International peacekeepers in southern Lebanon measure their achievements by conflicts averted. Their biggest achievement in the past decade is what they call the “war over a tree,” which almost happened on August 3, 2010. On that date, Israeli troops began cutting down trees along the Blue Line, the disputed boundary between Lebanon and Israel.1 Israel wanted better visibility of the border region where Hezbollah, its most formidable military adversary, operates. On the other side of the Blue Line, however, it was the Lebanese Armed Forces—the official state army—that held formal sway, not Hezbollah. The Lebanese military was already fending off accusations that its power in southern Lebanon was only symbolic, and that Hezbollah really had control. Lebanon insisted that the trees in question grew on the Lebanese side of the Blue Line. When the Israelis proceeded to cut the trees down, Lebanese soldiers opened fire. One Israeli was killed and another was wounded. Israel immediately returned fire, killing two Lebanese personnel and one journalist.2 The conflict threatened to spiral into outright war, at a time when both sides openly averred that they wanted to avoid another conflict. The calculus for both sides had changed since 2006, when Israel and Hezbollah had prepared for war and expected to reap strategic and political benefits. Now, both sides feared that a war would carry huge costs and provide no windfall, yet were on the verge anyway because of a landscaping disagreement.

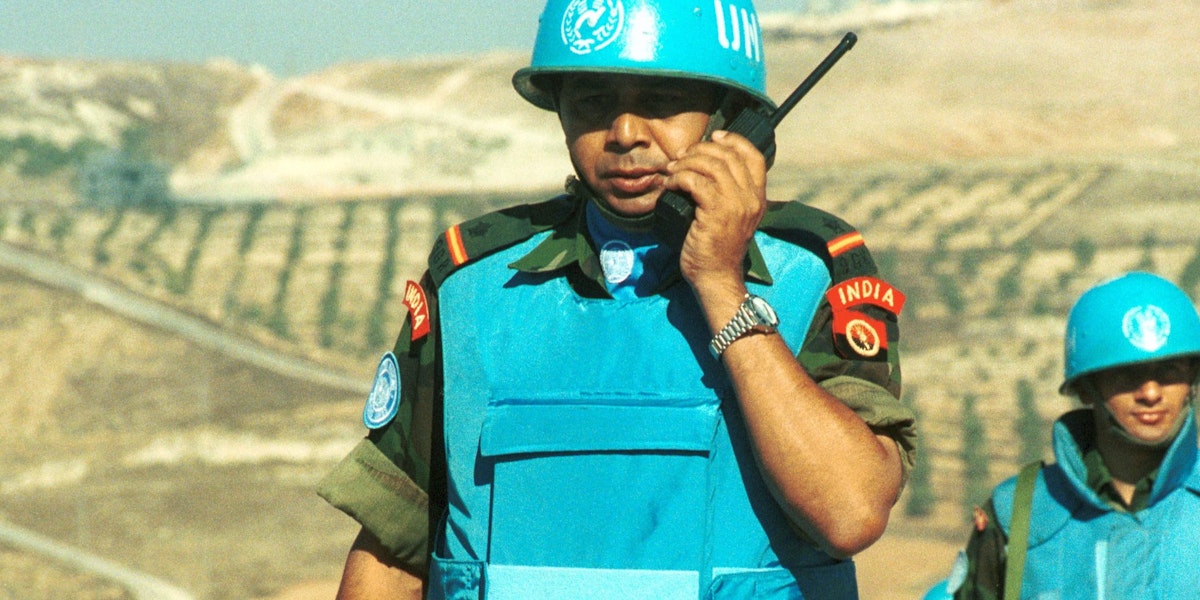

“Sensitivities are high. A war can start over the branch of a tree,” said a United Nations (UN) official who was privy to the negotiations that followed. “No one wanted to escalate the situation. But anything can happen because of a mistake.”3 As fighters on both sides readied for war, peacekeepers from the UN Interim Force in Lebanon (UNIFIL) quickly deployed to the disputed area between Adeisseh, Lebanon, and Misgav Am, Israel. The acting force commander joined them, flying in by helicopter from the mission’s coastal headquarters.4 The presence of neutral international troops was enough to delay any escalation while multiple parties, including the UN, the United States, and some Lebanese officials, called for both sides to defer any action until they could meet.

Israel and Lebanon have a long history of tension: officially, they have been at war without interruption since 1948, and they have not agreed on an officially demarcated border—nor, after several wars, have they formally agreed to a cease-fire. Nevertheless, a strange forum for conflict management has grown up between them. Since 2006, when UNIFIL was reauthorized by UN Security Council Resolution (UNSCR) 1701, peacekeepers have presided over more than one hundred tripartite meetings, which bring together officers from Israel, Lebanon, and UNIFIL to manage disputes and technical issues along the Blue Line.5 The primary belligerents along the border are Hezbollah and the Israeli military, but the Lebanese military serves as Hezbollah’s interlocutors in what has become known as the Tripartite Process.

During the crisis of August 3, 2010, Lebanese and Israeli forces avoided further clashes for twenty-eight hours, and then met near the UNIFIL headquarters, where both sides accepted a UN ruling that the trees were located on the Israeli side of the Blue Line.6 A now-retired Lebanese general named Abdul Rahman Chehaitli, who took part in the negotiations, said that the Lebanese Army presented compelling evidence that it was regular Lebanese troops that had fired during the incident, not Hezbollah irregulars. “They understood that they had put us in a position where we had no other choice—either to shoot, or to retreat, and look weaker than Hezbollah,” the retired general said. “The Lebanese Army would have looked like a funny army in the eyes of the people of the South, that Hezbollah is better. We had to show that we are willing to defend our land.”7 Other negotiators said that there was no clear evidence about whether Lebanese soldiers or Hezbollah fired the shot that killed the Israeli officer, but that in any case the Israeli side was willing to hold the official Lebanese Army responsible in order to diffuse the crisis.8

The Adeisseh tree crisis is just one of the more unsettling of many similar incidents that have destabilized the frontier between Lebanon and Israel since the 2006 war. It underscores the key role of UNIFIL, as well as its limits. In a region rife with standing conflicts between belligerents who have little or no direct channels of communication, UNIFIL provides a rare example of conflict management in an extremely unstable and opaque environment. Its track record offers some suggestions of promising approaches to manage and mitigate conflict, while avoiding unwanted escalation. But it also offers stark warnings of the limitations of a narrow and indirect approach in the absence of enduring cease-fires, treaties, or other more robust conflict-resolution mechanisms. The long-running tripartite talks between the Israeli and Lebanese militaries have produced an effective relationship of trust, but that relationship has mainly served to avoid unwanted escalations. Moreover, despite considerable investment from both militaries, it has failed to translate tactical understandings and relationships into political resolutions. In every case where UNIFIL has mediated significant proposed agreements from the two militaries, political actors have refused to adopt their ideas.

UNIFIL officials characterize the military-military talks, and activities like mapping the Blue Line, as confidence-building measures (CBMs), a term that came into use in international security circles during discussions of disarmament during the Cold War. There is no agreed definition of CBMs, and the term is sometimes used imprecisely or interchangeably with “conflict mitigation and prevention.” Most policy frameworks define CBMs in language similar to that used by the UN Office for Disarmament Affairs: “planned procedures to prevent hostilities, to avert escalation, to reduce military tension, and to build mutual trust between countries.”9 The security term “conflict resolution,” which also lacks a formal definition, implies a process that has the potential to decisively end a conflict. Finally, “conflict management” and “conflict mitigation” refer to processes that can affect some elements of a conflict and limit or repair harms caused.10 UNIFIL’s experience suggests that CBMs, and even successful conflict management and crisis diffusion, do not necessarily lead to deeper political dialogue. Tactical trust-building can go only so far without broader political buy-in.

UNIFIL makes a precarious model for conflict management. Despite its successes, both Israel and Hezbollah routinely attack UNIFIL’s legitimacy in public. The population of southern Lebanon expresses widespread skepticism about the peacekeeping mission’s intentions and loyalties, despite the benefits they reap from UNIFIL, which not only reduces conflict but serves as the area’s largest employer.11 Many residents of southern Lebanon and supporters of Hezbollah believe that UNIFIL serves Israeli and American interests and is unlikely to act to protect civilians during future conflicts. For example, during the Adeisseh incident of 2010, locals briefly blocked UNIFIL troop movements, chanting “Are you here to protect us or are you here to run away?”12

The current UNIFIL mission was created in a unique set of political circumstances that prevailed at the close of hostilities between Israel and Hezbollah in August 2006. The design of the mission and its mediating role were not the product of a conscious conflict-management design, but rather stemmed from the vagaries of the compromises and thwarted expectations of all sides. And even though UNIFIL, as crafted, represented a setback for Hezbollah, Israel, and their backers, it has been a versatile and effective instrument of conflict management, within its narrow limits. Its initial design won buy-in, however reluctant, from the belligerents, and its newly muscular force with strong international political backing created perhaps the only sustained, regular, and efficacious channel of communications between Middle East belligerents in an active conflict.

This report avoids the robust debate within the UN and in policy circles about peacekeeping and peace-building. Many policy reviews and independent scholars are examining the entire concept of peacekeeping and exploring the politics and mechanics of mandates and missions. Although UNIFIL is a central case in the peacekeeping debate, this report is concerned with a narrower question about communication channels and CBMs between standing belligerents. Through a narrative and qualitative study of UNIFIL’s tripartite mechanism, it clarifies the workings of UNIFIL’s channel for “deconfliction”—helping militaries operating in the same area to avoid unintentional overlap or clashes—and assesses its political dividends. Finally, it asks under what conditions this type of communication channel might be replicated elsewhere in a region notably deficient in security architecture.

Order from Ashes

This report is part of “Order from Ashes: New Foundations for Security in the Middle East,” a multiyear TCF project supported by the Carnegie Corporation of New York.

Born of a Messy Negotiation

The original UNIFIL mission deployed in 1978 with three missions: to confirm Israel’s withdrawal from southern Lebanon, to restore “international peace and security,” and to restore the authority of the government of Lebanon in the border region. None of these missions were achieved. Israel never fully withdrew, and in 1982 extended its occupation deeper into Lebanese territory. On the Lebanese side, state authority no longer existed, as the nation was riven by the 1975–90 civil war. A quisling militia eventually known as the South Lebanon Army served as an Israeli proxy.13 Hezbollah formed in 1982 in response to the Israeli occupation, and over the following decade grew into the dominant local force fighting Israel. Lebanon’s national army was reconstituted after the Taif Agreement of 1989 paved the way for an end to the country’s civil war. Even as other militias disbanded or had their fighters absorbed into the regular military, Hezbollah alone maintained an autonomous militia. Israel still occupied about one-tenth of Lebanon’s territory, along the southern border, and Hezbollah continued to lead the armed resistance. In 2000, Israel finally withdrew from most of Lebanese territory, but continued to occupy high ground on the mountain of Jabal al-Sheikh, known as Shebaa Farms, as well as the village of Ghajar, which contains critical water sources.14 Later, it also claimed some Lebanese territorial waters in an area where underwater oil and gas exploration is underway.15 Citing Israel’s continuing occupation, as well as the Israeli air force’s daily overflights of Lebanon, Hezbollah spurned calls from some of its Lebanese rivals to disarm or integrate into the national army.16 Tensions regularly flared along the border, and finally boiled over into war in July 2006.

Israel underestimated Hezbollah’s military capacity and political resilience, and as a result it expected that the war would end quickly in a rout that would severely limit Hezbollah’s future. Instead, the conflict quickly evolved into a tough slog. Hezbollah was able to successfully resist and slow down all of Israel’s ground advances into Lebanon. Israel bombed civilian as well as military targets all over Lebanon, far beyond Hezbollah areas. The often-indiscriminate air campaign ravaged Lebanon’s infrastructure and displaced much of the population, but failed to diminish Hezbollah, which was able to fire as many short-range Katyusha rockets into Israel on the final, thirty-fourth day of the conflict as it was on the first.17 Israeli politicians soon realized that they would be unable to achieve their initial war aims of dealing a devastating blow to Hezbollah—a goal that had the full, open support of the United States, as well as quieter endorsement from Arab states, including Saudi Arabia. Meanwhile, Hezbollah began calculating the political cost of appearing to have drawn Lebanon into a war that affected the entire country.

The unexpected aspects of the war shaped negotiations for a cessation of hostilities. Initially, Hezbollah preferred a UN resolution that would leave it sovereign in southern Lebanon. But Lebanon’s government, and significant quarters of Lebanese public opinion, wanted to reassert state sovereignty in the zone of southern Lebanon that hitherto had been solely under Hezbollah’s control. Israel and the United States, by contrast, entered the cease-fire negotiations with unrealistic hopes that they could achieve through peacekeeping what they had failed to do through violence: disarm Hezbollah. The UN had its own new requirements as a result of the lessons learned during the war. UNIFIL troops had stayed out of the way of advancing Israeli troops and, more devastatingly, had been unable to provide meaningful protection for civilians. UNIFIL’s efforts to coordinate refugee convoys out of the war zone, for instance, foundered in part because Israel did not express interest in allowing civilians to evacuate, but also because UNIFIL lacked reliable direct channels to the Israeli military.

France and the United States took the lead in brokering UNSCR 1701, which led to a cessation of hostilities on August 14, 2006.18 The resolution itself authorized a much more robust international force, including NATO troops, to patrol southern Lebanon. Importantly, it also called for the Lebanese Army to deploy in the border region for the first time since 1978. It did not, however, task UNIFIL with disarming Hezbollah. The mismatched means and expectations of the peacekeeping mission left all the belligerents dissatisfied.19 Israel and the United States wanted a peacekeeping force with Chapter VII authority that would actively search for, pursue, and disarm Hezbollah fighters. Instead, UNSCR 1701 gave UNIFIL a more limited charge under Chapter VI of the UN charter: to help the Lebanese government make sure that there would be no weapons other than those of the Lebanese military in the southern part of the country. (Chapter VII of the UN charter empowers peacekeepers to use force much more aggressively in pursuit of its mandate, often referred to as “peace enforcement,” whereas Chapter VI reserves force for self-defense, and is referred to as “peacekeeping.”) Hezbollah was able to thwart more aggressive terms, but the final cease-fire was also much more restrictive than it wanted.20 By design, the new UNIFIL—sometimes referred to as UNIFIL II, to distinguish it from the weaker, less-resourced UNIFIL that preceded it—was not supposed to communicate directly with Hezbollah.

Immediately upon implementing the cease-fire, UNIFIL peacekeepers initiated a process that was not specified in the new mandate but which has become, in the eleven years since the cessation of hostilities until the time of this writing, the most successful element of the mission: the standing, direct negotiations between the Israeli and Lebanese militaries, under UN auspices.21 UNIFIL officials invited both sides to meet to coordinate the Israeli withdrawal; international officials were concerned with avoiding any interactions or tensions between the withdrawing Israeli forces and the Lebanese personnel who would take their place. That first, quick coordination meeting was followed by others, including a more formal meeting toward the end of August 2006. Hezbollah was not part of the discussions, which are now called the Tripartite Process.

The tripartite meeting takes place every month or two in a room at a facility on the Blue Line near Naqoura. According to several participants in the meetings, the room is arranged in a square. The UNIFIL force commander sits on one side with UNIFIL’s political affairs officers facing him. Delegations from the Israeli and Lebanese militaries sit at tables on the other two sides, facing each other, along with UN commanders and staff along the other two sides. All participants speak in English. The Israelis usually address their comments directly to the Lebanese, while the Lebanese address their comments to the UN force commander, perhaps to create a pretext that these are indirect or proximity talks. There are no handshakes between the two sides and no mingling during lunch. The Israeli military, Lebanon, and Hezbollah remain in a state of heightened alert along the Blue Line, and numerous incidents have threatened to escalate into another war since 2006.22 Yet this somewhat informal mechanism has now met more than one hundred times without a single walkout from either side. It appears to be the only place where Israeli and Lebanese officials formally and directly interact.

No one has expressed an interest in finding a way to bring Hezbollah directly into the process. “There is no room in that room for a nonstate actor,” said UNIFIL chief political officer John Molloy.23 Chehaitli, the Lebanese general who led his side’s delegation to the Tripartite Process until 2014, said that he consulted Hezbollah and all the other Lebanese factions and political leaders by telephone before and after every meeting. The ability of the Lebanese side to negotiate depends on the confidence of its delegation and its connection to the Lebanese political establishment, including Hezbollah. If Hezbollah’s relations with the army are under any strain, as they were in 2017, this limits the authority of the army officials at the tripartite meeting.

In the context of the Middle East, this forum is especially remarkable. Most of the region’s running conflicts lack even tactical communication between adversaries. Relatively straightforward arrangements such as temporary cease-fires, prisoner exchanges, or safe passage for civilians have been tortuous and at times virtually impossible in regional conflicts. Belligerents often refuse to recognize each other even on a most basic level. If Israel and Lebanon (and, by extension, Hezbollah) have managed to build a rudimentary channel despite their history and the political obstacles to communication, then perhaps—using a similar approach—other belligerents in the region might also inaugurate conflict-management channels or CBMs.

Design Flaws

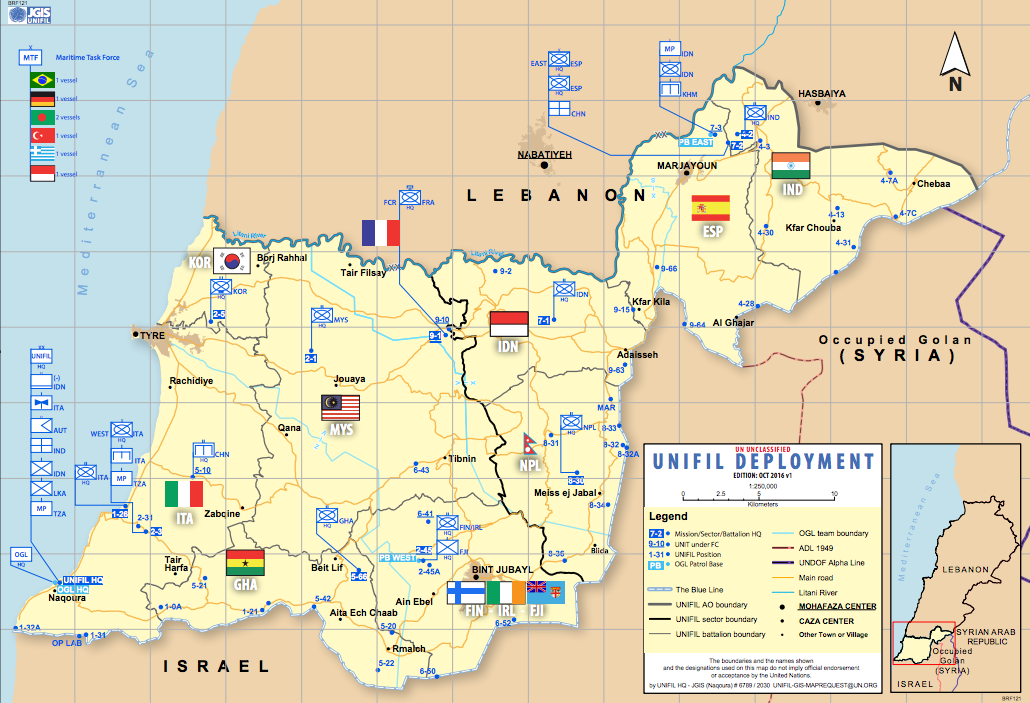

In practice, UNIFIL’s considerable operations undergird two pivotal enterprises: the Tripartite Process and the marking of the Blue Line. Conceptually, the Tripartite Process is a conflict-management (and not conflict-resolution) forum, intended to air and resolve problems at the tactical level—soldiers talking to soldiers about military problems. Along with the marking of the Blue Line, it is also a CBM, intended not only to avoid accidental violations but also to build trust between the two sides. Of course, UNIFIL’s peacekeeping operation has many other aspects. Its approximately 10,500 troops generate economic activity for southern Lebanon; after the Lebanese government, UNIFIL is the largest employer in the area.24 UNIFIL’s maritime task force hails shipping traffic and refers thousands of vessels to the Lebanese military for further search, although so far the effort has not interdicted any arms shipments to Lebanon.25 UNIFIL sends patrols around the Lebanese border region day and night. It has developed a deep network of relationships with the Lebanese military and with local officials throughout southern Lebanon, many of whom are also members of Hezbollah and other political movements.

Circumstances have changed over the decade-plus since UNIFIL’s inception. Most notably, the war in Syria has upended regional power dynamics and balances, and the United States has taken a noticeably more distant approach from regional conflicts. Still, UNIFIL’s mandate and practice reflect the political balance at the close of the 2006 war. Hezbollah, for instance, has expanded dramatically since 2006, when it was still consolidating its local position in Lebanon after its ally and patron, Syria, was forced to relinquish direct control of Lebanon. Today, Hezbollah is a regional military power, operating in tandem with Iran as infantry or trainers in Iraq, Yemen, and possibly elsewhere. In Syria, Hezbollah has played perhaps the most critical military role on the government’s side. Inside Lebanon, Hezbollah has moved from being a strong faction to being the strongest, today holding the balance of power domestically, with the ability to dominate the complex political negotiations that determine who holds the presidency. In 2013, the European Union as a whole joined Israel, the United States, and some individual European governments in listing Hezbollah’s “armed wing” as a terrorist group. (Hezbollah itself denies it has any separate armed wing, making such a designation tantamount to naming the entire organization.)26 Israel has initiated several wars against Hamas in Gaza, and has intervened periodically in Syria, usually to bomb targets that it considers related to Hezbollah’s military capacity.27 As the war in Syria enters what appears to be a final phase, Israel has increased its public discussion of concerns about the threat posed by Hezbollah, which is better armed and trained than ever because of its role in Syria. Israeli media have reported apparent leaks from Israeli security officials claiming that Hezbollah has acquired new long-range missiles installed in Syria as well as in Lebanon, opening up new potential fronts for Hezbollah-Israel conflict.

UNIFIL’s architecture lent itself to any improvisations that won the support of both Israel and Hezbollah. Yet its efforts to manage conflict, implement CBMs, and translate tactical entente into political resolution have had to contend with its fundamental design flaws. Politically, both Israel and Hezbollah publicly undermined UNIFIL from the start. Hezbollah rhetoric portrayed UNIFIL as a tool of Israel, the United States, and NATO, deployed to spy on “the resistance”—the preferred term for Hezbollah among its sympathizers—or disarm it. Israel has relentlessly criticized UNIFIL as ineffective at best and a tool of Hezbollah at worst, granting the armed group cover as it upgraded its military infrastructure for a future war with Israel. At the same time, according to UNIFIL officials, both groups regularly cooperate with UNIFIL (with Hezbollah operating through the Lebanese Army) and rely on it as an honest broker even as they continue political campaigns against it. A second limitation stems from the lack of strong connections to the primary belligerents. UNIFIL’s best direct relationship is with the Lebanese Army. It cannot officially communicate with Hezbollah, and its channels to the Israeli military, while stronger than before 2006, are still limited.

These design flaws mean that UNIFIL’s means and mandate are misaligned. The language of UNSCR 1701 also allowed key parties to misinterpret, perhaps willfully, UNIFIL’s purpose and actions. Hezbollah could claim, with some justification, that UNIFIL dispatched Israeli allies onto Lebanese territory to protect Israeli interests. Israel, also with some justification, could claim that UNIFIL was supposed to keep the border region free of any fighters other than Lebanese Army regulars—and that UNIFIL has not made headway toward that goal, even symbolically. Israel violated the terms of the resolution on a daily basis with overflights, and with the standing violation of the occupation of Ghajar and Shebaa.28 Hezbollah, to the extent that it has maintained any weapons or fighters in the border zone, also engaged in a standing violation of the agreement on the cessation of hostilities. UNIFIL’s role was further complicated by the fact that only one of the belligerents (Israel) was a signatory to the cessation of hostilities and was represented in the Tripartite Process. Hezbollah was present only indirectly, through the Lebanese military, which maintains the difficult balancing act of claiming to speak to (and sometimes for) Hezbollah while also maintaining that the latter is an entirely independent organization.

On one hand, Hezbollah and Israel have both benefited from UNIFIL’s core functions: development projects for poor denizens of the border region; demarcation of the Blue Line; deconfliction, de-escalation, conflict management, and communication between belligerents; intelligence gathering; and a unique forum in which armies from two nations at war routinely meet for direct talks and resolve technical issues even as the political conflict between their governments continues unabated. On the other hand, both belligerents routinely have undermined UNIFIL, attacking its legitimacy and performance in public forums while praising it in private; engaging in prohibited military operations; and refusing to extend any political support to the negotiations that they joined at a military level.

Israeli officials regularly grouse about these arrangements, and in 2017 they apparently orchestrated a public relations campaign that portrays a rising threat from Hezbollah unchecked by UNIFIL.29 When Nikki Haley, the U.S. ambassador to the United Nations, visited Israel in June 2017, she toured the border and heard Israeli complaints that UNIFIL was failing in its responsibility to keep southern Lebanon free of militants, including Hezbollah. According to Israeli media reports, an Israeli general confronted the UNIFIL commander for failing to actively disarm Hezbollah, and asked Haley to help strengthen UNIFIL’s mandate.30 A stronger argument was made by Israeli officials who leaked a claim to a journalist that UNIFIL was a detriment to Israeli security.31 As noted earlier, some supporters of Hezbollah in Lebanon have taken a similar position, attacking UNIFIL as a tool used to spy on Hezbollah, limit Hezbollah’s ability to defend Lebanon, or serve as a forward deployment of pro-Israel NATO troops. “The new UNIFIL is a defensive force for Israel. It’s an offensive force against Hezbollah. Lebanese security is better without UNIFIL,” said retired Lebanese Army general and military analyst Amin Hoteit, who described the Tripartite Process as an “illegal” contact with the enemy.32 These complaints from Israeli and Lebanese factions create a small but steady challenge to UNIFIL’s legitimacy.

UNIFIL officials point out that no critics from either side have provided evidence to buttress their accusations, which seem intended to rile up domestic political constituencies even while both sides privately exhibit substantial trust in UNIFIL’s goodwill. Israel, for instance, has never published evidence to support its claim that Hezbollah is rearming inside UNIFIL’s area of operations. Numerous officials and diplomats interviewed by the author said that they believe that Hezbollah has in fact avoided violating the terms of UNSCR 1701, with ample ability to place important military capabilities in areas outside of UNIFIL’s area of operations. The continuing preparations for war on both sides, as well as the anti-UNIFIL rhetoric, illustrate other limits on its impact as a conflict-management mechanism. Much of the posturing and rhetoric seems intended for domestic political consumption. Hezbollah wants to appear undeterred, powerful, and autonomous, despite UNIFIL’s presence in southern Lebanon. Israel wants to portray itself as ready to confront Hezbollah if needed and prevent any incursions or missile strikes from Lebanese territory. At the same time, both sides clearly benefit from the overall calm that has prevailed since 2006, and would both lose more than they could gain from a direct conflict. The theatrical nature of the Israeli complaints about Hezbollah’s activities is underscored by the lack of direct evidence offered either in public or in private about Hezbollah’s weapons activities in the actual UNIFIL zone of operations. Likely explanations for the observed facts are that Israel is genuinely worried about Hezbollah’s growing strength, that Hezbollah has acquired new military capacities, and that Hezbollah has been careful to minimize violations of UNSCR 1701 by placing its military facilities outside the UNIFIL area of operations.

Imperfect Practice

What UNIFIL has done well is monitor violations, demarcate the Blue Line, negotiate tactical disputes, and build a forum where the belligerents can air tactical grievances. There has not been a war between Israel and Hezbollah since 2006—not because of any action by UNIFIL, but because for the time being both parties have calculated that open hostilities do not serve their interests. The Tripartite Process has diffused two tense episodes: the Adeisseh clash of 2010, described above, and a series of clashes between Israel and Hezbollah in the Golan Heights and Shebaa Farms areas in 2015.33 Participants in the Tripartite Process have occasionally delved, without significant success, into more complex issues that ultimately require a political settlement: a permanent cease-fire, the outstanding territorial issues, and the demarcation of territorial waters.

A quick look at some of the specific efforts helps illustrate what has worked in UNIFIL’s approach and what has not. “It’s a conflict-management institution, not a conflict-resolution institution,” observed Timur Goksel, a UNIFIL veteran who worked with the mission over the course of two decades and has been based in both Israel and Lebanon. “It offers adversaries a way out. They can use UNIFIL as an excuse. It opens a way out of major conflict. This is what UNIFIL is all about.”34

Most straightforward is the marking of the Blue Line, which follows the line of withdrawal of occupying Israeli forces from 2000 and does not signify an international position on the final disposition of the legal border between Israel and Lebanon. UNIFIL manages a painstaking process that requires both sides to confirm the GPS location of a point on the Blue Line, to within less than a meter. If agreed, the UN places a blue barrel on that point, and begins negotiations over the next barrel point, which must be visible from the adjacent barrel. As of summer 2017, the UN had erected barrels at 268 Blue Line waypoints, just over half the number necessary to demarcate the entire boundary.35 On one hand, UNIFIL considers this project a success because it reduces unintentional boundary violations by shepherds, farmers, and the like, and because it creates a CBM through which Israel and Lebanon can interact. On the other hand, the slow pace of the enterprise hints at the intractability of relations, even on tactical matters. The line of withdrawal is only 120 kilometers (75 miles) long, and yet a decade has not sufficed to mark it.

The disputed village of Ghajar, which has long been a flashpoint between the two sides, exemplifies the limits of the existing channels of communication and negotiation. The Blue Line passes directly through the village. Its inhabitants are Alawites who previously lived under Syrian rule on territory that today is claimed by Lebanon.36 Israel currently controls the entire village. Israeli presence in the northern half of Ghajar entails a permanent violation of the Blue Line. The situation is further complicated by the lack of pressure from the village’s residents, who appear content to operate as part of Israel. Israel has committed in principle to withdrawing from the northern portion of the village, but the details of how to do that have eluded all parties.37

In 2012, military officers from both sides, with Italian UNIFIL officers present, negotiated a proposal to resolve the issue of Ghajar, and according to participants in the talks they formulated a twenty-seven-point plan.38 In 2012, that plan was passed to political leadership in Israel and Lebanon. The Lebanese politicians accepted the plan in principle, while the Israelis simply never responded to their own military’s proposal—effectively killing it by tabling it. Israel is reluctant to relinquish territory from which it has agreed in principle to withdraw because of Hezbollah’s power. Hezbollah appears unlikely to lose its status as a powerful, armed nonstate actor with a dominant place in the Lebanese political order anytime soon, making it unlikely that Israel will accept a change in the status quo with Lebanon, no matter how many proposals come out of UNIFIL meetings.

The frustrated negotiations over Ghajar starkly illuminate the limits of UNIFIL’s open communications channel between Lebanon and Israel. “We have to recognize our limitations and strengths,” said a UNIFIL official involved in the negotiations. “Our mandate is purely operational and tactical”—and not political. In the Ghajar case, this UNIFIL official said, the Tripartite Process succeeded beyond his expectations, but the preliminary technical agreement reached by the two militaries never achieved buy-in from the Israeli government. UNIFIL therefore is criticized for the political tensions between Israel and Lebanon, even though this official believed the political leadership had failed to build on the foundations that UNIFIL had laid for them.39 The Lebanese general who led his side’s delegation in the Ghajar negotiations was more blunt: “We don’t have strategic politicians in this region. They are waiting for the next war and doing nothing to prevent it.”40

On an issue over which the two sides agree on the fundamental disposition—that the northern portion of the village lies on the Lebanese side of the Blue Line and the southern portion on the Israeli side—a technical resolution reached by the two militaries does not translate into a political process to refine and implement the resolution. The most optimistic reading of this episode is that the belligerents established the baseline for a likely future settlement when and if the macro-political climate shifts. But in practical terms, if the Tripartite Process cannot shape the political agenda on a comparatively straightforward issue like Ghajar, then it has almost no chance of resolving contentious disputes over the high ground of Shebaa Farms (currently occupied by Israel) or the gas-rich territorial waters in the Mediterranean (claimed by both countries).

But even in the aims that are more central to its purpose—such as information sharing for tactical and operational purposes, and in the service of conflict management—UNIFIL has had only imperfect success. In the event of another war, the UNIFIL channel will be better positioned than it was in 2006 to communicate between belligerents, which could enable UNIFIL to coordinate civilian evacuations and protect civilians who are trying to stay out of the conflict. Its ability to do so, however, will be severely limited by its lack of a direct channel to Hezbollah; it will continue to rely on the Lebanese military to pass messages to Hezbollah fighters. Even though Israel has not allowed UNIFIL to establish a mission in Tel Aviv, a UNIFIL liaison team has been stationed in Israel, and its presence should facilitate the passing of information. In 2006, according to UNIFIL officials, it was often difficult to even reach Israeli military officials, for instance to inform them of civilian convoys seeking to evacuate the war zone. “In 2006, when we called the Israelis, there was no one on the other end of the line,” said one UNIFIL official. During the 2006 conflict, none of the belligerents would officially grant safe passage to any party—whether UNIFIL, humanitarian aid groups, or even fleeing civilians—even when they did accept information about their operations. It is easy to imagine this difficulty being repeated in a future conflict. UNIFIL still has no direct liaison capability with Hezbollah, and its relationship with the Israeli military is limited and politically strained. None of the parties has established any understanding about protection of civilians in the event of a future war, preferring instead to make fire-and-brimstone predictions about how much they will make the other side suffer in a repeat engagement—which both sides paint in terms of total, catastrophic war.

Domestic tensions shape the conflict-management channel as well. Israeli military officials stationed on the northern border avoid the kind of public alarmism that is often heard from the military and political leadership in Tel Aviv and Jerusalem. In Lebanon, Hezbollah tries to paint Israel as the habitual violator and to tout its “partnership” with the Lebanese military, but in practice it often undermines both claims. In April 2017, apparently in response to Israel’s public statements about the risks of another war with Hezbollah, Hezbollah organized a “media tour” of the border region.41 It escorted more than a hundred journalists into the UNIFIL zone, clearing them through Lebanese Army checkpoints without even a perfunctory identification check. (Usually, advance permission from Lebanese military intelligence is required for foreigners to enter the UNIFIL area of operations near the border, and all visitors must show identification.) Escorts from Hezbollah led the visitors past an orchard where uniformed Hezbollah fighters in battle gear and paint posed for photographers, brandishing weapons including machine guns and rocket launchers. The display of fighters was choreographed and theatrical, demonstrating Hezbollah’s strategic message rather than any real tactical capacity. But the display also represented a very real violation of UNSCR 1701, less than two miles from UNIFIL’s headquarters in Naqoura. Although UNIFIL has put its credibility on the line, insisting that Hezbollah does not bear arms in the border region, Hezbollah had no compunction about undermining UNIFIL, the Lebanese Army, and the Lebanese government in a single information operation. The following day, Lebanon’s prime minister and army chief visited the border region to insist that they, and not Hezbollah, had sovereignty in the southern part of the country.42 The visit caused tensions to flare between UNIFIL and Israel, as well as between Hezbollah and the Lebanese Army and government.43

Domestic critics believe that Hezbollah was trying to remind its Lebanese constituents and critics alike of the threat posed by Israel and that the central, if not sole, responsibility for Lebanese territorial defense lies in Hezbollah’s hands. Intentionally or not, the tour called attention to the ground truth that Hezbollah operates in southern Lebanon with full independence. It might defer to the Lebanese Army or UNIFIL in order to avoid embarrassment or minor mishaps, but it can freely circumvent even the most symbolic of checks.

Hezbollah’s message about conflict management during the tour was clear. Representatives of the party told journalists that they were closely monitoring Israeli maneuvers on the Blue Line and were preparing countermeasures of their own. Hezbollah does not want to initiate a war with Israel at this time, they said, but they were prepared at any moment to respond if Israel were to initiate hostilities. Corollary to this direct message was an equally important indirect implication, one which is understood by all the regional actors: Hezbollah continues to hold sovereign power of arms and operates without limitation from the government of Lebanon, UNIFIL, or any other force. “We are here to declare that we are ready at any time,” a Hezbollah official told reporters on the tour. “Recently there was an escalation in the media by Israel, so we are here to say, you are taking these measures, and we are ready.”44

A More Complex Environment

Hezbollah has greatly increased its military capacity since joining the Syrian war as a pivotal combatant in 2012. The Lebanese nonstate actor has emerged as the premier urban combat and infantry force on the side of the Syrian government. It has engaged in wide-scale maneuver warfare, and has engaged in integrated warfare, involving air force support, with professional forces from Iran, Russia, and Syria. Hezbollah has helped form new militias and has led coordinated assaults with militia support involving groups and fighters from Afghanistan, Iraq, Iran, Lebanon, Syria, and elsewhere.45 Reports suggest that Hezbollah has also acquired a new arsenal of long-range missiles and land-to-sea missiles, which greatly increases its deterrent capacity against Israel and could enable it to threaten more Israeli targets than it could in 2006.46 Some diplomats and analysts speculate in private discussions that Hezbollah has relocated much of its military infrastructure onto Syrian territory, perhaps in the Qalamoun Mountains or the Golan Heights. Several speculate that Hezbollah hopes that future clashes with Israel might be limited to the Golan, rather than taking place on Lebanese territory.47 In any case, the Syrian war has greatly complicated the effort to manage conflict between Hezbollah and Israel. With the Syrian war potentially entering a closing phase, from which Hezbollah and the Syrian government will emerge victorious, several analysts have refocused their attention on the latent Israel-Hezbollah conflict.

A clash in January 2015 suggests the complexity of future escalations. Throughout the war in Syria, Israel has occasionally bombed targets inside Syria that it claims are connected to Hezbollah’s military capacity. It struck a convoy in the Golan Heights on January 18, 2015, killing seven people. The dead included an Iranian general, and an iconic young Hezbollah fighter, Jihad Mughniyeh, the son of Hezbollah’s deceased senior military commander.48 Missiles were reportedly fired in retaliation into Israel from the Syrian-held Golan. Ten days later, on January 28, Hezbollah claimed responsibility for an attack from the Lebanese side of the Blue Line on an Israeli convoy in the Shebaa Farms area. Two Israelis were killed and five wounded. In the brief escalation that followed, a Spanish UN peacekeeper was killed. Both sides refrained from further escalation, and aired their complaints through the Tripartite Process. In this complex-if-contained conflagration, it was the two sides’ preexisting reluctance to engage in outright war that limited escalation, and not the good offices of the UNIFIL conflict-management channel. UNIFIL’s role was to limit the prospects for misperception and accidental escalation and provide a mechanism for both sides to climb down from conflict. Both Hezbollah and Israeli officials made public statements around the time of the incident to the effect that they did not want war, but were ready for it.49

In an increasingly complex threat environment, UNIFIL’s structure greatly limits its usefulness as a channel. Israel and Lebanon are formally still at war, and no closer to a permanent cease-fire than they were when UNSCR 1701 came into force on August 14, 2006. Whereas the Israeli government and military are unitary actors on one side of the Blue Line, the other side has a bedeviling array of potential belligerents with competing interests. These possible participants include but are not limited to Hezbollah, the Lebanese government, Palestinian factions, the Syrian government, and possibly some Syrian rebel factions, although most Syrian rebels in the Golan have either cooperated with Israel or remained neutral. UNIFIL can call the Lebanese Army to settle a crisis, but then must rely on the Lebanese Army, itself strained by pressures stemming from the war in Syria, to make effective contact with other players.

Nevertheless, Chehaitli and others who see the utility in the channel provided by the Tripartite Process believe that this unique forum for active belligerents offers unprecedented opportunity to negotiate. “Even though we are enemies and not good neighbors, and everywhere are fighting each other, there is something important: when we say something, we mean it and we don’t lie,” Chehaitli said. “They trust our word. When we say no, we mean no. When we say yes, we mean yes. They speak frankly. We don’t lie, and they don’t lie.”50 Even talks at a technical level, he believes, can open up political options.

Useful Forum, Limited Impact

Whether technical talks and a bare-bones conflict-management channel can, in fact, shift the political opportunities is precisely the question raised by UNIFIL’s record since 2006. UNIFIL’s example suggests that military-military talks have utility but are unlikely to drive political resolution. The UNIFIL model may be a promising approach for conflicts between belligerents with strained or nonexistent diplomatic relations, but it is a model for managing conflict and avoiding unintended escalations, not for resolving conflict and reversing escalations that are intentional or are based on mistrust and miscalculation.

This conflict-management paradigm should invite low expectations. As a senior active-duty Lebanese commander put it, “I believe Israel and Hezbollah have no interest in escalating the situation. But any mistake could trigger a war.”51 No amount of technical communication about process and minor disputes can resolve major, tangible political problems. UNIFIL, by mandate, does not actively search for Hezbollah or other factional weapons and therefore is not an active disarming force. It hails ships, but the Lebanese Navy searches them. It relays reports of Hezbollah activity, but the Lebanese Army, a partner to Hezbollah, conducts searches for weapons. To further complicate matters, the Lebanese Army has had to redeploy its forces elsewhere to deal with violence and permeable borders stemming from the war in Syria. UNSCR 1701 was premised on fifteen thousand UNIFIL troops in support of fifteen thousand Lebanese troops. As of September 2017, there were approximately twelve thousand UNIFIL troops and only two thousand Lebanese in the southern Lebanese area of operations. Officials and diplomats have said that Hezbollah can move materiel and personnel in southern Lebanon so long as it is careful to avoid direct contact with UNIFIL’s four hundred daily patrols—although all who spoke with this author were careful to say that even if Hezbollah could do so, they had no evidence that Hezbollah in fact had done so.52

“It’s the only mission that speaks to two countries that are still at war,” noted one UNIFIL official. “This works if parties don’t want to go to war. It can’t prevent a war from happening.”53 There are several situations in which the UNIFIL mechanism can achieve little: when one of the belligerents might decide that it prefers war, despite the human and strategic costs; when one of the belligerents might decide that it needs to appear to be courting war in order to deter its adversary; or when one of the adversaries miscalculates with an offensive or retaliation that it believes falls within the boundaries of limited tit-for-tat but which the other side interprets as a game-changing escalation. All of these scenarios factor into a potential Hezbollah-Israel conflict in 2018, with Hezbollah armed and trained to a greater extent than ever before, Israel openly discussing a destructive war as a way to contain Hezbollah, and both parties telling interlocutors that they would prefer to avoid war but believe that the other side is courting conflict.

The most important limiting factor for UNIFIL, and any conflict-management forum modeled on it, is the lack of any direct connection between a military-military channel and a political negotiation between the governments and nonstate actors involved in a conflict. Unless a government or nonstate actor has openly and expressly deputized a military channel to negotiate a political resolution, there is no evidence that technical talks will prompt a political dialogue—simply because some participants hope for it to do so—much less a resolution. Certainly, evidence suggests that dialogue of any kind is preferable to its absence. Dialogue allows belligerents to learn more about each other and dispel false assumptions, and serves as a forum to deescalate unwanted tensions. In some instances, a purely technical or process-oriented forum can create a constituency for political resolution that in turn lobbies decision-makers to change their policies. Dialogue spaces can also generate unconventional proposed solutions to policy problems that then become available to decision-makers should they be inclined to consider them. Still, a dialogue process or deconfliction forum does not possess any power to compel decision-makers to change their positions or even reframe the problem. UNIFIL’s record as an arbiter or honest broker does not appear to have changed any policy position on the part of Hezbollah or the government of Israel. A technical channel cannot create a new political climate. Major outstanding issues—continuing Israeli infringements of Lebanese sovereignty and Hezbollah’s reach as an armed nonstate actor—remain the likely trigger of future conflicts. The belligerents have mutually exclusive interests that inherently conflict.

The channel connecting the Israeli military to the Lebanese military, and offline, the Lebanese military to Hezbollah, has not brought Hezbollah any closer to political relations or direct discourse with the powers that consider it a terrorist group. All the key political issues dividing Lebanon and Israel (and Hezbollah and Israel) remain. Nor has the UNIFIL channel made any significant steps toward resolving even the tactical issues that engendered it in the first place—first and foremost, the need for a permanent cease-fire. The UNIFIL case suggests that CBMs and communications channels, as important as they can be for managing conflict, should not be expected to resolve it nor to substitute for political engagement.

Even beyond its limitations, UNIFIL’s conflict-management paradigm may, paradoxically, increase risks by leaving political problems unresolved. “There is no doubt the UNIFIL mission has acted as shock absorber for local tensions and maintained a negative peace, that is, it has prevented the escalation of minor incidents into large-scale conflict,” the researcher Vanessa Newby concluded after conducting fifty interviews of UNIFIL officials and others who deal with the mission.54 “But its presence appears to be sustaining the conditions of conflict more than it is resolving them.”

Conclusion: Conflict Management Needs a Political Dimension

This report has not been an exploration of peacekeeping modalities, but rather a case study of a specific channel, designed more for dialogue than negotiation, that has emerged between two combatants over more than a decade. It assessed what has worked in UNIFIL’s mediation between Israel and Hezbollah and what factors contribute to its successes and limitations. More broadly it has raised doubts about whether limited tactical conflict-management measures can translate into building confidence or even deeper strategic or political rapprochements.

UNIFIL’s best work has been both novel and limited: to serve as a conduit between Hezbollah and the Israeli military to manage conflict and prevent unwanted escalation. It also successfully bolstered the Lebanese military’s function and standing as a state institution. The Tripartite Process has been far more successful than Hezbollah, and perhaps the Israeli military, would have liked. At the same time, however, the significance of this channel must not be overstated. Indirect dialogue between standing combatants has been a tool of conflict management, not of conflict resolution. It functions like a red phone, allowing the combatants to communicate and deescalate, avoiding unwanted conflict. When participants in the UNIFIL dialogue have sought to go further—for example, in efforts to resolve outstanding border disputes like the status of Ghajar—nothing has come of the Tripartite Process. UNIFIL, with its weak mandate and limited buy-in, is a discussion forum that matters only when the parties to the conflict share a common interest in avoiding outright hostility, escalation, or full-blown war. It would be foolish to read too much into UNIFIL’s achievements. If either Hezbollah or Israel shifted its cost-benefit calculus and decided it was more preferable to go to war than maintain the status quo (as Israel had in advance of the summer of 2006), then UNIFIL’s mechanisms would provide almost no peacemaking or conflict-avoidance potential.

Still, none of the large caveats about UNIFIL’s success nullifies its basic benefits or those of other forums like it. Such channels are a rarity in the Middle East, and UNIFIL’s record over more than ten tense years on the Israel-Lebanon border is remarkable. The potential of the model is especially attractive for a region that lacks even the most rudimentary conflict-management architecture. When there is an event along the Israeli-Lebanese frontier, both sides have a known institution to turn to for mediation and de-escalation. Many of the Middle East’s conflict areas are plagued with similar problems and thus are ripe for UNIFIL-like channels, managed by neutral third parties that can avoid accidental escalations, act as a clearing house for airing grievances and seeking technical solutions to relatively small technical problems, and potentially manage aspects of open conflict if it emerges. Such channels could pave the way for delivering humanitarian aid in Yemen or exchanging prisoners in Syria. The model is for a standing body that is not ad hoc nor of limited duration, and thus can establish trust over multiple iterations of dialogue and conflict management.

Replicating the setup in other conflict zones will not be simple; in Lebanon, it has been possible as much because of happenstance as because of good planning and design. UNIFIL benefited from an immediate task that motivated both sides: managing the Israeli withdrawal in August 2006 and the subsequent deployment of the Lebanese Army. That exercise built trust between the belligerents and UNIFIL, if not between the belligerents themselves, and was a vital pathway to the next hundred tripartite meetings. Recreating that dynamic in another conflict zone would require a similar exercise; otherwise it would be hard to imagine drawing belligerents into a standing, direct dialogue. “You need buy-in from the parties,” said one long-term participant in the UNIFIL process. Israel and Lebanon participate entirely voluntarily. The tripartite meetings are not mandated by UNSCR 1701. If the UN established similar processes around Syria, or in Yemen, it is unclear whether the belligerents would attend. But if conditions were right and opportunities seized, the potential for reducing violence is clear, at least in the short term.

More deeply, however, the UNIFIL case illustrates the broader problem with applying a military (or security, or conflict-management) paradigm to inherently political problems. Such a forum can be an effective long-term intermediary, but only for tactical matters. The conflict between Israel and Hezbollah is a political one. It might be resolved by military force in the unlikely event that one side vanquishes the other outright, but the costs of conflict and the conventional strength of both belligerents mean that in the long term a political outcome is more likely. At the time of this writing both sides seem to consider the status quo acceptable, despite the risk of destabilizing violence. That calculation is political, not a technical security assessment.

Long-term security requires political stability, which in turn depends on a modicum of governance, justice, and representation for the governed. A sustainable mix need not achieve utopian standards; it can give short shrift to rights, for example, if the quality of services is high. Furthermore, populations in conflict areas and zones of degraded governance have proven able to bear miserable circumstances for long periods. Sustainable security and conflict management, however, must incorporate a political dimension. Security discussions naturally focus on mechanics because that is the level at which results can be achieved and measured: separating hostile populations, demobilizing or retraining militants, containing refugee populations, or demarcating lines of control. But such processes should not be confused with political resolution, which ultimately is the end point of conflict. Political resolutions need not be just or fair, but to hold over time they must be clear and they must be recognized, de facto, by would-be belligerents. Dialogues, peace processes, conflict-management forums, and CBMs can only go so far. If adversaries have no common ground or no balance-of-power disposition to compel a political settlement, then most security arrangements will be limited to managing tensions in a state of limbo or low-ebb conflict. Improvements to governance and political systems in the Middle East would improve the quality of existing dialogue and conflict-management mechanisms, but would not guarantee more fruitful political negotiations.

The field of critical security studies has pushed the field of academic political science to incorporate political concerns into its definition of security, but minimized the hard security concerns that make life dangerous in conflict zones.55 The balance of security and politics is not merely a theoretical concern; it drives the persistence of deadly conflict in the Middle East. Both hard security and political grievance must be addressed, even if unfairly, in order to resolve a conflict. A similar dynamic shapes the need to address process as well as policy. A satisfactory forum is required for belligerents to talk at all. Forums like UNIFIL, or the Madrid Peace Conference (where parties to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict met in 1991), create the space and relationships that are a precondition for any substantial negotiation. Yet process does not suffice if no common policy framework can be reached on the central matters of dispute. No amount of tripartite meetings at the UNIFIL headquarters will compel the political leadership in Israel or Hezbollah to reformulate their core goals.

In some ways, a UNIFIL-style arrangement is cynical—almost an antipolitical response to conflict. But in the absence of obvious better alternatives, arrangements such as UNIFIL are still for the best, as long as no one expects them to bring long-term security by themselves. They are stopgaps that can create windows for crucial political solutions and reduce needless bloodshed while political solutions ripen. But conflict-management mechanisms do little in and of themselves to achieve political solutions, and they may even delay conflict resolution because they stop wars from being fought to their natural end. A conflict-management institution can also foreclose more meaningful political dialogue by making an unstable status quo more bearable. Still, the lives saved and the destruction prevented might make the delay of a real political resolution worthwhile. The Middle East needs more UNIFILs, but it is crucial to keep in mind the limitations of a conflict-management approach if such forums are to be useful for advancing long-term security. They are no substitute for politics.

Notes

- For more information on small skirmishes along the Blue Line, see Neeraj Singh, ed., “UNIFIL Three Years On,” Al-Janoub UNIFIL Magazine, January 31, 2010, http://reliefweb.int/report/lebanon/unifil-magazine-al-janoub-january-2010-no06.

- Harriet Sherwood, “Israeli Colonel, Three Lebanese Soldiers and Journalist Killed in Border Clashes,” Guardian, August 3, 2010, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2010/aug/03/lebanon-israel-border-violence-soldiers.

- UN official, interview with the author, Beirut, Lebanon, May 18, 2017.

- “UNIFIL Statements on the Incident at El Adeisse, 03 August 2010,” UNIFIL press release, August 4, 2010, https://unifil.unmissions.org/unifil-statements-incident-el-adeisse-03-august-2010.

- “Major-General Beary Chairs 100th Tripartite Meeting with LAF and IDF Officials,” UNIFIL press release, November 9, 2016, https://unifil.unmissions.org/major-general-beary-chairs-100th-tripartite-meeting-laf-and-idf-officials.

- “UNIFIL Statements on the Incident at El Adeisse, 03 August 2010.”

- Major General (retired) Abdul Rahman Chehaitli, interview with the author, Beirut, Lebanon, July 6, 2017.

- UNIFIL official, interview with the author, Naqoura, Lebanon, August 2, 2017.

- “Military Confidence-Building,” United Nations Office of Disarmament Affairs, accessed September 18, 2017, https://www.un.org/disarmament/cbms/. See also “OSCE Guide on Non-Military Confidence-Building Measures (CBMs),” OSCE Secretariat’s Conflict Prevention Centre, Operations Service, 2012, http://www.osce.org/cpc/91082?download=true; and Simon J. A. Mason and Matthias Siegfried, “Confidence Building Measures (CBMs) in Peace Processes,” in Managing Peace Processes: Process Related Questions: A Handbook for AU Practitioners, Vol. 1 (Geneva: African Union and the Centre for Humanitarian Dialogue, 2013), 57–77, http://www.swisspeace.ch/fileadmin/user_upload/Media/Publications/Journals_Articles/_AU_Handbook_Confidence_Building_Measures_in_Peace_Processes.pdf.

- Oliver Ramsbotham, Tom Woodhouse, and Hugh Miall, eds., Contemporary Conflict Resolution, 4th ed. (Hoboken, N.J.: Wiley, 2016); and Owen Frazer and Lakhdar Ghettas, eds., “Conflict Transformation in Practice,” Cordoba Foundation of Geneva, Cordoba Now Forum, 2013, http://www.css.ethz.ch/content/dam/ethz/special-interest/gess/cis/center-for-securities-studies/pdfs/Conflict_Transformation_in_Practice_2013.pdf.

- Vanessa Newby, “Walk the Line: An Investigation of the Micro-Processes of a UN Peacekeeping Mission,” Issam Fares Institute for Public Policy and International Affairs working paper, September 2016, https://www.aub.edu.lb/ifi/publications/Documents/working_papers/20160927_walk_the_line.pdf.

- “Four Dead in Israel-Lebanon Border Skirmish,” Associated Press, August 3, 2010, https://www.thenational.ae/world/mena/four-dead-in-israel-lebanon-border-skirmish-1.548455.

- Beate Hamizrachi, The Emergence of the South Lebanon Security Belt: Major Saʿad Haddad and the Ties with Israel, 1975–1978 (New York: Praeger, 1988).

- Further complicating matters, Israel claims that the occupied territory in question is Syrian, not Lebanese.

- John Reed and Erika Solomon, “Israel and Lebanon Clash over Maritime Border amid Oil Interest,” Financial Times, March 28, 2017, https://www.ft.com/content/0250eed4-1082-11e7-b030-768954394623. See also General Nizar Abdel-Kader, “Potential Conflict Between Lebanon and Israel Over Oil and Gas Resources—A Lebanese Perspective,” National Defense Magazine (Lebanon), 78 (October 2011), https://www.lebarmy.gov.lb/en/content/potential-conflict-between-lebanon-and-israel-over-oil-and-gas-resources-%E2%80%93-lebanese.

- For more on the debate that ensued after the withdrawal of the South Lebanon Army, see “The Cost of Collaboration: Ten Years On, Giles Trendle Recalls Israel’s Betrayal of the South Lebanon Army,” Al Jazeera, May 26, 2010, http://www.aljazeera.com/focus/2010/05/201051992011673189.html; and Nicholas Blanford, “The Quandary of an SLA Amnesty,” Daily Star, August 16, 2005, http://www.dailystar.com.lb//Opinion/Commentary/2005/Aug-16/95688-the-quandary-of-an-sla-amnesty.ashx.

- During the 2006 war, Hezbollah was able to fire very few medium- and long-range rockets. Most of the projectiles it launched had a range of thirty kilometers or less. It launched a small number of rockets with longer ranges, up to ninety kilometers. “Civilians under Assault: Hezbollah’s Rocket Attacks on Israel in the 2006 War,” Human Rights Watch, August 28, 2007, https://www.hrw.org/report/2007/08/28/civilians-under-assault/hezbollahs-rocket-attacks-israel-2006-war.

- UNSCR 1701 (2006), August 11, 2006, http://www.securitycouncilreport.org/atf/cf/%7B65BFCF9B-6D27-4E9C-8CD3-CF6E4FF96FF9%7D/PKO%20SRES1701.pdf.

- Assaf Orion, “UNIFIL II, Ten Years On: Strong Force, Weak Mandate,” INSS Insight 844, August 14, 2016, http://www.inss.org.il/publication/unifil-ii-ten-years-on-strong-force-weak-mandate/.

- For more on the debate surrounding interpretations of UNSCR 1701, see Karim Makdisi, “Constructing Security Council Resolution 1701 for Lebanon in the Shadow of the ‘War on Terror,’” International Peacekeeping 18, no. 1 (2016): 4–20; and “Security Council Calls for End to Hostilities Between Hizbollah, Israel, Unanimously Adopting Resolution 1701 (2006),” 5511th Meeting (Night), Security Council Press Release SC/8088, August 11, 2006, https://www.un.org/press/en/2006/sc8808.doc.htm.

- As of August 2017, UNIFIL had 10,520 peacekeepers from forty-one nations. Some of the most important contingents come from NATO members France, Italy, Germany, and Spain. For a complete breakdown of troop contributions, see “UNIFIL Troop-Contributing Countries,” UNIFIL, accessed September 19, 2017, https://unifil.unmissions.org/unifil-troop-contributing-countries.

- For more on the implementation of UNSCR 1701, see the full reports from the secretary general, which include notes on the tripartite meetings and the incidents along the Blue Line since 2006: “United Nations Documents on UNIFIL,” United Nations, accessed September 19, 2017, http://www.un.org/en/peacekeeping/missions/unifil/reports.shtml.

- John Molloy, interview with the author, Naqoura, Lebanon, August 2, 2017.

- UNIFIL directly employs six hundred Lebanese nationals and uses local contractors for all support functions, according to UNIFIL spokesman Andrea Tenenti (email to the author, September 8, 2017). See also “UNIFIL: Economic Dimension,” UNIFIL, accessed October 20, 2017, https://unifil.unmissions.org/unifil-economic-dimension-multimedia-product-photos-and-video-inside.

- At the time of this writing in October 2017, the UNIFIL Maritime Task Force consists of seven ships, led by a Brazilian flagship. Since 2006, the UNIFIL naval force has hailed more than 77,000 ships and referred about 9,100 to the Lebanese Navy for further inspection. “UNIFIL Maritime Task Force,” UNIFIL, accessed September 18, 2017, https://unifil.unmissions.org/unifil-maritime-task-force.

- Justyna Pawlak and Adrian Croft, “EU Adds Hezbollah’s Military Wing to Terrorism List,” Reuters, July 22, 2013, http://www.reuters.com/article/us-eu-hezbollah-idUSBRE96K0DA20130722; and Nasser Chararah, “No Separation in Hezbollah Military and Political Wings,” Al-Monitor, July 26, 2013, http://www.al-monitor.com/pulse/originals/2013/07/hezbollah-military-political-nature-eu-decision.html.

- See, for example, Ian Fisher, “Syria Blames Israel for Attack on Damascus Airport,” New York Times, April 27, 2017, https://www.nytimes.com/2017/04/27/world/middleeast/syria-damascus-airport-israel-hezbollah.html?_r=0.

- See Isabel Kershner, “Israel Approves Withdrawal from Part of a Village on Lebanon Border,” New York Times, November 17, 2010, http://www.nytimes.com/2010/11/18/world/middleeast/18mideast.html. For a description of the Israeli withdrawal, see Frederic C. Hof, “A Practical Line: The Line of Withdrawal from Lebanon and Its Potential Applicability to the Golan Heights,” Middle East Journal 55, no. 1, (2001): 25–42. For a detailed description of the issue of the Shebaa Farms, see Asher Kaufman, “Who Owns the Shebaa Farms? Chronicle of a Territorial Dispute,” Middle East Journal 56, no. 4 (2002): 576–95.

- “Israel Accuses Hezbollah of ‘Dangerous Provocation’,” Al-Monitor, June 22, 2017, http://www.al-monitor.com/pulse/afp/2017/06/israel-lebanon-hezbollah-conflict.html.

- Joy Bernard, “Nikki Haley Embroiled in IDF, UNIFIL Dispute about Hezbollah Threat,” Jerusalem Post, June 11, 2017, http://www.jpost.com/Israel-News/Nikki-Haley-embroiled-in-IDF-UNIFIL-dispute-about-Hezbollah-threat-496573.

- Ben Caspit, “Tensions Flare between IDF, UN Peacekeepers in Lebanon,” Al-Monitor, June 26, 2017, http://www.al-monitor.com/pulse/originals/2017/06/israel-hezbollah-unifil-lebanon-wall-war-security-idf-us.html.

- Lebanese Armed Forces Brigadier General (ret.) Amin Hoteit, interview with the author, Beirut, Lebanon, July 19, 2017.

- “Israel Attacks Southern Lebanon after Hezbollah Targets Army Convoy,” Al-Akhbar, January 28, 2015, http://english.al-akhbar.com/node/23433.

- Timur Goksel, interview with the author, Beirut, Lebanon, July 20, 2017.

- UNIFIL, “Working with UNIFIL, LAF Confirms Eight New Blue Line Points,” UNIFIL press release, July 13, 2017, https://unifil.unmissions.org/working-unifil-laf-confirms-8-new-blue-line-points.

- In 1932, the village of Ghajar was designated part of Syria rather than Lebanon. Israel occupied the village in 1967. After the Israeli withdrawal from southern Lebanon in 2000, Ghajar was bounded by Lebanon on one side and Israel on the other. Lebanon claims that Syria has relinquished its claim to Ghajar, but that claim is disputed, crucially, by Ghajar residents themselves, who identify as Syrians living under Israeli occupation and who largely have accepted Israeli citizenship.

- “Ban Welcomes Israel’s Decision to Withdraw Troops from Northern Ghajar,” UN News Centre, November 18, 2010, http://www.un.org/apps/news/story.asp?NewsID=36790#.WYwwjFojFE4.

- Chehaitli, interview with the author.

- UNIFIL official, Naqoura, interview with the author.

- Chehaitli, interview with the author.

- The author participated in the tour.

- “Hariri from Naqoura: I Am Here to Reaffirm My Government’s Commitment to Resolution 1701,” press office of the president of the Council of Ministers Saad Hariri, press release, April 21, 2017.

- Nicholas Blanford, “Hezbollah’s Defiant Signal to Israel, Lebanon, and the UN,” Christian Science Monitor, April 25, 2017, https://www.csmonitor.com/World/Middle-East/2017/0425/Hezbollah-s-defiant-signal-to-Israel-Lebanon-and-the-UN.

- Hezbollah official, interview with the author, Blue Line, April 20, 2017.

- Marissa Sullivan, “Hezbollah in Syria,” Middle East Security Report 19, April 2014, http://www.understandingwar.org/sites/default/files/Hezbollah_Sullivan_FINAL.pdf.

- “Hezbollah’s Shot at Permanency in Syria,” Stratfor, April 6, 2016, https://worldview.stratfor.com/analysis/hezbollahs-shot-permanency-syria; and Ibrahim Haidar, “Hezbollah Reorganizing Its Forces, the Elite in the South and the Missiles between Lebanon and Syria” [in Arabic], An-Nahar, May 5, 2017, http://www.annahar.com/article/548957–حزب-الله-يعيد-تنظيم-قواته-النخبة-المقاتلة-في-الجنوب-والصواريخ-بين-لبنان-وسوريا.

- F. William Engdahl, “Next Stage of War in the Middle East? The Golan Heights, Israel, Syria and a Whole Lot of Oil,” New Eastern Outlook, March 30, 2017, https://www.sott.net/article/346759-Next-stage-of-war-in-the-Middle-East-The-Golan-Heights-Israel-Syria-and-a-whole-lot-of-oil.

- Saeed Kamali Dehghan, “Top Iranian General and Six Hezbollah Fighters Killed in Israeli Attack in Syria,” Guardian, January 19, 2015, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2015/jan/19/top-iranian-general-hezbollah-fighters-killed-israel-attack-syria.

- Tom Perry and Laila Bassam, “Hezbollah: We Don’t Want War with Israel but Do Not Fear It,” Reuters, January 30, 2015, http://www.reuters.com/article/us-mideast-crisis-hezbollah-israel/hezbollah-we-dont-want-war-with-israel-but-do-not-fear-it-idUSKBN0L31QE20150130?irpc=932; and “Israel Confirms Hezbollah Not Interested in Escalation,” Ynet News, January 29, 2015, https://www.ynetnews.com/articles/0,7340,L-4620659,00.html.

- Chehaitli, interview with the author.

- Senior general, Lebanese Armed Forces, interview with the author, Baabda, Lebanon, May 11, 2017.

- Hezbollah’s alleged rearmament and military operations in southern Lebanon were the crux of a public fight over the renewal of UNIFIL’s mandate in August 2017. Nikki Haley, the U.S. ambassador to the UN, openly criticized UNIFIL and its commander for failing to try to disarm Hezbollah and for ignoring political demands from the United States and Israel for UNIFIL to execute the spirit and not just the letter of UNSCR 1701. UNIFIL supporters retorted that the Security Council would never approve a more aggressive mandate for the same reason that it had not done so in 2006, and that in any case, Hezbollah and other Lebanese factions would quickly paralyze any peacekeeping mission that actively sought to disarm Hezbollah. Throughout this debate, UNIFIL and its supporters averred that they had seen no evidence of Hezbollah rearming within UNIFIL’s area of operations, whereas Haley and the Israelis pointed to the Hezbollah media tour of April 2017 as proof that Hezbollah’s military was active in the border area. See, for example, Nikki Haley, “Confronting Hezbollah in Lebanon,” Jerusalem Post, September 5, 2017, http://www.jpost.com/Opinion/In-special-Jpost-oped-Haley-says-time-for-UNIFIL-to-confront-Hezbollah-504268; Moshe Arens, “Lessons Learned from Hezbollah,” Haaretz, September 4, 2017, http://www.haaretz.com/opinion/.premium-1.810392; Rick Gladstone, “UN Peacekeepers in Lebanon Get Stronger Inspection Powers for Hezbollah Arms,” New York Times, August 30, 2017, https://www.nytimes.com/2017/08/30/world/middleeast/united-nations-security-council-peacekeepers-lebanon-hezbollah-israel.html; James Haines-Young, “New UNIFIL mandate? Business as Usual,” Daily Star, September 1, 2017, http://www.dailystar.com.lb/News/Lebanon-News/2017/Sep-01/417943-new-unifil-mandate-business-as-usual.ashx; and Sarah El Deeb, “UN Force in Lebanon Pushes Back after US, Israeli Criticism,” Associated Press, August 23, 2017, https://apnews.com/e79c9eef856d4e1f905bfb9b76aa27b7.

- UN official, interview with the author.

- Newby, “Walk the Line,” 19.

- Columba Peoples and Nick Vaughan-Williams, Critical Security Studies: An Introduction (London and New York: Routledge, 2015)