Executive Summary

In this new report, we analyze a set of 2023–2024 online program manager (OPM) contracts obtained from twenty-nine institutions and find that institutions still choosing to partner with OPMs during a higher education climate of declining demand for online programs, decreases in the number of OPM contracts with institutions, and declining stock value of OPMs remain at risk for harm to themselves and their students. OPMs are highly underregulated, and the contracts reviewed contain a variety of unchecked, high-risk elements that compromise students and institutions, such as high rates of tuition sharing, lengthy and sometimes indefinite contract terms, and profit-driven recruitment.

Most of the contracts reviewed used tuition-sharing agreements, in which institutions shared up to 50 percent of tuition with the OPMs for each student they recruited into the OPM-managed online programs: some institutions shared as much as 82 percent of total tuition with the OPM. These tuition-sharing practices put students at risk for inflated tuition.

The contracts reviewed often use lengthy contract terms—some up to ten or fifteen years, and several with indefinite terms. Indefinite terms often contain clauses allowing either party to end the contract at any time, leaving institutions at risk of an abrupt loss of access to online programming resources. Moreover, the contracts reviewed show that OPM recruitment services prioritize the well-being of the OPM, often at risk to institutions and students. In some cases, OPMs retain the right to use a prospective student’s information to market not only the online program a student is interested in at the OPM’s partner institution, but also to the online programs the OPM runs at different institutions. OPM recruiters also engage in profit-driven recruitment, wherein they focus on securing enrollment revenue no matter the fitness of the program for the student or vice versa. A non-profit is required, by contrast, to engage in student-driven enrollment, which prioritizes meaningfully matching prospective students with the educational offerings.

Steps can be taken to protect students and institutions at the federal, state, and institution levels. While federal protections, such as prohibiting tuition-sharing for recruitment and oversight of OPM–institution relationships, are currently absent, states can and should adopt state-level protections, such as those adopted by Minnesota, that prohibit tuition-sharing for recruitment and include oversight of OPM contracts. Moreover, institutions, regardless of their state, have the power to protect themselves and their students by avoiding tuition-sharing agreements and instead using fee-for-service agreements, avoiding lengthy or indefinite contract terms, requiring their OPMs to use transparent and student-centered recruitment practices, retaining control over key decision-making processes, and, when a university system is involved, implementing system-wide OPM guidance to protect all of their member institutions.

Introduction

Fifteen years ago, when enrollment in in-person degree programs began to decline and demand for online degree programs began to rise, brick-and-mortar colleges across the nation eagerly looked for ways to remain competitive in the higher education space by offering online degree programs of their own. To do this, institutions began to contract with online program managers (OPMs).

OPMs are for-profit companies that enter into contractual arrangements with public and nonprofit institutions to offer a range of services related to facilitating online educational offerings, such as providing online degree programs and marketing and recruiting students into the very programs they create.1 These contractual relationships often pose significant risks for the contracting institution as well as for students. First, through these arrangements, institutions agree to contract out the creation and delivery of degree programs—tasks intended to be a core function of the institution—and often in a way that is not transparent to students. Second, by contracting with for-profit entities, public and nonprofit institutions introduce a profit motive into what should be a nonprofit, student-driven decision-making ecosystem.

It is when marketing and recruiting services are offered that OPMs tend to raise concerns. For example, in some cases, institutions enter into tuition-sharing agreements with OPMs, in which the institution pays the OPM a cut of the tuition for each student they successfully recruit into the online program. This form of incentive-based compensation creates room for the aggressive and predatory recruitment of students. Third, when signing on the dotted line with OPMs, institutions often agree to a wide range of contract terms that can cede large amounts of power to these third-party providers.

Five years ago, The Century Foundation (TCF) published an in-depth report examining over one hundred contracts, collected from 2019 through 2020, between public and nonprofit colleges and OPMs.2 In that report, TCF uncovered the presence of several contract elements that put students, institutions, and taxpayers at risk. That report urged institutions to take action to protect themselves when contracting with OPMs by avoiding high-risk terms, including lengthy contracts, arrangements that provided a portion of tuition to OPMs, and arrangements that involve aggressive recruiting.

In the time since the release of that report, OPMs have faced a series of allegations of misconduct, lawsuits, and, in some cases, financial decline. The OPM 2U and its partner institution the University of Southern California (USC) were sued for engaging in deceptive enrollment practices that allegedly included using misleading rankings data to entice students to enroll in their online master of social work (MSW) program3 and allegedly misrepresented their program as being equivalent to the in-person MSW program.4 Additionally, as was recently reported in the New York Times, the California Institute of Technology (CalTech) and the OPM Simplilearn are facing a lawsuit for violating California consumer protection laws based on allegations that Simplilearn misled students by offering online bootcamps that used the CalTech name but were not taught or operated by CalTech staff.5

OPMs have experienced declining demand for their online programs,6 a decrease in the number of contracts with institutions,7 and declining stock value,8 and some have even filed for bankruptcy.9 But in spite of this public unraveling, and of the risks these trends create for students in programs run by OPMs, some OPMs have broadcast plans to continue to grow, expand, and continue to work with students and institutions in the higher education space.10

The persistence of OPMs in the higher education landscape, in spite of the continued risks they pose to students and institutions, means that there will continue to be a need for analysis of OPM arrangements and action to strengthen oversight of OPM activity.

In this report, we bring TCF’s leading research on the issue up to date by analyzing OPM contracts from twenty-nine institutions, collected between 2023 and 2024. While recent media coverage points to evidence that the prevalence of OPM contracts is declining, our analysis finds that institutions with active OPM contracts are still at risk for harm. We analyze these risks, namely tuition-sharing, lengthy and indefinite contract terms, and provisions for aggressive marketing and recruiting. We end this report by highlighting the federal, state, and institution-level actions that can be taken to increase oversight and accountability and protect students and taxpayers from the harms that can arise when institutions contract with OPMs.

Unless otherwise noted, contract details cited come from the contracts TCF acquired during 2023 and 2024 and analyzed by the author.

Data Collection and Sample

For this report, we collected and analyzed OPM contracts from 2023 and 2024 and from twenty-nine institutions.11 We collected contracts from institutions not previously sampled, and new contracts from some of the institutions sampled in our prior report in order to assess any changes, addenda, or amendments that have taken place since our 2019 contract analyses. Our sampling strategy also included a goal of having a representation of a variety of schools of different sizes types and from a diverse group of states. As detailed below in Table 1, our sample includes approximately seven small- and mid-sized schools, twenty-two large schools, and institutions from eighteen states. Additionally, nineteen contracts are from institutions we previously sampled and analyzed during TCF’s 2019–2020 contract collection, while ten are new.

| Table 1. Institution and Contract Characteristics | |

| Institution Size | |

| Small institutions | 2 |

| Mid-sized institutions | 5 |

| Large institutions | 22 |

| Institution Location | |

| Total states represented | 18 |

| Institution, Repeat or New | |

| Institutions sampled in previous study | 19 |

| New institutions sampled | 10 |

| Total institutions | 29 |

| Source: Author’s analysis of OPM–institution contracts obtained between 2023 and 2024.

Note: We define institution size as follows: small = less than 5,000 students; medium = 5,000–15,000 students; large = more than 15,000 students. |

|

The process of collecting OPM contracts is a time-consuming and involved one. While some institutions respond quickly and share contracts readily, other institutions take time to reply, charge high fees to gather and release contracts, deny requests for contracts, or redact key contract information from shared contracts. In spite of these processes, we successfully collected a broad sample of recent OPM contracts for the analysis. See Appendix B for further discussion.

Findings: OPMs Are Underregulated and High-Risk Contract Elements Remain Unchecked

Despite the ongoing risks they pose for both students and institutions, OPMs continue to be highly underregulated.12 In fact, the U.S. Department of Education (ED) does not know how many students are enrolled in OPM-operated programs, or even which schools have contracts with OPMs, as these data are not collected at the federal level by data sites run by ED.13 Moreover, the department does not review or collect institutions’ contracts with OPMs. Perhaps unsurprisingly, then, the contracts between OPMs and institutions often contain a variety of unchecked, high-risk elements that compromise students and institutions, such as lengthy contract terms, commitments to sharing high percentages of tuition, and provisions that outsource key decision-making power to OPMs.14

Contracts between OPMs and institutions often contain a variety of unchecked, high-risk elements that compromise students and institutions.

Indeed, under the Biden administration, the Department of Education failed to take key actions that would have increased regulation and oversight of OPMs and protections for students. First, the department failed to extend third-party servicer guidance (TPS) to OPMs. This guidance would have required institutions to report their arrangements with OPMs to the department, made OPMs subject to annual audits, and established that OPMs and institutions are jointly liable to the department for any misconduct.15 Additionally, ED failed to rescind the 2011 bundled services guidance.16 Doing so would have restored the Higher Education Act, which prohibits institutions from providing incentive compensation to third-party providers who provide recruitment services. It is when OPMs are financially incentivized to recruit students that they are likely to engage in aggressive and predatory recruitment practices.

Without adequate federal oversight, OPMs have continued to operate with few checks. Because of this, contracts containing high-risk elements have proliferated.

High-Risk Contract Elements: Tuition-Sharing

Tuition-sharing agreements create high risk for students and institutions.17 Student advocates have cautioned institutions against entering into OPM contracts that provide for tuition-sharing.18 Tuition-sharing agreements work such that the OPM is paid by receiving a cut of tuition for each student they recruit into the online program they facilitate. These payment structures are appealing to some institutions because they mitigate the institution’s financial risk. For example, the institution does not pay for the start-up costs associated with running an online program, and if the program does not get off the ground, the university does not lose out. On the flip side, when an OPM is providing recruiting services, these payment structures create significant risks of harm for students.19 The OPM fronts the money to start up the online program and agrees to be paid back on an ongoing basis by collecting a percentage of tuition per head they recruit into the program. With money on the line, tuition-sharing payment structures have incentivized OPMs to engage in aggressive20 and predatory recruitment practices in an effort to both repay themselves and turn a high profit from providing online services to the institution.21 Put another way, under tuition-share agreements, OPMs are incentivized to recruit students into their programs without regard for students’ ability to be successful in the program and instead with a focus on increasing profits. Given that under tuition-sharing agreements OPMs’ pay is based on receiving a percentage of tuition, these agreements can lead to increased tuition prices for students.22

While tuition-sharing is the most common payment arrangement, some OPMs have shifted to offering a-la-carte fee-for-service structures.23 In fee-for-service models, institutions pay up-front for the services they want to receive from the OPM. This payment structure requires institutions to pay higher costs at the beginning of the arrangement, which may be challenging for some schools. However, it also avoids creating an incentive for predatory recruiting, thereby protecting students from aggressive and predatory recruitment practices. It may also help keep tuition costs down for students.

However, in a majority of the OPM contracts examined in this analysis, tuition-sharing is still used. The tuition-sharing rates in these data range from 30 percent to a whopping 82 percent. These high rates of tuition-sharing should create serious concern. For example, if the OPM is reliant on tuition in order to be repaid, and the tuition-share rate is high, this arrangement is likely to lead to the predatory recruitment of prospective students and inflated tuition costs for enrolled students.

In one example, a contract between Academic Partnerships (AP) and Southeastern Oklahoma University, all programs added in their most recent addendum (Addendum G), signed in 2023, use a tuition-share rate of 50 percent. While some OPM contracts agree to offer services for different levels and types of programs at different rates of tuition-share, this contract features the addition of undergraduate programs, graduate programs, certificates, and even programs without a set start date, all locked in at the same tuition-sharing rate of 50 percent. This could simply indicate that the OPM plans to operate each program in the same way, devoting the same energy, amount, and types of resources to each individual program added; but, unfortunately, the details of the OPM’s commitments to individual programs are not defined in the contract terms.

In a recent conversation with the author, a university official involved in the online program division of their institution shared concerns about their institution’s current tuition-sharing agreement with an OPM. The university official noted that the OPM was not devoting the same level of resources, time, or attention to each of the programs they are contracted to provide for the institution, leading some programs to face underenrollment. When the official raised concerns to the OPM that some of the contracted programs were being under-served, the OPM defended its practices, asserting that devoting different levels of resources to marketing each program was consistent with “industry standards” for tuition-sharing agreements. The institution is currently in talks with the OPM to renew their contract with increased tuition-sharing levels. This example illustrates the precarity institutions can face when using payment structures dependent upon tuition dollars.

High-Risk Contract Elements: Lengthy Contract Terms

One significant concern raised by advocates in the online higher education space is that when institutions contract with OPMs, they often agree to lengthy contract terms, sometimes with auto-renewal clauses. Such terms can keep institutions trapped in expensive contracts.24 Institutions need the flexibility to make changes and adapt in order to serve the needs of their students. Indeed, for many institutions, OPM usage may work best as a start-up support, and not as a permanent management solution. But lengthy contract terms can leave institutions without many options to exit contractual relationships that may no longer be serving the institution or its students.

The Century Foundation has previously noted,25 for example, that term lengths of ten years can be risky, and those with indefinite terms can be extremely risky. In the set of OPM contracts we analyzed for this report, we continue to observe lengthy contract terms between OPMs and institutions of higher education. As seen below in Table 2, ten of the twenty-nine schools represented in our sample had ten-year contracts, fifteen-year contracts, or contracts with indefinite terms.

| Table 2. OPM Contracts with Lengthy Terms | ||||

| Institution Name | Online Provider Name | Institution Size | Year Contract Began | Contract Term Length in Years |

| Emporia State University | Academic Partnerships | Medium | 2017 | 10, with a 1-year auto-renewal |

| Michigan State University | Coursera | Large | 2015 | Indefinite |

| Southeastern Oklahoma State University | Ed2Go | Small | 2022 | Indefinite |

| UC Berkeley | 2U | Large | 2013 | 15 |

| UNC Chapel Hill | 2U | Large | 2020 | 10 |

| University of Central Florida | Ed2Go | Large | 2017 | Indefinite |

| University of Connecticut | Trilogy | Large | 2019 | Indefinite |

| University of Kansas | Everspring | Large | 2013 | 10, with a 2-year auto-renewal |

| University of Nevada Reno | Pearson | Large | 2018 | 10 |

| Youngstown State University | Academic Partnerships | Medium | 2018 | 8 with a 5-year mutually agreed renewal, then converted to indefinite |

| Source: Author’s analysis of OPM–institution contracts obtained between 2023 and 2024.

Note: We define institution size as follows: small = less than 5,000 students; medium = 5,000–15,000 students; large = more than 15,000 students. |

||||

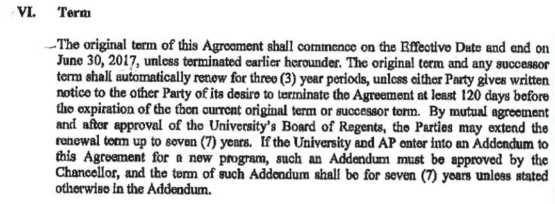

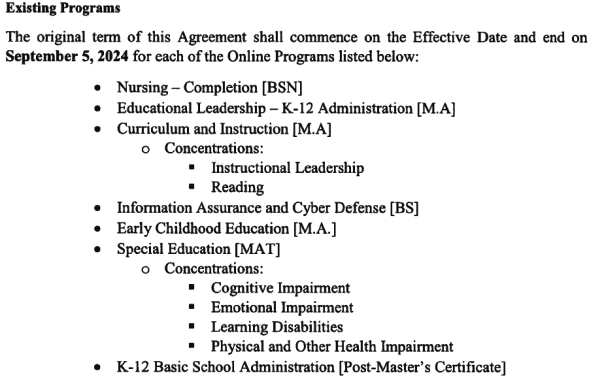

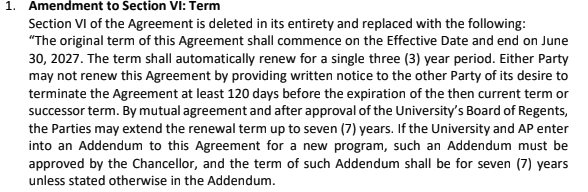

In some cases, institutions which continually renew their agreements with an OPM end up finding themselves in increasingly longer contract terms. One example of this is a contract between AP and Lamar University, which originally began as a three-year agreement in 2014,26 and used a 30-percent tuition share for undergraduate programs and a 50-percent tuition-share for graduate programs. The new contracts TCF acquired for the present study show that Lamar University entered into its fourth amendment with Academic Partnerships (AP) in 2020. This update was effective for seven years and would automatically renew for three additional years, effectively making it a ten-year contract. One could argue that the increased term length may signal a strong partnership for both parties. After all, why would an institution continue to partner with a third-party vendor if the relationship was not beneficial? However, the amendment also adds about thirty new programs to the contract term and notes that all undergraduate programs are now charged at 40-percent tuition share, and graduate programs are now charged at 50-percent tuition share. The increased term lengths coupled with increased charges to Lamar seem to suggest an increasingly extractive relationship that may be more beneficial for AP than it is for Lamar.

Figure 1: Term from 2014 Contract between Lamar University and Academic Partnerships

Figure 2: Term from 2020 Amendment between Lamar University and Academic Partnerships

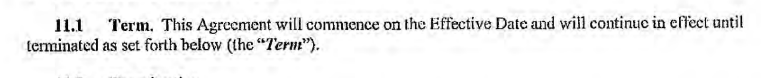

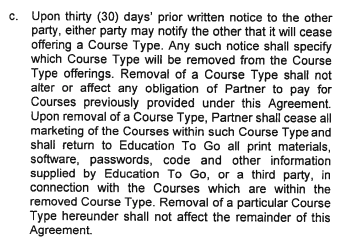

We also find examples of contracts with indefinite term lengths. These can be risky for a different reason: the OPM could cancel at any time, leaving the institution without services. In one example, Michigan State University’s arrangement with Coursera does not set a term limit to end the contract. Rather, the contract will continue until terminated. Each party can terminate the agreement with cause (e.g., breach of contract, material damage, etc.,) at any time, or without cause with ninety days’ written notice.

Figure 3: Indefinite Term Length, 2015 Contract between Michigan State University and Coursera

Figure 4: Indefinite Term Length, 2022 Contract between Southeastern Oklahoma State University and Ed2Go

While this provides the ability for the institution to opt out at virtually any time, it also provides the same privilege to the OPM. Thus, undefined terms like these could potentially leave the institution with an abrupt loss of access to online programming resources, making indefinite term lengths the riskiest term lengths of all.

Undefined terms like these could potentially leave the institution with an abrupt loss of access to online programming resources, making indefinite term lengths the riskiest term lengths of all.

High-Risk Contract Elements: Aggressive Marketing and Recruiting

OPMs originated with the intention of providing and delivering online education services to institutions, but many now focus a bulk of their efforts on providing marketing and recruitment to enroll students in online programs rather than on facilitating the programs themselves.27 This shift in the OPM market is directly related to tuition-sharing agreements. When an institution and an OPM enter a tuition-share agreement, the OPM’s financial success becomes dependent on the amount of students it recruits into the contracted program.

As OPMs have moved to focus their energy on recruitment, they have engaged in a series of behaviors that have harmed students. OPMs have engaged in aggressive recruiting practices,28 as well as in predatory recruitment of Black, low-income, and veteran students.29 They have been alleged to use misleading30 and deceptive advertising to lure students into programs.31 They have also failed to be transparent about their for-profit, external role,32 instead leading students to believe that they are preparing to enroll in an online program run solely by the institution whose name will go on their degree, or that they are speaking with recruiters or admissions counselors employed by the institution and operating on the same non-for-profit basis.

In practice, scenarios like this can often occur: a student may be searching for an online degree program, come across a website about getting an online degree from a well-known institution, and be attracted to the possibility of accessing high-quality education and earning a degree from this institution from the comfort of their home. They proceed to fill out their name and contact information in an effort to learn more about the program, and then unknowingly enter themselves into a list of names that can be contacted repeatedly by a recruiter beholden only to the OPM’s bottom line.

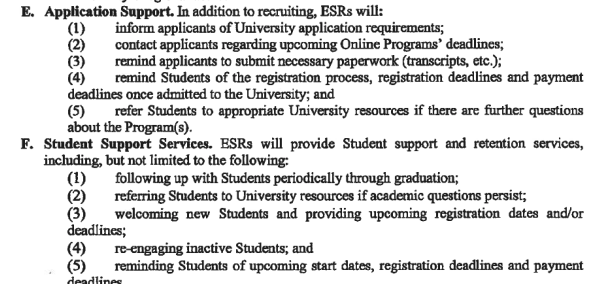

OPM contracts also contain provisions around the scope of work for recruiters, who are in some cases referred to as enrollment specialist representatives (ESRs). The title itself signals that the primary function of an ESR is to get students to enroll in the program; in practice, the ESR also typically becomes the primary point of contact for all prospective students. Key tasks, as described below in Figure 5, include application support and student support services, and their functions are characterized using sales-focused language—“contact,” “remind,” “follow up,” “reengage.” Notably, while the ESR is the main point of contact for prospective students, we have not seen contracts requiring them to inform students about the degree program, nor training them to assess whether the applicant is a good fit for or would benefit from the program.

Figure 5. Excerpt from Eastern Michigan University 2016 Contract with Academic Partnerships, Detailing Role of Recruiter

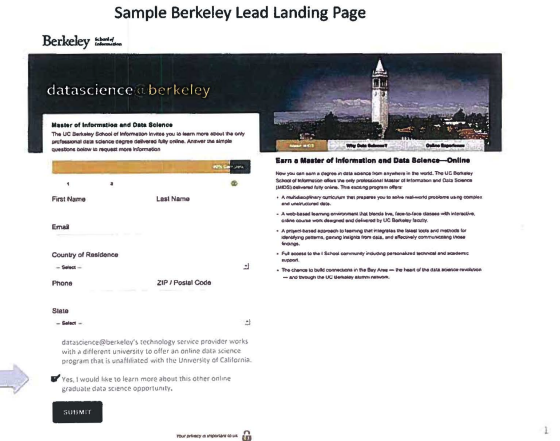

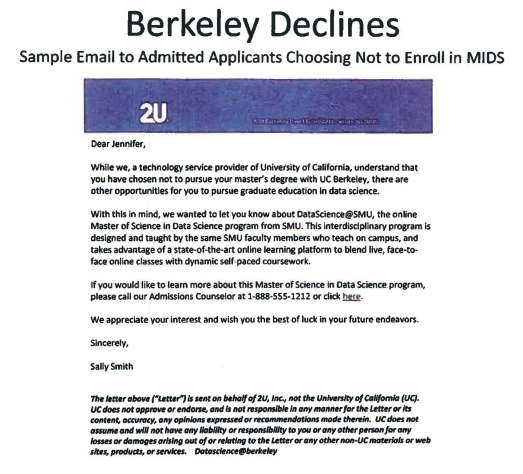

While the role of a recruiter is to enroll prospective students into an online program at the institution, in some cases, contract terms allow the OPMs to use leads generated via an institution’s online program page to recruit students into the online programs for which the OPM has been contracted at other universities. In the images below, exhibits from a contract between 2U and UC Berkeley detail how 2U is authorized to use information retained from prospective students in UC Berkeley’s online master in data science program to contact them with information about a different online program at one of their other partner schools.

Figure 6: UC Berkeley Master in Data Science Landing Page, with Option to Learn More about Non-UC Berkeley Online Program

Figure 7. 2U Email to Denied Berkely Applicant with Information about 2U Program at Another Institution

Through this agreement, students who check a box “Yes. I would like to learn more about this other online online graduate data science opportunity” can later be contracted by 2U about the other institution’s 2U-run online program. This applies to students who submit an application to Berkeley’s online program, decline admission to Berkeley’s online program, are denied admission, or do not complete their Berkeley application.

New Trends in OPM Contracts Since 2019

In reviewing the changes between contracts we collected in 2019 and those we collected from the same schools through 2024, a few trends emerge. The first is the addition or subtraction of programs with each amendment, and the second is the addition of language that attempts to immunize OPMs from legal liability.

Several institutions that continued to partner with the same OPM have signed amendments to their contracts that either add or subtract a range of online program offerings. A commonly observed example of program additions in this sample of OPM contracts is that—such as with Emporia State University, which added seven new programs in 2022—all are paid at 50-percent tuition share. In another example, Lamar University added about thirty new programs with AP, all at 40- or 50-percent tuition share. Another trend observed in the contracts among those who continued to renew or amend their OPM agreements was the increasing rate of tuition-share from the initial contract term to the amended contract term.

Conversely, some of the contracts in our sample showed the removal of programs. Previously, Eastern Michigan University and AP signed addenda adding more programs at both the graduate and undergraduate level, all at 50-percent tuition share in 2018. However, in 2020, they signed a second amendment seemingly closing at least seven programs by September of 2024. This is unsurprising, given recent reports that over one hundred OPM contracts were terminated in 2023 (see Figure 8).33

Figure 8. Eastern Michigan University and AP Move to End Online Programs in an Amendment Signed in 2020

A second trend seen in the more recent contracts is the addition of language that attempts to immunize OPMs from legal liability by referencing existing federal regulations or potential changes to federal regulations. One clear example of this appears in a contract between UNC Wilmington and AP that explicitly states that AP is not a “third party servicer” pursuant to federal regulations, except to the extent that the Department of Education “has provided or will provide guidance” that a service provided by AP places AP within the department’s definition. This addition to the contract, signed in April 2023, coincides with the timing of the Department of Education’s Dear Colleague Letter in February 2023, which originally aimed to extend third-party servicer requirements to a range of third-party servicers, and potentially to OPMs.34

Figure 9. AP Stipulates in UNC Wilmington 2023 Contract That It Is Not a Third-Party Servicer

Are OPM Contracts More or Less Risky at Smaller Colleges?

In the OPM space, there has been a suggestion that smaller institutions need OPMs more than larger institutions because smaller schools lack the infrastructure or capacity to build up and operate their own online programs. Indeed, at an ed tech conference in Washington, D.C. in Spring of 2024,35 online ed tech representatives identified this as a need that smaller schools have in their talking points.

The suggested reliance of small schools on OPMs warrants an examination of whether there are any differences in the nature of contracts between OPMs and smaller and mid-sized schools relative to those at larger schools. To illustrate this, we examined contracts between Academic Partnerships (AP) and a range of institution sizes as a case study. Table 3 below shows term lengths for a sample of current contracts between AP and ten institutions of various sizes.

| Table 3. AP Contract Term Lengths for Schools of Various Sizes | ||||

| Institution Name | Online Provider Name | Institution Size | Small, medium, large | Term Length in Years |

| Boise State University | Academic Partnerships | Around 26,000 | Large | 5, with a 3-year auto renewal |

| Eastern Michigan University | Academic Partnerships | Around 4,000 | Small | 5, with a 2-year auto-renewal |

| Emporia State University | Academic Partnerships | Around 5,300 | Medium | 10, with a 1-year auto-renewal |

| Lamar University | Academic Partnerships | Around 16,000 | Large | 7, with a 3-year auto-renewal |

| Louisiana State University | Academic Partnerships | Around 37,000 | Large | 3 |

| Louisiana State University- Shreveport | Academic Partnerships | Around 8,700 | Medium | 3 |

| Southeastern Oklahoma State University | Academic Partnerships | Around 5,000 | Small | 7, with a 5-year auto-renewal |

| SUNY Binghamton | Academic Partnerships | Around 18,000 | Large | 5, with two 3-year auto-renewals |

| UNC Wilmington | Academic Partnerships | Around 18,000 | Large | 3 |

| University of Texas Arlington | Academic Partnerships | Around 44,000 | Large | 7 |

| Youngstown State University | Academic Partnerships | Around 11,000 | Medium | 8, with a 5-year mutual renewal that then converts to indefinite |

| Source: Author’s analysis of OPM-institution contracts obtained between 2023 and 2024.

Note: We define institution size as follows: small = less than 5,000 students; medium = 5,000-15,000 students; large = more than 15,000 students. All contracts listed in Table 3 use tuition-share agreements with the exception of University of Texas Arlington, which in addition to its tuition-share agreements, added in three programs on a fee-for credit basis in its 2020 contract with AP. LSU and LSU Shreveport Contracts began in 2013 with three-year terms. Both added several amendments and/or addendums through 2019. The contracts may have expired in 2022, based on the contracts we were provided. |

||||

We can see that while AP uses a range of contract term lengths, longer contract term lengths can be found across the board, regardless of the size of the institution. For example, a partnership with Southeastern Oklahoma State University, a small institution with a student population of about five thousand students, and one with Lamar University, a large university with a population of approximately sixteen thousand students, show similarly lengthy terms—approximately seven years, with a five-year and three-year auto-renewal, respectively. Meanwhile, Youngstown State University, a mid-sized school with approximately eleven thousand students, has an eight-year term. While the five-year renewal is not automatic, thereafter the term converts to an unspecified term length.

A notable outlier here is Emporia State University, a relatively small institution, which has the longest contract term length with AP in our sample at ten years. A more detailed examination of this contract reveals that AP and Emporia State use a 50-percent revenue-share agreement for every single program offered, including those that they added in 2022. Notably, nearly all contracts with AP listed in Table 3 had tuition-sharing agreements using rates of about 50 percent, but there are some differences, such as UNC Wilmington, a large university, which instead uses a lower 44-percent tuition share. Additionally, a recent contract between AP and UT Arlington adds in three programs on a fee-for-credit basis, whereas other programs continue with tuition-share agreements.

While we caution interpretation here given the small sample size, the contracts we have collected show some evidence that larger schools may agree to slightly less risky terms like shorter term lengths, lower tuition-share rates, or alternatives to tuition-share agreements, such as the fee-for-credit programs recently added by UT Arlington.36 However, in this sample, schools contracting with AP may be likely to experience lengthy contract terms and high rates of tuition share regardless of their size. Additional research will be required if we are to ascertain whether the claims about the special fitness of smaller institutions for OPM contracts bear out.

Different OPMs, Similar Risks

In the OPM space, much media attention has been given to one of the largest OPMs in the industry, 2U. 2U contracts with seventy institutions37 and has been subject of significant media scrutiny because of the lawsuits it has faced, from allegations about its online MSW program at USC38 and its recent bankruptcy filing.39 However, 2U is not the only actor in the space that puts students and institutions at risk: institutions should be wary of the contract type in general, and not simply of select contractors.

For instance, the New York Times recently highlighted concerns with Simplilearn, a lesser-known OPM that contracted with the highly selective college CalTech to offer online bootcamps using the CalTech name. It then allegedly proceeded to aggressively recruit students to online programs that were not in fact run by CalTech.40 The aggressive and misleading recruitment strategies detailed by Simplilearn students were not unlike those allegedly employed by 2U.

In the set of contracts analyzed for this report, the OPM HackerU charges up to 82 percent of tuition or “gross revenue” to their partner institution New Jersey Institute of Technology for programs such as cyber security and ethical hacking, and digital marketing bootcamps.41 This tuition-share rate is higher than even the often-seen 50-percent tuition-share rates. Thus, while OPMs that offer undergraduate and graduate programs are often discussed in the media, it is important to note that OPMs that offer short-term programs and bootcamps also pose risks to students and institutions via high rates of tuition-share.

In these contracts, we also found concerning contract elements from AP. For example, almost all of the tuition-share agreements with AP reviewed in this sample use 50-percent tuition-share rates; moreover, they seem to be more likely to add graduate-level programs than undergraduate programs. The use of tuition-sharing with OPMs to operate online graduate-level programs poses a concern given that graduate loans do not carry the financial caps that undergraduate loans carry, leaving more room for the possibility of inflated tuition for students.

Earlier in the report we discussed the risks associated with indefinite contract terms. Ed2Go is one OPM reviewed in this sample of contracts that uses indefinite contract lengths, in which agreements continue until terminated. While each party has the option to terminate at any time with thirty days’ written notice, the termination that results would be far from a clean break. Instead, the institution would still be required to pay what is owed for the online courses. Ed2Go also reserves the right to terminate the agreement if they determine that the institution is not offering enough Ed2Go courses.

Policy Recommendations

The OPM space has experienced a decline,42 with fewer schools partnering with OPMs to provide their online programming.43 But while some institutions have made clear that the OPMs they are contracting with are not meeting their needs,44 others continue their OPM relationships. Existing contracts, such as those reviewed here, continue to show high-risk elements for both institutions and the students enrolled in these programs. Stakeholders and policymakers can take action to protect students and taxpayers from predatory OPM contract elements at the federal, state, and institutional levels. Here are some effective measures for each level of governance.

Federal-Level Recommendations

A lack of federal guidelines for institutions contracting with OPMs has allowed for the proliferation of harms to institutions and students alike. To date, the new administration has vocalized interest in dismantling the Department of Education.45 It remains to be seen whether and how this plan will go into effect.46 Still, it is important to note that federal action is within the authority of the department. To protect students and institutions, the federal government should do the following:

1. Protect institutions and students from the harms of tuition-sharing agreements. To do this, they should move to rescind the 2011 Bundled Services Guidance and provide colleges with a timeline for institutions to come into compliance with guidance that restores the incentive compensation ban in the Higher Education Act (HEA).47 As demonstrated throughout this report, the loophole created by the Bundled Services Guidance allows institutions to use tuition-sharing agreements as a way to pay OPMs for marketing and recruitment services. This payment structure creates incentives for OPMs to recruit students not based on whether students will succeed in or benefit from their program, but instead to boost the OPM’s profits.

While traditional admissions counselors employed by institutions are trained to recruit students who will be successful in their programs, the enrollment specialists employed by OPMs are not necessarily concerned with whether the program is a good fit for the student they are recruiting. Rescinding the Bundled Services Guidance will not prohibit institutions from contracting with OPMs altogether. Rather, it will update the financing structure of the contract, such that the OPM cannot be paid via tuition-sharing agreement when the OPM performs marketing and recruiting. Institutions that contract with OPMs for services that do not include recruiting can continue to use tuition-sharing arrangements. Institutions that contract with OPMs for services that include recruiting could still use OPMs, but would have to switch to a fee-for-service payment structure.

2. Create a system of federal oversight and accountability for OPMs. To do this, the federal government can move to extend third-party servicer (TPS) requirements to OPMs. This would require institutions to report their arrangements with OPMs to the Department of Education, make OPMs subject to annual audits, and require OPMs and institutions to share joint liability to the department for any misconduct. These parameters would provide broad visibility into where, how, and to what degree OPMs are operating. The data would 1) allow for more detailed analysis of online student outcomes that could be publicized and made available for students who are considering if and where to enroll in an online degree program, and 2) create a system of accountability in which OPMs would be more likely to engage in actions in the best interest of students.

State-Level Recommendations

With the new administration’s interest in dismantling the Department of Education and instead placing the full onus of enforcement on the states,48 state-level action on OPMs will be critical for providing protections for students and institutions in the coming years. One state has taken such action. In July of 2024, Minnesota became the first state to pass legislation to protect students from predatory OPMs.49 Specifically, the law increased reporting and oversight requirements for OPMs while also prohibiting any public colleges in the state from entering into new tuition-sharing agreements with OPMs that provide recruitment and marketing services. Other states should move to enact similar legislation.

1. States should prohibit the use of tuition-sharing agreements when marketing is used. The state of Minnesota took action on this issue by prohibiting public institutions from entering into new OPM contractual arrangements that allow for tuition-sharing with OPMs that provide recruitment and marketing services. By enacting this legislation, states can provide protection from the harms associated with tuition-sharing agreements: high rates of tuition-sharing, inflated tuition for students, and aggressive and deceptive recruiting practices, all of which prioritize OPM profits over student success.

2. States should create improved oversight, increase reporting requirements, and enforce greater transparency for OPMs. Increased oversight would provide insight on the extent to which OPMs are operating in the state. Data collected from reporting requirements could be used to inform student decision-making about online programs. Reporting requirements could extend to students, such that OPMs are required to be transparent and identify themselves as third-party providers when engaging in any recruitment or marketing activities with prospective students. Combined, these state-level policies would increase state- and student-level knowledge about where OPMs operate, how students fare in those programs, and when a program is being offered by a third-party provider.

3. States should require that institutions maintain control over core decision-making. States can protect their local institutions by requiring that they maintain oversight of all marketing and recruitment materials and processes and all program decision-making, that they set enrollment targets, and that they establish admissions standards and enrollment decisions.

Institution-Level Recommendations

Whether or not federal or state governments move to take action on OPMs, institutions can and should protect themselves when contracting with third-party servicers. Ultimately, institutions have the greatest power in establishing the parameters of their agreements, because only they can decide whether to partner with an OPM, which OPM to partner with, and how to do so. Some colleges have realized that they do not want or need to give so much control to a private, third-party company in order to provide students with an online learning option,50 while others have figured out how to scale their own resources in order to provide their online programs in-house;51 what’s more, other institutions have decided to run their formerly outsourced online programs themselves.52 However, for those institutions still working with OPMs, there are important steps that can be taken to protect themselves and their students.

1. Institutions should avoid lengthy or indefinite contract terms. Institutions looking to partner with an OPM to help manage their online programs should take care to avoid lengthy contract terms. Lengthy contract agreements can leave institutions locked into arrangements that are unfavorable or leave them unable to adapt to meet the needs of their students.53 While indefinite contract terms stipulate that institutions can exit contracts at any time, these clauses also leave institutions on the hook for any outstanding fees they might owe to the OPM and require them to cease use of any program materials or technology immediately.

Ideally, contract terms should be short and finite, such that they enable OPMs to start institutions off on their online programs and then provide an exit ramp that allows them to transition to running their online programs themselves.

Ideally, contract terms should be short and finite, such that they enable OPMs to start institutions off on their online programs and then provide an exit ramp that allows them to transition to running their online programs themselves. This would allow institutions to maintain control and oversight of the education being offered to students, under the institution’s own name.

2. Institutions should enter into fee-for-service agreements when marketing is used. Institutions should avoid tuition-sharing when the OPM offers marketing or recruitment services and instead use fee-for-service agreements. Tuition-sharing agreements are associated with predatory recruitment practices that harm students, because in them, recruiters are incentivized to recruit as many students as possible without regard for a student’s fit with the program or likelihood of success. When fee-for-service agreements are used, institutions instead pay the OPM for their services up front, thereby removing the incentive compensation structure from the arrangement.

3. Institutions should require the use of transparent, student-centered recruitment for their online programs. When OPMs perform marketing and recruitment for an institution, they should be required to identify themselves as employees of the OPM and not of the institution. This transparency will allow students to understand that the online program is being delivered by a third-party provider. Recruitment into online programs should also be student-centered. Recruiters should focus on enrolling students who will benefit from the online program.

A common narrative in the online higher education space is that institutions have partnered with OPMs as a way to increase their online presence and remain competitive in the higher education space. The best advertising of all for an institution is successful students. If students who are a good fit for the program are recruited into the program and supported through it with strong instructors and support, their success will help sell the program. Institutions should ensure that any marketing or recruiting of students is targeted with students in mind.

4. Institutions should retain control over decision-making, including decisions about enrollment targets. As discussed at the top of this report, when an institution contracts with an OPM to deliver their online program, they are essentially contracting out a core function of the university—the delivery of degree programs. As such, institutions should take special care to note that contract terms protect institutional control over core decision-making processes about program requirements and enrollment targets. Students enroll with the belief that they are being educated by the institution whose name is on the online program. The online program should remain within the control of the institution.

Students enroll with the belief that they are being educated by the institution whose name is on the online program. The online program should remain within the control of the institution.

5. Institutional systems should implement systemwide guidance in arrangements with OPMs. Institutional systems should set up system wide-guidance for their member institutions that work with OPMs. In one example, the California State Auditor’s Office conducted an audit of the University of California system’s use of OPMs.54 Their audit identified several concerns with the use of OPMs across multiple UC campuses.55 The state auditor recommended that the system’s Office of the President create system-wide guidance for the system’s use of OPMs.

Other university systems should follow suit and be proactive by creating system-wide guidance on working with OPMs for their member institutions, such as prohibiting tuition-sharing arrangements and requiring transparency and disclosure of OPM involvement to students. Institutional systems can also create a centralized review of OPM contracts, in which campuses would be required to submit proposed OPM contracts for review prior to entering into the contracts.

Conclusion

In today’s increasingly online world, it is likely that online education is here to stay. As such, brick-and-mortar schools will continue to want to remain competitive by offering their own online programs. Action can and should be taken at the federal, state, and institution levels to increase the oversight and regulation of online programs to ensure that students are being well-served and put first, and not being pulled into high-cost, low-value programs.

Acknowledgments

Amber Villalobos extends a sincere thank you to Taela Dudley for her assistance with requesting OPM contracts from several institutions, and to Heather Daniels for her assistance analyzing these contracts. She also wishes to thank Carolyn Fast and Dr. Stephanie Hall for their invaluable feedback on this report.

Appendix A: OPM Contracts

See below for links to the OPM contracts reviewed for this report. A few links direct to folders with multiple PDF files. In these folders, original contract agreements are labeled as original agreements, master service agreements, or fully executed agreements. Amendments and addenda are labeled as such. Not all contracts we received during the contract request stage of this analysis are linked in this report. For questions about or access to additional files, please contact [email protected].

Boise State University and Academic Partnerships

Eastern Michigan University and Academic Partnerships

Emporia State University and Academic Partnerships

Lamar University and Academic Partnerships

Louisiana State University and Academic Partnerships

Louisiana State University-Shreveport and Academic Partnerships

Michigan State University and Coursera

Michigan State University and Wiley

Michigan State University and Bisk

New Jersey Institute of Technology and Hacker U

Ohio State University and Trilogy

Ohio University and Wiley

Purdue University and Deltak

Southeastern Oklahoma State University and Academic Partnerships

State University of New York (SUNY) Binghamton and Academic Partnerships

University of California Berkeley and 2U

University of California Riverside Extension and Trilogy

University of California San Diego Extension and Trilogy

University of Central Florida and Ed2Go

University of Central Florida and HackerUSA

University of Connecticut and Trilogy

University of Kansas and Everspring

University of Maryland Global Campus (UMGC) and Guild

University of Maryland Global Campus (UMGC) and Coursera

University of Montana and Wiley

University of Nevada Reno and Pearson

University of Nevada Reno and Coursera

University of North Carolina Chapel Hill (UNC) and 2U

University of North Carolina Wilmington and Academic Partnerships

University of Texas Arlington and Wiley

University of Texas Arlington and Academic Partnerships

University of Texas San Antonio and Trilogy

Valencia College and Guild

West Virginia University and Coursera

Youngstown State University and Academic Partnerships

Appendix B: Issues Encountered during Contract Collection

We experienced challenges in our effort to collect contracts. For example, we have been trying since July 2023 to obtain an OPM contract from UCLA. Since then, we have received an email update at least once a month stating that the review process is not complete and they will need more time to respond to the request. After several months, we followed up, asking the UCLA public records office to send us any documentation they had already collected so far, but that email went unanswered. At the time of writing this article, we continue to receive automated emails from the public records office, noting that more time will be needed to collect and share the requested contracts.

We also experienced high cost estimates for contract collection from some institutions. For example, the University of Michigan estimated $779 to complete our request for the following:

The most recently active contracts, including agreement addendums, that the University of Michigan has entered into with 2U, Academic Partnerships, All Campus, Pearson, Wiley, Noodle Partners, Trilogy, The Learning House, Bisk, Coursera, Everspring, and any other online program manager or third party for the purposes of delivering online learning services. For the purposes of this request, “delivering online learning services” encompasses the following operations: student recruitment, marketing, program development, curriculum design, and instruction.

While the majority of institutions did not charge to collect and share contracts with us, a few institutions charged anywhere from $40 dollars to $300 dollars in order to disburse the contracts. In a few cases, we received letters from legal counsel initially denying access to the requested contracts on the grounds that the contracts contained confidential or proprietary information that could allegedly compromise the trade secrets of the respective OPMs. Finally, we received some contracts with redacted information. Often, the most critical information, such as the percentage of tuition provided to the OPM, was redacted.

Notes

- Amber Villalobos, “A Quick Guide to Online Program Managers (OPMs),” The Century Foundation, October 24, 2023, https://tcf.org/content/commentary/a-quick-guide-to-online-program-managers-opms/.

- Stephanie Hall and Taela Dudley, “Dear Colleges: Take Control of Your Online Courses,” The Century Foundation, September 12, 2019, https://tcf.org/content/report/dear-colleges-take-control-online-courses/.

- Student Defense, “Students File Lawsuit Against USC and 2U for Deceptive Enrollment Scheme,” Student Defense, December 20, 2022, https://defendstudents.org/news/students-file-lawsuit-against-usc-and-2u-for-deceptive-enrollment-scheme#:~:text=Student%20Defense%20and%20Tycko%20%26%20Zavareei%20LLP%20today,Report%20rankings%20of%20the%20Rossier%20School%20of%20Education.

- Eileen Connor, Rebecca Ellis, Michael Turi, “Class Action Complaint,” Project on Predatory Student Lending, May 4, 2023, https://static1.squarespace.com/static/62d6e418e8d8517940207135/t/6453d2437f7ad8622f42a424/1683214923582/USC+Complaint.pdf.

- Alan Blinder, “Students Paid Thousands for a Caltech Boot Camp. Caltech Didn’t Teach It,” The New York Times, September 29, 2024, https://www.nytimes.com/2024/09/29/us/caltech-simplilearn-class-students.html.

- Lauren Coffey, “OPMs on ‘Life Support’ in Changing Online Marketplace,” Inside Higher Ed, October 11, 2023, https://www.insidehighered.com/news/tech-innovation/2023/10/11/are-opms-life-support-some-experts-think-so.

- Liam, Knox, “Has the OPM Market Already Imploded?” Inside Higher Ed, October 10, 2024, https://www.insidehighered.com/news/tech-innovation/teaching-learning/2024/10/10/report-online-program-manager-growth-slows.

- Trace Urdan, “Whither OPMs?” Inside Higher Ed, June 18, 2024, https://www.insidehighered.com/opinion/views/2024/06/18/what-investor-nonconfidence-says-about-opm-model-opinion.

- Ben Unglesbee, “2U Files for Bankruptcy,” Higher Ed Dive, July 25, 2024, https://www.highereddive.com/news/2u-chapter-11-bankruptcy-restructuring/722358/.

- Ben Unglesbee, “2U Files for Bankruptcy,” Higher Ed Dive, July 25, 2024, https://www.highereddive.com/news/2u-chapter-11-bankruptcy-restructuring/722358/.

- Taela Dudley assisted with contract procurement and Heather Daniels assisted with analyzing the contracts.

- Lauren Coffey, “New OPM Regulations Aren’t Coming Until 2025, if They Happen at All,” Inside Higher Ed, July 22, 2024, https://www.insidehighered.com/news/government/politics-elections/2024/07/22/opm-regulations-pushed-2025-if-they-happen-all.

- Robert Kelchen, “The Need for Better Data on Online Program Outcomes.” RobertKelchen.com, 2022 https://robertkelchen.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/kelchen_opm_paper.pdf.

- Taela Dudley, Stephanie Hall, Alejandra Acosta, and Amy Laitinen, “Outsourcing Online Higher Ed: A Guide for Accreditors,” The Century Foundation, June 28, 2021, https://tcf.org/content/report/outsourcing-online-higher-ed-guide-accreditors/.

- Annmarie Weisman, “GEN-23-03) Requirements and Responsibilities for Third-Party Servicers and Institutions (Updated November 14, 2024,” Federal Student Aid, November 14, 2024, https://fsapartners.ed.gov/knowledge-center/library/dear-colleague-letters/2023-02-15/requirements-and-responsibilities-third-party-servicers-and-institutions-updated-november-14-2024.

- Liam Knox, “Education Dept. Moves Forward With Bundled Services Guidance,” Inside Higher Ed, November 11, 2024, https://www.insidehighered.com/news/quick-takes/2024/11/11/education-department-pushes-new-bundled-services-guidance.

- Stephanie Hall, “Memo to College Leaders: Revising Your OPM Contracts Is In Your Best Interest,” The Century Foundation, March 31, 2022, https://tcf.org/content/report/memo-to-college-leaders-revising-your-opm-contracts-is-in-your-best-interest/.

- Stephanie Hall, “Memo to College Leaders: Revising Your OPM Contracts Is In Your Best Interest,” The Century Foundation, March 31, 2022, https://tcf.org/content/report/memo-to-college-leaders-revising-your-opm-contracts-is-in-your-best-interest/.

- Stephanie Hall, “Your OPM Isn’t a Tech Platform. It’s a Marketing Firm,” The Century Foundation, January 20, 2023, https://tcf.org/content/commentary/your-opm-isnt-a-tech-platform-its-a-predatory-marketing-firm/.

- Stephanie Hall, “The Students Funneled Into For-Profit Colleges,” The Century Foundation, May 11, 2021, https://tcf.org/content/report/students-funneled-profit-colleges/.

- Amber Villalobos, “Online College Programs Increasingly Put Black and Hispanic Students at Risk,” The Century Foundation, November 17, 2023, https://tcf.org/content/commentary/online-college-programs-increasingly-put-black-and-hispanic-students-at-risk/.

- Amber Villalobos, “A Quick Guide to Online Program Managers (OPMs),” The Century Foundation, October 24, 2023, https://tcf.org/content/commentary/a-quick-guide-to-online-program-managers-opms/.

- Natalie Schwartz, “What 2U’s new flat fee model could mean for the online degree sector,” Higher Ed Dive, September 12, 2023, https://www.highereddive.com/news/2u-flat-fee-model-opm-online-degrees/693330/#:~:text=Under%20the%20model%2C%202U%20will,replicate%2C%E2%80%9D%20Paucek%20told%20analysts.

- Taela Dudley, Stephanie Hall, Alejandra Acosta, and Amy Laitinen, “Outsourcing Online Higher Ed: A Guide for Accreditors,” The Century Foundation, June 28, 2021, https://tcf.org/content/report/outsourcing-online-higher-ed-guide-accreditors/.

- Taela Dudley, Stephanie Hall, Alejandra Acosta, and Amy Laitinen, “Outsourcing Online Higher Ed: A Guide for Accreditors,” The Century Foundation, June 28, 2021, https://tcf.org/content/report/outsourcing-online-higher-ed-guide-accreditors/.

- See Stephanie Hall and Taela Dudley, “Dear Colleges: Take Control of Your Online Courses,” The Century Foundation, September 12, 2019, https://tcf.org/content/report/dear-colleges-take-control-online-courses/.

- Stephanie Hall, “Your OPM Isn’t a Tech Platform. It’s a Marketing Firm,” The Century Foundation, January 20, 2023, https://tcf.org/content/commentary/your-opm-isnt-a-tech-platform-its-a-predatory-marketing-firm/.

- Stephanie Hall, “The Students Funneled Into For-Profit Colleges,” The Century Foundation, May 11, 2021, https://tcf.org/content/report/students-funneled-profit-colleges/.

- Amber Villalobos, “Online College Programs Increasingly Put Black and Hispanic Students at Risk,” The Century Foundation, November 17, 2023, https://tcf.org/content/commentary/online-college-programs-increasingly-put-black-and-hispanic-students-at-risk/.

- Project on Predatory Student Lending Press Release, “Social Work Graduate Students Sue USC Over Online MSW “Diploma Mill”, PPSL, https://www.ppsl.org/news/social-work-graduate-students-sue-online-msw-diploma-mill.

- Student Defense, “Students File Lawsuit Against USC and 2U for Deceptive Enrollment Scheme,” Student Defense, December 20, 2022, https://defendstudents.org/news/students-file-lawsuit-against-usc-and-2u-for-deceptive-enrollment-scheme#:~:text=Student%20Defense%20and%20Tycko%20%26%20Zavareei%20LLP%20today,Report%20rankings%20of%20the%20Rossier%20School%20of%20Education.

- Laura Hamilton, Heather Daniels, Christian Michael Smith, and Charlie Eaton, “The Private Side of Public Universities: Third-party providers and platform capitalism,” Berkeley Center For Studies in Higher Education, June 2022, https://escholarship.org/uc/item/7p0114s8.

- Validated Insights, “OPM Market Insights,” September 2024, https://www.validatedinsights.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/OPM-Market-Insights-September-2024-v1.0.pdf.

- Annmarie Weisman, “(GEN-23-03) Requirements and Responsibilities for Third-Party Servicers and Institutions (Updated November 14, 2024),” U.S. Department of Education, February 15, 2023. https://fsapartners.ed.gov/knowledge-center/library/dear-colleague-letters/2023-02-15/requirements-and-responsibilities-third-party-servicers-and-institutions-updated-november-14-2024.

- Post OPM, “Exploring the Future of Higher Education Partnerships” March 5–6 2024, https://postopm.com/.

- See Exhibit C of the 2020 contract in the appendices.

- 2U, “Transforming Education Together,” 2U https://2u.com/partners/.

- Matt Hamilton and Teresa Watanabe, “USC peddled inferior online social work grad program to use as ‘cash cow,’ lawsuit alleges,” Los Angeles Times, May 5, 2023, https://www.latimes.com/california/story/2023-05-05/usc-sold-inferior-online-degree-to-use-as-cash-cow-suit-alleges.

- Lauren Coffey, “2U Bankruptcy Adds Fuel to OPM Uncertainties,” Inside Higher Ed, July 26, 2024, https://www.insidehighered.com/news/business/2024/07/26/long-embattled-2u-declares-bankruptcy.

- Alan Blinder, “Students Paid Thousands for a Caltech Boot Camp. Caltech Didn’t Teach It,” The New York Times, September 29, 2024, https://www.nytimes.com/2024/09/29/us/caltech-simplilearn-class-students.html.

- See Schedule C of original agreement in the appendices.

- Liam, Knox, “Has the OPM Market Already Imploded?” Inside Higher Ed, October 10, 2024, https://www.insidehighered.com/news/tech-innovation/teaching-learning/2024/10/10/report-online-program-manager-growth-slows.

- Validated Insights, “OPM Market Insights,” September 2024, https://www.validatedinsights.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/OPM-Market-Insights-September-2024-v1.0.pdf.

- Lauren Coffey, “Alleging ‘Negligence,’ Fordham Files to Cut Ties With 2U,” Inside Higher Ed, September 12, 2024, https://www.insidehighered.com/news/tech-innovation/administrative-tech/2024/09/12/fordham-files-cut-ties-incompetent-2u.

- Jessica Blake, “Red States Back Trump’s Plan to Abolish Education Department,” Inside Higher Ed, November 25, 2024, https://www.insidehighered.com/news/government/state-policy/2024/11/25/republican-states-back-trump-plan-abolish-education-dept.

- Katherine Knott, “Republicans Could Abolish the Education Department. How Might That Work?” Inside Higher Ed, November 4, 2024, https://www.insidehighered.com/news/government/student-aid-policy/2024/11/04/what-abolishing-education-department-could-mean.

- The HEA prohibits institutions from providing incentive compensation or bonus payments to recruiters in exchange for securing enrollment or financial aid. The loophole created by the 2011 Bundled Services Guidance allows institutions to receive a cut of tuition in exchange for securing enrollments if they provide a bundle of services in addition to marketing and recruitment.

- Katie Lobosco, “Trump wants to shut down the Department of Education. Here’s what that could mean,” CNN, December 12, 2024, https://www.cnn.com/2024/09/20/politics/department-of-education-shut-down-trump/index.html.

- Amber Villalobos, “Minnesota Leads in Protecting Students from Predatory Online College Programs,” The Century Foundation, July 1, 2024, https://tcf.org/content/commentary/minnesota-leads-in-protecting-students-from-predatory-online-college-programs/.

- Liam, Knox, “Has the OPM Market Already Imploded?” Inside Higher Ed, October 10, 2024, https://www.insidehighered.com/news/tech-innovation/teaching-learning/2024/10/10/report-online-program-manager-growth-slows.

- Lauren Coffey, “A Women’s College’s Profitable Foray Into Online Learning,” Inside Higher Ed, September 12, 2023, https://www.insidehighered.com/news/tech-innovation/teaching-learning/2023/09/12/spelmans-online-program-rakes-nearly-2m-year.

- Natalie Schwartz, “2U and USC part ways on most online degree programs,” Higher Ed Dive, November 9, 2023, https://www.highereddive.com/news/2u-usc-part-ways-online-degrees/699413/.

- Stephanie Hall and Taela Dudley, “Dear Colleges: Take Control of Your Online Courses,” The Century Foundation, September 12, 2019, https://tcf.org/content/report/dear-colleges-take-control-online-courses/.

- Auditor of the State of California, “Report 2023-106,” Auditor of the State of California, June 2024, https://www.auditor.ca.gov/wp-content/uploads/2024/06/2023-106-Report.pdf.

- Auditor of the State of California, “Report 2023-106 Fact Sheet,” Auditor of the State of California, June 6, 2024, https://www.auditor.ca.gov/wp-content/uploads/2024/06/2023-106-Fact-Sheet-Final.pdf.