Introduction

Crisis-level student debt hinders economic progress in many ways, including reinforcing racial wealth inequality.

In order to finance higher education, Black families—already disadvantaged by generational wealth disparities—rely more heavily on student debt, and on riskier forms of student debt, than white families do. The additional risks Black students face when taking on student debt are exacerbated by other disparities in the higher education system, including predatory for-profit colleges that engage in race-based targeting. The disparities continue after these students leave school. Due to lower family wealth and racial discrimination in the job market, Black students are far more likely than white students to experience negative financial events after graduating—including loan default, higher interest rate payments, and higher graduate school debt balances. This means that while many Black families currently need to rely on debt to access a college degree and its resulting wage premium, the disproportionate burden of student debt perpetuates the racial wealth gap. To fairly evaluate any higher education reform proposal, we must understand the ways that these dual burdens—less wealth and more debt—lead to worse outcomes for Black students than white students.

In 2019, Americans collectively owe more than $1.6 trillion in student debt,1 and the number of families burdened has grown rapidly: One in five US households now has student loan debt, compared to one in 10 in 1989.2 In the face of these overwhelming numbers, many policymakers have begun to offer their own tuition-free and debt-free college policy plans—and even debt cancellation proposals—as a way to reinvest in higher education and America’s students. These proposals have sparked a fierce debate about who ought to benefit from this endeavor or how new resources should be allocated. Too often, however, these conversations overlook the critical background context of who currently benefits and loses when much of the higher education system is financed through individual debt rather than upfront public investment.

To provide this context, this report compiles the research on racial disparities both in the use of student debt and in higher education outcomes, specifically focusing on disparities between white students and Black students. In order to do so, we bring together two streams of research that are often siloed: research from experts on higher education access and success alongside research from economists, sociologists, and others who specialize in race inequality and, in particular, the racial wealth gap. These researchers tend to draw on different sets of data and focus on different outcomes, and thus often identify different problems—yet both are critical to designing meaningful reforms. When we bring these strands of research together, we get an increasingly clear picture: the racial wealth gap, high student debt levels, and unequal higher education access and outcomes for students of color—and particularly women of color—continuously reinforce each other.

This report highlights the need for higher education policies that get students of color both into and through college in order to realize the wage benefits of a college degree. It also underscores the need to take into account the structural inequalities and discrimination that shape every step of the experience of students of color both in college—from paying for college to accessing academic opportunities—and in the job market after leaving school with or without a postsecondary credential.

In Section 1 of this report, we describe how historic policy decisions, both in higher education and in the economy more broadly, have contributed to these structural racial inequities. In Section 2, we examine key findings across disciplines from researchers who have studied student debt with a racial lens. Then, we conclude by discussing what policy changes could help break the cycle connecting student debt and the racial wealth gap. This report is followed by an appendix that looks more closely at the data sets used by researchers in different disciplines and an annotated bibliography.

Section 1: The Development of Racial Inequities in the American Higher Education System

Too often in policymaking, we view the inequities in our current system as natural and inevitable instead of as the consequence of deliberate policy choices. The American higher education system, however, is replete with examples of policies that directly exacerbate or create racial inequities. These can include:

- Policies designed to be explicitly racist or lock out people of color from part or all of the educational system;

- Seemingly race-neutral policies deliberately implemented to ensure racist outcomes (and, at times, crafted with this as the intended result); and

- Policies intended to be truly race-neutral that, when implemented within existing inequitable systems, perpetuate racial inequalities.

The racist structures that these policy choices built into the higher education system—in conjunction with similar structures throughout the American economy—have rippling effects today:

The relatively recent policy choice to ask individual students to access higher education through debt-financing has had a disproportionate impact on students of color. By first building a racially discriminatory system, then dismantling only the system’s most overtly racist features, and finally turning student debt—rather than upfront public investment—as a means of broadening access, policymakers have created a system where inequality, discrimination, and structural barriers for black and brown people throughout the economy help determine the cost and the scale of the ultimate financial pay-off of going to college.

The higher education system, a resource intended to serve as a primary tool for economic mobility, is not equally accessible for Black and white families. Such inequality is manifest throughout the broader educational system and economy as well. In the United States, every key economic and social resource—from housing to banking to the K–12 education system—developed in a racist political context. All have inequities baked into their structures that limit economic mobility and Black families’ ability to build wealth.3

K-12 Education

From kindergarten on, most students move through a deeply segregated system.4 The school-integration efforts that followed Brown v. Board of Education saw a reversal starting in the 1980s, when courts allowed state legislatures to unravel the structures put in place to desegregate schools. As a result, schools in many areas of the country have resegregated. By 1989, 83 percent of Black students attended majority-minority schools.5 Segregated schools have resulted in massive resource gaps; predominantly white districts receive nearly $23 billion more in funding than nonwhite districts despite serving a similar number of students, leading to a persistent gap in white and Black graduation rates.6

The Racially Inequitable Expansions of American Higher Education

The racist policy choices underlying the higher education system started with the earliest federal policies supporting the development of the public college and university system. Early federal investment in higher education—for example, the Morrill Act’s creation of land-grant colleges in the 19th century—gave federal funding and land to states with formally segregated higher education systems. Even after the passing of the Civil Rights Act, federal education dollars continued to fund states with segregated systems. At the end of the 1960s, 19 states still operated segregated universities and colleges.7 It was not until the 1970s that courts began to force states to desegregate their university systems.8

Prior to the court-ordered desegregation of state university systems, significant federal investments in the higher-education system—such as the GI Bill and the Higher Education Act of 1965—had very different impacts on Black and white students. Columbia political science professor Ira Katznelson shows that in order to win support from Southern members of Congress, the GI Bill allowed state and local administrators a great deal of autonomy in implementing the program. State officials then made choices that prevented eligible Black GIs from accessing the full range of education benefits: Segregated colleges refused to accept Black GIs in numbers that accommodated all who were eligible; career-placement officers channeled Black GIs away from more lucrative job training programs and toward traditionally Black occupations; and GI bill administrators in some Southern states refused to approve many Black colleges and vocational schools’ receipt of GI Bill benefits.9 In 1947, over 20,000 eligible Black veterans reported being unable to find a spot in a higher education institution.10 Because of the inequitable administration of the GI bill, Black institutions lacked the facilities and funding to meet demand. The disparity in funding for minority-serving institutions has continued to this day.

Present-Day Funding Disparities

Disparities in state funding between two- and four-year public institutions and between flagship and satellite state campuses are prevalent throughout the higher education system. Unsurprisingly, as a result of disparities that manifest in K-12 system, as well as discrimination in admissions and other factors, students of color are more likely than their white counterparts to attend underfunded public institutions that spend less per student.11 The disparities in funding among institutions extend to historically Black colleges and universities (HBCUs). One study found that in 2014, four traditionally white institutions received more in federal, state, and local contracts and grants than all 89 four-year HBCUs combined.12 Even among public institutions, public HBCUs have fewer non-public resources: 54 percent of public, four-year HBCUs’ revenue comes from government sources, while their predominantly white counterparts only rely on government sources for 38 percent of their annual revenue.13 And because alumni have less wealth, private HBCUs have smaller endowments and fewer resources.14 Despite this, HBCUs grant about 17 percent of all bachelor’s degrees awarded to Black students and a full quarter of STEM degrees awarded to Black students.15

For communities of color, where many families saw their net worth cut nearly in half during the recession, we have added high costs and debt to family balance sheets that have not recovered from the crisis over a decade ago.

The racial effects of resource disparities in higher education have worsened over the past few decades as public funding per student has declined. During the Great Recession, many states slashed their higher education budgets. For the most part, the funding has never been recovered. In 2018, state funding for two- and four-year public colleges was over $7 billion below what it was in 2008.16 As a result, tuition has skyrocketed, and academic and student support services have been cut. At the same time, federal support for low-income students has not kept pace with rising costs; the value of grant aid has diminished, requiring students to turn increasingly to loans.17 Notably, student debt was one of the few forms of unsecured credit to remain widely available during the Great Recession, when it became more difficult to open up a credit card or get a personal loan from a bank.18 For communities of color, where many families saw their net worth cut nearly in half during the recession, we have added high costs and debt to family balance sheets that have not recovered from the crisis over a decade ago.19

The Rise of Predatory Institutions

Widespread reliance on federally backed debt to finance higher education has also allowed a predatory industry of for-profit colleges to arise and specifically target students of color and other vulnerable populations. Government-backed student loans were opened up to students at for-profit colleges in 1972 and quickly became integral to these schools’ business models.20 For-profit schools began to market themselves to students of color specifically by helping them navigate the federal student loan system.21 The ensuing influx of capital led to an expansion of the industry in the 1980s that continued into the 1990s, when many for-profit colleges grew into large, publicly-traded companies.22 Between 1990 and 2010, the percentage of bachelor’s degrees coming from for-profit colleges increased sevenfold.23 Today, Black students making up 21 percent of students at for-profit colleges but only 13 percent of students at public colleges.24

For-profit schools’ ability to attract students was given a significant boost by the 2008 recession, when young people sought refuge from a weak labor market in degree programs. Indeed, the for-profit college industry was one of the few to remain profitable during the financial collapse.25 Greater demand for higher education is typical during a recession, but recent research argues that this trend was exacerbated in 2008 by a monopsonized labor market (i.e., a labor market dominated by too small a number of employers), in which employers could demand more credentials for the same jobs. This was particularly harmful for students of color, from whom employers already demanded higher credentials.26

The consequences of debt-financing higher education and other trends in higher education policies have not fallen equally on Black and white families. Inequality and discrimination determine how much wealth a family has available to pay for college, the type of college a student attends, how much debt they take on to attend school, and how easy or difficult it is to pay down debt. In the next section, we explore research from higher education and racial wealth gap experts and discuss how these researchers’ findings complicate the belief that student debt helps create equitable access to higher education.

Section 2: Racial Disparities Endemic to Students’ Educational Life Cycles: Recent Findings from Higher Education and Racial Wealth Gap Experts

Analyses from higher education researchers and racial wealth gap researchers often draw on different data sets and study different outcomes. When combined, these two bodies of work reveal racial disparities at every point in the educational and life cycles, making debt an inequitable means of financing education.

Those who study higher education tend to be engaged primarily with issues related to college access and completion, and to some extent the earnings outcomes of those programs as they relate to the debt incurred. In this regard, student debt policy is often evaluated in terms of whether it equalizes outcomes in access, persistence, and completion, and whether it diversifies enrollment at different institutions. For higher education researchers, outcome measures like loan defaults are often viewed in terms of what they reveal about the quality of an institution. Debt levels may also be measured, but typically as a “return on investment” for the earnings increase provided by the program.

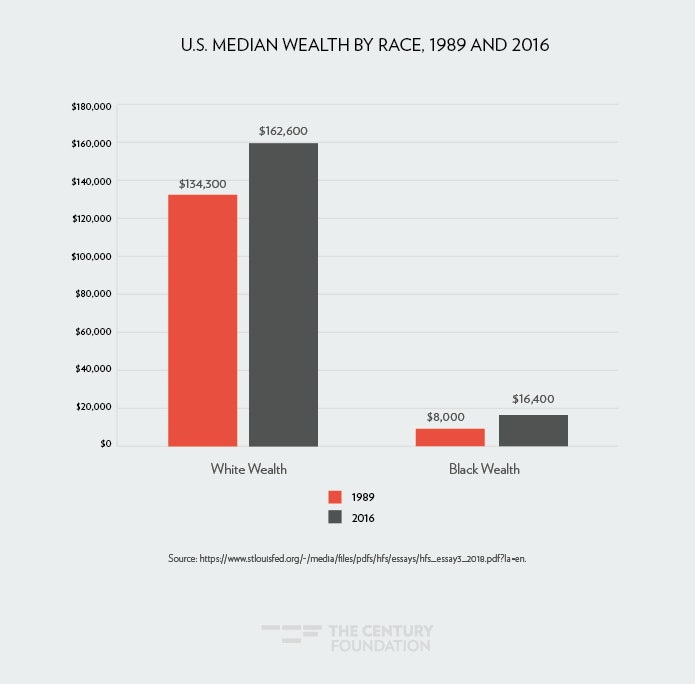

In contrast, racial wealth gap experts are interested in student debt as one of many items on family balance sheets. Their work often asks what student loan debt and defaults tell us about market discrimination or overall asset building. They seek to understand what role student debt has played in creating a situation where the median white family has 10 times the wealth of the median Black family.27

Figure 1

Key Finding: In order to finance higher education, Black families—already disadvantaged by generational wealth disparities—rely more heavily on student debt, and on riskier forms of student debt, than white families do.

Robust research on student debt highlights a core challenge: Within today’s higher education finance structure, Black students would be less able to pay for—and enroll in—college without loans. But while loans are the key to access in the current system, they do not create equitable access. For many of the reasons discussed above, debt is a tool that borrowers of color must rely upon more often compared to white students, potentially putting them at greater financial risk. Thus, the research also makes clear that moving from a debt-financed system to a public investment-financed system would be a significant benefit to Black families.

For many of the reasons discussed above, debt is a tool that borrowers of color must rely upon more often compared to white students, potentially putting them at greater financial risk.

From the beginning of their time in the higher education system, Black students and white students have a different experience with student loans. Using longitudinal data disaggregated by race and released by the US Department of Education in 2017, Center for American Progress, Vice President for Postsecondary Education Ben Miller showed that 78 percent of Black students in the cohort that began college in 2003–2004 took out loans for their undergraduate education, compared to only 57 percent of white students.28 Furthermore, in a 2014 study for the Wisconsin Hope Lab, higher education researchers Sara Goldrick-Rab, Robert Kelchen, and Jason Houle found that while “Black students have always borrowed more than white students, for as long as the federal government has tracked these things,” “the growth in take-up rates of federal student loans between 1995–96 and 2011–12 was also greater for Black students than white students.”29 Black adults are almost twice as likely to have student debt than white adults.31 Research show differences in borrowing between low-income and moderate-income Black and white families,32 but interestingly, Addo and Houle’s study finds racial disparities in student loan debt highest among students with the wealthiest parents. Addo and Houle theorize that this is explained by the different forms in which Black and white families hold their wealth, suggesting that Black families hold what wealth they do have in less liquid forms than white families.33 For example, in the highest-income quintile, Black parents hold roughly 16 percent of their wealth in liquid financial assets, whereas white parents hold 21 percent of their wealth in this form.34 While the Free Application for Federal Student Aid (FAFSA) takes into account liquidity of assets when calculating expected family contribution, fewer than 2 percent of students receive scholarships and grants fully covering the cost of their education.35 When families have to step in to make up the difference between expected family contribution and the total cost of school post-financial aid, white families are often able to cover the remainder with liquid assets, while Black families must often turn to loans.

Table 2

| Among the Wealthy, Black Families Hold their Wealth In Less Liquid Forms | ||||||

| Holdings | Average Amount ($) | % of wealth in type of holding | ||||

| Home Equity | $154,627 | $92,555 | $62,072 | 39% | 31% | 8% |

| Retirement Accounts | $116,960 | $91,915 | $25,045 | 30% | 31% | -1% |

| Financial Assets | $81,827 | $46,579 | $35,248 | 21% | 16% | 5% |

| College Savings Account (CSA) | $12,323 | $14,023 | ($1,700) | 3% | 5% | -2% |

| Other Assets | $30,374 | $51,655 | ($21,281) | 8% | 17% | -10% |

| Source: https://www.stlouisfed.org/publications/in-the-balance/2018/parents-wealth-helps-explain-racial- disparities-in-student-loan-debt. ** Data on parents wealth in highest quintile group. |

||||||

Although Black parents have less wealth with which to support their children, economists Darrick Hamilton and William Darity, Jr. have found that Black families are actually more likely to contribute financially to their children’s higher education at all income levels.36 This eagerness to support their children’s education in the face of unequal labor and credit markets has led many parents of Black students to take on more expensive and riskier forms of debt themselves. For example, a report by Rachel Fishman at the New America Foundation shows that low-income Black families are particularly likely to rely on Parent PLUS Loans, which have no limits up to the full cost of attendance—an amount that goes well beyond tuition to include living expenses. PLUS loans were designed to help middle- and upper- income borrowers, but data shows that among Black borrowers the largest share of borrowers taking out Plus loans have an adjusted gross income of under $30,000 a year.37 This is concerning because like other student loans, Parent PLUS Loans cannot be discharged in bankruptcy, but unlike student loans, they are not eligible for income-based repayment.38 While the literature on parental debt is limited, research confirms that Black parents are more likely to have child-related debt than white parents.39

Parent PLUS Loans are not the only risky form of student debt that Black families have turned to in order to fund higher education. Addo and Houle have also found that Black students and their families are more likely to take on private loans, which carry higher and more variable interest rates and have fewer consumer protections.40 Rajeev Darolia and Dubravaka Ritter, a visiting scholar and a fellow at the Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia respectively, have shown that access to these loans increased when they became riskier for borrowers. They found that the passage of a 2005 law making private student loans non-dischargeable in bankruptcy led to an expansion in the private student loan market.41

In a report for the Samuel DuBois Cook Center on Equity and the Insight Center for Community Economic Development, Hamilton, Darity, Jr., et al., report that when unsecured debt levels are compared across racial demographics and debt categories white families actually report holding slightly more unsecured debt (e.g., debt not backed by property or credit cards) than Black families do.42 But, when the unsecured debt is broken down by type, Black families hold significantly more student and medical debt than white families.

Key Finding: The gap in Black and white students’ degree attainment is higher than it was when the Higher Education Act was passed in 1965, which exacerbates the risks of student loans for Black students.

Black students take out more debt than their white counterparts but, as a result of a wide variety of factors, are less likely to finish their degrees. According to the United Negro College Fund (UNCF), the high dropout rate among Black college students “is partially due to the fact that 65 percent of African American college students are independent”—these students have to work full-time and care for families while trying to complete their degrees. Another compounding factor is the K-12 system. “Only 57 percent of Black students have access to the full range of math and science courses necessary for college readiness.”43 While the college enrollment gap has narrowed in recent years, the completion gap has not.44 The four-year degree attainment gap between Black and white students is greater today than it was when the Higher Education Act was passed in 1965.45

Using 2017 Department of Education data, Robert Kelchen examined Black and white graduation rates at 499 colleges with at least 50 Black and 50 white students in their graduating cohorts. He found that while 59 percent of white students at the schools graduated, only 45.5 percent of Black students did. This 13.5 percent gap was larger than the 7.8 percent gap between students with Pell Grants and those without.46 As discussed above, inequities in college preparation and admissions make Black students far more likely to enroll in less selective, and often under-resourced, colleges that have lower overall college graduation rates.47

The gap in graduation rates is paralleled among borrowers: 39 percent of Black borrowers drop out of college (compared to 29 percent of white borrowers),48 and those who do not complete their degree face steeper challenges with debt. Failing to complete a degree program is correlated with increased risk of default on student loans. Recent studies have found that 45 percent of students in the 2003–2004 cohort who dropped out of college and never attained a credential have defaulted on their student loans.49

Given the current debt-financed higher education system, a few studies have asked whether loans help or hurt Black students in completing degrees. Specifically, they have asked whether federal student loans (1) increase the number of Black students who complete degrees and (2) have similar effects on completion rates for Black and white students. The results of these studies have varied enough to be inconclusive. One study found that for Black students, taking out loans correlated with staying in school longer and having a better chance of completion; another found that student loans widened disparities in Black and white completion rates.50

Key Finding: The additional risks Black students face when taking on student debt are exacerbated by other disparities in the higher education system, including predatory for-profit colleges that engage in race-based targeting.

Research shows that racial disparities throughout the higher-education system shape how Black students experience student debt. For example, studies find that a disproportionate number of Black students attend for-profit colleges. This is the result of both active recruiting by for-profits and the ways in which for-profits deliberately exploit the failures of the nonprofit higher education system—from the byzantine financial aid processes to recruitment practices that rarely reach high schools where the majority of students are people of color—for their own gain.51

Students at for-profit colleges have some of the highest drop-out rates and worst experiences with student debt: 53 percent of borrowers at four-year for-profit programs drop out, including 65 percent of Black borrowers and 67 percent of Latinx borrowers; in contrast, only one in five borrowers at public four-year colleges and one in three borrowers at community colleges do not complete.52

Using a unique set of data matching federal student loan records to US Treasury data, economists Adam Looney and Constantine Yannelis argue that the locus of rising default rates include students at for-profit colleges, two-year schools and nonselective colleges, which encompasses a high number of students of color. These students, according to Looney and Yannelis, are “nontraditional,” in that they tend to be older, independent from their parents, and part-time.53 According to Looney and Yannelis’s data, “Of all the students who left school, started to repay federal loans in 2011, and had fallen into default by 2013, about 70 percent were non-traditional borrowers.” Looney and Yannelis observe that these “non-traditional borrowers” numbers exploded during the Great Recession, representing almost half of all new borrowers in the student loan market.54

In another study, sociologists Louise Seamster and Raphael Charron-Chenier find that the proportion of Black households taking on educational debt doubled between 2001 and 2013 and increased from 6 percent of total household debt burden for Black households to 20 percent (the percent of debt coming from student debt only doubled for white households, from 4 percent to 8 percent). The authors suggest that the growth of the for-profit sector and the growth in private lending during that period—rather than racial differences in income, assets, and family structure—may be drivers of this disproportionate increase.55 Seamster and Charron-Chenier argue that this growth is a form of “predatory inclusion,” whereby “members of a marginalized group are provided with access to a good, service, or opportunity from which they have historically been excluded but under conditions that jeopardize the benefits of access.”56

Key Finding: Due to lower family wealth and racial discrimination in the job market, Black students are far more likely than white students to experience negative financial events after graduating—including loan default, higher interest rate payments, and higher graduate school debt balances.

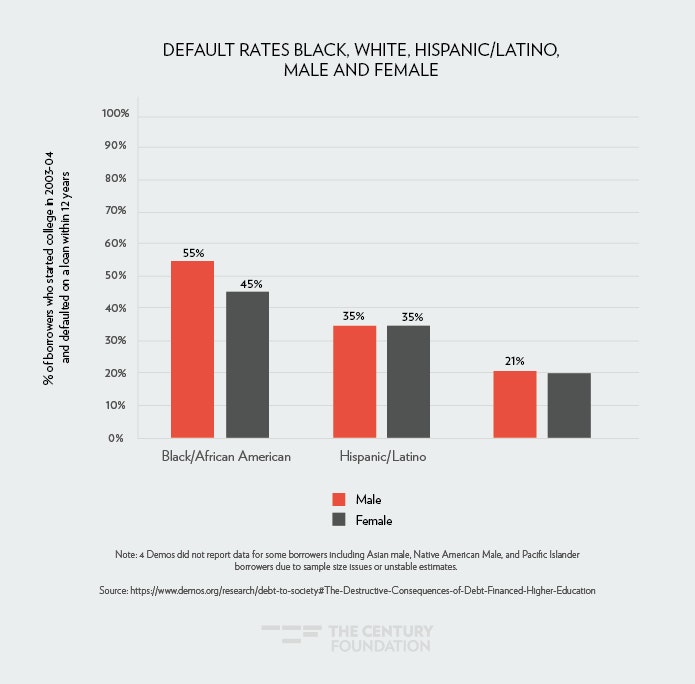

After they leave school—whether with a BA or not—Black student borrowers continue to have very different experiences with their loans than white student borrowers. A recent Demos paper showed that more than half of Black male borrowers who started college in 2003-2004 had defaulted on a loan within 12 years of starting school.57 At the Brookings Institution, Judith Scott-Clayton found that Black BA graduates “default at five times the rate of white BA graduates (21 versus 4 percent)” even after adjusting for differences in degree attainment, college GPA, post-college employment, and institution type. Strikingly, Black BA holders are “more likely to default than white dropouts.”58

Figure 2

Default is not the only measure of trouble for student borrowers. In a study for the Center for American Progress, Ben Miller showed that 12 years after entering college, the median Black borrower had made no progress in paying down their loans; in fact, the balance had actually increased. A Demos report by Mark Huelsman disaggregated this data by gender and found that in the 12 years after starting college, the typical Black female borrower’s student loan balances grew by 13 percent.59 In contrast, the median white borrower owed only 60–65 percent of their original loan at that point, and, 12 years out, Latinx borrowers who began school in 2003 owed only 80 percent of their original loans.60 Roosevelt Fellows Julie Margetta Morgan and Marshall Steinbaum showed distress in another way: the growing number of Black borrowers reporting having debt while making no payments. This subset of borrowers is either in default, delinquent, or using a forbearance or income-based repayment program. In all cases, they are not earning enough to pay off their debt.61

A discriminatory job market that reduces the impact of the college wage premium and lack of family liquidity both contribute to these unequal outcomes. In a recent paper, Seamster and Charron-Chenier point out that the student loan products that Black students and their families often rely on are made more dangerous by the fact that college is less likely to result in a high-wage job for Black Americans.62 At every degree level, Black graduates earn less on average and thus have less money with which to pay back their loans.63 In addition, a 2013 report by economist John Schmitt and Janelle Jones at the Center for Economic and Policy Research showed that 12.4 percent of Black college graduates between 22 and 27 were unemployed—twice the unemployment rate for college graduates as a whole. Furthermore, they concluded that over half of employed Black graduates were underemployed.64

When they do not earn enough to pay back their loans, Black graduates often do not have the family resources to fall back on that many white graduates in this position do. Recent research on inheritance and the racial wealth gap by researchers at the Brandeis’ Institute on Assets and Social Policy, Tatjana Meschede and Joanna Taylor, find that 13 percent of college-educated Black families receive an inheritance of over $10,000 compared to 41 percent of college-educated white families. Moreover, white families receiving above this inheritance on average receive more than three times what Black families do.65 Scott-Clayton’s analysis shows that student-family background, including parental wealth, can account for about half of the gap in Black-white default rates. To explain the rest, Scott-Clayton calls attention to differences in loan counseling and servicing. While there has not been significant research on this issue in relation to student loans, we know racial disparities in loan counseling impact other forms of consumer credit. We need significantly more research and data regarding how these factors affect student debt.66

Scott-Clayton has also conducted research showing that disparities in college graduates’ labor market outcomes may be responsible for Black graduates’ greater enrollment in subsequent education programs; this, in turn, leads to Black graduates carrying more debt. She shows that the debt gap widens quickly in the post-graduate years. While Black students start out with about $7,400 more in debt than their white counterparts, four years after graduation, that gap widens to $25,000. At that point, on average black graduates hold almost twice as much debt as their white counterparts. A quarter of this widening gap comes from differences in repayment. The majority of the remainder (45 percent) comes from different rates of borrowing for graduate school; Black college graduates are both more likely to attend graduate school and more likely to have to borrow to do so.67

Black college graduates are both more likely to attend graduate school and more likely to have to borrow to do so.

Both the number of Black students enrolled in graduate programs and the size of loans taken out to finance this graduate education have risen in recent years. Forty-seven percent of Black students who received a BA in 2008 enrolled in graduate degree programs within four years, compared to 38 percent of white 2008 BA recipients. In 1993, 38 percent of black BA holders and 35 percent of white BA holders enrolled in graduate school, a much narrower gap.68 The loan volume for Black graduate students has also skyrocketed. Robert Kelchen showed that between 2000 and 2016, the percentage of Black graduate students with over $100,000 in debt went from between 1 and 2 percent to roughly 30 percent, the largest increase among all racial and ethnic groups.69

Scott-Clayton’s research shows that one-quarter of Black graduate-school enrollees attend for-profit institutions (as opposed to 9 percent of white graduate students)—the only sector that has seen differential growth by race, and a sector that, as Looney’s research shows, produces worse outcomes.70 And according to the American Council on Education, nearly half of all Black students pursuing doctoral study are enrolled in for-profit colleges, with an average debt of over $128,000.71

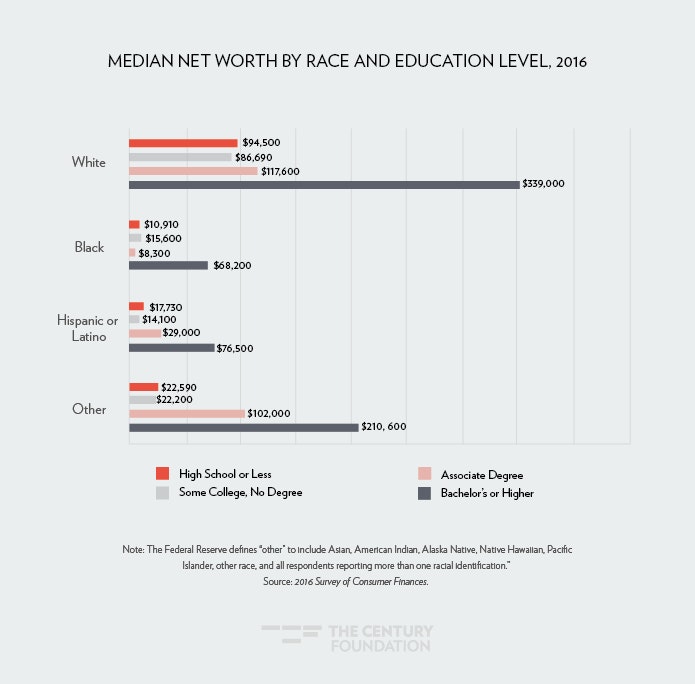

Key Finding: The disproportionate burden of student debt on Black families perpetuates racial wealth inequalities.

Though policymakers often tout education as a key to reducing inequality, research by William Darity, Jr. and Darrick Hamilton shows that increased education does not close the racial wealth gap. The average Black family whose head-of-household has a college diploma has less wealth than a white family whose dominant earner did not finish high school. Only Black families whose predominant earner has post-graduate education have wealth levels comparable to white households headed by someone with partial college education.72

Figure 3

The wealth gap is magnified for women of color. The Insight Center’s Jhumpa Bhattacharya and Anne Price show that college also fails to provide the same wealth gains to Black women that it does to white women. Single Black women in their 30s with a college degree average $0 in wealth (having spent the past decade $11,000 in debt on average).73 Meanwhile, median wealth for white women in their 30s with a college degree is $7,500.74 The difference in wealth between Black college graduates and white high-school dropouts is a striking sign that the debt-financed higher education system may actually be contributing to the racial wealth gap.

Student debt accounts for a measurable minority of the wealth gap between Black and white young adults.75 Addo and Houle find that the racial wealth gap begins to emerge as early as age 25 and then continues to widen.76 They conclude that “student loan debt may be a new mechanism by which racial economic disparities are inherited across generations.”77 In a recent paper, economists Venoo Kakar, Gerald Daniels Jr., and Olga Petrovska find that “differences in student loan use account for 5 percent of the mean wealth gap between [all] Black and white households.” The authors conclude that student debt has its greatest adverse impact on the Black-white wealth gap at the median of the wealth distribution.78 Researchers at Brandeis’s Institute on Assets and Social Policy, Thomas Shapiro, Tatjiana Meschde, and Sam Osoro, reach a similar conclusion. They find that a college degree yields 5 percent more wealth for white families than for Black families, positing it is likely due to unequal access to quality K–12 education and to disparate reliance on student debt.79

The ways in which student debt can perpetuate the racial wealth gap mean that current loan policies do not sufficiently account for all outcomes related to financial security. Students and their families too often get stuck in a cycle where lack of wealth leads them to turn to debt-financing for higher education, which in turn keeps them from building wealth after they leave school.

Conclusion

Many Americans now expect to take out loans to finance their higher education. This was not inevitable; rather, it is the result of policy choices. Those choices were made in the context of a broader education system and economy in which Black students’ and families’ experiences are defined by structural racism. For many years, however, the racial segregation and discrimination that determine Black students’ access to higher education and post-school outcomes went largely unacknowledged by policymakers, who instead built policies based on race-blind or race-neutral assumptions about the effects of a debt-financed higher education system. As a result, the findings discussed in this report show that student debt is both more necessary and riskier for Black families than for white families; and, therefore, perpetuate racial wealth inequality. At a moment when policymakers are reconsidering the structure of higher education, we cannot make the same mistake of ignoring the structural racism embedded in the American higher education system and economy at large.

For many years the racial segregation and discrimination that determine Black students’ access to higher education and post-school outcomes went largely unacknowledged by policymakers, who instead built policies based on race-blind or race-neutral assumptions about the effects of a debt-financed higher education system.

As politicians come forward with new proposals to reform the American higher education system, we should look for policies that seek to decrease racial disparities throughout the system. Some commentators have already begun to do this—debating whether universal debt cancellation or bold and targeted debt relief does more to narrow the racial wealth gap.80 While the racial wealth gap is an incredibly important signal on the overall fairness and health of our economy, the research reviewed in this paper should encourage us to look beyond any single measure of inequality and evaluate how any free college and/or student debt cancellation proposal will affect each point in the cycle of racial inequality and higher education access.

There are some concrete actions that can help narrow the inequitable effects of our current higher education system. For example, policymakers could:

- Bring down the cost of college to reduce reliance on debt: When the federal loan and grant system was created in the 1960s, college cost a fraction of what it does today. Average tuition at a public institution has risen 12-fold since 1978.81 Reducing the cost of college would allow our higher education finance system to function more like it was originally intended.

- Take steps to dismantle segregation in enrollment and racial disparities in completion rates.

- Crack down on predatory, for-profit schools that have historically preyed on students of color.

- Alleviate the burden of existing student debt: Cancelling at least some would automatically build wealth for Black families.

Policymakers also need to rethink our higher education system more broadly. As long as racism pervades the economy and access to a large portion of the higher education system is mediated through high levels of individual loans, neither access to higher education, nor the returns to a degree or credential, will be equitable. To build a higher education system that fosters the mobility and equality of progressive ideals, policy debates must come together to address the unequal risks that our economy creates for Black families. Given its economic and social value, higher education should be seen as a public good, and we must recognize that public investment can build a dynamic, well-rounded, innovative population that benefits all of us. A comprehensive, race-conscious higher education policy cannot be complete without a universally accessible, public higher education system.

Higher education policy alone cannot close the racial wealth gap. Narrowing racial wealth inequalities requires a range of economic policies to help Black families build wealth, including reassessing how we finance higher education. It is vital that researchers, policymakers, and practitioners appreciate the ways in which racial inequality in our economy shows up in the higher education system—and just as vital that those focused on reducing and eliminating racial wealth inequality help guide higher education policy to help achieve that goal.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Julie Margetta Morgan, Andrea Flynn, and Anne Price for their comments and insight. Roosevelt staff Kendra Bozarth, Matthew Hughes, and Victoria Streker all contributed to this project, as did Alex Edwards and Peter Granville at The Century Foundation.

Download Appendixes Here

Notes

- Zack Friedman, “Student Loan Debt Statistics in 2019: A $1.5 Trillion Crisis,” 25 February 2019, Forbes, https://www.forbes.com/sites/zackfriedman/2019/02/25/student-loan-debt-statistics-2019/#63c388a2133f.

- Venoo Kakar, Gerald Eric Daniels, Jr., and Olga Petrovska, “Does Student Loan Debt Contribute to Racial Wealth Gaps? A Decomposition Analysis,” 21 November 2018, Journal of Consumer Affairs (forthcoming), https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3094076.

- Andrea Flynn, et al., “Rewrite the Racial Rules: Building an Inclusive American Economy,” June 2016, The Roosevelt Institute, https://rooseveltinstitute.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/Structural-Discrimination-Final.pdf.

- The Roosevelt Institute’s “Rewrite the Racial Rules: Building an Inclusive American Economy” explores this system, reporting that the average Black K–12 student attends a school that is 49 percent Black, and that “48 percent of all Black children attended high-poverty schools, as compared to only 8 percent of white children” (Flynn, et al. p. 35; see also: Richard D. Kahlenberg, Halley Potter, and Kimberly Quick, “A Bold Agenda for School Integration,” 8 April 2019, The Century Foundation, https://tcf.org/content/report/bold-agenda-school-integration/).

- Flynn, et al., p. 38-41.

- In 2016–2017, the four-year graduation rate for white students (89 percent) was 11 percent higher than it was for Black students (“Public High School Graduation Rates,” May 2019, National Center for Education Statistics, https://nces.ed.gov/programs/coe/indicator_coi.asp.)

- Edwin H. Litolff, III, “Higher Education Desegregation: An Analysis of State Efforts in Systems Formerly Operating Segregated Systems of Higher Education,” 2007, Louisiana State University Doctoral Dissertations, p. 13, https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=4133&context=gradschool_dissertations.

- Litolff, p. 15.

- Ira Katznelson, When Affirmative Action Was White (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2005), p. 128-132.

- Katznelson, 132. In 1946, in Southern states 51 percent of students at white higher education institutions were veterans, but at Black institutions, only 30 percent of students were veterans.

- Sara Garcia, “Gaps in College Spending Shortchange Students of Color,” 5 April 2018, Center for American Progress, https://www.americanprogress.org/issues/education-postsecondary/reports/2018/04/05/448761/gaps-college-spending-shortchange-students-color/.

- Ivory A. Toldson, “The Funding Gap between Historically Black Colleges and Universities and Traditionally White Institutions Needs to be Addressed,” The Journal of Negro Education 85, no. 2 (Spring 2016),

https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.7709/jnegroeducation.85.2.0097?seq=1#page_scan_tab_contents. - Krystal L. Williams and BreAnna L. Davis, “Public and Private Investments and Divestments in Historically Black Colleges and Universities,” January 2019, American Council on Education & UNCF Issue Brief, p. 3, https://www.acenet.edu/news-room/Documents/public-and-private-investments-and-divestments-in-hbcus.pdf.

- Morehouse College—a private HBCU—has an endowment of about $66,000 per student compared to $340,000 per student at Cornell University (Dylan Matthews, “Morehouse’s Students Loan Forgiveness Is an Incredibly Useful Economic Experiment,” 20 May 2019, Vox, https://www.vox.com/future-perfect/2019/5/20/18632520/morehouse-college-graduation-class-size-robert-f-smith-billionaire; Darrick Hamilton, et al, “Still We Rise: The Continuing Case for America’s Historically Black Colleges and Universities,” 9 November 2015, The American Prospect, https://prospect.org/article/why-black-colleges-and-universities-still-matter).

- Monica Anderson, “A Look at Historically Black Colleges and Universities as Howard Turns 150,” 28 February 2017, Pew Research Center: Fact Tank, https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2017/02/28/a-look-at-historically-black-colleges-and-universities-as-howard-turns-150/; Krystal L. Williams and BreAnna L. Davis, “Public and Private Investments and Divestments in Historically Black Colleges and Universities,” p. 2.

- Michael Mitchell, “By Disinvesting in Higher Education, States Contributing to Affordability Crisis,” 4 October 2018, Center on Budget and Policy Priorities: Off the Charts, https://www.cbpp.org/blog/by-disinvesting-in-higher-education-states-contributing-to-affordability-crisis.

- Mark Huelsman, “Debt to Society: The Case for Bold, Equitable Student Loan Cancellation and Reform,” 6 June 2019, Demos, https://www.demos.org/research/debt-to-society#The-Destructive-Consequences-of-Debt-Financed-Higher-Education.

- https://www.newyorkfed.org/newsevents/speeches/2015/mca150416.html

- Aissa Canchola and Seth Frotman, “The Significant Impact of Student Debt on Communities of Color,” 15 September 2016, Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, https://www.consumerfinance.gov/about-us/blog/significant-impact-student-debt-communities-color/.

- Robert Shireman, “The For-Profit College Story: Scandal, Regulate, Forget, Repeat,” 24 January 2017, The Century Foundation, https://tcf.org/content/report/profit-college-story-scandal-regulate-forget-repeat/; James Surowiecki, “The Rise and Fall of For-Profit Schools,” 2 November 2015, The New Yorker, https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2015/11/02/the-rise-and-fall-of-for-profit-schools.

- Tressie McMillan Cottom, Lower Ed: The Troubling Rise of For-Profit Colleges in the New Economy (New York: The New Press, 2017), 82; Darrick Hamilton and William A. Darity, Jr. “The Political Economy of Education,” Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis Review 99, no. 1 (First Quarter 2017), https://files.stlouisfed.org/files/htdocs/publications/review/2017-02-15/the-political-economy-of-education-financial-literacy-and-the-racial-wealth-gap.pdf.

- Today, almost 74 percent of revenues at for-profit, Title IV-eligible schools come from federal student aid (William Beaver, “The Rise and Fall of For-Profit Higher Education,” January-February 2017, American Association of University Professors, https://www.aaup.org/article/rise-and-fall-profit-higher-education#.XMzU3dNKiqQ; Vivien Lee and Adam Looney, “Understanding the 90/10 Rule: How Reliant are Public, Private, and For-Profit Institutions on Federal Aid,” January 2019, The Brookings Institution, https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/ES_20190116_Looney-90-10.pdf; David J. Denning, Claudia Goldin, Lawrence F. Katz, “The For-Profit Postsecondary School Sector: Nimble Critters or Agile Predators, December 2011, National Bureau of Economic Research Working Papers, p. 9, https://www.nber.org/papers/w17710.pdf).

- Surowiecki, “The Rise and Fall of For-Profit Schools.”

- For Profit Colleges by the Numbers,” February 29018, Center for Analysis of Postsecondary Education and Employment,” https://capseecenter.org/research/by-the-numbers/for-profit-college-infographic/.

- Mark Huelsman, “Betrayers of the American Dream: How Sleazy For-Profit Colleges Disproportionately Target Black Students,” 12 July 2015, The American Prospect, https://prospect.org/article/betrayers-dream.

- Julie Margetta Morgan and Marshall Steinbaum, “The Student Debt Crisis, Labor Market Credentialization, and Racial Inequality: How the Current Student Debate Gets the Economics Wrong,” 16 October 2018, Roosevelt Institute, https://rooseveltinstitute.org/student-debt-crisis-labor-market-credentialization-racial-inequality/; Alicia Sasser Modestino, Daniel Shoag, and Joshua Ballance, “Upskilling: Do Employers Demand Greater Skill When Workers Are Plentiful?” 4 June 2019, MIT Press Journals, https://www.mitpressjournals.org/doi/abs/10.1162/rest_a_00835.

- Lisa J. Detting, et al, “Recent Trends in Wealth-Holding by Race and Ethnicity: Evidence from the Survey of Consumer Finances,” 27 September 2017, FEDS Notes, https://www.federalreserve.gov/econres/notes/feds-notes/recent-trends-in-wealth-holding-by-race-and-ethnicity-evidence-from-the-survey-of-consumer-finances-20170927.htm.

- Ben Miller, “New Federal Data Show a Student Loan Crisis for African American Borrowers,” 16 October 2017, Center for American Progress, https://www.americanprogress.org/issues/education-postsecondary/news/2017/10/16/440711/new-federal-data-show-student-loan-crisis-african-american-borrowers/.

- Sara Goldrick-Rab, Robert Kelchen, Jason Houle, “The Color of Student Debt: Implications of Federal Loan Program Reforms for Black Students and Historically Black Colleges and Universities,” 2 September 2014, Wisconsin Hope Lab, p. 12, https://news.education.wisc.edu/docs/WebDispenser/news-connections-pdf/thecolorofstudentdebt-draft.pdf?sfvrsn=4.

- Sara Goldrick-Rab, Robert Kelchen, Jason Houle, “The Color of Student Debt: Implications of Federal Loan Program Reforms for Black Students and Historically Black Colleges and Universities,” p. 11. [/note

Table 1

Percentage of Students Who Took Out Federal Loans for Undergraduate Education Within 12 Years of Entering Total Public four-year institution Private non-profit four-year institution Public two-year institution Private for-profit institution White 57 60 66 46 90 Black or African American 78 87 82 62 95 Hispanic or Latino 58 65 74 40 84 All Students 60 62 68 48 89 Note: Black students borrow to attend college much more often than their white counterparts do.

Source: Center for American Progress *The Center for American Progress did not report figures for Asian, American Indian, Alaska Native, Native Hawaiian, Pacific Islander, or other race or ethic groups.

Sociologists Fenaba Addo and Jason Houle find that differences in parental wealth are a key factor in driving the greater use of student loans to finance education by Black students (and the greater difficulty Black students have paying off their loans, discussed later).30 As will be discussed later in the paper, differences in enrollment patterns—and particularly the disproportionate concentration of Black students at for-profit schools—also play a key role in differences in borrowing levels by Black and white students (Fenaba Addo, Jason Houle, and Daniel Simon, “Young Black and (Still) in the Red: Parental Wealth, Race, and Student Loan Debt,” Race and Social Problems 8, no 1 (2016)

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6049093/#R36). - Michal Gristein-Weiss, et al., “Racial Disparities in Education Debt Burden Among Low- and Moderate- Income Households,” Children and Youth Services Review 65, June 2016, https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0190740916301220.

- Fenaba Addo, Jason Houle, and Daniel Simon, “Young Black and (Still) in the Red: Parental Wealth, Race, and Student Loan Debt.”

- Fenaba Addo, “Parents’ Wealth Helps Explain Racial Disparities in Student Loan Debt,” 29 March 2019, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, https://www.stlouisfed.org/publications/in-the-balance/2018/parents-wealth-helps-explain-racial-disparities-in-student-loan-debt.

- Michelle Singletary, “Your Child Probably Won’t Get a Full Ride to College,” 16 October 2019, The Washington Post, https://www.washingtonpost.com/business/2018/10/16/odds-your-child-getting-full-ride-college-are-low/?utm_term=.438e46e27798.

- William Darity, Jr, et al, “What We Get Wrong About Closing the Racial Wealth Gap,” April 2018, Samuel DuBois Cook Center on Social Equity and Insight Center for Community Economic Development, https://socialequity.duke.edu/sites/socialequity.duke.edu/files/site-images/FINAL%20COMPLETE%20REPORT_.pdf; Yunju Nam, et al., “Bootstraps are for Black Kids: Race, Wealth and the Impact of Intergenerational Transfers on Adult Outcomes,” September 2015, Insight Center for Community and Economic Development, http://www.insightcced.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/07/Bootstraps-are-for-Black-Kids-Sept.pdf.

- Rachel Fishman, “The Wealth Gap Plus: How Federal Loans Exacerbate Inequality for Black Families,” May 2018, New America, https://www.newamerica.org/education-policy/reports/wealth-gap-plus-debt/part-i-intergenerational-higher-education-debt/.

- The extent to which Black parents have come to rely on Parent PLUS Loans was revealed in 2012 when the Department of Education tried to tighten access to the Parent PLUS Loan program. As we have seen, HBCUs are historically underfunded and cater to students with less access to funding. These students and their parents rely heavily on debt to make up for what they and their schools lack in wealth. When the Parent PLUS Loan program tightened their lending requirements, HBCUs found their revenue stream dramatically cut—so much so that they successfully lobbied to reverse the policy changes and ensure that families with bad credit records still had access to PLUS loans. This activism helped maintain the availability of a program that gives students from low-income families access to higher education but did nothing to reduce the risks the program poses for these families (Fishman, “The Wealth Gap Plus”).

- Katrina Walsemann and Jennifer Ailshire, “Student Debt Spans Generations: Characteristics of Parents Who Borrow to Pay for Their Children’s College Education,” The Journals of Gerontology: Series B, 72 (6), November 2017: 1084–1089.

- Jason Houle and Fenaba Addo, “Racial Disparities in Student Debt and the Reproduction of the Fragile Black Middle Class,” Sociology of Race and Ethnicity (2018), https://doi.org/10.1177/2332649218790989.

- Dubravka Ritter and Rajeev Darolia, “Working Paper No. 17-38: Strategic Default Among Private Student Loan Debtors: Evidence from Bankruptcy Reform,” 2017, Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia,

https://www.philadelphiafed.org/-/media/research-and-data/publications/working-papers/2017/wp17-38.pdf?la=en. - William Darity, Jr, et al., “What We Get Wrong About Closing the Racial Wealth Gap.”

- Brian Bridges, “African Americans and College Education by the Numbers,” 29 November 2018, UNCF,

https://www.uncf.org/the-latest/african-americans-and-college-education-by-the-numbers - Kavya Vaghul and Marshall Steinbaum, “How the Student Debt Crisis Affects African Americans and Latinos,” 17 February 2016, Washington Center for Equitable Growth, https://equitablegrowth.org/how-the-student-debt-crisis-affects-african-americans-and-latinos/.

- “Growing Gaps in College-Attainment Rates,” 2 May 2017, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis: On the Economy Blog, https://www.stlouisfed.org/on-the-economy/2017/may/growing-gaps-college-attainment-rates.

- Robert Kelchen, “A Look at Pell Grant Recipients’ Graduation Rates,” 25 October 2017, Brookings: Brown Center Chalkboard, https://www.brookings.edu/blog/brown-center-chalkboard/2017/10/25/a-look-at-pell-grant-recipients-graduation-rates/; Robert Kelchen, “Downloadable Dataset of Pell Recipient Graduation Rates,” 27 October 2017, robertkelchen.com, https://robertkelchen.com/tag/ipeds/.

- Rachel Baker, Daniel Klasik, Sean F. Reardon, “Race and Stratification in College Enrollment Over Time,” 28 January 2018, AREA Open, https://doi.org/10.1177/2332858417751896.

- Mark Huelsman, “The Racial and Class Bias Behind the ‘New Normal’ of Student Borrowing,” Demos (2015)

https://www.demos.org/sites/default/files/publications/Mark-Debt%20divide%20Final%20(SF).pdf - Jennie H. Woo, et al., “Repayment of Student Loans as of 2015 Among 1995-96 and 2003-04 First Time Beginning Students,” October 2017, U.S. Department of Education, NCES 2018-410, https://nces.ed.gov/pubs2018/2018410.pdf.

- Brandon Jackson and John Reynolds, “The Price of Opportunity: Race, Student Loan Debt, and College Achievement,” 2013, Florida State University Libraries, Department of Sociology, Faculty Publications, https://fsu.digital.flvc.org/islandora/object/fsu:210550/datastream/PDF/view; Dongbin Kim, “The Effects of Loans on Students’ Degree Attainment: Differences by Student and Institutional Characteristics,” Harvard Educational Review 77, no. 1 (Spring 2007), https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ765963.

- Cottom, Lower Ed, p. 21-22 , 82-83, 124-131; Genevieve Bonadies, et al., “For-Profit School’s Predatory Practices and Students of Color: A Mission to Enroll Rather than Educate,” 30 July 2018, Harvard Law Review Blog, https://blog.harvardlawreview.org/for-profit-schools-predatory-practices-and-students-of-color-a-mission-to-enroll-rather-than-educate/.

- Huelsman, “Betrayers of the American Dream

- Adam Looney and Constantine Yannelis, “A Crisis in Student Loans? How Changes in the Characteristics of Borrowers and in the Institutions they Attended Contributed to Rising Loan Defaults,” Fall 2015, Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/LooneyTextFall15BPEA.pdf, p. 1.

- Looney and Yannelis, “A Crisis in Student Loans?”, p.2.

- Louise Seamster and Raphael Charon-Chenier, “Predatory Inclusion and Education Debt: Rethinking the Racial Wealth Gap,” Social Currents 4, no. 3 (2017), https://www.researchgate.net/publication/315114639_Predatory_Inclusion_and_Education_Debt_Rethinking_the_Racial_Wealth_Gap/citation/download.

- Seamster and Charon-Chenier, “Predatory Inclusion and Education Debt.”

- Huelsman, “Debt to Society.”

- Judith Scott-Clayton, “What Accounts for Gaps in Student Loan Default and What Happens After,” 2018, Economic Studies at Brookings, https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/Report_Final.pdf.

- Huelsman, “Debt to Society.”

- Miller, “New Federal Data Show a Student Loan Crisis for African American Borrowers,” 16.

- Margetta Morgan and Steinbaum, “The Student Debt Crisis, Labor Market Credentialization, and Racial Inequality: How the Current Student Debate Gets the Economics Wrong,” p. 22.

- Seamster and Charon-Chenier, “Predatory Inclusion and Education Debt,” p. 200.

- “Median Weekly Earnings by Educational Attainment in 2014,” 23 January 2015, Bureau of Labor Statistics, The Economics Daily, https://www.bls.gov/opub/ted/2015/median-weekly-earnings-by-education-gender-race-and-ethnicity-in-2014.htm.

- Janelle Jones and John Schmitt, “A College Degree is No Guarantee,” May 2014, Center for Economic and Policy Research, http://cepr.net/documents/black-coll-grads-2014-05.pdf.

- Adam Harris, “White College Graduates are Doing Great with their Parents Money,” 20 July 2018, The Atlantic, https://www.theatlantic.com/education/archive/2018/07/black-white-wealth-gap-inheritance/565640/.

- Scott-Clayton, “What Accounts for Gaps in Student Loan Default and What Happens After

- Judith Scott-Clayton and Jing Li, “Black-White Disparity in Student Loan Debt More than Triples After Graduation,” 20 October 2016, Brookings, https://www.brookings.edu/research/black-white-disparity-in-student-loan-debt-more-than-triples-after-graduation.

- Scott-Clayton and Li, “Black-White Disparity in Student Loan Debt More than Triples After Graduation.”

- Robert Kelchen, “Examining Trends in Graduate Student Debt by Race and Ethnicity,” 15 May 2018, robertkelchen.com, https://www.higheredtoday.org/2018/05/29/analysis-traces-trends-graduate-student-debt-race-ethnicity/.

- Scott-Clayton and Li, “Black-White Disparity in Student Loan Debt More than Triples After Graduation.”

- Lorelle L. Espinosa, et al., “Race and Ethnicity in Higher Education: A Status Report,” 2019, American Council on Education, https://www.equityinhighered.org/.

- William Darity, Jr, et al, “What We Get Wrong About Closing the Racial Wealth Gap”; Darrick Hamilton, et al, “Umbrellas Don’t Make it Rain: Why Studying and Working Hard Isn’t Enough for Black Americans,” April 2015, The New School, Duke Center for Social Equity, Insight Center for Community and Economic Development, http://www.insightcced.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/08/Umbrellas_Dont_Make_It_Rain_Final.pdf.

- Jhumpa Bhattacharya, et al. “Women, Race & Wealth,” January 2017, Samuel DuBois Cook Center on Social Equity and Insight Center for Community Economic Development, http://www.insightcced.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/January2017_ResearchBriefSeries_WomenRaceWealth-Volume1-Pages.pdf.

- Jhumpa Bhattacharya, Anne Price, Fenaba Addo, “Clipped Wings: Closing the Wealth Gap for Millennial Women,” 2019, Asset Funders Network, https://assetfunders.org/wp-content/uploads/AFN_2019_Clipped-Wings_Brief.pdf.

- Houle and Addo, “Racial Disparities in Student Debt and the Reproduction of the Fragile Black Middle Class.”

- Addo, “Parents’ Wealth Helps Explain Racial Disparities in Student Loan Debt.”

- Addo, Houle, and Simon, “Young Black and (Still) in the Red: Parental Wealth, Race, and Student Loan Debt.”

- Kakar, Gerald Eric Daniels, Jr., and Olga Petrovska, “Does Student Loan Debt Contribute to Racial Wealth Gaps? A Decomposition Analysis.”

- Thomas Shapiro, Tatjana Meschede, Sam Osro, “The Roots of the Widening Racial Wealth Gap,: Explaining the Black-White Economic Divide, February 2013, Institute on Assets and Social Policy, https://heller.brandeis.edu/iasp/pdfs/racial-wealth-equity/racial-wealth-gap/roots-widening-racial-wealth-gap.pdf.

- Marshall Steinbaum, “Student Debt and Racial Wealth Inequality,” 7 August 2019, Jain Family Institute, https://phenomenalworld.org/content/2-higher-education-finance/1-student-debt-racial-wealth-inequality/student_debt_and_racial_wealth_inequality_final_7-19-19.pdf; Louise Seamster, “How Should We Measure the Racial Wealth Gap? Relative vs. Absolute Gaps in the Student Debt Forgiveness Debate,” 27 July 2019, Scatterplot, https://scatter.wordpress.com/2019/07/27/how-should-we-measure-the-racial-wealth-gap-relative-vs-absolute-gaps-in-the-student-debt-forgiveness-debate/.

- Michelle Jamrisko and Ilan Kolet, “Cost of College Degree in U.S. Soars 12 Fold: Chart of the Day,” 15 August 2012, Bloomberg, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2012-08-15/cost-of-college-degree-in-u-s-soars-12-fold-chart-of-the-day.