For-profit colleges do not always recruit aggressively; nor do they always shortchange students. But the problem of colleges systematically overpromising and under-delivering, when it does happen, has largely been a for-profit phenomenon. The abuses have been the most widespread and most damaging when they have been fueled by government grants and loans. A cycle has been created: federal money stokes scandals, regulations are adopted in response, the regulations are then relaxed, and the scandals repeat.1

Why do the scandals keep returning? Some regulations have lost their effectiveness over time because the industry finds ways to comply with the letter but not the intent of the rule. In other cases, lawmakers actually relaxed the regulations because the protections worked—as if because it’s dry under the umbrella, the umbrella can be ditched. Usually this occurs after industry lobbyists make the case that the “bad actors” are gone and that regulations should be relaxed to allow for more “innovation.” Corinthian Colleges and ITT Tech both played leading roles in pressing Congress to relax the rules that facilitated their subsequent multi-billion-dollar ripoffs of students and taxpayers.

But were these corporate CEOs bad actors, in the sense that they were evil people who set out to destroy students’ lives? Maybe—but in seeking to prevent further abuses, Congress should assume instead they had no ill will: regardless of intent, the financial incentives in running an education business can easily, and somewhat innocently, drive a business in the wrong direction. After carefully examining the history, my view is that most predatory schools do not start out as scams. Instead, entrepreneurs launch their schools with a plan to do good by doing well—to earn a profit by providing a service. They follow market indicators that in many industries lead to good outcomes for producer and consumer alike.

In education, however, the simplistic and narrow indicators of business “success,” such as growth in the number of paying customers, lead for-profit schools astray, especially when federal aid makes the sales job so easy. Lacking the restrictions and oversight of public and nonprofit entities, the business navigation systems steer them into practices that trample students’ interests.

Despite the clear history and patterns, the current leadership of the Department of Education is distressingly blind to the problem, reversing important consumer protections and failing to enforce those that are on the books. I am hopeful that pressure and actions from Congress can reduce the damage to come, and bring just compensation to those who have been harmed so far.

This report discusses nine of the levers that Congress and the executive branch have used, and should fine-tune and/or reinstate, in order to root out abuses and to steer colleges toward practices and outcomes that are in the best interests of students and taxpayers:

- Require state approval.

- Require accreditation.

- Require market validation of the value of the education (the “90–10 rule”).

- Ban commissions and quotas in recruitment (also known as “incentive compensation”).

- Disallow federal aid to programs with crushing debt burdens (the “gainful employment” rule).

- Cut aid to schools with high loan default rates.

- Protect taxpayer dollars at financially shaky institutions (“financial responsibility” standards).

- Differentiate between public, nonprofit, and for-profit control.

- Provide information to consumers.

Policy 1: Require State Approval

- The state role in federal aid began as a result of scandalous abuses by for-profit schools taking advantage of the post-World War II GI Bill.

- The U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs partners with states as contractors administering GI Bill benefits; however, the state role in Title IV operates differently.

- States frequently have taken action to address abuses before the federal government has done so.

- A heightened state oversight role for Title IV aid was adopted in 1992 but never fully implemented (Congress repealed it in 1995).

Current Status of Federal Program Requirements

For the GI Bill, states have a significant role as front-line decision-makers regarding the eligibility of schools for funds, but their actual authority is murky. The U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) contracts with states that designate an agency (“state approving agencies,” or SAAs) to review programs at institutions to determine their suitability for providing veteran training under the terms of the GI Bill. States are allowed to establish guidelines beyond the minimum federal requirements, and some states have done so. However, the VA does sometimes overrule SAAs.2 And in an apparent effort to undermine the state role in protecting veterans, recent guidance from the VA has threatened to revoke the contracts of SAAs that rescind the eligibility of any school that still has the approval of its accreditor (a private voluntary entity) or a separate state agency that licenses schools, even if the accreditor has placed the institution on probation or has warned the school that it is at risk of losing its accreditation.3 The VA’s policy, if it is sustained, has potentially serious ramifications for veterans and taxpayers, a danger worsened by the fact that some accreditors have been shown to provide ineffective oversight, and cannot themselves always be relied upon to adequately protect students.

For Title IV aid, the institution must be “authorized” by any state in which it has a physical presence. That means that, at minimum, there must be an entity responsible for handling consumer complaints, and that the state is able to revoke a school’s authorization if it chooses to do so. Because the Higher Education Act (HEA) requires state authorization, state-level consumer protections that go beyond federal rules are generally not preempted by the HEA.

The rules regarding state oversight of online programs participating in the Title IV program are in dispute. On July 1, 2017, regulations went into effect stating that to enroll online students using Title IV aid, the student’s state of residence must have a complaint process available to the student, either directly or through a reciprocity agreement with the online program’s state of residence. On July 3, 2017, U.S. Secretary of Education Betsy DeVos published a notice in the Federal Register announcing that these online rules would be delayed until July 2020. The legality of the delay is being challenged in court.4

For the GI Bill, each program is subject to approval or disapproval. For Title IV grants and loans, the federal government looks to whether the institution is authorized by the state (though some states also approve individual programs).

Background and History

The 1944 GI Bill is rightly remembered as one of the most effective social policy programs in U.S. history. Thanks to the GI Bill, millions of soldiers returning from World War II had the opportunity to enroll in college or job-training programs, and had access to low-interest loans to use in buying homes. What has been largely forgotten, however, is that the GI Bill also led to systematic abuses at the hands of for-profit schools—schools that sprang up to take advantage of what was essentially a government educational voucher with no strings attached.5

What has been largely forgotten is that the GI Bill also led to systematic abuses at the hands of for-profit schools—schools that sprang up to take advantage of what was essentially a government educational voucher with no strings attached.

The 1944 GI Bill called on states to assist with the approval of programs suitable for veteran enrollment. However, the states, which had not previously experienced such a flood of schools and programs requiring review, were not up to the task and had little guidance for how to differentiate good from bad programs. The system of VA funding for SAAs, which is still used today, grew out of this initial experience.6

The original HEA in 1965 required state authorization, as it does today; but it also took a creative, risk-sharing approach to state involvement in the student loan program. Under the new law’s guaranteed student loan program, states and charities would administer the program, putting in some of their own funds to incentivize state and local-level decisions about the schools and students that deserve support, and under what terms. The state oversight role never really took hold, though. Instead, Congress sweetened the deal, until eventually the federal program became a money-making operation for the states and other guarantee agencies, undermining the gatekeeper role the risk-sharing was designed to produce.7 (The guarantee system was eliminated in favor of the direct loan program in 2010.)

For a brief moment in the 1990s, the Title IV program included a more robust federal–state partnership aimed at preventing fraud and abuse. Conceived by the George H. W. Bush administration as one response to the student loan scandals of the 1980s and early 1990s, state postsecondary review entities (SPREs) were established in the 1992 reauthorization of the HEA. Financed by the federal government, the SPREs were tasked with conducting reviews of institutions in their states that hit certain triggers, such as heavy use of federal aid or high default rates.8 The SPREs were eliminated, however, before they even got off the ground, having fallen in the crosshairs of then-new speaker of the house Newt Gingrich in 1995.

In 2007, California’s authorization agency closed after Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger and the legislature could not agree on the scope of its powers. The U.S. Department of Education issued an opinion that state authorization was not necessary for schools in California to continue to be eligible for Title IV aid. Rules later adopted by the Obama administration reversed this policy, clarifying the expectations for valid state authorization.

Recommendations

The state role in providing oversight of institutions using the GI Bill and Title IV aid should be continued and enhanced.

Policy 2: Require Accreditation

- Accreditors do not have a strong track record in consumer protection because they are self-regulating entities and they lack the law enforcement powers that would be necessary for them to investigate and prevent abuses.

- Deferring to accreditors on issues of academic quality has helped to protect academic freedom and prevent federal meddling in curricula.

Current Status of Federal Program Requirements

For the GI Bill, accreditation is not required, but SAAs may consider accreditation in approving a school’s programs. For Title IV aid, accreditation by an agency recognized by the secretary of education is required. To be recognized, the agencies are required to undertake particular types of reviews and procedures.

Background and History

Accreditation has not always been necessary to prevent scandal in major federal student aid programs. At its peak, the nation’s first such program, which ran from 1934 to 1943, aided one in eight college students at nearly all of the nation’s public and nonprofit institutions.9 Yet even without an accreditation requirement, the historical record reveals no indication of any widespread abuses. The scandals arrived a dozen years later, with the next version of federal aid, the first GI Bill, which offered funding to for-profit school operators in addition to public and nonprofit schools.

Beginning with the 1952 GI Bill for Korean War veterans, and repeated in dozens of subsequent federal student aid statutes, Congress required the U.S. commissioner of education, then the nation’s top-ranking federal education official, to publish a list of agencies and associations deemed to be “reliable authorities” on the quality of training offered by an educational institution. The approving agencies in each state and the VA could, in turn, rely on the judgments of these private groups to determine which institutions were worthy of training veterans eligible for the GI Bill. Deferring to accrediting agencies seemed like a convenient, low-cost solution that kept the government out of the business of directly setting quality standards.10

Preventing the federal government from invading academic freedom, or getting involved in debates about curricula, may be the most important enduring benefit of the federal deference to accrediting bodies.

Initially, most for-profit schools were not accredited. However, it did not take long for predatory schools to find ways to claim accreditation. As Terrel Bell, the U.S. commissioner of education in the Nixon and Ford administrations and Ronald Reagan’s first secretary of education, later summed it up: “Some of the associations were creatures of the owners, and their policies were established in a self-serving way, so that the institutions could qualify for federal assistance.”11 One accreditor that Bell’s office had grappled with in 1973 was none other than ACICS, then known as the Association of Independent Colleges and Schools (AICS). In transgressions that are eerily similar to the agency’s recent scandals, thirteen AICS schools had closed “without delivering the educational services for which a large number of student borrowers have paid in advance from proceeds of federally insured student loans.”12

Escalating student loan default rates and evidence of abuses in the 1980s led to an extensive investigation by the Senate Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations, led by Democratic senator Sam Nunn (GA) and his Republican vice-chair William Roth (DE). They found traditional accreditation for for-profit schools to be severely mismatched. The self-regulatory approach, they concluded:

is simply not suited to the structure and operations of proprietary schools. The accreditation approach is based almost entirely on principles and assumptions developed over the course of many years for traditional two- and four-year colleges and universities. For-profit, business considerations in proprietary school operations were neither part of this traditional approach, nor was it contemplated that they would be included.

The traditional approach assumes that those involved are educators, whose basic concern is not profit, but the welfare of their students, and who can be counted upon to be honest and truthful in all facets of accreditation. It does not recognize certain significant differences between colleges and universities and proprietary trade schools.13

In its recommendations, the subcommittee insisted that:

Prior to the commitment of federal funds for student aid, the Department of Education must require strict and credible assurance that recipient institutions provide the students with a quality education. The accrediting bodies recognized by the Secretary of Education, especially in the area of proprietary schools, have to date failed to provide that assurance. Either those bodies, under the leadership of the Department, must dramatically improve their ability to screen out substandard schools, or the government should cease to rely on them in authorizing a school’s participation in federal student aid programs.14

Following on the Nunn–Roth investigation, the 1992 HEA reauthorization established a number of requirements on accreditor standards and procedures. Later reauthorizations further refined the requirements for the federal recognition of accreditors.

In the 2000s and 2010s, accrediting agencies failed to stop rampant abuses. ACICS was among the worst, and Secretary John B. King Jr. ultimately revoked its federal recognition, sending a strong message to accrediting agencies about their need to be vigilant and responsive to leading indicators of fraud abuse. Secretary DeVos, however, reversed that decision, sending the opposite message: accreditors will not be held accountable.

In a further retreat, the department is moving forward on a rulemaking that represents an unprecedented “unraveling of federal oversight of college quality,” according to experts.15 If the rules are ultimately adopted, they will:

- lead to fast-track recognition of new accrediting agencies, as well as less rigorous and less transparent approval of agreements between colleges and private companies that provide online classes;

- allow schools that are in violation of accreditor standards to retain their eligibility for federal aid for up to four years; and

- allow for a fraudulent school’s accreditation to be purchased while leaving most liabilities with the likely-bankrupt former owner.

Recommendations

In completing their investigation of abuses in 1991, Senators Nunn and Roth said that if the accrediting bodies prove themselves unable to rein in predatory for-profit schools, Congress should stop pretending that a self-regulatory approach fits the for-profit model.

In order to decrease these agencies’ chances of again failing the Nunn and Roth challenge, Congress should prohibit for-profit owners and executives from serving on their accrediting agency governing boards—something which New York Governor Andrew Cuomo has proposed.16 Ensuring educational quality often involves choosing a route that is not financially remunerative: providing more financial aid to low-income students, hiring full-time faculty instead of adjuncts, and advising consumers about other schools that might better fit their interests, among other practices. Accreditors must be able to push schools to do what’s right for students and their communities, requiring decisions that are at odds with investor interests.

Accrediting agencies that focus on career training, particularly those that cater to for-profit schools, should shift their boards to be composed not of school officials but instead of employers and others who can reliably vouch for the quality of the training.

Policy 3: Require Market Validation of the Value of the Education

- Predatory schools have a history of pricing their programs to maximize the amount of grant and student loan funds that will accrue to the school.

- When the government is funding nearly every student, it is likely propping up a school that is not worth the tuition price.

- Both the GI Bill and Title IV include provisions aimed at validating the market value of a school, but loopholes in those provisions are undermining their effectiveness.

Current Status of Federal Program Requirements

The GI Bill law requires schools to stop the process of enrolling new veterans in a program if 85 percent of the students in the program are already paying the program’s tuition using the GI Bill. There are some exceptions to the requirement, including a provision allowing the secretary of the VA to waive it in particular circumstances.17

Under the HEA, for-profit schools that collect more than 90 percent of their tuition revenue from Title IV aid are essentially put on probation for two years.18 If the school crosses the 90 percent threshold two years in a row, the school loses access to federal aid altogether for a period of at least two years.

Background and History

When a product or service is paid for by a government program, some attempt is nearly always made to protect against taxpayers being overcharged: for example, competitive bidding in defense contracts, payment schedules in Medicare based on market prices, or requiring purchase from a store where other consumers shop (i.e., the government shouldn’t pay more for a hammer than other consumers pay at the same hardware store).

The initial versions of both the GI Bill and Title IV aid did not have any such protection. After the enactment of the 1944 GI Bill, opportunistic entrepreneurs established schools and set their tuition rates at the maximum amount that the VA would pay. Many schools falsified their expenditure data and attendance records, overcharged for supplies, and billed the VA for students who were not even enrolled, all in order to tap taxpayers for every penny they could get.19

Many schools falsified their expenditure data and attendance records, overcharged for supplies, and billed the VA for students who were not even enrolled, all in order to tap taxpayers for every penny they could get.

For the Korean-era GI Bill, Congress added the 85–15 requirement as a quality check, a policy which was continued into the Vietnam era and beyond. For a period, the Vietnam version of the GI Bill counted any federal grant aid, including Title IV, in the 85 percent. The policy was challenged but ultimately affirmed by the Supreme Court, which upheld the rule as “a way of protecting veterans by allowing the free market mechanism to operate . . . minimiz[ing] the risk that veterans’ benefits would be wasted on educational programs of little value.”20

In 1992, in response to scandals in the student loan program, Congress adopted an 85 percent cap on the percent of revenue that could come from Title IV aid. At the time, veterans’ aid was not a major component of college enrollment, so the fact that it did not include veterans’ aid was not a major loophole. Actually, the provision may be one reason the University of Phoenix’s quality was not at issue in its first decade of growth: the company’s focus on employers that supported more than 40 percent of its students prevented the school from promoting low-value programs at high tuition prices.21

In 1998, Congress raised the threshold to 90 percent. In 2008, Congress further weakened the rule by applying it only to schools that exceed 90 percent two years in a row. The relaxed requirements allowed for more rapid growth at the lower quality schools, according to Brookings Institution research.22

In the 2000s, the Iraq and Afghanistan wars created a steady stream of veterans whose GI Bill funds could count toward the 10 percent. The result has been an aggressive pursuit of veterans by predatory schools. Of the ten colleges charging taxpayers the most overall post-9/11 GI Bill tuition and fee payments from fiscal years 2009–17—totaling $5.4 billion—seven spent less than one-third of students’ gross tuition and fees on instruction in 2017 and struggled with outcomes, and only half (52 percent) of their students earned more than a high school graduate.23

If not for the failure of the current 85–15 and 90–10 rules to account for other federal aid, veterans would not be abused in such high numbers by predatory schools, and the damage done by irresponsible growth and poor quality programs, which have enrolled hundreds of thousands of students in recent years, would be far less severe.

Recommendations

Returning to an 85 percent cap for Title IV eligibility, and including all types of federal aid in the calculation, would go a long way toward protecting veterans and other students from being aggressively recruited for fraudulent programs.24 The GI Bill cap, too, could be adjusted to account for students using all types of federal aid.

Policy 4: Ban Commissions and Quotas in College Recruiting

- Commission-paid or quota-driven college advising encourages predatory recruiting tactics.

- The Higher Education Act prohibits the use of incentive compensation, but current enforcement under Secretary DeVos is uncertain.

- Loopholes in the current ban threaten to undermine its effectiveness.

Current Status of Federal Program Requirements

The HEA prohibits institutions the use of Title IV aid for providing “any commission, bonus, or other incentive payment based directly or indirectly on success in securing enrollments or financial aid to any persons or entities engaged in any student recruiting or admission activities or in making decisions regarding the award of student financial assistance.”25 The GI Bill law includes a similar provision.26 In the Title IV law an exception is made for recruiting foreign students, and additional clarifications are made in the Department of Education’s regulations.27

Further guidance provided by the Department of Education declares that colleges can pay contractors a percentage of tuition for their recruitment activities if those activities are bundled along with other services, such as operating the college’s platform for online courses.28

Background and History

Sales quotas and commissions, or similar practices, are a central element of most predatory college scams, including Trump University.29 Incentivizing advisors to do whatever is necessary to make a sale is a way of getting employees to use psychological tricks or shade the truth to enroll students, without the company getting its hands dirty. Then, when unethical or illegal tactics are revealed to regulators or law enforcement, the company can claim ignorance, blaming the problems on rogue employees or contractors.

In response to the 1980s student loan scandals, several officials, including Senator Bob Dole (R-KS) and then-secretary of education Lamar Alexander, proposed prohibiting schools using federal aid from using any “commission, bonus, or other incentive payment” to secure enrollments. The ban was adopted as part of the 1992 reauthorization of the Higher Education Act.

In 2001, ITT Tech, claiming that its predatory abuses were all in the past, hired a powerful lobbying firm to seek changes that would weaken the incentive compensation ban.30 Despite warnings from counselor and consumer groups, the George W. Bush administration plowed forward with the industry request, adopting regulations that created loopholes in the law, and promising only small sanctions for any violation.31 With relaxed oversight, ITT Tech reverted into a company where, according to a former executive, “students were viewed as potential sales targets” and every employee was threatened with termination if they did not meet recruitment quotas.32

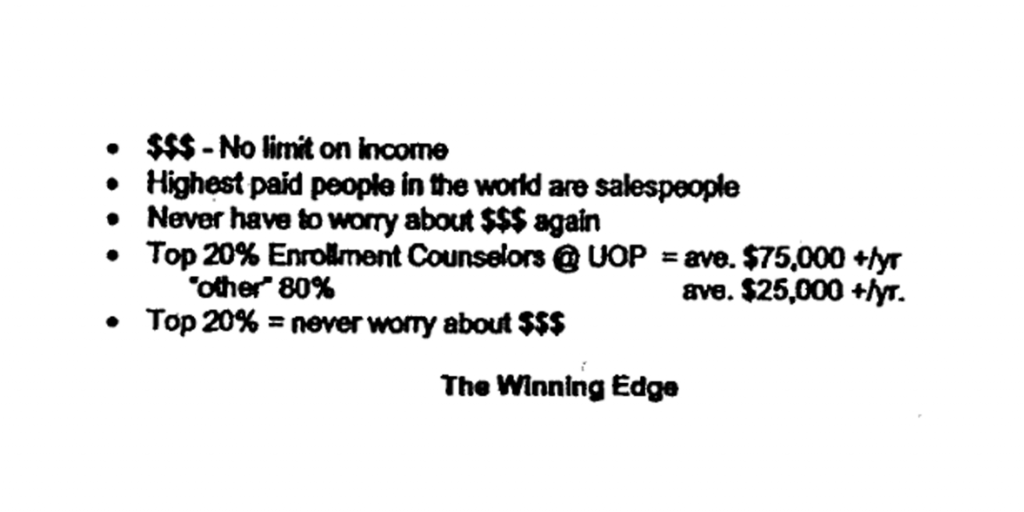

Tempted by the loopholes, schools revved up the recruitment engine, promising high salaries to enrollment advisors not with a background in education but instead with experience in sales. The University of Phoenix was particularly aggressive in its expansion efforts, serving as a model that other schools emulated. An audit by career staff at the Department of Education found the company was operating in a “duplicitous manner” to evade the ban, with employees told that “heads were on the chopping block” if enrollment numbers were not reached.33 A University of Phoenix ad for counselors, shown below, openly admitted that the job was about sales.

Figure 1

After promising to reform its practices, another review just four years later found that Phoenix had again violated the ban.34 The promise of weak enforcement had prompted many for-profit colleges to test the boundaries of the restriction on incentive compensation,35 contributing to an explosion of abuses that peaked in the recession.

The Obama administration reversed these Bush administration policies, and worked with the Department of Justice to support several whistleblower lawsuits that alleged violations of the incentive compensation ban.36 Despite evidence of violations,37 the Trump administration has not announced any enforcement actions.

The incentive compensation rule, when enforced, has been an extremely important measure in preventing some of the worst abuses. However, loopholes and lax enforcement are threatening its effectiveness. That the department’s 2011 sub-regulatory guidance allowed “bundled services” providers to be paid incentive compensation, even though their services include recruitment, has proven to be problematic. Contracted recruiting operations, packaged in bundles, have become a big business, with some taking as much as 60 percent of tuition, elevating the cost of online education.38

Recommendations

Bundled service providers, being paid a large percentage of tuition, are recreating the hazards of incentive-paid recruiters at contractor operations off-campus. To reduce the cost of online education and prevent predatory recruiting, the Department of Education should revise the 2011 guidance to remove the bundled services provision as inconsistent with the HEA prohibition.

Policy 5: Disallow Federal Aid to Programs with Crushing Debt Burdens

- Congress allowed for-profit participation in Title IV only for programs that paid off financially for students: i.e., programs that led to “gainful employment” (GE). However, no regulatory standard was established to define what constituted “gainful employment.”

- The Obama administration worked to correct this defect by establishing specific debt and earning standards for these gainful employment programs.

- The Trump administration is failing to implement the GE rule, and has proposed repealing the regulations.

Current Status of Federal Program Requirements

To be eligible for Title IV, all programs at for-profit schools and certificate programs at public and nonprofit schools must prepare students for “gainful employment in a recognized occupation.” Regulations stipulate that a program passes unless more than half of its graduates on federal aid have excessive student loan debt burdens when weighed against their incomes after completing school.39 The regulation also required certain information to be provided to prospective students regarding program outcomes.

The rule was scheduled to begin having consequences in July 2017, with some programs losing access to Title IV, and some that would need to alert students of the high debt levels given the expected salaries. The Department of Education, however, delayed the reporting requirements, and gave schools more time to appeal the department’s findings regarding graduates’ earnings. A group of state attorneys general has since challenged the department’s delay in enforcing the rule.40 Meanwhile, Secretary DeVos has proposed repealing the rule; a final decision is expected soon.41

Background and History

As enacted in 1965, the Higher Education Act did not allow for-profit schools to participate at all in the Title IV program. Congress was well aware of the hazards of for-profit schools because of their abuses of the post-World War II GI Bill, so Congress instead created a separate, capped fund to support specific programs (such as nurse training, or electrician training) if it successfully prepared students for gainful employment in a specific type of job. While supporting colleges generally was part of the purpose of the HEA, the National Vocational Student Loan Insurance Act of 1965 was necessarily more specific about what was expected from the school because of the inclusion of for-profit providers.

Later, the vocational bill was folded into the HEA, still stipulating that funding be based on the programs successfully preparing students for gainful employment in a recognized occupation. Congress did not define precisely what the GE term meant, and the Department of Education left it undefined as well. In practice, if a school told the agency that its program was somehow related to a job, and if the accreditor did not challenge that assertion, the program became eligible for federal grants and loans.

The intent of the congressional requirement was thoroughly undermined: students would borrow tens of thousands of dollars to enroll in career training programs they believed would lead to a job that would repay their loans, only to discover—and too late—that they now had unmanageable debt with no return on investment.

In effect, the intent of the congressional requirement was thoroughly undermined: students would borrow tens of thousands of dollars to enroll in career training programs they believed would lead to a job that would repay their loans, only to discover—and too late—that they now had unmanageable debt with no return on investment. In an effort to address this problem, the department engaged experts and stakeholders over the course of several years to develop the “gainful employment” regulation, finalized in 2014. The GE rule was an effort to measure career education programs’ performance in “prepar[ing] students for gainful employment in a recognized occupation,” and to prevent programs that leave students with debt and no means to pay it back from continuing to receive federal financial aid.

The rule is targeted and fair, not broad or draconian. Based on the single year of data released by the department, at a majority of for-profit schools, all of the programs passed.42 At the rest of the schools, particular programs needed improvement. Companies reported that the rule led them to reduce tuition or cut program lengths to come into compliance, exactly the sort of pro-student changes that were intended.

Recommendations

Despite the GE rule’s positive impact for students and for taxpayers—and for quality for-profit schools—the Trump administration and education secretary Betsy DeVos have proposed to rescind the rule completely, leaving the schools’ programs free to continue enrolling students in low-quality programs without being held accountable for their poor performance.43 The department’s own official budget estimates that eliminating the gainful employment rule will cost taxpayers $5.3 billion in financial aid because of increased spending on programs that fail to meet established standards.44

Congress has an opportunity to stop this deregulation by codifying meaningful rules defining gainful employment for the purposes of receiving Title IV aid.

Policy 6: Cut Off Aid to Schools with High Loan Default Rates

- The cohort default rate was a very effective tool in eliminating problem schools from accessing federal aid in the early 1990s.

- This three-year measure is still useful. However, due to gaming by institutions, it is not as meaningful as it used to be.

Current Status of Federal Program Requirements

The cohort default rate is an annual measure of the percentage of a school’s borrowers who have defaulted on their loans within three years of leaving school. A school loses its Title IV eligibility if more than 40 percent of a single cohort—all of the students who have loans and stopped attending the school in a particular year—default, or if more than 30 percent default in three consecutive cohorts.

Background and History

When Congress first decided to cut off federal aid to schools with high default rates in 1992, it did so because such a default rate was a strong indicator of a predatory school. Former students who were not making enough money to repay their loans, or who felt they were poorly treated or misled, would default, producing a high default rate associated with the school.

The idea behind the default rate cutoff was that schools at risk of hitting the maximum would have a strong incentive to make their recruiting more honest, their pricing more fair, their offerings better targeted for good jobs, and/or their instruction and student support more robust.

Predatory schools, however, rather than improving their education offerings in response to a high default rate, discovered that they could avoid the feared reduction in profitability that would come from improving their offerings—whether the fear was justified or not—by instead manipulating the default rates more directly. By monitoring former students’ loans and filing paperwork for them, they could ensure that students that receive little value from the education they receive and earn too little to repay their loans enter temporary forbearance instead of the default that was originally viewed as an indicator of poor school quality.45 The practice has become so common that I have found that some school leaders misunderstand the purpose of the default rate cutoff itself, believing it exists to spur them to put resources into what is euphemistically called “loan counseling.”

Because the original two-year default rate was so undermined by gaming on the part of schools and by other changes in the HEA’s default definition, Congress in 2008 changed the rule to a three-year measure using revised definitions (and changed the threshold to 30 percent from 25 percent).46 But the manipulation to keep the rate temporarily lower was simply extended to the third year. A Center for American Progress analysis of default rate manipulation found that defaults spike dramatically after the regulatory snapshot at the three-year point.47 A New York Times op-ed by the study’s author includes the telling chart, which you can view below.

Figure 2

Recommendations

The cohort default rate is not completely meaningless: a high rate at a school where a large proportion of students borrow is a major red flag. However, a low rate is not the green flag it used to be. Going forward, Congress should retain the cohort default rate as an indicator but expand the criteria so that they include other signs of borrowers who are struggling, such as high rates of the use of forbearance.

Policy 7: Protect Taxpayer Dollars at Financially Shaky Institutions

- The Higher Education Act requires that schools have the financial wherewithal to manage federal funds responsibly.

- Theoretically, “financial responsibility” formulae developed by the Department of Education would protect against calamitous closures that saddle taxpayers or students with liabilities.

- Numerous unanticipated school closures, particularly at for-profit institutions, are evidence that the current financial responsibility standards are not adequate.48

Current Status of Federal Program Requirements

The Higher Education Act requires schools receiving Title IV funds to demonstrate that they are not fly-by-night shell companies, but rather financially responsible entities with adequate asset reserves, cash flow, and so forth in order to receive and administer Title IV funds. Public institutions that are backed by the full faith and credit of the federal government are then assumed to be financially safe for the investment of federal funds. For-profit and nonprofit institutions that participate in the federal student aid programs are required to meet a set of tests of financial health before they can begin receiving aid, and then periodically after the aid delivery has begun. These tests essentially measure three ratios: a primary reserve ratio, an equity ratio, and a net income ratio. After computing all three ratios, a composite score is derived that reflects the overall relative financial health of the institution.49

Institutions with low scores are subject to additional oversight, including greater attention to the amount of funding they are drawing from the U.S. Treasury. In some cases, schools may be required to post a letter of credit, essentially a bond that sets aside funds that would be available to compensate the federal government even in the case of bankruptcy.

Background and History

The 1992 reauthorization of the HEA required the department to develop regulations to determine the financial responsibility of institutions participating in Title IV. Initial regulations were adopted in 1994. Today’s general approach was adopted in 1997, based on recommendations from a study commissioned by an accounting firm.50

The formulas and consequences, and the way they have been implemented, have been criticized for being inadequate to prevent precipitous closures or to provide adequate compensation when closures occur. The abrupt and harmful closure of a number of schools support that criticism:

- From 2006 to 2010, schools owned by Corinthian Colleges grew rapidly, fueled largely by federal student loans and grants.51 In the wake of evidence that the school was systematically misleading consumers, the chain collapsed, leaving students and taxpayers with enormous liabilities and harm.52 The company’s financial responsibility scores provided no warning. Corinthian produced passing financial responsibility scores through 2010, while enrollment was growing.53

- Westwood College, now closed, was in the top financial-score range for each of the eight years for which data are available.

- ITT Tech, now closed, had passing financial responsibility status for eight of the nine years for which data are available.

- EDMC’s Art Institutes, currently collapsing after a sale, had passing scores in eight of the nine years for which data are available.

- Globe University had passing scores for eight of the nine years before its closure.

Despite the poor track record of the financial responsibility ratios in identifying financially precarious institutions, a joint regulatory effort by many states, focused on online education, uses the measures as its primary consumer protection tool.54

In 2016, a new policy set out to create “borrower defense” regulations by linking the financial responsibility rules with reporting on liabilities stemming from consumer fraud suits.55 A school may have great cash flow one day—while it grows enrollment based on false promises—and face bankruptcy the next, once those deceptions are revealed. In these instances, more effective early warning signs may come from reports of arbitration activity and consumer litigation. The borrower defense rules require reporting on both arbitration and litigation indicators, but both warnings systems are in jeopardy in the face of Secretary DeVos’s efforts to rewrite the rule.56

Recommendations

The financial responsibility triggers established by the 2016 borrower defense regulation should be implemented.

Federal and state regulators, and accreditors, should be cautious about relying too heavily on the financial responsibility ratios for oversight or early warning purposes.

Policy 8: Differentiate Public, Nonprofit, and For-Profit Colleges

- Public and nonprofit control of institutions have proven to be powerful consumer protection tools that provide useful, simple indicators for consumers.

- The collapse of the Internal Revenue Service (IRS)’s oversight of nonprofit status has led some for-profit operators to claim to be nonprofit while failing to adopt the requisite financial controls.

- Restoring the integrity of public and nonprofit status is critical to protecting consumer and taxpayer interests.

Current Status of Federal Program Requirements

Under federal and state laws, for-profit entities are subject to far more lenient financial controls and oversight than are public or nonprofit entities. Those differences explain for-profit schools’ greater inclination to take unfair advantage of students or taxpayers. Rather than exclude for-profits completely from Title IV on this basis, the HEA attempts to account for the greater hazards by imposing some compensating additional requirements on for-profit schools. These include the 90–10 rule, ineligibility for aid during pre-accreditation, and broader coverage of the gainful employment rule, as discussed above.57

The HEA defines a nonprofit institution as a corporation or association “no part of the net earnings of which inures, or may lawfully inure, to the benefit of any private shareholder or individual.”58 While there is no definition of a “public” institution in the HEA, the law effectively creates one by allowing the secretary of education to exempt from the financial responsibility standards an institution that “has its liabilities backed by the full faith and credit of a State, or its equivalent.”59

In the past, the Internal Revenue Service did a respectable job of policing nonprofit status, so the Department of Education could rely on its determinations. However, in recent years, the IRS enforcement operation has been virtually eliminated, undermining the integrity of nonprofit status in the United States.60

Background and History

Rampant deceptive or unfair treatment of students is rare at legitimate nonprofit and public colleges because financial restrictions make it difficult for school leaders to profit from bad behavior. Being a nonprofit has traditionally required an institution to devote all of its revenues to its educational purpose, and prohibit any form of profit-taking, so that those in control are not tempted to take advantage of students or the public.

Table 1

| Regulatory Differences Define Whether an Entity Is Public, Nonprofit, or For-Profit | |||

| Public | Nonprofit | For-Profit | |

| Who is responsible for governing the institutions, including setting tuition rates and budgets? | Elected and appointed state officials | Trustees | Owners |

| What are they allowed to spend money on? | Education or another public purpose | Education or a charitable purpose | Anything, including distributions of profit for owners |

| Can top-level decision-makers personally profit from the operations of the institutions? | Generally no | Generally no | Yes |

| Do colleges have access to equity markets to invest and expand? | No | No | Yes |

| Is there a financial backstop if something goes wrong and the college is bankrupt? | Taxpayers | No | No |

| Source: The Century Foundation | |||

Restrictions on public and nonprofit institutions have been so effective in protecting students that state and federal laws frequently provide funding only to them, or apply stricter guidelines if for-profit colleges seek access to taxpayer funds.

Because of the reputational benefits of claiming to be nonprofit, and the differing regulations, some for-profit operators have sought ways to claim nonprofit status while not actually adopting the financial restrictions that protect consumers. The decline in IRS enforcement is increasingly allowing these covert for-profit entities to operate, fooling consumers and threatening the integrity and reputation of nonprofit institutions.

More recently, cracks have appeared in the integrity of the “public” label as well.61

Recommendations

With the labels of “nonprofit” and “public” becoming less reliable, one instinct is to abandon the distinctions. But doing so would be like repealing an effective regulation because of a debilitating loophole. The right response, given the demonstrated value of valid nonprofit and public control, is to close the loopholes. Congress can restore the integrity of public and nonprofit status by establishing review procedures for conversions of for-profit institutions, as well as practicing more robust oversight of nonprofit and public institutions that have conflicts of interest in their governance.

Policy 9: Provide Consumers with Information

- Eligibility for federal aid is used by schools to overcome consumers’ doubts or suspicions about the school’s legitimacy or quality.

- In contrast, the vast information and data about a school is difficult for prospective students to analyze, leaving them to rely on counselors’ advice.

- Replacing responsible regulation with consumer information will not adequately protect consumer or taxpayer interests.

Current Status of Federal Program Requirements

When a school can say it is “approved for the GI Bill” or “approved for Pell Grants,” the endorsement is specific, simple information with enormous power to recruit students and overcome any doubts or suspicions they may have about a school. Federal aid is a powerful recruitment tool, apart from just the money itself, especially for schools that are not name brands. The responsibilities that the HEA places on schools are hardly commensurate with the benefits that they get from the federal endorsement. Institutions are required to provide “adequate” counseling to prospective students,62 and to “act with the competency and integrity necessary to qualify as a fiduciary [of the Department of Education] . . . in accordance with the highest standard of care and diligence.”63 The department also requires schools to make available various types of specific information on their web sites or in school catalogs, and data is submitted that the department makes available on College Navigator and the College Scorecard. The VA, meanwhile, operates a GI Bill Comparison Tool that includes information about veterans complaints, and has caution flags when colleges are facing heightened regulatory scrutiny.64

Recent regulations have required schools to make specific disclosures to students, though some have not been implemented. The GE rule requires schools to disclose to prospective students certain facts about their career programs. The requirement has been delayed until July 1, 2019 (and the department has proposed repealing the rule).65 A new requirement under the 2016 Obama administration’s borrower defense rule requires for-profit schools with low loan repayment rates to include a warning in their promotional materials.66 New rules (also delayed) relating to online education across state borders include requiring individualized warnings that a program does not meet state professional licensing requirements or prerequisites, as well as warnings regarding any loss of accreditation or state approval.67

Background and History

Legally, schools approved for access to Title IV funds have a responsibility, as noted above, to counsel students adequately and to protect the interests of taxpayers. Those vague general requirements, however, are no match for a predatory school’s drive to maximize its enrollment of students who use federal aid. The first weapon in the school’s arsenal is the federal aid itself: for example, the parent of an ITT Tech student says school officials told her daughter that “since the government sponsored the loan, the education it bought would be great. After all, the government doesn’t make loans for homes that are about to fall down.”68 The Federal Trade Commission cited this problem of implied government endorsement in its major study years ago: “[I]n claiming that the school is ‘approved’ for VA training, or ‘approved under the GI Bill,’” schools “use the aura of the federal stamp of approval.”69

It is against that backdrop of a federal stamp of approval that Secretary of Education Betsy DeVos wants to eliminate school responsibility and federal oversight in favor of an “informed choice” scheme. Her perspective is that borrowers who feel they were defrauded in fact just “regret the choices they made,” and that the solution is to be sure that when students borrow “they have explored their options carefully and weighed the available information to make an informed choice.”70 Previously, Republicans have rejected this simplistic thinking. In the wake of rising defaults after the expansion of federal loan programs in the 1970s, the Nixon administration created an interagency committee to examine the problem and propose solutions.71 The committee found that the government, as financier, has a responsibility to the student made necessary by the consumer’s “educational inexperience coupled with the expensive and intangible nature of the services he is purchasing, and in light of the potential for consumer abuse in ‘future service contracts’ used by most schools.” When these rights are not respected, the student should be protected and should have redress mechanisms available to them.72

In a recent review of relevant research, seven leading economists who specialize in education found that “information provision alone is not enough to alter the enrollment choices of less-resourced students,” nor is requiring the provision of information adequate to “incentivize higher performance among institutions.” For example, they point to research showing that the launch of College Scorecard, a federal consumer information resource, had “no impact . . . on the college applications of students in less-affluent high schools, those with lower levels of parental education, and underserved minority groups.”73

Because of the complexity involved, most prospective students ultimately rely not just on data they have been provided, but on recommendations from people they feel are more knowledgeable than they are.

Because of the complexity involved, most prospective students ultimately rely not just on data they have been provided, but on recommendations from people they feel are more knowledgeable than they are. When those people are recruiters posing as advisors, they can easily use known psychological tricks to gloss over any inconvenient disclosure. The Federal Trade Commission cited how a school’s low job placement rate can be dismissed by putting the onus on the prospective student: “Of course, no school—not even ICS—can guarantee you a better job. We can’t make you smarter than you already are, and we can’t make you ambitious if you’re lazy.”74 DeVry University trained its recruiters to use the same tactic to move past students’ doubts: “Replace the fear of trying with a greater fear of not succeeding.”75

Stop the Repeating Cycle

Schools that are operated as for-profit businesses can provide a quality education at a fair price, respecting their students’ needs and legal rights and counseling prospective students honestly and responsibly. Unfortunately, when federal entitlements are the source of funding, for-profit schools frequently trample students’ interests instead. Called to task, the companies sue, claiming a property right to a continuing flow of tax dollars into their coffers. Investors make out like bandits, while student loan borrowers discover their investment did not pay off.

Every decade or two lawmakers learn about the hazards of dangling nearly unlimited government funding in front of for-profit colleges. When the abuses occur, lawmakers are shocked and outraged, and eventually they take action. Then, when the abuses are less severe, they relax the oversight, often despite warnings from consumer advocates. Abuses return with a vengeance, and the cycle repeats.

President Trump and Secretary DeVos are in the process of repealing important guardrails and weakening enforcement. The policy directions laid out in this report would enable Congress to protect veterans and other consumers from predatory schools by strengthening the guardrails that steer for-profit colleges to do what’s best for students, not just what inflates the stock price or maximizes short-term profits.

Editor’s note: This report is adapted from testimony that the author presented before the U.S. House of Representatives’ Subcommittee on Higher Education and Workforce Development, Committee on Education and Labor; and the House’s Subcommittee on Economic Opportunity, Committee on Veterans Affairs on April 24, 2019, in San Diego, California.

Notes

- The Century Foundation has published a series of essays, called, The Cycle of Scandal at For-Profit Colleges, chronicling this issue. The series is available at https://tcf.org/topics/education/the-cycle-of-scandal-at-for-profit-colleges/.

- “Memorandum Re: VA’s Failure to Protect Veterans from Deceptive Recruiting Practices,” Veterans Legal Services Clinic and Yale Law School, February 26, 2016.

- Michael Stratford, “VA warns California in for-profit college dispute,” Politico, January 17, 2019, https://www.politico.com/newsletters/morning-education/2019/01/17/va-warns-california-in-for-profit-college-dispute-482445.

- Mary Ellen Flannery, “NEA, CTA Sue DeVos Over Rollback of Protections for Online Students,” NEA Today, September 12, 2018, http://neatoday.org/2018/09/12/nea-cta-sue-devos-over-rollback-of-protections-for-online-students/.

- David Whitman, “Truman, Eisenhower, and the First GI Bill Scandal,” The Century Foundation, January 17, 2017, https://tcf.org/content/report/truman-eisenhower-first-gi-bill-scandal/.

- “The Role of State Approving Agencies in the Administration of GI Bill Benefits,” Congressional Research Service, December 29, 2016, https://www.everycrsreport.com/reports/R44728.html#_Toc471289795.

- “High-Risk Series: Government Student Loans,” U.S. Government Accountability Office, December, 1992, https://www.gao.gov/assets/660/659050.pdf.

- David Whitman, “When President George H. W. Bush ‘Cracked Down’ on Abuses at For-Profit Colleges,” The Century Foundation, March 9, 2017, https://tcf.org/content/report/president-george-h-w-bush-cracked-abuses-profit-colleges/.

- Kevin P. Bower, “‘A favored child of the state’: Federal Student Aid at Ohio Colleges and Universities, 1934–1943,” History of Education Quarterly, volume 44, number 3, 2004, 364–387, doi:10.1111/j.1748-5959.2004.tb00014.x.

- David Whitman, “When President George H. W. Bush ‘Cracked Down’ on Abuses at For-Profit Colleges,” The Century Foundation, March 9, 2017, https://tcf.org/content/report/president-george-h-w-bush-cracked-abuses-profit-colleges/.

- Chester E. Finn, Jr., “In Washington We Trust, Federalism and the Universities: The Balance Shifts,” Change, volume 7, number 10 (Winter 1975–1976), 29.

- David Whitman, “Vietnam Vets and a New Student Loan Program Bring New College Scams,” The Century Foundation, February 13, 2017, https://tcf.org/content/report/vietnam-vets-new-student-loan-program-bring-new-college-scams/.

- “Abuses in Federal Student Aid Programs,” S. Rpt. 102-58, Report made by the Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations of the Committee on Governmental Affairs, U.S. Senate, May 17, 1991, 16.

- “Abuses in Federal Student Aid Programs,” S. Rpt. 102-58, Report made by the Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations of the Committee on Governmental Affairs, U.S. Senate, May 17, 1991, 34.

- Antoinette Flores, “How the Trump Administration is Undoing College Accreditation,” Center for American Progress, April 18, 2019, https://www.americanprogress.org/issues/education-postsecondary/reports/2019/04/18/468840/trump-administration-undoing-college-accreditation/.

- Yan Cao, “Governor Cuomo Demands Quality from For-Profit Colleges—or Else,” The Century Foundation, January 17, 2019, https://tcf.org/content/commentary/governor-cuomo-demands-quality-profit-colleges-else/.

- See 38 U.S. Code § 3680A, “Disapproval of enrollment in certain courses,” available at https://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/38/3680A (accessed April 22, 2019).

- They become provisionally certified, a status that reduces the procedural barriers that would prevent the department from ejecting a school from Title IV or imposing other restrictions.

- David Whitman, “When President George H. W. Bush ‘Cracked Down’ on Abuses at For-Profit Colleges,” The Century Foundation, March 9, 2017, https://tcf.org/content/report/president-george-h-w-bush-cracked-abuses-profit-colleges/.

- Cleland v. National College of Business, 1978, available at https://caselaw.findlaw.com/us-supreme-court/435/213.html (accessed April 22, 2019).

- John D. Murphy, Mission Forsaken: The University of Phoenix Affair With Wall Street (Cambridge, Massachusetts: Proving Ground Education, 2013), citing Apollo Group, Apollo Group Prospectus, Smith Barney Inc., and Alex. Brown & Sons, December 5, 1994, 3.

- Further, eliminating the 90–10 rule, as some have advocated, would “increase enrollment at low-quality institutions and increase default rates.” Vivien Lee and Adam Looney, “Understanding the 90/10 Rule: How reliant are public, private and for-profit institutions on federal aid?” Brookings Institution, January, 2019, https://www.brookings.edu/research/does-the-90-10-rule-unfairly-target-proprietary-institutions-or-under-resourced-schools/.

- “Should Colleges Spend the GI Bill on Veterans’ Education or Late-Night TV Ads?” Veterans Education Success, April, 2019, https://static1.squarespace.com/static/556718b2e4b02e470eb1b186/t/5cb7ab40e2c4838d6c42eb31/1555540809463/VES_Instructional_Spending_Report_FINAL.pdf.

- Industry complaints about the difficulty of predicting 90–10 ratios, while exaggerated, could be addressed by using prior-year figures for the 85 percent numerator (in this way the cap would function as a limit on total revenue/enrollment rather than the less predictable proportion of federally-aided students). Additional adjustments that mirror the GI Bill approach could do a better job assuring student and taxpayer value in specific programs.

- 20 U.S. Code § 1094, “Program participation agreements,” available at https://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/20/1094 (accessed April 22, 2019).

- Section 3696 of title 38, United States Code (as amended by Public Law 112-249). The provision says that the VA shall, “to the extent practicable,” carry out the incentive compensation ban “in a manner that is consistent with the Secretary of Education’s enforcement” of the ban in Title IV.

- See (22) in “34 CFR § 668.14 – Program participation agreement,” available at https://www.law.cornell.edu/cfr/text/34/668.14 (accessed April 22, 2019).

- U.S. Department of Education guidance, GEN-11-05, March 17, 2011, http://ifap.ed.gov/dpcletters/GEN1105.html. See also “Program Integrity Questions and Answers – Incentive Compensation,” U.S. Department of Education, last modified February 2, 2012, accessed April 22, 2019, https://www2.ed.gov/policy/highered/reg/hearulemaking/2009/compensation.html.

- Robert Shireman, “Selling the American Dream: What the Trump University Scam Teaches Us about Predatory Colleges,” in Arien Mack, editor, “Cons and Scams: Their Place in American Culture,” Social Research, volume 85, number 4 (winter 2018), https://www.socres.org/single-post/854-winter-2018-cons-and-scams.

- Gretchen Morgenson, “A Whistle Was Blown on ITT; 17 Years Later, It Collapsed,” New York Times, October 21, 2016, https://www.nytimes.com/2016/10/23/business/a-whistle-was-blown-on-itt-17-years-later-it-collapsed.html?_r=0.

- David Whitman, “Vietnam Vets and a New Student Loan Program Bring New College Scams,” The Century Foundation, February, 2017, https://tcf.org/content/report/vietnam-vets-new-student-loan-program-bring-new-college-scams/.

- Thomas Corbett, “Opening a Dangerous Floodgate,” Inside Higher Ed, February 12, 2019, https://www.insidehighered.com/views/2019/02/12/former-profit-college-executive-says-education-department-shouldnt-weaken.

- Dawn Gilbertson, “Student-recruitment tactics at University of Phoenix blasted by feds,” Arizona Republic, September 14, 2004, http://archive.azcentral.com/families/education/articles/0914apollo14.html.

- “University of Phoenix Settles False Claims Act Lawsuit for $67.5 Million,” U.S. Department of Justice, December 15, 2009, https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/university-phoenix-settles-false-claims-act-lawsuit-675-million.

- Doug Lederman, “For-Profits and the False Claims Act,” Inside Higher Ed, August 14, 2011, https://www.insidehighered.com/news/2011/08/15/profits-and-false-claims-act.

- Doug Lederman, “For-Profits and the False Claims Act,” Inside Higher Ed, August 14, 2011, https://www.insidehighered.com/news/2011/08/15/profits-and-false-claims-act.

- For example, there is a current whistleblower case against Academy of Art University, United States ex rel. Rose v. Stephens Inst., that has survived a motion to dismiss.

- Kevin Carey, “The Creeping Capitalist Takeover of Higher Education,” HuffPost Highline, April 1, 2019, https://www.huffpost.com/highline/article/capitalist-takeover-college/.

- A program passes if the annual loan repayment of the median graduate is below 20 percent of their discretionary income, or 8 percent of their total earnings. Programs above 30 percent/below 12 percent fail, and those in between are in a “zone” and must warn students and show improvement in order to remain eligible for Title IV aid. Robert Shireman, “What Does the Gainful Employment Rule Mean for Career Schools Seeking Access to Federal Aid?” The Century Foundation, March 17, 2017, https://tcf.org/content/facts/gainful-employment-rule-mean-career-schools-seeking-access-federal-aid/.

- Press release, Maryland Attorney General Brian E. Frosh, October 17, 2017, http://www.marylandattorneygeneral.gov/press/2017/101717.pdf.

- A further complication has also arisen regarding the department’s access to earnings data. See Andrew Kreighbaum, “Agencies at Loggerheads Over Gainful-Employment Data,” Inside Higher Ed, December 6, 2018, https://www.insidehighered.com/news/2018/12/06/education-department-says-data-dispute-behind-failure-enforce-gainful-employment.

- Andrew Kreighbaum, “Agencies at Loggerheads Over Gainful-Employment Data,” Inside Higher Ed, December 6, 2018, footnote 17, https://www.insidehighered.com/news/2018/12/06/education-department-says-data-dispute-behind-failure-enforce-gainful-employment.

- “Notice of proposed rulemaking, Office of Postsecondary Education, Department of Education,” Federal Register, August 14, 2018, https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2018/08/14/2018-17531/program-integrity-gainful-employment.

- “Notice of proposed rulemaking, Office of Postsecondary Education, Department of Education,” Federal Register, August 14, 2018, https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2018/08/14/2018-17531/program-integrity-gainful-employment.

- See “Federal Student Loans: Actions Needed to Improve Oversight of Schools’ Default Rates,” GAO-18-163, U.S. Government Accountability Office, April, 2018.

- For details, see “Cohort Default Rates,” FinAid, last updated December 21, 2010, accessed April 22, 2019, http://www.finaid.org/loans/cohortdefaultrates.phtml.

- Ben Miller, “How You Can See Your College’s Long-Term Default Rate,” Center for American Progress, August 30, 2018, https://www.americanprogress.org/issues/education-postsecondary/news/2018/08/30/457296/can-see-colleges-long-term-default-rate/.

- Of 1,230 campus closures impacting over 500,000 students in the last five years, 88 percent of closures occurred at for-profit colleges. Michael Vasquez and Dan Bauman, “How America’s College-Closure Crisis Leaves Families Devastated,” Chronicle of Higher Education, April 4, 2019, https://www.chronicle.com/interactives/20190404-ForProfit.

- See “Financial Responsibility Composite Scores,” Office of Federal Student Aid, U.S. Department of Education, accessed April 22, 2019, https://studentaid.ed.gov/sa/about/data-center/school/composite-scores.

- “Financial Ratio Analysis Project: Final Report,” KPMG Peat Marwick, prepared on behalf of the U.S. Department of Education, August 1, 1996, https://www2.ed.gov/finaid/prof/resources/finresp/ratio/full.pdf.

- Enrollment grew from 67,445 students in the fall of 2007 to 113,818 just three years later. “For Profit Higher Education: The Failure to Safeguard the Federal Investment and Ensure Student Success,” Committee on Health, Education, Labor and Pensions, U.S. Senate, July, 2012, https://www.help.senate.gov/imo/media/for_profit_report/Contents.pdf.

- Matt Hamilton, “Corinthian Colleges must pay nearly $1.2 billion for false advertising and lending practices,” Los Angeles Times, March 23, 2016, http://www.latimes.com/local/lanow/la-me-ln-corinthian-colleges-judgment-false-advertising-20160323-story.html. See also Danielle Douglas-Gabriel, “Feds Found Widespread Fraud at Corinthian Colleges, Why Are Borrowers Still Paying the Price,” Washington Post, September 19, 2016, https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/grade-point/wp/2016/09/29/feds-found-widespread-fraud-at-corinthian-colleges-why-are-students-still-paying-the-price/?utm_term=.88813386d76b.

- Automatic approval is assured when a school has scores from the U.S. Department of Education of at least 1.5. From 2006 to 2010, the scores for Corinthian’s Everest Colleges (its other schools’ scores were not reported separately) were 1.7, 1.9, 2.6, and 1.6, according to data posted by the department at “Financial Responsibility Composite Scores,” Office of Federal Student Aid, U.S. Department of Education, accessed April 22, 2019, https://studentaid.ed.gov/sa/about/data-center/school/composite-scores.

- Under an agreement sponsored by the National Council for State Authorization Reciprocity Agreements (NC-SARA), online schools that have passing financial responsibility scores can bypass state regulations in all but their home states. Every state except California participates in NC-SARA.

- For TCF’s extensive reporting on this policy, see, for example, Yan Cao and Tariq Habash, “College Complaints Unmasked: 99 Percent of Student Fraud Claims Concern For-Profit Colleges,” The Century Foundation, November 8, 2017, https://tcf.org/content/report/college-complaints-unmasked/.

- Robert Shireman, “3 Ways the Education Department’s Proposed Borrower Defense Rules Are Dangerous to Consumers and Taxpayers,” The Century Foundation, August 30, 2018, https://tcf.org/content/commentary/3-ways-education-departments-proposed-borrower-defense-rules-dangerous-consumers-taxpayers/.

- There are also some differences in the application of the financial responsibility standards, and a requirement that an institution operate for two years before it can gain Title IV eligibility.

- 20 USC § 1003(13). The regulations use a three-part test: no private inurement; considered a nonprofit by states in which the institution is physically located; and “determined by the U.S. Internal Revenue Service to be an organization to which contributions are tax-deductible in accordance with section 501(c)(3) of the Internal Revenue Code.” See 34 CFR 600.2.

- See 20 U.S. Code § 1099c, “Eligibility and certification procedures,” accessed April 22, 2019, available at https://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/20/1099c.

- Robert Shireman, “The Covert For-Profit: How College Owners Escape Oversight through a Regulatory Blind Spot,” The Century Foundation, September 22, 2019, https://tcf.org/content/report/covert-for-profit/

- Robert Shireman, “These Colleges Say They Are Nonprofit. But Are They?” The Century Foundation, last updated March 8, 2019, https://tcf.org/content/commentary/colleges-say-theyre-nonprofit/.

- 34 CFR 668.16 (h): “Provides adequate financial aid counseling to eligible students who apply for Title IV, HEA program assistance. In determining whether an institution provides adequate counseling, the Secretary considers whether its counseling includes information regarding –

(1) The source and amount of each type of aid offered;

(2) The method by which aid is determined and disbursed, delivered, or applied to a student’s account; and

(3) The rights and responsibilities of the student with respect to enrollment at the institution and receipt of financial aid. This information includes the institution’s refund policy, the requirements for the treatment of title IV, HEA program funds when a student withdraws under § 668.22, its standards of satisfactory progress, and other conditions that may alter the student’s aid package. . .” - 34 CFR 668.82.

- A list of the conditions that have led to caution flags can be found at “Caution Flags,” GI Bill Comparison Tool, U.S. Department of Veteran Affairs, accessed April 22, 2019, https://www.benefits.va.gov/gibill/comparison_tool/about_this_tool.asp#CF.

- Paul Fain, “Gainful Employment Disclosures Delayed Again,” Inside Higher Ed, June 18, 2018, https://www.insidehighered.com/news/2018/06/18/education-department-delays-disclosures-under-gainful-employment-while-working.

- The requirement applies to schools at which fewer than half of borrowers had paid down at least $1 of their loans three years after leaving school. Clare McCann, “The Ins and Outs of the Borrower Defense Rule,” New America, July 10, 2017, https://www.newamerica.org/education-policy/edcentral/ins-and-outs-borrower-defense-rule/.

- Mary Ellen Flannery, “NEA, CTA Sue DeVos Over Rollback of Protections for Online Students,” NEA Today, September 12, 2018, http://neatoday.org/2018/09/12/nea-cta-sue-devos-over-rollback-of-protections-for-online-students/.

- Comment of Ruth Bullock of Bellingham, Washington, on the U.S. Department of Education’s proposed rule on “Program Integrity: Gainful Employment, submitted August 31, 2018, accessed April 22, 2019, https://www.regulations.gov/document?D=ED-2018-OPE-0042-8342.

- “The clear implication of advertising of this nature is that the United States Government has examined these institutions and is vouching for them.” See Proprietary Vocational and Home Study Schools, Final Report to the Federal Trade Commission and Proposed Trade Regulation Rule, Federal Trade Commission. December 10, 1976, 69 and 143.

- U.S. Department of Education, proposed rule, borrower defense, July 31, 2018, (Page 37243 of the Federal Register notice) https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2018/07/31/2018-15823/student-assistance-general-provisions-federal-perkins-loan-program-federal-family-education-loan

- “Toward a Federal Strategy for Protection of the Consumer of Education. Report of the Subcommittee on Educational Consumer Protection,” Office of the Assistant Secretary for Education, Department of Health, Education and Welfare, July, 1975, accessed April 22, 2019, https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED115173.pdf.

- “Toward a Federal Strategy for Protection of the Consumer of Education. Report of the Subcommittee on Educational Consumer Protection,” Office of the Assistant Secretary for Education, Department of Health, Education and Welfare, July, 1975, accessed April 22, 2019, https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED115173.pdf.

- Sandra E. Black et al., “Comment on FR Doc # 2018-17531,” September 12, 2018, accessed April 22, 2019, https://www.regulations.gov/document?D=ED-2018-OPE-0042-13499, citing Hurwitz, Michael and Jonathan Smith, “Student Responsiveness to Earnings Data in the College Scorecard,” Economic Inquiry, volume 56, number 2, 2018, 1220–43.

- Proprietary Vocational and Home Study Schools, Final Report to the Federal Trade Commission and Proposed Trade Regulation Rule, Federal Trade Commission, December 10, 1976, 61. The FTC described the strategy as a “highly developed and successful sales pitch . . . undermining the natural sales resistance and forcing the individual to prove his or her worth to the salesperson, instead of the salesperson proving the worth of the course to the prospect.” See 148.

- For Profit Higher Education: The Failure to Safeguard the Federal Investment and Ensure Student Success, U.S. Congress, Senate, Committee on Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions, 112th Congress, 2nd Session, 2012, S. Prt., 2648.