For more than a half century and up to this day, Massachusetts’s well-earned reputation for liberalism and compassion have been at war with another, darker side that seeks exclusion, by race and class, in housing and schooling, in ways seen and unseen.

This tension surfaced vividly in 1974. In August of that year, liberal voters in Massachusetts—the only state to support George McGovern over Richard Nixon for president in 1972—felt vindicated when Nixon resigned in disgrace. But just a few weeks later, as public schools opened, progressive Massachusetts voters were horrified when residents of the state capital, Boston, made national headlines for violently resisting school desegregation. White working-class Boston residents shouted ugly racial epithets and pelted school buses carrying young Black children with bottles and bricks. The images recalled the angry white mobs in the South who, in places like New Orleans in the early 1960s, screamed hysterically at Black youth who just wanted an equal education.

Dr. Robert Coles, a child psychiatrist, had a front-row seat to both clashes, and each left a lasting impression. Coles, a Harvard College and Columbia Medical School graduate who had been stationed in the South as an Air Force doctor, was appalled when he observed white mobs showing up daily at a New Orleans elementary school to scream at a six-year-old Black girl, Ruby Bridges.1 Coles befriended the Bridges family and sought to provide psychological support for young Ruby, who endured a hellish walk to school each morning as a racist mob screamed at her. One woman even repeatedly threatened to poison her. One day, Coles saw Ruby mumbling words to herself just before she entered the school and asked her about what she was saying. He was astounded to learn that Ruby was praying for her tormentors.

Coles wrote about Bridges in The Atlantic and later in The Story of Ruby Bridges.2 Norman Rockwell famously painted the scene of a diminutive Ruby, escorted by giant FBI agents, in an iconic piece of art “The Problem We Live With” that later hung outside of President Barack Obama’s Oval Office. The experience was as clear a drama of good and evil, and right and wrong, as one gets, pitting an innocent Black girl against a hateful white mob who objected to her presence solely based on the color of her skin.

By 1974, Coles was a Harvard professor and was working near Boston when white mobs attacked Black youth for trying to attend public school under a court-ordered desegregation plan. As in New Orleans, Coles condemned white racism and violence unreservedly. But as he watched his Harvard colleagues shower disdain on working-class white people of Boston for their resistance to school integration, Coles also began to think about the invisible walls—the bans on multifamily housing, and the minimum lot size requirements for single family homes—that kept most Black people, and most working-class whites as well, out of the neighborhoods and schools in the sorts of suburbs where many educated white liberals resided.3 The federal judge who ordered desegregation, W. Arthur Garrity Jr., for example, lived in Wellesley, a wealthy and mostly white Boston suburb, which, almost fifty years later, remains just 2.9 percent Black and 5.1 percent Hispanic and has a median household income of $197,132.4

In an extensive October 1974 interview with the Boston Globe’s Mike Barnicle, Coles noted that while the busing crisis pitted Black and white low-income families, it ignored the larger reality that “People in the suburbs are being protected by a wall around the city of Boston.” He noted, “all the laws are being written for the wealthy and powerful. The tax laws, the zoning laws, the laws that have to do with protecting their housing and their education.”5 Of the wealthy people living in suburbs who condemned working-class whites, Coles said: “Their lives are clean and their minds are clean and their hands are clean. And they can afford this long, charitable, calm view. And if people don’t know that this is a class privilege, then, by golly, they don’t know anything.”6

Almost a half century later, the battles that progressives have waged to desegregate schools are fairly well known—even if courts have disgracefully retreated from their desegregation efforts to implement the promise of Brown v. Board of Education.7 But there hasn’t been a similar war waged on the walls that Coles noticed—the ones that operate invisibly to keep working-class people of all races out of more-affluent neighborhoods and schools in Massachusetts and throughout the country.

The battles that progressives have waged to desegregate schools are fairly well known . . . but there hasn’t been a similar war waged on the walls that keep working-class people of all races out of more-affluent neighborhoods.

The use of arcane zoning ordinances to keep people out of neighborhoods and schools is far less vivid than mobs throwing projectiles at schoolchildren. Perhaps for that reason, the victims of this exclusion by zoning are not as visible or as well-known to the society at large as are people like Ruby Bridges. This report seeks to elevate the voices of some of the individuals living in Massachusetts today who have felt the sting of exclusionary practices—people who represent the modern-day equivalents of Ruby Bridges—such as Karen, a Hispanic single mother who until recently resided in Chicopee, Massachusetts, and Samantha, a white single mother who not long ago was living in Springfield, Massachusetts. (Karen and Samantha asked that their last names not be used.)8

This report begins by telling the stories of Karen and Samantha and the challenges they faced living in high-poverty neighborhoods. It next describes the government-sponsored zoning barriers that exclusive communities employ to keep people like Karen and Samantha out of their safe neighborhoods and their high-performing schools. The report goes on to describe a small and innovative state program—called SNO Mass (Supporting Neighborhood Opportunity in Massachusetts)—that helped provide a gate for Karen and Samantha to pass through the local exclusionary zoning walls in order to experience better lives for themselves and their children. In this section, the report also tells the story of a third mother—Grace Perez, a Dominican-American mother—whose experience moving with the assistance of SNO Mass in an area north of Boston was more complicated. While the program helped Perez get beyond exclusionary walls, it could not shield her from the racial prejudice that she and her family found once inside an exclusionary community. (Perez has now moved to a different high-opportunity community, where she says she is welcomed and doing well.) The report concludes with a call to expand the SNO Mass program that helps a small number of families to scale exclusionary walls, and to enact more systemic reforms to dismantle the walls themselves.

Living Outside of Exclusionary Walls

A few years ago, before they became involved in the SNO Mass program, Karen and Samantha each were deeply frustrated. They wanted what virtually all mothers want—a safe neighborhood with good schools for their children—but saw the desire as a distant dream.

Karen

In 2017, Karen, a U.S. Navy veteran and divorced mother of three children, was eager for a change.9 Karen, who is Hispanic, and has worked as a loss prevention detective for department stores, was living in Chicopee, a city of about 50,000 residents in western Massachusetts, in order to be close to her children’s father, also a U.S. Navy veteran.10 But she was beginning to search for a way out.

Karen says that Chicopee has “declined over the years.” In 2019, it had a median household income of $53,225, far below the state median income of $81,215. About 80 percent of families lack a bachelor’s degree.11 Crime was on the rise, she says. “I definitely didn’t feel safe going outside,” Karen recalls.12

She says when she first moved to Chicopee, she was optimistic. “I was excited because right across the street, past the big intersection, there was a huge park,” with “a massive soccer field, baseball field, a little jungle gym area for the kids to play. And I was like, great. I can go there and I can just let them play in the sprinkler, and just do whatever they want there.” But then she began to notice “a lot of the homeless people started to hang around there and they kept leaving their needles behind [and] their beer bottles.” She continues, “I lived in the projects. I’ve seen the worst of the worst. But it’s not something that I want for my kids.”13

“I lived in the projects. I’ve seen the worst of the worst. But it’s not something that I want for my kids.”

Over time, things got worse. At one point, “there was a shooting down the block,” Karen recalls, and she said to herself, “I can’t even have my kids play in front of the house because what if someone decides to shoot a gun” and the bullet ricochets and hits them?14 Moreover, she says, “I found out that my downstairs neighbor’s son was a drug dealer and had an arrest warrant.” Karen thought about her kids. She says, “I didn’t want them to have the childhood that I had to deal with growing up with drug addicts, drug dealers.”15

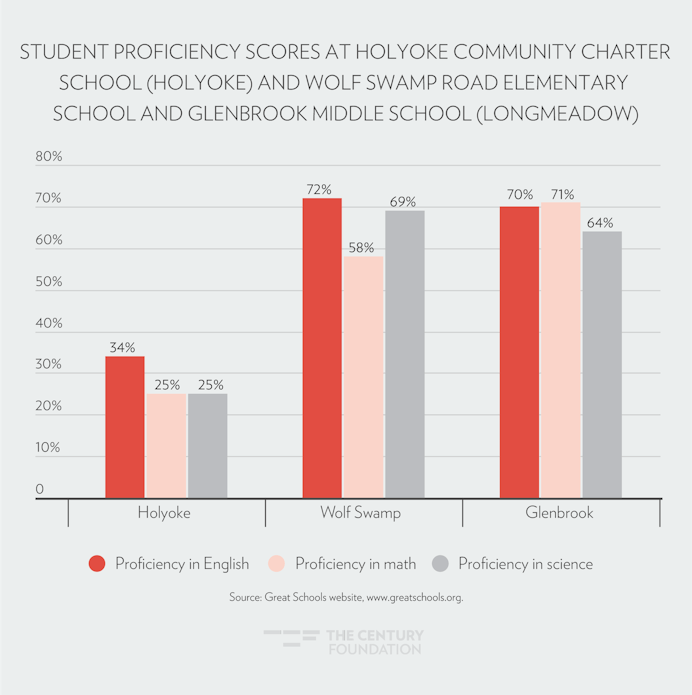

She says she was also “unhappy” with the education that her children were receiving at Holyoke Community Charter School, which serves K–8 students in nearby Holyoke, Massachusetts.16 At the school, where 86 percent of students are low income, just 34 percent of students are proficient in English, 25 percent in math, and 25 percent in science.17 “I have to get out of here,” she said to herself.18

Samantha

Samantha, who works with stroke patients in a rehabilitation hospital, is a native of Springfield, Massachusetts.19 She grew up in Massachusetts’s third-largest city, “not in the best areas.”20 Her father, a mechanic, died when she was age 10, and her mother was disabled and couldn’t work, so after her father’s passing, they lived in public housing.21 “In Springfield, it was difficult,” she says.22 Samantha attended Springfield public schools, including Springfield’s High School of Commerce, but did not have a good experience.23 “I got up to eleventh grade,” she says, but dropped out because of rowdiness in the school.24

A single mother, Samantha now has three children, Desmond, who is in tenth grade, Zivianna, who is in fifth grade, and Adrian, who is in fourth grade.25 Her oldest son, Desmond, is severely autistic, and her daughter, Zivianna, has a more modest form of autism.26 Samantha is white and she describes her children as “mixed. They’re Spanish and white.”27

Springfield, which has struggled economically, had a median household income of $39,432 in 2019, less than half the state’s median income.28 The schools have the second-highest concentration of low-income students in the state of Massachusetts (after Holyoke).29 Samantha said the neighborhood where she was raising her kids saw shootings and drug activity and “the street was a little dangerous. People were just flying down the road.”30 FBI statistics for 2019 found there were 91 violent crimes per 10,000 people in Springfield, compared with 6 per 10,000 in nearby Longmeadow.31 As a result, she says, “I always kept my kids home.”32

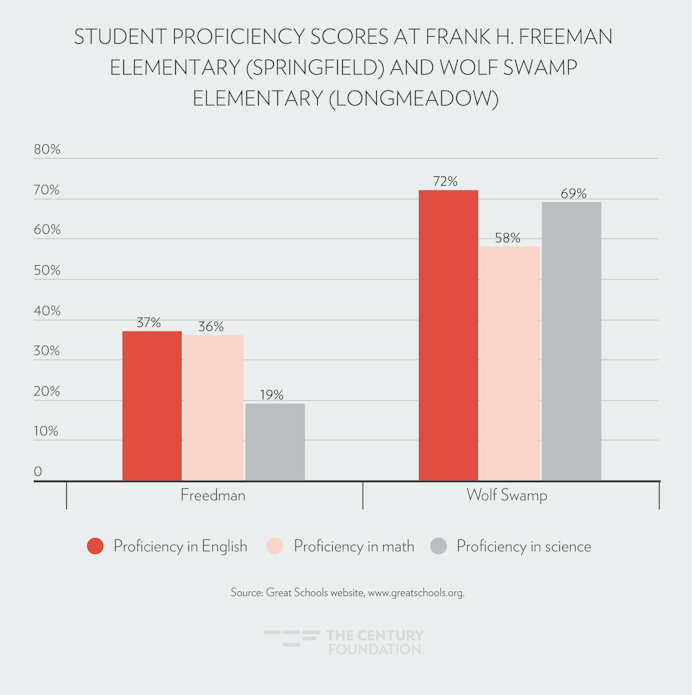

The children attended three schools, all of which perform considerably below the state average on standardized test scores: Frank H. Freedman Elementary, where 78 percent of students are low-income and 36 percent are proficient in math, 37 percent in English, and 19 percent in science;33 Elias Brookings Elementary, where 86 percent of students are low-income and 22 percent are proficient in math, 28 percent in English, and 19 percent in science;34 and Springfield Public Day Middle School, where 90 percent of students are low income and virtually none of the students are proficient in English, math or science.35 Samantha was distressed with the education that her children were receiving.36

Springfield Day Public Middle School was an especially bad fit for her son Desmond, she says. Samantha says it is the district’s school of last resort for unruly students, and wasn’t resourced to serve students who have special needs such as autism. “He was in crisis every day. I had to get him. He was in altercations or just having a bad day, which was because they put autistic children with other kids that just have bad behaviors, that didn’t like to go to school. So it didn’t mix.”37

The Invisible Walls That Exclude and Harm

Many will look at Karen and Samantha’s predicaments and attribute their exclusion from safer, higher-opportunity neighborhoods with good schools to the free market. Houses simply cost more in high-opportunity neighborhoods, that logic goes. But in fact, the exclusion of Karen and Samantha—and other mothers and families like them—is in large measure socially engineered. Government-sponsored exclusionary barriers, research finds, have an enormous impact on where people can live. Fully half of the differing levels of inequality between metropolitan regions is caused by exclusionary zoning.38

Exclusionary Zoning in Massachusetts

Kristin Haas of the Massachusetts Department of Housing and Community Development notes that across the state, “exclusionary zoning continues to be a huge, huge problem.”39 She says, “We have lots of communities that are primarily zoned for single family homes, and it’s really hard” for low-income families “to have any opportunities in those types of communities.” Because there are so few multifamily units available, those that do become available have rents that “are just astronomical.”40 Indeed, the Metropolitan Area Planning Council found that in the decade between 2007 and 2017, 200 of the state’s 351 cities and towns did not build any new multifamily housing.41

In Western Massachusetts, where Karen and Samantha live, exclusionary zoning helps explain why low-income families are congregated in higher-poverty areas such as Springfield and Chicopee rather than surrounding communities. Springfield has “tons of apartments,” says Haas, but the surrounding suburbs have very few.42 “As soon as you get outside of Springfield, it’s almost entirely single family homes.”43 Haas, who directs the SNO Mass housing mobility program, says, “We’ve struggled mightily in the Springfield area in Western Massachusetts to find apartments” in high-opportunity areas, Haas says.44 Over a two-year period, only six families have been able to move to higher-opportunity neighborhoods in the Springfield area. “That’s a very small number given that we have two staff that are 100 percent dedicated to SNO Mass,” she says. “We’re just kind of floored how few families were finding anything.”45

People like Grace Perez, who lives north of Boston, face the same sorts of exclusionary zoning barriers in wealthy communities. Indeed, researchers have recognized the Boston region as having relatively high levels of exclusionary zoning when compared with other big cities nationally.46

The wealthier the suburb, the more likely they are to engage in the practice of exclusionary zoning. Compare, for example, the Boston suburbs of Lexington (median income of $186,000) and Waltham (median income of $96,000). Boston University political scientists Katherine Levine Einstein, David M. Glick, and Maxwell Palmer report that if a developer wants to build a triplex, she would face a far different set of rules in the two municipalities. In Waltham, a three-family home requires a minimum of a 6,000 square foot lot; for Lexington, the same home would need a minimum lot of 15,500 square feet, thus driving up the price of any such development, perhaps even beyond affordable rates. In Waltham, building a triplex requires no special permit; in Lexington, all multifamily developments require a special permit. Overall, a builder in Waltham must comply with seventeen regulations, while in Lexington, a builder faces thirty-four regulations, which gives NIMBY Lexington residents far more tools to delay or stop a proposed project in its tracks. Einstein and colleagues note the bottom-line result: “in relatively unregulated Waltham, 65 percent of permitted units between 2000 and 2015 were for multifamily housing, and 35 percent were for single-family homes. Over the same time period, 94 percent of permitted units in Lexington were for single-family homes, and only 6 percent were for units in multifamily buildings.”47

Likewise, the affluent Boston suburb of Weston (median household income of $207,702 in 2019), engages in much more exclusionary zoning than the comparatively diverse city of Cambridge (median household income of $103,154).48 For example, the two municipalities, located just fifteen miles apart, have wildly different lot size requirements for multifamily homes. In Cambridge, the minimum lot size is 900 square feet, while in Weston, it is 240,000 square feet, some 267 times higher.49

The two municipalities, located just fifteen miles apart, have wildly different lot size requirements for multifamily homes. In Cambridge, the minimum lot size is 900 square feet, while in Weston, it is 240,000 square feet, some 267 times higher.

Affluent and white families are particularly likely to exploit zoning laws to kill projects, Einstein and colleagues find. Looking at the minutes from zoning and planning meetings in ninety-seven Massachusetts municipalities, the researchers found that older, male, white homeowners tended to dominate discussions. In Lawrence, Massachusetts, where the population is 75 percent Latinx, for example, over a three-year period, only one resident with an Hispanic surname ever spoke at planning and zoning meetings.50

Exclusion is a slippery process, fair housing advocates note, and can occur even in communities that permit multifamily housing. In such cases when multifamily housing is allowed, says Dana LeWinter of the Citizens’ Housing and Planning Association (CHAPA), a nonprofit organization that supports affordable housing, municipalities often seek to limit the number of bedrooms in apartments in order to reduce the presence of children. The issue “comes up all the time,” she says.51

The Damage Done by Exclusionary Zoning in Massachusetts

Exclusionary walls built by local Massachusetts communities cause considerable damage to people like Karen, Samantha, and Grace Perez. Research finds they segregate communities, stunt opportunity, and drive up housing prices.

Indeed, the Boston area, where exclusionary zoning is prevalent, is facing a significant rise in income segregation. According to 2016 research from Kendra Bischoff of Cornell and Sean Reardon of Stanford, the number of families in Boston and surrounding suburbs who live in mixed-income neighborhoods declined from 7 in 10 families in 1970 to 4 in 10 in recent years. The percent living in high-poverty neighborhoods rose from 8 percent to 20 percent during that time period, while the proportion living in concentrated wealth increased from 6 percent to 16 percent.52 Economic segregation such as this is especially harmful because where families live helps determine the life prospects of their children. Harvard University’s Raj Chetty and colleagues, for example, have found that when low-income children move before age 13 to more affluent neighborhoods, their chances of going to college increase by 16 percent and their income as adults rises by 31 percent. Over a lifetime, that translates into $300,000 in additional income.53

Exclusionary zoning in Massachusetts, by artificially limiting the number of housing units that can be built, drives up housing prices.

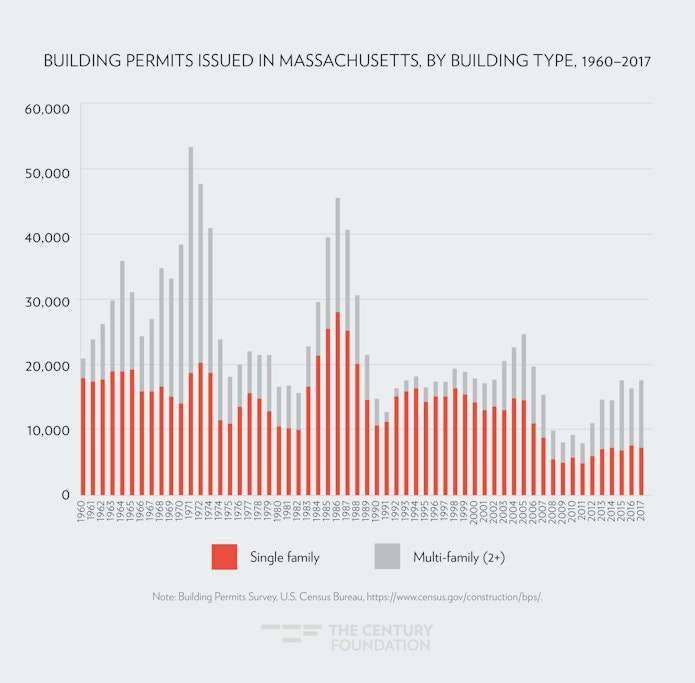

Likewise, exclusionary zoning in Massachusetts, by artificially limiting the number of housing units that can be built, drives up housing prices. Between 1960 and 1990, builders created 900,000 net new homes in Massachusetts, says Chris Kluchman of the Massachusetts Department of Housing and Community Development, but in the most recent three decades, between 1990 and 2017, Massachusetts has built fewer than 450,000 new homes.54 (See Figure 1.) In order to keep up with demand, planning agencies in the state estimate that 435,000 new housing units need to be built by 2040.55

FIGURE 1

The constraint on supply has had a highly predictable result. In a 2020 study of housing affordability by Moody Analytics and U.S. News & World Report, Massachusetts ranked forty-eighth of fifty states, making it one of the least affordable states in the country for housing.56 The median price for single-family homes in the state exceeds $500,000.57 In Boston, the percentage of homes in the metropolitan area that cost $1 million has nearly doubled in five years.58

Source-of-Income and Racial Discrimination by Landlords

In addition to government-sponsored exclusionary zoning, people like Karen, Samantha, and Grace Perez face discrimination in the private marketplace by landlords and real estate agents. Although source-of-income discrimination (including discrimination against Section 8 Housing Choice Voucher holders) and racial discrimination are both illegal in Massachusetts, new research finds that both are commonplace there and in other states.59

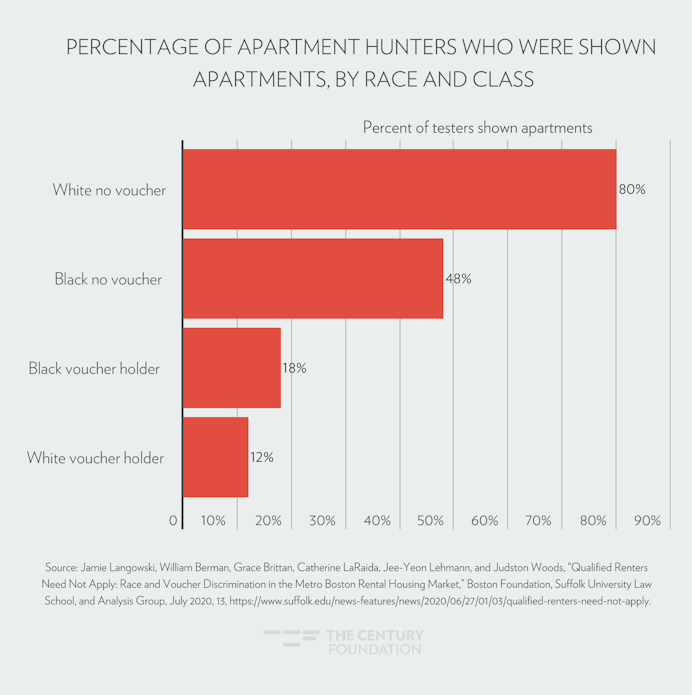

A July 2020 study by researchers with Suffolk University Law School, the Boston Foundation, and Analysis Group sought to test the degree to which real estate brokers and landlords discriminate on the basis of race and source of income in Boston and nine area suburbs.60 The researchers tried to disentangle race and source-of-income discrimination by placing 200 fictional renters into four groups of fifty each: white people who could pay market rent; Black people who could pay market rent; white people with a Section 8 Housing Choice Voucher; and Black people with a Section 8 Housing Choice voucher.61

The researchers found an unconscionable amount of racial discrimination: White renters paying market rate were shown apartment 80 percent of time, while Black renters paying market rate were shown apartments only 48 percent of the time. But the impact of class was even stronger. Black voucher holders were shown apartments just 18 percent of the time, and white voucher holders fared the worst, being shown apartments only 12 percent of the time.62 (See Figure 2.)

FIGURE 2

In all, the researchers found, voucher holders were ultimately turned away from apartments nine times out of ten.63 They noted, “People should not have to contact ten housing providers in order to see one unit.”64 Voucher-based discrimination was “more explicit” than racial discrimination, the researchers found. “About 40 percent of the time, the housing provider stopped communicating with testers altogether after the testers revealed they intended to use vouchers.”65

Haas of the Department of Housing and Community Development said that in her experience working with Section 8 Housing Choice Voucher holders, source-of-income discrimination “is often overt,” such as “a listing that says ‘No Section 8.’”66 She says online applications are also troubling. They will often ask renters to list their income, but include no place for applicants to note that payments will include a Section 8 housing subsidy. As a result, applicants are summarily dismissed because it looks “like they in no way can afford the rent,” Haas says.67

Even when source-of-income discrimination is blatant, Haas notes, Section 8 voucher holders often decide not to file a complaint. Voucher holders “are really focused on their housing search. They have a lot of other things going on typically, and are not necessarily going to take the time or feel comfortable reporting something to some authorities.”68 Voucher holders have a limited amount of time to use their voucher, so participants often “just want to move on to the next potential apartment and not get bogged down pursuing something that probably is not going to get them an apartment immediately.”69 Department of Housing and Community Development staff typically don’t file complaints on voucher holders’ behalf, so if the voucher holders chooses not to file a complaint, the discrimination may go unreported, she says.70

Dana LeWinter of the nonprofit CHAPA says the issues of exclusionary zoning and source-of-income discrimination are connected. “When there is not enough housing supply, landlords may feel more confident to discriminate as they know there is ample demand for their apartments.”71

Getting Around the Walls, via SNO Mass

In 2019, recognizing the numerous barriers that people like Karen, Samantha, and Grace Perez face, Massachusetts created a new housing mobility program, SNO Mass (Supporting Neighborhood Opportunity in Massachusetts), to help families get around the walls built by local governments.72

The SNO Mass Program

To its credit, SNO Mass was created voluntarily, in contrast to the housing mobility programs in places such as Dallas, Baltimore, and Chicago, which were ordered by federal judges as remedies for purposeful segregation of housing in the past. Haas says, there was “a recognition that our voucher holders were disproportionately concentrated in high poverty neighborhoods” which was a violation of the “choice” principle of the Housing Choice Voucher program.73 A 2019 study of the nation’s fifty largest metropolitan areas found that only 5 percent of Housing Choice Voucher families live in high-opportunity neighborhoods.74

The SNO Mass program was also inspired by Raj Chetty research, finding that mobility programs are especially beneficial to children. SNO Mass focuses on families with at least one child under the age of 18 who are living in low-opportunity neighborhoods and would like to move to higher-opportunity areas. The program provides several benefits: a counselor to support finding available landlords in high-opportunity areas and negotiating contracts; a higher voucher value in certain communities; financial assistance with moving costs and security deposits; and post-move counseling services. For landlords, the program provides up to a $1,000 financial incentive and expedites the process for approval to serve Section 8 clients.75 Higher-opportunity neighborhoods are identified using the Child Opportunity Index, created by DiversityDataKids.org at Brandeis University. The index includes twenty-nine factors measuring education, health and environment, and social and economic indicators.76 Mobility Works, a national nonprofit, provided technical assistance in setting up the program.77 SNO Mass is administered at the regional level by the Massachusetts Department of Housing and Community Development’s Regional Administering Agencies, which are nonprofit housing organizations. In the Springfield area, the program is administered by Way Finders.78 In the North Shore of Boston and Merrimack Valley, Community Teamwork, Inc. serves families.79

One of the major roadblocks to finding rental units for SNO Mass participants is exclusionary zoning laws that have prevented construction of more affordable types of housing in high-opportunity neighborhoods.

When the program began in the summer of 2019, there was a question of how many families would want to participate and uproot themselves from existing communities and networks of friends.80 But Haas says: “We’ve seen a ton of interest from eligible families.”81 About one in five families contacted has expressed interest.82 There are about 6,200 families statewide who are eligible because they currently live in low-opportunity neighborhoods and have children under age 18. SNO Mass staff have been contacting families gradually so as not to create a long waiting list of disappointed individuals. Some 235 families have completed three required counseling sessions, and 45 of those have been placed in high-opportunity neighborhoods so far.83 The SNO Mass program has fourteen dedicated staff members across the state, and a total budget in excess of $2 million.84 One of the major roadblocks to finding rental units for SNO Mass participants is exclusionary zoning laws that have prevented construction of more affordable types of housing in high-opportunity neighborhoods, Haas says.85

How SNO Mass Changed the Lives of Three Families

Karen

When Karen was enrolled in the SNO Mass program through Way Finders in 2019, she jumped at the chance to move to Longmeadow, a community whose median household income of $122,035 in 2019 was more than double that of Chicopee’s.86 “It’s a lot safer here,” she says. “Everybody kind of knows each other.” The kids “get in a group and start riding around” on their bikes, she says. “I can let my kids be free. As long as they have their phones on them, I’m fine.”87

In Longmeadow, Karen’s children, now in third, fourth and seventh grade, attend Wolf Swamp Road Elementary School and Glenbrook Middle School, both of which have lower concentrations of poverty than the Holyoke Community Charter School they previously attended, and higher test scores.88 (See Figure 3.) Karen is thrilled with the Longmeadow public schools. “I absolutely love them,” she says.89

Figure 3

The class sizes at Wolf Swamp and Glenbrook Middle are smaller, and the teachers are “more attentive” than those at Holyoke Charter.90 The parents are also more involved, Karen says.91 “In Holyoke, it wasn’t even the parents that were in the PTA meeting; it was mostly teachers. It was like maybe one or two parents there,” she notes. In Longmeadow, by contrast, the parents are in regular contact with one another. I “constantly get emails about, ‘Hey, there’s this ice cream social night,’ or ‘there’s this fundraiser we’re doing for the kids.’”92

Karen also said she likes the fact that in Longmeadow, her children, who identify as Hispanic, are exposed to classmates who come from all races and ethnicities. Whereas at Holyoke Community Charter, 92 percent of students shared a Hispanic heritage with her children, in Longmeadow, the Hispanic student population is 6 percent at Wolf Swamp Elementary and 6 percent in Glenbrook Middle. Both schools have larger white, Asian, and Black populations than Holyoke Charter, so her children have a greater chance to learn about other cultures, she says.93

Samantha

When Samantha heard that the SNO Mass program would give her a chance to live in Longmeadow, which has a median household income triple that of Springfield, she was excited.94 She says: “I always wanted to live in a better area than Springfield.” She explains that as a child she went trick or treating in areas like Longmeadow, “I always wished I could live out here.”95 Unlike Springfield, where Samantha kept her kids mostly in the house, in Longmeadow, “they’re happier. They can explore, they can do much more than they ever did before.”96 She continues, “There’s so many parks. It’s really not crowded. And . . . the people are very friendly.”97 Through SNO Mass, Samantha is able to rent a single-family home with an above-ground pool and provide her kids with a type of experience she never had growing up.

The education provided in Longmeadow is also much better, she says. “The schools have the number one ratings out here,” and they are well designed to address students with special needs.98 Zivianna and Adrian attend Wolf Swamp Road Elementary School (which some of Karen’s children also attend), where 7 percent of students are low-income and 58 percent are proficient in math, 72 percent in English, and 69 percent in science.99 Desmond attends Longmeadow High School, where 6 percent of students are low income and 79 percent are proficient in math, 80 percent in English, 52 percent in science, and 49 percent in biology—all far above the state average, and higher than in their previous school, Frank H. Freeman Elementary in Springfield.100 (See Figure 4.)

FIGURE 4

Samantha senses that the teachers in Longmeadow are much more interested in her kids, particularly Desmond. The teachers, she says, “keep in touch, on a daily basis, even right now in the summer, the teachers are emailing me, like, ‘How’s your son. Are you doing okay?’” Whereas some of the teachers in Springfield, “didn’t care, honestly.” Samantha is struck that, in Longmeadow, “even though the teachers are off the clock, they still communicate with the moms that have children with special needs.”101 She is impressed by their dedication. Even during summer break, she says, “They will gladly do a zoom call” with Desmond. “And that’s awesome.”102

The transformation for Desmond has been dramatic. In Longmeadow, Samantha says, he stopped acting out. She marvels: “my son, actually, for the first time ever, when we moved here, he actually looked forward to going to school, even during the pandemic.” He would ask Samantha, when schooling was online-only to reduce the spread of COVID 19: “Why can’t I just go to school? I want to go to school. I miss my teachers.” She says: “you would never have had that if we lived back in Springfield…. it’s totally different. I don’t have to really worry.”103 Since the move, Samantha says, “He’s toned down like a lot. Friends and family even said [that they see] a dramatic change in his behavior, his mood and it’s honestly the school.”104

In moving to Longmeadow, Samantha’s big worry was that because she has a low income, and because her children have a Hispanic father, they might be poorly treated by neighbors and school classmates. “I was scared about that,” she says. But it turned out, “the neighbors are great. They’re not judgmental to other kids. They play with my kids perfectly fine.”105 Overall, she concludes: “Longmeadow is like one of the greatest moves that I ever did.”106

Grace Perez

Grace Perez, who lives outside of Boston, had a somewhat different experience with SNO Mass than Karen or Samantha. A former corrections officer, Perez is a single mother of two children: a 9-year old boy, Jace, who is in third grade, and a young baby girl, Giana.107

The daughter of immigrants from the Dominican Republic, Perez grew up in Lawrence, Massachusetts, located just south of the New Hampshire border. Her father was a factory worker and her mother worked for the phone company, AT&T.108 She received an associates’ degree in law enforcement from Hesser College, a for-profit institution, and for almost ten years, she served as a corrections officer at a maximum security facility in Massachusetts and then across the border in nearby Brentwood, New Hampshire.109 Perez says she was financially stable and developed a good credit rating and was able to rent a market-rate apartment in Haverhill, Massachusetts, which is located right next to Lawrence, but has a somewhat more affluent population.110 With a degree in hand and a steady job, she was well positioned financially. “I’d never heard of Section 8,” she recalls. “I’d never heard of food stamps or WIC or none of that stuff.”111

In late March 2012, disaster struck when a fire swept through her apartment.112 She did not have renter’s insurance, and says she “lost everything.”113 A few days later, she found out she was pregnant with Jace. She moved in with Jace’s father and stayed seven months.114 “But it was not a healthy relationship,” she says.115 She came to realize that her partner would not be a good influence on her new baby.116 “My world flipped on me,” she says.117

After Jace was born, Perez says, continuing to work as a corrections officer over time proved impossible given the hours and working conditions.118 When Jace was about six months old, she moved into a homeless shelter in Danvers, Massachusetts, a middle-class town north of Boston.119

Eventually, she received a Section 8 Housing Choice Voucher and rented an apartment in Conifer Hill Commons, a housing development in Danvers.120 Jace attended kindergarten at the local elementary school, Ivan Smith, which Perez liked, but she detested her apartment, which she says had “a lot of problems,” including a leaking ceiling.121 She wanted a change.

When she heard about the SNO Mass program, which would provide her some extra funds on top of Section 8 (such as moving expenses and the security deposit) she was excited about moving to a new place.122 In 2019, when SNO Mass staff showed her an apartment in Swampscott, Massachusetts, an affluent community with high performing public schools, she was initially impressed. “The apartments are so beautiful,” she says.123 She was excited to have a chance to live in an affluent community with strong schools that also was considered politically liberal. In 2020, Swampscott supported Joe Biden over Donald Trump by 72 percent to 27 percent.124 In 2019, she and Jace moved, and he began as a student at Hadley Elementary, where 81 percent of students are proficient in English and 61 percent are proficient in math, far exceeding the state average.125

Perez’s initial high hopes, however, were soon dashed. One challenge involved balancing work and child care needs in her new location. Years earlier, Perez had left her job as a corrections officer to work at Goodwill in Danvers because the hours were more flexible and better accommodated her need to be available for Jace.126 But in Swampscott, even the Goodwill job became difficult to juggle. Swampscott, where the median family income was $113,407 in 2019, was not set up well for people with economic needs like Perez, she says.127 The town only had a small number of state-funded vouchers for child care, she says. And Hadley Elementary was not designed to accommodate people who worked and lacked child care. School ended around 1:30 p.m., so Perez would race from her morning job at Goodwill to pick Jace up from school. “I was rushing through traffic. I was like, no, I can’t be doing this. I was always on the go.”128

Moreover, she says, many Swampscott residents she encountered were intolerant. In 2019, the town was racially homogenous: 91.7 percent of residents were white, and just 2.5 percent Hispanic, 2.2 percent Asian, and 1.5 percent Black.129 Moreover, Swampscott did not take kindly to newcomers, Perez says. “If you’re born and raised there, they’re fine with that. They don’t like the outcasts to come in. So they don’t like the fact that affordable housing was being brought there.”130 People in Swampscott were also unfamiliar with programs for low-income families, such as WIC and SNAP, Perez says.131

Worst of all, Perez says, her son Jace experienced blatant racism at Hadley, which is 80 percent white, 10 percent Hispanic, 3 percent Asian American, and 2 percent Black.132 In the summer of 2020, Jace appeared on the local Boston Channel 25 News discussing his feeling of isolation and the need for racial justice in the community. Perez, who describes herself as having dark skin and says she can pass for African American, says Jace, who has lighter skin, was called “Black boy” by his classmates and was bullied and hit.133 Perez complained about the racism to school officials. “I went to the principal. I went to the school. I spoke with teachers. They’re looking at me like my son is a problem.”134 She notes: “He developed anxiety. I had to get him therapy,” she says, “My son was miserable.”135

The situation had grown intolerable, and Perez asked her SNO Mass counselor if she could move to a nearby town, Beverly, Massachusetts, which is somewhat more economically and racially diverse than Swampscott.136 The median household income was $80,586 in 2019 and the population was 88.5 percent white, 5.1 percent Hispanic, 2.2 percent Asian, 2.1 percent Black, and 2.7 percent two or more races.137 Grace was able to make the move, and says her section of Beverly is more diverse than the north side of Beverly, which is overwhelmingly white and affluent.138 After she moved, Perez says Jace has faced none of the racism he experienced in Swampscott.

In Beverly, Jace attends Hannah Elementary. Perez says she loves the school. Hannah Elementary is somewhat more diverse than Hadley: the student population is 76 percent white, 14 percent Hispanic, 2 percent Black, 2 percent Asian or Pacific Islander, 6 percent two or more races. At the school, where 22 percent of students are low income, 59 percent of students are proficient in math, and 61 percent in English, both above the state average.139

“It’s a really wonderful, wonderful school,” Perez says. “The principal is amazing.” Perez says her son came in with an IEP (individual education plan) and had “difficulties with reading and writing,” but after just three months, “my son was reading and writing. . . . So I don’t know what was happening to the other schools because they kept treating him with delays and IEPs.”140

The teachers in Beverly have been very caring, Perez says. “They communicate everything with you on a daily basis.”141 The principal knows all the students by their first names and is welcoming to children of all backgrounds.142

The fact that Jace has not been subject to the wounding racism he says he experienced in Swampscott is by far the biggest difference. In fact, one day, Jace actually told his white principal at Hannah, “Thank you for not being racist to me.”143 Jace is flourishing, Perez says. “He’s now above the class,” Perez says. “He did so well” she says that the school gave Jace a scholarship to summer camp.

The Need for Broader Systemic Change

SNO Mass has improved the lives of Karen and Samantha, and (eventually) of Grace Perez too, but there are limits on the number of families SNO Mass can serve because exclusionary zoning has essentially capped the number of homes available in higher-opportunity neighborhoods, even with the extra financial support SNO Mass provides.

More fundamentally, while SNO Mass provides a vital catapult for people like Karen, Samantha, and Perez to move to communities such as Longmeadow and Beverly, the walls surrounding exclusionary communities remain. While forty-five families currently benefit from SNO Mass statewide, hundreds of thousands of low-wage families remain cut off from opportunity, in part because of local zoning laws that are designed to keep them out.

What can be done? To begin with, Massachusetts can build upon and expand a couple of good programs that it has established. To its credit, for example, Massachusetts passed an anti-snob-zoning law in 1969 that empowered the state to alter local zoning laws in communities where less than 10 percent of housing stock is deemed affordable and where developers have proposed that at least 20–25 percent of new units be affordable. In 2010, an effort to overturn the law through a statewide referendum was opposed by 58 percent of voters.144

Likewise, in January 2021, Massachusetts Governor Charlie Baker, a Republican, signed into law a Housing Choice Initiative to reduce exclusionary zoning and increase housing production. The legislation, which was part of a larger economic development law, eliminated a major impediment to building—a requirement that localities approve zoning changes with a two-thirds supermajority rather than a simple majority.145 The housing choice legislation also provides $2 million in grants for municipalities that build diverse housing stock.146

But much more needs to address the rising economic segregation and housing affordability crisis that Massachusetts faces. Democratic State Senator Harriette Chandler, for example, has proposed legislation to reduce barriers to development “such as restrictive zoning practices” that “require single-family houses on large lots and prohibit multifamily housing or ‘in-law’ apartments”147 Likewise, CHAPA is supportive of legislation introduced by State Representatives Andy Vargas and Kevin Honan and Senator Brendan Crighton that would increase the production of affordable housing and remove exclusionary zoning by, among other things, “requiring multi-family zoning around public transportation or other suitable locations in all municipalities”; “allowing inclusionary zoning bylaws to be enacted with a simple majority vote”; and “allowing accessory dwelling units (ADUs) to be built by-right in every municipality.”148

In addition, Massachusetts could enact an Economic Fair Housing Act, to give plaintiffs who are hurt by exclusionary zoning laws the chance to sue municipalities for income discrimination, the way racial minorities can sue for race discrimination. The Century Foundation proposed such legislation at the federal level in 2017, and the Equitable Housing Institute has developed the proposal into statutory language.149 Just as states have enacted fair housing laws that mirror and amplify the federal Fair Housing Act, so Massachusetts and other states could enact state-level Economic Fair Housing Acts.

While tackling exclusionary zoning was long seen as a political “third rail,” change is in the air. The coalition to promote smart growth and curtail exclusionary zoning in Massachusetts includes environmentalists, affordable housing advocates, and business leaders, among others. In addition, Andre Leroux, director of the Massachusetts Smart Growth Alliance, a public interest coalition of housing and environmental groups, notes that public health advocates are playing a key role given evidence that housing instability increases health care costs.150

Nationally, Yes in My Backyard (YIMBY) forces have defeated NIMBY voices to legalize duplexes and other multifamily units in areas previously reserved exclusively for single-family homes in Minneapolis, Minnesota in 2018; Oregon in 2019; and Charlotte, North Carolina and California in 2021.151 At the federal level, President Biden’s pared-back “Build Back Better” legislation includes funds for an “Unlocking Possibilities Program” to encourage “state and local zoning reforms that enable more families to reside in higher opportunity neighborhoods.”152 And in the Congress, the House of Representatives recently held a hearing, “Zoned Out: Examining the Impact of Exclusionary Zoning on People, Resources, and Opportunity,” which featured bipartisan support for reducing exclusion. House liberals championed zoning reform as a way to combat racial and economic segregation and improve opportunities, while conservatives supported reform as a form of government deregulation to lower housing prices.153

The Massachusetts story outlined in this report also raises interesting possibilities about new political coalitions to combat exclusionary zoning. Whereas the Boston busing saga of the 1970s divided working-class white and Black people, fights over zoning reform today could bring together white workers like Samantha and workers of color like Karen and Grace Perez. J. Anthony Lukas, author of Common Ground, a book about the Boston busing crisis, asked: “What kind of alliance could be cobbled together from people who feel equally excluded by class, or by some combination of class and race?”154 The first step, as Robert Coles pointed out a half century ago, is to see the exclusionary walls that keep working-class people of all races separated from opportunity. Samantha, Karen, and Grace Perez, and their children, like Ruby Bridges before them, have won small victories, but millions of others deserve more.

Notes

- See Richard D. Kahlenberg, “Harvard’s Class Gap: Can the academy understand Donald Trump’s ’forgotten’ Americans?” Harvard Magazine, May–June 2017.

- See e.g. Robert Coles, “In the South These Children Prophesy,” Atlantic, March 1963, 111–16; Jennie Rothenberg Gritz, “How Kids Dealt With the Stress of Desegregation,” Atlantic, January 19, 2014, https://www.theatlantic.com/education/archive/2014/01/how-kids-dealt-with-the-stress-of-desegregation/283146/; and Robert Coles, The Story of Ruby Bridges (New York: Scholastic Press, 1995).

- A very small number of Black students were permitted to attend the school’s affluent suburbs such as Wellesley as part of the METCO program, but these students and their families were not permitted to actually live in the neighborhoods. Instead, they had to take long bus rides each day to commute back and forth.

- See J. Anthony Lukas, Common Ground: A Turbulent Decade In the Lives of Three American Families (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1985), 244–45. For 2019 demographic data, see U.S. Census Bureau, “QuickFacts: Wellesley, CDP, Massachusetts,” https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/wellesleycdpmassachusetts.

- Mike Barnicle interview with Robert Coles, “Busing Puts Burdens on Working Class, Black and White,” Boston Globe, October 15, 1974, 23.

- Barnicle interview with Coles “Busing Puts Burdens.”

- See, e.g., Sean F. Reardon, Elena Tej Grewal,Demetra Kalogrides, and Erica Greenberg, “Brown Fades: The End of Court-Ordered School Desegregation and the Resegregation of American Public Schools,” Journal of Policy Analysis and Management, July 2012, https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/pam.21649.

- I want to express enormous gratitude to Karen, Samantha, and Grace Perez for sharing their stories, and to Michelle Burris, who was a part of the interviews I conducted with them. Michelle worked tirelessly to identify individuals for The Century Foundation’s “Voice of the Excluded” project.

- Karen interview with Michelle Burris and Richard Kahlenberg, August 2, 2021, 1–2.

- Karen interview, 8, 1.

- U.S. Census Bureau, “Quick Facts: Chicopee City, Massachusetts,” https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/chicopeecitymassachusetts/PST045219; and U.S. Census Bureau, “Quick Facts: Massachusetts,” https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/MA/INC110219.

- Karen Interview, 6.

- Karen Interview, 6.

- Karen Interview, 6.

- Karen Interview, 6–7.

- Karen Interview, 3

- “Holyoke Community Charter School,” Great Schools website, https://www.greatschools.org/massachusetts/holyoke/3230-Holyoke-Community-Charter-School/.

- Karen Interview, 1, 6–7.

- Samantha Interview with Michelle Burris and Richard Kahlenberg, August 3, 3021..

- “Top 245 Cities in Massachusetts by Population,” World Population Review, https://worldpopulationreview.com/states/cities/massachusetts; Samantha Interview, 1.

- Samantha Interview with Michelle Burris and Richard Kahlenberg, September 2, 2021 (Interview II), 1–2.

- Samantha Interview, 6.

- Samantha Interview II. 2.

- Samantha Interview, 1, 6.

- Samantha Interview II, 3.

- Samantha Interview, 2,7; Samantha Interview II, 3.

- Samantha Interview, 4, 7.

- “Quick Facts: Springfield City, Massachusetts,” U.S. Census Bureau, https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/springfieldcitymassachusetts,US/PST045219; and “Quick Facts: Massachusetts,” U.S. Census Bureau, https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/MA/INC110219 (state median income is more than $81,000).

- Jeanette DeForge, “War on Poverty: Poor schoolchildren face hunger, limited vocabulary, host of problems,” MassLive, March 24, 2019, https://www.masslive.com/news/2015/01/springfield_holyoke_schools_am.html.

- Samantha Interview II, 4.

- “2019 Crime in the United States: Massachusetts Offenses Known to Law Enforcement by City,” Federal Bureau of Investigation, Uniform Crime Report, Table 8, https://ucr.fbi.gov/crime-in-the-u.s/2019/crime-in-the-u.s.-2019/tables/table-8/table-8-state-cuts/massachusetts.xls.

- Samantha Interview, 6.

- “Frank H. Freedman,” Great Schools website, https://www.greatschools.org/massachusetts/springfield/1537-Frank-H-Freedman/.

- “Elias Brookings,” Great Schools website, https://www.greatschools.org/massachusetts/springfield/1536-Elias-Brookings/.

- “Springfield Public Day Middle School,” Great Schools website, https://www.greatschools.org/massachusetts/springfield/5408-Springfield-Public-Day-Middle-School/; Samantha Interview, 3.

- Samantha Interview, 3.

- Samantha Interview, 3.

- Jonathan Rothwell and Douglas Massey, “Density Zoning and Class Segregation in U.S. Metropolitan Areas,” Social Science Quarterly 91, no. 5 (December 2010): 1123–43, http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3632084/ (“a change in permitted zoning from the most restrictive to the least would close 50 percent of the observed gap between the most unequal metropolitan area and the least, in terms of neighborhood inequality”).

- Kristin Haas, Interview with Michelle Burris and Richard Kahlenberg, September 1, 2021, 1. For a very comprehensive analysis, see also Amy Dain, “The State of Zoning for Multi-Family Housing In Greater Boston,” Massachusetts Smart Growth Alliance, June 2019,

https://ma-smartgrowth.org/resources/resourcesreports-books/.

- Haas Interview, 1.

- Renée Loth, “Zoning reform offers a path to economic equality and social integration,” Boston Globe, January 16, 2018 (“According to the Metropolitan Area Planning Council, 200 of the state’s 351 cities and towns haven’t built any new multifamily housing in the past 10 years”).

- Haas Interview, 8–9.

- Haas Interview, 10.

- Haas Interview, 8.

- Haas Interview, 8.

- Rolf Pendall, Robert Puentes, and Jonathan Martin, “From Traditional to Reformed: A Review of Land Use Regulations in the Nation’s 50 Largest Metropolitan Areas,” The Brookings Institution, 2006.

- Katherine Levine Einstein, David M. Glick and Maxwell Palmer, Neighborhood Defenders: Participatory Politics and America’s Housing Crisis (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2020), 58–59.

- “QuickFacts: Weston Town, Middlesex County, Massachusetts,” U.S. Census Bureau, https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/westontownmiddlesexcountymassachusetts,MA,US/PST045219; and “QuickFacts: Cambridge City, Massachusetts,” U.S. Census Bureau, https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/cambridgecitymassachusetts/PST045219.

- Einstein, Glick, and Palmer, Neighborhood Defenders, 62.

- Einstein, Glick and Palmer, Neighborhood Defenders, 103–5.

- Dana LeWinter interview with author, September 14, 2021.

- David Scharfenberg, “Boston’s struggle with income segregation,” Boston Globe, March 5, 2016, https://www.bostonglobe.com/metro/2016/03/05/segregation/NiQBy000TZsGgLnAT0tHsL/story.html.

- Raj Chetty, Nathaniel Hendren, Lawrence Katz, “The Effects of Exposure to Better Neighborhoods on Children: New Evidence from the Moving to Opportunity Experiment,” National Bureau of Economic Research, Working Paper 21156, May 2015, 2. The paper subsequently appeared in American Economic Review 106, no. 4 (April 2016): 855–902, https://opportunityinsights.org/paper/newmto/.

- Chris Kluchman, Interview with author, September 14, 2021. See also Chris Kluchman, “Housing Choice Initiative,” May 4, 2018, 7 https://www.chapa.org/sites/default/files/Chris%20Kluchman.pdf (showing annual housing production by decade 1960s-2010s).

- Renée Loth, “Zoning reform offers a path to economic equality and social integration,” Boston Globe, January 16, 2018.

- “Affordability Rankings,” U.S. News & World Report, https://www.usnews.com/news/best-states/rankings/opportunity/affordability. The study of housing affordability looked at 109 median housing prices compared with 2020 median family incomes and mortgage rates.

- “Massachusetts home sale prices continue to soar in the second half of 2021,” WCVB TV, September 5, 2021, https://www.wcvb.com/article/housing-headaches-massachusetts-home-sale-prices-continue-to-soar-in-the-second-half-of-2021/37614399.

- “Baker–Polito Administration Announces New Housing Choice Initiative,” State of Massachusetts Governor’s Office, December 11, 2017, https://www.mass.gov/news/baker-polito-administration-announces-new-housing-choice-initiative. See also Dante Ramos, “Go on, California—blow up your lousy zoning laws,” Boston Globe, January 14, 2018.

- The Fair Housing Act of 1968 outlawed discrimination based on race. In addition, Massachusetts outlawed source-of-income discrimination in 1971, and strengthened the law in 1989. A majority of states do not have such legislation. See “Expanding Choice: Practical Strategies for Building a Successful Housing Mobility Program. APPENDIX B: State, Local, and Federal Laws Barring Source-of-Income Discrimination,” Poverty & Race and Research Action Council, August 2021, 20–22, https://www.prrac.org/pdf/AppendixB.pdf (noting nineteen states and the District of Columbia have statutes outlawing source-of-income discrimination). See also Kayla Canne, “NJ lacks a strong undercover discrimination testing program: Here’s why it’s important,” Asbury Park Press, October 25, 2021, https://www.app.com/story/news/investigations/2021/10/26/nj-law-discrimination-fair-housing-undercover-testing-hud-section-8/8506799002/.

- Jamie Langowski, William Berman, Grace Brittan, Catherine LaRaida, Jee-Yeon Lehmann, and Judston Woods, “Qualified Renters Need Not Apply: Race and Voucher Discrimination in the Metro Boston Rental Housing Market,” Boston Foundation, Suffolk University Law School, and Analysis Group, July 2020, 13, https://www.suffolk.edu/news-features/news/2020/06/27/01/03/qualified-renters-need-not-apply.

- Langowski et al., “Qualified Renters Need Not Apply,” 12, 52.

- Langowski et al., “Qualified Renters Need Not Apply,” 7, 11.

- Langowski et al., “Qualified Renters Need Not Apply,” 28.

- Langowski et al., “Qualified Renters Need Not Apply,” 27.

- Langowski et al., “Qualified Renters Need Not Apply,” Study Summary, https://www.suffolk.edu/news-features/news/2020/06/27/01/03/qualified-renters-need-not-apply.

- Haas Interview, 2.

- Haas Interview, 2.

- Haas Interview, 3.

- Haas Interview, 3. See also Langowski et al., “Qualified Renters,” 25.

- Haas Interview, 3.

- Dana LeWinter, interview with Author, September 14, 2021.

- Haas Interview, 13.

- Haas Interview, 12.

- Alicia Mazzara and Brian Knudsen, “Where Families With Children Use Housing Vouchers

A Comparative Look at the 50 Largest Metropolitan Areas,” Center for Budget and Policy Priorities and Poverty & Race Research Action Council, January 3, 2019, 2, https://prrac.org/pdf/where_families_use_vouchers_2019.pdf. - “Supporting Neighborhood Opportunity in Massachusetts (SNO Mass Program),” State of Massachusetts, https://www.mass.gov/info-details/supporting-neighborhood-opportunity-in-massachusetts-sno-mass-program; and Kristin Haas, panelist, “A Conversation for Progress: Housing Mobility in Massachusetts,” Policy for Progress, May 24, 2021, https://us02web.zoom.us/rec/play/LwufQO-UAeGiwnusw-paI1VCa_6kfFrmsmH4vy_0ABAGdJ4bMyhaSWg-9eRfLrDIQiBxMDpMEG3eMHdV.mmKhiOVheHFp0WRV?startTime=1621864810000&_x_zm_rtaid=snEQCT73RmmSXz4EBCRY1A.1630085764058.28e41b8eb921bcb784eab82f1dd44046&_x_zm_rhtaid=936.

- “Supporting Neighborhood Opportunity in Massachusetts (SNO Mass Program),” State of Massachusetts, https://www.mass.gov/info-details/supporting-neighborhood-opportunity-in-massachusetts-sno-mass-program.

- See Mobility Works, https://www.housingmobility.org/.

- “Support for a Higher Quality of Life: SNO Mass Housing Mobility Program,” Way Finders, https://www.wayfinders.org/sno-mass-housing-mobility-program.

- “Supporting Neighborhood Opportunity in Massachusetts (SNO Mass Program),” State of Massachusetts, https://www.mass.gov/info-details/supporting-neighborhood-opportunity-in-massachusetts-sno-mass-program.

- Haas Interview, 13.

- Haas Interview, 13.

- Haas Interview, 13.

- Haas Interview, 14, 16.

- Haas Interview, 13, 17.

- Haas Interview, 14–15.

- Karen Interview, 1. “Quick Facts: Longmeadow CDP, Massachusetts,” U.S. Census Bureau, https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/longmeadowcdpmassachusetts/BZA010219.

- Karen Interview, 7.

- Karen Interview, 3. At Glenbrook Middle, 6 percent of students are low income and 71 percent proficient in math, 70 percent in English and 64 percent in science; “Glenbrook Middle,” Great Schools website, https://www.greatschools.org/massachusetts/longmeadow/925-Glenbrook-Middle-School/. At Wolf Swamp Road Elementary, 7 percent of students are low-income and 58 percent are proficient in Math, 72 percent in English and 69 percent in Science; “Wolf Swamp Road,” Great Schools website, https://www.greatschools.org/massachusetts/longmeadow/927-Wolf-Swamp-Road/.

- Karen Interview, 4.

- Karen Interview, 4.

- Karen Interview, 4.

- Karen Interview, 7.

- Karen Interview, 4. See “Holyoke Community Charter School,” Great Schools website, https://www.greatschools.org/massachusetts/holyoke/3230-Holyoke-Community-Charter-School/ (92 percent Hispanic, 4 percent White, 1 percent Black, 1 percent Asian or Pacific Islander, and 2 percent two or more races); “Wolf Swamp Road,” Great Schools website, https://www.greatschools.org/massachusetts/longmeadow/927-Wolf-Swamp-Road/ (75 percent white, 10 percent Asian or Pacific Islander, 6 percent Hispanic, 4 percent Black, and 5 percent two or more races); and “Glenbrook Middle,” Great Schools website, https://www.greatschools.org/massachusetts/longmeadow/925-Glenbrook-Middle-School/ (73 percent white, 14 percent Asian or Pacific Islander, 6 percent Hispanic, 4 percent Black, 3 percent two or more races and less than 1 percent Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander).

- “Quick Facts: Longmeadow CDP, Massachusetts,” U.S. Census Bureau, https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/longmeadowcdpmassachusetts/BZA010219

- Samantha Interview, 3.

- Samantha Interview, 6.

- Samantha Interview, 6.

- Samantha Interview, 3.

- “Wolf Swamp Road,” Great Schools website, https://www.greatschools.org/massachusetts/longmeadow/927-Wolf-Swamp-Road/.

- Samantha Interview, 2. “Longmeadow High School,” Great Schools website,

https://www.greatschools.org/massachusetts/longmeadow/926-Longmeadow-High-School/. - Samantha Interview, 7.

- Samantha Interview, 7.

- Samantha Interview, 3–4.

- Samantha Interview, 4.

- Samantha Interview, 7–8.

- Samantha Interview, 3.

- Grace Perez Interview with Michelle Burris and Richard Kahlenberg, August 12, 2021, 1, 5–6, 8.

- Perez Interview, 15; and Grace Perez Interview with Michelle Burris and Richard Kahlenberg, September 3, 2021 (Interview II), 1.

- Perez Interview, 1, 7; Perez Interview II, 1.

- Perez Interview, 1–2, 9; Perez Interview II, 2. In 2019, Lawrence had a median household income of $44,613, while Haverhill had a median household income of $69,426. See “Quick Facts: Lawrence, Massachusetts,” U.S. Census Bureau, https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/lawrencecitymassachusetts; and “Quick Facts: Haverhill, Massachusetts,” U.S. Census Bureau, https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/haverhillcitymassachusetts/PST045219.

- Perez Interview, 17.

- Perez Interview, 16.

- Perez Interview, 11.

- Perez Interview II, 2.

- Perez Interview II, 3.

- Perez Interview, 16.

- Perez Interview, 1.

- Perez Interview, II, 3.

- Perez Interview, 1, 9; Perez Interview II, 3. Danvers had a median household income of $89,250 in 2019; “Quick Facts: Danvers town, Essex County, Massachusetts,” U.S. Census Bureau, https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/danverstownessexcountymassachusetts/PST045219.

- Perez Interview II, 4.

- Perez Interview II, 4, 6.

- Perez Interview, 3–4.

- Perez Interview II, 9.

- Anthony Brooks, “Joe Biden Wins Massachusetts,” WBUR News, November 3, 2020, https://www.wbur.org/news/2020/11/03/joe-biden-election-massachusetts.

- Perez Interview II, 8; “Hadley Elementary School,” Great Schools website, https://www.greatschools.org/massachusetts/swampscott/1600-Hadley-Elementary-School/.

- Perez Interview II, 3, 7.

- “Quick Facts: Swampscott town, Essex County, Massachusetts,” U.S. Census Bureau, https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/swampscotttownessexcountymassachusetts.

- Perez Interview II, 7–8.

- “Quick Facts: Swampscott town, Essex County, Massachusetts,” U.S. Census Bureau, https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/swampscotttownessexcountymassachusetts.

- Perez Interview II, 9.

- Perez Interview, 12.

- Great Schools citation.

- Perez Interview, 11, 14–15; Perez Interview II, 9.

- Perez Interview, 21.

- Perez Interview, 11.

- Perez Interview, 14.

- “Quick Facts: Beverly City, Massachusetts,” U.S. Census Bureau, https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/beverlycitymassachusetts/NES010218.

- Perez Interview II, 10.

- “Hannah Elementary School,” Great Schools website, https://www.greatschools.org/massachusetts/beverly/202-Hannah-Elementary-School/.

- Perez Interview, 6.

- Perez Interview, 13.

- Perez Interview, 13.

- Perez Interview, 13.

- William Fischel, Zoning Rules! The Economics of Land Use Regulation (Cambridge, Mass.: Lincoln Institute of Land Policy, 2015), 150. See also Einstein, Glick, and Palmer, Neighborhood Defenders, 106–7.

- Steph Solis, “Massachusetts Gov. Charlie Baker signs $626 million economic development bill that spurs housing production, funds small business grants,” Mass Live, January 14, 2021, https://www.masslive.com/politics/2021/01/massachusetts-gov-charlie-baker-signs-626-million-economic-development-bill-that-spurs-housing-production-funds-small-business-grants.html.

- See “Housing Choice Initiative,” State of Massachusetts, https://www.mass.gov/orgs/housing-choice-initiative.

- Harriette L. Chandler and Jim O’Day, “As I see it: The housing cost crisis,” Worcester Telegraph, March 25, 2018.

- See “2021–2022 State Legislative Priorities,” Citizens’ Housing and Planning Association, https://www.chapa.org/sites/default/files/chapa-priorities-items-2021/2021%20Legislative%20Priorities%20Overview_6.21.2021.pdf.

- Richard D. Kahlenberg, “An Economic Fair Housing Act,” The Century Foundation, August 3, 2017, https://tcf.org/content/report/economic-fair-housing-act/; and “Economic Fair Housing Act of 2021, Partial Draft Bill and Comments,” Equitable Housing Institute, November 30. 2020, https://www.equitablehousing.org/images/PDFs/PDFs–2018-/EHI_Economic_FHA_of_2021_draft-rev_11-30-20.pdf.

- Author’s phone interview with André Leroux, February 23, 2018. See also Richard D. Kahlenberg, “Updating the Fair Housing Act to Make Housing More Affordable,” The Century Foundation, April 9, 2018, https://tcf.org/content/report/updating-fair-housing-act-make-housing-affordable/.

- See Richard D. Kahlenberg, “How Minneapolis Ended Single-Family Zoning,” The Century Foundation, October 24, 2019, https://tcf.org/content/report/minneapolis-ended-single-family-zoning/; Laura Bliss, “Oregon’s Single-Family Zoning Ban Was a ’Long Time Coming,’” CityLab, July 2, 2019, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2019-07-02/upzoning-rising-oregon-bans-single-family-zoning; Henry Grabar, “The Most Important Housing Reform in America Has Come to the South,” Slate, June 28, 2021, https://slate.com/business/2021/06/charlotte-single-family-zoning-segregation-housing.html; and Conor Dougherty, “Where the Suburbs End: A single-family home from the 1950s is now a rental complex and a vision of California’s future,” New York Times, October 8, 2021, https://www.nytimes.com/2021/10/08/business/economy/california-housing.html. The California legislation was signed by Governor Gavin Newsom over the objections of more than 260 city leaders. See Ben Fritz and Zusha Elinson, “California Limits Single-Family Home Zoning,” Wall Street Journal, September 16, 2021, https://www.wsj.com/articles/california-limits-single-family-home-zoning-11631840086.

- “President Biden Announces the Build Back Better Framework,” The White House, October 28, 2021, https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2021/10/28/president-biden-announces-the-build-back-better-framework/.

- “Zoned Out: Examining the Impact of Exclusionary Zoning on People, Resources, and Opportunity,” House Financial Services Committee, October 15, 2021, https://financialservices.house.gov/calendar/eventsingle.aspx?EventID=408494. See also Richard D. Kahlenberg, “Testimony: In Residential Zoning Policy, Congress Must Tear Down the Walls We Don’t See,” The Century Foundation, October 15, 2021, https://tcf.org/content/commentary/testimony-residential-zoning-policy-congress-must-tear-walls-dont-see/.

- J. Anthony Lukas, Interview with author, January 3, 1995. Quoted in Richard D. Kahlenberg, The Remedy: Race, Class, and Affirmative Action (New York: Basic Books, 1996), 191.