The Middle East and North Africa region (MENA) is falling behind in meeting the Sustainable Development Goals (SDG)—the seventeen targets that the UN has set for the world to achieve by 2030. Of particular concern for the region are those SDGs related to nature, the environment, and climate change. The region uses much more water than what is replenished; the changing climate exacerbates water stress, undermines agricultural production, and threatens human health; marine ecosystems are plagued by overfishing and pollution; land degradation reduces biodiversity and contributes to extensive dust storms. Tension around the use of scarce water and other resources contributes to insecurity, while ongoing violent conflicts stand in the way of addressing the environment and climate change. To make matters worse, civil society and the media face repression from authoritarian states when they highlight the environmental and climate crises.

The cross-border nature of shared resources requires collaborative action. Water, for example, moves along the natural contours of MENA landscapes and does not follow administrative delineations. But political rivalries and weak regional organizations prevent joint solutions. At the national level, broad policy instruments, investments, and legislation are needed. These far-reaching changes are difficult to conceive of if not part of political reform. The international community must avoid furthering regional fragmentation, but also contribute to integrated transboundary approaches, recognizing the close linkage between sustainable development and security. It can help provide protected spaces for dialogue among key stakeholders and should mobilize resources for nationally owned stabilization—building peace and development—and protection of those most at risk in the current interlinked crises.

The Challenge

The countries of the MENA region are closely linked through shared natural resources, landscapes, and seascapes. Many of them are directly or indirectly involved in the internal affairs and conflicts of their neighbors, or suffer from such involvement. But the region’s joint institutions are weak and not mandated to address its many common and transboundary problems. This institutional weakness cripples efforts at agreeing on the sustainable use and management of shared natural resources, exacerbating the risk of tension and conflict. Ongoing conflicts are, in turn, obstacles to addressing current and looming environmental and climate crises. Nature and security are inextricably linked. On any one of these crises and conflicts, an acknowledgment of this connectedness should guide action—whether from inside the region or by the international community.

The Arab region is not on track to achieve the SDGs, and risks being left behind by the rest of the world.

The Arab region is not on track to achieve the SDGs, and risks being left behind by the rest of the world. This is the stark conclusion of the UN’s 2020 “Arab Sustainable Development Report,” in which progress on each of the seventeen goals of Agenda 2030 is assessed.1 Despite the region’s heterogeneity, the report identifies a number of common barriers to sustainable development. Foremost are the absence of integrated policymaking, structural economic dysfunctionalities leading to natural resource depletion, and a fundamental disrespect for human rights. For many countries, ongoing violent conflicts are also immediate obstacles to sustainable development.

Several of the SDGs focus on nature and the environment; studying their status helps us understand the nature–security challenges faced by the region.

Water

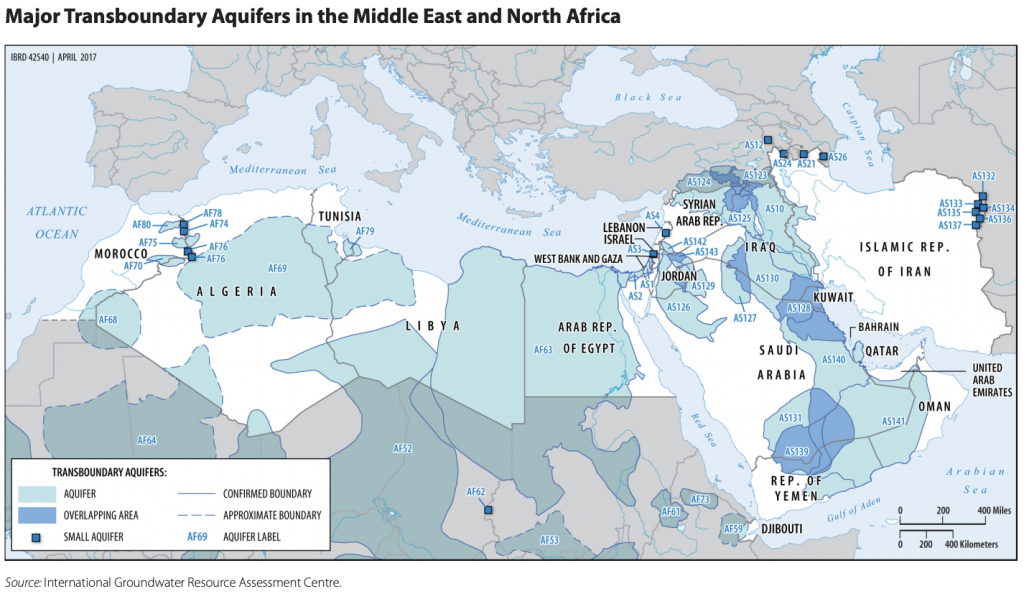

The MENA region is the most water-stressed in the world—six times more so than the global average.2 Many of its aquifers are at high risk of becoming depleted. Sixty percent of its water originates outside of the region, and most countries share aquifers and surface water with their neighbors.3 Yet there are very few transboundary agreements on the use and management of shared water. The problem is made more serious by population increase, policies that subsidize the cost of water rather than encouraging efficient use, and a warming and drying climate. Pollution threatens water quality and human health, most seriously in the occupied Gaza Strip.

Climate Change

The MENA region is highly exposed and increasingly vulnerable to the dangers caused by the changing global climate, which is having wide-ranging and complex social and economic consequences. Such consequences include the exacerbation of the water crisis and inadequate or declining agricultural and livestock productivity. Further, heat stress is life-threatening to humans who are unable to protect themselves with shelter and air conditioning. The summer of 2020 saw weeks with temperatures above 50 degrees Celsius (122 Fahrenheit) in Iraq and the Gulf states.4 Atypical extreme weather events, such as storms and floods, are happening more often. Sea level rise and saltwater intrusion threaten densely populated river deltas. The adaptive capacity of communities and governments to deal with the effects of climate change is undermined by conflicts and displacement. Efforts by oil-producing states to increase the domestic share of renewable energy are not necessarily intended to contribute to a reduction of greenhouse gas emissions (a global concern). A recent study of climate policy implementation in the United Arab Emirates and Oman concludes that increased domestic renewable energy production and consumption are simply used to increase oil exports, cancelling out their value in terms of greenhouse gas reduction.5 Yet despite the burden that a warming planet is causing for the region, awareness of climate change is generally low among authorities and the public.6

Ecosystems and Biodiversity

Availability of data on the state of the MENA region’s seas is poor, with the exception of the Mediterranean, making monitoring difficult. Still, it is clear that overfishing, warming, and acidification threaten fisheries. Key species are being depleted. The world’s largest dead ocean zone is found in the Gulf of Oman.7

On shore, extensive land degradation and desertification, exacerbated by climate change, are threats to biodiversity and food security. Land degradation causes large cross-border sand and dust storms. Agricultural productivity is stagnant, demanding steadily increasing food imports as the population grows. Almost all people in the region are exposed to air pollution above hazardous levels.8

These downward environmental trends add strain to societies already struggling under increasing impoverishment and inequality.9 The MENA region is the only major area in the world where poverty is increasing, and this increase is largely associated with ongoing conflicts.10 As always, it is the poorest, most marginalized, and unprotected who suffer the most from the interlinked environmental crises. Rural dwellers depending on agriculture, livestock, or fisheries see their livelihoods undermined, fueling rural–urban migration. In cities, water scarcity adds volatility to what is already a desperate existence for the poor.

Climate change or water scarcity do not directly cause conflict, but under certain conditions, they may exacerbate already existing drivers of conflict, such as a previous history of conflict, high dependence on agriculture, and the erosion of livelihoods, coupled with weak institutions.11 Much local and little-reported unrest in the region over the past years has been linked to water scarcity, particularly where there are grievances over poor services, unemployment, and growing destitution.12 One such example is the repeated upheaval in Basra, Iraq, where people are deeply frustrated with failing local and national governance.13 There has been much debate over the role of the long drought in Syria as a factor contributing to the uprising in 2011. In the most thorough analysis to date, however, political scientist Marwa Daoudy concludes that, ultimately, political factors were more important than the climate-induced drought in causing Syria’s conflict.14 Still, current climate and environmental trends point in the wrong direction, and can be expected to get worse.

Climate change or water scarcity do not directly cause conflict, but under certain conditions, they may exacerbate already existing drivers of conflict.

Countries that have some success in dealing with environmental and climate challenges have made them political priorities that guide transformational and integrated decision-making across government departments and institutions. Key areas include reducing the use of fossil fuels, energy efficiency, transition to renewable energy, disaster risk reduction, water management, and biodiversity protection. In most cases, leading countries have been pressed or encouraged by active civil society in a space of open and constructive dialogue, domestically and with the global community, allowing development of new ideas and policy proposals.

An enabling business climate promotes renewable energy and technological innovations for sustainable consumption and production. None of these conditions prevail in the MENA region, with the exception of a few non-oil-producing countries that are faced with a water crisis of existential proportions, such as Tunisia, where climate change is inscribed in the 2014 constitution; its article 45 states that “the state guarantees the right to a healthy and balanced environment and the right to participate in the protection of the climate.”15 Morocco and Jordan also have ambitious climate and water plans, although their civil societies are more constrained than in Tunisia. Across the region, authorities view those that question the official development course from an environmental perspective as security threats.16 Journalists and media outlets that report critically on the environment face repression.17

But the region also fails to address its transboundary problems. How to manage shared surface water and aquifers needs to be agreed between neighbors within the same river basins and catchment areas, where water availability becomes more unpredictable with climate change. Several versions of an Arab Convention on Shared Water Resources were developed between 2011 and 2016 by the Arab Ministerial Water Council, with support from the United Nations Economic and Social Commission for West Asia (UNESCWA), but the convention remains in an unratified draft form.18 Decades of negotiations on the Euphrates and Tigris have not led to an agreement between the riparian hegemon Turkey and downstream Iraq and Syria. Israel still controls the availability of water to Palestinians. An atmosphere of political rivalry and conflict have kept the technical competence of MENA governments and the qualified analysis by the UN and other multilateral institutions from creating substantial policy shifts. The most recent environmental analysis by the Arab League, from 2010, calls for regional cooperation on shared challenges, but remains unimplemented.19 The intersecting conflicts of the past years, partly triggered by the Arab uprisings of 2011, have further fractured the Arab League and the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC).20 As an example, a railway link that is supposed to connect GCC states, which was announced fifteen years ago, is still incomplete.21 Even if parts have been built, there are no tracks through Qatar, since the country’s relations with Saudi Arabia and the Emirates soured in 2017.

Further, the MENA region’s environmental challenges are locked in a global setting. Its growing food imports are vulnerable to any instability in production, prices, and supply chains that could jeopardize its food security. This dependency was on full display during the global food crises in 2008 and 2010–11, which were partly triggered by climate-change-induced harvest failure in major producer countries, when sudden price shocks led to unrest in several MENA countries.22 The region is also extremely sensitive to volatility in global energy markets, again shown in the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic, when the oil market collapsed. Any effort to address the MENA region’s environmental and climate challenges and their security implications must recognize that they have local, regional, and international dimensions.

The Solutions

Solutions to the challenges listed above need to build on two premises. The first is that the MENA region consists of landscapes and seascapes—it is not only a political or administrative entity. These landscapes and seascapes stretch to include neighbors with whom relations are problematic or hostile—Ethiopia, Iran, Turkey, and Israel—and which have a strong influence on politics and security in the core of the MENA region.23 Again, political and administrative delineations do not follow the contours of landscapes, nor the natural movement of water below or above ground. The hydraulic arteries of the Middle East—the Nile, the Euphrates and the Tigris and their tributaries, the Jordan River and all the deep aquifers—bind together nations within and around the region. So do the Gulf, the Red Sea, and the Mediterranean. Effective action on the region’s nature-related challenges needs to take its landscapes and seascapes as the point of departure.

Political and administrative delineations do not follow the contours of landscapes, nor the natural movement of water below or above ground.

Second, circumstances internal to MENA states determine whether nature, the environment, and climate change become political priorities that engage citizens and governments. The question is if and how external actors—the international community—can influence relevant action. The heavy legacy of involvement from Western powers over the past century (and more recently, of Russia) will not encourage action on the difficult issues under discussion here, particularly if external actors frame them as issues of national and regional security. Authoritarian states, in particular, will be reticent to do anything that risks external intervention. Events of the past decade have shown how deep change arises out of national action, and not through external interference. As the legal scholar Noah Feldman argues, “the central political meaning of the Arab spring and its aftermath is that it featured Arabic-speaking people acting essentially on their own, as full-fledged independent makers of their own history.”24 It is unlikely that transformational action on environment and climate change by peoples and governments in the MENA region can follow any other route.

In consideration of these two premises, MENA states must pursue genuine change in ways that resonate between neighbors, across the region, and beyond. Only then can meaningful results be achieved in areas fundamental to the environment and climate change, including in those that undermine or strengthen security: policy instruments promoting sustainable development, pricing policies, public and private investments in natural, physical, social and human capital, and regulatory frameworks and legislation. It may be that such a pursuit of change can only happen as part of broader national reform processes. Consequently, reform efforts addressing insecurity, governance, post-conflict recovery, and reconstruction should also include measures to address the environment and the challenges of climate change.

With this in mind, this report suggests some approaches to guide international action; first, from a long-term and strategic perspective.

A Regional and Landscape Lens

External actors need to see their relations with individual MENA countries through a regional lens, recognizing that none of them is autonomous when it comes to the control and use of water and other natural resources. The fact that MENA regional organizations, primarily the Arab League, have been unable to forcefully take on such strategic issues makes it even more important that external actors do not further contribute to regional fragmentation, but act in recognition of the region’s innate interconnectedness. Few advanced economies have a regional approach to the MENA region. Rather, they tend to engage with individual countries on the basis of their own security or counterterrorism strategies. The UN and the World Bank should collaborate more, establishing closer links between their different country missions and programs. UNESCWA, the UN regional body in Beirut, is an important venue for analysis and regional dialogue, as are World Bank regional meetings. Through a joined-up strategic approach, building on the network of UN and World Bank country offices, the two multilateral organizations would be able to simultaneously support individual MENA countries, including in their neighborly relations, and regional organizations in addressing transboundary problems.

Nature and Security Are Interlinked

Any external engagement must accept that the region’s environmental challenges have a security dimension that has to guide analysis and implementation of policies and programs.25 Simultaneously, addressing its insecurity while ignoring the state of the environment and climate runs the risk that conflicts will be reignited through unresolved tensions around the use and management of natural resources.26 Peace agreements and stabilization programs—aiming to reduce violence, restore services, rebuild infrastructure, and enhance livelihood productivity—should thus include provisions for resolution of potential conflicts on the use of land and water, not least when refugees and the internally displaced return to their homes. Ultimately, efforts at establishing a regional security framework should be informed by and address potential conflicts around the region’s shared natural resources.

Space for Dialogue

In the short term, there are measures that will help enable a more long-term and strategic approach.

External actors should offer protected space and support dialogue between civil society representatives, and between them and governments and other stakeholders—within and between countries in the region. Inclusive dialogue should be informed by new findings and models on climate change, where knowledge evolves continuously. Such dialogue would promote proposals and models of the kind that EcoPeace Middle East has developed for Jordan, Palestine, and Israel.27 The nonprofit organization is present and well connected in all three countries, but also works with local communities across borders, and provides opportunities for Track Two diplomacy—diplomacy that occurs between unofficial, nongovernmental actors. Some Western diplomatic missions in the region and UN offices already provide such space, which others could emulate.

Stabilization and Humanitarian Support

Forced displacement and the erosion of livelihoods in conflicts are destabilizing factors that work against recovery and may perpetuate instability, thus preventing countries and communities from addressing environmental and climate change effects that will become increasingly serious. Stabilization and humanitarian programs should ensure that the livelihoods of those displaced are protected and support sustainable return and recovery, and that humanitarian funding is upheld at levels that meet the needs of vulnerable populations. Special consideration is needed to develop or maintain social safety nets and protection systems to alleviate the burden on people subjected to sudden crises that are likely to occur more frequently, giving special priority to systems that can be quickly scaled up in times of sudden crises.

International actors need to deal with the MENA region in terms of landscapes and seascapes—rather than seeing only political borders and competing ideologies.

Climate change and environmental degradation exacerbate poverty and insecurity in the Middle East and North Africa. They are, by nature, complex problems with political and governance dimensions that can only be addressed through a systemic approach, requiring whole-of-government and regional action, within and beyond the MENA region. A regional security framework must incorporate solutions to shared climate and environmental challenges. International actors need to deal with the MENA region in terms of landscapes and seascapes—rather than seeing only political borders and competing ideologies. They also need to avoid contributing to further fragmentation, and help provide safe spaces for dialogue on contested issues between key stakeholders. Most urgent is to support nationally owned initiatives to reduce violence, restore services, and rebuild infrastructure, and prevent further deterioration of the livelihoods of those most at risk in the current, interlinked crises.

This report was written with support from the Rockefeller Brothers Fund as part of the TCF initiative “Nature and National Security in the Middle East.”

header photo: Syrian refugees gather water as they go about their daily business in the Za’atari refugee camp on January 29, 2013 in Mafraq, Jordan. Drought stressors have been posited as one factor contributing to the outbreak of the civil war in Syria. Source: Jeff J. Mitchell/Getty Images

Notes

- “Arab Sustainable Development Report,” United Nations Economic and Social Commission for West Asia (UNESCWA) 2020, https://asdr.unescwa.org/.

- Measured as freshwater withdrawn in proportion to available water.

- “Beyond Scarcity: Water Security in the Middle East and North Africa,” World Bank MENA Development Series, 2017, https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/27659.

- Paul Wallace and Khalid Al-Ansary, “Record Heat Sets Off a Cascade of Suffering in Baghdad,” Bloomberg, August 4, 2020, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2020-08-03/record-heat-sets-off-a-cascade-of-suffering-in-baghdad.

- Aisha Al-Sarihi and Michael Mason, “Challenges and Opportunities for Climate Policy Integration in Oil-Producing Countries: The Case of the UAE and Oman,” Climate Policy 20, no. 6 (June 2020): 1–16, https://doi.org/10.1080/14693062.2020.1781036.

- Jeremy Green, “Environmental Issues in the Middle East and North Africa,” Arab Barometer, October 2019, https://www.arabbarometer.org/wp-content/uploads/environment-10-17-19-jcg.pdf.

- UNESCWA, “Arab Sustainable Development Report,” 182 .

- UNESCWA, “Arab Sustainable Development Report,” 146.

- Rami G. Khoury, “How Poverty and Inequality are Devastating the Middle East,” Carnegie Corporation of New York, September 12, 2019, https://www.carnegie.org/topics/topic-articles/arab-region-transitions/why-mass-poverty-so-dangerous-middle-east/.

- UNESCWA, “Arab Sustainable Development Report,” 14.

- Vally Koubi, “Climate Change and Conflict,” Annual Review of Political Science 22 (2019): 343–60.

- Haim Malka, “Water Pressure: Water, Protest, and State Legitimacy in the Maghreb,” Center for Strategic and International Studies, June 15, 2018, https://www.csis.org/analysis/water-pressure-water-protest-and-state-legitimacy-maghreb-0.

- Tobias von Lossow, “More than Infrastructures: Water Challenges in Iraq,” Netherlands Institute of International Relations Clingendael Policy Brief, July 2018, https://www.clingendael.org/publication/more-infrastructures-water-challenges-iraq.

- Marwa Daoudy, The Origins of the Syrian Conflict: Climate Change and Human Security (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2020).

- “Tunisia’s Constitution of 2014” (a translation of the Tunisian constitution), Constitute, 2014, https://www.constituteproject.org/constitution/Tunisia_2014.pdf.

- Jeannie Sowers, “Environmental Activism in the Middle East and North Africa,” in Environmental Politics in the Middle East, ed. Harry Verhoeven (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2018): 27–52; Peter Schwartzstein, “The Middle East’s Authoritarians Have Come for Conservationists,” The Atlantic, March 30, 2019, https://www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2019/03/middle-east-north-africa-environmentalism-espionage/585973/.

- Peter Schwartzstein, “The Authoritarian War on Environmental Journalism,” The Century Foundation, July 7, 2020, https://tcf.org/content/report/authoritarian-war-environmental-journalism/.

- “Overview of Shared Water Resources Management in the Arab Region for Informing Progress on SDG 6.5,” UNESCWA, January 3, 2018, https://www.unescwa.org/sites/www.unescwa.org/files/page_attachments/technical_paper.13-_shared_water.pdf.

- “Environment Outlook for the Arab Region,” United Nations Environment Programme, 2010, https://www.unenvironment.org/resources/report/environment-outlook-arab-region-environment-development-and-human-well-being.

- Joost Hiltermann, “Tackling the MENA Region’s Intersecting Conflicts,” International Crisis Group, February 13, 2018, https://www.crisisgroup.org/middle-east-north-africa/eastern-mediterranean/syria/tackling-mena-regions-intersecting-conflicts.

- Sebastian Castelier, “GCC Railway: A Train across a Fractured Gulf?” Al-Monitor, July 27, 2020, https://www.al-monitor.com/pulse/originals/2020/07/gcc-railway-train-fractured-gulf-qatar-saudi-arabia-uae.html.

- Johan Schaar, “Weaving the Net: Climate Change, Complex Crises and Household Resilience,” World Resources Institute Issue Brief, November 2013, https://www.wri.org/publication/weaving-net.

- In the case of tensions between Ethiopia, Sudan, and Egypt over the impact of the Great Renaissance Dam in Ethiopia on the flow of the Nile, the three countries have benefited from all being members of the African Union, which has a stronger record than the Arab League on mediation and conflict resolution—even if the crisis is still unresolved.

- Noah Feldman, The Arab Winter: A Tragedy (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2020), xii.

- Johan Schaar, “ A Confluence of Crises: On Water, Climate and Security in the Middle East and North Africa,” SIPRI Insight, no. 2019/4, July 2019, https://www.sipri.org/sites/default/files/2019-07/sipriinsight1907_0.pdf.

- Nature and security in the MENA region are still often treated in silos. As an example, there is no reference to climate change in a recent report on the findings of a joint Brookings–World Bank project on human development and security in the region. See Tamara Cofman Wittes, Joseph Saba, and Kevin Huggard, “Stabilization and Human Development in a Disordered Middle East and North Africa,” Brookings, June 2020, https://www.brookings.edu/research/stabilization-and-development-in-a-disordered-middle-east-and-north-africa/.

- Inga Carry et al., “Climate Change, Water Security, and National Security for Jordan, Palestine, and Israel,” EcoPeace Middle East, January 2019, https://ecopeaceme.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/climate-change-web.pdf.