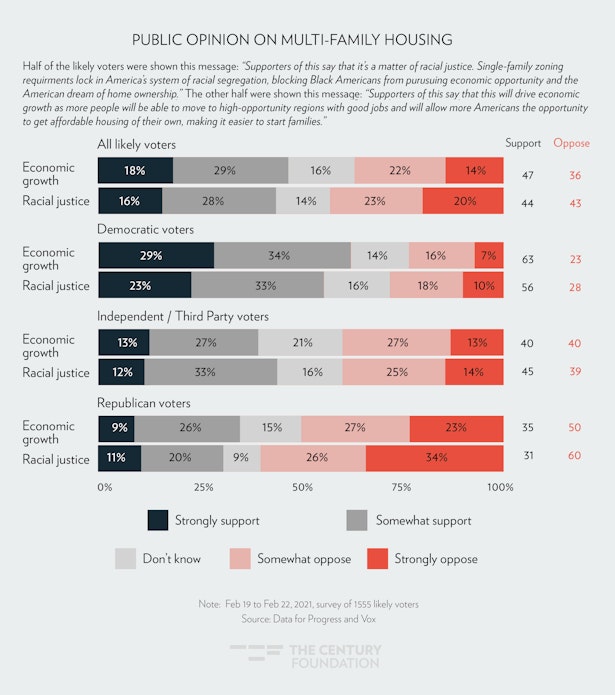

In the 2020 presidential campaign, Joe Biden, defied the pundits who wrote him off by returning again and again to a few key themes: racial justice, respect for working-class people, and national unity. He said he would seek to heal the soul of the country, which had been damaged by Donald Trump’s embrace of racism. As a proud product of Scranton, Pennsylvania and the University of Delaware, Biden said he would value the dignity of working people and not look down on anyone. And he said that as president, he would seek to unify a politically polarized country by exhibiting decency and empathy toward all and representing the people who voted against him as much as those who voted for him.

As President Biden builds off the success of the American Rescue Plan Act and charts a course forward, how can he—working with the new Congress—best deliver on those three longer-term promises? Perhaps no single step would do more to advance those goals than tearing down the government-sponsored walls that keep Americans of different races and classes from living in the same communities, sharing the same public schools, and getting a chance to know one another across racial, economic and political lines.1

Economically discriminatory zoning policies—which say that people are not welcome in a community unless they can afford a single-family home, sometimes on a large plot of land—run counter to American ideals and yet are pervasive in America. In most U.S. cities, zoning laws prohibit the construction of duplexes, triplexes, quads, and larger multifamily units on at least three quarters of available land.2 In the early twentieth century, cities had adopted explicitly racist zoning policies that prohibited Black people from living in white communities. But after racial zoning was struck down by the U.S. Supreme Court in 1917, municipalities replaced their race-based policies with economic zoning, which continues to discriminate against low-wage families—many of them families of color—to this very day.3

After racial zoning was struck down by the U.S. Supreme Court in 1917, municipalities replaced their race-based policies with economic zoning.

These policies—coupled with private practices such as racial steering by real estate agents4—carry an ugly underlying message: some people are better than others because of how much money they make or the color of their skin. In a country where 75 percent of students attend neighborhood public schools, these local housing ordinances also serve to divide American school children into separate cohorts—with one being significantly whiter and wealthier.5 No single step could be more important to healing America’s soul and uniting the country than providing more children with the opportunity to go to school with classmates of different racial, ethnic, religious, and economic backgrounds where they can learn together what it means to be an American.

Local government bans on duplexes, triplexes, or apartment buildings not only drive racial and economic segregation, they also exacerbate two other challenges the Biden administration has identified as critical: the housing affordability crisis and climate change.

Economists from across the political spectrum agree that zoning laws that ban anything but single-family homes artificially drive up prices—for houses in exclusive neighborhoods and for multi-unit rental dwellings alike—by limiting the supply of housing that can be built in a region, just as surely as OPEC constricting the production of oil drives up oil prices.6 At a time when the COVID-19 pandemic has left many Americans jobless and people are struggling to make rent or pay their mortgages, it is incomprehensible that ubiquitous government zoning policies would make the housing affordability crisis worse by driving prices artificially higher.7

Likewise, there is widespread agreement that laws banning the construction of multifamily housing promote damage to the planet.8 Single-family-exclusive zoning pushes new development further and further out, which lengthens commutes and increases the emissions of greenhouse gases. Indeed, the United Nations Environmental Program has recommended removing limits to multifamily housing as an important strategy for reducing emissions.9

What keeps these harmful policies in place? For decades, powerful “not in my back yard” (NIMBY) forces have thwarted reform and kept exclusionary policies in place. Because the voices of upper-middle-class, mostly white homeowners are amplified in zoning discussions, a political consensus congealed around the idea that economically discriminatory zoning, no matter how damaging, is politically untouchable.10 Lee Anne Fennell of the University of Chicago Law School notes that economically discriminatory zoning has become “a central organizing feature in American metropolitan life.”11

Recently, though, that political consensus has been upended. Reformers in cities such as Minneapolis and states such as Oregon have adopted sweeping reforms to end single-family-only zoning.12 California, too, has enacted extensive reforms that allow the construction of small living spaces (known as “accessory dwelling units”) next to single-family homes in areas previously zoned exclusively for single-family residences.13

At the national level, Biden made the judgement that it was politically possible to endorse federal reform of exclusionary zoning, which he did in 2020, when he called for enactment of legislation proposed by Cory Booker and James Clyburn.14 Moreover, Donald Trump’s attempt to use that issue to win over “suburban housewives of America”—at a time many people were rejecting racism in the wake of George Floyd’s murder—fell flat.15 Invoking fears of increased crime and reduced property values—claims that have been largely debunked by research—proved unsuccessful.16

Developments that followed the 2020 election have further accelerated the hopes of those who would like to see reform of economically discriminatory zoning. President Biden appointed Representative Marcia Fudge (D-OH) as secretary of the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD), which excited advocates who care about reducing racial and economic segregation. In the education arena, Fudge was the chief congressional sponsor of the Strength in Diversity Act, the leading legislative vehicle for supporting local school integration efforts. And, as mayor of Warrensville Heights, Ohio, an inner-ring suburb of Cleveland, Fudge successfully championed an effort to bring families of different economic backgrounds together to live in the community.17 Biden also appointed Susan Rice head of the Domestic Policy Council, with racial justice declared as her central goal.18

Within days of taking office, President Biden also issued executive orders indicating his intent to reinstate two important rules that the Obama administration promulgated and the Trump administration repealed—the 2015 “Affirmatively Furthering Fair Housing” rule that implemented an important element of the Fair Housing Act, and the 2013 rule interpreting the Fair Housing Act’s “disparate impact” rule that unjustified rules with discriminatory impact are illegal even absent discriminatory intent.19 (Both of these rules, which impact exclusionary zoning, are discussed in much greater detail below.) The American Rescue Plan Act just signed into law also invests billions of dollars in funds for emergency rental assistance, assistance to homeowners trying to pay mortgages, and housing for the homeless.20

The leadership of key housing committees are also champions of equity and opponents of exclusion. Representative Maxine Waters (D-CA), a longtime leader on issues of racial and economic equity, retained her chairmanship of the House Committee on Financial Services (which has jurisdiction over housing). And Senator Sherrod Brown (D-OH), a longtime champion of the dignity of American’s multiracial working class, is the new chair of the Senate Committee on Banking, Housing, and Urban Affairs.

There are many possible paths forward to make housing more affordable and residential areas more integrated. These include full funding of the Housing Choice Vouchers program and the American Jobs Plan’s proposal to invest $213 billion in housing as part of a push to rebuild America’s infrastructure.21 Reform must also include the subject of this report—reducing exclusionary zoning policies that are a central source of segregation and affordability concerns. Pointing to local zoning laws, the New York Times editorial page has noted, “Housing is one area of American life where government really is the problem.”22 Biden’s American Jobs plan itself acknowledges this, and includes an exciting new $5 billion competitive grants program to encourage jurisdictions to reduce exclusionary zoning.23

Beyond this grants program, how can federal leaders capitalize on this moment to bring about meaningful change to exclusionary zoning? What steps could the Congress and Biden administration take to curtail zoning policies that cause so much harm?

In December 2020, The Century Foundation (TCF) and the Bridges Collaborative—an initiative for school and housing integration—assembled more than twenty of the leading thinkers from across the country to discuss these issues. The group included elected officials, civil rights activists, libertarians, and housing researchers. (See list of participants in the appendix.) This report is informed by the collective wisdom of the group—though individual participants may object, perhaps strenuously, to a number of particular conclusions in this report and are in no way responsible for them.

The first part of this report explains the ways in which the U.S. Constitution provides federal authority to reduce harmful local zoning ordinances and reviews the evidence on three key reasons why the federal government should exercise its authority: (1) to reduce economic and racial segregation and discrimination; (2) to improve housing affordability and health; and (3) to fight climate change.

The second part briefly reviews the experiences in several cities and states seeking exclusionary zoning reform, with a focus on Minneapolis, Oregon, California, and Virginia. This section asks what lessons local and state experiences hold for federal reform on questions such as how to build effective coalitions for reform; how to address the possibility that exclusionary zoning reform might inadvertently accelerate gentrification and displacement; and whether reforms should seek change that is incremental or bold.

The third part outlines eight leading federal reform ideas, which include efforts to provide incentives for state and local reform through new funding carrots, attaching conditions to the receipt of existing federal funding, and employing a private right of action against government discrimination in federal court. Some of these ideas have already been endorsed by President Biden, others have not.24 The report discusses the advantages and disadvantages of each of these reforms based on three criteria: their potential effectiveness in bringing about change; their political viability (including the possibility of bipartisan support); and their constitutional viability to withstand possible challenges in federal court. Any of these approaches could be incorporated into key legislative vehicles for the Biden administration, including infrastructure and climate change bills.

The fourth and final part of the report concludes with recommendations on the best paths forward for the Biden administration and Congress.

Why Should the Federal Government Get Involved in Local Exclusionary Zoning?

Zoning decisions are typically made at the local level, so does the federal government have the authority to enter into this sphere? And if it does have such authority, should it exercise it?

Federal Authority on Zoning Policies That Run Counter to the National Interest

Although states have delegated considerable authority over zoning matters to localities, state and local control in this realm has never been unlimited. The U.S. Constitution has long provided federal courts and the U.S. Congress with the authority to intervene in zoning questions when localities have abused their power.

In a landmark 1917 decision, the U.S. Supreme Court struck down local racial zoning laws that prohibited Black people from buying in predominantly white areas as a violation of the Equal Protection Clause.25 In 1968, Congress employed its powers to regulate interstate commerce to pass the Fair Housing Act, which bars discrimination in housing.26 The act, in turn, has been used on numerous occasions to strike down zoning policies that hurt people of color.27

Congress has intervened in local zoning in other spheres as well. The Telecommunications Act of 1996, for example, “allows the federal government to override local land-use regulations that impede the siting of cell phone towers.”28 The Religious Land Use and Institutionalized Persons Act of 2000, passed unanimously by Congress, came in response to an outcry from religious institutions that had faced discrimination when local governments denied zoning approval. Under the federal law, religious institutions can bring suits and receive injunctive or declaratory relief.29

The federal government also has broad authority under its spending powers to place conditions on the use of funds, so long as those conditions are related to spending and are not unduly “coercive.”30 Because the federal government has an interest in ensuring that its spending advances national goals, it can place conditions on related spending that implicates local zoning laws. For example, in 2020 the House passed the Yes In My Back Yard (YIMBY) Act to require recipients of federal Community Development Block Grants to report on their efforts to reduce exclusionary zoning. (The bill has not yet passed the Senate.)31

That Congress has a right to ensure that its spending advances its goals—including on the question of zoning—is a principle that is widely shared by conservatives as well as liberals. Ryan Streeter of the American Enterprise Institute, for example, suggests that the federal government has an interest in reducing restrictive zoning because it drives up housing prices, which in turn increases federal spending. “Tying federal funding to how well communities are matching housing supply with demand is sensible policy,” he says. “Localities expect the federal government to pay for considerable social welfare costs in their communities. Asking them to do their part by not driving up housing costs on lower-income families is a reasonable policy goal.”32

Why the Federal Government Should Exercise Its Authority

If the federal government clearly has the authority to reduce economically and racially discriminatory zoning policies, it also has several very important reasons to do so: to enhance opportunities, particularly for low-income families and families of color; to reduce segregation and unify the country; to make housing more affordable by increasing its supply; to reduce the negative health effects of overcrowded housing; and to improve the quality of the environment.

The Federal Interest in Enhancing Opportunity and Social Cohesion

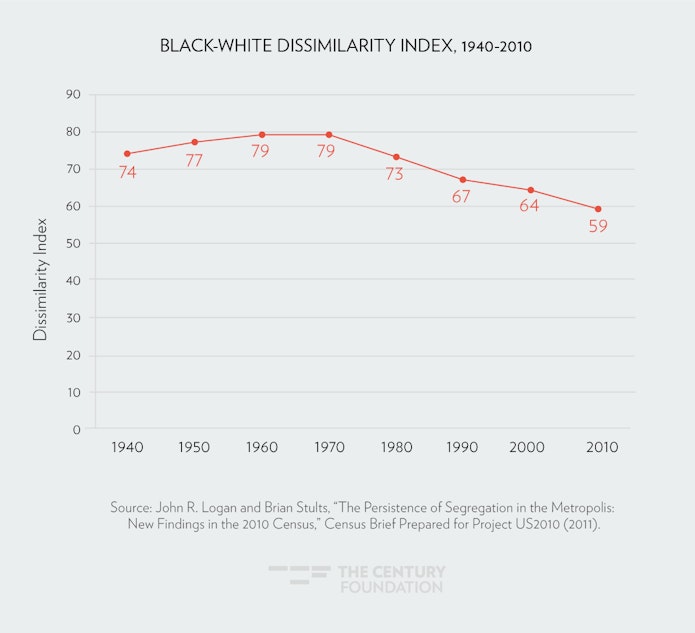

Low-income families, many of them families of color, are increasingly cut off from access to safe neighborhoods with strong public schools. The good news is that the the 1968 Fair Housing Act cleared the way for many middle-class Black people to escape ghettos, and racial segregation has slowly declined over the past half century. As a result, the Black–white dissimilarity index (in which 0 is perfect integration and 100 is absolute segregation) has shrunk from a high of 79 in 1970 to 59 in 2010, according to an analysis of Census data. (See Figure 1.) A more recent study found that between 2010 and 2014, Black–white segregation declined in 45 of 52 metropolitan areas.33

Figure 1

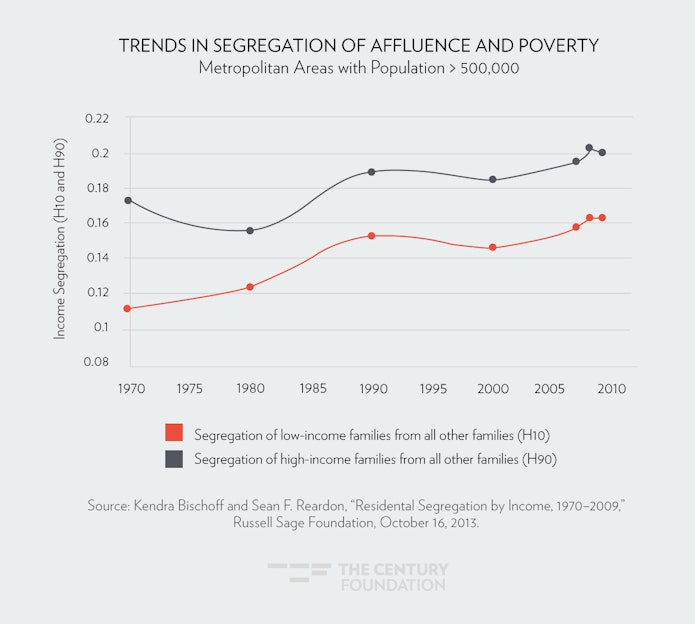

But the bad news is that, in recent decades, as Robert D. Putnam, a political scientist at Harvard, notes, “while race-based segregation has been slowly declining, class-based segregation has been increasing.” In fact, Professor Putnam says, “a kind of incipient class apartheid” has been sweeping across the country.34 In 2015, in a panel discussion with Putnam, President Barack Obama observed that “what used to be racial segregation now mirrors itself in class segregation.”35 Despite the existence of a small number of high-profile gentrifying, mixed-income urban communities, the number of families living in economically segregated neighborhoods has more than doubled since 1970, and indexes of economic dissimilarity are on the rise.36 (See Figure 2.)

Figure 2

Government-sponsored economic discrimination matters a great deal because where people live in America dramatically shapes their opportunities and those of their children. Neighborhoods determine one’s access to transportation, employment opportunities, decent health care, and good schools. In a much-discussed 2015 study, Raj Chetty of Harvard University and his colleagues looked at how well children who relocated from high-poverty to low-poverty areas through the federal “Moving to Opportunity” program did as adults. They found that, compared with a control group that wanted to move but could not because of the program’s limited number of spaces, children who moved before age 13 were 16 percent more likely to attend college between the ages of 18 and 20 and earned 31 percent more as adults.37

Consider KiAra Cornelius, an African-American single mother of two, who works as a claims analyst at United Healthcare, and who was interviewed for a Century Foundation report on housing integration.38 For many years, she lived in a tough neighborhood in south Columbus, Ohio, where she forbade her school-aged children from walking the few blocks to their grandmother’s house because she worried that they might “get crossed up” in gang-related activity. She wanted to move to a suburban neighborhood with less crime and better schools.

But Cornelius found she couldn’t afford to live in most of Columbus’s suburbs, as those towns have erected largely invisible barriers, specifically to keep out families of modest means. State-sponsored discrimination in communities like these forbid developers from building duplexes, triplexes, or apartment buildings. Some require that when multifamily units are allowed, they must have expensive features, such as special trims or facades. Some towns go further and forbid anyone who cannot afford a large home sitting atop an expansive plot of land. All these requirements are designed to keep families like Cornelius’s out.

Economically discriminatory zoning hurts all people of modest means, but it hits African-American and Latino families particularly hard—an important point to recognize as America belatedly begins to reckon with its history of racial oppression. To purchase a single-family home, it is necessary to have accumulated enough wealth for a down payment. Yet because of historic and contemporary discrimination, median Black household wealth (savings accumulated over time) is just 10 percent of median white household wealth. (Median Black annual income, by contrast, is 60 percent of median white income). HUD secretary Marcia Fudge has identified the challenge Black buyers have coming up with down payments as the biggest impediment to Black homeownership.39 So, exclusionary zoning that limits a neighborhood’s housing stock to single-family homes is especially likely to exclude Black families, perpetuating racial segregation and the racial wealth gap.

While racial segregation is particularly harmful to Black Americans, it also divides and polarizes Americans politically. Much has been made of the ideological divide between rural and urban areas, but researchers have found that, even within metropolitan areas, Democrats and Republicans often cluster in different communities, where they no longer converse with and come to know as neighbors and friends those who have different ideological outlooks.40 Researchers have found that more racially segregated cities tend to have the highest levels of political polarization.41 Racial segregation reduces empathy across racial lines and makes it easier for politicians to demonize others.

The Federal Interest in Making Housing More Affordable and Communities Healthier

Exclusionary zoning not only blocks the opportunity of families to live in neighborhoods rich with opportunity; it also stacks the deck against working families by making housing in entire metropolitan areas less affordable. When a community says that available land can only be used for single-family homes on large lots, it artificially limits the supply of housing and increases housing costs. By contrast, if builders (or existing homeowners) were allowed to subdivide houses into duplexes or triplexes, a community could double or triple the number of housing units available to potential consumers, making housing more affordable for everyone.

Exclusionary zoning stacks the deck against working families by making housing in entire metropolitan areas less affordable.

Allowing government to drive up home prices makes little sense when the nation is facing what the Urban Institute has called “the worst affordable housing crisis in decades.” Going back to passage of the United States National Housing Act of 1937, public policy has suggested that families should spend no more than 30 percent of their pre-tax income on housing. Yet, according to a recent report of Harvard’s Joint Center for Housing Studies, nearly half of all renters (21 million Americans) spend more than that—double the proportion in the 1960s.42 While some of this affordability crisis can be chalked up to wage stagnation, it is also true that rents have been rising faster than other costs for decades.43 At its extreme, the housing affordability crisis leads to eviction and homelessness.

Zoning policies that limit housing supply and drive up housing costs have made life miserable for people like Janet Williams.44 A 29-year-old Black single mother who is employed as a community health worker in Columbus, Ohio, Williams frequently faces a tough dilemma when her meager paycheck arrives. She says that, on several occasions, it’s gotten “to the point where I had to choose if I wanted to pay for groceries or if I wanted to pay rent or if I wanted to pay for my gas and electric or . . . to pay childcare.” Williams, a mother of two, explains that sometimes her hand is forced. “I’ve had times where, if I didn’t pay my rent, the next day I was going to have an eviction filed.” On those occasions, “the whole check goes to my rent,” and while she waits for the next paycheck to arrive, she may have to tell her kids, we will “not have hot water and not have the electric working.”

Williams did all the right things, according to American social expectations, including taking on $70,000 in student debt to get a bachelor’s degree in human services from Ohio Christian University, awarded in 2019. Her income now is just above what would qualify for food stamps, she says, so “it’s on me to put groceries in the house.” She hates owing money, so when she gets a windfall, like a pandemic stimulus check, she says she uses it to pay down her credit card debt. But she’s frustrated that high housing costs mean she is constrained to a neighborhood where her kids don’t feel safe. “I can’t tell you how many times we’ve seen the police outside of our window,” she says. To avoid dangers in the neighborhood, she says, “we pretty much keep to ourselves. We don’t really do too much.” What really aggravates her is that even in her crime-ridden East Columbus neighborhood, the rent is so high that “every month is deciding what’s going to get paid.”45

The high cost of housing spurred on by exclusionary zoning also exacerbates health problems, an issue highlighted by the COVID-19 pandemic. While some early reporting focused on the idea that housing density spreads COVID-19, in fact, the studies show that it’s overcrowding—too many people living in the same apartment or home—that presents the largest health concerns. Some small towns had high infection rates because individual housing units were crowded, with three or four families living in a single home, while some very dense cities, such as Hong Kong, Seoul, and Singapore, have contained the spread of COVID-19 because units themselves are not overcrowded.46

The Federal Interest in Slowing Climate Change

Exclusionary zoning policies such as those that limit development to detached, single-family houses promote suburban sprawl, which means longer commutes, more cars on the road, and more greenhouse gas emissions.47 Moreover, as a general rule, because multifamily units have fewer exterior walls, they are easier to heat and cool, and are more energy efficient, than are single-family homes.48 Families should always have the freedom to make personal choices about their living arrangements, but as the planet heats up, it is odd that government—which is fighting in all sorts of arenas to reduce greenhouse gasses—would explicitly prohibit construction of the most environmentally friendly options.

Environmentalists have joined with civil rights activists and affordable housing advocates to make climate change a third major prong in the campaign to reduce exclusionary zoning.

Environmentalists have joined with civil rights activists and affordable housing advocates to make climate change a third major prong in the campaign to reduce exclusionary zoning.49 Moreover, this push could have broad public support. In 2020, the Pew Research Center found that 68 percent of voters said climate change was a very or somewhat important issue to them.50

Exclusionary Zoning Reform in States and Cities

As federal policymakers consider what they can do to reduce exclusionary zoning, it is important to draw lessons from the experiences of states and localities in tackling the problem. This section of the report examines: (1) longstanding initiatives to rein in exclusionary zoning in places such as New Jersey and Massachusetts; (2) recent reforms in Minneapolis, Oregon, California, and Virginia; and (3) lessons for federal policymakers on both the substance and the politics of zoning reform.

Longstanding State Efforts to Reduce Exclusionary Zoning

A number of states have for decades taken important steps to try to reduce exclusionary zoning in residential communities.51 In 1969, for example, the state of Massachusetts passed an “anti-snob” zoning law that empowered the state to alter local zoning laws in communities where less than 10 percent of housing stock is deemed affordable; recently, an effort to overturn the law through a statewide referendum was opposed by 58 percent of voters.52 Another leading example is New Jersey, where in 1975, the state Supreme Court ruled in Southern Burlington County NAACP v. Mount Laurel that zoning laws that have the effect of excluding low-income families from a municipality violate the state constitution. The court ruled that localities have an affirmative obligation to provide their “fair share” of moderate and low-income housing.53 After the state dragged its feet on action, the court ruled again on the matter in Mount Laurel II (1983), which established an enforcement mechanism known as a “builder’s remedy,” by which developers can bring suit against a municipality to change zoning so long as 20 percent of the development is dedicated to low- or moderate-income homes. Although implementation of the Mount Laurel decision has often proven difficult, thousands of low-income families have been allowed to move to low-poverty neighborhoods as a result of the decision and have benefited greatly.54

Recent State and Local Efforts in Minneapolis, Oregon, California, and Virginia

The circle of states and localities seeking to reduce exclusionary zoning—or even end single-family-exclusive zoning altogether—has expanded recently in a way that would have astonished reformers in earlier generations who thought NIMBY forces were unbeatable. In 2018, observers were stunned when the city of Minneapolis voted to do something long considered impossible in American politics: end single-family-exclusive zoning in an entire city.

A city of 425,000 residents, Minneapolis once had one of the most stringent zoning policies, having banned duplexes, triplexes, and larger apartment buildings from 70 percent of its residential land; in New York City, by comparison, just 15 percent of residential land is set aside for single-family homes. The new long-term plan passed by the city council in 2018—Minneapolis 2040—paved the way to up-zone the city to allow two- and three-family buildings on what had previously been single-family lots, tripling the potential number of housing units in the city.55 Once Minneapolis broke the log jam, a second major victory followed in 2019, when a bipartisan group of legislators in Oregon passed the nation’s first statewide ban on single-family-exclusive zoning. The provision applied to all cities with a population of at least 10,000 residents, and overcame the strong opposition of the League of Oregon Cities.56

In California, meanwhile, state senator Scott Wiener came close to passing a dramatic bill that would have allowed the state to override local zoning restrictions in order to permit four-to-eight-story buildings near mass transportation stops.57 Although the legislation did not pass, a number of related bills did, including one to allow “in law-flats,” also known as Accessory Dwelling Units (ADUs) in areas zoned for single-family houses. The change, notes Ingrid Gould Ellen of New York University’s Furman Center, “essentially doubles the potential housing stock” in the state.58 Virginia, likewise, has begun a conversation about reducing exclusionary zoning, led by state delegate Ibraheem Samirah, who has emphasized the ways in which single-family-exclusive zoning leads to sprawl and more traffic congestion.59

Substantive and Political Lessons for Federal Policymakers from State and Local Experiences

What can federal policymakers take away from these state and local experiences in exclusionary zoning reform? One lesson is that federal intervention is both necessary and possible. It is necessary because, while there have been some policy successes, in general, states cannot do the work alone. As Tom Loftus of the Equitable Housing Institute finds, even in the states with the most forward-looking efforts to curb exclusionary zoning need more support. Reviewing the effects of longstanding state statutes to curb exclusionary zoning in places such as Massachusetts and New Jersey, Loftus concludes that while they’ve made progress, housing production has still been stymied and “those state statutes have not been able to prevent worse than average housing affordability problems in their states.”60 At the same time, very recent efforts at reform in places such as Minneapolis and Oregon to eliminate single-family housing restrictions suggests that federal reform may be possible, because NIMBY forces are not as powerful as they once were.

More specific lessons also emerge about how federal policies might be shaped. On a substantive level, the fact that states have grappled with such difficult issues as what constitutes a community’s “fair share” of affordable housing means that federal policy makers will not have to start from scratch in coming up with appropriate metrics for outcomes. Another substantive lesson, given the limited impact of some state reforms, is that deferring to state legislatures to implement reductions in exclusionary zoning may be a less effective way of bringing about change than giving plaintiffs a private right of action to compel results by judicial injunction.61

Finally, federal policymakers can draw a number of specific (and hopeful) lessons from the very recent successful efforts to curtail exclusionary zoning in places such as Minneapolis, Oregon, and California. Among the critical lessons: (1) reform of exclusionary zoning can make for unlikely coalitions; (2) positive messaging and framing can make a difference; (3) confronting concerns about gentrification and displacement intelligently can win support; and (4) being bold can make space for more modest reforms.

Unlikely Coalitions

One lesson for defeating exclusive zoning is to be creative in forging the sometimes unlikely political coalitions for reform that can include a variety of “groups that don’t normally work together,” says Wiener.62 These groups include liberal stalwarts—civil rights, labor, environmentalists, affordable housing activists, young people, and seniors63—but also employers, libertarians, builders, and rural white residents.64

In Minneapolis, civil rights activists became engaged in zoning discussions and pointed out that the maps that had redlined majority-Black areas as ineligible for financing in decades past overlapped significantly with maps that distinguished between single-family and multifamily zones.

In Minneapolis, civil rights activists became engaged in zoning discussions and pointed out that the maps that had redlined majority-Black areas as ineligible for financing in decades past overlapped significantly with maps that distinguished between single-family and multifamily zones. “Zoning is the new redlining,” said Kyrra Rankine, an activist who pushed for reform. Organized labor emphasized that single-family-exclusive zoning exacerbates housing unaffordability; union members testified that, because the city had become unaffordable, they had to move to blue-collar suburbs and take two buses to get to work, which was a major hardship.65 The building trades expressed their interest in pro-growth reforms that create jobs.66 Environmentalists who know that exclusionary zoning contributes to climate change have been part of the coalition for reform, as has the American Association of Retired Persons (AARP). The group has pushed for more flexibility to build backyard cottages, both to provide older homeowners with a new source of rental income and to allow grandparents to live close to children and grandchildren (spawning the so-called PIMBY movement, “parents in my back yard”).67

In California, a coalition for zoning reform included not only civil rights and labor groups, but young middle class white residents who are part of the “yes, in my back yard” (YIMBY) movement. Brian Hanlon, executive director of California YIMBY, explained that, among upper-middle-class millennials in places such as San Francisco and Los Angeles, the most pressing question is: “I went to a good school and can’t afford rent? WTF?” Allied with these millennials are employers in the tech industry who are having trouble recruiting and retaining employees, given the astronomical housing prices in Silicon Valley and elsewhere.68 Finally, some small-government conservatives have long championed efforts to reduce exclusionary zoning as a form of deregulation that enhances property rights and makes housing more affordable without additional government spending.

In forming coalitions, it is important to recognize, says Wiener, that the issue often breaks down less on the basis of party or ideology than on the basis of class. In the California legislature, there are some left-wing Democrats and right-wing Republicans who are supportive of efforts to reform exclusionary zoning, he says, and some of each who are opposed.69 The key dividing line was wealth.

Broad-based Tactics and Messaging

State and local experiences also suggest that focusing on being as broad-based as possible in tactics and messaging can make an important difference. Minneapolis officials did well with both. To avoid the dominance of NIMBY voices, city planners and advocates sought direct input from those hurt by exclusionary zoning. City staff went to street fairs, festivals, and churches to gather input on zoning reform from people in low-income and minority communities. They didn’t speak in jargon-laden terms about “increasing housing density,” but instead asked big questions such as “Are you satisfied with the housing options available to you right now?” and “What does your ideal Minneapolis look like in 2040?”70 Advocates recognized more broadly that language matters a lot in policy debates. The umbrella organization pushing for the Minneapolis 2040 reforms called itself “Neighbors for More Neighbors”—a name that brilliantly evoked the shared humanity of those who want to be included in exclusive neighborhoods.

In Oregon, the Sightline Institute concluded that positive framing was critical to success: telling people not what they’re giving up, but rather what they’re gaining. “Almost no one thinks ‘single family zoning’ is outrageous,” write Sightline’s Michael Andersen and Anna Fahey. “But when you tell people that duplexes are illegal to build in most of the United States and Canada, most people do actually find this outrageous.”71 Legalizing duplexes, triplexes, and apartments is more popular than ending single-family zoning. Likewise, Sightline’s messaging research suggests, when people say they worry about loss of “neighborhood character,” point out that people matter more than buildings. “It’s neighbors who give a community character. . . . When we allow only certain expensive building types, it determines who can or cannot afford to live in a community,” say Fahey and Anderson.72 In addition, be concrete about what’s being proposed—use pictures of duplexes and triplexes, so that people’s minds don’t erroneously go immediately to skyscrapers.

Even die-hard NIMBY constituencies—who may not be persuaded by moral arguments about racial segregation—may be receptive to arguments that explain how exclusionary zoning negatively affects them and their families. Wiener says that even older, upper-middle-class white homeowners were open to the argument that residents should work to avoid a situation in which their children “[were not] going to be able to afford to live in the community where they grew up”73 Wiener says framing the stakes in those personal family terms was often “extremely powerful with people.”74

Likewise, Virginia delegate Ibraheem Samirah, who is pushing legislation to reduce exclusionary zoning, finds that concrete arguments about how such zoning contributes to traffic congestion by pushing families further and further out can be more persuasive than abstract moral appeals. The bumper-to-bumper traffic, and stress, he says, is something that “everyday people can relate to.”75

Confronting Concerns about Gentrification and Displacement

A third important lesson for federal policymakers is that they need to address concerns that reforming exclusionary zoning could inadvertently accelerate gentrification and displacement. While eliminating single-family-exclusive zoning generally decreases housing prices by increasing overall supply and making less expensive construction possible, in rare cases, reform can also come with a downside. Zoning changes can pave the way for new construction, which often attracts wealthier residents who are willing to pay more precisely because the units are new.

State and local experience suggests policymakers must confront this problem head on in two ways. First, says Wiener, it’s critical to point out that the vast majority of gentrification does not occur in neighborhoods that had previously been zoned for single-family homes. Typically, neighborhoods with single-family-exclusive zoning are relatively wealthy areas; they already house the gentry.76 Second, in the “exceptional” cases where low-income, single-family communities are up-zoned and start to gentrify, inclusionary zoning requirements should be put into place to compel developers to set aside some new units for low-income and working-class people.77

Being Bold Can Make Room for More Modest Reforms

A final lesson from states is that, in the case of zoning reform, it can make sense to introduce bold, broad-sweeping reforms, because even if they are not immediately enacted, they can change the conversation and make room for important, more modest reforms. In politics, Wiener says, there is “a tendency to want to start small.”78 But with respect to zoning, California’s experience suggests the opposite can be true. When Wiener proposed sweeping legislation to require localities to open up transit corridors to apartment buildings, his dramatic proposal spurred alarm. “From the NIMBY perspective, it was like the death star was coming out” he says. Although the proposal has not yet passed, it started a conversation that “totally shifted the politics,” so that more modest reforms—like requiring single-family zoned areas to allow smaller accessory dwelling units, and allowing for lots to be split—became mainstream. The more aggressive proposal, he says, “created space for all of these other bills to move.”79 He concluded: “Even though that mega bill did not pass, it opened up enormous political space and shifted the goal posts in a positive way.”80

In sum, federal policymakers can learn a lot from state and local efforts about what types of reforms have the biggest impact and how the politics and messaging can bring about meaningful change. Perhaps the biggest takeaway is that making zoning laws more inclusive is no longer the taboo issue that it once was. Reform is not only necessary, it is possible, if pursued intelligently.

Eight Federal Proposals

The federal government has three broad sets of tools available to curtail exclusionary zoning. First, it can create new spending programs to provide voluntary incentives for localities to reduce exclusionary zoning. Second, it can place conditions on existing spending programs to encourage states and localities to make changes or risk forfeiting federal funds. Third, it can create a private right of action to empower parties harmed by exclusionary zoning to vindicate their rights in federal court.

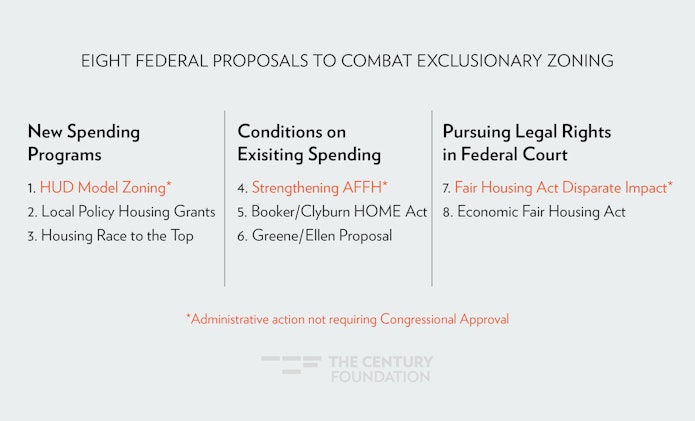

As Figure 3 below suggests, within each of these three buckets, the report outlines modest proposals that can be enacted without congressional approval as well as bolder interventions that require congressional action. The eight proposals discussed include: (1) a proposal that the Department of Housing and Urban Development promulgate model zoning ordinances that can be used voluntarily by localities to reduce exclusionary zoning; (2) the Biden administration’s proposed Local Policy Housing Grant program, which would provide $300 million in competitive grants to localities wishing to adopt positive zoning reform; (3) a multi-billion dollar “Race to the Top” competitive grants program to provide incentives to states to adopt more inclusive zoning policies; (4) a proposal to reinstate and strengthen the 2015 Affirmatively Furthering Fair Housing Rule to require localities to submit plans to reduce segregation; (5) the Housing, Opportunity, Mobility, and Equity HOME Act, sponsored by Senator Cory Booker and Representative James Clyburn (and endorsed by President Biden) to require recipients of certain infrastructure programs to outline plans to reduce exclusionary zoning; (6) a proposal by Solomon Greene and Ingrid Gould Ellen published by the Urban Institute to scale up the HOME Act to focus on larger pots of money and states rather than localities; (7) a proposal to more aggressively pursue “disparate impact” litigation under the Fair Housing Act to target exclusionary zoning that disproportionately harms racial minorities; and (8) an Economic Fair Housing Act, envisioned by The Century Foundation and developed by the Equitable Housing Institute, to provide a private right of action to individuals harmed by economically discriminatory exclusionary zoning. Arguably, the eight proposals run along a continuum, from 1 being the most modest and 8 being the boldest and most aggressive.81

Figure 3

In describing each of these proposals, the report delineates the idea, outlines the rationale and advantages offered, and details limitations. Throughout, the report considers how effective each proposal is likely to be in reducing exclusionary zoning; the political viability; and the risk that the proposal, if enacted, would be undercut by constitutional challenges in the courts.

New Spending Programs

One way to leverage change is to create new federal spending programs to encourage best practices among communities that are interested in reforming exclusionary zoning and need resources to do so. The programs could range from an administration decision to devote resources to creating model codes, to a modestly funded Land Policy Housing Grants to help assistant districts pursuing reform, to a bolder competition for federal funds to reform zoning, modeled after the Obama administration’s federal multi-billion dollar Race to the Top program.

HUD Model Zoning and Output Metrics

The Idea

Some housing policy experts have suggested that HUD promulgate model zoning and best practices for land use. As Noah Kazis of the NYU Furman Center notes, many other countries, including Japan and Germany, establish model zoning standards, as do states such as Oregon.82 Lists of best and worst practices could draw upon existing efforts: those in the Housing Development Toolkit published by the Obama administration and proposed bipartisan legislation known as the Yes in My Back Yard (YIMBY) Act.83 Some of the policies that might be disfavored could include those that ban accessory dwelling units, have large minimum lot size or square footage requirements, or require off-street parking.84

While the model codes would help inform zoning inputs, HUD could also task a team of researchers from different federal agencies to devise a set of outcome measures that would set targets for housing production goals by region, and each region’s appropriate fair share of low- and moderate-income housing—goals that are likely to vary based on whether a local economy is booming or in decline.85

Advantages

This proposal offers several advantages. To begin with, promulgating a model zoning code that is inclusive would begin to undo harm associated with pernicious model codes produced by the U.S. government a century ago. As the Economic Policy Institute’s Richard Rothstein has extensively documented, the federal government actively promoted racially segregated housing in the United States through numerous means, including the creation of a federal Advisory Committee on Zoning, organized in 1921 by President Warren G. Harding’s Commerce Secretary Herbert Hoover. The Advisory Committee promulgated a model zoning law and manual that recommended exclusionary zoning policies. “The manual did not give the creation of racially homogenous neighborhoods as the reason why zoning should become such an important priority for cities,” Rothstein writes, “but the advisory committee was composed of outspoken segregationists whose speeches and writings demonstrated that race was one basis of their zoning advocacy.”86

Promulgating a model zoning code that is inclusive would begin to undo harm associated with pernicious model codes produced by the U.S. government a century ago.

A new model code would provide localities that want to adopt more inclusive zoning programs with a gold standard to shoot for, which would have value in and of itself.87 Moreover, the model code would provide the building blocks for more aggressive proposals (outlined below) that seek to provide financial incentives for adopting good practices. Brandon Fuller of the Manhattan Institute suggests that a model code would “serve to give states and localities a sense of what [federal officials] are looking for insofar as they tie relevant block or competitive grants to easing the restrictiveness of local land use.”88 Because creating a model code would not require new congressional authorization, and because it does not require any locality to adopt the code, this initial step is the least controversial of the eight proposals for reform and the least likely to be challenged as unconstitutional.

Limitations

While creating a model code could have a positive effect on states and localities wishing to become more inclusive, the proposal’s impact would also be the most modest of the eight ideas outlined because it would not provide any financial incentives nor require change on the part of any locality or state.

Local Housing Policy Grants

The Idea

Joe Biden has endorsed a plan for the federal government to allocate $300 million in Local Housing Policy Grants as part of his campaign pledge to “eliminate local and state housing regulations that perpetuate discrimination.” The campaign suggested Biden’s investment in Local Housing Policy Grants would “give states and localities the technical assistance and planning support they need to eliminate exclusionary zoning policies and other local regulations that contribute to sprawl.”89 The plan builds upon HUD’s earlier Sustainable Communities Initiative.90 Until the Initiative was eliminated by Republicans in 2011, it provided two types of grants: (1) Sustainable Communities Regional Planning Grants that “support metropolitan and multijurisdictional planning efforts that integrate housing, land use, economic and workforce development, transportation, and infrastructure investments”; and (2) Community Challenge Planning Grants that “foster reform and reduce barriers to achieve affordable, economically vital, and sustainable communities,” and includes a specific commitment to reforming “zoning codes.”91

Very recently, a bipartisan group of senators, including Amy Klobuchar (D-MN) and Tim Kaine (D-VA) and Senator Rob Portman (R-OH) introduced legislation along similar lines to authorize $1.5 billion in competitive grants to encourage localities to increase housing supply. The Housing Supply and Affordability Act would provide planning and implementation grants to localities that want to ease exclusionary zoning and make way for greater housing production.92

Advantages

This proposal offers several advantages. First, it capitalizes on what experts say is an uptick in interest from local planners to make zoning more inclusive. Rolf Pendall of the University of Illinois says that, following the publication of Richard Rothstein’s The Color of Law, which documented the racist history of planning, and the police killing of George Floyd, there has been evidence of “a growing commitment among planners” to reduce exclusionary zoning. Although planners themselves do not have the power to make changes without the consent of elected officials, “they can be important in shaping the narrative, introducing history to the conversation [and] thinking about how to move toward greater inclusion,” he says.93

Local housing policy grants could help spark innovation among planners of good will that could serve to highlight best practices. The idea appears politically attractive because it involves a relatively small amount of federal money, and does not compel unwilling localities to participate. Nor does the proposal present a target for constitutional challenge.

Limitations

The modesty of the proposal can also be seen as a drawback: the planning grants will only provide resources to the already converted, and does nothing directly to compel, or even incentivize, bad actors to change their behavior.

Race to the Top

The Idea

Community Change and the Ford Foundation’s Housing Playbook for the New Administration has proposed a “Race to the Top for affordable housing,” modeled after the Obama administration’s $4 billion Race to the Top education initiative. In order to qualify for funding, a state would have to “demonstrate it has taken state-level actions within the last four years to remove exclusionary zoning or other regulatory barriers that prevent multi-family or manufactured housing.” Once states pass the threshold of qualifying for funding, they would complete for federal grants by meeting particular criteria: “states would have to set housing production goals for the state, enact ‘fair-share’ distribution requirements to ensure all housing is distributed across communities, and adopt broad zoning reforms such as bans on single-family-exclusive zoning, enabling modest multifamily housing to be built in all residential areas, or zoning-override initiatives like the Massachusetts 40B system.”94 Under Massachussetts’s Chapter 40B housing statute, builders may override local zoning laws that prevent the construction of affordable housing in communities where less than 10 percent housing is affordable.

As part of the American Jobs Plan, the Biden Administration has proposed a $5 billion version of a Race to the Top idea. In order to encourage localities to “eliminate exclusionary zoning and harmful land use policies” Biden’s Jobs Plan calls for Congress “to enact an innovative, new competitive grant program that awards flexible and attractive funding to jurisdictions that take concrete steps to eliminate such needless barriers to producing affordable housing.”95

The Advantages

The Race to the Top for affordable housing seeks to build on the demonstrated ability of the educational Race to the Top program to change state behavior on issues such as lifting caps on charter schools or use of the Common Core Curriculum. If funded with sufficient resources, the Race to the Top model is likely to have a bigger impact on states than a small grant program or promulgating model codes. At the same time, proponents suggest it avoids some of the downsides of programs (outlined below) that condition funds on reducing exclusionary zoning. Because Race to the Top is voluntary, it would likely generate less political opposition than a program that withholds existing streams of money. And it allows states to develop metrics of success that do not currently exist at the federal level.96 Because the program involves new competitive grants, it is unlikely to be struck down on the grounds that the federal government’s policy is unduly coercive.

Limitations

Having said that, a Race to the Top program would require the outlay of very large amounts of money in order to move state legislatures, which are often dominated by exclusive suburban legislators, to confront the issue of exclusionary zoning.97 And states where opposition to reform is strong would simply be free to not apply for the program.

Attaching Conditions to Existing Spending

A second bucket of reforms would go beyond providing new funding carrots for states and localities and instead place conditions on existing funding streams. The federal government currently doles out billions of dollars for infrastructure programs, such as Surface Transportation and Community Development Block Grants (CDBG), and this set of reforms would place relevant conditions on this spending. Within this bucket, the report discusses three leading ideas: restoring the 2015 Obama-era Affirmatively Furthering Fair Housing rule to promote desegregation as part of the Fair Housing Act; a proposal from Senator Cory Booker and Representative James Clyburn to condition a broader set of funding on reducing exclusionary zoning; and a proposal from Solomon Greene and Ingrid Gould Ellen published by the Urban Institute to condition an even broader set of funding on state efforts to reduce exclusionary practices.

Restore the 2015 Affirmatively Furthering Fair Housing Rule

The Idea

In 2015, the Obama Administration adopted the Affirmatively Furthering Fair Housing (AFFH) rule for implementing the 1968 Fair Housing Act’s requirement that local government’s “affirmatively further fair housing” by taking steps to dismantle racial segregation. The 2015 rule required all municipalities receiving funding from HUD to complete a comprehensive assessment of fair housing and to commit to taking specific steps to “overcome historic patterns of segregation.”98 The assessment would examine, among other things, the effect of exclusionary zoning laws.99

In 2018, the Trump administration postponed implementation of the rule;100 and in 2020, Trump repealed the rule altogether as part of his campaign to win “suburban housewives of America.” As noted above, President Biden has already directed HUD to explore reinstating the rule. Others have suggested going further, and Megan Haberle, Peter Kye, and Brian Knudsen of the Poverty and Race Research Action Council have suggested ways to sharpen AFFH’s assessment tools and increase accountability.101

Advantages

Although not perfect, the 2015 AFFH rule ignited important conversations in a number of localities about a long-ignored issue within the Fair Housing Act—the duty not only to stop discriminating, but also to take steps to dismantle segregation. The repeal by the Trump administration, accompanied by bigoted rhetoric about protecting suburban areas from crime and property devaluation, was an outrage. Restoring the rule has several advantages. First, it does not require new legislation from Congress; nor does it require the allocation of new federal funds. Furthermore, application of AFFH has fairly broad reach because it applies to existing streams of federal funds that communities have come to rely upon, not a new set of funds they might choose not to pursue. As a political matter, President Trump’s attempt to attack the AFFH rule appeared unsuccessful, and mainstream business groups, including the Business Roundtable, support its reinstatement.102 Constitutional attack on AFFH is also unlikely to succeed.

Limitations

While restoring the AFFH rule makes enormous sense, there are four reasons to think that doing so is by itself insufficient. First, AFFH, like all programs that condition existing funds on taking certain actions, face the fundamental dilemma that federal officials whose job it is to funnel funds to important programs are loath to exercise threats to withhold funds.103 Demetria McCain of Dallas’s Inclusive Communities Project objects that in the Dallas area, “HUD continues to greenlight” projects in jurisdictions that discriminate.104 Second, many of the wealthiest suburbs that engage in the worst forms of exclusionary zoning don’t receive much CDBG funding, so AFFH’s threat to cut off funds holds little leverage, as Jenny Schuetz of the Brookings Institution has shown.105 In 2016, for example, Douglas County, a suburb of Denver, Colorado decided to give up CDBG funds rather than comply with the AFFH requirements.106 Third, the AFFH is focused on processes of identifying goals and steps to take but avoids specific mandates for achieving particular outcomes.107 And fourth, the AFFH lacks a private right of action, so its enforcement depends on the actions of whichever federal administration is in place.108

Booker/Clyburn HOME Act

The Idea

Senator Cory Booker and Representative James Clyburn’s ’s Housing, Opportunity, Mobility, and Equity (HOME) Act offers two ways to make housing more affordable and equitable. It provides a monthly tax credit for rent-burdened individuals to address the affordability problem immediately, and it also seeks to increase the supply of housing by providing incentives for localities to make zoning less exclusionary.109

The bill’s second prong would condition two types of federal funding—Surface Transportation Block Grants and Community Development Block Grants—on community efforts to reduce exclusionary practices.110 The legislation provides a menu of options that communities could take to reduce exclusionary zoning. They could authorize more high density and multifamily zoning, relax lot size restrictions, or reduce parking requirements and restrictions on accessory dwelling units—small living units adjacent to larger homes. Jurisdictions would also have incentives to allow “by-right development,” so that projects that meet zoning requirements could be administratively approved rather than being subjected to lengthy hearings. Inclusionary zoning policies that allow developers to build more units when they agree to set aside some for affordable housing would also be encouraged. Jurisdictions would also have an incentive to adopt prohibitions on “source of income discrimination,” which occurs when landlords refuse to rent to people using publicly funded housing vouchers. One provision in the bill—perhaps its most controversial one—encourages jurisdictions to ban the practice of landlords asking potential renters about their criminal history.111

The bill includes both input and output measures, but it is designed not to be overly prescriptive.112 “It is a light touch,” Booker says. “We’re just basically saying, through our legislation, that you have to have a plan” for making zoning more inclusive. “And the components of the plan are on you.”113

President Biden has endorsed the legislation, making it a leading vehicle for zoning reform. Biden’s campaign explained:

Exclusionary zoning has for decades been strategically used to keep people of color and low-income families out of certain communities. As President, Biden will enact legislation requiring any state receiving federal dollars through the Community Development Block Grants or Surface Transportation Block Grants to develop a strategy for inclusionary zoning, as proposed in the HOME Act of 2019 by Majority Whip Clyburn and Senator Cory Booker.114

The Advantages

Booker and Clyburn’s bill builds upon Obama’s AFFH rule but offers four potential advantages. To begin with, whereas the AFFH rule is designed to reduce discrimination against groups protected in the Fair Housing Act (primarily people of color), Booker and Clyburn take on economic discrimination as well, by reducing exclusionary zoning that impacts low-income families of all races. Booker told me that while his own upper-middle class Black family was aided by the Fair Housing Act’s prohibition on racial discrimination and gained access to an affluent community with strong public schools, many of his cousins, with lesser means, were still left behind because of exclusionary zoning.115

Second, the HOME Act goes beyond the AFFH rule’s conditioning of CDBG funds to include Surface Transportation Funds. This is significant, one critic of the Booker legislation suggested, because while suburbs could get around the rule’s requirements by foregoing CDBG funds, Booker’s inclusion of federal transportation grants would have a much bigger impact. “It may be next to impossible for suburbs to opt out of those state-run highway repairs,” critic Stanley Kurtz wrote in the National Review.116

Third, because the HOME Act’s attack on exclusionary zoning is focused primarily on the issue of housing affordability (by increasing housing supply, Booker suggests the bill will contain housing costs), the bill also includes a monthly tax credit for rent-burdened individuals not benefited by the AFFH rule. While increasing housing supply should reduce housing costs over the long term, Booker argues, the tax credits are needed to provide immediate relief.117 And, if and when the effects of zoning reform kick in, any resulting drop in housing costs will make the purchasing power of tax credits even more substantial.118

Fourth, whereas the AFFH rule can be repealed by executive action (as President Donald Trump did in 2020), Booker and Clyburn seek to enact a new law that could not simply be rescinded by a future administration unfriendly to the goals of the initiative. In addition, the bill’s condition of funding is closely related to the underlying legislation and is unlikely to fall to constitutional challenge.

Limitations

While the Booker bill offers several advantages, it also has a few notable limitations (which a proposal outlined below seeks to remedy in certain ways) The amount of funding at stake—through CDBG and Surface Transportation Block Grants—may not be broad enough to achieve maximum leverage. The focus on thousands of localities makes it difficult to monitor. The bill’s emphasis on districts taking particular actions (reducing certain zoning requirements) may not put sufficient emphasis on outcomes. As a result, one barrier knocked down might be replaced by a new one installed—with no net improvement in results.119 Finally, while the bill gives flexibility to localities—making it “a fairly light touch intervention”120—the moderate nature of the approach did not stop the issue from being weaponized by Donald Trump as an attempt to “abolish the suburbs.”121

The Greene/Ellen Proposal Published by the Urban Institute

The Idea

In September 2020, Solomon Greene of the Urban Institute and Ingrid Gould Ellen of New York University’s Furman Center proposed that the federal government “require that to receive competitive funding for housing, transportation, and infrastructure, states must demonstrate measurable progress toward meeting regional housing needs and distributing affordable housing across a diverse range of communities.”122

The proposal builds on the Booker/Clyburn HOME Act’s fundamental framework that federal funding ought to be conditioned on reductions in exclusionary zoning but makes a number of design changes that respond to criticisms of the HOME Act.

For one thing, whereas the HOME Act conditioned funding mostly to localities or regional agencies, Greene and Ellen’s proposal would move the focus “up” and “out”; that is, it would move the focus up to the state level,123 and out to a broader set of funding streams for transportation and infrastructure than the HOME Act.124 And the proposal places conditions on “competitive” rather than formula grants, so states can choose whether to participate.125

In another distinctive feature, Greene and Ellen put their focus primarily on performance goals rather than processes. They set two distinct goals: housing production, and fair share distribution of affordable housing. Greene and Ellen provide an example that “states could create a goal that at least 20 percent of all new construction in any region should be affordable to households with 80 percent of the region’s median income and that at least half of these affordable units should be built in neighborhoods where median income is above the region’s median income.”126

While focusing more on outcomes than process, the authors do outline two sets of practices that automatically qualify a state for competitive grants: (1) the elimination of single-family-exclusive zoning policies such as those found in Oregon’s HB 2001 would presumptively qualify states for the housing production outcome goal; and (2) a state law that “allows developers to bypass local zoning laws in communities that lack affordable housing options, when a project includes units with long-term affordability restrictions” similar to Massachusetts’s Chapter 40B law, would make a state presumptively qualify for the “fair share” outcome goal.127

Advantages

Greene and Ellen’s approach of focusing “up” at the state level—which was popular among TCF/Bridges Collaborative roundtable participants—offers several benefits. To begin with, the focus of state funding provides the federal government with greater leverage because federal grants constitute 31 percent of state revenues, as compared with just 5 percent of municipal revenues.128 They argue that it is also easier for the federal government to monitor fifty states than thousands of localities.129 Philip Tegeler of the Poverty and Race Research Action Council suggests the focus on states is appropriate for a couple of reasons. “States are fully in the driver’s seat when it comes to zoning and land use,” Tegeler notes, as it is the state’s decision whether or not to delegate zoning powers to localities.130 States are a key actor in driving segregation.131 Tegeler argues, “Exclusionary zoning is a problem of state law, implemented at the local level and protected by state legislatures that are largely dominated by suburban legislators.”132

Exclusionary zoning is a problem of state law, implemented at the local level and protected by state legislatures that are largely dominated by suburban legislators.

Greene and Ellen’s focus “out” to a broader set of funds—$67 billion in transportation money, compared with just $7 billion for housing and community development—is also attractive as it increases the leverage of the federal government.133

Roundtable participants also appreciated Greene and Ellens focus on outcomes over process, both because it provides flexibility to localities with respect to how to achieve the goals, and because exclusionary zoning is so slippery that, if a law focuses on process, a community can remove one objectionable roadblock to the development of affordable housing and then—quite easily—erect a new, less obvious barrier.134 As Jenny Schuetz of Brookings notes, if you give localities a list of prohibited activities such as single-family-exclusive zoning “they will get around that in some way,” by creating new barriers.135 She notes that “local governments have a nearly infinite range of land use tools that can effectively block unwanted development.”136 Even seemingly progressive policies—such as inclusionary zoning (IZ)—can be perverted to stop development. “Mandatory IZ with an 80 percent low-income set aside is an effective way to kill new housing while claiming to be pro-affordability,” she notes, because no developer would find it profitable to be able to rent only 20 percent of units at market rate.137 At the same time, the inclusion of two presumptive practices—eliminating single-family-exclusive zoning and providing Massachusetts-style fair share requirements—gives states a roadmap for the types of reforms that are likely to produce positive results.

Roundtable participants also applauded Greene and Ellen’s focus on two sets of performance goals—not just production but fair share distribution. The distribution prong ensures that a state could not meet its affordable housing production goals by placing all of the new units in high-poverty communities.138

Finally, Greene and Ellen’s focus on competitive rather than categorical grants offers a few advantages. Because no state is forced to change behavior, political opposition might be reduced, as are the chances of a constitutional challenge based on federal “coercion.”139 The focus on competitive grants also helps mitigate the problem inherent in the AFFH rule that, as NYU’s Noah Kazis notes, “federal agencies are loath to actually withhold funds from jurisdictions.”140

Limitations

While the Greene/Ellen proposal has many strengths, some roundtable participants noted some limitations. While the focus on outcomes rather than processes is conceptually strong, Kazis argues, as a practical matter, the federal government does not yet have good metrics to measure underproduction and exclusion.141 Given differences in communities (some booming, others struggling) states will have to come up with their own customized metrics that HUD will have to approve.142 Given that variation, it is wise that Greene and Ellen also include references to two processes—ending single-family-exclusive zoning and Massachusetts’s fair share rule—that provide a common standard across states.143 Likewise, while the conditioning of a broader set of funds increases the leverage of the federal government, it also makes passage of Greene and Ellen’s proposal a heavier political lift, and may increase the chances that courts see the spending conditions as coercive.144

The biggest limitation on the Greene/Ellen proposal, however, may be its reliance on state political actors, rather than courts, to vindicate the rights of excluded parties. As Jenny Schuetz of Brookings asks: “Would legislatures dominated by suburban and/or rural representatives prefer to decline federal money, especially opting out of new funds, rather than concede on exclusionary zoning?”145 Likewise, Tom Loftus of the Equitable Housing Institute suggests that state political approaches to exclusionary zoning—including Massachusetts’ approach—while positive have ultimately failed the test of producing sufficient housing, as housing costs even in states with relatively good laws on exclusionary zoning, have continued to rise.146 This limitation is a reason to supplement—not supplant—the Greene/Ellen proposal with ideas to strengthen a private right of action, an issue to which we now turn.

Pursuing Legal Rights in Federal Court

Litigation “sticks” provide a federal right of action to those who have been harmed by exclusionary zoning to sue in federal court and receive damages and attorneys’ fees. The Fair Housing Act provides such a right in cases of racial discrimination. Advocates for this approach argue that, because supporters of exclusionary zoning hold disproportionate political power, especially at the local and state levels, the courts are an important venue for those with less power to pursue their rights.

Disparate Impact Litigation

The Idea

Civil rights advocates have suggested that the Biden administration should do more to reduce exclusionary zoning through so-called “disparate impact” litigation that goes after local practices that have the effect—even if not the intent—of discriminating against minorities.

Under the 1968 Fair Housing Act, private plaintiffs and the U.S. government can bring disparate impact lawsuits against municipalities that engage in policies such as exclusionary zoning. Under disparate impact jurisprudence, plaintiffs have the burden of showing that the challenged practice causes a disproportionately negative impact on a protected class (such as people of color). Once that showing is made, the burden shifts to the defendant to demonstrate that the practice is necessary to achieve a legitimate nondiscriminatory goal.

In the 2015 U.S. Supreme Court decision in Texas Department of Housing and Community Affairs v. The Inclusive Communities Project, the Supreme Court ruled, 5–4, that disparate impact litigation is legitimate under the Fair Housing Act, and noted that “zoning laws and other housing restrictions that function unfairly to exclude minorities from certain neighborhoods without any sufficient justification . . . reside at the heartland of” disparate impact jurisprudence.147

In Inclusive Communities Project, the Supreme Court specifically cited two cases as important precedents involving exclusionary zoning. The first was United States v. City of Black Jack (1974), in which the Eighth Circuit struck down Black Jack, Missouri’s ban on multifamily housing, which would have foreclosed 85 percent of Black people in the St. Louis, Missouri metropolitan area from living in Black Jack.148 Likewise, in the 1980s, the NAACP challenged Huntington, New York’s single-family-exclusive zoning ordinance that channeled multifamily housing away from a section of town that was 98 percent white to an “urban renewal” zone populated by minorities.149

The Supreme Court in Inclusive Communities Project noted that not all government decisions that result in a disparate impact are illegal. “Valid government policies” can stand, but those that pose “artificial, arbitrary and unnecessary barriers,” must fall.150 When plaintiffs win disparate impact cases, they can seek injunctive relief, damages, and court-awarded attorneys’ fees.151

Civil rights advocates and some journalists suggest the Biden administration take three concrete steps. First, Biden could restore 2013 HUD guidance provided around disparate impact litigation (guidance that Donald Trump repealed).152 Biden has already instructed HUD to look into doing this.153 Second, Biden could increase resources to beef up disparate impact enforcement. As Jerusalem Demsas argues in Vox, “More than 50 years after passage of the Fair Housing Act, it’s time to sue the suburbs.”154 HUD’s Office of Fair Housing and Equal Opportunity should be funded at much higher levels, she suggests, to bring disparate impact cases in communities that engage in exclusionary zoning. Demsas quotes Sara Pratt, a deputy assistant secretary for fair housing enforcement in the Obama administration, as saying: “I think a well-staffed civil rights office can have a major influence over a period of time in changing the country’s patterns of segregation. I actually have no doubt of it.”155 Third, Biden could allocate federal resources to private fair housing organizations to investigate and enforce exclusionary zoning claims under the Fair Housing Initiatives Program, as Philip Tegeler of PRRAC argues.156

Advantages

Enhancing Fair Housing disparate impact enforcement offers two major advantages. First, because states and localities make housing policy decisions that are disproportionately influenced by wealthy NIMBY forces, removing the issue from politics to the courts helps people of color vindicate their rights. Second, because the U.S. Supreme Court has recently affirmed the right to bring disparate impact litigation, the strategy requires no new acts of Congress.

Limitations

While a powerful tool, disparate impact litigation has four limitations. First, conceptually, disparate impact is about racial discrimination, not class discrimination. These two categories often overlap—income discrimination in zoning very often results in a negative impact on people of color—but because race and class discrimination are distinct harms, the two do not coincide in all cases. Second, as a practical matter, because plaintiffs in disparate impact cases have the extra evidentiary burden of showing that class discrimination disproportionately harms people of color, plaintiffs have to hire expensive experts to make this showing. Third, over the years disparate impact has had a disappointing track record in the courts, with very few cases winning on appeal.157 Finally, the 2015 Inclusive Communities Project decision upholding disparate impact under the Fair Housing Act may be vulnerable in today’s more conservative Supreme Court. In the 5–4 decision, the now-retired Justice Anthony Kennedy cast the deciding vote, a potential vulnerability in the future.158 (Each of these issues is discussed in further detail below.)

Equitable Housing Institute Economic Fair Housing Act

The Idea

In August 2017, a Century Foundation report proposed the idea of an Economic Fair Housing Act that would make it illegal for government zoning to discriminate based on income, just as the 1968 Fair Housing Act makes it illegal for parties to discriminate based on race.159 The law would supplement—rather than supplant—the Fair Housing Act’s focus on race.