Relations between Iran and its Gulf Arab neighbors are at their lowest point since the 1979 Islamic Revolution, with little interaction between both sides of the Persian Gulf. Despite President Hassan Rouhani’s desire to make engagement of Iran’s Gulf Arab neighbors a major tenet of his foreign policy,1 no significant progress has been made in this regard. Rather, the Gulf Arab states have made unilateral Iranian withdrawal from all Arab affairs a precondition to any talks—something Iran cannot accept,2 though it is willing to have a dialogue on regional security. Meanwhile, Tehran continues to steadily increase its involvement in the region. The Trump administration’s “maximum pressure” Iran policy3 has worsened the situation by bolstering countries such as Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates (UAE), whose leadership continues to expand the list of preconditions to dialogue. All the while, the proxy war in Yemen between Tehran on one side, and Riyadh and Abu Dhabi on the other, continues to expand.4 Such a state of high tension leaves too much room for miscalculation and potential for war: it is not sustainable.

Many of the reasons for the rivalry are structural in nature, such as size, population, and the geographical placement of cities, making them long-standing features of the region and unlikely to disappear, regardless of who is in power in Tehran. But the rivalry can be managed.

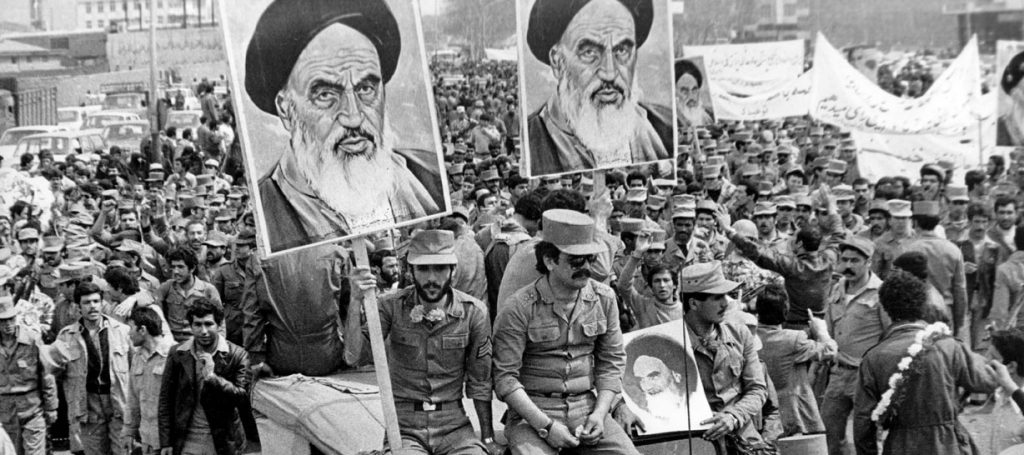

In order to understand the rivalry in the Persian Gulf, its roots must be examined. After the 1979 Islamic Revolution, the very nature of the new regime in Tehran was threatening. But even under the previous government of Reza Shah, Iran was a threat because of its desire to be the region’s hegemon. Many of the reasons for the rivalry are structural in nature, such as size, population, and the geographical placement of cities, making them long-standing features of the region and unlikely to disappear, regardless of who is in power in Tehran. But the rivalry can be managed. Both sides must take unilateral steps to diminish tensions. For their part, the United States and its European allies must leverage their good relations with either side of the Gulf to bring them to the table and help them establish a forum for regular dialogue.

Iran and the Gulf Arabs States—Natural Rivals

Iran and the Gulf Arab states compete on several fronts, including but not limited to political, sectarian, and religious fronts, as well as in their respective visions of international security.

Iran possesses several favorable characteristics that strengthen its standing vis-a-vis its Gulf Arab neighbors. It is a large country, with a population above eighty million, of which a majority is below the age of twenty-five.5 Iran’s young population is tech-savvy, outward looking, and has no experience of any other government than the Islamic Republic. The country is resource-rich and sits in a strategically significant area in the region: its long coastline on the southern edge touches the Persian Gulf and the Straits of Hormuz. This gives Tehran strategic control over the waterways through which much of the world’s oil travels. Historically, Iran’s continued independence from direct colonial control and its experience of the Iran–Iraq War fostered a belief in the principle of self-sufficiency and independence from any kind of foreign influence—quite unlike Iran’s Gulf Arab neighbors, who depend on foreign assistance for their security. Finally, and significantly in the case of a military conflict, most major Iranian cities are located inland, deep within the country.

Saudi Arabia and its Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) allies, however, are in a different situation. Their native populations are small, their access to Persian Gulf waters are limited (Saudi Arabia), and their capital cities are all coastal and facing Iran, leaving them vulnerable to potential attack. In addition, Saudi Arabia’s main wealth-generating sector—the oil industry and its refineries—is vulnerable because it is mainly located in the unstable, majority-Shia quarters in the country’s Eastern Province.

Such differences are structural in origin rather than dependent on the political leadership in each country, and they naturally limit security cooperation between Iran and its neighbors.

In 1979, the region saw the addition of a new dimension to the rivalry: religion.

In 1979, the region saw the addition of a new dimension to the rivalry: religion. As the home to Mecca and Medina, Saudi Arabia aspires to lead all Muslims. The Islamic Revolution put in place in Iran an alternative, Muslim-led government that aimed to present itself as a different viable model for the region—and also to lead all Muslims. When Supreme Leader Ayatollah Khomeini came to power, he attacked the very foundations of Saudi Arabia and its claim to leadership of Islam. He believed the Al Saud ruling family to be corrupt and not worthy of being the custodian of Islam’s holiest sites. The November 1979 occupation of the Grand Mosque by Juhayman al-Utaibi, who called for the overthrow of the Saudi leadership, further fed into Khomeini’s rhetoric questioning the legitimacy of the Al Saud family. Ayatollah Khomeini sought to discredit the Al Sauds and their religious legitimacy, all the while trying to downplay the sectarian dimensions of the dispute, which would compromise Iran’s ability to portray itself as the leader of all Muslims.

Nevertheless, sectarianism became a prominent factor in the rivalry. While the majority of the Gulf Arab populations are Sunni, Iran is majority Shia. While this division in Islam has always existed, the divide between the Shias and the Sunnis intensified after the 1979 revolution. Ayatollah Khomeini’s desire to lead the Muslim world led Tehran to funnel money and assistance to Shia groups around the region to organize themselves and push for Islamic revolutions in their own states.6 To the Sunnis, this proved that Shias, under Iranian leadership, had “designs on Mecca and Medina.”7 But in fact, while the region’s Shias welcomed the Iranian revolution for its emboldening effect, they were by no means eager for the idea of “Iranian overlordship.”8 The region’s Shias are not a monolith, and are not led by a single authority.9 Some Shia—including Ayatollah Ali al Sistani, the Iranian Shia marja10 in Iraq and the head of a number of seminaries in Najaf, and Hezbollah, Iran’s proxy in Lebanon—began highlighting unity in Islam and downplaying sectarianism after the Iran–Iraq War. Regardless, the Gulf Arab states (and many in the West) view Iranian actions in the region through a sectarian prism, and Iran does not help itself.11 Some in the Gulf Arab states even believed that Iran had created ISIS in order to wage a sectarian war against the Gulf Arabs.12 The Gulf Arab states led by Saudi Arabia, in turn, responded with their own anti-Shia narrative,13 further entrenching the divide.

The Gulf Arab states (and many in the West) view Iranian actions in the region through a sectarian prism, and Iran does not help itself.

The internal security dilemmas faced by these countries have also exacerbated the divide. Any move a country made to increase its own security would necessarily be perceived as an act of aggression toward the others, requiring a response.14 In addition, foreign policy decisions in the region are often a function of internal politics, rather than external threats. Leaders on both sides of the rivalry find it essential to identify an external enemy to focus on so as to distract from any looming internal societal and economic problems, and to strengthen the ruling class’s grip on power. In the Gulf Arab states, there is a tendency to inflate the Iranian threat—something that Iran frequently plays into. For example, in 2014, Ali-Reza Zakani, a member of Iran’s parliament, boasted that Tehran controlled four Arabs capitals15—a statement that was far from the truth, but repeated by all Gulf Arab outlets.

Neither side understands the other side’s political system, and both sides criticize each other’s systems and lack of respect for the democratic rights of their people.

In addition, the very nature of the governmental systems on each side of the divide places them in opposition to one another. The Gulf Arab states are monarchies, with tribal societies and rentier states, while Iran is a religious state with a fast moving, multi-layered political system, under the guardianship of the Supreme Leader. The leadership in the Gulf Arab states regularly point out that it is difficult for them to engage with Iranian officials because Iran does not speak with one voice, and that the Iranian representatives with whom they negotiate are not always in a position to deliver on their promises16—something that is not entirely untrue. Neither side understands the other side’s political system, and both sides criticize each other’s systems and lack of respect for the democratic rights of their people. For example, in January 2018, a Saudi foreign minister called the Islamic Republic a “vision of darkness,”17 and, more recently, called for the international community to help stop Iranian human rights violations.18

Finally, Iran and its Gulf Arab neighbors have opposing perspectives on how to guarantee regional security. The Gulf Arab states believe in internationalizing regional security: that is, maximizing the number of foreign powers with a stake in the security of the Persian Gulf region.19 Furthermore, while eager to diversify their security providers and build their self-sufficiency, the Gulf Arab states believe that any possibility of building a collective security system that excludes the United States is out of the question. Meanwhile, Iran wants to rid the region of foreign powers, particularly the United States. After the Islamic Revolution, Ayatollah Khomeini repeatedly called for independence from foreign influence in Iran and the region, elaborating a “Neither East nor West” policy.20 Today, this policy objective remains in effect, with Iranian officials often blaming U.S. presence in the region for much of its instability.21

Mismatched Security Perceptions

There is a mismatch in security perceptions in the Persian Gulf region: Iran is the most pressing foreign policy concern for most of its Gulf Arab neighbors, but Iran’s vision of itself and its aspirations means it is focused on issues beyond the Persian Gulf arena. Tehran is involved across the Middle East and aims to involve itself in the region’s great power dialogues and interactions. Iran’s vision of itself—that it derives legitimacy from the inside, from its history and culture, compared to the Gulf Arab states, which in Tehran’s view derive their legitimacy from less noble sources, such as the approval of foreigners and their significant wealth—feeds its desire to play in the big leagues. Iran believes that the Gulf Arab states’ lack of indigenous capability and their reliance on Western protection and arms undermines their standing. This makes Saudi Arabia and its allies unworthy opponents in Iranian eyes. As a result, Iran’s regional foreign policy has not been constructed around a potential Saudi or Gulf Arab threat. Tehran would, without a doubt, be involved in every arena it is currently engaged in in the region, regardless of Saudi Arabia and the smaller Gulf states’ presence.22

But following events in January 2016, Iran has been forced to somewhat reassess this disregard for its Gulf Arab neighbors, and divert some of its focus to its immediate neighborhood. During that month, Saudi Arabia hanged noted Shia opposition figure Sheikh Nimr, which led to an uproar in Iran and to the looting of the Saudi embassy in Tehran.23 The aggressive rhetorical response to the looting from Iran’s Gulf Arab neighbors brought the tensions to the attention of the Iranian public, which in turn became increasingly anti-Saudi. As these events unfolded, the Trump administration continued to bolster the Gulf Arab states while pursuing a “maximum pressure” campaign on Iran—which only further intensified the war of words between Iran and its neighbors, and sparked a new desire on the part of the Gulf Arab states to stand up for themselves in regional conflicts, elevating them as a source of concern for Tehran.24

What Does This Mean for Today?

The structural aspects of the rivalry between Iran and the Arab Gulf states transcend the political elite on either side: while different ruling personalities have helped worsen or improve relations, the tension will not disappear with a change in government. The rivalry is a function of structural factors that cannot be erased or solved. Today, tensions are at an all-time high—an unsustainable and delicate balance that can easily slip into more direct confrontation. It is essential to take the necessary steps to manage these tensions.

Despite their differences, at times the Gulf Arab states and Iran have had successful dialogue when it was in their mutual interest. After eight years of the devastating Iran–Iraq War and the death of Supreme Leader Ayatollah Khomeini, the Islamic Republic’s focus on spreading revolutionary ideals slowed down.25 Instead, a more pragmatic Islamic Republic, represented by President Ali Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani, focused on securing the state and preserving its interests. Rafsanjani spearheaded a foreign policy based on realpolitik and aimed at safeguarding Iran’s interests and borders,26 and sought to reestablish ties with Iran’s Gulf Arab neighbors. Reformist president Mohammad Khatami (1997–2005) expanded on his predecessor’s foreign policy goal of partial normalisation by outlining a “dialogue among civilizations.” This resulted in a thaw in Iran’s relations with its neighbors. While the Gulf Arab states were sceptical of this initiative,27 Saudi Arabia reciprocated Iran’s outreach by attending the Islamic Summit in Tehran in December 1997. At the time, the two countries had a mutual interest in overcoming their differences in order to work out a plan to stabilize falling oil prices. Again, this time in 2016, Iran and Saudi Arabia reportedly coordinated to help resolve the political crisis in Lebanon, where Hezbollah, an Iranian proxy, and Saad Hariri, backed by Saudi Arabia, both offered their support to Christian candidate Michel Aoun to win the Lebanese presidential election, ending a two-year political stalemate.28 Both sides have also held discussions on areas of joint concern that they felt were too important to ignore, such as the Hajj pilgrimage. These instances demonstrate that Iran and its neighbors have been able to put aside their differences to overcome disagreements in the past, but the recent escalation of tensions have complicated matters. Today, the Iranian public is less receptive to the increasingly unpopular idea of dialogue with their neighbors, especially as Saudi Arabia and its allies have increased their anti-Iran rhetoric and threatened to bring the struggle for regional hegemony to Iran—hinting at war.29 Meanwhile, distrust of Iran and its involvement in the region is growing within Gulf Arab societies who have long painted their neighbor as the reason for insecurity in the region.30

Dialogue between Iran and the Gulf Arab states can only be successful if the withdrawal of Iran’s involvement in Arab affairs is the subject of talks rather than a precondition to them.

Dialogue between Iran and the Gulf Arab states can only be successful if the withdrawal of Iran’s involvement in Arab affairs is the subject of talks rather than a precondition to them. Iran will never accept a unilateral withdrawal from regional fora, which it believes it is entitled to be involved in prior to any dialogue or negotiation. High-level, official discussions invite scrutiny and pressure, so both sides should instead maximize opportunities for low- and mid-level officials, as well as non-officials, to meet regularly. Discussion should begin with low-hanging fruit: areas where one side has less at stake and can make greater concessions. Iran has offered to discuss its influence in Yemen,31 for example, and in exchange, the Gulf Arabs could be more forthcoming on the Afghanistan file.

While today this seems difficult to imagine, each side could also take unilateral steps to foster dialogue. Iran should develop a clear list of measures it would like the Gulf Arab states to take, which then could be the subject of negotiations.32 The Gulf Arab states in turn should develop a common strategy on Iran that lies closer to the middle ground—between Oman’s friendlier stance and Saudi Arabia’s fervent opposition—allowing them to engage Tehran as a stronger, unified entity.

Importantly, the Trump administration should refrain from escalatory rhetoric that exacerbates tensions between Iran and the Gulf Arab states and increases the likelihood of conflict. To date, President Trump’s “maximum pressure” campaign on Iran has not yielded any results, but it has made Iran’s neighbors more confident and more assertive, as they believe the Trump administration is firmly on their side. While this could have been useful in overcoming a previous concern the Gulf Arab states had that they could not engage Iran in dialogue from a position of weakness, today, President Trump’s almost blind support has made them too demanding in their preconditions for dialogue. Indeed, given Iran’s vision of the Gulf Arab states as a secondary security concern,33 Tehran will simply double down and ignore the need for regional dialogue until this Gulf Arab position changes. President Trump’s support has also bolstered the Gulf Arab states enough to increase their involvement in the region and be more assertive in the defense of their individual interests. The campaign in Yemen is a good example of the use of disproportionate force,34 and the growing differences in objectives between Saudi Arabia and its allies, with Riyadh focused on fighting the Houthis, including through support to other Sunni extremist groups, while Abu Dhabi focuses on fighting Islamist extremism in the south of the country.35 While the United States must counter Iran’s more nefarious activities, Tehran’s intent in the region should not be misjudged, and its capabilities should not be blown out of proportion.

Given that he wants U.S. allies to be more independent, Trump should leverage this capital to encourage the Gulf Arab states to take ownership of regional security, but not solely through guns.

President Trump holds political capital with Gulf Arab governments that President Obama had long lost after the 2011 Arab Spring and the announcement of a “Pivot to Asia” (that never came): the Gulf Arab states believed that the Obama administration had abandoned them in favor of their regional rival, Iran, and that the United States could no longer be trusted to guarantee regional security.36 President Trump however, provided new hope (despite his statements that U.S. allies would have to step up and guarantee their own security) as he pulled the United States out from the Iran nuclear deal and promised to focus his efforts instead on containing Iran. Given that he wants U.S. allies to be more independent, Trump should leverage this capital to encourage the Gulf Arab states to take ownership of regional security, but not solely through guns. Resolving regional insecurities will require dialogue between the Gulf Arab states and Iran, not conflict. The United States and its European allies could facilitate this process by mediating between the two, fostering the creation of a forum for dialogue that is inclusive. A forum for dialogue would be considerably more productive than creating additional, one-sided institutions devised by the Trump administration such as an “Arab NATO,” which simply excludes and thus targets certain countries.

Notes

- See Mohammad Javad Zarif, “What Iran Really Wants,” Foreign Affairs, May/June 2014, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/iran/2014-04-17/what-iran-really-wants; “Iran pushes for dialogue with Gulf Arab States”, Reuters, February 19, 2017, https://af.reuters.com/article/worldNews/idAFKBN15Y09P; Sanam Vakil, “Iran and the GCC: Hedging, Pragmatism and Opportunism,” Chatham House Reports, September 2018, https://www.chathamhouse.org/sites/default/files/publications/research/2018-09-13-iran-gcc-vakil.pdf.

- “A Conversation with Adel Al Jubeir,” CFR event with Saudi Foreign Minister, New York, September 26, 2018, https://www.cfr.org/event/conversation-adel-al-jubeir; author interview with Senior Emirati officials, Washington, D.C. and New York, February 2016; author interviews with officials, experts, academics, Abu Dhabi, Dubai, Muscat, Kuwait City, Doha, 2014–2017.

- “US ratchets up pressure on Iran with resumption of sanctions,” Reuters, November 5, 2018; Ariane Tabatabai, “Maximum Pressure Yields Minimum Results,” Foreign Policy March 6, 2019, https://foreignpolicy.com/2019/03/06/maximum-pressure-yields-minimum-results/.

- Robert F Worth, “How the war in Yemen became a bloody stalemate—and the worst humanitarian crisis in the world,” New York Times, October 31, 2018, https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2018/10/31/magazine/yemen-war-saudi-arabia.html; Thanassis Cambanis and Michael Hanna, “The War in Yemen is a Tragedy—and America Can End Its Complicity,” The Century Foundation, October 24, 2018, https://tcf.org/content/commentary/war-yemen-tragedy-america-can-end-complicity/.

- The World Bank population data, https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.POP.TOTL?locations=IR.

- Frederic M. Wehrey, Sectarian Politics in the Gulf From the Iraq War to the Arab Uprisings (New York: Columbia University Press, 2016), 26; Vali Nasr, The Shia Revival: How Conflicts within Islam Will Shape the Future (New York: W. W. Norton, 2006), 143; Madawi al Rasheed, “Sectarianism as Counter Revolution: Saudi Responses to the Arab Spring” in Sectarianization: Mapping the New Politics of the Middle East, ed. Nader Hashemi and Danny Poste (New York: Oxford University Press, 2017), 146–47.

- Nasr, The Shia Revival, 151.

- Ibid., 141.

- Ibid., 183.

- A marja is a Shia religious authority deemed competent to interpret the prescriptions of the sharia and make decisions. Marajeh (plural) play a key role in Shia jurisprudence and are imitated by believers.

- Author interview with Ambassador Al-Ghandi, Saudi ambassador to Qatar, Doha, May 18, 2016; author interview with Ambassador Majdi Al-Dhafiri, Kuwaiti ambassador to Iran, Kuwait City, May 24, 2016; author interview with Dr. Sami Al-Faraj, President, Kuwait Centre for Strategic Studies, Kuwait City, May 24, 2016; Al Nahyan, “Iran is threatening the stability in the Middle East,” Financial Times, January 30, 2018; Adel Bin Ahmed Al-Jubeir, “Can Iran Change?” New York Times, January 19, 2016.

- Author interview with Dr. Abdullah Al-Shayji, Chairman, Department of Political Science, Kuwait University, Kuwait City, May 25, 2016

- Al-Jubeir, “Can Iran Change?”

- Simon Mabon, Saudi Arabia and Iran:Power and Rivalry in the Middle East (London: I.B. Tauris, 2015), 25–27.

- “Expanding Influence,” Gulf News, March 3, 2015.

- Author interviews with GCC lawmakers and officials, Dubai, Abu Dhabi, Muscat, Doha, and Kuwait City, 2014–17.

- “Al Jubeir slams Iranian sectarianism,” Gulf News, January 24, 2018.

- Tovah Lazaroff, “End Iranian Violations of Human Rights, Saudi Arabia tells UNHCR,” Jerusalem Post, February 28, 2019

- Author interviews with GCC lawmakers and officials, Dubai, Abu Dhabi, Muscat, Doha, and Kuwait City, 2014–17.

- Khomeini, “We shall confront the world with our ideology”, Speech, cited in MERIP Reports No. 88, “Iran’s Revolution: The First Year” (June 1980), 22-25

- Author interviews with Iranian officials, Vienna, Geneva, Lausanne, New York, Berlin 2014–17; Ayatollah Khamenei, speech on Student’s Day, November 4, 2002, http://english.khamenei.ir/news/152/Leader-s-Speech-on-Students-Day, accessed December 17, 2017.

- The only exception to this is Iran’s involvement in the Yemen conflict. Author interviews with Iranian officials, Vienna, Geneva, Lausanne, New York, Berlin 2014–17.

- Emma Graham Harrison, “The Saudi execution of a Shia cleric has deepened Islam’s sectarian rift. Where does that leave the West?” Guardian, January 9, 2016, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2016/jan/10/iran-saudi-arabia-middle-east-war-nimr-al-nimr-execution; “Ayatollah Khamenei condemns Saudi execution of Sheikh Nimr,” Speech by Supreme Leader Ayatollah Khamenei, January 3, 2016, http://english.khamenei.ir/news/3023/Ayatollah-Khamenei-condemns-Saudi-execution-of-Sheikh-Nimr.

- Author interview with Iranian official, Berlin, Germany, June 26, 2017.

- Alidad Mafinezam and Aria Mehrabi, Iran and Its Place among Nations (Westport, Conn.: Praeger, 2008), 37.

- Ibid., 37.

- Christin Marschall, Iran’s Persian Gulf Policy: From Khomeini to Khatami (New York: Routledge, 2003), 145.

- Author interview with Iranian official, Berlin, Germany, June 26, 2017; “Tehran, Riyadh cooperation resolved Lebanon deadlock: Zarif,” Reuters, January 18, 2017, http://www.dailystar.com.lb/News/Lebanon-News/2017/Jan-18/389908-iran-wants-join-action-with-riyadh-in-syria-similarly-tolebanon.ashx; “Lebanon elects Aoun as president, ending two-year stalemate,” France 24, October 31, 2016, https://www.france24.com/en/20161031-lebanon-elects-aoun-president-ending-political-stalemate.

- Sami Aboudy, Omar Fahmy, “Powerful Saudi Prince sees no chance of dialogue with Iran,” Reuters, May 2, 2017, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-saudi-prince-iran/powerful-saudi-prince-sees-no-chance-for-dialogue-with-iran-idUSKBN17Y1FK.

- “Sir Bani Yas Forum Public Opinion 2017,” Zogby Polls, https://d3n8a8pro7vhmx.cloudfront.net/aai/pages/13778/attachments/original/1515524868/SBY2017_Final.pdf?1515524868.

- Dina Esfandiary and Ariane Tabatabai, “Yemen: An Opportunity for Iran-Saudi Dialogue?” Washington Quarterly 39, no. 2 (2016), 155–74.

- Author interview with Iranian official, New York, February 20, 2019.

- Dina Esfandiary and Ariane Tabatabai, “Saudi Arabia Cares More about Iran than Iran does about Saudi Arabia,” National Interest October 18, 2016, https://nationalinterest.org/feature/saudi-arabia-cares-more-about-iran-iran-does-about-saudi-18091.

- Iona Craig, “Bombed into famine: How Saudi air campaign targets Yemen’s food supplies,” Guardian, December 12, 2017, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2017/dec/12/bombed-into-famine-how-saudi-air-campaign-targets-yemens-food-supplies.

- William Maclean, Noah Browning, Yara Bayoumy, “Yemen counter-terrorism mission shows UAE military ambition,” Reuters, June 28, 2016, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-yemen-security-emirates/yemen-counter-terrorism-mission-shows-uae-military-ambition-idUSKCN0ZE1EA; author interviews with GCC lawmakers and officials, Dubai, Abu Dhabi, Muscat, Doha, and Kuwait City, 2014–17.

- Author interviews with officials, experts, academics, Doha, Abu Dhabi, Dubai, Kuwait City, Muscat, 2014–2017; William Maclean, “Glad to see Obama go, Gulf Arabs expect Trump to counter Iran,” Reuters, January 23, 2017, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-usa-trump-gulf-idUSKBN1571VN.