Introduction

As the United States experiences dramatic demographic change—and as our society’s income inequality continues to rise—promoting racial, ethnic, and economic inclusion at selective colleges has become more important than ever. Most people recognize that to be economically competitive and socially just, America needs to draw upon the talents of students from all backgrounds. Moreover, the education of all students is enriched when they can learn from classmates who have different sets of life experiences.

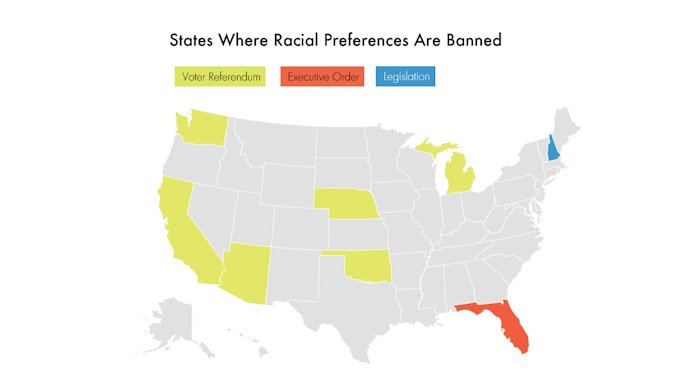

At the same time, however, many Americans—including several members of the U.S. Supreme Court—are uneasy with explicitly using race as a factor in college admissions. To date, several states, with more than a quarter of the nation’s population, have banned the use of race in admissions at public colleges and universities, prompting institutions of higher education to experiment with a variety of new paths to diversity.

In the Supreme Court’s most recent case, Fisher v. University of Texas (2013), the justices placed new emphasis on a requirement that universities use race in admissions only when “necessary.” In a key passage, the Court ruled that universities bear “the ultimate burden of demonstrating, before turning to racial classifications, that available, workable race-neutral alternatives do not suffice.”1 While in the past, the Court took universities at their word that race-neutral strategies were not sufficient, in Fisher the Court, for the first time, held that universities would receive “no deference” from judges on whether using race is in fact necessary.2 Legal observers believe the decision has implications for both private and public universities because the Court has ruled that Title VI of the Civil Rights Act (which applies to all higher education institutions receiving federal funding) has the same meaning as the Fourteenth Amendment of the Constitution.3

Higher education officials are understandably resistant to efforts by courts to closely scrutinize their use of race in admissions. No one likes to be told what to do, and in the case of college admissions, university officials are right to guard their academic freedoms strenuously. Moreover, these officials contend that, if a school’s goal is racial diversity, why not just let admissions officers consider race in admissions directly, as opposed to constructing less efficient, indirect means of creating a racially diverse student body?

In the Fisher case, though, only one justice—Ruth Bader Ginsburg— took that position, as the other members of the Court’s 7-1 majority said race should only be employed when absolutely necessary. Many legal experts suggest that now is the time for universities to begin seriously thinking about how to promote racial, ethnic, and economic diversity in new ways.4 In August 2013, on the heels of the Fisher decision, Lumina and Century assembled some of the country’s best minds to address this issue at a conference titled “New Paths to Higher Education Diversity.” The meeting included university and college presidents, admissions officers, government officials, civil rights leaders, legal experts, higher education scholars, and members of the philanthropic community. This volume is an outgrowth of that gathering.

In their chapters, the authors tackle the critical questions: What is the future of affirmative action given the requirements of the Fisher court? What can be learned from the experiences of states that created race-neutral strategies in response to voter initiatives and other actions banning consideration of race at public universities? What does research by higher education scholars suggest are the most promising new strategies to promoting diversity in a manner that the courts will support? How do public policies need to change in order to tap into the talents of all students in a new legal and political environment?

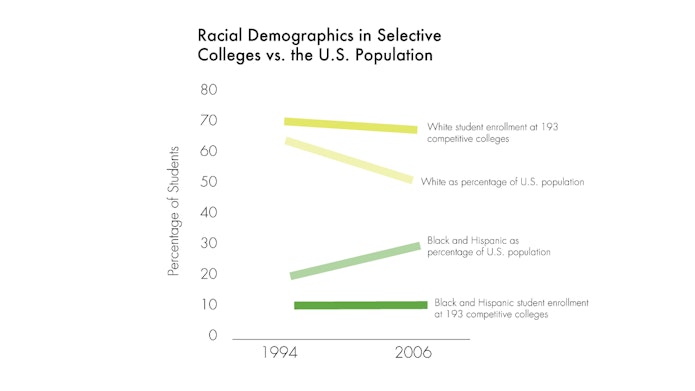

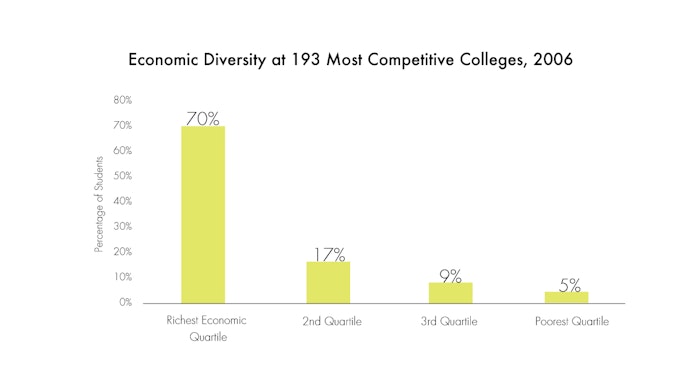

Although all of the conference participants and authors in this volume support racial and ethnic inclusion, some also see the judiciary’s new emphasis on race-neutral strategies as an opportunity to broaden higher education’s notion of diversity to include economic status as well as race and ethnicity. To date, many universities have achieved racial and ethnic diversity by recruiting fairly well off students of color. According to William G. Bowen and Derek Bok’s The Shape of the River, 86 percent of African American students at selective colleges are middle or upper-class—and the whites are even wealthier.5 According to a different study by Bowen, being an underrepresented minority increases one’s chances of being admitted to a selective college by 28 percentage points, but being low income provides no positive boost.6 Nationally, 41 percent of undergraduate students had family incomes low enough to be eligible for Pell Grants in 2011-12, yet at selective colleges the proportion is usually much lower.7 At the University of Virginia and Duke University, to take two examples, only 13 percent of students are Pell eligible.8

In a 2013 report, Anthony Carnevale and Jeff Strohl noted that while white students are overrepresented at selective colleges by 15 percentage points, the overrepresentation of high-income students is 45 percentage points, three times greater.9

Despite greater attention being paid to higher education’s income divide than in the past, progress has been slow. In 2013, Catharine Hill reported that “only 10 percent of students attending selective colleges and universities came from the bottom 40 percent of the income distribution in 2001, and that little progress had been made by 2008, except at a few of the very wealthiest institutions.”10

Many of the race-neutral approaches outlined in this volume emphasize efforts to embrace economically disadvantaged students of all races. In that sense, might Fisher represent not only a new challenge to the use of racial criteria but also a new opportunity to tackle, at long last, burgeoning economic divisions in society? Can new approaches be created that honor racial, ethnic, and economic diversity in one fell swoop?

This volume proceeds in five parts.

The Stakes

Part I addresses the stakes involved in diversity discussions. Why do racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic diversity matter in higher education? Why are universities right not to simply select the students with the highest grades and test scores irrespective of diversity? Why, indeed, should we care at all about who attends selective colleges in the first place?

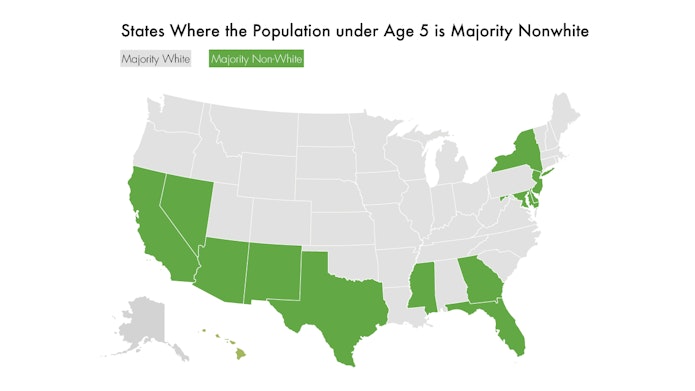

In Chapter 2, Nancy Cantor, the president of Rutgers Newark and the former chancellor of Syracuse University, explains with her colleague Peter Englot that racial, ethnic, and economic diversity on campus is vital. They begin by citing the economic imperative of tapping into the talents of America’s new majority. The twin trends of increasing economic inequality and the racial and ethnic shift in the population mean that America can no longer afford to bypass its growing number of low-income and minority students. The toddler population is already majority minority in fourteen states, including California, New York, Texas, and Florida, they write.

“If we do not dramatically expand college access and opportunity for poor students generally and minority students specifically, we are headed for a catastrophe,” they predict.11 Failing to educate this growing portion of the population means “losing the very talent that can rebuild our communities and create civic renewal.”12

They also cite the critical ways in which campus diversity enriches the learning experience of all students. When students bring differing life experiences to discussions, they “strongly enrich the quality, creativity, and complexity of group thinking and problem-solving” that occurs.13 Research finds that groups including individuals with different perspectives outperform groups of individual high performers in problem solving “because diverse groups increase the number of approaches to finding solutions to thorny problems.”14 More broadly, students take away critical social skills in diverse environments. “Learning how to work and learn and live across difference,” they argue, is “a prerequisite to a vibrant democracy.”15

In Chapter 3, Sara Goldrick-Rab of the University of Wisconsin at Madison offers an additional, less widely recognized reason that economic diversity on campus is important. Not only does having students from a variety of economic backgrounds enhance the learning and discussions on campus, it also might make college more affordable for everyone, she argues. Selective colleges are economically segregated in part because they are so expensive.

But the converse may also be true: colleges are expensive because they cater to such a wealthy clientele. Rich students expect certain amenities (fitness centers, well-manicured lawns, elaborate sports facilities) that drive up costs. Having economic diversity on campus would temper these pressures, she says, and balance university priorities to serve all students.

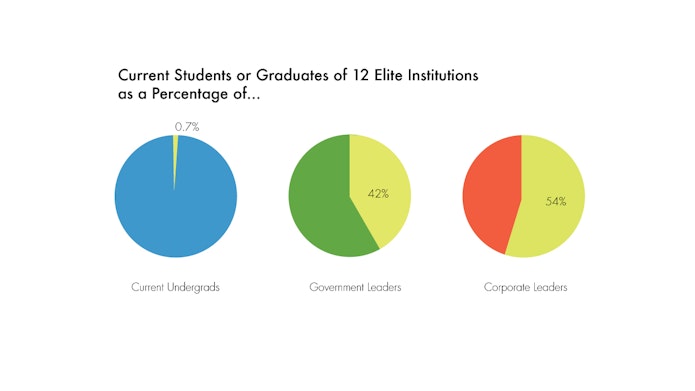

Diversifying selective colleges matters not just because of the effect on campus climates but also because attending selective colleges provides entre into America’s leadership class. According to research by political scientist Thomas Dye, 54 percent of America’s top corporate leaders and 42 percent of government leaders are graduates of just twelve universities.16

And diversifying selective colleges is likely to lead to a net increase in the total earnings of graduates. Research by Princeton’s Alan Krueger and Stacey Dale of Mathematica Policy Research finds that attending a selective college has little impact on the earnings of advantaged students but can have a substantial impact on the earnings of first-generation and minority students, perhaps because they are exposed to new social networks that put them on a different trajectory in life.17

The Legal Challenge

Part II of the book examines the legal environment and the meaning of the Supreme Court’s decision in Fisher v. University of Texas. In concrete and practical terms, what do universities need to begin to do to produce diversity in a way that will avoid litigation?

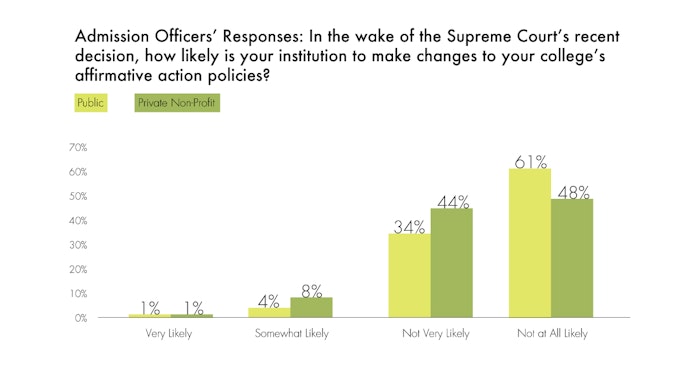

The threshold legal question is: To what degree (if any) did Fisher alter the law from where it stood in the 2003 decision in Grutter v. Bollinger, in which the Supreme Court upheld affirmative action at the University of Michigan Law School? There is some evidence that many universities greeted Fisher with a yawn. A 2013 Inside Higher Ed poll of admissions officers, for example, found that only 1 percent of public and private institutions were “very likely” to change policies after Fisher. Only 4 percent of public and 8 percent of private institutions were “somewhat likely” to change.18

But the legal analysis in this volume suggests universities must carefully reexamine their policies.

In Chapter 4, Arthur Coleman and Teresa Taylor of Education Counsel LLC and the College Board’s Diversity and Access Collaborative note that while some perceived Fisher as “a dud” it is in fact “a decision of consequence,” one with “important implications for the higher education community.”19 In Chapter 5, higher education attorney Scott Greytak goes even further, declaring “Fisher represents a deliberate and measured step forward on the path to colorblindness. It is a blueprint for destabilizing race-conscious admissions plans. This is our warning, and we must react accordingly.”20 Although Coleman, Taylor and Greytak are all supporters of race-conscious affirmative action, they believe universities must change their way of approaching the issue in light of Fisher.

While Fisher broadly reaffirmed Grutter’s support of diversity as a compelling interest worthy of pursuit, there are critical differences in the two rulings. As Coleman and Taylor note, of the five justices who participated in both Grutter, upholding affirmative action, and Fisher, vacating a lower court decision that supported affirmative action and remanding the case for further review, four switched sides. Justices Anthony Kennedy, Clarence Thomas, and Antonin Scalia dissented in Grutter and joined the majority in Fisher; while Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg was in the majority in Grutter and dissented in Fisher. (Only one justice, Stephen Breyer, joined the majority in both cases.)21

What accounts for the switches? Many observers believe that in Fisher, Justice Kennedy was essentially able to make his dissent in the Grutter case the law of the land. Kennedy dissented in Grutter in part because he believed that Justice Sandra Day O’Connor’s majority opinion did not apply genuine strict scrutiny, a demanding level of judicial review that places a heavy burden on universities to prove that using race is necessary. A true strict scrutiny, Kennedy wrote in Grutter, would “force educational institutions to seriously explore race-neutral alternatives. The [Grutter] Court, by contrast, is willing to be satisfied by the Law School’s profession of its own good faith.”22 Grutter, as Greytak suggests, spawned “a decade of deference,” in which universities were not pressed on the issue of race-neutral alternatives.23 In Fisher, by contrast, universities receive “no deference” on whether using race is necessary. To drive home the point, Kennedy wrote in Fisher that “Strict scrutiny must not be strict in theory but feeble in fact.”24 Fisher’s emphasis on race-neutral alternatives was foreshadowed, Greytak argues, in the 2007 Parents Involved v. Seattle case involving the use of race at the K-12 level, in which Kennedy wrote that “individual racial classifications may be considered only if they are a last resort to achieve a compelling state interest.”25

In Fisher, rather than directly rebuking the majority in Grutter, Kennedy admonished the lower court for applying a watered-down and overly deferential type of strict scrutiny. But most realize this was an artifice, for Kennedy was asking the lower court to apply a version of strict scrutiny that, Coleman and Taylor note, was “not present in Grutter.”26 The target of Kennedy’s ire, Judge Patrick Higginbothom of the Fifth Circuit, wryly noted during a November 2013 hearing of the remanded Fisher case that the Fifth Circuit’s mistake was “in not following the dissent in Grutter, by not anticipating that it would become [the rule.]”27

So what, as a practical matter, should universities and colleges begin to do? The chapters by Coleman and Taylor and by Greytak both home in on the meaning of the key passage: that universities bear “the ultimate burden of demonstrating, before turning to racial classifications, that available workable, race-neutral alternatives do not suffice.”28 A related passage provides, if a race-neutral approach “could promote the substantial interest about as well [as the race conscious approach] and at tolerable administrative expense,” the institution may not use race.29 In particular, three questions arise.

First, what is sufficient diversity? Presumably, sufficiency is tied to achieving a “critical mass” of minority students who will feel comfortable contributing to classroom discussions. In Fisher, the University of Texas avoided tying critical mass to a certain percentage of minority students, but it seems unlikely that the Supreme Court will ultimately accept a standard akin to what Fifth Circuit Judge Emilio Garza described as “know[ing] it when you see it.”30

Is critical mass tied to a level of minority representation that universities have achieved in the past using race? (The University of Michigan Law School, for example, defined 11-17 percent minority as having achieved critical mass.)31 Are changing demographics in a state relevant, or would a university taking that into account be involved in “racial balancing,” something that the Court has explicitly said is “patently unconstitutional”?32 As Harvard University’s Thomas Kane and James Ryan ask, if a race-neutral alternative can create 60 percent as much minority representation as using race, does that count as sufficient?33

Supreme Court decisions also raise a related consideration about sufficiency. As Coleman and Taylor note, to be justified, racial preferences need to do more than provide a marginal boost in minority admissions. In the Parents Involved case, the Court struck down the use of race in K-12 schooling where the effect of using race was marginal, and specifically contrasted the case to Grutter, in which the University of Michigan Law School’s use of race had a significant impact, boosting minority enrollment from 4.5 percent to 14 percent.34

Second, what is the dividing line between a “workable” and “unworkable” race-neutral alternative? One aspect of this goes to academic selectivity. In Grutter, the majority said universities theoretically might achieve considerable racial diversity by using a lottery for admissions, but that would so fundamentally alter the academic nature of the institution as to render the alternative unworkable. But what about a much smaller diminution of selectivity? The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, for example, conducted a study which found that if Chapel Hill adopted a Top 10 Percent plan like that used in Texas—admitting all students with the highest GPAs within North Carolina’s individual high schools—the nonwhite under-represented student population would actually increase modestly over race-conscious admissions (from 15 percent to 16 percent) but the median SAT score would decline 50 points, from the ninety-first percentile to the eighty-sixth.35 Will courts suggest that avoiding such a modest decline justifies the use of racial preferences?

Another aspect of workability is cost and the issue of what constitutes a “tolerable administrative expense.”36 If a class-based affirmative action program were able to produce similar amounts of racial diversity using economic status rather than race but proved more expensive because it drove up financial aid costs, would that make the alternative unworkable? Coleman and Taylor note that there is little case law explaining the phrase “tolerable administrative expense,” and that the Supreme Court has often rejected cost as a rationale for abrogating rights when applying the strict scrutiny test. In Saenz v. Roe (1999), for example, the Court rejected the argument that California could impinge on the right to travel by reducing welfare benefits to those who were new to the state. The state said the rule saved taxpayers $10 million per year, but the Court ruled: “the State’s legitimate interest in saving money provides no justification for its decision to discriminate among equally eligible citizens.”37 Coleman and Taylor write: “an institution should not assume that cost savings alone can justify the ongoing use of a race-conscious policy.”38

Third, how does a university “demonstrate” that no workable race-neutral alternatives are available? Coleman and Taylor say that universities do not have to actually try out alternatives for a few years to see them fail; instead, the institution “must have a sound basis for a decision not to pursue a particular neutral strategy that is anchored in evidence and informed by the institution’s experience and expertise.”39 Under Fisher, Coleman and Taylor say, “an institution does not have to try every [race-]neutral strategy imaginable, but should review every strategy that could have some possible utility.”40

Clearly, the bar has been raised on what universities must do, and it would be foolish not be begin the analysis now. Greytak concludes: “While many in higher education believe that pursuing racial and ethnic diversity is a beneficial and just endeavor, they nevertheless serve their community best when they make preparations for the worst.”41 Many worry that universities are being too complacent. “In the wake of the Fisher decision,” Kane and Ryan write, “few universities and colleges are preparing to answer the questions that courts will soon be asking. If they fail to prepare convincing answers, they will lose. And, having been put on notice, responsibility for that loss will be with our college and university leaders, not the courts.”42

What are the most promising race neutral strategies that universities should examine? In the 1978 Bakke case, little was known about race-neutral approaches and universities said, in the words of Justice Harry Blackmun, that there was “no other way” to achieve racial diversity short of using race. Since then, however, several states—educating 29 percent of the national high school population—have banned racial affirmative action and have indeed found other ways to produce diversity.43

State Experiences with Race-Neutral Strategies

Part III of the book examines these states’ experiences and what can be learned from them. The section begins with an overview in Chapter 6 written by Century Foundation policy associate Halley Potter. She examines ten states where the use of race was eliminated by voter initiative or other means at leading universities. In these states, several steps that have been taken:

- Six states have spent money to create new partnerships with disadvantaged schools to improve the pipeline of low-income and minority students.

- Eight states have provided new admissions preferences to lowincome and working-class students of all races.

- Eight states have expanded financial-aid budgets to support the needs of economically disadvantaged students.

- In three states, individual universities have dropped legacy preferences for the generally privileged—and disproportionately white—children of alumni.

- In three states, colleges created policies to admit students who graduated at the top of their high-school classes.

- In two states, stronger programs have been created to facilitate transfer from community colleges to four-year institutions.

Have these universities done everything they could to promote racial and ethnic diversity indirectly? No. The University of Michigan, for example, still has only 15 percent of students eligible for Pell Grants, so presumably it could pursue class-based affirmative action more vigorously than it has.44 But as Potter notes, the states provide a “useful roadmap” for universities nationwide which are seeking racial diversity in a race-neutral manner.45

How effective were these strategies in promoting racial and ethnic diversity indirectly? Potter finds that at seven of the ten flagship universities where alternatives were put in place, institutions were able to match or exceed both black and Latino representation levels that had been achieved in the past using race.46 Research in other countries, such as Israel, has likewise found that race neutral strategies such as economic affirmative action can produce substantial racial and ethnic diversity.47

Potter’s overview sets the stage for more detailed discussions of raceneutral strategies in some of the states that have been grappling with alternatives for more than a decade—Texas, California, Washington, and Georgia.

In 1996, the Fifth Circuit struck down the use of racial preferences in higher education in the case of Hopwood v. University of Texas. In Chapter 7, Princeton University professor Marta Tienda, who has spent many years studying Texas’s response, provides a powerful analysis of the state’s race-neutral programs. To its credit, Texas did not simply give up on racial diversity after the ruling but instead created a number of new strategies. It provided an admissions break for economically disadvantaged students of all races, increased financial aid, and adopted the Top 10 Percent plan, which provides automatic admissions to the University of Texas (including the flagship Austin campus) to students who rank highest in their high school class, irrespective of standardized test scores. The law, Tienda writes, has been supported by “a bipartisan coalition of liberal urban minority legislators and conservative rural lawmakers,” whose constituents benefit.48

How effective were the race-neutral programs?

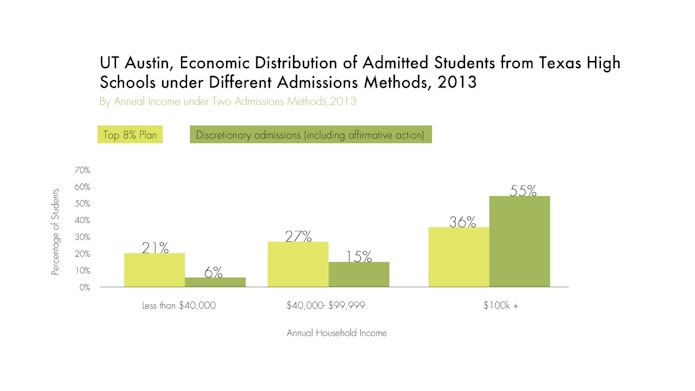

The Supreme Court’s Fisher opinion noted that in absolute terms, in 2004, the race-neutral programs achieved slightly more racial diversity (4.5 percent African American and 16.9 percent Hispanic) than had been achieved using race in 1996 (4.1 percent African American and 14.5 percent Hispanic).49 The Top 10 Percent plan also increases socioeconomic diversity.

Roughly three-quarters of students are admitted through the plan, and one-quarter through discretionary admissions (which, after 2004, began to include race again). As Tienda points out, in 2011, 9 percent of students admitted under the plan came from families making less than $20,000 a year, compared with 3 percent of those admitted under discretionary admissions. At the other end of the spectrum, just 13 percent of those admitted under the plan were from families making more than $200,000 a year, compared with 29 percent of those admitted through the discretionary program.50

Moreover, Tienda notes, despite initial skepticism about admitting students irrespective of SAT and ACT scores, the Top 10 Percent students have performed well. In a study conducted with Sunny Niu, Tienda found that between 1999 and 2003, minority students admitted through the plan “consistently perform as well or better” than white students ranked at or below the third decline.51

Still, Tienda expresses deep concerns that the Top 10 Percent plan has not kept up with changing demographics in Texas. Simply meeting the 1996 proportions for black and Hispanic students is insufficient in a state where the nonwhite population among Texas high school graduates is growing by leaps and bounds.52 Although as a legal matter, the U.S. Supreme Court has rejected the idea that universities may employ race to achieve state-wide proportional representation, as a policy matter, surely the large gap between minority high school proportions and representation at a flagship university should be deeply troubling. One step in particular that Tienda recommends is better programs to ensure that minority students who qualify for the Top 10 Percent plan actually apply and enroll at University of Texas at Austin. Tienda reports that while half of Asian and more than one-third of white Top 10 Percent graduates enroll at one of the public flagships, “only one-in-four similarly qualified black and Hispanic students” do.53

While Texas was coming up with an array of alternatives, California was busy doing the same in response to a 1996 referendum banning racial preferences at public institutions. As Richard Sander of UCLA Law School explains in Chapter 8, California took a number of steps both at UCLA Law School (where Sander devised an economic affirmative action plan) and system-wide to promote diversity without using race per se. California adopted a modified percentage plan like Texas, but what was particularly striking, Sander writes, is the “jump in the interest of administrators and many faculty members in the use of socioeconomic status (SES) metrics as an alternative to race in pursuing campus diversity.”54

At UCLA Law School, administrators developed a set of sophisticated and quantitative measures of socioeconomic disadvantage at the family level (parental education, income, and net worth) as well as the neighborhood level (percentage of families headed by single parent households, proportion of families on public assistance, and percentage who had not graduated from high school). This more detailed rendering of socioeconomic status was meant to get at a wide array of disadvantages, some of which are known to particularly affect black and Hispanic students (who would therefore disproportionately benefit from inclusion in the metric). While income correlates modestly with race, the broader measures of socioeconomic disadvantage essentially doubled the correlation.55

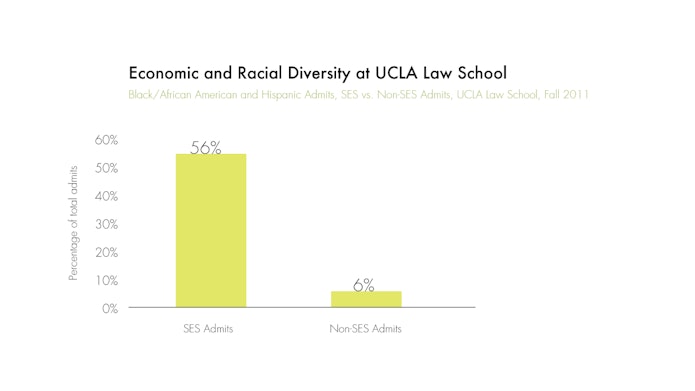

Compared to the racial preferences employed in the past, the socioeconomic preferences were broader (applying to more students) but more shallow (providing a smaller admissions boost).

How effective was the program in promoting racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic diversity as well as student outcomes? Sander reports substantial gains in socioeconomic diversity, as the proportion of students who were the first in their families to attend college roughly tripled.56 Black and Hispanic admissions fell substantially, however, a sobering development that Sander attributes in part to the tilted playing field UCLA faced in recruiting underrepresented minorities. Virtually all of UCLA’s competitors could continue to use racial preferences, and often provided race-based scholarships as well so they could scoop up talented minority students who might otherwise attend UCLA.57 Still, in a recent year (2011), the socioeconomic program continued to benefit minority students disproportionately. African Americans were 11.3 times as likely to be admitted under the socioeconomic program as all other programs, and Hispanics were 2.3 times as likely to be admitted.58 And after adoption of the socioeconomic program, with its smaller, broader preferences, UCLA’s California bar exam passage rate rose to an all-time high.59

At the undergraduate level, a variety of race-neutral measures were put in place on different University of California campuses. Some elite campuses saw declines in minority admissions, but Sander reports that on the issue of bottom-line concern—total graduation of minority students—the number of bachelor’s degrees awarded to African Americans in the California system actually rose after the affirmative action ban and the adoption of race-neutral strategies, from an average of 802 in the cohorts that entered in last years of racial preferences to 926 more recently. Sander says degrees awarded to Hispanics also rose.60

After banning racial preferences in California, opponents of affirmative action moved to another “blue” coastal state, Washington, and succeeded in passing a similar initiative in 1998. Richard McCormick was president of the University of Washington at the time and spoke out strongly against the referendum. He bemoaned the fact that the proportion of black, Hispanic, and Native American students at the University dropped in the first year after implementation of the ban, from one in eleven to one in eighteen.61

But, as McCormick notes in Chapter 9, he and others began to craft new approaches to create diversity. “Key constituencies within the UW community—including the Board of Regents, the university administration, faculty leaders, and student leaders—came together to design a wide range of measure for promoting student diversity and a plan for ensuring their success.”62 New efforts of recruitment at predominantly minority high schools—including a “student ambassador” program— were launched. Financial aid was expanded, and the university began considering such factors as “personal adversity” and “economic disadvantage.”63 The good news, McCormick writes, is that “together these efforts were successful.” Within five years of the initial drop in minority enrollment, “the racial and ethnic diversity of the UW’s first-year class had returned to its pre-1999 levels,” when race was still considered in admissions. Moreover, McCormick notes, “the economic diversity of the UW’s undergraduate student body also increased—as indicated by the university’s growing number of federal Pell grant recipients.”64

In fact, when McCormick later moved to lead Rutgers University in New Jersey, he took some of the lessons from the University of Washington with him. Rutgers enjoyed racial diversity among its students, but its minority students were “mostly suburban,” and the university failed to reach urban minority high schools. In 2008, Rutgers adopted a race-neutral Future Scholars Program that was aimed at cities such as Newark, New Brunswick, and Camden, with almost all of the beneficiaries being low-income African American or Hispanic students.65

Meanwhile, in 2000, the University of Georgia, faced with an Eleventh Circuit ruling striking down the use of race in admissions, began shifting emphasis to a number of race-neutral strategies. As Nancy McDuff, associate vice president for admissions and enrollment management at the University of Georgia, explains in Chapter 10 (coauthored by Century’s Halley Potter), the university added do admissions a number of socioeconomic consideration (such as parental education and high school environment). The university also began admitting the valedictorian and salutatorian from every high school class and dropped legacy admissions, which disproportionately benefitted white and wealthy students. Although the latter move was opposed by alumni, the university “has not encountered noticeable fundraising challenges as a result of the change,” McDuff and Potter write.66 The university also stepped up recruitment efforts, particularly at high schools with high percentages of low-income students, and has strengthened partnerships with K-12 schools to boost readiness of underrepresented students.

Minority enrollment initially dropped after the ban on using race in admission, but it has since moved upward and the retention of African American students is even higher than the University of Georgia’s overall average. Whereas it used to be called the “University of North Atlanta,” because of the large numbers of white upper-middle class students from that area, today, the campus has become more diverse socioeconomically and geographically.67 Overall, McDuff and Potter write, “the years since 2000 have shown the university moving in the right direction, toward increased racial, ethnic, socioeconomic, linguistic, and geographic diversity on campus.”68

States such as Texas, California, Washington, and Georgia have been able use race neutral strategies to boost racial diversity—in many cases, matching or succeeding representation of blacks and Hispanics achieved using race in the past—but could they do even better given the right tools? That is the question we take up in Part IV of the volume, drawing upon an array of the country’s top researchers on promising strategies.

Here we return to the distinction between law and policy. In narrow legal terms, the success of states where race considerations were banned by referendum in creating “sufficient” diversity through race-neutral strategies is likely to render the continued use of race legally vulnerable in other states. As a recent article in the Harvard Law Review notes, as more universities pursue successful race-neutral strategies, “the bar will continue to rise on what it means to demonstrate that ‘no workable race-neutral alternatives’ are available. A university will have increasing difficulty claiming that no workable race-neutral alternatives exist if peer institutions have developed and successfully demonstrated such alternatives.”69 But what is considered “sufficient” by the Supreme Court as a legal matter might be very different from what we desire as a matter of public policy.

As Marta Tienda and others point out, as a policy matter, we should not be satisfied, given growing diversity among high school graduates, with simply replicating past levels of university diversity. Many would like race-neutral strategies to be even more effective than they are today so as to better reach minority proportions in the general population. What does research suggest could improve these programs?

Research on Promising Race-Neutral Strategies

The research in Part IV elucidates three strategy buckets:

- better outreach and recruitment of low-income and minority students;

- admissions plans that employ variations on Texas’s Top 10 Percent plan by reducing the reliance on test scores and/or emphasizing geographic diversity; and

- affirmative action in admissions that benefits economically disadvantaged students of all races.

Perhaps the least controversial way to boost racial, ethnic, and economic diversity—involving no preferences—is to get talented minority and disadvantaged students to apply to selective colleges in greater numbers. One major reason that low-income and minority students are underrepresented at selective colleges is that such students disproportionately “undermatch,” failing to apply to selective schools at which they would likely be admitted and succeed, instead attending less selective institutions or none at all.

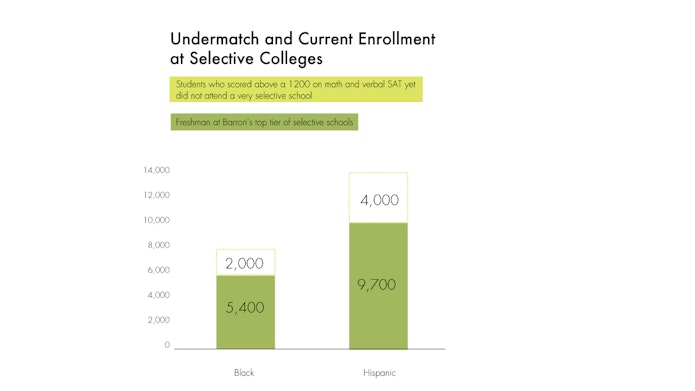

As Alexandria Walton Radford of RTI International and Jessica Howell of the College Board note in Chapter 11, “undermatch is pervasive, especially among low-income, underrepresented minorities, and first-generation college-goers.”70 Looking at national research, as well as research from North Carolina and Chicago, Radford and Howell note that 43 percent of students who are academically qualified to gain admission to a very selective college undermatch, and that Hispanics and African Americans are especially likely to undermatch.71 In raw numbers, that translates into 4,000 Hispanic and 2,000 African American students who score above 1200 on the math and verbal portions of the SAT yet do not attend a very selective school.72 Caroline Hoxby of Stanford and Christopher Avery of Harvard, likewise, find considerable undermatching among low-income high achievers, an important subset of whom are black and Hispanic.73 Hoxby and Avery find that 35,000 low-income students are very high achieving—placing them in the top 4% of high school students nationally—and that only one-third apply to one of the country’s 238 most selective colleges. Of those low-income high-achieving students who score above 1300 on the SAT or the ACT equivalent, roughly 2,000 are African American and 2,700 Hispanic. To put these numbers in context, at Barron’s top tier of selective schools (about 80 institutions), there are currently only 5,400 black freshmen and 9,700 Hispanic freshman from all economic backgrounds. This research suggests there is enormous potential to increase socioeconomic and racial diversity without in any way sacrificing academic quality by simply getting more underrepresented minority and low-income students to apply, and, when admitted, enroll.

Why do these students undermatch? Radford’s important new research among valedictorians finds that lack of understanding about need-based financial aid and poor guidance counseling are contributing factors to undermatching.74 The good news is that this diagnosis suggests some relatively straight forward and inexpensive interventions may be possible. In an experiment Hoxby conducted with the University of Virginia’s Sarah Turner’s, a $6 per application intervention providing more information about colleges and financial aid was found to significantly raise application rates.75 As Radford and Howell note, the College Board is now taking steps to scale the Hoxby/Turner intervention through its Expanding College Opportunities program for high-achieving, low-income students who took the PSAT or SAT.76 The authors conclude, “As institutions of higher education seek new ways to increase socioeconomic and racial diversity, addressing the issue of undermatch may prove to be a fruitful avenue for reaching those goals—and, more generally, for helping all students to fulfill their potential.”77

Of course, getting minority and low-income students to apply is a critical first step; but then universities need to admit them, so the rest of the chapters in this section address questions of university admission.

Admissions plans that seek to more broadly apply lessons from the Texas Top 10 Percent plan are the subject of Chapters 12 and 13. The Texas plan worked to produce racial and ethnic diversity for two distinct reasons. First, it enhanced geographic diversity, and leveraged the unfortunate reality of residential and high school segregation by race and class for a positive purpose, to promote integration in higher education. Second, the Top 10 Percent plan focused exclusively on class rank by high school GPA, effectively eliminating reliance on SAT and ACT test scores, which disproportionately screen out black and Latino candidates. But how would elements of the Top 10 Percent plan apply to public or private colleges that have a national, rather than state-wide pool of applicants?

In Chapter 12, Danielle Allen of the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton proposes using geographic diversity and zip codes as a way of promoting racial, ethnic, and economic diversity. “Geographic-based structures for seeking talent are tried and true,” she writes, noting that universities pride themselves on having students from all states, and National Merit and Rhodes scholars are chosen on the basis of regional competitions.78 She suggests that universities select students at least in part based on academic accomplishments within their ZIP codes, or possibly census tracts. Given the well-documented existence of economic, racial, ethnic, and ideological segregation by ZIP code, this method of admission would likely yield diversity on all of those fronts, she contends.79 “At selective colleges and universities a stronger orientation toward geographic diversity could well support diversification of student populations by ethnicity, thereby permitting us to slip free of the contested terrain of affirmative action.”80 The enhanced geographic diversity could be a bonus, Allen writes, noting that Athenian democracy thrived by bringing together citizens from urban, rural, and coastal areas to generate knowledge and make decisions.81

In Chapter 13, John Brittain, of the University of the District of Columbia Law School and former chief counsel of the Lawyers Committee for Civil Rights, and his coauthor Benjamin Landy, an editor at MSNBC, suggest applying more widely the other aspect of the Texas Top 10 Percent plan: reduced reliance on standardized tests.

Brittain and Landy note that standardized tests like the SAT were born with egalitarian intentions, to help colleges “identify talented students from unknown schools and unspectacular backgrounds,” thereby replacing “the old boys club” that dominated selective colleges with a meritocracy.82 But in practice, the SAT and ACT have come to exclude large numbers of low-income and minority students, who score lower on average on tests which carry with them very high stakes. “A good score can open the doors to some of the world’s most elite institutions, wealthy alumni networks and prestigious job opportunities,” Brittain and Landy say. “A low score threatens to close those doors forever.”83

The authors note that high school grades are a better predictor of college performance than SAT scores, and have a much less discriminatory impact against minority students. Yet reliance on test scores by universities admissions officers has actually increased in recent years. In part, the authors blame U.S. News & World Report college rankings, which favor schools with high student test scores. In addition, civil rights groups, Brittain and Landy suggest, have made a “Faustian bargain” with universities in which civil rights advocates have not challenged the racially discriminatory impact of the SAT so long as universities provide affirmative action. “Historically,” the authors write, “there appears to have been a ‘gentleman’s agreement’ between civil rights groups and colleges,” which “has no parallel in the employment context, where there have been numerous legal challenges to the discriminatory impact of testing.”84

If affirmative action is further constrained, the authors suggest the reticence to litigate the SAT may change. Even in the absence of litigation, the authors recommend that universities reduce their reliance on tests like the SAT. Despite variation in grading standards among high schools, Brittain and Landy contend that a heavier reliance on high school grades would not result in the admission of unqualified students. Nearly 850 colleges and universities have already gone “test-optional,” Brittain and Landy note, including leading institutions such as Bowdoin, Smith, Bates, and Wake Forest. At Wake Forest, retention rates remain very high under the test-optional approach, and diversity has blossomed. Both the proportion of students eligible for Pell grants and the percentage of blacks and Hispanics increased significantly.85 The authors conclude that in the coming years, reducing the over-reliance on test scores could be an important avenue to increase racial, ethnic, and economic diversity and “would make our college admissions system fairer for everyone.”86

The third bucket of race-neutral strategies involves policies providing a leg up in admissions to economically disadvantaged students of all races. The very early research on the issue suggested that preferences for low-income students would not produce much racial and ethnic diversity because low-income white students outnumber low-income black and Hispanic students, particularly among high-achievers.87 But more recent research—which defines socioeconomic status in more nuanced ways—suggests that this strategy can produce considerable racial and ethnic diversity.

In Chapter 14, Matthew Gaertner, a research scientist at the Center for College and Career Success at Pearson, describes the results of an experiment in class-based affirmative action at the University of Colorado at Boulder. In 2008, the university, fearing that a state anti-affirmative action referendum banning considerations of race would pass, turned to Gaertner to help devise a race-neutral alternative that provided a leg up to socioeconomically disadvantaged students of all races. In the event, the referendum narrowly failed, but the university developed a wealth of information about class-based efforts, and it ended up implementing a version of the policy, while continuing to use race as a factor in admissions.

Based on national research, the University of Colorado at Boulder devised an index of socioeconomic disadvantage that looked at a number of factors, including: “the applicant’s native language, single-parent status, parents’ education level, family income level, the number of dependents in the family, whether the applicant attended a rural high school, the percentage of students from the applicant’s high school eligible for free or reducedprice lunch (FRL), the school-wide student-to-teacher ratio, and the size of the twelfth-grade class.”88 Under the program, socioeconomically disadvantaged students received a preference in admissions that was larger than what black and Hispanic students had been provided in the past.

When simulations were run, socioeconomic diversity increased, as expected, but surprisingly, the acceptance rates of underrepresented minority applicants also increased, from 56 percent under race-based admissions to 65 percent under class-based admissions. The size of the preference seems to explain the result, Gaertner suggests.89

But did the sizable socioeconomic boost create a new academic mismatch problem by admitting too many unprepared students? Gartner found that the class-based admits were less likely to graduate in six years (53 percent versus 66 percent for the general population), but notes that this is in line with the historical performance of underrepresented minorities at Colorado, who have six-year graduation rates averaging 55 percent.90 The university has not seen the lower graduation rates of disadvantaged students as inevitable or as reason to discontinue the program but rather has moved to beef up academic supports for such students.91

If Colorado—a moderately selective school—was able to devise a class-based affirmative action that boosted racial diversity, how would such a program work nationally at the most selective colleges and universities? In Chapter 15, Anthony Carnevale, Stephen Rose, and Jeff Strohl of Georgetown University take a groundbreaking look at how socioeconomic affirmative action programs, percentage plans, or a combination of the two, could work at the nation’s most selective 193 institutions. What would the socioeconomic, racial, and ethnic outcomes of various admissions strategies be? And what level of academic quality (measured by mean SAT score) would various strategies produce?

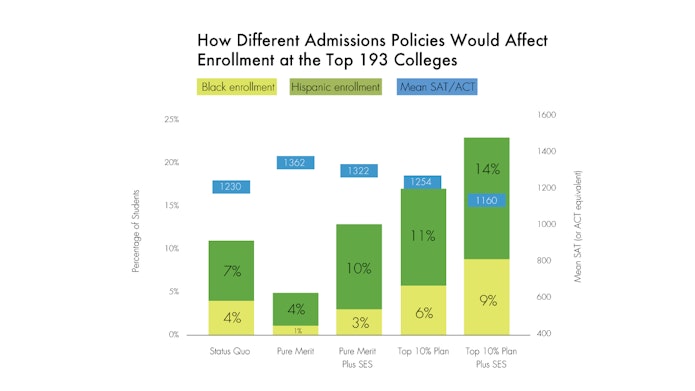

Currently, under a system of race-based affirmative action, legacy preferences, athletic preference, and the like, African Americans represent 4 percent of students at the most selective 193 colleges and universities, and Hispanics represent 7 percent, for a combined 11 percent representation, according to the authors. The bottom socioeconomic half has a 14 percent representation. If we moved to a system of admissions strictly based on test scores, the representation of the bottom socioeconomic half would inch up slightly, to 15 percent, but racial and ethnic diversity would suffer dramatically. The proportion of African Americans would drop to just 1 percent and Hispanics to 4 percent, for a combined representation of 5 percent. This would clearly represent an unacceptable step backward for racial and ethnic diversity.

But would race-neutral alternatives like economic affirmative action and percentage plans see a similar fall in racial and ethnic diversity? No, the authors find. To the contrary, combined black and Hispanic representation actually rise under both scenarios.

The authors begin by examining what would happen if students were admitted based on test scores that also factored in socioeconomic disadvantages overcome.92 Applying a variety of socioeconomic obstacles (for example, family factors such as parental education, income, and savings—a proxy for wealth—and neighborhood factors such as school poverty concentrations), the authors find that the combined underrepresented minority population would rise from 5 percent (under pure merit admissions) and 11 percent (under the current system of race-based affirmative action, legacy preferences, and so on) to 13 percent. Hispanics would benefit (moving from 7 percent to 10 percent) and blacks would lose some representation (from 4 percent to 3 percent). The representation of the bottom socioeconomic half would rise dramatically, from 14 percent today to 46 percent. Mean SAT scores would rise from 1230 today to 1322 under socioeconomic affirmative action.

Under a merit-based simulation, in which the top 10 percent of test takers in every high school are among the pool admitted, African Americans and Hispanics both do better than under the status quo of race-based affirmative action, legacy preference, and the like. African American representation goes from 4 percent today to 6 percent, and Hispanic representation from 7 percent today to 11 percent. The bottom socioeconomic half would jump from 14 percent today to 31 percent. Mean SAT scores rise slightly, from 1230 to 1254.

Taken separately, both the socioeconomic and percentage plans are able to boost combined black and Hispanic representation and socioeconomic diversity, and raise test scores. Merging the two approaches—a top 10 percent plan with a socioeconomic affirmative action plan—provides a yet bigger diversity boost, to 9 percent African American and 14 percent Hispanic, and 53 percent representation for the bottom economic half. But mean SAT scores would fall to 1160, so predicted graduation rates would fall as well.93

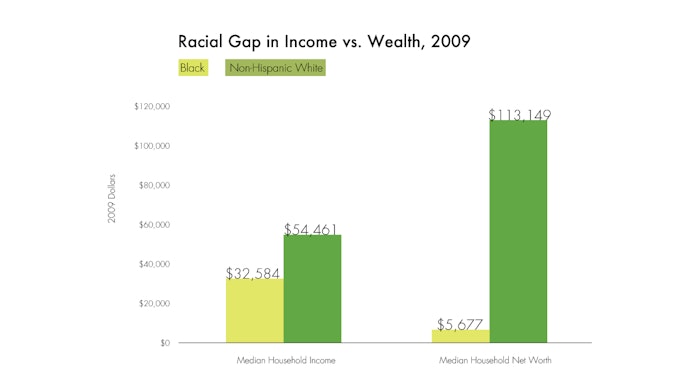

Could socioeconomic affirmative action be refined further to improve its fairness and its racial dividend beyond the levels outlined in Carnevale, Rose, and Strohl’s research? In the past, Carnevale and Strohl have noted that their simulations use a proxy for wealth (savings) that is not ideal.94 In Chapter 16, Dalton Conley of New York University makes a powerful case that using wealth and parental education would provide an eminently fair basis for admissions preferences while also producing substantial racial and ethnic diversity.

Using the Panel Study of Income Dynamics, the world’s longest running longitudinal survey of families, Conley is able to measure, through regression analysis, which factors most powerfully predict college completion. What emerged were not race or income but rather parental education and wealth.95 Having educated parents (of whatever race) provides significant educational advantages in life. And wealth matters more than income, Conley notes, because “the structuring of educational opportunity does not happen on a paycheck to paycheck basis. Rather educational advantages are acquired through major capital investments and decisions,” such as purchasing a home in a neighborhood with good public schools.96

If using wealth is the fair and right thing to do, it will also indirectly promote racial diversity far more powerfully than income, Conley notes, because it is a better proxy for racial disadvantage. While blacks typically have 70 percent of the income of whites, they have just 10 percent of the wealth. The gap is much wider, Conley suggests, probably because of ongoing racial discrimination in the housing market, and also because wealth, which is handed down through generations, “does a better job than any other measure of socioeconomic background” of capturing “the legacy of historical inequalities of opportunity.”97

Would the class-based affirmative action programs discussed by Gaertner, Carnevale, Rose, Strohl, and Conley be subject to the same legal and political concerns that racial affirmative action has faced? That seems highly unlikely. Whereas the use of race is subject to “strict scrutiny,” classifying individuals by socioeconomic status must only meet the more relaxed “rational basis” legal test.98 Moreover, even the most conservative U.S. Supreme Court justices, Antonin Scalia and Clarence Thomas, have explicitly endorsed class-based affirmative action programs.99 And polling suggests that economic affirmative action programs enjoy support by a two-to-one margin.100

Public Policy Proposals

As a practical matter, if universities are going to move to new race-neutral strategies, they will need support from the government and from philanthropic foundations. There is a reason that in the past universities have employed racial criterion to achieve diversity directly, often by recruiting well-off students of color. It is cheaper and easier. In Part V of the volume, two chapters lay out suggestions for how foundations and the government can ease the path for universities.

In chapter 17, Richard Sander calls for the government or foundations to support the creation of better data sets and software to enable universities to more easily identify and connect with students who will promote socioeconomic, racial, and ethnic diversity and are academically prepared to succeed. A national educational organization, Sander says, could create the database and software to make it possible for admissions officers to specify a desired academic threshold coupled with socioeconomic profiles that would generate a pool of admissible students.

Sander also takes on the critical issue of financing. Boosting application rates and addressing admissions gets us only two-thirds of the way to creating successful race-neutral alternatives. Also required are public policies that provide sufficient financial aid and support to students once in college.

Increasingly, universities are diverting scarce financial aid resources to non-need merit aid, Sander notes. This disturbing trend may have been inadvertently accelerated by a Justice Department anti-trust investigation that resulted in a 1991 consent decree preventing colleges from cooperating on financial aid decisions. The 1991 settlement needs revisiting, says Sander, to allow universities to take collective action to promote need-based aid. Moreover, to encourage financial aid based on genuine need, Sander advocates the creation of a federal “need-based-aid incentive program.”

In Chapter 18, Catharine Hill, the president of Vassar College (and an economist who has spent many years researching higher education), suggests three sets of public policies that would support universities in adopting race-neutral social mobility programs.

Hill begins by noting that socioeconomic stratification in higher education is the direct result of increasing economic inequality in the larger society. The increase in wealth among high-income families puts pressure on universities to increase services; yet the increase in poverty rates and stagnating wages among working-class families on the other end puts pressure on universities to increase financial aid. Unsurprisingly, universities tend to listen to the needs of the first group more than the second and thereby reflect, rather than combat, growing inequality. She suggests the adoption of an array of policies to reduce economic inequality, from increasing the minimum wage and investing more in education to increasing taxes on wealthier Americans. She writes, “the higher education sector, given the current incentives that institutions face, cannot address rising income inequality in America on its own.”101

Second, government policies should provide strong incentives for colleges to promote socioeconomic diversity. Currently, all the incentives point against recruiting more low-income students of all races because ranking systems like U.S. News & World Report give no credit for institutions that provide greater access. To the contrary, providing financial aid for low-income students “diverts” funds from things that will increase an institution’s rankings (merit aid, higher faculty salaries, bigger libraries, and so on). To counter this, federal and state monies should flow to universities that provide greater access (a principle that the Obama administration rating system seems to endorse). Like Sander, Hill recommends modifying anti-trust policies that prevent universities from cooperating to focus aid on need rather than non-need merit aid. And she would require universities to disclose both their net prices and their share of students by income quartile each year. “Reporting these data,” she notes, would “put pressure on schools to live up to their mission statements.”102

Third, the government should adopt policies that encourage lowincome students to attend more selective colleges. Loans should be contingent on income, which would make the risk of taking on debt less daunting, particularly for students from low-income families.103 And high-ability, low-income students should receive better information about the benefits of attending selective colleges and the financial aid that might be available. At the same time, Hill says, “it is important to combine such efforts with greater incentives for schools to allocate resources to financial aid. Otherwise, increased applications will not translate into greater low-income access at these schools.”104

Conclusion

As the chapters in this volume make clear, the future of affirmative action is likely to be quite different than the policies we have come to know over the past half century. The experiences in several states where racial considerations have been banned suggest that it is possible, with creativity and commitment, to construct new paths to racial, ethnic, and economic diversity. The good news, then, is that the constraints imposed by the Supreme Court in Fisher v. University of Texas do not have to mean the end of affirmative action, but rather could spawn the creation of new approaches.

This is not to suggest that the path ahead is easy. Universities will need to experiment with a number of approaches, learning from the benefits and the pitfalls of the strategies outlined in this volume. New paths to diversity may be more expensive than old ones. But in states where race has been discontinued as a factor in admissions, political forces have rallied around a variety of approaches—including substantial increases in financial aid—to make race-neutral strategies work.105

Even conservative opponents of affirmative action recognize that while Americans may not like counting race in college admissions, they do not want to see higher education re-segregate, either. Liberals, too, often are more comfortable advocating for race-neutral programs that generate broad public support. The Obama administration’s January 2014 White House conference designed to boost the representation of low-income students of all races, is a recent example.106 Fisher v. University of Texas presents new challenges for universities, but it could also lead to an even broader and richer conception of diversity based fully on race, ethnicity and socioeconomic status.

Notes

- Fisher v. University of Texas, 113 S.Ct. 2411, at 2420 (2013).

- Fisher v. University of Texas, 113 S.Ct. 2411, at 2420 (2013).

- Regents of the University of California v. Bakke, 438 U.S. 265, 287 (1978).

- See, for example, Thomas Kane and James E. Ryan, “Why ‘Fisher’ Means More Work for Colleges,” Chronicle of Higher Education, July 29, 2013 (“the court’s emphasis on the exploration of race-neutral alternatives represents a subtle but potentially significant shift”); Note, “Fisher v. University of Texas at Austin,” Harvard Law Review 127, no. 1 (2013), at 258, (“this case may prove to be the inflection point in the overt use of race in university admissions”); at 262 (“The resulting framework — in which courts apply a more stringent form of strict scrutiny to public-university affirmative action programs — is likely to place additional pressure on universities to develop, test, and implement new race- neutral alternatives”); and 263 (“there is a doctrinal shift here, one squarely in tension with the Fisher majority’s statement that Bakke, Grutter and Gratz were ‘take[n] . . . as given for purposes of deciding this case'”).

- William G. Bowen and Derek Bok, The Shape of the River: Long-Term Consequences of Considering Race in College and University Admissions (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1998), 341, Table B.2.

- William G. Bowen, Martin A. Kurzweil, and Eugene M. Tobin, Equity and Excellence in American Higher Education (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2005), 105, Table 5.1.

- Beckie Supiano, “7 in 10 Undergraduates Get Financial Aid, New Data From a Major Federal Study Show,” Chronicle of Higher Education, August 20, 2013.

- Washington Monthly, September/October 2013, 60-61.

- Anthony P. Carnevale and Jeff Strohl, Separate and Unequal: How Higher Education Reinforces the Intergenerational Reproduction of White Racial Privilege (Washington, D.C.: Georgetown Center on Education and the Workforce, 2013), 12.

- Catharine Hill, “Improving Socioeconomic Diversity at Top Colleges and Universities,” Huffington Post, April 5, 2013. See also Beckie Supiano and Andrea Fuller, “Elite Colleges Fail to Gain More Students on Pell Grants,” Chronicle of Higher Education, March 27, 2011. (In 2008-09, 15 percent of students at the wealthiest fifty colleges received Pell Grants, a figure similar to 2004-05.)

- The Future of Affirmative Action, Chapter 2, 28.

- The Future of Affirmative Action, Chapter 2, 30.

- The Future of Affirmative Action, Chapter 2, 28.

- The Future of Affirmative Action, Chapter 2, 30.

- The Future of Affirmative Action, Chapter 2, 30.

- Thomas R. Dye, Who’s Running America? (Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall, 2002), 148.

- Richard D. Kahlenberg, “Who Benefits Most From Attending Top Colleges?” Chronicle of Higher Education, March 10, 2011.

- “Feeling the Heat: the 2013 Survey of College and University Admissions Directors,” Inside Higher Ed, September 18, 2013.

- The Future of Affirmative Action, Chapter 4, 45.

- The Future of Affirmative Action, Chapter 5, 59.

- The Future of Affirmative Action, Chapter 4, 240, n. 17.

- Grutter v. Bollinger, 539 U.S.306, at 394.

- The Future of Affirmative Action, Chapter 5, 59.

- Fisher v. University of Texas, 113 S.Ct. 2411, at 2421.

- The Future of Affirmative Action, Chapter 5, 63.

- The Future of Affirmative Action, Chapter 4, 49.

- The Future of Affirmative Action, Chapter 5, 58.

- The Future of Affirmative Action, Chapter 4, 51 (calling this “perhaps the most important passage in Fisher.”)

- The Future of Affirmative Action, Chapter 4, 51.

- The Future of Affirmative Action, Chapter 5, 69.

- The Future of Affirmative Action, Chapter 4, 53-54.

- Grutter v. Bollinger, 539 U.S. 306, at 330.

- Kane and Ryan, “Why ‘Fisher’ Means More Work for Colleges,” Chronicle of Higher Education, July 29, 2013.

- The Future of Affirmative Action, Chapter 4, 47.

- See citations in Richard D. Kahlenberg, “Why Liberals Should Embrace Fisher v. Texas,” The Century Foundation, August 2, 2013.

- Fisher v. University of Texas, 113 S.Ct. 2411, at 2420 (2013).

- The Future of Affirmative Action, Chapter 4, 241, n. 29.

- The Future of Affirmative Action, Chapter 4, 52.

- The Future of Affirmative Action, Chapter 4, 51.

- The Future of Affirmative Action, Chapter 4, 50.

- The Future of Affirmative Action, Chapter 5, 72.

- Kane and Ryan, “Why ‘Fisher’ Means More Work for Colleges,” Chronicle of Higher Education, July 29, 2013.

- The Future of Affirmative Action, Chapter 6, 75-76.

- Richard D. Kahlenberg, “A Fresh Chance to Reign in Racial Preferences,” Wall Street Journal, October 13, 2013.

- The Future of Affirmative Action, Chapter 6, 90.

- At an eleventh institution, the University of New Hampshire, there is no evidence that race-neutral alternatives were put in place.

- Sigal Alon, “Insights from Israel’s Class-Based Affirmative Action,” Contexts, Fall 2013.

- The Future of Affirmative Action, Chapter 7, 92.

- Fisher v. University of Texas, 113 S.Ct. 2411, at 2416 (2013).

- The Future of Affirmative Action, Chapter 7, 95.

- The Future of Affirmative Action, Chapter 7, 97.

- The Future of Affirmative Action, Chapter 7, 93.

- The Future of Affirmative Action, Chapter 7, 94.

- The Future of Affirmative Action, Chapter 8, 99.

- The Future of Affirmative Action, Chapter 8, 104.

- The Future of Affirmative Action, Chapter 8, 105.

- The Future of Affirmative Action, Chapter 8, 106.

- Richard D. Kahlenberg and Halley Potter, “A Better Affirmative Action: State Universities that Created Alternatives to Racial Preferences,” The Century Foundation, October 2012, 13.

- The Future of Affirmative Action, Chapter 8, 107.

- The Future of Affirmative Action, Chapter 8, 102-03.

- The Future of Affirmative Action, Chapter 9, 117.

- The Future of Affirmative Action, Chapter 9, 117.

- The Future of Affirmative Action, Chapter 9, 117-18; Richard D. Kahlenberg and Halley Potter, “A Better Affirmative Action: State Universities that Created Alternatives to Racial Preferences,” The Century Foundation, October 2012, 40.

- The Future of Affirmative Action, Chapter 9, 118.

- The Future of Affirmative Action, Chapter 9, 119.

- The Future of Affirmative Action, Chapter 10, 126.

- The Future of Affirmative Action, Chapter 10, 129.

- The Future of Affirmative Action, Chapter 10, 123.

- Note, “Fisher v. University of Texas at Austin,” 266-67.

- The Future of Affirmative Action, Chapter 11, 134.

- The Future of Affirmative Action, Chapter 11, 134.

- The Future of Affirmative Action, Chapter 11, 134.

- Caroline M. Hoxby and Christopher Avery, “The Missing ‘One-Offs’: The Hidden Supply of High-Achieving, Low Income Students,” NBER Working Paper no. 18586, December 2012.

- The Future of Affirmative Action, Chapter 11, 138-39.

- Richard V. Reeves and Kimberly Howard, “The Glass Floor: Education, Downward Mobility, and Opportunity Hoarding,” Brookings, November 2013, 9, citing Caroline Hoxby and Sarah Turner, “Expanding College Opportunities for High-Achieving, Low-Income Students,” Stanford Institute for Economic Policy Research Discussion Paper, 2013.

- The Future of Affirmative Action, Chapter 11, 143.

- The Future of Affirmative Action, Chapter 11, 144.

- The Future of Affirmative Action, Chapter 12, 147.

- The Future of Affirmative Action, Chapter 12, 155-56.

- The Future of Affirmative Action, Chapter 12, 156.

- The Future of Affirmative Action, Chapter 12, 153.

- The Future of Affirmative Action, Chapter 13, 162.

- The Future of Affirmative Action, Chapter 13, 160.

- The Future of Affirmative Action, Chapter 13, 161-62.

- he Future of Affirmative Action, Chapter 13, 173.

- The Future of Affirmative Action, Chapter 13, 174.

- Thomas J. Kane, “Racial and Ethnic Preferences in College Admissions,” in The Black-White Test Score Gap, ed. Christopher Jencks and Meredith Phillips (Washington, DC: Brookings Institution Press, 1998), 448-51.

- The Future of Affirmative Action, Chapter 14, 177.

- The Future of Affirmative Action, Chapter 14, 181, Table 14.3.

- The Future of Affirmative Action, Chapter 14, 183-84.

- The Future of Affirmative Action, Chapter 14, 185.

- For a table of disadvantages, see Anthony P. Carnevale and Jeff Strohl, “How Increasing College Access Is Increasing Inequality, and What to Do about It,” in Rewarding Strivers: Helping Low-Income Students Succeed in College, ed. Richard D. Kahlenberg (New York: Century Foundation Press, 2010), 170, Table 3.7.

- The Future of Affirmative Action, Chapter 15, 189, Tables 15.1 and 15.2.

- Anthony P. Carnevale and Jeff Strohl, “How Increasing College Access Is Increasing Inequality, and What to Do about It,” in Rewarding Strivers: Helping Low-Income Students Succeed in College, ed. Richard D. Kahlenberg (New York: Century Foundation Press, 2010), 165.

- The Future of Affirmative Action, Chapter 16, 206.

- The Future of Affirmative Action, Chapter 16, 207

- The Future of Affirmative Action, Chapter 16, 208-209.

- See, for example, Gratz v. Bollinger, 539 U.S. 244, 270 (2003) (all racial classifications are subject to strict scrutiny) and James v. Valteirra, 402 U.S. 137, 141 (1971) (wealth classifications are not subject to strict scrutiny).

- See, for example, Antonin Scalia, “Commentary: The Disease as Cure,” Washington University Law Quarterly (1979): 153-54; and U.S. Congress, Senate Judiciary Committee, Nomination of Clarence Thomas to Be Associate Justice of the United States Supreme Court, October 1, 1991, 102d Cong., 1st sess., 358-60.

- Los Angeles Times poll (conducted January 30 to February 2, 2003); Newsweek poll (conducted January 16-17, 2003); and James M. Glaser and Timothy J. Ryan, “How ‘Race Neutrality’ Can Save Affirmative Action,” Washington Monthly, November/December 2013, 11-12 (non-Hispanic white California voters more open to preferences for the poor than for black and Latino students).

- The Future of Affirmative Action, Chapter 18, 228.

- The Future of Affirmative Action, Chapter 18, 232.

- The Future of Affirmative Action, Chapter 18, 233.

- The Future of Affirmative Action, Chapter 18, 233-34.

- Kahlenberg and Potter, “A Better Affirmative Action,” 11.

- Kelly Field, “White House Summit Gathers College Leaders Who Pledged to Expand Access,” Chronicle of Higher Education, January 15, 2014; and Richard D. Kahlenberg, “Why the White House Summit on Low-Income Students Matters,” Chronicle of Higher Education, January 17, 2014.