Now nearing the end of its seventh year, the Syrian civil war has killed almost a half-million people and displaced over half the country’s population. More than five million Syrians are currently living outside their homeland as exiles, refugees, and émigrés. Most of them never knew a president who wasn’t an Assad, or lived under a political order other than that of the ruling Ba’ath party. For many, the uprisings in 2011 activated a sense of national belonging stronger than anything they had ever experienced in their lives. Maher Isper, a Beirut-based Syrian political activist who spent six years in prison before the uprisings, said he “got to know the real Syria just in the last few years, since the revolution.”1 But whether by force or by choice, Maher—along with many of his former compatriots—may never return.2

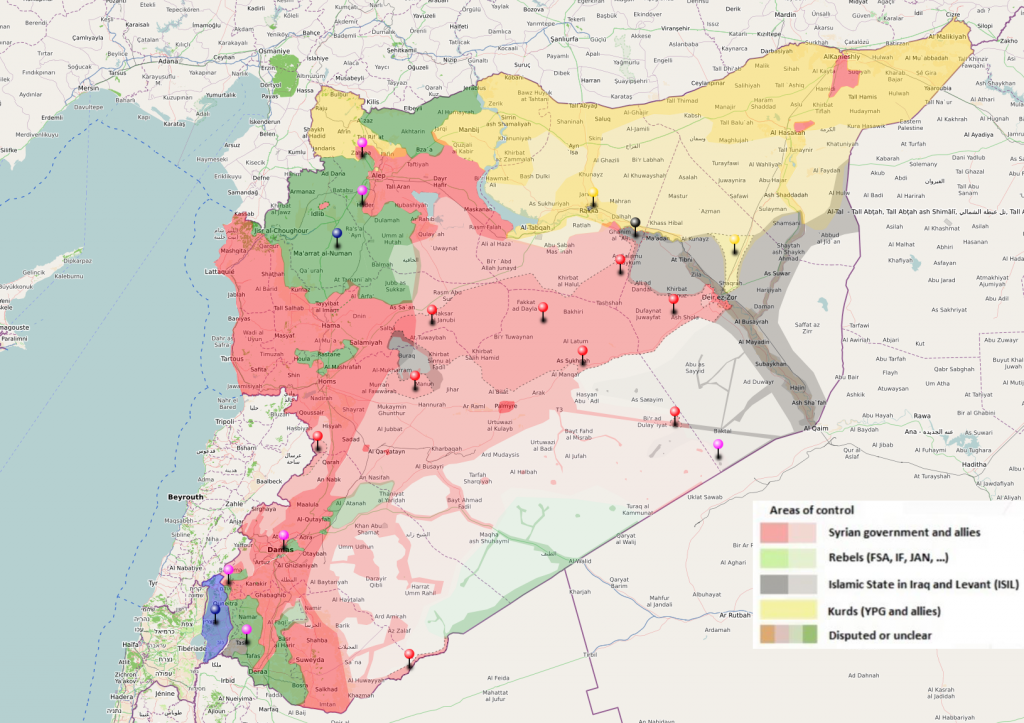

In September of this year, Assad’s allies, Hezbollah and Russia, declared impending victory for the regime after it had regained control of most of Syria’s territory.3 “Your real interest lies in returning to your country so that you can protect it and help in rebuilding it,” Hezbollah’s Secretary General Hassan Nasrallah told Syrian refugees in Lebanon during a speech in early October.4 But Syrians of all stripes argue that unity and national belonging are necessary to rebuild, and both seem out of reach in a country now cut everywhere across sectarian-ethnic divides. And return is not so easy for the millions of Syrians living in exile, regardless of their politics: not for those with opinions intrinsically at odds with the regime’s, nor for apolitical or pro-Assad Syrians who fled violence and no longer have homes to return to.

This report showcases the voices of Syrians who left because of the war, for whom national belonging is a complex sentiment. Extended narrative interviews over the course of three months with Syrians living in Lebanon, Europe, and the United States reveal a multitude of viewpoints but a common conviction that there is no place for them in their homeland’s future. Some say that the failure of the uprising shattered their hopes for a more inclusive government, active civil society, and engaged public debate in Syria. Others, who spoke favorably of life under the Assad regime, hold expired passports, are afraid to return to Damascus to try to renew them, and believe that their homes have either been destroyed or taken over by new families brought in with the government’s consent. Indeed, in a recent speech Assad seemed content that the past six and a half years of war had rid the country of the bad seeds; he seemed to suggest he’d prefer most refugees never return. “We lost the best of our youth and our infrastructure,” he said at a conference in Damascus in late September. “It cost us a lot of money and a lot of sweat, for generations. But in exchange, we won a healthier and more homogeneous society in the true sense.”5

This report does not aim to represent a full cross-section of Syrians who have left the country because of the war. Interviewees were selected in order to capture views that are both pro- and anti-uprising, as well as those that are more neutral; to represent disparate religious and socioeconomic backgrounds; and to include both rural and urban perspectives from different regions of the country. The interview questions were designed to explore what remains of interviewees’ sense of national belonging, in order to examine the relationship between nationalism and citizenship, and to inquire into nationalism under conditions of exile.

While more descriptive than prescriptive, these exiles’ responses have policy implications for both the diaspora and for those who want to rebuild Syria. The interviews reflect a Syrian populace abroad that is fragmented, exhausted, and for the most part operating in survival mode. We encountered little motivation to unite and push on for change in the face of Assad’s impending military victory.

The report begins with reflections from interviewees, who have now spent years outside of Syria, on life under the Assads (father and son) before the uprising. It then explores their widely different views on 2011, which was for some a joyous turning point and for others a nightmare. All our interviewees said that, for better or worse, the events over the past six and a half years have brought to the surface topics that were for years forbidden, like religious differences and political ideas outside of the Ba’ath doctrine. The concluding sections include their thoughts on the future for exiles, and for Syria as a nation. Although the overall sentiment of our interviewees was despairing of the country’s future, some suggest that the experience of the past six and a half years may yet lead to a more impassioned sense of national identity among exiles, similar to what has developed among Palestinians. Some believe that the Syrian government will not be able to ignore its citizens abroad forever—even if it refuses to renew their passports.

Listen to Moustapha, a twenty-eight-year-old from Aleppo now living in Germany, talk about the huge divides in Syria today.

Forbidden Politics

To gauge what is possible in Syria’s coming phase, it helps to understand the brand of sectarianism and political suppression instilled by the Assad dynasty’s Ba’athist regime, and how potent those ideas remain today as frames of reference, even for anti-regime exiles.

The Assads enforced a nominally secular, pan-Arab brand of nationalism in a country with great diversity: the majority of Syria’s population are Arab Sunni Muslims, but there are also Muslims from the Alawite, Ismaili, and Shia sects, plus a sizeable Christian minority and a small Druze community. There is also a non-Arab population that includes Kurds, Armenians, Yazidis, and others.6 Loyalty to any of those sub-state identities was discouraged and in some cases even outlawed under Ba’athism even before Hafez came to power.7 Mazen Izzi, a thirty-six-year-old Syrian journalist at Al Modon newspaper now living in Lebanon, suggested that he hadn’t ever understood why these differences were never discussed before the uprisings, as though they didn’t exist:

You know this topic, about what it is to be Syrian? I always wonder: what is it that brings together one person, in this current Syria, a person with a group in Dera’a [where the revolution started], with another person that works in the regime air intelligence? What is the link between members of a municipality in the [Druze] village of Suwaida with an employee in the Kurdish offices in Amouda? What is it? What brings them together? It is time to ask these questions.8

Maher Isper, who is part of the minority Ismaili branch of Shia Islam, said that some people had discussions around identity behind closed doors, but never in public. Maher, thirty-five, found an outlet to share his thoughts about identity and society in online forums in the mid-2000s, before Bashar al-Assad cracked down. He was put in jail in 2005 because of his participation in the online debates:

You were not allowed to talk about sect or about these different identities that were not just “the Arab identity.” We were not sectarian because we were not allowed to be. It was banned to be that.… People would raise their children with the premise that you’re not allowed to talk about these things. At all.9

Listen to Maher Isper, director of the Beirut-based think tank Development Integration Network, discuss the regime’s prohibition on talking about sub-state identity.

Loubna Mrie, a twenty-six-year-old Syrian who fled to Turkey in 2012 and is now seeking asylum in the United States, recalled growing up in the “divided” city of Jableh, situated in the Alawite province of Latakia, on Syria’s Mediterranean coast. Loubna’s father, uncles and cousins founded the provincial chapter of pro-regime thugs known as shabiha:10

Jableh was Sunni and Alawite, but they don’t really mix. In ninth grade I fell in love with a Sunni guy, and then my whole family went crazy.… It was like, “you don’t talk to Sunni men because they are not good”.… [especially] if you’re an Alawite from a well-known Alawite family.11

On the other hand, Khaled Hassan Ahmad, a forty-seven-year-old farmer living in a refugee settlement in Lebanon’s Beka’a Valley, described himself as apolitical and spoke positively about the perceived lack of sectarianism in Syria before 2011. He blamed the uprisings for bringing such divisions to the surface:

Before, if there was someone who was Shia, Sunni, Christian, Alawi, we never looked at people in that sense, that’s not how we classified people.… We didn’t really talk about any of these differences because they didn’t exist, in a way, even when we knew this person was this or that, it wasn’t even an issue to discuss. But then this [unrest] happened and now we feel excluded because now there are these differences that we don’t think existed.12

Political debate was also forbidden and enforced through the suppression of dissidents who might “weaken nationalist sentiment” like Yassin Al-Haj Saleh,13 a prominent intellectual who was imprisoned for sixteen years under Hafez al-Assad. Saleh, who has been living in exile in Turkey but is a fellow this year at the Institute for Advanced Study in Germany, says the regime enacted a “complete political and intellectual homogenization” of Syria.14 After Bashar came to power in 2000, there was a brief period of hope for change, known as the “Damascus Spring.” Successive attempts at open political debate between 2000 and 2011 were permitted for a short time and then dismissed, resulting in the imprisonment and exile of opposition leaders who came to learn that Bashar would be just as ruthless as his father.

It was around that time that online forums and blogging became popular in Syria, and Moustapha (who asked us to use only his surname), a twenty-eight-year-old from Aleppo now living in Germany, recalled that the forums were “very vibrant” with intellectual debates between Islamists and secularists. But when one of the forums became too bold in its political critique, someone told the intelligence services, who found the administrator and forced him to shut it down. Moustapha said political conversations at Aleppo University were rare. “The Syrian students were very careful,” he said. “Even the closest people to you you wouldn’t know what their political opinions are.”15

A “Coming Out” of Identities

In exile, some Syrian communities have engaged in debate, discussion, and experimentation, continuing the conversation about identity and belonging that began during the uprising. For them, the uprisings marked a spontaneous enactment of national belonging, a supernova that later collapsed into a black hole. The uprising rekindled the hope that had begun with the Damascus Spring, though the regime’s swift crackdown quickly quelled those expectations.16 Journalist Mazen Izzi remembers that the ideas shared during the Damascus Spring “were related to an inclusive Syria, a Syria that does not differentiate between its citizens, a democratic Syria.” In 2011, Mazen said, “politics regained its moment.” He admitted that the war opened a can of worms, wherein “hatred became public and people talked about these sensitivities out in the open”:

The only moment I felt I belonged to this country really was the moment of 2011. There was a golden moment…when people momentarily surpassed those sensitivities.… That was our biggest shock, that Syria is completely different from what we knew. We knew its fake form.17

Moustapha echoed Mazen’s sentiments, saying the only Syria he feels he has a connection to is the “Syria of 2011…. There was a presence of the self,” he said, “something real.” He contrasted it with the Assads’ four-decade-long repression and added, “it wasn’t something that was fabricated, it wasn’t deceitful.” Moustapha is one of many Syrians living abroad who work with local humanitarian organizations in which conversations around politics and identity are central. He is an officer at the Syrian NGO Basmeh & Zeitooneh, which has set up community centers to provide direct assistance, information, and job training for Syrian refugees in Lebanon since 2012. Similar to the kind of vibrant blogging community that developed in the mid-2000s, Moustapha said Basmeh & Zeitooneh provides room for democratic interaction among Syrians—room that doesn’t exist inside Syria.

“There is a democratic space there,” Moustapha said. “I can talk about anything I want [and] the other thing is the diversity, Syrians from different places, with different ideologies.”

Activist Maher Isper, who said he “got to know the real Syria” in 2011, is now director of the Development Integration Network, a Syrian think tank in Lebanon. He called 2011 a “coming-out of primary identities that existed before being Arab.” Ethnic and religious communities rose to reject an imposed “Arab” identity, and discussed “belongings that came before nationalism.” Maher said 2011 was a “euphoric moment.” The regime and the Ba’ath party had held a monopoly over discussions of identity throughout the whole of Syria’s modern history, he said, and all that came before that is a blur. For the first time, in 2011, people were able to discuss different identities.18

Listen to Maher recall learning about the Arab uprisings while in prison, through the lens of Syrian government newspapers.

In 2005, the Assad regime sentenced Maher to six years in Saydnaya Military Prison19 because he was part of a secular group that started a blog to promote freedom of speech and the press. He was released when Bashar issued a general amnesty to political prisoners in 2011.20 A month into the uprisings Maher was summoned by state intelligence, and so he escaped to Lebanon. He believes that anyone who held onto democratic views was seen as a bigger threat to the survival of the regime than were Islamists. As long as the current intelligence regime remains, Maher cannot go back to Syria. But he still fantasizes about a state of harmonic diversity in Syria without difference. Before the regime, what made Syria unique, he says, was that:

You have all of these communities that lived among one another and there was no animosity between them. Each had their own neighborhood, their own hamlets, but the kind of connections that would happen among and across these communities was not a struggle, it was more harmonic.21

For now, Maher likes life in Lebanon, and prefers it to life in any other country. He appreciates that in Lebanon he can find spaces of cross-sectarian interaction, the same kind of interaction he had experienced when he was part of the blog. “What united us [in the blogging community] was that we were all so free. We didn’t care about these little things,” he said.

Apolitical Citizens

But Syrians were not a monolithic polity before 2011. In addition to people who oppose the regime, there are many displaced who would have preferred life to continue as it was, but are now unable to return. They do not refer to the events of 2011 as a revolution, and they say that questions of identity are irrelevant when compared to life’s necessities of stability, security, and survival. The Assad regime had built a functioning government and social service network that benefited many of its citizens, and belonging was based on a tacit arrangement with the state: complacency in exchange for safety, security, and the daily comforts of being apolitical.

Two interviewees from Qusayr, a village outside of Homs that was largely destroyed in 2013 when forces from the Syrian army and Hezbollah regained control from rebels, spoke positively about their life in Syria while lamenting the fact that they are not welcome back. Khansa Abdelhamid Alhamoud and Khaled Hassan Ahmad, two of the 360,000 Syrian refugees living in informal tented settlements in Lebanon’s Beka’a Valley,22 both said that they never had anything to do with the protests and did not have any complaints about the Assad regime. Khansa and her family fled empty-handed from Qusayr, and she hasn’t heard from her father since he was detained at a checkpoint near the border when they crossed. She was wistful about her life back Syria, which stood in stark contrast to her current difficult existence in Lebanon:

I was very happy. I lived a normal life, I didn’t have to worry about day-to-day problems, I didn’t have to worry about providing my provisions in life. I went to school. I was studying English language. Even when the crisis started, in the first couple of years, it didn’t really touch us that much because we were part of the countryside. But then afterwards by God’s will it got to us because our village became a very important border area.… We were forced to leave, it wasn’t our own decision.23

Listen to Khansa, who lives in a refugee settlement in Lebanon, explain the dilemma of holding an expired Syrian passport.

Khaled, the farmer who lives in an informal settlement in the town of Bar Elias, echoed Khansa’s sentiments about life in Syria. He lost two sons and suffered a head injury in a bombing in June 2012. He was evacuated while unconscious, and woke up in Lebanon:

At the beginning we were very happy, we were very comfortable. We had agricultural lands. Everything was provided for us in terms of the basics and all that we had to do was to be there and work. We were very safe.… We didn’t participate in anything that had to do with politics. Politics wasn’t something that we had to think about. All that I cared about personally was my dignity and my land.24

“What Revolution? It’s Chaos”

Musician Tarek Khuluki, twenty-seven, moved from Damascus to Beirut after the uprisings began but says his motivation was not political; he and his bandmates from Tanjaret Daghet (“Pressure Cooker”) wanted to be in a city with more cultural freedom and diversity, where they could record and have a future in the music industry. Still, Tarek was not active in the uprisings and scoffs at the term “revolution:”

What revolution?… It’s chaos what happened. It’s like a nightmare for me. I just woke up hearing that people were getting killed and no one even asked me, “What’s your opinion,” you know? It’s like something beyond me. And this is when I realized that it’s not a revolution. Because if it’s a revolutionary move, it should come from the people who can speak… It’s a bunch of people just fighting for stuff that doesn’t belong to them.25

Listen to Tarek and bandmate Khaled Amran’s reaction to being asked about the “revolution.”

For Tarek, who thinks of himself as a modern-day flâneur and a citizen of the world, the 2011 uprisings were an inconvenience. Although the band’s songs discuss economic hardships,26 and the struggles of youth today, their enterprise is essentially about letting off steam.27 He spoke of how metal and rock bands were targeted by the Assad regime and admitted that the 2011 uprising did break a wall of fear, but he said that it eventually turned into a bloodbath that led to more and more division.

“We just woke up and started to see people being divided—I’m with, you’re against, I’m black, you’re white,” Tarek said. “And before it was not like that.”28

Similarly, for Khansa and Khaled from Qusayr, the “revolution” was a moment of chaos, shock, and senselessness, resulting from an ungrateful child’s pipe dream. The 2011 uprising was impulsive and foolish, they thought. Questions of identity do not factor into their daily hardships of getting by. Khansa said she did not participate in the protests, and when we asked her if she was surprised that they became violent, she said:

We didn’t have the chance to think about any of this because of the amount of bombings, the missiles that were being dropped—at one point we had to dig in ten–sixteen meters under our buildings so that we could sit there for three weeks, we didn’t see the sun, we didn’t see the light.29

Both Khaled and Khansa said the last thing they expected was for this protest wave to reach Syria. They think of 2011 in relation to the humiliating condition they are in now. The uprising denied them of their dignity and of their land, imposed politics on them, and handed them a burden they never asked to carry. It may not be Syria they miss, but the normalcy it provided instead, and the family they lost to the war. While the fact that “everything belonged to the state” was a prison for some, it was a source of comfort for Khansa. For Mazen Izzi, “hating the regime was our only welding agent…. We were united through our common repression from the regime, but it wasn’t an honest unity”; but for Khansa, the state was a “welding agent” in a positive sense.

A Fragmented Diaspora

Almost all of our interviewees said that the opposition living abroad is fragmented, and that activists are unable to regroup at this point in time. Moustapha insisted that it wasn’t indifference, but rather the fact that “people have paid such a high price and now they’re worn down. They’re more concerned about achieving things on an individual level and not on a collective level.” Referring to exiled Syrians that participated in the uprisings, Moustapha said, “There is a sense of alienation if you want to talk about the nation compared to before when the nation was something so near and so close.… Today there are many Syrias, and they are all islands.”

But Moustapha still holds onto the hope, even when he feels defeated, that one day his work with Syrian civil society organizations in exile will help to serve his Syria. “I think today the problematic that we have—the conflict that exists—is one of abandonment,” he said. “People who had participated in the revolution and the process and the movement are all in Europe.”30

Bissan Qassim, one of the half-million Palestinian refugees who had made a home in Syria, made a similar comment. Bissan did humanitarian work in Palestinian camps in Syria during the first five years of the conflict and was traveling back and forth between Lebanon and Syria before she eventually sought asylum in the Netherlands just this year.

“For me the war is after the war. It is not now,” Bissan said. “It is the effects of the war—for example, my team inside Syria. Every month they are different. There is no emotions at all. When you are there it becomes so tough.”31

Listen to Loubna talk about Syria’s younger generations living through the war.

Mazen, conversely, thinks that the urban, progressive, and liberal-leftist middle class that was supposed to carry this revolution, himself included, are a cowardly and defeated class. He has decided to sever his ties with Syria, and said he believed that “they [the Islamists] are the true owners of the cause and we are merely observers on the margin.” Maher too took the long view when it comes to the “ravaging forces” that would remain in Syria even if the regime were to be deposed:

I’m not a dreamy person. I have to be realistic. I think there’s going to be a very long period before things stabilize in Syria. Even if we remove the regime there are so many social forces that are in conflict now, and even when you remove the regime you’ll still have remnants of the civil war in terms of the social differences that have been created. Even if the regime was deposed, or even if it took another form, what is inevitable is that there will be a lot of ravaging forces that will remain in Syria, and what needs to be done in the future, as in an ideal vision, one, you need to establish freedom, and also you need to transfer the differences at the ground level in terms of war and put them in the political field. That takes around twenty to thirty years probably.32

Unwanted by the Homeland

Exiled Syrians are confused about how to feel towards the unwelcoming nation to which they once belonged, and, for many, the only to which they will ever belong. Still, as Edward Said eloquently put it in his essay Reflections on Exile, “all nationalisms in their early stages develop from a condition of estrangement.”33 The war has completely overturned the lives that many displaced Syrians imagined for themselves, but exile is also a process of reinvention. The alienation has made room for reflection. For almost all of our interviewees, return is no longer an option, at least not anytime soon; but not all see exile as the end of the road. Some are more forward-looking than others.

Bissan says her experience as a Palestinian refugee gave her a greater sense of national identity as a Palestinian, and she thinks that the experience of being refugees may do the same for Syrians. Bissan said that “after the war, at least Syrians now have a cause to believe in and fight for.”34 Scholars Ola Rifai and Raymond Hinnebusch believe that the fact that Syrian statehood was so valued throughout the war means that a new Syrian national identity may be “rising out of the ashes of an exhausted Ba’athism.”35

Zaki Mehchy, a founder and researcher at the Syrian Center for Policy Research, says that keeping a connection with the nation is not contingent on physically being there, but on having the goal to rebuild it in everyone’s image.36 For him, belonging is nothing without a goal or a cause. How our pro-uprising interviewees recall the Syria of 2011 is indicative of what they hope for in a post-war Syria scenario. For the time being, however, some have replaced that with a fantastical concept of the nation.

Still others remain pessimistic about the future of Syria, and about their own chances of returning. Khansa and Khaled from Qusayr, who were not critical of Assad and longed for their lives as they were before the uprisings, believed that their homes had been either destroyed or taken by loyalists. Explaining how people in her refugee settlement talk about the future, Khansa said that “some people are depressed, some people don’t know if they’re going to go back or not…. They say we won’t go back but we hope our children can. The future is far away. Hope is far away.”37

Listen to Khansa lament the lack of hope she and the other refugees in her settlement have about returning to Syria.

Khaled was even more despondent:

Safety has gone. Security. That’s not existent anymore. It’s impossible for me to come back to the old Syria. It’s completely gone. I don’t even have the same craving anymore because I don’t have the same things I used to have there. I’ve lost so many people there and if I go back it’s not the same. If I were to count the number of people that I have lost, it’s unimaginable. Nothing’s going to be the same, it’s impossible.38

Loubna believes that if leaders actually want to start rebuilding the country, they “should have a system where all the people are welcome. While [under] the Syrian government, only their people will be welcome. And we’ll end up with the same tragedy”:

The future of Syria—it’s gonna be horrible. We lost so many people and both sides committed so many crimes that it’s impossible in the near future to have the country united again. Because it will take years for the next generations to forget and forgive what happened.39

Post-War Syria

Today’s debates on Syria’s future are centered on physical and economic reconstruction. The rallying calls of 2011 for democratic and inclusive governance now echo the interests of the “Friends of Syria” group, an alliance of mainly Western and Gulf countries, who say reconstruction support must hinge on a “credible political process leading to a genuine political transition that can be supported by a majority of the Syrian people.”40 But Syria is prioritizing aid from donor countries like China and Russia that are unlikely to condition aid on political reforms.41 On the contrary, they would help rebuild the country in the image of the regime and its international and regional patrons. Deeply committed at the outset of the war, the Friends of Syria now seem resigned to letting this happen.42

Jihad Yazigi, a renowned Syrian economist and founder of the Syria Report, has called for a decentralized political system in Syria that recognizes sectarian and ethnic communities’ right to fair political representation and transfers power away from Damascus.43 That kind of system would eliminate the Ba’ath legacy of “don’t ask, don’t tell,” but it could very much risk institutionalizing sectarian-ethnic divisions, as is the case in neighboring Lebanon where warlords, business tycoons, and religious figures constitute the whole of an elite political class.44 They plaster over or capitalize on civil-war strife without the slightest regard for those that held on to a vision of the country based on ideals of citizenship, legitimacy, and pluralism. A similar fate could befall Syria where warlordism, crony capitalism, and the exclusion of civic advocacy groups continues to be the normal state of affairs.

Assad has made no apologies for what Syrian nationalism looked like before 2011. At this point in time it seems that its future will be similar to its past, with many of the same attendant problems and exclusions. Some of the diasporic Syrians interviewed for this report, like Loubna, Moustapha, Maher, and Zaki, say they will continue the discussion about how to reform Syria—but from a distance. They are not interested in returning to a Syria rebuilt in Assad’s image. At the same time, it is difficult to imagine what will become of Khaled and Khansa from Qusayr, apolitical subjects with expired passports stuck in limbo in Lebanon and yearning for homes that no longer exist in Syria. Just as these migrants consider their unwelcoming homeland, a future Syria will have to consider them.

The 2011 uprisings provoked a new, open debate about previously taboo subjects. Discussions that were once off-limits even in private suddenly flared into the open. A resurgent Assad regime has once again silenced public discussion of national identity and belonging, but a vigorous conversation continues in the Syrian diaspora. Many exiles insist that national Syrian identity in the future must make room for inclusive citizenship and openly contested politics. For now, however, Syria’s rulers have reestablished control over the national narrative, sidelining questions about identity and politics that were raised by the revolutionary opposition.

Many Syrians living outside their homeland say they will continue to debate identity, community, sect, and nationalism. They intend to challenge an exclusionary master narrative written by the Assad regime. However, the opposition has lost any tangible ability to challenge the government in Damascus, and seems limited for now to carrying on their fight in the realm of ideas and culture. For the foreseeable future, there will be competing Syrias, “islands” with different politics and national identities—one under Assad, and many beyond.

Notes

- Maher Isper, interview with the authors, Beirut, July 9, 2017.

- We will refer to our eight extended narrative interview subjects by their first names, with the exception of Moustapha, who requested that we use only his surname.

- Tom Perry and Katya Golubkova, “Hezbollah declares Syria victory, Russia says much of country won back,” Reuters, September 12, 2017, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-mideast-crisis-syria-hezbollah/hezbollah-declares-syria-victory-russia-says-much-of-country-won-back-idUSKCN1BN0YL..

- “Sayyid Nasrallah warns some from trying to drag the country into any confrontation: ‘Daesh’ is at its end and any division [of syria], if that were to happen, will definitely affect Saudi Arabia,” Alahednews, September 30, 2017, https://alahednews.com.lb/143093/7/السيد-نصرالله-حذر-البعض-من-محاولة-جر-البلد-الى-اي-مواجهة-داعش-في-نهايتها-والتقسيم#.WeTgYGhSxPa

- Ben Hubbard, “Syrian War Drags On, but Assad’s Future Looks as Secure as Ever,” New York Times, September 25, 2017, https://www.nytimes.com/2017/09/25/world/middleeast/syria-assad-war.html?_r=0.

- “Syria,” United States Central Intelligence Agency, The World Factbook, https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/sy.html.

- Radwan Ziadeh, “The Kurds in Syria: Fueling Separatist Movements in the Region?” United States Institute of Peace, Special Report 220, April 2009, https://www.usip.org/sites/default/files/kurdsinsyria.pdf.

- Mazen Izzi, interview with Sima Ghaddar, Beirut, August 3, 2017.

- Maher Isper, interview with authors.

- Loubna Mrie, “I Left My Family for the Free Syrian Army,” Vice, November 27, 2012, https://www.vice.com/en_us/article/qbwm73/i-left-my-family-for-the-free-syrian-army-000205-v19n11.

- Loubna Mrie, interview with Lily Hindy, New York, July 27, 2017.

- Khaled Hassan Ahmad, interview with authors, Bar Elias, Lebanon, July 10, 2017.

- Aurora Sottimano, “Nationalism and Reform under Bashar al-Asad: Reading the “Legitimacy” of the Syrian Regime,” in Syria from Reform to Revolt, Volume 1: Political Economy and International Relations, eds. Raymond Hinnebusch and Tina Zintl, (Syracuse, New York: Syracuse University Press, 2014), 71.

- Yassin Al-Haj Saleh, The Impossible Revolution: Making Sense of the Syrian Tragedy (London: C. Hurst & Co., 2017), p93-4.

- Moustapha, interview with the authors via Skype, July 8, 2017.

- For more on the periods of opposition activism under Bashar, see “Contesting Authoritarianism: Opposition Activism under Bashar al-Asad, 2000–2010,” in Syria from Reform to Revolt, Volume 1: Political Economy and International Relations, eds. Raymond Hinnebusch and Tina Zintl (Syracuse, New York: Syracuse University Press, 2014), 91-112.

- Mazen Izzi, interview with Sima Ghaddar.

- Mazen Izzi, interview with Sima Ghaddar. “The period before the ‘seventies is very blurry. They barely taught us anything before then. We don’t know much about the modern history of Syria, from the end of Ottoman empire up until the early seventies, that part of history is blurred. Because you know this is not history. You come to the modern history of Syria and you find large gaps.”

- “About Saydnaya,” Amnesty International, https://saydnaya.amnesty.org/en/saydnaya.html.

- Katherine Zoepf and Liam Stack, “To Much Skepticism, Syria Issues Amnesty,” New York Times, May 31, 2011, , http://www.nytimes.com/2011/06/01/world/middleeast/01syria.html.

- Maher Isper, interview with the authors.

- Racha El Daoi, “‘A sense of stability and safety is enough,’” Norwegian Refugee Council, May 9, 2017, https://www.nrc.no/news/2017/may/a-sense-of-stability-and-safety-is-enough–refugee-evictions-in-lebanons-bekaa-valley/.

- Khansa Abdelhamid Alhamoud, interview with the authors, Saadnayel, Lebanon, July 10, 2017.

- Khaled Hassan Ahmad, interview with the authors, Bar Elias, Lebanon, July 10, 2017.

- Tarek Khuluki, interview with the authors, Beirut, July 11, 2017.

- For an example of Tanjaret Daghet’s music, see “Ta7t El Daghet / Under Pressure (Official Music Video),” YouTube, August 6, 2013, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=k-lf9CIZ9OM.

- Janne Louise Andersen, “Letting off steam,” The National, November 9, 2013, https://www.thenational.ae/arts-culture/music/letting-off-steam-1.595780.

- Tarek Khuluki, interview with the authors.

- Khansa Abdelhamid Alhamoud, interview with the authors.

- Moustapha, interview with the authors.

- Bissan Qassim, interview with the authors via Skype, July 7, 2017.

- Maher Isper, interview with the authors.

- Edward W. Said, Reflections on Exile and Other Essays (Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 2000).

- Bissan Qassim, interview with the authors.

- Raymond Hinnebusch and Ola Rifai, “Syria: Identity, State Formation, and Citizenship,” in The Crisis of Citizenship in the Arab World, Eds. Roel Meijer and Nils Butenschon (Leiden: Brill, 2017).

- Zaki Mehchy, interview with Sima Ghaddar, Beirut, October 3, 2017.

- Khansa Abdelhamid Alhamoud, interview with the authors.

- Khaled Hassan Ahmad, interview with the authors.

- Loubna Mrie, interview with Lily Hindy.

- U.S. Department of State, “Joint Statement From the Ministerial Discussion on Syria,” September 21, 2017, https://www.state.gov/r/pa/prs/ps/2017/09/274356.htm; also see John Irish and Yara Bayoumy, “Anti-Assad Nations Say No to Syria Reconstruction Until Political Process on Track,” The Wire, September, 19, 2017, https://thewire.in/179063/anti-assad-nations-say-no-syria-reconstruction-political-process-track/.

- Benedetta Berti, “Is Reconstruction Syria’s Next Battleground?” Sada, Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, September 5, 2017, http://carnegieendowment.org/sada/72998.

- Aron Lund, “How Assad’s Enemies Gave Up on the Syrian Opposition,” The Century Foundation, October 17, 2017, https://tcf.org/content/report/assads-enemies-gave-syrian-opposition/.

- Jihad Yazigi, “No going back: Why decentralisation is the future for Syria,” European Council on Foreign Relations, September 6, 2016, http://www.ecfr.eu/publications/summary/no_going_back_why_decentralisation_is_the_future_for_syria7107.

- Kamal Dib, Warlords and Merchants: The Lebanese Business and Political Establishment, (UK: Ithaca Press, 2004); Rola Al Husseini, Pax Syriana: Elite Politics in Postwar Lebanon, (New York: Syracuse Univeristy Press, 2012); Ramez Dagher, “When Warlords Become Presidential Candidates,” Moulahazat blog post, April 26, 2014, https://moulahazat.com/2014/04/26/when-warlords-become-presidential-candidates/.