Foster youth are often an afterthought when it comes to making state and federal policies. Disenfranchised members of society by no fault of their own, children in foster care face extraordinary challenges when making the transition into adulthood—with getting into and paying for college being one of the most daunting. Unfortunately, the data, research, and policy approaches toward ensuring that foster youth can access higher education and achieve their full potential have all fallen short. Greater investment in existing federal programs and reforms designed to promote postsecondary success among foster youth are needed if higher education is to make progress toward its aspirational role as “the great equalizer.”

This report discusses the barriers that foster youth face when trying to access the higher education system, particularly those who are still in the system when they “age out.” It provides new data on the affordability challenges that foster youth in higher education have, analyzes current policy interventions, and recommends how policymakers can better support the lives and education of these individuals.

Background

The foster care system is an essential part of the nation’s social safety net. Serving as a refuge for children who have been removed from their homes by the state due to neglect or other abuse, the U.S. foster care system serves roughly 440,000 youth nationwide.1 Once these children enter the foster care system, the state may place them in a private home, a group home, or an institution.

The foster care system is woefully underfunded,2 and thus has very few resources to provide for children who are exiting foster care, whether they are reunifying with their birth parents, being adopted by new parents, or aging out of the system entirely.3 Every year, roughly 20,000 individuals4 age out of the foster care system at ages ranging from 18 to 21, depending on state policies.5 These foster youth, who come from troubled homes and are often raised in under-funded or otherwise inadequate settings, are mostly left to fend for themselves as they acclimate to life as adults when they age out.6

Within four years of aging out of the foster care system, 70 percent of foster youth will be on government assistance, 25 percent will not have completed high school, 50 percent will have no earnings.

The price of underinvesting in our foster youth does not just result in deeply unfair individual circumstances for youth trying to make their way in the world: it also results in $1 million in societal costs per foster youth.7 Within four years of aging out, 70 percent of foster youth will be on government assistance, 25 percent will not have completed high school, 50 percent will have no earnings, and those who do have earnings will make an average annual income of only $7,500.8 A study by the Alliance for Excellent Education showed that a single 18-year-old who does not complete high school earns $260,000 less in income and pays $60,000 less in federal and state income taxes over their lifetime.9 Furthermore, foster care youth represent nearly 15 percent of the inmates of state prisons and almost 8 percent of the inmates of federal prisons, and the cost of incarcerating former foster youth is roughly $5.1 billion per year.10 On the other hand, research shows that when communities invest in foster youth and make sure they’re well taken care of through extended care programs, these communities see a return of roughly two dollars for every dollar invested.11

Higher education is a path to a stable future for many youth aging out of foster care, but too often the barriers for this population prove insurmountable. Foster youth aging out of the system are at a greater disadvantage than many first-generation college students when it comes to navigating the world of college applications, the FAFSA, and paying for college. Providing foster youth clear and accessible pathways into higher education can be one avenue to help them thrive as adults. A study by the Jim Casey Youth Opportunities Initiative12 examined the importance of education during the critical coming-of-age years. The study concluded that over the past ten years, 300,000 foster youth have aged out of foster care without the support needed to successfully transition into adulthood.13 Education can often be a ticket to a better life, but only a small percentage of foster youth attend a college or university.

State, federal, and local governments have not only a moral obligation to these children, but also a legal one.

State, federal, and local governments have an obligation to ensure adequate resources and a path into adulthood for youth with experience in foster care. It is a government agency that makes the decision to seek placement of a child in the foster care system, and while the foster parents or institution are responsible for the day-to-day care of the minor, the government agency remains ultimately responsible as a surrogate in loco parentis for the child, and therefore makes all legal decisions.14 State, federal, and local governments have not only a moral obligation to these children, but also a legal one.

The Challenges College-bound Foster Youth Face

Students that are foster youth face disproportionate barriers when seeking a degree in comparison to their peers. Foster youth go to college at lower rates than their non-foster peers, and often have trouble paying the total cost when they do. Even after federal aid, the costs can be unsurmountable: college-bound foster youth who age out of foster care, apart from rare circumstances, have no financial sponsor or safety net.

Less than 3 percent of foster youth receive a bachelor’s degree,15 in contrast to 24 percent of young adults in the general population.16 This gap in higher education attainment is not for lack of interest. A 2014 California Youth Transitions to Adulthood (CalYOUTH) study by Chapin Hall at the University of Chicago that surveyed 727 foster youth, for example, found that 80 percent of those surveyed reported wanting to earn a college degree or higher.17 Yet, in 2017, a Chapin Hall memo involving the participants in the above-mentioned study found that only 54.8 percent of the foster youth surveyed in 2014 had actually enrolled for even one semester of college by 2017.18

Painting a full picture of the challenges foster youth face when trying to access college, however, is difficult because federal data on foster youth and college access is limited by the questions asked when collecting survey and administrative data. The FAFSA application provides some information, for example, but it only collects data on foster youth who are under age 24 and who check “orphan” on their financial aid application—a category that is slightly broader than former foster youth, because it applies to any student who is an orphan, ward of the court, or in foster care.19 This also means that researchers have only limited data—gleaned from other sources—on former foster youth who are over the age of 24.

These data limitations become clear when trying to determine the size of the student population. The count for “orphans” in higher education in 2008—according to the National Postsecondary Student Aid Study survey, which used a narrower definition to describe the “orphan” category— was about 1.1 percent of undergraduate enrollment, or approximately 80,000 students. There wasn’t any publicly available data on this population again until 2016, when the same survey used a new definition that includes students ages 24 and above, counting 6.2 percent of undergraduate enrollment, or about 1 million students. We know from the orphan age breakdown that over half in that population are ages 24 and above, so a lot of that jump from 2008 to 2016 is simply from expanding the definition to include older students—though some of it may also be student populations becoming more diverse and nontraditional. However, as previously noted, this category includes orphans, wards of the court, emancipated minors, and students in legal guardianship—a broader group of people than just former foster youth.

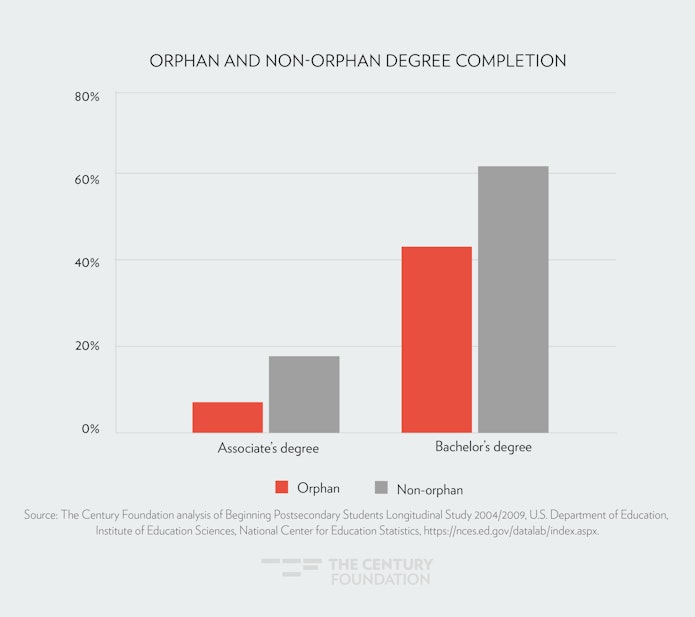

Finding data on how those students fare once enrolled is also difficult, but available data show large disparities between this population and the broader student body regarding things such as financial resources and degree completion. According to the Beginning Postsecondary Students (BPS) survey, 7 percent of orphans had completed an associate’s degree within five years of enrolling, compared to 18 percent of non-orphans.20 At the bachelor’s level, 44 percent of orphans who entered a program had a degree within five years, compared to 63 percent for their counterparts. (See Figure 1.) Orphans are also slightly more likely to attend college at a for-profit institution, many of which prey on vulnerable students, and some of which may even leave students worse off than before they attended that institution.

Figure 1

This population faces significant financial need. About 70 percent of orphans will be assigned an Expected Family Contribution of $0 after completing the Free Application for Federal Student Aid (FAFSA), because 61 percent of orphans have an income under the Federal Poverty Line (compared to 29 percent of non-orphans). Furthermore, a majority of orphans (55 percent) are nontraditional students, meaning they are ages 24 and older, compared to 40 percent of non-orphan students.21

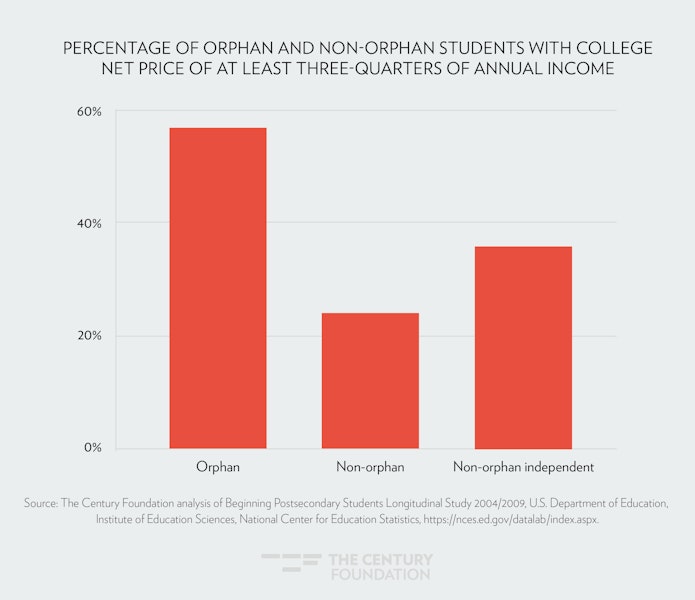

According to National Center for Education Statistics data,22 more than half (57 percent) of orphans had a yearly net price for college (that is, after grants and aid) of at least three-quarters of their income, compared to 24 percent of non-orphans and 36 percent of non-orphan independent students.23 (See Figure 2.)

Figure 2

The financial challenges foster youth face as students mean that they often struggle to meet their basic needs. Foster youth who are students are more likely to be food insecure,24 for example, and the COVID-19 pandemic has only made matters worse for this population: one in five young people reported 25they have run out of food, and only 37 percent of foster youth have family members to rely on during the crisis.26 And the financial challenges are only part of the picture: foster youth also face mental, physical, and emotional challenges at higher rates than their non-foster college-bound peers.27 If foster youth are to thrive in college and beyond, they will need targeted support before, during, and for a transition period after college.

Current Policy Interventions

Programs supporting foster youth have traditionally received bipartisan backing at both the state and federal levels. This section looks at the role that state and federal policymakers have played in pursuing programs to support foster youth and their success in their education, and also discusses two types of federal programs that provide grant aid for foster students.

Sample State Policies

While not the focus of this report, it’s important to acknowledge that states play a significant and wide-ranging role in postsecondary policies that affect foster youth. For example, thirty-eight states have some form of tuition waiver for foster youth.28 The waivers allow students of foster youth to attend select colleges tuition-free. However, these are not solely state policies: the federal John H. Chafee Foster Care Program for Successful Transition to Adulthood (formerly known as the John H. Chafee Foster Care Independence Program; hereafter, referred to as the Chafee Program)29 may supplement or even fund30 some of these state programs. More broadly, state higher education finance policies not specifically targeted to foster youth, such as the level of state investment going to public colleges and the amount of need-based financial aid available, can have an outsized impact on this population.

States have taken a variety of other tactics to support and protect foster youth entering higher education, both through policies directly targeted to this population and policies that have a disproportionate impact. In California, for example, foster students surpassed high school peers in applying for federal student aid by about 8 percentage points following the creation of the FAFSA Challenge, an event created a few years ago by the John Burton Advocates for Youth.31 The state also allows for priority registration, priority access to on-campus housing, expanded eligibility for state financial aid programs, and a state-funded, campus-based support program at forty-five community colleges.32 And in Maryland, the governor recently signed into law the Veteran’s Education Protection Act,33 which closes the loophole in the federal 90/10 rule in the state, reducing an incentive for for-profit institutions to prey upon vulnerable populations such as foster youth that have access to non-Title IV dollars.34 The federal 90/10 rule requires that schools receive no more than 90 percent of their revenue from Title IV federal financial aid programs, but but for-profit schools have been circumventing the spirit of that rule by targeting students accessing other federal aid programs,35 such as GI bill educational benefits, Department of Defense tuition assistance, and Educational Training Vouchers (ETVs).36

Federal Policies

The federal government has two main financing policies for former foster youth trying to afford college: easing the ability of students under age 24 to claim independence, opening up access to financial aid, and the Education Training Voucher program, providing funds to states to support students in postsecondary education.

Current and prospective college students in the United States complete the FAFSA to determine their eligibility for student financial aid. Foster youth are considered wards of the court by the FAFSA process:37 if the foster youth applicant is under the age of 24 when they apply, they are asked to complete a series of questions, which include but are not limited to whether they were in foster care or were a dependent or ward of the court at any time since turning age 13, even if they are no longer in foster care when filling out the form.

In 1975, the Pell grant covered almost 80 percent of the average cost of tuition, fees, room, and board at public four-year colleges; today, the maximum Pell grant covers just 29 percent of those costs.

Students that are wards of the court are automatically deemed independent and thus not required to provide financial information for their parents. Foster youth often have little to no income, so they often receive the maximum Pell grant amount. In 2017–18, 30 percent of Pell grant recipients received the maximum grant of $5,920.38 Of those students receiving the maximum, 48 percent of them were independent students. But for many students, the Pell grant is not enough, as it does not stretch as far as it used to. In 1975, the Pell grant covered almost 80 percent of the average cost of tuition, fees, room, and board at public four-year colleges;39 today, the maximum Pell grant covers just 29 percent of those costs.40

The Chafee Program, which is administered by the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), was created as part of the Foster Care Independence Act of 1999,41 a law designed to help foster youth with education, employment, financial management, housing, emotional support and assure connections to caring adults for older youth in foster care. The Congressional Research Service reported that, in fiscal year 2017, approximately 111,700 youth received an independent living service funded by the Chafee Program.42 These services may have been provided with ETV funds or other public or private funds.

The Chafee program includes a provision specifically designed to address college affordability: in 2002, Congress added the Education and Training Voucher Program to the Chafee Program as a potential source of tuition relief to foster youth who are age 26 or under.43 HHS allocates federal funds to states based on their percentage of children and youth placed in foster care44 for the purpose of creating programs for youth who have experienced foster care at age 14 or older. ETVs provide financial assistance to foster youth who attend an accredited college, university, vocational, or technical college.45 The maximum award a student can receive is $5,000 per academic year, and the awards are determined by the cost of attendance (COA) formula established by the college or university where the youth is enrolled, along with any unmet need they may have within their financial aid award. Not every youth will receive the maximum amount, but the funds may be used for tuition and non-tuition costs. The maximum award amount has not kept up with the cost of attendance, and the program has not had an increase in funding in years, so many states quickly run out of Chafee Program funds each year.46

Some states administer ETV funds47 through already existing state-funded programs that support older and former foster youth. Other states, such as California, administer funds through their financial aid agency.48 Florida and a few other states administer funds at a local level, where all child welfare programs are managed through community-based agencies. The availability of funds vary by state, and the pot of money is limited; in a state such as California—where it is first come, first served—students are frequently turned away because of a lack of funding.49

The Pell grant and ETV only make up for some of the financial hardship faced by members of the foster youth cohort, and members of Congress have passed additional measures in the wake of COVID-19. Most recently, the stimulus and omnibus bill passed in December 2020 made changes to the Chafee Program and ETV, and to financial aid processes more broadly. Fiscal year 2021 appropriation for the Chafee Program50 saw an increase to $400 million from their fiscal year 2020 appropriation level of $143 million.51 Congress raised the fiscal year 2020 appropriation level for ETV funds from $43.3 million52 to be no less than $50 million53 for fiscal year 2021; the bill also assists current and former foster youth by loosening54 the requirements for students to prove that they were in foster care at any time past the age of 13, and by reducing the number of questions55 asked on the FAFSA from 108 to 36, making for a less-cumbersome process.

Pending Legislative Proposals

A number of senators and representatives from both parties have recently sponsored proposals supporting college-aspiring foster youth at varying levels of investment.

For example, a House56 and Senate companion bill,57 the Fostering Success in Higher Education Act of 2019, would give $500,000 or more per fiscal year to each state for activities that improve college access, retention, and completion rates for foster youth. Senator Chuck Grassley (R-IA) sponsored the Increasing Opportunity for Former Foster Youth Act,58 which appropriates $20 million a year under the Chafee Program to improve adulthood outcomes for foster youth aging out of the system. The bill targets foster youth who are at risk of homelessness, or who are expecting a child. It is also aimed at foster youth who lack financial stability, and foster youth who have been involved with the juvenile justice system.

Senator Patty Murray and the late Representative Elijah Cummings each sponsored bills of their own that aim to help former foster youth succeed in higher education. The Higher Education Access and Success for Homeless and Foster Youth Act, which was introduced by Senator Murray, requires that institutions receiving federal money have a designated staff person to help foster youth access and complete college.59 The bill requires these schools to ensure that foster youth are connected to applicable and available student support services. These services include programs and community resources in areas such as financial aid, academic advising, housing, food, public benefits, health care, health insurance, mental health, child care, transportation benefits, and mentoring. The late Representative Cummings’s bill offers support to foster youth aging out of the system and transitioning into adulthood by strengthening the direct responsibility of the federal government for foster youth transitioning out of care.60

The COVID-19 pandemic has also spurred both Republicans and Democrats to propose new bills targeted at foster youth. Representatives Danny Davis (D-IL) and Jackie Walorski (R-IN) sponsored the Supporting Foster Youth and Families through the Pandemic Act, which seeks to aid vulnerable foster youth, including through supports to help families stay together and keep children safe.61 The bill provides substantial aid to older foster youth by freezing the mandatory aging out of care during the pandemic and by allocating funding for state-provided services during the pandemic. Congressman James Langevine (D-RI) sponsored a bill to temporarily modify the Chafee Program during the COVID-19 pandemic by expanding increases in federal funding for foster care services, extending eligibility for such services through age 25, suspending the limit on state expenditures on housing for youth who have aged out of foster care, and suspending the five-year time restriction on eligibility for older youth to receive education and training vouchers.62

Other proposals not narrowly targeted to foster youth may still have an outsized impact on this population as they enroll in college. For example, a recent bipartisan bill introduced by Congresswoman Kendra Horn (D-OK) provides emergency funding to the Federal TRIO Programs to bolster student access to counselors, tutors, and mentors.63 Federal TRIO Programs serve first-generation, low-income students, students with disabilities, students in foster care, students experiencing homelessness, unemployed adults, and veterans. The bill would appropriate $450 million to serve 330,000 additional students, $250 million to expand the program, and $200 million for technology support.64

Recommendations

A lot can be done in the long-term effort to reform the foster care system more broadly that will impact the ability of foster youth to succeed as adults, and specifically to achieve their higher education goals. Specifically, to improve college affordability for this population, federal policymakers could pursue several key strategies.

- Improve data collection. It is difficult to understand the challenges facing this population in paying for school, not to mention design and cost out targeted programs, when data collection is sporadic and imprecise. Currently, it is virtually impossible to isolate data on foster youth in federal government databases when “foster youth” as a metric is rolled into “orphan,” and their data points are mixed with homeless youth, veterans, and other disadvantaged youth. The lack of current and precise data makes it difficult to quantify the size of the population, the scale of financial need, the debt burdens they face, and more.

- Federal funds for campus-based support programs. Foster youth in campus-based support programs do better in their academics than other foster youth. GPA metrics collected from a two-year California College Pathways study65 found that in both 2012–13 and 2013–14 foster youth students participating in campus-based support programs specifically for foster youth had higher GPAs than the general population of foster youth. Congress should expand support for campus-based support programs that serve youth who had experienced foster care at the age of or after 13.

- Increase ETV funding. The ETV program is a standalone affordability program well-targeted at the foster youth population—it just does not provide enough support. A coalition of 110 national and state organizations have asked Congress to increase the ETV funding by $500 million.66 Given the outstanding costs facing foster youth as a percentage of income, as compared to the broader population, it’s clear that this targeted investment is critical to leveling the playing field for these students.

- Extend eligibility for ETV funding. Students often drop out of a higher education program and then return, sometimes years later; the majority of orphans are nontraditional students (ages 24 and older). To ensure that these individuals are able to draw funds during their entire undergrad tenure, the window for ETV eligibility needs to extend from five years to at least match Pell grant eligibility of six years, possibly longer. Also, this extension would need to be accompanied by a funding increase so as to not reduce the availability of the program to new incoming students. More data on the trajectory of foster youth throughout the higher education system will help identify the appropriate length.

- Support expansion of federal need-based aid. Other financial aid reforms targeted at low-income students will almost certainly have an outsized effect on the foster youth population. For example, given that 39 percent of foster youth qualify for the maximum Pell grant, proposals to double the Pell grant and index the grant to inflation will almost certainly have an outsized impact.67

- Incentivize extended foster care. For many states, aging-out of the foster care system happens at age 18, but for many foster youth, the foster care system is the only source of structure and support that they have as they come to age—which means aging out is more like going over a cliff. Federal policy could do more to incentivize the twenty states that currently do not extend that support to age 21 to do so, which would at least provide foster youth with a support system if they do decide to pursue higher education.68 Stronger federal policy, if done right, will allow foster youth the opportunity for better services and a chance to have a better young adult outcome than they otherwise would.69

Looking Ahead

The federal government needs to do more to ensure the success of foster youth: too many foster youth report a goal of enrolling in college, yet few attain a degree. Broad efforts to expand need-based financial aid, combined with support for the targeted ETV program, will provide a much-needed relief to an often forgotten cohort. Graduating high school and college at lower rates than their peers, foster youth face more than just financial hardships from the start. The federal government can do more, and in the midst of a pandemic and recession that has the harshest effects on the most vulnerable in our society, now is the time to act.

Notes

- “6 Quick Statistics On The Current State Of Foster Care,” iFoster, accessed September 4, 2020, https://www.ifoster.org/6-quick-statistics-on-the-current-state-of-foster-care/.

- Sarah A. Font, and Elizabeth T. Gershoff, “Foster Care: How We Can, and Should, Do More for Maltreated Children,” Social Policy Report, November 30, 2020, https://srcd.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/sop2.10.

- Sarah A. Font, Lawrence M. Berger, Maria Cancian, and Jennifer L. Noyes, “Permanency and the Educational and Economic Attainment of Former Foster Children in Early Adulthood,” American Sociological Association, accessed December 22, 2020, https://drive.google.com/file/d/1H84uKY7CKZBaEE4t-QZS6LNBkV6RsK8t/view.

- “Adoption and Foster Care Analysis and Reporting System (AFCARS) FY 2019 data,” The AFCARS Report, accessed December 21, 2020, https://www.acf.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/cb/afcarsreport27.pdf.

- “About the children,” AdoptUsKids, accessed September 11, 2020, https://www.adoptuskids.org/meet-the-children/children-in-foster-care/about-the-children#.

- Chris Bennett Klefeker, “Foster Care Alumni on Campus: Supporting an At-Risk First Generation Student Population,” NACADA, December 01, 2009, https://nacada.ksu.edu/Resources/Academic-Advising-Today/View-Articles/Foster-Care-Alumni-on-Campus-Supporting-an-At-Risk-First-Generation-Student-Population.aspx.

- “6 Quick Statistics On The Current State Of Foster Care,” iFoster, accessed September 4, 2020, https://www.ifoster.org/6-quick-statistics-on-the-current-state-of-foster-care/.

- Ibid.

- “Cost Avoidance: The Business Case for Investing in Youth Aging Out of Foster Care,” Jim Casey Youth Opportunities Initiative, May 2013, https://www.aecf.org/m/resourcedoc/JCYOI-CostAvoidance-2013.pdf#page=5.

- Nicholas Zill, Ph.D, “Better Prospects, Lower Cost: The Case for Increasing Foster Care Adoption,” Adoption Advocate, May 2011, https://www.adoptioncouncil.org/images/stories/NCFA_ADOPTION_ADVOCATE_NO35.pdf.

- Alexa Prettyman, “Happy 18th Birthday, Now Leave: The Hardships of Aging Out of Foster

Care,” Andrew Young School of Policy Studies, October 2020, https://www.alexaprettyman.com/uploads/1/1/8/0/118046286/prettyman_extendedfostercare_jmp.pdf. - “Cost Avoidance: The Business Case for Investing in Youth Aging Out of Foster Care,” Jim Casey Youth Opportunities Initiative, May, 2013, accessed December 22, 2020, https://www.aecf.org/resources/cost-avoidance-the-business-case-for-investing-in-youth-aging-out-of-foster/.

- Ibid.

- “Foster care in the United States,” Wikipedia, accessed December 22, 2020, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Foster_care_in_the_United_States.

- Molly Sarubbi, Emily Parker, and Brian A. Sponsler, “Strengthening Policies for Foster Youth Postsecondary Attainment,” Education Commission of the states, October 2016, https://www.ecs.org/wp-content/uploads/Strengthening_Policies_for_Foster_Youth_Postsecondary_Attainment-1.pdf.

- “Improving Family Foster Care: Findings from the Northwest Foster Care Alumni Study,” Foster Care Alumni Studies, accessed October 13, 2020, https://caseyfamilypro-wpengine.netdna-ssl.com/media/AlumniStudies_NW_Report_FR.pdf.

- Mark E. Courtney, Pajarita Charles, Nathanael J. Okpych, Laura Napolitano, and Katherine Halsted, “Findings from the California Youth Transitions to Adulthood Study (CalYOUTH): Conditions of Foster Youth at Age 17,” Chapin Hall at the University of Chicago, 2014, https://www.chapinhall.org/wp-content/uploads/CY_YT_RE1214-1.pdf.

- Nathanael J. Okpych, Mark E. Courtney, and Kristin Dennis, “Memo from CalYOUTH: Predictors of High School Completion and College Entry at Ages 19/20,” Chapin Hall at the University of Chicago, August 2017, https://www.chapinhall.org/wp-content/uploads/CY_HS_IB0817.pdf.

- FAFSA application 2021–22, accessed December 22, 2020, https://studentaid.gov/sites/default/files/2021-22-fafsa.pdf.

- The Century Foundation analysis of Beginning Postsecondary Students Longitudinal Study 2004/2009, U.S. Department of Education, Institute of Education Sciences, National Center for Education Statistics, https://nces.ed.gov/datalab/index.aspx.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- An independent student meets one or more of the following criteria: at least 24 years old, married, a veteran, a member of the armed forces, an orphan, a ward of the court, someone with legal dependents other than a spouse, an emancipated minor or someone who is homeless or at risk of becoming homeless.

- Sara Goldrick-Rab, Jed Richardson, Joel Schneider, Anthony Hernandez, and Clare Cady, “Still Hungry and Homeless in College,” HopeLab, April 2018, https://hope4college.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/Wisconsin-HOPE-Lab-Still-Hungry-and-Homeless.pdf; Mauriell H. Amechi, “How to Support College Students Aging Out of Foster Care During COVID-19,” The Education Trust, June 23, 2020, https://edtrust.org/resource/how-to-support-college-students-aging-out-of-foster-care-during-covid-19/.

- “Press Release: Young People from Foster Care Hit Hard by COVID-19, Lack Resources and Connections to Weather this Storm,” FosterClub, accessed September 11, 2020, https://www.fosterclub.com/blog/announcements/press-release-young-people-foster-care-hit-hard-covid-19-lack-resources-and.

- “Ways and Means Leaders Introduce Bipartisan Bill to Provide Emergency Support for Foster Youth and Child Welfare Services,” Ways and Means Committee, August 7, 2020, https://waysandmeans.house.gov/media-center/press-releases/ways-and-means-leaders-introduce-bipartisan-bill-provide-emergency.

- “Getting foster youth through college will take structured support, study concludes,” ScienceDaily, April 19, 2015, https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2015/04/150419193908.htm.

- “Foster Care and Higher Education: Tuition Waivers By State,” Washington University, accessed September 11, 2020, https://depts.washington.edu/fostered/tuition-waivers-state.

- “John H. Chafee Foster Care Program for Successful Transition to Adulthood,” Congressional Research Service, January 15, 2019, https://fas.org/sgp/crs/misc/IF11070.pdf.

- Michael R. Pergamit, Marla McDaniel, Amelia Hawkins, “Housing Assistance for Youth Who Have Aged Out of Foster Care: The Role of the Chafee Foster Care Independence Program,” The Urban Institute, May 2012, https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/publication/23461/412787-Housing-Assistance-for-Youth-Who-Have-Aged-Out-of-Foster-Care.PDF.

- Ashley A. Smith, “Financial aid application rates soar among California foster youth,” EdSource, July 15, 2020, https://edsource-org.cdn.ampproject.org/c/s/edsource.org/2020/financial-aid-application-rates-soar-among-california-foster-youth/636099/amp.

- Debbie Raucher, John Burton Advocates for Youth, phone conversation, August 26, 2020.

- “HB 593 / SB 294—Veterans’ Education Protection Act,” Maryland Consumer Rights Coalition, accessed September 18, 2020, https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5b05bed59772ae16550f90de/t/5e95fc25e8579f209b67a75d/1586887717995/HB+593+_+SB+294+Veterans%27+Education+Protection+Act+Factsheet+%282%29.pdf.

- “2020 Legislative Wins,” Maryland Consumer Rights Coalition, accessed September 18, 2020, https://www.marylandconsumers.org/legislative-wins.

- Maryland Consumer Rights Coalition, Facebook, accessed September 25, 2020, https://www.facebook.com/marylandconsumers/posts/10158322716687122.

- Maryland Consumer Rights Coalition, Facebook, accessed September 19, 2020, https://www.facebook.com/marylandconsumers/posts/10158322716687122.

- “How to Answer FAFSA Questions #52: Ward of State,” Nitro, accessed October 13, 2020, https://www.nitrocollege.com/fafsa-guide/question-52-ward-of-state.

- “Trends in Student Aid 2019,” College Board, accessed October 13, 2020, https://research.collegeboard.org/pdf/2019-trendsinsa-figs20a-20b-21a-21b.pdf.

- Spiros Protopsaltis, and Sharon Parrott, “Pell Grants—a Key Tool for Expanding College Access and Economic Opportunity—Need Strengthening, Not Cuts,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, July 27, 2017, https://www.cbpp.org/research/federal-budget/pell-grants-a-key-tool-for-expanding-college-access-and-economic-opportunity.

- Ibid.

- “John H. Chafee Foster Care Independence Program,” Children’s Bureau, June 28, 2012, https://www.acf.hhs.gov/cb/resource/chafee-foster-care-program.

- “Youth Transitioning from Foster Care: Background and Federal Programs,” Congressional Research Service, May 29, 2019, https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/RL/RL34499.

- Ibid.

- Charles Greevy, “Chafee ETV Funds,” Foster Focus, accessed September 25, 2020, https://www.fosterfocusmag.com/articles/chafee-etv-funds.

- “Educational and Training Vouchers for Current and Former Foster Care Youth,” U.S. Department of Education Student Aid website, accessed September 25, 2020, https://studentaid.gov/sites/default/files/foster-youth-vouchers.pdf.

- Jennifer Pokempner, Juvenile Law Center, phone conversation, September 22, 2020.

- “Youth Transitioning from Foster Care: Background and Federal Programs,” Congressional Research Service, accessed September 25, 2020, https://fas.org/sgp/crs/misc/RL34499.pdf.

- Debbie Raucher, John Burton Advocates for Youth, phone conversation, August 26, 2020.

- Ibid.

- “Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2021,” House Rules Committee, December 21, 2020, https://rules.house.gov/sites/democrats.rules.house.gov/files/BILLS-116HR133SA-RCP-116-68.pdf.

- “John H. Chafee Foster Care Program for Successful Transition to Adulthood,” Congressional Research Service, January 15, 2019, https://fas.org/sgp/crs/misc/IF11070.pdf.

- “Explanatory Statement for Departments of Labor, Health and Human Services, and Education, and

Related Agencies Appropriations Bill, 2021,” United States Senate Committee on Appropriations, accessed January 7, 2021, https://www.appropriations.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/LHHSRept.pdf. - “Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2021,” House Rules Committee, December 21, 2020, https://rules.house.gov/sites/democrats.rules.house.gov/files/BILLS-116HR133SA-RCP-116-68.pdf.

- Ibid.

- Danielle Douglas-Gabriel, “Congress could simplify FAFSA, expand Pell Grant access in spending measure,” The Washington Post, December 21, 2020, https://www.washingtonpost.com/education/2020/12/20/congress-spending-colleges-pell-fafsa/.

- Danny K. Davis, “H.R.2966—Fostering Success in Higher Education Act of 2019,” Congress.gov, accessed September 25, 2020, https://www.congress.gov/bill/116th-congress/house-bill/2966.

- Robert P. Casey Jr., “S.1650—Fostering Success in Higher Education Act of 2019,” Congress.gov, accessed September 25, 2020, https://www.congress.gov/bill/116th-congress/senate-bill/1650/text.

- Chuck Grassley, “S.3025—Increasing Opportunity for Former Foster Youth Act,” Congress.gov, accessed October 13, 2020, https://www.congress.gov/bill/116th-congress/senate-bill/3025/text.

- Patty Murray, “S.789—Higher Education Access and Success for Homeless and Foster Youth Act,” Congress.gov, accessed October 13, 2020, https://www.congress.gov/bill/116th-congress/senate-bill/789/text.

- John Lewis, “H.R.7591—Fostering Healthy Transitions into Adulthood Act of 2020,” Congress.gov, accessed October 13, 2020, https://www.congress.gov/bill/116th-congress/house-bill/7591/text.

- “Ways and Means Leaders Introduce Bipartisan Bill to Provide Emergency Support for Foster Youth and Child Welfare Services,” Ways and Means Committee, August 7, 2020, https://waysandmeans.house.gov/media-center/press-releases/ways-and-means-leaders-introduce-bipartisan-bill-provide-emergency.

- James R. Langevin, “H.R.6355—To temporarily modify the John H. Chafee Foster Care Program for Successful Transition to Adulthood in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, and for other purposes,” Congress.gov, accessed September 25, 2020, https://www.congress.gov/bill/116th-congress/house-bill/6355.

- Kendra S. Horn, “H.R.8422—To provide additional appropriations for TRIO programs, and for other purposes,” Congress.gov, accessed October 13, 2020, https://www.congress.gov/bill/116th-congress/house-bill/8422/text?r=2&s=1.

- Destiny Washington, “Rep. Horn introduces COVID College Access and Completion Emergency Relief Act,” Fox 25, October 1, 2020, https://okcfox.com/news/local/rep-horn-introduces-covid-college-access-and-completion-emergency-relief-act.

- “Using Data to Support Foster Youth College Success,” California College Pathways, October, 2015, accessed December 22, 2020, https://www.jbaforyouth.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/Charting-the-Course-Final.pdf.

- “Press Release: Young People from Foster Care Hit Hard by COVID-19, Lack Resources and Connections to Weather this Storm,” FosterClub, May 13, 2020, https://www.fosterclub.com/blog/announcements/press-release-young-people-foster-care-hit-hard-covid-19-lack-resources-and.

- Shelbe Klebs, “Why We Should Double the Pell Grant,” Third Way, July 20, 2020, https://www.thirdway.org/memo/why-we-should-double-the-pell-grant.

- “Extended Foster Care,” Juvenile Law Center, accessed December 22, 2020, https://jlc.org/issues/extended-foster-care.

- Rachel Rosenberg, Samuel Abbott, “Supporting Older Youth Beyond Age 18: Examining Data and Trends in Extended Foster Care,” accessed December 22, 2020, https://www.childtrends.org/publications/supporting-older-youth-beyond-age-18-examining-data-and-trends-in-extended-foster-care.