One of the few ways in which Donald Trump’s presidential campaign addressed the issue of education was through a dramatic promise to create a $20 billion school choice program, including private school vouchers or similar initiatives that fund private school tuition.1 While the political future of the $20 billion proposal is unclear, finding ways to use public dollars to fund private school tuition appears to be a top priority for the administration. U.S. Secretary of Education Betsy DeVos has been an advocate for private school voucher programs throughout her career in philanthropy. And President Trump reinforced his intention to expand school choice in his first address to Congress in March 2017, calling for a bipartisan school choice bill that would enable student to attend a “public, private, charter, magnet, religious or home school.”2

There are multiple reasons to question the value of public programs that provide private school tuition—whether through private school vouchers or similar policies, such as tax credit scholarships and education savings accounts.3 Century Foundation senior fellow Richard D. Kahlenberg outlined some of these concerns in a recent report.4 The academic results of private school voucher programs thus far have been disappointing.5 Vouchers could divert limited funds from public schools, reduce students’ civil rights protections, and erode the separation of church and state. Furthermore, private school vouchers could increase school segregation.

Whether or not private school vouchers promote segregation is to some extent an empirical question, and yet, perhaps not surprisingly, opponents and supporters of private school vouchers tend to disagree on the answer. As part of DeVos’ confirmation process, Ranking Member Patty Murray from Washington State submitted a question asking DeVos whether she would support school choice plans that would increase school segregation. DeVos answered by rejecting the premise of the question: “I do not support programs that would lead to increased segregation. Empirical evidence finds school choice programs lead to more integrated schools than their public school counterparts.”6 Examining empirical research is crucial for understanding the implications of different types of school choice on school integration, but DeVos did not actually cite specific evidence in her answer, leaving policymakers and the public without data to evaluate her claim.

This report attempts to fill that gap by examining the evidence available on the effects of private school vouchers on school integration. Contrary to DeVos’ assertion, this report finds that the effects have been mixed, and that voucher programs on balance are more likely to increase school segregation than to decrease it or leave it at status quo. Although the demographics of students and schools create conditions under which vouchers could increase school integration in some places, there is little evidence that this has happened in practice. The best available data on the impact of school vouchers, tracking the movement of students in two different voucher programs, shows that voucher students by and large did not gain access to integrated schools as a result of the programs. Two-thirds of school transfers in one program and 90 percent of transfers in the other program increased segregation in private schools, public schools, or both sectors. Furthermore, data suggest that there is a strong risk that voucher programs will be used by white families to leave more diverse public schools for predominantly white private schools and by religious families to move to parochial private schools, increasing the separation of students by race/ethnicity and religious background.

This report proceeds in five parts. First, it presents a conceptual framework for understanding the conditions under which private school vouchers would promote integration versus segregation. Second, it reviews what descriptive studies on student and school demographics can tell us about the likely effects of private school vouchers on school integration. Third, it analyzes results from two studies that provide longitudinal data tracking the effects of private school vouchers on segregation in the public schools that students leave as well as the private schools that they attend. Fourth, it reviews the results of international studies on voucher programs. Finally, it provides policy recommendations based on these findings.

How Could Vouchers Affect School Integration?

By reviewing the body of research on demographics in voucher programs, this report finds that private school vouchers threaten to increase school segregation. But before delving into this evidence, it is helpful to establish a conceptual framework for the scenarios under which vouchers could affect school integration.

To begin with, it is important to recognize that vouchers have at best a very limited potential for increasing integration in public schools. It is very unlikely that a private school voucher policy on its own would create noticeably more integrated public schools. Vouchers enable students to leave public schools and move into private schools. It is rare for this one-way movement of students away from public schools to result in more integrated public schools, because a school would have to lose many students from an overrepresented group before that school’s overall demographics became much more integrated. Thus, even under the most ideal circumstances, vouchers are not an effective tool for integrating public schools.

Furthermore, there is a somewhat greater possibility that private school vouchers would increase segregation in public schools, because losing a relatively small number of students from an underrepresented group can make a school significantly more segregated than it was before. For example, if a school has ten black students and ninety white students, losing five white students through vouchers makes the school only slightly more integrated—now 89.5 percent white instead of 90 percent white. But if that same school loses five black students, the increase in segregation is much more noticeable, moving from 90 percent white to 95 percent white. Thus, from a purely mathematical perspective, vouchers have a greater potential for increasing segregation in public schools than for increasing integration.

From a purely mathematical perspective, vouchers have a greater potential for increasing segregation in public schools than for increasing integration.

Because they would bring in new students, voucher programs have the potential to significantly change the integration of schools in the private sector—for better, or worse. They could have a positive effect, if vouchers are increasing the overall enrollment at private schools that are already integrated, or bringing new students to schools in which their group is currently underrepresented, making the school more integrated as a result. Or they could have a negative effect, if vouchers bring new students to private schools where their group is already overrepresented, making those schools more segregated. Furthermore, a small positive effect in the private sector could be more than offset by a larger negative effect in the public sector.

Policy debates on private school vouchers must take into account an array of concerns, including evidence on academic results, public accountability, separation of church and state, and civil rights protections for students. However, this report focuses on the narrow question of the likely effect of private school vouchers on demographics in public and private schools. In this framework, vouchers can only have a net positive effect on school integration, across public and private schools, if both of these conditions are met:

- The move results in more students being educated in integrated settings.

- The move does not exacerbate segregation for other students.

There are a variety of ways to measure school integration, including using an absolute benchmark (such as tracking the number of schools where one group constitutes over 90 percent of the student body) or using a dissimilarity index to measure integration across a set of schools. For this conceptual framework, this report uses metropolitan area demographics as the benchmark for measuring an individual school’s level of integration, since private school vouchers typically provide the opportunity for students to attend schools across a region, rather than only within the boundaries of their school district. Figure 1 provides a visual display of the possible scenarios for the effect of school vouchers on school integration—coded as having positive, negative, or mixed results—based on the two criteria above.

|

Figure 1. The Effect of School Vouchers on School Integration |

||||

|

Students move to a private school where their group is… |

||||

| Underrepresented | In line with metropolitan area diversity | Overrepresented | ||

|

Students leave a public school where their group is…

|

Underrepresented | MIXED. Private school becomes more integrated, but public school becomes more segregated, and student may be in a more or less integrated setting as a result. | MIXED. Student gains access to an integrated private school, but public school becomes more segregated. | NEGATIVE. Public school and private school become more segregated. |

| In line with metropolitan area diversity | MIXED. Private school becomes more integrated, but student moves from an integrated school to a more segregated school. | MIXED. Student moves from an integrated public school to an integrated private school. | NEGATIVE. Private school becomes more segregated, and student moves from an integrated school to a more segregated school. | |

| Overrepresented | POSITIVE. Private school becomes more integrated without exacerbating segregation in public school. | POSITIVE. Student gains access to an integrated private school without exacerbating segregation in public school. | MIXED. Segregation in the public school is not exacerbated, but the private school becomes more segregated, and student may be in a more or less integrated setting as a result. | |

As Figure 1 shows, vouchers have, in theory, the potential to promote school integration in private schools when they allow students to move from public schools where their group is overrepresented to private schools that are already integrated or where their group is underrepresented. They have a negative or mixed effect on integration when students leave public schools that are already diverse or where their group is underrepresented, or when they move from a public school where their group is overrepresented to a private school where their group is also overrepresented.

Unfortunately, there is limited research on the demographics of voucher users and the schools they leave and enter that can be used to determine the effect of these programs on school segregation using the framework above. The research on segregation and charter schools is considerably more extensive, however, and has generally found that charter schools, on average, increase the segregation of students by both race and income.7 Some researchers have turned to this literature to draw conclusions about the effects on segregation of a wider array of school choice policies, including vouchers.8 However, while there are some similarities between charter schools and private school voucher programs, there are also enough substantive differences that we should not assume their effects on segregation are the same. Charter schools typically admit students via lottery, cannot charge tuition, and cannot screen students based on ability, audition, attendance record, or other factors (although some charter schools may in practice limit enrollment by “counseling out” students or creating enrollment processes that are not equally accessible to all students).9 Private schools accepting vouchers, however, can usually select their students using a variety of criteria, from academic requirements to interviews to screening for religious background. Most students in private schools pay tuition, and voucher students may also owe tuition, depending on the terms of the voucher program, if the cost of attendance exceeds the dollar amount of the voucher. These differences could well shape the types of students who use charter schools versus vouchers and the characteristics of the schools they leave and attend. Thus, this report limits sources to those that look specifically at private school vouchers or other programs that fund private school tuition.10

In the sections that follow, the report examines three types of studies of vouchers and what they can tell us about the likely effects on school segregation: descriptive studies, studies that track students, and international studies.

Descriptive Studies

A number of studies of the effects of vouchers on school segregation have compared the demographics of public schools with those of voucher-participating private schools, or analyzed the demographics of students using vouchers versus those of other public school students. These descriptive studies cannot provide a full picture of the effect that vouchers have on segregation because they do not track the movement of students from one school to another, and thus cannot determine whether vouchers are helping schools to become more or less integrated. Knowing that voucher users are more likely to be black, for example, does not tell you anything about the effects on integration, unless you know the demographics of the schools students are leaving and attending. Similarly, knowing that private schools as a whole have greater white enrollment than public schools does not tell you whether voucher programs would help to integrate those private schools or further segregate them, unless you know the demographics of students using vouchers. However, when we consider demographics trends for students and schools in tandem, these descriptive data are helpful in gauging the likelihood that vouchers will promote integration or exacerbate segregation.

Below, this report reviews the available data on the demographics of voucher users, the public schools they leave, and the private schools they attend, across four different characteristics: race/ethnicity, socioeconomic status (SES), religion, and parental engagement. The descriptive studies of school voucher programs outline a number of ways that vouchers may affect school integration. For example, there is a greater likelihood of racial integration in voucher programs that are used mostly by black, Latino, or American Indian students than in programs that are used mostly by white students. Also, the chance of socioeconomic segregation increases when programs are universal or have high income caps. And there is a strong risk of increasing segregation in terms of religion and parental engagement across all voucher programs.

Race and Ethnicity

The research on racial and ethnic demographics of voucher users and the schools they leave versus attend suggests several possible patterns that affect school segregation, depending largely on the race/ethnicity of the students participating in the program.

The Effect on Public Schools

One of the prerequisites for vouchers having a positive effect on racial integration is for voucher programs to draw students from public schools where their race/ethnicity is currently overrepresented. There is some evidence to suggest that black students may be likely to use vouchers in this way, to leave schools where racial minorities are overrepresented. A 2002 study of a national privately funded school voucher program found that 49 percent of voucher applicants were black, compared to just 26 percent of eligible families.11 Among the black students who applied for vouchers, 47 percent attended schools where at least 90 percent of students were racial minorities, whereas only 32 percent of eligible black students attended schools with that demographic profile.12 (Although this is not a perfect measure of whether or not a school is integrated relative to the area in which it is located, in most places, a school in which at least 90 percent of students are nonwhite will constitute an overrepresentation of nonwhite students in that school.)

On the other hand, vouchers will lead to negative or mixed results for racial integration when students leave public schools that are integrated or where their race/ethnicity is underrepresented, and there is evidence that white students may be likely to follow this pattern. A 2010 study of California residents’ support for a universal private school voucher program (which would have been available to all children, regardless of income or which school they currently attended) found that white families with children were more likely to support the program when their children attended school with a higher proportion of nonwhite students, whereas nonwhite households and households without children did not show the same pattern.13 Studies of private school enrollment generally (not restricted to voucher use) have also found that white families are more likely to attend private school when there is a greater percentage of black students enrolled in the local public schools.14

The Effect on Private Schools

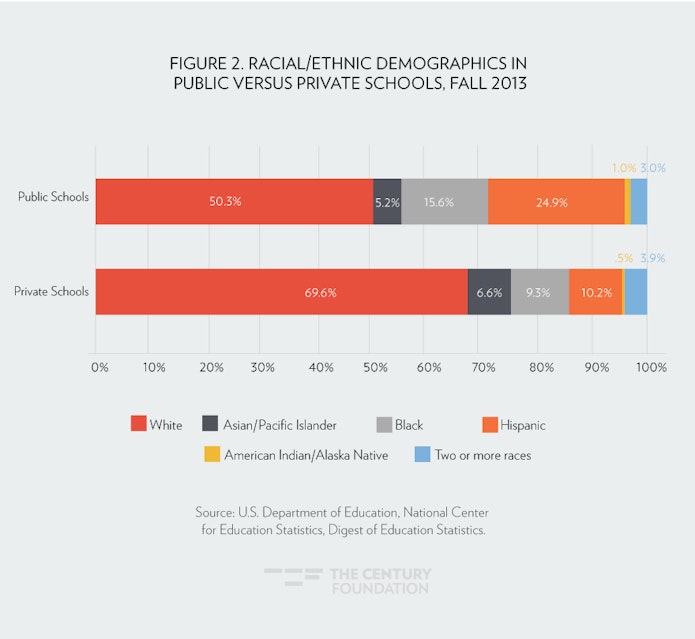

In order to promote racial integration in private schools, voucher programs need to facilitate the movement of students to private schools where their race/ethnicity is underrepresented. Nationwide, black, Latino, and American Indian students are underrepresented in private schools. As of fall 2013, 70 percent of students in private schools were white, compared to 50 percent of public school students (see figure 2).15

Voucher programs that enroll mostly black, Latino, or American Indian students might therefore bring students to private schools where their race/ethnicity is underrepresented. For example, in the Opportunity Scholarship Program in Washington, D.C., which offers private school vouchers to low-income families, voucher users are mostly black, and private schools on average have an underrepresentation of nonwhite students. Data from a study of the first year of the program found that 94 percent of students using vouchers were black, and a majority (52.6 percent) of students using the vouchers attended private schools that were relatively integrated (schools with roughly 50–70 percent nonwhite students, based on a metro area in which roughly 60 percent of students are nonwhite) or had an underrepresentation of nonwhite students (schools with less than 50 percent nonwhite students).16 As is discussed later in this report, however, data from voucher programs in Louisiana and Milwaukee show that these programs did not have the same effect of encouraging integration in private schools, despite also being used mostly by black students.

Conversely, programs in which a majority of voucher users are white could be particularly susceptible to increasing segregation by facilitating the movement of white students to disproportionately white private schools. Indiana’s Choice Scholarship Program, for example, is open to students from families earning up to 150 percent of the amount to qualify for the federal free or reduced-price lunch program (equal to 278 percent of the federal poverty line) and is one of the largest voucher programs in the country. As of 2015–16, 61 percent of students participating in the program were white.17 Programs like Indiana’s that have broader eligibility criteria may be more likely to be used by a greater proportion of white students, as illustrated by the difference between demographics in two voucher programs in Ohio. EdChoice, Ohio’s original voucher plan, is open only to students enrolled in low-performing public schools, and only 21.4 percent of voucher users were white in 2014–15. However, the EdChoice expansion program is open to low-income students who are not enrolled in a low-performing public school, and 64.3 percent of participating students were white.18

When weighing the likelihood that the disproportionate whiteness of private schools would create opportunities for increasing or decreasing segregation, it is also important to consider the history of private schools that led to the concentration of white students. Economic factors partly explain this pattern, as white and Asian families have higher median incomes and are more likely to be able to afford private school than black or Latino families.19 If income were the only factor, private school vouchers might be an effective means to bring more racial diversity to these private schools. But the data suggest a more complicated story, as white students are also more likely to attend private schools than black or Latino students from families with the same income.20

In some cases, especially in the South, predominantly white private schools were created as the result of deliberate efforts by white Christian parents to start private schools as an alternative to public schools, which were being integrated at the time. Many “segregation academies” refused admission to nonwhite students when they were created, and still remain de facto segregated.21 Discriminatory admission practices and school policies continue today. Most but not all states with voucher programs specify that participating schools cannot discriminate based on race or national origin. Only a couple of states prohibit discrimination based on religion or gender, and none have prohibitions against discrimination based on sexual orientation.22 As my colleague Kimberly Quick has documented, some private schools receiving public funds through vouchers in North Carolina, for example, restrict enrollment to Christian students, have policies enforcing gender norms and rejecting admission of LGBT students, or have discriminatory dress codes banning head scarves or limiting the size of afros.23 Putting aside the legal and ethical questions of sending public funds to private schools with these discriminatory policies, the history and current practices of some predominantly white private schools may make it unlikely that many students of color using vouchers would choose to attend or be admitted by these schools.

In summary, the racial/ethnic demographic data on voucher users and the public and private schools affected suggest that there is the theoretical possibility for vouchers to promote integration, likely by facilitating the movement of black, Latino, or American Indian students from public schools where their group is overrepresented to private schools that are diverse or where their group is underrepresented. However, the data also suggest there is a risk for private school vouchers to increase school segregation, in particular by facilitating the movement of white students to disproportionately white private schools.

Socioeconomic Status

Research suggests that voucher programs tend to facilitate the concentration of higher-SES students in private schools, unless programs are means-tested and designed to limit eligibility to low-SES students. Below, this report considers the data on three components of socioeconomic status: parental education, family structure, and income.

Voucher programs may increase the concentration of parents with higher levels of education in private schools. Nationwide, students whose parents have higher levels of education are more likely to attend private school.24 Likewise, participants in private school voucher programs typically have more educated parents than their peers who choose not to participate. Studies of a national privately funded voucher program and Milwaukee’s voucher program found that students who apply to voucher programs are more likely than similar students who did not apply to have higher levels of parental education.25 Similarly, a 2010 study of a private school scholarship program in North Carolina found that those students who applied for and used the voucher were more likely than those who applied but did not end up using the voucher to have a mother who had attended at least some college.26

Data point to a similar pattern in terms of family structure. Studies have generally found that students who use private school vouchers are more likely than eligible students who do not use vouchers to live in a two-parent household.27 This echoes a broader pattern in private versus public school enrollment, with 80 percent of private school families having married parents, compared to just 64 percent of public school families.28 Therefore, private school voucher usage may also increase the concentration of students with married parents in private schools.

The effect of private school vouchers on segregation by income is largely determined by the eligibility criteria of the program. Most voucher programs in the country are means-tested, limiting participation to low-income families.29 Means-tested voucher programs have the potential to increase socioeconomic integration in private schools by shifting low-income students into private schools that have higher average income. In 2012, private school parents were almost twice as likely as public school parents to come from families earning more than $75,000 a year (60 percent vs. 32 percent). Conversely, only 7 percent of private school parents made less than $20,000 per year, compared to 15 percent of public school parents.30

When voucher programs have universal eligibility, however, or extend the income requirements to include more middle-class families, vouchers may instead increase stratification by income in public and private schools alike.

When voucher programs have universal eligibility, however, or extend the income requirements to include more middle-class families, vouchers may instead increase stratification by income in public and private schools alike. Some voucher programs that at the start targeted low-income families have gradually increased eligibility to include higher-income families. Milwaukee’s voucher program, for example, started in 1990 with an income cap of 175 percent of the federal poverty line, but today the program is open to new students in families earning up to 300 percent of the federal poverty line ($72,900 for a single-parent family of four), and after their initial year in the program, students do not have to meet the 300 percent of poverty income limit.31

Furthermore, even within means-tested voucher programs, the potential to promote the movement of low-income students to higher-income schools may be tempered by the specific terms of the program. In many programs, vouchers cover only a certain dollar amount toward private school tuition, and families are responsible for paying the remaining tuition if a school’s charges are greater than the amount covered. This extra financial liability may limit participation for some low-income families.32

Religion

With respect to religious diversity, the data suggest religiously observant students in public schools may be likely to use vouchers to switch to religious schools. A 2002 study of a national voucher program found that voucher users were almost twice as likely as nonparticipating eligible students to report attending church at least once a week (66 percent versus 38 percent).33 A study of Cleveland’s private school voucher program found similar results.34 Nationwide, nearly 80 percent of all private school students in the United States attend religious schools,35 and available data from voucher programs shows that in many cases, a majority of voucher users also attend religious schools. A 1999 study of voucher users in Cleveland found that 96.6 percent of students using vouchers attended religiously affiliated private schools.36 And in Washington, D.C.’s voucher program, as of 2011–12, 64 percent of private schools participating in the program were religiously affiliated.37

Parental Engagement

One of the concerns about school choice—whether private school vouchers or public school choice programs such as charter schools or magnet schools—is that choice programs will “skim” the most motivated families from public schools and move students into choice schools in which highly engaged families are overrepresented.38 The issue of skimming motivated parents is difficult to study, because it often comes down selection bias: the unmeasured characteristics that separate a student who applies for the program from a demographically similar student who does not apply. However, a few studies of voucher programs have attempted to capture information on families’ educational attitudes and behaviors in order to to look at this question of skimming. These studies have found that parents participating in voucher programs are indeed more engaged in their children’s education than nonparticipating eligible parents.

A study of a national voucher program found that voucher applicants reported attending more parent-teacher conferences per year than eligible non-applicants and were more likely to have volunteered in their child’s school.39 Similarly, a study of the Milwaukee voucher program found that voucher users reported much higher parental engagement across all measures—frequency of contacting the school, involvement in school organizations, and involvement in educational activities with their children—than did low-income public school families who did not use vouchers.40 In a study of a North Carolina private school scholarship program, voucher users were also more likely to come from two-parent families in which the mother worked part-time or was not working, whereas those who applied for vouchers but declined to use them were more likely to come from single-parent families in which the mother works full-time. These results suggest that parents’ ability to contribute time to their child’s education may also affect their likelihood to participate in voucher programs.41 Finally, research shows that parents who applied for voucher programs were less likely to be satisfied with their child’s current school across a variety of measures: academic quality, safety, location, discipline, and teaching of values.42 This dissatisfaction is likely a measure of the schools attended as well as the parents’ attitudes and expectations.

The movement of more motivated parents from public schools to private schools likely serves to increase the concentration of highly involved parents in private schools. Nationwide, parents in private schools are more likely than parents in public schools to attend a PTA meeting, parent–teacher conference, or school or class event; to participate in school fundraising efforts; or to volunteer or serve on a school committee.43

Studies that Track Students Using Vouchers

To shed further light on the question of vouchers’ effects on school integration, this section of the report examines data from two studies that have tracked U.S. students using vouchers from the public schools they leave to the private schools they attend, analyzing data on student and school demographics. These two studies provide a clearer picture of the effects of voucher programs on school integration than the descriptive studies examined in the previous section of this report; however, the studies only look at two specific programs and are thus somewhat limited in their ability to speak to national trends. The first is a 2017 study on the Louisiana Scholarship Program, and the second is a 2010 study on the Milwaukee Parental Choice Program. In both cases, programs were used primarily by black students and generally did not exacerbate segregation in public schools; however, students using vouchers did not gain access to integrated private schools, and segregation in private schools actually increased. Two-thirds of school transfers in the Louisiana Scholarship Program and 90 percent of transfers in the Milwaukee Parental Choice Program increased segregation in private schools, public schools, or both sectors.

The Louisiana Scholarship Program

A 2017 study in Education and Urban Society, “The Impact of Targeted School Vouchers on Racial Stratification in Louisiana Schools,” examines the school-moving patterns of students participating in the Louisiana Scholarship Program, a statewide voucher program that is open to low-income students attending low-performing public schools.44 As of 2017, the program is open to families earning up to 250 percent of the federal poverty line whose child is enrolled in or zoned for a public school with a C, D, or F grade in the state’s A to F accountability rating system.45 The program was started as a citywide pilot in New Orleans in 2008 and expanded throughout the state in 2012. The authors examine data for students who used vouchers in 2012–13, the first year of statewide operation, during which the program provided vouchers to roughly 5,000 students.

The demographics of students and schools in the program exhibit some of the conditions that could lay the groundwork for a voucher program encouraging integration. A majority (80 percent) of voucher users were black, 13 percent were white, 4 percent Latino, and 3 percent other.46 Private schools across the state were also less likely than public schools (14 percent vs. 26 percent) to have “hyper-segregated” enrollment of 90 percent or more of students from a single racial or ethnic group.47

Examining individual student transfers, the authors found that 82 percent of voucher users left public schools where their race was overrepresented relative to the school-aged population in the community, which they considered to be transfers that reduced segregation in the public schools. However, 55 percent of voucher uses entered private schools where their race was overrepresented relative to the community, which the authors considered as transfers that increased segregation in the private schools. Thus, the authors concluded, “Overall, we find large, positive reductions in racial stratification in public schools that are consistent across our samples and small increases in racial stratification in private schools that are not consistent across our samples as a result of this school voucher program.”48

This summary of the findings is misleading in two respects. First, although a majority of voucher users left public schools where their race was overrepresented, this pattern does not equate to “large, positive reductions in racial stratification in public schools.” As discussed earlier, the loss of a few students from an overrepresented group has a very small effect on the overall demographics of a school, moving that school only slightly closer to being integrated in line with community demographics. Unless the voucher users were coming from a small number of public schools, the effect of the voucher transfers on public schools would better be described as widespread but slight reductions in racial stratification in the public schools that voucher students left.

Second, by reporting the effects of the voucher transfers on public schools and private schools separately, the analysis dodges the question of what percentage of moves had an overall positive effect on school integration across both sectors. Using data that the authors provide in a table in the appendix, it is possible to examine the effect of the voucher transfers on integration using a modified schematic based on the conceptual model laid out at the beginning of this report.

Figure 3 presents the data from the Louisiana Scholarship Program study across four categories based on whether the student’s racial group was overrepresented or underrepresented at the public school the student left and private school the student attended. (Unlike the conceptual model laid out at the beginning of this report, this table does not include a category for integrated schools in which the student’s group is represented within a certain range of the average for the community. That is because the data from this study did not use such a category. If that category were available, it would provide a more nuanced view of the effect of these transfers on integration, since some of the schools in which a student’s group is classified under the binary underrepresented/overrepresented measure may actually fall close to the community average and would be better described as integrated.)

As Figure 3 shows, about a third (34 percent) of the voucher transfers had a positive effect on school integration by moving students from public schools where their race was overrepresented to private schools where their race was underrepresented. However, two-thirds of the transfers had negative or mixed effects, increasing segregation in one or both sectors. In 9 percent of transfers, students moved from a public school where their group was underrepresented to a private school where their race was overrepresented, having a negative effect on integration in both sectors. Another 9 percent of students moved from a public school where their race was underrepresented to a private school where their race was also underrepresented. Nearly half (48 percent) of all transfers involved students moving from a public school where their race was overrepresented to a private school where their race was also overrepresented, resulting in slightly reduced segregation in the public schools but slightly increased segregation in the private schools.

|

Figure 3. Effect of Louisiana Scholarship Program Transfers on School Integration |

|||

| Students move to a private school where their group is… | |||

| Underrepresented | Overrepresented | ||

|

Students leave a public school where their group is…

|

Underrepresented | 9 percent: MIXED EFFECT.

+ 5 percent moved from a public school where their race was underrepresented to a private school where their race was even more underrepresented + 4 percent moved from a public school where their race was underrepresented to a private school where their race was still underrepresented but less so |

9 percent: NEGATIVE EFFECT. |

| Overrepresented | 34 percent: POSITIVE EFFECT. | 48 percent: MIXED EFFECT.

+ 16 percent moved from a public school where their race was overrepresented to a private school where their race was even more overrepresented + 32 percent moved from a public school where their race was overrepresented to a private school where their race was less overrepresented |

|

| Source: Anna J. Egalite, Jonathan N. Mills, and Patrick J. Wolf, “The Impact of Targeted School Vouchers on Racial Stratification in Louisiana Schools,” Education and Urban Society 49, no. 3 (January 2017): 292, Table A2. | |||

Looking at the data on student transfers by race sheds further light on the patterns of voucher usage. The vast majority of black students (92 percent) left public schools where black students were overrepresented, and most (55 percent) attended private schools where black students were also overrepresented, showing a mixed effect on integration. By contrast, three-quarters (76 percent) of white students using vouchers left public schools where white students were underrepresented, and roughly the same proportion (72 percent) attended private schools where white students were overrepresented, showing a negative effect on integration. Latino students (who made up just 4 percent of voucher users) followed a different pattern, with 56 percent of students leaving public schools where Latino students were overrepresented and nearly all (96 percent) attending private schools where Latino students were underrepresented, showing a positive effect on integration.49

The Louisiana Scholarship Program had a mixed effect on integration. Only a third of all voucher transfers in the Louisiana Scholarship Program resulted in more integrated public and private schools, while the other two-thirds of transfers exacerbated segregation in one or both sectors. Furthermore, the results by student race confirm patterns noted in demographic studies of voucher users and private school attendance: that black students typically used vouchers to leave public schools where their race was overrepresented, but white students tended to leave public schools where their race was underrepresented.

The Milwaukee Parental Choice Program

The other study of vouchers and segregation that tracks U.S. student transfers is a 2010 report on the Milwaukee Parental Choice Program by University of Arkansas researchers. The Milwaukee Parental Choice Program is the oldest school voucher program in the country, started in 1990–91. During 2008–09, the most recent year studied in the report, the program was open to students from families earning up to 220 percent of the poverty line, and today the program is open to families earning up to 300 percent of poverty.50 In 2008–09, the sample of students using vouchers analyzed in the study was 80.3 percent black, 13.9 percent Latino, 1.6 percent Asian, and 3.3 percent white.51

The authors analyzed the school transfers of voucher users based on student and school demographics and found clear patterns. Over 95 percent of students in the sample using school vouchers in 2008–09 left public schools where their race was overrepresented,52 and 94.2 percent of the students using vouchers went to private schools where their race was still overrepresented.53 Although the researchers did not break down this analysis to put transfers into discrete categories based on the interaction of the demographics of the public school left and the private school attended, the patterns were so consistent that one can conclude that the great majority of students using vouchers—at least 89.6 percent—moved from a public school where their race was overrepresented to a private school where their race was still overrepresented, increasing segregation in private schools and resulting in a mixed effect on school integration overall.

As with the study of the Louisiana Scholarship Program, this study coded all schools in its analysis of voucher transfers as having an underrepresentation or overrepresentation of each racial group, rather than including a third category for integrated schools within a range of the community average demographics for each group. It is possible for a binary analysis like this to mask the fact that some students may be leaving or attending schools that are actually more integrated, in which case we would assess the impact on school integration differently. However, the authors did provide such an analysis separately, which suggests that very few of the public or voucher-participating private schools involved would meet the definition of an integrated school. Only 11.2 percent of students using vouchers in 2008–09 left public schools in which the percentage of white students fell within 25 percentage points above or below the metro area average for enrollment of white students (60.1 percent), and only 17.5 percent then attended private schools falling within that range. In fact, a majority of both public schools (62.3 percent) and voucher-participating private schools (68.4 percent) in Milwaukee have enrollment that is either over 90 percent white or over 90 percent nonwhite.54

In a landscape in which both the public schools and the private schools have high levels of racial segregation, Milwaukee’s private school voucher program did little to promote greater integration for students. Almost all of the students in the program were leaving public schools where their race was overrepresented, so the program generally did not exacerbate segregation in the public schools. However, those students by and large did not gain access to integrated schools as a result, but rather attended private schools in which their race was still overrepresented.

International Studies

The final type of study examined in this report is international studies of voucher programs or similar educational initiatives. The many differences in education systems and student demographics between the United States and other countries limit the extent to which these studies can predict the effects of U.S. voucher programs. Nevertheless, they provide helpful examples for understanding the possible effects of large-scale voucher programs that have operated for a number of years. By and large, voucher programs in other countries have been found to increase school segregation:

- Chile has had a universal school voucher program since 1981.55 A 2013 study of segregation in Chilean schools found that school segregation by SES increased in Chile as market-based reforms grew, and private schools, including those receiving vouchers, were more segregated than public schools for both low-SES students and high-SES students.56

- Sweden also has a universal voucher system, instituted in the early 1990s.57 A 2015 study on Swedish schools found that the use of private school vouchers was associated with increased segregation of immigrant versus native Swedish students.58

- In the Netherlands, only 30 percent of students attend government-run schools, whereas 70 percent of students attend schools that are publicly funded but privately operated, including both religious and nonreligious schools. A 2009 study of the Netherlands found that this marketplace approach to education has contributed to high and growing levels of segregation of students by educational disadvantage.59

- New Zealand moved to a system of full parental choice in 1991, allowing all families to choose from among government-operated or private schools, including religious schools. A 2001 analysis found that, in the years after this policy was enacted, students of European descent tended to leave schools with lower SES for schools with much higher SES, while Maori and Pacific Island students, who are racial minorities in the country, became increasingly concentrated in low-SES schools.60

Thus far, voucher programs in the United States enroll only 400,000 students nationwide, but the experiences in Chile, Sweden, the Netherlands, and New Zealand offer a window into how an expanded program might affect school segregation.61

Policy Recommendations

The demographics of students who use vouchers, the public schools they leave, and the private schools they attend make it theoretically possible for vouchers to promote integration in some places, particularly when vouchers are used mostly by students of color. But the two studies that offer data tracking student transfers facilitated by vouchers, examining a statewide voucher program in Louisiana and a citywide program in Milwaukee, show that in neither case did vouchers succeed in giving many participating students—the overwhelming majority of whom were black—access to integrated schools. Furthermore, the demographic data on voucher usage and private school attendance also reveal a real risk that vouchers will be used by white families to move to whiter schools, and by religious students to move to religious schools. Finally, the results of international studies suggest that, when other countries have adopted vouchers or similar programs, both socioeconomic and racial/ethnic segregation increased.

If policymakers want to increase school choice and integration at the same time, first and foremost they should support forms of school choice that have integration built into the design of their program. Federal, state, and local policymakers should:

- Expand magnet schools. The term “magnet school” is commonly used to describe a variety of different types of schools with educational themes and choice-based admission that draw students from across a geographic area. While some of these schools have selective admissions that screen students based on academic criteria or auditions, many more magnet schools are part of a tradition designed to use the magnet school model to enroll a diverse group of students and help desegregate schools. In Greater Hartford, Connecticut, for example, an extensive system of interdistrict magnet schools draws students from Hartford City, where the population is 16 percent white, 38 percent black, and 44 percent Latino, and the surrounding counties, where the population is roughly 65 percent white, creating racially and socioeconomically diverse schools as a result. The overall enrollment in the area’s magnet schools is close to one-third white, one-third black, and one-third Latino.62 The federal Magnet Schools Assistance Program (MSAP) provides grants to support the creation of magnet schools, with a priority of schools that promote socioeconomic and racial diversity. However, federal funding for MSAP is currently just $96 million, compared, for example, to $333 million devoted to charter school grants. The federal government should increase funding for the MSAP in order to create more opportunities for choice-based school integration.63

- Support the creation of intentionally diverse charter schools. When they are designed with diversity in mind, charter schools can function much like magnet schools, bringing together a diverse group of students from a broader geographic area. A growing number of charter schools have made socioeconomic and racial diversity of the student body part of their mission and have implemented admissions policies and recruitment strategies to reach their diversity goals. Blackstone Valley Prep Mayoral Academy in Rhode Island, for example, enrolls students from two low-income urban and two high-income suburban school districts, creating a socioeconomically and racially diverse network of schools as a result.64 Valor Collegiate Academy in Nashville, Tennessee, developed a multifaceted diversity plan with goals based on the socioeconomic, racial, and ethnic diversity of southeast Nashville and implemented recruitment strategies to reach diverse families.65 And DSST Public Schools in Denver, Colorado, a charter school network, reserves 40 percent of seats at its flagship campus for low-income students to ensure socioeconomic diversity.66

The federal government should continue to strengthen competitive priorities in charter school grant programs for applicants that indicate socioeconomic and racial diversity as a goal, and should revise guidance on the use of weighted lotteries to allow more charter schools across a variety of states to use federal funds while implementing lotteries that promote diversity. States should amend charter school laws to specifically allow weighted lotteries that promote diversity and to provide transportation funding for students attending charter schools. Charter school authorizers should also hold schools accountable for presenting diversity plans and encourage applicant schools to create plans that support integration when possible.67

Furthermore, where public programs to fund private school tuition are in place—whether school vouchers, tax-credit scholarships, or education savings accounts—policymakers should ensure that these programs are designed with safeguards to prevent them from increasing school segregation.68 Policymakers should:

- Allow vouchers to be used only in private schools that meet a minimum threshold of diversity. Voucher programs should be designed to require participating schools to meet diversity guidelines established based on the demographics of the broader community being served. These guidelines could be based on race-neutral factors, such as socioeconomic status and geography, and in some cases, as legally appropriate, might also include race-based factors as defined either by neighborhood characteristics or student demographics.69

- Do not allow vouchers to be used in private schools with discriminatory policies. Private schools with admissions policies or conduct codes that discriminate against students based on race, ethnicity, religion, sexual orientation, gender identity or expression, or disability should not be allowed to participate in voucher programs.

- Use targeted rather than universal programs to restrict eligibility to low-income students in low-performing public schools. Data from existing voucher programs suggest that targeting low-income students and/or students in low-performing public schools may make programs less likely to exacerbate segregation in public or private schools.

- Require voucher programs to record longitudinal data tracking student transfers due to vouchers—including information on the demographics of students, the public schools they leave, and the private schools they attend—and make this data publicly available. Data matching students and schools is essential to understand the impact that programs have on integration in both public and private schools. In addition to data on race, programs should track and report the socioeconomic status, English Language Learner status, and special education status of students.

Conclusion

Decades of research affirm the public interest in creating racially and socioeconomically diverse schools, and yet America’s schools are in many ways more segregated now than they were in the 1970s.70 As a nation, we need to invest in educational solutions that give more students access to integrated schools. But data suggest that private school vouchers are not an effective tool for reaching this goal. To the contrary, private school vouchers threaten to exacerbate the high levels of segregation that already exist in both public and private schools.

Still, promoting integration need not mean abandoning the goal of expanding families’ educational options. In fact, school choice can be an effective tool for promoting integration—bringing together families from diverse backgrounds and different neighborhoods—when diversity is built into the goal and design of a program, as it has been in some magnet schools and intentionally diverse charter schools. Too many families today are forced to choose between segregated district schools, segregated charter schools, or segregated private schools. One of the most meaningful ways in which we could expand school choice is to ensure that all students have the option of attending a racially and socioeconomically diverse school.

Notes

- Caitlin Emma, “Trump Unveils $20B School Choice Proposal,” Politico, September 8, 2016, http://www.politico.com/story/2016/09/donald-trump-school-choice-proposal-227915.

- Yamiche Alcindor, “Trump’s Call for School Voucher Is a Return to a Campaign Pledge,” New York Times, March 1, 2017, https://www.nytimes.com/2017/03/01/us/politics/trump-school-vouchers-campaign-pledge.html.

- For an explanation of the different types of public programs that provide private school tuition, see Arianna Prothero, “What the difference between Vouchers and Education Savings Accounts?” Education Week, June 9, 2015, http://blogs.edweek.org/edweek/charterschoice/2015/06/school_vouchers_education_savings_accounts_difference_between.html.

- Richard D. Kahlenberg, “America Needs Public School Choice, Not Private School Vouchers,” The Century Foundation, March 2, 2017, https://tcf.org/content/report/america-needs-public-school-choice-not-private-school-vouchers/.

- Kevin Carey, “Dismal Voucher Results Surprise Researchers as DeVos Era Begins,” TheUpshot, New York Times, February 23, 2017, https://www.nytimes.com/2017/02/23/upshot/dismal-results-from-vouchers-surprise-researchers-as-devos-era-begins.html; and Arianna Prothero, “What Are School Vouchers and How Do they Work?” Education Week, January 26, 2017, https://www.edweek.org/ew/issues/vouchers/.

- Betsy DeVos, responses to Questions for the Record submitted by Ranking Member Murray, U.S. Senate Committee on Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions, January 2017, http://blogs.edweek.org/edweek/campaign-k-12/Murray’s%20QFRs%20(003).pdf.

- Richard D. Kahlenberg and Halley Potter, A Smarter Charter: Finding What Works for Charter Schools and Public Education (New York: Teachers College Press, 2014), 45–67.

- See, e.g., William J. Mathis and Kevin G. Welner, Do Choice Policies Segregate Schools? (Boulder, CO: National Education Policy Center, March 2016), http://nepc.colorado.edu/files/publications/Mathis%20RBOPM-3%20Choice%20Segregation.pdf.

- See Kahlenberg and Potter, A Smarter Charter.

- For a summary of research on different types of school choice programs, including vouchers, intradistrict magnet schools, interdistrict plans, charter schools, and home schooling, see Roslyn Arlin Mickelson, Martha Bottia, and Stephanie Southworth, “School Choice and Segregation by Race, Class, and Achievement,” Education Policy Research Unit, March 2008, http://nepc.colorado.edu/publication/school-choice-and-segregation-race-class-and-achievement.

- Paul E. Peterson, David E. Campbell, and Martin R. West, “Who Chooses? Who Uses? Participation in a National School Voucher Program,” in Choice with Equity: An Assessment by the Koret Task Force on K–12 Education, ed. Paul T. Hill (Stanford, CA: Hoover Institution Press, 2002), 60, http://www.hoover.org/sites/default/files/uploads/documents/0817938923_51.pdf.

- Ibid., 66, table 5.

- Eric J. Brunner, Jennifer Imazeki, and Stephen L. Ross, “Universal Vouchers and Racial and Ethnic Segregation,” The Review of Economics and Statistics 92, no. 4 (November 2010): 926.

- Sean F. Reardon and John T. Yun, “Private Schools and Segregation,” in Richard D. Kahlenberg (ed.), Public School Choice vs. Private School Vouchers (Century Foundation Press, 2003), 79; and Robert W. Fairlie, “Racial Segregation and the Private/Public School Choice,” Research Publication Series, National Center for the Study of Privatization in Education, Teachers College, Columbia University (February 2006), 5, http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.584.2616&rep=rep1&type=pdf.

- U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics, Digest of Education Statistics, 2015 Tables and Figures, Tables 205.40 and 203.60, https://nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/d15/tables/dt15_205.40.asp?current=yes and https://nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/d15/tables/dt15_203.60.asp?current=yes.

- Jay P. Greene and Marcus A. Winters, “An Evaluation of the Effect of DC’s Voucher Program on Public School Achievement and Racial Integration after One Year,” Catholic Education: A Journal of Inquiry and Practice 11, no. 1 (September 2007): 98, http://www.uark.edu/ua/der/People/Greene/An%20Evaluation%20of%20the%20Effect%20of%20DC%20Voucher%20on%20Achievement%20and%20Integration.pdf.

- Indiana Department of Education, Office of School Finance, Choice Scholarship Program Annual Report: Participation and Payment Data (April 2016), 11, http://www.doe.in.gov/sites/default/files/news/2015-2016-choice-scholarship-program-report-final-april2016.pdf; and Lesli A. Maxwell and Arianna Prothero, “Why Trump’s Plan for a Massive School Voucher Program Might Not Work,” Education Week, November 28, 2016, http://blogs.edweek.org/edweek/charterschoice/2016/11/trump_voucher_primer_and_reality_check.html?r=1480607129.

- Bill Bush, “White Students Disproportionately Use Ohio School Voucher Program,” The Columbus Dispatch, August 28, 2016, http://www.dispatch.com/content/stories/local/2016/08/28/white-students-disproportionately-use-ohio-school-voucher-program.html.

- Bernadette D. Proctor, Jessica L. Semega, and Melissa A. Kollar, Income and Poverty in the United States: 2015, Current Population Reports, U.S. Census Bureau, September 2016, 14, table 1, https://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/publications/2016/demo/p60-256.pdf.

- Reardon and Yun, “Private Schools and Segregation,” 76. See also Robert W. Fairlie, “Racial Segregation and the Private/Public School Choice.” While these studies control for income, they do not control for family wealth. There are large wealth gaps between black and Latino families, who have much lower median wealth, and white and Asian families, who have greater median wealth. Wealth could thus be an additional economic factor that contributes to the different rates of private school attendance for families of different racial/ethnic backgrounds.

- Sarah Carr, “In Southern Towns, ‘Segregation Academies’ Are Still Going Strong,” The Atlantic, December 13, 2012, http://www.theatlantic.com/national/archive/2012/12/in-southern-towns-segregation-academies-are-still-going-strong/266207/.

- Matt Barnum, “Some Private Schools that May Benefit from Trump’s Voucher Plan Are Weak on Discrimination Rules,” The 74 Million, January 18, 2017, https://www.the74million.org/article/some-private-schools-that-may-benefit-from-trumps-voucher-plan-are-weak-on-discrimination-rules.

- Kimberly Quick, “Second-Class Students: When Vouchers Exclude,” The Century Foundation, January 11, 2017, https://tcf.org/content/commentary/second-class-students-vouchers-exclude/.

- Fairlie, “Racial Segregation and the Private/Public School Choice,” 6.

- Peterson, Campbell, and West, “Who Chooses? Who Uses?” 60; and Witte, “The Milwaukee Voucher Experiment,” 234.

- Joshua Cowen, “Who Chooses, Who Refuses? Learning More from Students Who Decline Private School Vouchers,” American Journal of Education 117, no. 1 (November 2010): 7.

- Peterson, Campbell, and West, “Who Chooses? Who Uses?” 60; and Joshua Cowen, “Who Chooses, Who Refuses?,” 7–8. A study of the first five years of Milwaukee’s private school voucher program was an exception, finding that voucher users were somewhat less likely than low-income students in the public schools to have married parents. Witte, “The Milwaukee voucher Experiment,” 234.

- U.S. Census Bureau, “Table 8. Enrollment Status for Families with Children 5 to 4 Years Old, by Control of School, Race, Type of Family, and Family Income October 2012,” Current Population Survey, October 2012, https://www.census.gov/hhes/school/data/cps/2012/Tab08.xls.

- Arianna Prothero, “What Are School Vouchers and How Do they Work?” Education Week, January 26, 2017, https://www.edweek.org/ew/issues/vouchers/.

- U.S. Census Bureau, “Table 8. Enrollment Status for Families with Children 5 to 4 Years Old, by Control of School, Race, Type of Family, and Family Income October 2012.”

- Witte, “The Milwaukee Voucher Experiment,” 231; and “127 Schools Plan to Participate in Milwaukee Parental Choice Program,” News Release, Wisconsin Department of Public Instruction, January 31, 2017, https://dpi.wi.gov/news/releases/2017/127-schools-plan-participate-milwaukee-parental-choice-program.

- Brian Gill, P. Mike Timpane, Karen E. Ross, Cominic J. Brewer, and Kevin Booker, What We Know and What We Need to Know about Vouchers and Charter Schools (RAND Corporation, 2007), http://www.rand.org/pubs/monograph_reports/MR1118-1.html, 158.

- Peterson, Campbell, and West, “Who Chooses? Who Uses?” 60.

- Jay P. Greene, The Racial, Economic, and Religious Context of Parental Choice in Cleveland, Prepared for the Annual Meeting of the Association for Policy Analysis and Management, October 8, 1999, https://www.hks.harvard.edu/pepg/PDF/Papers/parclev.pdf, 10.

- Stephen P. Broughman and Nancy L. Swaim, Characteristics of Private Schools in the United States: Results from the 2013-14 Private School Universe Survey. First Look. (U.S. Department of Education, November 2016), http://nces.ed.gov/pubs2016/2016243.pdf, 7, Table 2.

- Greene, The Racial, Economic, and Religious Context of Parental Choice in Cleveland, 17, Table 4.

- Jill Feldman, et al., Evaluation of the DC Opportunity Scholarship Program: An Early Look at Applicants and Participating Schools Under the SOAR Act, Year 1 Report, U.S. Department of Education, October 2014, https://ies.ed.gov/ncee/pubs/20154000/pdf/20154000.pdf , 11, Table 2-1.

- Bruce Fuller, Richard F. Elmore and Gary Orfield (eds.), Who Chooses? Who Loses?: Culture, Institutions, and the Unequal Effects of School Choice (Teachers College Press, 1996); and Mathis and Welner, “Do Choice Policies Segregate Schools?”

- Peterson, Campbell, and West, “Who Chooses? Who Uses?” 62.

- Witte, “The Milwaukee Voucher Experiment,” 235.

- Cowen, “Who Chooses, Who Refuses?” 8–9.

- Peterson, Campbell, and West, “Who Chooses? Who Uses?” 65.

- “Public vs. Private: Parental Involvement in K-12 Education,” American Institutes for Research, May 2, 2016, http://www.air.org/resource/public-vs-private-parental-involvement-k-12-education.

- Anna J. Egalite, Jonathan N. Mills, and Patrick J. Wolf, “The Impact of Targeted School Vouchers on Racial Stratification in Louisiana Schools,” Education and Urban Society 49, no. 3 (January 2017): 271–96.

- Louisiana Department of Education, “Scholarship Programs,” n.d., https://www.louisianabelieves.com/schools/louisiana-scholarship-program (accessed March 2, 2017).

- Egalite, Mills, and Wolf, “The Impact of Targeted School Vouchers on Racial Stratification in Louisiana Schools,” 281, Table 1.

- Ibid., 283, Table 3.

- Ibid., 290; see also Hayley Glatter, “The School-Voucher Paradox,” The Atlantic, February 15, 2017, https://www.theatlantic.com/education/archive/2017/02/the-voucher-paradox/516747/.

- Egalite, Mills, and Wolf, “The Impact of Targeted School Vouchers on Racial Stratification in Louisiana Schools,” 286, Table 4.

- For full current and past income requirements, see “127 Schools Plan to Participate in Milwaukee Parental Choice Program”; and Brian Kisida, Laura Jensen, James C. Rahn, and Patrick J. Wolf, “The Milwaukee Parental Choice Program: Baseline Descriptive Report on Participating Schools,” SCDP Milwaukee Evaluation Report #3, School Choice Demonstration Project, Department of Education Reform, University of Arkansas, February 2008, http://www.uaedreform.org/downloads/2008/02/report-3-the-milwaukee-parental-choice-program-baseline-descriptive-report-on-participating-schools.pdf.

- Jay P. Greene, Jonathan N. Mills, and Stuart Buck, “The Milwaukee Parental Choice Program’s Effect on School Integration,” SCDP Milwaukee Evaluation Report #20, School Choice Demonstration Project, Department of Education Reform, University of Arkansas, April 2010, 10, Table 6, http://www.uaedreform.org/downloads/2010/04/report-20-the-milwaukee-parental-choice-programs-effect-on-school-integration.pdf.

- Ibid., 11, Table 7.

- Ibid., 12, Table 8.

- Ibid., 8, Table 4, and 12, Table 9.

- Amaya Garcia, “Chile’s School Voucher system: Enabling Choice or Perpetuating Social Inequailty?” New America, February 9, 2017, https://www.newamerica.org/education-policy/edcentral/chiles-school-voucher-system-enabling-choice-or-perpetuating-social-inequality/.

- Juan Pablo Valenzuela, Cristian Bellei, and Danae de los Rios, “Socioeconomic School Segregation in a Market-Oriented Educational System: The Case of Chile,” Journal of Education Policy (2013), http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/02680939.2013.806995.

- Ray Fisman, “Sweden’s School Choice Disaster,” Slate, July 15, 2014, http://www.slate.com/articles/news_and_politics/the_dismal_science/2014/07/sweden_school_choice_the_country_s_disastrous_experiment_with_milton_friedman.html.

- Anders Bohlmark, Helena Holmlund, and Mikael Lindahl, School Choice and Segregation: Evidence from Sweden (Institute for Evaluation of Labour Market and Education Policy, 2015), http://www.ifau.se/globalassets/pdf/se/2015/wp2015-08-School-choice-and-segregation.pdf.

- Helen F. Ladd, Edward B. Fiske, and Nienke Ruijs, “Parental Choice in the Netherlands; Growing Concerns about Segregation,” Prepared for School Choice and School Improvement, Vanderbilt University, October 25-27, 2009, http://www.vanderbilt.edu/schoolchoice/conference/papers/Ladd_COMPLETE.pdf.

- Helen F. Ladd and Edward B. Fiske, “The Uneven Playing Field of School Choice: Evidence from New Zealand,” Journal of Policy Analysis and Management 20, no. 1 (Winter 2001): 43-63.

- Maxwell and Prothero, “Why Trump’s Plan for a Massive School Voucher Program Might Not Work.”

- Kimberly Quick, “Hartford Public Schools: Striving for Equity through Interdistrict Programs,” The Century Foundation, October 14, 2016, https://tcf.org/content/report/hartford-public-schools/.

- U.S. Department of Education, “Department of Education Fiscal Year 2017 Congressional Action,” December 21, 2016, https://www2.ed.gov/about/overview/budget/budget17/17action.pdf.

- Halley Potter, “Big Lessons on Charter Schools from the Smallest State,” The Century Foundation, August 26, 2014, https://tcf.org/content/commentary/big-lessons-on-charter-schools-from-the-smallest-state/.

- Mercedes Gonzalez, “Diverse Charter School Opens in Nashville,” The Century Foundation, August 21, 2014, https://tcf.org/content/commentary/diverse-charter-school-opens-in-nashville/.

- Kahlenberg and Potter, A Smarter Charter, 123–34.

- See Halley Potter, “Charters without Borders: Using Inter-district Charter Schools as a Tool for Regional School Integration,” The Century Foundation, September 16, 2015, https://tcf.org/content/report/charters-without-borders/.

- Arianna Prothero, “What the Difference between Vouchers and Education Savings Accounts?” Education Week, June 9, 2015, http://blogs.edweek.org/edweek/charterschoice/2015/06/school_vouchers_education_savings_accounts_difference_between.html.

- See Parents Involved in Community Schools v. Seattle School District #1; and U.S. Department of Justice, Civil Rights Division, and U.S. Department of Education, Office for Civil Rights, “Guidance on the Voluntary Use of Race to Achieve Diversity and Avoid Racial Isolation in Elementary and Secondary Schools,” December 2, 2011, http://www2.ed.gov/ocr/docs/guidance-ese-201111.pdf.

- Gary Orfield and Erica Frankenberg, Brown at 60: Great Progress, a Long Retreat and an Uncertain Future (Berkeley, Calif.: The Civil Rights Project, University of California-Berkeley, May 15, 2014), http://civilrightsproject.ucla.edu/research/k-12-education/integration-and-diversity/brown-at-60-great-progress-a-long-retreat-and-an-uncertain-future/Brown-at-60-051814.pdf.