Introduction

All around us, online technology has disrupted business models and entire industries virtually overnight, dramatically changing the landscape for consumers and workers alike.

With just one click, you can summon a cab through Uber. At two clicks, Venmo allows you to instantly send cash to your kid away at college. At three clinks, Turbo Tax is preparing your returns, and at four clicks, you are on LegalZoom drafting your last will and testament. What if with five clicks, you and your coworkers could petition the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) to schedule a union election?

Due to a little-known, but far-reaching change made by the NLRB last year, virtual labor organizing by employees is now sanctioned by law in many situations and could possibly be transformative in the workplace.

Many employees want more clout at work—to leverage better pay and benefits, but also nonmonetary things, such as more predictable work schedules, or a stronger voice in workplace safety or procedures. And it is a good bet that many would join a union, if signing up were easier for workers to do, and harder for employers to stop.

The problem today is that joining a union at work is decidedly last century—clunky, contentious, confusing—and companies such as Walmart and McDonald’s want to keep it that way.

But virtual labor organizing could change that.

This report documents why joining a labor union is one of the best financial decisions a worker can make to boost individual and family wealth and describes how the creation of an online tool could assist employees who want to start a campaign to join a union at their workplace.

The Union Earnings Premium

The ability of employees to join a labor union is the single largest unclaimed legal right to additional personal wealth in America today. As surprising as that sounds, it is true.1

The monetary value of this widely unclaimed legal right can be readily calculated using official government data. The evidence is clear: union members earn significantly higher wages and have better access to additional benefits than nonunion workers.2 According to published reports from the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), median earnings for a two-income, nonunion family are $400 a week less than that of a union family. Over a lifetime, that adds up to more than a half million dollars in foregone wealth.3

Even when one accounts for characteristics that can affect earnings other than unionization, such as education, experience, occupation, hours worked, marital status, having children, state of residence, and (unfortunately) sex, race, and citizenship—the gap between union and nonunion workers remains nearly as large. Among private-sector workers who are otherwise similar, union members have per hour earnings that are 27.6 percent greater, on average, than those of nonunion workers.4

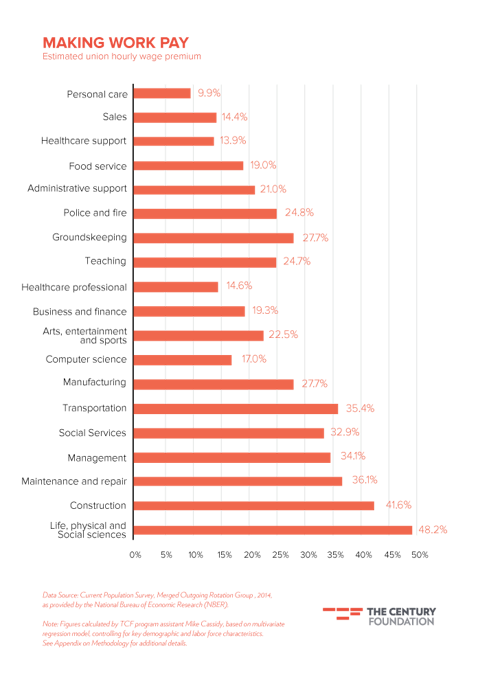

As Figure 1 shows, this union earnings premium holds across a wide range of occupations. For example, unionized construction workers earn 42 percent more hourly than their nonunion counterparts. And the premium applies both to traditional union strongholds, such as manufacturing (28 percent) and teaching (25 percent), as well as to less-unionized occupations, including food service (19 percent) and sales (14 percent).

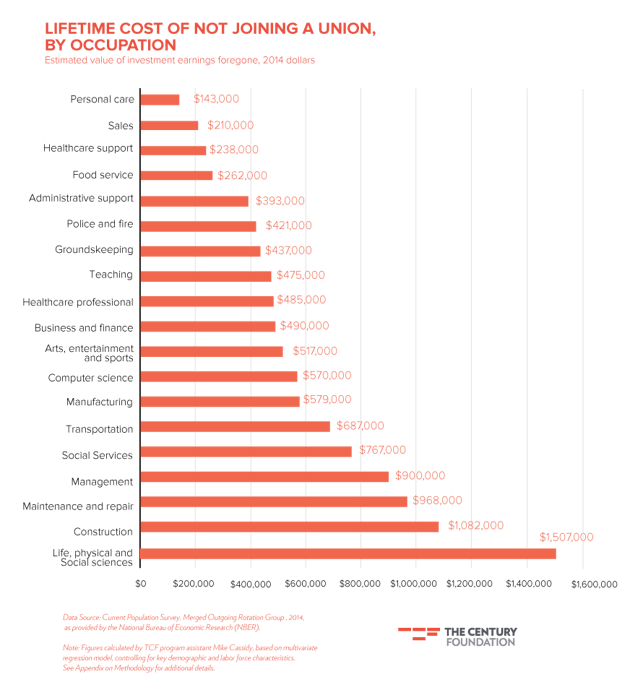

Translated into lifetime wealth differences, the cumulative effect of the union premium becomes staggering. A nonunion worker who is otherwise average could expect to accumulate an additional $551,000 in wealth by the time she retires—simply by exercising her right to join a union.5 As described in Figure 2, construction workers who do not unionize are effectively giving up $1.1 million over the course of their careers. Forfeited nest eggs are nearly as large among professions as diverse as maintenance ($968,000), management ($900,000), and social services ($767,000). Even poorly paid workers stand to reap major gains in relative terms: nonunion food service workers give up $262,000, while nonunion personal care workers forego $143,000.

Like buying a house or saving for retirement, joining a union is one of the most consequential financial decisions a worker can make.

The Idea: A New Technology to Promote Virtual Labor Organizing

Americans want more influence in the workplace to win better wages, better benefits, and more flexible work schedules—all of which can be gained through joining a union. And a 2007 study found that nearly 60 percent of workers would join a union if they could; yet, that same year, only 12 percent of workers were members of a union.6

The general procedures for joining a labor union seem simple. Organizers in a bargaining unit only need 30 percent of the employees in the unit to sign a petition requesting a union election. If 30 percent or more agree to sign on, the organizers deliver the election petition to the NLRB to request a workplace election. If a majority of employees in the bargaining unit vote in support, they become part of a union and win the right to engage in collective bargaining.

In reality, labor organizing is more challenging and complex than it has to be. It is well documented that some employees attempting to join a union are “spied on, harassed, pressured, threatened, suspended, fired, deported or otherwise victimized in reprisal for the exercise of the right to freedom of association.”7 Many employers use delaying tactics to slow down organizing drives, launch aggressive campaigns to discourage employees from signing a petition or voting to join the union, or even engage in unfair labor practices. And an organizing drive requires sharing a lot of new, perhaps unfamiliar information across a broad array of coworkers, conducting conversations that often include strong opinions and personal information, and achieving consensus on a course of action.

To win their unclaimed wealth, workers need a new tool to communicate, share information, and overcome employer resistance and intimidation.

We believe a new online tool designed to take employees through a step-by-step labor organizing process could be effective in increasing unionization.

Today, there are many examples of sophisticated online tools already in use for a wide range of complex transactions—figuring out and filing your federal income taxes, signing up for health care under the Affordable Care Act, generating legal documents, applying for college financial aid, keeping up with friends on social media, planning a vacation, balancing your financial investments, or shopping for products made almost anywhere in the world.

LegalZoom, which provides consumer and business legal services “by leveraging the power of technology and people,” is probably the only online tool that is somewhat analogous to an online labor organizing tool. The company provides a sweeping array of “interactive legal documents” to consumers, tailored “to their specific needs” through “dynamic online processes and scalable technology.” It offers consumers help with wills, trusts, divorce, immigration, DWI, bankruptcy, prenuptials,and disability claims, and business owners help with business formation, patents, trademarks, and real estate. The company has served 2 million customers over the past decade, with almost a half million legal documents. Its revenues have doubled in the past five years to almost $200 million, demonstrating a successful business model for online legal assistance. LegalZoom has built-in call centers and subscription legal plans to provide consumers additional, personalized assistance.8

Given the success of many commercial and consumer based online tools, why shouldn’t there be a new, highly sophisticated online tool that leverages state-of-the-art technology to help promote one of America’s bedrock values: getting a fair shake at work?

Unlike business formation, which is dynamic, organic, flexible, competitive, and opportunistic, union formation—organizing the workplace—is currently labor-intensive, centralized, and frequently requires outside labor union resources to start an organizing drive. Labor unions lack the resources to significantly increase the number of organizing drives on their own.

This year, there will probably be fewer than 1,500 private sector workplace elections, and only several hundred will result in a win for the union. Part of that is due to management opposition and intimidation of workers, and part because unions have not fully embraced the use of technology in organizing.

Organizing a union through the use of online tools would allow employees to band together in a more organic, grassroots effort that does not require outside help to get things started. If there were 20,000 workplace election petitions per year, instead of the 2,000 filed last year,9 the percentage of the workforce in private unions could increase into the double digits, based on past experience.10

The goal of virtual organizing would be to innovate and experiment with a new platform that is faster, homegrown, and simplified for workers to gain influence at work. Given how much today’s workers rely on information technology to do their jobs, there might be significant receptivity to this new online tool. Some 96 percent of workers use Internet, e-mail, or mobile devices to connect them to work, and some 81 percent of employees spend an hour or more on e-mail during the workday.11

Such a tool would be available to the vast majority of workers and could be of particular interest to younger workers, who are currently the driving force on social media and digital platforms.12 These younger workers also may be more eager to organize: a recent Pew Survey found that millennials disproportionally support labor unions, with 55 percent having a favorable view.13

Five Key Advantages of Online Organizing

Organizing campaigns today begin with limited resources—typically, the involvement of an outside union sending in labor organizers. Virtual organizing, however, would allow any group of workers to organically begin the process of creating a union in the workplace without having to involve any outside help. This is important, because it would allow workers to organize wholly on their own terms, and it counters the standard anti-union message used by employers that they prefer to “deal with the workers directly,” and that unions are “interlopers” or “outsiders.”

Second, such technology would allow workers an easy and efficient means to communicate effectively and safely outside the view of the employer. Conducting an organizing campaign quickly and discreetly—until a majority of workers have signed authorization cards—allows workers to have meaningful conversations about the workplace and the benefits of organizing, without employer threats or anti-union campaigns.

Third, such technology would fit into a changing view of the workplace currently embraced by the NLRB, in which e-mail and social networking activities have been granted increased protections. (See discussion below.)

Fourth, such technology would simplify an unnecessarily complicated informational and legal terrain. Sophisticated algorithms could be used to help employees determine the proper bargaining unit for an organizing drive or help labor unions determine target-rich sectors or regions for organizing.

Fifth, such technology would provide the potential for coordination and collaboration of national and regional organizing campaigns. The platform would allow best practices and emerging issues to be shared in real time and would give access to experienced organizers and labor lawyers if needed.

The Time Is Ripe for a Powerful, Online Organizing Tool

There are a number of economic, political, and legal trends that create a strategic opening for employees to engage in virtual organizing

There is a renewed openness by the nation’s labor leaders to change the organizing playbook. With the considerable support of organizations such as the Service Employees International Union (SEIU), United Food and Commercial Workers (UFCW), Restaurant Opportunities Centers (ROC) United, Brandworkers, and others, workers are showing a new activism to press for better wages. Home health care workers—many of whom work full time, yet still live below the poverty line14—rallied for higher wages in February of this year in over twenty cities. They were followed by thousands of low-wage employees and supporters who rallied in some two hundred cities this past April, targeting McDonald’s and Walmart stores as part of the Fight for $15 campaign. These rallies were made possible through a patchwork of online organizing using social media. Providing these employees with a dedicated virtual platform could capitalize on and leverage the energy of these wage protesters into a permanent, forceful voice in the workplace.

Continuing income inequality trends could also motivate significant numbers of workers to give virtual organizing a try. For example, the wages of the top 1 percent of workers grew by almost 140 percent from 1979 to 2013, while wages for the bottom 90 percent grew by only 15 percent. During that period, hourly pay for low-wage workers actually went down by 5 percent, while middle-class workers saw only a 6 percent boost in wages.15

Recent developments at the National Labor Relations Board directly help facilitate virtual labor organizing. The NLRB recently reversed years of legal precedent that allowed employers to ban the use of workplace e-mail for organizing or communicating about the terms and conditions of work. Last year, in its decision in Purple Communications, Inc., the NLRB emphatically endorsed the right of employees to use workplace e-mail for such activities. It held that “employee use of email for statutorily protected communications on nonworking time must presumptively be permitted by employers who have chosen to give employees access to their email systems.”16 The NLRB added that: “Employees’ need to share information and opinions is particularly acute in the context of an initial organizing campaign.”17

Additionally, the NLRB recently issued regulations that help prevent employers from throwing up roadblocks in the union election process. The rule, which was unsuccessfully contested by Republicans in Congress through the Congressional Review Act, modernizes and streamlines a number of NLRB procedures, with the goal of reducing unnecessary litigation and delay on the road toward organization.18

For example, it requires parties to disclose early in the process the nature of the issues in dispute so that the NLRB can rule on them expeditiously, and it repeals the current practice that automatically stays an election (thus causing unnecessary delays) if there is an appeal to the NLRB’s regional director. The rule also requires employers to turn over employee contact information, such as personal phone numbers and e-mail addresses (if available to the employer) to the union (in an electronic format), so that it has equal access to this information as part of the organizing campaign.19

Of course, some employers try to intimidate workers by demoting or firing those who engage in unionizing activities—in violation of the National Labor Relations Act. But online organizing could help address this obstacle, not only by making collective action less readily apparent to those employers who might try to break the law by unfairly disciplining employees, but also by employing technology that makes the online “footprints” of snooping employers more visible.

How Virtual Organizing Could Work

Most organizing campaigns begin in the context of dissatisfaction among workers, whether in the form of wages, scheduling, benefits, lack of voice or respect, unjust firings, or a myriad of other issues that arise in the workplace. Organizing a union in response to grievances is often seen as a complex and difficult task, but in many situations it need not be.

A new, state-of-the-art virtual platform would allow average employees in workplaces across the country to organize and join a labor union with much more ease. A well-designed platform would avoid many of the roadblocks that employers often throw down when they see efforts to organize. The platform would provide an interactive, step-by-step process so that employees know what to expect at each stage, and how to handle hurdles that may arise. It would be designed to help workers engage with other employees as well as form an organizing committee, create instructions for beginning and carrying on all facets of the organizing campaign, automatically file petitions and forms with the NLRB upon the show of sufficient support, and it would even offer model agreements on issues such as wages, benefits, scheduling policies, and health and retirement plans.

Organizing at a large or contentious business may eventually require some help from professionals, but the ideal platform would be designed to integrate this involvement with the efforts of employees on the ground, keeping “outsider” participation to a minimum. As noted above, many of today’s workers are increasingly experienced and adept at using technology to communicate, strategize, and map the workplace, which could minimize the need for additional outside assistance.

The platform could adopt technology already widely used in social networking sites, such as survey and mapping software and other tools that could be adapted to virtual labor organizing. Along the way, the platform could provide workers with descriptions of scenarios they might expect from their employers, such as captive audience meetings, “canned messages” against the union, the hiring of consultants, threats, and disciplinary action. The platform could also provide workers with advice on how to counter such measures. As envisioned, this platform (either in app or website form) would be private for each individual organizing campaign.

Significantly, launching a virtual labor organizing platform does not depend on Congress to amend the National Labor Relations Act. Web developers or investors could monetize the platform through licensing agreements with labor unions or create a fee structure for employee organizers similar to LegalZoom. Alternatively, a consortium of nonprofits could develop and disseminate such a platform for individuals and labor unions to use.

Below are some examples of the important tasks a virtual labor organizing platform could address.20

1. Mapping the Workplace

One of the first things workers seeking to organize need to do is map the workplace. Such mapping includes listing the various departments, collecting workers’ names, functions, and titles, and counting the total number of workers in the workplace. After this information is entered (or over time will already be available on the platform) with as much specificity as possible, the virtual platform would help determine the appropriate (or best) bargaining unit, while also serving as a basis for determining the organizing committee and building networks of workers.

Bargaining units are defined by a “community of interest” among the workers, but choosing which workers should be within the bargaining unit is not always as straightforward as one would imagine. Should workers in different departments, different floors, or different locations be in the same bargaining unit?

The platform would be coded for the NLRB factors used in determining a community of interest and would allow worker-organizers to input information about all the workers and their locations, job functions, and affinity for forming a union. In doing so, various options would be presented for choosing a bargaining unit, and workers could then decide which would be the most appropriate for their needs.

Further, the mapping function could help in creating and growing the organizing committee. Creating a strong, diverse, and informed organizing committee is central to any organizing campaign. The organizing committee should be representative of workers in each work area, department, job and seniority, as well as race, gender, and age. The mapping function would help organizer-workers ensure that the committee is diverse, while also assigning roles and tasks to each member of the committee (and marking when those tasks are complete). It would allow members of the committee to keep track of whom they have talked to, what concerns were raised, and which workers were supportive of forming a union, thereby encouraging networks to grow.

2. Communications and Anonymity

The virtual platform would provide a variety of functions that could help foster meaningful communication outside of physical meetings, while protecting workers who decide to speak freely. Once workers create an organizing campaign using the platform, it would be individualized for their workplace, password protected, and controlled by them. The platform would have survey capabilities to poll workers on the issues they care about most, how they want to structure their union, and how many would be interested in signing cards to join. The platform would include message boards to post and answer questions, post resources, maintain regular communications, and provide updates to everyone involved. Beyond an internal message board, available only to the workers in the campaign, the platform would have a feature wherein workers could ask anonymous questions of outside professional union organizers and labor lawyers in order to seek advice specific to the campaign. Currently, workers who want to engage in virtual discussions and organizing are forced to do so through things such as closed Facebook groups, free survey programs, and other standalone, unsecure methods that were not created for the purposes of organizing a workplace. These methods risk exposure and manipulation, and they lack the ability to serve more than their discrete functions.

Perhaps most importantly, any discussions and information in this virtual organizing platform would remain private and anonymous from the employer. Lead organizer-workers would be granted administrative rights to the platform that would allow them to manage the members and content of the virtual campaign, while all other participants could post anonymously. Any individual who wishes to join would need to provide accurate credentials (such as a name, job title, e-mail, and phone number) to assure that they are workers at the specific workplace. IP addresses of all who try to access the site would be captured. Moreover, entrants would have to agree to terms of service that would inform them that if they are management or affiliated with the employer, trying to access this site would constitute employee surveillance of union activity, which is a violation on §8(a)(1) of the NLRA.

3. Winning Election or Building Employee Unity

The virtual platform would help employees move quickly through an organizing drive and submit authorization cards for an election or voluntary recognition upon a showing of a majority. The platform would facilitate filing the election petition electronically (as allowed under the new NLRB election rules) and would be able to integrate all the voter list information (employee names, addresses, phone numbers, and e-mail addresses) that the employer must turn over electronically two days after the election agreement is approved.

Conclusion

In an era of persistent income inequality, virtual organizing may provide an opportunity to lift the lifetime earnings of hardworking Americans.

The creation of this platform, in and of itself, could give employees surprising new leverage at work, once the company understands that dissatisfied employees have an easier, less-obstructed way to join a union.21

If virtual organizing took hold, it also could transform the way in which the nation’s top labor unions deploy their organizing capabilities. Rather than just engaging in resource-intensive retail organizing, they could become wholesalers of union formation, investing in large-scale promotion of an online resource, backed by call-centers and a significant network architecture standing behind this powerful new tool.

The American worker certainly needs help to reclaim the benefits of the legal right to organize. Wages and salaries—once over 50 percent of GDP have now slid to 42.6 percent, the lowest since 1929.22This disastrous decline in prosperity needs to be disrupted. Recent economic, political, and legal trends—as well as the surging use of technology—may provide workers a way forward through virtual labor organizing.

Notes

-

- 1. Section 7 of the National Labor Relations Act grants employees the “right to . . . engage in . . . concerted activities for the purpose of collective bargaining or other mutual aid or protection.” The act not only gives employees such right, but Congress specifically declared that it is the “policy of the United States to . . . encourage the practice and procedure of collective bargaining” and to “protect the exercise by workers of full freedom of association, self-organization, and designation of representatives of their own choosing, for the purpose of negotiating the terms and conditions of employment.”

2. “Recent data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) show that on average, union workers receive larger wage increases than those of nonunion workers and generally earn higher wages and have greater access to most of the common employer-sponsored benefits as well.” (“Differences between union and nonunion compensation, 2001–2011,” Monthly Labor Review, April, 2013, http://www.bls.gov/opub/mlr/2013/04/art2full.pdf.) For example, a union service worker earns an average of $16.17 per hour, compared to an average $10.16 per hour for a nonunion service worker, or a $6.01 difference per hour. Median weekly earning for union wages for 2014 were $950 per week, versus $750 for nonunion workers. (Bureau of Labor Statistics, Economic News Release, Table 2: Median weekly earnings of full-time wage and salary workers by union affiliation and selected characteristics, http://www.bls.gov/news.release/union2.t02.htm.)

3. See the Appendix on Methodology for the calculation of this figure. This figure does not reflect the total potential value to American workers, because when some firms unionize, the wage benefits spill over to nonunionized workers as nonunion businesses raise wages to compete for talented workers.

4. These calculations are based on a multivariate regression model that controls for key demographic and labor force characteristics. See the Appendix on Methodology for a detailed discussion.

5. Assumes thirty-five years of full-time work (forty hours/week, fifty-two weeks/year), with all surplus union earnings invested at a real interest rate of 3 percent.See the Appendix on Methodology for a detailed discussion.

6. Peter Hart Research Associates Poll, December 2006, cited in Gordon Lafer, Neither Free Nor Fair: The Subversion of Democracy Under National Labor Relations Board Elections (Washington, D.C.: American Rights at Work, 2007), and David Madland and Karla Walter, “Unions Are Good for the American Economy,” Center for American Progress, February 18, 2009, https://www.americanprogressaction.org/issues/labor/news/2009/02/18/5597/unions-are-good-for-the-american-economy-2/.

7. Unfair Advantage: Workers’ Freedom of Association in the United States under International Human Rights Standards (New York: Human Rights Watch, 2000), 9.

8. “Registration Statement: LegalZoom.com, Inc.,” Securities and Exchange Commission, May 10, 2012, http://www.sec.gov/Archives/edgar/data/1286139/000104746912005763/a2209299zs-1.htm.

9. “Representation Petitions—RC,” National Labor Relations Board, http://www.nlrb.gov/news-outreach/graphs-data/petitions-and-elections/representation-petitions-rc.

10. For example, in 1980, there were 12,701 petitions filed with the NLRB. (Forty-Fifth Annual Report of the National Labor Relations Board for the Fiscal Year Ended September 30, 1980 [Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1980], http://www.nlrb.gov/sites/default/files/attachments/basic-page/node-1677/nlrb1980.pdf.) That same year, over 20 percent of private-sector employees were unionized. See also “50 Years Of Shrinking Union Membership, In One Map,” Planet Money, NPR, February 23, 2015, http://www.npr.org/sections/money/2015/02/23/385843576/50-years-of-shrinking-union-membership-in-one-map.

11. Purple Communications Inc., 361 NLRB No. 126 (2014), 5.

12. “Mixed Views of Impact of Long-Term Decline in Union Membership,” Pew Research Center, April 27, 2015, http://www.people-press.org/2015/04/27/mixed-views-of-impact-of-long-term-decline-in-union-membership/.

13. Ibid.

14. Paying the Price: How Poverty Wages Undermine Home Care in America (Washington, D.C.: PHI, February 2015), http://phinational.org/sites/phinational.org/files/research-report/paying-the-price.pdf.

15. Lawrence Mishel, Elise Gould, and Josh Bivens, “Wage Stagnation in Nine Charts,” Economic Policy Institute, January 6, 2015, http://s1.epi.org/files/2013/wage-stagnation-in-nine-charts.pdf.

16. Purple Communications Inc., 6.

17. Ibid.

18. The validity of the new NLRB rule was recently upheld. See Associated Builders & Contractors of Texas Inc. et al v. National Labor Relations Board, No. 1:15-cv-00026 (W.D. Tex. June 01, 2015), http://ia902703.us.archive.org/28/items/gov.uscourts.txwd.731649/gov.uscourts.txwd.731649.36.0.pdf.

19. “NLRB Issues Final Rule to Modernize Representation-Case Procedures,” National Labor Relations Board, December 12, 2014, http://www.nlrb.gov/news-outreach/news-story/nlrb-issues-final-rule-modernize-representation-case-procedures.

20. Many of these issues are derived from interviews the authors had with union organizers.

21. In its focus on empowering individual employees to pursue collective goals, this online organizing proposal dovetails with an earlier Century Foundation proposal—to amend the Civil Rights Act of 1964 in order to give individual employees the right to sue in federal court if their rights to unionize are violated. See Richard D. Kahlenberg and Moshe Z. Marvit, Why Labor Organizing Should Be a Civil Right: Rebuilding a Middle-Class Democracy by Enhancing Worker Voice (New York: The Century Foundation Press, 2012).

22. “Compensation of Employees: Wages and Salary Accruals/Gross Domestic Product,” The Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, https://research.stlouisfed.org/fred2/graph/?g=2Xa.