neutral alternatives. Evidence, however, disproves these claims.

Academic Preparedness of Economically Disadvantaged Students

While some fault race-neutral alternatives for reducing academic standards, research refutes that notion. For example, the Fifth Circuit panel suggested that the Top 10 Percent Plan is flawed because it admits students with “lower standardized test scores.”57 Higher scores, the panel suggests, predict higher levels of graduation.58 But nowhere does the panel point to negative academic consequences associated with the percentage plan in practice. In fact, in 2000, UT’s president noted that “minority students earned higher grade point averages last year than in 1996 and have higher retention rates.”59 Moreover, careful research by Sunny Niu and Marta Tienda of Princeton University found that between 1993 and 2003, black and Hispanic students admitted through the percentage plan “consistently perform as well or better” than white students ranked at or below the third decile.60

Likewise, in a national simulation, Carnevale and Rose found that top universities could nearly quadruple the proportion of students from the bottom socioeconomic half (from 10 percent of all students, the level they found in their research, to 38 percent) without any change in graduation rates.61

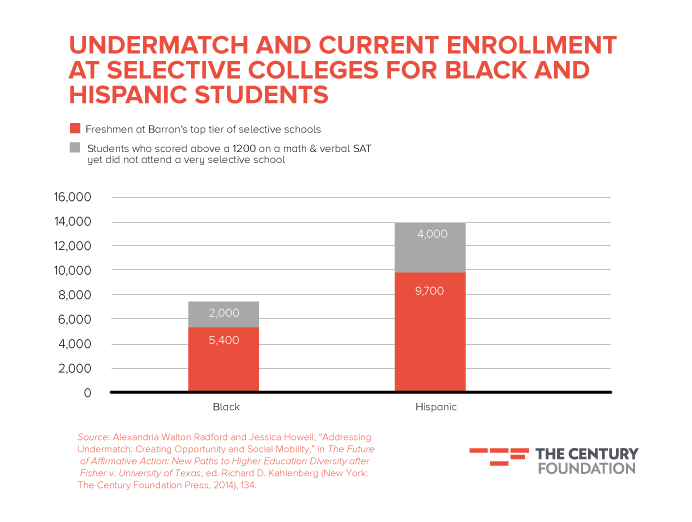

These studies are buttressed by a growing body of research on “undermatching”—in which highly qualified students do not apply to selective colleges. Education researcher Alexandria Walton Radford and College Board economist Jessica Howell note that 43 percent of students who are academically qualified to gain admission to selective colleges undermatch, and that many are Hispanic and African American.62 In raw numbers, that translates into 4,000 Hispanic and 2,000 African American SAT takers who have the strongest academic credentials yet do not attend a very selective school.63 (See Figure 9.)

Figure 9.

Looking at a different national set of students (not just those taking the SAT), and a different definition of high-achieving (those testing in the top 4 percent of high school students), Caroline Hoxby of Stanford and Christopher Avery of Harvard, find that 35,000 low-income students are very high achieving, and that only one-third apply to one of the country’s 238 most selective colleges. Of those low-income high-achieving students, roughly 2,000 are African American and 2,700 Hispanic.64 To put these numbers in context, at Barron’s top tier of selective schools (about 80 institutions), there are currently only 5,400 black freshmen and 9,700 Hispanic freshman from all economic backgrounds. This research suggests there is enormous potential to increase socioeconomic and racial diversity without in any way sacrificing academic quality if colleges were to recruit high achieving low-income students the way they do athletes.

The Argument for “Diversity within Diversity” Is Flawed

The Fifth Circuit panel oddly turned the success of Texas Top 10 Percent Plan in producing socioeconomic and racial diversity on its head by faulting the program for not admitting more privileged students of color who attend more-affluent integrated high schools and could serve as bridge-builders between races.65 The contention is related to an argument advanced earlier by UT that because the percentage plan admitted many minority students who were “the first in their families to attend college,” preferences are needed to admit students such as “the African American or Hispanic child of successful professionals in Dallas” who would defy stereotypes.66 These arguments are problematic for several reasons.

First, privileged minority students are hardly absent on selective campuses, where roughly nine in ten black students is middle or upper class.67 Even in the absence of race-based affirmative action, national research suggests that if academic indicators (such as test scores and grades) were the sole basis for admissions, roughly one-third of the current population of African American and Latino students would be admitted.68 Furthermore, those from privileged backgrounds are most likely to qualify without consideration of race because within every racial group, the highest test takers tend to be the most affluent. Indeed, if universities believe they need to use racial preferences to ensure economic diversity within minority groups, why in the past have they not sought out more low-income black students to counter the predominance of middle- and upper-class black students on campus?

Second, if universities are specifically seeking students who are bridge-builders, racial preferences for privileged students of color are an unnecessary and blunt instrument. Instead, students of all races who have demonstrated that in the past they have been leaders in fostering interracial dialogue could receive special consideration. Indeed, there is evidence that because low-income whites have greater experience interacting with minority students in high school, they are more likely to engage across race in college.69 If universities are highly concerned about finding bridge builders, why does careful research suggest that universities provide no boost to disadvantaged whites, controlling for other factors?70

Third, from a basic fairness perspective, UT’s argument is deeply troubling. Morally and politically, the Achilles Heel of affirmative action is that it often benefits well-off minority students. President Barack Obama recognized this when he said that his own daughters do not deserve affirmative action preferences.71 For UT to put the cause of privileged minorities front and center in its legal case is curious in the extreme.

Indeed, UT’s argument for racial preferences on behalf of privileged students of color is precisely the opposite of the race-blind class-based approach advocated by Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. In his 1964 book Why We Can’t Wait, King wrote that compensation is due to black Americans.72 But instead of urging adoption of a program for blacks, as some civil rights leaders had done, King called for a racially inclusive Bill of Rights for the Disadvantaged. A class-based affirmative action program would help the young Michelle Obama or the young Sonia Sotomayor, but not Sasha or Malia Obama.

Higher Cost of Race-Neutral Alternatives Does Not Make Them “Unworkable”

A third complaint suggests programs that are aimed at providing access to bright students with fewer family resources will be more expensive for colleges and universities. Some liberals—who would normally support efforts to expand need-based financial aid—curiously raise this issue in their zest to support racial preferences.73

But racial affirmative action cannot be justified on the basis that it is a cheaper option. As attorneys Arthur Coleman and Teresa Taylor note, the Supreme Court has often rejected cost as a rationale for abrogating rights when applying the strict scrutiny test. In Saenz v. Roe (1999),74 for example, the Court rejected the argument that California could impinge on the right to travel by reducing welfare benefits to those who were new to the state. The state said the rule saved taxpayers $10 million per year, but the Court ruled: “the state’s legitimate interest in saving money provides no justification for its decision to discriminate among equally eligible citizens.”75 Coleman and Taylor write: “an institution should not assume that cost savings alone can justify the ongoing use of a race-conscious policy.”76

Indeed, the Obama administration’s assistant secretary for civil rights at the U.S. Department of Education, Catherine Lhamon, has argued that given Fisher’s requirement to pursue workable race-neutral alternatives, it would be difficult for a university to argue that a strategy is unworkable for financial reasons if the institution devoted resources to non-need merit aid that could be shifted to need-based aid.77

The Need to Look for Alternatives

In sum, given the viability of alternatives, it will be increasingly difficult for universities to justify racial preferences as “necessary” to promoting racial diversity. As a 2013 article in the Harvard Law Review noted, as more universities pursue successful race neutral strategies, “the bar will continue to rise on what it means to demonstrate that ‘no workable race-neutral alternatives’ are available. A university will have increasingly difficulty claiming that no workable race-neutral alternatives exist if peer institutions have developed and successfully implemented such alternatives.”78

The experience of K–12 education with race-neutral strategies may be instructive. In 2007, the Supreme Court issued a ruling in Parents Involved in Community Schools v. Seattle, which struck down a racial integration plan and encouraged school districts to find alternative means to promote diversity. While Justice Kennedy’s opinion in Parents Involved technically left the door open for using race as a last resort, it gave a strong push to districts to find race-neutral strategies, just as Fisher II is likely to do. Today, more than 80 school districts educating 4 million students have adopted socioeconomic integration plans, and voluntary racial integration programs are virtually unknown. It is time for universities to begin contingency planning. Private universities receiving federal funds will be just as affected by Fisher II as public institutions.79

A Positive Vision of the Future of Affirmative Action

If the Supreme Court severely restricts the ability of universities to use race, what will new forms of affirmative action look like? It is possible that some schools will simply throw up their hands and give up. But the experience of states where affirmative action has been banned (usually by voter referendum) suggests that universities can—and will—pursue a number of new strategies. When the American Council on Education surveyed colleges on race-neutral strategies it reported that “The 19 institutions in our study that discontinued the consideration of race subsequently poured their energies into alternative diversity strategies.”80

Economic Affirmative Action in States that Have Banned Racial Preferences

In 2014, Halley Potter examined ten states where the use of race was eliminated by voter initiative or other means at leading universities. In these states, several race-neutral strategies have been adopted that can be broken down into six broad categories.81

Pipeline and recruitment efforts. Six states have spent money to create new partnerships with disadvantaged schools to improve the pipeline of low-income and minority students and boost recruitment. Recruitment is a relatively noncontroversial but reportedly effective way of boosting minority enrollment.82

Class-based affirmative action. Eight states have provided new admissions preferences to low-income and working-class students of all races. For example, in California, Richard Sander writes, after racial preferences were banned by voters there was a striking “jump in the interest of administrators and faculty in the use of socioeconomic metrics as an alternative to race in pursuing campus diversity.”83

Financial aid. Eight states have expanded financial-aid budgets to support the needs of economically disadvantaged students. For example, in the same year that Nebraska voters banned affirmative action, the Nebraska Board of Regents expanded financial aid offering free tuition to all Nebraska Pell Grant recipients. Likewise, in the years after racial preferences were banned, the University of Florida began offering full scholarships to first-generation freshmen from low-income families.84

Dropping legacy preferences. In three states, individual universities have dropped legacy preferences for the children of alumni. For example, the University of California at Berkeley, UCLA, the University of Georgia, and Texas A&M, after dropping race from consideration, all discontinued the use of legacy preference.85 This change in admissions policies can have a beneficial impact on racial minorities because legacy preferences disproportionately benefit white students.86 While conventional wisdom suggests that legacy preferences are a valuable mechanism for raising university funds, careful research finds they have no effect.87

Percentage plans. In three states—Texas, California, and Florida—officials created policies to admit students who graduated at the top of their high-school classes. While percentage plans may not easily translate to public or private universities with national pools of applicants, or to graduate programs, important aspects of percentage plans can be applied broadly. First, programs that enhance geographic diversity, and leverage the unfortunate reality of residential and high school segregation by race and class for a positive purpose, can promote integration in higher education.88 Second, percent plans focus exclusively on class rank by high school GPA, effectively eliminating reliance on SAT and ACT test scores. High school grades are a better predictor of college performance than SAT scores, and have a much less discriminatory impact against minority students. Nearly 850 colleges and universities have already gone “test-optional,” including leading institutions such as Bowdoin, Smith, Bates, and Wake Forest.89

Community college transfers. In two states, stronger programs have been created to facilitate transfer from community colleges to four-year universities to promote diversity. For example, in 1997, in the wake of California’s ban on racial preferences, Halley Potter notes, “UC signed a memorandum of understanding with the State of California pledging to increase community college transfer enrollment at UC campuses by a third, and in 1999 UC increased the commitment to a 50 percent increase. In 2008–09, 26.3 percent of new students enrolling in the UC system were transfers from California community colleges.”90 Elite private colleges have also expanded community college transfer programs in order to enhance racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic diversity. From 2006 to 2010, the Jack Kent Cooke Foundation Community College Transfer Initiative allowed more than one thousand community college students to transfer to eight highly selective four-year institutions—Amherst, Bucknell, Cornell, Mount Holyoke, UC Berkeley, the University of Michigan at Ann Arbor, the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, and the University of Southern California.91

Affirmative Action that Recognizes the Economic Drivers of Inequality of Opportunity

When race-based affirmative action programs were devised nearly fifty years ago, in the wake of legalized segregation and apartheid, race was a much bigger predictor of academic achievement than class. The test score gap between black and white students was twice as large as the gap between high-income and low-income students. Today, however, according to an analysis by Stanford University’s Sean Reardon on nineteen nationally representative studies, these roles have been reversed: the income achievement gap is twice as large as the racial achievement gap.92

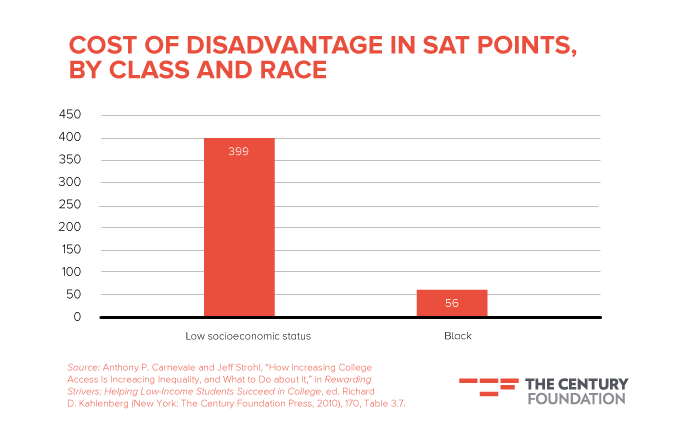

Moreover, when one teases out the underlying factors that account for the achievement gap, the role of class becomes even more pronounced. In 2010, researchers Anthony Carnevale and Jeff Strohl of Georgetown University took a sophisticated look at what predicts student scores on standardized tests such as the SAT. Using regression analysis, the researchers found that coming from the most socioeconomically disadvantaged family predicts a score that is an incredible 399 points lower on the math and verbal sections of the SAT (on a 400–1600 point scale). The racial gap between black and white students was a much smaller 56 points. (See Figure 10.)

Figure 10.

To be clear, the relative size in SAT penalties associated with class does not mean that racial discrimination has a small impact on life chances. Racial discrimination in employment, for example, reduces the income of African American families, which means black children are much more likely to fall into the economically disadvantaged category. The point, instead, is that racial discrimination has economic manifestations that can be captured in class-based affirmative action programs.

Class-based Programs That Are Not Oblivious to Race, but Avoid the Downsides of Racial Preferences

Using Racialized SES Factors

Well-crafted race-neutral alternatives, while not providing a blanket preference by race, are nevertheless cognizant of the ways in which past and present racial discrimination shape opportunities in America.

In Schuette v. Coalition to Defend Affirmative Action, Justice Sotomayor eloquently outlined the ways in which race matters in American society and concluded that racial preferences were a necessary response.93 Likewise, the Fifth Circuit criticized socioeconomic affirmative action programs as flawed because they “conclude that skin color is no longer an index of prejudice.”94

In fact, however, socioeconomic alternatives work to produce racial diversity precisely because economic disadvantage is often shaped by racial discrimination. Discrimination helps explain why black and Hispanic Americans on average have smaller savings than whites do, and why even middle-class blacks live in neighborhoods with higher poverty rates than low-income whites.

Research finds that when socioeconomic affirmative action programs are constructed using a wide variety of variables—not just parental income, but highly racialized factors such as wealth/net worth, and neighborhood and school levels of poverty—they can produce substantial racial and ethnic diversity, precisely because this wider array of socioeconomic factors better captures the economic impact of ongoing and past racial discrimination than does income (or race) alone.

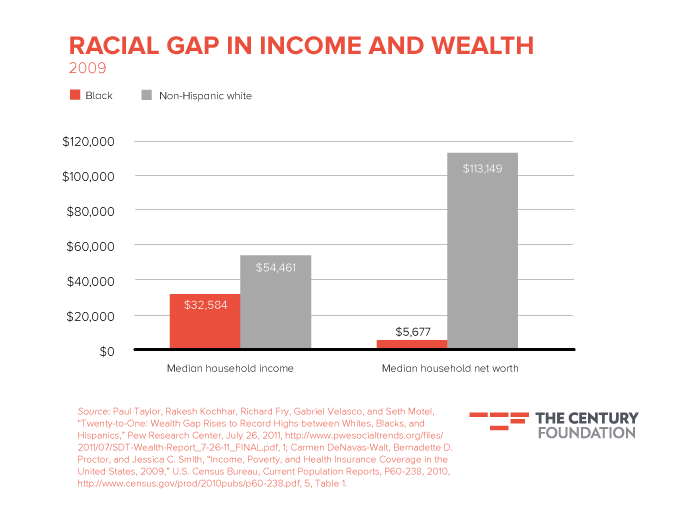

Wealth is highly racialized. New York University’s Dalton Conley finds that wealth, because it is handed down from generation to generation, better reflects the nation’s legacy of slavery and segregation than does income.95 Black Americans typically have incomes that are 60 percent of white incomes, but black wealth is just 5 percent of white wealth. (See Figure 11.)

Figure 11.

Having said that, using wealth in admissions is not just a clever ruse to get around a prohibition on considering race. Parental wealth and education actually are far more powerful predictors of college completion than race or income, Conley finds.96 Wealth matters more than income, Conley notes, because “educational advantages are acquired through major capital investments/decisions,” such as purchasing a home in a neighborhood with good public schools.

Concentrated poverty is highly racialized. Growing up in concentrated poverty also imposes disadvantages on children, so as a matter of fairness should be considered in admissions. And because it is highly racialized, it will capture the effects of discrimination in the housing market, where black and Hispanic families with incomes in excess of $75,000 live in neighborhoods with higher poverty rates than white families earning less than $40,000.97 New York University’s Patrick Sharkey notes that while 6 percent of young whites live in neighborhoods with more than 20 percent poverty rates, 66 percent of African Americans do.98 Plans that give a preference to students growing up in concentrated poverty will acknowledge the extra burden that, in the aggregate, poor black children face much more often than poor white children.

Racialized Economic Indicators Are Not Crude Proxies but Rather Better-Targeted Tools

Some critics of race-neutral alternatives such as percentage plans or socioeconomic affirmative action efforts say they use class merely as a proxy for race—that they are subterfuges seeking a desired racial result covertly. But this thinking has it backward, because the beneficiaries are a very different subset of black and Latino students than those who usually benefit from affirmative action. The new beneficiaries are more likely to be from working-class or low-income families that bear the brunt of segregation. As Georgetown law professor Sheryll Cashin notes, place-based approaches help “those who are actually disadvantaged by structural barriers” rather than enabling “high-income blacks to claim the legacy of American apartheid.”99

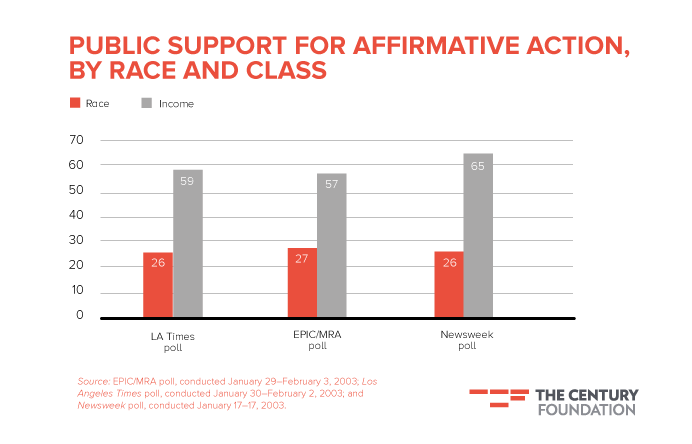

Moreover, programs that emphasize economic need can reduce the resentment associated with racial preferences. Under a system of class-based affirmative action there will, of course, be wealthy people who resent low-income applicants who “just got in because they are poor.” But there likely will be many fewer such complaints, because Americans broadly recognize that economically disadvantaged students of all races have overcome significant obstacles and therefore support economic affirmative action at far higher rates than they support race-based affirmative action. According to three sets of polls conducted around the time of the Grutter v. Bollinger decision, Americans oppose racial preferences by two to one but support income based preferences by roughly the same margin. (See Figure 12.)

Figure 12.

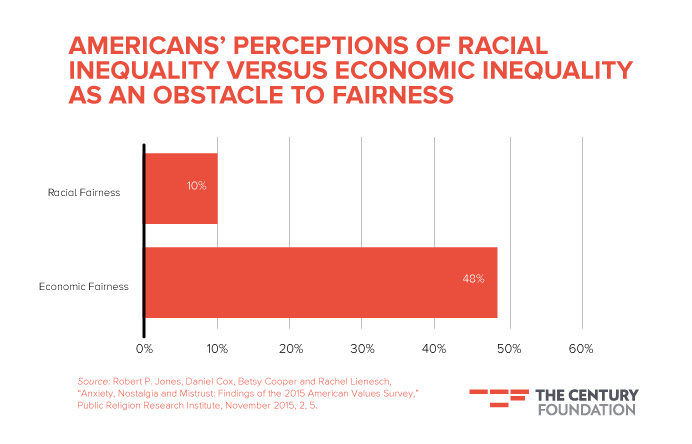

While there does not appear to be more recent polling specifically comparing attitudes on class-based versus race-based affirmative action, a 2015 survey by the Public Religion Research Institute found that Americans are almost five times more likely to view economic inequality as a very high obstacle to fairness than racial inequality. (See Figure 13.) The survey asked a number of questions gauging perceived levels of racial and economic unfairness in American society, and created a composite Economic Inequality Index and Racial Inequality Index. The researchers found that 48 percent of Americans perceive very high levels of economic unfairness, 21 percent high amounts, 20 percent moderate amounts, and 11 percent “perceive the economic playing field to be basically level, scoring low on the EII.” By contrast, on the Racial Inequality Index, the poll found that only 10 percent of Americans perceive very high inequality, 23 percent perceive high levels, 21 percent fall into the moderate category, while 38 percent perceive low and 8 percent very low levels of inequality, “believing that racial minorities today have equal opportunities as whites.”100

Figure 13.

Not surprisingly, the American public remains highly skeptical of efforts to count race as a factor in admissions to colleges and universities. While the amorphous phrase “affirmative action” garners support among Americans, a 2013 Gallup poll that specified the actual practice colleges engage in—using race as a factor in admissions decisions—found that Americans disapprove of doing so by a 67 percent to 28 percent margin.101

Economic Affirmative Action Can Jumpstart Social Mobility

Given their economic focus, class-based affirmative action programs have opened the doors of opportunity to large numbers of economically disadvantaged students who do not benefit from racial affirmative action. These students include not only disadvantaged white and Asian students, but also disadvantaged black and Latino students. The experiences of California and Texas are instructive.102

In California, research by Kate Antovics of UC San Diego and Ben Backes of the American Institutes for Research finds that after racial affirmative action was banned, students from economically disadvantaged backgrounds saw a substantial increase in the probability of admissions.103 Likewise, when UCLA Law School adopted a socioeconomic affirmative action program, Richard Sander reports, the proportion of students who were the first in their families to attend college roughly tripled.104

It seems hardly an accident, therefore, that when David Leonhardt of the New York Times published a “College Access Index” ranking schools with high graduation rates that are “doing the most for low-income students,” the list was dominated by University of California institutions. Leonhardt noted “California’s Upward-Mobility Machine.”105

Nationally, of the top ten public institutions for social mobility, six were from the UC system, and nine were from states that had banned racial affirmative action. (The University of Florida, University of Washington, and University of Georgia also made the top ten.) Of the top fifteen public institutions for social mobility, twelve (or 80 percent) were in states that banned affirmative action. By contrast, in the bottom half for social mobility, sixteen of seventeen (or 94 percent) of public institutions were in states that can employ racial preferences in admissions and therefore have no need to look to socioeconomic alternatives.106

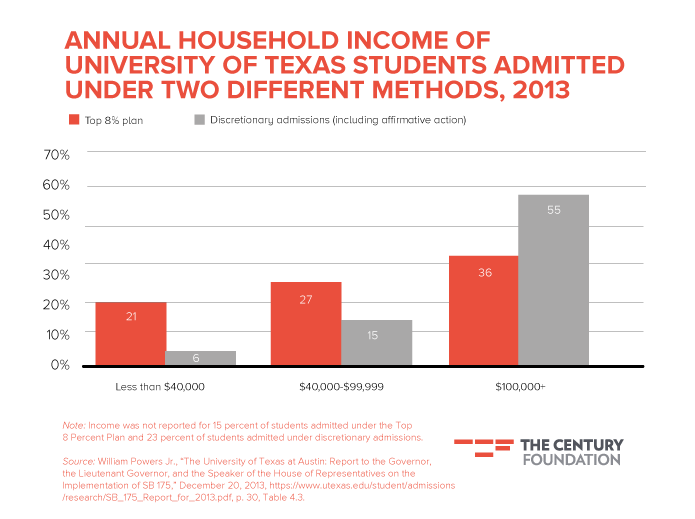

UT Austin and Texas A&M both made the New York Times top fifteen public institutions, which is not surprising, because the Texas Top 10 Percent Plan produces substantial socioeconomic diversity. Roughly three-quarters of students at UT Austin are admitted through the percentage plan, and one-quarter through discretionary admissions (which, after 2004, began to include race again). In 2013 (when the top 8 percent were admitted), 21 percent of incoming students admitted through the percent plan were from families making less than $40,000, compared with 6 percent of those admitted under discretionary admissions.107 (See Figure 14.)

Figure 14.

Federal Public Policy Supports: Social Mobility Carrots and Sticks

States that have enacted racial affirmative action bans have largely had to respond on their own to create new paths to diversity. But a federal ruling by the U.S. Supreme Court to sharply curtail racial preferences would arguably call for a national response to help both public and private universities transition from race to class-based affirmative action policies.

To garner broad political support, a national program could include a combination of carrots and sticks.

Incentives for Colleges Promoting Social Mobility

The federal government might consider providing financial incentives to institutions which enroll—and succeed in educating—low-income students. This concept has garnered strong bipartisan support in places such as Tennessee, where state colleges receive a 40 percent funding premium when they have success with students who are low-income (defined as eligible for federal Pell Grants) or adult learners (age 25 or over).108 A federal program could serve both as an incentive for colleges to act and a funding stream to offset increased costs for financial aid and support programs to help students succeed.

Penalties to Spur Colleges to Act

Individuals across the political spectrum have expressed concern that selective private universities receive enormous tax exemptions and supports (to the tune of $105,000 per pupil annually, for example, at Princeton University) without always serving the public interest.109 As a condition for receiving federal tax exemptions, colleges could be required to improve their commitment to social mobility. Likewise, receipt of federal funds could be conditioned upon eliminating policies that discriminate based on lineage, such as legacy preferences.110

Socioeconomic Data on Wealth and Concentrated Poverty

Because the legacy of racial discrimination manifests itself most powerfully in certain socioeconomic indicators—such as family wealth and neighborhoods of concentrated poverty—the federal government should provide universities with easy access to such data. The Free Application for Federal Student Aid (FAFSA) should continue to provide information about family wealth. And the federal government should provide a free central database through which admissions officers can easily plug in a student’s address to access data on her neighborhood’s poverty level.

New Political Possibilities for Higher Education and Beyond

The transition from the use of racial preferences to economic preferences in higher education offers the possibility of fascinating new political alliances for colleges and for American society at large.

The New Politics of Higher Education

Within higher education, affirmative action has for fifty years served as a sort of bandage that helps hold a deeply inequitable system together. Because minorities won affirmative action preferences, civil rights groups made their peace with legacy preferences and have declined to join efforts to challenge the preferences for the children of alumni (most of whom are wealthy and white). And leading civil rights groups entered into what attorney John Brittain called a “gentleman’s agreement” not to challenge the SAT and ACT for having a discriminatory disparate impact on minority students.111

As Sheryll Cashin notes, affirmative action policies help prop up a generally unfair system that includes legacy preferences, non-need merit aid, and an overreliance on standardized tests. The “optical diversity” that racial preferences create “undermines the possibility that elite colleges will rethink exclusionary practices.” A superficial “diversity by phenotype puts no pressure on institutions to dismantle underlying systems of exclusion that propagate inequality,” she writes.112

Likewise, Harvard law professor Lani Guinier suggests affirmative action “has failed because it has not gone far enough to address the unfairness of both our current merit system and its wealth-driven definition of merit.” Affirmative action tends to “simply mirror the values of the current view of meritocracy,” Guinier notes. Colleges tend to admit “the children of upper-middle class parents of color who have been sent to fine prep schools just like the upper-middle class white students.” Minority students might serve as “canaries” in the defective mine, putting all on notice that the system of merit unfairly mirrors wealth. But by “admitting a small opening for a select few students of color,” Guinier charges, affirmative action policies actually help buttress the larger unfair apparatus.113

What will happen if the Supreme Court rips off the bandage? One possibility is that no new medicine will be applied, and wounds will get worse. In 1996, that was a possibility, when Californians voted to ban racial preferences, which is why sensible California residents should have cast their ballots against the affirmative action ban. Racial preferences are deeply flawed, but having nothing in their place to address our history of discrimination would have been worse. But the good news is that the twenty years of experience since then—in California and other states—suggests that almost everywhere, new and better forms of affirmative action have been created. If racial preferences are politically unpopular, on the one hand, the political system will not tolerate the resegregation of higher education on the other.

In states where racial preferences have been banned, for example, civil rights groups got off the sidelines and attacked legacy preferences. The unfair advantages provided to the children of alumni were discontinued at Texas A&M, the University of California, and the University of Georgia because of pressure from civil rights advocates. It also became in the interest of civil rights groups to support class-based affirmative action as an indirect way of promoting racial diversity.

This shift was very important politically, because poor and working-class people do not command media attention in the way civil rights advocates do. So far, few universities have adopted class-based affirmative action programs on their own (absent a ban on race), because there is no real political pressure to do so. Poor and working-class people of all races have not protested and drawn attention to what have been called “the hidden injuries of class” on college campuses.

By contrast, middle-class civil rights groups are very good at mobilizing. Consider, for example, the recent campus protests at places such as the University of Missouri, Claremont McKenna College, and Yale University. These protests are vivid reminders that racial injuries are real and that race still matters in American society. At the same time, the considerable media coverage of the protests—and their effectiveness in winning change—underscores the power of civil rights activists in American society. Black protesters were able to gain the resignation of a university president (Missouri), a dean (Claremont), and a pledge to invest considerable resources into the study of race (Yale).

If universities lose the ability to use race in admissions, the power of civil rights groups is likely to be employed on behalf of programs for economically disadvantaged students of all races as a way to indirectly promote racial and ethnic diversity. The political power of civil rights groups gives good reason to believe that universities will prioritize racial diversity enough to employ alternatives.

Changing the Broader Politics of American Society

Ending or curtailing racial preferences could spur an important and broader change in American politics. Fifty years of racial preferences have exacted a steep political price for the progressive coalition. Working-class whites, once a mainstay of the Democratic Party, are especially skeptical of affirmative action. Surprisingly, a 2015 Public Research Religion Institute survey finds that 60 percent of working-class whites say that discrimination against whites has become as big a problem today as discrimination against blacks and other minorities.114

These voters, notes Sheryll Cashin, “are much closer in circumstances to working-class blacks and Latinos than they are to whites higher up the income scale.” For years, Cashin writes, Southern gentry sought to prevent interracial cooperation by pitting working-class blacks and whites against each other. So why, she asks, have liberals embraced a policy that “pushes away potential allies” in a way that can only make Karl Rove smile? “What we need is a politics of fairness,” Cashin says, “one in which people of color and the white people who are open to them move past racial resentment to form an alliance of the sane.”115

Just such a coalition formed around Texas’s Top 10 Percent Plan for college admissions, which rearranged traditional political alliances. While race and ethnicity are powerful fault lines in Texas politics, the battle over the percent plan fell along class lines. Wealthy suburban families did not like the plan because their high-scoring kids had to compete against one another for a limited number of slots in each high school. Meanwhile, working-class whites, blacks, and Latinos rallied around the plan because high schools that had never sent someone to UT Austin would suddenly be able to have access to the state’s flagship.

A few years back, when UT Austin tried to significantly curtail the number of seats that would be awarded through the Top 10 Percent Plan (so that the university would have greater discretion over admissions), a remarkable coalition of rural white conservative legislators representing working class whites, and black and Latino urban legislators representing working-class people of color, blocked the effort.

This type of political coalition is precisely what Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. envisioned in 1964 when he proposed his class-based, racially inclusive affirmative action program—a Bill of Rights for the Disadvantaged. In a letter to his freelance editor for the book, King explained the politics of including working-class whites:

It is my opinion that many white workers whose economic condition is not too far removed from the economic condition of his black brother, will find it difficult to accept a “Negro Bill of Rights,” which seeks to give special consideration to the Negro in the context of unemployment, joblessness, etc. and does not take into sufficient account their plight (that of the white worker).116

And of course there was a second reason for King’s decision to back class-based affirmative action. In his book, Why We Can’t Wait, King wrote that while the program would disproportionately benefit black Americans, “It is a simple matter of justice that America, in dealing creatively with the task of raising the Negro from backwardness, should also be rescuing a large stratum of the forgotten white poor.”117

King’s aide, Bayard Rustin, knew that many liberals rejected coalitions with working-class whites, because some white workers expressed racist sentiments. But Rustin argued that lower-middle-class whites were neither liberal nor conservative but both; and how they acted would depend on how issues were framed.118 Racial preferences inevitably divide working-class whites and blacks, whereas class-based preferences reinforce what the two groups have in common. Policies like compulsory busing for racial desegregation in Boston pit working-class whites and blacks against one another, while wealthy white children in the suburbs were not affected. But, as writer J. Anthony Lukas recognized in his book, Common Ground, in fact the two urban groups had far more in common than either did with the affluent whites in the suburbs.119 Lukas asked in 1995, “What kind of alliance could be cobbled together from people who feel equally excluded by class, or by some combination of race and class?”120 With the end of racial preference and the creation of new class-based remedies, we can begin to answer that important question.

Conclusion

The fight for civil rights in America is often seen as having a moral component. Debates over antidiscrimination legislation and voting rights, for example, were very much viewed as a contest between “good guys” and “bad guys.”

In the discussions about affirmative action, colleges and universities see themselves as taking the moral high ground, defending civil rights against a conservative U.S. Supreme Court. It is understandable why many liberals pick sides on that basis alone.

But the evidence in this issue brief seeks to dispel that convenient but misleading story line. In reality, the use of racial preferences helps prop up a larger system that perpetuates the support of a black elite alongside a white elite. While a multiracial perpetuation of privilege is to be preferred to an all-white one, is this really the best we can do?

Of course not. The choice is not between racial preferences or nothing. We have advanced far beyond the day when universities could claim there was “no other way” to achieve diversity, short of racial preferences. Texas has found a way, as has Washington, Georgia, Florida, and several other states. Ironically, it may take a conservative U.S. Supreme Court to advance us to a place where we recognize that even in America—especially in America—class matters.

Notes

-

1. Anthony P. Carnevale and Jeff Strohl, “How Increasing Access Is Increasing Inequality and What to Do About It,” in Rewarding Strivers: Helping Low-Income Students Succeed in College, ed. Richard D. Kahlenberg (New York: The Century Foundation Press, 2010), 137, Figure 3.7.

2. “Fisher v. University of Texas,” Scotusblog, http://www.scotusblog.com/case-files/cases/fisher-v-university-of-texas-at-austin-2/.

3. Grutter v. Bollinger, 539 U.S. 306, 324.

4. Id, at 330.

5. Id, at 332.

6. Thomas R. Dye, Who’s Running America? The Obama Reign ( Boulder, Colo.: Paradigm Publishers, 2014), 180, Table 8.2.

7. Nancy Cantor and Peter Englot, “Defining the Stakes: Why We Cannot Leave the Nation’s Diverse Talent Pool Behind and Thrive,” in The Future of Affirmative Action, ed. Richard D. Kahlenberg (New York: The Century Foundation Press, 2014), 28–30.

8. Quoted in Richard D. Kahlenberg, The Remedy: Class, Race and Affirmative Action (New York: Basic Books, 1996), 171.

9. Grutter, at 324.

10. Fisher v. University of Texas, 133 S.Ct. 2411, 2420 (2013).

11. Regents of University of California v. Bakke, 438 U.S. 265, 298-299 (1978).

12. Anna Holmes, “Variety Show,” New York Times Magazine, November 1, 2015, 23.

13. Sheryll Cashin, Place Not Race: A New Vision of Opportunity in America (Boston: Beacon Press, 2014), xvi.

14. See Brief of Harvard University, Brown University, The University of Chicago, Dartmouth College, Duke University, The University of Pennsylvania, Princeton University, and Yale University as Amicus Curiae Supporting Respondents, U.S. Supreme Court in Grutter v. Bollinger and Gratz v. Bollinger, p. 22, n.13.

15. Anthony P. Carnevale and Stephen J. Rose, “Socioeconomic Status, Race/Ethnicity, and Selective College Admissions,” in America’s Untapped Resource: Low-Income Students in Higher Education, ed. Richard D. Kahlenberg (New York: The Century Foundation Press, 2004), 135.

16. Ibid., 142.

17. William G. Bowen, Martin A. Kurzweil, and Eugene M. Tobin, Equity and Excellence in American Higher Education (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2005), 105, Table 5.1.

18. Thomas J. Espenshade and Alexandria Walton Radford, No Longer Separate, Not Yet Equal (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 2009), 92, Table 3.5.

19. Ibid., 98, Figure 3.9.

20. Sean F. Reardon, Rachel Baker, Matt Kasman, Daniel Klasik and Joseph B. Townsend, “Can Socioeconomic Status Substitute for Race in Affirmative Action College Admissions Policies? Evidence From a Simulation Model,” Educational Testing Service, 2015, 6.

21. Richard Sander, “Class in American Legal Education,” Denver University Law Review 88 (2011): 631.

22. Anthony P. Carnevale and Jeff Strohl, Separate and Unequal: How Higher Education Reinforces the Intergenerational Reproduction of White Racial Privilege (Washington, D.C.: Georgetown University, 2013), 12.