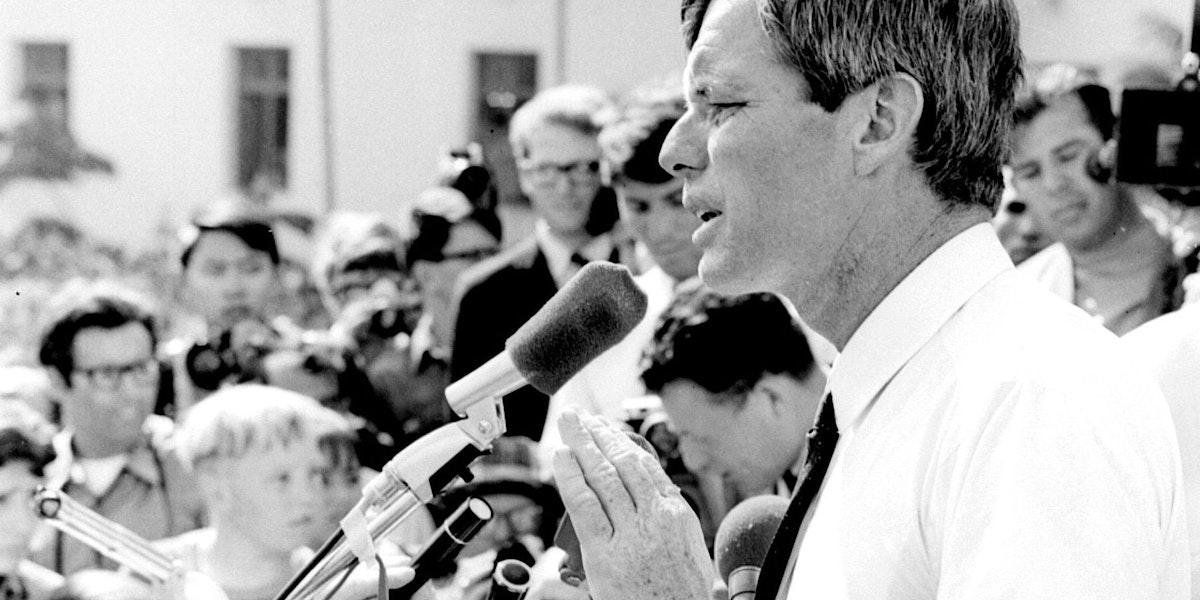

Robert F. Kennedy’s 1968 campaign for president, launched fifty years ago this spring, holds a special place in the hearts of many progressives. At a time when working-class whites and black voters were at each other’s throats, Kennedy (RFK) managed to forge a remarkable coalition by communicating to both groups that he cared about their futures. Running as a candidate deeply committed to advancing civil rights, Kennedy nevertheless was able to attract many working-class white voters, some of whom had voted for segregationist George Wallace in a previous election.

In the 2016 election, by contrast, progressives were stunned when working-class white voters moved in the opposite direction. Polling analysis finds that 22 percent of non-college-educated whites who supported Barack Obama in the past switched to Donald Trump, a candidate hostile to the civil rights of Mexican Americans, Muslims, and African Americans.1 Trump won the white non-college-educated vote by a stunning 41 percentage points, which tipped the presidential election.2 In all, six states flipped from Obama to Trump.3

This report makes three central points. First, it outlines the evidence suggesting Kennedy achieved a remarkable political coalition in time of strong political antagonism. Although contemporary witnesses to the campaign believed Kennedy’s appeal to be strong, some historians have subsequently questioned RFK’s ability to attract working-class whites. This report seeks to debunk the debunkers, drawing upon polling data and precinct results in key states to suggest Kennedy had powerful appeal with working-class blacks and whites alike.4

Second, along the way, the report spells out the apparent reasons why Kennedy was able to appeal to working-class white and black voters at a time of great tension between the groups. In the end, he was able to communicate that he cared about both groups in a way that few politicians can today by respecting both their interests and their legitimate values. Unlike right-wing urban populists, he was inclusive of minority populations, and unlike today’s liberalism, Kennedy placed a priority on being inclusive of working-class whites. In short, he was a liberal without the elitism and a populist without the racism.

Third, the report seeks to draw lessons from the 1968 campaign for progressives today. Although the campaign involved a unique candidate—the brother of a slain president—at a political moment very different than our own, RFK’s candidacy is more than a mere historic curiosity. Kennedy advanced critical themes and approaches that translate across time and candidates to inform the approach of progressives today. This section suggests a number of concrete policies that could prove important to restoring the multiracial, class-based coalition that Kennedy was able to forge.

RFK’s 1968 Campaign for President

On March 16, 1968, Robert F. Kennedy announced that he was challenging incumbent president Lyndon B. Johnson (LBJ) for the Democratic presidential nomination. Kennedy needed little introduction to the country. The younger brother of slain president John F. Kennedy (JFK), Robert Kennedy had managed JFK’s campaigns for Congress, the Senate, and the presidency, and had served as the Kennedy administration’s attorney general, where he fought for civil rights and advised his brother in the Cuban Missile Crisis. The year following JFK’s 1963 assassination, RFK was elected a U.S. senator from New York, where he became a champion of the nation’s underdogs, highlighting the need to address poverty and the plight of blacks, Hispanics, and Native Americans. As senator, he also became a leading opponent of LBJ’s Vietnam War.

The Challenge of Forging and Unlikely Coalition

But as he began his 1968 campaign, RFK faced a major political dilemma. The New Deal Coalition of working-class whites and blacks, which had supported progressive candidates for more than three decades, was in tatters, rent apart by racial strife and resentment. Should he try to bring these groups back together, or instead seek a new coalition of highly-educated whites and minority voters?

Restoring the New Deal Coalition would be tough, because it had been an historical aberration. For centuries, working-class whites and blacks had been kept apart by wealthy white interests who were terrified of an alliance. Populist movements to align the groups based on their shared class interest were attempted over the years, including during Reconstruction, but were usually derailed by demagogic appeals to racism.5 Among the most tragic stories was that of Tom Watson, a Georgia populist, who began his career as an idealist, arguing for racial unity: “the accident of color can make no difference in the interests of farmer, croppers, and laborers,” he declared. But when that tack was foiled, Watson became, by the end of his career, a rabid racist who stood squarely for white supremacy.6

As president, Franklin Delano Roosevelt (FDR) had managed to forge a multi-racial class-based coalition during the New Deal, but he had done so mostly at a terrible cost: by looking the other way at egregious violations of the civil rights for black people. As Leo Casey of the Albert Shanker Institute notes, “Too often, the ‘common good’ of the New Deal left African Americans and other people of color on the outside of what was ‘common.’”7 When the civil rights movement challenged racial segregation and white supremacy in the 1960s, some white working-class voters, particularly in the South, began to defect to the conservative cause.

Passage of the 1964 Civil Right Act to outlaw discrimination in employment and education was a monumental advancement for human freedom but did not sit well with many Southern whites, nor with some white working-class voters in the North. In 1964, when Alabama’s segregationist governor George Wallace challenged LBJ for the Democratic presidential nomination, he stunned political observers by getting strong support from working-class whites in Wisconsin, Maryland, and Indiana.8

Despite some apparent discomfort over the Civil Rights Act, most working-class whites in the North stuck with the Democratic Party. In the 1964 presidential election, LBJ lost the South to Republican Barry Goldwater over civil rights, but nationally, Johnson won a solid majority of working-class whites, as John Kennedy had.9

Many civil rights leaders remained optimistic about keeping the coalition together. Martin Luther King Jr., who personally experienced hatred in white working-class communities in his fight for civil rights, nevertheless argued that the push for greater economic equality could provide the potential “for a powerful new alliance.” Speaking of lower-income whites, King suggested, “White supremacy can feed their egos but not their stomachs.”10

But the white backlash grew among Northern whites in response to racial rioting in the 1960s. By 1968, as journalist David Halberstam noted, “The easy old coalition between labor and Negroes was no longer so easy; it barely existed. The two were among the American forces most in conflict.”11 Many working-class white voters were also hawkish on foreign policy, and objected to candidates who were dovish on Vietnam.

As a result, when Kennedy began his 1968 campaign, the natural step as a pro-civil-rights, anti-Vietnam politician was to try to build a political coalition of African Americans, Latinos, college students, and upper-middle class educated white liberals. But as fate would have it, a particular sequence of events put that coalition out of easy reach by the time Kennedy joined the campaign. By then, Kennedy faced in the contest not only Lyndon Johnson, but a third candidate, Minnesota U.S. senator and anti-war activist Eugene McCarthy.

A year earlier, Kennedy had been approached by peace activists to oppose Johnson’s reelection but had hesitated. Instead, McCarthy entered the race as an anti-war candidate, and performed surprisingly well in the New Hampshire Democratic presidential primary. Only then did RFK enter the race. By that time, white students and upper-middle class liberals were mostly committed to McCarthy and many were infuriated when Kennedy belatedly jumped into the race. “[T]he campus had always been considered as Kennedy’s base,” writers Lewis Chester, Godfrey Hodgson and Bruce Page noted. “He had been nurturing this constituency for years; he lost it in a month.”12 The authors noted, “the awkward existence of Eugene McCarthy” forced Kennedy to pursue “the wrong kind of middle-class voters”—less-educated whites who were part of the backlash against racial progress and the peace movement.13

As Kennedy began the race, he decided to enter the Indiana primary, scheduled for May 7, as his first test. Shortly after Kennedy entered the presidential race, LBJ stunned observers by dropping out of the contest, paving the way for his vice president, Hubert H. Humphrey, to participate. In Indiana, the conservative Democratic governor, Roger Branigin, ran as a stand-in for the Johnson administration, a common practice in those days.

Appealing to white backlash voters of the type who supported George Wallace in Indiana was a tall order for Robert Kennedy. As attorney general, RFK had been a staunch proponent of civil rights. In 1961, after white thugs attacked Freedom Riders seeking to desegregate bus lines, RFK ordered marshals to Montgomery, Alabama. In 1962, he supported James Meredith’s efforts to enroll at the University of Mississippi as the first black student. A year later, RFK urged his brother to submit strong civil rights legislation to Congress. As a U.S. senator, RFK traveled to South Africa and to Mississippi to fight for racial and economic justice and forged a profound connection with black voters.14

If RFK was at the opposite end of civil rights spectrum from Wallace, voters knew it. In a 1968 “thermometer” poll of twelve possible presidential candidates sponsored by the University of Michigan, Robert Kennedy ranked the very highest among black voters, and George Wallace the very lowest.15 Likewise, in a May 1968 Harris survey regarding seven presidential candidates, Robert Kennedy was identified as the most likely to “speed up” racial progress (69 percent), while George Wallace was the least likely (5 percent).16

Figure 1

RFK’s opponents—McCarthy, and the Humphrey-Branigin team—were much less identified with black voters. In the Harris survey, less than half viewed Humphrey as supporting “racial progress speed-up,” and only about one-third viewed Eugene McCarthy in that way. Although Humphrey had first made his name in the 1940s supporting civil rights, by the 1960s, RFK was more closely identified with the struggle. Indeed, RFK attacked the Johnson-Humphrey administration for not being aggressive enough in responding to the February 1968 Kerner Commission report that said urban rioting was largely the result of white racism in employment, education, and housing.17 McCarthy, meanwhile, tended to focus his campaign on affluent white suburbs rather than struggling black communities, whereas Kennedy was known for attracting large, enthusiastic crowds in black inner-city neighborhoods.18

But in Indiana, given McCarthy’s strength among upper-middle class whites, Kennedy would have little choice but to try to forge a coalition of black voters and working-class whites, many of whom had supported George Wallace in the past. In the 1964 Indiana Democratic primary—just a year after Wallace had vowed “Segregation now! Segregation tomorrow! Segregation forever!”—Wallace received nearly 30 percent of the vote in the Indiana Democratic primary challenge.

Wallace’s appeal among whites was much stronger among those lower down the education and occupation scales. In a 1967 national Gallup pro-con survey, Wallace was viewed favorably by those with a Grammar school education (54 percent to 32 percent), but unfavorably by those with a university education (30 percent to 65 percent). He was favored by manual workers (51 percent to 36 percent) but disfavored by non-manual workers (31 percent to 60 percent).19 In Gary, Indiana, a Harvard University study found that blue-collar workers were three times more likely to support Wallace than white-collar workers.20

Televised violence by white authorities against peaceful black protesters in the South helped boost white support for civil rights in the early 1960s, but urban rioting, beginning in Watts neighborhood of Los Angeles, California, in 1965, and spreading throughout the country in 1966, 1967, and 1968, broadened the white backlash against civil rights. In 1966, the country saw 43 race riots; in 1967, 164 riots left 83 people dead. And 1968 was the peak year for major civil disturbances.21 The political impact was powerful: “For several decades, Americans have voted basically along the lines of property,” Richard Scammon and Ben Wattenberg wrote in 1970. “Suddenly, sometime in the late 1960s, ‘crime,’ and ‘race’ and ‘lawlessness’ and ‘civil rights’ became the most important domestic issues in America.”22

Rioting hurt the progressive cause because, as David Halberstam noted, “It was the rage, not the causes of it, which showed up on white television sets.”23 By August, 1967, a Gallup poll showed that 32 percent of the American public had changed their attitude toward black people in the previous several months, and “virtually all in this group,” the poll summary found, “have less regard or respect for Negroes now than formerly.”24

As it turned out, the issues of racial injustice—and race rioting—would be at the epicenter of the Indiana primary. On April 4, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., an apostle of nonviolence, was assassinated by a white man in Memphis, Tennessee. Against the advice of police, Kennedy entered the Indianapolis ghetto that night and, speaking without notes, gave one of the great speeches of his career. He informed the shocked crowd that King had been killed and reminded them that he, too, had lost a family member to gun violence. He declared:

We can move in [the] direction [of] greater polarization—black people amongst black, white people amongst white, filled with hatred toward one another. Or we can make an effort, as Martin Luther King did, to understand and comprehend. . . . What we need in the United States is not division; what we need in the United States is not hatred; what we need in the United States is not violence or lawlessness, but love and wisdom and compassion toward one another, and a feeling of justice toward those who still suffer within our country, whether they be white or whether they be black.25

Indianapolis was one of the few large cities that did not burn that night.26 Greensboro, Nashville, Chicago, Baltimore, Detroit, and Washington all went up in flames. In total, 110 cities saw rioting, resulting in 39 deaths, 2,500 injuries, and 28,000 arrests. In the nation’s capital, federal troops had to guard the White House. Machine guns were posted on the steps of the Capitol building. As a result, Chester, Hodgson and Page noted, “the 1968 campaign would be fought on Wallace’s chosen ground.”27

Kennedy’s Approach to Building the Coalition

If the challenge was daunting, Kennedy had a plan. Whereas progressives typically told working-class Americans they will look out for their interests, and conservatives typically told these voters they support their values, Kennedy would emphasize connection to both their economic interests and their legitimate values.28 Kennedy would underline common class interests as progressives traditionally did. But he would do more, and suggest that he respected working-class values of hard work and respect for the law. He was not going to backtrack on his commitment to civil rights or his commitment to pursuing peace in Vietnam. But he would augment the pursuit of racial justice and peace with a commitment to toughness—on crime, on welfare, and on national security. This message was reinforced by a personal history of strength that was meant to give working-class whites and blacks the sense that he respected their American values as well as their interests.

1. Emphasizing Common Class Interests

Kennedy believed that racial injustice needed fighting tooth and nail, but he also believed, with the passage of civil rights laws outlawing discrimination, that class inequality was the central impediment to progress for both black and white people. In Indiana, Kennedy told reporter David Halberstam that “it was pointless to talk about the real problem in America being black and white, it was really rich and poor, which as a much more complex problem.”29 Kennedy told journalist Jack Newfield, “You know, I’ve come to the conclusion that poverty is closer to the root of the problem than color. I think there has to be a new kind of coalition to keep the Democratic party going, and to keep the country together. . . . Negroes, blue-collar whites, and the kids. . . . We have to convince the Negroes and the poor whites that they have common interests.”30

During the campaign, RFK continually pounded away at the ability of rich people to escape taxes by exploiting loopholes. He offered “A Program for a Sound Economy,” which the Wall Street Journal denounced in an editorial entitled, “Soak the Rich.”31 Lewis Kaden, who was primarily responsible for the proposal, says it was in the classic populist tradition “of attacking big corporation and rich individuals who weren’t paying their fair share of taxes.”32 Recognizing that tax reform was a complicated issue, he tried to cut through the fog by calling for a minimum 20 percent income tax for those who earned over $50,000 (in 1968, a considerable sum) in order “to prevent the wealthy from continuing to escape taxation completely.”33 RFK speechwriter Jeff Greenfield recalled in an interview that on the stump, Kennedy was not afraid to name names. “He would constantly cite” oil tycoon H. L. Hunt. Kennedy “would use statistics of 200 people who made $200,000 a year or more and paid no taxes. . . He kept coming back to those 200 people . . . and then he’d say: ‘One year Hunt paid $102. I guess he was feeling generous.’ If you think about it, there is no better populist issue than that issue.”34

Progressives frequently hit issues of economic inequality in campaigns, but RFK’s message was particularly strong, which earned him the enmity of business leaders. A survey conducted by Fortune magazine found Kennedy was the most unpopular presidential candidate among business leaders since Franklin D. Roosevelt. “While President Kennedy was never a great favorite among businessmen,” a March 1968 Fortune article noted, “the suspicion with which he was regarded is nothing compared to the anger aroused by his younger brother.” The survey of business leaders found that “mention of the name Bobby Kennedy produced an almost unanimous chorus of condemnation . . . there is agreement that Kennedy is the one public figure who could produce an almost united front of business opposition.”35 (A month after Kennedy’s assassination in June 1968, Hubert Humphrey told Kennedy aide Ted Sorensen that much of Humphrey’s earlier financial support had dried up because it had been driven by hostility to RFK).36

But Kennedy’s appeal to working-class whites and blacks didn’t end with economics. He also knew that it was important that the populist appeal cut across social issues and national security questions as well.

2. Navigating the Social Issues: Crime, Welfare, and Affirmative Action

By 1968, progressives knew all too well that an economic message would not get through to working-class whites unless it was accompanied by a respect for their values on issues such as crime and welfare.

Race riots were the central issue in the 1968 campaign and Kennedy sought to walk a line that was both sensitive to racial injustices which gave cause to black anger and also made clear that looting and violence would never be tolerated no matter how legitimate the underlying grievance. In this way, Kennedy distinguished himself from both right-wingers who spoke only of “law and order” and self-styled liberals for whom the term “law and order” was an anathema.37

Eugene McCarthy, for example, refused to utter the phrase.38 And many McCarthy supporters attacked Kennedy for stressing the crime issue. Reporter Jack Newfield noted, “these McCarthy backers usually lived in low-crime expensive suburbs or luxury apartment buildings with two doormen and elaborate surveillance systems.”39

Kennedy would have none of that. “Though a man of growing compassion,” Chris Matthews writes, “he believed in law and order and didn’t hesitate to employ the phrase.”40 Kennedy did not want to cede the term to right wingers who could imply that liberals were for lawlessness and disorder. In Indiana, he took the advice of campaign officials to speak of himself not as the former attorney general but to tell audiences, “I was the chief law-enforcement offer of the United States. I promise if elected, I will do all in my power to bring an end to this violence. We needn’t have to expect this violence summer after summer.”41 RFK aide Gerard Doherty recalled, “I said if he was going to win, he has to conduct a campaign for sheriff of Indiana. And he did.”42

Early on in the campaign, Kennedy told his media advisor Donald Wilson, “I want a law and order ad. Why don’t we have a law and order ad?” So the campaign developed several on this theme. One advertisement, signed by one hundred law enforcement officials, said Robert Kennedy was the best candidate able to deal with violence in the streets. Wilson recalls, “We had some of the most important law enforcement officers in the United States flying into Indianapolis” to make an ad.43

In another advertisement, shot with Kennedy speaking to factor workers, RFK declares, “We’re going to have law and order in the United States. One thing we have to establish is that we won’t tolerate lawlessness and violence.” In another advertisement, Kennedy tells an audience in Columbus, Indiana: “I don’t think we have to accept the idea that summer after summer we’re going to have violence. I don’t think we have to accept the idea that summer after summer we’re going to have looting. And I don’t think we have to accept the idea that the stain of bloodshed is going to be ever across our country.”44

The message got through. At one point during the presidential campaign, Richard Nixon remarked to journalist Theodore White, “Do you know a lot of these people think Bobby is more a law-and-order man than I am!”45

But at the same time, Kennedy, unlike many conservatives, always balanced his call for law and order with a call for justice. In his television ad with factory workers, for example, after speaking of the need for law and order, he also made clear that the country needed to make sure “that people are going to be treated with justice. And that a man has the opportunity to obtain a job, and has the opportunity to obtain decent housing.”46 Kennedy believed that social justice and law and order were complementary, not contradictory, approaches to fighting crime and providing opportunity.

During the campaign, Kennedy also spoke of “another kind of violence, slower but just as deadly, destructive as the shot or the bomb in the night. This is the violence of institutions; indifference and inaction and slow decay. This is the violence that afflicts the poor, that poisons relations between men because their skin has different colors. This is the slow destruction of a child by hunger, and schools without books, and homes without heating.”47

On the racially charged issue of welfare reform, RFK emphasized the need for more jobs as a way of empowering people. His campaign slogan in Indiana and elsewhere was “Won’t you help Robert Kennedy give people a hand up rather than a hand out?”48 He argued, “The answer to the welfare crisis is work, jobs, self-sufficiency, and family integrity; not a massive new extension of welfare; not a great new outpouring of guidance counselors that give poor advice.”49

Kennedy’s central message was not that government needed to crack down on abuse, but that recipients would be better off if government invested in jobs. In a television commercial, Kennedy declared, “I think welfare is demeaning and destructive of the human being and of his family. But instead of welfare, instead of the dole, instead of a handout, what we need in the United States is to provide jobs for all of our people.”50 Kennedy didn’t blame welfare recipients; he blamed the system. “We need jobs, dignified employment at decent pay; the kind of employment that lets a man say to his community, to his family, to his country, and most important to himself—‘I helped to build this country. I am a participant in its greatest public venture.’”51

The appeal wasn’t to racial resentment. He told no stories of “welfare queens” abusing the system as other later candidates would. Indeed, Kennedy once said he recognized that welfare is among the things black people hate most in American society.52 His was an appeal to American values that united working-class black and white people honoring the dignity of work.

On the contentious issue of racial preferences, as well, Kennedy articulated a position in favor of nondiscrimination across the board. His stance was to be pro-civil rights but anti-preference. Kennedy spoke of a “special obligation” owed to black people for years of slavery and segregation but proposed as a remedy an aggressive expansion of racially inclusive social mobility programs, not racial preferences. He favored outreach to black people for job openings but not a change in the performance standard for hiring.53

Kennedy’s position on affirmative action was consistent with Martin Luther King Jr.’s. King spoke of the need to address our nation’s egregious history of slavery, segregation, and discrimination. But instead of advocating a Bill of Rights for the Negro, King suggested a Bill of Rights for the Disadvantaged. King wrote: “While Negroes form the vast majority of America’s disadvantaged, there are millions of white poor who would also benefit. . . . It is a simple matter of justice that American, in dealing creatively with the task of raising the Negro from backwardness, should also be rescuing a large stratum of the forgotten white poor.”54 King knew that race-based preferences would split the multi-racial coalition he and other progressives were seeking to forge. King wrote: “It is my belief that many white workers whose economic condition is not too far removed from the economic condition of his black brother, will find it difficult to accept a ‘Negro Bill of Rights’ which seeks to give special consideration to the Negro in the context of unemployment, joblessness etc. and does not take into sufficient account their plight (that of the white worker).”55

3. Showing Toughness on National Security Issues

On issues of national security and war and peace, Kennedy took a principled position in opposition to the Vietnam War—whose very morality he questioned—but threaded the needle in a way that also made clear to working-class voters that he differed sharply from upper middle-class white college students who dodged the draft or even sympathized with the North Vietnamese Communists.

On the one hand, RFK raised deep moral questions about the Vietnam War. “Can we ordain to ourselves the awful majesty of God—to decide what cities and villages are to be destroyed, who will live and who will die, and who will join the refugees wandering in a desert of our own creation?” he asked during the 1968 campaign.56 But his position never translated into being soft on Communism or sympathetic to college students who were avoiding service in the war.

Kennedy argued in his stump speech: “I am not in favor of unilateral withdrawal from Vietnam, that would hurt us in Southeast Asia.”57 He wrote in his book, To Seek a Newer World, “The overwhelming fact of American intervention has created its own reality. . . . Tens of thousands of individual Vietnamese have staked their lives on our presence and protection.” These people, he suggested, “cannot suddenly be abandoned for forcible conquest of a minority.”58 Campaign aide Jeff Greenfield recalls, “There was an effort from the very beginning not to run simply as a peace candidate.” RFK made clear, “I am not running for the president of SANE,” an anti-war group.59

In language likely to resonate with working-class people of all races who disproportionately sent their offspring to Vietnam, Kennedy actively confronted college students who received draft deferments during Vietnam. Although the student draft deferments were supported by the public by a 54 percent to 31 percent margin, Kennedy attacked them as unfair.60 At Notre Dame University, Kennedy was booed for saying college draft deferments should be abolished. “You’re getting the unfair advantage while poor people are being drafted,” Kennedy said.61 Unlike McCarthy, Kennedy refused to promise amnesty to draft evaders.

Kennedy, who himself had served in the U.S. Navy, reminded voters that he had long been a “cold warrior.” In television advertisements employed in Indiana and Nebraska, the Kennedy campaign pieced together clips from RFK’s 1962 trip to Poland and his meeting with Communist leaders. “He confronted our critics, head on,” a narrator declares as Kennedy is shown telling Communist officials, “And the Soviet Union puts a wall up to keep their workers’ paradise.” Kennedy continues, “I appreciate your frankness, and I think you would expect the same from me.” Smiling, he adds, “And you’re going to get it.”62 In case voters had forgotten it, RFK’s ads also harkened back to his involvement in the Cuban Missile Crisis, when the United States stared down the Soviets and won the removal of their missiles.

Kennedy’s message of resolve on national security appeared to penetrate with Indiana voters. Astonishingly for a peace candidate, RFK polled as well among those who favored LBJ’s conduct of the Vietnam War as among those who opposed it.63

4. A Different Kind of Liberal Candidate

In addition to RFK’s stances on economic, social, and national security issues, he stood apart from many liberals because of his personal history—as a devout Catholic, an individual who prized physical toughness, and someone who, despite his family wealth, felt connected to working-class families and disconnected from upper-middle class white liberals.

Kennedy’s Catholicism was well-known at a time when anti-Catholic prejudice was still raw. RFK embraced the Catholic Church more closely than did JFK, and, more than his brother, took poet Robert Frost’s advice to heart: “Be more Irish than Harvard.” RFK and his wife Ethel had ten children, the fact of which the campaign continually reminded voters. In one television advertisement, RFK points to a young girl and says, “we have five of those at home,” and, pointing to a boy, “as well as a lot of those.”64 In another advertisement, RFK is showing playing football with his kids as a voice intones, “A man with ten children can’t avoid concern about the future.”65 As Harvard professor Robert Coles, a Kennedy adviser, noted, all of those children were a powerful symbol to working-class Catholic families.66

The public also knew that Kennedy prized physical toughness and had a reputation for “ruthlessness,” an attribute rarely associated with compassionate liberals. As a former aide to Senator Joe McCarthy in pursuit of purported Communists, and later as a staffer to the Rackets Committee prosecuting Jimmy Hoffa for union corruption, “Robert Kennedy had ‘cop’ written all over his public image,” Ted Sorensen wrote.67 Unlike most liberal Senators, RFK always said hello to the police officers, Chris Matthews notes.68 “The very qualities that the upper-middle class liberal intelligentsia did not like about him,” says Robert Coles, “are what working-class white people liked.”69

During the Indiana campaign, Kennedy emphasized the value of manual labor over philosophizing. In one television commercial, Kennedy is shown speaking to an audience of factory workers; a narrator says: “There’s one thing Robert Kennedy knows for sure. When he talks to men who do the real work in this country, he’s talking with people who aren’t afraid of a new challenge.”70

In fact, Chris Matthews reports that when Bobby Kennedy worked on Adlai Stevenson’s 1956 presidential campaign, he perceived that Stevenson, a renowned intellectual, couldn’t seem to make hard decisions and noticed that he “talked over people’s heads” at campaign stops. Kennedy developed a “contempt for liberals,” Matthews writes, and actually ended up voting for Eisenhower.71 So determined was Kennedy to distance himself from the liberal brand, RFK personally insisted years later on deleting the word “liberal” from his speeches and replacing it with “humane.”72

The message seemed to get across. A 1968 Harris poll found that by 65 percent to 19 percent, Americans believed Kennedy was “courageous and unafraid to follow his convictions.”73 Kennedy aide Adam Walinsky said, “The polls would show up that he was so tough that he scared people. . . . Everybody in the country knew that he was a tough son of a bitch.”74 One factory worker told Robert Coles, “We used to say in the factory, he’s one of us who made good and knows how to think and hasn’t lost touch with the ordinary man.”75 Other white workers told Coles, “This guy isn’t going to use us to show those rich Harvard-types what a great guy he is. He may be for them [African Americans] but he’s for us too.”76 Advisor Justin Feldman recalled that in Indiana, pollsters found that “both sides,” black and white, “trusted [RFK] not to take crap from the other side.”77 Kennedy was, on the hand, a candidate with a strong moral message about civil rights, poverty, and an unjust war; but he was also someone who believed in exercising power—an increasingly rare combination.78

Kennedy’s Remarkable Coalition

As Kennedy campaigned in Indiana, hard-bitten reporters saw evidence that a remarkable coalition of working-class white and black voters appeared to be coalescing around a single candidate.

Kennedy’s strong appeal among black voters was well expected. But reporter Theodore White was struck that cities such as South Bend and Gary, Indiana, white working-class men came out to see Kennedy, “a rare sight in daytime political campaigning.”79

Many journalists were particularly struck by an extraordinary motorcade on May 6—the day before the primary election—that ran through Indiana’s steel towns of Gary, Hammond, and Whiting. The year before, the City of Gary had divided sharply over the city mayoral election; white precincts voted white, black for black. Although the whites in Gary were registered Democratic by a five-to-one margin, 90 percent voted for the white Republican.80

But as RFK began a grueling, nine-hour motorcade through industrial northern Indiana, many of the steel-mill families, black and white, came out to greet him. As the motorcade entered Gary, the city’s black mayor, Richard Hatcher, climbed in to sit next to Kennedy on one side. On the other side of the candidate was Tony Zale, the former middleweight boxing champion who was a native-son hero of Gary’s Slavic steelworkers. Kennedy rode through the industrial neighborhoods, black and white, with Hatcher and Zale remaining at his side, bridging the painful chasm between the races in Gary. “It was hard to escape the meaning of that kind of symbol,” recalled speechwriter Jeff Greenfield.81

Journalist Jules Witcover wrote of the motorcade: “In the history of American political campaigning, certainly in primary elections, Kennedy’s final day in the Indiana campaign must be recorded among the most incredible.” He continued: “What set the motorcade apart, and what made it significant for Kennedy the candidate, was the unbroken display of adulation and support as he moved from Negro neighborhood to blue collar ethnic back to Negro again, over and over and over.”82 Robert Coles told Kennedy, “There is something going on here that has to do with real class politics.”83

On May 7, primary election day, journalists were struck by the remarkable coalition Kennedy seemed to have assembled. On the one hand, RFK did extremely well with black voters, winning 86 percent of their votes against McCarthy and Humphrey stand-in Roger Branigin.84 “What was surprising,” political analysts Rowland Evans and Robert Novak wrote, “was his record among the backlash ethnic voters that gave George Wallace his remarkable vote in Indiana four years ago….While Negro precincts were delivering around 90 per cent for Kennedy, he was running 2 to 1 ahead in some Polish precincts.”85

The vast majority of those who wrote about the campaign—journalists Jules Witcover, David Halberstam, David Broder, Theodore White, Jack Newfield, Joseph Kraft, Lewis Chester, Godfrey Hodgson, Bruce Page, as well as a number of historians—found strong evidence of Kennedy’s appeal among working-class whites as well as working-class blacks. But it is important to note that a small number of revisionists have suggested that Evans and Novak and all the other observers got it wrong, and that Kennedy did not perform particularly well among white ethnic voters after all.

Kennedy aides William vanden Heuvel and Milton Gwirtzman say that in industrial Lake County, Indiana, Kennedy lost 59 of 70 white precincts in Gary, and lost 13 of 14 white cities that Wallace carried outside of Gary.86 Citing vanden Heuvel and Gwirtzman’s work, respected historian Ronald Steel suggests that Kennedy “dream coalition” of working-class whites and blacks is the product of “wishful thinking, misperception, and spin control.”87 Another acclaimed writer, Gary Wills, reviewing Steel’s book in the New York Review of Books in 2000, concluded broadly: “The Poles had not come through for [Kennedy]. The coalition never existed.”88

But the weight of the evidence from primaries in Indiana and Nebraska, and from public opinion polling of Kennedy and Wallace supporters, suggests the revisionists are wrong to draw broad conclusions from a single jurisdiction. Although RFK’s appeal with whites was limited in Lake County, the revisionists miss the fact that statewide, RFK, the candidate most closely identified with black voters, performed astonishingly well among working-class whites and Catholics. Consider:

- An analysis of the Indiana results showed that RFK did well enough with working-class whites to win the seven largest Indiana counties where George Wallace ran strongest in 1964.89

- A May 1968 analysis in Indiana by pollster Stanley Greenberg found that RFK ran well among most European ethnic groups.90

- A May 1968 Harris poll found that statewide Kennedy beat McCarthy and Branigin by two-to-one among Catholics and industrial workers in Indiana. He did less well among affluent and educated whites, who were wary of his emphasis on law and order. Harris concluded that Kennedy’s victory “went a long way toward establishing his claim as perhaps the likeliest Democrat in 1968 who can deliver both the Negro and the lower-income white urban vote.”91

- Statewide, the New York Times noted, Kennedy was able to assemble “an unusual coalition of Negroes and lower income whites,” Kennedy did well “with blue-collar workers in the industrial areas and with rural whites.”92

Precinct returns in places such as South Bend, Indiana showed that RFK did well among black voters but also “piled up large pluralities in Polish-American precincts, where there had been some threat of a backlash vote,” according to political columnist Jack Colwell.93 While McCarthy won the Notre Dame University polling sites, Kennedy won in low-income Polish districts. In one heavily Polish precinct, RFK won 201 votes, as compared to 84 for Branigin and 78 for McCarthy. In another Polish precinct, Kennedy won 224 votes to 90 for McCarthy and 83 for Branigin. In the only precinct in St. Joseph’s County where Wallace had prevailed in 1964, Kennedy garnered 190 votes to 95 for McCarthy and 55 for Branigin.94 In Vigo County, which includes Terre Haute, Kennedy prevailed over Branigin and McCarthy, getting 9,600 votes to their respective 7,300 and 5,300 vote tallies. (Four years later, Wallace would defeat Humphrey and Edmund Muskie in the Democratic primary in Vigo County.)95

Even in industrial Lake County—one of two Indiana counties which had gone for Wallace in 1964—Kennedy was able to supplement his strong black support with enough working-class whites to enable him to beat McCarthy and Branigin by 47 percent of the vote to their 34 percent and 19 percent.96 For example, RFK carried East Chicago, which was two-thirds white, with 55 percent of the vote (to McCarthy’s 29 percent and Branigin’s 16 percent). Kennedy also won Whiting, which was all-white, by 47 percent of the vote to their 36 percent and 17 percent.97

Although Kennedy did lose many white precincts in Gary, as vanden Heuvel and Gwirtzman note, in a three-way-race, he still won 34 percent of the overall vote in white precincts—a remarkable accomplishment, notes author Thurston Clarke, in a city in which just one year earlier 95 percent of voters in white precincts voted for a white Republican over a black Democrat. Moreover, Clarke notes, many of the white precincts on Gary’s Southern perimeter where McCarthy prevailed were wealthier suburban neighborhoods of the type McCarthy typically won.98 (McCarthy trounced Kennedy, for example, in the white collar Glen Park section of Gary.)99 Meanwhile, in several areas, such as Gary’s thirteenth precinct, where Wallace had in 1964 defeated Johnson’s stand-in, Governor Matthew Welsh, by two-to-one, and Gary’s black mayor had lost, 439 votes to 84, in the November 1967 election, Kennedy defeated McCarthy and Branigin with 151 votes to their respective 86 and 51 vote tallies. Similar RFK victories were had in Gary’s eighth, tenth, twelfth, fourteenth, sixteenth, and eighteenth precincts, which had previously gone for Wallace and against Hatcher.100 One analysis found that Kennedy outpolled McCarthy by 14 percent and Branigin by 18 percent in Lake County’s Slavic precincts.101

Vanden Heuvel and Gwirtzman themselves acknowledge that “Of all the public figures in the nation,” RFK, in the years following his brother’s assassination, “spoke to lower-income whites from the sturdiest base of personal popularity.” They continued, “The respect for his name and his identification with law enforcement, gave him special standing among northern whites most vehement against the Negro.”102 Likewise, the skeptical historian Ronald Steel notes that among Irish and Polish voters in Indiana, Kennedy “ran ahead of McCarthy, whose non-ethnic, intellectual brand of Catholicism invoked no tribal loyalty.”103 Steel acknowledges that statewide, Kennedy got 48 percent of the industrial worker vote, beat McCarthy by 50 percent to 28 percent among Catholics, and came in last among the most affluent and best educated voters.104

Following Kennedy’s seven-week campaign in Indiana, he would run in four states in four weeks. When the presidential campaign turned to Nebraska’s May 14 primary, Kennedy was again victorious, relying on a similar coalition. Kennedy won with 51 percent of the vote to McCarthy’s 31 percent. The balance went to write-in votes for Humphrey (8 percent) and Johnson (6 percent). “Of equal significance,” wrote Jack Newfield, “was the fact that Kennedy’s delicate alliance of slum Negroes and low-income whites had worked again; Kennedy received more than 80 percent of all Negro votes and almost 60 percent of the votes cast in low-income white areas.”105 Despite recent rioting in Omaha, Kennedy was able to connect with working-class whites and swept all the counties with concentrations of Poles and Czechs.106

By contrast, when the campaign moved to Oregon, a more affluent white state, Kennedy would suffer his first defeat to McCarthy. Oregon was just 1 percent black and 10 percent Catholic, and had very few urban voters.107 It was the type of state where McCarthy felt comfortable telling an audience, “The polls seem to prove that he [Kennedy] is running ahead of me among the less intelligent and less well-educated voters of the country.”108 (An April 28 Gallup poll confirmed the correlation between education and support for McCarthy, though no research looked at “intelligence” levels.)109 On June 4, Kennedy won in South Dakota with a coalition of Native Americans and white low-income voters; and on the same day, Kennedy won California with strong vote totals from Latinos and African Americans and a sufficient number of white voters, including some upper-middle class liberals who were more prevalent in California than other primary states.110 Then, in the early morning of June 5, immediately after Kennedy gave his acceptance speech in Los Angeles, he was brutally assassinated. His short and exhilarating campaign that had united unlikely allies came to an abrupt end.

Although we will never know how Kennedy might have done at the Democratic convention or a possible general election campaign, scholars have been intrigued by a number of public opinion polls which found that Kennedy, while extremely popular among black and Latino voters, also had strong appeal with working class-whites who were sympathetic to George Wallace.111 While RFK was the most well-liked of twelve presidential candidates among black people, and Wallace the least popular, there was remarkable overlap in support from blue-collar whites.112 “I remember one of the first surveys I ever did was in 1968,” pollster Patrick Caddell remarked. “There were people in Jacksonville, Florida, telling me that they were for either George Wallace or Robert Kennedy.”113

Pollster Louis Harris suggested that if Kennedy had lived and gotten the Democratic nomination, “he probably would have heavily cut the Wallace vote among trade union members” in November 1968.114 Others point out that in most 1968 opinion-poll “trial heats,” Kennedy ran better against Wallace than any other Democrat.115 Theodore White noted that Wallace’s popularity, which had remained constant from the middle of 1967 to the summer of 1968, began to rise “within days after the assassination of Robert F. Kennedy.”116 A special cross-tabulation of polling data conducted by the Roper Institute also found that a majority of white voters who said they liked Wallace also said they liked Kennedy.117

Paul Cowan, a reporter who covered George Wallace for the Village Voice on a trip to Massachusetts in July 1968, noted that the Governor’s rallies and speeches—almost all in white working-class neighborhoods—were attended by many former Robert Kennedy supporters. “[T]he clear majority of Wallace’s audiences, day or night, are white working-class men,” Cowan wrote. “Many of them planned to vote for Robert Kennedy this year. ‘He wasn’t like the other politicians,’ said a television repairman from Framingham. ‘I had the feeling he really cared about people like us.’” In fact, Cowan noted, Wallace often praised RFK as “a great American” in speeches. “He was a patriot, unlike those professors on college campuses—pseudo-intellectuals, I call them—who say they long for a victory of the Viet Cong,” Wallace said at one rally. “You know,” a woman at a Wallace rally in Middleboro, Massachusetts told Cowan. “Wallace is very much like Kennedy.” Cowan concluded that Robert Kennedy was “the last liberal politician who could communicate with white working class America.”118 Reporter David Halberstam was stunned that Kennedy was deeply loved by black voters and also appeared to borderline backlash whites “who thought the choice in American politics narrowed to George Wallace or Bobby Kennedy.”119

After Kennedy’s death, working-class white and black voters both came to pay their respects to their candidate. An astounding 52 percent of black people in Harlem reported visiting Robert Kennedy’s casket at St. Patrick’s Cathedral, compared to 8 percent of whites on the Upper East Side.120 When Kennedy’s body was carried by train from New York to Arlington cemetery, biographer Chris Matthews notes, one saw: “young, old, black, white, men and women, few well-off, all caught up in their shared devastation.” These warring groups were, he writes, “massed along the tracks on that hot early summer day, holding American flags and saluting, waiting to see him pass.”121 Kennedy advisor Richard E. Neustadt recalls, “That train crawled on from noon to evening, and everywhere, the whole route, on both sides, there were those silent people waiting—it must have been for hours—watching, sometimes crying, black people, blue-collar people.”122 Harvard professor James Galbraith, a McCarthy supporter, thought the train was a fitting vehicle for RFK: “If you were burying Ronald Reagan, you would obviously want to do it with an airplane,” Galbraith said, “but if you are going to bury Robert Kennedy, his people live along the railway tracks.”123 For a campaign lasting eighty-five days, it appeared that these two frustrated groups of Americans had agreed on something—and they stood by the tracks to honor him.

Lessons for Today

Does Robert Kennedy’s 1968 campaign have any relevance fifty years later in the age of Donald Trump? On the one hand, observers trying to draw similarities need to be cautious:

- Robert Kennedy was a unique figure—the brother of a martyred president who had been in the public eye for more than a decade – and was running in a primary rather than a general election.

- He ran at a time when Roman Catholics were subject to greater prejudice than they are today, and when many such voters were more likely to identify as Polish American or Irish American than as white.

- In 1968, working-class whites (defined as those without a four-year college degree) were a much larger and more important segment of the voting population than they are today.

- Issues such as marriage equality, transgender rights, sexual harassment, immigration, and abortion, were not the hot-button items they are today.

- And, after 2016, many liberals understandably have little interest in wooing voters who went so heavily for an unabashedly bigoted candidate in Donald Trump.

But if the times are different, and the most salient issues have changed, powerful continuities remain. Moreover, in many ways, restoring the old working-class black, white and Latino coalition may be even more possible, more necessary, and more desirable for progressives than it was a half-century ago.124

The Progressive Coalition Is Possible, Necessary, and Desirable

1. The Coalition Is Possible

In the Trump era, when working-class whites and black and Hispanic Americans are deeply polarized as voting blocs, it may seem unthinkable that they could be brought together. But an effective progressive coalition does not require that all working-class whites come on board, only an important subset of voters who are not racist and can live with progressive positions on such issues as a woman’s right to choose and marriage equality. As Andrew Levison notes, “there are actually two fundamentally different kinds of white working class voters.”125 There are the persuadable working-class voters, and the always-Trumpers.126 Ideologically, pollster Guy Molyneux has found, about 15 percent of white-working class voters are reliably liberal about half are reliably conservative and, in between, about 35 percent (23 million voters) are moderate, persuadable white working-class people.127

Reaching these moderate white working-class voters does not require fundamental changes in race relations. As political analyst Jeff Greenfield and the late Jack Newfield have pointed out, “Blacks and almost-poor whites do not have to love, or even like, each other to forge an alliance of self-interest.”128 In some ways, multiracial class-based coalitions should be far more readily achievable today than in Kennedy’s era given three realities: declining racism, increasing income inequality, and the failure of conservatives to deliver for working-class whites.

Declining Racism

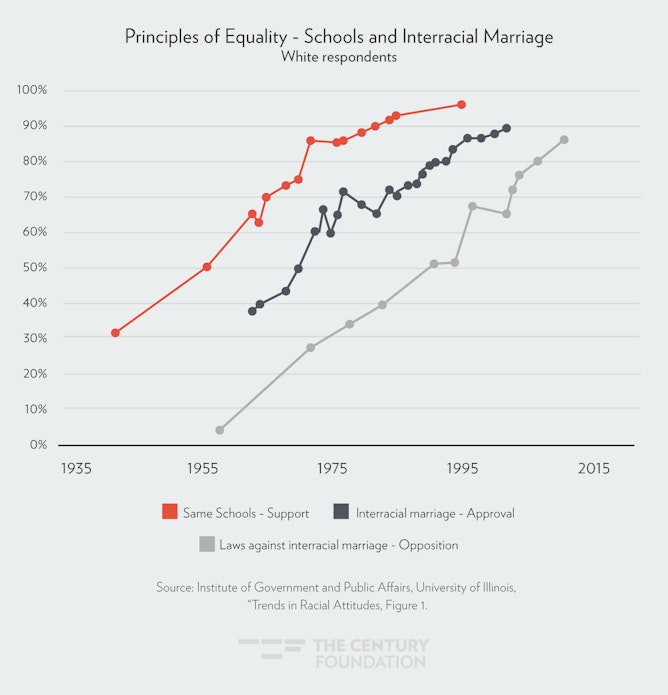

It may seem odd to say after the election of a race-baiting president in 2016, but RFK was running at a time when white racism was much more naked than it is today. In 1967, 27 percent of whites thought blacks and whites should go to separate schools, a figure that dropped to 4 percent by 1995, after which point the question stopped being asked. In 1967, about half (48 percent) of whites said they would not vote for a “generally well qualified” black candidate, a figure that declined to 5 percent by 1997. In 1968, a solid majority (56 percent) said there should be laws against intermarriage between blacks and whites, a figure that dropped to 10 percent by 2002. Fully 73 percent of whites in 1972 said they disapproved of interracial marriage; by 2011, the number had plummeted to 14 percent.129 (See Figure 2.)

Figure 2

While some might discount the veracity of what white people tell pollsters, actual interracial marriage rates have also increased by more than five times since RFK’s day—from 3 percent of marriages in 1967, to 17 percent in 2015, according to the Pew Research Center.130

To be sure, race relations took an enormous step backward recently with the election of Donald Trump. Through a series of actions and statements—denouncing a Mexican-American judge as inherently biased, saying there were “very fine people” who marched alongside neo-Nazis white supremacists in Charlottesville, suggesting immigrants should come from Norway rather than Africa—Trump has continually revealed himself as a racist.131 But just as it was wrong to assume after Barack Obama’s election that America had entered a “post-racial” era, it is wrong to say that the election of Trump signals that America has regressed to its earlier levels of racism. To the contrary, Trump’s racist comments and actions are unpopular among most of the American electorate. Indeed, his bigotry (coupled with his erratic and bullying behavior) help explain why, at a time of very low-unemployment, strong economic growth, and a booming stock market, Trump’s approval ratings are dismal. As political analyst Ruy Teixeira notes, “the underlying trend toward racial liberalism continues.”132

Increasing Economic Inequality

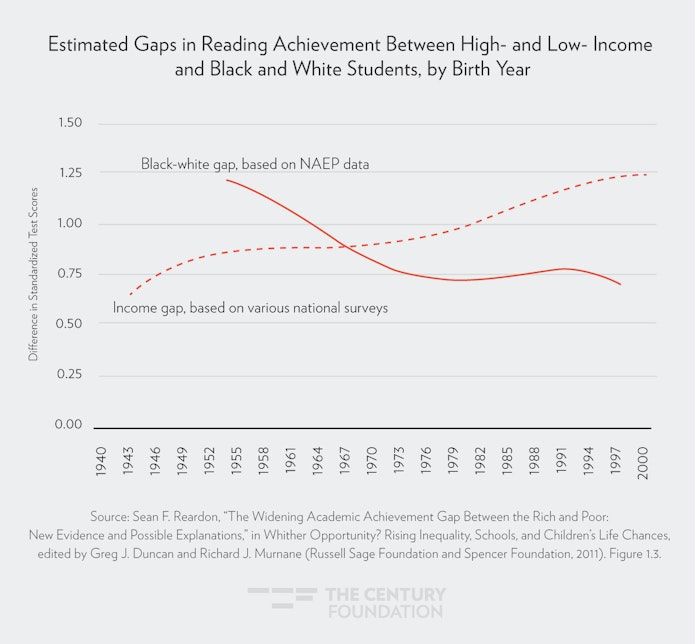

At the same time, economic inequality has increased dramatically since 1968, which, under the right set of political leaders, should serve to reinforce the urgency of building a class-based coalition of self- interest. In 1968, Kennedy argued that class was at the root of the nation’s problem more than color, and today that is far truer than it was then. To take one example, in a comprehensive analysis of the test score gap among groups of students, Stanford professor Sean Reardon examined nineteen nationally representative studies going back more than fifty years and found that, whereas the average gap in standardized test scores between black and white students used to be about twice as large as the gap between rich and poor students, today, the income gap (between those in the ninetieth percentile of income and the tenth percentile) is about twice as large as the gap in test scores between white and black students.133 (See Figure 3.) As Ben Jealous, the former NAACP chief and now a candidate for governor in Maryland, has argued, “The biggest gap in our society is not black and white but rich and poor.”134

Figure 3

The Gini coefficient, which measures income inequality, was at an all-time low in the United States in 1968.135 Since then, income inequality has skyrocketed.136 America’s three wealthiest individuals now have more in assets than the bottom half of the country.137 Working-class Americans of all races have been battered by globalization and technological change.138

Disadvantaged whites in particular are falling. Between 1990 and 2009, the proportion of children born to single mothers more than doubled among whites without a high school degree, from 21 percent to 51 percent.139 Angus Deaton and Anne Case of Princeton have noted a stunning decline in life expectancy, brought on by what are called “deaths of despair”—opioid addiction, alcoholism, and suicide.140 There is likely more disruption to come, as robots and driverless cars cause more dislocation among working-class people of all races.

It is fashionable to point out that economic anxiety can produce a rise in racial animosity among whites who are looking for scapegoats to blame and who cling to their racial identity as their only remaining signal of status. But under the right leadership, economic inequality can serve to highlight common interests, as Franklin Roosevelt demonstrated during the Great Depression.

Indeed, today, young people are increasingly open to democratic socialism, once a taboo affiliation in America.141 Polls show that 82 percent of Americans think that wealthy people have too much power in Washington, D.C. and the same proportion think economic inequality is a big problem. Today, 61 percent of Americans approve of labor unions, 60 percent believe “it is the federal government’s responsibility to make sure all American have healthcare coverage,” and 63 percent of registered voters favor making four-year public colleges tuition free.142 It is intriguing that key civil rights advocates, such as Rev. William Barber, the former head of the NAACP in North Carolina, thinks it is time to revive Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s Poor People’s Campaign to highlight the needs of economically disadvantaged Americans of all races.143

New Opportunities as Trump Forgets His “Forgotten Americans”

A year into Trump’s presidency, the opportunity seems especially ripe for progressives to appeal to white working-class votes, who were rightly identified by Trump as “forgotten Americans” and then promptly forgotten by Trump himself.

Trump’s initial appeal was that he ran against the traditional conservative elite’s focus on the wealthy; indeed, voters who had voted for Obama and then voted for Trump thought congressional Democrats were twice as likely to favor the rich as Trump.144 But as Trump’s actions line up increasingly with establishment conservative economic priorities, voters are becoming disenchanted. Polls show Americans believe the Trump tax bill not only favors the wealthy; they believe it will hurt them.145 Already, polls show, a majority of white working-class voters have turned against Trump.146 In counties that flipped from Obama to Trump in 2016, Bernie Sanders is much more likely to be viewed favorably (44 percent) as unfavorably (29 percent).147

2. The Coalition Is Necessary for Progressives

The white working-class is a much smaller portion of the American electorate than it was in 1968, so some argue that, to achieve progressive policies, it is more important to generate higher turnout among minority voters than to seek to include working-class whites in the coalition.148 Those advocates are wrong: progressives who seek to boost minority turnout (in part through economic populism) will probably not succeed without also appealing to the white working class, which remains “the largest race/education group in the country,” as Robert Griffin, John Halpin and Ruy Teixeira of the Center for American Progress note.149 A new analysis finds that non-college-educated white voters constituted 45 percent of voters in 2016, dwarfing the 29 percent of white voters with college educations.150 Their predominance in American politics helps explain why researcher Lee Drutman finds that the combination of economically liberal and socially conservative positions represents the sweet spot in American electoral politics: 73 percent of voters are economically liberal, while 52 percent are socially conservative.151

Fundamentally, the history of the past fifty years is that, when working-class white voters vote their race, conservatives win, and when enough vote their class, progressives do. Victorious candidates such as Bill Clinton won a plurality of white working-class voters in both 1992 and 1996.152 And Barack Obama did better among such voters in his successful campaigns than Hillary Clinton did in her losing effort. According to Ruy Teixeira, if Clinton had done as well as Obama with white working-class voters, she would have won the states of Michigan, Wisconsin, Pennsylvania, Iowa, Florida, and Ohio. By contrast, if Clinton has replicated Obama’s turnout among black voters, she still would have lost the 2016 election because the white working-class defections were so strong.153

Moreover, the white working-class constituency has outsized influence in congressional races because it is more evenly distributed throughout the country than any other group. Griffin, Halpin and Teixeira note: “while 43 percent of the age 25-or-older population in the United States is WWC [white working class], the median congressional district is just a little over 60 percent WWC.” They continue, “Only 26 percent of congressional districts have 25+ populations that are less than half WWC, a striking disparity given the nation’s overall composition.”154 Likewise, in U.S. Senate races, it will be impossible for progressives to win in states like Ohio unless they win some former Trump voters.

3. The Class-Based Progressive Coalition Is Desirable.

Finally, the progressive coalition of people of color and working-class whites is not only possible and necessary, it is desirable, if one’s goal is economic justice and social cohesion.

If one wants to address economic inequality head-on, a coalition of self-interest is far more potent than an alliance of minorities and educated whites who have different sets of priorities. That is why the great dream of labor and civil rights leader A. Philip Randolph was to create a cross-racial class-based coalition rather than a race-based cross-class coalition.155 In a class-based coalition, the fight for economic equality is front and center. As former Economic Policy Institute scholar Max Sawicky notes, Martin Luther King Jr. realized that allying with working-class whites “doesn’t neglect the black working class. It magnifies its political salience.”156

It’s also critical for progressives to ally working-class whites with African Americans and Latinos, because if they don’t, demagogues will, as we have seen, fill the vacuum and wreak havoc on American society. When working-class people feel alienated and are not given credible answers to their economic plight, they are vulnerable to appeal from hucksters who scapegoat religious, ethnic, and racial minorities. Failing to address legitimate anger about economic dislocation in a number of societies has allowed the rise of “white nationalism,” that, one observer noted, is “destroying the West.”157 Authoritarian regimes thrive on social division, and when it ensues, democratic norms are discarded. Minorities end up paying the biggest price of all.

How to get there?

If a class-based, multi-racial progressive coalition is possible, necessary and desirable, what kind of policies could progressives pursue to begin the effort to recreate the Kennedy coalition? The balance of this report outlines four ideas: (1) Stay committed to progressive principles of inclusion for marginalized groups; (2) consistently emphasize common class interests; (3) signal the inclusion of working-class whites by extending civil rights remedies to class inequality; and (4) respect the legitimate values of working-class people.

1. Stand up for Progressive Principles for Inclusion for Marginalized Communities

To appeal to a sizeable number of white working-class voters in 1968, Kennedy did not forfeit his basic principles or change his positions on civil rights, or war and peace. Throwing women, gay people, and people of color under the bus is both wrong and politically stupid if one’s aspiration is an inclusive populism that is multiracial and includes marginalized groups. Progressives need to boost funding for enforcement of anti-discrimination laws (including those that attack “disparate impact”), to stand for women’s rights, marriage equality, voting rights, gun safety, and a woman’s right to choose. Hillary Clinton was right when she said, in a debate with Bernie Sanders, “If we broke up the big banks tomorrow . . . would that end racism? Would that end sexism?” The advancement of civil rights is one of America’s great accomplishments of the second half of the twentieth century, and progressives must remain strong defenders in the twenty-first century.

2. Progressives Can Consistently Emphasize Common Class Interests

Coupled with a commitment to civil rights, progressives can fight for economic justice—more jobs and infrastructure, better health care, a more robust minimum wage, strong funding of public schools and the like. These types of commitments are central to the identity of progressives. But the liberal message could be sharpened in several ways.

Be consistent

Over the years, as progressives embraced free trade, globalization, and economic deregulation, they have increasingly been viewed as similar to conservatives.158 The Bernie Sanders insurgency pushed Hillary Clinton toward economic populism, but not as consistently as it could have. Polling evidence suggests that many working-class whites were torn over whom to support and did not break Trump’s way until the fall of 2016. Between August and November, Trump’s support among white non-college voters rose 23 points during a time when “the Clinton campaign stopped talking about economic change,” according to a report of the Democracy Corps and the Roosevelt Institute.159

Critically, talking more about economic issues not only helps progressives appeal to working-class whites, it also boosts minority turnout.160 An insufficiently populist campaign in 2016—coupled with the absence of Barack Obama on the ticket—may help explain why black turnout declined from four years earlier.161

Be Willing to Drain the Swamp

For many years, reforms to campaign financing and clean government initiatives were seen as upper-middle class concerns, but new research questions that idea. White working-class people are deeply cynical about the funding of campaigns by special interests, a fact that undermines progressives and conservatives alike.162 That’s why Trump’s (false) claim that he was self-funding his campaign and would “drain the swamp” in Washington D.C. had so much resonance.

Go after Wall Street on Taxes and the Fraud

In 1968, RFK’s populist campaign talked constantly about wealthy individuals who abused the system, and the candidate didn’t hesitate to name names. But in recent years, the progressive discussion of Wall Street abuse has been more cerebral. Substantively, progressives have been far tougher on Wall Street, championing the Dodd-Frank legislation that conservatives are now seeking to undo. But as Stanley Greenberg notes, white working-class voters surely noticed that during the Obama administration, “no executive was punished for criminal malfeasance” stemming from wrongdoing that triggered the Great Recession.163 It is hard to imagine RFK, a tough prosecutor, would have argued that some companies are “too big to jail.”164

Rethink trade policy

Progressives also need to do a better job of talking about the unbalanced impact of globalization. Trump made his opposition to the Obama administration’s Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) a central feature of his campaign on behalf of “forgotten Americans,” outflanking Hillary Clinton on the left.165 On a related point, Harold Meyerson notes, the economic recovery has been very uneven as large regions of the country have been left out. In the economic recovery of 2010-14, Meyerson says, half of new businesses were located in just twenty counties. Progressives are acutely familiar with economic underdevelopment in predominantly minority communities within metropolitan areas—as they should be—but Meyerson says they have failed to fully appreciate a second type of underdevelopment found in “non-metropolitan America, a land of decaying factories, abandoned mill towns, and depopulated farms.”166

Prioritize the right to organize unions

Fundamentally, political parties win when they enact policies to raise the living standards of citizens. Economic growth is the engine for that, but we have seen that growth by itself no longer guarantees wage increases. Progressives also need to find ways to increase worker power, which requires updating antiquated laws so that employees will have a genuine right to organize in the workplace. Unfortunately, labor law reform has not been prioritized, even when progressives have held the presidency and both houses of Congress—under Lyndon Johnson, Jimmy Carter, Bill Clinton, and Barack Obama.167 Strengthening labor will not only raise the wages of Americans but also strengthen the single most important force for educating working-class voters about the dangers of authoritarianism and racist ideologies. (See more details below on a proposal to strengthen labor unions.)

But even if progressives consistently talk about common class interests, they won’t break through with working-class whites unless they do two other things much better: (a) signal that they are concerned about working-class people of all colors; and (b) demonstrate that they will respect their legitimate values, not just their interests.

3. Signal Concerns by Extending Civil Rights Remedies to Class Inequality

After the 2016 election debacle, Matt Morrison, political director of Working America, spoke in a forum about the importance of “signaling” to voters. Donald Trump wasn’t going to do much, if anything, for coal miners, Morrison says, but it was nevertheless important that he talked about their plight and signaled that he cared about them.168

How could progressives signal in a meaningful way to white working-class voters that just as liberals properly care about the plight of struggling people of color, they also care about the struggles of working-class whites? To reunite “the Bobby Kennedy coalition,” Neera Tanden, president of the Center for American Progress, has talked about the need to “knit together a civil rights strategy with an economic strategy.”169 One powerful approach would be to literally extend tried-and-true civil rights remedies—which have made our country better in innumerable ways—to tackle the issues of class inequality that affect working-class people of all colors.

Below, I suggest that progressives do just that by backing four ideas in such areas as education, housing, and employment law: (1) an amendment to the Civil Rights Act to prohibit discrimination against workers engaged in labor organizing; (2) a Brown v. Board of Education-type policy to promote economic school integration of low-income pupils; (3) an Economic Fair Housing Act to combat discrimination against working-class people of all races; and (4) an affirmative action program in higher education for economically disadvantaged students of every color. These examples are by no means exhaustive; they focus on areas I’ve written about in the past and are merely illustrative of a larger theme. Elsewhere, I have explained why, on the merits, these four ideas constitute sound social policy that will promote greater social mobility and equality.170 But here, I emphasize the political framing value of extending civil rights remedies to combat economic inequality (without cutting back on the commitment of these policies to combat racial discrimination as well.)171 These new economic policies will disproportionately help people of color but will also be inclusive of working-class whites.

Labor Organizing as a Civil Right

Before the passage of the 1964 Civil Rights Act, open and flagrant employment discrimination against African Americans was common. While racial discrimination in employment remains a problem, Harvard political scientist Robert Putnam notes, “controlling for education, racial gaps in income are modest.”172

By contrast, class-based discrimination against workers trying to unionize has been on the rise, and average wage earners as a group are paying the price. In the 1950s, organized labor represented one-third of private sector workers and America enjoyed broadly shared prosperity, as workers were able to win a fair share of productivity gains.173 Over time, businesses began to openly discriminate against employees trying to organize a union, a practice that has essentially stopped labor organizing in its tracks. Although firing an employee for asserting his or her right to unionize is technically illegal under the National Labor Relations Act (NLRA), the penalties are so weak that firms routinely flout the law.174 Globalization has caused unions to suffer throughout the world, but the fall of organized labor in the United States has been much steeper than in other countries also subject to the forces of globalization. Routine employer discrimination against union organizing has caused Freedom House to rate the United States as far less free on labor rights than forty-one other countries.175

This is important because labor unions are essential to creating a middle class. Just as labor unions have declined, so has the proportion of income going to the American middle-class. (See Figure 4).

Figure 4

The Civil Rights Act of 1964 (updated in 1991) outlawed racial discrimination in the workplace and in other facets of life, and helped delegitimize racial prejudice. The act needs to be vigorously enforced to address ongoing racial discrimination.176 But as Moshe Z. Marvit and I explain in our 2012 book, Why Labor Organizing Should Be a Civil Right, Congress should also amend the Civil Rights Act to extend protections against discrimination based on race, sex, religion, and the like to include individuals trying to organize a union. Doing so would give employees a much more powerful tool to combat discrimination than are available under the National Labor Relations Act. Whereas the NLRA gives employees wrongfully terminated the right to back pay and reinstatement, the Civil Rights Act gives employees the right to sue in federal court, engage in legal discovery, and win compensatory and punitive damages and attorneys’ fees. Representatives Keith Ellison and John Lewis have introduced this type of legislation in Congress and progressives need to prioritize this idea at the federal, state, and local levels.177 Along the same lines, Representative Bobby Scott and Senator Patty Murray have proposed the WAGE Act (Workplace Action for a Growing Economy), which would give employees the right to sue if they are fired for trying to start a union at work.178

Socioeconomic School Integration

Racial integration of schools was—and is—an important objective to provide social mobility for students of color and social cohesion for the country. But today, a growing number of school districts are also focused on integration by socioeconomic status, bringing students from different economic classes together, whatever their racial backgrounds.179 As I explain in my book, All Together Now: Creating Middle-Class Schools through Public School Choice, the framing of integration primarily in terms of socioeconomic status offers legal advantages (because the Supreme Court disfavors the use of race in assigning students to schools) and it is backed by research (which suggests that the socioeconomic status of classmates has a bigger impact on achievement than the race of peers.) But there is also an important signaling advantage to the economic approach: it acknowledges that disadvantages whites, too, suffer from socioeconomic segregation.

Racial integration, by itself, doesn’t guarantee equal opportunity. In Louisville, Kentucky, for example, a racial desegregation plan produced a school—Roosevelt Perry Elementary—that was half black, half white, and virtually all poor, and that school struggled mightily. When the school superintendent said he wanted to take steps to integrate by socioeconomic status as well as race, the principal, J. Back, told the local paper that it made him feel “like leaping from his chair and cheering” because that was what was needed for kids.180

Likewise, when Boston schools were desegregated in the 1970s, wealthy whites fled to the suburbs, leaving working-class white and black students in schools with concentrated poverty that failed to provide equal opportunity. Harvard psychiatrist Robert Coles saw the deep unfairness of the situation. “I think the busing is a scandal,” Coles told the Boston Globe. “I don’t think it should be imposed like this on working-class people exclusively. It should cross these lines and people in the suburbs should share in it.” Working-class whites and blacks, he said, have “gotten a raw deal. . . . Both groups have been ignored. Both of them are looked down upon by the well-to-do white people.”181

A focus on socioeconomic integration, ideally crossing school district lines, recognizes that working-class whites and blacks have a common interest in attending school with, and having the same opportunities as, wealthier students. J. Anthony Lukas, in his Pulitzer-prize winning account of the Boston school desegregation crisis, Common Ground, noted that the Boston working-class white and black families he profiled had far more in common with each other than either did with wealthier whites in the suburbs. “What kind of alliance could be cobbled together from people who feel equally excluded by class, or by some combination of class and race?” he asked.182 A focus on socioeconomic integration makes clear the shared common ground of these groups.

Today, one hundred school districts and charter schools, educating some four million students, make conscious efforts to integrate schools by socioeconomic status.183 Unlike compulsory busing programs from the 1970s, these programs tend to rely on voluntary school choice programs and incentives such as special magnet school themes to achieve integration. Districts pursuing socioeconomic integration range from mid-size towns (such as La Crosse, Wisconsin) to major urban areas (such as Chicago, which integrates a subset of its schools) and range from the South (Raleigh and Louisville) to the North (Cambridge, Massachusetts and Champaign, Illinois). Using public school choice to give working-class students of all races access to better schools is good social policy and also serves to remind the Bobby Kennedy constituencies of their common interests.

An Economic Fair Housing Act