For more than two years, Lebanon has been in economic free fall. Its currency, the lira, has lost almost 95 percent of its value. Household basics have become impossibly expensive for many. Syrian refugee women and children have been begging in the streets of the capital, Beirut, for years; now, bent-over Lebanese pensioners also sometimes stop you to ask for a handful of lira. Traffic lights no longer work at major Beirut intersections—cars tentatively feel their way through, relying on fellow drivers’ etiquette and restraint. There is less traffic, anyway, since Lebanon’s cash-strapped government abandoned fuel subsidies and gasoline prices skyrocketed. State-provided electricity comes only a few hours a day. Some corner stores seem to have given up on refrigerating perishables. At night, parts of the city are eerily dark, lit only by a few storefronts powered by private generators, or by young men with headlamps digging through dumpsters.

This is Lebanon’s ongoing existential crisis. It is also the focus of the United States’ current Lebanon policy, as the administration of Joe Biden tries to prevent the country from disintegrating further.

This kind of American attention to Lebanon is new. For years, Hezbollah, the political party and Iran-backed paramilitary organization that is the United States’ main adversary in Lebanon, has been the primary focus of U.S. policy in the country. Other Lebanon-related issues have been treated like a subset of that main policy—countering Hezbollah’s influence. The Biden administration, by contrast, has adopted a sort of dual Lebanon policy, or policies: one for Lebanon, and one for Hezbollah.

Good—that type of bifurcation makes sense. Lebanon deserves American policy attention in its own right, as it suffers an economic collapse almost unprecedented in modern history.1 The United States should be trying to rescue Lebanon from total failure, or at least to prevent the country’s ongoing catastrophe from getting even worse.

Countering Hezbollah’s influence, meanwhile, is a mostly separate objective, to be pursued independently. Undercutting Hezbollah has long been the United States’ top priority in Lebanon; there’s little reason to expect that will change.

But the United States should keep its efforts to counter Hezbollah mostly separate from its newly urgent calls for the reforms needed to unlock large-scale international assistance and save Lebanon’s failing economy. Mixing these two objectives is a recipe for muddled thinking and bad policy outcomes. Hezbollah is not central to Lebanon’s economic crisis. U.S. officials need to be consistent and disciplined in their messaging to Lebanese counterparts on the reforms necessary for economic rescue. Framing U.S. calls for reform in counter-Hezbollah terms will just undercut the seriousness of U.S. messaging and reinforce the common Lebanese impression that, really, the U.S. only cares about one thing: Hezbollah.

Washington needs to distinguish between its two overriding objectives in Lebanon, and to understand the ways in which they do and do not relate. After all, Lebanon’s present crisis is a wicked policy problem; it requires a Lebanon policy distinct from U.S. efforts to counter Hezbollah. If the United States hopes to prevent Lebanon from collapsing further, it needs to walk and chew gum at the same time.

Preventing a “Failed State”

In December, a senior Biden administration official offered reporters an overview of the U.S. president’s Middle East policy.2 In Lebanon, the official said, the administration is working to prevent the country from becoming another “failed state” in the Middle East, and a source of broader instability. To that end, the United States is working with France and other partners to encourage Lebanese officials to pursue reforms that will unlock international rescue funds. In parallel, Washington is levying sanctions on corrupt Lebanese political figures; the administration is thus pushing for reform with “a combination of carrots and sticks,” as the official put it. The official also highlighted U.S. support for a World Bank deal that would partially stabilize Lebanon’s dysfunctional, hugely costly energy sector.3

It is debatable whether Lebanon is already a failed state, definitionally; certainly, it is failing.4 But as bad as things have gotten, the country can still fail further. Preventing that is a salutary goal.

Lebanon has been suffering an economic meltdown since 2019, when a “Ponzi scheme” that supported Lebanon’s state finances, economy, and currency finally collapsed.5 In the ensuing two years, the country has been additionally hit by the COVID-19 pandemic and by a massive blast at the Beirut port in August 2020, which killed more than two hundred people and devastated the city.

The lira price of food and nonalcoholic beverages in Lebanon rose by 2,067 percent between December 2018 and October 2021.

The consequences of Lebanon’s crisis have been calamitous. Rampant inflation has put food and other basics out of reach for many.6 The lira price of food and nonalcoholic beverages rose by 2,067 percent between December 2018 and October 2021, according to Lebanon’s Central Administration of Statistics; the price of clothing and footwear increased 1,911 percent during the same period.7 The UN estimates that four-fifths of Lebanon’s population was already living in poverty last August; more than a third was in extreme poverty, a proportion that the UN expected would rise to half of the country by the end of 2021.8 According to one estimate, 300,000 people emigrated from Lebanon last year.9 Nearly two-thirds of respondents told pollsters they would leave the country permanently if they could.10

It seems only appropriate that the White House official’s December summary of Lebanon policy focused on the country’s grave economic situation. Still, it’s a little unusual that the official’s overview did not mention Hezbollah.

This does not mean, of course, that the Biden administration has given up the longstanding U.S. aim of curtailing Hezbollah’s capabilities and influence, both inside Lebanon and across the region.11 Biden officials may not be engaging in their Donald Trump-era predecessors’ anti-Hezbollah theatrics, but under Biden, the U.S. Treasury has repeatedly sanctioned alleged Hezbollah financiers to deprive the organization of resources.12 When Australia designated Hezbollah a terror organization in November, the Biden administration expressed its support.13

But circumscribing Hezbollah is a long-term project, and whatever gains the United States manages to achieve will likely be incremental and small. Hezbollah has, over time, developed a complex set of military and civilian institutions, and a still-robust social support base; the organization is resilient.

Preventing Lebanon’s total collapse, on the other hand, is not a long-term project. Lebanon is imploding, now, and requires immediate action. It makes sense, then, that the Biden administration seems to be focusing first on its Lebanon policy—preventing a failed state—and playing out its Hezbollah policy in parallel.

Learn More About Century International

Lebanon’s National Bankruptcy

Lebanon’s present crisis is not principally about Hezbollah. Instead, it seems better understood as the ugly, protracted bankruptcy of Lebanon’s financial industry, in which the country’s powerful financial elites—backed by their political allies—are fighting to improve their position in any final settlement.

Lebanon’s political and financial elites are deeply enmeshed; some Lebanese have dubbed this combined elite “Hezb al-Masref” (the “Bank Party”).14 For decades, this combined elite used assorted chicanery to finance their patronage, corruption, and general fiscal irresponsibility. Most critically, Lebanon’s central bank (Banque du Liban) and its commercial banks engaged in a years-long pyramidal confidence scheme in which private banks lent depositors’ money to the central bank, which, in turn, used those funds to support the local currency and maintain its fixed value relative to the dollar. This currency “peg” helped keep imports to Lebanon artificially cheap.15

By mid-2019, though, this scheme had begun to come apart. When Lebanese took to the streets in October 2019 to protest politicians’ incompetence and corruption, the country’s banks shut their doors and denied depositors access to their accounts. The resulting crisis of confidence in the financial system rendered the Lebanese state, central bank, and private banking sector suddenly insolvent.

International donors have since conditioned a desperately needed bailout on an agreement between the Lebanese government and the International Monetary Fund (IMF), which insists first on difficult reforms.16 But Lebanese elites, not surprisingly, have seemed unenthusiastic about reforming away their power and privileges. They have demonstrated an extreme lack of urgency on IMF-demanded reforms, as well as on other crisis response measures like a World Bank-financed social safety net program.17 What’s more, influential political and economic figures have, at key junctures, sabotaged steps required by the IMF that would have jeopardized those elites’ interests.18

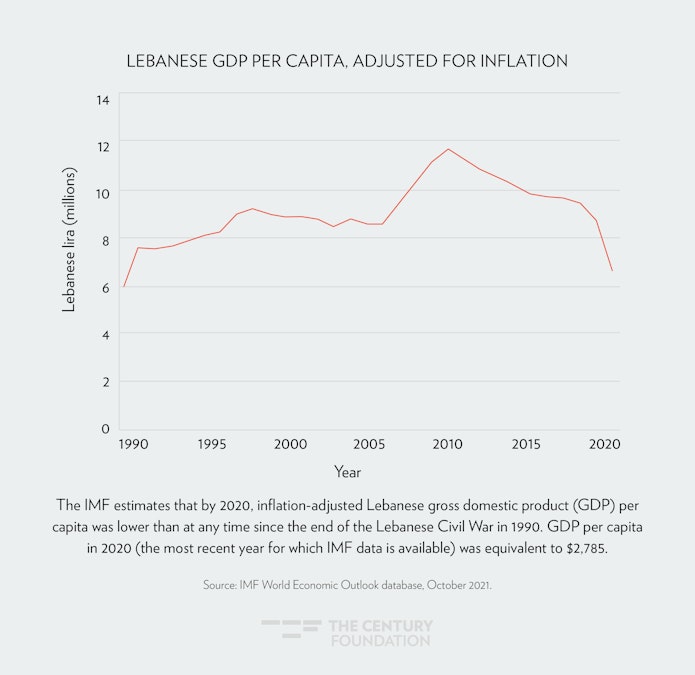

FIGURE 1

At issue is who will shoulder the massive losses that have resulted from Lebanon’s financial collapse.19 In a bankruptcy proceeding, there is a defined order in which a firm’s creditors are compensated: typically secured creditors come first; then unsecured creditors; and, last in line, shareholders. Lebanon, as a country, is insolvent. So is its central bank, and so are its commercial banks, which took on huge, irresponsible exposure to Lebanon’s sovereign debt by lending to the central bank. Any fair and orderly distribution of the losses to Lebanon’s economy would come at the expense of the powerful political and financial interests atop these institutions.

The banks are trying to save themselves at the expense of Lebanon’s people and what remains of the Lebanese state.

But Lebanon’s elites are attempting instead to invert the hierarchy of creditors in this national bankruptcy. This is why they are blocking measures sought by the IMF and foreign donors—for example, audits of public institutions, including the central bank; the unification of the country’s multiple exchange rates; and a capital control law—and allowing the country’s ongoing crisis to effectively shift losses to banks’ small depositors and the general public.20 Most of the country’s private banks should no longer exist; their shareholders ought to be wiped out. Instead, the country’s association of banks has proposed a massive transfer of Lebanese public assets to a fund whose revenues would compensate banks for their reckless lending.21 The banks are trying to save themselves at the expense of Lebanon’s people and what remains of the Lebanese state.

Lebanon’s elites are doing everything they can to position themselves favorably in the country’s eventual economic dispensation, and demolishing Lebanese society in the process. They are waging a class war—against the Lebanese public.

Hezbollah as Its Own Policy Problem

Hezbollah is not blameless in Lebanon’s collapse, but it also doesn’t seem to figure centrally into the country’s present crisis. Hezbollah is mostly excluded from Lebanon’s banking system. It has a more limited foothold in Lebanese state institutions, compared to other parties that have gotten fat on political patronage. Hezbollah has demonstrated its willingness to use violence against domestic rivals who threaten the party’s central mission of “resistance.”22 But the party doesn’t seem to be among the main Lebanese opponents of the types of reforms the IMF is seeking. Party officials say they’re open to an IMF agreement, although they warn they will resist regressive measures that hurt the country’s working class and poor.23

Meanwhile, some of the Lebanese figures most culpable for the country’s economic meltdown—notably, central bank governor Riad Salameh—have apparently benefited from U.S. forbearance precisely because they have been partners in excluding Hezbollah from international banking networks.

Hezbollah is a status quo force in Lebanon’s politics, broadly. But while it has opposed sweeping political change since 2019, it is only the single most powerful veto player in a system that is full of them. The party cannot simply dictate political outcomes, as evidenced by its failure to secure political agreement on last year’s efforts by Saad Hariri, then prime minister-designate, to form a government.

Still, policymakers in Washington often treat any Lebanon problem like a Hezbollah problem. In October, for example, the Senate Foreign Relations Committee’s co-chairs responded to new U.S. anticorruption sanctions on Lebanese figures by urging the Biden administration to issue additional sanctions “to counter Hezbollah’s malign influence and to ensure that Lebanese leaders uphold this government and take tangible steps to address Lebanon’s many challenges”—combining all these issues into a sort of pernicious mélange.24 Trump administration officials similarly tended to conflate countering Hezbollah with other U.S. policy priorities in Lebanon, and to situate the administration’s Lebanon policy within its efforts to “end Iran’s malign influence regionally.”25

The United States cares about Hezbollah for specific reasons, though, which are largely unrelated to Lebanon’s economy and to reform. Hezbollah mainly matters to Washington because of the threat it poses to Israel, in addition to the party’s security actions inside Lebanon and its contribution to the Iran-led regional alliance of state and paramilitary actors branded the “Axis of Resistance.” None of these concerns are clearly linked to Lebanon’s present crisis. Lebanon’s economic implosion does not seem, for example, to have substantially changed the military calculus of either Hezbollah or Israel, or to have made renewed conflict more likely.

Not all Lebanese agree that Hezbollah ought to be considered apart from Lebanon’s political-economic collapse. Some maintain that Hezbollah is the principal defender and guarantor of Lebanon’s incumbent regime; that the key to saving Lebanon is restoring its national sovereignty; or that the solution to Lebanon’s crisis starts with liberating the country from “Iranian occupation.”26 Hezbollah has certainly contributed to Lebanon’s dysfunction, including, most recently, by boycotting meetings of Lebanon’s government for months over what Hezbollah alleges is the politicization of the investigation into the Beirut port blast.27 The party is unshakeable in its support for allies like the Free Patriotic Movement and the Amal Movement that are more directly implicated in Lebanon’s corruption and waste.28

But for U.S. policy purposes, Lebanon’s political-economic collapse mostly seems like its own issue. It merits action on its own terms, aimed at more immediate results. Hezbollah represents a largely separate, different problem.

Clear-Headed Thinking about U.S. Priorities

An effective policy on Lebanon starts with properly conceptualizing U.S. priorities. Countering Hezbollah’s influence and preventing a “failed state” in Lebanon—the latter being the Biden administration’s professed goal—are distinct lines of effort. To the extent possible, policymakers should try to untangle them.

Some overlap between these objectives is normal, of course. U.S. support for a World Bank–financed project to deliver Egyptian natural gas and Jordanian electricity to Lebanon, for example, seems primarily aimed at addressing Lebanon’s crippling electricity shortage and the Lebanese energy sector’s massive drain on public finances. Despite that, U.S. backing for the World Bank deal has an added counter-Hezbollah rationale, in that it serves as a rejoinder to Hezbollah’s unilateral imports of Iranian fuel to Lebanon via Syria.29 Meanwhile, U.S. pressure on Lebanese financial institutions to combat official corruption may also have some counter-Hezbollah utility, in that, notionally, anticorruption measures could close illicit finance channels that Hezbollah also exploits.30

But muddling Washington’s two main priorities in Lebanon can also produce less effective policy. Anything that signals the prime importance, for Washington, of countering Hezbollah could further undercut U.S. messages on reform. Lebanese bankers, for example, could be forgiven for assuming that those U.S. exhortations on anticorruption measures are unserious, if they believe that what Washington really cares about is Hezbollah. Or take the Trump administration’s November 2020 sanctions on leading Christian politician and Hezbollah ally Gebran Bassil.31 The sanctions were for alleged public corruption, but that justification was basically impossible to take at face value—it seemed clearly pretextual, particularly since, months earlier, the administration had targeted two other prominent politicians more straightforwardly as “Hezbollah enablers.”32 The Biden administration has announced more deliberate-seeming anticorruption sanctions, including sanctions on Jihad al-Arab, a public sector contractor seen as close to former prime minister Saad Hariri.33 Yet even those could be reasonably construed as targeting politicians who have worked with Hezbollah, as Hariri did in his last attempt at government formation. If U.S. “anticorruption” sanctions are principally seen as punishment for partnering with Hezbollah, then they will not send an effective message on reform.

U.S. backing for the World Bank deal has an added counter-Hezbollah rationale: it is a rejoinder to Hezbollah’s unilateral imports of Iranian fuel to Lebanon via Syria.

And Washington’s twin policy aims in Lebanon may at times be in even more direct conflict. It is officially the prerogative of Lebanon’s political leadership to remove the central bank governor, Salameh, who is the chief architect of the country’s disastrous national Ponzi scheme, the subject of multiple legal investigations in European jurisdictions, and generally an obstacle to IMF-demanded reforms. Yet Salameh is also widely seen in Lebanon as being backed by the United States.34 Whether Salameh remains as central bank governor will not be decided solely by Washington; he has other sources of strength. But it is unhelpful for perceived U.S. support for Salameh to further influence Lebanese politicians’ thinking, and thereby help offer him effective impunity. When Washington’s traditional partners in countering terrorism financing stand in the way of the reforms necessary for Lebanon’s national rescue, then U.S. decision-makers may have to make a choice.

It is, in any case, already difficult to convey to Lebanese leaders the necessity of reform. Lebanese politicians understand their own material interests and—whatever rhetorical commitment to reform they might make publicly, or in bilateral meetings—are understandably resistant to any change that might undermine them. The country’s political system encourages a preoccupation with communal insecurity and sectarian solidarity, in ways that run counter to good governance and reform. And Lebanon’s overheated, gossipy political-media discourse tends to distort outsiders’ positions on Lebanon and their attempts to weigh in on the country’s politics.

For all these reasons, American attempts to encourage reform might be misinterpreted or generally ineffective. Washington shouldn’t further risk undermining its messaging on reform with maximalist rhetoric about Hezbollah. Tying everything to Hezbollah distracts from other reform priorities, and in any case doesn’t really speak to the United States’ core concerns about the organization.

The United States can work to mitigate the real threat that Hezbollah poses to U.S. interests without letting that threat consume the rest of its Lebanon policy. It just needs to think clearly about its main priorities in Lebanon, and to understand how they might interact and complicate each other.

A Lebanon-Centered Lebanon Policy

The United States doesn’t need to give up on trying to counter Hezbollah. It just needs to treat Lebanon’s collapse as a policy problem in its own right, not a subset of combating Hezbollah or ending “Iran’s malign influence” in the region. And it needs to recognize that a policy to prevent a failed state in Lebanon, properly understood, is a policy that has to contend mainly with the so-called Hezb al-Masref—the Bank Party.

The Biden administration seems headed in the right direction. When senior State Department official Victoria Nuland visited Beirut in October, her remarks to local media focused on U.S. support for Lebanon and the necessity of reform—not Hezbollah.35 In December, Dorothy Shea, the U.S. ambassador to Lebanon, presented the administration’s anticorruption goals without making some strained connection to Hezbollah.36 For new anticorruption sanctions, the administration has made use of a non-Hezbollah sanctions authority from 2007 to target political figures for illicit enrichment and “undermining the rule of law.”37

U.S. officials don’t have to mention Hezbollah at every opportunity, because it is basically a given that any U.S. administration will continue pursuing counter-Hezbollah policies. The Biden administration is no exception. Washington just needs to recognize that preventing a failed state is its own policy priority, independent of Hezbollah. Thankfully, the Biden administration so far seems to get it.

This report is part of “Transnational Trends in Citizenship: Authoritarianism and the Emerging Global Culture of Resistance,” a TCF project supported by the Carnegie Corporation of New York and the Open Society Foundations.

header image: Supporters of Hezbollah mourn people killed in clashes in October 2021 in Beirut, during protests by Hezbollah and the Amal Movement against the Beirut port explosion investigation. Source: Marwan Tahtah/Getty Images

Notes

- “Lebanon Economic Monitor, Spring 2021: Lebanon Sinking (to the Top 3),” World Bank, May 31, 2021, https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/lebanon/publication/lebanon-economic-monitor-spring-2021-lebanon-sinking-to-the-top-3.

- “Background Press Call on Broad Middle East Regional Year-End Discussion,” White House, December 17, 2021, https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/press-briefings/2021/12/17/background-press-call-on-broad-middle-east-regional-year-end-discussion/.

- For more, see Sam Heller, “Lights on in Lebanon: Limiting the Fallout from U.S. Sanctions on Syria,” War on the Rocks, November 10, 2021, https://warontherocks.com/2021/11/lights-on-in-lebanon-limiting-the-fallout-from-u-s-sanctions-on-syria/.

- “Statement by Professor Olivier de Schutter, United Nations Special Rapporteur on Extreme Poverty and Human Rights, on His Visit to Lebanon, 1–12 November 2021,” Office of the High Commissioner on Human Rights, November 12, 2021, https://www.ohchr.org/en/NewsEvents/Pages/DisplayNews.aspx?NewsID=27789.

- “Un Chief Says ‘Ponzi Scheme’ Crashed Lebanon’s Finances—Video,” Reuters, December 22, 2021, https://www.reuters.com/markets/asia/un-chief-says-ponzi-scheme-crashed-lebanons-finances-video-2021-12-22/.

- Kabalan Farah, “Year-On-Year Inflation Remains in Triple Digits for 17th Consecutive Month,” L’Orient Today, December 21, 2021, https://today.lorientlejour.com/article/1285463/year-on-year-inflation-remains-in-triple-digits-for-17th-consecutive-month.html; “GIEWS Country Brief: Lebanon,” Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, January 7, 2022, https://reliefweb.int/report/lebanon/giews-country-brief-lebanon-07-january-2022.

- “Inflation in Figures,” Economic Statistics, Central Administration of Statistics, http://www.cas.gov.lb/index.php/economic-statistics-en.

- “Emergency Response Plan: Lebanon 2021–2022,” United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs, August 6, 2021, https://lebanon.un.org/en/139099-emergency-response-plan-lebanon-2021-2022.

- Hashem Osseiran (@HashemOsseiran), Twitter status, December 2, 2021, https://twitter.com/HashemOsseiran/status/1466333071746154502.

- Jay Loschky, “Leaving Lebanon: Crisis Has Most People Looking for Exit,” Gallup, December 2, 2021, https://news.gallup.com/poll/357743/leaving-lebanon-crisis-people-looking-exit.aspx.

- For a recapitulation of existing U.S. priorities in Lebanon, see “U.S. Relations with Lebanon,” U.S. Department of State, September 28, 2020, https://www.state.gov/u-s-relations-with-lebanon/.

- “Treasury Targets Hizballah Finance Official and Shadow Bankers in Lebanon,” U.S. Department of the Treasury, May 11, 2021, https://home.treasury.gov/news/press-releases/jy0170; “Treasury Sanctions International Financial Networks Supporting Terrorism,” U.S. Department of the Treasury, September 17, 2021, https://home.treasury.gov/news/press-releases/jy0362; “The United States and Qatar Take Coordinated Action Against Hizballah Financiers,” U.S. Department of the Treasury, September 29, 2021, https://home.treasury.gov/news/press-releases/jy0381; “Treasury Sanctions Hizballah Financiers in Lebanon,” U.S. Department of the Treasury, January 18, 2022, https://home.treasury.gov/news/press-releases/jy0558.

- “United States Welcomes Australia’s Intended Action Against Hizballah,” U.S. Department of State, November 26, 2021, https://www.state.gov/united-states-welcomes-australias-intended-action-against-hizballah/.

- See Nada Maucourant Atallah and Omar Tamo, “Dangerous Liaisons: How Finance and Politics Are Inextricably Linked in Lebanon—Part I of II,” L’Orient Today, January 15, 2021, https://today.lorientlejour.com/article/1248323/dangerous-liaisons-how-finance-and-politics-are-inextricably-linked-in-lebanon-part-i-of-ii.html.

- Ben Hubbard and Liz Alderman, “As Lebanon Collapses, the Man With an Iron Grip on Its Finances Faces Questions,” New York Times, July 17, 2021, https://www.nytimes.com/2021/07/17/business/lebanon-riad-salameh.html.

- Kabalan Farah, “On IMF Deal, a Large Gap Remains between Political Rhetoric and Reality,” L’Orient Today, January 7, 2022, https://today.lorientlejour.com/article/1286847/on-imf-deal-a-large-gap-remains-between-political-rhetoric-and-reality.html.

- Abby Sewell and Omar Tamo, “How the Government Fumbled a $246 Million World Bank Loan to Help Lebanon’s Poorest Families,” L’Orient Today, June 21, 2021, https://today.lorientlejour.com/article/1265858/how-the-government-fumbled-a-246-million-world-bank-loan-to-help-lebanons-poorest-families.html; Abby Sewell and Wael Taleb, “As Import Subsidies Gradually End, Delays Mire Two Major Programs to Support the Country’s Most Vulnerable,” L’Orient Today, October 23, 2021, https://today.lorientlejour.com/article/1278994/as-import-subsidies-gradually-end-delays-mire-two-major-programs-to-support-the-countrys-most-vulnerable.html.

- Nada Maucourant Atallah and Omar Tamo, “Dangerous Liaisons: How the ‘System’ Got the Better of the ‘Technocrats’—Part II of II,” L’Orient Today, January 15, 2021, https://today.lorientlejour.com/article/1248324/dangerous-liaisons-how-the-system-got-the-better-of-the-technocrats-part-ii-of-ii.html.

- Tom Perry and Maha El Dahan, “Analysis: Who Pays? Lebanon Faces Tough Question in IMF Bailout Bid,” Reuters, September 23, 2021, https://www.reuters.com/world/middle-east/who-pays-lebanon-faces-tough-question-imf-bailout-bid-2021-09-23/.

- For analysis of this apparent scheme, see Sami Atallah, Mounir Mahmalat, and Sami Zoughaib, “Hiding Behind Disaster: How International Aid Risks Helping Elites, Not Citizens,” Lebanese Center for Policy Studies, September 2020, https://www.lcps-lebanon.org/featuredArticle.php?id=337; Dan Azzi, “Thinking like Riad,” L’Orient Today, June 19, 2021, https://today.lorientlejour.com/article/1265692/thinking-like-riad.html.

- “Press Release—The Contribution of the Association of Banks in Lebanon to Lebanon’s Economic Recovery,” Association of Banks in Lebanon, May 21, 2020, https://www.abl.org.lb/english/abl-and-banking-sector-news/abl-news/-21/5/2020-بيان-صحافي; for analysis of the banks’ proposal, see Omar Tamo, “Could Selling off State Assets Save Lebanon’s Financial System? Not Even Close, a New Study Says,” L’Orient Today, January 28, 2021, https://today.lorientlejour.com/article/1249806/could-selling-off-state-assets-save-lebanons-financial-system-not-even-close-a-new-study-says.html.

- Most notably: Robert F. Worth and Nada Bakri, “Hezbollah Seizes Swath of Beirut From U.S.-Backed Lebanon Government,” New York Times, May 10, 2008, https://www.nytimes.com/2008/05/10/world/middleeast/10lebanon.html.

- Wael Taleb, “Hezbollah Agrees to IMF Help, under Conditions,” Al-Monitor, May 26, 2020, https://www.al-monitor.com/originals/2020/05/lebanon-economic-crisis-hezbollah-agrees-imf-deal.html.

- “SFRC Chairman Menendez, Ranking Member Risch Urge Biden Admin to Match EU Sanctions Framework to Secure Substantive Economic, Political Reform in Lebanon,” United States Senate Committee on Foreign Relations, October 29, 2021, https://www.foreign.senate.gov/press/chair/release/sfrc-chairman-menendez-ranking-member-risch-urge-biden-admin-to-match-eu-sanctions-framework-to-secure-substantive-economic-political-reform-in-lebanon.

- For example, see State Department official David Hale’s representation of administration policy at “U.S. Policy in a Changing Middle East” (committee hearing), United States Senate Committee on Foreign Relations, September 24, 2020, https://www.foreign.senate.gov/hearings/us-policy-in-a-changing-middle-east; see also political appointee David Schenker speaking after leaving government at “Middle East Policy from Trump to Biden: Views from Inside the State Department’s Near East Bureau,” Washington Institute for Near East Policy, March 10, 2021, https://www.washingtoninstitute.org/policy-analysis/middle-east-policy-trump-biden-views-inside-state-departments-near-east-bureau.

- For example, see “Souaid to Voice of Lebanon: Removing the Iranian Occupation Is the Real Key to Solving the Crisis in Lebanon” (in Arabic), Voice of Lebanon, December 10, 2021, https://www.vdl.me/news/سعيد-لصوت-لبنان-رفع-الاحتلال-الإيراني/.

- “Hezbollah, Amal End Boycott of Lebanon’s Cabinet amid Economic Crisis,” Reuters, January 15, 2022, https://www.reuters.com/world/middle-east/hezbollah-amal-end-boycott-lebanons-cabinet-amid-economic-crisis-2022-01-15/.

- For example, see Nada Maucourant Atallah, “Juicy Contract, Suspicious Call For Tenders—In the Murky Waters of Lebanon’s Floating Power Plants (Part I of II),” L’Orient Today, July 26, 2021, https://today.lorientlejour.com/article/1269444/juicy-contract-suspicious-call-for-tenders-in-the-murky-waters-of-lebanons-floating-power-plants-part-i-of-ii.html.

- For more, see Heller, “Lights on in Lebanon.”

- “L’Association des banques du Liban édulcore les remontrances du Trésor américain,” L’Orient-Le Jour, December 16, 2021, https://www.lorientlejour.com/article/1284995/lassociation-des-banques-du-liban-se-fait-sonner-les-cloches-par-le-nouveau-sous-secretaire-au-tresor-us.html.

- “Treasury Targets Corruption in Lebanon,” U.S. Department of the Treasury, November 6, 2020, https://home.treasury.gov/news/press-releases/sm1177.

- “Treasury Targets Hizballah’s Enablers in Lebanon,” U.S. Department of the Treasury, September 8, 2020, https://home.treasury.gov/news/press-releases/sm1116.

- “Treasury Targets Two Businessmen and One Member of Parliament for Undermining the Rule of Law in Lebanon,” U.S. Department of the Treasury, October 28, 2021, https://home.treasury.gov/news/press-releases/jy0440.

- For example, see Nada Maucourant Atallah, “How the Lebanese Investigation Targeting Riad Salameh Is Being Systematically Impeded,” L’Orient Today, January 14, 2022, https://today.lorientlejour.com/article/1287565/how-the-lebanese-investigation-targeting-riad-salameh-is-being-systematically-impeded.html.

- “Media Availability with Under Secretary of State for Political Affairs Victoria Nuland,” U.S. Embassy in Lebanon, October 14, 2021, https://lb.usembassy.gov/media-availability-with-under-secretary-of-state-for-political-affairs-victoria-nuland/.

- “Ambassador Dorothy C. Shea Remarks on International Anticorruption Day,” U.S. Embassy in Lebanon, December 9, 2021, https://lb.usembassy.gov/ambassador-dorothy-c-shea-remarks-on-international-anticorruption-day/.

- “Blocking Property of Persons Undermining the Sovereignty of Lebanon or Its Democratic Processes and Institutions (Executive Order 13441),” Federal Register, August 1, 2007, https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2007/08/03/07-3835/blocking-property-of-persons-undermining-the-sovereignty-of-lebanon-or-its-democratic-processes-and; “Treasury Targets Two Businessmen and One Member of Parliament,” U.S. Department of the Treasury.