The COVID-19 pandemic has been a clarion call on health equity—the lack of true accountability measures for ensuring equitable solutions in the health policy response to the pandemic only served to delay meaningful traction on issues such as expanding access to affordable health insurance, equitable access to COVID-19 treatment and vaccines, and supporting individuals and families with the wrap-around supports needed in order to survive the crisis. This was not the first time the United States has had to grapple with a pandemic, and it will not be the last.

The nation is at a critical moment for advancing health equity, as it also contends with a worsening maternal health crisis,1 higher rates of depression and anxiety,2 and other concerns. America needs a more substantive examination of how its health care system is working (or failing) to ensure meaningful implementation of health equity for the most vulnerable among us.

America Can Do Better in Advancing Equity in Health Coverage Reforms

Progress has been made in recent years toward advancing health equity, particularly through the Affordable Care Act (ACA), which significantly reduced racial disparities in health coverage. Under the ACA, national uninsured rate fell from nearly 18 percent (around 46.5 million people) in 20103 to only 8.0 percent (around 26.5 million people) by early 2022, according to recent estimates by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.4Much of this decrease was seen among people of color. The uninsured rate for Hispanic people fell from 30.1 percent in 2010 to 17.7 percent in 2020, a 12.4-percentage-point decrease.5 Similarly, the uninsured rate for Black people fell from 17.5 percent in 2010 to 9.9 percent in 2020, a 7.6-percentage-point drop.6

The ACA also included several provisions to improve the value of this coverage to patients. For example, health insurers are now required to cover all preventive services that the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force gives an A or B rating with no cost sharing.7 As a result, services like well woman visits, pre-exposure prophylaxis to prevent HIV, and cancer screenings are now much more accessible to insured patients;8 a recent report by the Health Services and Resources Administration estimated that more than 150 million privately insured people benefited from the preventive services mandate in 2020 alone, along with more than 80 million people insured by Medicaid and Medicare.9

Despite this progress, disparities in health coverage still exist. As of 2020, Black people are still uninsured at a rate four percentage points higher than for white people (9.9 percent versus 5.9 percent), and Hispanic people are still uninsured at a rate 11.8 percentage points higher (17.7 percent versus 5.9 percent).10 Figure 1 shows uninsured rate by race and ethnicity for the past several years.

Figure 1

Even among insured patients, federal policies contribute to coverage that fails to meet the needs of marginalized people. While the ACA as passed required Medicaid expansion in every state, this provision was made optional by the U.S. Supreme Court in its ruling in NFIB v. Sebelius.11 While most states and the District of Columbia have expanded the program,12 twelve states still have not, and are generally considered unlikely to do so.13 This failure to expand Medicaid has resulted in a coverage gap of around 2.2 million people with incomes too high to qualify for Medicaid but too low for subsidized marketplace coverage, and the people that fall in this gap are disproportionately people of color.14

This failure to expand Medicaid has resulted in a coverage gap of around 2.2 million people with incomes too high to qualify for Medicaid but too low for subsidized marketplace coverage, and the people that fall in this gap are disproportionately people of color.

Similarly, while the American Rescue Plan Act created a state plan amendment option for states to extend postpartum Medicaid coverage to a full year, seventeen states have not extended or begun the process of extending their coverage to a full year.15 Under the House-passed Build Back Better Act, this extension would have been mandatory for five years beginning in 2022,16 but the provision was removed from the Senate’s reconciliation bill.

As a result of these federal policies, marginalized people are often left at the mercy of their state governments, and state policies often do not meet these people’s health needs. As mentioned above, several states have not extended postpartum Medicaid coverage, and federal law broadly prohibits federal funds from being spent on undocumented immigrants’ health coverage,17 meaning that they are ineligible for Medicaid coverage and subsidies for marketplace coverage unless states fund it solely themselves. Only eight states and the District of Columbia provide full scope Medicaid coverage to undocumented immigrants, and these states overwhelmingly restrict coverage to children and seniors.18

A Framework for Assessing Equity in Health Coverage

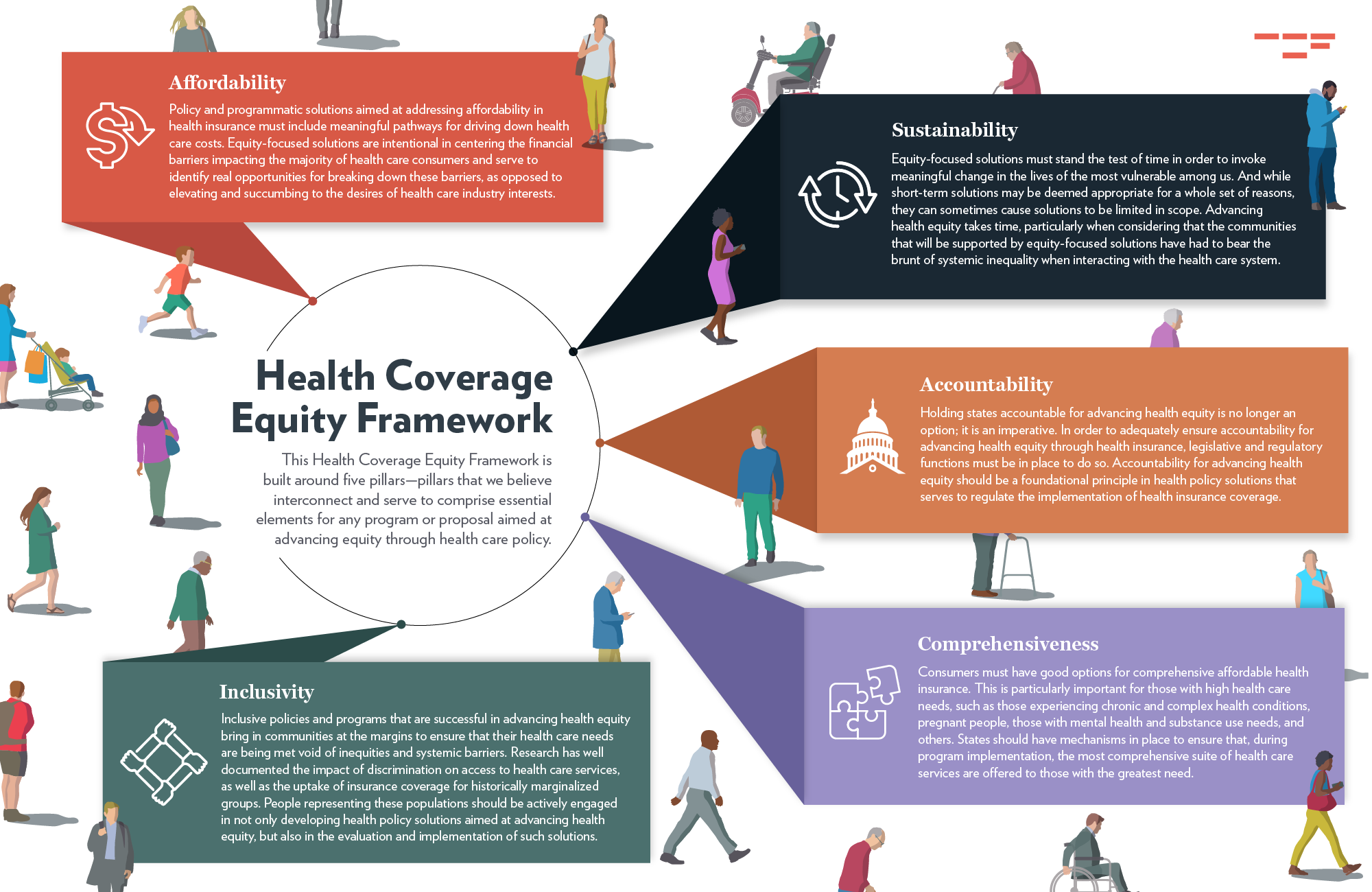

In order to better advance the nation’s health equity, it is important first to gauge where health care policy currently falls short—not only the populations that are being left behind, but also the dimensions of health care policy in which equity is not being achieved. In order to measure progress (or lack thereof) in equity in health coverage, The Century Foundation has developed this Health Coverage Equity Framework, presented below.

This Health Coverage Equity Framework is built around five pillars—pillars that we believe interconnect and serve to comprise essential elements for any program or proposal aimed at advancing equity through health care policy.

This framework was developed in order to serve as a tool for policymakers to assess meaningful implementation of goals and objectives aimed at realizing health equity through expansion of health insurance coverage and affordability. It is our hope that stakeholders across the health equity and insurance coverage spaces find the tool useful as states and the federal government work to enhance health coverage in ways that serve to advance health equity and ensure comprehensive, affordable insurance coverage for all.

Overview

This Health Coverage Equity Framework is built around five pillars—pillars that we believe interconnect and serve to comprise essential elements for any program or proposal aimed at advancing equity through health care policy. While the framework is used here specifically to assess state progress toward more equitable health coverage, it can also be used to assess equity more broadly throughout health care systems. In any case, a health care policy or program designed to advance equity must be comprehensive and designed so as to ensure affordability, sustainability, accountability, comprehensiveness, and inclusivity:

- Affordability: Policy and programmatic solutions aimed at addressing affordability in health insurance must include meaningful pathways for driving down health care costs. Equity-focused solutions are intentional in centering the financial barriers impacting the majority of health care consumers. They also serve to identify real opportunities for breaking down these barriers, as opposed to elevating and succumbing to the desires of health care industry interests.

- Sustainability: Equity-focused solutions must stand the test of time in order to invoke meaningful change in the lives of the most vulnerable among us. And while short-term solutions may be deemed appropriate for a whole set of reasons—such as political dynamics within a given state or even at the national level, or the policy confines of a particular legislative vehicle—they can sometimes be limited in scope. Advancing health equity takes time, particularly when considering the fact that the communities that will be supported by equity-focused solutions have had to bear the brunt of systemic inequality over the long-term when interacting with the health care system.

- Accountability: Holding states accountable for advancing health equity is no longer an option, it is an imperative. In order to adequately ensure accountability for advancing health equity through health insurance, legislative and regulatory functions must be in place to do so. Accountability for advancing health equity should be a foundational principle in health policy solutions that serves to regulate the implementation of health insurance coverage.

- Comprehensiveness: Consumers must have good options for comprehensive affordable health insurance. This is particularly important for those with high health care needs, such as those experiencing chronic and complex health conditions, pregnant people, those with mental health and substance use needs, and others. States should have mechanisms in place to ensure that, during program implementation, the most comprehensive suite of health care services are offered to those with the greatest need.

- Inclusivity: Inclusive policies and programs that are successful in advancing health equity bring in communities at the margins to ensure that their health care needs are being met void of inequities and systemic barriers. Not only should barriers related to cost and financial feasibility be addressed, but also those related to structural racism, sexism, and other forms of discrimination. Research has well documented the impact of discrimination on access to health care services,19 as well as the uptake of insurance coverage for historically marginalized groups such as women and birthing people, people of color, the undocumented, and LGBTQ+ people. People representing these populations should be actively engaged not only in developing health policy solutions aimed at advancing equity, but also in evaluating and implementing such solutions.

Applying the Health Equity Framework

Many states are already applying some of the pillars that comprise this framework to help achieve progress toward health equity. This section provides several examples of how states are implementing these pillars within their health care systems through equitable health coverage and describes how their resulting policies advance health equity.

Affordability

The foundational pillar of this framework is affordability. Enacting changes to how health insurance programs operate will not advance health equity if patients are unable to afford coverage in the first place, or the resulting costs for care under that coverage. This includes efforts to make coverage more affordable through subsidies and similar policies, as well as efforts to address the underlying cost of care, a critical aspect of ensuring that the cost of health coverage is affordable for patients.

One of the most basic steps that many states have taken to improve the affordability of health coverage in recent years is expanding Medicaid under the ACA to households with incomes at or below 138 percent of the federal poverty level (FPL). By doing so, these states have ensured that restrictive eligibility policies are not barriers to low-income people accessing health coverage. Map 1 shows the current status of Medicaid expansion by state.

Map 1

This expansion is especially important at making health coverage more affordable and improving health equity. In 2022, 138 percent of the FPL amounts to less than $19,000 a year for a single adult and less than $32,000 a year for a family of three.20 Federal law generally prohibits charging households that earn less than these amounts a premium,21 and it also limits any cost-sharing, such as copays or deductibles, that these households face to “nominal amounts.”22

People of color—especially Black and Hispanic people—are significantly more likely to have household incomes below the poverty line: in 2019, Black people were more than 2.5 times as likely as white people to live below the poverty line, and Hispanic people were more than twice as likely.23 Because childless adults were largely ineligible for Medicaid regardless of income prior to the ACA,24 expanding the program is especially important for improving coverage rates and affordability among people of color.

Because childless adults were largely ineligible for Medicaid regardless of income prior to the ACA, expanding the program is especially important for improving coverage rates and affordability among people of color.

Some states have also worked to promote affordability throughout the commercial market. Maryland has pioneered in this space, establishing the Maryland Health Services Cost Review Commission in the 1970s.25 The commission is empowered to directly set the rates that hospitals may charge payers in the state, and the state received a waiver to require Medicare and Medicaid to pay these same rates in the late 1970s, ensuring that these rates are truly universal within the state.26

The commission has two goals that affect the pillar of affordability: constraining hospital cost growth and ensuring that all Marylanders have access to needed hospital services.27 This first goal is critical in ensuring that the cost of care is kept in check, thus ensuring that the cost of health coverage to pay for that care remains affordable for patients. Similarly, the commission’s efforts to ensure that all Marylanders have access to care is the core of broader efforts to make health coverage more affordable.

A 2021 evaluation of several Medicare models by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) found that Maryland’s model reduced Medicare spending by slowing hospital cost growth.28 The same evaluation found that this approach reduced potentially avoidable hospitalizations and mortality rates.29 The uniformity of rates across settings has also been attributed to ensuring that uninsured patients have access to care, as the rates hospitals are paid already factor in the cost of uncompensated care throughout the state.30

Many states have also enacted new public option programs that include some level of cost containment as an explicit goal. For example, Nevada’s public option includes lowering premiums for consumers and lowering the overall cost of care as goals.31 The program also includes promoting value-based financing as a component of the program, which is essential to lowering the cost of health care. Colorado’s law also includes this goal, looking to significantly lower premiums for enrollees each year, but allowing the insurers that operate the public option plans to achieve these savings independently.32 The focus on both premiums and the cost to the health care system ensure that these efforts will be felt by patients while policymakers work to bend the cost curve.

Sustainability

In addition to helping make coverage affordable, efforts to improve health equity must be lasting, rather than being embraced and abandoned as political dynamics shift. The structural drivers of inequity are well-established and will take time to undo. Policymakers should ensure that reforms to the health system are integrated throughout the system to maximize their impact.

The risk of creating unsustainable changes in health care policy can be seen in states with significant executive authority over their health programs. While executive authority can empower elected officials committed to advancing health equity, it can also result in whiplash once officials less committed to this goal are elected. For example, a Kentucky law allows the eligibility for and generosity of its Medicaid program to be modified by regulations where the governor’s office is not explicitly directed to take a course of action by the state legislature.33

While executive authority can empower elected officials committed to advancing health equity, it can also result in whiplash once officials less committed to this goal are elected.

This expansive power allowed former Governor Steve Beshear (D-KY) to expand the program administratively in 2014,34 but it also gave his successor, Governor Matt Bevin (R-KY), the power to end this expansion as he threatened to do in 2018 after facing legal challenges to the state’s work requirement.35 (Governor Andy Beshear (D-KY) issued an executive order rescinding this work requirement after his inauguration in 2019.36) While the ability of the governor to expand Medicaid administratively has allowed the state to avoid the lengthy battle to expand the program other southern states currently face37, it also allowed Governor Bevin to undermine the program by imposing work requirements and limiting eligibility.

Other states, however, have integrated reforms to their health programs in a more lasting way, effecting persistent changes to how their state’s health system operates. Oregon, for example, has transitioned its Medicaid program over the past decade to heavily use coordinated care organizations (CCOs).38 These organizations are networks of medical and behavioral health providers who work together to promote preventive care and help manage chronic health conditions.39 More than 90 percent of all Oregon Medicaid beneficiaries (1.3 million out of 1.4 million total enrollees) are enrolled in a CCO,40 highlighting the extent to which this approach is embedded in the state’s health system.

Accountability

Underpinning any reform must be a commitment to advancing health equity. If the goal of health equity is not part of the foundation of reform, policymakers and regulators risk making it an afterthought. As the impact of the ACA on health coverage rates shows, neutral attempts to improve health care access that do not center health equity will be insufficient in closing health disparities. Several states have started incorporating this approach into their policymaking, making important progress toward true health equity.

States that have enacted public options have made health equity a core goal of their programs. Nevada’s public option, for example, has two goals that do so:41 (1) improving access to care and reducing disparities in care for historically marginalized communities, and (2) improving the availability of coverage for rural residents. Intentionally centering health equity in the legislative text has had a real impact on how the regulations for this program have been issued.

States that have enacted public options have made health equity a core goal of their programs.

One of Nevada’s public comment sessions for its public option was devoted to discussing the target population for the program and how the state can maximize the benefit of a public option to that population.42 During this discussion, the state highlighted the reality that the uninsured population ineligible for other programs was split between undocumented immigrants and families whose income made them ineligible for subsidies, but who still found coverage unaffordable—two populations who will likely require different policy solutions to improve coverage rates. Colorado’s public option law also includes a requirement that the plan be designed to “improve racial health equity and decrease racial health disparities through a variety of means, which are identified collaboratively with consumer stakeholders.”43 This requirement has influenced much of the design of the program, discussed later in this section.

Washington’s public option demonstrates the need to ensure that health system reforms include mechanisms to hold actors within the system accountable. Like Colorado and Nevada, Washington’s public option includes lowering costs as a goal, and the law limited aggregate provider reimbursement rates at 160 percent of Medicare rates for comparable services as a way to achieve this goal.44 However, because the law did not initially include any mechanism to ensure providers contracted with the public option, more than half of the counties in the state did not have a public option plan available its first year.45 Provisions to ensure participation, such as those Washington added in the subsequent legislative session,46 are essential to holding the health industry accountable for improving health equity.

States have also taken efforts to address the underlying systemic inequities in the factors that drive much of a person’s health outcomes. While not directly related to reforming health insurance or providers, these factors, called social determinants of health or social drivers of health (SDOH), include a wide range of topics,47 such as safe housing, access to healthy foods, and reliable transportation, and they drive as much as 40 percent of a person’s overall health.48 Reducing disparities within SDOHs is a necessary step toward achieving health equity, and the existing health system can be used to do so.

North Carolina has recently implemented a pilot program to address SDOHs among its Medicaid population. Called the Health Opportunities Pilots program,49 the initiative uses up to $650 million in federal funding over five years to help screen and connect Medicaid enrollees with housing, food, and transportation needs, as well as interpersonal safety. The state Department of Health and Human Services created a list of standardized questions for health providers to screen patients for a variety of social needs and a platform for providers to then connect those patients with social services organizations who can help meet them.50

North Carolina is not alone in using Medicaid to address social determinants of health: CMS has approved 1115 waivers in fifteen other states to address SDOHs, most of which focus on housing supports.51 Ten states also have pending SDOH waivers with CMS.52

Comprehensiveness

Pursuing health equity also requires that health insurance must cover the services that people actually need to live healthy lives. Low-cost insurance plans that do not actually cover the services a patient needs have been called junk plans,53 but even qualifying health coverage (insurance that meets the ACA’s requirement to have health coverage) may not cover all the services that a patient needs,54 or may only do so with high cost sharing or restrictive utilization management policies, especially for marginalized populations. Many states have worked to address this reality by requiring coverage of benefits or restricting cost-sharing.

One of the most common ways states have implemented this pillar of health equity is by extending postpartum Medicaid eligibility.

One of the most common ways states have implemented this pillar of health equity is by extending postpartum Medicaid eligibility. Federal law requires states to cover pregnant women with incomes up to 138 percent of the FPL for the duration of their pregnancy and sixty days postpartum,55 and the American Rescue Plan Act created a state plan amendment option that allows states to extend this coverage to twelve months postpartum.56 Currently, twenty-three states and the District of Columbia have extended Medicaid coverage for a full twelve months, and another ten states are planning to do so.57 Map 2 shows the states that have extended this coverage or that plan to.

Map 2

This extension is important for several reasons. First, around 12 percent of pregnancy-related deaths occur after the first six weeks postpartum.58 Second, Medicaid covers more than 40 percent of all births in the United States, and for Black and Hispanic pregnant people, this number is even higher (65.1 percent and 59 percent in 2019, respectively).59 Extending postpartum coverage means that when a potentially deadly health issue arises, patients will not be discouraged from seeking care due to concerns over cost. As the United States faces a maternal mortality crisis driven by disproportionately high maternal mortality rates among Black and Native American women,60 this extension is all the more crucial.

Many states have also used their Medicaid programs to improve the generosity of Medicaid coverage to pregnant beneficiaries. In attempts to address the maternal mortality crisis, some states have expanded the types of providers that can be reimbursed by Medicaid to include midwives and doulas. Doulas are trained nonclinical professionals who support patients before, during, and after birth, such as creating birth plans, advocating for patients during appointments, and providing emotional support during labor.61 Midwives are clinical workers who traditionally provided care to pregnant women until the early twentieth century.62 Currently, seventeen states and the District of Columbia allow midwives with “alternative pathways to licensure,”63 in addition to certified nurse-midwives, to be reimbursed by Medicaid. Similarly, six states now reimburse for doula services under Medicaid, and another five and the District of Columbia plan to apply to the Centers for Medicaid and Medicare Services for the ability to do so this year or next.64

The difference these providers make to women and other pregnant people is well-documented.65 Multiple studies have found that doula and midwife support are associated with lower rates of maternal and infant health complications, lower rates of preterm and low-birth-weight infants, and lower rates of C-sections. These benefits are even greater for low-income and marginalized women.66 In addition to improving health outcomes for women and other pregnant people, there is evidence that doulas lower the cost of care: a 2016 study published in Birth found that doulas were associated with around $1,000 in savings per birth,67 making these providers doubly beneficial to policymakers.

In addition to extending the length and generosity of coverage in Medicaid, states have also led by more heavily restricting cost-sharing in private coverage. Even relatively small levels of cost-sharing—as low as $1—can have a significant impact on patients’ ability to access care.68 This effect is even greater for lower-income patients, even when they face relatively cheaper cost-sharing. In particular, states are working to eliminate cost-sharing for diabetes management: new research by the Georgetown Center on Health Insurance Reforms shows that five states and the District of Columbia have restricted or plan to restrict cost-sharing for diabetes-related items and services.69

In addition to extending the length and generosity of coverage in Medicaid, states have also led by more heavily restricting cost-sharing in private coverage.

Massachusetts has implemented a variety of restrictions on cost-sharing, requiring marketplace health insurers in the state to cover services with no copayments. In 2023, marketplace plans will be prohibited from imposing cost-sharing on “high-value medications” on four health conditions that disproportionately impact people of color: diabetes, asthma, coronary artery disease, and hypertension (high blood pressure).70 These carriers will also be required to increase their gender-affirming care policies for transgender patients, helping ensure access to these medically necessary treatments.71 The District of Columbia has also taken steps to ensure cost sharing is not a barrier to care in an effort to improve health equity. In addition to eliminating cost-sharing for diabetes management services, the district’s health exchange is assessing the impact of doing so for some cancers, as well as HIV treatment.72

Colorado’s public option law also focuses on comprehensive coverage: Colorado Option plans are required to cover federally qualified health centers (FQHCs), which disproportionately serve patients of color, and they are also required to provide pre-deductible coverage for “high-value services” such as primary care.73 As a result of this coverage requirement and stakeholder meetings discussed in the next section, the Colorado Division of Insurance required coverage of midwives and established strong physical distance requirements for network adequacy.74

Inclusivity

Importantly, states will need to intentionally address barriers unique to marginalized populations to improve health equity, and policy solutions to address these barriers should include buy-in from the patients being served by health programs.

The first step toward creating inclusive health policies is understanding the demographics being served by health insurers and providers. New York has taken notable steps toward achieving this goal with its recent changes to how race and ethnicity data are collected on its marketplace, New York State of Health. In fall of 2020, the agency operated a pilot program testing several changes to how assisters and navigators helping patients enroll in coverage collect this data.75 The question was made mandatory (though consumers could select “Don’t know” and “Choose not to answer”) and was preceded by a short paragraph describing how the information would and would not be used.

The first step toward creating inclusive health policies is understanding the demographics being served by health insurers and providers.

Participants in the pilot saw a 20 percentage point increase in responses for race (64 percent in 2021 versus 44 percent in 2020) and an 8 percentage point increase in responses for ethnicity (88.3 percent in 2021 versus 80.3 percent in 2020).76 Other navigators only saw a 0.9 percentage point increase for race and a 1.4 percentage point decrease for ethnicity over the same period. This suggests that explaining how the information will be used to improve health disparities and requiring a response with appropriate opportunities for patients to keep that information private can lead to significant increases in demographic information collection.

Colorado has also led on implementing the inclusivity pillar. The law that established Colorado’s public option laid out several requirements for the program’s networks, such as they must include consumer stakeholders in the regulatory process. The Colorado Division of Insurance held several stakeholder meetings throughout the design process for its public option benefit.77 Several of these were intentionally held with specific communities to ensure their voices were heard, including the disability community, rural communities, and consumer advocates broadly.78

States have also worked to eliminate the nonfinancial barriers to accessing care. One of the most obvious ways that some states have done so is by removing immigration status as a barrier to coverage. Under federal law, undocumented immigrants are not eligible for Medicaid or to purchase private coverage through an ACA marketplace,79 even if their income is below the eligibility thresholds for those programs, and lawfully present immigrants typically have to wait five years to be eligible for Medicaid.

States have also worked to eliminate the nonfinancial barriers to accessing care. One of the most obvious ways that some states have done so is by removing immigration status as a barrier to coverage.

States are permitted, however, to enroll undocumented immigrants in Medicaid if their costs are solely covered through state funds.80 State actions in this vein have largely focused on children and are still uncommon: only eight states and the District of Columbia provide comprehensive coverage to all low-income children, regardless of immigration status.81 California is currently the only state planning to allow all low-income adults to enroll in Medicaid. Currently, income-eligible people under age 26 and age 50 or older are eligible regardless of immigration status, and by January 1, 2024, adults age 26–49 will be included as well.82

Under Colorado’s recently approved 1332 waiver for its public option, the state plans to establish state subsidies to make health coverage more affordable.83 As part of its plan to ensure the public option improves health disparities, these subsidies will also be made available to undocumented patients.84

Moving Forward with Intention on Equity

A more intentional focus on advancing equity within America’s health care system has never been more pivotal. And while we are seeing better access to affordable health insurance coverage, as well as concrete gains in a number of states as outlined in this report, vulnerable communities still far too often experience grave challenges in accessing comprehensive, affordable health care. Furthermore, vast racial disparities persist—making optimal health and well-being out of reach for many people of color, low-income people, women and birthing people, LGBTQ+ people, and other historically oppressed groups. The framework outlined in this paper was developed in the hopes that it can be used as a tool by key stakeholders to assess health policy in ways that ensure true implementation of concrete solutions that meaningfully advance health equity.

Notes

- Jamila Taylor et al., “The Worsening U.S. Maternal Health Crisis in Three Graphs,” The Century Foundation, March 2, 2022, https://tcf.org/content/commentary/worsening-u-s-maternal-health-crisis-three-graphs/.

- Alice Louise Kassens, Jamila Taylor, and William M. Rodgers, “Mental Health Crisis during the COVID-19 Pandemic,” The Century Foundation, May 11, 2021, https://tcf.org/content/report/mental-health-crisis-covid-19-pandemic/.

- Jennifer Tolbert, Kendal Orgera, and Anthony Damico, “Key Facts about the Uninsured Population,” Kaiser Family Foundation, November 6, 2020, https://www.kff.org/uninsured/issue-brief/key-facts-about-the-uninsured-population/.

- Aiden Lee et al., “HP-2022-23 National Uninsured Rate Reaches All-Time Low in Early 2022,” U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, August 2, 2022, https://aspe.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/documents/15c1f9899b3f203887deba90e3005f5a/Uninsured-Q1-2022-Data-Point-HP-2022-23-08.pdf.

- Author analysis of Census Bureau American Community Survey data, https://data.census.gov/cedsci/table?q=uninsured%20rate&tid=ACSST5Y2020.S2701.

- Ibid.

- 42 USC 300gg-13.

- Jamila Taylor et al., “The ACA Improved Access to Health Insurance for Marginalized Communities, but More Work Is Needed to Ensure Universal Coverage,” The Century Foundation, March 23, 2022, https://tcf.org/content/commentary/the-aca-improved-access-to-health-insurance-for-marginalized-communities-but-more-work-is-needed-to-ensure-universal-coverage/.

- “Access to Preventive Services without Cost-Sharing: Evidence from the Affordable Care Act,” Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation, January 11, 2022, https://aspe.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/documents/786fa55a84e7e3833961933124d70dd2/preventive-services-ib-2022.pdf.

- Author analysis of Census Bureau American Community Survey data, https://data.census.gov/cedsci/table?q=uninsured%20rate&tid=ACSST5Y2020.S2701.

- National Federation of Independent Business v. Sebelius, 567 U.S. 519 (2012).

- Status of State Medicaid Expansion Decisions: Interactive Map,” Kaiser Family Foundation, June 29, 2022, https://www.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/status-of-state-medicaid-expansion-decisions-interactive-map/.

- Sara Rosenbaum, “Why Medicaid Expansion States Are Unlikely to Eliminate Coverage If Congress Enacts a New Pathway for Residents in Coverage Gap,” The Commonwealth Fund, July 20, 2021, https://www.commonwealthfund.org/blog/2021/why-medicaid-expansion-states-are-unlikely-eliminate-coverage-if-congress-enacts-new.

- Rachel Garfield, Kendal Orgera, and Anthony Damico, “The Coverage Gap: Uninsured Poor Adults in States That Do Not Expand Medicaid,” Kaiser Family Foundation, January 21, 2021, https://www.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/the-coverage-gap-uninsured-poor-adults-in-states-that-do-not-expand-medicaid/.

- “Medicaid Postpartum Coverage Extension Tracker,” Kaiser Family Foundation, August 25, 2022, https://www.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/medicaid-postpartum-coverage-extension-tracker/.

- Cynthia Cox et al., “Potential Costs and Impact of Health Provisions in the Build Back Better Act,” Kaiser Family Foundation, November 23, 2021, https://www.kff.org/health-costs/issue-brief/potential-costs-and-impact-of-health-provisions-in-the-build-back-better-act/.

- Health Coverage of Immigrants,” Kaiser Family Foundation, April 6, 2022, https://www.kff.org/racial-equity-and-health-policy/fact-sheet/health-coverage-of-immigrants/.

- Tanya Broder, “Medical Assistance Programs for Immigrants in Various States,” National Immigration Law Center, July 2022, https://www.nilc.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/med-services-for-imms-in-states-2022-07-18.pdf.

- Brigette A. Davis, “Discrimination: A Social Determinant Of Health Inequities,” Health Affairs Forefront, February 25, 2020, https://doi.org/10.1377/forefront.20200220.518458.

- “HHS Poverty Guidelines for 2022,” Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation, January 12, 2022, https://aspe.hhs.gov/topics/poverty-economic-mobility/poverty-guidelines.

- “Cost Sharing and Premiums,” Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Access Commission, accessed September 7, 2022, https://www.macpac.gov/subtopic/cost-sharing-and-premiums/.

- “Out of Pocket Costs,” Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, accessed September 7, 2022, https://www.medicaid.gov/medicaid/cost-sharing/cost-sharing-out-pocket-costs/index.html.

- John Creamer, “Inequalities Persist Despite Decline in Poverty For All Major Race and Hispanic Origin Groups,” U.S. Census Bureau, September 15, 2020, https://www.census.gov/library/stories/2020/09/poverty-rates-for-blacks-and-hispanics-reached-historic-lows-in-2019.html.

- MaryBeth Musumeci and Kendal Orgera, “People with Disabilities Are At Risk of Losing Medicaid Coverage Without the ACA Expansion,” Kaiser Family Foundation, November 2, 2020, https://www.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/people-with-disabilities-are-at-risk-of-losing-medicaid-coverage-without-the-aca-expansion/.

- Harold A. Cohen, “Maryland’s All-Payor Hospital Payment System,” Maryland Health Services Cost Review Commission, accessed September 7, 2022, https://hscrc.maryland.gov/Documents/pdr/GeneralInformation/MarylandAll-PayorHospitalSystem.pdf.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- “Synthesis of Evaluation Results across 21 Medicare Models, 2012–2020,” Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, July 2022, https://innovation.cms.gov/data-and-reports/2022/wp-eval-synthesis-21models.

- Ibid.

- Cohen, “Maryland’s All-Payor Hospital Payment System.”

- Nevada Legislature, “SB 240,” June 9, 2021, https://www.leg.state.nv.us/Session/81st2021/Bills/SB/SB420_EN.pdf.

- Colorado General Assembly, “HB 21-1232,” June 16, 2021, https://leg.colorado.gov/sites/default/files/2021a_1232_signed.pdf.

- Kentucky Revised Statutes 205.520.

- Sarah Kliff and Byrd Pinkerton, “Interview: Former Gov. Steve Beshear Explains How He Sold Deep-Red Kentucky on Obamacare,” Vox, February 27, 2017, https://www.vox.com/policy-and-politics/2017/2/27/14725782/steve-beshear-kentucky-obamacare.

- John Cheves, “Bevin Orders End to Expanded Medicaid If Courts Block Work Requirement, Other Changes,” Lexington Herald Leader, January 16, 2018, https://www.kentucky.com/news/politics-government/article194975584.html.

- Crystal Staley, “Governor Beshear Ends Medicaid Waiver, Protects Health Care for Nearly 100,000 Kentuckians,” Office of the Governor, December 16, 2019, https://kentucky.gov/Pages/Activity-stream.aspx?n=GovernorBeshear&prId=7.

- “Southerners for Medicaid Expansion,” Southerners for Medicaid Expansion, accessed September 7, 2022, https://southerners4medex.org/.

- “Coordinated Care: the Oregon Difference,” Oregon Health Authority, accessed September 7, 2022, https://www.oregon.gov/oha/HPA/Pages/CCOs-Oregon.aspx.

- Ibid.

- “CCO Totals by County for: Physical Health, OHP, & CAK, Aug 2022,” Oregon Health Authority, April 28, 2022, https://app.powerbigov.us/view?r=eyJrIjoiMTRhMmNhZDktYzY4OS00MzIxLTg4NTAtNjc4NmVlNjA1NzI4IiwidCI6IjY1OGU2M2U4LThkMzktNDk5Yy04ZjQ4LTEzYWRjOTQ1MmY0YyJ9&pageName=ReportSection726184bb48f86b1a99c4; “Total Oregon Health Plan (OHP) Enrollment,” Oregon Health Authority, August 16, 2022, https://www.oregon.gov/oha/HSD/OHP/DataReportsDocs/snapshot081622.pdf.

- “Nevada Public Option—Target Launch Date: January 1, 2026,” Nevada Department of Health and Human Services, accessed April 26, 2022, https://dhhs.nv.gov/PublicOption/.

- “Nevada Public Option Implementation Design Session #3,” Nevada Department of Health and Human Services, January 5, 2022 https://dhhs.nv.gov/uploadedFiles/dhhsnvgov/content/Resources/PublicOption/Design%20Session%203%20Public%20Meeting_F.pdf.

- Colorado General Assembly, “HB 21-1232,” June 16, 2021, https://leg.colorado.gov/sites/default/files/2021a_1232_signed.pdf.

- “Cascade Care FAQ,” Washington State Health Care Authority, January 2020, https://www.hca.wa.gov/assets/program/cascade-care-one-pager.pdf.

- Stephanie Carlton, Jessica Kahn, and Mike Lee, “Cascade Select: Insights From Washington’s Public Option,” Health Affairs Blog (blog), August 30, 2021, https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/forefront.20210819.347789.

- Sam Hatzenbeler, “Cascade Care 2.0 Passes the Senate!” Economic Opportunity Institute, March 4, 2021, https://www.opportunityinstitute.org/blog/post/cascade-care-2-0-passes-the-senate/.

- “Social Determinants of Health,” Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, accessed September 7, 2022, https://health.gov/healthypeople/priority-areas/social-determinants-health.

- John Walton Senterfitt et al., “How Social and Economic Factors Affect Health,” Los Angeles County Department of Public Health, January 2013, http://www.publichealth.lacounty.gov/epi/docs/SocialD_Final_Web.pdf.

- “Healthy Opportunities Pilots,” North Carolina Department of Health and Human Services, August 24, 2022, https://www.ncdhhs.gov/about/department-initiatives/healthy-opportunities/healthy-opportunities-pilots.

- “Screening Questions,” North Carolina Department of Health and Human Services, accessed September 7, 2022, https://www.ncdhhs.gov/about/department-initiatives/healthy-opportunities/screening-questions; “NCCARE360,” North Carolina Department of Health and Human Services, accessed September 7, 2022, https://www.ncdhhs.gov/about/department-initiatives/healthy-opportunities/nccare360.

- “Medicaid Waiver Tracker: Approved and Pending Section 1115 Waivers by State,” Kaiser Family Foundation, August 19, 2022, https://www.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/medicaid-waiver-tracker-approved-and-pending-section-1115-waivers-by-state/#Table3.

- Ibid.

- Michelle Andrews, “Think Your Health Care Costs Are Covered? Beware The ‘Junk’ Insurance Plan,” NPR, December 3, 2020, https://www.npr.org/sections/health-shots/2020/12/03/941620737/think-your-health-care-costs-are-covered-beware-the-junk-insurance-plan.

- “Qualifying Health Coverage,” Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, accessed September 7, 2022, https://www.healthcare.gov/glossary/qualifying-health-coverage/.

- Ivette Gomez et al., “Medicaid Coverage for Women,” Kaiser Family Foundation, February 17, 2022, https://www.kff.org/womens-health-policy/issue-brief/medicaid-coverage-for-women/.

- Usha Ranji, Alina Salganicoff, and Ivette Gomez, “Postpartum Coverage Extension in the American Rescue Plan Act of 2021,” Kaiser Family Foundation, March 18, 2021, https://www.kff.org/policy-watch/postpartum-coverage-extension-in-the-american-rescue-plan-act-of-2021/.

- “Medicaid Postpartum Coverage Extension Tracker,” Kaiser Family Foundation, August 25, 2022, https://www.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/medicaid-postpartum-coverage-extension-tracker/.

- Emily E. Petersen et al., “Vital Signs: Pregnancy-Related Deaths, United States, 2011–2015, and Strategies for Prevention, 13 States, 2013–2017,” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, May 10, 2019, https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/68/wr/mm6818e1.htm.

- Joyce A. Martin, Brady E. Hamilton, and Michelle J. K. Osterman, “Births in the United States, 2019,” National Center for Health Statistics, October 2020, https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db387-H.pdf.

- Jamila Taylor, Anna Bernstein, Thomas Waldrop, and Vina Smith-Ramakrishnan, “The Worsening U.S. Maternal Health Crisis in Three Graphs,” The Century Foundation, March 2, 2022, https://tcf.org/content/commentary/worsening-u-s-maternal-health-crisis-three-graphs/.

- “What Is a Doula?” DONA International, accessed September 7, 2022, https://www.dona.org/what-is-a-doula/.

- “What Is a Midwife?” Midwives Alliance of North America, accessed September 7, 2022, https://mana.org/about-midwives/what-is-a-midwife.

- Emily Creveling, “Midwife Medicaid Reimbursement Policies by State,” National Academy for State Health Policy, April 15, 2022, https://www.nashp.org/midwife-medicaid-reimbursement-policies-by-state/.

- Tomás Guarnizo, “Doula Services in Medicaid: State Progress in 2022,” Georgetown Center For Children and Families, June 2, 2022, https://ccf.georgetown.edu/2022/06/02/doula-services-in-medicaid-state-progress-in-2022/.

- Jamila Taylor et al., “Eliminating Racial Disparities in Maternal and Infant Mortality: A Comprehensive Policy Blueprint,” Center for American Progress, May 2, 2019, https://www.americanprogress.org/article/eliminating-racial-disparities-maternal-infant-mortality/.

- Kenneth J. Gruber, Susan H. Cupito, and Christina F. Dobson, “Impact of Doulas on Healthy Birth Outcomes,” The Journal of Perinatal Education 22, no. 1 (2013): 49–58, https://doi.org/10.1891/1058-1243.22.1.49.

- Katy B. Kozhimannil et al., “Modeling the Cost-Effectiveness of Doula Care Associated with Reductions in Preterm Birth and Cesarean Delivery,” Birth 43, no. 1 (January 14, 2016): 20–27, https://doi.org/10.1111/birt.12218.

- Samantha Artiga, Petry Ubri, and Julia Zur, “The Effects of Premiums and Cost Sharing on Low-Income Populations: Updated Review of Research Findings,” Kaiser Family Foundation, June 1, 2017, https://www.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/the-effects-of-premiums-and-cost-sharing-on-low-income-populations-updated-review-of-research-findings/.

- Christine Monahan and Jalisa Clark, “Using Health Insurance Reform to Reduce Disparities in Diabetes Care,” The Commonwealth Fund, August 18, 2022, https://www.commonwealthfund.org/blog/2022/using-health-insurance-reform-reduce-disparities-diabetes-care.

- “Health Equity Initiatives in the 2023 Seal of Approval,” Massachusetts Health Connector, March 10, 2022, https://www.mahealthconnector.org/health-equity-initiatives-in-the-2023-seal-of-approval.

- “Health Insurance Coverage for Genderaffirming Care of Transgender Patients,” American Medical Association, 2019, https://www.ama-assn.org/system/files/2019-03/transgender-coverage-talking-points.pdf.

- Dania Palanker, “Recommendations of the Standard Plans Advisory Working Group to the District of Columbia Health Benefit Exchange Authority,” DC Health Benefit Exchange Authority, November 8, 2021, https://hbx.dc.gov/sites/default/files/dc/sites/hbx/event_content/attachments/Standard%20Plans%20Advisory%20Group%20Report%20VBID%2011%208%2021%20final%20%28002%29_0.pdf.

- Liz Hagan and Rachel Bonesteel, “How Colorado Is Designing Culturally Responsive Networks,” United States of Care, October 12, 2021, https://unitedstatesofcare.org/advancing-equity-through-public-options-how-colorado-is-designing-culturally-responsive-networks/.

- “Regulation 4-2-80 Concerning Network Adequacy Standards and Reporting Requirements for Colorado Option Standardized Health Benefit Plans,” Colorado Division of Insurance, accessed September 7, 2022, https://drive.google.com/file/d/1FHGriZRgQu7iiM0X5otSTNGL61-Ch69Q/view.

- Colin Planlp, “New York State of Health Pilot Yields Increased Race and Ethnicity Question Response Rates,” State Health and Value Strategies, September 9, 2021, https://www.shvs.org/new-york-state-of-health-pilot-yields-increased-race-and-ethnicity-question-response-rates/.

- Colin Planlp, “New York State of Health Pilot Yields Increased Race and Ethnicity Question Response Rates,” State Health and Value Strategies, September 9, 2021, https://www.shvs.org/new-york-state-of-health-pilot-yields-increased-race-and-ethnicity-question-response-rates/.

- “2023 Standardized Plan Materials,” Colorado Division of Insurance, accessed September 7, 2022, https://drive.google.com/drive/folders/11WF8y86784eF89VS3w4zJCJTZClcWD4G.

- “2023 Standardized Plan Materials,” Colorado Division of Insurance, accessed September 7, 2022, https://drive.google.com/drive/folders/11WF8y86784eF89VS3w4zJCJTZClcWD4G.

- “Health Coverage of Immigrants,” Kaiser Family Foundation, April 6, 2022, https://www.kff.org/racial-equity-and-health-policy/fact-sheet/health-coverage-of-immigrants/.

- “Health Coverage of Immigrants,” Kaiser Family Foundation, April 6, 2022, https://www.kff.org/racial-equity-and-health-policy/fact-sheet/health-coverage-of-immigrants/.

- Tanya Broder, “Medical Assistance Programs for Immigrants in Various States,” National Immigration Law Center, July 2022, https://www.nilc.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/med-services-for-imms-in-states-2022-07-18.pdf.

- “Budget Information: 2022-23 Budget Act,” California Department of Health Care Services, July 22, 2022, https://www.dhcs.ca.gov/Pages/Governors-Budget-Proposal.aspx.

- “Colorado: State Innovation Waiver,” Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, June 23, 2022, https://www.cms.gov/newsroom/fact-sheets/colorado-state-innovation-waiver-0.

- Tara Straw, “Innovative 1332 Waivers Proceed in Colorado and Washington,” JD Supra, June 29, 2022, https://www.jdsupra.com/legalnews/innovative-1332-waivers-proceed-in-5212867/.