When it comes to health care, young people have historically been the most uninsured age group. The Affordable Care Act (ACA), which is ten years old this year, made significant progress in closing that gap: the uninsurance rate for 18-to-34 year-olds dropped from 29 percent in 2010, before major ACA provisions took effect, to 14 percent a decade later. College students—many, though not all, of them being young—benefited significantly from these expansions. In this report, released in partnership with Young Invincibles, we analyze the ACA’s impact on students and find that its provisions contributed to significant increases in coverage since its passage ten years ago.

The dependent coverage provision, which allowed young adults to remain on their parents’ insurance until they were 26, had a measurable impact on coverage rates for young people broadly,1 and while some states already required that employer coverage include dependent students, employer insurance increased significantly for students after the ACA passed.2 But more students pursue a degree later in life today than ever before, and a larger share of today’s students come from low-income families;3 as a result, there were also many older students or students from families with fewer resources that relied on other options provided by the ACA.4 Our analysis of national survey data shows that the Medicaid expansion provision, which gave states the option of receiving a generous federal match to cover childless adults at or near poverty, was likely the most significant driver of increases in insurance coverage for college students. Since the Affordable Care Act passed a decade ago, those data show the following:

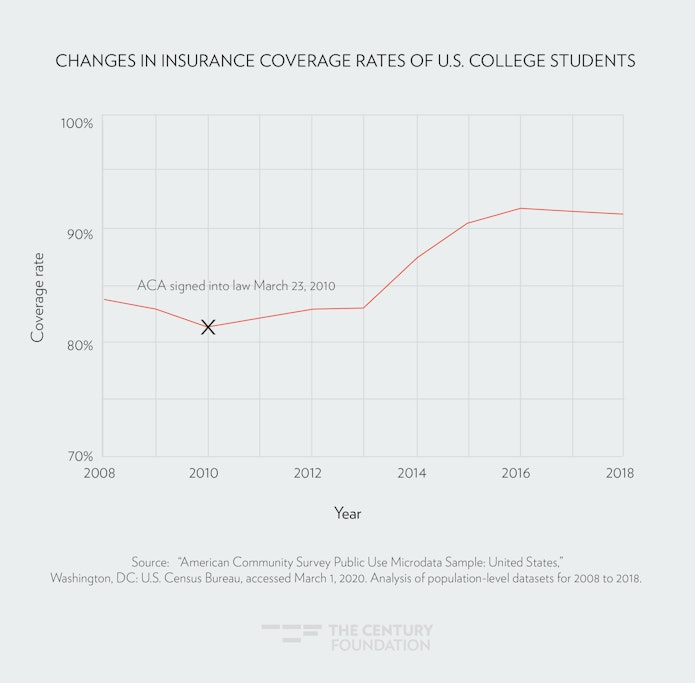

- Health insurance coverage amongst students increased by ten percentage points from 2010 to 2018, cutting the national uninsurance rate for students in half.

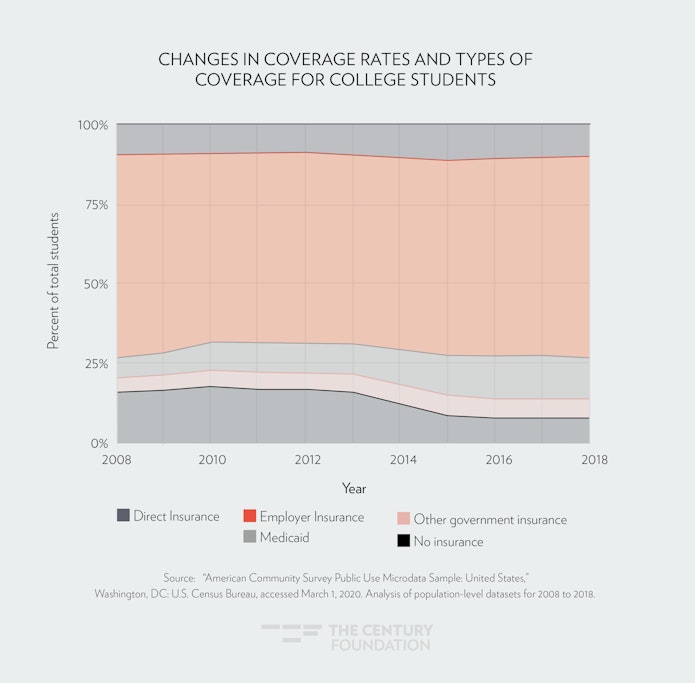

- The share of students enrolled in Medicaid has increased by five percentage points since the passage of the ACA, from 8 percent of students to 13 percent.

- Employer coverage for students has increased by four percentage points since the passage of the law—presumably driven by the dependent coverage provision.

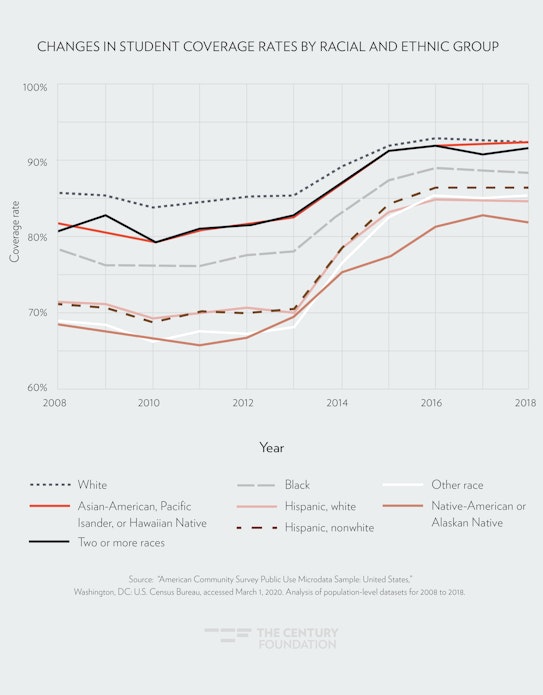

- The ACA was particularly impactful for students of color: since the law’s passage, the racial coverage gap for students narrowed across the board, and the gap for Hispanic students and black students when compared to white students was approximately cut in half. Hispanic students, whose coverage rates increased from 69 percent to 85 percent, saw the greatest gains.

- Given the role of Medicaid in increasing coverage for students, the expansion of the program in states that have not yet expanded would provide significant new protections currently uninsured students—and is more urgent given recent global events.

The law’s ten-year anniversary falls amidst a global pandemic and a severe economic downturn. Many students, like millions of Americans, have found their lives upended. Amidst this turmoil, the coverage improvements made under the ACA will provide critical protections for students. At the same time, the enormous coverage gap left open by states who have not expanded their Medicaid programs will become more apparent and put vulnerable students (and all Americans) at further risk, both in terms of their health and financial well-being.

Background

The Affordable Care Act contained a number of provisions changing the coverage landscape for students. The law added sweeping protections, including a ban on discrimination due to pre-existing conditions and a ban on discrimination based on gender.5 It also required that individual and small group insurance plans cover certain benefits such as preventive care and mental health services, and added financial assistance for low- and moderate-income individuals and families to purchase plans (families earning between 100 and 400 percent of the federal poverty level).6 And it provided access to free coverage for the lowest-income individuals through the expansion of Medicaid to childless adults living at or near poverty, a demographic group that includes many college attendees (a court case made that expansion optional on the part of states, rather than mandatory).7

The ACA also raised the standards for student health insurance, which had previously been largely unregulated and often provided those students with low-value coverage.8 Finally, it required health plans to offer coverage to children of enrollees up to the age of 26 (the dependent coverage expansion).

All of these protections and changes promised to impact students in a number ways. Certainly, the dependent coverage provision was designed to help many traditionally college-aged people. But almost 40 percent of students are older than 25, and would need to rely on other provisions.9 Moreover, a growing share of students come from families in the lowest income quintile (people earning in the bottom 20 percent of income);10 surveys point to high levels of food insecurity;11 and almost one-quarter have children of their own.12 All of these groups tended to have serious health care access issues before the ACA’s arrival, and so stood to benefit significantly from its provisions as well.

Despite those trends in student demographics, there has been a significant lag in the way that public benefits, financial aid, and institutional practices serve today’s students. Often these programs base eligibility on the assumption that students enroll in college right out of high school and can rely on middle-income or wealthy families to support them through their studies. Programs like the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) categorically exclude large swaths of students, such as most students without dependents who enroll in institutions of higher education at least half-time.13 Work requirements may make access to child care subsidies through the Child Care and Development Block Grant inaccessible to students, who have to split their time between work and class.14 And while many state financial aid programs offer support with tuition costs, many fail to address non-tuition costs, such as books, food, and rent. An increasing percentage of the college-going population can’t afford these costs, even with tuition-based aid and part-time work.15

The Affordable Care Act has gone against this grain. The law did not embed outdated assumptions about how students should access benefits, or who a student, demographically speaking, tends to be, or what they can afford. As a result, while many students gained coverage through employer coverage, likely due to the dependent coverage provision, the Medicaid program was responsible for the greatest gains in coverage.16

Student Coverage Increases under the Affordable Care Act

Using respondent data from the American Community Survey (ACS),17 the U.S. Census Bureau’s annual survey of representative samples of the population, we assessed changes in student coverage over the past decade through several demographic lenses. Since the law was enacted in 2010, coverage rates increased by ten percentage points. Even taking into account low coverage rates in 2010 due to the Recession, and comparing that year’s rates with 2008’s rates—a year that was less affected by Recession-driven coverage losses—coverage rates increased by eight percentage points.

FIGURE 1

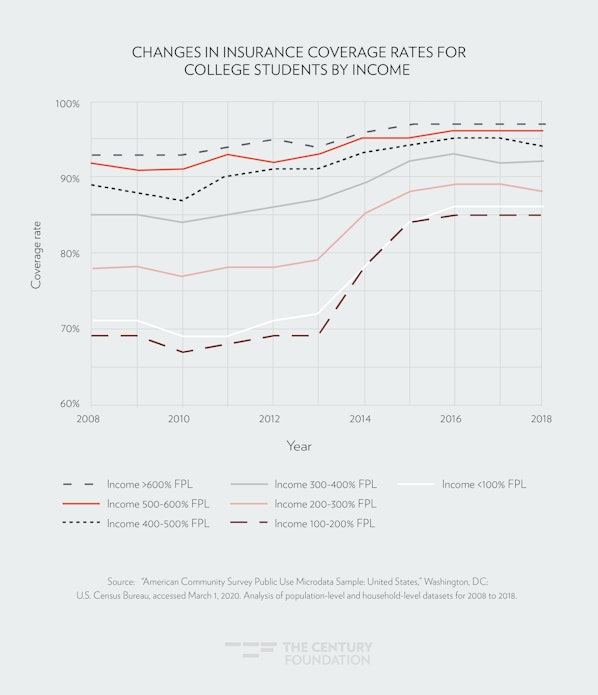

Coverage rates increased most significantly for students in poverty:18 In 2010, 69 percent of students living in poverty were insured; that number increased to 86 percent by 2018. The increase for students in households between 100 and 400 percent of the federal poverty level and who, if they met other eligibility requirements, would qualify for financial assistance, was also significant.19

FIGURE 2

The racial equity of health coverage for students has also significantly improved in the last decade, though gaps remain. Both white students and students of color saw gains after the Affordable Care Act passed, and the racial coverage gap amongst students narrowed significantly: The gap between coverage rates for white students and black students and between white students and Hispanic students have both been cut in half since the passage of the law. Rates increased the most for Hispanic students. Prior to the ACA, Hispanic students had a coverage rate of 69 percent. In 2018, their rate increased by 23 percent to 85 percent.

FIGURE 3

Given the increase in coverage amongst the lowest income students, the Medicaid program was responsible for the much of the increase in student coverage over the course of a decade. In 2008, 6 percent of students were enrolled in Medicaid, and that number rose during the Great Recession to 8 percent at the time the Affordable Care Act was enacted. As states took up the Medicaid expansion, the number increased to 13 percent.

Enrollment in private insurance also increased among low-income students, driven primarily by new enrollees in employer-sponsored insurance. It is likely that this increase resulted from the mandate that employer-sponsored insurance allow young people to stay on their parents’ plan until the age of 26.

FIGURE 4

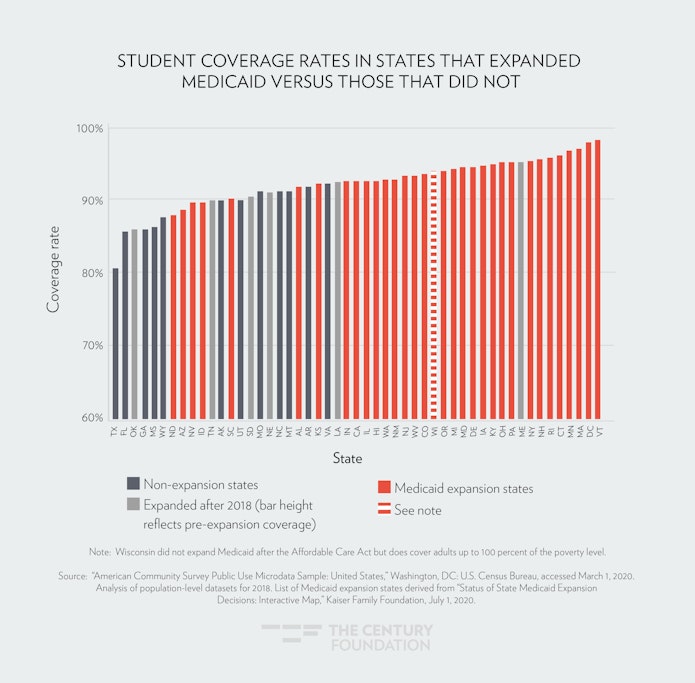

Because Medicaid was such a driver of new coverage, it is unsurprising that there is a significant difference in student coverage rates between states that opted to expand Medicaid to low-income childless adults and the states that didn’t: the former have a median coverage rate 3.4 percentage points higher than does the latter. Native-American and Hispanic non-white students particuarly benefitted in states that expanded Medicaid: from 2010 to 2018, the median Medicaid expansion state saw Native-American students’ coverage rate rise 8 percentage points over and above the coverage gain in the median non-expansion state. For Hispanic non-white students, this figure was 6 percentage points.20

FIGURE 5

Impact of Coverage on Higher Education

Studies have found that attainment of higher education is associated with increased coverage rates and better health outcomes,21 but the reverse may be true as well: as coverage, and ultimately health and financial security, improve, students may be more able to pursue education, stay in school, and succeed in their educational objectives.

In general, studies show that coverage has significant positive effects on a person’s health by improving access to services that prevent, diagnose, and treat chronic and acute conditions.22 The Medicaid expansion in particular has resulted in significant improvements in health access and affordability, outcomes, financial security, and even has been associated with a state’s economic growth.23 Studies on expansions of public health insurance have suggested long-run returns, including increases in college attendance and future earnings, in improving insurance access to children.24 And access to parental insurance pre-ACA was shown to increase full-time enrollment.25

Post-ACA research exploring the direct connection between student coverage and educational outcomes is limited so far, but early evidence is promising. Evidence shows that the dependent coverage provision freed up time for new insurance enrollees and resulted in increased time spent on educational activities.26 Two studies evaluating the impact of the dependent coverage provision found a positive impact on enrollment (though a third study found a negative effect on full-time enrollment).27 One study comparing states that expanded Medicaid to those that did not found that those that expanded saw an increase in the college enrollment and in college completion rates in less-than-two-year for-profit vocational certificates.28 This finding is perhaps not surprising, given that these institutions focus aggressive recruitment on low-income people of color (who were most likely to benefit from the Medicaid expansion) and have the most short, vocational certificate offerings for people coming from sectors that often do not offer insurance coverage.29

More research should be done on the effect of coverage on college enrollment, persistence, speed of completion, and even student debt levels. But given the balance of the findings so far, and the body of research showing the positive impact of health coverage on health outcomes and financial stability—both outcomes that will undoubtedly help students live and thrive as they pursue a certificate or degree—higher education institutions and policymakers should pursue strategies to expand health coverage among students, particularly focusing on connections for students to new options like Medicaid coverage (in the states that have made such expansions) as they build comprehensive plans to address the barriers to basic needs facing today’s students.

Conclusion

A significant body of research has shown that access to health coverage through the Medicaid expansion, and access to health coverage more broadly, have significant impact on health outcomes, financial security, and broader economic stability and growth. For students in particular, that may drive a decision to pursue an education, enable a student to complete a degree, and relieve students from medical debt or stress related to financial strain caused by uninsurance. As twelve states continue to drag their feet on expanding their Medicaid program, both the near-term health and economic turmoil, and long-term positive effects it can have on low-income students looking to pursue education—add all the more reason for those states to expand. And as institutions and policymakers consider interventions to support students, incorporating strategies to expand access to the options that the Affordable Care Act has made available and more accessible, and building on those efforts to provide new coverage options, should be a part of those efforts. Those efforts will become even more critical in the wake of the global pandemic.

Acknowledgement: Thanks to Christopher Davis for providing a review of our data analysis methodology.

Notes

- Joel C. Cantor, Alan C. Monheit, Derek DeLia, and Kristen Lloyd, “Early impact of the Affordable Care Act on health insurance coverage of young adults,” Health Serv Res. 47(5): 1773-1790 (October 2012)

- Michael Anderson, Carlos Dobkin, Tal and Gross, “The Effect of Health Insurance Coverage on the Use of Medical Services,” American Economic Journal: Economic Policy 4, 1-27 (2012)

- Jennifer Ma, Matea Pender, and Meredith Welch, “Education Pays 2019: The Benefits of Higher Education For Individuals And Society,” The College Board, 2019, https://research.collegeboard.org/trends/education-pays.

- Jennifer Ma, Patea Pender, and Meredith Welch, “Education Pays 2019: The Benefits of Higher Education for Individuals and Society,” CollegeBoard, 2019, https://trends.collegeboard.org/education-pays.

- Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, 42 U.S.C. § 18001 (2010).

- “Federal Poverty Level,” U.S. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid, accessed March 10, 2020, https://www.healthcare.gov/glossary/federal-poverty-level-fpl/.

- “Health Reform’s Medicaid Expansion,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, accessed March 10, 2020, https://www.cbpp.org/health-reforms-medicaid-expansion.

- “Relaxing Student Health Plan Rules Would Hurt Students and Be a Win for the Swamp,” Young Invincibles, 2017, https://younginvincibles.org/relaxing-student-health-plan-rules-would-hurt-students/.

- “Today’s Students,” Higher Learning Advocates, accessed March 10, 2020, https://higherlearningadvocates.org/policy/todays-students/.

- Jennifer Ma, Patea Pender, and Meredith Welch, “Education Pays 2019: The Benefits of Higher Education for Individuals and Society,” CollegeBoard, 2019, https://trends.collegeboard.org/education-pays.

- “Food Insecurity: Better Information Could Help Eligible College Students Access Federal Food Assistance Benefits,” United States Government Accountability Office, December, 2018, https://www.gao.gov/assets/700/696254.pdf.

- “Parents in College: By the Numbers,” Institute for Women’s Policy Research, April, 2019, https://iwpr.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/C481_Parents-in-College-By-the-Numbers-Aspen-Ascend-and-IWPR.pdf.

- 7 CFR Sec 273.

- Amy Ellen Duke-Benfield, Rosa Garcia, Lauren Walizer, and Carrie Welton, “Developing State Policy that Supports Low-Income, Working Students,” Center for Law and Social Policy, September, 2018, https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED592585.pdf.

- See e.g. Konrad Mugglestone, Kim Dancy, and Mamie Voight, “Opportunity Lost: Net Price and Equity at Public Flagship Institutions,” Institute for Higher Education Policy, September, 2019, http://www.ihep.org/research/publications/opportunity-lost-net-price-and-equity-public-flagship-institutions.

- Previous analysis of student health insurance coverage post-ACA was done by the Lookout Mountain Group through 2016. “Update for Uninsured College Student Population,” Lookout Mountain Group, February, 2018, https://docs.hbc-slba.com/access/227/vy_ID6Nb1NwMAI90zk9wcouMVKg/download/Update_for_Eight_Year_Review_American_Community_Survey_Uninsured_Student_Population_Update_2_13_18.pdf/.

- This report’s analysis of health care coverage among college students uses data from the American Community Survey Public Use Microdata Sample (ACS PUMS), a person-level dataset that includes key variables such as college enrollment and health care coverage. Because health care coverage is only available as a variable in the PUMS datasets from 2008 onwards, and because 2018 is the most recent edition available, we use the one-year ACS PUMS samples for 2008 through 2018. A full methodology is available upon request. U.S. Census Bureau; American Community Survey (ACS), One-Year Public Use Microdata Sample (PUMS), 2008–2012; generated by Peter Granville; accessed via ftp, March 1, 2020.

- In our analysis of coverage by income, three groups were excluded due to data limitations. (1) We filtered out household members who are not family with the head of household: their income is not reflected in the family income variable, making their income difficult to assess. (2) We filtered out students who live in college dormitories, due to insufficient information in the PUMS dataset about their family finances and what help they may be receiving from family. (3) We filtered out students living alone with personal income under $1,000. This threshold was established to exclude from the lowest income bracket students who have low personal income (which is reported in PUMS) while also receiving a large amount of financial help from middle- or high-income family members (which is not reported in PUMS). We do not believe a significant number of genuinely low-income students are excluded: according to the 2015–16 edition of the National Postsecondary Student Aid Survey (NPSAS), 72.3 percent of dependent students from families in poverty worked in the school year, and this figure would rise if summer employment were included. The personal income threshold was placed low, at $1,000, to be easily cleared by students who work.

- The ACS measure of family income reflects the income of familial members of the surveyed household and not the respondent’s tax household. As a result, the poverty levels may not match up exactly with how financial aid gets determined.

- For this analysis of improvements in coverage rates in expansion states vs. non-expansion states for college students of a specified race/ethnicity, a state was excluded for the analysis if it did not in both 2010 and 2018 have at least 50 college students included in our sample who identified as the specified race/ethnicity. For example, because North Dakota did not have at least fifty respondents in our dataset who are college students identifying as Hispanic non-white, North Dakota is not included in the set of states from which we derive the 6 percentage point difference.

- Robin A. Cohen, Emily P. Zammitti, and Michael E. Martinez, “Health insurance coverage: Early release of estimates from the National Health Interview Survey, 2017,” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, August, 2018; David Cutler and Adriana Lleras-Muney, “Education and Health: Evaluating Theories and Evidence,” National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper 123252, 2006; “Higher education and income levels keys to better health, according to annual report on nation’s health,” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2012; Anna Zajacova and Elizabeth M. Lawrence, “The Relationship Between Education and Health: Reducing Disparities Through a Contextual Approach,” Ann Review of Public Health 39, April, 2018.

- J. Michael McWilliams, “Health consequences of uninsurance among adults in the United States: Recent evidence and implications,” Milbank Q 87(2), 2009, 443-494. That being said, health insurance plays a modest role in explaining health disparities by education; see Anna Zajacova and Elizabeth M. Lawrence, “The Relationship Between Education and Health: Reducing Disparities Through a Contextual Approach,” Ann Review of Public Health 39, April, 2018.

- Larisa Antonisse, Rachel Garfield, Robin Rudowitz, and Madeline Guth, “The Effects of Medicaid Expansion under the ACA: Updated Findings from a Literature Review,” Kaiser Family Foundation, August 15, 2019, https://www.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/the-effects-of-medicaid-expansion-under-the-aca-updated-findings-from-a-literature-review-august-2019/.

- David W. Brown, Amanda E.Kowalski, A. and Ithai Z. Lurie, I, “Medicaid as an Investment in Children: What is the Long Term Impact on Tax Receipts?” National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper 20835, January, 2015; Sarah Cohodes, Daniel Grossman, Samuel Kleiner, and Michael F. Lovenheim, “The Effect of Child Health Insurance Access on Schooling: Evidence from Public Insurance Expansions” Journal of Human Resources 51(3), October, 2014, 727–759.

- Juergen Jung, Diane M. Harnek Hall, and Thomas Rhoads, “Does the Availability of Parental Health Insurance Affect the College Enrollment Decision of Young Americans?” Economics of Education Review 32, February, 2013, 49-65.

- Greg Colman and Dave Dhaval Dave, “It’s About Time: Effects of the Affordable Care Act Dependent Coverage Mandate on Time Use.” Institute of Labor Economics Discussion Paper No. 9710, 2016.

- Leonard M. Lopoo, Emily B. Cardon, and Kerri M. Raissian, “Health Insurance and Human Capital: Evidence from the Affordable Care Act’s Dependent Coverage Mandate.” J Health Political Policy Law 43(6), 2018, 917-939; Yajuan Li and Marco A. Palma, “Health Insurance and College Enrollment: Evidence from a Natural Experiment of the Affordable Care Act Dependent Coverage Mandate,” Selected Paper prepared for presentation at the 2017 Agricultural & Applied Economics Association Annual Meeting, Chicago, Illinois, July 30–August 1, 2017; Juergen Jung and Vinish Shrestha V, “The Affordable Care Act and College Enrollment Decisions,” Economic Inquiry 56(4), April 2018, 1980-2009.

- Rajashri Chakrabarti and Maxim Pinkovskiy, “The Affordable Care Act and the Market for Higher Education,” Federal Reserve Bank of New York Staff Reports, no. 873, July 2019, https://www.newyorkfed.org/medialibrary/media/research/staff_reports/sr873.pdf.

- Rajashri Chakrabarti and Maxim Pinkovskiy, “The Affordable Care Act and the Market for Higher Education,” Federal Reserve Bank of New York Staff Reports, no. 873, July 2019, https://www.newyorkfed.org/medialibrary/media/research/staff_reports/sr873.pdf.