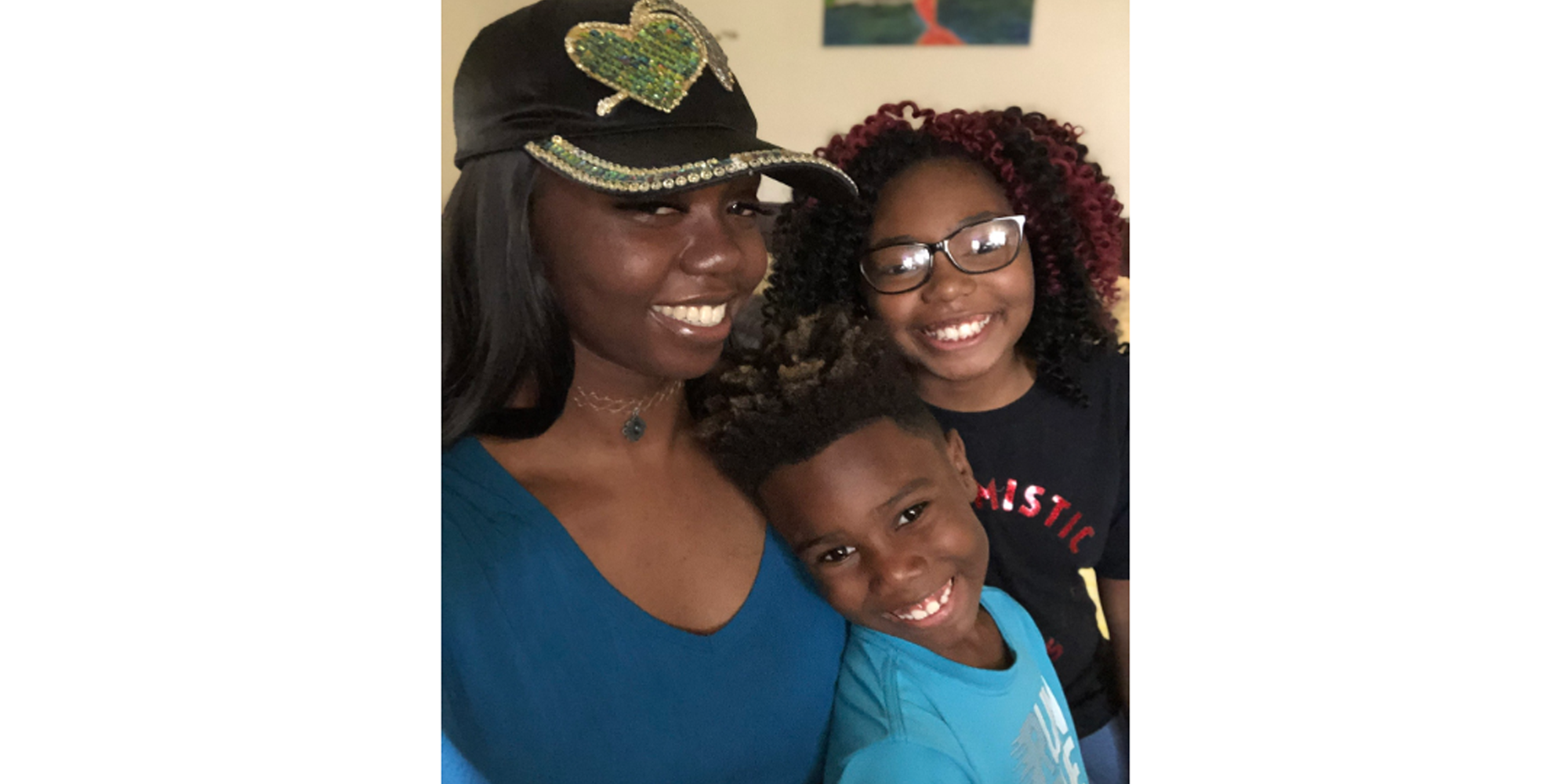

KiAra Cornelius, an African-American, single mother of two, desperately wanted a school that would be more challenging for her children, particularly her son, Senoj, a straight-A student.1

Tehani, a divorced Hispanic mother of three who has been homeless, wanted a school with choir and drama programs for her daughter Brandy, a passionate singer and actor.2

Both mothers lived in Columbus, Ohio, whose public school system has an overall D rating on the state report card, and an F rating for academic achievement.3 They sought out whatever opportunities they could: Cornelius chose a charter school, and Tehani invoked a provision in federal law that allows homeless families to keep children in the school they attended before losing their home, in her case a C-rated suburban district.4 But each of those options proved unsatisfactory from an educational perspective, and also did nothing to help these families transition out of neighborhoods and housing they deemed unsafe.

The suburban Columbus school districts with more course offerings, more resources and higher test scores, as well as safer neighborhoods—such as Dublin, Hilliard, Gahanna, and Olentangy—were out of price range for these mothers.5 A long history of exclusionary zoning—local rules ranging from prohibitions on apartment buildings in some areas to requirements that multifamily units be built with expensive facades—effectively bars families with modest means from living in these communities and sending their children to the public schools.

Beginning in 2018, a small philanthropic experiment—Move to PROSPER—provided Cornelius, Tehani, and eight other low-income single mothers the opportunity to live in high opportunity neighborhoods such as Lewis Center, Gahanna, Hilliard, and Dublin. The program has a particular focus on improving the life chances of children. “It all started with the children,” says Amy Klaben, who is Project Facilitator of Move to PROSPER (which stands for Providing Relocation Opportunities to Stable Positive Environments).6

This report tells the story of these two mothers with low incomes, who, just like parents of all backgrounds, want a good education for their children. The report also outlines the experience of a third mother—Janet Williams—who badly wanted to be part of Move to PROSPER, but currently is shut out of the program because of its limited resources.7

The first part of the report lays out the challenges that low-income families face in the Columbus area, including the prevalence of exclusionary zoning that is so common throughout the country. The second part outlines the origins of Move to PROSPER as a small-scale pilot to help families overcome these obstacles. The third part—the bulk of the report—seeks to uplift the voices of three striving families looking for a better education for their children. The fourth part concludes with policy recommendations.

The Challenge: Segregation and Exclusionary Zoning in Columbus Ohio

Columbus, Ohio is distinguished by its central location in the state, leading to the decisions to select it as the state capital in 1812 and locate The Ohio State University there in 1872.8 Today, Columbus is Ohio’s largest city, with a population in excess of Cleveland and Cincinnati combined.9

Though mostly known as an academic and political powerhouse within Ohio, Columbus also has a more dubious national distinction. A 2015 study by Richard Florida of the University of Toronto found Columbus to be the second most economically segregated large metropolitan region in the United States (after Austin, Texas).10 Another 2015 study, by Harvard University professor Raj Chetty and colleagues, found that of the fifty largest metro areas in the United States, Columbus ranked near the very bottom—forty-fifth—in social mobility.11 Chetty and colleagues further found that high levels of segregation such as that found in Columbus was correlated with low levels of social mobility.12

Columbus’s economic and racial segregation did not arise by accident. In the early part of the twentieth century, large numbers of Black people migrated from the American South to Northern cities. Between 1910 and 1920, Ohio’s Black population grew by 67 percent.13 Columbus was particularly inhospitable to these migrants. According to Frank Quillin’s 1913 study of six Ohio cities, The Color Line in Ohio, “Columbus, the capital of Ohio, has a feeling toward the Negroes all its own. In all my travels in the state, I found nothing just like it.” Quillin noted: “It is not so much a rabid feeling of prejudice against the negroes simply because their skin is black as it is a bitter hatred for them.”14 White Columbus-area residents enforced segregation of Black people through multiple means.

Racially Restrictive Covenants, Redlining, and School Board–Sponsored Racial Segregation

Racially restrictive covenants were widely employed in the Columbus region. According to a study by the late Iowa State University professor Patricia Burgess, in the 1920s, 67.5 percent of all Columbus-area subdivisions contained covenants preventing properties from being sold to Black people.15 One 1923 deed, for example, said the home couldn’t be used as a slaughterhouse or be sold to a person of African descent.16 Many of the covenants also included minimum square footage requirements to foster economic segregation.

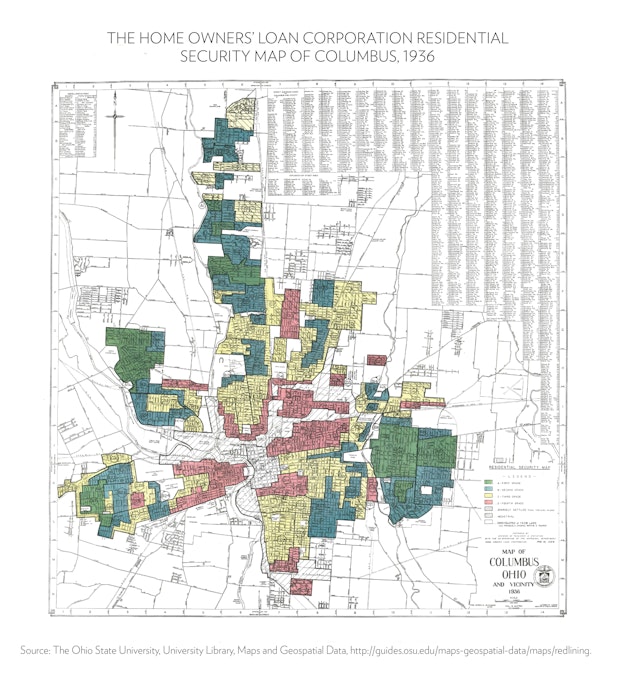

In the 1930s, the federal government exacerbated segregation by race and class in Columbus and nationally when it issued “redline” maps that advised against insuring mortgages in areas that had large Black populations. In one city, the Federal Housing Administration denied insurance for a white developer with a project located near an African-American community until the builder agreed to construct a half-mile, six-foot-high concrete wall to separate the two neighborhoods.17 The Home Owners’ Loan Corporation Residential Security Map of Columbus in 1936 (shown in Figure 1) went so far as to color-code which areas were the most desirable (green and blue), and which were the least desirable (yellow and red).

Figure 1

The cumulative effect of these policies was high levels of residential segregation. Within Columbus, for example, by 1970, 71 percent of all Black people lived in twenty-three contiguous Census tracts. Researchers found that in that year, Columbus’s Black/white dissimilarity index (in which 0 represents perfect integration and 100 is absolute segregation) was 84.1—higher than the already high national average of 79.18

Columbus’s residential segregation was exacerbated by purposeful school segregation. In a 1977 U.S. District Court decision, Penick v. Columbus Board of Education, Judge Robert Duncan, a Richard Nixon appointee, found that the school board had intentionally segregated schools over many years.19 Although separate schools for Black and white students were officially abolished in Columbus in 1881, the school board had gerrymandered school lines to foster segregation for decades afterward.20 By the 1975–76 school year, 70 percent of Columbus students attended schools that were either 80–100 percent Black or 80–100 percent white.21

Judge Duncan noted the “reciprocal effect” between residential and school segregation. Because schools were based in neighborhoods, housing segregation fed school segregation, and at the same time, “the racial identification of the school in turn tends to maintain the neighborhood’s racial identity, or even promote it.”22

To remedy the school segregation found in Penick, Columbus engaged in a system-wide desegregation effort beginning in 1979. Of the district’s 83,000 students, 42,000 were sent to a new school, 37,000 by bus.23 The local business community took great pride in the fact that desegregation occurred peaceably, and that Columbus did not see the violent resistance of other Northern cities, such as Boston, Massachusetts.24

But while Columbus didn’t see Boston’s “burning of buses,” it did pursue “the banality of unequal opportunity” through “elusive” means, notes historian Gregory S. Jacobs.25 As was typical of school desegregation orders, it was limited to the city and did not reach the suburbs. Moreover, Columbus developed an unusual mechanism that allowed white families to avoid desegregation. While throughout most of the country, school district lines are coterminous with city lines, Columbus developed so-called “common areas”—large swaths of Columbus residential areas that were served not by Columbus Public Schools (now known as Columbus City Schools), but by suburban school districts, such as Dublin, Gahanna–Jefferson, and Hilliard.26 This system allowed white, wealthier city residents to use suburban schools—which were not impacted by the desegregation order—while living within the City of Columbus. A full 40 percent of Columbus addresses were served by suburban districts, which were not part of the school desegregation effort.27

The shift in residential development after the Penick lawsuit was filed in 1973 was sudden and severe. Development of single-family houses within the 60 percent of Columbus served by Columbus Public Schools ground to a halt, while the 40 percent of Columbus served by various suburban public schools flourished. Writes Jacobs: “the Columbus Public School District had been tacitly designated a residential development redline, within which virtually no single-family home building would take place.”28

The desegregation order was lifted after six short years.29 And while school busing did reduce segregation within Columbus Public Schools, it exacerbated segregation between city and suburb, as the system became poorer and Blacker over time, Jacobs writes.30 Black students constituted 29 percent of the city’s student population in 1970, compared with 54 percent today. Meanwhile, the white share of the city’s student population declined from more than two-thirds in 1975 to less than one quarter today.31

Economic Covenants and Zoning

While racially restrictive covenants were struck down by the U.S. Supreme Court, redlining was outlawed by the U.S. Congress, and de jure segregation was prohibited by the Penick court order, economic discrimination continued unabated—a practice that disproportionately hurt Black and Hispanic residents. To this day, for example, exclusionary zoning policies that ban, by government fiat, the building of affordable housing in the form of apartment buildings and other multifamily units are perfectly legal. As Jason Reece of Ohio State University notes, “We have a Fair Housing Act, but if they’re not caught discriminating by race … they can still discriminate by class. We’ve learned that if they do that with zoning, they get the same effect. This is why we have so much economic segregation.”32

The late Iowa State University professor Patricia Burgess documented in great detail the ways in which two forms of economic discrimination in Columbus and surrounding suburbs have contributed to the region’s economic and racial segregation: economically restrictive covenants and economic zoning.

Burgess began by painstakingly documenting the use of economically restrictive covenants by private developers. After racially restrictive covenants were struck down by the U.S. Supreme Court in 1948, developers doubled down on socioeconomically “restrictive covenants” that prohibited land from being used to build houses below a certain price or size. In the Columbus area, Burgess found, “If land developers did not directly control by race who used the land, they could and did attempt to control by socioeconomic status who used it, as well as how it could be used. Fully two-thirds of the platted subdivisions limited construction to single-family homes or residential use only.” Moreover, “subdivisions aimed at the upper middle class” imposed minimum square footage requirements and often banned one-story homes.33

Zoning laws codified these restrictive covenants, Burgess says. Zoning ordinances, which limit the ability of individuals to build what they want on their property, are justified in order to promote “public health, safety, and welfare,” Burgess noted, and they do so when they prohibit the construction of a toxic factory in a residential area, for example. But too often, in the Columbus area, they were used to promote private interests—including the desire of white and upper-middle-class people to keep Black and lower-income individuals out of their neighborhoods—by banning apartment buildings, multifamily units, or even smaller, single family homes.34 Zoning laws, she writes, often “protected rich from poor and white from black.” In that way, “planning served the private interest.”35

Exclusionary zoning makes it harder for low-income families to live in high opportunity neighborhoods because it artificially increases the price of housing in those communities. Dense housing is more affordable than single-family homes for four reasons: (1) because density provides more units per acre, land costs are cheaper for the developer; (2) dense units (such as apartments) have fewer exterior walls, which keeps construction costs lower; (3) compact developments reduce infrastructure costs for trunk lines and treatment facilities; and (4) dense housing increases overall supply relative to demand, resulting in lower prices for consumers.36

Exclusionary zoning has been found to be a major explanation for economic segregation that keeps poor and working-class families out of middle-class and upper-middle-class neighborhoods. An important 2010 study of fifty metropolitan areas by Jonathan Rothwell of the Brookings Institution and Douglas Massey of Princeton University found that “a change in permitted zoning from the most restrictive to the least would close 50 percent of the observed gap between the most unequal metropolitan area and the least, in terms of neighborhood inequality.”37

Move to PROSPER

Today, a key reason that single mothers like KiAra Cornelius, Janet Williams and Tehani have trouble accessing low-crime neighborhoods with good schools is that exclusionary zoning remains widespread. Referring to high opportunity communities outside of Columbus, developer Michael Kelley of Kelley Companies notes, “One of the reasons why there’s not affordable housing units in suburbs like Dublin and Hilliard and New Albany is exclusionary zoning.”38

Limiting areas to single-family homes is only the most blatant mechanism for excluding families of modest means. Kelley notes that some communities require that apartments have brick façades, which are more expensive than something like vinyl siding, and put the apartment “out of the price range of anything affordable.”39

Amy Klaben, an attorney and the former president of Homeport, a nonprofit housing developer, says some Columbus suburbs don’t want a development where the majority of the units are three- or four-bedroom apartments because they don’t want apartments that will accommodate parents with children.40 In essence, these suburbs will only approve housing units that are expensive enough so that “the property taxes generated cover the cost of the children in schools.”41 Just as Southerners kept people out of voting booths with literacy tests, so the “brick façade” requirement becomes a more sophisticated way of keeping low-income families out of suburban apartments. Moreover, in Central Ohio, Klaben says, landlords can discriminate based on source of income, refusing to take any Section 8 Housing Choice Voucher recipients.42

Klaben and Kelley considered filing a lawsuit that would go after these structural impediments to opportunity—the exclusionary zoning that makes it so difficult to build affordable housing in high opportunity areas.43 But lawsuits are expensive and difficult to win, since economic discrimination remains legal. So, in the short term, they decided to do something that did not require court action: give at least a small number of families the help they need to overcome exclusionary zoning.

The need was clear. Klaben had spent thirty years as a lawyer, volunteer, and nonprofit developer promoting affordable housing and felt good about that work, but says many of the affordable housing projects she helped facilitate still were located in high-poverty neighborhoods that faced significant challenges. Families would have better housing due to her help, she said, but the children would “still go to failing schools.” Going forward, she said, she wanted to “think differently about it.”44

Klaben read Harvard University professor Raj Chetty’s groundbreaking research on the benefits of a federal program called Moving to Opportunity, which found that, when children moved with their families to a better neighborhood before age thirteen, they later earned much more as adults.45 The benefits were dramatic: The total mean income as adults for early movers was 31 percent higher than for the control group, which applied for the program but did not receive the opportunity. The researchers also observed a 16 percent increase in the likelihood of attending college between the ages of 18 and 20.46

Chetty’s research is consistent with many other studies that find substantial benefits for students who have a chance to attend economically mixed rather than high-poverty schools—where peers are more likely to be academically engaged, parents are in a position to be more actively involved in school affairs, and teachers are more likely to be experienced and teaching in their field of expertise. Low-income students can do very well if given the right learning environment, and research shows having the chance to live in a middle-class neighborhood and attend middle-class schools offers substantially stronger opportunities for students.

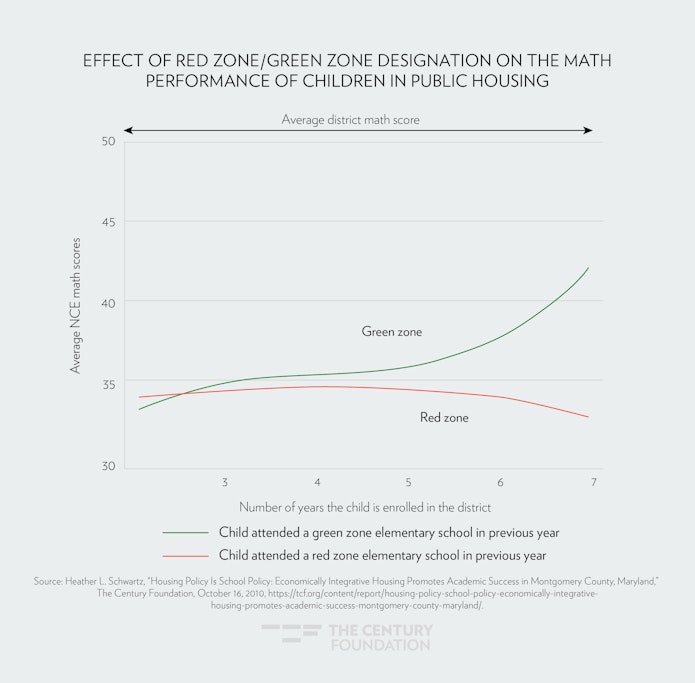

In a 2010 Century Foundation report, for example, the RAND Corporation’s Heather Schwartz compared the effects of two approaches to improving achievement for low-income students.47 On the one hand, in 2000, Montgomery County, Maryland public schools began spending about $2,000 extra per pupil in higher-poverty “red zone” schools to achieve all-day kindergarten, reduced class sizes, and investments in teacher development. At the same time, a parallel “inclusionary zoning” housing strategy gave low-income families a chance to live in, and attend schools, in neighborhoods with lower-poverty “green zone” schools.

Schwartz examined 858 children randomly assigned to public housing units scattered throughout Montgomery County and enrolled in Montgomery County public elementary schools between 2001 and 2007 and asked: Who performed better—public housing students in higher poverty neighborhoods where schools have extra financial resources or students in lower poverty schools that spend less? The results are outlined in Figure 2.

Over time, low-income public housing students in “green zone” schools performed at 0.4 of a standard deviation better in math than low-income public housing students in “red zone” schools with more resources. Because educational interventions typically have an effect size on the order of 0.1 of a standard deviation, the outcomes in Montgomery County are considered quite powerful. Low-income students in “green zone” schools cut their large initial math gap with middle-class students in half. The reading gap was cut by one-third. Schwartz estimates that most of the effect (two-thirds) was due to attending low-poverty schools, and some (one-third) was due to living in low-poverty neighborhoods.48

Figure 2

Based on this type of research, Klaben and Kelley worked with others—including professors Rachel Kleit and Jason Reece of The Ohio State University—to come up with a housing strategy focused on single mothers with school-age children in Columbus. Klaben says the overriding impetus was: “What can we do about the kids?”49 That is how Move to PROSPER was born.50

Move to PROSPER looked at data from The Ohio State University’s Kirwan Institute for the Study of Race and Ethnicity that identifies high-opportunity neighborhoods that provide “sustainable employment, high performing schools, a safe environment, access to high quality health care, adequate transportation, quality child care, safe neighborhoods, and institutions that facilitate civic and political engagement.”51 Organizers decided to make apartments available in four high-opportunity communities within the Dublin, Hilliard, Gahanna, and Olentangy school districts.

A few developers, such as Michael Kelley of the Kelley Companies and CASTO, a real estate firm founded in 1926, agreed to rent some units in these communities at $100 below market rate.52 Klaben and others then raised additional funds so Move to PROSPER could provide a total discount of $400 per month off market rate rentals for a three year period.53 Funds were also raised to provide coaching to participants about making choices and setting goals for housing, finances, education, careers, and health.54 (Importantly, there is also counseling in the form of implicit bias training for the landlords.)55 To assess the program, Rachel Kleit agreed to chair the steering committee and Jason Reece became the evaluator.

Organizers had sufficient funds to create a pilot program with ten families. Participants had to be low-income single mothers with between one and three children ages 13 and under and live in low-opportunity neighborhoods. The children had to attend low-performing schools in Columbus or lower-performing suburban districts.56

When the program was launched in March 2018, Klaben said some skeptics asked: “Is anybody going to want to move to these suburban areas and leave their neighborhoods behind?”57 The expectation was that applicants might face discrimination based on class or race in the suburbs and not want to move away from their support network.

Then the applications began to flow in. By June 2018, the program had more than 300 applicants for ten spots.58 The program was harder to get into than Harvard. When selections were made, the group’s household income ranged from $23,000 to $37,500 (at or below 50 percent of the area’s median income).59 Seven were African American, two white, and one a Latina.60 Participants began moving into their new apartments in August 2018.61

Three Families

My Century Foundation colleague Michelle Burris and I had a chance to interview three mothers—two of whom were accepted into the program and one who was shut out because of resource limitations. Below are their stories.

KiAra Cornelius

KiAra Cornelius, an African-American single mother, who works as a claims analyst at United Healthcare, has two children, KiMarra Jones (age 12) and Senoj Jones (age 9).62 A high school graduate, Cornelius was living in the South end of Columbus a few years ago when she suffered a couple of difficult setbacks. First, the basement in the home she was living in flooded, causing a serious mold issue. On top of that, she and her children were in a car accident, sending her to the hospital. The kids were fine, she said, but the bills started piling up, so she moved in with her mother, her mother’s fiancé, and Cornelius’s siblings a few blocks away.63

Cornelius had grown up in South Columbus but says the community deteriorated over time. “It’s definitely not the same anymore,” she says. “It can be dangerous,” with “gang-related activity,” and trash littering the sidewalks. Before the basement flood, Cornelius would drive her children to her mother’s home a few blocks away because she worried that if they walked, they might “get crossed up” as an “innocent bystander.”64

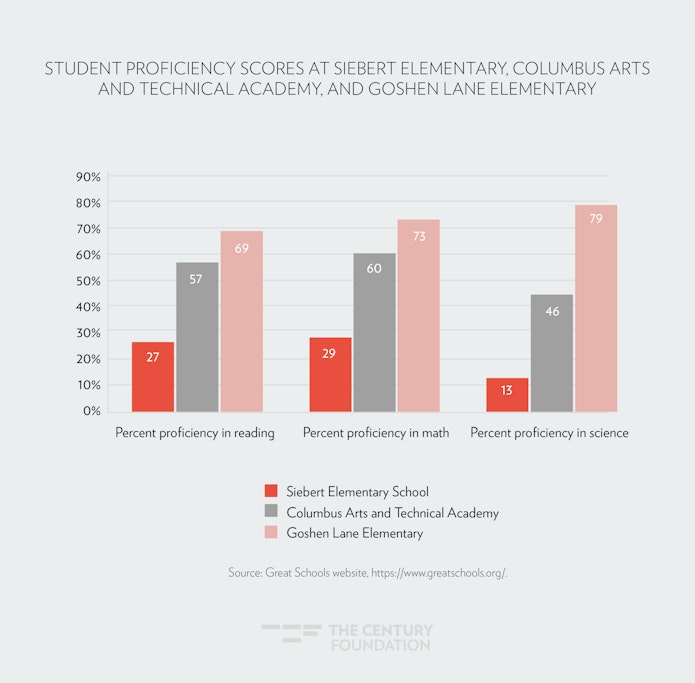

The local public schools in Cornelius’s South Columbus neighborhood have struggled over time. At Siebert Elementary School, where 91 percent of students come from low-income households, just 27 percent are proficient in reading, 29 percent in math, and 13 percent in science.65 (Of course, reading and math scores are just two indicators of school quality—and they reflect neighborhood poverty levels as well as what schools are teaching—but such low levels of proficiency are nevertheless deeply troubling.) Cornelius opted to send her kids to a charter school—Columbus Arts and Technical Academy in South Columbus.66 The school, where 87 percent of students are low-income, performed somewhat better, with 57 percent of students proficient in reading, 60 percent in math, and 46 percent in science.67

While living with her mother, Cornelius was looking for a better housing and schooling situation, and one night, around 2:00 a.m., while searching online for opportunities for single mothers, she came across the Move to PROSPER program.68 She was particularly interested in a better opportunity for her son Senoj, a straight-A student.69

With Move to PROSPER’s support, she was able to move to an apartment in Gahanna, a middle-class suburb of Columbus. The neighborhood is clean and safe and the kids are free to walk around. “It’s just a total difference” from South Columbus, she says.70

And the schools are stronger. She says Senoj is receiving the challenge he needs at Goshen Lane Elementary. At the school, 69 percent of students are proficient in reading, 73 percent in math, and 79 percent in science (see Figure 3).71 Cornelius’s daughter, KiMarra, has also benefited from attending the high-performing Gahanna South Middle School, where 75 percent of students are proficient in reading, 67 percent in math, and 89 percent in science.72 The teachers push her “the extra step” in a way they didn’t at her charter school.73

Figure 3

Cornelius says the Gahanna schools have more resources and smaller classes, and give students the freedom to bring laptops home from school.74 Gahanna parents are actively involved. Parents organized, for example, to get an app that allowed families to know when school buses would be arriving.75 Teachers are also very diligent about reaching out. “I swear I get email every day” from teachers, Cornelius says. “They really keep you in the loop about what’s going on.”76

Cornelius also likes the student diversity. At Columbus Arts and Technology Academy, 78 percent of students were African American like her daughter, but at Gahanna South Middle School, the Black population constitutes 26 percent of the student body, so KiMarra is stretched to go beyond “her comfort zone” and meet students of many different races and ethnicities. At the school, 59 percent of students are white, 7 percent Hispanic, 6 percent two or more races, and 3 percent Asian. “I’m proud of her for stepping outside the box, hanging with different people … just to learn different things about how other cultures work.” She says: “The Gahanna school has definitely given her a more diverse world.”77 Cornelius reports that her kids have not faced discrimination in Gahanna.78

Cornelius says of the new schooling opportunities for her kids: “It is much, much better.”79

Tehani

Tehani, an Hispanic single mother, has three children: a daughter, Brandy (age 14); a son, Beau (age 12); and a daughter, Natasha (age 4).80 As a child, Tehani attended Columbus Public Schools (now known as Columbus City Schools), and when she and her husband had children, she knew she was looking for something better for her kids.81 They lived in Reynoldsburg, a Columbus suburb, but about six years ago, she and her husband divorced. Tehani suffered a major financial setback and was evicted from her home. She and her kids became homeless and had to take an apartment in Columbus.82

The apartment was infested with bugs, the stairs were broken, and the front door did not lock properly. With drugs dealt on the block, Tehani worried for her kids’ safety.83 A small outdoor swing set for the baby was stolen from her front porch. “Who does that?” she asked.84 The unsafe housing made it hard for her to take more work opportunities because she worried about her kids getting on the bus by themselves in the morning.

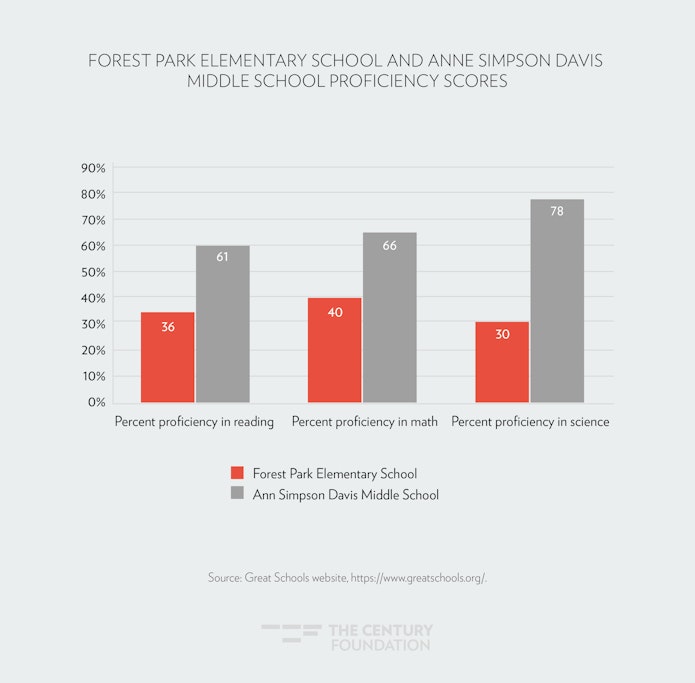

The local Columbus City public schools received low ratings on the state report card, and had low rates of proficiency. Forest Park Elementary School, located close by, for example, had 100 percent of students from low-income backgrounds and only 36 percent were proficient in reading, 40 percent in math, and 30 percent in science.85

Because Tehani had lived in suburban Reynoldsburg and because she had been homeless, her children were permitted under a provision of the federal McKinney-Vento Act to stay in Reynoldsburg public schools.86 Reynoldsburg was rated a C school district, an improvement over Columbus’s D rating. But Tehani was not entirely satisfied. In particular, she was concerned that Reynoldsburg schools did not provide her daughter Brandy, who loved choir and drama, with programs in either. “They’ve lost a lot of arts programs over in Reynoldsburg.”87 In any event, she needed a safer and better living situation than that found in Columbus.

When Tehani heard about the Move to PROSPER program, she applied at once. Through the program, she obtained housing in the Dublin school district, which received a B rating from the state of Ohio.88 Tehani’s two oldest children, Brandy and Beau, attend Ann Simpson Davis Middle School. In the school, 61 percent of students are proficient in reading 66 percent in math, and 78 percent in science (see Figure 4). There is a healthy economic and racial mix, with 38 percent of students from low-income backgrounds and no one racial group consisting of a majority.89 “It’s got everyone from minimum wage workers to those who can afford $300,000 homes,” she says.90 Tehani says her kids haven’t faced discrimination in Dublin.91

Figure 4

The school is well resourced: at the beginning of the year, she says, her kids “came home with brand new Chromebooks that they keep for the entire year.”92 Importantly, Dublin has the resources to offer the drama and choir programs that Brandy craves.

Tehani, who now works as a human resources manager at Scotts Miracle-Gro Company, marvels at the change in her life since when she and her family were homeless—the quality of the housing, the schools, the neighborhood, and even more basic things. “One of the things we don’t have to worry about is consistent housing and that’s something that’s a big deal.”93

She does worry that once the three-year Move to PROSPER program ends for her, she will be back in a precarious position. Because in central Ohio, a record of eviction stays on one’s record for several years, she may not be able to stay in a good area. “There are basically no apartment complexes that I’ve heard about” with “good living conditions that will accept [someone with] an eviction.”94

For the moment, however, she is happy. Her kids are challenged at school. And her youngest has a small swing set outside which sits undisturbed. “It makes a big difference,” she says.95

Janet Williams

Janet Williams, a 29-year-old single mother who is African American, has two children: Christopher (age 7) and Shannon (age 5).96 Unlike Cornelius and Tehani, Williams was not admitted to Move to PROSPER because of resource constraints, making her one of the more than 290 mothers who wanted but were denied the benefits of the program. Like Cornelius and Tehani, she is passionate about finding a better neighborhood and school for her children.

Williams grew up on the North and West side of Columbus as the youngest, and the only girl, in a large family. She has five brothers, one half-brother, and four step brothers.97 After graduating from Groveport Madison Ohio Public Schools, she attended community college and then earned a bachelor’s degree in human services from Ohio Christian University in 2019. Seven years ago, her son, Christopher was born, and soon after, she gave birth to her daughter Shannon. Today, Williams works as a community mental health worker and substance abuse case manager for a private nonprofit social service agency.98

With two kids, a single income, and loans from college, Williams says she has struggled economically. She lives on the East side of Columbus in a neighborhood that has a fair amount of police activity and she often has trouble making rent. “I’ve never been homeless,” she says, but she is often “behind on my rent.” She says it’s gotten “to the point where I had to choose if I wanted to pay for groceries or if I wanted to pay rent or if I wanted to pay for my gas and electric or…to pay childcare.”99

Williams says the drugs and crime in her East Columbus neighborhood make her worry about her children’s safety. “I can’t tell you how many times we’ve seen the police outside of our window,” she says. To avoid dangers in the neighborhood, she says, “we pretty much keep to ourselves. We don’t really do too much.” She continues, “There is no traffic in and out of my house.”100

Because the boundaries of the Columbus City Schools district are not coterminous with the City of Columbus borders, Williams lives in Columbus, but is districted for Whitehall City Schools.101 Christopher and Shannon attend Kae Avenue Elementary, which serves Kindergarten and first grade. Williams says she likes the teachers and the other parents, but she is not sure what to expect when the children move on to Beechwood Elementary in second grade.102

The data suggest that Beechwood, which Christopher will attend next year, is low performing. In a school where 78 percent of students are low-income, just 37 percent of students are proficient in reading, 30 percent in math, and 47 percent in science. The school receives an overall Great Schools rating of 2 out of 10.103 Whitehall City Public Schools as a whole received a D on the Ohio Education Department’s report card, just like Columbus City Schools.104

Williams says she applied to Move To PROSPER for three reasons: to receive financial literacy and counseling; to gain access to better neighborhoods like those in Gahanna (where Move to PROSPER participant KiAra Cornelius lives); and to obtain access to strong schools for her kids.

Financially, she said she hoped the program would “help me get back on track and get back on my feet.”105 Moreover, when Williams read that Move to PROSPER places people in Gahanna, she said that it “caught my eye.” She has spent some time visiting Gahanna as part of her work and says “it’s a really nice place.” She continues: “People out there are very hopeful and it just seems like a really great neighborhood for kids to be in. And the schools are amazing out there.” She thought, “Wow, like I could get into the Gahanna area.”106

Compared to her crime-ridden neighborhood in Columbus, she says she would be “more at ease” in Gahanna. It would be nice to think of “being at ease with the overall neighborhood.”107

Moreover, Gahanna schools are much higher performing than Whitehall schools. The district receives a B, compared to Whitehall’s D, and local elementary schools are much higher performing.108 For example, at Lincoln Elementary School, where 21 percent of students are low-income, 75 percent of students are proficient in reading, 74 percent in math and 85 percent in science and the school received a rating of 6. At Royal Manor Elementary, likewise, where 48 percent of students are low income, 70 percent of students are proficient in reading, 77 percent in math, and 76 percent in science and the school receives a 7 rating.109

Williams is not bitter about being shut out of Moving to PROSPER, but she hopes she can participate at some point in the future. Her kids are growing up fast, and they only have one childhood.

Looking to the Future

The stories of KiAra Cornelius, Tehani, and Janet Williams remind us that no matter one’s income, race or ethnicity, parents almost always want the best for their kids. This simple message runs counter to an unfortunate myth in Columbus and elsewhere that poor people don’t have the same ambitions for their kids as others. As the Columbus Urban League’s Executive Director Frank Lomax characterized it years ago, there is a false belief that poor and Black residents “are satisfied with mediocrity.”110

Low-income families know the score: they are more likely to rate their local public schools as “bad” than other families do.111 Low-income families are about twice as likely as wealthier families to worry frequently about their kids’ safety in school.112 And while African Americans strongly value community, 69 percent in one poll of Long Island residents preferred integrated neighborhoods, while just 1 percent wanted to live in all-Black neighborhoods.113

The mothers who applied to Move to PROSPER knew their kids might face discrimination in the suburbs, but they were willing to make that difficult choice because they knew that the high poverty schools available to them in Columbus weren’t providing the opportunities they wanted. They also desired neighborhoods where their kids would be safe to play outside and walk around without fear.

The evidence suggests it was not lack of ambition that kept these families out of high-opportunity suburbs; it was barriers, imposed by government, that artificially limited affordable housing opportunities. When given the chance to move to these neighborhoods by a nonprofit program, applications from low-income families flooded in. Ten fortunate families got the opportunity to live in safe neighborhoods with great schools and saw their prospects increase, according to Century Foundation interviews—and according to two Ohio State University evaluations of the Move to PROSPER program.114

But the program is very small, and even for the beneficiaries, it is temporary—due to expire in 2021.115 It was designed as a three-year pilot; “this is not forever,” says Klaben.116 Move to PROSPER is trying to raise funds to expand the program to 100 families, which could greatly benefit the lives of recipients.117 But on a parallel track, efforts should be made to enact public policies that will remove barriers to families wanting to relocate to high opportunity neighborhoods.

The typical policy response is small bore, stop gap measures—such as private school vouchers and high-poverty charter schools—but as was the case of parents in this report, those efforts are often unsatisfying, and do nothing to improve neighborhoods that children grow up in.

More promising is the systemic change that imaginative policymakers are beginning to enact. Just as lawmakers and courts fought racial discrimination in housing in the twentieth century—with the 1948 Shelley v. Kraemer decision striking down racially restrictive covenants and passage of the 1968 Fair Housing Act outlawing racial discrimination in the sale and rental of housing, it is now time, in this century, to outlaw blatant income discrimination.118 Several states and localities have enacted “source of income discrimination” laws that prevent landlords from refusing to accept Section 8 housing vouchers.119 And in 2019, the city of Minneapolis, and the state or Oregon, both took on the sacred cow of single-family zoning laws as discriminatory. In Minneapolis, where 70 percent of residential land had been reserved for single-family homes, legislation was enacted to open up the opportunity to build more affordable duplexes and triplexes. Oregon likewise passed a statewide ban on single-family zoning in cities with populations of at least 10,000 residents.120

At the same time, it is time to invest in cities and provide more opportunities to draw middle-class families into urban areas so that movement is a two-way street. Historically, Columbus had a system of “alternative schools” with long waiting lists, which were considered the “jewels of the system.”121 To this day, Columbus Alternative High School is rated the number one magnet school in the state of Ohio.122 In places like Hartford, Connecticut, too, there are long waiting lists of suburban families who want their children to attend high quality integrated magnet schools.

In some parts of Columbus, middle-class families are returning to the city, but this remains the exception to the rule. According to a March 2018 study of the National Community Reinvestment Coalition, there is enormous overlap between the Columbus areas redlined in the 1930s and the demographics of communities today. The report found 82 percent of Columbus’s redlined neighborhoods remained low-to-moderate income, while 89 percent of neighborhoods that were designated as the “best” investments in the 1930s are middle-to-upper income and overwhelmingly white today.123

KiAra Cornelius, Tehani, and Janet Williams want the best for their kids. Thousands of mothers want the same thing. It is time to tear down the walls that divide us.

Notes

- KiAra Cornelius interview with Michelle Burris and Richard Kahlenberg, February 12, 2020, 5.

- Tehani interview with Michelle Burris and Richard Kahlenberg, February 10, 2020, 5. Tehani requested that the report use only first names for her and her children.

- Ohio School Report Cards, “Columbus City School District,” https://reportcard.education.ohio.gov/district/overview/043802.

- These districts received overall grades of A and B. See Ohio State Report Cards, “Dublin City” (2020), https://reportcard.education.ohio.gov/district/overview/047027; “Hilliard City” (2020), https://reportcard.education.ohio.gov/district/overview/047019; “Gahanna–Jefferson City” (2020), https://reportcard.education.ohio.gov/district/overview/046961; and “Olentangy Local” (2020), https://reportcard.education.ohio.gov/district/overview/046763.

- Joel Oliphint, “Move to Prosper’s forgotten families,” Columbus Alive, May 15, 2019.

- Janet Williams is a pseudonym employed at the request of the individual interviewed. The report also uses pseudonyms for her children.

- Gregory S. Jacobs, Getting Around Brown: Desegregation, Development, and the Columbus Public Schools (Columbus: Ohio State University Press, 1998), 5–6, 67–68.

- Ohio Demographics, “Ohio Cities by Population,” https://www.ohio-demographics.com/cities_by_population.

- Richard Florida, “America’s Most Economically Segregated Cities,” CityLab, February 23, 2015, https://www.citylab.com/life/2015/02/americas-most-economically-segregated-cities/385709/. Large metro regions were those with more than 1 million people.

- Raj Chetty, Nathaniel Hendren, Patrick Kline, and Emmanuel Saez, “Economic Opportunity: State of States,” The Stanford Center on Poverty and Inequality, 2015, 59, Table 1, https://inequality.stanford.edu/sites/default/files/SOTU_2015_economic-mobility.pdf.

- Chetty et al., “Economic Opportunity: State of States,” 59.

- William Griffin, African Americans and the Color Line in Ohio, 1915–1930 (Columbus: Ohio State University Press, 2005), 9.

- Frank Quillin, The Color Line in Ohio (1913), cited in Joel Oliphint, “The roots of Columbus’ ongoing color divide,” Columbus Alive, June 27, 2018.

- Patricia Burgess, Planning for the Private Interest: Land Use Controls and Residential Patterns in Columbus, Ohio 1900–1970 (Columbus: Ohio State University Press, 1994), 45. See also Jason Reece, quoted in Oliphint, “The roots.”

- Oliphint, “The roots.”

- Richard Rothstein, The Color of Law: A Forgotten History of How Our Government Segregated America (New York: Liveright Publishing Corp/W. W. Norton, 2017), 76.

- Penick v. Columbus Board of Education, 429 F. Supp. 229, 237 and 258 (S.D. Ohio, 1977) (Columbus segregation levels); and John R. Logan and Brian J. Stults, “The persistence of Segregation in the Metropolis: New Findings from the 2010 Census,” census brief prepared for Russell Sage Foundation US2010 project, March 24, 2011, http://www.s4.brown.edu/us2010/Data/Report/report2.pdf (national 1970 dissimilarity index).

- Jacobs, Getting Around Brown, 52.

- Penick, 429 F. Supp. 235–42.

- Penick, 429 F. Supp. 240

- Penick, 429 F. Supp. 259.

- Jacobs, Getting Around Brown, 96.

- Jacobs, Getting Around Brown,76 and 113.

- Jacobs, Getting Around Brown, 120.

- Jacobs, Getting Around Brown, 166. See also Jacobs, xiii.

- Jacobs, Getting Around Brown, 139, 165, 197. See also Jacobs, 129.

- Jacobs, Getting Around Brown, 197. See also Jacobs, xiii, 121, 130, 132.

- Jacobs, Getting Around Brown, 157–59.

- Jacobs, Getting Around Brown, 135, 141, 155, 174m 191.

- Penick, 429 F.Supp. 237 and 240; and Great Schools, “Columbus City School District,” https://www.greatschools.org/ohio/columbus/columbus-city-school-district/.

- Oliphint, “The roots.”

- Burgess, Planning for the Private Interest, 113–14, 125.

- Burgess, Planning for the Private Interest, 1–2, 59.

- Burgess, Planning for the Private Interest, 6, 9, 198, and 203.

- See Richard D. Kahlenberg, “An Economic Fair Housing Act,” The Century Foundation, August 3, 2017, https://tcf.org/content/report/economic-fair-housing-act/.

- Jonathan Rothwell and Douglas Massey, “Density Zoning and Class Segregation in U.S. Metropolitan Areas,” Social Science Quarterly 91, no. 5 (December 2010): 1123–43, http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3632084/.

- Joel Oliphint, “Move to Prosper’s forgotten families,” Columbus Alive, May 15, 2019.

- Michael Kelley Interview, 2; Klaben interview, 11, 12; “Amy Klaben, Eds, Project Facilitator,” Move to PROSPER, https://www.movetoprosper.org/amy-klaben.

- Klaben Interview, 9, 11.

- Klaben Interview, 9.

- Oliphint, “Move to Prosper’s forgotten families”; Klaben Interview, 2, 9.

- Michael Kelley Interview, January 21, 2020, 1; Klaben Interview, 10.

- Amy Klaben Interview, January 24, 2020, 1.

- Klaben Interview, 2.

- Raj Chetty, Nathaniel Hendren, Lawrence Katz, “The Effects of Exposure to Better Neighborhoods on Children: New Evidence from the Moving to Opportunity Experiment,” NBER Working Paper 21156, May 2015, 2. The paper subsequently appeared in American Economic Review 106(4): 855-902, 2016, https://opportunityinsights.org/paper/newmto/.

- Heather Schwartz, “Housing Policy is School Policy,” in The Future of School Integration, ed. Richard D. Kahlenberg (New York: The Century Foundation Press, 2012), https://tcf.org/content/report/housing-policy-school-policy-economically-integrative-housing-promotes-academic-success-montgomery-county-maryland/.

- Schwartz, “Housing Policy is School Policy.”

- Amy Klaben, telephone interview with authors, January 24, 2020, 2.

- Mark Ferenchik, “Program to move 100 low-income Columbus families to suburban school districts,” Columbus Dispatch, May 1, 2017.

- Klaben interview, 4; Kirwan Institute, “Understanding Opportunity Mapping,” http://kirwaninstitute.osu.edu/researchandstrategicinitiatives/opportunity-communities/mapping/understanding-opportunity-mapping/.

- Oliphint, “Move to Prosper’s forgotten families”; CASTO website, https://www.castoinfo.com/our-company/our-story/.

- Oliphint, “Move to Prosper’s forgotten families.”

- Move to PROSPER, “About Our Program,” https://static1.squarespace.com/static/589c7c3ba5790a3587715ef5/t/5abb073d352f53d186e5ee89/1522206538207/M2P.programoverview.brochure.pdf.

- Klaben Interview, 6.

- Reece and Lee, “Interim Program Evaluation 1.0,” 8.

- Klaben Interview, 12, 16.

- Reece and Lee, “Interim Program Evaluation 1.0,” 11.

- Reece and Lee, “Interim Program Evaluation 1.0,” 13.

- Reece and Lee, “Interim Program Evaluation 1.0,” 21–22.

- Reece and Lee, “Interim Program Evaluation 1.0,” 18; Klaben Interview 3.

- Cornelius Interview, 2.

- Cornelius Interview, 1 and 3; KiAra Cornelius Interview with Michelle Burris and Richard Kahlenberg, April 7, 2020 (Cornelius Interview II), 1.

- Cornelius Interview II, 1–2.

- Great Schools, “Siebert Elementary School,” https://www.greatschools.org/ohio/columbus/619-Siebert-Elementary-School/.

- Cornelius Interview, 2.

- Great Schools, “Columbus Arts and Technology Academy,” https://www.greatschools.org/ohio/columbus/5947-Columbus-Arts–Technology-Academy/.

- Cornelius Interview, 1.

- Cornelius Interview, 5.

- Cornelius Interview II, 1.

- Great Schools, “Goshen Lane Elementary School,” https://www.greatschools.org/ohio/gahanna/2312-Goshen-Lane-Elementary-School/.

- Great Schools, “Gahanna South Middle School,”

https://www.greatschools.org/ohio/columbus/2307-Gahanna-South-Middle-School/. - Cornelius Interview, 5

- Cornelius Interview, 5.

- Cornelius Interview, 3.

- Cornelius Interview, 3.

- Cornelius Interview, 3-4; Great Schools, “Columbus Arts” and “Gahanna South Middle.”

- Cornelius Interview, 4.

- Cornelius Interview, 5.

- Interview, 2, 6. As noted earlier. Tehani requested that this report use only first names for her and her children.

- Tehani Interview, 8.

- Tehani Interview, 2.

- Tehani Interview, 2.

- Tehani Interview, 8.

- Great Schools, “Forest Park Elementary School,” https://www.greatschools.org/ohio/columbus/648-Forest-Park-Elementary-School/.

- Tehani Interview, 3.

- Tehani Interview, 5.

- Ohio State Department of Education, “School Report Cards: Dublin School District,” https://reportcard.education.ohio.gov/district/overview/047027.

- Tehani Interview, 4; Great Schools, “Ann Simpson Davis Middle School,” https://www.greatschools.org/ohio/dublin/2366-Ann-Simpson-Davis-Middle-School/.

- Tehani Interview, 6.

- Tehani Interview, 6.

- Tehani Interview, 7.

- Tehani Interview, 2.

- Tehani Interview, 7.

- Tehani Interview, 8.

- Janet Williams (pseudonym) Interview with Michelle Burris and Richard Kahlenberg, March 30, 2020, 1. The names of the two children are also pseudonyms.

- Williams Interview, 1.

- Williams Interview, 1.

- Williams Interview, 2.

- Williams Interview, 8.

- Williams Interview, 6.

- Williams Interview, 4-5, and 9.

- Great Schools, “Beechwood Elementary School,” https://www.greatschools.org/ohio/columbus/1662-Beechwood-Elementary-School/.

- Ohio School Report Cards, “Whitehall City,” https://reportcard.education.ohio.gov/district/overview/045070; and Ohio School Report Cards, “Columbus City Schools,” https://reportcard.education.ohio.gov/district/overview/043802.

- Williams Interview, 2.

- Williams Interview, 3, 8.

- Williams Interview, 8.

- Ohio Report Cards, “Gahanna–Jefferson City,” https://reportcard.education.ohio.gov/district/overview/046961.

- Great Schools, “Lincoln Elementary School,” https://www.greatschools.org/ohio/columbus/2314-Lincoln-Elementary-School/; and Great Schools, “Royal Manor Elementary,” https://www.greatschools.org/ohio/gahanna/2316-Royal-Manor-Elementary-School/.

- Jacobs, Getting Around Brown, 140.

- See Emily Ekins, “Poll: 58% of Americans Favor Vouchers for K–12 Private School,” Cato Institute, October 3, 2019 (25 percent of Americans generally say neighborhood public schools are “ bad,” but 37 percent of poor Americans so rate their schools),

https://www.cato.org/blog/poll-58-americans-favor-vouchers-k-12-private-school. - Jim Norman, “Low-Income Parents Worry More About Student Harm,” Gallup, November 9, 2018, https://news.gallup.com/poll/244712/low-income-parents-worry-student-harm.aspx.

- Erase Racism, “Housing and Neighborhood Preferences of African Americans on Long Island

2011 Survey Research Report,” 2012, https://www.racialequitytools.org/resourcefiles/ERASE_Racism_Housing.pdf (integrated neighborhoods were defined at 50 percent Black and 50 percent white). - See Jason Reece and Jee Young Lee, “Move to PROSPER: Interim Program Evaluation 1.0,” Ohio State University, January 2019, https://static1.squarespace.com/static/589c7c3ba5790a3587715ef5/t/5c64737ec83025c7da381a13/1550087058793/Final+MTP+Interim+Report+1.0+February+12+2019.pdf; and Jason Reece, Jee Young Lee, Natalie Kroger and Sahar Khaleel, “Move to PROSPER: Interim Program Evaluation 2.0,” Ohio State University, February 2020 (generally, and 28–36 for positive youth outcomes in particular), https://static1.squarespace.com/static/589c7c3ba5790a3587715ef5/t/5e65aab2fdb580682489a0a1/1583721151900/2020FullReportMTP.pdf.

- Cornelius Interview, 6.

- Klaben Interview, 14.

- Joel Oliphint, “Move to Prosper’s forgotten families,” Columbus Alive, May 15, 2019.

- See Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U.S. 1 (1948); and Fair Housing Act of 1968, U.S. Department of Justice, “Fair Housing Act,” https://www.justice.gov/crt/fair-housing-act-2.

- Poverty and Race Research Action Council, “Expanding Choice: Practical Strategies for Building a Successful Housing Mobility Program APPENDIX B: State, Local, and Federal Laws Barring Source-of-Income Discrimination,” May 2017, http://www.prrac.org/pdf/AppendixB.pdf.

- Richard D. Kahlenberg, “How Minneapolis Ended Single-Family Zoning,” October 24, 2019, https://tcf.org/content/report/minneapolis-ended-single-family-zoning/.

- Jacobs, Getting Beyond Brown, 154.

- Niche.com, “Columbus Alternative High School,” https://www.niche.com/k12/columbus-alternative-high-school-columbus-oh/.

- Oliphint, “The roots.”