Students who enter career training programs are making an investment in their future. They are also taking a bit of a gamble. Deciding to spend on a college education is a large financial commitment, one that often involves going into debt. Taking that risk is accompanied by many questions: If I take out student debt to pay for education, will I make the income I need to pay it off? If I invest my time and energy to complete a postsecondary program, will I be better off than if I never pursued college at all?

Likewise, the federal government—specifically, the U.S. Department of Education, which issues the vast majority of student loans—has a vested interest in ensuring that federal financial aid supporting students in higher education is spent on programs that represent a good investment of taxpayer dollars. The country needs an educated workforce, and so federal investments in career training programs should be made at institutions that have a proven record of graduates who can actively participate in the national economy while paying off their student loans.

The question is, how can both students and the federal government be assured that career training programs are a good investment? What guarantee is there that these program’s graduates go on to be gainfully employed, rather than jobless and saddled with debt?

One way of assuring students and the federal government alike that a career training program delivers on its promises is through a set of regulations known as the Gainful Employment (GE) rule. Under President Obama, in 2011, the U.S. Department of Education enacted regulations for determining whether career training programs met the Higher Education Act’s standard for eligibility to distribute Pell Grant and student loans. Dubbed the Gainful Employment rule based on the statutory language, the regulations restricted federal financial aid eligibility for nondegree and for-profit programs that leave students with debt their earnings cannot support, signaling to consumers that the program may not be worth their financial investment. However, under President Trump, the Department of Education rescinded the GE rule in favor of posting earnings and debt data online,1 which, the evidence shows,2 is not enough to improve student outcomes.3

In the coming days, the Department of Education is expected to release a new version of the GE rule, putting the regulations on track to take effect in July 2024. Altogether, this rule marks the strongest step taken to date to protect students and taxpayers from investing in low-quality programs that result in rampant debt and low earnings.4 Some groups, however, including the for-profit college lobby, have raised concerns about the unintended consequences of the new regulations, arguing that they may constrict access,5 especially for under-served groups,6 or hold programs to unfair earnings standards.

The analysis done for this report offers a closer look at the data, bringing evidence to bear in a discourse that is too often driven by speculation. When considering how to decide what’s best, the public should not, and cannot, lose the forest for the trees: the GE rule’s benefits to students and taxpayers will far outweigh the costs.

The GE rule will direct students to programs that produce higher earnings and lower debt burdens.

The Gainful Employment rule applies to about 32,000 career training programs that collectively enroll almost 3 million federal financial aid recipients every year.7 The rule will apply to certificate programs across all sectors, and nearly all degree programs at for-profit colleges.8

The final rule is expected to contain two important metrics that hold career training programs accountable for leaving students with affordable debt and sufficient earnings after graduation. Programs whose graduates as a whole have an annual debt-to-earnings rate (D/E) that is less than or equal to 8 percent, or a discretionary D/E earnings rate less than or equal to 20 percent will be classified as passing the D/E test.9 Programs whose graduates have median annual earnings greater than the median earnings among high school graduates aged 25 to 34 who are in the labor force in the state in which the program is located will be classified as passing the earnings premium (EP) test.10

The D/E and EP tests work together to protect students. For example, programs may pass D/E and leave students with affordable debt, but these same programs may fail EP and still leave graduates worse off than if they’d never gone to college, with insufficient earnings. The Department of Education finds that borrowers in programs such as these have high rates of default. Applying both tests to career training programs helps protect students from risky borrowing or from using up their limited Pell Grant dollars in a low-value program.

Students often enroll in career training programs seeking to advance their careers, increase their earnings, and provide better lives for their families, and many career training programs advertise themselves as providing a pathway out of poverty.11 When students enroll in these programs, they are investing in their education and themselves. They should be able to benefit from a return on their investment that, at a minimum, leaves them better off than they would have been if they had never enrolled. The Gainful Employment rule holds these programs accountable for making good on these promises.

When students enroll in these programs, they are investing in their education and themselves. They should be able to benefit from a return on their investment that, at a minimum, leaves them better off than they would have been if they had never enrolled.

To measure the benefits of the GE rule on lowering debt and boosting earnings, analysis for this report included a simulation in which the completers of each program that will fail the GE rule instead were completers of the nearest non-failing program, at the same credential level and in the same discipline.12 Assuming the median debt and earnings of these programs would not change,13 aggregating statewide shows improvements across every state if students shifted to the nearest non-GE-failing program.14

A common argument made by the for-profit lobby15 is that career training programs fail on debt and earnings metrics because of the students they serve. However, as research has shown, the quality of educational programs matters greatly for the outcomes that students see and the value they receive from their education. For example, for-profit enrollment itself has been shown to cause negative repayment outcomes.16 Additional work has found that, even net of student characteristics, program type and quality matter. As demonstrated in research conducted by the Department of Education, “even among programs with students from the lowest income families, there are programs whose students go on to have earnings success after program completion.”17

Looking only at those students who would transfer from a program that fails GE to the nearest alternative program, their earnings would increase by 45 percent on average, from $21,600 to $31,500.

Figure 1 shows how much the typical annual earnings of federal financial aid recipients who complete their programs18 will increase in every state (see Figure 1).19 The increases in annual earnings are sizable, more than $5,000 in New Mexico and Louisiana and ranging as high as $10,000 in Idaho. When aggregated for all federal financial aid recipients nationwide, the typical increase is about $3,400 in annual earnings.

Figure 1

Source: Author’s analysis of data from the U.S. Department of Education on Title IV programs. Note: Programs located outside the United States are not included. See the appendix for details.

Looking only at those students who would transfer from a program that fails GE to the nearest alternative program, their earnings would increase by 45 percent on average, from $21,600 to $31,500.20

The GE rule will also help create a higher education landscape in which students have access to programs that produce more manageable debt burdens. Figure 2 shows that, when the model has students in programs that fail the GE rule enrolling in the nearest non-failing program, the annual debt-to-earnings rate falls, meaning that debt payments will take up a smaller portion of borrowers’ monthly incomes.21 In the United States overall, the typical graduate’s annual debt payments will fall from 4.3 percent of their annual income to 3.7 percent.22

Figure 2

Looking only at those students who would transfer from a program that fails GE to the nearest alternative program with sufficient data, the percentage of income needed for debt payments would fall from 7.8 percent to 3.7 percent.23 These drops in debt burden will translate into a real difference in borrowers’ finances: for a borrower earning $25,000 per year, a four percentage point drop in annual debt-to-earnings rate means $1,000 less in debt payments they will need to make every year on a standard repayment plan.

The above findings demonstrate significant wins for students and borrowers: meaningful increases in their earnings, and decreases in the burden that debt places on their finances.24

Students in programs that will fail the GE rule have better options within reach.

Critics of the Gainful Employment rule have argued that the proposed rule will reduce access, cutting off federal financial aid for students who do not have another nearby option.25 But this is not true, and the Department of Education has already provided some analysis to counter this concern, noting that “more than 90 percent of students enrolled in failing programs have at least one non-failing option within the same geographic area, credential level, and broad field.”26

It is possible to drill down into this assertion by the Department of Education by looking at career training programs in a specific geographic area according to what is known as their Classification of Instructional Programs (CIP) codes. CIP codes are part of a classification system that groups instructional programs by their subject matter and assigns them numeric codes; the more specific the grouping, the more digits in the code number. Looking at instructional programs in a geographic area by their CIP codes would indicate whether a student has options nearby for their desired field of study. For example, students may have alternative options nearby in the same field of study (that is, two-digit CIP code, such as engineering and health) or even in the same discipline (that is, four-digit CIP code, such as electrical engineering and medical assisting). According to analysis by the Department of Education:

- Half of students in programs that will fail the GE rule have at least one non-failing program of the same credential level at the same institution and same two-digit CIP code, and nearly a quarter have more than one option.

- Two-thirds of students at programs that will fail the GE rule have a transfer option that passes the GE rule within the same geographic area (that is, three-digit ZIP code area), credential level, and four-digit CIP code.

- More than nine in ten students at programs that will fail the GE rule can turn to a passing program in the same three-digit ZIP code area, credential level, and two-digit CIP code.27

In practice, how far will students have to travel to attend these alternative programs that do not fail the GE rule? Using the geographic coordinates of programs’ ZIP codes, analysis for this report calculated the nearest alternative program for every program that will fail the GE measures. (For this purpose, a program with insufficient data for calculating GE metrics is counted as passing the rule.)28

Table 1 shows that, to reach a non-failing program at the same credential level and in the same discipline (four-digit CIP), a student would need to travel 5.1 miles, on average. If a student wanted to consider an alternative that is simply in the same field of study (two-digit CIP), this average drops to just 2.7 miles.

To reach a non-failing program at the same credential level and in the same discipline (four-digit CIP), a student would need to travel 5.1 miles, on average.

Because students in programs subject to GE tend to be older, analysis for this report assumes that students are unlikely to change homes to attend an alternative program.29 When calculating average distances, students who have no alternative option within thirty miles were excluded;30 instead, their share of the total is recorded in a column on the right.31

As noted in the Department of Education’s analysis, a student who is in a failing program as it loses Title IV eligibility may not consider alternatives at a different credential level. However, a prospective student who has not yet enrolled might consider both associate’s and bachelor’s-degree programs, or both master’s and postgraduate certificate programs. If programs that are in the same credential category (undergraduate versus graduate) are included in the analysis, then the average is just 3.3 miles, even if it is assumed that the student will seek out the same discipline (four-digit CIP code).

Table 1

| AVERAGE DISTANCE IN MILES TO NEAREST ALTERNATIVE PROGRAM FOR STUDENTS AT PROGRAMS FAILING THE GE RULE | |||

| CIP Code of alternative programs | Credential level of alternative programs | Average distance to closest alternative | Share with no option within 30 miles |

| Same discipline (CIP4) as failing program | Same credential level as failing program | 5.1 miles | 22.4% |

| Same discipline (CIP4) as failing program | Same credential category (undergraduate/graduate) as failing program | 3.3 miles | 12.2% |

| Same field of study (CIP2) as failing program | Same credential level as failing program | 2.7 miles | 7.5% |

|

Source: Author’s analysis of data from the U.S. Department of Education using geospatial analysis software. Note: Programs located outside the United States are not included. See the appendix for details. |

|||

Ensuring that students can access the public or private transportation needed to attend classes is a public policy priority for cities, states, and the federal government—a challenge that governments at all levels need to address whether or not the GE rule is in effect. Analysis for this report suggests that enacting the GE rule will not drastically exacerbate that existing challenge.

The GE rule’s earnings premium test will not have a larger impact on programs in low-income areas.

In the draft of the rule, the Department of Education has proposed holding programs subject to the GE rule to a standard known as the earnings premium (EP) test. To maintain eligibility for federal financial aid under this proposal, a program must prepare at least a majority of its graduates so that they earn more than the typical working high school graduate in the same state and who does not have a postsecondary credential.32

As the earnings premium test has been discussed, some have voiced concerns about comparing the earnings of programs’ graduates in low-income areas against statewide median earnings.33 Specifically, those programs in low-income, high-poverty areas may struggle to meet this metric because of the lower earning potential in these areas.

At the same time, the alternative—holding programs in low-income areas to a different, easier-to-meet benchmark—risks incentivizing bad actors to target poor communities as a form of predatory inclusion.34 And it may be bad practice to further lower the earnings premium threshold in these areas, given that the rule’s earnings premium wage level is already lower than a living wage, as New America has found.35

How much concern should there be about the GE rule’s impact in low-income areas? As an empirical matter, how common is it for programs subject to the GE rule to be based in areas that have low incomes, relative to their state’s average income? To examine this question, the analysis for this report linked Census Bureau data on the income of households with earnings from wages or salary, aggregated by ZIP Code Tabulation Area (ZCTA), with Department of Education data on programs that are subject to the GE rule.36 The analysis pooled income data at the four-digit ZCTA level (ZCTA4), a middle-ground between the coarse-grained ZCTA3 (for example, 112 for Brooklyn) and the fine-grained ZCTA5 (for example, 11205 for northwest Bedford–Stuyvesant).37

The analysis found that just 19.9 percent of programs subject to the GE rule are located in a ZCTA4 that falls in the bottom quarter by income, among all ZCTA4s in their state. (See Table 2.) This percentage is disproportionately small: if low-income areas had just as many programs subject to the GE rule as did areas that are not low-income, then the percentage would be 25 percent.38

Table 2

| PROGRAMS SUBJECT TO THE GE RULE BY EARNINGS PREMIUM EVALUATION AND INCOME QUARTILE OF SURROUNDING AREA RELATIVE TO STATE | |||

| Earnings premium (EP) evaluation | Located in ZCTA4 that is bottom 25% by income | Located in ZCTA4 that is upper 75% by income | Percent located in bottom 25% by income |

| Passes EP test | 360 | 1,524 | 19.1% |

| Fails EP test | 202 | 1,205 | 14.4% |

| No data for EP test | 4,838 | 18,955 | 20.3% |

| All programs | 5,400 | 21,684 | 19.9% |

| Note: This table applies only to non-online programs located in the United States that are subject to the GE rule. | |||

Moreover, programs subject to the GE rule in the bottom quarter of areas by income account for only 14.4 percent of all EP failures. In fact, programs in low-income areas show no worse frequency of passing the EP test (64 percent) than those in upper-income areas (56 percent).39

Programs subject to the GE rule located in lower-income areas also tend to be smaller. The average program in the bottom quartile of areas by income graduated 31 students per year in 2015–16 and 2016–17, compared to 39 for programs subject to the GE rule in areas in the top three quartiles by income.40

The analysis found that programs subject to the GE rule in low-income communities are slightly scarcer, slightly smaller, and no less likely to pass GE than those in upper-income communities. These findings may ease some concerns that applying statewide income standards would sharply diminish the postsecondary options available to low-income communities. Of course, some programs do operate in high-poverty communities—and it is especially important that those offerings be high-quality. Increasing access to quality higher education for low-income communities should be a priority of Congress, the White House, and state governments, even beyond instituting the GE regulations.

Visualizing a Future with Higher Earnings and Lower Debt

Students enroll in career training programs with plans to advance their careers and provide for themselves and their families. The Gainful Employment rule will hold career training programs accountable to the students they serve—and to the federal government that finances the system through student aid—by ensuring that when students leave school, they receive sufficient earnings, are able to pay their loan debts, and they realize an overall return on their investment in the promise of higher education.

Although critics of the GE rule argue that it will diminish access to career training programs, analyses here show that it will instead steer students toward higher-quality programs that pass the debt-to-earnings and earnings premium tests of the Gainful Employment rule, increase earnings, and reduce debt.

With the final rule soon to be released, the fate of GE will soon turn to Congress, which is permitted under the Congressional Review Act to reject a federal agency’s rule. The Gainful Employment rule is a win for students and for taxpayers, one that Congress should not obstruct.

Although critics of the GE rule argue that it will diminish access to career training programs, analyses here show that it will instead steer students toward higher-quality programs that pass the debt-to-earnings and earnings premium tests of the Gainful Employment rule, increase earnings, and reduce debt.

The value of the GE rule for students’ futures cannot be understated—particularly for students who typically experience barriers when trying to access higher education. Career training programs are more likely to enroll students who are underrepresented in higher education, students who are looking to higher education as a way to achieve social mobility. The data show that the GE rule will help to achieve this promise of economic mobility by ensuring career training programs lead to sufficient earnings and manageable debt for their graduates.

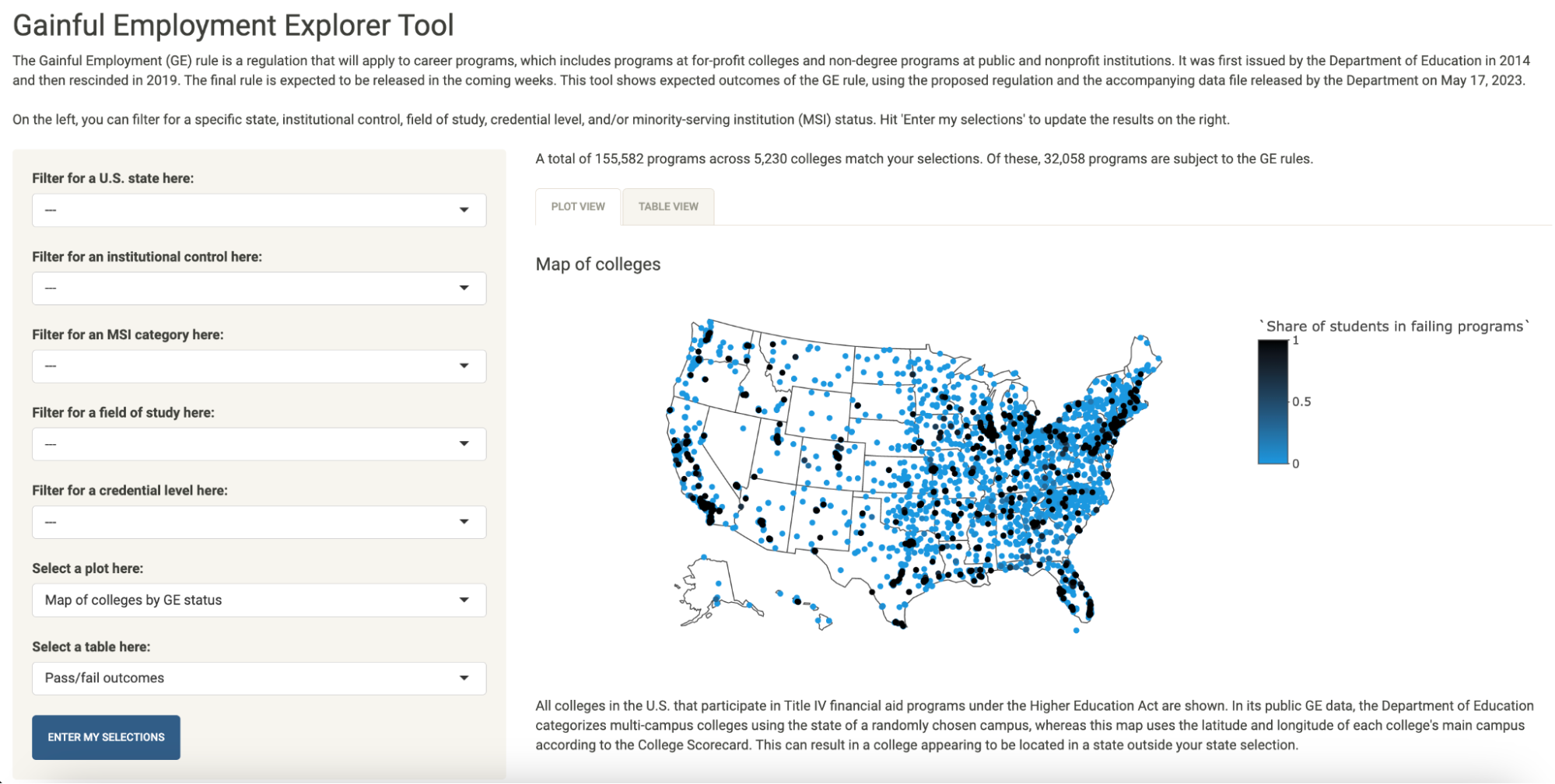

In order to visualize the expected impact of the GE rule, The Century Foundation has created a GE Explorer Tool, where users can create maps, charts, and tables using data filtered by state, field of study, credential level, and more.

Figure 3: The Gainful Employment Explorer Tool

Notes about the data analysis in this commentary can be found in this Appendix. The code used for the analysis in this report can be found at this GitHub repository.

Thanks to Clare McCann and Dr. Kyle Southern for their feedback on an early draft of this report.

Notes

- Robert Shireman, “Profits Put Students at Risk. A Gainful Employment Rule Will Protect Them.” The Century Foundation, May 15, 2023, https://tcf.org/content/report/profits-put-students-at-risk-a-gainful-employment-rule-will-protect-them/.

- Michael Hurwitz, Jonathan Smith, “Student Responsiveness to Earning Data in the College Scorecard,” Economic Inquiry, December 6, 2017, https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/ecin.12530.

- Dominique J. Baker, Stephanie Riegg Cellini, Judith Scott-Clayton, and Lesley J. Turner, “Why Information alone is not enough to improve higher education outcomes,” Brookings, December 14, 2021, https://www.brookings.edu/articles/why-information-alone-is-not-enough-to-improve-higher-education-outcomes.

- Amber Villalobos, Robert Shireman, Carolyn Fast, Denise A. Smith, Tiara Moultrie, and Peter Granville, “The New Gainful Employment Rule Is the Biggest Step Ever Taken to Ensure Accountability in Higher Education,” The Century Foundation, July 13, 2023, https://tcf.org/content/commentary/the-new-gainful-employment-rule-is-the-biggest-step-ever-taken-to-ensure-accountability-in-higher-education/.

- Career Education Colleges and Universities, “ED-2023-OPE-0089-2977,” Regulations.gov, June 20, 2023, https://www.regulations.gov/comment/ED-2023-OPE-0089-2977; Michael Bianchi, “ED-2023-OPE-0089-2011,” Regulations.gov, June 20, 2023, https://www.regulations.gov/comment/ED-2023-OPE-0089-2011.

- Donald Pobiak, “ED-2023-OPE-0089 Comments,” Regulations.gov, June 19, 2023, https://www.regulations.gov/comment/ED-2023-OPE-0089-3111; “ED-2023-OPE-0089-1912,” Regulations.gov, June 19, 2023, https://www.regulations.gov/comment/ED-2023-OPE-0089-1912.

- See the notice of proposed rulemaking, “Financial Value Transparency and Gainful Employment, Financial Responsibility, Administrative Capability, Certification Procedures, Ability to Benefit,” U.S. Department of Education, May 19, 2023, https://www.regulations.gov/document/ED-2023-OPE-0089-0001.

- According to the U.S. Department of Education, in the 2015–16 and 2016–17 award years, programs subject to the GE rule enrolled 2,931,000 students per year.

- 88 Fed. Reg. 32326 (May 19, 2023). Annual debt to earnings rates are calculated using annual debt payments to total earnings in a year. Discretionary earnings rates are calculated using annual debt payments to earnings above 150 percent of the Federal Poverty Level.

- 88 Fed. Reg. 32300, 32411 (May 19, 2023).

- Rachel Fishman, “Proposed Gainful Employment Regulations Will Protect Students and Taxpayers,” New America, May 18, 2023, https://www.newamerica.org/education-policy/edcentral/proposed-gainful-employment-regulations-will-protect-students-and-taxpayers/.

- We use the term “discipline” to refer to a program’s four-digit Classification of Instructional Programs (CIP) code. We use the phrase “non-failing,” rather than just “passing,” because we assume some students will transfer to alternative programs that are not subject to the GE rule or to programs subject to the GE rule that have cohort sizes that are too small to be evaluated in U.S. Department of Education data. Figures 1 and 2 reflect programs that had sufficient cohort sizes for evaluation, including those subject to GE and not subject to GE.

- Stephanie R. Cellini, Rajeev Darolia, and Lesley J. Turner, “Where Do Students Go When For-Profit Colleges Lose Federal Aid?” National Bureau of Economic Research, December 2016, https://www.nber.org/papers/w22967.

- We use median earnings and median annual debt payments as proxies for mean earnings and mean annual debt payments, which are not provided by the U.S. Department of Education. See the appendix to this report for details.

- Career Education Colleges and Universities, “ED-2023-OPE-0089-2977” Regulations.gov, June 20, 2023, https://www.regulations.gov/comment/ED-2023-OPE-0089-2977; Michael Bianchi, “ED-2023-OPE-0089-2011,” Regulations.gov, June 20, 2023, https://www.regulations.gov/comment/ED-2023-OPE-0089-2011.

- Luis Armona, Rajashri Chakrabarti, and Michael F. Lovenheim, “Student Debt and Default: The Role of For-Profit Colleges,” Federal Reserve Bank of New York, April 2017, https://www.newyorkfed.org/research/staff_reports/sr811.html.

- 88 Fed. Reg. 32431 (May 19, 2023).

- In other words, Pell Grant recipients and student loan borrowers.

- The District of Columbia is an outlier, so we remove it from Figure 1. Its pre-GE rule earnings value is $71,997, and its post-GE rule earnings value is $76,534.

- For this exercise, in which we look strictly at the students who would transfer out of programs that fail the GE rule, the simulation has every student in a program that fails GE attend the nearest alternative program that has data on debt and earnings. This modification boosts the set of programs on which we base our aggregate statistics. See appendix for details.

- In Hawaii, the annual D/E rate increases, which may be because the state features two programs that fail the EP test and none that fail the D/E test. Simulating transfer will have students from those two programs attend higher-earnings programs, which may also be somewhat higher-debt programs.

- The U.S. Department of Education data on annual debt payment measure reflects borrowers and non-borrowers in the Title IV program.

- For this exercise, in which we look strictly at the students who would transfer out of programs that fail the GE rule, the simulation has every student in a program that fails GE attend the nearest alternative program that has data on debt and earnings. This modification boosts the set of programs on which we base our aggregate statistics. See appendix for details.

- Calculations were based on the wording of the proposed rule released in May 2023 and do not reflect any changes made before the rule becomes final.

- Career Education Colleges and Universities, “ED-2023-OPE-0089-2977,” Regulations.gov, June 20, 2023, https://www.regulations.gov/comment/ED-2023-OPE-0089-2977.

- 88 Fed. Reg. 32309 (May 19, 2023).

- 88 Fed. Reg. 32433 (May 19, 2023).

- A program with fewer than thirty graduates has data suppressed from the U.S. Department of Education’s public analysis of programs subject to the GE rule and no pass or fail outcome is recorded. When the rule takes effect, the Department of Education will expand the cohort for evaluating these small programs, from two years of graduates to four years; this is not accounted for in the department’s public data. A year when a program has insufficient cohort size for evaluation neither counts as a “passing year” or a “failing year” for the purpose of determining whether a program failed GE two out of three consecutive years. See the notice of proposed rulemaking for more details, “Financial Value Transparency and Gainful Employment, Financial Responsibility, Administrative Capability, Certification Procedures, Ability to Benefit,” U.S. Department of Education, May 19, 2023, https://www.regulations.gov/document/ED-2023-OPE-0089-0001.

- According to Tables 1.6 and 1.7 in the Notice of Proposed Rulemaking, 66.1 percent of students in a program that is subject to the GE rule are aged 24 or older, compared to 37.3 percent of students in a program that is not subject to the GE rule.

- We make an exception for online programs, as an alternative for online programs that fail GE. See the appendix for our full methods.

- Of course, distances below this threshold–29 miles, for instance–may still be prohibitively far for some students, especially those without access to a car. For more details, see the appendix.

- A special exception is made for online programs with at least half of students enrolling from out of state. These programs are held to an earnings threshold calculated based on a nationwide sample of survey respondents, rather than a state-level sample. For more details, see the notice of proposed rulemaking, “Financial Value Transparency and Gainful Employment, Financial Responsibility, Administrative Capability, Certification Procedures, Ability to Benefit,” U.S. Department of Education, May 19, 2023, https://www.regulations.gov/document/ED-2023-OPE-0089-0001.

- This includes a broad range of stakeholders, and the U.S. Department of Education itself raised the concern in its notice of proposed rulemaking.

- For example, this argument was raised in a comment submitted by a group of State Attorneys General to the Department of Education; see “Comment on FR Doc # 2023-09647,” June 21, 2023, https://www.regulations.gov/comment/ED-2023-OPE-0089-2975. For-profit colleges’ practice of targeting economically vulnerable communities has been well-documented by the Student Borrower Protection Center, among others; see “Mapping Exploitation: Examining For-Profit Colleges as Financial Predators in Communities of Color,” Student Borrower Protection Center, July 2021, https://protectborrowers.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/SBPC-Mapping-Exploitation-Report.pdf

- Tia Caldwell, “An Earnings Threshold Would Sanction Only Low-Value College Programs,” New America, April 25, 2023, https://www.newamerica.org/education-policy/edcentral/gainful-employment-earnings-threshold-living-wage/.

- The ZIP codes of programs subject to the GE rule are provided by the Department of Education. Most ZIP codes correspond to a ZCTA, although not always. Absent more data, this is a strong approach albeit imperfect.

- In the United States there are roughly 900 three-digit ZCTAs, roughly 6,000 four-digit ZCTAs, and more than 31,000 five-digit ZCTAs.

- We examine the robustness of this result using several alternative measures. See the appendix to this report for details.

- While programs in all areas are more likely to pass the GE rule than they are to fail, passing appears to be slightly more likely in geographic areas in the bottom quarter of income than it is in areas in the top three quarters of income. For example, 360 of the 562 programs with sufficient data in low income areas—and 1,524 of the 2,729 programs with sufficient data in higher income areas—pass GE, putting pass rates at 64 percent and 56 percent within these regions, respectively.

- In calculating these averages, we did not include programs with missing cohort size data.