While college costs have risen significantly in the past few decades, some of those cost increases can be partially mitigated by financial aid for low-income families. But many low- and moderate-income families vastly overestimate the cost of college, leading them to assume that enrolling their children in college, particularly a four-year school, is not a realistic option, or that aid is not available even if they do decide to enroll. Even when families are aware that financial aid is available, they frequently assume that they will not be eligible for it.

These families typically have inadequate information to assess the cost of college and their aid options. The type of information typically distributed by states is not effective: general information about average tuition levels or descriptions of state-operated financial aid programs lack clear relevance to the specific family or student. Reaching these families with more accurate information about the actual, potentially lower college costs they can expect to encounter can go far to help keep their students on the road to college, and open to a wider variety of school options.

More must be done to lower the cost of college. But as the federal government and state governments pursue those efforts, this report explores how states could simultaneously do more to generate and send to families personalized estimates of college costs—after aid—for their students.1 First, it reviews the college costs and financial aid information gap that families encounter. Second, it reviews how states have leveraged existing data in other social policy areas to provide information and even make eligibility determinations. Third, it analyzes key considerations in designing an outreach initiative that leverages state tax information. Finally, it looks across three states—California, Michigan, and Texas—to determine how such an initiative would work in practice, basing assessments on research from existing state agency information data sharing practices and interviews with financial aid, higher education, and taxation state workers in each of the selected states.

The Problem

Disparities in who enrolls in college, and where they enroll, results in a higher education landscape that remains highly stratified by socioeconomic status (SES). About 41 percent of low-SES and 27 percent of middle-SES high school graduates did not enroll in any form of postsecondary education, whereas only 8 percent of high-SES recent graduates did not.2 This stratification persists when examining where students attend college when they do enroll. Of the low- and middle-SES student attending college, only 12 percent and 28 percent, respectively, attended a four-year institution, while 60 percent of high-SES high school graduates attended one.

Those disparities are driven by a wide range of factors, including real and perceived affordability challenges. The cost of college has increased significantly over the past several decades. But, in some cases, aid may be available to bring down those costs. In California, for example, enough aid is available at public four-year institutions to make the net price lower for low-income students to attend a University of California school than a community college.3 But almost half of students who do not fill out a Free Application for Federal Student Aid (FAFSA) state that they believe they will not qualify for financial aid or are not eligible to complete a FAFSA.4 As a result, students leave potentially billions of dollars of aid on the table: one study projected that Pell-eligible high school graduates left $2.3 billion in federal aid unutilized due to not completing the FAFSA.5

Many low- and moderate-income college students and their families overestimate the actual cost of college. For example, only half of eleventh and twelfth graders who stated they planned to attend college had, at that point of the study, actually obtained information about tuition and fees. This group also greatly overestimated the cost at four-year institutions: students overestimated by 65 percent, and their parents by 80 percent.6 When they were asked to estimate the cost at two-year colleges, students overestimate by 240 percent, and their parents by 153 percent. Compounding this information gap, many prospective students and their families do not know they may qualify for financial aid, as they have limited knowledge about eligibility requirements and what financial aid covers.7 This lack of accurate information is critically important, because money is a major reason academically eligible students do not attend college.8

Vague, inaccurate, or missing information about grant aid is particularly problematic. Grant aid not only helps limit debt for students who enroll in college, but also increases the number of people who enroll in the first place.9 The best evidence available suggests that offering a prospective student an additional $1,000 of financial aid—specifically, grants—may increase that student’s likelihood of college enrollment by four percentage points.10 But, if a potential student does not know that they would receive aid, nor how it relates to the tuition price and other costs, they may not respond to the price subsidy and enroll in college. In fact, a student typically does not obtain concrete information about financial aid until after they have applied for and been accepted to a postsecondary institution, which is too late. These issues are most acute for low-income students.11

Informing students about aid is necessary, but research shows that providing only general information is not enough.12 To help more low-income students enroll in college, states need to give these families personalized financial aid information much sooner—ideally starting as early as seventh grade, and certainly no later than ninth grade. Studies show that providing financial aid information to eighth graders, for example, increased their enrollment in college preparatory classes,13 and it made high school students more likely to aspire to obtain a college degree.14 Given most college admission requirements include students passing at least Algebra 2 or the equivalent—which typically requires at least three years of math in high school—providing students with financial aid information sooner will give them the time to make the decision to complete all the required math courses, as well as other college-prep courses. Addressing misconceptions about college costs and aid early will also give families time to save money for college, if saving is financially feasible, and students time to meet application deadlines for college and financial aid. And importantly, this knowledge will encourage students to complete a FAFSA when the time comes, making them far more likely to actually enroll in college.15

By leveraging other interactions with residents, such as state income tax forms or agencies delivering other public benefits, states can reach far more families than are reached through traditional in-person outreach, such as financial aid nights at high schools. In many cases, the parents who attend available financial aid information sessions are those that already have financial aid information.16 The parents who would truly benefit from the information covered in these sessions sometimes cannot attend, due to work and other issues.17

States have an opportunity to reach their residents at scale with personalized information that may alter their decisionmaking around college application and enrollment.

Existing Federal and State Models

In order to provide students and their parents with personalized information about college attendance costs and financial aid, any new initiative by a government agency would have to access family data that may exist in varying forms, as well as information about college costs and pricing, all potentially held by other agencies. The good news is that there is a long record of government agencies doing just that: using existing data for similar program eligibility and renewal determinations, and agencies that leverage existing data to engage in large-scale, prospective outreach about program eligibility. This section reviews various programs across the country to highlight successes and lessons learned in implementing similar strategies across social policy.

Social Security Retirement Estimates

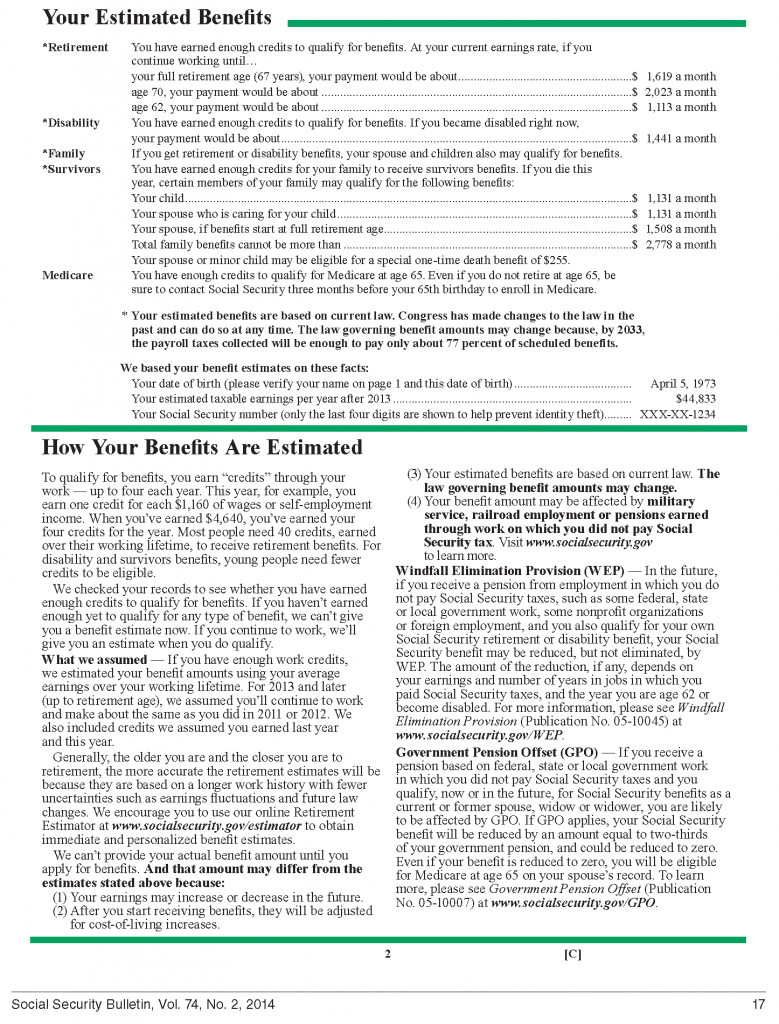

The Social Security Administration’s (SSA) information efforts are perhaps the most fitting example of what a state could do with regard to college costs and financial aid. Starting at age 25, and every five years thereafter, every American with a Social Security number receives an estimate of the benefits they can expect to receive in retirement, based on their own wage history and the resulting contributions. The amounts are estimates, but they have greater salience to the recipient because they are individualized. The letters can help people plan for retirement and increase knowledge of SSA benefits.18 (See Figure 1. ) The SSA also offers personalized estimates to anyone at any time through a website, https://www.ssa.gov/myaccount/.To create these estimates SSA receives data from employers and the IRS, which includes IRS Form W-2, quarterly earnings records, and annual income tax forms to estimate a person’s retirement benefits.19

Figure 1. Sample Social Security Retirement Benefit Estimate Letter

No Wrong Door Programs

Many state government agencies already share data to better serve state residents through a “No Wrong Door” (NWD) program—sometimes referred to as a “Single Entry Point” program—that allows a person to contact any social service agency in order to be connected to and enrolled in the programs they need, such as Medicaid, Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF), and Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP). An NWD program gives multiple government agencies access to a person’s income and eligibility information, after that person submits a consent form when they first apply at any social service agency.

NWD programs have had remarkable success. Washington State, for example, launched a statewide NWD demonstration project under the Department of Social and Health Services (DSHS) in 2002 that focused on different populations that tended to receive at least three DSHS services: persons with multiple disabilities, troubled children, youth and families, and long-term TANF families. To participate, the person seeking services needed to sign a consent form, and the agency developed a case coordination system to integrate programs. All data was compiled into one database that all workers in the demonstration project could access.20 The program has allowed the state to better coordinate its service provision, achieving results such as decreasing the homeless veteran population in a program launched after the demonstration project.21

Free and Reduced-Price Lunch Determination

The federal free and reduced-price lunch (FRPL) program, which provides low-income school aged children with meals during the school day that are either free or discounted, depending on their income, is a great example of cross-agency data sharing. While families can fill out an application, schools can also determine a student’s eligibility without an application through direct certification and categorical eligibility.22 Direct certification requires schools to automatically enroll students into the program if they are participating in SNAP, but some schools also do this if a student participates in the Food Distribution Program on Indian Reservations, TANF, or Medicaid. Schools are able to do direct certification through a federal mandate23 that requires a data exchange between schools’ Local Education Agencies (LEA) with SNAP but allows for a data exchange with other state public programs. School enrollment records are matched with SNAP enrollment records, or other public programs, either at the state level or school district level.

In California, the California Department of Education (CDE) created a statewide direct certification system. State and local agencies that administer assistance programs, such as CalFresh, CalWORKs, and Medi-Cal, send their enrollment data to CDE. CDE’s system then matches student information from the California Longitudinal Pupil Achievement Data System (CALPADS) to the enrollment data. This is done by working with the California Department of Social Services and the California Department of Health Care Services.24

SNAP Income Data for CHIP Determination

Various states have used SNAP participants’ application data to enroll children into the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP), which generally has a higher income threshold than SNAP. There are two ways this can be achieved—through a data match, or data sharing. For example, Louisiana’s Department of Children and Family Services (DCFS) uses data sharing, sending SNAP participation data to Department of Health (DOH) to enroll children into CHIP. DOH then renews those children’s CHIP eligibility through a data match with SNAP income data to gain a high level of certainty of continued eligibility.25 As a result, in 2010, Louisiana enrolled more than 10,000 children into CHIP.26

IRS Data Retrieval Tool for FAFSA

The partnership between the IRS and the federal financial aid form, the Free Application for Federal Student Aid (FAFSA), leverages federal income data to simplify aid access.27 In order to alleviate some of the burden of an arduous process, this partnership allows financial aid applicants to import their IRS data into their application instead of manually entering it. When a prospective student fills their FAFSA online, they receive a message asking if they want to import their IRS data. If the applicant selects yes, then they are taken to the IRS website to verify their identity. Once that occurs, only the relevant tax information for the FAFSA will be pre-populated on their application. Lastly, instead of their tax information being displayed on their FAFSA, “Transferred from the IRS” will be displayed.28 The IRS Data Retrieval Tool does not require the IRS to obtain consent to share the information with the U.S. Department of Education since the taxpayer herself is always initiating the data transfer.

Key Takeaways

Cross-agency data utilization in other public programs has been authorized through legislation or personal consent, and allows these programs to more seamlessly provide residents with information about eligibility, and at times even automatically enroll program beneficiaries. Doing so has closed the information gap for potential beneficiaries and simplified application processes. Even when an actual determination cannot be made, providing estimates is still useful in helping make more real people’s options so they can better plan for the future.

Promoting Early Financial Aid Awareness

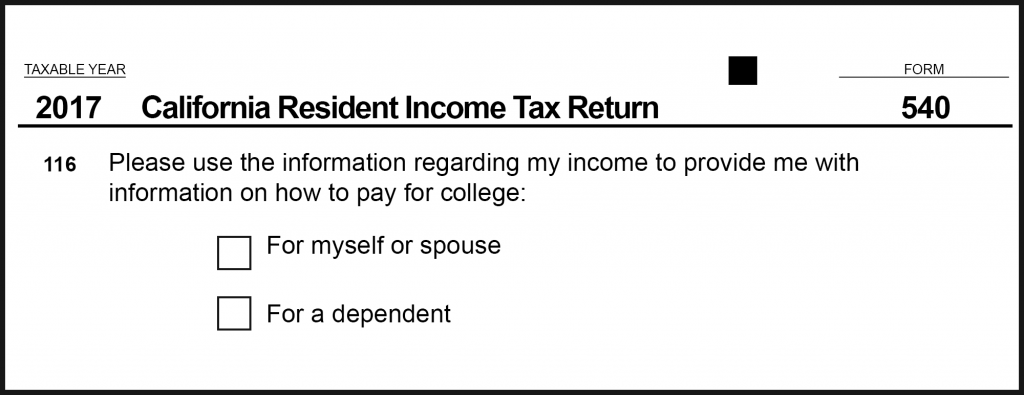

States seeking to better inform their residents about the true cost of attending college can leverage existing data to provide personalized college cost estimates in various ways. As with the SSA’s efforts on Social Security retirement income, a state agency could proactively send information to families that provides individualized cost and aid estimates, based on information from state income tax forms or other sources. If taxpayer consent is an issue, then the state income tax forms could include a checkbox where people can elect to have their information shared to receive information about college costs and aid (see Figure 2).

Figure 2: A Mock California Income Tax Form 540 Showing a Request for Information about Paying for College

The tax agency could work with the appropriate state higher education agency to either develop information that would be provided through the tax agency (resulting in no sharing of taxpayer data between the agencies), or provide the family income information to the other agency that then produces the estimates. As state policymakers consider implementing this strategy, they will have to contemplate four core components:

- the target population of such outreach;

- what information to provide families, given states will not have all of the data necessary to present precise projections;

- how to send that information to families; and

- how to ensure a seamless data sharing system that protects the privacy of taxpayers.

Target Population and Targeting Information

Adding a checkbox for requesting projections of college costs to the state tax form would provide a defined data sample to only those interested in learning more, and would provide enough data to generate usable projections on potential aid eligibility and the net price of college attendance. Tax forms have adjusted gross income, a proxy for family size through the number of dependents the taxpayer claims, and a person’s mailing address, and in some cases, their email address in order to send the financial aid communication. Depending on the data available, it may be important for the checkbox to request the dependents’ ages for whom the tax filer is requesting college cost information, as some financial aid programs have age requirements.

There are limitations to the reach of a strategy that only relies on tax forms: some may resist checking the box because they are worried about sharing their data, and some of the poorest families will not be captured if their income is low enough that they do not need to file taxes and also do not file for EITC.29 Data sharing with other agencies providing public benefits, such as SNAP, or with education departments for free and reduced priced lunch data, may fill those gaps.

Information on Aid and Costs

Providing students and their families with examples of estimated costs at specific colleges can make the information more real. To do so, states can generate a personalized net price estimate by linking institutions’ net price calculators to the state higher education or financial aid agency. To streamline this process, colleges in the state should be required to make their net price calculator code available to the state agency. The information generated by those calculators would include the net price a student would have to pay for both tuition and non-tuition costs, as well as details on the total cost of attendance, total grant aid available, the amount of money the student would be expected to contribute to the total cost (the “expected family contribution”). This information should be presented for colleges near the student, especially when there are great tuition differentials—for example, a community college versus a public four-year versus a private four-year. Along with the net price projections, families may also want secondary information on the grant eligibility requirements so they can gain a better sense of whether they are actually eligible for the aid, as well as the maximum award amount, so they know how much aid might be available. States should engage in outreach and consumer testing to better understand which additional information to provide and how to provide it.

There are limitations to the financial aid predictions: incomes change over time, and some aid programs have eligibility requirements and award amount calculations that go beyond the data available on state tax forms, such as asset tests, GPA minimums, the number of family members in college, and where the student plans to live during college—for example, at home, on campus, or off-campus with roommates. States can mitigate these data challenges by leveraging historical asset data from either the FAFSA or state financial aid applications to create a five-year asset average by income and family size. States would also have to make assumptions about the number of college students in the household.30 Similar to the asset data, states could leverage historical data to obtain an estimate.

Using family income data to generate a personalized estimate of college net price cannot guarantee that is what a prospective student would pay, because it does not ensure eligibility for financial aid, but it would provide far more accurate projection than existing financial aid outreach mechanisms. Furthermore, these kinds of projections are used elsewhere, with appropriate caveats—the SSA retirement benefit estimate letter, for example, provides projections and indicates this information does not guarantee the person will receive the estimated benefit amount. Similar to the SSA estimated benefit letter, this financial aid information will give families an idea of they could expect for the future, but not a guarantee.

Method of Delivery of Information

Each state must decide the best delivery method for communicating this information. While email is cheaper and faster, there are many rural areas that do not have reliable access, or even any access to the Internet.31 On the other hand, the issue with a mailed letter is that people move: Michigan, for example, encounters this with their college financial aid outreach program for Medicaid recipients, in which many letters are returned because the recipient no longer lives at the address on file.32 In order to get the most coverage, states should send both emails and mailed letters.33 States will also need to decide on the design and branding of materials to ensure the communication looks authentic, as previous studies have found that financial aid messaging may be ignored or viewed as fraudulent when sent from an unrecognized source.34 The best way to determine the design and branding is to conduct focus groups with parents and potential students.35 A program could even work in conjunction with middle schools, in which families would complete a very simple consent form that produces an estimate that teachers and counselors can use in discussions with families.

Data Privacy and Security

Many states are already sharing income information and public program participation data across different agencies. This means they have the infrastructure and policies in place to handle such data and keep it safe. Additionally, all state taxation boards are already required to be in compliance with stringent IRS security standards, and are audited by the IRS every other year to ensure this compliance.36 When sharing state income tax data, the receiving agency should follow the same IRS standards. Key considerations in keeping these data safe include ensuring a secure physical space where the data is located, domestic location of servers for cloud-based storage, annual assessment of security software, limiting access to trained employees, and scrambling certain identifying information.

Putting Early Notification into Practice

In order to determine how this kind of data sharing could work, this section of the report looks at three states, all of which have different aid and tax systems, as examples of how an early notification might look: California, Michigan, and Texas.

California

California has some of the lowest in-state tuition prices at its public colleges and universities, and some of the most generous need-based financial aid programs in the country. The Cal Grant program covers tuition for almost 500,000 students, but has different requirements and award levels based on age, GPA, time out of school, and income and assets. To make things more complex, the institutions in the University of California (UC) and California State University (CSU) systems will often fill in the award gap for students who do not meet those complex requirements, or who still have a gap after receiving their award. Given the complexity of the system, a clear and early outreach system that provides net price estimates for community colleges, CSUs, and UCs, could be extremely impactful.

In fact, California has begun thinking about providing personalized financial aid estimates at scale. The idea to create a question on the state income tax form for financial aid information gained traction in California with the introduction of AB 1335. To make this idea a reality, legislation may be necessary, as state law allows sharing income tax information only in circumstances outlined in the code.37 The data the California Franchise Tax Board (FTB) would need to send to the California State Aid Commission (CSAC) includes name, adjusted gross income, number of dependent exemptions, time out of high school information, address, and email. To obtain time out of high school, the tax question should ask for dependents’ ages. FTB has teams to negotiate the data sharing agreement with CSAC. Lastly, CSAC would be charged with analyzing the data and sending out the letter or email.

A key consideration for this program pertains to undocumated students. California has one the highest undocumented populations in the country, and providing those students with relevant information should be a part of this outreach. Some undocumented families have an Individual Taxpayer Identification Number (ITIN), which is given to people who may or may not have legal status but do business in the U.S. and pay taxes. This means some undocumented families fill out the state income tax form and could receive financial aid information if they elected to have their information shared. However, as noted by a staff member at a California State University Dreamer Resource Center, many families may not consent to having their information shared, as they fear how it will be used and shared with other agencies. Outreach may be needed to assuage these fears. Dreamer Resource Centers currently work with parents to help them understand the benefit of filling out a tax form to help their child receive financial aid, as well as how their data will be used and not shared.38 Partnering with them may be useful.

Michigan

In Michigan, each state aid program offers different award amounts, ranging from $1,000 to all tuition and fees at a community college. Each also has different requirements. For example, the competitive scholarship requires students to demonstrate financial need and have an SAT score of at least a 1200, whereas the tuition grant only requires demonstrated financial need. Michigan’s Tuition Incentive Program (TIP) is the one program that has the most clear definition of financial need, as it is designed for students who are Medicaid recipients. Moreover, institutions across the state offer a wide range of institutional aid and “Promise Zone” free community college programs. All of this means that connecting aid programs to institutions’ net price calculators would be critical for providing clear information for potential recipients, but additional caveats may be necessary, given the merit requirements of state programs and the varying ways that individuals campuses distribute institutional aid. Even with the caveats, state financial aid leaders such as the Michigan College Access Network see this kind of information as important to inform students and their families.39

Sharing income data would take place between two of Michigan’s state departments: the Department of Treasury and the Office of Postsecondary Financial Planning (OPFP). Given OPFP is located within the Department of Treasury, they can easily share income data. However, OPFP may need an infrastructure upgrade to handle a large dataset.40

Michigan already uses existing public benefits data for financial aid determinations, which could serve as a model.

Michigan already uses existing public benefits data for financial aid determinations, which could serve as a model. TIP provides tuition assistance to students enrolled in Medicaid. OPFP mails annual letters to students on Medicaid starting at the age of 12 to inform them of their TIP eligibility. They send these letters until a student’s senior year, sending about 300,000 letters last year.41 To obtain the Medicaid participation data, they have an interagency agreement with their health and human services department who sends a list of all students on Medicaid via a secured server to OPFP, who then analyzes and sends out the letters.42 About 50 percent of eligible students in the Class of 2019 have completed the necessary tasks to receive TIP money.43

Texas

Texas is one of seven states without a state income tax, and so the state would have to rely on other existing state programs to engage in similar outreach. Texas has one of the largest longitudinal data systems, the Texas Student Data System, which contains data from pre-K to workforce. The Texas Education Agency oversees the data governance and is responsible for the K–12 data. One potential data point to leverage from this system is the economically disadvantaged flag (defined as free and reduced lunch, SNAP, TANF or other public assistance eligible) for K–12 students.44 This data could be shared, as rules under The Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act (FERPA) allow a school to share student data if the data will be used for financial aid purposes.45

The Texas Higher Education Coordinating Board (THECB) would be the natural leader for an effort like this in Texas,46 as they have a long track record of data sharing and the necessary infrastructure in place.47 The data points they would need are student ID, their economic disadvantage status, and zip code. The analysis would be relatively easy to conduct, as it would only require assessing which students receive free or reduced price lunch, or are considered economically disadvantaged for other reasons. Having the three different options of the economically disadvantaged flag will help gain a better sense of a student’s family income since there are different income thresholds for free lunch or reduced price lunch.

The state has a range of other options. Middle and high schools could send a form to parents electing to have their wage data shared with the THECB to obtain financial aid information. The state would then leverage the existing memorandum of understanding between the THECB and the Texas Workforce Commission for obtaining student-level quarterly wage data for college students that allows for approved ad hoc projects—an early financial aid notification program could qualify as one.48 The THECB could also partner with the Texas Workforce Commission to identify application forms where a consent question can be added; alternatively, a question can be added on applications for public benefit programs.

The majority of Texas need-based aid is given to institutions as a block grant, with the institutions having the discretion to determine eligibility, meaning financial aid is decentralized. In order to combat the challenge of campus-specific criteria for aid eligibility and award levels, it would be particularly important to integrate net price calculators into the process, and to work with colleges to obtain accurate localized descriptions of aid programs.

Conclusion

Misinformation about the cost of college is keeping many low-income people out of college or from accessing aid when they do enroll. Information alone will not lower net price, and states should do more to lower overall college costs. But alongside those efforts, states can do more to make sure their residents know about existing aid availability. Leveraging state tax income data—or other low-income proxies in states that do not have an income tax—can help families know if they might be eligible for state aid. Providing families with information and the message that college can be affordable may move the needle on college enrollment while lowering costs for low- and moderate-income families.

Notes

- In April 2018, The Century Foundation released a report recommending an overhaul to the Cal Grant system after interviewing over fifty Californian stakeholders, including representatives from college access organizations, K–12 education, the higher education segments, several state agencies, the legislature, and others. See Robert Shireman, Jen Mishroy, and Sandy Baum, “Expanding Opportunity, Reducing Debt: Reforming California Student Aid,” The Century Foundation, April 4, 2018, https://tcf.org/content/report/expanding-opportunity-reducing-debt/.

- U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics, High School Longitudinal Study of 2009 (HSLS:09), Base-Year, First Follow-up, 2013 Update, and High School Transcripts Restricted-Use Data File, accessed from https://nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/d18/tables/dt18_302.43.asp?current=yes.

- “What College Costs for Low-income Californians, “ The Institute for College Access and Success, https://ticas.org/files/pub_files/what_college_costs_for_low-income_californians_0.pdf.

- “Why Didn’t Students Complete a FAFSA?” U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics, https://nces.ed.gov/pubs2018/2018061.pdf.

- Anna Helhoski, “How students missed out on $2.3 billion in free college aid,” NerdWallet, October 9, 2017, https://www.nerdwallet.com/blog/loans/student-loans/missed-free-financial-aid/.

- Laura Horn, Xianglei Chen, and Chris Chapman, Getting Ready to Pay for College: What Students and Their Parents Know About the Cost of College Tuition and What They Are Doing to Find Out (Washington D.C.: U.S. Dept. of Education, Institute of Education Sciences, National Center for Education Statistics, 2013), https://nces.ed.gov/pubsearch/pubsinfo.asp?pubid=2003030.

- Laura Perna and Patricia Steele, “The Role of Context in Understanding the Contributions of Financial Aid to College Opportunity,” Teachers College Record 113, no. 5 (2011): 895–933. For a full review on financial aid awareness see Casey George-Jackson and Melanie Jones Gast, “Addressing Information Gaps: Disparities in Financial Awareness and Preparedness on the Road to College,” Journal of Student Financial Aid 44, no. 3 (2015): 202–34.

- Ryan Hahn and Derek Price, “Promise Lost: College-Qualified Students Who Don’t Enroll in College,” Institute for Higher Education Policy, November 2008, http://www.ihep.org/research/publications/promise-lost-college-qualified-students-who-dont-enroll-college.

- Thomas Kane, The Price of Admission: Rethinking How Americans Pay for College (Washington, DC: Brookings Institution Press, 1999).

- Susan Dynarski, “Does Aid Matter?: Measuring the Effect of Student Aid on College Attendance and Completion ,”NBER Working Paper 7422, National Bureau of Economic Research, September 1999, https://www.nber.org/papers/w7422.pdf.

- Donald Heller, “Early commitment of financial aid eligibility,” American Behavioral Scientist, 49 (August 2006): 1719–38.

- Eric Bettinger, Bridget Long, Philip Oreopoulos, and Lisa Sanbonmatsu, “The Role of Simplification and Information in College Decisions: Results From the H&R Block FAFSA Experiment,” NBER Working Paper 15361, National Bureau of Economic Research, September 2009, https://www.nber.org/papers/w15361.

- Taryn Dinkelman and Claudia Martínez, “Investing in Schooling In Chile: The Role of Information about Financial Aid for Higher Education,” Review of Economics and Statistics, 96 no. 2 (2014): 244–57.

- Philip Oreopoulos and Ryan Dunn, “Information and College Access: Evidence from a Randomized Field Experiment,” Scandinavian Journal of Economics 115, no. 1 (2013): 3–26.

- “Halve the FAFSA,” National College Access Network, https://cdn.ymaws.com/collegeaccess.org/resource/resmgr/publications/halfthefafsa_2017.pdf.

- There is concern that parents who do not have time to find information are also unable to attend these events and are without any information. The state income tax data would help reach those parents.

- Benjamin Castleman, “Prompts, personalization, and pay-offs: Strategies to improve the design and delivery of college and financial aid information,” in Decision making for student success, eds. Benjamin Castleman Castleman, Sandy Baum, and Saul Schwartz (New York: Routledge Press, 2015).

- Giovanni Mastrobuoni, “Do Social Security Statements Affect Knowledge and Behavior?” Center for Retirement Research at Boston College, 2011; Barbara Smith and Kenneth Couch, “How Effective Is the Social Security Statement? Informing Younger Workers about Social Security.” Social Security Bulletin 74, no. 4 (2014): 1–19.

- Anya Olsen and Russell Hudson, “Social Security Administration’s Master Earnings File: Background Information,” Social Security Bulletin 69, no. 3 (2009).

- Carol Webster, Dario Longhi, and Liz Kohlenberg, “No Wrong Door: Designs of Integrated, Client Centered Service Plans for Persons and Families with Multiple Needs,” Washington State Department of Health and Human Services, Report 11.99, 2001, https://www.dshs.wa.gov/sites/default/files/SESA/rda/documents/research-11-99.pdf.

- Data Sharing Improves Service Delivery in Washington State,” The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, https://www.samhsa.gov/homelessness-programs-resources/hpr-resources/data-sharing-improves-service-delivery, accessed July 15, 2019; NWD programs tend to be larger undertakings where at least three different public programs are combined into one data portal. Because of this it is not surprising some technical issues have occurred, such as New Mexico’s system accidentally kicked off families from various social programs. See Ed Williams, “New Mexico Benefits System is Riddled with Errors. How this Affects Thousands in Need,” Las Cruces Sun News, January 10, 2019, https://www.lcsun-news.com/story/news/local/new-mexico/2019/01/10/benefits-system-aspen-searchlight-new-mexico/2530130002/.

- For more information on direct certification and categorically eligibility, see “USDA Food and Nutrition Services Child Nutrition Programs’ Eligibility Manual for School Meals Determining and Verifying Eligibility,” July 18, 2017, https://fns-prod.azureedge.net/sites/default/files/cn/SP36_CACFP15_SFSP11-2017a1.pdf.

- See “Application, eligibility and certification of children for free and reduced price meals and free milk,” 7 CFR §245.6(b)(4), https://www.law.cornell.edu/cfr/text/7/245.6.

- For more information, see the California Department of Education website page on Direct Certification, https://www.cde.ca.gov/ls/nu/sn/directcert.asp.

- SNAP income data is a reliable income source as it is never more than six months old and is rigorously verified. See Dottie Rosenbaum, Shelby Gonzales, and Danilo Trisi, “A Technical Assessment of SNAP and Medicaid Financial Eligibility Under the Affordable Care Act (ACA),” The Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, 2013.

- Cari DeSantis and Sarah Fass Hiatt, “Data Sharing in Public Benefit Programs: An Action Agenda for Removing Barriers,” Coalition for Access and Opportunity, 2012.

- Jennifer Douglas, “Overview of IRS Data Retrieval Process for 2009-2010, FAFSA on the Web,” U.S. Department of Education, Federal Student Aid, November 5, 2009, https://ifap.ed.gov/eannouncements/110509OverviewIRSDataRetrieval0910.html.

- “Filling Out the FAFSA Form,” U.S. Department of Education, Federal Student Aid, accessed August 1, 2019, https://studentaid.ed.gov/sa/fafsa/filling-out#irs-drt.

- About 76 million households fall below the threshold requiring them file. However, families who are eligible for the federal Earned Income Tax Credit would need to file a state tax form to earn the credit from the state—over 27 million taxpayers received the EITC in 2016, capturing about 35 percent of households who would not otherwise file. See “T18-0128—Tax Units with Zero or Negative Income Tax Under Current Law, 2011-2028,” The Tax Policy Center, last modified September 5, 2018, https://www.taxpolicycenter.org/model-estimates/tax-units-zero-or-negative-income-tax-liability-september-2018/t18-0128-tax-units; “EITC Recipients,” The Tax Policy Center, last modified October 1, 2018; https://www.taxpolicycenter.org/statistics/eitc-recipients.

- The most recent FAFSA application only asks this question of independent students.

- Andrew Perrin, “Digital Gap Between Rural and Nonrural America Persists,” Pew Research Center, May 31, 2019.

- Based on interview with the author and a representative from Michigan’s Office of Postsecondary Financial Planning.

- Both email and mailed letters may have their authenticity questioned. Previous studies found that financial aid messaging was ignored or viewed as fraudulent when sent in plain envelopes from an unrecognized source. See Sarah Goldrick-Rab, Robert Kelchen, Douglas Harris, and James Benson, “Reducing Income Inequality in Educational Attainment: Experimental Evidence on the Impact of Financial Aid on College Completion,” American Journal of Sociology 121, no. 6 (2016) :1762–817; Caroline Hoxby and Sarah Turner, “Expanding college opportunities for high-achieving, low income students,” Stanford Institute for Economic Policy Research Discussion Paper No. 12-014, 2013. This could also occur with email with the various scam emails and viruses. To combat these issues, states may need to partner with colleges to use their logos to make mailings and emails look more authentic. This may be easier in some states that have limited systems, such as California, which only has three.

- Sarah Goldrick-Rab, Robert Kelchen, Douglas Harris, and James Benson, “Reducing Income Inequality in Educational Attainment: Experimental Evidence on the Impact of Financial Aid on College Completion,” American Journal of Sociology 121, no. 6 (2016) : 1762–817; Caroline Hoxby and Sarah Turner, “Expanding college opportunities for high-achieving, low income students,” Stanford Institute for Economic Policy Research Discussion Paper No. 12-014, 2013.

- Guidelines for readability state that documents should use short sentences, avoid jargon, use the active voice, start sentences with action verbs, and make information visually accessible through bullet points. Focus groups for the Social Security Estimated Benefit letter found that people wanted the benefit estimate information at the beginning, less numbers used, have more white space on the pages, and use different fonts to find information easier. Following these principles is especially important for families whom speak English as their second language.

- “Publication 1075: Tax Information Security Guidelines For Federal, State and Local Agencies: Safeguards for Protecting Federal Tax Returns and Return Information,” U.S. Department of the Treasury, Internal Revenue Service, 2016, https://www.irs.gov/pub/irs-pdf/p1075.pdf.

- See Ca. Rev. and Tax Code Ann. Division 2 (10.2)(7).

- Interview, Dreamer Resource Center. Any aid estimate communications to undocumented students must make it clear that they are only eligible for tuition aid and not non-tuition costs, to ensure they understand what is available to them.

- Based on interviews with author and various Michigan education leaders, including Michigan College Access Network.

- Based on interview with author and a representative from Michigan’s Office of Postsecondary Financial Planning

- The total cost of this effort is about $100,000, based on interview with author and a representative from Michigan’s Office of Postsecondary Financial Planning

- It takes the OPFP a few weeks to analyze the data and letters are sent out in late January/early February. Based on interview with author and a representative from Michigan’s Office of Postsecondary Financial Planning.

- This assessment is based on information from mid-July 2019 and students still have a few more weeks to complete their tasks to participate in TIP. SFFB believes they are on track to have 60 percent of eligible students to participate.

- Texas have been collecting this data since 1988 and the data definition was last updated in 1997. See “2019–2020 Texas Education Data Standards (TEDS): Section 4, Description of Codes: Post-Addendum Version 2020.2.1,” Texas Student Data System, August 26, 2019, 105, http://castro.tea.state.tx.us/tsds/teds/2020A/teds-ds4.pdf.

- See “Under what conditions is prior consent not required to disclose information?” 34 CRF 99.31(a)(4)(i)(a), https://www.law.cornell.edu/cfr/text/34/99.31. TheTexas Education Agency states that their legal department reviews all requests on sharing economically disadvantaged data, especially FPRL, so there are policies in place in sharing this data.

- The program would fit with their 60x30TX initiative to increase the number of Texans with a postsecondary credential by 2030While THECB currently does not have access to student addresses to send the letters, they do have the capacity to analyze the data—it would only take a 0.25-0.50 FTE to complete this taskBased on interview.

- Based on interview with author and a representative from the Texas Higher Education Coordinating Board.

- Based on interview with author and a representative from the Texas Higher Education Coordinating Board.