MEMORANDUM

To: University Presidents

From: Stephanie Hall

Re: An Opportunity to Revise OPM Contracts

Sometime in the coming weeks, there will be a policy change announced by the U.S. Department of Education that some of your for-profit contractors will tell you is going to wreak havoc on your budget. Don’t believe them.

The policy change will impact the arrangements you have made to enroll students in your online-only college programs. Companies that provide platforms for colleges’ online courses—known as online program managers (OPMs)—may be taking 50 percent or more of your college’s tuition revenue for these courses through long-term contracts. As it turns out, since most of those contracts involve the companies recruiting students in addition to running the online platform, the tuition-sharing component of these contracts may implicate a federal law that prohibits commission-paid sales in colleges that receive federal aid.

Despite this ban, the Department of Education has let the practice continue since 2011. I am writing to let you know that the practice is under increased scrutiny, and the days for this policy exception are probably numbered. Whether due to the anticipated report from the Government Accountability Office or the next scandal like this one, the department probably soon will need to revise its policy exception and enforce the law as written by Congress.1

The coming revision of the policy exception means that some of your arrangements with companies such as 2U, Academic Partnerships, and Pearson—any contract that involves recruiting students and paying contracted providers on a per-student basis—will have to change. The reversal of the policy exception will not be sudden, though, because the U.S. Supreme Court, in a case decided against the Trump administration in 2020, made it clear that policy changes must—even when they involve enforcing an existing law—be carried out in a way that is orderly and fair, not suddenly pulling the rug out from current practices based on policy guidance.2

The sky will not fall. Instead, you can be assured that in the policy change process:

- you will have time;

- you will have options; and,

- your institution, your students, and your faculty will ultimately be better off.

Below are some questions and answers that should help you understand what is coming, why, and how you can best manage it to your advantage as an institution and as an advocate for what is best for students.

Why did the Department of Education issue the 2011 policy guidance?

To provide colleges and universities a boost in getting off the ground when it came to offering online degrees, the Department of Education considered scenarios in which an institution might partner with a vendor that would provide a bundle of services. Not yet known as OPMs, these “online enablers” were anticipated to help schools with student recruitment, marketing, online platform support, and academic services.3 In 2011, the department issued guidance stating that bundles of such services could be paid for in ways that would otherwise violate the federal ban on incentive payments to recruiters.4 This carve-out for providers of these bundled services led to an explosive growth in colleges’ reliance on OPMs and launched public and nonprofit colleges online in a way that allowed them to quickly catch up with for-profit colleges that had first dominated the online degree market.

While the 2011 policy guidance (commonly referred to as “bundled services guidance”) helped these schools enter the online program space, the exception to the ban on incentive compensation payments to recruiters carved out by the guidance has proved dangerous. Tuition-sharing agreements, in which colleges split the revenue for a particular program between a college and its contractor, can create an incentive for the company doing the recruiting to secure as many enrollments as possible, as revenue increases with enrollment.

The exception was intended to allow public and nonprofit institutions to compete with for-profit and other online providers, and it worked: more students are now enrolled in online classes in the public and nonprofit sectors than in for-profit colleges.5 Unfortunately, some outsourced online programs have taken on the same characteristics as predatory for-profit colleges.6

What is wrong with these tuition-sharing, student-recruitment contracts?

When online programs became a viable option for providing higher education, public and nonprofit institutions approached the Department of Education and made the case that they needed to be able to contract with outside companies to compete with for-profits who were already out of the gate.7 Many institutions at the time legitimately needed support for things such as course design, video and digital asset production, platform integration, marketing, recruitment, and so on, and many still do. Schools that seek these services via a bundled OPM contract are not, however, getting them at a fair cost. What they receive is more akin to an expensive marketing, lead generation, and recruitment/sales operation. Over the life of an agreement, once courses have been designed and “course carousels” established, the focus of OPMs switches primarily to recruiting and marketing. As a result, schools and students are paying more than necessary in the long run for these bundled services, and the for-profit incentives tied to recruitment and enrollment are hurting students and costing taxpayers.

The bundled service provider exception to the incentive compensation ban has served its initial purpose, but now has morphed into a vehicle for embedding for-profit incentives into public and nonprofit institutions.

The bundled service provider exception to the incentive compensation ban has served its initial purpose, but now has morphed into a vehicle for embedding for-profit incentives into public and nonprofit institutions. Across all industries, when a company engages in a practice known as white labeling—selling another company’s products under your own brand—consistency and quality control are major downsides.8 In higher education, where the product is intangible, the arrangements invite abuse, which is why it is time for the department to rescind the exception that allows bundled service providers to be paid according to their success in recruiting students.

What principles will guide the rescission of the guidance?

The U.S. Supreme Court has recently established a precedent regarding the timeframe needed to respond to the rescission of a federal guidance. In 2017, the Trump administration decided that President Obama’s policy allowing unauthorized immigrants who arrived in the United States as children to remain was contrary to the law and reversed it, causing mayhem.9 In 2020, the Supreme Court found that, even if the Obama policy was illegal, the government couldn’t simply reverse policy without considering the reliance interests at stake and the hardship rescission would cause.10 In other words, agencies would need to do their due diligence to responsibly wind down a long-relied-upon policy—even in cases where the policy runs counter to federal law.

The Department of Education, in revising its 2011 guidance, would have to follow that playbook, not only because the Supreme Court said it must, but also because it is the responsible thing to do. So should the department rescind the policy, it will likely announce that the effective date would be several months in the future, so that institutions could prepare for the transition.

An approach the department could take is to issue a memo that rescinds the third-party recruiter exemption:

- The memo should provide the relevant legal analysis to establish that the 2011 guidance is an untenable interpretation of the Higher Education Act (HEA) and undermines the policy purposes of the HEA.

- The memo should also announce a pause in certifying or recertifying schools that rely on the guidance until a new policy is established with the benefit of stakeholder input. To become eligible, or certified, to receive federal aid, all schools must enter into a program participation agreement (PPA) with the U.S. Department of Education.11 Absent a pause in certifying or recertifying schools that have relied on the 2011 guidance, the department runs the risk of ratifying that guidance.

- The memo should also set out a process and timeline to solicit comments on reasonable reliance on the guidance. This point in the process is important for determining the scale and scope of institutions’ reliance on the guidance and what alternatives would be viable in its absence. Input on specific proposals would be essential here, and one example would be to ask institutions how they would restructure agreements under a new policy.

- The memo should also distinguish unreasonable reliance. There are limits stated in the guidance that are being ignored by some institutions.12 For example, the guidance established that colleges and universities must operate independently from their third-party recruiters and must set admissions and enrollment goals without OPM interference. Such reliance is unreasonable and the analysis and comment process should function to draw distinctions between reasonable and unreasonable reliance to inform the approach for reversing the guidance.

- Finally, the memo should describe practices that may lead to immediate enforcement actions, along with aggravating and mitigating factors.13 This will provide clarity and incentivize good practices.

It is important to note that the delay in rescinding the guidance does not mean zero enforcement in the interim. Schools that are going beyond the guidance—which it seems, some are—should face swift and sure action to cut off their federal aid funds. The 2011 guidance was clear on the importance of the contractor(s) remaining separate (independent, unaffiliated) from the institution, both corporately and as a decision maker. Despite the guidance, there are clear cases of OPM overreach. Because no one has been watching, some schools have contracted with OPMs and in turn handed over over half of their enrollment, half or more of their revenue, and brought their contractors to the table on making key decisions about things such as enrollment targets, course offerings, and tuition pricing.14

Schools operating in this way arrived at this scenario because their agreements led them there. Such agreements often involve:

- the establishment of steering committees or other governing bodies that give the OPM an official and regular role in decision making;

- higher shares of revenue paid to the OPM as enrollment increases; and

- OPM control over marketing and recruiting, in the name of school.

To be clear: some OPMs have an enormous level of control over the content and modes of marketing and recruitment done in the name of the client institution. This control is established in writing, in the contracts. For example: the OPM AP is given leeway to use “a variety of means as determined by AP, in its reasonable discretion” by one of its partner institutions.15 Further, some contracts include an assumption of approval of marketing materials by the universities. These clauses state that “if the University does not respond to [the OPM] within a 10 day period, [the OPM] may assume that the marketing materials are approved.”

Similarly, some contracts give the OPM exclusive control over what are known as recruitment scripts—these are the scripts OPM employees who work on the sales or “enrollment advising” side of operations use when speaking to prospective students. Relinquishing control of these scripts is tantamount to the university playing reputational roulette.

Two other ways that universities have relinquished an inappropriate amount of control to their OPM contractors is through the setting of enrollment targets in conference with the contractor and through other forms of shared decision making. Some OPMs have official seats at the decision-making table of their client schools along with equal voting power on matters that include tuition pricing, enrollment goals, curriculum and course decisions, and course scheduling. These examples of OPM overreach are ripe for investigation and enforcement by the U.S. Department of Education, regardless of the current existence of the 2011 guidance.

Some OPMs have official seats at the decision-making table of their client schools along with equal voting power on matters that include tuition pricing, enrollment goals, curriculum and course decisions, and course scheduling.

What opportunities does this create for colleges?

Revising the third-party recruiter exemption will put schools on better footing for securing services they need to outsource. Under the status quo, many colleges are paying more than they would if online programs had not expanded under the cover of the 2011 bundled services guidance. Further, it is possible these inflated costs are passed on to students.

Revising the guidance will put schools in a position to (re)negotiate contracts that provide exactly what they need at prices that make sense. This is especially true for schools that have been engaged with OPMs for a decade or more. The general wisdom is that new online programs break even financially within a few years of operation, yet schools in decade-long and longer contracts extend and renew them under the same terms.

For example, Southeastern Oklahoma State University entered into an agreement with OPM Academic Partnerships (AP) in December 2015 to launch and manage an online Masters in Business Administration.16 The original contract between the parties set out a seven-year term where the university pays AP half of all tuition revenue collected from online program students. If the university wishes to exit the arrangement, it is required to give AP 270 days notice, and barring that action, the contract automatically renews for five years. Between 2015 and 2020, Southeastern Oklahoma State increased the number of programs AP managed from the one online MBA to forty-five programs, according to contract documents obtained by The Century Foundation. Each time a new program is added to the arrangement via addendum, those also take on a seven-year term, which means the addition of programs extends the length of the relationship between the school and its OPM. Over the years, each addition to AP’s scope of work with Southeastern Oklahoma State has been under the same terms of the December 2015 agreement, which involves a fifty–fifty revenue split between the parties. This means that Southeastern Oklahoma State, for its now-well-established online MBA which will reach its six-year anniversary this fall, continues to shell out half of all online MBA student revenue to a contractor, despite that contractor likely already breaking even on any upfront costs and risks it took on in the lead-up to the launch.

An analysis of invoices sent to Southeastern Oklahoma State by AP and acquired by The Century Foundation shows courses for the online MBA currently have some of the highest enrollment levels of the school’s online course offerings.17 Likewise, the university expanded its agreement with AP in late 2016 to include a series of programs aimed at professionals in the education field. According to AP invoices, Southeastern Oklahoma State’s online education courses also enjoy reliably high enrollment.

Master’s degrees that are the most well established as a result of the Southeastern Oklahoma State–AP agreement are pulling in the most revenue, but seven years in, the university is hamstrung in its ability to fully enjoy the fruits of that labor. Instead, the OPM earns increasingly wider profit margins as its own risk diminishes. What does AP’s cut of the revenue look like in raw figures? Invoices sent to the school from AP in 2019 and 2020 show a jump in enrollment and revenue over those two years. AP billed Southeastern Oklahoma State just over $3.5 million in 2019, and over $5.6 million in 2020.

In contrast, the University of Nebraska has managed its online programs by outsourcing specific functions to more specialized companies. This approach requires an upfront investment and a commitment to making future investments when needed, but it is more likely to cost less over the lifetime of the programs. Between 2015 and 2018, the university entered into agreements with companies including Ranku, InsideTrack, Thruline, and iDesignEDU.18 Across these four contractors, the university received services that facilitated student recruitment (marketing, website design, search engine optimization, lead generation support), internal and competitive analyses including secret shopping, and course design and redesign. Course design is likely the costliest service of those listed here, though a school’s necessary investment in instructional design depends on many factors including the number of courses at hand and whether or not design is needed from scratch (as opposed to redesigning or revising existing course assets).

Table 1

|

University of Nebraska Agreements with Third Parties for Online Program Management |

|||

| Date | Company | Services | Cost |

| 2015 | Ranku | Website design, search engine optimization, lead generation | $325,000 for one year of services |

| 2015 | InsideTrack | Internal and competitive analysis | $48,150 for analysis on twenty-nine programs |

| 2017 | iDesign | Course design and redesign | $35,000 per course design; $8,500 per course redesign |

| 2018 | Thruline | Marketing, analytics | $175,000 |

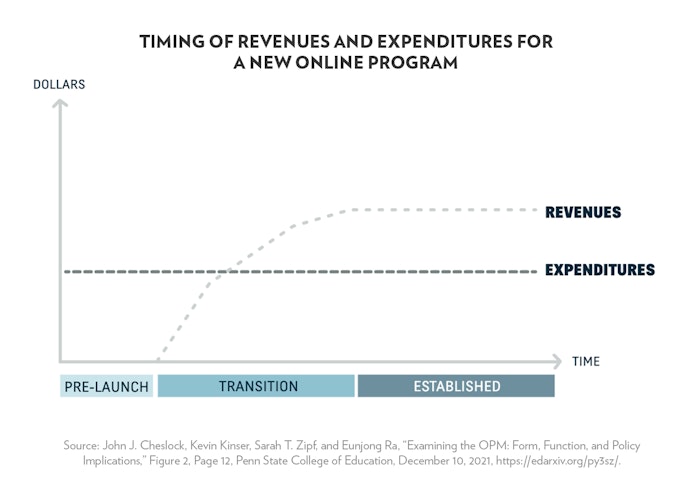

In their 2021 research on the OPM industry, researchers at the College of Education at Penn State presented a set of variables that college administrators should weigh when deciding how much upfront cost is involved and when to expect programs to break even.19 The break-even point is the point at which a long-term, high-revenue-share agreement is no longer in the interest of the institution.

Figure 1

This principle may be what prompted Louisiana State University (LSU) to in-source its online program management after a ten-year relationship with AP.20 LSU received a bundle of services from AP and in exchange, paid AP half of the tuition revenue raised from the programs. The school’s initial 2012 contract with AP set out a maximum $2 million payment amount from the institution to the OPM. (Contracts that are set on tuition-sharing terms often establish a maximum fee the client is willing to pay over the term of the arrangement.) That $2 million figure quickly shifted upward and by October 2017 was at $24.8 million. The LSU–AP agreement expired at the end of January 2022 and the institution has since moved its OPM services in-house. A vice provost at the institution was supported by leadership to spend time and resources during the last few years of the AP contract to move services in-house, which included the hiring of a team of people with experience in online higher ed marketing.

One of the draws to in-sourcing, or avoiding outsourcing to bundled service providers in the first place, is that in doing so, an institution retains complete control over how revenue is allocated to the services needed to sustain the program. Outsourcing to a bundled-service provider involves some acceptance that your online programs will be serviced and marketed by a third party that is also tasked with doing the same for your competitors. Because OPMs get paid more for successfully securing enrollments, it is no surprise that the finances underneath some outsourced programs look identical to what advocates have been sounding the alarm over in the for-profit college industry.21 The publicly traded OPM 2U, for example, devoted over half of its revenue between 2016 and 2020 to marketing and sales, according to financial statements.22 Many schools need the marketing and lead generation services that 2U provides, but they also need to be able to devote an appropriate amount to the actual educational experience of their students. Yet schools are left with half—and if they sign with 2U, less than half—of the tuition revenue generated to cover instructor and instructional design costs. There are many services listed in bundled contracts that the OPM agrees to perform, but in reality, universities are left to use a small cut of their own tuition revenue to do the heavy lifting.

Table 2

| OPM 2U’S REVENUES AND EXPENDITURES BY AREA, 2016–20 | |||

| Revenue | Marketing and Sales | Services and Support | Technology & Content Development |

| $2.3 billion | $1.2 billion | $383 million | $414 million |

| 54% of revenue | 35% of revenue | ||

|

Source: TCF analysis of 2U annual reports, 2016-2020, https://www.sec.gov/edgar/search/#/q=2u&dateRange=10y&filter_forms=10-K. |

|||

What can my institution do right now?

It is important to remember that only contracts that include recruiting are potentially implicated. In a post-guidance world, two options for schools currently in tuition-sharing arrangements that include recruitment would have the following options:

- remove recruiting from the bundle and continue paying the contractor on a revenue-sharing basis, or

- continue contracting with the OPM for recruitment and shift the payment terms to a flat fee structure.

The instinct for institutions to join OPMs in their opposition to this policy change will be strong because the prospect of changing an ingrained practice could seem daunting, but college leaders should ignore knee-jerk reactions and instead take stock of their school’s programs and what it truly costs to sustain them. Now is the time for colleges and universities to review arrangements they have with online program management companies and to decide if the terms of the deals allow for those costs to be covered in a just and equitable way. No matter the answer, college leaders can be certain the sky is indeed not falling and that they instead have the upper hand in renegotiating contracts so that their terms do not violate the incentive compensation ban and allow their institution to regain control of their online programs.

Notes

- Doug Lederman, A Federal Look at Managing Online Programs, Inside Higher Ed, February 3, 2021, https://www.insidehighered.com/news/2021/02/03/government-accountability-office-exploring-landscape-companies-help-colleges-go; Lisa Bannon and Andrea Fuller, “USC Pushed a $115,000 Online Degree. Graduates Got Low Salaries, Huge Debts,” Wall Street Journal, November 9, 2021,

https://www.wsj.com/articles/usc-online-social-work-masters-11636435900. - Supreme Court of the United States, “Syllabus: Department Of Homeland Security et al. v. Regents Of The University of California et al.,” October 2019, https://www.supremecourt.gov/opinions/19pdf/18-587_5ifl.pdf.

- Paul Fain, “Brand New Online Heavies,” Inside Higher Ed, October 10, 2012, https://www.insidehighered.com/news/2012/10/10/nonprofit-colleges-spark-new-competition-online-study-finds.

- “Implementation of Program Integrity Regulations,” DCL GEN-11-05, U.S. Department of Education, March 17, 2011, https://fsapartners.ed.gov/knowledge-center/library/dear-colleague-letters/2011-03-17/gen-11-05-subject-implementation-program-integrity-regulations; The federal ban on incentive payments to recruiters is contained in Section 487(a)(20) of the Higher Education Act of 1965 (20 U.S.C. 1094(a)(20)).

- IPEDS Data Explorer, Table 3. Number and percentage distribution of students enrolled at Title IV institutions, by control of institution, student level, level of institution, distance education status of student, and distance education status of institution: United States, fall 2020, https://nces.ed.gov/ipeds/search?query=&query2=&resultType=all&page=1&sortBy=date_desc&overlayTableId=29450.

- Stephanie Hall and Taela Dudley, “Dear Colleges: Take Control of Your Online Programs,” The Century Foundation, September 12, 2019, https://tcf.org/content/report/dear-colleges-take-control-online-courses/; Lisa Bannon and Andrea Fuller, “USC Pushed a $115,000 Online Degree. Graduates Got Low Salaries, Huge Debts,” Wall Street Journal, November 9, 2021, https://www.wsj.com/articles/usc-online-social-work-masters-11636435900.

- Robert Shireman, “The Sketchy Legal Ground for Online Revenue Sharing,” Inside Higher Ed, October 30, 2019, https://www.insidehighered.com/digital-learning/views/2019/10/30/shaky-legal-ground-revenue-sharing-agreements-student-recruitment.

- Carla Tardi, “White Label Product Definition,” https://www.investopedia.com/terms/w/white-label-product.asp.

- “Memorandum on Rescission of Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA),” U.S. Department of Homeland Security, September 5, 2017, https://www.dhs.gov/news/2017/09/05/memorandum-rescission-daca.

- Supreme Court of the United States, “Syllabus: Department Of Homeland Security et al. v. Regents Of The University of California et al.,” October 2019, https://www.supremecourt.gov/opinions/19pdf/18-587_5ifl.pdf.

- Yan Cao, “Predatory Colleges Think They Are Too Flawed to Fail. Biden’s Department of Education Should Prove Them Wrong,” The Century Foundation, September 9, 2021, https://tcf.org/content/commentary/predatory-colleges-think-flawed-fail-bidens-department-education-prove-wrong/.

- Robert Shireman, “How For-Profits Masquerade as Nonprofit Colleges,” The Century Foundation, October 7, 2020, https://tcf.org/content/report/how-for-profits-masquerade-as-nonprofit-colleges/; Stephanie Hall, “Invasion of the College Snatchers,” The Century Foundation, September 30, 2022, https://tcf.org/content/report/invasion-college-snatchers/.

- See: Memo from Under Secretary Ted Mitchell to Federal Student Aid COO James Runcie (“Mitchell Memo”), June 2, 2015, https://drive.google.com/file/d/1LnF0AMtB0GmeCUa9Kkzp9VXiWahq6khK/view?usp=sharing; and Memo from Deputy Secretary William Hansen to Federal Student Aid COO Terri Shaw (“Hansen Memo”), October 30, 2022, https://drive.google.com/file/d/1HBFYMcowR5Bt8YUBOYC1g5DzlriSZtFf/view?usp=sharing.

- Stephanie Hall, “Invasion of the College Snatchers,” The Century Foundation, September 30, 2022, https://tcf.org/content/report/invasion-college-snatchers/.

- Lamar University and Academic Partnerships contract obtained via public records request, https://drive.google.com/drive/folders/1sEO9IzeG-5_WoUKaLMbxWc3pJfVQF88l?usp=sharing.

- Southeastern Oklahoma State University and Academic Partnerships contract obtained via public records request, https://drive.google.com/drive/folders/1JhL9WYpN6GaoQUIyAimLd_Njj8Gkj09z?usp=sharing.

- Out of concern for student privacy, these documents are only available upon request.

- University of Nebraska and iDesignEDU contract obtained via public records request, https://s3-us-west-2.amazonaws.com/production.tcf.org/assets/OPM_contracts2/University+of+Nebraska+%26+iDesignEDU.pdf; University of Nebraska and Ranku contract obtained via public records request, https://s3-us-west-2.amazonaws.com/production.tcf.org/assets/OPM_contracts2/University+of+Nebraska+%26+Ranku.pdf; University of Nebraska and Thruline contract obtained via public records request, https://s3-us-west-2.amazonaws.com/production.tcf.org/assets/OPM_contracts2/University+of+Nebraska+%26+Thruline.pdf; University of Nebraska and Inside Track contract obtained via public records request, https://s3-us-west-2.amazonaws.com/production.tcf.org/assets/OPM_contracts2/University+of+Nebraska+%26+InsideTrack.pdf.

- John J. Cheslock, Kevin Kinser, Sarah T. Zipf, and Eunjong Ra, “Examining the OPM: Form, Function, and Policy Implications,” Penn State College of Education, December 10, 2021, https://edarxiv.org/py3sz/.

- Louisiana State University and Academic Partnership contract obtained via public records request, https://s3-us-west-2.amazonaws.com/production.tcf.org/assets/OPM_contracts2/Louisiana+State+University+%26+Academic+Partnerships.pdf.

- Stephanie Hall, “How Much Education Are Students Getting for Their Tuition Dollar?” The Century Foundation, February, 28, 2019, https://tcf.org/content/report/much-education-students-getting-tuition-dollar/.

- See annual reports filed by 2U to the Securities and Exchange Commission, https://www.sec.gov/edgar/search/#/q=2u&dateRange=10y&filter_forms=10-K.