Since late April, Syria has suffered surging violence and mass displacement, as the Russian-backed forces of Syrian President Bashar al-Assad attack jihadis and other Turkish-backed rebels in the northwestern Idlib region.1 According to United Nations (UN) and humanitarian data, the area is home to somewhere between 2.5 and 3 million people, and at least 270,000 civilians have fled their homes since the offensive began.2

UN officials, rights groups, and aid workers say they have documented more than two dozen air strikes on clinics and hospitals in insurgent-controlled territory, despite the strong protections enjoyed by medical facilities under international humanitarian law.

Many of the hospitals in insurgent-controlled territories have voluntarily shared their GPS coordinates with Russia, Assad’s ally, under a UN-run system referred to as “humanitarian deconfliction.” It doesn’t seem to be helping. Some officials and activists now wonder if the “no-strike list” is being used to locate and destroy hospitals—the very opposite of what the UN intended.

A Pattern of Attacks on Medical Facilities

No party to the Syrian war is innocent of war crimes, but when it comes to attacking hospitals, the Syrian Arab Air Force is in a league of its own. To be sure, indiscriminate rebel shelling will sometimes hit hospitals and clinics in government-controlled territory, but the insurgents cannot reach behind the frontline in depth and at scale the way Assad’s air force can.

Physicians for Human Rights, an NGO, says it has corroborated reports of 566 separate attacks on a total of 348 medical facilities in Syria from March 2011 through May 2019. Nearly 900 medical workers are reported to have lost their lives in these attacks. A total of 509 of the incidents registered, or 90 percent, were traced to the Syrian government or its allies.3

The pattern did not change when the Russian Air Force entered Syria’s civil war on the loyalist side on September 30, 2015.4 To the contrary, the Independent International Commission of Inquiry on the Syrian Arab Republic, a UN-mandated investigative panel that collects evidence on war crimes and human rights abuse in Syria, says attacks on health care facilities “markedly increased in frequency as of October 2015.”5

According to Amnesty International, Syrian and Russian government forces have “deliberately and systematically” targeted medical personnel as part of a military strategy to wreak havoc in insurgent-held areas and trigger civilian displacement.6 Both governments deny the charge, because what it amounts to is a serious violation of international humanitarian law—in other words, a war crime.

Hospitals and the Laws of War

The global standard for humanitarian conduct in war is defined by the four Geneva Conventions of 1949, which have been signed by every nation on Earth. Among other things, they seek to ensure that civilians can access health care in times of war, that doctors and nurses can work freely and safely, and that soldiers on all sides will be properly cared for when injured.7 The conventions therefore include strong, specific protections for hospitals, clinics, and ambulances, as well as for people involved with the provision of medical assistance. Not only is it illegal to attack health care providers: all parties to a conflict must also respect and refrain from complicating their activities, even when they treat wounded enemies.

Not only is it illegal to attack health care providers: all parties to a conflict must also respect and refrain from complicating their activities, even when they treat wounded enemies.

Who runs or funds a hospital makes no difference in that regard. The protection accorded to medical facilities under international humanitarian law applies not only to private civilian health care providers, but also to government-run medical institutions and even military hospitals.8

Of course, there are exceptions to every rule. Hospitals or ambulances can be misused for military purposes, either by the party operating them or by armed actors who try to exploit their presence. If that occurs, it can invalidate the special protection they enjoy. According to Article 19 of the Fourth Geneva Convention:

The protection to which civilian hospitals are entitled shall not cease unless they are used to commit, outside their humanitarian duties, acts harmful to the enemy. Protection may, however, cease only after due warning has been given, naming, in all appropriate cases, a reasonable time limit, and after such warning has remained unheeded.9

Ignatius Ivlev-Yorke, a spokesperson for the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), the Geneva-based organization that shepherded the writing of the Geneva Conventions and monitors compliance with their terms, says such harmful acts could include situations where a medical facility or transport is used

…to fire at an enemy beyond self-defense; to shelter healthy combatants; to store arms or ammunition; as military observation posts; as a shield for military action; to transport healthy troops, arms, or munitions; or to collect or transmit military information that facilitates military operations.10

However, the mere sighting of weapons or soldiers in a hospital does not mean that it can be attacked. In some cases, weapons on hospital grounds can in fact be permitted. For example, staff at a military hospital can reasonably be expected to carry light weapons for self defense or for the defense of patients, without that constituting an act “harmful to the enemy.” Similarly, hospitals and ambulances may surround themselves with armed escorts and guards if they operate in insecure areas. Rifles and other small arms that have been taken from wounded combatants can also temporarily be stored on hospital grounds. None of those activities would strip a hospital of its protected status. “Finally, loss of protection can never occur if you provide medical care to a wounded enemy—that is never, in and of itself, a hostile act,” says Ivlev-Yorke.11

Whether or not a hospital can be easily identified as a hospital is irrelevant, as long as the attacking party has reason to suspect that it might be one. Under the Geneva Conventions, medical workers and facilities can use the red cross and crescent symbols to identify themselves, on the understanding that this will protect them. In Syria, however, not all hospitals do. “Over the past two years, numerous hospitals and medical facilities [in non-government regions] have been operating from reinforced basements or caves dug into the mountains, with the aim of reinforcing them from exposure to attack,” wrote the Commission of Inquiry in 2018. “Out of fear of attack, health-care administrators have ceased using a distinctive emblem as is generally required by international humanitarian law.”12

While this makes identification more difficult and accidental hits more likely, using the red crescent or cross emblems is not a legal prerequisite for legal protection. “The emblems just make such protection visible,” says Ivlev-Yorke.13

Even when there is clear evidence that a medical facility violates its humanitarian status, there is no automatic loss of protection under the Geneva Conventions. “Prior to the loss of protection being effective, you must issue an obligatory warning and if possible this must be accompanied with a specific time limit,” explains Ivlev-Yorke. “Only if this warning is not heeded, the protection is lost.”14

Exceptions to that rule are stringently interpreted as situations of urgent self-defense, such as being ambushed by enemies who fire from inside a hospital.15 It hardly seems applicable to the reports of Syrian hospitals being bombed from the air. In fact, there is no evidence that Geneva Conventions-mandated warnings were ever issued in Syria, which has led the Commission of Inquiry to conclude that the government’s air strikes on hospitals must be considered war crimes, in so far as the targeting is intentional.16

The Syrian government dismisses the criticism, and has never acknowledged bombing a hospital, either by accident or otherwise.17

Humanitarian Deconfliction

Although the Security Council strongly condemns attacks on health care facilities, the UN can do little, given the disagreements among the five permanent members over Syria.18 UN agencies have nonetheless tried to facilitate the upholding of international humanitarian law by urging Syrian health care providers to join a UN-run process known as “humanitarian deconfliction.”19

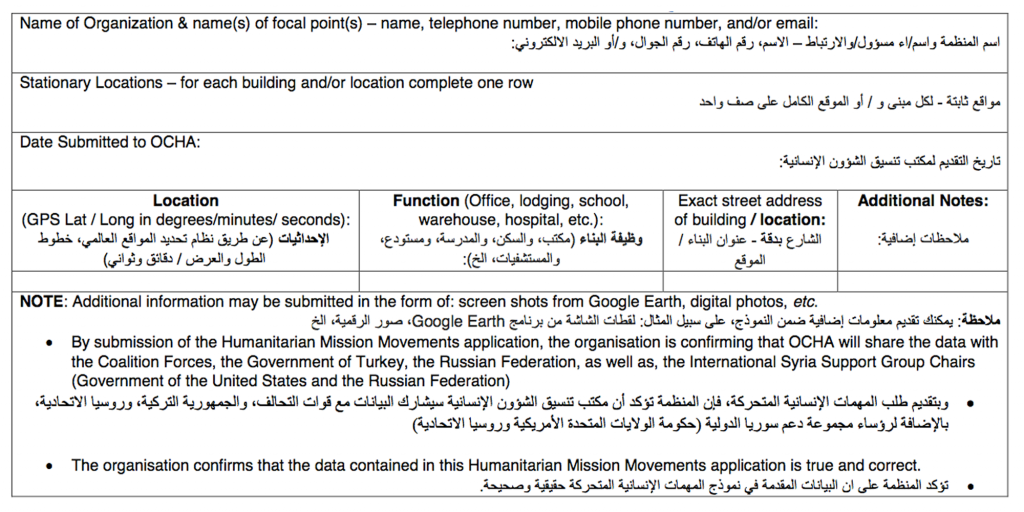

OCHA, the UN’s emergency aid coordination body, defines deconfliction as the “exchange of information and planning advisories by humanitarian actors with military actors” in order to “remove obstacles to humanitarian action, and avoid potential hazards for humanitarian personnel.”20 Practically speaking, deconfliction has come to mean that the UN helps humanitarian actors on the ground relay information about their presence and their legally protected status to military actors operating in the area, including by registering them on what is informally known as a “no-strike list.”

Participation in the system is voluntary. It doesn’t make international humanitarian law any easier to enforce, but it does make the law easier to comply with for those who genuinely wish to do so. It also makes it easier to identify those who do not, since being informed about the locations of hospitals makes it difficult for an attacker to feign innocence or blame misidentification of targets.

A 2011 OCHA report noted that UN-facilitated deconfliction efforts have had some success in the past, including in the Israeli–Arab conflicts.21 Since 2015, OCHA also operates a deconfliction mechanism in Yemen,22 where a Saudi-led coalition stands accused of bombing civilian targets, including hospitals.23 Although civilians continue to be killed, UN officials have said the deconfliction system is indispensable for their relief operations. “The UN provides the [Saudi-led] Coalition with coordinates of key aid facilities, and we let them know when humanitarian convoys, immunisation teams and other assistance missions will be on the road,” the head of OCHA, Mark Lowcock, explained in October 2018. “This system has proven largely effective in sparing the aid operation from accidental or incidental harm. Without it, we would simply not be able to deliver assistance safely.”24

OCHA’s Syrian deconfliction mechanism predates the Yemeni operation by half a year, but is much smaller and has been less effective. The first deconfliction exchanges began in September 2014, when a U.S.-led coalition intervened against the so-called Islamic State in northern and eastern Syria. When Russia and Turkey launched their own military interventions in Syria in 2015 and 2016, respectively, they, too, were included in the deconfliction process.25 OCHA continues to feed information to all three nations, who are expected to share it with their allies and restrain them from attacking objects on the no-strike list. In Russia’s case, that means the Syrian government.

Like in Yemen, OCHA has positioned itself as a communication middleman, helping humanitarian actors in Syria advertise their presence and nonthreatening nature through standardized forms according to certain rules. For example, humanitarian convoys must be announced at least seventy-two hours ahead of time and should be registered with descriptions of their routes, time plans, purpose, and, ideally, the number and type of vehicles. Fixed sites can also be reported to the no-strike list, including “offices, warehouses, lodgings, hospitals, clinics, distribution sites, and other sites that serve a humanitarian purpose.” In addition to GPS coordinates and general descriptions, OCHA suggests that they could upload Google Earth screenshots to facilitate aerial recognition.26

OCHA has no ability to double-check or rectify the information offered by humanitarian actors, so the system is potentially vulnerable to error and abuse. But, at the very least, it provides military leaders on all sides of the conflict with a list of sites where attacks cannot lawfully happen without cross-checking with the deconfliction record and, if cause for legitimate use of force is found, to warn before proceeding to take action.

The system has had limited success in Syria. According to a report by The New Humanitarian’s Ben Parker, 778 sites in Syria had been added to the UN’s no-strike lists by late 2018, compared to 64,000 in Yemen. Of approximately 120 attacks on health care facilities in Syria in that year, a “handful” were reported to have struck deconflicted sites.27

In April 2018, twelve NGOs operating a total of sixty clinics in insurgent-controlled northwestern Syria joined the system. The organizations made it clear that they do not trust the Syrian and Russian governments to honor the Geneva Conventions, but nonetheless opted to join the system after “lengthy consultations with, and full endorsement by, our teams inside Syria and doctors working in these hospitals,” according to the Syrian American Medical Society (SAMS), a U.S.-based NGO that offers medical assistance in areas outside Assad’s control and to Syrian refugees. “UN OCHA assured us that they will now monitor and report on alleged attacks,” a SAMS statement said. “Although we know that such attacks are likely to continue, we hope that this move will act as a deterrent and bring increased transparency to the reporting process.”28

It was a gamble, of course. Would transparency protect clinics in Idlib, when camouflage and blast walls could not?

The Idlib Offensive

In April 2019, the Russian–Turkish truce arrangements that had curtailed major fighting in northwestern Syria collapsed.29 Once again, Russian-backed Syrian government troops pushed through insurgent lines, seizing villages and towns like Qalaat al-Madiq and pounding the Idlib region with air strikes. Inside the rebel enclave, the salafi-jihadi group Tahrir al-Sham, which dominates the province, scrambled to stop the attack and was joined by Turkey-backed Islamist groups, firing rockets and mortars back into government-held regions.30

Government forces have not penetrated deep into the Idlib pocket, but the fighting has nonetheless triggered mass flight. By late May, the UN had counted 160 killed civilians and 270,000 displaced.31

“In Hama, families have been seeking temporary refuge while others are on the move in Idlib governorate, reportedly moving towards camps close to the Turkish border and also western and northern rural areas of Aleppo Governorate,” said Mari Mørtvedt, a Damascus-based ICRC spokesperson. “The population movements are continuous and difficult to track.”32

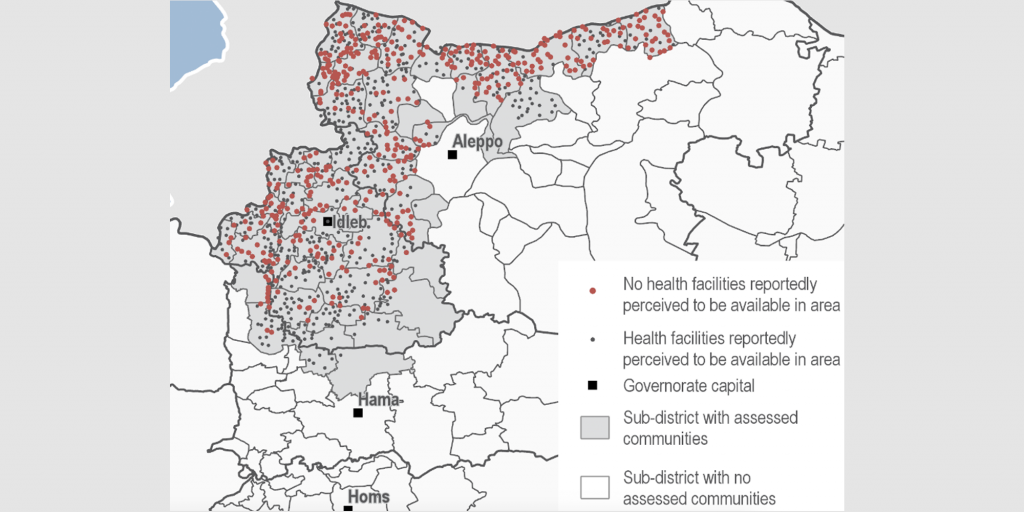

Air strikes seem to be a major factor behind the displacement. A handful of attacks on relief stockpiles, schools, or clinics can be enough to paralyze service provision and instill fear in a community that has learned to expect the worst. With up to half of Idlib’s population already made homeless at least once, many families live hand-to-mouth and will quickly move on if their area becomes insecure or humanitarian aid and services dry up. Most towns in the region are already packed with displaced people, and the humanitarian infrastructure is at risk of being overwhelmed. Less than three weeks into the current fighting, tens of thousands of Syrian families were sleeping not in tent camps or prepared hosting sites, but under trees and in fields under the open sky.33

On June 12, the Russian military announced that Russian and Turkish negotiations had resulted in a ceasefire agreement that would bring the offensive to a close.34 Several Turkey-backed rebel groups rejected the idea, and both sides accused each other of violating the truce.35 At least some fighting continued as this report was being finalized on June 13, and Turkish Foreign Minister Mevlüt Çavuşoğlu said it was “not possible to say a complete ceasefire has been secured.”36

Once Again, Hospitals Come under Attack

Opposition sources, aid workers, and UN officials say the April-May fighting saw renewed attacks on hospitals, reportedly including UN-deconflicted sites.

For example, UN Assistant Secretary-General for Humanitarian Affairs Ursula Müller reported on May 28 that the UN had recorded twenty-five separate attacks on a total of twenty-two medical facilities in the first month of fighting.37 Mohamad Katoub, a Turkey-based official with SAMS, gave the same numbers and offered a detailed list of locations and dates.38 The Syrian Network for Human Rights, an opposition-linked monitoring group, offered a slightly higher figure: twenty-nine separate attacks on a total of twenty-four health care facilities.39

Information is nonetheless difficult for outsiders to verify, and the situation on the ground is murky. Marta Hurtado, a spokesperson for the UN high commissioner for human rights, warned that both pro- and anti-Assad groups have failed to uphold international humanitarian law, including by placing military objects in “close proximity to civilians and civilian objects, resulting in civilian deaths and injuries, and causing significant damage to civilian infrastructure such as hospitals, mosques, schools, and markets.”40

However, while the presence of anti-Assad fighters in or near hospitals could offer a military rationale for some of the air strikes, the strict terms of the Geneva Conventions still apply. If Russian or Syrian pilots were to discover, for example, that a hospital building is being used for hostile purposes by rebels, they must still warn medical staff and give them enough time to either get the rebels out or to evacuate patients and staff; only after that time limit has passed can an attack be launched without violating international humanitarian law. To date, neither Moscow nor Damascus has offered any evidence that fighters are abusing the protected status of medical sites. Nor have they offered evidence of trying to give fair warning before attacks on medical facilities. Instead, they simply deny that medical sites are being hit at all.

To date, neither Moscow nor Damascus has offered any evidence that fighters are abusing the protected status of medical sites. Nor have they offered evidence of trying to give fair warning before attacks on medical facilities. Instead, they simply deny that medical sites are being hit at all.

That doesn’t square well with the available evidence, even if opposition and activist claims were to be disregarded entirely. UN officials also clearly state that hospitals are being bombed.

For example, the UN’s World Health Organization (WHO) strongly condemned attacks on hospitals as early as the first days of the offensive.41 Since then, WHO has reported that nearly fifty clinics have been forced to close because of the insecurity, many of them after being bombed. “As a result of the conflict, there are no functioning hospitals in northern Hama,” WHO said, warning that already by May 15 the health sector in that region had “almost collapsed” and that even vaccination centers were shutting down, creating risks of epidemics.42

“Between them [the closed or destroyed clinics] provided an average each month of at least 171,000 medical outpatient consultations and 2,760 major surgical operations,” said Mark Lowcock, the OCHA chief. “They helped more than 1,400 women deliver their babies every month. Now they are not doing those things.”43

Striking the No-Strike List

Several sources report attacks on OCHA-deconflicted clinics whose GPS coordinates were shared with the Russian military.

Mohamad Katoub, the SAMS official, said he was aware of ten different attacks on nine deconflicted clinics, starting in early May. According to Katoub, aerial bombardment was responsible for nine of the ten attacks. The tenth, which hit a mental health clinic in Dana on May 28, was a bombing with an improvised explosive device and not from the air, a phenomenon that Katoub said has become more common since 2018. As it appears that no one has claimed responsibility for the May 28 attack, the perpetrator remains unknown. “Syrian government forces are not the only criminals here,” Katoub said, but he added, “Well, we are sure about the air strikes at least.”44

The Geneva-based Union of Medical Care and Relief Organizations (UOSSM), a coalition of humanitarian NGOs working in opposition-controlled Syria, has also said hospitals on the no-strike lists are being attacked. Apart from the bombing of a SAMS-backed facility in Kafr Zita on May 5, UOSSM reported air strikes against deconflicted clinics in Hass and Kafranbel on the same day.45

The Syrian Network for Human Rights said six of the twenty-four clinics attacked between April 26 and May 24 had reported their GPS coordinates to OCHA’s no-strike list. “In practice, these facilities did not benefit” from deconfliction, the group said, adding that, “in fact, rather than protecting them, the mechanism may have exposed them to further danger by revealing their location and place of work.”46

A May 24 statement by more than forty Syrian and international NGOs also referred to deconflicted sites being bombed, with the International Human Rights Federation (FIDH), the International Rescue Committee, PAX, and Mercy Corps among the signatories.47

Lynn Maalouf, the Middle East research director of Amnesty International, said her organization, too, had interviewed medical workers from bombed hospitals who had shared their coordinates through the UN system. “So no, if the aim is to protect civilians and civilian facilities, then it’s not working,” she said.48

By late May, OCHA was investigating the claims that deconflicted clinics had been attacked. OCHA spokesperson Hedinn Halldorsson told the Daily Telegraph it was “too early” to definitively say whether deconflicted clinics had been hit, but that preliminary reports indicated that “some of the locations [that were bombed] may have been deconflicted with relevant parties.”49

Other UN officials have made stronger statements, saying outright that deconflicted targets are being attacked.

For example, UN Under-Secretary-General for Political Affairs Rosemary DiCarlo told the UN Security Council on May 17 that “several” bombed sites had been registered on the UN’s no-strike list.50

In his own briefing to the Security Council, OCHA’s Mark Lowcock also brought up attacks on deconflicted targets. He pointedly noted that many sites on the no-strike list that “are not hospitals have not been attacked,” suggesting that health-related targets are deliberately selected for destruction. While avoiding direct accusations against the Syrian and Russian governments, he dropped hints, phrased as rhetorical questions, that OCHA’s no-strike list is being used to find and destroy medical clinics. “If I were an NGO running a hospital why would I want to give you details of my location if that information is simply being used to target the hospital?” Lowcock asked.51

A Clash in the Security Council

Western diplomats in the Security Council seized on the reports from DiCarlo and Lowcock to criticize the behavior of the Russian and Syrian governments. They pointed to attacks on deconflicted facilities as an especially incriminating piece of evidence.

“We are particularly alarmed and shocked by reports of attacks on civilian infrastructure, such as medical facilities whose location has been notified under the de-confliction mechanism,” said Belgian UN Ambassador Marc Pecsteen de Buytswerve in a statement that also represented Kuwait and Germany.52 François Delattre of France called the attacks on hospitals “war crimes,” and his U.S. counterpart, Jonathan Cohen, said it was “most alarming” that “several of these facilities were on deconfliction lists set up by the Russian Federation and [OCHA].”53

“Are the hospitals and other facilities being deliberately targeted despite the deconfliction mechanisms?” asked the United Kingdom’s UN ambassador Karen Pierce. “It would be absolutely grotesque if non-governmental organizations and health workers providing coordinates to a mechanism which they believe is there to ensure their safety were finding themselves being the authors of their own destruction because of deliberate targeting by the regime,” she said. She stressed that “Russia and Syria are the only countries that fly airplanes in the area” where the air strikes are taking place.54

The Syrian and Russian representatives present at the meeting brushed off the criticism, rejecting the reports from DiCarlo and Lowcock about bombed hospitals and accusing Western diplomats of engaging in disinformation.

“[T]here have been no random attacks on Syrian civilians in Idlib,” said Syria’s UN ambassador Bashar al-Jaafari. “There are military operations being conducted by the Syrian army and its allies against a terrorist entity listed by the Security Council, aimed at liberating the civilian population of Idlib.” He insisted that civilians in the area are “being used as human shields by Al-Qaida in Syria.” Jaafari did not respond to questions about the UN deconfliction process, but said some hospitals in Syria had been taken over by terrorists; he then accused the U.S. Air Force of attacking hospitals during its campaign against the Islamic State.55

“We categorically reject the accusations of violations of international humanitarian law,” said Russia’s UN ambassador Vasily Nebenzia:

Neither the Syrian army nor the Russian aerospace forces is conducting hostilities against civilians or civilian infrastructure. Our target is the terrorists, which some of my colleagues prefer not to mention. We once again call on the Secretariat and the specialized United Nations agencies, including the World Health Organization, not to hasten to publicly spread unverified information about civilian casualties or damage to civilian infrastructure. The information should come from reliable, non-politicized sources and must be thoroughly checked, including by ascertaining whether infrastructure that has supposedly been hit has been through a deconfliction process.56

Days later, Moscow declared that the U.S. government had orchestrated the reports of hospitals being bombed in Idlib. “We think that the misinformation campaign that we see now was launched by the official US authorities,” the Russian Foreign Ministry said in a statement carried by state media, which accused the United States of trying to “stonewall the process of clamping down on international terrorists.”57

“A Crime Against Humanity”

Although the UN’s deconfliction mechanism does not seem to be stopping attacks on medical facilities, it is working as intended in one respect: it is difficult for Moscow and Damascus to claim that a deconflicted hospital whose coordinates have been provided directly to the Russian military is being bombed by accident. Human rights groups are already picking up on the issue, describing it as ipso facto evidence of war crimes.

On May 17, Amnesty International accused the Syrian military and its Russian patron of “carrying out a deliberate and systematic assault on hospitals and other medical facilities in Idlib and Hama.”58

“In all of their military operations—Ghouta, Aleppo, Douma—the government of Syria has destroyed civilian facilities deliberately to pressure the civilian population and the armed groups into surrendering,” Maalouf said, noting that, in Amnesty’s view, the “attacks against hospitals are widespread and systematic, and this is what brings us to say the attacks against hospitals in Syria are a crime against humanity.”59

But will these condemnations make any difference? Now enduring their eighth year of withering criticism from international rights groups and, of course, from their Western adversaries, one thing is clear: the rulers of Syria and Russia are not easily embarrassed.

Even if OCHA’s internal investigations were to confirm the reports of deliberate targeting of deconflicted hospitals, it is far from certain that the UN system could muster clear, public acknowledgment, never mind direct criticism. Were that to happen, the Russian and Syrian government response would likely be a familiar one: scornful, unyielding denial, instead of an effort to bring military targeting in line with the Geneva Conventions that they, themselves, have signed.

Whether or not the UN’s deconfliction system is endangering medical workers or simply failing to protect them remains an issue to be investigated. But there could be no clearer illustration of the damage done by Syria’s eight-year war to an already brittle system of global norms, laws, and institutions.

Cover Photo: Surgery at an NGO-supported hospital in the Idlib region. Source: Syrian American Medical Society

Notes

- Aron Lund, “As Turkey and Russia pull the strings in Syria’s Idlib, civilians pay the price,” The New Humanitarian, May 21, 2019, http://www.thenewhumanitarian.org/analysis/2019/05/21/turkey-and-russia-pull-strings-syria-idlib-civilians

- Population figures in Syria are very uncertain and have often skewed high, likely due to over-reporting by local sources hoping to secure foreign assistance. The Humanitarian Access Team of Mercy Corps, which kindly made its database available to the author, estimated the wider Idlib region’s population at approximately 2.49 million people in late 2018. That figure included civilians displaced from other parts of Syria, but it excluded an additional estimated 842,000 people in Turkish-controlled areas further north (Efrin-Azaz-Bab). However, different sources give different figures and use different definitions. For example, UN aid chief Mark Lowcock said on May 17 that the UN estimates that there are a total of three million people in the Idlib de-escalation area. Transcript of Mark Lowcock’s briefing to the UN Security Council on May 17, 2019, available via ReliefWeb at https://reliefweb.int/report/syrian-arab-republic/under-secretary-general-humanitarian-affairs-and-emergency-relief-90. For the most recent UN displacement estimates: “Assistant Secretary-General for Humanitarian Affairs and Deputy Emergency Relief Coordinator, Ursula Mueller – Briefing to the Security Council on the humanitarian situation in Syria, New York, 28 May 2019,” ReliefWeb, May 28, 2019, https://reliefweb.int/report/syrian-arab-republic/assistant-secretary-general-humanitarian-affairs-and-deputy-emergency-5

- “Physicians for Human Rights’ Findings of Attacks on Health Care in Syria,” Physicians for Human Rights, syriamap.phr.org/#/en/findings. Site visited on May 19, 2019.

- On the Russian role in Syria, see Aron Lund, “From Cold War to Civil War: 75 Years of Russian-Syrian Relations,” UI Paper 7/2019, Swedish Institute of International Affairs, May 2019, ui.se/butiken/uis-publikationer/ui-paper/2019/from-cold-war-to-civil-war-75-years-of-russian-syrian-relations.

- United Nations, “Report of the Independent International Commission of Inquiry on the Syrian Arab Republic,” A/HRC/37/72, February 1, 2018, undocs.org/A/HRC/37/72.

- Amnesty International, “Syrian and Russian forces targeting hospitals as a strategy of war,” March 3, 2016, amnesty.org/en/latest/news/2016/03/syrian-and-russian-forces-targeting-hospitals-as-a-strategy-of-war.

- The Geneva Conventions and the associated commentaries can be accessed via the International Committee of the Red Cross website: ihl-databases.icrc.org/ihl.

- Email from Ignatius Ivlev-Yorke, public relations associate with the International Committee of the Red Cross, May 2019.

- Article 19 of the Fourth Geneva Convention of August 12, 1949.

- Email from Ignatius Ivlev-Yorke, public relations associate with the International Committee of the Red Cross, May 2019.

- Email from Ignatius Ivlev-Yorke, public relations associate with the International Committee of the Red Cross, May 2019. Article 19 of the Fourth Geneva Convention is very explicit: “The fact that sick or wounded members of the armed forces are nursed in these hospitals, or the presence of small arms and ammunition taken from such combatants and not yet handed to the proper service, shall not be considered to be acts harmful to the enemy.”

- United Nations, “Report of the Independent International Commission of Inquiry on the Syrian Arab Republic,” February 1, 2018, A/HRC/37/72, undocs.org/A/HRC/37/72.

- Email from Ignatius Ivlev-Yorke, public relations associate with the International Committee of the Red Cross, May 2019.

- Email from Ignatius Ivlev-Yorke, public relations associate with the International Committee of the Red Cross, May 2019.

- “Suppose, for example, that a body of troops approaching a hospital were met by heavy fire from every window. Fire would be returned without delay,” notes the 1952 Commentary on Article 21 of the First Geneva Convention. See: ihl-databases.icrc.org/ihl/COM/365-570026?OpenDocument.

- “The lack of warnings and the absence of military objectives within and near hospitals demonstrate that pro-Government forces deliberately target medical infrastructure as part of their war strategy, which constitutes the war crime of intentionally targeting protected objects. Furthermore, deliberate attacks against medical staff and ambulances constitute the war crimes of intentionally attacking medical personnel and medical transport.” United Nations, “Report of the Independent International Commission of Inquiry on the Syrian Arab Republic,” A/HRC/37/72, February 1, 2018, undocs.org/A/HRC/37/72.

- No Syrian government official could be reached for comment for this report. At a press conference attended by the author at the Syrian Foreign Ministry in Damascus in October 2016, Foreign Minister Walid al-Moallem said Syrian forces had not struck hospitals, accusing Western nations and opposition groups of engaging in propaganda to tarnish the government’s image.

- In 2016, the Security Council adopted a resolution specifically condemning attacks on hospitals and medical staff, inspired largely by the wars in Syria and Yemen. United Nations, “Security Council Adopts Resolution 2286 (2016), Strongly Condemning Attacks against Medical Facilities, Personnel in Conflict Situations,” SC/12347, May 3, 2016, un.org/press/en/2016/sc12347.doc.

- Ben Parker, “What is humanitarian deconfliction?,” The New Humanitarian, November 13, 2018, thenewhumanitarian.org/analysis/2018/11/13/what-humanitarian-deconfliction-syria-yemen.

- Jan Egeland, Adele Harmer, and Abby Stoddard, “To Stay and deliver: Good practice for humanitarians in complex security environments,” UN OCHA Policy Development and Studies Branch, Policy and Studies Series, 2011, unocha.org/sites/unocha/files/Stay_and_Deliver.pdf, p. xiv.

- According to OCHA, a UN liaison official was stationed with the Israeli military during the 2006 Israel–Lebanon conflict to monitor targeting and point out deconflicted sites, with some success. Deconfliction measures also “ultimately ended the [Israeli] strikes that had affected UN facilities and programme assets” in the Gaza Strip conflict that raged between December 2008 and January 2009. Jan Egeland, Adele Harmer, and Abby Stoddard, “To Stay and deliver: Good practice for humanitarians in complex security environments,” UN OCHA Policy Development and Studies Branch, Policy and Studies Series, 2011, unocha.org/sites/unocha/files/Stay_and_Deliver.pdf, p. 25. However, reports persist of Israeli air strikes and shelling of hospitals and medical staff whenever conflict flares, and deconfliction measures appear to be far from a full success. See for example “Israel/Gaza: Attacks on medical facilities and civilians add to war crime allegations,” Amnesty International, July 21, 2013, https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/news/2014/07/israelgaza-attacks-medical-facilities-and-civilians-add-war-crime-allegations; “Mounting evidence of deliberate attacks on Gaza health workers by Israeli army,” Amnesty International, August 7, 2014, https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/news/2014/08/mounting-evidence-deliberate-attacks-gaza-health-workers-israeli-army.

- UN OCHA Yemen – Deconfliction Liaison Team presentation, April 4, 2018, humanitarianresponse.info/sites/www.humanitarianresponse.info/files/documents/files/deconfliction_workshop_april_18.pdf; Ben Parker, “What is humanitarian deconfliction?,” The New Humanitarian, November 13, 2018, thenewhumanitarian.org/analysis/2018/11/13/what-humanitarian-deconfliction-syria-yemen; “Deconfliction,” Humanitarian Response, humanitarianresponse.info/en/operations/yemen/deconfliction. Site visited on May 19, 2019.

- For example, “MSF hospital destroyed by airstrikes,” MSF, October 26, 2015, msf.org/yemen-msf-hospital-destroyed-airstrikes; “Yemen: Bombing of MSF hospital may amount to a war crime,” Amnesty International, October 27, 2015, amnesty.org/en/latest/news/2015/10/yemen-bombing-of-msf-hospital-may-amount-to-a-war-crime; Rick Gladstone, “Saudi Airstrike Said to Hit Yemeni Hospital as War Enters Year 5,” New York Times, March 26, 2019, nytimes.com/2019/03/26/world/middleeast/yemen-saudi-hospital-airstrike.html.

- Transcript of Mark Lowcock’s remarks at Johns Hopkins University, October 30, 2018, reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/USGSAISAsDelivered-converted.pdf.

- In addition (and perhaps redundantly), the mechanism has since late 2015 shared its information with Russia and the United States in their capacity as co-chairs of the International Syria Support Group, an ad hoc assembly of nations involved with the Syrian peace process that was formed in 2015. UN OCHA-Turkey, “Humanitarian Deconfliction Mechanism: Humanitarian Organisations Operating in Syria,” Humanitarian Response, February 21, 2018, humanitarianresponse.info/sites/www.humanitarianresponse.info/files/documents/files/deconfliction_syria_for_static_non_static_feb2018_eng.pdf.

- UN OCHA-Turkey, “Humanitarian Deconfliction Mechanism: Humanitarian Organisations Operating in Syria,” Humanitarian Response, February 21, 2018, humanitarianresponse.info/sites/www.humanitarianresponse.info/files/documents/files/deconfliction_syria_for_static_non_static_feb2018_eng.pdf.

- Ben Parker, “What is humanitarian deconfliction?,” The New Humanitarian, November 13, 2018, thenewhumanitarian.org/analysis/2018/11/13/what-humanitarian-deconfliction-syria-yemen.

- “SAMS and 11 Humanitarian Organizations Share Hospital Coordinates,” Syrian American Medical Society, April 4, 2018, sams-usa.net/press_release/sams-11-humanitarian-organizations-share-hospital-coordinates.

- Aron Lund, “As Turkey and Russia pull the strings in Syria’s Idlib, civilians pay the price,” The New Humanitarian, May 21, 2019, thenewhumanitarian.org/analysis/2019/05/21/turkey-and-russia-pull-strings-syria-idlib-civilians.

- Khaled al-Khateeb, “خريطة الانتشار العسكري في جبهات ادلب ومحيطها,” al-Modon, May 15, 2019, almodon.com/arabworld/2019/5/14/خريطة-الانتشار-العسكري-في-جبهات-ادلب-ومحيطها. On Idlib’s rebel-jihadi landscape, see Aron Lund, “Syria’s Civil War: Government Victory or Frozen Conflict?,” Swedish Defence Research Institute (FOI), December 2018, foi.se/rapportsammanfattning?reportNo=FOI-R–4640–SE, pp. 52–58.

- “Assistant Secretary-General for Humanitarian Affairs and Deputy Emergency Relief Coordinator, Ursula Mueller – Briefing to the Security Council on the humanitarian situation in Syria, New York, 28 May 2019,” ReliefWeb, May 28, 2019, reliefweb.int/report/syrian-arab-republic/assistant-secretary-general-humanitarian-affairs-and-deputy-emergency-5. No reliable numbers were available for combatant deaths on either side.

- Author’s communication with Mari Mørtvedt, a Damascus-based spokesperson for the International Committee of the Red Cross, May 15, 2019.

- Transcript of Mark Lowcock’s briefing to the UN Security Council, ReliefWeb, May 17, 2019, reliefweb.int/report/syrian-arab-republic/under-secretary-general-humanitarian-affairs-and-emergency-relief-90.

- “مركز حميميم: التوصل إلى اتفاق لوقف تام لإطلاق النار في إدلب برعاية روسيا وتركيا,” Rusiya al-Yawm, June 12, 2019, bit.ly/31y9Z4P.

- “قائد أحرار الشام يوضح حقيقة وجود هدنة مع الروس في ريف حماة,” Nedaa Souriya, June 12, 2019, nedaa-sy.com/news/14081; “المتحدّث باسم الجبهة الوطنية ينفي للدرر تقارير عن هدنة مؤقتة في حماة وإدلب,” al-Dorar al-Shamiya, June 12, 2019, eldorar.com/node/136472; Khaled Zanklo and Mohammed Ahmed Khebbazi, “ميليشيات تركيا ترفض هدنة الأيام الثلاثة والنصرة تخرقها,” al-Watan, June 13, 2019, alwatan.sy/archives/201077.

- “Turkey says ceasefire not yet secured in Syria’s Idlib as soldiers hurt in ‘deliberate’ regime attack,” I24 News/AFP, June 13, 2019, https://www.i24news.tv/en/news/international/middle-east/1560419012-turkey-says-three-soldiers-hurt-in-deliberate-syria-regime-attack.

- Transcript of Ursula Müller’s briefing to the UN Security Council, ReliefWeb, May 28, 2019, reliefweb.int/report/syrian-arab-republic/assistant-secretary-general-humanitarian-affairs-and-deputy-emergency-5.

- Latamneh Hospital, April 28, Hama Governorate; Qalaat al-Madiq Hospital, April 28, Hama Governorate; Hbeit Primary Healthcare Center, April 30, Idlib Governorate; Qastun Primary Healthcare Center, May 1, Hama Governorate; Surgical unit in the Kafranboudheh area, May 1, Hama Governorate; Qalaat al-Madiq Primary Healthcare Center, May 2, Hama Governorate; Primary Health Care Centre in Rakaya Sejneh, May 3, Idlib Governorate; Hass Hospital, May 5, Hama Governorate (deconflicted); Maghara Hospital in Kafr Zita, May 5, Hama Governorate (deconflicted); Kafranbel Hospital, May 5, Idlib Governorate (deconflicted); Al-Amal Orthopedic Hospital, May 6, Idlib Governorate; Zerbeh Primary Healthcare Center, May 6, Aleppo Governorate (deconflicted); Kafranboudheh Primary Health Care Center, May 7, Hama Governorate (deconflicted); Middle al-Ghab Primary Health Care Center, May 7, Hama Governorate; Ambulance driver, May 8, Idlib Governorate; Kafr Zita Primary Health Care Center, May 8, Hama Governorate. (deconflicted); Maarr Tahroma Primary Health Care Center, May 8, Idlib Governorate; Has Hospital in Kafranbel, May 9, Idlib governorate (deconflicted; second attack); al-Sham Central Hospital, May 11, Idlib Governorate; Middle al-Ghab Primary Health Care Center, May 11, Hama Governorate (second attack); Al-Hawash Women and Pediatrics (112) Hospital, May 11, Hama Governorate; Tarmla hospital, May 15, Hama Governorate (deconflicted); Hama ambulatory center, May 23, Hama Governorate; the Al-Nafs Al-Mutmainnah Mental Health Center in Dana, May 28, Idlib Governorate (deconflicted; attack with an IED); Atareb Surgical Hospital, May 28, Aleppo Governorate (deconflicted). List provided to the author by Mohamed Katoub on June 3, 2019; slightly edited for clarity and transliteration.

- “Syrian-Russian Alliance Forces Target 24 Medical Facilities in the Fourth De-Escalation Zone Within Four Weeks,” Syrian Network for Human Rights, May 29, 2019, sn4hr.org/blog/2019/05/29/53713

- “Press briefing note on Idlib,” UN Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, May 21, 2019, ohchr.org/EN/NewsEvents/Pages/DisplayNews.aspx?NewsID=24632&LangID=E.

- World Health Organization, “WHO condemns the attack on three health facilities in north-west Syria,” ReliefWeb, May 3, 2019, reliefweb.int/report/syrian-arab-republic/who-condemns-attack-three-health-facilities-north-west-syria.

- “Syria Crisis: North-West Syria Update,” Issue 1, May 1-15, 2019, World Health Organization, May 2019, applications.emro.who.int/docs/SYR/COPub_SYR_NW_crisis_1_2019_EN.pdf.

- Transcript of Mark Lowcock’s briefing to the UN Security Council on May 17, 2019, available via ReliefWeb at reliefweb.int/report/syrian-arab-republic/under-secretary-general-humanitarian-affairs-and-emergency-relief-90. Lowcock’s remarks applied to the situation on May 17, when the number of clinics reported to have been bombed stood at eighteen and a total of forty-nine clinics were reported to have shut down.

- Katoub said six of the nine clinics were supported by SAMS, with the remaining three linked to other NGOs. Author’s communication with Mohamad Katoub, online messaging service, June 2, 2019.

- “BREAKING: 2 More Medical Facilities Bombed Today In Syria,” UOSSM, May 6, 2019, uossm.org/breaking_2_more_medical_facilities_bombed_today_in_syria.

- “Syrian-Russian Alliance Forces Target 24 Medical Facilities in the Fourth De-Escalation Zone Within Four Weeks,” Syrian Network for Human Rights, May 29, 2019, sn4hr.org/blog/2019/05/29/53713.

- “44 Syrian and international NGOs call for immediate end to attacks on civilians and hospitals in Idlib,” FIDH, May 24, 2019, fidh.org/en/international-advocacy/united-nations/security-council/44-syrian-and-international-ngos-call-for-immediate-end-to-attacks-on.

- Author’s interview with Lynn Maalouf, Middle East research director for Amnesty International, online messaging service, May 2019.

- Josie Ensor, “Syria and Russia bomb hospitals in Idlib after they were given coordinates in hope of preventing attacks,” Daily Telegraph, May 30, 2019, telegraph.co.uk/news/2019/05/30/syria-russia-bomb-hospitals-idlib-given-coordinates-hope-preventing.

- “Security Council Briefing on the Situation in Syria, Under-Secretary-General Rosemary A. DiCarlo,” UN Department of Political and Peacebuilding Affairs, May 17, 2019, dppa.un.org/en/security-council-briefing-situation-syria-under-secretary-general-rosemary-dicarlo.

- Transcript of Mark Lowcock’s briefing to the UN Security Council on May 17, 2019, available via ReliefWeb at reliefweb.int/report/syrian-arab-republic/under-secretary-general-humanitarian-affairs-and-emergency-relief-90.

- Official record of the UN Security Council’s 8527th meeting, S/PV.8527, May 17, 2019, undocs.org/en/S/PV.8527.

- Official record of the UN Security Council’s 8527th meeting, S/PV.8527, May 17, 2019, undocs.org/en/S/PV.8527.

- Official record of the UN Security Council’s 8527th meeting, S/PV.8527, May 17, 2019, undocs.org/en/S/PV.8527.

- Official record of the UN Security Council’s 8527th meeting, S/PV.8527, May 17, 2019, undocs.org/en/S/PV.8527. For the original Arabic, see “الجعفري: اتفاق خفض التصعيد في إدلب مؤقت ومن واجب أي دولة حماية مواطنيها من خطر الإرهاب-فيديو,” SANA, May 17, 2019, sanasyria.org/?p=947816.

- Official record of the UN Security Council’s 8527th meeting, S/PV.8527, May 17, 2019, undocs.org/en/S/PV.8527. For the Russian government’s translation, see “Statement by Permanent Representative Vassily Nebenzia at the UN Security Council Meeting on Syria,” Russian Mission to the United Nations, May 17, 2019, russiaun.ru/en/news/syria170519.

- “Russia says US launched campaign to blame it for Idlib hospital strikes,” TASS, May 23, 2019, tass.com/politics/1059633.

- “Syria: Security Council must address crimes against humanity in Idlib,” Amnesty International, May 17, 2019, amnesty.org/en/latest/news/2019/05/syria-security-council-must-address-crimes-against-humanity-in-idlib.

- Author’s interview with Lynn Maalouf, Middle East research director for Amnesty International, online messaging service, May 2019.