The widening fallout from October 7 is upending the Middle East in horrible ways, some new and some familiar. The Houthis have discovered their power to disrupt international shipping. Militia factions allied with Iran have crossed old red lines in their daily attacks on U.S. bases. The United States has shown itself unable to restrain the conduct of its principal regional ally, Israel, and is now facing an era of diminished influence and overextended entanglements. Meanwhile, the Middle East poly-crisis is more acute than ever. Across the region there’s hardly any prospect for effective governance or a modicum of civil rights.

Policymakers might still be resorting to outdated frameworks, but reality has moved on. The Middle East has entered a new phase, no matter how the regional war progresses and what shifts occur in Palestine–Israel relations. In this roundtable, the second of two (the first focused on the crisis in Gaza), Century International fellows address some of the long-tail crises and emergencies triggered by October 7 and the war in Gaza.

Syria on a Precipice

Syria on a Precipice

Aron Lund

Regional events since October 7 have been so brutal and so unprecedented—with the daily carnage in Gaza, constant violence on the Israel–Lebanon border, and conflict in the Red Sea—that Syria has nearly slid out of the spotlight entirely. Though the war in Syria churns on in a way, front lines have remained frozen since 2020, offering little of interest for a media and policy scene drawn to action, war, and gore.

Yet Syria is part of the regional crisis—intimately so. President Bashar al-Assad’s government keeps its head down, but it offers strategic depth and facilitates Iranian logistics that let Hezbollah hold Israel’s northern front at risk. Israel stepped up air strikes inside Syria, but the Syrian–Iranian pact seems as firm as ever.

The war-torn country also serves as a proxy battlefield. Iran-backed factions strike U.S. bases in the northeast and on the Syria–Jordan border to pressure the Americans to rein in Israel in Gaza. The Biden administration has hit back at times, including with a wave of heavy airstrikes on February 3 to avenge the killing of three U.S. soldiers. But all involved realize that the fight isn’t over positions in Syria—it’s about U.S. policy in Gaza.

That’s not to say Syrian territory can’t come into play. It seems out of the question that Biden would pull U.S. troops from Syria to appease Iran, but his hand could be forced by events in Iraq. U.S. bases there face the same kind of Iran-inspired attacks, and Tehran’s local allies benefit from surging anti-American sentiment—prompted by the U.S. role in crushing Gaza—as they try to engineer the ouster of the United States by political means. Should U.S. forces be shown the door in Iraq, the deployment in northeastern Syria would be left hanging, without safe exit or supplies. That could be the end of Washington’s on-the-ground role, potentially enticing Damascus or Ankara (or both) to swoop in and seize the area—which could get messy.

Yet in the longer term, what may affect Syria most is neither the fighting nor the tug of war over U.S. troops, but the economic damage wrought by today’s turmoil.

The Houthi chokehold on the Red Sea is reportedly already driving up prices in Damascus and the region’s economy is in serious trouble. That harms Syria, too, and it can ill afford it after several years in economic free fall. A recent World Food Programme (WFP) assessment notes that the cost of living in Syria quadrupled over two years, while salaries stayed unchanged: “A family earning a minimum wage today can only afford one tenth of its monthly essential needs.”

It’s only going to get worse. There seems to be no hope of either meaningful sanctions relief, a boost in trade, or increased aid. On the contrary, donor governments began to cut spending on Syria even before the Gaza war, in part to shift money to Ukraine. Over autumn and winter, WFP ended a food distribution scheme that had sustained some five million Syrians. Now, the immense destruction in Gaza will further sap aid budgets, adding to Syria’s slow-rolling socioeconomic implosion.

For Syrians, emigration is now the only escape, but no country wants to take them. Sooner or later, their spiraling despair will produce its own politics, potentially rupturing the status quo that has reigned since 2020—and then, finally, the world will notice.

U.S. Plan to Stay in Iraq and Syria in Danger

U.S. Plan to Stay in Iraq and Syria in Danger

Sajad Jiyad

As the Gaza war has spiraled into regional conflict, U.S. bases have come under daily attack in Iraq and Syria, and the United States has struck militant targets in Iraq without the Iraqi government’s permission, triggering a crisis in relations. Baghdad and Washington started a new round of strategic negotiations in January, and will need to resolve the question of whether there will be a long-term American military presence.

The United States believes it can only effectively push back against Iranian influence in Iraq and deter complete Iranian hegemony if it maintains a significant military force presence. That is the focus of the current U.S. mission—it has long moved on from being an anti-Islamic State mission.

Meanwhile, Iran is determined to push U.S. troops out of Iraq as soon as possible, with a longer-term goal of vastly reduced U.S. presence near Iran’s borders and across the Middle East. To this end, Iran’s aim is a slow grind with U.S. forces constantly targeted and in danger—an attritional campaign that does not escalate to a major conflict.

The United States views a withdrawal as effectively ceding Iraq completely to Iran, an unacceptable outcome. But apart from a stubborn military presence that is under regular attack, Washington has not crystallized an alternative method to forestall that scenario. The United States knows the Iraqi government is not able to offer protection to troops stationed there, yet it does not want to be pushed out by Iranian-backed groups, and certainly not under fire. Washington is unsure if it can keep troops in Iraq against Baghdad’s wishes, even by coercion, but it also does not have any better options than the status quo.

Fighting ISIS without U.S. Bases

Fighting ISIS without U.S. Bases

Sam Heller

It’s worth returning to this point by Sajad: countering the Islamic State can no longer really justify keeping American troops in Syria and Iraq.

U.S. deployments in Iraq and Syria are linked. My understanding has been that U.S. forces in Syria rely on the U.S. presence in neighboring Iraq for logistics, and that an American withdrawal from Iraq would make the U.S. presence in Syria untenable.

ISIS has been reduced to insurgent cells, guerrilla bands, and desert marauders—not enough to warrant a large U.S. presence.

But what’s really left of the Islamic State, ostensibly the basis for the U.S. military presence in both Iraq and Syria? The organization certainly persists in both countries, whether as underground insurgent cells carrying out assassinations and bombings; as guerrilla bands camped in rugged terrain; or, in areas where it has a little more operational space, as roving desert marauders. But the Islamic State’s real presence also seems to be consistently exaggerated, typically to political ends. In fact, the organization appears much diminished. And I no longer believe that the United States needs to be in Iraq and Syria to keep the organization down. At this point, the Islamic State seems like a problem that can be managed by local actors, without direct U.S. involvement.

There are other valid, non-Islamic State arguments for why the United States ought to stay in Iraq and Syria, including the risk that a U.S. exit from Syria could invite an outside attack on America’s local Syrian partners. But there are also good reasons to go. In both countries, U.S. forces are an easy target for Iran-linked actors when they want to pressure the United States or retaliate for Israeli actions. In Iraq, the United States’ periodic shootouts with paramilitaries mean the U.S. presence is a destabilizing factor for the country. And in Syria, the United States is presiding over a sub-state project in the country’s northeast that is getting increasingly wobbly. Washington seems unwilling or unable to stop Turkey from picking off America’s local Kurdish partners with drone strikes, or to economically stabilize the local administration. So how much longer is the United States going to stay, as things get steadily worse? Certainly the Islamic State doesn’t seem like a good reason to hang around.

America’s Shrinking Counterterror Footprint

America’s Shrinking Counterterror Footprint

Thanassis Cambanis

At some point in the near future, it’s inevitable that the United States will withdraw from northeast Syria and reduce its forces in Iraq. President Biden doesn’t really want the regional war that he’s stumbled into, and Donald Trump, if he returns to office, is determined to make good on his 2019 effort to end the U.S. military mission in Syria.

Fewer U.S. bases means less risk of an accidental escalation with Iran, and fewer vulnerable U.S. targets for Resistance Axis militias. But it leaves the problem of how to best keep an eye on the Islamic State and prevent its revival. Washington has shrinking leverage. It can’t force the Assad regime to act responsibly; nor can the United States protect its preferred Syrian partner, the Kurdish-led Syrian Democratic Forces, once it withdraws.

That leaves a mixed bag of options. The United States is likely to negotiate a useful ongoing partnership with Iraq to share intelligence, monitor, and strike the Islamic State. The United States enjoys deep support in Iraq’s Kurdistan Regional Government, and reliable allies within the federal security organs in Baghdad. The United States will be able to collaborate with Iraq, but not dictate—and it certainly can’t maintain a strategic partnership with the Iraqi state if America is actively at war with some of the factions that form the government.

Syria is more complicated. Washington will lose its partner, and will have to work through the Iraqis to induce Assad to control the Islamic State. Damascus has its own interests in preventing an Islamic State resurgence, and will probably be willing to take over security at the al-Hol camp, where 50,000 women and children live, along with the detention centers in al-Hasakeh and environs that hold thousands of suspected Islamic State fighters. But the United States will have to admit the limits of its reach and operate with diminished influence in Syria and Iraq.

Egypt Is Going Broke

Egypt Is Going Broke

Ashraf Hassan

Egypt’s financial straits make it vulnerable to pressure—for instance, reports keep surfacing that Egypt might be induced to admit refugees from Gaza in exchange for an international bailout. And the Gaza war has severely strained an Egyptian economy already stretched to a breaking point.

Red Sea disruptions, in particular, are only going to make things worse for Egypt in both the short and medium terms. Revenues from the Suez Canal are one of Egypt’s very few sources of foreign revenues. Just in January, the Canal’s revenues were down by 40 percent, putting further pressure on the Egyptian pound, which had already lost more than half of its value in less than a year. In the medium term, these disruptions could lead to more inflation in a country already battered by rising prices—food prices increased at an annual rate of almost 70 percent in 2023. The Red Sea disruptions are already driving shipping and energy prices up, and further increasing the price of goods that Egypt is dependent on, such as wheat.

With the Gulf unwilling to bail out Egypt and the IMF reluctant to provide loans to a regime that has consistently evaded economic reforms, it is definitely crucial for Egypt that calm is restored to the Red Sea.

And while the war is exacerbating Egypt’s economic woes, the Gaza crisis has offered a lifeline to Abdel Fattah el-Sisi’s authoritarian regime. Prior to October 7, this regime was at its weakest since Sisi came to power. Egypt’s unprecedented economic crisis caused significant stress for the regime, with the quality of life deteriorating for all Egyptians, including Sisi’s allies. With elections scheduled for December 2023, this posed a problem for Sisi—even with a rigged voting process, the country seemed to be heading toward some kind of political reckoning. But after the October 7 attacks, Israel’s indiscriminate assault on Gaza shifted the focus of Egyptian public anger to Israel and the United States. The Egyptian government exploited this shift and galvanized its networks on traditional media and online to spread disinformation about external forces instigating instability in Egypt. One major conspiracy narrative that a network of online influencers pushed was that the economic crisis was caused by malicious foreign actors, with the implication being that Israel and the United States are responsible for Egypt’s economic woes.

Stop Looking for Gulf Bailouts

Stop Looking for Gulf Bailouts

Rohan Advani

Countries across the Middle East have long depended on Gulf money bailouts to save them from crises. Washington, too, has often relied on the monarchies of the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) to foot the bill for Middle East initiatives that the U.S. favors but won’t finance.

Recent trends and statements from finance ministers seem to suggest that “bailout diplomacy” may be coming to an end. That makes it uncertain that the GCC countries will eventually help in the expensive project of rebuilding Gaza. But they do have incentives to fund stability.

In January 2023, Saudi finance minister Mohammad Al-Jadaan said that “we used to give direct grants and deposits without strings attached and we are changing that.” While official data is hard to come by, it appears that generous and unconditional bailouts to countries such as Sudan, Egypt, Jordan, Tunisia, and Lebanon have declined over the past five years. With Gulf states more invested in realizing their own ambitious developmental plans and worried about their own coffers, the GCC may be reluctant to provide the same level of cash injections and direct bilateral assistance as before.

Nonetheless, financial diplomacy has been a critical mode of power projection and regional management for the Gulf since the 1960s. While rhetoric from Gulf states may be changing, finance as an instrument of state power is not. Recognizing that the Israel–Palestine conflict is critical to stability and regional integration, Saudi Arabia and the Emirates have made it clear that they are willing to fund Gaza’s reconstruction on the condition that Israel works toward a Palestinian state. They are reluctant to fund Gaza’s reconstruction without guarantees that those very same buildings won’t get leveled again. Whether their proposals will be accepted by the Israelis is far more uncertain, but Gulf states realize that an immediate cessation of hostilities and a political solution are urgent—something they can still underwrite.

War Menaces Lebanon

War Menaces Lebanon

Sam Heller

Another regional consequence of October 7 and Israel’s war in Gaza is the risk of major war in Lebanon.

On October 8, Hezbollah bombed Israeli-occupied territory claimed by Lebanon—in solidarity, the militant group said, with the Palestinian people and their resistance. Since then, Hezbollah and Israel have traded attacks daily, mostly in areas near the so-called Blue Line that serves as the de facto border between the two countries.

Now Israel is insisting that Hezbollah pull back from the Blue Line to permit Israelis displaced from northern communities to return. Israel has said it will allow space for the United States and others to mediate a diplomatic resolution to that effect, but otherwise it will act militarily. Unfortunately, while Hezbollah doesn’t seem categorically opposed to negotiations, it refuses to talk while the war in Gaza is ongoing. Because of that sequencing problem, then, things are stuck.

Now, war doesn’t feel particularly imminent in Beirut, even as a more limited war has been ongoing in southern Lebanon for months. But plenty of well-informed diplomats in Lebanon consider Israel’s threat of a bigger intervention in Lebanon to be credible. It’s not necessarily just some mind-game bluff.

War in Lebanon would be disastrous—it would devastate Lebanon, obviously, but Hezbollah’s retaliation would also deal major damage to Israel. War, if it happens, could also draw in the United States, however much Biden administration officials might object to Israeli action beforehand. It’s yet another reason to hope for a hostage and prisoner deal and ceasefire in Gaza, which could allow for some de-escalation on the Lebanon–Israel front.

Iran-Backed Groups Show Elastic Links

Iran-Backed Groups Show Elastic Links

Sima Ghaddar

The war in Gaza has forged a new regional mindset among Iran-backed armed groups—not only in terms of their relationship to Tehran, but also in their relationship to one another. These groups today operate along a dynamic ally–partner–proxy spectrum with Iran. However, what the October 7 attacks revealed was how, in relation to one another, they tend to oscillate between battlefield partners, political havens, separate flanks, and ideological allies. The Hezbollah–Hamas partnership is just this kind of elastic relationship.

The October 7 attacks came as a surprise not only to Tehran, but, more importantly, to Hamas’s chummiest partner, Lebanon’s Hezbollah. Since 2018, Hamas has eagerly deepened its connections to Hezbollah. As part of its political repositioning, Hamas chose Lebanon as a safe haven for the organization’s leaders and a hub for its political and security presence in the region.

After the October 7 attack, Hezbollah expressed solidarity with Hamas by opening a contained front in southern Lebanon. On November 3, 2023, Hezbollah’s secretary-general Hassan Nasrallah gave his first televised speech since Hamas’s attack. He praised Hamas’s secrecy around the operation, saying that it guaranteed its success and “did not upset anyone,” adding that the Lebanese southern front can be seen as its own “real battle” as well.

However, Hezbollah’s actions since October 7 have been a bit different from its rhetoric. It has focused on containment and carefully calibrated levels of violence, even at great expense: Hezbollah has lost more than 150 fighters, including senior commanders who have conducted and sustained campaigns and military training in Syria, Iraq, and Yemen. On January 2, 2024, Israel launched several drone strikes on the southern suburbs of Beirut, targeting and killing Saleh al-Arouri, the deputy chairman of the Hamas political bureau and one of the founders of the Qassam Brigades (Hamas’s military wing). Israeli attacks on southern Lebanon have also killed civilians and militants from other Shia political parties and Lebanese militia groups. Despite that, Hezbollah continues to adhere to a tempered, albeit strained, response.

Hezbollah’s mixed reactions speak to a relative autonomy in decision-making by each of Iran’s affiliate groups, and a changeability in strategy. The United States and its regional allies have long seen the ascendent “Axis of Resistance” as a “regional tinderbox”—a risk of conflict on one front could at any minute escalate into an all-out regional war. However, the United States and its allies would be better advised to reconceptualize the Iran-proxy portfolio, alongside the domestic particularities and dispositions of Iran’s affiliates.

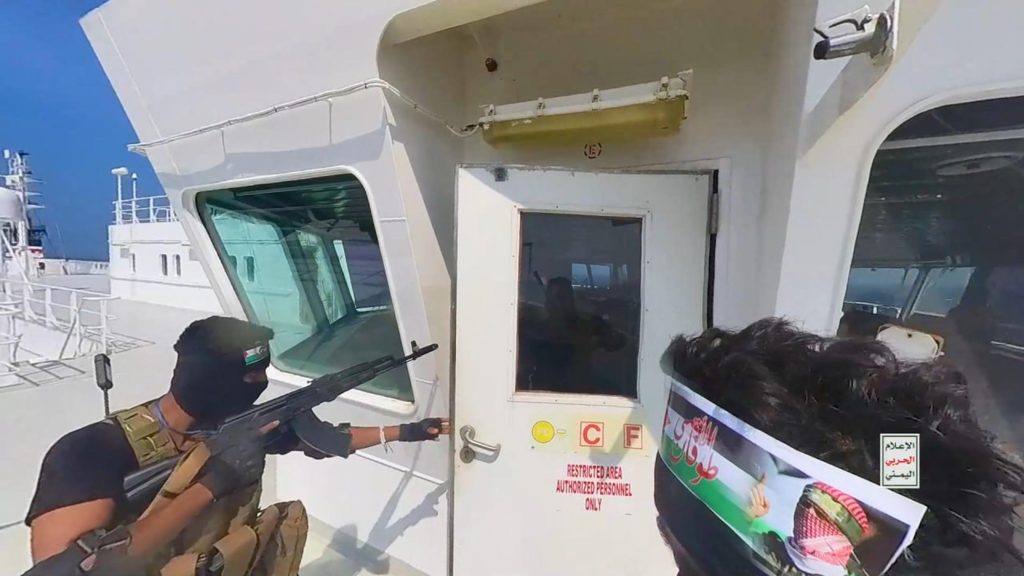

How Tight Is the Houthi Grip on Global Shipping?

How Tight Is the Houthi Grip on Global Shipping?

Rohan Advani

The Houthis have caused considerable chaos in the world of global shipping. On January 24, it was estimated that 25 percent of global shipping capacity had been diverted from the Suez Canal and the Red Sea, with global freight prices more than doubling over the month. Although the disruption affects large exporters from many parts of the world, only a U.S.-led coalition has been taking drastic military action in the region. While China and Russia called for an end to attacks on civilian ships in the Red Sea, they abstained from voting on a UN Security Council resolution that condemned the Houthi attacks. Likewise, India did not join the U.S.-led coalition, yet deployed a dozen warships east of the Red Sea to deter piracy. Although these states have an interest in keeping the Red Sea shipping lanes open, the political costs of aligning with the United States in the context of the war in Gaza may be too high to bear.

But given the scale of disruption, can the Houthis continue to use this newfound leverage, even after the war in Gaza ends? One troubling possibility is that, having discovered their power, the Houthis will find other reasons in the future to disrupt shipping and demonstrate Houthi reach. If they do, there are reasons to suggest that it will be more risky and less effective. Unable to link their operations to the indiscriminate war in Gaza, future attacks may fail to harness the same levels of domestic and regional appeal. And other states that have currently distanced themselves from the U.S.-led operation may be more reluctant to stay quiet, especially if the flow of crude oil is affected. According to a New Delhi-based think tank, the crisis could cost India more than $30 billion in exports—roughly 7 percent of the country’s total export revenue. What the Houthis have achieved thus far is undoubtedly consequential, but with a multitude of states keen on maintaining open shipping lanes, the group would do well to tread with caution.

Saudi Arabia–Israel Normalization

Saudi Arabia–Israel Normalization

Dahlia Scheindlin

Surprisingly, Hamas’s October 7 attack and Israel’s subsequent war on Gaza did not kill the idea of Saudi Arabia normalizing relations with Israel. In fact, the incentives, for both Israel and Saudi Arabia, seemed to grow. For one, the idea of a militarized, transactional, interest-based informal alliance of the Gulf countries, the United States, and Israel—with Qatar as a more independent actor—holds enduring appeal for both Jerusalem and Riyadh, as a counter to the so-called Axis of Resistance, which includes Hamas. In one reading, Hamas’s attack was an attempt to foil Saudi–Israel normalization, so moving ahead with that normalization could signal defiance of the Resistance Axis.

The idea, and plausibility of, diplomatic normalization between Israel and Saudi Arabia was effectively normalized in the summer of 2020. The Abraham Accords between Israel and four Arab countries, brokered by the United States, broke a psychological and political barrier. Israelis, and in particular Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, were keen to see the accords as a stepping stone toward the bigger prize: normalization with Riyadh.

The catastrophic war, the vast devastation in Gaza, and the severe likelihood of spillover, both to the West Bank and other countries, mean Saudi Arabia has an opportunity to “raise the price” of normalization. If in the past, Saudi Arabia would have expected some pro forma concessions from Israel to Palestinian statehood, Saudi analysts now point to a more detailed, meaningful list of steps to advance Palestinian independence, from the United States as well as from Israel. The notion seems to have gained legitimacy in Western countries, with British foreign secretary David Cameron stating that the UK might recognize Palestinian statehood—and a process to get there should be “irreversible.” Even the United States is reportedly mulling such recognition. If Saudi normalization is in the offing, and Israel’s major Western allies are charting a course in this direction, Israel becomes increasingly isolated in its defiance of the aim of Palestinian statehood.

Of course, Saudi Arabia has other aims unrelated to Israel, which could receive a boost from normalization. These include a robust security arrangement with the United States. The United States also has incentives to advance a normalization deal, since it might help push Israel toward de-escalation, without seeming to pressure Israel directly. Saudi–Israeli normalization brokered by the United States would also help Washington fend off China’s diplomatic advances in the region—Beijing has helped to advance a Saudi–Iranian dialogue or detente of some sort.

Even some Palestinians may have a reason to hope for Israeli–Saudi normalization at this point. Whereas the Abraham Accords were an attempt to bypass and isolate the Palestinians through an authoritarian alliance based solely on security interests, a future normalization could be an effective mechanism to push Israel to accept Palestinian statehood.

But such a deal is far from done. Saudi Arabia’s leadership might not be as keen to cut a deal with Israel as some observers seem to think. Riyadh might not be willing to sacrifice its valuable burgeoning dialogue with Iran in exchange for an Israel–Palestine deal that’s probably never going to win support from the Israeli government. And there’s no rush from Riyadh, which has time to wait—possibly for a new U.S. president and even more favorable terms.