Syria’s catastrophe has proceeded incrementally from horrifying to worse. Because the war has stretched on for so long, with so much foreign interference, it has become easy to miss turning points—and even to believe that little can be done to reduce the toxic consequences. In fact, much can be done to reduce the death toll, the casualties, and displacement, along with the destabilizing strategic consequences of Syria’s meltdown, which includes massive waves of refugees, terrorist blowback, and unprecedented strain on the Arab state structure.

The sixth year of a civil war that is also a sprawling, expanding regional war marks an apt time for the United States to consider a major adjustment of its Syria policy. A new U.S. president will take office in less than a year, with the opportunity—and perhaps the mandate—to do more to manage the Syria crisis. Russia, a major player in geopolitics in general and Syria specifically, has demonstrated interest in reducing tensions with the United States, while also presenting an increasingly bellicose challenge to the international order preferred by the United States and Europe. Fruitful diplomacy suggests a convergence of views to press for a political solution in Syria, but the major gaps between Washington and Moscow cannot be resolved if only Moscow is willing to bear the risks of confrontation. Finally, and most importantly, the human and strategic toll of the Syrian war is no longer tolerable. The collapse of a central Levantine state has proven far more destructive than the White House expected. Something has to be done because the Syria crisis has become a global one. The goal of this report is to advance the discussion of a realistic conflict-management strategy in Syria—not to assign blame for who started the war nor to fantasize about a neat, stable and unlikely solution.

Time to Stop the Meltdown

The debate in Washington has been dominated by two polarizing camps: all-out interventionists who argue for a full-fledged American entry into the Syrian war, and minimalists, led by President Barack Obama, who argue that virtually nothing the United States does could fundamentally alter the outcome.

In fact, there is a clear and preferable middle course: strategic, robust but limited military intervention, embedded in a clear political strategy to press for a negotiated settlement. Such a course would entail increased and sustained proxy warfare; some direct military intervention to protect civilians from indiscriminate bombing; and pressure on U.S. allies. The U.S. intervention would have two aims, neither of them new: to reduce civilian death and displacement, and to increase the faint chances of a diplomatic solution by raising the cost of continuing war for the Damascus government and its sponsors. In the short-term, hostile actors such as the Islamic State group (IS, also known by an earlier acronym, ISIS) and the Nusra Front might enjoy collateral benefits from increased U.S. intervention, but an American policy that employed force to protect civilians from the Syrian government would have to protect them from jihadists as well. (For example, if the United States shoots down helicopters that bomb civilians, jihadist fighters in the same area would enjoy greater freedom of movement, but U.S. proxies and allies could restrain these jihadists from taking control of new areas as a result.)

Over the course of months, a sustained military-political-humanitarian strategy could target any extremists who harm civilians, telegraphing a clear position about Syria’s future. To be sure, this strategy would be messy; it would require careful political management, and it might fail. It relies on the United States displaying more competence in a foreign intervention than it has in recent decades.

Increased U.S. intervention would represent a useful reassertion of American power and engagement in the crisis, and it would achieve multiple humanitarian and strategic aims. At worst, the Syrian crisis would be as problematic as it is today, but there would be fewer civilian casualties, and the United States would gain leverage with its allies on other matters because of its beefed-up engagement in Syria. At best, a more aggressive U.S. effort in Syria would limit Russian overreach, increase the likelihood of a political solution, and roll back some of the destabilizing regional consequences of the Syrian implosion.

Even in failure, increased intervention would mark a correction of American policy in the Middle East, which today suffers from a credibility gap,1 driven by two mutually reinforcing mistakes: first, an over-eagerness to pull away from regional crises, even when those crises implicate core U.S. national security interests, and second, a major gap between rhetoric and practice. That disconnect was vividly displayed when President Obama disavowed his “red line” and backed off his threat to bomb Bashar al-Assad for using chemical weapons, and continues to characterize a White House that speaks constantly of disengagement while devoting the lion’s share of its foreign policy attention at the Middle East.2

It is time for the United States to adjust its Syria policy, investing more military muscle and more humanitarian aid, while maintaining the high level of political engagement it has undertaken since mid-2015.

The United States can do better than containment—an approach that in any case is not working as intended. It is time for the United States to adjust its Syria policy, investing more military muscle and more humanitarian aid, while maintaining the high level of political engagement it has undertaken since mid-2015. At a time when the international risks are greater than ever, the United States is correct to pursue a political settlement for Syria’s destabilizing conflict. Washington needs to recognize its own power and assume more political risk than it has been willing to so far. The chance of a negotiated settlement is currently tiny; but with a calibrated—and somewhat risky—increase in military pressure, Washington can significantly increase the chances for diplomacy.

Properly executed, a more robust American intervention in the Levant will bring benefits even if it does not bring about peace in Syria: American action can reduce the human toll in death and displacement, while reasserting Washington’s commitment to a Middle Eastern state order. A more robust role in the conflict can reward groups that tolerate pluralism and avoid war crimes, while punishing those engaged in ethnic cleansing and the indiscriminate killing of civilians.

The stakes are incredibly high, with millions of Syrians in the conflict zone convinced they have no alternative other than to wait out the war, no matter how great the risk of death. Many of these civilians live in daily fear of starvation as a consequence of siege, barrel bombings, or the predations of unaccountable militiamen who roam every single zone of influence in a fragmented country. An example is Osama Taljo, a logistician from Aleppo who could have moved to Turkey or Europe, but who works with the council of the rebel-held half of the city. He helps maintain the limping remnants of education and civil administration for the 300,000 residents who remain in rebel Aleppo. Today, he is planning for a starvation siege that could begin at any moment. “The ones who remain have been through everything: shelling, bombings, hunger,” he said. “They tried leaving, they tried life in the camps. They’ve decided that they don’t want to be anywhere else. They are steadfast because they are committed to the revolution.”

Perhaps out of conviction, perhaps for lack of a better alternative, many Syrians plan to stay in their homes and support the rebellion until Bashar al-Assad goes, or they themselves die. The encircled residents of Aleppo are not unique. Across the city’s dividing line, civilians under government control weather indiscriminate shelling from rebels, which claims far fewer lives but is also a violation of the laws of war. Syrian citizens are living increasingly miserable lives, some of them under government control, some under Islamic State or Nusra, some under nationalist rebels.

The United Nations stopped tracking an official death toll in 2014 because it said it could not find reliable data. Estimates published by independent Syrian researchers in the spring of 2016 put the death toll at 470,000, and the UN envoy to Syria told reporters in April 2016 that he believed 400,000 was a reliable estimate. The lack of a solid number of dead, displaced, and wounded, along with a tally of children out of school, health impact, and infrastructure damage should not obscure the overall narrative arc: a modern, developing country, with pivotal strategic significance, is being rapidly destroyed.3 A Western official who has maintained close contact with Syrian officials on many sides of the conflict, almost since its duration, painted the Syrian war in almost apocalyptic terms.

A big share of the Syrian population is willing to go to the bitter end. We stopped counting the dead but they are still dying. The regime is executing people in jails. If the war ends, I think the death toll will be close to 1 million. This is a scandal. We’ve allowed the UN and humanitarians to be used by the regime and the Russians, for the sake of sovereignty, as if humanitarian aid is an end to itself. We’ve been a party to all this. We are toothless dogs.4

This official echoed a common theme voiced by international bureaucrats who have worked in conflicts including Rwanda, Congo, Afghanistan and the former Yugoslavia, and who say that Syria represents an unprecedented disaster for its own citizens as well as a black mark for the international community. The Western official, interviewed in Turkey, predicted that the Syrian war could drag on for a decade or more, even though the West had the power to intervene decisively to end it.

Syrian agency stands at the center of this war, but from the start the conflict has been grossly distorted by foreign sponsorship. Left to their own devices, Syrian factions will fight to stalemate. Given the depth of the existential convictions, without foreign intervention it could easily take a decade or two for all the sides involved to reach an equilibrium. A quicker resolution depends on a shift in the order of foreign interveners.

History tells us that a necessary if not sufficient precondition to resolve a civil war with this many international sponsors is for those international sponsors to reach an understanding. The longer the war drags on at its current level of destruction, the greater a tragedy that impacts geostrategic interests as surely as its chews up human lives. Russia has sought to dictate terms, alternating between bombastic militaristic overreach and pragmatic diplomacy. The United States can curtail Russia’s adventurism while continuing to extend an open hand on matters where diplomacy has gained traction.

The choice is not, as some analysts would have it, between starting World War III and letting Russia have its way in Syria like it did in the Ukraine. The U.S. military boasts a wide array of options that it can deploy in the Syrian war zone. Russia’s response might be unpredictable, but President Vladimir Putin does not want a U.S.-Russia war either. The standoff between Russia and the West is already messy and fraught, with major implications for NATO and European security. Avoiding a risky confrontation with Russia only postpones a reckoning: Russia has reasserted itself as a power player in the international sphere, but its ambitions—and destabilizing spoiler warfare tactics—can and must be checked before further expansion. If Russia’s expansionism is not managed in Syria, then the United States and its partners will have to do so in the future somewhere even closer to the borders of the European Union.

What Are the Options?

Options in Syria are all grim (for Syrians themselves, for the United States, and for all the regional intervening powers and groups, as well as the international community). The major options can be categorized as follows:

- Assad, and nothing else. Promote an outright Assad victory. Supporters of this approach argue that Assad’s rule is more stable than any alternative. If the United States made a full about-face, it could pull support from rebels and pressure allies to do the same, and signaling that it would accept consolidation of Assad’s power.

- Full withdrawal. Close down the covert rebel aid program, even curtailing or stopping the war against the Islamic State group. Such a course would probably come as part of a wider embrace of U.S. isolationism.

- Attack only Islamic State. Abandon any military involvement, direct or indirect, unless it is entirely concerned with Islamic State, and not the Syrian government.

- Partial withdrawal with humanitarian enhancement. Give up on influencing the prospect of a political solution, and decide that the United States will only take actions aimed to reduce death toll and displacement, and contain cross-border spillover of conflict. Increase non-military aid to bordering countries.

- Balancing the civil war and containing its spillover (the status quo). Provide military and financial assistance so that rebels do not lose, but not enough so they can make advances. Contribute to palliative humanitarian care, but not enough to actually contain refugee crisis.

- Enhanced containment. Intervene militarily and promote a negotiated settlement that includes all major parties, Syrian and foreign. Increase military action by advisers, proxies, and allies designed to reduce civilian death and displacement, and increase risk to Syrian government and allied forces of engaging in indiscriminate bombings and shelling. Deepen collaboration with unsavory rivals (Russia, Iran, Syrian government) to promote negotiated settlement, along with a renewed willingness to confront those rivals.

- Regime change. Give rebels sufficient military support to overthrow government and take Damascus, knowing such a course will likely result in a long, continuing civil war and further sectarian reprisals, with no natural successor to Assad on the horizon.

This report argues that enhanced containment—a limited military intervention in service of a political solution to the civil war—is the best among a set of difficult choices. U.S.-orchestrated regime change, such as an outright invasion, would go much too far, destabilizing the Levant and probably making everything in Syria worse, in a replay of the 2003 U.S. invasion of Iraq. An alliance with Assad would reward murderous tactics, guarantee an unstable and ungovernable Syria, and reinforce Tehran and Moscow’s most aggressive inclinations. So would withdrawal or a sole focus on Islamic State. The only viable options lie in the middle, and include the status quo.

All of the viable choices bear costs and risks; the status quo approach defers some of the worst blowback until later, when the emboldened Assad axis and foreign sponsors strike, while an entire generation of anti-Assad Syrians and disenfranchised Sunnis blames the West for their plight. An enhanced containment strategy requires the United States to cap Russian escalation now, rather than later, in perhaps an intervention even further from Russia’s core sphere; and it brings forward the moment of reckoning when Syria’s collapse and the expansionism of Iran and Russia force the United States to get deeper involved.

By escalating now, on its own terms, the United States can better control the course of events and be in a stronger position to respond to the unexpected.

The United States has steadily been drawn in, and has already deployed ground troops, in a clear and steady if unannounced escalation. By escalating now, on its own terms, the United States can better control the course of events and be in a stronger position to respond to the unexpected. The United States will weather some of the risks now, but it will also see the dividends of a more comprehensive engagement.

It is striking that the Syrian people doing the fighting and dying still cling to an idea of a nationalist Syria, which many see as a dead letter. On all sides, these nationalist idealists are dismissed: as amateurs—plumbers and dentists—by the White House; as terrorists by the government in Damascus; as apostates by jihadist fanatics; or as bloodthirsty sectarians by pro-government Syrian rivals.

In actuality, loyalty to the national idea still runs deep, despite the profound ruin visited already on the Syrian state. In separate interviews, members of every major ideological and sectarian group made unprompted arguments for a nationalist Syria united under a single Damascus government.5 To be sure, they differ on key matters, such as local autonomy and a definition of rights that transcends sect or ethnicity. But nationalism still resonates with some members of every major group: Alawites in Tartous, pro-government Sunnis and Christians in Damascus, Druze in Sweida in the South, anti-government Arabs and Kurds in the North. A nationalist Syria, with room and rights for all its constituent parts, is by no means a universal conviction, but its appeal retains surprising power across ideological lines, appealing to Syrians whose political loyalty runs the gamut from Al Qaeda to Baath Party.

I met Sunni militiamen fighting for the Syrian government and Kurds fighting for the Free Syrian Army (FSA). There is a sectarian flavor to the war, but individual Syrians constantly defy it. One militia commander in the north, a Kurd fighting with a Free Syrian Army group that happily accepts support from Americans and other “Friends of Syria” governments, has spent five years at arms and has no intention of dropping his struggle. Tellingly, however, he dismissed the long-term importance of fighting men to the future shape of Syria, which he firmly believes can, and should, be driven by pragmatic, collaborative, inherently reasonable Syrian civilians.

Isn’t is sad? After four years, people are dying, and the faction leaders are trying to put on a show to impress their sponsors. They are trying to make a case for their movements, to sell themselves. The people made the revolution, not the factions. It is normal for warlords to thrive on a war economy. What is exceptional is that Syrian people keep insisting on freedom. I am confident that Syria will not be divided. Dictatorship in Syria is no longer possible. Syrian people will be the basis of power. The revolution is not Nusra, ISIS, PYD, regime, the FSA, it’s not my faction. It’s the people.6

Even on the government side, among communities that have disdain for anti-government rebels, I heard support for reform, reconciliation, and more-inclusive governance. One pro-government paramilitary fighter who had taken part in some of the worst battles, matter-of-factly stated that he would reconcile with opposition Syrians who did not have blood on their hands. Alawites have the most to lose, as a group, from a transition that would bring Sunni majority rule, but even those Alawites who risk murder or imprisonment from Assad’s security forces if they speak openly about a post-Assad Syria are adamant that they do not want their country divided—a de facto acceptance that they will need to expand, rather than contract, their modus vivendi with members of other sects and political ideologies.

Today, across all lines in Syria, there is deep anger at local despots and militiamen, and at their foreign sponsors, including the United States. Many scapegoat the United States, holding it responsible, at least rhetorically, for every bad thing that has happened in Syria since 2011, blaming it either on U.S. actions or the lack thereof. Roiling frustration has prompted many analysts and policymakers to claim there are no real options. Despite the sad condition of Syria, however, there are still many options and choices for Syrians and for intervening powers, and the war’s likely resolution is still unknown. In the end, outcomes are more important than sentiment, without dismissing the serious nature of this feeling, especially when much of it is rooted in real policy developments. If the United States can midwife better results, it will gain credit in some quarters. It already is shouldering more than its rightful share of blame for a war that has turned out worse than any of the initial combatants predicted in its first year.

The Messy State of Play

Perhaps based on a faulty interpretation of the previous decade’s downward spiral in Iraq, U.S. policymakers believed that a violent power vacuum in Syria would pose only a local problem. Even after Islamic State conquered the Sunni desert straddling Iraq and Syria and the United States launched a military campaign against it, U.S. policymakers continued to treat Islamic State as a containable regional problem. But the spreading crackup of sovereignty and spread of violence throughout the Levant turns out—not surprisingly—to pose a threat to more than the just lives, well-being, and stability of the hundreds of millions who live in the Middle East and its environs. It poses strategic threats to Western interests.7 Sadly, only the refugee crisis and Islamic State attacks in the West forced a belated realization that the collapse of the Arab state system and the descent into foreign-sponsored warlordism in Syria would matter widely.

In January 2017, a new U.S. president will take over, and anticipating a policy reassessment by the global superpower, all the Syrian and international actors in the conflict are doubling down on their current course, waiting to see what Washington will do. America can’t resolve the crisis alone, but for all the talk about U.S. retrenchment and retreat from the Middle East, America remains the dominant power, with the ability to set the agenda and steer the conflict. Syria’s war is fast on the way to becoming the signal destructive event of the post-colonial Arab world. Not since the founding of Israel in 1948 has violence in the region been more strategically consequential—quite an achievement, considering the region’s modern history. Previous conflicts, including the Iran-Iraq war, the U.S. invasion of Iraq, and the 1967 and 1973 wars with Israel, left viable central states, despite their horrifying human costs. Not so the war in Syria, which has accelerated a meltdown that began with U.S. invasion of Iraq, and which has catalyzed new, entropic forces that are undoing the Arab state system and breeding a toxic constellation of warlords in its place.

Letting Syria follow the course it is on today would be a human tragedy for the millions displaced and hundreds of thousands killed. There is ample reason on those grounds alone to do more. Stopping mass murder is a righteous cause. Syria’s dissolution is also a strategic problem with massive impact on core interests for the United States as well as every country in the Middle East and its orbit. That’s why, despite President Obama’s rhetoric of non-engagement, he has overseen a massive covert military program in Syria,8 has launched an overt war against Islamic State, and has spent more than $5 billion on humanitarian aid. 9 America’s strategy in Syria clearly recognizes that vital interests are at stake and has sought to manage the direction, and consequences, of a catastrophic conflict. But American decision-makers remain conflicted about just how vital are the interests in Syria; with each escalation, they seem only belatedly to recognize the importance of the crisis. President Obama wisely wants to avoid another American invasion in the Middle East, but his strategy underestimated the importance of the Syrian state, beyond the person of Bashar al-Assad, as a linchpin of regional order. The U.S. approach has tried to be realistic about the considerable drawbacks of the armed opposition, the fundamental problems with the Assad government, and the limitations on U.S. power, which cannot dictate the outcome in Syria.

Where President Obama’s strategy has fallen short has been not in concept, but in execution.

Where President Obama’s strategy has fallen short has been not in concept, but in execution. A more effective strategy would amplify the military dimension of the military-diplomatic-humanitarian tripod, and openly manage the politics of a higher-risk higher-payoff approach—a campaign that might in the short term see enemies such as Al Qaeda win momentum off the back of American intervention, but which in the long-term would make the Arab world a less hospitable place for both jihadi nihilists (such as Al Qaeda and Islamic State) and secular torture-happy dictators (such as Bashar al-Assad). America and its allies will be able to chart a more effective course if policymakers can reframe the Syria debate away from the false binary into which it has devolved today, with hawks on one side advocating invasion and confrontation with Russia, and minimalists on the other claiming that there’s just nothing more the United States could do given the sorry state of armed and political opposition in Syria.

Policy-makers should accept the sad, realist assessment that Assad is incorrigible as long as the armed opposition is fragmented and dominated by its least-appealing elements. A frank appraisal does not mean that nothing can be done other than to watch Syria burn, bemoaning that the only alternative is to start World War III with Russia. There are in fact plenty of avenues to pursue that improve the odds of America’s preferred outcomes.

Foreign policy doesn’t operate in clean binaries, but in gray areas. Sound management of U.S. interests in the Middle East, including the promotion of better governance within a stabilized state system, suffers under extremes, including neocon interventionism and aloof retrenchment. It remains a core interest to preserve a unitary state in Syria, and a worthwhile aim to see it governed better and more inclusively than it has been under Bashar al-Assad. Supposing that Syria is headed for a long, grinding showdown between Assad’s forces and a constellation of jihadists, it is still a worthwhile American investment to prolong the existence of a nationalist opposition, and to raise the costs of criminality and expansionism for Assad, Tehran, and Moscow. American presidential frustration notwithstanding, the Middle East merits a great deal of policymaker attention, and continues to get it. A better policy would make sure to maximize that ongoing investment of resources.

A fair read of the war in Syria suggests that there are only unsatisfying options, but that the United States could significantly increase the chances of a political settlement—and critically, could save numerous lives—with a more robust version of its current carrot-and-stick strategy. A sharper and less episodic U.S.-led intervention could raise the military cost for the Syrian government and its foreign sponsors, while protecting civilians who die by the hundreds every week under shells, barrel bombs, and other indiscriminate fire. Meanwhile, the White House should continue the sustained and pragmatic diplomatic engagement it began in 2015, which has not yet borne fruit but which has improved the possibility of a negotiated settlement from nonexistent to plausible. A realistic assessment will promote discussion of plausible approaches, rather than wishful thinking. Unlike in other conflicts, there is plenty of expertise and experience in the region and among the intervening powers, including within the U.S. government. If and when the United States adjusts its approach to Syria, it will have ample knowledge on which to draw.

The White House Containment Policy

Vociferous critics claim that the Obama White House has not had a policy on Syria, but more than five years of American action paint a picture of a coherent approach (although one that has been inattentively implemented and beset by missed opportunities). President Obama has followed a containment strategy in Syria, with three major components:

- Limited military intervention to prevent any side from winning the war outright

- Support to bordering countries to minimize regional instability and blowback

- Humanitarian assistance for Syrian refugees and internally displaced

Many critics of President Obama’s approach advocated direct military intervention against the Damascus government, on either moral or strategic grounds. Some have argued that the White House has been passive, in the throes of strategic drift, and “has no Syria policy.” These Syria hawks often paint a simplistic and misleading picture of a region in the grip of a hostile, dominant Iran, whose leaders have been emboldened by the nuclear deal, given a green light by President Obama to run roughshod over the Middle East. Meanwhile, President Obama and his surrogates have argued that he has done the best he could with the mess he inherited from his predecessor George W. Bush. (The mismanaged and illegally justified invasion of Iraq left few good options for the United States in the Arab world, but Washington has more ability to shape events than it has admitted.) According to public assessments by the president and his surrogates, the United States faces an array of bad choices and, no matter how much it invested in a Syria policy, would not be able to determine the outcome. Neither of these analyses fully reflects the situation.

In fact, a fuller and more complete assessment of the Syrian conflict and America’s role reveal a significant commitment by the White House that is vastly out of kilter with the administration’s rhetoric and politics. On the one hand, the United States has remained tightly involved in the Syrian conflict from the beginning, lending political support to those who wanted to overthrow Bashar al-Assad, and then funding, training, and arming parts of the opposition. The United States at one point supported an effort to set up a government-in-exile, but that project never fully materialized, as different “Friends of Syria” backed competing leaders and groupings. Today, there is an official opposition coalition, which maintains offices abroad and receives significant foreign funding. But that coalition has remained mostly irrelevant to developments inside Syria, disconnected from the most important groups doing the fighting and delivering services in rebel-controlled territory.

Most of the armed opposition has survived only because of foreign intervention—the exceptions being the most distressing elements: Islamic State and Nusra. The U.S.-led covert military assistance mission, supported by allies including Jordan, Turkey, Qatar, the UAE, and Saudi Arabia, has kept alive a nationalist armed opposition, composed of fragmented brigades, often led by Syrian Arab Army defectors, and usually operating under the brand name Free Syrian Army. Much of that U.S.-blessed support has flowed through so-called operations rooms in southern Turkey and in Jordan. 10 American allies have separately, and generously, funded other more Islamist fighting forces, including the Army of Islam around Damascus and Ahrar al-Sham, a group with both jihadist and nationalist pedigrees that is probably the single most powerful militant rebel force in northern Syria, outside of Al Qaeda’s Nusra Front and the Islamic State group. Few of these groups—and none of the larger, militarily significant ones—can be described as “moderate.” (For that matter, nor can the Syrian government.)

Today, the Syrian state, under President Bashar al-Assad, is winning back territory it lost in preceding years. Last summer, Assad admitted in a speech that his government has suffered from manpower shortages that might force him to reconsider his goals. Some Assad supporters thought the president would have to withdraw his domain to a rump state, comprised of Damascus and the coast. But then a decisive Russian military intervention began in September 2015, marked by sustained bombing of rebel positions and civilian infrastructure, including hospitals. Meanwhile, Iran and Lebanon’s Hezbollah have continued to contribute commanders, ground troops, and strategic leadership to the government’s military campaign. As a result, the government’s fortunes have turned. Assad and his allies have reconquered some rebel positions. They have nearly encircled rebel-controlled half of Aleppo, which now retains a single, contested passage to the outside world: the Castello Road.11 They have retaken Palmyra from the Islamic State group. And they are beginning to nibble away at rebel positions in Eastern Ghouta, the countryside and urban sprawl immediately flanking Damascus, which has posed a continuing threat to the capital. The Southern Front, which includes the parts of Syria bordering Jordan and the Israeli-controlled Golan Heights, has been calm when compared to the rest of Syria. A sizable Free Syrian Army contingent in the south operates under tight Jordanian control. Perhaps as a result of an understanding between Jordan and Assad, the Free Syrian Army in the south has held back, refusing to support besieged rebels in nearby areas like Eastern Ghouta, and refraining from attacks on vulnerable government positions. In another danger sign, recent reports also suggest that Islamic State is making new inroads in the south.12

The regime’s recent gains come thanks to a major acceleration in support and direct intervention by Russia, Iran, and Hezbollah. The economy is in ruins and the Syrian pound has collapsed, surviving financially on credit and grants from Iran. The military gains have come almost entirely thanks to foreign intervention on behalf of the regime. Russia and Iran can probably maintain their current level of military support indefinitely, although some analysts differ on this point. Hezbollah, which has contributed the most important infantry fighters, along with critical commanders, can probably maintain its share for several more years to come. Frontlines have fluctuated, but there are signs that the regime’s hold over its home ground is porous. Bombings in the Alawite coastal heartland in May revealed alarming security lapses, and raise once again the danger that millions of displaced Sunnis, living under government control, might turn into a fifth column for the rebellion.

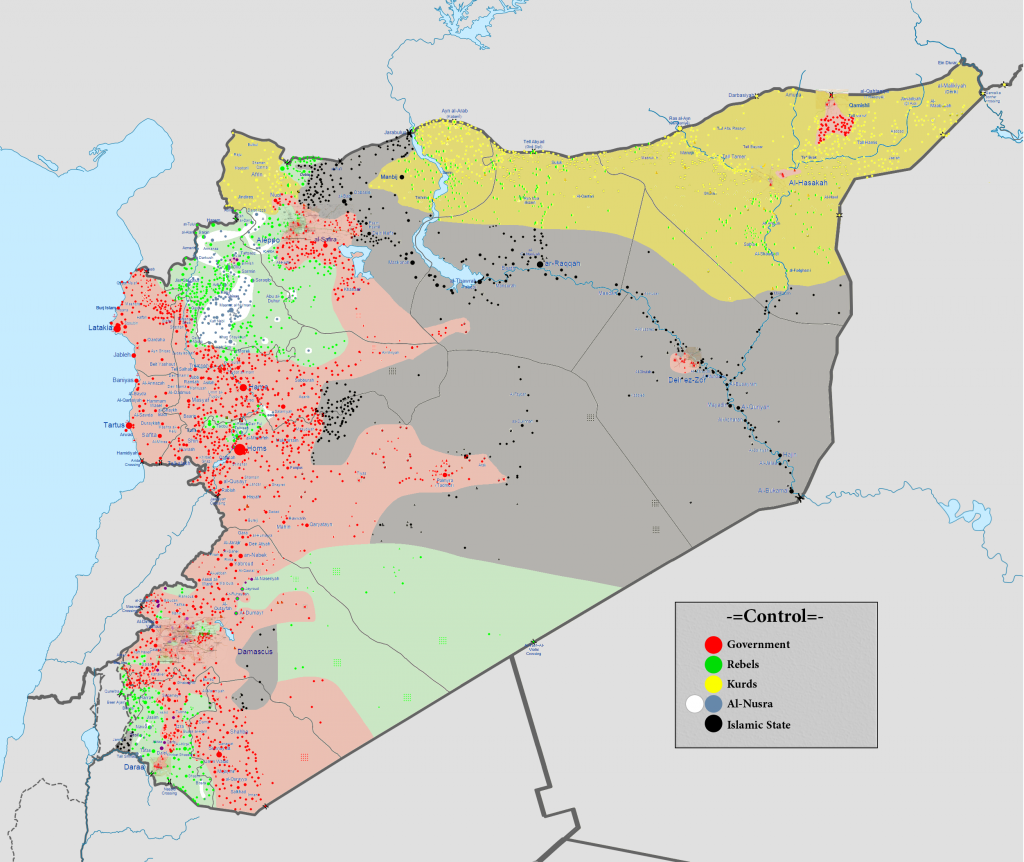

At times, the Syrian conflict can seem like a constellation of related, but distinct wars.

At times, the Syrian conflict can seem like a constellation of related, but distinct wars. There is the war with Islamic State, largely taking place in Syria’s eastern desert, in a single, geographically distinct zone. Another war, on the eastern flank of Damascus, pits the government against the Army of Islam (although the death of Army of Islam founder Zahran Alloush in December has loosened his group’s domination of eastern Ghouta and could eventually result in the war there turning into a free-for-all). The largely static Southern Front features a face-off between the Free Syrian Army and the government, although Hezbollah and Israel play a major role in the Golan, while the Druze in Sweida are not fully under government control. The north is a rebel redoubt, with the major armed groups still competing for dominance around Aleppo and in Idlib. The Alawite coast remains in government hands, but a huge displaced Sunni population there, along with continuing feints by rebel militias, as well as recent Islamic State-claimed terrorist attacks, suggest that the safest government area could yet devolve into another front. There are other, smaller, geographically delineated conflict zones in Syria. Yet all these battles are part of one major war—and most of the combatants in the end want a single Syrian state in control of Syrian territory.

Who’s Who?

Assad’s government remains an extreme exemplar of one-man rule, a regime that relies less on one sect (the Alawites) or one clan than it does on the single person of Bashar al-Assad. Assad rules through relatives, his clan, mafia-like groupings in the business and intelligence spheres, and even through sectarian loyalty. But students of the regime are hard-pressed to discern independent structures or decision-makers that entail a state apparatus independent of the ruler himself. Hence the slogan of regime supporters: “Assad or we burn the country.”

Assad’s style of rule makes it difficult to gauge the alternatives that could replace him within his own constituency. The secret police still aggressively patrol any hint of dissent from within government-controlled Syria, and even supporters of Assad say they live in fear that male relatives will be press-ganged into military service or that family members will be taken prisoner and held for ransom by unaccountable fighters.13 While at the top, regime control is ever-more consolidated in Bashar al-Assad after the deaths of key senior officials, on the ground government-held Syria is more and more fragmented. The war is being fought by troops from Syria, Lebanon, Iran, Iraq, Afghanistan, and elsewhere, commanded or advised by officers from Syria, Lebanon, Iran, and Russia, at a minimum. Multiple chains of command overlap pro-government forces, including the official military, the state-sanctioned National Defense Forces, smaller militias arranged on sectarian, clan, or ideological basis, and foreign militias. Local bosses wield more authority than ever before. The regime’s many competing intelligence forces face more threats than they are able to process, and have proven more effective at jailing civilians than stopping car bombs. Fragmentation and manpower shortages impose crucial limits on the state’s reach.

But Assad’s state also possesses significant wells of legitimacy. How deep that legitimacy runs is an open question—one on which Assad has staked his survival—but his rule has maintained some degree of buy-in from millions of Sunni Arabs, as well as thousands of Kurds. Although it is impossible to measure public opinion in a society as repressive as government-controlled Syria, there seem to be a considerable number of citizens who support Assad. Conversations suggest there are plenty more, perhaps numbering in the millions, who do not like the way Assad runs Syria but prefer his secular, pluralistic dictatorship to the alternative they believe the rebellion offers: violence, anarchy, or a Sunni theocracy. Many of these fence-sitters have been convinced by government propaganda, or information about life in rebel-held areas, that the anti-Assad forces are dominated by Sunni triumphalists obsessed with an austere vision of religious law. Their assessment would shift if they were to be convinced that governance under anti-Assad forces would be less abusive than their status quo under Assad. In private, some members of minority groups (Alawites, Christians, Shia) as well as secular Sunnis say that, despite its routine practice of torture and detention, they reluctantly prefer Assad’s police state, which has a comparatively less sectarian and more class-based approach; the alternative, in their view, is the kind of unchecked sectarianism they have heard about in areas controlled by Islamic State, Nusra, Ahrar, the Islam Army in Eastern Ghouta, even supposedly moderate Free Syrian Army-branded groups.14

For all the evidence that it is a fragmenting state on the verge of dissolution, Syria remains a state. Its pre-2011 borders remain its recognized international frontier. Great portions of the country have slipped out of government control into the hands of rebels, and yet, in many of those areas, the government still pays public sector salaries and engages in trade or other dealings with its enemies to maintain basic services such as telecommunications, electricity, water, and fuel supply.15 The government is too weak to overtake the Free Syrian Army, Ahrar, Nusra, Islamic State, the Kurdish People’s Protection Units (known by their Kurdish acronym YPG), and the many other smaller armed factions, or even reassert control over its putative allies in secure areas—and yet, in many rebel-held areas the rebels cannot maintain the infrastructure of life without the government (and in many cases, without cooperating with their own detested rivals within the rebellion). Weak as it is, the Syrian state is more intact than, for example, the Iraqi central government under U.S. occupation in 2003–04; in terms of raw administrative capacity, the Syrian state in the midst of a devastating civil war is more of a state than Lebanon’s is, twenty-five years after fighting there has ended.

Meanwhile, rebel-held Syria remains a kaleidoscope of fractured militias, characterized by a chaotic mashup of ideologies, interests, and sponsors. The only unitary actors with discernible chains of command are the Islamist-jihadist hardline groups: Islamic State, Nusra, and Ahrar el Sham. All three groups have coherent military and political leadership, all have reliable funding sources, and all three have managed to take and hold territory. To varying degrees, however, all have extremist, sectarian beliefs at their core. Their project to establish Islamic rule in territory under their control is anathema to any Syrians of secular or non-Islamist bent. Some analysts of takfiri ideology (the practice of some Salafi-jihadists of declaring other Muslims apostates) have parsed the considerable differences between the three groups. Islamic State has declared a caliphate and staunchly opposes modern national borders, already ruling a vast, oil-rich state straddling Iraq and Syria. Nusra brands itself as a franchise of Al Qaeda, although it is unclear whether any Al Qaeda leaders exert authority over Nusra. Nusra has not yet declared a caliphate, and has recruited considerably among Syrians who want to wage a jihadist struggle within the national borders of Syria. As a result, Nusra has taken much more pains than Islamic State to win local loyalty in Syria, but there is no evidence to suggest it is a nationalist organization or that it will tolerate pluralism or dissent.16

Among the jihadists, Ahrar el Sham, backed generously by the government of Turkey, has leaned closest to the non-jihadist opposition, going so far in December to ambivalently endorse rebel negotiation with the Damascus government. Ahrar, like Nusra, fights in tandem with Free Syrian Army-branded groups, fruitfully partnering in some battles with militias funded and armed by the CIA. Unlike Nusra, which has also crushed Free Syrian Army groups in local power struggles, Ahrar has so far protected its nationalist junior partners. Ahrar has developed some pragmatic modes of negotiating with other rebel groups and with foreign governments, but locally, inside Syria, it implements a version of religious rule that makes it inimical to concepts like a secular state, or a genuinely pluralistic polity. Some close analysts of Ahrar emphasize the pragmatic nature of the group’s leadership, which has shifted to less rigid positions on religion and on political negotiations over the last year. Ahrar ties to act as bridge between Jihadist and nationalists. If forced to choose between Free Syrian Army allies and Nusra, in an outright confrontation, it’s unclear which way Ahrar would go—especially if the Free Syrian Army groups remain as weak, fractured and erratically supported as they are today.

The Kurds are a complex group. Their dominant militia today, the YPG, has fashioned itself into the premier “reconcilable” faction—a group that can do business with the U.S. but can also negotiate with Assad. Most opposition groups do not consider the YPG a rebel group at all; many Free Syrian Army factions list the YPG along with Assad and Islamic State as existential threats. In some of the area under its control, the YPG has allowed Assad’s government to maintain a security presence, one of many pieces of evidence that lend credence to the notion that there is an understanding between the YPG and the Syrian government.17 The YPG has won direct military support from the United States, political support from Russia, and reluctant support from Iraqi Kurds and from a limited number of Arab tribal militias from northern Syria who are fighting Islamic State. In fact, the most vociferous opposition to the YPG comes from Turkey, which understands the YPG as a faction of the PKK, which has been engaged in an off-and-on decades-long separatist struggle against the Turkish central government and which is considered a terrorist cult by the government in Ankara.

The Army of Islam, which until recently was the dominant rebel group in the environs of Damascus, controlled Eastern Ghouta with an iron fist until the end of 2015. It has been linked to many war crimes and the disappearance of prominent secular opposition dissidents, most notably human rights activist Razan Zeitouneh. Army of Islam founder Zahran Alloush ran his zone of control with a distinctly Islamist tone, but he projected a nationalist image and kept jihadist groups at bay. Since his death in a Russian airstrike, his movement has lost dominance and the Syrian government has made inroads into Eastern Ghouta. A representative—Mohammed Alloush, a relative of Zahran—of the Army of Islam led the rebels’ High Negotiations Committee to the Geneva peace talks, until his resignation in May 2016. The Army of Islam, like Ahrar el Sham, has tried to split the difference and create an Islamist-nationalist hybrid model, but its rhetoric and governance have failed to win the trust of secular and non-Muslim Syrians. It is also a force in decline, with a single geographical base of operations in which its authority has fragmented since the demise of its founder. The Army of Islam is undeniably part of the landscape, like hardcore supporters of Bashar al-Assad, but does not present a template for reconciliation or inclusive governance in post-war Syria. However, like Ahrar, the Army of Islam’s coherence and discipline make it an attractive proxy partner for outside interveners.

Finally, there are the Free Syrian Army-brand rebels, the beneficiaries of a great deal of investment over the course of the war by Friends of Syria, the pro-rebel, anti-Assad, group of nations that includes the United States, Turkey, Saudi Arabia, Qatar, and the United Arab Emirates. The Free Syrian Army groups emerged from various militias that sprang up when Assad’s security forces confronted the nonviolent uprising in 2011. Free Syrian Army brigades evolved from many entities, including citizens’ militias, local mafia and gangster groupings, and semi-professional forces led and staffed by defectors from the Syrian military.

Opposition politicians, ever-more detached from the fight on the ground, seem to float in an acronym soup.

Opposition politicians, ever-more detached from the fight on the ground, seem to float in an acronym soup. The Free Syrian Army was supposed to provide a nationalist alternative to Assad, and to serve as a centrally controlled rebel army under the political leadership of the Syrian National Council (SNC), another entity cobbled together under the aegis of Friends of Syria. Today both the SNC and FSA still exist, but their promise never materialized. Today the official opposition body backed by the West is called the National Coalition of Syrian Revolution and Opposition Forces.

During the last round of peace talks, yet another expanded grouping, the ad hoc High Negotiation Committee (HNC), represented the opposition. For the time being the HNC remains the most relevant opposition entity, until, presumably, it is supplanted by yet another grouping. There have been glimmers of unity and coordination, such as the coordinated compliance of Free Syrian Army brigades with the spring 2016 cessation of hostilities. But when it comes to merging command structure, the Free Syrian Army brigades remain as bitterly fragmented today as they were in 2011–12—perhaps even more so. No amount of cajoling by the United States and other sponsor nations working through the Military Operations Center (MOC) in southern Turkey has persuaded even the most minute brigades to submit to an umbrella command. Opacity and fragmentation characterize all sides of the conflict, including allies and sponsors of the government in Damascus. The difficulty of coordinating positions or enforcing major decisions, such as ceasefires or aid deliveries, suggests caution and humility when setting expectations for the future. In such circumstances, conflict management, containment, and mitigation are wiser aims than outright resolution.

Constantly Shifting Terrain

Every battle, it seems, requires renewed negotiations between rebel groups. One day, factions might join forces against the regime; the next, they are just as likely to be fighting each other. The MOC groups, as they are known in shorthand, are vetted battalions that are allowed to apply to the MOC for weapons and support. In practice, most of the surviving groups that self-identify as Free Syrian Army have been vetted and operate under the MOC umbrella, with some exceptions, such as the Nour al Din al-Zinky Movement, which was expelled from the MOC. Some of the Free Syrian Army groups are more religious, some more secular, some more urban, some more rural, but none of them has the ability to wage a major operation alone. Many Free Syrian Army groups have been guilty of corruption, brutality, torture, and other crimes.18 Equally, most have proven incapable of sustaining power beyond their home-base towns or expanding their ranks of fighters. In most of rebel-held northern Syria, the Free Syrian Army groups exist largely at the pleasure of Ahrar or Nusra, and in some areas face the specter of destruction by Islamic State. Ahrar and Nusra enjoy benefits by allowing the MOC groups to operate in their spheres of influence. The larger Islamist-jihadist groups can demand a share of weapons from the MOC groups, an arrangement confirmed by many commanders. In battles, the MOC groups contribute key tactical capabilities, such as anti-tank missiles, which complement the infantry deployed by Ahrar and Nusra, along with Nusra’s suicide bombers. This sort of partnership, in fact, allowed a temporary rebel alliance called the Army of Conquest to take over most of Idlib province in the spring of 2015, before the regime’s renewed advance.19

After five years of heavy supervision, the Free Syrian Army commanders have taken a few suggestions from their sponsors. Today, most brigades have a full-time political officer charged with negotiating with other militias and with political leaders, and with communicating to outsiders. Commanders have slowly learned the rhetoric of pragmatism, now making routine if perfunctory rhetorical nods to the need to protect minorities in a post-Assad Syria. They are frank about their weakness in the face of the jihadist factions, and increasingly, honest about their reliance on foreign sponsorship. They believe that their fighters can go on indefinitely, in limbo between outright victory and defeat, but that civilians in “liberated Syria” have suffered more than a population can endure. They also understand that they are outgunned and trapped between three different enemies: Assad, Islamic State, and the Kurds. They know, too, that an open rupture is likely to come with Nusra.

Ideologues on all sides misrepresent this meddled state of play. Supporters of the Assad regime pretend that it is possible for the Syrian state to re-extend its writ over the entire national territory, under the leadership of Bashar al-Assad. Such a claim ignores the tenuous state of the government, even as it advances; long ago it maxed-out on its own resources and manpower, and relies almost entirely on foreign fighters and firepower to make a military advance that, if successful, would only restore the status quo of early 2015. Even with full Russian engagement, greater than any seen so far, the demographics of the conflict run overwhelmingly against the government. Russian air power has shifted the momentum of the conflict, but there’s no evidence that the government could achieve a full victory without the unlikely deployment of Russian ground troops.

Assad’s ambitions also ignore the implications of his government’s brutal scorched-earth tactics, with friends as well as foes. In government territory, Assad exerts control through a vast machine of torture, surveillance, and detention. In battles against rebel areas, Assad’s strategy has first and foremost been to make civilians pay, whether through starvation sieges, targeting of medical personnel, and indiscriminate bombing of civilian areas. Opposition sympathizers have ample reason to believe that they will face retribution or death if the government retakes their areas. As a result, a major share of the country—for instance, rebel-held Aleppo, and before it, Old Homs—has preferred starvation or slaughter to surrender to Assad’s forces.

Opponents of Assad, on the other hand, avoid the ugly state of affairs on the opposition side. Islamic State, Nusra, and Ahrar are strong not only because of their funding sources, but because they have persuaded important Syrian constituencies to their side, whether for reasons of ideology, self-interest, or a mix of the two. There is no sizable “moderate,” nationalist, or secular faction that could lead a military offensive, much less claim to represent the opposition in a negotiating setting. Any anti-Assad intervention will, in the short-term, benefit the most powerful factions on the ground—the extremists and the jihadists. Necessary interventions, such as shooting down helicopters that drop barrel bombs, or jets that bomb hospitals, will as a collateral benefit help Nusra and similar groups. That is not a reason to avoid protecting civilians, but it is a consequence that must be acknowledged, managed, and in the long-term, obviated by expanding the intervention to roll back jihadists from non-regime Syria.

Syria has fragmented almost beyond repair. It is not impossible to reverse course and to buttress a centralized state, but it will be a messy process. The status quo, however, is at least as messy, and far more hopeless; today, Syria’s implosion has poisoned the lives of most of Syria’s 26 million inhabitants, while spreading the specter of violence and sectarianism deep into neighboring countries. The war in Syria today is a war that spans Iraq, Syria, Turkey, and Lebanon as a hot war, and which is indelibly linked to cold and hot wars in the Arabian Peninsula and Iran. The accelerated collapse of this pivotal Arab state continues to have massive tactical and strategic consequences. Any serious intervention will carry real risks and if successful will bring halting, perhaps incremental dividends. The scope and value of an intervention must be measured against a status quo that is catastrophically destabilizing and toxic to the entire Arab region as well as to core American national security interests.

Assist, Protect, Pressure: A Three-Pronged Strategy

American engagement should revolve around three imperatives: assist, protect, pressure. On assistance, the United States is already the biggest single financial donor to Syrian aid. But it is more than just dollars that matter; total American aid to refugees and other victims of conflict—including support for resettlement, health care, and education—should equal that of major donors such as Turkey and Europe. America has been generous, but it should achieve more in effective help than any other state, in order to justify its role as honest broker.

On protection, U.S. military force should quickly and decisively be brought to bear to protect vulnerable civilian populations and infrastructure. As a first step, protection requires using military force to prevent or retaliate for some of the most egregious and indiscriminate attacks on civilians. Protection actions would include shooting down some helicopters and planes, in order to reduce the amount of barrel bombs and conventional bombs dropped on civilian, rebel-held areas; retaliating against sources of fire on medical facilities, markets, schools, and civil defense facilities; and quick, decisive strikes against government forces or their allies who are besieging civilians or interfering with the flow of humanitarian aid.

On pressure, America should push the Damascus government and its opponents to engage in serious negotiations, using military action and the White House’s bully pulpit. Serious talks require major concessions, which are more likely if the United States uses its considerable influence to make sure that all the potential spoilers (including Assad, Islamic State, and Nusra) know the United States will prevent them from achieving outright victory. The thrust of U.S. escalation is that it might produce, in the long run, a significant de-escalation of the entire Syrian conflict. And if it does not, the United States at least will be able to save and protect many civilian lives, and to reap strategic and political benefits throughout the region from having taken a more active role in Syria’s fate. It will also shift the burden of the war to be more equitably shared by the government and its forces, and not, as is currently the case, overwhelmingly by civilians in rebel-held area. A wise U.S. president need not be locked into further escalation; limited military intervention is only a slippery slope if the United States fails to exercise discipline.

The military, political, and humanitarian investment should have the goal of pushing Syrians to reach a negotiated settlement to the civil war. Since the summer of 2015, the U.S. Department of State has been engaged in sustained high-level diplomacy surrounding the conflict, representing the one pillar of the policy where American engagement already is where it should be. Military and humanitarian pressure should rise to a level that is in balance with the political commitment to diplomacy. Military intervention (and humanitarian aid) should shore up non-jihadi rebels (up to and including Ahrar el Sham, if it continues its practical collaboration), and should punish the government when it is possible to do so without hurting civilians. In some cases the to-do list is clear: quick air strikes to support any vetted rebel group that is about to be overrun by the government, Nusra, or Islamic State; lethal force to protect any vulnerable population, such as internally displaced people in camps threatened by jihadists or by the government; and sustained military aid to end siege warfare and keep supply routes open.20

Prong 1: Assist

The “assist” plank is the most straightforward. The United States should double its already generous humanitarian expenditures, marking a major financial commitment (although it would amount to a fraction of the costs of a military campaign).21 This expenditure would have serious impact. It would mark America’s position as the leading humanitarian donor, and should be accompanied by far more political messaging to make clear that the United States gives the lion’s share of humanitarian aid to Syria, as it does in many other troubled parts of the world. The tangible impact is important: every additional group of children enrolled in school, ill people given medical care, or displaced people sheltered, is important—these are clearly achievable goals. The moral impact is equally crucial: the United States can and should frame Syria’s conflict as a war against human beings and the institutions that enable them to live with basic services and dignity.22

Since the conflict began, the United States has spent roughly $5 billion on humanitarian aid to Syria. It continues to underwrite much of the essential aid that keeps people alive in areas occupied by Islamic State, Nusra, the Free Syrian Army, and even the Syrian government. In many ways, international humanitarian aid has propped up every party to the Syrian conflict; but the funding has also checked the mind-numbing human suffering caused by the war. In comparison, the European Union has spent about €5 billion (equivalent to about $5.5 billion), while Turkey has spent about $8 billion. The United States has admitted an appallingly low number of refugees from the conflict. Meanwhile, more than 1 million Syrians have sought asylum in Europe. Lebanon houses more than 1 million registered refugees and an estimated 500,000 more unregistered refugees, an amount roughly equivalent to one-third of Lebanon’s total population. Turkey has taken in at least 2.8 million Syrian refugees. The United States has not admitted significant numbers of refugees, and it ought to do much better on that front; but what it can do quickly is shoulder an equal share of the burden by paying to provide for the displaced. That commitment would enable the United States to stand shoulder to shoulder on the same ground as its European and Middle Eastern allies who are reeling but doing their best to help the victims of the war.

The United Nations—which oversees most humanitarian aid inside Syria—has proven incapable of functioning impartially.23 The Syrian government has been able to dictate which populations receive aid and which do not, all the while siphoning off a great deal of foreign humanitarian aid for its own supporters. The United Nations and its agencies operate under a state-to-state paradigm in an area where dozens of entities claim overlapping sovereignty.

The United States can take action to stop its contributions from being held hostage by the distorted approach taken by the UN agencies in Syria. It can and should withhold any aid that is funneled through the Syrian government, unless the Syrian government immediately lifts all access restrictions (which it has been unwilling to do throughout the conflict, in defiance of the U.N. Security Council). It should run its own airdrops24 of aid to besieged areas, since it has greater logistical capacity to organize airdrops and has the flexibility to coordinate air drops with the Russians. In Islamic State and Nusra areas in northern Syria that depend on food and other basic aid from U.S.-funded contractors, the United States should dictate new terms of engagement. If aid does not reach its intended civilian beneficiaries, it can cut off supplies. U.S. forces can also target pro- and anti-government militias that engage in predatory behavior and steal or block aid deliveries.

Prong 2: Protect

A more robust military campaign should build on both of the missions already underway: the CIA’s covert sponsorship of armed proxies and the Pentagon’s overt train-and-equip program for rebels. The record of these efforts has been mixed, and even the most trusted proxies vetted by the United States and its allies have displayed very limited potential. A more interventionist strategy should make use of a broader range of proxies than the current approach, which relies too much on the Kurdish-controlled Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) alliance, while recognizing that vetted Free Syrian Army-brand groups will have only limited efficacy and will initially operate in the shadow of the larger, jihadist groups. A U.S.-led military campaign should prioritize the following strategic aims:

- Weaken the Syrian government’s military forces.

- Reintroduce norms of warfare by punishing parties who commit war crimes.

- Protect civilians through siege relief and other means, in pursuit of a war strategy that makes civilian well-being a core interest.

- Promote a core political commitment to a pluralistic Syria where all groups and ethnicities, including the secular, share common rights.

- Preserve Syria’s state and institutions, including the military. Further wreckage to Syria’s institutions and infrastructure must be condemned, punished, and when possible, prevented.

- Equalize the stalemate so that negotiations become appealing to all sides. Achieving balance would be difficult, requiring military strikes or withholding of military aid to any party that aspires to outright victory rather than negotiated settlement.

Supporters of military intervention—including the intervention already under way—must be honest about the risks and limits. American allies in Syria are unreliable, with limited reach. Extremists and jihadists, like government forces, have some popularity and legitimate constituencies. Current U.S. policy has unintentionally strengthened the Syrian government, as well as Islamic State and Nusra; a more active military intervention would weaken those parties in some ways but probably strengthen them in others. An honest policy must acknowledge that there will be collateral benefits to parties that the United States does not want to strengthen, but can calibrate force so that benefits of the policy outweigh the costs.

A rejuvenated military campaign would be a work in progress, but initial tactical steps that would help achieve America’s strategic aims include:

- End regime starvation sieges, such as the ones currently under way in Deraya, Madaya, Moadhamiya, and Eastern Ghouta.

- For symbolic reasons, intervention should also end starvation sieges by Islamic State in Deir al-Zour and by the Free Syrian Army in Foua and Kafraya.

- Air power, special forces, and proxies should expand and defend safe access to rebel Aleppo.

- Short of full safe havens and no-fly zones, the United States can offer incremental protection to civilian areas in the south, center, and north of Syria. Already there are considerable in-gatherings of civilians, for instance, along the Jordanian and Turkish borders. The risks of a heavy civilian concentration already are present; U.S. protection—even if incomplete—could save many lives.

- The United States should pressure the Syrian Democratic Forces, its preferred proxy, to stop attacking vetted Free Syrian Army groups and to cooperate with them. The United States should withhold arms deliveries and air strikes for the Syrian Democratic Forces any time the Syrian Democratic Forces attack Free Syrian Army groups. It should also provide air strikes to Free Syrian Army groups with equal speed and intensity as it does for the YPG/SDF. Where it lacks the capacity to provide air cover to vetted Free Syrian Army units, it should quickly address technical obstacles. It should introduce into the warzone the capacity to shoot down planes, through whichever means the U.S. military finds most effective, whether special forces from the United States or allies like Jordan and United Emirates, or tightly controlled deliveries of anti-aircraft missiles to vetted proxies.

- The United States should make proportionate retaliatory air strikes for any indiscriminate attacks by the Syrian government or the Russian military on civilians and infrastructure, especially hospitals, clinics, and civil defense.

- The U.S. military and its vetted proxies should employ enough force to protect displaced camps and civilian neighborhoods.

- Islamic State and government forces should bear the brunt of U.S. action, but air strikes and special operations should continue to target anti-regime extremists such as Nusra when Nusra threatens U.S. allies. It is not necessary to engage in total war against all the extremist parties to the conflict—limited, occasional strikes will make it harder for all parties to commit war crimes and will inject uncertainty into the calculations of militias.

- Shoot down some Syrian government planes and helicopters. End the long and disingenuous debate about whether to give rebels surface-to-air missiles by addressing the umbrella concern: indiscriminate bombardment of civilians from the air. Even occasional U.S.-orchestrated strikes against regime air assets—always over areas where U.S. forces have given prior notification to Russia, to be sure there are no accidental strikes against Russian pilots—will force the Assad government to shelf its approach of massive bombardment of rebel-held civilian areas.

Any increased military action would, of course, be complicated, and would come with risks and unintended consequences. Already, the United States is deeply and expensively involved, with special forces on the ground inside Syria, an extensive covert program that works with vetted rebel groups in northern and southern Syria, a more limited overt train-and-equip program, and a war against Islamic State, largely consisting of air strikes. In practice, most of the vetted rebel groups are small and in many contexts survive at the pleasure of Nusra. They collaborate with Nusra in battles against the Syrian government. Already, many of these groups are engaged in existential battles against the Syrian government on one side, and Islamic State on the other. Their relationship with Nusra is rocky; the Al Qaeda affiliate has a tendency to destroy or marginalize Free Syrian Army groups that display too much independence. If the United States escalates its involvement, the Nusra Front might escalate its own campaign to eradicate alternative rebel groups. The U.S. military and its allies will have to use their assets to forestall a Nusra offensive—for instance, with extensive air strikes and close air support for vetted MOC groups. If U.S.-backed groups are strong enough, well-armed, and given close air support, Nusra will be less likely to try to wipe them out. But in the long run, Nusra’s agenda will never dovetail with America’s, and it is a fool’s game to expect beleaguered nationalists to defeat Al Qaeda in Syria unaided. In the long haul, Free Syrian Army groups are endangered species unless their foreign sponsors up the ante; better an orchestrated attempt to preserve their seat at the table than a decision to watch them slowly get destroyed.

The ground ally that the United States trusts the most is the YPG, a Kurdish militia in northern Syria that is an outgrowth of the PKK, a Kurdish separatist group in Turkey. The YPG has fought effectively in some instances, including against Islamic State; it also retains close ties with the Damascus government and with Russia. Many anti-government militia leaders in northern Syria, including majority Arabs and some minority Kurds, distrust the YPG and accuse it of ethnic cleansing against Arabs. The YPG has some Arab allies in its Syrian Defense Forces umbrella, but they are not equals in the Syrian Democratic Forces; they operate as junior partners under Kurdish control. U.S. support for the YPG has alienated Turkey, a necessary partner in America’s Syria policy. There are other complications as well. In the south, American support has helped build a formidable rebel force on paper, but the Kingdom of Jordan has only allowed the Free Syrian Army in southern Syria to exist so long as it operates in narrow limits imposed by Jordan, which is more eager to limit its refugee population and contain Syrian government reprisals against Jordan than it is to see a resolution of the Syrian war.

The United States must deal with the often counterproductive and frequently irksome maneuvers of supposed allies who often compete with each other as well as with Washington: the list of troublesome friends includes but is not limited to all the vetted Syrian militias, the non-jihadi unvetted rebels, Ahrar el Sham, Turkey, Jordan, Israel, Lebanon, Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates and Qatar.

As it is, American policy is subjected to these problems. A more active intervention will persuade many of these reluctant allies to get in line because there will be a more robust policy to fall in line behind. American military initiative will benefit from a multiplier effect. Today, all of America’s partners follow independent military policies in Syria. With an armed hand on the tiller, the United States can demand that its allies actively support U.S. strategy, and cease supporting groups who oppose it.

Military intervention should establish some protected areas that would be shielded from regime bombardment and shelling—in Aleppo and Idlib province, and in the southern front area near the Jordanian border. U.S. or allied rebel forces would then have to use infantry in those protected areas to drive out Islamic State, Nusra, and other opportunistic jihadi infiltrators. Some Nusra footsoldiers might switch sides if they see momentum, money, and weapons flowing to a reinvigorated nationalist grouping. Military intervention should also protect camps, such as the areas where approximately 165,000 internally displaced Syrians at the end of May were weathering an Islamic State assault, according to Human Rights Watch, but were unable to flee to safety in Turkey because Turkish authorities had sealed the border.

Finally, the United States should declare certain areas off-limits to bombing, and reserve the right to shoot down any planes or helicopters that bomb in those areas. Those areas, at the start, should be limited to key corridors around Idlib and Aleppo where civilians are concentrated. The United States should provide clear maps to the Syrian government and Russia of the protected areas. These protected zones will not benefit from full no-fly coverage. But planes and helicopters that drop ordnance, as well as mortar crews, will be subject to reprisal. Even occasional retaliation, with a few aircraft shot down, will provoke a major reduction in indiscriminate bombing, which has become a favored Syrian government technique because it carries almost no cost. Similarly, siege warfare has been very economical for the government, as well as for some rebel groups that profit from smuggling, but would become much less attractive if siege chokepoints were subject to direct U.S. targeting, or U.S.-coordinated proxy assaults.

Prong 3: Pressure

On the political front, the United States should continue and intensify its recent approach. Washington should maintain the open stance that Kerry has created with the Russians. It can open the tent to more deeply engage Iran, Saudi Arabia, and Turkey. Success requires a clear definition of the political aims: to reduce human suffering, increase stability in Syria and the region, and raise the slim chances of a negotiated settlement that preserves the integrity of the Syrian state. Only equilibrium allows for serious negotiation. If either side believes it can win outright, it will not entertain concessions.

The United States has done an impressive job pressuring its own clients and allies inside Syria—the relatively weak Free Syrian Army battalions and their negotiating bodies, most recently the Saudi-backed High Negotiations Committee (HNC). It has invested considerable, effective pressure negotiating on multiple fronts with the Syrian government and with Russia. Washington has effective open and backchannel discussions with Iran, and it has engaged in diplomacy though civilian as well as military-military channels with Iraq, Turkey, and the Arabian peninsula monarchies. Now, the United States should ratchet up its pressure on all relevant parties, not just its clients. In every forum, the United States should repeat its goals often: a pluralistic Syria, with rights for all groups, including government supporters, within Syria’s borders, and an intact state with national institutions.

The Syrian government should live in fear of U.S. retaliation for sieges of civilians, and for indiscriminate bombing. So should rebel groups—and not just the worst of the worst.

The Syrian government should live in fear of U.S. retaliation for sieges of civilians, and for indiscriminate bombing. So should rebel groups—and not just the worst of the worst. The United States is already striking Islamic State, and occasionally Nusra. It should not hesitate to bomb other jihadist factions, including Ahrar el Sham, if those groups murder civilians or harass minorities. Such symbolic targeting sends a clear message to all parties to the conflict.

If the increased U.S. involvement leads to a shift in the status quo while the conflict continues, the United States can claim to have done its best—and should be able to point to a discernible number of lives saved. That alone should justify the involvement.

The Politics of the Policy

How America explains its revamped policy is almost as important as the calibrated increases in American activity. An American escalation in Syria would be best served by a political strategy to set realistic domestic expectations, prepare American constituencies for the risks, and maximize the dividends from foreign allies, including Syrian factions. In terms of politics, polling and common sense suggest that the U.S. public does not want another reckless military intervention like the U.S. invasion of Iraq. That does not mean that the United States must swing to an isolationist extreme—only that interventions must have worthwhile aims, and that the president must do the work to persuade the American public that sacrifices of blood and treasure will serve a core U.S. national security interest.

American leaders can begin with a more honest narrative about Iraq, whose lessons about hubris have been distorted to justify questionable choices. America invaded Iraq on false pretenses in 2003, and ignored the predictions of its own government experts who counselled a much larger occupation force and predicted most of the problems that came to pass when the U.S. occupation authority dismantled Iraqi state institutions. A casual, almost cavalier, dismantling of Iraq followed, which led, not surprisingly, to a long civil war, the intensification of sectarianism, and the sprouting of groups including the parent organization of Islamic State. The United States failed to honor its own legal obligation to provide security as the occupying power in Iraq. By the time President Obama came to office, a sectarian Shia government was busily destroying any potential challenges to its authority, and no longer wanted a U.S. military presence. Washington had little choice—it had uncorked the sectarian genie and destroyed the state institutions that might have prevented Iraq from fragmenting along sectarian and ethnic lines. Once a sovereign Iraq did not want to renew its agreement with the U.S. government, America had to pull out most of its military forces. Today’s war against Islamic State, and much of the violence in Syria, has its roots in U.S. acts in Iraq. To disavow responsibility today is morally obtuse and strategically self-defeating.