This report is the third in a TCF series—The Cycle of Scandal at For-Profit Colleges—examining the troubled history of for-profit higher education, from the problems that plagued the post-World War II GI Bill to the reform efforts undertaken by the George H. W. Bush administration.

No secretary of education has been more critical of traditional higher education than William Bennett, President Ronald Reagan’s second and best-known education secretary. Barely five days after taking office in February 1985, Bennett accused the nation’s colleges of offering a low-quality education at too high a price, and he accused college students of spending frivolously on cars, stereos, and beach vacations—dismissing their complaints about proposed cuts in federal aid.1

Less than a year after Bennett took office, he took on a target that many of today’s Republicans might consider sacrilege: for-profit colleges. He did so in language that was far more damning of the industry than any statements by Obama administration officials. Far from just a case of some bad apples, according to Bennett there were “serious, and in some cases pervasive, structural problems in the governance, operation, and delivery of postsecondary vocational-technical education.”2

Republicans, who controlled the White House and the Senate in 1986, were caught somewhat off guard by the problems of predatory for-profit colleges. They thought they had largely resolved these issues in the prior GOP administration ten years earlier, when Bennett’s predecessor, Terrel Bell under President Ford, had adopted regulations allowing extra scrutiny of any school where more than 60 percent of students used federal loans and, separately, the Federal Trade Commission had issued a rule to prevent misleading job placement claims by for-profit schools. But by the start of the Reagan presidency in 1981, those rules were gone or weakened,3 and Democrats had opened the door to for-profit colleges enrolling students without high school diplomas.4 On top of that, the Reagan administration’s proposed cuts to education funding led to reduced enforcement staff, undermining the agency’s ability to keep for-profit colleges in check.5 Soon, the industry was rife with abuses once again.

The Cycle Of Scandal At For-Profit Colleges Series

Read the series of papers focusing on the repeated for-profit college scandals of the past sixty years.The GOP Reversal on For-Profit Colleges in the George W. Bush Era

When President George H. W. Bush “Cracked Down” on Abuses at For-Profit Colleges

The Reagan Administration’s Campaign to Rein In Predatory For-Profit Colleges

Vietnam Vets and a New Student Loan Program Bring New College Scams

Truman, Eisenhower, and the First GI Bill Scandal

The For-Profit College Story: Scandal, Regulate, Forget, Repeat

The GOP Has a Long History of Cracking Down on “Sham Schools”

Bill Bennett Goes on the Attack

At a January 1986 Senate hearing, Secretary Bennett testified that “Institutions are defrauding students, and in many cases they are ripping off the American public, when they admit individuals who are manifestly unprepared for the work that will be required of them, or when they graduate students who cannot satisfy minimum standards in their field of study.”6 He was alarmed that “some proprietary schools, accredited by the state or by accrediting agencies, are graduating large numbers of students who fail the relevant state licensing examination. Without their professional license, these graduates cannot find employment,” making them unlikely to be able to repay their loans.7

A skeptical Senator Ted Kennedy (D-MA) asked Bennett to name the institutions that were “defrauding students,” “ripping off the American public,” and admitting unprepared students. Bennett pointed to an August 1984 report by the U.S. General Accounting Office (now the Government Accountability Office, or GAO) which found that “83 percent of proprietary schools consistently failed to enforce academic progress standards” and, that of the 1,165 for-profit schools studied, “766 of them has misrepresented themselves during the recruitment process; 533 overstated job placement rates; 366 misrepresented scholarships; and 399 misrepresented themselves in advertising.”8

Over the next year, the burgeoning default crisis only worsened. The proportion of federal student aid dollars going to cover default payments—the figure that had first alerted Bennett to the scope of the problem—jumped substantially. In 1985, about a third of dollars in the federally guaranteed student loan program budget went to paying student defaults; by late 1987, the department was projecting that almost half of the student loan budget (47 percent) would be used the following year to pay for defaulted loans. Bennett was adamant that the default crisis required urgent federal intervention.

What was Bennett’s response to the default crisis? He decided to unilaterally initiate policy change through the regulatory process. In a November 1987 press conference, and in a simultaneous “Dear President” letter sent to all 7,200-plus college and university presidents whose institutions participated in the guaranteed student loan program, Bennett announced the Department of Education would develop new regulations to establish a trigger cutoff point for institutions receiving federal aid. Under the new regulations, postsecondary institutions whose students had a default rate above 20 percent on their guaranteed loans by December 1990 would immediately be subject to hearings to limit, suspend, or terminate their participation in federal student aid programs. In addition, Bennett ordered immediate investigations of the more than 500 postsecondary institutions that had default rates in excess of 50 percent. “It’s accountability time,” Bennett declared at his press conference. “The current situation is intolerable.”9

Bennett’s proposal disproportionately affected for-profit schools. Of the 2,190 institutions that had default rates above 20 percent in 1986, Bennett estimated 80 percent of the potentially affected institutions were proprietary.10 Institutions with uber-high default rates above 50 percent were even more concentrated among for-profits. The Department of Education projected that, in 1987, 600 proprietary schools had default rates above 50 percent, compared to only thirty-three other colleges.11 When Bennett was asked at his press conference about the impact of his proposal on the for-profit industry, he said the regulation “won’t close [all] proprietary schools. It will close those [that] deserve to be eliminated based on their irresponsible treatment of students.”12

The For-Profit Industry and Its Supporters Respond

The reaction to Bennett’s proposal from the for-profit industry was fast and furious. Stephen Blair, president of the National Associate of Trade and Technical Schools, said that Bennett’s proposal would deny “access to low-income minority students in this country. The impact of that is unconscionable.”13 Eleanor Vreeland, president and CEO of the Katherine Gibbs Schools, warned that Bennett’s “accusation and hyperbole leads to an environment of mass hysteria on the part of the media and sometimes policymakers.”14

Leading Democrats in Congress were quick to adopt the industry argument, asserting that for-profit schools had more defaults due simply to having lots of low-income and minority students, not because of institutional misbehavior and practices. Senator Ted Kennedy, the chairman of the Senate Labor and Human Resources Committee told Bennett at the start of a hearing one month after Bennett announced his plan, “Many schools with high default rates also serve a very high percentage of minority and disadvantaged students. I am especially troubled by any proposal that would eliminate large numbers of these schools and their students from the [guaranteed student loan] program.”15 When Senator Claiborne Pell (D-RI), the father of the Pell Grant program, suggested that for-profit schools instead be referred to as “taxpayer schools,” Bennett responded that while there were numerous model proprietary schools, there were “a lot of irresponsible proprietary schools, too—and whether they are paying taxes or not, they are ripping off students.”16

Under questioning from Senator Dan Quayle (R-IN), who would soon become Vice President in the Bush administration, Bennett said that in the “real world” there are “profit institutions out there that are interested only in that profit and not interested in students….We’ll put some of them out of business right now if we get the right message from this hearing.” Asked by Quayle if that would be a good outcome, Bennett cut him off: “You bet.” One of the “intended consequences” of his regulations, Bennett said, “would be to get institutions that are exploiting kids and exploiting taxpayers out of the business.”17

Bruce Carnes, the deputy undersecretary for education, defended the Reagan administration at the hearing from charges that a crackdown on proprietary schools would reduce access for disadvantaged students. Carnes, like his successors in the Obama administration, argued that just the reverse was the case—that it was the Reagan administration who was trying to maintain access for vulnerable and disadvantaged students to postsecondary training by protecting them from wasting their limited loan and grant dollars at schools where they “are victimized and taken advantage of.” Some schools, Carnes said, were sending “recruiters into unemployment offices to drag people with little chance of succeeding at their school out to go into their academic programs, and sign them up for federal student aid. There are virtually, in many instances, nonexistent standards for admission—if you can read or write, you are in. And these people, it seems to me, are the ones that we are trying to protect.”18

As the contentious hearing wore on, committee chair Ted Kennedy blasted Bennett for unfairly indicting the for-profit sector for the sins of a few and for failing to provide adequate data to prove his claims about institutional malpractice. Kennedy demanded: “We hear that we are going to save all these kids because we’ve got all these ‘hucksters’ who are out there, pulling kids out of unemployment lines, throwing them into proprietary schools and trying to make a buck on them. If you’ve got the evidence of that, let’s have it, Mr. Secretary, let’s have it. Let’s have it right now! Give me the studies that show what percent of them are out there, huckstering young kids. I’d like to hear that right now.”19

“Many for-profit schools do not exist to perform a service for young people seeking an education, but to use would-be students as a means to extract Guaranteed Loan money and Pell Grants from the Federal government to fill the pocketbooks of the school owners.”

Bennett was taken aback that Kennedy seemed to be dismissing the seriousness of trade school abuses. “The notion that, in the absence [of a pending Department of Education study], one cannot appreciate that there are institutions out there, ripping off kids, is astounding,” Bennett told Kennedy. “Everybody knows this, Senator; everybody knows this.” Undeterred, Kennedy pressed Bennett to specify the percentage of for-profit schools that were ripping off students. Bennett responded to Senator Kennedy by saying that “30 [percent], maybe 40 [percent]”—prompting Kennedy to ask, “in terms of the 30 or 40 percent that are effectively ripping off the kids, how do you define ‘ripping off the kids’?” Bennett responded that they were schools with “very low graduation rates; very high dropout rates; kids unable to find jobs after completing their studies, of those who do complete their studies.” He then quoted from a letter from the Legal Aid Bureau of United Charities of Chicago, which stated: “Many for-profit schools do not exist to perform a service for young people seeking an education, but to use would-be students as a means to extract Guaranteed Loan money and Pell Grants from the Federal government to fill the pocketbooks of the school owners.”20

The Department of Education Takes Action

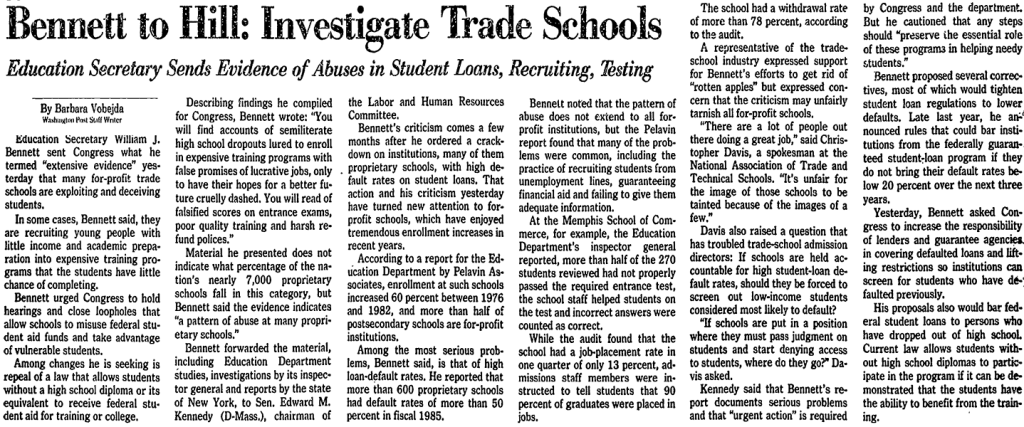

Three months after his dust-up with Kennedy, Bennett released the department’s study of for-profit schools that he had promised, sending it to Kennedy with a cover letter, along with reports from the department’s inspector general. While Senator Kennedy was no stranger to partisan or ideological battles, he nonetheless changed his position in response to Bennett’s well-documented evidence of problems at for-profit schools. “Secretary Bennett’s report documents serious abuses in federal student-aid programs,” Kennedy acknowledged in a press statement, adding that “urgent action” was required by “both Congress and the Department of Education to end the abuses while preserving the essential role of these programs in helping needy students.”21

The seventy-seven-page study, prepared by the consulting firm Pelavin Associates, drew news coverage across the country. In a scorching cover letter, Bennett wrote Kennedy that the Pelavin report and related documents provided “extensive evidence” of abuses by for-profit schools. “You will find,” Bennett wrote, “accounts of semiliterate high school dropouts lured to enroll in expensive training programs with false promises of lucrative jobs, only to have their hopes for a better future cruelly dashed. You will read of falsified scores on entrance exams, poor quality training and harsh refund policies.”22

Bennett stressed that these abuses were not isolated instances in the industry. “The pattern of abuses revealed in these documents,” Bennett concluded, “is an outrage perpetrated not only on the American taxpayer but most tragically, upon some of the most disadvantaged and most vulnerable members of society.”23 Congress, Bennett said, must close “legislative loopholes that invite unscrupulous schools to defraud the taxpayer and take advantage of vulnerable students.”24 As Bennett summarized for Time magazine: “The kids are left without an education and with no job, and the taxpayer ends up holding the bag for a kid who gets cheated.”25 Shortly afterwards, Bennett also sent a letter to the nation’s fifty governors, urging them to “undertake a thorough review and evaluation of all your State’s laws and regulations governing proprietary school licensing and operations. See if they need amendment, strengthening or more rigorous enforcement.”26

As Bennett summarized for Time magazine: “The kids are left without an education and with no job, and the taxpayer ends up holding the bag for a kid who gets cheated.”

In addition to talking a tough game, Bennett boosted enforcement of existing regulations and laws for trade schools in the months following the release of the Pelavin report. In a front-page leader headlined “Rip-Off Tech,” the Wall Street Journal reported that between March and September 1988, institutional reviews of schools by the Department of Education led to 116 indictments and 39 convictions. The Reagan administration “brought fraud charges against two of the largest trade school operations in the country,” Continental Training Services, Inc. and Wilfred American Education Corp., both of which subsequently closed their schools and declared bankruptcy; the department also “cut off federal aid to six Robert Finance Corp. schools in Florida and fined the company $1.5 million, the largest penalty ever against a U.S. school.”27

In the government’s fraud case against Continental Training Services, the Reagan administration alleged that the Indianapolis-based truck-driving trade school chain enrolled “anyone, regardless of their ‘ability to benefit,’ paying commissions to recruiters of up to $550 for each student. Some enrollees spoke no English . . . or had physical disabilities that meant they could never drive trucks. The government also alleges the school’s graduation rate was less than 40 percent, its students’ default rate was 57 percent, and its claimed job placement rate of 80 percent was ‘significantly inflated.’”28

While leading Democrats in the Senate had decided that action was needed to reduce abuses,29 the Democratic-controlled House of Representatives remained staunchly opposed to Bennett’s regulatory plans.30 The most important leader of the countercharge was Augustus Hawkins (D-LA), chairman of the House Education and Labor Committee. Hawkins was a staunch supporter of Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs), a founding member of the Congressional Black Caucus, and one of the authors of Title VII of the landmark 1964 Civil Rights Act. College presidents at HBCUs, most of which then had default rates above 20 percent, were distraught at the prospect of losing federal student aid under Bennett’s proposal. Of the ninety-five HBCUs receiving student aid in 1986, sixteen schools had a default rate of 50 percent or more and would be immediately targeted for program reviews under Bennett’s proposal.31

At the December 1987 Senate hearing, Senator Kennedy had asked Bennett if HBCUs with default rates above 20 percent were “ripping the kids off?” “No, not for the most part,”32 Bennett replied. But a few months later, deputy undersecretary Bruce Carnes was quoted in the Wall Street Journal saying of HBCUs, “It’s possible that their student bodies contain a high level of thieves.”33 While Carnes later said that his ugly statement was a misquote and that he “regretted the entire affair and the pain it has caused,” the damage was done. Hawkins’s committee began working on its own legislation to shield HBCUs and proprietary schools from losing student federal aid due to steep default rates.

At a House hearing in July 1988, Democratic lawmakers made clear that they felt it was unfair of Bennett to hold proprietary schools or HBCUs responsible for high rates of student defaults. Students, not institutions, were taking out the government loans, and private guaranty agencies and banks were extending the loans to students who were ill-prepared for college. Giving new meaning to the old higher education saw, “institutions don’t fail, students do,” Democratic lawmakers asked, what was a school to do?

Bennett, however, was unapologetic—his goal was “getting as many of the fraudulent or exploitive institutions out of business as possible.”34 He dismissed the Democrats’ critique of his proposal as little more than classic buck-passing in higher education. “Some of the educational institutions complained that we were putting the entire onus [or] burden on them,” Bennett observed. “Some lending institutions complain that we are putting the entire onus on them. One begins to get the idea here there is a pattern. Whenever you put an onus on someone, they tend to say ‘why are you picking on me?’ In fact, we have been consistent. We have said that there is shared responsibility here. To paraphrase Moby Dick, the ‘universal thump’ has been passed around.”35

The Legislative Bargaining Begins

Congressman Dick Armey (R-TX), a conservative stalwart, introduced the Reagan administration’s legislation to reduce student defaults and applauded the effort. Armey pledged at the committee hearings to “enthusiastically support” the administration’s bill and said it had “been a rather shocking two days to find these revelations” about institutional abuses of the guaranteed loan program.36 Bennett thanked Armey, and said that his core aim in pressing for accountability was to defend the shared goal of keeping “the unscrupulous . . . from preying on the ignorant and unsuspecting.”37

A month after Bennett testified, the House Committee on Education and Labor approved a bill introduced by Hawkins that reversed Reagan administration cuts to financial aid while also prohibiting the department from cutting off aid to high-default schools, as long as they implemented plans for reducing defaults. Not surprisingly, Bennett said that Hawkins’ bill was “seriously objectionable” and promised to recommend a veto if Congress sent it to President Reagan. Under the Hawkins approach, as deputy undersecretary Carnes pointed out at the June hearing, a college could have a 100 percent default rate and continue receiving federal financial aid.38

Bennett’s plans ultimately fell prey to election-year politics. In May 1988, Bennett announced that he would step down in the fall and was interested in supporting Vice President George H. W. Bush’s presidential run. Shortly before Bennett stepped down on September 20, the Department of Education formally issued its proposed rules for curbing loan defaults. The proposed rules contained Bennett’s 20 percent default rate for triggering reviews of an institution’s financial aid eligibility. They also would have required institutions which had non-degree training programs to provide information to prospective students on the passing rates of recent graduates on state licensing exams and students’ completion and job-placement rates.

While the proposed rules did not require congressional action, the Reagan administration didn’t want the House to move forward with the Democrats’ legislation to limit the department’s authority and expand the Pell grant program. A week after Bennett stepped down, the Reagan administration and its new secretary of education, Lauro Cavazos, struck a deal: In exchange for House leaders dropping the bill, the Reagan administration would extend the comment period on the proposed regulations until February 1989,39 ensuring that their fate would be punted to the next administration—which turned out to be Cavazos and his successor as secretary of education, Lamar Alexander. Bill Bennett was disappointed. “We proposed some things [to Congress] with teeth,” Bennett told the Washington Post. “And they chickened out of any serious proposals.”40

Timeline of For-Profit Higher Education

Scroll through the below timeline to view the history of for-profit higher education.

Notes

- Bennett suggested students should easily be able to survive student aid reductions through “divestiture of some sorts—stereo divestiture, automobile divestiture, three-weeks-at-the-beach divestiture.” Edward B. Fiske, “Reagan’s Man for Education,” New York Times, December 22, 1985, https://drive.google.com/file/d/0B7aqIo3eYEUtSUxRajhESElEQkE/view?usp=sharing.

- Robert Rothman, “Bennett Asks Congress to Put Curbs on ‘Exploitative’ For-Profit Schools,” Education Week, February 17, 1988, http://www.edweek.org/ew/articles/1988/02/17/07450039.h07.html.

- The FTC rule was struck down in 1979 as the result of a lawsuit filed by the industry. See Katharine Gibbs School (Inc.) et al. v. F.T.C., 612 F. 2d 658, 1980, http://law.justia.com/cases/federal/appellate-courts/F2/612/658/410250/. The policy that placed a school on probation, with the possibility of termination, if more than 60 percent of students used federal loans (or if there was a 10 percent default rate or 20 percent withdrawal rate), appears to have been eliminated when the new Department of Education (previously part of the Health, Education and Welfare agency) issued regulations, 45 F.R. 86854, implementing the Higher Education Amendments of 1980.

- The 1978 Middle Income Student Assistance Act, Public Law 95-506, https://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/STATUTE-92/pdf/STATUTE-92-Pg2402.pdf (enacted during the Jimmy Carter administration), extended eligibility for student loans to for-profit colleges enrolling students without high school diplomas (so-called “ability to benefit” students). Aid to those without a high school diploma had been extended in 1976 (during the Ford administration) to students at public and nonprofit open-enrollment institutions.

- “In fiscal 1981, Department of Education officials said, 1,058 program reviews of profit-making vocational schools were conducted. By fiscal 1987 that had plummeted to 372.” Henry Weinstein, “Vocational Schools: Poor Being Taken for a ‘Bad Ride,” Los Angeles Times, June 16, 1988, http://articles.latimes.com/1988-06-16/news/mn-6833_1_vocational-school-students/5.

- Statement of William J. Bennett, in Quality in Higher Education, Hearing before the Subcommittee on Education, Arts, and the Humanities, Senate Committee on Labor and Human Resources, 99th Cong., 2nd Sess., S. Hrg. 99-732, Jan. 28, 1986, 16–17, https://drive.google.com/file/d/0B7aqIo3eYEUtelJSN1Y3aEEyejA/view?usp=sharing.

- Ibid., 16.

- Ibid., 44. The GAO investigation that Bennett referenced can be found at: Many Proprietary Schools Do Not Comply with Department of Education’s Pell Grant Program Requirements, Report by the Comptroller General of the United States, U.S. General Accounting Office, GAO/HRD-84-17, August 20, 1984, https://drive.google.com/file/d/0B7aqIo3eYEUtQklLT3lBWGxoQlk/view?usp=sharing.

- For a copy of Bennett’s November 4, 1987 statement announcing the new policy on federal student aid eligibility, his “Dear President” letter to college presidents on the proposal, and the Education Department Fact Sheet on the proposal, see Problems of Default in the Guaranteed Student Loan Program, Hearings before the Subcommittee on Education, Arts, and Humanities, Senate Committee on Labor and Human Resources, 100th Cong., 1st Sess., S. Hrg. 100-635, December 11 and 18, 1987. Bennett’s press statement is reproduced at pp. 94-99, his Dear President letter is reproduced at 87–88, and the Education Department’s Fact Sheet on the proposal is at 89–93, https://drive.google.com/a/tcf.org/file/d/0B7aqIo3eYEUtbENMVUxvVTYwaXM/view?usp=sharing.

- Ibid., 78.

- Robin Wilson, “For-Profit Trade Schools Defraud Students and Waste Federal Student-Aid Money, Bennett Charges in Scathing Report,” Chronicle of Higher Education, 34, no. 23, February 17, 1988, A1, A21.

- Quoted in the December 1987 Senate hearings, Problems of Default in the Guaranteed Student Loan Program, 122, https://drive.google.com/a/tcf.org/file/d/0B7aqIo3eYEUtbENMVUxvVTYwaXM/view?usp=sharing.

- Barbara Vobejda, “Bennett to Expel Schools From Loan Program if Too Many Students Default,” Washington Post, November 5, 1987, A21, https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/politics/1987/11/05/bennett-to-expel-schools-from-loan-program-if-too-many-students-default/c8bf978e-6158-4b41-8380-541a05d6e850/?utm_term=.52688fcba6ed.

- Quoted in the December 1987 hearings, Problems of Default in the Guaranteed Student Loan Program, 122, https://drive.google.com/a/tcf.org/file/d/0B7aqIo3eYEUtbENMVUxvVTYwaXM/view?usp=sharing.

- Problems of Default in the Guaranteed Student Loan Program, December 1987 Senate hearings, 13, https://drive.google.com/a/tcf.org/file/d/0B7aqIo3eYEUtbENMVUxvVTYwaXM/view?usp=sharing.

- Ibid., 78.

- Ibid., 79–80.

- Ibid., 80.

- Ibid., 82.

- Ibid., 83–84.

- Robin Wilson, “For-Profit Trade Schools Defraud Students and Waste Federal Student-Aid Money, Bennett Charges in Scathing Report,” Chronicle of Higher Education 34, no. 23, February 17, 1988, A21.

- Barbara Vobejda, “Bennett to Hill: Investigate Trade Schools,” Washington Post, February 10, 1988, A17. https://drive.google.com/file/d/0B7aqIo3eYEUtZ0RkcThfdWtDOHM/view?usp=sharing.

- Robert Rothman, “Bennett Asks Congress to Put Curb on ‘Exploitative’ For-Profit Schools,” Education Week, February 17, 1988, http://www.edweek.org/ew/articles/1988/02/17/07450039.h07.html.

- Ibid. While Bennett’s letter to Senator Kennedy noted the existence of a pattern of abuses in the proprietary industry, as well as the fact that proprietary schools “make up a disproportionate share of institutions with high rates of defaulted student loans,” he asserted that “the majority of private career schools seem to produce well-trained students who gets jobs in their field of training and have low default rates on their loans.” Joe Davidson, “Trade Schools Cited for Abuses in U.S. Reports,” Wall Street Journal, February 10, 1988, 33, https://drive.google.com/file/d/0B7aqIo3eYEUtc3hlV0N3bGxic1k/view?usp=sharing.

- Ezra Bowen, “Education: Taking Aim at Trade Schools,” Time, February 22, 1988, http://content.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,966765,00.html.

- Quoted in Margot A. Schenet, “Proprietary Schools: The Regulatory Structure,” Congressional Research Service, Report 90-424 EPW, August 31, 1990, CRS-17, https://drive.google.com/file/d/0B7aqIo3eYEUtTmxZMF9fa2JPb3c/view?usp=sharing.

- Gary Putka, “Rip-Off Tech: Shady Trade Schools Imperil Federal System of Loans to Students,” Wall Street Journal, March 28, 1989, A1, A12, https://drive.google.com/file/d/0B7aqIo3eYEUtVGIxVGZ1bXRKdFE/view?usp=sharing.

- Ibid.

- After the publication of the Pelavin Report, Senator Kennedy consistently maintained that it was essential that reforms be implemented to reduce student default rates at proprietary schools or the student loan program as a whole would lose public support. To cite one example, at an April 3, 1991, hearing on HEA reauthorization, Kennedy stated that “the challenge that we’re facing in doing a mathematical formula [to determine cutoff levels for eligibility for Title IV aid] [is] in some instances, there are good schools and yet they have a higher percentage of default. So we want to try to come up with a way of dealing with this problem. If we don’t, I think we’re in serious trouble both in terms of trying to continue the taxpayer support for the program and meeting our responsibilities in terms of education.” Oversight on Reauthorization of the Higher Education Act of 1965, Senate Committee on Labor and Human Resources, 102nd Cong., 1st Sess., S. Hrg. 102-1196, 26, https://drive.google.com/file/d/0B7aqIo3eYEUtT2k3QlVoRE1jWnM/view?usp=sharing.

- In 2016, Charles Kolb, a Bennett aide in the Reagan years, wrote that “There are future doctoral dissertations waiting to be written about how and why Democrats and Republicans reversed positions on the merits of the for-profit trade-school sector.” Charles Kolb, “Student Loan Defaults: Follow The Money?” Huffington Post, August 2, 2016, http://www.huffingtonpost.com/charles-kolb/student-loan-defaults-fol_b_11305040.html.

- Lee A. Daniels, “Policy on Student Loan Defaults Defended in Black College Forum,” New York Times, March 25, 1988, https://drive.google.com/file/d/0B7aqIo3eYEUtdzVnclUtelBiVGM/view?usp=sharing.

- Problems of Default in the Guaranteed Student Loan Program, December 1987 Senate hearings, 85, https://drive.google.com/a/tcf.org/file/d/0B7aqIo3eYEUtbENMVUxvVTYwaXM/view?usp=sharing.

- Gary Putka, “Troubling Statistics on Student-Loan Defaults Yield No Agreement on Explanation or Solution,” Wall Street Journal, March 15, 1988, 74, https://drive.google.com/file/d/0B7aqIo3eYEUtMWd4aVdtWW5CSHc/view?usp=sharing.

- Defaults in the Federal Guaranteed Student Loan Programs, Hearings before the Subcommittee on Postsecondary Education, House Committee on Education and Labor, June 14, 1988, https://drive.google.com/file/d/0B7aqIo3eYEUtdGcxN2k0V3d5a28/view?usp=sharing.

- Ibid., 20.

- Ibid., 35–36.

- Ibid., 34.

- Defaults in the Federal Guaranteed Student Loan Programs, Hearings before the Subcommittee on Postsecondary Education, House Committee on Education and Labor, June 14, 1988, 18, https://drive.google.com/file/d/0B7aqIo3eYEUtdGcxN2k0V3d5a28/view?usp=sharing.

- See Lee A. Daniels, “Education; Government Delays Tougher Loan Default Rules,” New York Times, September 28, 1988, https://drive.google.com/file/d/0B7aqIo3eYEUteWdWdElhMm5VLVU/view?usp=sharing, and Mark Walsh, “Cavazos Cautions Trade Schools Over Defaults,” Education Week, February 15, 1989, http://www.edweek.org/ew/articles/1989/02/15/08170045.h08.html?tkn=UOSFvRNp2ZNv%2BpvuJcSKynMTqi5AdpAqF46s.

- Kenneth J. Cooper and Michael Weisskopf, “Bennett Says Panel Report Impugned Him—Anonymously,” Washington Post, May 22, 1991, A19. https://drive.google.com/file/d/0B7aqIo3eYEUtVllYbXRHSl82TUE/view?usp=sharing.