Pre-reading note regarding terminology: person-first language was the preferred method to refer to people with disabilities for many years, including at the time of the passage of the Americans With Disabilities Act in 1990. However, more recently, some members of the disability community have made the case that being a disabled person can be a cornerstone of a person’s proud identity and choose to be referred to in that manner. This report recognizes both views, so person-first and disability-first language are both used.

Today, jobs, the labor market, and the economy all work differently than they did in 1935, the year the Social Security Act was enacted. The nearly ninety-year-old federal law provided for the first time a national commitment to the economic welfare of people in need, including a modicum of income support to jobless workers under the federal/state unemployment insurance (UI) program. Since then, other monumental laws have brought the country toward greater fairness and opportunity, including the Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA), the Civil Rights Act, the Equal Employment Opportunity Act (EEOA), the Rehabilitation Act of 1973, and—key to this report—the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA). But during this near-century of progress, unemployment insurance has sadly not been significantly updated to reflect our societal growth, with the exception of federal amendments in the 1970s requiring some additional state coverage to more domestic and farm workers.

One segment of the population that the unemployment insurance program is inadequately serving is people with disabilities. The unemployment rate is typically higher for working people with disabilities, and they typically experience longer bouts of joblessness during economic downturns—and yet, they also experience greater difficulties accessing and maintaining UI benefits while looking for new work. So, while this segment of the population is among those who would most benefit from a robust, functioning UI system, they are also currently among the worst served by the program. Furthermore, fixing UI for disabled workers would also wind up making the system work better for everyone.

For UI to meet the needs of all workers—disabled and nondisabled alike—in 2024 and beyond, significant improvements are needed both administratively and legally. People who lose work through no fault of their own need serious, comprehensive UI reform and better administration of this federal/state partnership in order to ensure fair access to earned benefits.

This report will describe the challenges that people with disabilities face in accessing benefits, and what we can do to improve the process. Access to earned benefits is essential for people with disabilities for a variety of reasons—not only because it is fair, but also because workers with disabilities have been left behind in too many ways and UI access is one avenue toward leveling the playing field.

This report will offer short- and long-term considerations for anyone working in the unemployment ecosystem, whether they are federal or state policymakers, state workforce agencies, or as advocates for claimants. The report will begin by briefly describing the challenge that disabled workers face in accessing UI and the benefits of reforming the system to better serve these workers. The report will then present a list of considerations for UI reform in the areas of administrative process and technology improvements as well as considerations for policy change.

A majority of the administrative and policy considerations suggested here would also help unemployed workers outside of the disability community in the same way that many disability accommodations do—such as when a parent pushing a child in a stroller or a person using a wheeled cart to bring groceries home benefits from curbcuts.1

The simple fact is, improving disability access would improve human access. Right now, UI technology is all too often inaccessible, administrative philosophy is not conducive to approval of benefits for people with disabilities, underlying state law is often punitive to everyone but especially harsh for disabled claimants, and accessibility is often just not prioritized given the competing priorities for still overburdened state systems.

The bottom line is that disability access to UI is everyone’s concern, because UI needs to serve everyone equally if it is going to ensure that UI continues to serve as a countercyclical stabilizer and prevent wage erosion.

The bottom line is that disability access to UI is everyone’s concern, because UI needs to serve everyone equally if it is going to ensure that UI continues to serve as a countercyclical stabilizer and prevent wage erosion. As the late Senator Paul Wellstone used to say, “we all do better when we all do better.”

The Challenge

People with disabilities report struggling to navigate public benefit systems2 that were explicitly designed to provide them with supports. These challenges are on top of already having to spend too much time navigating arduous systems to accommodate a variety of needs,3 from accessing health care to getting public benefits. In addition, some kinds of disabilities actually make it more difficult to engage with a lengthy application process.4 Given that the UI system was not originally intended to cover all people with disabilities, the challenge of making UI work for everyone is enormous. Combine these challenges with the fact that the UI application process is notoriously difficult regardless of an applicant’s ability,5 and this creates a compounding problem when there is an economic crisis and UI needs to serve a whole community under duress.

Making sure that people with disabilities have access to unemployment benefits is part of a larger need to begin to build and secure economic justice for this community. In December 2023, in a strong economy with historically low unemployment overall, the unemployment rate for people with disabilities was 6.7 percent, which was still more than twice the rate that it was for people without disabilities, 3.4 percent for people ages 16–64. This higher rate of unemployment can compound with other factors, such as race, ethnicity, and gender. For example, the unemployment rate for people who are Black and have a disability was 12.4 percent, and for those classified by the U.S. Department of Labor as Hispanic, it was 10.1 percent.6

An important thing to remember is that the unemployment rate only takes into account people who are considered to be participating in the workforce. People who want to work but have long since given up seeking employment due to the myriad obstacles of dealing with a broader, often ableist job market are not included in these numbers. While it is the case that people with disabilities might be unable to work and should be well supported by a robust safety net through the Social Security system, it is also true that everyone who wants to work should not only be able to find worthwhile employment but also should have access to quality reemployment services. The Office of Disability Employment Policy at the Department of Labor maintains up-to-date information7 on disability employment and unemployment.

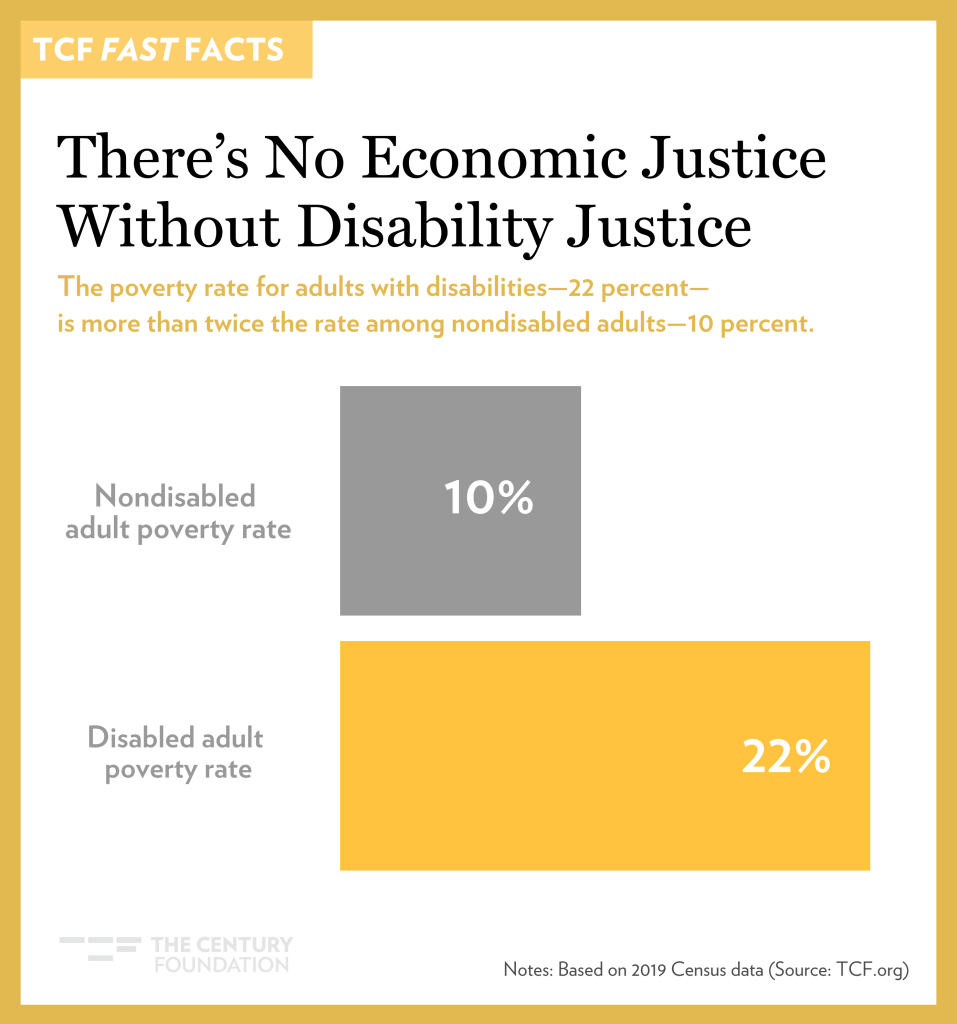

Figure 1

One particular requirement in UI that is uniquely challenging for people with disabilities is the requirement in Social Security Act Section 303(a) that states that “as a condition of eligibility for regular compensation for any week, a claimant must be able to work, available to work, and actively seeking work.” The shorthand for this is “able and available.” This can make UI particularly unfriendly to people with disabilities from the moment a claimant starts an initial application all the way through to an agency’s ultimate adjudication in administrative inaccessibility and in laws and administrative rules about who qualifies and how.

The experience of disability is incredibly complex, as disabilities vary as widely as the human experience does. Two people with the same disability may need different accommodations, both in the workplace and when applying for UI. For example, while having an American Sign Language (ASL) interpreter may be better for a person who is Deaf or hard of hearing, someone else may not know ASL and prefer closed captioning. Therefore, one of the most important considerations is the understanding that there are no one-size-fits-all solutions that will make systems more accessible—these are process improvements that will require continuing evolution as administrators learn more.

The Benefits of UI Reform—for Disabled Workers and for Program Effectiveness

It is always important to go back to the several goals of the UI system when considering how to strengthen it to accomplish those goals more effectively. The most obvious goal is to ensure that the loss of a job does not immediately cause economic catastrophe for individuals. More than half of Americans live paycheck to paycheck,8 and one of the main factors in barely getting by are chronic health conditions or caregiving,9 so an immediate replacement of lost income is a necessity for most people but even more so for people with disabilities. That is why, for example, Title III of the Social Security Act requires benefits to be paid “when due.” The issue of what constitutes “when due” rose to the level of a U.S. Supreme Court decision in 1971 and subsequent guidance10 confirmed that means eligibility determinations should be made within two to three weeks.

Another key feature of unemployment is that it is designed to keep people attached to the workforce. When a claimant files for UI, they also must register with the Employment Service,11 which provides claimants with reemployment assistance and can connect claimants with a variety of job training opportunities. In addition, most states can provide claimants services through their Reemployment Services and Eligibility Assessment12 (RESEA) grants. These services have been proven to help people get back to work faster and land higher-paying jobs that are a better match for both workers and employers. Given the unacceptable rate of involuntary unemployment in the disability community, access to these services is especially critical.

Unemployment Insurance is also meant to provide a community-wide benefit in broad economic downturns. During the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, every dollar spent in unemployment benefits generated $1.92 in the economy, according to the International Monetary Fund (IMF).13 Enhanced unemployment benefits strengthened and speeded up the nation’s economic recovery. Yet unemployment benefits cannot support workers or the economy if they are not accessible. A cornerstone of the disability movement is the right for people with disabilities to participate in society fully. Folks who have disabilities are in every community, but in order for them to fully participate and not be uniquely disadvantaged in economic downturns, UI needs to be accessible in order for the benefit to do what it is supposed to on a macroeconomic level. During the robust economic recovery since the start of the pandemic, labor force participation for people with disabilities has increased from 20 percent to 25 percent, which makes this an even more important issue. Communities with high unemployment rates tend to be “last in and first out” in the economy, which means that during widespread economic crises, they tend to be the first to see job loss and the last to find suitable reemployment.14

Enhanced unemployment benefits strengthened and speeded up the nation’s economic recovery. Yet unemployment benefits cannot support workers or the economy if they are not accessible.

Finally, unemployment insurance is meant to provide workers who lose jobs with a “reservation wage,” or enough wages to allow workers to find a suitable replacement for their old job. This helps to prevent downward pressure on lifetime earnings potential that would otherwise occur if workers felt pressure to take the first job they can find, rather than one that is a better fit. Labor market policies that encourage the most appropriate job matching are not only good for workers, but employers as well, as employers benefit from being able to find the right people for the job.15 The need to maintain a reservation wage during spells of unemployment is also more important for people with disabilities as there are a number of reasons for the interconnectedness between disability and lack of wealth.16 People who experience disability are less likely to have accumulated wealth. Accommodating disabilities or paying for chronic health challenges is expensive, and employment discrimination against people with disabilities17 is still far too prevalent, which means that a job search is likely to take more time with less accumulated wealth to stay afloat. Many people with disabilities who have recently moved from Supplemental Security Income (SSI) to work are also likely to have accumulated little wealth as SSI has an extremely limited asset limit of just $2,000 for one person or $3,000 for a couple.18

Process Improvements

While the bulk of what needs to be done to make unemployment insurance fair to people with disabilities will require administrative changes and coordination at the federal and state levels, there are program-level improvements in processes and technology that can be made to effect immediate change in the near future and make systems easier for people with disabilities to use. This report addresses process improvements ahead of technology because while there already has been a great deal of focus on technology, process improvement has been somewhat overlooked.

Ensure Live, In-person Access/Interaction

One of the most important process improvements that states can do is provide meaningful in-person and live phone access for unemployment claimants. While federal guidance19 requires that states have multiple ways to access benefits, in five states surveyed in 2023, 100 percent of respondents indicated that they only filed online.20

States must adhere to many longstanding laws,21 including the Rehabilitation Act of 1973, the Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990, amendments to the Workforce Innovation and Opportunities Act (WIOA) of 2014—particularly the equal access amendments adopted in 2016—and the Civil Rights Act. Recent guidance from the U.S. Department of Labor22 is helpful in laying out both what is legally required of states as well as what other best practices are. This guidance also emphasizes that equal access is an ongoing improvement process that involves give and take from the affected communities. This guidance also reiterates past guidance that requires state agencies to have multiple methods of interaction with the state UI agency. While technology is sometimes incredibly helpful, there are instances where phone or in-person options are going to be necessary to make sure everyone can get the public benefits they have earned.

Robust Plain Language and User Testing

Overly bureaucratic and inaccessible language on UI websites helps no one. Not only does unfamiliar language on a form discourage people from accessing a benefit that they have earned, but when claimants accidentally answer questions incorrectly, this also creates administrative burden for the agency throughout the fact-finding process. This is especially true for people with disabilities who may be accessing the site through a screen reader or have language processing difficulties or intellectual disabilities. Fortunately, many states are recognizing this problem and using available resources, including federal funding, to make sites more accessible. There are several examples in a recently published paper by this publication’s author23 through the Heldrich Center for Workforce Development at Rutgers University about how New Jersey transformed confusing and poorly designed forms into forms and language that are much easier to navigate and understand.

The U.S. Department of Labor has an excellent plain language portfolio on their website.24 It includes sample forms, glossaries, and process suggestions for developing accessible forms. Likewise, the National Association of State Workforce Agencies (NASWA) has an excellent behavioral insights toolkit25 that can help states think about form design and language that improves the likelihood that claimants will move through forms smoothly and answer questions correctly. This again demonstrates an area where simplifying things for claimants can also help agencies pay benefits to the right people on time more simply.

There are different ways to go about planning a plain language conversion. Some states identify the most-used forms to improve, while others choose to start with forms that claimants access earliest in the process, setting a standard for a claimant-friendly gateway as a priority. However, the most effective way to embark on a plain language project is usually to do a comprehensive examination of all forms, map the customer journey, and determine whether forms can be consolidated. Form consolidation can save agencies millions of dollars while at the same time reducing claimant burden. If possible, analyzing which forms and questions produce the most confusion and erroneous response and the greatest time burden associated with reading and responding to claimant communications can help to identify where changes are needed to ensure that claimants can accurately complete forms in a timely manner.

Once the overall form review process is complete, then states can begin the process of rewriting for legibility/understandability. Ideally, this would take place at the same time as modernizing the technology interface (which will be covered in the technology section). While the plain language process should obviously get underway before translation for limited English proficiency (LEP) claimants begins, it can be helpful for some overlap to exist. For example, in New Jersey, the translation team at U.S. Digital Response found that pictures of forms helped some claimants better understand what was being asked of them, which was also useful also to the plain English language efforts. It is important to remember when adding pictures to be sure that text descriptions are still available for people using screen readers.

It is important for state agencies to bring in claimants and advocates early and often in this process. User testing may be thought of as something that should occur at the end of the process to test for whether a product is accepted. However, this process should happen early, often, and be iterative. That means developing a form in house that meets all of the program and legal requirements but with an initial attempt at improved legibility. Then the revised form must be tested with a manageable number of users by demographic, their feedback incorporated, and then tested with another group of users and tested for not just acceptance of the language but testing to make sure the user understands what is being asked of them and why.

User testing may be thought of as something that should occur at the end of the process to test for whether a product is accepted. However, this process should happen early, often, and be iterative.

Working with advocacy organizations at this point in the process can be extremely helpful in ensuring participation from potential users that are least likely to participate otherwise. Many potential users who need to be better able to work with UI forms may be less likely to respond to a request for feedback from an agency, but would respond to an organization that they rely on because people in marginalized communities may be better able to trust familiar organizations than governmental entities. This is especially true within the disability community because these experts will be able to identify a range of users to try to accurately represent the range of disability experience that should be taken into account. While some improvements might help many kinds of users, everyone’s experience is different and people who have been immersed in disability issues for years are going to be far more likely to help identify both issues and kinds of disability that must be taken into account.

Improved Language, Outreach, and Personnel

Disability advocates consulted during research for this report repeatedly emphasized that the language used in the Social Security Act’s requirement that UI claimants be “able and available” for work made disabled claimants feel as if the program was not meant for them. Therefore, outreach efforts directly and specifically focused on various disability communities is critical. Fixing forms and interface is important going forward, but people with a past experience of looking into UI and finding an unfriendly process will be reluctant to try applying again. States should consider partnering with disability community groups that have a deep understanding of disability issues as well as hiring in-house disability experts as part of a team that will ensure universal access. States are increasingly also adding in-house claimant advocates to their program, and it would be a good idea to ensure that some of these personnel are disability experts. In addition, all agency staff should be trained on disability access and inclusion and how best to assist people with any kind of disability.

One of the most helpful things states can do is to find out if a claimant is in a place to accept a suitable job without using the term “able.”

Short of eliminating the term “able” from the Social Security Act’s UI eligibility requirements, one of the most helpful things states can do is to find out if a claimant is in a place to accept a suitable job without using the term “able.” For example, rather than asking claimants whether they are “able and available” to start work—a question that can be murky to many people, not just those with disabilities—New Jersey’s heavily user-vetted question on their continued claim form now just asks claimants if they can start work immediately.26 A recurring issue for state agencies is the entrenched belief that they need to communicate with claimants using the exact wording of state or federal laws, which can be difficult for laypeople to understand. When engaging in plain language efforts, it is worth attempting the most accessible language and then submit it for review with UI legal experts to ensure that it is compliant.

Better Medical Issue Flagging

A key element of determining UI eligibility is determining whether the claimant separated from their job for qualifying reasons, which involves finding out why a claimant was laid off or quit. Claimants can qualify for UI for a variety of quits and terminations. In some states, all claims are flagged for “able and available” review any time a claimant indicates a medical cause for a quit. There are some circumstances that are common in which a claimant may quit a job that has caused an illness or injury, or where a claimant’s illness or injury only disqualifies them for a very specific job but the claimant can still work. It should be possible to develop a more sophisticated decision tree that can create a “happy path” for certain kinds of medical cause quits. This was a major issue during the pandemic when several medical cause quits were specifically allowable for people who were diagnosed with COVID-19 or in a household with someone who has been diagnosed, were caring for someone with COVID-19, or simply because of the Pandemic Unemployment Assistance (PUA) approved circumstance that “the individual has had to quit his or her job as a direct result of COVID-19.”27 There are several instances outlined in the policy section of this paper that could surpass automatic flagging.

Improved Data and Department of Labor Enforcement Authority

The Department of Labor has repeatedly28 issued guidance29 clarifying for states what their obligations30 are in ensuring access to systems for people with disabilities. It has also issued guidance that states must collect demographic information and act on any findings of disparate impact.31 The challenge that is particularly daunting for measuring disability access is that the reporting is voluntary, and many claimants are extremely reluctant to report their disability status on a form emphasizing that claimants must be “able and available” for work, because they fear judgement about their disability status affecting their determination of eligibility. Representative Steven Horsford (D-NV) introduced legislation32 in Congress that among other things would improve collection of demographic data and would improve the Department of Labor’s authority to enforce administrative performance. Right now, the Department of Labor has an all-or-nothing ability to enforce state noncompliance with federal UI administrative guidelines. If a state is found substantially out of compliance and is not making an effort to fix performance issues that the Department of Labor finds, all it can do is revoke the state’s entire administrative grant to operate the entire UI program. This legislation would allow the Department of Labor to withhold up to 15 percent of a state’s administrative grant when it is not meeting goals, including accessibility goals, and direct the state to use the funding to fix those issues. Coming up with ways to improve reporting is going to be challenging given the likely under-reporting of disability status due to the reluctance to report it outlined above, but now is the time for groups to consider what might work to help ensure that states have actionable data and the Department of Labor has the legal authority to effectively enforce accessibility.

Technology Improvements

In the not too distant past, UI claims were all filed in-person at a local UI office. A claimant would arrive at the office carrying physical documents demonstrating their employment and loss of work. A claims examiner would ask the claimant something along the lines of “tell me what happened on the last day that you worked?” While the move to online and call-in options have been critically important to many people in the disability community, and in-person interactions were not uniformly pleasant, it would also be a tremendous improvement if those options could carry some of the warmth and humanity that can happen in face-to-face interactions. Many of these technology suggestions were included in an earlier report by The Century Foundation,33 but this section of this report will discuss why these issues are particularly important to people with disabilities.

The most critical issue for states is making sure that they are following all relevant guidelines (see Appendix 1). The key takeaway here is that there are a variety of resources available to help states ensure they are meeting and exceeding core federal requirements to ensure disability access—states should take advantage of those resources.

Talk to the Community First and Always

While this was covered in the general administration section, it bears repeating when looking at technology upgrades. A core mantra in the disability community is “nothing about us without us.” Many of the guidelines above were developed through extensive outreach and research with disabled users, so relying on the guidelines will put people on the right path for improving the system. Unemployment insurance, however, is exquisitely complicated. So many factors go into rules around eligibility and how individuals’ unique experiences fit into those rules, and then how systems can be built to account for those unique experiences that it will never be possible to distill all of these lessons in one rulebook or style guide. That is why developing a good relationship with advocates and claimants with disabilities is key. Questions come up in program administration on a regular basis that will require the involvement of the end users and their representatives. Making sure the disability community is in an internal outreach list is not going to be enough on the technical development side of things. Rather, planned check-ins with this community will be essential from before the first line of code is written through the foreseeable future as technology improvements are continually ongoing. To the extent that there is any kind of UI advisory board, people who can represent the disability community well should be seated at that table.

To the extent that there is any kind of UI advisory board, people who can represent the disability community well should be seated at that table.

Robust User Experience Testing

While this applies to disability access in particularly important ways, more broadly, user experience (UX) considerations should be incorporated into technology development from the beginning of the process and throughout product development. Sometimes, UX testing is only done at the end of the process to ascertain user acceptance. However, to truly develop a system that works well for everyone, input from users from the beginning of the process helps states build better decision trees and forms that can ensure not just a better user experience but also more accurate and streamlined decision making. User testing, just as plain language testing, should be iterative and include people from a wide variety of backgrounds. This includes not just testing on claimants with disabilities, but making sure that a diverse spectrum of disabilities are represented in testing and that includes people from a range of racial, ethnic, gender, and socio-economic backgrounds. Finally, users willing to help out by participating in testing should be compensated for their participation.

No Timing Out/Ample Visual and Audio Warning before Timing Applicants Out

This is a difficult issue for anyone, as applicants often do not know what information they will be asked to provide, which means if they need to look through computer files or paper records for information, claimants can get timed out and have to sign in again. Sometimes when this happens, their progress is not even saved. This can be an extra hurdle for all kinds of people, including those with mobility issues that prevent them from getting from their computer to a paper file quickly, people navigating with screen readers, people with issues such as tremors that might make entering information difficult, and people who need extra time processing information. If it is a critical security issue to maintain some kind of timeout, then the technology should at least incorporate auto-save before a timeout occurs. Another solution to help prevent these kinds of issues is to prominently display at the start of the process all documents that claimants will need to complete their application.

Easy Password Reset

Currently, some states have a password recovery system that requires claimants to call in and then a code will be physically mailed to them to reset their passwords. During the pandemic, this made password reset nearly impossible in some places, as the pandemic shutdown meant many phone lines were inaccessible to UI workers and calls went unanswered after multiple hours of attempting to get through. In some states, claimants who were not Deaf or hard of hearing found and used the “telecommunications device for the deaf” (TDD) numbers, compounding the difficulty of calling in for people who need that service. This is comparable to the timing out issue for people with movement disorders or other disabilities that might make it difficult to accurately type in a password. Banks and other highly secure applications have simpler password reset protocols that should be replicated by states.

Allow Claimants to Navigate to Earlier Screens

Some application processes do not allow claimants to return to submitted screens once the application has advanced. Again, due to the complexity of the situation that various people with disabilities might have to take into consideration, it is fairly easy to misinterpret a question and realize later in the form that they had answered a previous question incorrectly. Often, states set up the application process so that the answer to one question can send a claimant down different paths of further inquiry (often referred to as “decision trees”) that might help a claimant realize they misunderstood the question. Having the ability to back up and change an answer would save claimants and agencies alike work and stress.

Explanations in Pop-Up Text of What Terms Mean and Why a Question Is Being Asked

In order to help prevent misunderstandings that lead to claimants providing the wrong answer to a question, in addition to a comprehensive plain language review, there should be a mechanism to explain or define terms of art that cannot be avoided under current law that might be confusing to claimants. This is perhaps one of the most important things for people with disabilities, due to “able and available” issues cropping up throughout the process. If that terminology cannot be avoided, it should at least be made clear that, for UI program purposes, it is about whether a claimant is in a position to accept suitable work immediately, not whether they have a disability. Even if terminology does not seem confusing or the reason for asking the question seems obvious to seasoned agency staff, it might not be as obvious to an applicant, so erring on the side of explaining more rather than less is helpful.

Optimize for Mobile

Making sure technology works on mobile devices is important for many users as in some states, the majority of applicants apply via phones or tablets. This is especially critical for people with disabilities, and even more so for those in rural areas who lack broadband access. As is reiterated throughout this paper, people with disabilities are not a monolith, and maximizing the number of pathways is the best way to ensure that you are building a path around hurdles. For example, some people with visual disabilities find some screen reading technology on desktop platforms to be much less useful for them than the access technology that comes with mobile devices.

Making sure technology works on mobile devices is important for many users as in some states, the majority of applicants apply via phones or tablets.

24/7 Operation

While round-the-clock operation has been a recommendation since before the pandemic, the COVID-19 era has shown that it is just a better practice to spread out the hours a site is available to prevent surges from crashing them. While it is important for certain processes to have technology off-ramps to accommodate a variety of situations in which technology is the more difficult option, the reality is that online access is a tremendous help to people with a wide range of disabilities. Finding ways to spread out traffic to an online form can help prevent the website crashes that typically happen during economic crises.

Tracking Administrative Microdata

Sometimes technology can track which questions take the most time to answer or where claimants tend to time out or go back or make mistakes. Collecting these data on the application and weekly certification process can help to identify specific questions that cause applicants to drop out of applying or take an excessive amount of time.

Finally, when it comes to administrative process simplification—as with other ways in which accommodations for people with disabilities make things generally more useable for everyone—improving access to UI for people with disabilities makes the system easier for everyone to use. Anyone finding themselves in the unenviable position of having to apply for UI is already having one of the worst days of their lives, which should never be compounded by an overly bureaucratic system. Therefore, improving access for people with disabilities improves overall program efficiency.

Anyone finding themselves in the unenviable position of having to apply for UI is already having one of the worst days of their lives, which should never be compounded by an overly bureaucratic system.

Necessary Policy Changes

While the administrative and technical changes are the most readily accomplishable in the near term, fundamentally, many aspects of UI policy need to change in order to assure true access for people with disabilities.

Able and Available

To UI experts, one of the defining characteristics of the program is the requirement that claimants be able for work, available for work, and actively seeking employment. The point is to make sure that people who are collecting unemployment benefits remain attached to the workforce by seeking work and accepting suitable work.34 This is the point where one might expect discussion that the Social Security Act was written way back in 1935 and as such, might have some antiquated language that needs updating. While the concept of “able and available” had long been a concept states have used since the beginning of the program and codified in guidance in 2007, specific language in Title III of the Social Security Act wasn’t added until 2012 as a provision of the Middle Class Tax Relief Act (MCTRA) some twenty-two years after the passage is of the ADA, which is astonishing.

Admittedly, it is important to establish that workers are doing what they reasonably can to find work and that they can make themselves available when suitable work is offered. That is truly an important feature of the UI system. Without creating a connection to work, the system becomes less defensible and of less ultimate value to workers and employers. There are ways to talk about this availability for work in ways that are less likely to intimidate claimants with disabilities and empower states to enact policies that are unfair to people with disabilities. Ultimately, the relatively newly added term “able” should be removed from Title III of the Social Security Act and replaced with language that more precisely demonstrates that individuals should be willing and ready to accept work and engage in meaningful activity to find a suitable replacement for their prior employment.

Juris Doctor Rachael Kohl, currently at Wayne State University Law School, published an extensive examination35 of how much current thinking around “able and available” excludes workers with disabilities who should qualify for UI when she was the director of the Workers Rights Clinic at the University of Michigan, which should be fundamental reading for anyone interested in this issue. In that paper, she makes a strong case that many “able and available” disqualifications—most especially, disqualifying UI claimants from seeking part-time work—are in direct violation of the Americans with Disabilities Act, citing the following language from Title II:

no qualified individual with a disability shall, by reason of such disability, be excluded from participation in or be denied the benefits of the services, programs, or activities of a public entity, or be subjected to discrimination by any such entity.

The most critical thing that we could do to ensure people with disabilities are treated equally in the UI system would be to strike the “able and available” language and replace it with language that gets more directly to the point—workers are available to take appropriate and accessible job offers. The change to this language would have multiple knock-on effects, from applications and continued claims forms being more effectively worded, to not offering unnecessary discouragement to people with disabilities, to actually being more precise in telling people what is expected of them.

The most critical thing that we could do to ensure people with disabilities are treated equally in the UI system would be to strike the “able and available” language and replace it with language that gets more directly to the point

Sick Days

The 2007 regulations36 that contained the able and available requirements, which were promulgated at the tail end of the administration of President George W. Bush, gave states a relatively high degree of flexibility to make determinations about whether someone is “able and available.” For the purposes of this report, it is worth noting that there is specific flexibility around determination of illness in section 604.4 that says:

If an individual has previously demonstrated his or her ability to work and availability for work following the most recent separation from employment, the State may consider the individual able to work during the week of unemployment claimed despite the individual’s illness or injury, unless the individual has refused an offer of suitable work due to such illness or injury.

Some states will deny weekly eligibility on the basis of even a single day of illness. This could be a significant issue for claimants with periodic chronic illness. It seems unfair to have stricter rules for collecting UI than many places of employment and even entire states have about allowing workers paid sick time. Legislative remedies vary. States should consider establishing a very flexible rule around this. States with paid sick leave would stand on solid ground to make the case for allowing unemployed workers at least as many sick days as they had accrued at the job they lost. Ultimately, federally, the ideal solution would be to require states to consider claimants to be fulfilling their requirements so long as notwithstanding the illness they would be able to accept suitable work and they did not refuse meaningful, gainful, appropriate work due to that illness. While UI should not be a replacement for paid sick and family leave, allowing continued weekly claims to flow to claimants who felt ill for a day during that week should not be conflated with basing an unemployment claim on an illness.

Work Search Requirements

In keeping with the theme above, there are numerous considerations to ensure that work search requirements are sensible for all workers. (See Appendix 2 for an overview of state work search requirements taken from the U.S. Department of Labor Comparison of State Unemployment Insurance Laws 2022 and the fifty-three state system websites.) Work search requirements and instructions vary widely by states, so it might be helpful to create some kind of federal model work search standard. This will help both advocates and states to navigate complex terrain and share information and best practices.

One of the most important observations is that states should make work search requirements easy to find and understand. As with so many of these recommendations, this is one that will ultimately also help states with their improper payment rates, as one of the main causes for overpayments is claimants making mistakes on performing or tracking work search. One positive example is the way that the Ohio state website lays out work search requirements37 over time.

A key policy decision a state must make is whether to require claimants to log their work searches with the state each week, or keep their own log. While it could be argued that required paperwork minimization is the highest and best goal for claimant-friendliness, a poorly kept home log without immediate feedback from the state could result in later audits revealing systemic errors on the claimant’s end due to a lack of proof, even if the claimant performed legitimate work searches. A well-designed and user-tested log reported to the state weekly might be the best solution for claimants. However, given that a relatively high number of claimants in some states do weekly reporting by phone, some solution to simplify that reporting or record phone logs might be necessary, although difficult for states to implement. One solution might be to allow work search to be stored online but not required, as it appears New York handles the logging issue.

Another complaint that applicants often raise is the amount of information that has to be reported for each activity. Some states require comprehensive contact information for the prospective employer even if the applicant only used one form of contact. Sometimes information, such as a physical address, may not be easily ascertainable by the applicant. States should allow claimants to describe the work search activity and provide the means of contact they used to reach the employer. Because people with disabilities may be seeking employment through a variety of methods and with less traditional employers, being flexible while maintaining program integrity tends to be the best approach. It is also worth considering allowing claimants good cause for missing certain work search requirements.38

Generally, being very prescriptive about any requirement is going to be less accommodating. For example, Nebraska requires that claimants have an online searchable resume. Because people with disabilities are far more likely to to experience domestic violence,39 violence in general, and get less help with reports of domestic violence, it is especially exclusionary for them to be required to publish a document on the web that is expected to contain personal contact information.

Definition of Employee

Workers with disabilities are far more likely to be in nonstandard employment situations,40 including both as true independent contractors and also as so-called “gig workers” who might be in positions that should be covered by unemployment insurance but are not. To be considered a nonemployee, the ABC test requires that a worker must: (A) be free from control or direction; (B) the work is performed outside the usual course of business for an employer; and (C) the individual is customarily engaged in an independent trade. Thirty-five states use an employee definition that is some version of ABC or A+B, with twenty-three states having all of A+B+C in their laws. During the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, about half of workers who got a benefit received it through a new program called Pandemic Unemployment Assistance (PUA) which covered workers not eligible for regular UI, including people with COVID-19, caring for people with COVID19, people who must quarantine under medical advice, and those who were not in UI-covered employment. Put another way, if this past economic downturn had not been due to a pandemic, this suggests a huge swath of the unemployed would have gone without that safety net. The “gig-ification” of the workplace41 has been exploding in recent years, amplifying inequalities in society42 and cutting workers off from necessary worker protections. In terms of unemployment insurance, again, this is not just a problem for those workers and their families, but represents an existential threat to the UI’s ability to serve as a macroeconomic stabilizer during economic downturns.

Part Time

In the paper discussed above, Kohl makes the point that part-time work is a frequently requested accommodation. Her legal analysis is far more in-depth than this report intends to get, but the fundamental point is that covering part-time workers by itself is a fairness issue in light of the fact that employers pay federal and state unemployment taxes on behalf of workers regardless of their part-time status so this is an equally earned benefit. Paired with the fact that people with disabilities are more likely to need to work less than full time, this is clearly an issue of equity. Eleven states explicitly cover workers seeking part-time work due to a disability.43 UI should cover claimants who either lost part-time work and are seeking part-time work, or claimants who must leave full-time work but are still seeking part-time work. Covering claimants with a part-time work history seeking part-time employment has been included in several UI reform proposals, including the bipartisan 1996 Advisory Committee on Unemployment Compensation, the 2017 Obama administration budget proposal, the recently introduced bicameral legislative reform package44 led by Senators Ron Wyden (D-OR) and Michael Bennet (D-CO) and Representative Don Beyer (D-VA), and has been backed by UI scholars such as Christopher O’Leary, Stephen Wandner, David Balducchi, and Ralph Smith.

Standards for Partial UI

Every state has some allowance—partial UI—for people who lose work but are able to either maintain some hours at their old job or take part-time work in between positions. Partial UI allows people to work some hours and still receive part of their unemployment benefit. This report will advocate for more robust partial UI, but if the law is changed to allow claimants to quit full-time employment to seek part-time employment, consideration should be given to partial UI rules to make sure that this legitimate work choice does not create unintended consequences in the partial UI program by covering workers who have made a lifestyle choice to shift from full-time to part-time.

Furthermore, partial UI could be far more generous and inclusive. To be eligible for partial UI, states first gauge claimant earnings against a dollar amount they consider to be small enough that earnings beneath it can be disregarded in terms of offsetting the Weekly Benefit Amount (WBA). Then, there is a second dollar figure that claimants can earn while collecting offset UI benefit amounts. Table 3-8 in the Department of Labor Comparison of State Unemployment Insurance Laws45 outlines what these disregards and limits are. Disregard amounts can be as low as $30 and many states limit earnings to the state Weekly Benefit Amount. This can be a real problem because some states never index their maximum WBA, so in a state such as Arizona, the most a claimant can earn before being ineligible for any partial UI is $240 per week. The irony here is that the smaller the maximum WBA is, the greater the need to find supplemental income, which means the greater the likelihood of the claimant losing the benefit. Again, this is critical for people in communities that experience workplace discrimination because often a successful path back to gainful employment might include starting part-time.

Duration

There have been enormous strides in the employer community46 over time to build a culture of inclusion and accessibility, but still, disability discrimination is the second most prevalent kind reported to the U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, indicating that more progress can be made.47 When it is hard to get employers to hire a group of people, they tend to have longer durations of unemployment, but the duration of UI benefits in many states has been declining, leaving disabled workers—along with many workers in other historically marginalized groups—high and dry for longer periods during recent economic downturns.

The duration of UI benefits in many states has been declining, leaving disabled workers—along with many workers in other historically marginalized groups—high and dry for longer periods during recent economic downturns.

For example, the average duration of unemployment48 for white workers tends to hover around eighteen to twenty weeks, but for Black workers, unemployment spells tend to last closer to twenty-six weeks on average. One thing that Black workers and disabled workers have in common is that their unemployment rate is about double what it is for white nondisabled workers, so one could assume that duration issues are similar (and this effect is compounded when a worker is both Black and disabled). From the 1950s until the Great Recession, twenty-six weeks of base benefits with additional weeks potentially available during economic downturns or while a claimant is in an approved training program was standard. However, in the aftermath of the past two major recessions, states have been moving to cut weeks, with thirteen states offering fewer than twenty-six weeks of benefits.49

Compounding this problem, duration is also a huge challenge when it comes to triggering Extended Benefits (EB) during a downturn, which is why Congress often has to step in with Emergency Unemployment Compensation (EUC) weeks regularly during an economic crisis. EB has an automatic trigger in federal law, with optional state triggers that can cause it to kick in sooner and provides an additional number of weeks of benefits depending on how states exercise their options.

The complications with states triggering on to the automatic EB program are myriad. First, EB triggers are often tied to the Insured Unemployed (IU) rate, which means in some states with high hurdles to access UI, it is almost impossible for the number of unemployed people who can access benefits to trigger EB. For example, in 2019 in South Dakota only 11 percent of unemployed workers claimed benefits.50 Then, during the historic pandemic, the state IU level never got high enough to trigger EB.51 In addition, in order to qualify for EB, unemployment has to be 120 percent higher than the thirteen-week period in the same period of time as in the previous two years.52 States with stubbornly high unemployment can find it harder to trigger EB. Furthermore, the trend of cutting the number of weeks of regular UI also reduces the number of weeks of EB that will be available when it kicks in. It is widely believed that EB provides a base of thirteen to twenty additional weeks, however the base thirteen weeks is based on the outdated assumption that states are providing twenty-six weeks of base benefits. EB actually only provides an additional 50 percent increase in the current weeks available, so in some states, EB would only add an additional six weeks to the current minimum of twelve53 that states might enter a recession at, as happened in a couple of states as they entered the COVID-19 pandemic. That means that the current statutory trigger law might only get states to eighteen weeks of benefits in a crisis.

That leaves the duration of benefits in a crisis and at the mercy of the largesse of Congress. A troubling trend during both the Great Recession and the pandemic is a tendency to blame unemployed workers for the economy, instead of the other way around. In the late stages of the Great Recession, policymakers made claimant-unfriendly amendments as part of a bargain to extend duration of benefits in 2013, and these amendments included two modifications that explicitly and unfairly impact people with disabilities: the statutory addition of “able and available” language and expansion of drug testing to receive benefits. Medications that people might be prescribed to manage their disability, such as medical cannabis in states where it is legal, could unfairly trip drug tests, which is unfair, but not nearly so explicitly exclusionary as the addition of the “able and available” language in statute.

A troubling trend during both the Great Recession and the pandemic is a tendency to blame unemployed workers for the economy, instead of the other way around.

Couple all of this with the fact that, again, people who are discriminated against in the workplace tend to be the “first out, last in” during periods of economic crisis, and it is clear to see why policymakers must figure out a rational duration policy for both regular and extended benefits. Fortunately, every major UI reform proposal since the Great Recession has included some important provisions around base benefit duration.54

Caregiving Good Cause Quits and Dependents Allowances

Most of this report focuses on people with disabilities who are in the workforce. However, some people have disabilities that prevent them from working certain jobs, or working at all. Policymakers should consider their needs, as well as their loved ones and family members who provide them with support.

Unemployment insurance is not just for people who were laid off. There are numerous “good cause quits”55 that systems take into consideration. These good causes fall mainly into two categories: good personal cause and good work-related cause. For example, if an employer required an employee to do something illegal, or the workplace is unusually unsafe, workers in most states have the right to quit and still collect unemployment. In order to have truly accessible workplaces, violation of civil rights laws such as the ADA should work in much the same way that violation of other laws works. Often, workers are required to notify employers of the violation and give them an opportunity to remedy the situation before they quit, which can be helpful if an employer has made a mistake that they are willing to remedy in good faith, but in the case of a hostile work environment, it could exacerbate existing problems.

Good personal causes vary more widely across states and include things such as following a spouse who has had to relocate for work, escaping domestic violence, or due to an illness or to provide care for a family member. In any of these circumstances, the claimant would have to prove that they could still accept work, even though the current situation was not working out. A couple of examples of this are when a person develops a disability that renders them unable to perform their current job, such as a person with a seizure disorder who has to quit her bus driving job (discussed below), but who could work at another job that did not require the operation of heavy machinery. Alternatively, a person who provides caregiving to a family member from 6:00 PM through the night suddenly gets moved to second or third shift can quit and still receive benefits in some states. State good cause quits should be aligned so that people who leave jobs to accommodate a disability, when the employer violates the law, and to provide care to a family member with an illness or disability.

People with disabilities should not be required to accept work that does not provide accommodations or that could put their health and safety at risk.

Similarly, claimants are expected to accept any suitable work that is offered to them, or risk losing benefits. States have been lowering the bar on what can constitute suitable work, but actually ought to be expanded to take into account accessibility. People with disabilities should not be required to accept work that does not provide accommodations or that could put their health and safety at risk. Right now, the law only allows claimants to refuse work if “wages, hours, or other conditions of the work offered are substantially less favorable to the individual than those prevailing for similar work in the locality.”56 This has been a particularly difficult issue during COVID-19 because this standard could be interpreted to mean that if most businesses in a given area were not providing adequate ventilation, social distancing, and masking, claimants could be expected to take a job that put them at risk for contracting coronavirus. One of the first actions of the Biden administration on unemployment insurance was to issue a day one Executive Order to ensure that workers refusing unsafe work specific to the COVID-19 pandemic could access federal Pandemic Unemployment Assistance (PUA) benefits, and soon after codified that in Unemployment Insurance Program Letter 16-20 change 557 that claimants can certify their eligibility for UI if:

The individual has been denied continued unemployment benefits because the individual refused to return to work or accept an offer of work at a worksite that, in either instance, is not in compliance with local, state, or national health and safety standards directly related to COVID-19. This includes, but is not limited to, those related to facial mask wearing, physical distancing measures, or the provision of personal protective equipment consistent with public health guidelines.

This is closer to the standard we should consider for what constitutes safe work going forward. Any workplace that is violating local, state, or national health and safety standards should not be considered suitable.

Medical Cause Separations

Again, while paid medical and family leave should be available in every state to cover workers who would like to keep their jobs but experience a temporary health crisis or need to care for a loved one, sometimes a medical condition can force someone to leave their current employment even when they are able to work in another position. While people who quit their jobs totally voluntarily generally do not qualify for UI, there are basically two main types of “good cause quits” that states can consider covering in their UI programs—those that are related to compelling personal reasons such as following a relocating spouse who is a primary breadwinner, and those that are the fault of the employer, such as the employer breaking the law or asking the worker to do so. Medical quits can fall into either of these baskets, or as another kind of involuntary separation. For example, a case where a bus driver who develops a seizure disorder may be unable to drive a bus and the bus company might not have other positions available for that worker, but they could perform other work that does not require the operation of heavy equipment, should qualify as an involuntary separation. A worker who develops a disability for which the employer refuses to accommodate them could be considered a quit due to the employer violating the law. Kohl’s research finds that even when medical cause quits are allowable, documentation requirements and requirements that claimants exhaust multiple avenues prior to leaving work can be so extensive that they are effectively quite limited in application.58 States should consider ways to establish a good cause medical separation without making the process impossible to navigate.

Intersection with Social Security Disability Insurance (SSDI)

There are a couple of major problems that arise during the interaction between UI and Social Security Disability Insurance (SSDI). The first is individuals who are declared too disabled to work by the UI agency but not by the people determining SSDI eligibility, and thus find themselves in a position where they are ruled ineligible for either benefit. For these individuals, it is not generally the case that an SSDI denial can then be brought back to the UI agency to appeal an unfavorable “able and available” decision, and even if it were, the timing would not work. UI is designed to make quick and accurate determinations to be sure that claimants get their benefit “when due,” which means within a few weeks, and also has an appeals process that is supposed to move quickly, while SSDI determinations can take years. The pass-off process could go the other way, where a person deemed too disabled for UI by the state agency could use that denial of benefits as part of their application to be deemed eligible for SSDI, but again, there are process issues that make success unlikely. While the UI test for able and available is based on the state agency’s evaluation of a person’s disability and the job market and work search, the SSDI standard involves complex evaluation of an individual’s medical data. The SSDI program has the most strict definition of disability in any government program in the United States. Individuals must be unable to perform any work in the economy. The solution to this gulf between benefit programs is not obvious, but the problem is. This is an issue that should be examined more deeply through collaboration with the agencies involved to ensure that people don’t end up in the thorny briar patch between UI and SSDI.59

The second problem is about people moving in the other direction—from SSDI into the workforce. It has been a long-term goal of the SSDI program that people have paths available to them to move out of SSDI and into the workplace.60 Workers on SSDI can earn money so long as it does not exceed the “substantial gainful activity” threshold of $1,550 a month, and currently 28 percent of SSDI recipients work. SSDI claimants can also return to work for a limited trial period without any limit on earnings and become eligible for benefits again if their employment level drops. But some states will not allow people to receive SSDI and UI concurrently, even when a claimant involuntarily loses work. Because UI is designed to keep people attached to the workforce, denial of benefits for SSDI recipients attempting work seems counter to the goals of the Social Security Administration to help people move into gainful employment if they want to, and it is not the goal of state workforce agencies to sideline talent that wants to contribute to the economy.

Intersection with Workers’ Compensation

About half of states61 disqualify UI claimants if they are collecting Workers’ Compensation for a workplace injury. The existence of the Workers’ Compensation system should serve as a reminder to everyone that anyone can become disabled at any time, and one way that can happen is through workplace injury. One Social Security Administration review of SSDI recipients62 found that 37 percent became disabled due to workplace injuries and illnesses. Every worker who goes to work should have a 100 percent chance of returning home at the end of the day healthy and uninjured, but in the case that they do not, a robust system of workplace policies would ensure that they are compensated under the very specific program that is supposed to protect workers who lose work through no fault of their own as long as they are otherwise willing and available for work. As it stands, employers bear too little responsibility for injuring workers63—a slight increase in their UI payroll taxes resulting from covering workers losing employment due to injury is a small price for them to pay in order to ensure benefits for a worker that they failed to protect while on the job.

Alternative Base Period (ABP)

Some claimants do not apply for UI because their earnings histories are sporadic and may disqualify them. To avoid these unfortunate disqualifications, many states have a way of applying the earnings requirement across a different time frame—the Alternative Base Period (ABP)—so that people with less-stable earning histories can qualify. The standard Base Period (BP) is the first four of the past five quarters. Therefore, a claimant applying for benefits on April 1, 2024 would generally use the income from January to December of 2023. Many states allow, at least on paper if not in practice, for claimants who do not have qualifying income in that period to look at a different period of time. Usually that is the most recent four quarters, so in the same hypothetical application, the agency could use April 2023 to May 2024. However, there are even alternatives to the ABP, referred to as Extended Base Periods (EBP), to account for illness or disability complications. That way, someone who had quarters of income before and/or after an illness or disability can have them counted. Table 3-1 of the Department of Labor’s Comparison of State Unemployment Insurance Laws64 lays out the variation among states.

The Unemployment Insurance Modernization language65 enacted in the 2009 American Recovery and Reinvestment Act allocated $7 billion in incentive funding for states to improve their laws, and in order to receive this funding, states needed to adopt an Alternate Base Period. One weakness of that law was that it was an incentive, not a permanent requirement, which means that states were not required to maintain the ABP indefinitely. In order to create a program that truly accommodates the fact that a huge swath of people from disabled workers to people to take parental leave to people who have to take time off for an unexpected illness, we must make sure that those breaks in work history do not keep them from collecting earned unemployment benefits when they lose work involuntarily.

High-Quarter Method for Benefit Calculation

Many workers, including a large proportion of low-income workers, have earnings that vary between quarters. This can be particularly true for workers with disabilities who may have intermittent pay across calendar quarters. That is why basing the weekly benefit amount on the high quarter is more likely to provide a more sufficient weekly benefit than spreading that average over more quarters. For example, after Indiana shifted from a high-quarter average method to looking back to the full benefit year, benefit levels dropped precipitously the quarter that the new method went into effect.66 Currently, twenty-one states as well as Puerto Rico and the Virgin Islands67 have a methodology where the high quarter can be used or is always used. While it is true that states could change benefit formulas so that a shift to a high-quarter averaging method would not necessarily raise benefit levels, it would have the effect of leveling the playing field for people with less reliable work over the benefit year.

Hours Instead of Wages to Qualify

A better way of establishing benefit eligibility than the status quo in most states would be to use hours worked as a qualifying mechanism rather than wages. The vast majority of states68 have a minimum annual earnings requirement and just over half have a minimum earnings requirement in the high quarter. This can be a huge problem for people with disabilities because there is a specific provision in the Fair Labor Standards Act, section 14(c)69 that allows any employer to pay a person with a disability less than their counterparts, which can be as low as pennies on the dollar. Fortunately, the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights has recommended phasing out the 14(c) exemption,70 the Department of Labor is reviewing the 14(c) program,71 and several states have prohibited paying subminimum wage to people with disabilities72 amid massive public outcry to end the program. However, the exemption still exists today. Also, as discussed in depth below, people with disabilities are often relegated to “gig economy” work often not protected under wage and hour laws, so may end up earning less than the minimum wage in the hours they have worked. State UI laws should provide for the option that hours can count toward UI eligibility. For example, in Oregon, claimants who do not meet the monetary threshold can qualify if they have worked at least 500 hours in the base period.

Benefits in Approved Training Programs

To meet the policy goals of ensuring that people with disabilities have access to training opportunities that will provide better work options, Congress has passed and various administrations have implemented specific targeted options, such as the Ticket to Work73 and other training grants for disabled workers.74 Several states provide additional weeks of benefits to workers in training programs,75 and in Washington State, people with disabilities in need of training are specifically eligible for fifty-two additional weeks of benefits. Washington should be the model for all states.

Conclusion

The disability movement has fought and won monumental historic battles throughout history to ensure that people with disabilities have the opportunity to fully participate in society as full citizens and yet all too often we see systems failing to provide them with equal protection. In order to fully honor the critical role that people with disabilities play in our economy and society, and the untapped potential that discrimination robs from people and their communities, policymakers can and must do more in UI systems to elevate the necessity of allowing disabled workers access to earned benefits that their labor contributed to. This is an issue that touches everyone: one in four people in the United States currently has a disability,76 and the odds of developing a disability at some point in life are high. According to the Social Security Administration, “For an insured worker who attains age 20 in 2022, the probability of becoming disabled between age 20 and normal retirement age is 25 percent.”77 Now is the time to come together to ensure that our economy and systems provide a fair shot for everyone.

Acknowledgments

Thanks to Jody Calemine, Kings Floyd, Laura Haltzel, David Balducchi, Rachael Kohl, and Amy Traub for reviewing this paper and offering me thoughts on how to make it better.

Appendixes

- Download Appendix 1: Disability Access Fact Sheet

- Download Appendix 2: Work Search Requirements, by State

Notes

- “The Curb-Cut Effect,” National Cancer Institute, December 15, 2021, https://dceg.cancer.gov/about/diversity-inclusion/inclusivity-minute/2021/curb-cut-effect.

- Rachel Lichtman, “Navigation Anxiety: The Administrative Burdens of Being Poor and Disabled,” The Century Foundation, August 9, 2023, https://tcf.org/content/commentary/navigation-anxiety-the-administrative-burdens-of-being-poor-and-disabled/.

- Adriana Mitchell, “The Time Costs of Seeking Disability Accommodations,” The Century Foundation, June 14, 2023, https://tcf.org/content/commentary/the-time-costs-of-seeking-disability-accommodations/.

- Gemma Rigby, “The Application Process for Disability Benefits Shuts Out People In Need,” The Century Foundation, June 15, 2023, https://tcf.org/content/commentary/the-application-process-for-disability-benefits-shuts-out-people-in-need/.

- Michele Evermore, “Long lines for unemployment: How did we get here and what do we do now?” National Employment Law Project, August 11, 2023, https://www.nelp.org/publication/long-lines-for-unemployment-how-did-we-get-here-and-what-do-we-do-now/.

- “Disability Employment Statistics,” U.S. Department of Labor, accessed January 15, 2024, https://www.dol.gov/agencies/odep/research-evaluation/statistics.

- “Disability Employment Statistics,” U.S. Department of Labor, accessed January 15, 2024, https://www.dol.gov/agencies/odep/research-evaluation/statistics.

- “Economic Well-being of Households in 2022,” U.S. Federal Reserve, May 2023, https://www.federalreserve.gov/publications/files/2022-report-economic-well-being-us-households-202305.pdf.

- “5 common reasons 30% of Americans live paycheck to paycheck in 2023,” Nasdaq, September 1, 2023, https://www.nasdaq.com/articles/5-common-reasons-30-of-americans-live-paycheck-to-paycheck-in-2023#.

- “The Java decision,” U.S. Department of Labor, Unemployment Insurance Program Letter No. 1126, June 14, 1971, https://oui.doleta.gov/dmstree/uipl/uipl_pre75/uipl_1126.htm.

- “Wagner–Peyser Act Employment Service Results,” U.S Department of Labor, accessed January 15, 2024, https://www.dol.gov/agencies/eta/performance/results/wagner-peyser.

- “Reemployment Services and Eligibility Assessment Grants (RESEA),” U.S Department of Labor, accessed January 15, 2024, https://www.dol.gov/agencies/eta/american-job-centers/RESEA.

- Klaus-Peter Hellwig, “Supply and Demand Effects of Unemployment Insurance Benefit Extensions: Evidence from U.S. Counties,” International Monetary Fund, March 12, 2021, https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WP/Issues/2021/03/12/Supply-and-Demand-Effects-of-Unemployment-Insurance-Benefit-Extensions-Evidence-from-U-S-50112.

- “Suitable work” is a term of art in UI systems that differs across states. Generally, claimants are not expected to accept work that is not “suitable,” which often means they don’t have to accept work with substantially lower pay or working conditions. However, states have been eroding this standard, which is another major issue that must be addressed.

- A. Farooq, A. D. Kugler, and U. Muratori, “Do Unemployment Insurance Benefits Improve Match and Employer Quality? Evidence from Recent U.S. Recessions,” National Bureau of Economic Research, Working Paper 27574, July 2020, https://doi.org/10.3386/w27574.

- Nanette Goodman, Michael Morris, and Kelvin Boston, “Financial Inequality: Disability, Race and Poverty in America,” National Disability Institute, 2019, https://www.nationaldisabilityinstitute.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/disability-race-poverty-in-america.pdf.

- M. Ditkowsky, “New data on Disability Employment: Small gains but institutional barriers remain,” National Partnership for Women and Families, October 19, 2023, https://nationalpartnership.org/new-data-on-disability-employment-small-gains-but-institutional-barriers-remain/.

- “Understanding Supplemental Security Income SSI Resources,” Social Security Administration, https://www.ssa.gov/ssi/text-resources-ussi.htm#:~:text=WHAT%20IS%20THE%20RESOURCE%20LIMIT,and%20%243%2C000%20for%20a%20couple.

- “Equitable Access in the Unemployment Insurance (UI) Program,” U.S. Department of Labor, Unemployment Insurance Program Letter 01-24, November 8, 2023, https://www.dol.gov/sites/dolgov/files/ETA/advisories/UIPL/2024/UIPL%2001-24/UIPL%2001-24.pdf.

- https://oui.doleta.gov/unemploy/filingmethods/filingclaims.asp

- “Employment Laws: Disability & Discrimination,” U.S. Department of Labor, https://www.dol.gov/agencies/odep/publications/fact-sheets/employment-laws-disability-and-discrimination

- “Equitable Access in the Unemployment Insurance (UI) Program,” U.S. Department of Labor, Unemployment Insurance Program Letter 01-24, November 8, 2023, https://www.dol.gov/sites/dolgov/files/ETA/advisories/UIPL/2024/UIPL%2001-24/UIPL%2001-24.pdf.

- Michele Evermore, “New Jersey’s Worker-Centered Approach to Improving the Administration of Unemployment Insurance,” The Heldrich Center for Workforce Development, Rutgers University, September 2023, https://heldrich.rutgers.edu/sites/default/files/2023-09/New_Jersey%E2%80%99s_Worker-centered_Approach_to_Improving_the_Administration_of_Unemployment_Insurance.pdf.

- “Language portfolio,” U.S. Department of Labor, https://www.dol.gov/agencies/eta/ui-modernization/language-portfolio.

- “Behavioral Insights,” National Association of State Workforce Agencies, https://www.naswa.org/integrity-center/behavioral-insights.

- Michele Evermore, “New Jersey’s Worker-Centered Approach to Improving the Administration of Unemployment Insurance,” The Heldrich Center for Workforce Development, Rutgers University, September 2023, https://heldrich.rutgers.edu/sites/default/files/2023-09/New_Jersey%E2%80%99s_Worker-centered_Approach_to_Improving_the_Administration_of_Unemployment_Insurance.pdf.

- For multiple reasons, it would also be a good idea for legislative language and administrative guidance to use the term “their” rather than “his or her.”

- “State Responsibilities for Ensuring Access to Unemployment Insurance Benefits,” U.S. Department of Labor, Unemployment Insurance Program Letter 02-16, October 1, 2016, https://oui.doleta.gov/dmstree/uipl/uipl2k16/uipl_0216.pdf.

- “State Responsibilities for Ensuring Access to Unemployment Insurance Benefits,” U.S. Department of Labor, Unemployment Insurance Program Letter 02-16, change 1, May 1, 2020, https://www.dol.gov/sites/dolgov/files/ETA/advisories/UIPL/2020/UIPL_02-16_Change-1.pdf.

- “Equitable Access in the Unemployment Insurance (UI) Program,” U.S. Department of Labor, Unemployment Insurance Program Letter 01-24, November 8, 2023, https://www.dol.gov/sites/dolgov/files/ETA/advisories/UIPL/2024/UIPL%2001-24/UIPL%2001-24.pdf.