This report is the fourth in a TCF series—The Cycle of Scandal at For-Profit Colleges—examining the troubled history of for-profit higher education, from the problems that plagued the post-World War II GI Bill to the reform efforts undertaken by the George H. W. Bush administration.

When George H. W. Bush became president on January 20, 1989, he inherited from the Reagan administration some unfinished business in higher education. Bill Bennett, President Reagan’s secretary of education, had launched an effort to shut down “proprietary schools [that] deserve to be eliminated based on their irresponsible treatment of students.”1 His efforts were largely stymied, however, by Democrats who controlled Congress. But if the rhetorical assault on for-profit schools reached its apex in the Reagan administration during Bennett’s tenure, the GOP’s regulatory and legislative crackdown on for-profit schools peaked in George H. W. Bush’s administration, under the leadership of Secretary of Education Lamar Alexander.

The abuses by trade schools and the resulting student loan defaults that plagued the industry during the Reagan administration continued during the Bush administration, with the for-profit sector’s student loan default rate reaching an all-time high of 41 percent in 1990. Not surprisingly, media coverage of trade school abuses boomed too. Bruce Chaloux, a well-known advocate for online learning, noted that in the years preceding reforms adopted in 1992:

the media have provided story after story of misuse, abuse, and fraud within the system, ranging from the enrollment of prisoners to the falsification of records and signing up of nonexistent students to pad enrollments. After bilking the federal government, these educational entrepreneurs would close up shop, move their operations, change institutional names, or take other evasive measures to stay ahead of federal regulations.2

In some ways, the most outrageous scams, many of which occurred at small, storefront schools, created a false memory of the era. Lawmakers in the early 2000s, who watched as big corporate chains of colleges grow, mistakenly believed that the abuses of the 1980s did not involve big corporate players. That impression was encouraged by for-profit lobbyists, who told legislators that they need not worry about a repeat of past scandals: “the industry is different now,” was the mantra. The reality, however, is that several big chains rose high and died in disgrace in the 1980s and early 1990s, including one that later returned to life as Corinthian Colleges.3 Abuses in the 2000s led to Corinthian’s collapse in 2014.4

The Cycle Of Scandal At For-Profit Colleges Series

Read the series of papers focusing on the repeated for-profit college scandals of the past sixty years.The GOP Reversal on For-Profit Colleges in the George W. Bush Era

When President George H. W. Bush “Cracked Down” on Abuses at For-Profit Colleges

The Reagan Administration’s Campaign to Rein In Predatory For-Profit Colleges

Vietnam Vets and a New Student Loan Program Bring New College Scams

Truman, Eisenhower, and the First GI Bill Scandal

The For-Profit College Story: Scandal, Regulate, Forget, Repeat

The GOP Has a Long History of Cracking Down on “Sham Schools”

The Press Hits Pay Dirt in Covering Abuses

Illustrative of the coverage of for-profit misdeeds was a multi-part series that started in May 1989 in the Houston Chronicle, the hometown paper for President Bush’s former congressional district. Among other scandals, the series recounted the story of two for-profit schools that bussed in the homeless from shelters in Dallas, San Antonio, and New Orleans to Houston, signed the homeless students up for federal financial aid, and then largely left them on the streets for Houston charities to house and shelter. When one school owner finally agreed to stop the practice of long-distance recruiting for homeless students, he explained “we have taken our share.”5 Another story told of a nine-school chain that “cheated thousands” by “doing a disappearing act with students’ dreams.”6 Contrasting the for-profit schools with community colleges, the “Signed Up, Sold Out” series found that:

widespread abuses promote human misery, encourage consumer fraud and bilk taxpayers who underwrite the guaranteed student loan program. Most trade schools use commissioned sales people—usually in large numbers—who sometimes lure unsophisticated students from shelters, blood banks, streets, unemployment lines and other places gullible or desperate people are likely to gather.

In discussing financial assistance with prospects, recruiters trying to make heavy quotas often blur the distinction between government grants and loans that must be repaid, and are instructed to use sales techniques that shame people for being poor and undereducated. . .

[S]ome schools routinely manipulate the testing so that almost no students who qualify for federal aid are turned down even if they can barely read and write.7

A slew of similar series in other major newspapers from across the country had preceded the Houston Chronicle’s investigation, including a two-part series in the Los Angeles Times, “Vocational Schools: Poor Being Taken for a ‘Bad Ride,’” and “Painful Lessons: Vocational School Folds, Leaves Students in Limbo.”8

Senator Sam Nunn Opens an Inquiry

Meanwhile, in Congress, the Senate Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations, chaired by Senator Sam Nunn (D-GA), opened an inquiry into the problems of the guaranteed student loan program. Senator Nunn was a fiscal conservative, a Southern Democrat, and the powerful committee chairman of the Senate Armed Services Committee. The investigation led to eight days of hearings from February to October 1990, at which Nunn’s subcommittee heard from nearly fifty witnesses, who recounted tales of extensive fraud and abuse at for-profit schools.

A recruiter for the North American Training Academy truck driving school who testified at the hearings was one of the many witnesses to describe a seemingly endless list of abuses perpetrated by for-profit postsecondary institutions. “In the proprietary school business what you sell is ‘dreams,’ and so 99 percent of my sales were made in poor, black areas [at] welfare offices and unemployment lines and in housing projects,” the recruiter reported. “My approach was that ‘if [a prospect] could breathe, scribble his name, and had a driver’s license, and was over 18 years of age, he was qualified for North American’s program.”9 The salesman even dragged one potential customer down to a pawn shop so he could rustle up enough cash to make a down payment for the program. Other recruiters admitted they had used phony addresses, like, “403 Cant Read, Pritchard, Alabama,” when signing students up for loans, making it all but impossible for banks or the federal government to find the students when guaranteed loans came due.10

I used to buy the rhetoric that there were just a few bad apples, but then I discovered that there were orchards of bad apples.

The Nunn committee hearings made it difficult for career school advocates to continue maintaining that the problems of the sector were just isolated to a few predatory schools. The president of the Massachusetts Higher Education Assistance Corporation, a major guarantor of federal student loans, told the members of the Nunn committee: “I used to buy the rhetoric that there were just a few bad apples, but then I discovered that there were orchards of bad apples.”11

The Senate committee’s investigation was very much a bipartisan affair.12 The ranking Republican member on the committee, Senator William Roth (R-DE), fumed at one hearing that “rather than allowing these young people to improve themselves, [unscrupulous school operators] actually leave [them] in a worse position than when they started. Because of the deceptive practices of such schools, these students have to pay for an education they never received.” Students who lacked adequate training, Roth added, “are not able to get jobs by which they can repay [their] federally guaranteed loans and thus suffer the added humiliation of seeing their credit ratings destroyed in the process.”13

The Financial Damage from a Runaway Industry

In addition to the pressure generated by media coverage and the Nunn committee hearings, burgeoning budget deficits and bankruptcies in the for-profit sector made it almost impossible for Congress or the Bush administration to duck the issue of soaring default rates at career schools, for which the federal government eventually had to pick up the tab. In 1988, the ten proprietary schools that collected the largest amounts of federal student aid, over $1 billion, had an average student loan default rate of 36 percent—the exact same default rate that Corinthian Colleges had twenty years later, in 2008.

The shortchanging of students significantly worsened when many schools closed, leaving the school’s bank accounts empty, even as many school executives stuffed their own pockets with cash provided by taxpayers. In the two and a half-year period from October 1985 to June 1988, 167 proprietary schools certified to participate in Title IV student aid programs closed. Fifty-three of those schools closed before their students received all educational services—leaving as many as 10,000 students in the lurch and $30 million in unpaid and unfulfilled loans, for which either the students or the federal government would be left holding the bag.14

Big for-profit chains—not just mom-and-pop trade schools—were among the schools that shuttered their doors. Following audits or investigations by the Office of the Inspector General (OIG) at the Department of Education, four of the five career schools who received the most federal dollars in student aid had either closed their doors by mid-1991 or stopped receiving federal funds, and the fifth for-profit chain had closed most of its schools after declaring bankruptcy.15

Perhaps the biggest collapse was that of the National Education Corporation (NEC) for-profit chain, which owned as many as eighty-nine schools in the 1980s. At the time, “NEC was the largest provider of for-profit education in the United States, dominating the market and attracting glowing notice from sector analysts.”16 However, after a decade of steady growth and profits, the $450 million corporation unexpectedly posted a loss in 1990. NEC’s chief executive officer was fired, and shareholders sued, alleging NEC had concealed its financial plight. To cover financial losses and restore shareholder confidence, NEC started rapidly selling off its campus-based schools. By 1995, NEC was down to sixteen schools. Those schools were finally purchased by a group of former NEC executives—who used them to form a new for-profit chain, Corinthian Colleges,17 which, twenty years later, would collapse in much the same manner.18

Compounding the problem of school closings, the scope of the student loan default problem mushroomed. With the creation in 1982 of a new federal student loan program—the Supplemental Loans for Students (SLS) program—and the program’s liberalization under President Reagan, the volume of federally backed student loans was skyrocketing. The SLS program made extra loan funds available to older students. With limits on the program relaxed, for-profit schools saw a huge new pool of federal student aid open up, and rushed to take advantage of the opportunity. In a matter of months, SLS loans to proprietary school students exploded. In 1986, 8 percent of all SLS borrowers were proprietary school students; two years later, that figure stood at 62 percent.19

The final straw in the case for regulating the for-profit sector was the sudden collapse in 1990 of the largest guarantor of federal students loans, the Higher Education Assistance Foundation (HEAF). As a direct result of HEAF guaranteeing a large portfolio of loans to students at for-profit schools, HEAF collapsed when it could no longer pay banks full reimbursement for the soaring numbers of students who were defaulting. The U.S. Department of Education bailed out the banks and shut down HEAF at a first-year taxpayer cost of $212 million.20

Collectively, the news stories about students misled by schools, the Nunn committee hearings, the shuttering of a number of the nation’s largest for-profit chains, the runaway growth in an newly created auxiliary loan program, and the collapse of a giant student loan guarantee agency all underscored the urgency of reigning in for-profit schools for the Bush administration.

Lawmakers Respond to the Crisis

To address the costs of sudden school closures, the Bush administration proposed regulations in June 1989—never finalized—that required proprietary schools to establish “teachout” arrangements with another school offering a similar career program. Teachout provisions enabled students to complete their course of study at the same cost if the original school closed. The Department of Education’s proposed regulations plainly reflected the fact that, a quarter century before Corinthian Colleges and ITT Technical Institutes folded in the Obama era, the problem of students left stranded mid-stream and deep in debt after for-profits closed was already common enough to merit federal regulation.

On Capitol Hill, a few key Democratic lawmakers who had previously defended the for-profit colleges began joining with Republicans such as Representative Marge Roukema (R-N.J.), who had called for a regulatory and legislative crackdown on “the growing number of scam trade schools.”21 In August 1990, Representative Pat Williams (D-MT), then chairman of the House Subcommittee on Postsecondary Education, told the New York Times that rising defaults, “taken together with the scandals that have gone on in some of these trade schools, has sent out a clarion call for tighter regulations and stricter laws.” Williams believed that a minority of career schools abused the student loan program “but it’s such a large minority that it’s creating an educational crisis in this country.”22

As the country entered a recession, lawmakers were eager to reduce a growing national deficit. The burgeoning student loan program was among the first programs on the congressional chopping block. In an attempt to control spending and increase accountability, Congress passed—and President Bush signed—a budget bill with bipartisan support in November 1990 which ejected from the federal aid programs any school with a default rate above 35 percent, with the cutoff scheduled to drop to 30 percent in 1993. As a result, 607 schools were eventually barred from further participation.23 The 1990 law represented the delayed triumph of Reagan’s Secretary of Education Bill Bennett. Congress—which had balked at the idea three years earlier—adopted “a plan to control defaults that differs from Bennett’s original idea only in the details,” the Washington Post reported.24

Lamar Alexander, who assumed the position of secretary of education under President Bush in March 1991, kept up the pressure on the for-profit sector. After less than a month on the job, Alexander went to Capitol Hill to propose increased oversight and regulation (a far cry from his more recent opposition to almost every effort by the Obama administration to increase accountability for taxpayer dollars at for-profit schools).25 In his testimony, Alexander proposed lowering the cutoff point for when institutions would lose eligibility for federal student loans from a 35 percent default rate to 25 percent, and doubling the course length minimum to six months or 600 hours, for programs to retain their eligibility for guaranteed student loans. To curb recruiting abuses, Alexander also proposed banning the use of commissions or bonuses to pay admission and financial aid staff based on the number of students they enrolled or the number of students enrolled in student aid.

“we must ask not only ‘do our students have access,’ but also ‘access to what?’”

All three proposals would have overwhelmingly impacted for-profit schools. Secretary Alexander spoke of the serious problem of “institutional abuse” of federal aid, insisting “we must ask not only ‘do our students have access,’ but also ‘access to what?’” Alexander said that he would be looking to see if students were receiving “Access to an institution that produces mostly dropouts, not graduates, or produces graduates that are not employable in the fields for which they have been trained.”26

Alexander’s attempt to seize the initiative in curbing student defaults and reducing institutional abuses was soon overtaken when the Nunn committee issued its final report in May 1991. The searing report, adopted with no negative votes, was even harder on the for-profit industry than the Teague report, the House Committee investigation into the GI Bill abuses nearly four decades earlier. The senators found that the federal student loan program:

particularly as it relates to proprietary schools, is riddled with fraud, waste, and abuse, and is plagued by substantial mismanagement and incompetence. . . fail[ing] . . . to insure that federal dollars are providing quality, not merely quantity, in education. As a result, many of the program’s intended beneficiaries—hundreds of thousands of young people, many of whom come from backgrounds with already limited opportunities—have suffered further. . . . Victimized by unscrupulous profiteers and their fraudulent schools, students have received neither the training nor the skills they hoped to acquire and, instead, have been left burdened with debts they cannot repay.27

The Bush administration welcomed the Nunn committee report and its twenty-seven recommendations to crack down on abuses in the student loan program, which included banning the use of federal grants and loans to pay for correspondence courses and requiring private accrediting bodies to impose minimum quality standards on schools. Michael Farrell, the acting assistant secretary for postsecondary education, told the Washington Post and the New York Times that the Nunn report “will make my job easier.”28

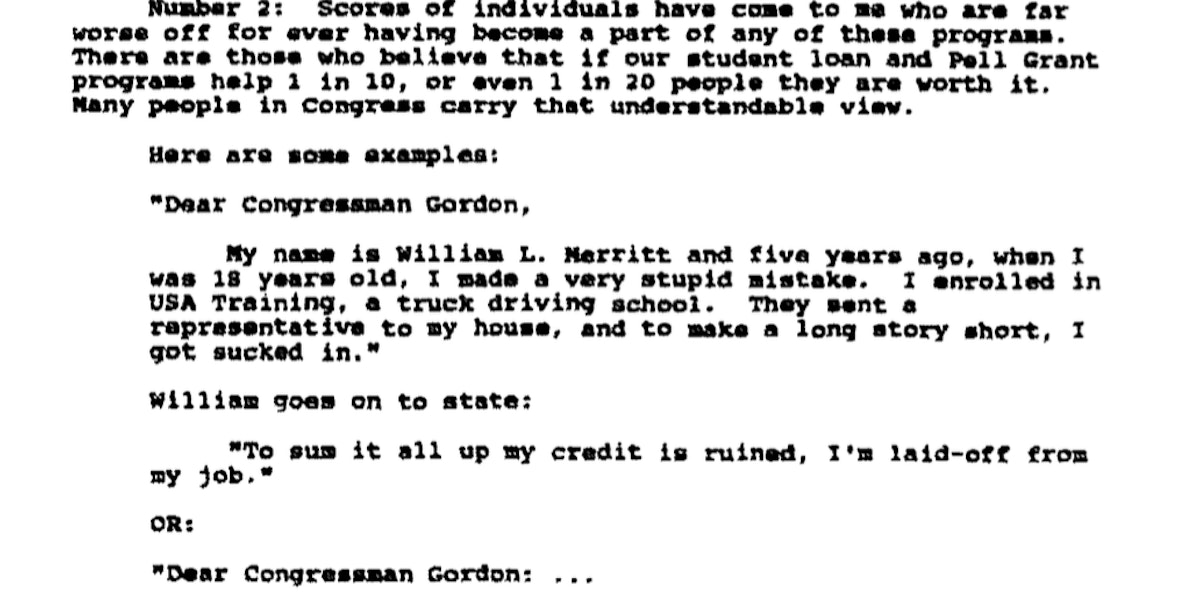

Just a day after the release of the Nunn committee’s report, the House Subcommittee on Postsecondary Education held its hearing on HEA reauthorization and integrity in the student loan program. Rather than devolving into the then-familiar partisan differences on regulating for-profit schools—with Republicans arguing for more accountability and Democrats insisting that for-profit schools positively impacted underserved populations—the hearing took a very different turn. Two Democratic lawmakers, Maxine Waters (D-CA) and Bart Gordon (D-TN), testified in favor of a crackdown on predatory for-profit institutions, largely based on their personal exposure to students from career schools.

Representative Gordon, a moderate Democrat from Alexander’s own state of Tennessee, had achieved the distinction of becoming the first congressional representative to use a hidden camera for a news exposé of for-profit schools. In the past, Gordon had “enthusiastically” supported big increases in student financial aid, regardless of the issue of accountability requirements for using federal dollars. But after HEAF collapsed in 1990, Gordon looked into the issue more closely and quickly discovered abuses “broader and deeper than I’d ever imagined.”29 He soon decided to work together on a report on for-profit schools with the investigative reporting team from Exposé, a new NBC newsmagazine program hosted by anchor Tom Brokaw. Exposé’s show on March 10, 1991, “The Trade School Scam,” vividly depicted student aid abuses at for-profit schools. Representative Joseph Kennedy (D-MA) recalled watching the program as NBC correspondent Brian Ross “went into one school where they were taking alcoholics, people with drug abuse problems and homeless people and . . . having them apply for Federal aid. And then as soon as the individual would make the application, they’d be given $100, sent right back out the door, and then the school would collect several thousand dollars from the federal government.”30

Representative Gordon, doing his best to appear like a working-class Joe after going unshaven for three days, posed as a prospective student interested in enrolling at Draughon’s Junior College, a large Tennessee for-profit school with a 66 percent default rate. With a hidden camera in his shoulder bag, Gordon recorded a conversation with a school salesman about the school’s program to train truck drivers. The salesman told Gordon that it was easy to get a guaranteed loan to pay for the $5,400 tuition to learn how to drive a truck. Gordon testified at the House Subcommittee on Postsecondary Education hearing that he had been “hot-boxed. I was told I could get free money. . . . It was simply an effort to not tell me I had any kind of responsibility [to repay the loan], but rather, to get me to enroll there.”31

As far as Representative Gordon was concerned, proprietary school salesmen were little more than “bounty hunters.”32 The remedy for the abuses, Gordon testified, was to tie eligibility for federal aid to “some kind of benchmark for success . . . completing courses, graduation rates—that’s a benchmark. Getting a job, job placement, that’s a benchmark. Paying back your loan, that’s a benchmark.”33

Next up on the witness stand was Representative Waters, who had her own regulatory prescriptions for addressing abuses at for-profit schools.

In her Los Angeles district, Waters regularly sponsored job workshops in public housing projects and other community forums to help constituents prepare resumes, search for jobs, and practice for interviews. At the workshops, Waters began asking attendees “how many people have been ripped off by vocational schools,” and frequently had 60 percent to 70 percent of people raising their hands. Waters had spoken to hundreds of constituents who had been “cheated” by proprietary schools, and hundreds of her constituents had filled out questionnaires that attested to the “unfair recruitment practices, shoddy training, inadequate placement services, and utter failure of these so-called schools to provide any meaningful education leading to jobs.”34 For the better part of four years, Waters had been accumulating boxes of affidavits from constituents who complained they had been the victim of fraudulent practices by for-profit schools.35

Waters’ portrayal of for-profit schools was so sweeping that she warned her Democratic colleagues: “My testimony may be shocking to some of you, and particularly to those of you who kind of warned us in advance that you feel very strongly about your support for some of these private postsecondary schools.” But, she added, she was ready to bring in her boxes of affidavits from dissatisfied students for her colleagues to examine first-hand.

Waters advocated prohibiting for-profit schools from relying totally on federally aided students, banning commission-paid recruiting, requiring schools to disclose completion and job placement rates before students enroll, and canceling loans when a school closes and leaves students unable to complete their program of training. Waters also proposed a substantial expansion of the then-narrow “borrower defense” rules, so that students harmed as a result of a violation of federal law could bring action for debt relief, and assert the same defenses to repayment of a student loan against the federal government that the student could have asserted against a school that closed or violated federal law.36 “It is as appalling as it astonishing,” Waters told the committee, “that proprietary vocational schools need not satisfy any performance standards. Theoretically, a school could have no graduates, could have provided no training actually leading to employment for its students, and could nonetheless continue to be eligible to participate in the federal loan and grant programs.”37

Of some note, the May 1991 House hearing marked one of the first occasions where Representative Steve Gunderson (R-WI), now the leader of the career school trade association, questioned for-profit school representatives about how to improve accountability at for-profit schools. Gunderson, a moderate Republican, had a personal exposure to career schools that most lawmakers lacked. After graduating from the University of Wisconsin in Madison, he had gone on to earn a certificate in broadcasting from the for-profit Brown School of Broadcasting.

Unlike his Republican colleague on the committee, Representative Roukema, Gunderson did not level a broadside attack on the for-profit industry. Still, he did make clear that he believed for-profit schools needed to implement more far-reaching reforms to reduce student loan defaults and curb abuses. In an exchange with Anthony Resso, the chairman of the Association of Accredited Cosmetology Schools, Gunderson challenged Resso’s assertion that Congress had “gone too far”38 in responding to public concerns about waste and abuse when it enacted provisions in 1990 to eliminate schools with high default rates from the student loan program. Gunderson told Resso: “We simply cannot take a reauthorization bill to the floor that doesn’t do something in addition to what’s already been done to deal with the issue of defaults.”

Moreover, Gunderson rejected states’ rights arguments and the claims of private accrediting agencies that the federal government should not have the authority to limit institutional access to the student aid program. “Other than health care,” Gunderson told Resso, “higher education is the only area where the government is expected to be the third party payee, but it has absolutely no ability to control the cost of the program. And you’re suggesting we ought to have no ability to control who has access to that program. In 1991, we don’t have that luxury.”39

The Democratic Chairman Balks

While there was new bipartisan support to take action to address abuses, some traditional pro-labor Democrats continued to defend the for-profit industry, most notably the powerful chairman of the House Education and Labor Committee, Representative William Ford (D-MI). Like Representative Gunderson, Ford had some personal experience with career schools. In 1940, when Ford was just fourteen years old, his parents enrolled him in the Henry Ford Trade School in Detroit, where he was taught how to use the tools he would need to become a tool and die maker for Ford Motor Company. Despite later going on to earn a law degree, Ford said his time at the trade school left an indelible impression on him and marked the first time he had worked side-by-side in a school with black students. He told the committee hearing: “Many people have no choice but to go [to trade schools] and they have no options except going to the military or going to schools that, for a fee, will try to teach them a specific level of skills.”40

Ford’s view was that it is difficult if not impossible to set standards for postsecondary institutions that effectively distinguished when institutions were genuinely educating students. Moreover, when Congress and federal officials had tried to do so in the past, the results had often backfired. “Part of the problem,” Ford stated during the committee’s hearings, was that public officials “quickly accept the idea that there are some kinds of schools that you can measure the people coming out of and decide whether the school is a good school [based] on the product it turns out.”41 Only about two-thirds of people who took the bar exam in Michigan passed it on the first try, Ford noted. But if just two-thirds of the graduates of a cosmetology school passed Michigan’s beautician license exam, “we would be condemning the devil out of them.”42

Years earlier, Ford had been infuriated when the Veterans Administration (VA) decided to end educational benefits at “weekend college” for veterans who worked full-time during the week. One of Ford’s alma maters, Wayne State University in Detroit, had run a successful weekend college program to train veterans as automotive workers, but the VA determined that weekend college programs failed to meet the VA’s minimum hour requirements for maintaining eligibility for financial aid. Some 12,000 Vietnam vets lost their opportunity to use VA educational benefits to attend weekend college, Ford said, because of the VA’s “pig-headed bureaucratic approach.”43

Like Republican lawmakers today, who assert it is unfair to target for-profit schools with accountability measures, Ford feared that if Congress tried “to apply one standard to one kind of school [in the guaranteed student loan program] and one to another, that we’re going to be in court and found to be discriminatory.”44 As far as Ford was concerned, treating proprietary schools differently than any other postsecondary institutions was tantamount to having the government engage in “class warfare.”45 Representative Joseph Gaydos (D-PA) agreed with Ford: “Some people have taken the easy route and found a scapegoat: career training schools. Some people believe that the sole purpose of these schools is to rip off the government through student loan programs. This is completely untrue and false.”46

The political appeal of for-profit colleges among labor liberals and minority lawmakers stemmed in part from the demographic of disadvantaged students who attended for-profit schools. But the vast political sway of for-profit schools also stemmed from their geographic dispersion. For-profit schools were—and today remain—located in virtually every lawmaker’s district. Except in egregious cases of fraud, many congressmen were reluctant to criticize local trade school owners in their district who were preparing constituents for careers, and who often hired lobbyists and gave generous campaign contributions. At a hearing in 1995 on proprietary school abuses, Senator Nunn asked David Longanecker, then the assistant secretary for postsecondary education, if Longanecker had been “able to handle the political pressures when you start removing a school” from the federal aid programs. Longanecker dryly replied: “One of the things I have learned is there are lots of bad institutions in the country, but none are in anybody’s congressional district.”47

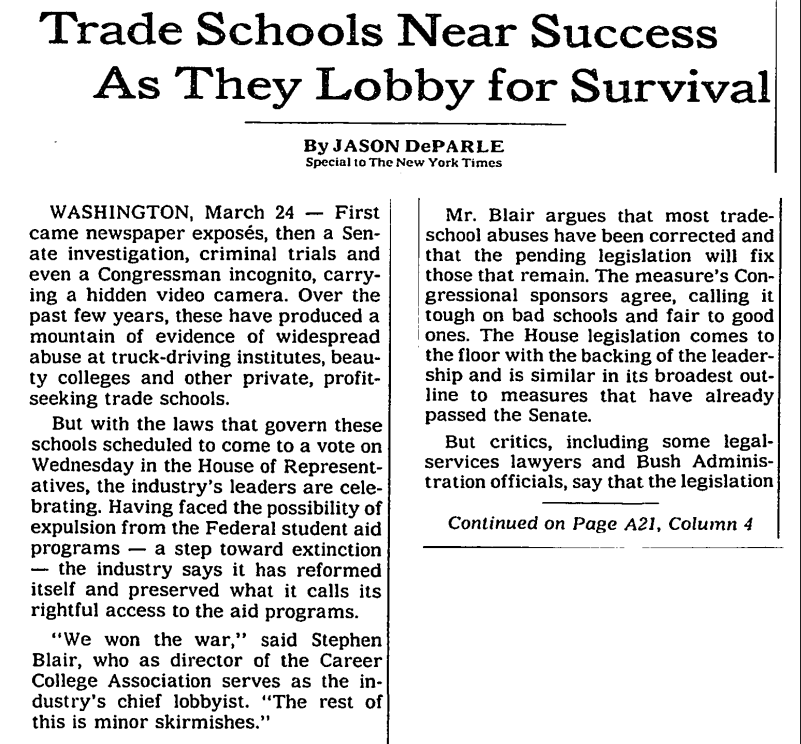

High-profile lobbyists, then as now, aided the industry’s cause. The National Association of Trade & Technical School (NATTS) $1 million-a-year lobbying campaign, launched in 1989, included hiring Bob Beckel, the campaign manager for Senator Walter Mondale’s (D-MN) 1984 presidential run, to organize trade schools into statewide networks under the moniker of “Skills 2000” organizations, each of which courted local congressmen and their staffs. From the GOP, NATTS president Stephen Blair hired former Reagan White House aide Haley Barbour to dampen the appetites of Republican lawmakers and the Bush administration for accountability measures that would primarily impact for-profit schools.

At the same time, NATTS ginned up direct mail efforts, generating “thousands of postcards [to congressmen] from students complaining that their student loans were going to be taken away”—which prompted fifteen members of the House Higher Education Subcommittee to write an angry letter accusing the association of an “unwarranted attempt to place fears in the hearts of students.”48

Last but not least, increased oversight of for-profit schools was often avoided because, for distinct reasons, these institutions appeal to bipartisan sympathies. “Republicans tend to see these institutions as businesses and say therefore we ought not to be too harsh on someone who’s trying to make buck,” Thomas Wolanin, Representative Ford’s staff director told the New York Times in 1992. “Democrats tend to see them as points of access to training for some lower-income students.”49

While abuses were predominantly occurring at for-profit schools in the early 1990s, public and nonprofit colleges were getting caught up in many of the proposals for tightened oversight of higher education. And as for-profit schools garnered a larger share of federal student aid dollars, competition for resources between the for-profit sector and the traditional higher education sector also increased. In response, some of the associations representing traditional colleges floated the idea of having a separate federal student aid program for the for-profit schools.50 For-profit association leaders responded aggressively, going so far as to claim that having their own separate funding stream would amount to “educational apartheid.”51 The key Democratic committee chairmen in both the House and Senate announced they would not support separate programs.52 Representative Ford was especially adamant, saying that he was “absolutely never going to support” the idea of differential funding and regulation for different sectors of higher education.53

Two years later, the idea of separate treatment of for-profit colleges was brought up again, in a somewhat different form, this time by Secretary of Education Lamar Alexander. In a letter commenting on the House committee bill to renew the Higher Education Act (HEA), Alexander wrote that Congress should distinguish between oversight of “vocational” programs—the route through which for-profit schools are eligible for federal aid—and other types of postsecondary “collegiate” degree-granting programs. For “collegiate programs,” Alexander favored maintaining oversight by private accrediting agencies. But for vocational programs, he called for strengthened state oversight and an expanded federal role.54 “The Federal Government should set the parameters for certain standards, such as outcome measures, for use by States in carrying out their increased responsibilities,” Alexander wrote. “The scope of a State’s review should explicitly include institutional performance in student outcome areas such as program completion and job placement rates.”55

Not surprisingly, Representative Ford rejected Alexander’s proposal for differential regulation by sector. But with the support of Senate Democrats, Congress did take up Alexander’s idea to expand state and federal authority for program reviews and certifying ongoing eligibility for student aid at for-profit schools. Unlike the House bill, the Senate bill to extend the Higher Education Act gave states and the federal government substantial new powers to control the exit gate from student aid programs, even as private accrediting agencies maintained their traditional gatekeeper role over the entry gate to student aid programs.

The Senate bill’s provisions—ultimately adopted in 1992—created State Postsecondary Review Entities (SPREs), which were intended to be a “weapon to attack fraud and abuse” and high-default rates in the for-profit sector.56 In her case study of the rise and rapid fall of SPREs, Terese Rainwater, the former national director of the State Scholars Initiative, notes that “In their original conception, SPREs would be part of a joint federal/state effort to rein in the proprietary sector of postsecondary education. . . . The SPRE concept was the George H. W. Bush administration’s solution to the problems of better consumer protection and better state oversight in postsecondary education.”57 Under the 1992 act, state education agencies had to conduct reviews of institutions in their states that, among other red flags, had a student-loan default rate of at least 25 percent, or a default rate of at least 20 percent at institutions where more than two-thirds of students received federal aid, or more than two-thirds of expenditures paid with student aid or Pell Grants.

More striking, in light of the controversy over the Obama administration’s gainful employment regulation, the 1992 amendments to the Higher Education Act effectively created the first statutory requirement for states to develop debt-to-earnings tests like those promulgated by the Obama administration to assess if career programs were in fact producing gainfully employed graduates who could pay off their student debt from their earnings. Under the 1992 law, if an institution offered a program designed to prepare students for gainful employment, the SPREs had to develop a standard to determine whether the tuition and fees charged for that program were reasonable, given the amount of money that a student who successfully completed the program might reasonably be expected to earn.58 In 1994, after seeking input on how to implement the new law, Richard Riley, President Bill Clinton’s secretary of education, asked states to examine whether tuition at certain vocational programs was reasonable given their likely future earnings. He explained that “institutions that purport to offer education to prepare students for occupations ought to be able to substantiate that the education they provide does just that . . . for students who receive loans for their education, it is reasonable to expect that they will qualify for positions that will enable them to repay their loans.”59

The traditional higher education community fiercely opposed SPREs, on the grounds that they would expand state authority to review and bar programs from receiving federal student aid.60 In November 1994, Republicans in the House, led by Speaker Newt Gingrich, introduced their Contract with America, promising to reduce government regulation, after Republicans gained control of both houses of Congress for the first time since the 1950s. One of the first regulations that Republican lawmakers eliminated in March 1995 were the SPRE provisions, the 1992 GOP prescription of the Bush administration for improving consumer protections and reducing abuses at for-profit schools. By withdrawing funding and ending implementation of the SPREs, Republicans in Congress effectively blocked states from implementing their own gainful employment standards for career programs.

Congress Finally Acts

In spring 1992, legislation to renew the Higher Education Act reached its final stages, and ultimately garnered strong bipartisan support in both the House and Senate. When President Bush signed the bill on July 23, 1992, with Lamar Alexander by his side, he observed that “Lamar was telling me, and our own people in the White House have told me, that this was truly a bipartisan effort.”61 Notably, Bush praised the legislation for containing “a number of valuable program integrity and loan default prevention provisions. In particular, these provisions will crack down on sham schools that have defrauded students and the American taxpayer in the past.” Bush proved prophetic. The 1992 HEA amendments included multiple provisions to improve the integrity of student aid programs, most of which applied to all schools but which overwhelmingly impacted for-profit schools.62 The provisions included:

- For-profit institutions were limited to receiving 85 percent of their revenue from federal student aid programs. A similar market-value test for veterans educational benefits had required at least 15 percent of students to pay without federal aid, to ensure both that the tuition price was reasonable and not just based on the aid available, and that some students would choose to enroll in a for-profit institution even without federal aid.63

- Schools that offered more than 50 percent of their courses by correspondence, or where more than 50 percent of students were enrolled in correspondence courses, were barred from receiving federal student aid.64

- Institutions receiving Title IV funding were barred from paying commissions, bonuses, or incentive payments to recruiters, admissions officers, and other institutional representatives based directly or indirectly on their success in enrolling students or obtaining financial aid.

- Short-term vocational programs had to verify both student completion and job placement rates of at least 70 percent to be eligible for federal student aid.

- More than 50 percent of students had to have a high school diploma or GED at non-degree-granting institutions for the institution to remain eligible for Title IV aid.

- Institutions became ineligible for federal loans if their default rates exceeded 40 percent for a single year, or if their default rates exceeded 25 percent for three consecutive years.

Despite an industry campaign to weaken the law, the default provisions of the 1992 amendments led to widespread closures of for-profit schools. During fiscal years 1991 to 1994 alone, 890 schools were threatened with losing their eligibility to participate in the federal student loan program because their default rates exceeded 25 percent three years running. Two-third of those schools lost their eligibility and some 250 appealed the department’s calculations of their default rates.65 By the time the full impact of the 1992 law ran its course, one report estimated that “900 institutions shut down as a result of [the law]—other estimates were as high as 1,500.”66 The impact of the new default rate cutoffs for federal aid eligibility was concentrated overwhelming among for-profit schools. In 1996, for example, all of the 203 schools that lost eligibility for student loan programs because of high default rates were for-profit schools.67

In some cases, however, the reforms also had perverse effects. Deferments and forbearances on student loans more than doubled from 1992 to 1996, from 5.2 percent to 11.3 percent, as institutions sought to skirt the new default rate requirements while maintaining eligibility for student aid.68 Since borrowers in deferment or forbearance do not make payments on their loans, they could not be counted as defaulters. In effect, borrowers in deferments and forbearances reduced cohort default rates for an institution, without establishing any ability to repay their loans.

In response to new job placement and completion requirements for short-term vocational programs, career school certificate programs also took to “course stretching” to lengthen their courses beyond the minimum training and licensing hours needed to land a job, so that their programs could maintain eligibility for federal student aid. Numerous OIG investigations and audits found that course-stretching was particularly common in formerly short-term programs that trained people to become security guards, nurse assistants, manicurists, secretaries, and truck drivers.

For unscrupulous school owners, the ease of access to Pell Grant revenues was “a way to rob a bank without a gun.”

The new default rate restrictions in the 1992 law also propelled a mass exodus of for-profit schools from the guaranteed student loan program to the Pell Grant program69—the latter of which provided scholarship grants to low-income students and thus had no default rate restrictions. Once a school was certified for the Pell program, it was given a PIN number and could make withdrawals on the Pell Grant awards allotted to its students, much like as at an ATM. For unscrupulous school owners, the ease of access to Pell Grant revenues was “a way to rob a bank without a gun.”70 Or, as Senator Nunn said at hearings in the fall of 1993, the Pell Grant program provided “almost an invitation for people who are not honest to rip it off.”71

Still, the Bush administration’s goal of reducing defaults was achieved, fulfilling the aims of the default reduction initiatives first launched by the Reagan administration. The student loan default rate at for-profit schools fell from 36 percent in 199172 to 13 percent by the 1998–99 school year.73 The number of students at proprietary schools who defaulted on their loans fell by more than two-thirds, from 319,000 students in 1988 to 99,000 students in 1993.74 All in all, George H. W. Bush’s self-described “crack down” worked.

Timeline of For-Profit Higher Education

Scroll through the below timeline to view the history of for-profit higher education.

Notes

- Quoted in the December 1987 Senate hearings, Problems of Default in the Guaranteed Student Loan Program, 122, https://drive.google.com/a/tcf.org/file/d/0B7aqIo3eYEUtbENMVUxvVTYwaXM/view?usp=sharing.

- Bruce N. Chaloux, “State Oversight of the Proprietary Sector,” in Community Colleges and Proprietary Schools: Conflict or Convergence? New Directions for Community Colleges 91 (Fall 1995): 89. The drumbeat of investigative exposes was so voluminous that in August 1988 the New York Times education editor Edward Fiske observed that “If computer programming colleges, truck driving academies and other profit-making trade schools did not exist, politicians and journalists would have to invent them. There is no more surefire way to stir up publicity than to visit Rosie’s College of Cosmetology or Fly-By-Night Aviation Academy and find an unemployed recent dropout who thought that the form he signed was a lottery ticket, rather than an application for a $2,500 Guaranteed Student Loan that he would have to repay.” Edward B. Fiske, “Education; Lessons,” New York Times, August 24, 1988.

- By 1980 the National Education Corporation (NEC) was trading on the New York Stock Exchange and owned eighty-nine schools. It began to disintegrate in 1990, and in 1995 a group of former executives purchased some remaining schools and called the new company Corinthian Colleges. Kevin Kinser, From Main Street to Wall Street: The Transformation of For-Profit Higher Education: ASHE Higher Education Report 31, no. 5 (Hoboken, N.J.: John Wiley & Son, 2006), 43-44.

- Jessica Glenza, “The Rise and Fall of Corinthian Colleges and the Wake of Debt It Left Behind,” The Guardian, July 28, 2014, https://www.theguardian.com/education/2014/jul/28/corinthian-colleges-for-profit-education-debt-investigation.

- Nancy Stancill, “Trade School Defends Recruiting of Homeless,” Houston Chronicle, May 31, 1989. https://drive.google.com/file/d/0B7adHdBE6w3mbHV2Vi1TLUVDV1k/view?usp=sharing.

- Nancy Stancill, “Doing a Disappearing Act with Students’ Dreams: Texcel Trade Schools Apparently Cheated Thousands,” Houston Chronicle, May 21, 1989. https://drive.google.com/file/d/0B7adHdBE6w3mNUZ4TXhvbDY4ckU/view?usp=sharing.

- Nancy Stancill, “Recruiting for Trade Schools: Promises Mislead the Jobless,” Houston Chronicle, June 11, 1989. https://drive.google.com/file/d/0B7adHdBE6w3mOVc4X1JmdXdrV2s/view?usp=sharing.

- Major metropolitan newspapers that ran series of articles on career school abuses included, in chronological order: the St. Petersburg Times (April 20–22, 1986); Newsday (June 22, 1986); Hartford Courant (November 8, 1987); Arizona Republic (December 13, 1987); the Chicago Sun-Times “Bitter Lessons” series (January 3–8, 1988); Cleveland Plain Dealer (April 24–27, 1988); Los Angeles Times (June 16–17, 1988); and the Houston Chronicle (May 26, 27, June 1, 1989). Cited in Charlotte J. Fraas, “Proprietary Schools and Student Financial Aid Programs: Background and Policy Issues,” Congressional Research Service, 90-427 EPW, August 31, 1990, 21, fn. 33. In 1989, Newsweek financial advice columnist Jane Bryant Quinn also wrote two columns about abuses by for-profit schools; Jane Bryant Quinn, “Schools for Scandal,” Washington Post, April 30, 1989 (the company that owned the Washington Post then owned Newsweek, and Quinn’s column appeared in both publications); and Jane Bryant Quinn, “Shutting Down Scam Schools,” Washington Post, May 7, 1989.

- Abuses in Federal Aid Programs, Senate Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations, Committee on Governmental Affairs, 102nd Cong., 1st Sess., Report 102-58, May 17, 1991, 11–12. https://drive.google.com/file/d/0B7aqIo3eYEUtQzRuX0JCQ3BIT3c/view?usp=sharing.

- Michael Winerip, “Billions for School Are Lost in Fraud, Waste, and Abuse,” New York Times, February 2, 1994. https://drive.google.com/file/d/0B7aqIo3eYEUtTkV4ci05dWozODg/view?usp=sharing.

- Abuses in Federal Aid Programs, Senate Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations, Committee on Governmental Affairs, May 17, 1991, 10. https://drive.google.com/file/d/0B7aqIo3eYEUtQzRuX0JCQ3BIT3c/view?usp=sharing.

- All Republican members who were on the Nunn committee during its hearings approved the committee’s May 1991 report, without dissent. When Senator Nunn later launched a second investigation of career school abuses in 1994, Senator Roth, proceeded to chair the committee hearings and investigation in 1995 after the Democrats lost control of the Senate.

- Ibid.

- James B. Thomas, Jr., Inspector General of the U.S. Department of Education in Hearings on the Reauthorization of the Higher Education Act of 1965: Program Integrity, Subcommittee on Postsecondary Education, House Committee on Education and Labor, 102nd Cong., 1st Sess., Serial No. 102-39, May 29, 1991, 272. https://drive.google.com/file/d/0B7aqIo3eYEUtcnNtaXRhMTI3bXM/view?usp=sharing.

- Ibid., 260–62.

- Kevin Kinser, From Main Street to Wall Street: The Transformation of For-Profit Higher Education: ASHE Higher Education Report 31, no. 5 (Hoboken, N.J.: John Wiley & Son, 2006), 43.

- Ibid., 44.

- Jessica Glenza, “The Rise and Fall of Corinthian Colleges and the Wake of Debt It Left Behind,” The Guardian, July 28, 2014, https://www.theguardian.com/education/2014/jul/28/corinthian-colleges-for-profit-education-debt-investigation.

- Fraas, “Proprietary Schools and Student Financial Aid Programs,” 17. https://drive.google.com/file/d/0B7aqIo3eYEUtTmxZMF9fa2JPb3c/view?usp=sharing.

- “Guaranty Agency Solvency: Can the Government Recover HEAF’s First-Year Liquidation Cost of $212 Million,” Briefing Report to the Chairman, Committee on Labor and Human Resources, U.S. Senate, U.S. General Accounting Office, GAO/HRD-93-12BR, November 13, 1992, 1–6. https://drive.google.com/file/d/0B7aqIo3eYEUtZFhfNDBIS0xjaE0/view?usp=sharing.

- Marge Roukema, “Letter to the Editor: Vocational Schools Train Millions for Life; We Need Regulation,” New York Times, October 6, 1990. https://drive.google.com/file/d/0B7aqIo3eYEUtMHpweE9ZTDluVFU/view?usp=sharing.

- Jason DeParle, “Education; Trade Schools: Defaults and Broken Promises,” New York Times, Aug. 8, 1990. https://drive.google.com/file/d/0B7aqIo3eYEUta1hpaEozdks5aWs/view?usp=sharing.

- Terese Rainwater, “The Rise and Fall of SPRE: A Look at Failed Efforts to Regulate Postsecondary Education in the 1990s,” American Academic 2 (March 2006): 118. https://drive.google.com/file/d/0B7aqIo3eYEUtMUlSeDFWdHFqems/view?usp=sharing.

- Kenneth J. Cooper, “Taking the Stick to Student Loan Losses,” Washington Post, November 12, 1990. https://drive.google.com/file/d/0B7aqIo3eYEUtOVg4a3VpM3JoQlk/view?usp=sharing.

- “Alexander: Obama Administration’s Gainful Employment Regulation ‘Not the Way to Weed Out Bad Actors,’” Press Release, Office of Senator Lamar Alexander, Johnson City, Tennessee, October 30, 2014. http://www.help.senate.gov/chair/newsroom/press/alexander-obama-administrations-gainful-employment-regulation-not-the-way-to-weed-out-bad-actors.

- Reauthorization of the Higher Education Act of 1965, Part 1, Senate Subcommittee on Education, Arts, and Humanities, Senate Labor and Human Resources Committee, 102nd Cong., 1st Sess., S. Hrg. 102-221, Part 1, April 11, 1991, 674, 678. Pressed by Senator Thad Cochrane (R-MS) about “scam schools” that “wouldn’t otherwise exist but for the Federal programs that pay students to attend those schools,” Alexander’s Deputy Secretary Ted Sanders acknowledged that he was “very, very concerned” about for-profit institutions that existed “solely for the purpose of qualifying students for financial aid [and] fix their tuition and costs based upon whatever it is that the combination of Pell grants and loans would actually afford for those institutions.” Ibid., 693–94. https://drive.google.com/file/d/0B7aqIo3eYEUteGhlN3ZGcXpVNUU/view?usp=sharing.

- The report continued, “Conversely, while students and taxpayers have paid dearly, unscrupulous owners, accrediting bodies, lenders, loan servicers, guaranty agencies, and secondary market organizations have profited handsomely, and in some cases, unconscionably.”Abuses in Federal Aid Programs, Senate Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations, Senate Committee on Governmental Affairs, 102nd Cong., 1st Sess., Report 102-58, 6, 33. https://drive.google.com/file/d/0B7aqIo3eYEUtQzRuX0JCQ3BIT3c/view?usp=sharing.

- Kenneth J. Cooper, “Curbing Student Loan Defaults: Senate Panel Proposals Target Abuses at For-Profit Trade Schools,” Washington Post, May 20, 1991, A9 https://drive.google.com/file/d/0B7aqIo3eYEUtMUp3TkNwNDdBaWM/view?usp=sharing; Jason DeParle, “Panel Finds Wide Abuse in Student Loan Program,” New York Times, May 21, 1991. https://drive.google.com/file/d/0B7aqIo3eYEUtZnIxR1NiRVpaN2M/view?usp=sharing.

- Hearings on the Reauthorization of the Higher Education Act of 1965: Program Integrity, Subcommittee on Postsecondary Education, House Committee on Education and Labor, 102nd Cong., 1st Sess., Serial No. 102-39, May 21, 1991, 36, 39. https://drive.google.com/file/d/0B7aqIo3eYEUtcnNtaXRhMTI3bXM/view?usp=sharing.

- See Representative Joseph Kennedy’s testimony in Oversight on Reauthorization of the Higher Education Act of 1965, Senate Committee on Labor and Human Resources, 102nd Cong., 1st Sess., S. Hrg. 102-1196, Boston, Massachusetts, April 3, 1991, 25. https://drive.google.com/file/d/0B7aqIo3eYEUtT2k3QlVoRE1jWnM/view?usp=sharing.

- Hearings on the Reauthorization of the Higher Education Act of 1965: Program Integrity, May 21, 1991, 66. https://drive.google.com/file/d/0B7aqIo3eYEUtcnNtaXRhMTI3bXM/view?usp=sharing.

- Ibid., 75.

- Ibid., 77.

- Ibid., 50.

- Ibid., 53.

- Ibid., 58–61.

- Ibid., 60.

- Ibid., 144.

- Ibid., 219–20.

- Ibid., 9–10.

- Ibid., 428–29.

- Ibid., 428.

- Ibid., 2.

- Ibid., 62.

- Ibid., 10.

- Ibid., 2.

- Abuses in federal student grant programs: Proprietary School Abuses, Hearing before the Senate Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations, Senate Committee on Governmental Affairs, 104th Cong., 1st sess., July 12, 1995, 38. Longanecker went on to reassure Senator Nunn that the Education Department had been able to withstand the pressure from lawmakers over removing for-profit schools from Title IV eligibility. https://drive.google.com/file/d/0B7aqIo3eYEUtazBxMUpPbGxhS1E/view?usp=sharing.

- Jason DeParle, “Trade Schools Near Success as They Lobby for Survival,” New York Times, March 25, 1992. https://drive.google.com/file/d/0B7aqIo3eYEUta2E1akxyTkFqLUE/view?usp=sharing.

- Ibid. Given these bipartisan sympathies, it is no surprise that the for-profit industry’s contributions to lawmakers have often crossed party lines, despite the assumption today that for-profit colleges overwhelmingly favor Republican lawmakers. Through much of the early 1990s, the for-profit sector’s “tradition” was to give “more heavily to Democrats,” as the Chronicle of Higher Education stated in 1994. In the first six months of 1994, the for-profit sector and its employees gave $102,000 to congressional incumbents for the 1994 elections, 72 percent of which went to Democrats. (Jim Zook, “Trade Schools Increased Gifts as House Debated Aid Measure,” Chronicle of Higher Education, September 14, 1994. https://drive.google.com/file/d/0B7aqIo3eYEUtVGRXemxUX3VZTnc/view?usp=sharing) By 2016, the industry’s contributions to candidates had exactly flipped, with 72 percent of contributions in the first eight months of 2016 going to Republicans running for Congress. (Meredith Kolodner, “For-profit colleges stay quietly on offense,” Hechinger Report, Oct. 12, 2016. http://hechingerreport.org/profit-colleges-stay-quietly-offense/).

- In August 1989, Robert Atwell, the head of the American Council of Education (ACE), then the umbrella association of traditional colleges (it now includes for-profit members), floated the idea of separate programs. The concept was supported by the president of the National Association of Independent Colleges and Universities (the trade association for private nonprofit institutions) and many university presidents. Robert H. Atwell, “Accreditation: Putting Our House in Order,” Academe 80, no. 4 (July-August 1994), 10.

- See Stephen Blair’s statement in Thomas J. DeLoughry, “Colleges Prepare for Two-Year Review of Federal Programs in Higher Education,” Chronicle of Higher Education, October 25, 1989, A27. In an opinion piece in the New York Times, DePaul University president Robert Bottoms supported ACE’s proposal to create a separate funding stream for career schools. Bottoms lamented that “When Congress decided to include the profit sector [in the Pell Grant program] back in 1976, who would have believed that in slightly more than a decade, its students would borrow more money than all other college students in the country combined? And at a default rate over four and a half times as great!” (Robert Bottoms, “Sure We Need Beauticians,” New York Times, September 17, 1990, A23. https://drive.google.com/file/d/0B7aqIo3eYEUtM1JQdzY0bGRJTEk/view?usp=sharing) In a Letter to the Editor, Stephen Blair wrote that Bottom’s proposal “belittles the education provided by trade and technical schools and demeans the millions of Americans not college educated who make vital and important contributions to our nation. Mr. Bottoms implies that the two million students who annually attend private trade and technical schools are less important than those who chose elite private colleges and universities.” (Stephen J. Blair, “Letter to the Editor: Vocational Schools Train Millions for Life,” New York Times, October 6, 1990. https://drive.google.com/file/d/0B7aqIo3eYEUtUHpzYnNGaGRBbFk/view?usp=sharing).

- See Michael D. Parsons, Power and Politics: Federal Higher Education Policymaking in the 1990s, 113, 176–77, 183. Sarah Flanagan, an aide to Senator Claiborne Pell (D-RI), chairman of the Subcommittee on Education, Arts and the Humanities told Education Week as early as February 1989 that subcommittee members were “not interested in [Atwell’s] proposal [to create a separate funding stream for proprietary schools]. Most trade schools in this country do a very good job. It’s very easy to take potshots because of the bad publicity of a few schools.” (Mark Walsh, “Cavazos Cautions Trade Schools Over Defaults,” Education Week, February 15, 1989. http://www.edweek.org/ew/articles/1989/02/15/08170045.h08.html?tkn=UOSFvRNp2ZNv%2BpvuJcSKynMTqi5AdpAqF46s).

- Kenneth J. Cooper, “Hill Chairman Wants to Reshape Student Aid; Time Has Come for Major Redesign of Federal Loan and Grant Programs, Rep. Ford Says,” Washington Post, February 4, 1991, A9. https://drive.google.com/file/d/0B7aqIo3eYEUtRmRBdFlPQUYzNm8/view?usp=sharing.

- In his October 21, 1991 letter to Chairman Ford, Secretary Alexander stated at p.3 that he supported “a variation on the provisions [of Ford’s HEA bill, which eliminated accreditation], namely, the elimination of accreditation as an element of institutional eligibility for vocational programs (not just vocational schools) for all HEA programs, and the retention of accreditation as an element of institutional eligibility for collegiate programs. The State role in determining institutional eligibility should be expanded for all programs (not just Title IV programs) and sectors, but with a particular emphasis on vocational programs, which would benefit most from closer oversight.” For coverage of Alexander’s letter, see Thomas J. DeLoughry, “Lawmakers Clash Over Two Versions of Education Bill: House and Senate move closer to passing Higher Education Act,” Chronicle of Higher Education, October 30, 1991. Alexander’s October 21, 1991 letter to Chairman Ford with his recommendation to end accreditation for vocational programs is also summarized in Jeffrey C. Martin, “Recent Developments Concerning Accrediting Agencies in Postsecondary Education,” Law and Contemporary Problems 57, no. 4 (1994): 139. https://drive.google.com/file/d/0B7aqIo3eYEUtY1A4RDA1RmNZNG8/view?usp=sharing.

- Letter from U.S. Secretary of Education Lamar Alexander to Congressman William D. Ford on H.R. 3553, October 21, 1991, Appendix A, 17–18. https://drive.google.com/file/d/0B7adHdBE6w3mM1pWbGp2eDd6UTQ/view?usp=sharing.

- See Richard W. Moore, “The Illusion of Convergence: Federal Study Aid Policy in Community Colleges and Proprietary Schools,” in Community Colleges and Proprietary Schools: Conflict or Convergence? no. 91 (Fall 1995): 89. https://drive.google.com/file/d/0B7aqIo3eYEUtaVhQdEkzdXd5V00/view?usp=sharing Moore writes that “The impetus for [the SPREs] was the increasing misuse of federal aid, particularly by the proprietary sector . . . . Part of the solution was the establishment of the SPREs as a ‘weapon to attack fraud and abuse,’ according to David Longanecker, Assistant Secretary for Postsecondary Education” in the Clinton administration.

- Rainwater, “The Rise and Fall of SPRE,” 107–08, 110. https://drive.google.com/file/d/0B7aqIo3eYEUtMUlSeDFWdHFqems/view?usp=sharing.

- See section 494C(d) of the 1992 HEA Amendments. Cited in “Department of Education, 34 CFR Part 667, State Postsecondary Review Program, Notice of Proposed Rulemaking,” Federal Register 59, no. 15 (January 24, 1994): 3606.

- Department of Education, 34 CFR Part 667, State Postsecondary Review Program, Final regulations,” Federal Register 59, no. 82 (April 29, 1994): 22295, 22306. https://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/FR-1994-04-29/html/94-10147.htm.

- Among the powers granted to states, state education agencies could assess whether tuition and fees were excessive, given the likely earnings for a graduate, for any pre-baccalaureate vocational programs that hit one of the new triggers for state review. Ibid.

- Bush departed from his prepared statement to praise the bipartisan nature of the legislation. See the video of the signing of the legislation at https://www.c-span.org/video/?27351-1/higher-education-act-signing-ceremony.

- A history of career education developed for the Career College Association and the McGraw-Hill Companies Career College Division states that “Taking aim at private career education, the Higher Education Act was reauthorized in July of 1992 with restrictions effectively geared toward restricting the private career sector.” (Imagine America Foundation, In Service to America: Celebrating 165 Years of Career and Professional Education [Washington, D.C., and New York: Career College Association, the McGraw-Hill Companies Career College Division and Studio Montage, 2007], 101, http://imagine-america.org/pdfs/history-book-web.pdf.)

- Congresswoman Maxine Waters, the nemesis of the proprietary school sector, sponsored the amendment to apply an 85-15 requirement to cover Title IV student aid programs. Waters’ amendment passed the House in a voice vote in March 1992 during the floor debate over the House HEA bill. (“Congress Expands College Loan Eligibility,” CQ Almanac 1992, 48th. ed., 438–54.)

- The Higher Education Technical Amendments of 1993 allowed the Secretary of Education to waive the 50 percent eligibility requirements for correspondence courses for “good cause” for an institution that offered a two-year associate-degree or a four-year bachelor’s degree. However, Secretary Riley interpreted the good cause exception narrowly, limiting it to degree-granting programs where students enrolled in the institution’s correspondence courses received no more than five percent of the Title IV HEA program funds received by students at the institution. (“Institutional Eligibility Under the Higher Education Act of 1965, as Amended: Final Regulations” Federal Register 59, no. 82 [April 29, 1994]: 22329.)

- U.S. General Accounting Office, “Student Loan Defaults: Department of Education Limitations in Sanctioning Problem Schools,” Report to the Ranking Minority Member, Subcommittee on Human Resources and Intergovernmental Relations, House Committee on Government Reform and Oversight, GAO/HEHW-95-99, June 1995, 4. https://drive.google.com/file/d/0B7aqIo3eYEUtTDN2SFNUV2dGWnM/view?usp=sharing.

- Imagine America Foundation, In Service to America: Celebrating 165 Years of Career and Professional Education, 103.

- “Reauthorization of 1998 Higher Education Act,” Exec. Summary, Recommendations for reauthorization, Office of Inspector General, U.S. Department of Education, 15, http://www2.ed.gov/about/offices/list/oig/auditrpts/reauth98.html.

- Cited in testimony of Thomas Carter, Deputy Inspector General, U.S. Department of Education in Enforcement of Federal Anti-Fraud Laws in For-Profit Education, Hearing before the House Committee on Education and the Workforce, 109th Cong., 1st sess., Serial No. 109-2, March 1, 2005, 37. https://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/CHRG-109hhrg99773/html/CHRG-109hhrg99773.htm.

- From 1983 to 1992, “95 schools left the [guaranteed] student loan program (either voluntarily or involuntarily) and became exclusively Pell Grant participating schools. In the two years from 1992 to 1994, 509 schools left the loan program and became exclusively Pell Grant schools, a 535 percent increase.” More than half of the 509 schools that switched to Pell-only status in that two-year period , or 271 schools, were for-profit schools. (Abuses in Federal Grant Programs: Proprietary School Abuses, Hearing before the Senate Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations, Committee on Governmental Affairs, 104th Cong., 1st Sess., S. Hrg. 104-477, July 12, 1995, Appendix, Staff Statement, 63.) https://drive.google.com/file/d/0B7aqIo3eYEUtaUJKVGJFQkdVM00/view?usp=sharing.

- Michael Winerip, “Billions for School Are Lost in Fraud, Waste, and Abuse,” New York Times, February 2, 1994.

- Ibid.

- U.S. General Accounting Office, “Higher Education: Ensuring Quality Education from Proprietary Institutions,” GAO/T-HEHS-96-158, June 6, 1996, 2. https://drive.google.com/file/d/0B7aqIo3eYEUtYWJvRklUUFFkbmc/view?usp=sharing.

- See “Trends in Higher Education: Figure 12. Federal Student Loan Default Rates by Sector over Time,” College Board, October 2015, https://trends.collegeboard.org/student-aid/figures-tables/federal-student-loan-default-rates-sector-over-time#Key%20Points.

- During the same time period, 1988 to 1993, the total number of proprietary schools nationwide declined by almost 900 schools, from 4,435 to 3,575 schools. See the testimony of Assistant Secretary for Postsecondary Education David Longanecker in Department of Education Oversight: Gatekeeping, Hearing before the Subcommittee on Human Resources and Intergovernmental Relations, House Committee on Government Reform and Oversight, 104th Cong., 2nd sess., June 6, 1996, 84. https://drive.google.com/file/d/0B7aqIo3eYEUtOHdQb0l6cHc3MnM/view?usp=sharing.