The Arab uprisings began to wither in Cairo in late November 2012. Egypt’s first truly elected president, Mohamed Morsi, decreed himself immune from judicial oversight after the supreme court threatened to outlaw, for a second time, the constituent assembly. Thousands of veterans of the 2011 Tahrir Square protests returned to the streets, condemning Morsi for packing the assembly with Islamists. Morsi claimed to be only defending the revolution from a judiciary loyal to the dictator they had united to bring down, Hosni Mubarak.1 The next summer, Morsi was ousted by the military and hundreds of his fellow Muslim Brothers were massacred at Rabaa Square.

Constitution drafting in Egypt had become a zero-sum, partisan contest that finally broke apart the revolutionary coalition and permitted the restoration of military rule.2 As one observer put it, the revolution split between Islamist democrats and elitist liberals. “Fair elections have improved the Muslim Brotherhood’s campaign skills. But it hasn’t fully committed to pluralism or to equal rights for minorities,” wrote Samer Shehata in July 2013. Their opponents may believe in minority rights and civil liberties, but they “are liberal without being democrats; they are clamoring fervently for Mr. Morsi’s ouster and want the military to intervene.”4 Political scientist Nathan Brown agrees, in a critique of the failed 2005 Iraqi constitution, imposed under American occupation. There is no technocratic fix to what is, fundamentally, a political problem. Constitutions can bridge differences best when they are debated in public, not in a closed room, and when they are the product of bargains struck by passionate, opposing interests.5

Among the countries in which the Arab uprisings took place, Tunisia stands out as the one successful constitutional exercise precisely because its constituent committee held numerous consultations with a spectrum of social groups. The Islamist Ennahda Party and secular liberals were ultimately able to strike a compromise. By contrast, Morsi’s attempt to limit participation in drafting the Egyptian constitution only mobilized popular dissent and military intervention.6 In Syria, the regime drafted a new constitution with virtually no consultation. The resulting 2012 constitution, according to a leading Syrian constitutional scholar, actually increases the vulnerability of minorities to the violation of their human rights.7

This report takes a historical perspective on the constitutional impasse in Syria and Egypt. The 2011 coalitions failed to end dictatorship for many reasons. But a fundamental cause of failure was the deep distrust between secular liberals and their better-organized Islamist partners. The regimes manipulated that distrust to weaken the revolutionary coalitions. In both countries, the liberal–Islamist cleavage is rooted in the defeat of another constitutional transition a century ago. The first—and last—truly popular liberal constitutional movements in the Arab world arose after World War I to throw off foreign rule and establish constitutional democracy. Foreign occupation broke the coalition of religious conservatives and secular liberals, and undermined their popular base.

The first—and last—truly popular liberal constitutional movements in the Arab world arose after World War I to throw off foreign rule and establish constitutional democracy.

The democratic transition attempted in 1919–20 failed not due to internal dissent, but because of foreign occupation: Britain and France colluded to destroy the Syrian Arab Kingdom because they feared the model of an Arab democracy would undermine their rule in Iraq, Palestine, and North Africa. Likewise, in Egypt, the constitutional demands made in the 1919 revolution were undermined by Britain, which orchestrated a top-down process of drafting a constitution, while the revolution’s leader, Saad Zaghlul, was in exile.

The defeat of the Syrian Arab Kingdom and 1919 revolution ushered in a new era of politics defined by opposition between elitist liberals who allied with a foreign power and a new brand of Islamist groups who rallied popular support with an anti-liberal, anti-Western agenda. The development of Islamism in the 1930s was linked in both countries by three prominent figures: Rashid Rida, publisher of a widely read magazine promoting Islamic reform; Hassan al-Banna, founder of the Egyptian Muslim Brotherhood; and Mustafa al-Siba’i, founder of the Syrian Muslim Brotherhood.

The history uncovered here suggests that compromise between secular liberals and religious leaders is not unique to the exceptional conditions in today’s Tunisia. Syrians and Egyptians had managed just such a compromise a century ago. It also suggests why the opposing parties—democratic Islamists and elitist liberals—have adopted such hardline stances: foreign intervention—not essential traits of Islam or Arab culture—is the ultimate cause of the political polarization. Finally, this history uncovers why the Syrian and Egyptian constitutions are still saddled with contradictory language on civil rights and Islam.

The legacies of events that occurred a century ago—the rise of powerful anti-liberal Islamist movements and the drafting of politicized and restrictive constitutions—still obstruct the transition to more democratic, inclusive, and pluralist polities in Syria and Egypt today. While this historical legacy is far from being the only obstacle to such a transition, it cannot be ignored. Instead, it must be confronted, by scholars and politicians alike, if the two sides are ever to meet productively across a negotiating table.

The Improbability and Inclusiveness of the 1920 Syrian Constitution

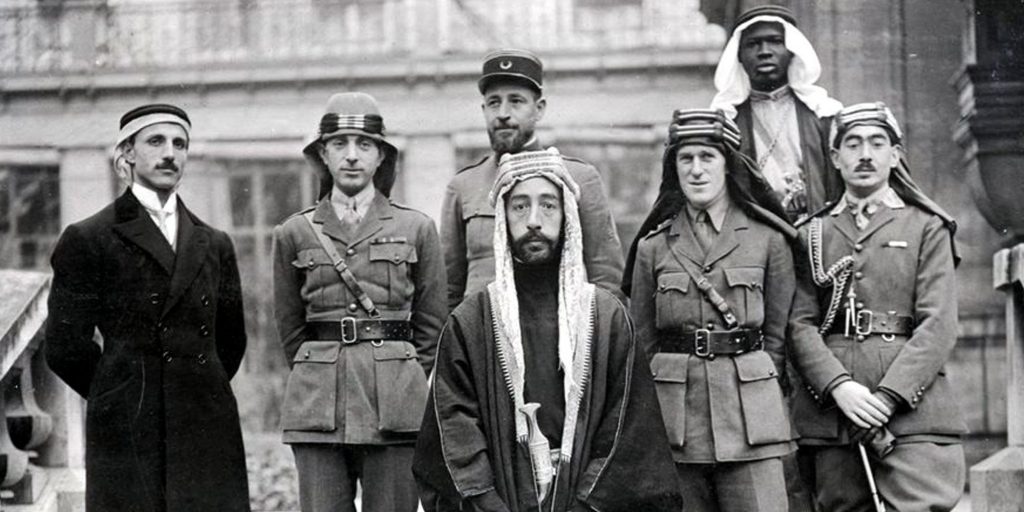

By the time the Ottoman Empire surrendered to the Allies in late October 1918, a new government had been proclaimed at Damascus. On October 5, Prince Faisal bin Hussein, a leader of the 1916–18 Arab Revolt and son of the sharif of Mecca, proclaimed an “absolutely independent, constitutional Arab government for all of Syria.” He claimed Arab rule over all of Greater Syria (comprising today’s Syria, Lebanon, Jordan, and Israel/Palestine), as promised by the British to his father. Arabia and Iraq would be Arab states in confederation with Syria.8

Greater Syria was, and always has been, home to a variety of peoples. While most of its 3.5 million residents in 1919 spoke Arabic, many used Turkish, Kurdish, Armenian, and Hebrew as their mother tongues. While more than half of them were Sunni Muslim Arabic speakers, they lived alongside a plurality of Christians, Jews, and heterodox Muslims like Druze and Alawites. Aleppo, the northernmost and largest city, had a postwar population of three hundred thousand, with a distinctively high proportion of Turkish speakers and Armenians, the latter refugees from the wartime genocide. The city’s elites still identified with the Ottomans and would not reconcile themselves to being Syrian for years to come.9 Across Greater Syria—as in all the lands of the defeated Ottoman, Russian, and Austro-Hungarian empires—a complex process of postimperial sorting took place under the pressure of the Paris Peace Conference’s deliberations, on the basis of which independence as nation-states would be awarded.

While Faisal called for the expulsion of Turks, he did so to rid Syria of enemy agents, and not with the goal of ethnic exclusion. In conditions of continued war, Turkish speakers—as opposed to their Arabic-speaking associates—were perhaps unfairly presumed to remain loyal to the yet-undefeated Ottomans. The border between Syria and Turkey would not be settled for several years. Faisal promised that the Arab nature of the regime was a strategic, umbrella term, intended to support claims of Syrian independence, not a device to exclude Kurdish and Armenian speakers. Faisal and his advisors understood that the Allies at Paris defined a “nation” worthy of self-rule as a homogeneous people occupying a contiguous territory. Faisal also reassured non-Muslims that his stature as the son of the sharif and descendant of the Prophet would not cast Syria as an Islamic state—in contrast to the Ottoman Empire, where the sultan was also the caliph, spiritual leader for all Sunni Muslims. The Greek Orthodox patriarch and chief rabbi of Damascus endorsed Faisal’s program, upon assurances that their communities would be protected.

Faisal also reassured non-Muslims that his stature as the son of the sharif and descendant of the Prophet would not cast Syria as an Islamic state—in contrast to the Ottoman Empire, where the sultan was also the caliph, spiritual leader for all Sunni Muslims. The Greek Orthodox patriarch and chief rabbi of Damascus endorsed Faisal’s program, upon assurances that their communities would be protected.

In a speech in Aleppo on November 11, 1918, Faisal defined Arabism as a political program for equality and inclusion. “I am an Arab, and I have no privilege over any other Arab,” he vowed. “I urge my Arab brothers, whatever their religion, to grasp the reins of unity and mutual understanding, to spread knowledge and to form a government that will make us proud,” he said. “I repeat what I have said everywhere, that the Arabs were Arabs before Moses and Jesus and Mohammed, and that religions command us to pursue truth and brotherhood on Earth. Therefore, anyone who sows division among Muslims, Christians, and Jews is not an Arab.”10

Politicians from across Greater Syria responded to Faisal’s call for elections to a Syrian Congress in June 1919. The Congress presented a draft constitution the next month to the American commission of inquiry, sent by U.S. president Woodrow Wilson to poll Syrians’ preferences for government. The commission reported to Paris that a majority of Syria’s residents preferred independence or very limited foreign guidance under Faisal’s Arab government; the main bloc of dissent was the Maronite Church and its followers on Mount Lebanon. On this basis, the King–Crane report recommended that Syria retain its unity, under a limited American mandate, not French. It also recommended that Lebanon retain autonomy within Syria, and that Zionist ambitions for a homeland in Palestine (called Southern Syria by Arabs) be curtailed.11

Britain and France did not welcome or even acknowledge the report. In the fall of 1919, France expanded its occupation of the coast as British troops withdrew south, leaving only the Syrian hinterland between Aleppo and Damascus under Arab rule. The two powers then began private negotiations on dividing Greater Syria between themselves.

Under pressure to accept a French mandate, the Congress declared independence and drafted a 147-article constitution in the spring of 1920. Their vigorous debates on various articles were reported in the press. Conservative Damascene elites led an opposition party of landowners, clergy, and tribal chiefs that challenged Faisal’s party. These Damascene elites were dominated by younger, ex-Ottoman officials and religious reformers like Rida, publisher of the widely read magazine The Lighthouse (or al-Manar). However, they struck compromise on several contentious issues, including the role of Islam in government, minority rights, and the balance of power between the king and parliament, and between the central government and provinces.

In July 1920, the constituent assembly presented a complete constitution that established the Syrian Arab Kingdom as a “civil representative monarchy.” In contrast to the 1909 Ottoman constitution that had governed Syria through the war, the monarch was neither the caliph nor the leader of Islam. The king, chosen as Faisal, would not be sacred. He would swear loyalty to “divine laws,” not Islamic law. Nor was Islam any longer the official state religion. By compromise, Islam was only to be the official religion of the king himself.

In effect, Syria disestablished Islam eight years before the future Turkish Republic did. Rashid Rida, the Congress president, explained the reason for this in his diary and magazine. He had mediated the compromise between secular liberals who wanted to establish a republic and conservative Muslims who wanted government based squarely on Islamic law.12 In the end, contrary to nearly every Arab constitution today, the constitution made no mention of Islamic law nor of Islam as an official religion.

In the end, contrary to nearly every Arab constitution today, the constitution made no mention of Islamic law nor of Islam as an official religion.

The Congress went further to democratize Syria by granting the legislature more power than the Ottomans had. The cabinet would be responsible to Congress, not the monarch. The Congress, not the monarch, would oversee the court system, including religious courts. Bills could be proposed by legislators, not just by the prime minister, as in Ottoman times. The prime minister was forced, after much rancor, to submit his program for approval by the Congress. Once again, Rida reminded Faisal that in a democracy the power of the executive derived from the people, and that Congress represented the people.13

The constitution also curtailed the power of elites by abolishing nomination to the Senate for life. Most senators had to be elected, and only for a term of nine years. The Senate also lost the right to vet legislation passed by the Chamber of Deputies for potential violations of the monarch’s rights or of the constitution.

Influenced by the federal model of American government (and in revolt against centralized Ottoman rule), the Congress also granted significant power to provinces to administer their local budgets. Numerous articles addressed elections to local councils.

Articles on suffrage drew a sharp and illuminating debate. Deputies agreed that every Syrian aged twenty years or more should have the right to vote in the first of a two-round election. But when several deputies proposed women’s suffrage, conservatives objected, claiming that Islamic law would not permit it. Several powerful religious leaders from Damascus stormed out of the room.

Rida again brokered a compromise—but on the grounds that Islamic law did not have jurisdiction. Matters of public interest that do not directly address religious issues must be covered by civil legislation, not by Islamic law. To women’s dismay, however, Rida suggested that the public interest was to keep the Congress united against a potential French invasion. Syria had to demonstrate its ability to rule through a modern, parliamentary government in order to uphold its claim to self-rule. If the Congress dissolved in controversy, the French would make their case that Syrians needed their tutelage under a League of Nations mandate. Rida therefore proposed that women’s suffrage be set aside. Sovereignty was the overriding public interest. Muhammad Izzat Darwazah concurred, recalling that the majority of deputies agreed that women had equal rights and that Islamic law did not prohibit their suffrage. But they also shared Rida’s concern that popular opposition organized by their opponents might undercut the Congress’ authority. So they settled the issue temporarily by using a gender-neutral pronoun in the suffrage law rather than explicitly declaring women’s right to vote. 14

Syria had to demonstrate its ability to rule through a modern, parliamentary government in order to uphold its claim to self-rule. If the Congress dissolved in controversy, the French would make their case that Syrians needed their tutelage.

The lesson Rida taught that day and in his magazine—that Islamic law should not cover all civil matters—would be lost in the rise of populist Islamism in the 1930s. Rida had foreseen that a split in the Syrian Congress would imperil a fundamental public interest: the defense of sovereignty and democratic government. In contrast, during the 2011 Arab uprisings, Islamists and liberals would split.

The Syrian Congress also introduced a new system to assure the representation of non-Muslim minorities in both chambers of Congress, at a slightly higher rate of representation than for Muslims.15 The use of the term “minority” (“al-aqaliyyah”) was new in Arabic. It was derived from the terms coined by Europeans at the 1919 Paris Peace Conference who were sorting multiple defeated empires (Russian and Austro-Hungarian, not just Ottoman) into nation-states. Syrians’ use of the term would expand in the next decade, under the French mandate.16

We have only piecemeal evidence of non-Muslims’ reaction to the constitution. Generally, Greek Orthodox patriarchs and their followers supported the regime, while Catholics followed the Maronite Church in supporting French rule. In the summer of 1920, Faisal retained two loyal Christian ministers in his cabinet, Faris al-Khuri and Yusuf al-Hakim. Shortly after July 5, when the constitution was presented in full and accepted by Congress, a majority of the administrative council of Mount Lebanon decided to join the Syrian government. Among them was the brother of the Maronite Patriarch. Habib Estefan, a prominent Maronite priest who condemned the Turks for the wartime famine, had already joined Faisal’s government. A dynamic speaker, he toured the country for the ministry of culture. In May 1920, he gave a ninety-minute speech in the conservative, Muslim town of Hama, imploring his fellow Arab patriots to support the government and defend national liberty against French domination.17

Maronite patriarch Elias Hoyek took an opposing view of French rule. Hoyek expressed shock that the March 1920 declaration of Syrian independence included coastal Lebanon. He condemned the declaration for its “anti-French spirit.” In November 1919 he secured the promise of an autonomous government of Lebanon from French premier Georges Clemenceau. The letter restated France’s commitment to protect the Christians of Lebanon, which it made after the massacres of Christians in 1860. These promises were reinforced by the French in the spring of 1920, when a delegation sent by Hoyek visited Paris.18

The French occupation set a precedent for the language of protection, and the privileging of “minorities” and sects, that directly challenged constitutionalists’ efforts to unite the full diversity of people in a regime of equal, constitutional rights. This same tension, as seen below, emerged in British-ruled Egypt.

While the 1920 Syrian constitution was written from scratch in a far more democratic and egalitarian spirit, it still owed much to its Ottoman predecessor. Constitutions were primarily claims to legal sovereignty, but they were also viewed as a vehicle for promoting a more inclusive, and less divisive, citizenry. The Ottoman constitution specifically aimed to recast non-Muslims as full citizens with equal rights, to replace the old “dhimmi” designation that subordinated them to the Muslim ruling class. Citizens were Ottomans first, Muslims, Christians, or Jews, second. This principle carried over into the post-Ottoman Syrian and Egyptian constitutions. (Like the 1920 Syrian constitution, the 1923 Egyptian constitution did not mention Islamic law as a basis of legislation.)19

The primary author of the Ottoman constitution, Midhat Pasha, expected it to assure “that a fusion be effected of the different races, and that out of this fusion should spring the progressive development of the populations, to whatever nationality and whatever religion they may belong.” Midhat transmitted these claims in 1878 to the British public, seeking their support against Russian intervention and invasion. Back then, as in 1920, the constitutions were a bid to join the modern family of nations. His successors modified the constitution in 1909 in face of renewed European pressure.20

Rida had long defended constitutionalism against the opposition of conservative Muslim clerics. He published an article in 1909 responding to their objection that Muslims should not be subject to laws promulgated by a legislature containing Christians and Jews. Rida argued that such a legislature was the expression of democracy and that democracy is the only form of government that conforms to Islamic principles. The only other option, dictatorship, violates Islam. Even in the Prophet’s time, Rida continued, God had ordered that worldly affairs be studied and addressed by qualified experts, not just Islamic scholars. The constitution they produce would conform to Islamic law if it upheld Islamic principles like justice and the injunction to promote good and prevent harm.

Rida argued that such a legislature was the expression of democracy and that democracy is the only form of government that conforms to Islamic principles. The only other option, dictatorship, violates Islam.

“It is not forbidden for Muslims to consult with others and share opinions with them. This is even recommended when it is in the interest of the nation,” he wrote. Rida felt that only fanatics could insist that Islamic scholars must decide on worldly matters like tax collection and court administration. “Times and customs change. The state and the nation have many needs and interests that did not exist in the time of imams,” he argued. “We are forced to adopt practices that fit our time” to remain a strong nation and prevent evil.21

In 1920, Faisal and the Congress aimed to persuade European liberals that they had learned the methods of modern governance while serving in parliament and in government offices in the last Ottoman decades. The mandates were intended, after all, for peoples “not yet ready” for self-rule.

The compromises they struck in drafting the constitution were a historic bid for sovereignty and respect in what Woodrow Wilson promised to be a new world order. The historic consequences of undermining that government would therefore resonate in 2011, when once again Arab resistance to dictatorship staged its claim to sovereign, liberal constitutions before the world’s television cameras and Facebook pages. As historian L. Carl Brown remarked decades ago, local politics in the Middle East has long been a global affair.22

Egypt’s Popular 1919 Revolution and Elitist 1923 Constitution

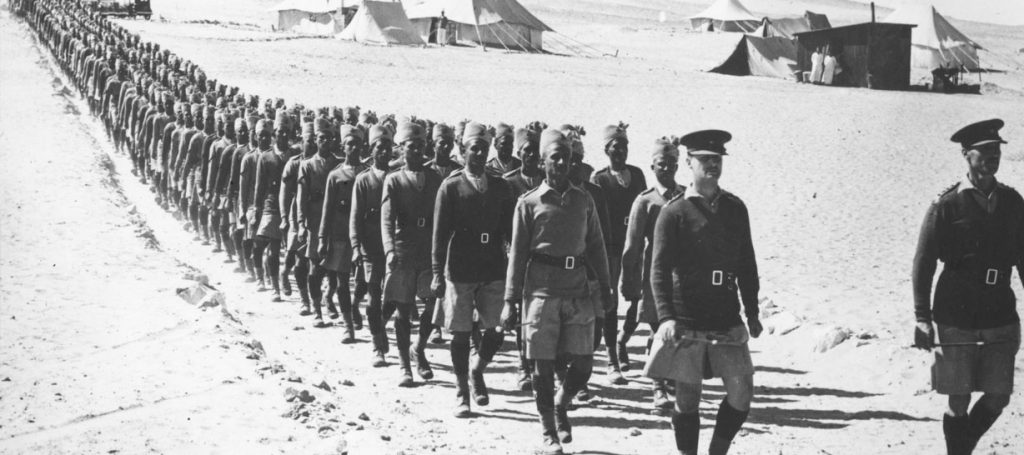

In November 1919, a charismatic Egyptian politician, Saad Zaghlul, led Egyptians in a campaign to demand independence at the Paris conference. Egypt had been occupied in 1882 by the British, who quashed an earlier constitutional revolution that the young Zaghlul had joined. Egypt remained nominally part of the Ottoman Empire until 1914. When the Ottomans entered the war against the Allies, Britain formally annexed Egypt as a protectorate. Egyptians paid dearly during the war, suffering food shortages and inflation even as they produced crops for Allied troops. An estimated one million Egyptians were recruited into a forced-labor corps to build roads and railroads and work at ports. Zaghlul and many others believed they had earned independence along with the other peoples liberated from defeated empires. Zaghlul felt he had as much right to attend the Paris Peace Conference as Faisal from Syria had.

When the British instead arrested Zaghlul in March 1919, mass demonstrations broke out in multiple cities. Both Muslims and Coptic Christians demonstrated, demanding “Egypt for the Egyptians!” Zaghlul’s Wafd Party received endorsements from both Christian and Muslim patriarchs who offered sermons at the revered Al-Azhar University. Some demonstrators carried flags, featuring both the Islamic crescent and the Coptic cross. Those flags became a symbol of the 1919 revolution in Egyptian public memory.

Some demonstrators carried flags, featuring both the Islamic crescent and the Coptic cross. Those flags became a symbol of the 1919 revolution in Egyptian public memory.

The Wafd Party emerged from broad grassroots much as Syrian nationalism did. Like the Syrians, the Egyptians demanded independence and equality under a constitutional government. Zaghlul led the movement with the same optimism that Rida and Faisal had in Syria. “It is altogether improbable that the Peace Congress, which is being held for the purpose of establishing the respect of all rights and giving freedom to all nations, will create new dominations for the strong over the weak,” he said.23

After much violence, the British negotiated a compromise for partial independence in 1922. However, they ensured that Egypt’s new constitution would not be drafted by an elected constituent assembly. It was written by a carefully selected committee that excluded Zaghlul and his populist following. The British-backed Liberal Constitutional Party had criticized Zaghlul for exploiting religious symbols to rally popular support.24

The constitution was an elitist and secular document. Its opening articles made no mention of Islam; rather, it established a “representative heritable monarchy” to rule Egyptians who “shall be equal before the law… with no discrimination… on the grounds of origin, language or religion.” Articles 12-13 assured that “freedom of belief shall be absolute” and that the state would guarantee the conduct of religious worship. As with Syria’s 1930 constitution, the king swore to uphold only the constitution and the nation’s laws, not religious laws, and school was mandatory for both boys and girls. Also similar was the reservation of military and foreign affairs to a foreign occupying power—in Egypt’s case, Britain. In contrast to 1928 Syria, the king had greater powers over the legislature.25

Copts split over political strategies for inclusion in the post-protectorate polity. While the Coptic Church advocated for special protections and proportional representation, many lay Copts joined the Wafd Party to reject their designation of a Coptic minority. Accepting minority status would have yielded the identity of the Egyptian nation to Muslims, as the majority. While the Church accepted the traditional status of non-Muslims as dhimmi clients of the Islamic state, a new generation of Egyptian Copts claimed their new status as citizens enjoying equal rights. The Copts made their choices in reaction to events in the Ottoman Empire, where the wartime government persecuted and even permitted the mass murder of non-Muslims. Some Wafdist Copts informed the British that they worried that they might be betrayed, as Christians under the Ottomans had been. Zaghlul gave them confidence by visiting the Coptic patriarch on Christmas (reports of which were censored by the British) and, once in power, by appointing Coptic Christians to the cabinet. A Coptic politician, Makram Ebeid, became secretary-general of the party.26

However, Zaghlul’s powers as prime minister were clipped by the royalist bias of the constitution and by Britain’s support for his elite opponents, who formed the Liberal Constitutional Party. Several members had helped to draft the 1923 constitution. Many believed that ordinary Egyptians, uneducated and unfamiliar with European liberalism, were not yet ready for political participation. Zaghlul, like Rida, was the charismatic politician who had managed to build a popular coalition to bridge liberal and Islamic factions. Like Rida, Zaghlul had looked in vain to liberals in Europe, and particularly the British parliament, for support. And like Rida, he was undermined by elite liberals from his own country, with foreign backing.27

The seeds of the 1925 Syrian revolt were planted when Britain and France colluded to destroy the Syrian Arab Kingdom in Damascus. Those Allied actions in Syria set loose a transnational wave of opposition to colonizers, who had hijacked the liberal language of the new League of Nations to justify their rule.

The Destruction of Syrian Arab Democracy

The Syrian constitution was read in full and approved by the Congress on July 5, 1920. Its first seven articles were then debated and individually approved over the next week. On July 14, however, France issued an ultimatum to Faisal that he accept its mandate or face invasion. Ominously, conservative Damascene elites (the same who had walked out on the women’s suffrage debate) and Christian patriarchs had begun paying visits to the French mission.28 A populist Muslim cleric, Kamil al-Qassab, rallied the city’s working classes in protest against accepting the ultimatum. Earlier, in March of that year, Qassab had, remarkably, advocated a civil government based on popular sovereignty. Now, his movement took on a heightened Islamic character.

Under popular pressure, Rida and the Congress also opposed acceptance. Faisal had always warned that freedom is taken, not given. Rida viewed the conflict in global terms, as a fight for the new world order based on the rights of peoples; to surrender would be to submit to the old imperial order. At stake, in his view and in those of others, was the future of worldwide democracy, international law, and the credibility of the League of Nations.29

But now, as French forces advanced toward Damascus, Faisal suspended Congress, jailed Qassab, and accepted the ultimatum. It did no good. On one pretext after another, the French army advanced. The city exploded in mutiny. Men and women scrambled for guns and headed to battle. French planes dropped leaflets warning Damascenes that they would punish them for any violence against Christians. Syrian leaders could not believe that their ally in World War I was now turning its guns on them. Their faith in the liberal humanism and the universality of international law crumbled.

Syrian leaders could not believe that their ally in World War I was now turning its guns on them. Their faith in the liberal humanism and the universality of international law crumbled.

As the French occupied Damascus on July 25, deputies fled to their homes in what would become the separate states of Lebanon, Palestine, Transjordan, and Syria. The most prominent politicians were forced into farther exile: Rida escaped to his family in Cairo and Faisal to Italy. Qassab eventually found refuge in what soon emerged as the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia.

The French confiscated and destroyed the archives of the Congress. “All traces of Faisal’s illegal, improvised government must disappear,” the prime minister ordered, fearing that documents might be used by Syrians to mount an appeal against the French occupation at the League of Nations.30

Within a week, the French high commissioner drew up plans to divide their portion of Greater Syria into sectarian states: “one Christian majority state [Lebanon] and two Muslim states [Aleppo and Damascus].”31 They created two autonomous zones, one on the northern coast to be governed by the Alawite sect and another in the south, designated for the Druze.

Rida did not yet lose his faith in the liberal principles of the postwar peace. A year later, in 1921, he traveled to Geneva with a delegation named the Syro-Palestinian Congress to file an appeal with the League of Nations against the French Mandate. They submitted a petition arguing that the French invasion had violated the spirit of the mandates set out in the League of Nations’ charter, which stipulated that they should be established with the consent of the people. Instead of offering limited and temporary guidance to a sovereign people, France was ruling Syria like a conquered colony.

“It does not befit the honor of this League, which President Wilson proposed to include all civilized nations for the good of all human beings … nor the honor of its principles and its intended goals, for it to be used by the two colonial states,” Rida protested to the president of the League Assembly. “These states seek to use this Assembly to secure, in the name of a mandate, the subjugation of peoples.”

In a second letter signed “former President of the Damascus Constituent Assembly,” Rida appealed directly to the French delegation to the League of Nations. “France should recognize that Syria is worthy of freedom and independence, and that the Syrian people are fit for self-government,” he wrote. The people of the country should form their government, which could then conclude a treaty of alliance with France.32 Rida maintained the posture of a world citizen deserving of the right to self-determination that Wilson had promised.

Rida feared that the Allied occupation of Arab lands would “ignite the fires of war in both the West and the East.” He wrote to readers of his magazine: “I met liberals in Geneva and elsewhere” who don’t believe their leaders’ slanders against Muslims or their pretensions “to protect Eastern Christians from their fanaticism.”33

Michel Lutfallah, the Lebanese Christian president of the Syro-Palestinian Congress, predicted war if the League approved the French mandate in Syria. “It is now evident that imperialists are making a parody of your noble principles in Syria, making mandated people enslaved colonies,” he told The New York Times.34 The article convinced Woodrow Wilson to authorize, belatedly, publication of the King–Crane commission’s report on Syria.

“If European Liberals deny this appeal, or if they are unable to establish peace between East and West, then Eastern national leaders will understand that the League of Nations has agreed to serve as the evilest instrument that has ever existed on Earth,” Rida wrote to his readers in November 1922. “The result will be the destruction of Europe.”

But in July 1922, the League Council voted to confirm the mandates. The defeat hit Rida hard. He and Lutfallah filed an appeal to the League Assembly. “If European Liberals deny this appeal, or if they are unable to establish peace between East and West, then Eastern national leaders will understand that the League of Nations has agreed to serve as the evilest instrument that has ever existed on Earth,” Rida wrote to his readers in November 1922. “The result will be the destruction of Europe.”35

The Rise of Anti-Liberal Islamism in Syria and Egypt

Syria broke out into armed revolt in 1925; it took the French two years and a brutal campaign of aerial and artillery bombardment to quash it. They displayed corpses of rebels in downtown Damascus, just as the hated Turks had done in World War I. In 1928 nationalist leaders agreed to elections for a new constituent assembly. Factions that had united during the revolt now split in the wake of defeat.

The elections deepened a political divide that in 1920 Rashid Rida had endeavored to prevent—between nationalist urban notables and pro-French religious, tribal, and rural leaders. Differences that were once tacit, soothed by Rida’s mediation, now broke out into public. The religious deputies who had stormed out of the Congress during the 1920 women’s suffrage debate had since moved into the pro-French camp. Their leader was the French-appointed prime minister Taj al-Din al-Hasani, the son of an eminent Muslim imam. Hasani campaigned against nationalists aligned with Hashim al-Atassi (Faisal’s former prime minister) casting them as anti-religion. Religious activists mounted street attacks on women who wore Western dress, while preachers condemned proposals to permit women to unveil. These same activists had also organized campaigns against French schools and co-education.

Because they were better organized, urban nationalists easily won control of the constituent assembly and installed Atassi as president. Secular nationalists could ignore them because they were still small. (Qassab remained in exile until the late 1930s.) Consequently—and again in contrast to Rida’s era—conservative Muslims were now largely excluded from the process of drafting the constitution. With much rancor and little to fear, Atassi’s secular nationalists rejected religious clerics’ proposals in the constituent assembly, especially their bid to restore a monarchy.36

As a result, the 1928 assembly produced a constitution for a secular republic. The new constitution (ultimately adopted in 1930 after France removed articles that would have stripped its authority and reunited Syria with Lebanon) called for a “parliamentary republic” with a single-chamber legislature (abolishing the Senate). The president would be elected by the Chamber of Deputies for a five-year term. Like the king in 1920, the president had to be Muslim—a requirement considered “outmoded” by secularists in 1928, but necessary to appease public sentiment. The president no longer swore loyalty to “divine laws,” as Faisal had done; rather, he vowed to “observe the Constitution and the laws of the country.” The article affirming the equality of Syrians before the law was strengthened in Article 6 of 1928 to guarantee that “no distinction shall be made between them in respect of religion, faith, race, or language.”37

In response to defeat, however, Islamist leaders built a broad opposition movement. Women who had hoped that secular nationalists might promote their rights again met disappointment. As the political cost rose, Atassi’s nationalists backed away. By 1930, the women’s movement altered its agenda to emphasize support for their maternal duties in the home, rather than suffrage.38

Islamic populists waged street demonstrations against initiatives to reform personal status laws, mixed-sex public schools, and against the expansion of women’s rights. The moderate middle—which had permitted compromise before the French occupation—dropped out, and Syrian politics polarized. Pro-French religious elites who had cooperated with the French were pulled toward the Islamist opposition by figures like Qassab, who returned from exile in 1937 to form an association of clerics (“ulama’”). After years in Saudi Arabia, Qassab had the aim of establishing an Islamic government—in contrast to his support of Rida’s compromises in 1920. His movement toppled the secular nationalist government the next year. In 1940, another nationalist leader, personally pious but adamant on the separation of religion and state, was murdered by an Islamist activist. Soon thereafter, local Islamic groups united into the national Syrian Muslim Brotherhood, following the lead of a parallel movement in Egypt.39

The Muslim Brotherhood’s Anticolonial Roots

The Muslim Brotherhood differed from the Ottoman-era Islamic reform movements. It was not an elite intellectual movement, but rather a mass movement that simplified ideas about modern Islam to attract followers. It thereby dropped older reformers’ focus on the convergence of European Christian and Muslim values to affirm Islam as an alternative to the liberal modernism practiced by elites. The Brothers united with religious conservatives against liberalism as an alien corruption: progress and justice had to come from Islam itself. The founder of the Syrian Brotherhood, who studied in Cairo, spoke in a political vernacular that ordinary people understood; by contrast, liberals had since 1920 tended toward elitism. The Brotherhood in both Egypt and Syria regarded labor organizers and communists as their primary rivals for recruitment.40

The founder of the Syrian Brotherhood, who studied in Cairo, spoke in a political vernacular that ordinary people understood; by contrast, liberals had since 1920 tended toward elitism. The Brotherhood in both Egypt and Syria regarded labor organizers and communists as their primary rivals for recruitment.

The memoir of Banna, the Egyptian Brotherhood’s founder, demonstrates the direct link between the rise of Islamism and Europeans’ exclusion of Arabs from the family of sovereign, civilized nations at the Paris Peace Conference. Like ordinary citizens in postwar Syria, Banna had joined Egyptian demonstrations for national independence. When Paris ruled that all Arab portions of the former Ottoman Empire—except for Arabia—should remain under European rule, it had effectively cast them into a subcategory of humanity, along with colonized Asians and Africans, who did not deserve the right to self-determination that Wilson proclaimed. European diplomats and missionaries made it clear that Arabs would have to shed their Islamic religion if they wished to join modern civilization. The colonization of elite Arab society after 1919 drove another wedge between liberals and Islamists.

Banna arrived in Cairo in 1922 to find an alien world, he wrote in his memoir. The pious environment of his rural hometown did not prepare him for city streets filled with Europeans and elites who dressed like them. Banna’s education had been informed by the town’s religious leaders; education at the new national university was adamantly secular. Liberal elites “waged a crusade against religion and its social traditions,” he recalled. In the name of individual freedom, they unloosed “a wave of atheism and lewdness.” Students split into two hostile camps, elites who embraced modern ideas, and the others who remained ignorant. When Banna took his first teaching post in the town of Ismailia, located on the Suez Canal, he was aghast to find the street signs written in French, and to find native Arabic speakers huddled in a shantytown, excluded from the wealthy side of the city where European employees of the Suez Canal Company lived.

“I was very much pained to see this state of affairs in the country,” Banna wrote, in a memoir published for hundreds of thousands of followers in the 1940s. “I felt my cherished Egyptian nation was torn asunder between two conflicting ideologies. On the one hand there was their revered faith, Islam, which they had inherited and preserved at all cost…. It had brought glories in the past and was still capable of lending dignity and honour to its followers. And on the other hand, there was a fierce attack of Western thought and culture [aiming] to destroy the old values of life.”41

Banna founded the Muslim Brotherhood in 1928 at Ismailia to restore the lifeworld of Islam, explicitly against European liberal influence. His followers came from the middling social classes that had been excluded from higher posts and elite society precisely because of their inadequate mastery of European social codes. His message also resonated with Egyptian Muslims who felt their collective spiritual well-being was under attack. A series of controversies rocked the country in this period, as Protestant missionaries sought conversions. They were regarded as foot soldiers of an aggressive Christian world and their pamphlets were seen in parliament and the press not as acts of freedom of individuals, but as insults to Islam. Missionaries’ claim to rights in a secular polity reinforced the idea that liberalism was hostile to Islam and to the sovereignty of Muslim nations.42 The Brotherhood was born of the same exclusionary and contemptuous practices that had deemed Arabs and Muslims unworthy of national rights at Paris in 1919.

The Brotherhood was at first less a rejection of liberalism than a movement to forge an indigenous modernity for ordinary pious people. Banna and the Brotherhood promoted an active, living form of Islam against the abstract, scholarly Islam of the landowning elites who had accommodated to, and profited from, the British occupation. While incorporating elements of modern life, the Brotherhood’s propaganda demonized the West as a threat to humanistic Islam. Muslim activists not only targeted British imperialism, but also Christian missionaries who flooded into Egypt after 1918. Their propaganda (much like Rida’s laments in his magazine) emphasized the humiliation of the Islamic world at the hands of European imperialists. Social justice was possible only through the embrace of Islam’s egalitarian and ascetic values. Elites, captivated by fast cars and imported suits, were “the arch-enemies of this Islamic call,” Banna wrote.43

Nowhere was the turn away from the universal claims of European liberalism more evident than in an open letter that Banna addressed to Egypt’s King Farouk in 1936. Unlike Rida in 1920–21, Banna made no appeal to the better nature of European liberals. He instead urged the king to embrace an Eastern model of justice. “[The West’s] political foundations are being razed by dictatorships, its economic foundations battered by crises,” he advised the king. “Be the first to offer, in the name of God’s Prophet (May God bless and save him!), the Qur’an’s medicine to save this sick and tormented world.”44 For Banna, like later anti-colonial thinkers, the pretense that European values were universal served to dupe colonial subjects into accepting imperial tutelage. There are elements to Banna’s text that foreshadow anticolonial arguments made a decade later by Frantz Fanon in Algeria.

For Banna, like later anti-colonial thinkers, the pretense that European values were universal served to dupe colonial subjects into accepting imperial tutelage. There are elements to Banna’s text that foreshadow anticolonial arguments made a decade later by Frantz Fanon in Algeria.

The consequences for Egyptian politics were profound. Banna did not immediately reject the secular regime established by the 1923 constitution; rather, he proposed only to review legislation to ensure it conformed to Islamic law. He even tried to run for parliament, but the government thwarted him with threats and by rigging the election. Banna strengthened his criticism of party politics and promotion of Islam as the sole legitimate ideology.45

But 1919’s glow of national unity had faded. As Copts feared, the entanglement of Christians with the European occupier predisposed some political parties to adopt sectarian agendas that undermined the universalist language of liberal rights. Meanwhile, the monarchy also cultivated influence through the patronage of Muslim clerics. In the early 1930s, Banna won parliamentary support for increased religious (Islamic) instruction in state schools, which therefore declined to hire Copts. As the state school system expanded, increasing numbers Muslims graduated to find the civil service dominated by Copts who had been privileged by the British. Later in the decade, a violent wing of the Brotherhood perpetrated violent attacks upon non-Muslims. Public discourse shifted away from liberal rhetoric toward Islam.46

Rashid Rida’s Ambiguous Legacy

Rida was a key player linking the transformation of Islamic politics in both Syria and Egypt. Banna regularly attended his lectures in Cairo in the mid-1920s. He cited Rida as an inspiration for founding the Brotherhood as an activist organization, in contrast to passive scholarly and charity groups. And Banna was so devoted to Rida’s magazine, The Lighthouse, that he took over publishing it after Rida’s death in 1935.47

Rida’s commitment to Islamic liberalism had begun to weaken by the time Banna met him. It was not a sudden or even complete break. After publishing his rebuke to European liberals in 1922, Rida wrote a book on reestablishing the Islamic caliphate. He argued that the caliphate had to exist in a sovereign country and coexist with representative democracy. And he dedicated the book to the “courageous Turkish people” and to the Ottoman caliphate, as the bulwark against Muslims’ enslavement by Crusaders and as the defense of justice against tyranny.48 A year later, however, the Turkish republic abolished the caliphate. President Mustafa Kemal Atatürk inaugurated reforms to abolish Islamic law and to disestablish Islam as the state religion.

Rida felt betrayed, shocked, and angered. His hope that Muslims might find a new sovereign leader briefly renewed when Syria broke out in revolt in 1925. He and the Syro-Palestinian Congress provided it support, including funds from the new king of Arabia, Ibn Saud. After the 1925–27 Syrian Revolt failed, Rida threw his support more fully behind Ibn Saud, who was the world’s only sovereign Muslim ruler and who guarded the holiest sites in Islam. While Rida did not fully endorse the Wahhabi puritanism of Ibn Saud’s government, he recognized its potential to unite Muslims against the overwhelming dominance of Europeans. For Rida, justice was possible only under conditions of full sovereignty.49 By 1927, Rida parted ways with his secular nationalist and Christian partners in the Syro-Palestinian Congress who sought a compromise with the British and the French. His faction strengthened ties to Ibn Saud.50

At the same time, Rida gradually discarded his faith in an East–West consensus of values. Because Rida exerted wide influence in the Islamic world through his magazine, British intelligence followed his political activities in Cairo closely. They reported in 1926, for example, that Rida used his magazine as a means to facilitate communication between Ibn Saud and Tunisians. He had also founded the Eastern Bond Society as a pan-Islamic organization to “unite Moslem peoples against the dominance of Western powers.” The British feared the group would fan dissent in Persia and Afghanistan; like the French in Syria, they cast Muslims who insisted on their rights in the new world as fanatics and terrorists. In fact, the society promoted political contacts and cultural exchange, valorizing the East as a civilization with its own merit. A few years later, however, when secularist liberals took over the society’s journal, Rida quit.51

Rida was also a prominent participant in the Jerusalem Islamic Congress of 1931. It was the largest Muslim gathering since the debates following the fall of the caliphate in 1924. Participants arrived from all over the Muslim world, including Russia, India, Bosnia, and North Africa. They shared a common Muslim concern for the religious monuments in Jerusalem, considered Islam’s third holiest city. Rida chaired a session on Islamic reform and education, where he proposed a simplified, uniform curriculum for Muslim students across the world, regardless of region or sect. Common education, and the continued existence of the Congress, he believed, would be important in building the international brotherhood of Muslims for which he had advocated for thirty-five years.52

Back to Religious Principles

The shift in Rida’s views are fully evident in his last major book, The Muhammadan Revelation, published in 1934. It was a passionate defense of the Prophet Muhammad’s message against the criticisms of European Orientalist scholars and Christian missionaries. Rida argued that the revelations made to the Prophet in the seventh century were a divine miracle, not a threat. They did not oppose or contradict the beliefs of Jews or Christians. Rather, they embodied the message of their prophets in the purest form. Rida condemned fanatics who assumed the right to coerce others to adopt Islam. “There is no compulsion in religion,” he quoted from the Qur’an.53

Rida argued that the revelations made to the Prophet in the seventh century were a divine miracle, not a threat. They did not oppose or contradict the beliefs of Jews or Christians. Rather, they embodied the message of their prophets in the purest form. Rida condemned fanatics who assumed the right to coerce others to adopt Islam. “There is no compulsion in religion,” he quoted from the Qur’an.

Rida still believed, contrary to British and French fears, that Islam was a benevolent and tolerant religion. In fact, his book proposed Islam as a substitute for Wilsonism, as a route to world peace. “Thus, the solution to the world’s problems is faith in the Book which prohibits tyranny and all other forms of corruption,” he wrote. Islam prohibits aggression and war for material gain, as perpetrated by Europeans: “In our own times, the peoples of the world have been subjected to the worst sort of conflict, even to the point where civilization itself was at stake, given the kinds of weapons that have come into use; poison gas, machine guns, and bombs dropped from airplanes on populated cities, so that entire populations of men, women, and children, can be exterminated in minutes.”54

Rida’s text makes clear his break with European models, but not completely with liberal principles. He offered Islam as a substitute for Wilson’s architecture of peace, which had collapsed first in the Middle East and now, in 1934, in the entire world. He insisted that Islam called for the common humanity and equality of all peoples, rejecting the racist hierarchy that caused war in Europe and that corrupted the League of Nations. Europeans’ “insistence on the superiority of their white skin, and their contempt for the rights of black-, brown-, red-, and yellow-skinned people, have led them to all manner of excesses and tyranny, and to disgrace their own civilization.”55

Rida died in August 1935 at age seventy. His memorial service displayed the difficult but inexorable transition that had occurred in politics since 1920. A Syrian nationalist in exile who had served in Faisal’s cabinet, Abd al-Rahman Shahbandar, took the podium. Shahbandar had studied religion and still employed Islamic phrases in his speeches. But he strictly believed in the division of religion and state, as he believed Rida had once done in the Syrian Congress. In his speech, he praised Rida’s dedication to religious and national revival, even though a “group of people who resented religious reform, freedom and the constitution plotted against him.” Rida showed that there was no contradiction between reason and religion, or between religion and democracy, Shahbandar declared, to an audience of clerics who had already shifted away from that view.56

A Christian journalist from Lebanon, Habib Jamati, spoke next. He directed his eulogy to the dean of Al-Azhar (also known as the sheikh of Al-Azhar), who had remarked that Rida had three main opponents: secularists, non-Muslims, and traditional Muslims. “I have the honor to raise my voice at this notable Islamic gathering,” Jamati began, “at the same time that Arab Easter bells ring, mingling with the voices of the faithful, calling for brotherhood, solidarity, cooperation for the Arab nation, for the sake of the slaughtered homelands!” While Egyptians may have regarded Rida as a great Islamic leader, he had also befriended Christians, and struggled alongside them for their common nation, Jamati declared. “He returned to Syria right after the Great War, and given his lofty status in the hearts of people, the Syrians elected him president for their national congress, which convened in Damascus in 1919 and decided to declare the independence of Syria as an Arab country,” Jamati recalled. “Al-Sayyid Muhammad Rashid Rida’s views, advice, and guidance deserve a great credit for the success of that blessed movement. But fate turned against Syria’s struggle for revival.”57

Later Constitutions

As Rida’s memorial and Banna’s memoir suggest, Muslim exclusion and subjugation by the Paris Peace Conference and its successor, the League of Nations, remained a painful memory among those who witnessed the rise of sectarian politics in Egypt and Syria. The liberal–Islamist cleavage apparent by the time of Rida’s death in 1935 continued to define Syrian and Egyptian politics even after they gained independence following World War II.

When French troops left Syria in 1946, Syria’s Islamists united into the national Syrian Muslim Brotherhood under the leadership of Mustafa al-Siba’i. He had studied in Cairo in the 1930s and maintained close links with Banna. He and two Brotherhood members won seats in parliament in 1947. Three years later, in 1950, Siba’i gained a seat in the constituent assembly. He aimed to avenge the assault on the Brotherhood the year before, when a secularist colonel staged a military coup and outlawed the organization. At his urging, Muslim women began unveiling in public.

Now, in 1950, Siba`i proposed that the constitution declare Islam the state religion. He justified it as a way to rally citizen support after defeat in the 1948 war with Israel. Secular nationalists and Christians organized campaigns in opposition. Protest was so vigorous that the government banned public discussion of the issue. Following a tense debate, the constituent assembly rejected the establishment of Islam as the state religion. But at the eleventh hour, Siba’i was able to insert two religious clauses into the constitution: the preamble affirmed the state’s “attachment” to Islam as the majority religion, and Article 3 stated that “Islamic law shall be the main source of legislation.”58

At the eleventh hour, Siba’i was able to insert two religious clauses into the constitution: the preamble affirmed the state’s “attachment” to Islam as the majority religion, and Article 3 stated that “Islamic law shall be the main source of legislation.”

The clause on Islamic law was the first of its kind in an Arab constitution, but nearly all Arab states have since adopted a version of it. The Syrian Brotherhood recalled 1950 as a great victory, even as it has continued to demand democracy against the Ba’athist dictatorship. However, opponents have seen a contradiction between prioritizing Islamic law and guaranteeing equality of all citizens, and between popular sovereignty and the Brotherhood’s insistence on scripture as a source of law.59 Article 3 effectively overturned the compromise Rida had struck in 1920, when he conceded that such a requirement would render non-Muslims unequal citizens. Rida had made clear the distinction between religious affairs to be governed by Islamic law, and public affairs to be governed by laws promulgated by an elected assembly.

The Ba’athist regimes that have ruled Syria since 1963 retained the Islamic law clause, presumably because to remove it would threaten their legitimacy.60 However, in the wake of the Syrian civil war, which has sundered the nation along bloody sectarian lines, Syrian constitutional scholars call for the clause’s removal.61

In Egypt, both post-2011 regimes have retained similar clauses in the constitutions that were introduced in 1971 under highly politicized circumstances. Anwar Sadat had sought to woo Islamists and conservatives against secular and social rivals with Article 2, which stated that the principal source of legislation is Islamic law. In the 2012 and 2014 constitutions, Article 2 is nearly identical, but allows room for interpretation by referring to principles of law, not the law itself: “Islam is the religion of the state and Arabic is its official language. The principles of Islamic Sharia are the principal source of legislation.”62 In both, Article 3 reads: “the principles of the laws of Egyptian Christians and Jews are the main source of laws regulating their personal status, religious affairs, and selection of spiritual leaders.” The clauses have done what Wafdist Copts had feared: cast Muslims as the true Egyptians and non-Muslims as distinct and subordinate peoples. The combination of Articles 2 and 3 place non-Muslims in the position of living under Islamic law in matters of public policy. As in Syria, the scriptural source of law lies in tension with the constitutional commitment to democracy.

The post-coup government of Abdel Fattah el-Sisi has, however, rolled back the authority of Muslim clerics in public law. The 2014 constitution revised and moved Article 4 of Morsi’s 2012 version, which had required that Al-Azhar’s Council of Senior Scholars be consulted in matters related to Islamic law.63

Enduring Cleavages

The Arab uprisings failed to topple dictatorship for many reasons not discussed here. As significantly, they have failed to mend the liberal–Islamist cleavage that weakened the revolutionary movement and that results in constitutions that bandage over the cleavage with contradictory language that undermines inclusion and pluralism.

Constitutional scholars locate the problem in procedural terms. As one scholar remarked, the post-2011 Egyptian constitutions were drafted in the spirit of political conquest over a vanquished opponent, first by the Egyptian Muslim Brotherhood and then by a military establishment allied with elite liberal and Christian groups. “The 2012 and 2013 constitutional experiences confirm that the only safe exit for a constitutional process locked in a logic of short-term balance of power is the participation and equal representation of all political and social forces,” writes Yasmine Farouk.64

In the eyes of journalists and policymakers, the failure of constitutional reform in Egypt and Syria seems to validate the old claim of Arab dictators, who contend that democracy would unleash Islamist intolerance and that only they can protect minorities. Both Egypt’s Sisi and Syria’s Assad promote the widespread belief that political division can be soothed with top-down legal and judicial intervention.

But a historical perspective offers a different truth. The polarization of elite liberals and Islamic democrats rests less on principle and more on repertoires of political contestation embedded in the practice of decades. The liberal–Islamist cleavage is not age-old, as the compromises struck in 1919–20 by the Syrian Congress and the Wafd Party demonstrate.

The polarization of elite liberals and Islamic democrats rests less on principle and more on repertoires of political contestation embedded in the practice of decades. The liberal–Islamist cleavage is not age-old, as the compromises struck in 1919–20 by the Syrian Congress and the Wafd Party demonstrate.

More relevant to contemporary policy concerns is to understand that because the cleavage is man-made, it can be unmade. Understanding the origins of the split is a start. If both sides of the cleavage can be made to understand the critical role played by external powers, they may begin to focus on repairing internal damage.

Of course, it is not possible to turn back the clock to 1919. Liberals and Islamists have built organizations over the intervening decades based on symbols and narratives that obscure this history. Both sides have inspired their followers with polarizing and essentialist rhetoric that finds affirmation in every round of violence. Historical knowledge is only a starting point for the next generation of activists who might try to rebuild a coalition against dictatorship. But it is a necessary starting point. As long as the cleavage persists, they cannot hope to stand strong against repressive regimes. Only a return to first principles and recognition of the origins of the cleavage can offer hope of transcendence.

This brief review of history has shown that Europeans’ insistence on occupying Syria, Egypt, and other Arab lands after World War I undermined the basis on which Arab liberals sought to establish new nation-states. Most damaging was the betrayal of Arab liberals: the victorious Allies who gathered at Paris had promised a new world order based not on imperial might but rather on the rights of peoples. They had made additional, explicit promises to the peoples of Greater Syria and Egypt in exchange for their support in the war effort. Arabs were not simply denied rights in 1919 and 1920. They had been invited to step through the door into the family of nations, only to be violently expelled. Syrians suffered the humiliation of being transformed from self-governing citizens who voted and served in the Ottoman parliament into colonial subjects policed by colonial troops. Acknowledging the damage done and salving humiliation is a primary step toward moderating hardline stances.

History has shown that Europeans’ insistence on occupying Arab lands after World War I undermined the basis on which Arab liberals sought to establish new nation-states.

A second outrage was to see Arabs tarnished with a reputation for fanatical sectarian violence, because they were coreligionists of Ottoman Turks who had committed genocide against Armenians and atrocities toward other Christians during the war. France and Britain routinely insinuated the possibility that Muslim-dominated Arab states might renew massacres of Christians. In turn, these European powers’ religious discrimination fueled the embers of defensiveness and reaction by Muslim leaders, in both experienced scholars like Rida and younger laymen like Banna. A third bitter blow was to see landed elites profit from foreign occupation, and justify their privilege by claiming that liberalism was a European culture that must be learned. This lay the foundation for a populist revolt against elite liberalism and its captive, non-Muslim clients. Current policymakers must recognize that the rhetoric of the “war on terror” fanned bitter resentments rooted deeply in history. Such rhetoric stokes justification for militant Islamist groups and erases the memory and therefore the potential for modern Islamic politics.

Knowledge of the origins of a political cleavage help to heal it, or at least to soften it, by encouraging scholars of history, law, and current politics to ask new questions about causes of friction and distrust. The key is for both liberals and Islamists to understand where their differences lie: Not in the immutable dogma of ideology, but rather in political events that took place one hundred years ago. Every politician knows that telling stories is the best means of persuasion. This can be accomplished with new conversations that address the elephant in the room in a productive manner. Working from a historical perspective enables us to place the current impasse in Arab politics in a comparative global context, and thus mute the manic reproduction of ill-advised theses about the so-called incompatibility of Islam and democracy.

This policy report is part of Citizenship and Its Discontents: Pluralism, and Inclusion in the Middle East, a TCF project supported by the Henry Luce Foundation.

Cover Photo: A portrait of Mohammed Rashid Rida Source: Wikipedia Commons

Notes

- Kareem Fahim and David D. Kirkpatrick, “Protesters Gather to Denounce Morsi in Scenes Recalling Uprising,” New York Times, November 28, 2012, https://www.nytimes.com/2012/11/28/world/middleeast/egypt-morsi.html.

- Yasmine Farouk, “Writing the Constitution of the Egyptian Revolution: Between Social Contract and Political Contracting,” in Constitutional Reform in Times of Transition, ed. Álvaro Vasconcelos and Gerald Stang (Paris: Arab Reform Initiative, 2014), 98–116.

- Samer S. Shehata, “In Egypt, Democrats vs. Liberals,” New York Times, July 2, 2013, https://www.nytimes.com/2013/07/03/opinion/in-egypt-democrats-vs-liberals.html.[/note]

The split between Islamists and liberals took a deadlier turn in Syria’s Arab uprisings. Protests for constitutional rights descended into a civil war, in which armed Islamists overwhelmed the original, liberal opposition. The regime of Bashar al-Assad escalated the war with claims to protect Syrian minorities from terrorists. The Egyptian coup leader, Abdel Fattah el-Sisi, likewise recruited Coptic Christians with claims of defending democratic pluralism against Islamist demagoguery. As a kind of funeral bouquet to the Arab uprisings, dictators in both Syria and Egypt offered their own constitutions. Neither of their constitutional reforms, however, rolled back the inflated influence of Islam in previous constitutions.

Constitutional scholars have argued that such top-down prescriptions don’t work. “The expectation that constitution-drafting should be designed to resolve long-lasting and deeply rooted societal disagreements on religious issues is often unrealistic,” conclude Aslı Bâlı and Hanna Lerner, whose research shows that bottom-up, inclusive constitutional processes have a better track record.3 Aslı Ü. Bâlı and Hanna Lerner, “Introduction” to their edited volume, Constitution Writing, Religion and Democracy (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2017), 10.

- Nathan J. Brown, “Reason, Interest, Rationality, and Passion in Constitution Drafting,” Perspectives on Politics 6, no. 4 (Dec. 2008): 675–89.

- Vasconcelos, “Introduction: Prioritizing the Legitimacy of the Process,” in Vasconcelos and Stang, Constitutional Reform, 8–14.

- Nael Georges, “Constitutional Reform: The Case of Syria,” in Vasconcelos and Stang, Constitutional Reform, 117–24; Nathan J. Brown, “Islam and Constitutionalism in the Arab World: The Puzzling Course of Islamic Inflation,” in Bâlı and Lerner, Constitution Writing, 289–316.

- Abu Khaldun Sati al-Husri, Yawm Maysalun (Beirut: Dar al-Ittihad, 1965) 210-11. See also the translation of the same: The Day of Maysalun, trans. Sidney Glazer (Washington, DC: The Middle East Institute, 1966), 101–2.

- Keith David Watenpaugh, Being Modern in the Middle East (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2006), 125, 129, 140–45.

- Al-Husri, Yawm Maysalun, 214.

- Andrew Patrick, America’s Forgotten Middle East Initiative: The King-Crane Commission of 1919 (New York: I. B. Tauris, 2015), 176–81.

- Muhammad Rashid Rida, “Lessons from Faisal’s Life (6),” al-Manar [The Lighthouse] 34 (May 1934): 68–72.

- Muhammad Rashid Rida, “Second Syrian Trip (10b),” al-Manar [The Lighthouse] 22 (May 1922): 390–96 and “Lessons from King Faisal’s Life (7),” al-Manar [The Lighthouse] (June 1934): 152–57.

- Mari Almaz Shahrastan, al-Mu’tamar al-Suri al-`Amm 1919-1920 [The Syrian General Congress 1919-1920] (Beirut: Dar Amwaj, 2000), 193–208, reprinting the newspaper account of the suffrage debate in al-Difaa, April 27, 1920; Muhammad Izzat Darwazah, Mudhakkirat Muhammad `Izzat Darwaza, 1887–1984 [Memoirs of Muhammad Izzat Darwazah], vol. I (Beirut: Dar al-Gharb al-Islami, 1993), 462. On Rida and public interest, see Dyala Hamzah, “From `ilm to Sihafa or the Politics of the Public Interest (Maslaha): Muhammad Rashid Rida and His Journal al-Manar (1898–1935),” in The Making of the Arab Intellectual, ed. Dyala Hamzah (New York: Routledge, 2013), 90–127.

- Articles 67, 88, 91, and 128 of the Constitution of the Syrian Arab Kingdom, reprinted in Hasan al-Hakim, al-Watha’iq al-Tarikhiya al-Muta’alliqa bi al-Qadiya al-Suriya, 1915–1946 (Beirut: Dar Sadr, 1974), 194–213. The first English translation from the Arabic will appear in my forthcoming book from Grove-Atlantic Press. The 1909 Ottoman constitution was retrieved in English translation from the Bogazici University’s Ataturk Institute of Modern Turkish History, accessed on February 12, 2019, http://www.anayasa.gen.tr/1876constitution.htm.

- Benjamin Thomas White, The Emergence of Minorities in the Middle East (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2012), 43–66.

- Malcolm B. Russell, The First Modern Arab State: Syria under Faysal, 1918-1920 (Minneapolis: Bibliotheca Islamica, 1985) 81–85; Farid Istafan, Habib Istafan: Ra’id min Lubnan [Habib Istifan: Pioneer from Lebanon] (Beirut: Dar Lahud Khatr, 1983) 57–68; French government translation of May 4, 1920 speech as published in al-Hadaf newspaper, May 6, 1920. I thank James Gelvin for sharing the document with me.

- Memo on the proclamation by Congress, Maronite Church Archives at Bkerke, Lebanon, Hoyek Series: 038/026; letter from Clemenceau November 10, 1919, 036/026; and note from the Haut Commissariat de la République de la France en Syrie, May 20, 1920, 036/324.

- Bernard Botiveau, “The Law of the Nation-State and the Status of Non-Muslims in Egypt and Syria,” in Christian Communities in the Arab Middle East, ed. Andrea Pacini (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1998), 112–16.

- Midhat Pasha, “The Past, Present, and Future of Turkey,” The Nineteenth Century 3 no. 16 (June 1878): 992.

- Muhammad Rashid Rida, “The Constitution, Freedom, and the Islamic Religion,” al-Manar [The Lighthouse] 12, no. 8 (September 1909): 609

- L. Carl Brown, International Politics and the Middle East (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1984).

- Speech by Zaghlul, in “Hamad Pasha El Bassel’s Tea Party,” January 16, 1919, British National Archives, Kew, FO 141/810/6; Ziad Fahmy, Ordinary Egyptians (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2011), 136–66; diary of A.S. Milner, December 21–22, 1919, Alfred Milner Papers, MS Milner dep. 97, Bodleian Library, Oxford University.

- Afaf Lutfi Al-Sayyid-Marsot, Egypt’s Liberal Experiment: 1922-1936 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1977) 63–72; James Whidden, “The Generation of 1919,” in Re-Envisioning Egypt 1919-1952, ed. Arthur Goldschmidt, Jr., et al. (New York: American University in Cairo Press, 2005), 30.

- “Royal Decree No. 42 of 1923 on Building a Constitutional System for the Egyptian State,” trans. Joy Ghali, on behalf of International IDEA, accessed Jan. 15, 2019 at: http://constitutionnet.org/sites/default/files/1923_-_egyptian_constitution_english_1.pdf; “Dustur: A Survey of the Constitutions of the Arab and Muslim States,” reprinted, with additional material, from the second edition of The Encyclopedia of Islam (Leiden: E. J. Brill: 1966): 28–29. The constitution reserved control over security and foreign affairs to the British and granted the preponderance of power to the King. Zaghlul returned to Egypt a hero, but was unable to wield effective political power in a political system that only superficially appeared liberal and democratic.

- Vivian Ibrahim, The Copts of Egypt (New York; I. B. Tauris, 2013), 56–75, 80–81; Marius Deeb, Party Politics in Egypt: The Wafd and Its Rivals 1919-1939 (London: Ithaca Press, 1979), 70–75; “Interview with Simaika Pasha, Dec. 14, 1918” and “Ministry of Interior Memo, Jan. 11, 1919,” both in British National Archives, Kew, FO 141/810/6.

- Charles D. Smith, Islam and the Search for Social Order in Modern Egypt (Albany, NY: State University of New York Press, 1983), 61–75.

- “Col. Cousse to High Commissioner, Beirut,” July 15, 1920, Renseignement 696, Service Historique de l’Armée de terre (SHAT), Vincennes, SHD-GR4-H114-005.

- Muhammad Rashid Rida, “The Aftermath of the Great War,” al-Manar [The Lighthouse] 21 (April 1920): 337–44.

- “Alexandre Millerand to Commandant Armée du Levant,” July 29, 1920, Ministère des Affaires étrangères, Nantes archives, Fonds Beyrouth, Carton 2358.

- “Correspondance between Gen. Gouraud and Premier Millerand,” August 2–7, 1920, in Documents diplomatiques français relatifs à l’histoire du Liban et de la Syrie à l’ époque du Mandat: 1914-1946, vol. II. Ed. Antoine Hokayem (Paris: L’Harmattan, 2012), 567–89.

- “Letter to M. Gabriel Hanotaux,” September 27, 1921, British National Archives, FO 141/552/1.

- Muhammad Rashid Rida, “The European Trip (5),” al-Manar [The Lighthouse] 23 (July 1922): 553–58.

- “Syrians Threaten War on the French,” New York Times, May 14, 1922: 3, https://www.nytimes.com/1922/05/14/archives/syrians-threaten-war-on-the-french-cable-leagare-council-they-will.html.

- Muhammad Rashid Rida, “The European Trip (7),” al-Manar [The Lighthouse] 23 (November 1922): 696–99.

- Philip S. Khoury, Syria and the French Mandate: The Politics of Arab Nationalism, 1920–45 (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1988), 251–65, 327–40; Elizabeth Thompson, Colonial Citizens: Republican Rights, Paternal Privilege, and Gender in French Syria and Lebanon (New York: Columbia University Press, 2000), 136.

- “Constitution of 14 May 1930,” in Helen Miller Davis, Constitutions, Electoral Laws, Treaties of States in the Near and Middle East (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1947), 263–76; Khoury, Syria and French Mandate, 340–48. The 1928 constitution strengthened the legislature’s power and expanded on civil liberties enumerated in 1920. Article 8 introduced habeas corpus protections for those arrested, who must be informed of their charges within twenty-four hours. Articles 15, 16, and 18 included stronger language on the privacy of mail and telephone communications, as well as on freedom of belief and religious worship. Article 21 explicitly made elementary education obligatory for both boys and girls. However, suffrage was again granted only to men (Article 36) and language on the representation of minority groups was less definitive (Article 37).

- Thompson, Colonial Citizens, 117–26.

- Itzchak Weismann, “The Invention of a Populist Islamic Leader: Badr al-Din al-Hasani, the Religious Educational Movement and the Great Syrian Revolt,” Arabica 52, no. 1 (2005): 109–39; Hasan al-Hakim, Abd al-Rahman al-Shahbandar: Hayatihu wa Jihaduh (Beirut: Dar al-Mutahida lil-Nashr, 1985), 231-32; Khoury, Syria and French Mandate, 584–89; Thompson, Colonial Citizens, 148–54, 205–10, 261–70.

- Umar F. Abd-Allah, The Islamic Struggle in Syria (Berkeley, CA: Mizan Press, 1983), 88–101.

- Hasan al-Banna, Memoirs of Hasan Al Banna Al Shaheed, trans. M.N. Shaikh (Karachi: International Islamic Publishers, 1981), 109–11.

- Jeffrey Culang, “‘The Sharia Must Go’: Seduction, Moral Injury, and Religious Freedom in Egypt’s Liberal Age,” Comparative Studies in Society and History 60, no. 2 (2018): 446–75; Beth Baron, The Orphan Scandal: Christian Missionaries and the Rise of the Muslim Brotherhood (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2014): 117–34.

- Brynjar Lia, The Society of the Muslim Brothers in Egypt (Reading, UK: Ithaca Press, 1998), 72–86; Beth Baron, The Orphan Scandal: Christian Missionaries and the Rise of the Muslim Brotherhood (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2014).

- Hassan al-Banna, “Nahwa al-Nur,” in his Majmuat Risail al-Imam al-Shahid Hasan al-Banna (Beirut: Dar al-Nahhar, 1965), 190–91. Translated with an incorrect original date (1947 instead of 1936) as “Toward the Light,” in Five Tracts of Hasan al-Banna (1906-1949), trans. Charles Wendell (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1978): 124–25.

- Thompson, Justice Interrupted: The Struggle for Constitutional Government in the Middle East (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2013), 150–76.

- Whidden, “Generation of 1919,” 35–41; Ibrahim, Copts of Egypt, 75–98; Smith, Islam and Search for Social Order, 89–108.

- Lia, Society of Muslim Brothers, 56-57, 97.

- Mahmoud Haddad, “Arab Religious Nationalism in the Colonial Era: Rereading Rashid Rida’s Ideas on the Caliphate,” Journal of the American Oriental Society 117, no. 2 (1997): 270–76; Al-Shaykh Muhammad Rashid Rida, al-Khalifa (Cairo: al-Zahra al-A’lam al-‘Arabi, 1988). Originally published in 1922.

- Rida to Arslan, October 29, 1925 and November 12, 1925 in Amir Shakib Arslan, Al-Sayyid Rashid Rida aw Ikha’ Arba’in Sana (Cairo: Dar al-Fadila, 2006), 324–30.

- “Neville Henderson to Austen Chamberlain,” November 7, 1927, in British National Archives, Kew, FO 141/810/6.

- “Report from the French Ambassador,” December 30, 1925, transmitted January 11, 1926, and “Founding of Rabita Sharqiya in Cairo 1926–28,” in British National Archives, Kew, FO 141/671/4 and FO 141/795/6; Israel Gershoni and James P. Jankowski, Egypt, Islam, and the Arabs (New York: Oxford University Press, 1986), 60–63, 264–67; Reinhard Schulze, A Modern History of the Islamic World, trans. Azizah Azodi (New York: I. B. Tauris, 2000), 65–74.

- Rashid Rida, “The General Islamic Congress in Jerusalem” (Arabic), parts 2 and 3, al-Manar [The Lighthouse] 32 (March 1932) and (April 1932), http://shamela.ws/browse.php/book-6947/page-4172 and http://shamela.ws/browse.php/book-6947/page-4182; Basheer M. Nafi, “The General Islamic Congress of Jerusalem Reconsidered,” The Muslim World 86, no. 3–4 (1996): 243–72.