This report is the first in a TCF series—The Cycle of Scandal at For-Profit Colleges—examining the troubled history of for-profit higher education, from the problems that plagued the post-World War II GI Bill to the reform efforts undertaken by the George H. W. Bush administration.

The 1944 GI Bill is rightly remembered as one of the most effective social policy programs in U.S. history. Thanks to the GI Bill, millions of soldiers returning from World War II had the opportunity to enroll in college or job-training programs, and had access low-interest loans to buy homes. What has been largely forgotten, however, is that the GI Bill also led to systematic abuses at for-profit schools—schools that sprang up to take advantage of what was essentially a government educational voucher with no strings attached.

Congress and the Truman and Eisenhower administrations soon realized that strings were needed.

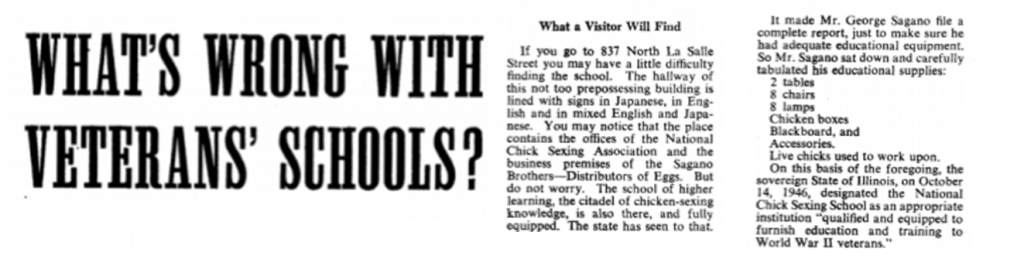

Treating the Veterans Administration (VA) as their primary funder, opportunistic entrepreneurs established schools and set their tuition rates at the maximum amount that the VA would pay. Many schools falsified their expenditure data and attendance records, overcharged for supplies, and billed the VA for students who were not even enrolled, all in order to tap taxpayers for every penny they could get. While the GI Bill helped millions of returning veterans go to college, it also fed an explosion of misleading advertising, predatory recruitment practices, sub-standard training, and outright fraud in for-profit education. Tens of thousands of veterans were trained for jobs in overcrowded fields in which there were no actual job openings.1

Sadly, veterans were sometimes complicit in these abuses. In one scam, veterans would enroll in TV repair courses, and then drop out as soon as they got the free television that came with enrollment.2 Since there were no loans involved, if a veteran got a few classes and a TV out of the GI Bill, it was at no cost to him; he had no reason to care—and often was unaware—that the taxpayer paid a high price. School owners, meanwhile, also had no accountability to taxpayers, running a federally funded school that was a surefire business proposition. In the five years that followed President Roosevelt’s signing of the GI Bill, the total number of for-profit schools in the United States tripled,3 even while thousands closed.4 More veterans actually used their educational benefits under the GI bill to attend for-profit vocational schools than to enroll at public and nonprofit colleges.5

It did not take long before newspaper and magazine exposés about unscrupulous trade school owners and deceived veterans started popping up all over the country. The Saturday Evening Post ran a piece in 1946 titled “Are We Making a Bum Out of GI Joe?” Other newspapers and magazines ran stories with headlines like “How Many Wrongs Make a GI Bill of Rights?” and “There’s a Shell Game at Every Turn for a Man with an Eagle on His Lapel.”6 Associated Press reporter Rowland Evans, who would soon team up with Robert Novak to write a long-running conservative syndicated opinion column, reported in 1949 that the VA wanted “curbs on the enrollment of veterans in fly-by-night ‘proprietary’ schools… If this isn’t done, ‘taxpayers are to be bled white,’ says H. V. Stirling, the man who runs the vast GI Bill Education program.”7

Congress Takes Notice of GI Bill Abuse

In 1949, Senator Elbert Thomas (D-UT), chairman of the Senate Committee on Labor and Public Welfare, asked Carl Gray, the VA administrator, to prepare a report on education and training under the GI Bill. Gray’s 200-page report, released in January 1950, was a sharp indictment of the for-profit industry.8 The Gray Report found that, of the 1,237 schools identified by the VA under the GI Bill as being involved with some irregularity or questionable practices, 963 schools were for-profit institutions. Of the 329 schools that had lost their accreditation, 299 of the schools, more than 90 percent, were for-profit schools.9

President Truman’s response to the Gray Report was swift and pointed. In a Special Message to Congress, Truman stated that “in a good many instances veterans have been trained for occupations for which they are not suited or for occupations in which they will be unable to find jobs when they finish their training . . . each time a course of trade and vocational training does not contribute in a substantial way to the occupational readjustment of a veteran, it constitutes a failure. . . . Such failure is costly to the veteran, to his family, and to the Nation.”10 It was necessary, Truman said, that steps “be taken to give greater assurance that every trade and vocational course under the [GI Bill] will provide a good quality training and will in each instance help a veteran to complete his occupational readjustment and find satisfactory employment.”

Congress passed a joint resolution in 1950 launching the House Select Committee to Investigate Educational, Training, and Loan Guaranty Programs under the GI Bill, a thirteen-month effort. The committee’s files of hearings, commissioned reports, and case files on 258 proprietary (for-profit) schools measured twenty-five feet long stacked side by side, and resulted in a 222-page committee report in February 1952. The congressional committee also commissioned the General Accounting Office (GAO, now referred to as the Government Accountability Office) to survey veterans training programs in six states. The GAO concluded that newer proprietary schools were using “promotional plans and extensive advertising campaigns, which were often misleading and laden with extravagant, unjustifiable claims . . . conducted for the express purpose of attracting veterans.”11

The February 1952 report of the House select committee concluded that many for-profit schools “offered training of doubtful quality” in fields where little or no employment opportunities existed.12 Pointing to the approximately fifty court cases in which schools and their executives had been convicted of fraud and abuse, as well as ninety similar pending cases, the report stated that “exploitation by private schools has been widespread” and that there was “no doubt that hundreds of millions of dollars [had] been frittered away on worthless training.”13 “Under the policies of the Veterans’ Administration,” the committee concluded, new for-profit “schools were allowed to virtually write their own charges against the Treasurer of the United States without regard to the amount, type, and quality of service rendered.”14

The chairman of the House select committee was Olin “Tiger” Teague, a no-nonsense Democrat from Texas who would go on to earn the title of “Mr. Veteran” for his decades-long domination of veterans policy as chairman of the House Committee on Veterans’ Affairs. Teague was a fiscal conservative and Southern Democrat who later opposed much of Great Society initiatives of the 1960s (today, he almost certainly would have been a member of the Republican Party). In World War II, Teague lost most of his left foot to enemy gunfire and won three Silver Stars, three Bronze Stars, and Three Purple Hearts. He believed that generous educational benefits should be reserved for wounded veterans, and strictly limited for service members who served in peacetime. During the next two decades, he fiercely opposed efforts, led by fellow Democrats, to expand educational benefits for GIs who did not see combat.15

Teague, with the full support of the Truman administration and later the Eisenhower administration, led a bipartisan crackdown on for-profit schools. In 1948, Congress banned the use of GI educational benefits for hobby or recreational courses. Two years later, representatives authorized the VA to deny access to for-profit schools that had been in existence for less than a year, to impose restrictions on those where fewer than one-fourth of enrolled students paid their own tuition, and to prohibit the expansion of programs that would not likely lead to a job.16

For Teague, the 1950 legislation was only the start of a bipartisan crackdown on for-profit schools. The original GI Bill of Rights for World War II veterans was drawing to an end, and by 1952 Congress and the nation were debating how to extend educational benefits to GIs during the Korean conflict. The 1952 Korean GI Bill, which passed the House by a vote of 361 to 1,17 included the first “85–15” rule aimed solely at for-profit schools. Under the 85–15 rule, the VA was barred from approving and paying for non-accredited, non-degree courses for veterans at proprietary schools if more than 85 percent of students were veterans.18 (The Teague select committee had recommended a higher eligibility threshold at for-profits of a minimum of 25 percent enrollment of non-veterans.)

Teague’s biggest triumph was to kill off the proprietary schools’ golden goose: direct tuition payments from the federal government. Instead of making tuition payments to schools, the 1952 Korean GI Bill had the VA make monthly payments to veterans, out of which the veteran had to cover not only the costs of tuition, but also books, supplies, fees, and other living expenses related to their education and training.19 With the elimination of easy access to direct tuition payments, and the introduction of competitive funding needs of veterans, the for-profit sector stopped expanding almost overnight. In ensuing decades, Teague would successfully beat back three efforts in Congress—led by Democrats—to renew direct tuition payments.20 In 1972, twenty years after the passage of the 1952 Korean GI Bill, Senator Strom Thurmond (R-SC) would tell an advocate of restoring direct payments to schools: “That was tried . . . in 1944, and it was on the books until 1951, and there were so many abuses that it had to be changed to the present system of just allotting so much for a student.”21

The issues that Congress grappled with in 1952 are, in many respects, the same struggles that today’s lawmakers are having: given the financial incentives that for-profit school owners have to enroll as many students as possible and to spend as little as possible on their education, how can government aid be designed so that it encourages enrollment of qualified students in quality career-training programs? A new strategy included in the 1952 legislation was to involve private accrediting agencies, which colleges themselves had created years before as a voluntary system of quality assurance through peer review.

Accrediting Agencies as Arbiters of Quality

Beginning with the 1952 Korean GI Bill, and repeated in dozens of subsequent federal student aid statutes, Congress required the U.S. commissioner of education, then the nation’s top-ranking federal education official, to publish a list of agencies and associations deemed to be “reliable authorities” on the quality of training offered by an educational institution. The approving agencies in each state and the VA could, in turn, rely on the judgments of these private groups to determine which institutions were worthy of federal aid.22

With the explosive growth of for-profit schools, the VA was overwhelmed and understaffed when it came to processing veterans’ educational benefits, as well as monitoring and enforcing regulations. States, likewise, had been similarly unprepared for the flood of schools and programs unleashed by the 1944 GI Bill.23 Deferring to accrediting agencies seemed like a convenient, low-cost solution that kept the government out of the business of directly setting quality standards.

The U.S. Office of Education, however, was not in a position to undertake a detailed review of accrediting agencies to determine which ones could be deemed reliable authorities on academic quality. So the commissioner of education, Earl McGrath, decided to simply publish the list of accrediting bodies then listed in the Office of Education’s directory, which at the time omitted several fledgling accrediting associations for proprietary trade schools. McGrath reportedly feared that including these might open the door to diploma mills, along with legitimate trade schools. It was not until the late 1950s that the trade schools’ accrediting agencies were added to the Office of Education’s list of recognized authorities.24

Federal reliance on accreditors was an awkward fit from the start, and is still controversial today, especially as it relates to for-profit schools. As Terrel Bell, the U.S. commissioner of education in the Nixon and Ford administrations and Ronald Reagan’s first secretary of education, later summed up: “Some of the associations were creatures of the owners, and their policies were established in a self-serving way, so that the institutions could qualify for federal assistance.”25 Chester Finn, a Reagan administration appointee, has observed that accreditation operated like a “private club competent to pass on its own candidates for membership but scarcely equipped to police their handling of the government’s money and certainly not designed to regulate profit-seeking institutions that reject many of its norms.”26

A General Becomes President

After the Korean War ended in July 1953, the issue of how to provide educational benefits and pensions to those serving in peacetime took on new urgency. In January 1955, President Dwight Eisenhower established a Commission on Veterans’ Pensions to study the issue, appointing his friend, the famed General Omar Bradley, as chairman of the presidential commission. The central recommendation of the April 1956 Bradley Commission Report was that while peacetime soldiers should continue to receive medical care and employment assistance, their “military service does not involve sufficient interruption to the educational progress of servicemen to warrant a continuation of a special educational program for them.” In times of war or peace, the commission declared, military service “is an obligation of citizenship and should not be considered inherently a basis of future Government benefits.”27

The Bradley Commission Report’s recommendations squarely matched up with Eisenhower’s beliefs—and over the next four years, Eisenhower teamed up with Congressman Teague to successfully block bills by Senate Democrats to provide generous educational benefits to Cold War veterans. In his final budget message to Congress, Eisenhower warned that providing education benefits for peacetime soldiers could undermine the services’ efforts to retain career servicemen by encouraging soldiers to leave the military to attend college. Education benefits, Eisenhower said, “cannot be justified by conditions of military service and are inconsistent with the incentives which have been provided to make military service an attractive career for capable individuals.”28

The Bradley Commission Report also included a damaging analysis of for-profit schools. In the wake of increased educational benefits for veterans, the Commission found “thousands of new proprietary schools were established” and, at these institutions, “many veterans enrolled in courses leading to occupational fields where the employment prospects were far from good.”29 The Commission had no reliable information “on the number of veterans graduated from profit schools who were actually placed in jobs for which they were trained, but it was estimated in January 1951 that of the 1,677,000 veterans who attended profit schools only 20 percent completed their courses” and that “much of the training in profit schools was of poor quality.”30 Furthermore, the government “was overcharged for much of the training in schools below college level, particularly in profit schools.31 Soon, the Eisenhower administration launched the first federal effort to list and shame “diploma mills”—correspondence schools that awarded “degrees” by mail without requiring students to meet real educational standards.32

While Eisenhower staunchly opposed providing generous educational benefits to veterans who had served in peacetime, he was not opposed to expanding federal support for students more generally to go to four-year colleges and universities to study science, math, engineering, and foreign languages. In October 1957, the Soviet launch of the Sputnik I satellite precipitated a round of national soul-searching, both about whether the Soviet Union had outdistanced the United States in the space race and if American students were lagging behind their Soviet counterparts. In January 1958, Eisenhower proposed to Congress that it create a four-year “emergency” program to strengthen national security that would include a program of 40,000 federal scholarships for low-income students to go to college, with scholarships earmarked for students with good preparation or high aptitude in science and mathematics.33

Eight months after Eisenhower made his proposal, he signed into law the National Defense Education Act, which created the National Defense Student Loan (NDSL) Program, the first federal student loan program to provide direct loans capitalized with funds from the U.S. Treasury. Funds for the loan program were given to schools, which were then tasked with distributing the dollars to students with financial need in the form of low-interest loans with an emphasis on improving science, mathematics, engineering, and foreign language preparation. In the aftermath of the proprietary school scandals of the GI Bill, Eisenhower and Congress limited the funding to public and nonprofit colleges.34 The better part of a decade would pass before Congress, at the behest of a Democratic administration, would open the door to using federal student loans at for-profit schools. When Congressman William Ford (D-MI), the future chairman of the House Education and Labor Committee, arrived in Washington after being elected in 1964, he found that Congress was still “broiling with anger” about the misuse of federal student aid dollars. The anger, Ford recalled, “remained from the period of the much-publicized abuses of the GI bill.”35

Timeline of For-Profit Higher Education

Scroll through the below timeline to view the history of for-profit higher education.

Notes

- See the findings of the House Select Committee to Investigate Educational, Training, and Loan Guaranty Programs Under the GI Bill, House of Representatives, 82nd Cong., 2nd sess. February 1952, p. 3. Hereafter referred to as the “Teague Report.”

- In 1949, 546,000 veterans made course changes, roughly twenty times as many veterans who made courses changes in 1946 (26,000). James Bowman et al., “Educational Assistance to Veterans: A Comparative Study of Three GI Bills,” Educational Testing Service, September 1973, reprinted in Final Report on Educational Assistance to Veterans: A Comparative Study of Three G.I. Bills, Committee on Veterans’ Affairs, U.S. Senate, Senate Committee Print No. 18, September 20, 1973, 93rd Cong., 1st sess., 171.

- The Teague Report, 12.

- By some accounts, at least 9,000 proprietary schools and as many as 13,000 proprietary schools participated, however briefly, in the training of veterans in the five years after the signing of the GI Bill. See the testimony of Harold Orlans, a researcher at the National Academy of Public Administration Foundation, in Proprietary Vocational Schools, Special Studies Subcommittee of the House Committee on Government Operations, 93rd Cong., 2nd Sess, July 1974, 56. The January 1950 Gray Report by Carl Gray, the VA Administrator, reported that there were more than 7,500 for-profit institutions on VA approval lists in 1949. Cited in A.J. Angulo, Diploma Mills (Baltimore, Md.: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2016), 64.

- While 2.2 million vets went to four-year colleges on the GI Bill, more than three million GIs used their educational benefits to enroll in trade and technical and business schools (2.4 million vets), with another 637,000 veterans taking correspondence courses. Teague Report, 92.

- Bowman et. al, Final Report on Educational Assistance to Veterans, 114.

- Rowland Evans Jr., “VA Would Check Some GI Schools,” Washington Post, August 21, 1949.

- A. J. Angulo, Diploma Mills, 63–65.

- Paul Starr, The Discarded Army: Veterans after Vietnam (New York: Charterhouse, 1973), 236.

- “Special Message to the Congress Transmitting Report on the Training of Veterans Under the Servicemen’s Readjustment Act,” February 13, 1950, Public Papers of the Presidents, Harry S. Truman, 1945–1953. Available at the Harry S. Truman Library & Museum, The American Presidency Project, http://www.trumanlibrary.org/publicpapers/index.php?pid=656.

- Quoted in Teague Report, February 1952, 30.

- Ibid, 3, 12.

- Ibid, 3, 12.

- Ibid, 30.

- See Mark Bolton, Failing Our Veterans: The G.I. Bill and the Vietnam Generation (New York: New York University Press, 2014), 35–42, 60–103.

- Barbara McClure, “Veterans’ Education Assistance Programs,” Congressional Research Service, 86-537 EPW, January 31, 1986, 8. The bill prohibited GI Bill payments for new courses at for-profit schools if state agency responsible for overseeing GI Bill schools determined that the occupation for which the course was intended to provide training was crowded in the State and that existing training facilities were adequate.

- Bolton, Failing Our Veterans, 42.

- Barbara McClure, “Veterans’ Educational Assistance Programs,” 11.

- Ibid. Also see The Teague Report, 1.

- Tim O’Brien, “The Battle of the GI Bill: Sen. Hartke v. Rep. Teague,” Washington Post, July 21, 1974, C4.

- Educational Benefits Available for Returning Vietnam Era Veterans, Hearings on S.2161 and Related Bills, Part I, Subcommittee on Readjustment, Education, and Employment, Senate Committee on Veterans’ Affairs, 92nd Cong., 2nd Sess., March 29, 1972, 485.

- Bowman et al., Educational Assistance to Veterans, 177.

- “Many State departments of education were not adequately staffed in 1944 to perform the regular functions assigned to them by State law, not to mention the new functions assigned to them by [the G.I. Bill]. Standards for the approval of institutions and establishments varied widely in 1944 and in some States were practically nonexistent.” Veterans’ Benefits in the United States, The President’s Commission on Veterans’ Pensions, Volume III, Staff Report No. IX-B, 1956: “Readjustment Benefits: Education and Training, and Employment and Unemployment,” 19.

- Charles M. Chambers, “Federal Government and Accreditation,” in Understanding Accreditation: Contemporary Perspectives on Issues and Practices in Evaluating Educational Quality, ed. Kenneth E. Young, Charles M. Chambers, H. R. Kells and Associates (London: Jossey-Bass, 1983), 243–44.

- Terrel H. Bell, “The Federal Imprint,” External Influences on the Curriculum: New Directions for Community Colleges 64 (Winter 1988), 12.

- Chester E. Finn, Jr., “In Washington We Trust, Federalism and the Universities: The Balance Shifts,” Change 7, no. 10 (Winter 1975/1976): 29.

- The President’s Commission on Veterans’ Benefits, “Veterans’ Benefits in the United States,” April 1956, 10. Available at the Veterans Law Library, http://www.veteranslawlibrary.com/files/Commission_Reports/Bradley_Commission_Report1956.pdf.

- President Dwight D. Eisenhower, “Annual Budget Message to Congress: Fiscal Year 1962,” January 16, 1961, Public Papers of the Presidents, The American Presidency Project.

- “Veterans’ Benefits in the United States,” 296.

- Ibid 296-297.

- Ibid 291.

- In October 1959, Arthur Flemming, the secretary of health, education, and welfare,warned of the evils of degree mills at a press conference and charged the U.S. commissioner of education with preparing a list of degree mills for public release at a subsequent press conference The preliminary list, released by the U.S. Office of Education in April 1960, named more than thirty organizations as degree mills. See “Pollution in Higher Education: Efforts of the U.S. Office of Education in Relation to Degree Mills,” Bureau of Postsecondary Education, U.S. Department of Health, Education, and Welfare, March 1974, 3.

- President Dwight D. Eisenhower, “Special Message to Congress on Education,” January 27, 1958, Public Papers of the Presidents, The American Presidency Project.

- Robert Shireman, “The Covert For-Profit: How College Owners Escape Oversight through a Regulatory Blind Spot,” The Century Foundation, October 6, 2015, 4, https://tcf.org/content/report/covert-for-profit/.

- Hearings on the Reauthorization of The Higher Education Act of 1965: Program Integrity, House Committee on Education and Labor, Subcommittee on Postsecondary Education, 102nd Cong., 1st Sess., Serial No. 102-39, May 30, 1991, 427.