The state of Michigan has set a goal to increase the percentage of residents with a postsecondary degree or credential to 60 percent by 2030. Achieving that goal will require a concerted, strategic, and multi-pronged effort. Today, less than 50 percent of residents have attained a postsecondary degree or credential.1

While making college more affordable alone will not clear all the impediments to achieving the state’s attainment goal, the cost of college is a formidable barrier for many. Students from low-income families are especially sensitive to price increases, and it’s these students who must attend and complete at higher rates if the state is going to markedly grow its postsecondary completion rate.2 Yet, students from low-income families and first generation students have been disproportionately impacted by the pandemic, as reflected in lower college enrollment rates, and may need additional support and flexibility simply to enroll and complete college at levels seen in the recent past, let alone achieve the increases needed to reach the state’s attainment goal.3

This report focuses on one of Michigan’s key levers to making college more affordable for low-income students, analyzing the state’s largest, most generous, and best targeted college grant program, the Tuition Incentive Program (TIP).4 TIP stands out in Michigan, and in comparison with grant programs in other states, due to its well-targeted and categorical method of defining eligibility and benefits. This program could serve as a model for other states as they seek to expand college access and success. The report describes the program’s strengths and offers recommendations for policymakers to bolster it, including by expanding the eligibility criteria, and further aligning the incentives of the program with the state’s attainment goal.

The Tuition Incentive Program

TIP provides roughly $60 million in tuition aid to 24,000 students each year in the form of a need-based grant, supporting students from low-income families in Michigan.5 While TIP is the largest state scholarship program, it supports a small fraction of the 472,270 undergraduates in Michigan.6 Qualification is determined based on enrollment in Medicaid, and students who received Medicaid coverage for twenty-four months out of any thirty-six-consecutive-month period between sixth grade and twelfth grade (inclusive) are eligible to receive TIP. Phase I of the program provides full tuition and mandatory fees up to $250 per semester at the student’s in-district community college to all students who qualify. Students who do not live in a community college district, or are without a local community college that offers the program they need, may receive a TIP award to attend an out-of-district institution.7 TIP Phase I provides the average community college tuition rate for students attending private universities and is also available to students enrolled in associates degree programs that are housed within four-year public universities.8

TIP also provides a benefit for students who attend four-year institutions, called TIP Phase II. Phase II provides $500 per semester, or a total of $1,000 per year, for students after the first two years, or 56 credits, of postsecondary education. Students can receive TIP Phase II benefits even without receiving TIP Phase I, which are only available to students enrolled in associate’s degree programs.

The program also covers tuition and fees for students enrolled in associate’s degree programs at the handful of four-year public universities in Michigan that offer them. All recipients have to complete the Free Application for Federal Student Aid (FAFSA) and be enrolled at least part-time. On average, TIP provides $3,377 per student in Phase I and $870 per student in Phase II to students in public and private institutions across the state.9

Advantages of the TIP Program

One of the best features of TIP is that it “goes first” relative to federal aid. Students can receive TIP and Pell simultaneously, and if they qualify for both aid programs, TIP can cover most, if not all, their tuition and fees while Pell can help with other educational and living costs. This combination makes community college affordable for most eligible students. The feature is quite rare, as most state free college programs are “last dollar,” requiring students to exhaust Pell before gaining any benefit from the state aid.10 Research shows that expenses beyond tuition often serve as a barrier to low-income students completing college, and living expenses can account for as much as half of college costs.11 This need is particularly acute during the COVID-19 pandemic when many low-income college students are suffering from food and housing insecurity.12 College enrollment levels are down in Michigan and nationwide, particularly at community colleges and among students from low-income families.13

TIP is also well-designed in that it has an inherent partial inflation adjustment. By covering full tuition and fees up to $250 per semester, the program award automatically adjusts to respond to increases in tuition. Other state grant programs provide a fixed grant award that must be raised legislatively and/or require students to exhaust the state grant award before receiving any funding from Pell, limiting the total financial aid package to an amount that may not put college within reach financially.

TIP is well-targeted at a largely vulnerable population: the Medicaid income cut-off in Michigan is roughly $50,000 for a family of four, which aligns very closely with federal Pell Grants distribution. Pell eligibility is widely accepted as a strong indicator of financial need.14 And because eligibility is limited to students who received Medicaid for two years during a three-year stretch, the program is further targeted at students from families who suffered significant financial strain over an extended period. Other Michigan state scholarships, such as the Michigan Tuition Grant and the Michigan Competitive Scholarship, provide support for a broader swath of students who have any financial need as determined by the FAFSA.15 Futures for Frontliners (FFF), a new Michigan program designed to provide “free tuition for essential workers,” provides the same award to Pell-eligible students as those who are not Pell-eligible.16

Together, these provisions mean that TIP is unique when compared with other state grant programs and well-designed to help the students who often have the greatest financial need: those without the resources to pay for college, those who are most sensitive to price when making decisions about where or whether to attend college, those who are more likely to be Black, Brown, Indigenous, and/or the first in their family to go to college.

Finally, and perhaps most importantly, TIP can send a clear, early message to eligible students that college is possible and that the state of Michigan wants them to attend. In an unusual feature, the Michigan Department of Treasury alerts students about their eligibility and the benefits of this program when they are as young as age 12 and regularly after that. In fact, the program was originally designed to provide an incentive for low-income students to complete high school and enroll in college. In sum, TIP offers many of the advantages of College Promise programs, which exist throughout Michigan, for students attending community college while also retaining a focus on equity by dedicating most of the funds to students from low-income homes.

TIP’s Unique Design Compared with Other State Grant Programs

Michigan is a leader in building a financial aid program with transparent eligibility criteria for students. A systematic review of each state’s largest need-based aid programs and any College Promise programs found that only three other states and Washington, D.C. use existing means-tested analysis from other public programs to streamline qualification, with mixed success as to the use of such a provision.

- The California College Promise Grant allows for recipients of benefits under multiple other programs to qualify: CalWORKs and Temporary Assistance to Needy Families (TANF), which provide cash assistance and other services to very low-income families; Supplemental Security Income (SSI)/SSP, which provides income support for those with little or no income who are aged, people who are blind, and people with disabilities; General Relief, which provides assistance for indigent adults.17 Students who qualify as homeless youth under the McKinney–Vento Homeless Assistance Act are also automatically eligible. However, less than 1 percent of students who receive the Promise grant do so using these methods; the vast majority simply either fill out an application with their income or file a FAFSA. While this may be because other methods of proving eligibility are even simpler, it also could suggest that outreach to potential benefit recipients that qualify through these programs fails to reach them.

- In Washington State, the College Bound program allows students currently in foster care or a dependent of the state status, or a student whose family receives Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP)/Basic Food Assistance or TANF benefits, to qualify.18 About 26 percent of College Bound students indicated that they were enrolled in TANF to demonstrate their eligibility in the initial application for the program,19 and Washington State, like Michigan, recently removed the front-end application requirements by automatically putting all students eligible for free and reduced price lunch into their systems—a change introduced during the COVID-19 pandemic that the state may make permanent.20 The state already automatically signs students up for the program if they are in foster care.

- Similarly, in Washington, D.C., the district scholarship program allows for students who cannot fill out the FAFSA to prove SNAP or TANF eligibility to qualify.

- In Ohio, students receiving veterans benefits automatically qualify to use the state grant at community colleges, which is otherwise unavailable to students in that sector.21

Relying on students’ receipt of other public benefits to determine their college financial aid eligibility helps to target limited aid, and should, in theory, make sense from an operational and communications standpoint. For students applying for college financial aid, especially for the first time, administrative hurdles and confusing rules create often needless barriers for potential recipients. The administrative challenges associated with filing a FAFSA, for example, mean that as much as $2 billion in Pell grants go unclaimed.22 But the way provisions are implemented may lead to them being underutilized.

Current TIP Recipients

About 24,000 students total per year receive TIP benefits, including slightly more than 15,000 who are in Phase I (the first two years of an associate’s degree program) and close to 9,000 in Phase II (third and fourth year of bachelor’s degree program). Of those 15,000 in Phase I, we can estimate that slightly more than half are in their first year of college, in light of substantial college attrition rates.

The number of students receiving TIP is a fraction of the total students who could likely obtain the grant if they applied. Official totals of TIP-eligible students are not available, but American Community Survey data suggest that, in recent years, Michigan has averaged about 172,000 high school students who are enrolled in Medicaid. Using estimates of the percentage of Medicaid spells that last the requisite twenty-four months and the rate of ninth grade students who ultimately enroll in college within four years of graduating high school, we estimate that upward of 77,000 recent high school graduates meet the Medicaid coverage requirement and are enrolled in college, and another 26,000 are not enrolled in college but could likely claim TIP if they enrolled.23 Because a student can qualify for TIP based on their Medicaid enrollment prior to ninth grade, these figures may be underestimates. Given that there are only about 24,000 participants per year, this participation rate of less than one-third among enrolled students indicates that millions in TIP dollars are left on the table by low-income students each year.

The Michigan Legislature made some changes to increase access to TIP in response to the disruption of the educational cycle during the COVID-19 pandemic. Specifically, they expanded the duration of eligibility and eliminated the need for a separate TIP application process, enabling all eligible students who fill out a FAFSA and enroll in college to receive TIP grant aid, aligning the process with the process students must go through to access other state and federal financial aid.

Given the combination of a pandemic and recession, the 2020–21 academic year is an anomaly that makes it especially hard to make future projections for TIP program take-up resulting from these changes. Early data from the National Student Clearinghouse shows that undergraduate enrollment is down in Michigan by almost 9 percent, and that enrollment amongst first-time community college students nationwide is down 19 percent.24 The majority of TIP recipients and TIP dollars go to community colleges.25 So even if recent changes significantly increased access for those who would not otherwise have enrolled or received TIP scholarships, the overall pandemic-fueled decline in enrollment may mask that positive effect.

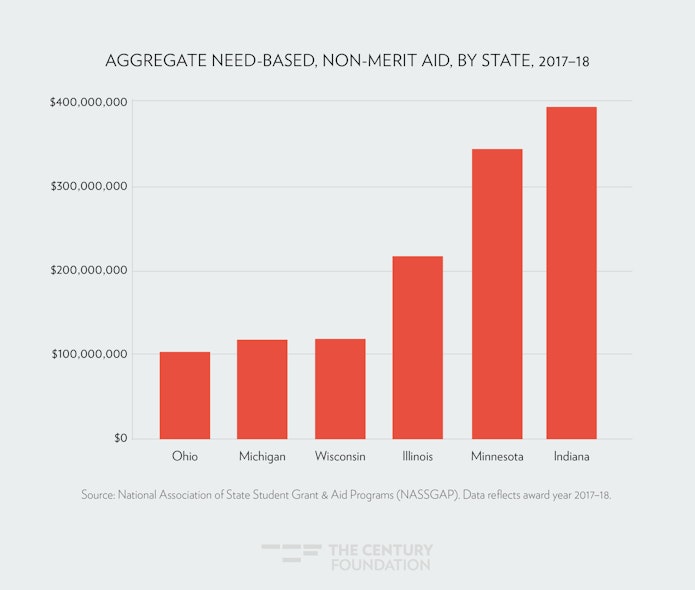

Regardless of the impact of the most recent changes, it’s clear that there is significant room for additional improvement in the eligibility and take-up of the grant. While Michigan is a leader in the design of this critical need-based aid, it is, overall, far behind many of its neighbors in the scale of financial aid it offers its residents. The state trails all of its Midwestern neighbors but Ohio in providing statewide, need-based grant aid, both in terms of aggregate dollars and per student aid available. (See Figures 1 and 2.)

Figure 1

Figure 2

There may also be programmatic improvements that could be made to incentivize higher completion rates of students who receive TIP. Data on completion rates by TIP recipients is not publicly available, but research shows that students enrolled in public two-year institutions graduate at lower rates than those attending four-year institutions.26

Reducing Operational Hurdles

In its fiscal year 2020–21 education omnibus budget, the Michigan Legislature made key changes that will increase access to, and likely the take-up of, TIP dollars.27 First, the legislature adjusted the window of time in which a student remains eligible for TIP once they have begun using it, increasing it from six years to ten years. This change gives students greater flexibility to enroll less-than-full-time and re-enroll after stopping out, a feature that will be particularly valuable as low-income students weather the pandemic.

The legislature also removed the requirement that students complete a separate application in order to receive TIP by August 31 of their senior year of high school.28 Historically, this requirement has caused otherwise-eligible students to lose access to the program without any opportunity to restore it, a process that stood in contrast to all federal and other state aid, which is available to any student who completes a FAFSA and qualifies, regardless of when they graduated from high school. Due to the transient nature of the population served, not all eligible students received notification that they needed to complete a form to receive TIP. If a student’s name or address was misspelled or they had moved, they may never have received the notice.

Also, students who did not go directly to college or were not focused on college directly after graduating from high school lost the chance to take advantage of TIP if they failed to complete the application. Even those who did go directly from high school to college sometimes missed out on this aid because the deadline of August 31 fell right before most colleges begin their fall semester, and thus right before many financial aid counselors engage with new students.

Since most TIP benefits accrue to community college students, and some of the rules—such as those governing the two-phase system—are complicated, some students who were TIP-eligible but went straight to a four-year college failed to complete the application and missed out on the Phase II benefit. And finally, and most fundamentally, the process put the onus on students to confirm their eligibility. In doing so, it wasted taxpayer funds by requiring staff to promote and administer an unnecessary application process while imposing more rules on needier students than on the somewhat better off students attending four-year colleges and receiving other state grants, which do not require a separate application process.

These are important changes that will make TIP easier to access, but key barriers remain: for example, a student must still begin using TIP within four years of earning their high school diploma, generally excluding those who first decide to enroll in college in their mid-twenties or later. This provision also makes it impossible for students to combine TIP with Michigan Reconnect, a new community college tuition-free program for individuals over 25. Federal student aid, such as the Pell Grant, and other state aid programs, such as the Michigan Tuition Grant and the Michigan Competitive Scholarship, do not have as stringent time restrictions (if they have them at all).

Recommendations

The TIP program provides a well-structured base for any expansion of state need-based aid grants, targeting vulnerable students who grew up in poverty with a meaningful, well-defined benefit. As the state considers ways to advance towards the state’s attainment goal, and works through near-term budget challenges, the highest priority should be to protect the most effective elements of TIP; in particular, the Michigan Legislature should ensure that the program remains available to all currently eligible students as a “first dollar” program, and that the program continues to cover full tuition. While current recessionary budget challenges make it less likely that the legislature will pursue a significant expansion of TIP in the near-term, building on this grant as soon as the state budget allows for it will put the state on a strong pathway toward addressing the college affordability challenges faced by students in the state, and help Michigan better meet its educational attainment goals and workforce needs.29

Detailed below, we propose that policymakers could expand access to the grant, utilizing a stepwise approach. In the immediate term, the state can first remove operational barriers and expand access for current recipients to use the grant at four-year institutions.

Longer term, the state should consider (1) expanding eligibility by automatically qualifying students who come from families with incomes and assets that already qualify them for means-tested public benefits beyond just Medicaid, and/or (2) expanding the grants to people who show they are low-income using traditional, but often more complex, financial aid eligibility criterion.

Immediate Recommendations

1. Remove operational barriers for students already eligible for TIP.

A number of operational barriers exist both for current TIP recipients and for TIP-eligible students who are not enrolled. For current students, the state should extend the Phase I grant to thirty credits per year. Current TIP policy limits the number of credits covered annually to twenty-four, even though research shows that, for students who are able to take and complete them, courseloads of fifteen credits per semester facilitate higher completion rates.30 While twelve credits is considered a full-time courseload as defined by federal financial aid regulation, the State of Michigan uses fifteen credits for its full-time student definition. Limiting students to twelve credits when they could manage fifteen draws out their time to completion. Extending the maximum annual number of credits to thirty would not increase the cost of the program; the program would still cover a cumulative total of eighty credits. In fact, it could lower the cost by paying for more credits earlier in a student’s education, since tuition often rises annually. This change would simply allow students the choice to accelerate through their education more quickly.

For TIP-eligible students who have not enrolled in college, the state can increase take-up through earlier and consistent communication. The Michigan Department of Treasury financial aid office provides workshops for college access professionals as well as high school guidance counselors and conducts direct outreach to TIP-eligible students. Previously, these resources were focused on getting students to complete the TIP application and explaining the program to them. Now, with the elimination of the application, college counselors and outreach officials could instead direct their efforts to marketing the value of college, helping students find the right college match, and demystifying the FAFSA and application process.

2. Remove the $250 cap on TIP aid going toward fees.

Institutional fees can often exceed $1,000, and can be much higher for certain programs of study that require specific equipment for training students. Eliminating the cap on TIP aid going toward these fees would dramatically improve college affordability for TIP-eligible students by covering a greater proportion of college costs and freeing up students’ Pell grants to cover living and other expenses. Currently, students may have to dedicate a portion of their Pell grants to fees.

3. Allow students to use TIP Phase I at all four-year public universities.

By limiting TIP Phase I to community colleges and associate degree programs, TIP incentivizes the lowest income college students in Michigan to attend community colleges. Though public two-year colleges are often a good choice for students, some may prefer to attend four-year universities where they are more likely to be able to complete a four-year degree, if that is their goal. Allowing eligible students to take their TIP Phase I award to any public college they select would empower them to make the best decision for their educational and professional interests. It might also raise the state’s postsecondary attainment level, since four-year institutions generally have higher graduation rates than two-year schools. Given near-term budget constraints, policymakers would not necessarily need to expand the program to cover full tuition at more expensive four-year colleges to have an impact in the short-term; they could change the program through the annual budget process to enable TIP-eligible students to receive the average community college tuition at public universities.

4. Remove the limitation on when students can use the benefit.

Currently, students must begin to use TIP within four years of completing high school, a requirement that limits the ability of older students to access the program. Other state scholarships and federal financial aid do not have a similar requirement. Subjecting the most vulnerable students to the most stringent standards for accessing state financial aid is counterproductive to the state’s goal of substantially increasing college attainment. Lifting this barrier would also enable older students to complete college at higher rates by allowing eligible students to simultaneously use TIP, Futures for Frontliners, Michigan Reconnect, and Pell.

5. Publish data on TIP eligibility, take-up, and completion rates.

Understanding the total population eligible for the TIP grant and the outcomes of those who receive this aid will help education administrators and state policymakers alike better understand who is or is not taking advantage of the benefit and the impact this investment is having on progress toward the state achieving its attainment goal. Publishing data on the total eligible population, broken down by key demographics such as race, gender, and geography, will also help stakeholders reach potential recipients with the information they need early enough to influence college-going decisions.

6. Consider adjusting the length of time requirement for continuous Medicaid enrollment.

The current requirement is that students be enrolled in Medicaid for twenty-four months. It is unclear how policymakers determined that time period; presumably, it was designed to capture students who grew up in entrenched poverty. However, many Medicaid recipients still churn in and out of the program, even if they remain very low-income the whole time.31 And it’s unclear whether the twenty-four-month measurement is a reasonable assessment. Policymakers should assess the effect of the provision, analyzing who misses the cutoff and why, and use that analysis to inform any adjustments to the requirement.

Longer-term Recommendations

1. Expand TIP based on additional public benefit enrollment data.

Using receipt of public benefits from programs that have already made an assessment of need to determine distribution of grants is intended to target resources to those with proven high need and to simplify the process such that students and families are not required to prove their poverty or low incomes over and over. Yet, estimates are that as little as one-third of students who are eligible based on their receipt of Medicaid actually receive TIP. This is consistent with data from other states such as California, where using public benefits enrollment to determine eligibility for other aid is not a primary strategy and has fallen far short of its potential.

Once Michigan has successfully removed operational challenges—automating sign-ups as much as possible, improving and streamlining communications to potential recipients, increasing portability and flexibility for grant recipients—it can consider expanding automatic access to TIP to other categories of needy students, such as those coming out of the foster care system, homeless youth, or students who qualify for free and reduced price lunch, or recently unemployed students. For example:

- Unemployment insurance (UI). Between 2015 and 2018, Michigan averaged roughly 85,000 unemployed workers with only a high school diploma. Using data on unemployment insurance, this report estimates that Michigan averaged roughly 24,000 UI claimants with only a high school diploma over this same period.32 Connecting this population to public colleges more directly by providing them TIP benefits would provide an effective and streamlined retraining option for out-of-work Michiganders.

- Free and reduced price lunch. Approximately 231,000 high school students in Michigan are receiving free and reduced price lunch. While some of those students may already qualify for TIP by virtue of also being enrolled in Medicaid, many likely do not. Expanding TIP to these students and providing communication early and often could significantly help increase public college enrollment and educational attainment in Michigan.

Expand TIP based on federal financial aid criteria.

Michigan policymakers could also consider expanding TIP using more traditional financial need assessments, either relying on tax data, self-attestation, or FAFSA application data. For example, policymakers could start by expanding access to students and families earning below the poverty line, as evidenced through tax filings or alternate documentation for non-tax filers, or mirror California’s reliance on self-reported income. Or, they could rely on FAFSA data and provide the benefit to students earning below a set threshold. Doing so would utilize an existing needs analysis formula that is imperfect but generally targeted, and requires information most students already provide to the federal government and colleges through the FAFSA.

This strategy has some drawbacks. Providing a clear benefit and clear eligibility rules can have a positive impact on student and public understanding of a program; including a cutoff of a particular Expected Family Contribution (EFC) level (which will be known as the Student Aid Index starting in 2023), on the other hand, relies on federal financial aid terminology not widely understood by those who are not financial aid professionals. Doing so limits the ability of future recipients to understand whether they will be eligible, which in turn may limit the program’s effect on college enrollment. Murky eligibility cutoffs linked to EFC or the future Student Aid Index limit the public’s understanding of who receives the benefit each year and may mask harmful cuts.

Looking Ahead

A diverse group of stakeholders have long called for a single, strengthened, and wide-reaching state need-based grant aid program in Michigan. The Institute for College Access & Success has highlighted high student debt for Michigan’s graduates and affordability barriers for the state’s lowest income students.33 The MiHeart coalition, made up of business, educational, and nonprofit leaders, have jointly called for a $400 million investment in a new state grant program.34 Last spring, The Century Foundation published a report calling for both expanding the reach of TIP and for a long-term goal of creating a broad-reaching state need-based aid grant.35

As the state and its public colleges build back from the COVID-19 crisis in the next few years, the TIP program provides a place for those efforts to focus initial steps, first removing barriers to accessing the existing program and then by expanding eligibility over time to move the state forward on college affordability.

Acknowledgments

Thank you to Lumina Foundation for their support of this work. Thank you to Alisha Cederberg of the Michigan Student Financial Aid Association; Stacy Boone of the Detroit Chamber of Commerce; Ashley Johnson and Onjila Odeneal of DetroitCAN; Kevin Stange of the University of Michigan; Bridget Timmeney of the Upjohn Institute; Dan Hurley and Bob Murphy of the Michigan Association of State Universities; Colby Cesaro and Shannon Dunivon of Michigan Independent Colleges & Universities; Erin Schor and Erica Orians of the Michigan Community College Association; Maddy Day, board chair, and Ryan Fewins-Bliss and Jamie Jacobs of the Michigan College Access Network; and Jessica Thompson of TICAS for their thoughtful comments on a draft of this report and thought partnership throughout its development. Thank you to Cody Impton for his research assistance.

Catherine Brown lives and works in central Michigan and serves as the senior advisor for the state of Michigan at The Institute for College Access & Success (TICAS), helping to advance affordability, equity and accountability in Michigan’s public colleges. Previous to joining TICAS, Brown served as the vice president of education policy at the Center for American Progress, vice president for policy at Teach for America, and as a senior consultant for Leadership for Educational Equity. Earlier in her career, Brown was a senior education policy adviser for the House Committee on Education and Labor, where she advised Chairman George Miller (D-CA). In 2008, Brown served as the domestic policy adviser for presidential candidate Hillary Clinton after serving as legislative assistant for education, labor, and children’s issues for then-Senator Clinton (D-NY). Brown received her bachelor’s degree from Smith College and holds a master’s in public policy from the Kennedy School of Government at Harvard University.

Notes

- “A Stronger Nation: Tracking America’s Progress Toward 2025,” Lumina Foundation, n.d., accessed February 2, 2021, https://www.luminafoundation.org/stronger-nation/report/2020/#nation.

- Rick Seltzer, “Turning Down Top Choices,” Inside Higher Ed, March 23, 2017, https://www.insidehighered.com/news/2017/03/23/study-shows-how-price-sensitive-students-are-selecting-colleges.

- Audrey Williams June, “Applications for Next Year’s Freshman Class Are on the Rise—With Warning Signs for Equity,” Chronicle of Higher Education, January 28, 2021, https://www.chronicle.com/article/applications-for-next-years-freshman-class-are-on-the-rise-with-warning-signs-for-equity.

- “Tuition Incentive Program,” Michigan Office of Postsecondary Financial Planning, n.d., accessed February 2, 2021, https://www.michigan.gov/mistudentaid/0,4636,7-372–481218–,00.html.

- “2018–19 Annual Report,” Michigan Office of Postsecondary Financial Planning, February 2020, https://www.michigan.gov//documents/mistudentaid/2019_Annual_Report_681204_7.pdf.

- “Michigan Colleges Student Population,” Univstats, n.d., accessed February 2, 2021, https://www.univstats.com/states/michigan/student-population/#:~:text=At%20Michigan%20colleges%2C%20there%20are,male%20and%20305%2C929%20female%20students.

- Students who choose to attend an out-of-district community college program that is available in-district may face higher tuition costs.

- “Tuition Incentive Program Flyer,” Michigan Office of Postsecondary Financial Planning, n.d., accessed February 2, 2021, http://michigan.gov/documents/mistudentaid/5111_447272_7.pdf.

- “2018–19 Annual Report,” Michigan Office of Postsecondary Financial Planning, February 2020, https://www.michigan.gov//documents/mistudentaid/2019_Annual_Report_681204_7.pdf.

- Jen Mishory and Peter Granville, “Policy Design Matters for Rising “Free College” Aid, The Century Foundation, July 6, 2019, https://tcf.org/content/commentary/policy-design-matters-rising-free-college-aid/.

- “Addressing the College Completion Gap Among Low-Income Students,” College for America, June 7, 2017, https://collegeforamerica.org/college-completion-low-income-students/;

“Unpacking California College Affordability: Experts Weigh In On Strengths, Challenges, and Implications,” The Institute for College Access and Success, February 2018, https://ticas.org/california/unpacking-california-college-affordability-experts-weigh-strengths-challenges-and/. - Kaya Laterman, “Tuition or Dinner? Nearly Half of College Students Surveyed in a New Report Are Going Hungry,” The New York Times, May 2, 2019, https://www.nytimes.com/2019/05/02/nyregion/hunger-college-food-insecurity.html.

- Julie Mack and Scott Levin, “Fall 2020 enrollment drops 3.5% at Michigan’s state universities; see numbers by school,” MLive, November 23, 2020, https://www.mlive.com/public-interest/2020/11/fall-2020-enrollment-drops-35-at-michigans-state-universities-see-numbers-by-school.html; Todd Sedmak, “Fall 2020 Undergraduate Enrollment Down 4% Compared to Same Time Last Year,” The National Student Clearinghouse, October 15, 2020,

https://www.studentclearinghouse.org/blog/fall-2020-undergraduate-enrollment-down-4-compared-to-same-time-last-year/. - Spiros Protopsaltis and Sharon Parrott, “Pell Grants—a Key Tool for Expanding College Access and Economic Opportunity—Need Strengthening, Not Cuts,” The Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, July 27, 2017,

https://www.cbpp.org/research/federal-budget/pell-grants-a-key-tool-for-expanding-college-access-and-economic-opportunity. - TICAS internal calculations.

- “Futures for Frontliners,”State of Michigan, n.d., accessed February 2, 2021, https://www.michigan.gov/frontliners/.

- “The California College Promise Grant,” College of the Canyons, n.d., accessed February 2, 2021, https://www.canyons.edu/studentservices/financialaid/types/bogw.php.

- “College Bound Income Requirements,” Washington Student Achievement Council, n.d., accessed February 2, 2021, https://readysetgrad.wa.gov/college/College-Bound-Sign-Up; “What Is the College Bound Scholarship?” Washington Student Achievement Council, n.d., accessed February 2, 2021, https://wsac.wa.gov/sites/default/files/2020.FAQ.CollegeBound.pdf.

- Data provided by the state aid agency.

- Office of Governor, “Proclamation by the Governor Amending Proclamation 20-05: 20-77: College Bound Program Pledge Waivers,” State of Washington, accessed February 1, 2021, https://www.governor.wa.gov/sites/default/files/proclamations/proc_20-77.pdf.

- Many states also have programs that make specific grants available to students who were in the foster youth system.

- Peter Granville, “Should States Make the FAFSA Mandatory?” The Century Foundation, July 28, 2020, https://tcf.org/content/report/states-make-fafsa-mandatory/.

- These estimates are derived from the five-year (2014–18) Public Use Microdata Sample (PUMS) of the American Community Survey (ACS), the U.S. Census Bureau’s annual survey of a representative sample of the U.S. population. We used the weighted estimate of Michigan high school students on Medicaid in the PUMS dataset, an estimate of the share of Medicaid coverage periods that last twenty-four months based on HHS statistics, and an estimate of the percentage of ninth grade students who enroll in college within four years of graduating high school based on NCES surveys.

- “Stay Informed with the Latest Enrollment Information,” National Student Clearinghouse Research Center, November 12, 2020, https://nscresearchcenter.org/stay-informed/.

- “SSG 2018-2019 Annual Report,” Michigan Department of Treasury—Office of Postsecondary Financial Planning, February 2020, https://www.michigan.gov//documents/mistudentaid/2019_Annual_Report_681204_7.pdf.

- Grace Chen, “The Catch-22 of Community College Graduation Rates,” Community College Review, updated June 15, 2020, accessed February 1, 2021, https://www.communitycollegereview.com/blog/the-catch-22-of-community-college-graduation-rates.

- “House Substitute for Senate Bill No. 927,” Legislative Service Bureau, September 23, 2020,”https://www.legislature.mi.gov/documents/2019-2020/billconcurred/Senate/pdf/2020-SCB-0927.pdf.

- “Michigan Budget Deal Win for College Students,” September 23, 2020, https://ticas.org/michigan/michigan-budget-deal-win-for-college-students/.

- Peter Granville, Kevin Miller, and Jen Mishory, “Michigan’s College Affordability Crisis,” The Century Foundation, September 6, 2019, https://tcf.org/content/report/michigans-college-affordability-crisis/.

- Clive Belfield, Davis Jenkins, and Hana Lahr, “Momentum: The Academic and Economic Value of a 15-Credit First-Semester Course Load for College Students in Tennessee,” Community College Research Center, June 2016,

https://ccrc.tc.columbia.edu/publications/momentum-15-credit-course-load.html. - Elizabeth Austic, Emily Lawton, Melissa Riba, and Marianne Udow-Phillips, “Insurance Churning,” Center for Healthcare Research and Transformation, November 2016, https://poverty.umich.edu/research-publications/policy-briefs/insurance-churning/.

- Because public data on unemployment claims by educational attainment are not available, we use the general rate of UI receipt among unemployed people in Michigan as a proxy in calculating these estimates.

- Student Debt for College Graduates in Michigan, TICAS, https://ticas.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/Michigan.pdf; College Costs in Michigan, TICAS,

https://ticas.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/College-costs-in-Michigan-fact-sheet.pdf. - John Austin, “Total Talent,” MiHeart and Michigan College Access Network, September 14, 2018, https://michigancollegeaccessnetwork.app.box.com/s/zu845fljgievvf3avllvnbgdciu5ytvi.

- Jen Mishory and Andrew Stettner, “Moving Michigan Forward: Public Higher Education Finance Reforms to Bring College within Reach,” The Century Foundation, June 8, 2020,

https://tcf.org/content/report/moving-michigan-forward-public-higher-education-finance-reforms-bring-college-within-reach/.